Abstract

We describe the fabrication and use of an in vitro wounding device that denudes cultured epithelium in patterns designed to leave behind strips or islands of cells sufficiently narrow or small to ensure that all remaining cells become rapidly activated and then migrate, dedifferentiate and proliferate in near synchrony. The design ensures that signals specific to regenerating cells do not become diluted by quiescent differentiated cells that are not affected by wound induced activation. The device consists of a flat circular disk of rubber engraved to produce alternating ridges and grooves in patterns of concentric circles or parallel lines. The disk is mounted at the end of a pneumatically controlled piston assembly. Application of controlled pressure and circular or linear movement of the disk on cultures produced highly reproducible wounding patterns. The near synchronous regenerative activity of cell bands or islands permitted the collection of samples large enough for biochemical studies to sensitively detect alterations involving mRNA for several early response genes and protein phosphorylation in major signaling pathways. The method is versatile, easy to use and reproducible, and should facilitate biochemical, proteomic and genomic studies of wound induced regeneration of cultured epithelium.

Keywords: wound healing, wounding device, regeneration, epithelium

INTRODUCTION

Loss of epithelium by wounding or cell death in tissues such as skin, intestine, airways and kidney tubules is followed by a series of healing responses: migration and proliferation of epithelial and stromal cells, inflammation, tissue remodeling and fibrosis. These complex events have been studied extensively using models of wound healing in experimental animals (1, 2). Research on epithelial regeneration requires in vivo models of wounding and injury to provide a framework of relevance to repair in the living organism. Regardless, such in vivo studies fail to yield information on the unique roles played by specific cell types in the repair process. This type of information becomes necessary for the design of rational treatment strategies directed at important targets – for example, the signaling pathways that control the migration, proliferation and differentiation of epithelial cells. The identification and characterization of epithelial specific responses during in vivo repair is made difficult by confusion caused by the simultaneous activation of multiple signaling pathways in several cell types. This has necessitated the use of in vitro “wound” models to remove cells from designated areas of cultured confluent and contact inhibited epithelial monolayers. Cells that border the “wounds” are then studied to characterize the epithelial specific healing responses.

Conventionally used in vitro wound-healing models employ plastic pipette tips (3), needle points (4), scalpels (5), scrapers (6), floating pin arrays (7), or plastic hair combs (8–10) to dislodge narrow strips of cell monolayers from the culture substratum. Such techniques yield visible wounds bounded by large areas of intact epithelium. At wound edges, cells become activated, migrate into denuded areas and proliferate. Epithelial responses at the edges of wounds produced by these methods can be evaluated by microscopy, immunocytochemistry and in situ hybridization. Laser capture microdissection can also be used to remove activated cells from wound edges and unperturbed cells from distant areas to extract RNA for analysis. However, due to the small size of samples obtained by laser capture microdissection, even RT-PCR based techniques to study gene expression are demanding, tedious and require specially prepared expensive proprietary reagents. Moreover, the versatility of analysis that is possible with large sample sizes is compromised. Several other technical issues make these wound models restrictive for analysis by biochemical and molecular biological techniques. Most conventional wounding methods are unsuitable for high throughput sample handling and the wound areas are too inconsistent for standardized experimental analysis. Compared to non-activated cells distant from wounds, the mass of activated, migrating and proliferating cells adjacent to wound edges is very small, resulting in high noise to signal ratios. Consequently, there has been a need for simple, quick, reproducible and uniform wounding methods that yield experimental samples sufficient for biochemical studies on regenerating cells. Such methods need to fulfill the following criteria. First, the wounding pattern should be such that the remaining islands of viable cells are of dimensions sufficiently small to ensure nearly synchronous activation of the entire population. Although activation occurs immediately at wound edges and involves a narrow band only a few cells deep at first, this requirement would assure sequential activation of all remaining cells rapidly. Second, it would be important that damaged cells not remain on the culture substratum to prevent the dilution and contamination of signals specific to viable activated cells by degenerative changes that occur in damaged and dead cells.

Other investigators have attempted to develop wounding devices suitable for biochemical studies. To minimize noise to signal ratio, a scraping device was designed to produce a spiral curvilinear wound that is continuous from the centers of culture dishes to their periphery (11). However, even with this improvement, only 40% of the remaining cells were involved in the wound-healing process. Shark’s tooth gel sequencing combs were used to wound cultured cell monolayers along multiple axes and study the biochemical aspects of epithelial regeneration (9). In view of the relatively large widths of cell islands that are expected to be left behind with this technique, we surmised that there would be room for improving the noise to signal ratios. Wounding with electrical current was also tried (12). Although novel in concept with the potential to yield reproducible patterns of dead and viable cells, use of this technique leaves behind electrically scorched cell debris on the culture substratum. The presence of coagulated cells in “wound” areas could hamper uniform migration of remaining cells as well as complicate the biochemical analysis of remaining activated cells. These problems have been largely responsible for the infrequent use of wound healing models as paradigms for the biochemical and molecular biological analysis of regenerating epithelium. This type of information is critically required to be placed in the context of other data from in vivo models of epithelial regeneration so that we may arrive at a better understanding of epithelium-specific processes during repair and regeneration.

In this study, we describe a new wound healing method using a unique stamping device, which would fulfill most of the above stated requirements for in vitro wound healing research. We provide details regarding the design, construction and use of the device and signaling data with documentation of regeneration associated alterations of gene expression to validate the merits of the new method.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture

Boston University mouse proximal tubule cells (BUMPT-Clone 306; from Drs. W. Lieberthal and J. Schwartz) were grown at 37° in DMEM (Gibco) with 10% fetal bovine serum or in serum free DMEM supplemented with insulin (10μg/ml), epidermal growth factor (10 ng/ml), transferrin (5μg/ml), Na selenite (6.7μg/ml) and dexamethasone (4 μg/ml).

Design and use of new wounding device

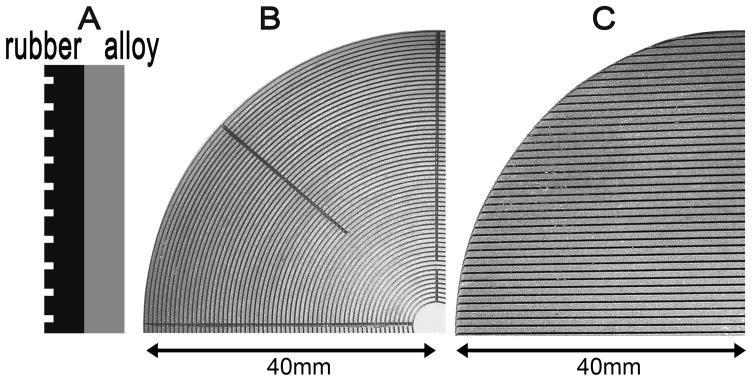

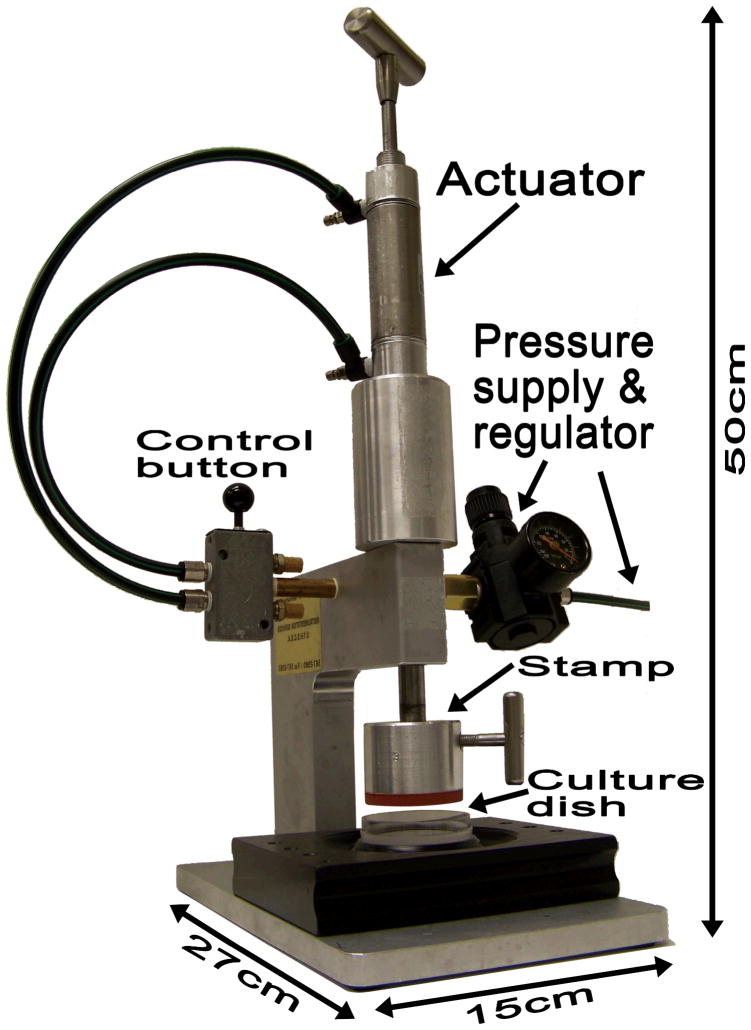

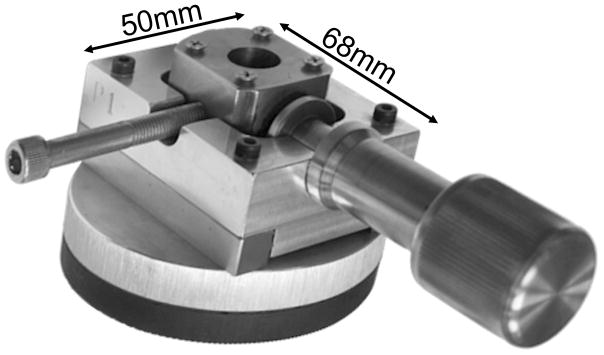

To obtain reproducible wounding of epithelial monolayers in culture dishes, we designed flat circular disks (“stamps”) of Neoprene spring rubber (McMaster-Carr, 8629K181) that were machine engraved with alternating ridges and grooves cut in concentric circles or in a parallel, linear pattern (Fig. 1a–c). We have constructed stamps designed to produce variably sized wounds (200–1000 μm) leaving behind cell bands of widths between 50–200 μm. Stamps were designed to fit 35 mm, 60 mm or 100 mm culture dishes. Our hypothesis was that application of the stamps on cultured cells under conditions of controlled pressure followed by rotation or horizontal translatory movement of stamps would result in reproducibly uniform shearing and removal of cells in desired patterns. To operate the device, the stamp was mounted on an aluminum alloy block at the bottom end of a metal piston which could be moved vertically up and down through a snug fitting vertical tunnel in a heavy aluminum alloy metal stand (Fig. 2). The speed of piston movement and the pressure at which the stamp was applied to the cell monolayer were controlled by means of a pneumatic actuator (Parker Hannifin Corp, WD408801G) with attached pressure regulator providing a controllable pressure range up to 250 psi. The actuator was pneumatically connected to either the house compressed air system or to a compressed air tank. Air flow to the actuator could be controlled by miniature flow controls connected to a 4 way air valve (Mead Fluid Dynamics, LTV-130). This permitted the operator to move the piston up or down at reproducibly controlled speeds and apply the stamp on the culture monolayer at a standardized pressure as well as withdraw the stamp at a controlled speed to avoid creating undue turbulence over the remaining cells. Stamps with concentric patterns were further engraved radially (Fig. 1b) to create channels that would ensure smooth flow of culture medium through them and avoid the creation of vacuum between the remaining cells and the stamp as it was withdrawn. A heavy plastic machine ground culture dish holder was tightly mounted to fit on metal pins fixed to the bottom plate of the machine assembly such that the dish and the piston axis were concentric (Fig. 2). Stamps with parallel patterns of ridges and grooves were mounted on the bottom of a precision sliding platform that permitted stamp movement along one axis using a screw controlled mechanism (Fig. 3). Stamps with parallel patterns were slightly elliptical in configuration to allow 0.3–0.7 cm sliding movements within the confines of circular culture dishes.

Figure 1.

(a) Diagrammatic representation of a wounding stamp, shown as a vertical section. The stamp consists of a circular and flat rubber disk machine engraved to produce concentric or parallel grooves alternating with ridges (left), mounted on a cylinder of aluminum alloy (right). (b) En face photograph of a stamp with concentric grooves. The stamp is further engraved radially to produce channels that permit free flow of fluid as the stamp is lifted away from the cells after wounding. (c) En face photograph of a stamp engraved with parallel grooves. For clarity, only one quadrant each of the circular stamps is shown in (b) and (c).

Figure 2.

Photograph of the entire wounding device assembly. The culture dish is mounted on a heavy plastic dish holder. A stamp designed to produce a concentric wounding pattern is attached to the bottom of a piston mounted on a heavy metal stand. The piston can be moved up or down at different speeds by a pneumatic actuator controlled by air pressure and a simple system of valves. The pneumatic actuator lowers the stamp on to the culture surface and makes contact at a predetermined pressure. To produce the wound, a metal holder screwed to the lateral side of the metal part of the stamp is used to manually rotate the stamp on the culture surface through an arc of 30–60 degrees.

Figure 3.

Photograph of a stamp engraved with parallel grooves, mounted on the bottom of a precision sliding platform with a screw controlled mechanism. Rotation of the screw moves the stamp along a horizontal axis producing a parallel wounding pattern.

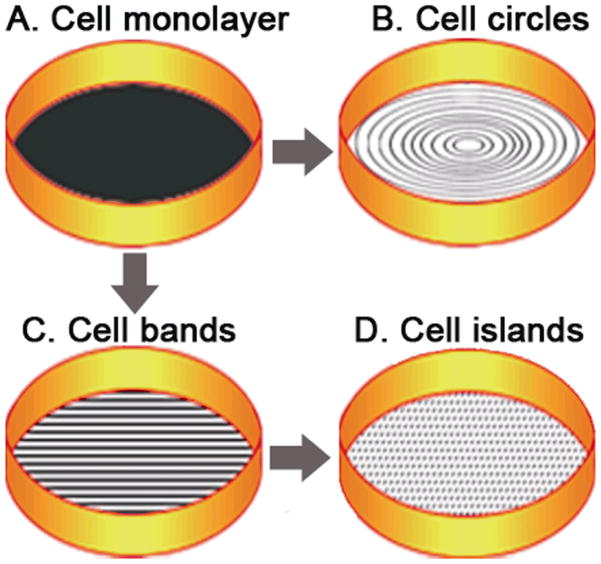

To operate the wounding device, the stamp was quickly sterilized with 75% alcohol, rinsed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and then primed with culture medium in a dish. For a concentric wounding pattern, the stamp was locked snugly at the bottom of the piston using a set screw on the side of the stamp holder. The culture dish was mounted on a silicone rubber pad placed on the dish holder after removal of most of the culture medium, keeping just enough medium to keep the cells hydrated through the operation. The stamp was then lowered onto the culture dish by the actuator connected to the house air supply or a tank of compressed air. A control button was used to operate pneumatic valves (Fig. 2) and regulate the pressure within the actuator, drive the piston downwards and contact the culture surface at a standardized pressure. By trial and error, we optimized the pressure to be ~40–50 psi for 35mm/60mm Petri dishes, and ~140 psi for 100mm Petri dishes. Using a handle fixed to the side of the stamp (Fig. 2), the stamp was then manually rotated through an arc of 30–60 degrees to shear the cells away from the culture substratum, thus wounding the monolayer in a concentric pattern (Fig. 4a, b). The arc of rotation was empirically determined for a given experiment by examination of the wounding pattern, the widths of wounds and surviving cell bands. Due to imperceptible variations of width in ridges on the stamp, increasing the arcs of rotation tended to make the wounds wider and therefore, the cell bands became narrower. For this reason we found it advisable not to increase the arc of rotation beyond 60 degrees. Surviving cell bands with a parallel pattern (Fig. 4a, c) were obtained by horizontal translation (0.3–0.7 cm) of the corresponding stamp mounted on a precision sliding platform using a screw controlled mechanism (Fig. 3). To get surviving islands with a square or rectangular configuration, the stamp was lifted after the first wounding step, rotated 90 degrees, applied on to the cells again, and wounding was done once more (Fig. 4a, c, d). For repeated use, the stamp (still mounted on the piston) was washed and primed with fresh culture medium. After wounding, culture surfaces with growing cells not contacted by the stamp were denuded of cells using an eyebrow brush. This step was found to be important because large numbers of cells were found to be spared from wounding along the peripheral flange areas and lateral walls of the dish. Furthermore, all wounded dishes were checked visually against a black background and microscopically to identify unwounded areas or cell bands that were unacceptably wide. These areas were manually scraped with a brush to remove the cells. If the acceptable areas were less than 60% of the total, the dish was rejected. The remaining wounded cells were rinsed gently with culture medium several times and returned to the incubator. After use, stamps were rinsed clean with strong streams of de-ionized water.

Figure 4.

Diagrammatic representation of wounding patterns resulting from rotation of stamps engraved with concentric or parallel grooves. Rotation of concentric stamp on a cell monolayers (a) results in circular cell bands (b). First sliding movement of stamp with parallel grooves produces parallel cell bands (c). Second sliding movement on the same dish at right angle to the first wound produces square or slightly rectangular cell islands (d).

Quantitative Real-time PCR (qPCR) for RNA

To measure mRNA for c-Fos, c-Jun and JunB by qPCR, we designed oligonucleotide primers using Primer Express® version 3.0 software. The following primers were used: 5′-TGCGGACGGTTTTGTCAA-3′ and 5′-GCGTCACGTGGTTCATCTTG -3′ for JunB; 5′-AATGGGCACATCACCACTACAC-3′ and 5′-TGCTCGTCGGTCACGTTCT -3′ for cJun; 5′-TTCTTGTTTCCGGCATCATCT-3′ and 5′-GCTCCCAGTCTGCTGCATAGA -3′ for cFos. Total RNA was prepared from cells using RNeasy reagents according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen) and reverse transcribed. Real time PCR was done using a SYBR Green PCR mixture (Applied Biosystems) in a 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). RNA abundance was normalized to that for 18S ribosomal RNA and expressed as the relative fold increase over the value before wounding.

Time-lapse Video Microscopy

We performed time lapse video microscopy using an inverted microscope (LTC0450, Philips) in a temperature controlled, 5% CO2 incubator (Model 3956, Forma Scientific, Inc.). Images were captured at 1 frame/6 minutes using a digital camera (AxioCam MR, Carl Zeiss, Inc.) controlled by AxioVision software (version 3.1, Carl Zeiss, Inc.).

BrdU incorporation into DNA

Wounded or unwounded confluent BUMPT cell monolayers were incubated with 10 μM 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU, Sigma) during the last 1 hour prior to fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes. After fixation, the cells were washed 3X with PBS and incubated with 0.1M glycine-PBS for 5 minutes. After permeabilization of cells with 1% SDS in PBS for 5 min. and PBS washes (X3), DNA was denatured at 70°C with 9:1 formamide:0.1M NaPi, pH 7.4 for 40 min. Dishes with cells were then incubated sequentially with BrdU antibody and Cy3 labelled secondary antibody, and mounted in ProLong Gold antifade reagent with DAPI (Molecular Probes).

Western blot analysis of proteins

Cells were washed 2X with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and extracted with Laemmli buffer, reduced and boiled. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE on 10% bis-tris or 8% tris-glycine gels (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Whatman Inc., Piscataway, NJ). Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk or BSA in PBS-0.2% Tween-20 (PBST) and incubated with primary antibodies in blocking buffer or in 5% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA)-PBST overnight at 4°C. After incubation with affinity purified secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA), proteins were visualized by Enhanced Chemiluminescence (ECL) substrates (Pierce, Rockford, IL). The following primary antibodies were used: Akt, phospho-Akt (S473), S6 Ribosomal Protein and Phospho-S6 Ribosomal Protein (S235/236), Phospho-p44/42 MAP Kinase (Thr202/Tyr204), phospho-Smad2 (S463/465), and phospho-Smad1 (S463/465) (Cell signaling, Danvers, MA); p44/42 MAP Kinase and Smad1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA); Smad2 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA); Ksp-Cadherin Clone 4H6/F9 (Zymed, San Francisco, CA); Paxillin (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA); phosphotyrosine Clone 4G10 (Millipore, Billerica, M); BrdU Clone G3G4 (DSHB, Iowa City, IA); Phospho-Paxillin (Y31) and Phospho-Paxillin (Y118) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA); and GAPDH (RDI, Concord, MA).

RESULTS

The new device permits easy, rapid and reproducible wounding

With relatively little practice, the instrument was found to be easy to use. The time required for the entire wounding operation varied between 3–5 minutes. For stamps that yielded ~170 μm wide cell bands with ~800 μm wounds, nearly 100% of attempts yielded uniform wounding over most of the culture area. On the other hand, with stamps designed to yield cell band widths of 100–150 μm with wound widths of 350–1000 μm, most dishes wounded by the new technique showed uniform patterns of wounding, but also tended to exhibit some areas with unacceptably narrow or wide cell bands or complete denudation. However, with practice and consistent use, such areas were small enough to be ignored. As outlined under “Methods”, non-wounded areas were easily removed with a brush by direct or microscopic examination and increased denudation could be ignored unless it was excessive, in which case, the dish was rejected for use. Data presented in this paper were obtained mostly using a stamp that yielded concentric cell bands of ~130 μm width alternating with ~750 μm wide wounds.

Cells in surviving cell bands adopt an activated, migratory and proliferative phenotype

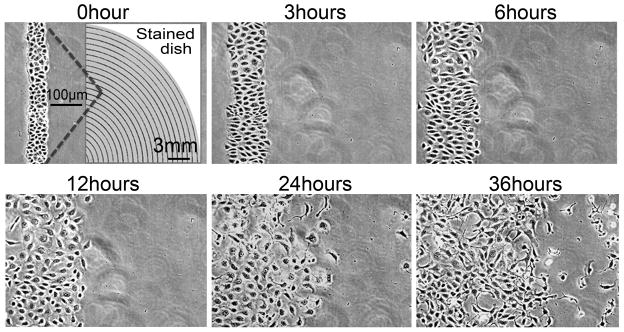

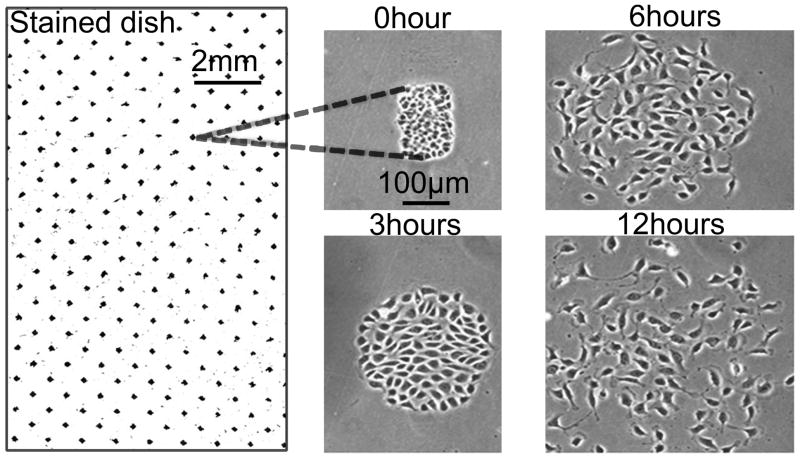

Stamps with a concentric pattern produced correspondingly arranged concentric circular cell bands separated by wounds (Fig. 5); uniform cell bands of 50–70 μm could be obtained with experience, but wounding patterns yielding cell bands ~130 μm wide or greater covering the entire dish were easier to produce, even by inexperienced operators. Sequential wounding in two axes 90 degrees apart using a stamp with parallel pattern was used to produce square or rectangular islands of surviving cells surrounded on all sides by denuded substratum (Fig. 6). Notably, the denuded areas were almost free of scratches permitting unimpeded migration of activated cells into the wounds (Fig. 5, Fig. 6). To ensure that scratches would not occur during the wounding process, we carefully selected the grade of rubber that was used to fabricate the stamp (see Methods). Within a few minutes of wounding, cells at the edges of wounds displayed prominent lamellipodia (Fig. 5), indicating a normal and healthy response by remaining cells. Thereafter, the activation process spread rapidly towards the center of the bands or islands, accompanied by sheet migration into the wounds (Fig. 5, Fig. 6). This was accompanied by separation of cell-cell junctions and eventually by migration of most of the cells as individual units (Fig. 5, Fig. 6). In particular, very rapid cell activation and complete breakdown of intercellular adhesion was observed to occur as early as 6 hours following wounding in the “island” pattern (Fig. 6).

Figure 5.

Still frames from time-lapse video microscopy of cells wounded in a concentric circular pattern. Confluent monolayers of proximal tubule (BUMPT) cells were wounded using a stamp that yielded concentric cell bands of ~130 μm width. The right panel at “0 hour” depicts a low power scanned picture of a wounded dish fixed and stained with alcoholic toluidine blue/basic fuchsin.

Figure 6.

Still frames from time lapse video microscopy of cells wounded to produce islands. Confluent monolayers of BUMPT cells in 100 mm dishes were first wounded in one axis using a stamp with parallel ridges (~800 μm wide) and grooves that were ~200 μm wide. Then, the dish was rotated 90 degrees and wounded once more at right angles to the original axis, producing islands of cells that were approximately 80–150 μm in their maximum width on each side. The top panel shows part of a wounded dish fixed and stained with alcoholic toluidine blue/basic fuchsin. Discrepancies between the expected and actual size of islands shown are attributable to small errors in measuring groove and ridge dimensions, minor irregularities of width along the lengths of ridges, variable compression of the ridges during operation of the wounding device, widening of ridges with age of the stamp after repeated use and other imponderables.

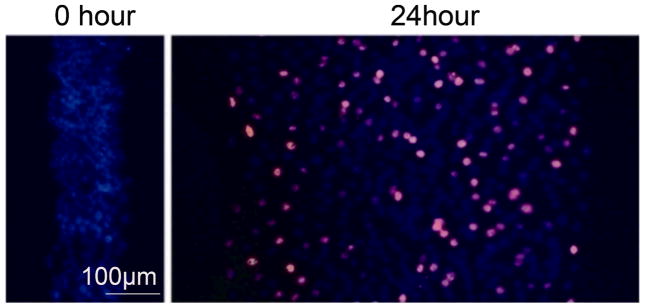

The proliferative capacity of surviving bands of cells was monitored by BrdU incorporation and immunofluorescence. Cells with increased nuclear BrdU incorporation were detected after 6 hours (not shown), became numerous by 12 hours after wounding and were distributed across the entire band width (Fig. 7). These results indicated DNA synthesis, consistent with a vigorous proliferative response. Of interest, there were no differences in the frequency of BrdU positive cells between the center and periphery of the bands (Fig. 7) suggesting that proliferative stimuli had spread rapidly inwards into the bands.

Figure 7.

Fluorescence micrograph of formaldehyde fixed wounded cell bands stained with BrdU antibody and Cy3 labeled secondary antibody to visualize BrdU uptake into nuclei. Confluent monolayers of proximal tubule (BUMPT) cells were wounded using a stamp that yielded concentric cell bands of ~130 μm width. Confluent monolayers were incubated with BrdU for 1 hour, wounded and then fixed immediately (0 hr). Other cells were incubated with BrdU for 1 hour after 11 hours of wounding and then fixed (12 hr). Nuclear DNA is counterstained with DAPI (Blue). BrdU is shown in pink. Original magnification: X100.

Validation of the wounding system for biochemical and signaling studies

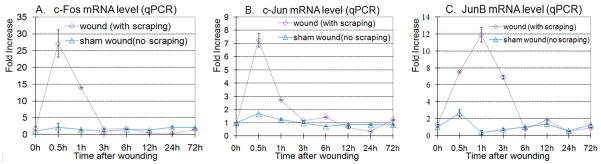

We measured the expression level of mRNA for several early response genes (c-Fos, c-Jun and JunB) at serial time intervals after wounding. Confluent BUMPT cells were wounded as described in Materials and Methods and cells were harvested after 0, 0.5, 1, 3, 6, 12, 24 and 72h. The mRNA expression level of c-Fos, c-Jun and JunB was measured by qPCR. The mRNA expression levels of all three early response genes were increased many fold between 30–60 minutes after wounding (Fig. 8), consistent with early activation of proliferative signaling. The data shown in Fig. 8 were generated using a concentrically engraved stamp that produced circular islands that were ~130 μm wide. However, we expect that expression of early response genes such as c-Fos, c-Jun and JunB and subsequent proliferation would occur with any type of wounding pattern as long as the dimensions of islands are small enough to permit rapid cell activation. Thus, we may expect similar results with islands resulting from the wounding pattern shown in Fig. 6.

Figure 8.

Cellular concentration of mRNA for c-Fos, c-Jun and Jun B measured by Q-PCR at serial time intervals after wounding. Confluent monolayers of proximal tubule (BUMPT) cells were wounded using a stamp that yielded concentric cell bands of ~130 μm width. RNA was extracted from wounded cultures and corresponding non-wounded time controls at serial time intervals. N=3.

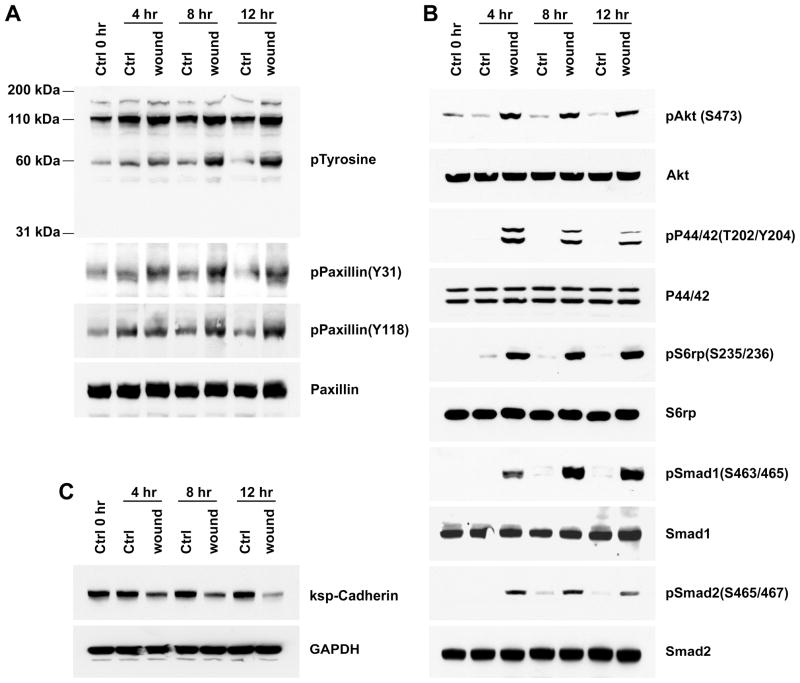

Within a few minutes to hours after wounding, cells in the contact-inhibited and differentiated epithelium became de-differentiated, migratory and proliferative. Cell activation, de-differentiation, migration and proliferation were reflected by the results of western blotting for several signaling proteins, a focal adhesion protein and an intercellular junction protein. Consistent with wound induced cell activation and stimulation of tyrosine kinase dependent signaling pathways, samples obtained from wounded cells showed increased tyrosine phosphorylation of several proteins (Fig. 9a). Proteins with increased phosphotyrosine included paxillin; in wounded cells, paxillin showed increased phosphorylation at Y31 and Y118, consistent with the role played by this focal adhesion protein in cellular migration (Fig. 9a). Wounding was also associated with increased tyrosine phosphorylation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), that we showed by immunoprecipitation of the receptor and immunoblotting with phosphotyrosine antibody (data not shown). We investigated the activity of several other signaling pathways as well. Western blotting showed that signaling through the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) and p44/42 mitogen activated protein kinase (ERK-MAPK) pathways was increased as shown by enhanced phosphorylation of Akt and p44/42 ERK respectively (Fig. 9b). Consistent with the effectiveness of the wound stimulated PI3K and ERK-MAPK signaling in eliciting downstream responses in protein synthetic machinery, wounding resulted in the phosphorylation of ribosomal S6 kinase as well (Fig. 9b). In addition, there was activation of autocrine signaling through Bone Morphogenetic Protein Receptor(s) shown by markedly increased phosphorylation of Smad1, and the transforming growth factor-beta (TGFβ) pathway evidenced by Smad2 phosphorylation, as we have reported (13) (Fig. 9b). These intense signaling activities were accompanied by steep declines of the proximal tubule intercellular adherens junction protein ksp-Cadherin consistent with the breakdown of junctions and de-differentiation of epithelial phenotype that occurred during migration (Fig. 9c). Together, these wound-elicited events indicated vigorous activation of cells at the biochemical level, responses that would be required for the complete transformation of the contact-inhibited and differentiated epithelial monolayer to a de-differentiated, migratory and proliferative phenotype.

Figure 9.

Western Blots for proteins and phosphoproteins in SDS extracts of control cells and wounded cells after 4, 8 and 12 hours. Confluent monolayers of proximal tubule (BUMPT) cells were wounded using a stamp that yielded concentric cell bands of ~130 μm width. (a) Phospho-tyrosine, phospho-paxillin and paxillin; (b) Phospho-Akt (S473), Akt, phospho-P44/42, P44/42, phospho-S6 ribosomal protein, S6 ribosomal protein, phospho-Smad1 (S463/465), Smad1, phospho-Smad2 (S465/467), and Smad2. (c) Ksp-Cadherin. The normalizing protein GAPDH applies to all blots in a, b and c.

Discussion

The new wounding device described here presents several advantages over methods that are currently used to study the regeneration of cultured epithelial cells. It is simple and rapid to use and reproducible. The dimensions of wounds and remaining cell bands are easily changed by employing stamps engraved with different wounding patterns. Most important, the wounds and cell bands are of uniform size without significant variation between dish to dish or experiment to experiment. The technique yields clear and smooth wounding beds for cells to migrate on and cell bands can be made narrow enough to induce rapid activation of the entire population of remaining cells. The mass of cells that is left behind after wounding is also sufficiently large for biochemical analysis. Typically, depending on the stamp design, ~5–20% of the original cell mass remains and our data clearly show that this was sufficient for the analysis of cellular proteins and RNA for signaling studies. Although we did not attempt to measure lipids, carbohydrates and smaller molecules such as ions, nucleotides etc, we anticipate that suitably prepared extracts of cells should be more than sufficient to permit biochemical analysis of a wide variety of metabolites, ions and other cellular components. Thus, the technique presented here is versatile enough for comprehensive biochemical profiling of epithelial regenerative behavior. Importantly, the technique would lend itself readily for investigation of proteomics by 2-D electrophoresis and mass spectrometry and genomics by microarrays.

Our results show that the speed of activation of cells that remain after wounding depends on the dimensions of the cell bands. Within several minutes of wounding by any technique, a narrow band of cells several rows wide inwards of the wound edge become ‘activated’ as visualized by microscopy. Activation commences in cells immediately at the wound edge, spreads inwards and corresponds to increased cytosolic Ca++ and increased expression of early response genes such as c-Fos (14–17). As we alluded to earlier, the large mass of wounded contact-inhibited epithelium left behind by conventional wounding methods ensures that cell activation by wounding remains restricted to a narrow band near the edge. Regenerative signaling becomes progressively diluted as it goes inwards and encounters powerful inhibitory signaling from contact-inhibited cells. This difficulty is completely avoided by wounding patterns that leave behind bands that are ~10–20 cell layers wide, allowing regenerative signaling to proceed inwards from both wound edges to meet in the middle. Thus, using our new method, cell activation is technically not synchronous, i.e., the process occurs over many minutes, but it is virtually complete by this period, after which all cells can be expected to be participating in the regenerative response. The duration for the activation process to spread completely across depends on the width of the cell band. Certainly, the activity is always more at the wound edges, but the overall extent of activation and the involvement of the entire population within relatively short periods of time is unprecedented. As such, serial sampling of cells would permit reliable study of the temporal sequence of signaling events in cells as they migrate and regenerate. With stamps designed to produce parallel wounding patterns, repeat wounding at right angles to the original wounds produces small square islands of remaining cells (see Fig. 6) that become activated with a rapidity that should enable the identification of crucial early events.

In view of the considerations discussed above, we believe that stamps designed to produce concentric wounding patterns with islands that are ~130 μm wide are suitable for most applications in the investigation of epithelial regeneration including comprehensive genomic and proteomic studies and analysis of signaling pathways. Stamps that produced concentric wounds and left behind ~130 μm wide islands were sufficient to generate reliable information on DNA synthesis (Fig. 7), expression of early response genes (Fig. 8) and altered expression and phosphorylation of several signaling proteins (Fig. 9). As we have discussed earlier, use of stamps producing islands much less than 130 μm wide more frequently results in irregular wounding patterns and undue loss of cells. We recommend stamps with parallel ridges and sequential wounding at right angles to produce “square” islands (Fig. 6) if extremely rapid and simultaneous activation of all remaining cells is desired. This would result in less dilution of a small but important response from activated cells by other cells that do get activated sequentially, but only later. We have used this method to study signaling proteins that are somewhat slow to respond to the wounding stimulus (unpublished observations). Similarly, we recommend that wound widths be modified according to the expected duration of the experiment based on the speed of migration and proliferation of the individual cell type and the age of the regenerated population at which the investigator desires to study the cells.

Our results show clearly that cells remaining after wounding are healthy as evaluated by several criteria - they become activated, migrate and proliferate; moreover, they exhibit signaling events that require the efficient operation of energy dependent processes. We have observed some variations in the response of different cell lines and cell types to wounding by the new method (data not shown). This device works best for cells that are firmly attached to the culture substrate. Cell types that are weakly attached to the substratum show a tendency to lift off the dish during the wounding procedure, particularly with stamps that produce the narrower cell bands. However, these problems could be addressed by varying the arc of rotation of the stamp during wounding, increasing the width of remaining cell islands by designing suitably engraved stamps and more careful attention of the procedure itself. A cautionary note is that following the wounding procedure, microscopic examination of the dish is advisable to ensure that wounds and cell bands are uniform. If regions with unusually wide bands are identified, they are easily denuded using a cosmetic brush such as an eyeliner or eyebrow brush. Such brushes should also be routinely used to remove unwounded cells from outmost areas of the dish at and near the flange area. Similarly, the inside surfaces of the vertical rim, especially the corners of the dish, should be wiped clean of cells growing upwards from the flange area. Staining of the culture dishes with confluent cell populations showed that large number of cells grow upwards on these surfaces (not shown). Attention to these precautions results in a remaining population that is uniformly wounded and therefore activated in a uniform manner. As a corollary, it would be advisable for beginners in this wounding technique to stain several dishes after wounding to identify imperfectly wounded areas as well as cells that are not accessed by the stamp, such as the flange areas and inner surfaces of the raised rims.

In conclusion, we present what we believe is an advance in the technique of in vitro wounding of cultured cells, one that will permit reliable biochemical, proteomic and genomic analysis of large homogeneous populations of regenerating cells in culture. The information gleaned from these studies, placed in the context of in vivo studies, should result in a better understanding of how epithelia regenerate and heal.

Acknowledgments

These studies were supported by National Institutes of Health grants DK37139 (M.A.V.) and DK54472 (P.S.).

References

- 1.Martin P. Wound healing--aiming for perfect skin regeneration. Science. 1997;276:75–81. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Werner S, Grose R. Regulation of wound healing by growth factors and cytokines. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:835–870. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2003.83.3.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Providence KM, Kutz SM, Staiano-Coico L, Higgins PJ. PAI-1 gene expression is regionally induced in wounded epithelial cell monolayers and required for injury repair. J Cell Physiol. 2000;182:269–280. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(200002)182:2<269::AID-JCP16>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sung YJ, Sung Z, Ho CL, Lin MT, Wang JS, Yang SC, Chen YJ, Lin CH. Intercellular calcium waves mediate preferential cell growth toward the wound edge in polarized hepatic cells. Exp Cell Res. 2003;287:209–218. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00160-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu KP, Ding Y, Ling J, Dong Z, Yu FS. Wound-induced HB-EGF ectodomain shedding and EGFR activation in corneal epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:813–820. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoang AM, Oates TW, Cochran DL. In vitro wound healing responses to enamel matrix derivative. J Periodontol. 2000;71:1270–1277. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.8.1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yarrow JC, Feng Y, Perlman ZE, Kirchhausen T, Mitchison TJ. Phenotypic screening of small molecule libraries by high throughput cell imaging. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 2003;6:279–286. doi: 10.2174/138620703106298527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellis PD, Hadfield KM, Pascall JC, Brown KD. Heparin-binding epidermal-growth-factor-like growth factor gene expression is induced by scrape-wounding epithelial cell monolayers: involvement of mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades. Biochem J. 2001;354:99–106. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3540099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu KP, Yu FS. Cross talk between c-Met and epidermal growth factor receptor during retinal pigment epithelial wound healing. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:2242–2248. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yin J, Xu K, Zhang J, Kumar A, Yu FS. Wound-induced ATP release and EGF receptor activation in epithelial cells. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:815–825. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turchi L, Chassot AA, Rezzonico R, Yeow K, Loubat A, Ferrua B, Lenegrate G, Ortonne JP, Ponzio G. Dynamic characterization of the molecular events during in vitro epidermal wound healing. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;119:56–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.01805.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keese CR, Wegener J, Walker SR, Giaever I. Electrical wound-healing assay for cells in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:1554–1559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307588100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geng H, Lan R, Wang G, Siddiqi AR, Naski MC, Brooks AI, Barnes JL, Saikumar P, Weinberg JM, Venkatachalam MA. Inhibition of autoregulated TGFbeta signaling simultaneously enhances proliferation and differentiation of kidney epithelium and promotes repair following renal ischemia. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:1291–1308. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacinto A, Martinez-Arias A, Martin P. Mechanisms of epithelial fusion and repair. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:E117–123. doi: 10.1038/35074643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klepeis VE, Cornell-Bell A, Trinkaus-Randall V. Growth factors but not gap junctions play a role in injury-induced Ca2+ waves in epithelial cells. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:4185–4195. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.23.4185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin P, Parkhurst SM. Parallels between tissue repair and embryo morphogenesis. Development. 2004;131:3021–3034. doi: 10.1242/dev.01253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woolley K, Martin P. Conserved mechanisms of repair: from damaged single cells to wounds in multicellular tissues. Bioessays. 2000;22:911–919. doi: 10.1002/1521-1878(200010)22:10<911::AID-BIES6>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]