Abstract

Background

Engaging youth and incorporating their unique expertise into the research process is important when addressing issues related to their health. Visual Voices is an arts-based participatory data collection method designed to work together with young people and communities to collaboratively elicit, examine, and celebrate the perspectives of youth.

Objectives

To present a process for using the creative arts with young people as a participatory data collection method and to give examples of their perspectives on safety and violence.

Methods

Using the creative arts, this study examined and illustrates the perspectives of how community factors influence safety and violence. Visual Voices was conducted with a total of 22 African-American youth in two urban neighborhoods. This method included creative arts-based writing, drawing, and painting activities designed to yield culturally relevant data generated and explored by youth. Qualitative data were captured through the creative content of writings, drawings, and paintings created by the youths as well as transcripts from audio recorded group discussion. Data was analyzed for thematic content and triangulated across traditional and nontraditional mediums. Findings were interpreted with participants and shared publicly for further reflection and utilization.

Conclusion

The youth participants identified a range of issues related to community factors, community safety, and violence. Such topics included the role of schools and social networks within the community as safe places and corner stores and abandoned houses as unsafe places. Visual Voices is a creative research method that provides a unique opportunity for youth to generate a range of ideas through access to the multiple creative methods provided. It is an innovative process that generates rich and valuable data about topics of interest and the lived experiences of young community members.

Keywords: Youth, CBPR, community, creative arts, community engagement, safety, health

In the United States, youth face significant health and health disparities. For example, homicide is the leading cause of death among 15- to 24-year-old African American males.1 Young people are at persistent risk for HIV infection and minorities account for 55% of all HIV infections among persons ages 13 to 24.2 In 2006, 9.9 million U.S. adolescents under 18 years of age (14%) were diagnosed with asthma. To implement effective early intervention and prevention efforts to address such issues, it is essential to understand and address the contextual, social and physical health experiences of youth.3,4

The challenge of how to engage community members in equitable partnerships is especially true when involving youth. Although there are a few notable examples for engaging youth in a manner designed to foster a participatory research approach, relatively little work in this area exists.5–7 More than two decades have passed since Delgado argued that youth should play a larger role in social science research and since then little progress has been made toward including youth as key health research partners.8,9 However, select exemplary research studies which have embraced youth do exist. For example, Streng and associates10 employed photovoice to examine the experiences of Latino(a) high school adolescents living in rural North Carolina. This approach allowed local youth to reflect on their social and structural experiences with peer relationships, academic training, culture, and racism. In addition, youth-led community-based participatory research (CBPR) efforts have been found to assist service providers in advocating for youth issues within their agencies where competing interests and agendas often made it difficult to focus attention on youth needs.11

Understanding and assessing the complex dynamics of health and wellness of youth is a challenging process, especially given the intimate developmental and social dynamics experienced in childhood and adolescence. This period of development is often marked by the processes of developing personal and social identity, with the formation and cultivation of relationships with peers, adults, and their environment.12,13 Engaging youth and incorporating their unique expertise into the research process is essential to informing and developing culturally relevant and sensitive health intervention and prevention efforts.

As the field of CBPR evolves, there is a need to develop and examine innovative participatory methods and frameworks for engaging young people and communities. This paper describes a creative arts-based participatory research method called Visual Voices that is grounded in the understanding that community members are experts in their own lives. The method integrates principles of CBPR and builds on prior work suggesting that the creative arts process is an ideal method for integrating the perspective of youth and community experience.5,14,15

Originally created in 1993, Visual Voices was designed as an initiative to bring youth together within a common artistic venue. More recently, the method has been used as a participatory method for working with communities. Participants address issues concerning their lives, communities, and their futures through paintings, drawings and writings. The method combines these efforts into one “visual voice” final exhibit from which participants, community members and the public are able to celebrate, reflect, and learn. To date, Visual Voices has been conducted in nine cities in the United States in collaboration with after-school programs, community-based organizations, and in classroom settings involving the efforts of more than 1,200 adolescents and young adults. Participants have varied widely in age and location but the most common group has been young people between the ages of 7 and 12. The method strategically uses materials that are accessible to the community such as affordable paints, paper, brushes, and markers. The following sections provide a description of the Visual Voices method and an overview of research findings from recent applications of the method in Baltimore, Maryland, and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

METHODS

The research presented in this article is the combination of two distinct, yet complementary and related community partnered research efforts. The first project, implemented in Baltimore, Maryland, in the Summer of 2007, was a research partnership that received funding from the Center for Injury Research and Policy at The Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health. The second project was implemented in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in the fall of 2008, and was a research partnership supported by funding from the University of Pittsburgh Clinical and Translational Science Institute. Both projects were designed to explore the perceptions of youth regarding community factors on safety and violence. The topic of community safety, research questions, research ethics considerations, and priorities of the project were developed in full collaboration with the community research partners at both sites. The projects received approval from the appropriate Institutional Review Boards (The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health IRB [protocol #280] and University of Pittsburgh IRB [protocol #PRO08060430]).

Community Partners

All project-related decisions, from the content and implementation of human subjects’ research materials to the timing and content of the sessions, were achieved through a consensus guided format that included expertise from both academic and community partners. Participating youth were involved with guiding the direction and implementing each phase of the creative participatory data collection sessions once the project began. In Baltimore, Maryland, academic researchers partnered with community members from EDEN Jobs, a Ministry of New Song Urban Ministries to conduct the project. EDEN Jobs is a nonprofit career development and employment placement organization component of New Song Urban Ministries located in West Baltimore, Maryland. In the summer months, EDEN Jobs coordinates a summer youth activities program. A 7-year relationship of the academic and community partners developed during a prior research effort in 2002 related to youth violence and provided the basis for this CBPR effort.16–18 Community research partners in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, were developed through existing collaboration between the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Braddock Hospital, and residents of a local public housing community after-school program.

Participants

The partnership between academic researchers and community members was expanded to include youth from the two communities. In total, 22 African American youth participants from the two locations participated. In both locations, youth who attended extracurricular programs offered by community organizations were invited to participate in the project. The youth participants from Baltimore, Maryland, were from a low-income urban community and attended a local school program. The group from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, lived in a subsidized housing community and attended an after-school program. The two groups were similar demographically. For both sites, the age eligibility ranged from 8 to 15. The Baltimore sample included five girls and four boys, ages 8 to 14. The Pittsburgh sample included nine girls and four boys, ages 11 to 15 years. Written parental consent and youth assent was obtained for all participants before the initiation of any research activities.

Visual Voices Method

Visual Voices is an arts-based method that uses multiple sessions to address a focal area. Table 1 provides a brief overview of the creative Visual Voices session goals and related activities. Specifics about the application of this method can be obtained by contacting the authors of this paper. This creative method addresses several of the principles of CBPR and was used to specifically extend the partnership approach to collaborating with the young people.5 For example, the activities facilitate collaborative and equitable involvement of all partners including the youth participants and the adult facilitators. In Baltimore, the sessions occurred over 4 consecutive days. In Pittsburgh, the sessions occurred over 8 weekly sessions. At both sites, the focused sessions addressed the places in their communities where the young participants feel safe and unsafe. Each session consisted of a general overview discussion, followed by an art activity (either painting or drawing), and a group “critique” or discussion of the work generated.

Table 1.

Overview of Visual Voices Sessions

| Session | Goal(s) | Activities |

|---|---|---|

| Session 1: Introduction to Visual Voices | Introduce the Visual Voices method and process. Establish the ground rules and guidelines necessary for creating a safe and supportive creative working environment. |

Ice-breaker drawing activity and associated discussion of how every participant expresses themselves differently and that no one way is correct. |

| Session 2: Hopes and dreams for the future | Introduce the painting activity and explore participant’s hopes, dreams and visions for the future. | Painting about hopes, dreams and visions for the future. Facilitated critique/group discussion of the paintings. |

| Sessions 3–5: Focal topic (painting) | Introduce the focal topic and explore participant perceptions regarding the focal topic through painting. | Painting about the focal topic. Facilitated critique/group discussion of the paintings. |

| Sessions 6–7: Focal topic (writing) | Explore participant perceptions regarding the focal topic through drawing and writing. | Drawing and writing about the focal topic. Facilitated critique/group discussion of the drawings/writings. |

| Session 8: Becoming agents of change and wrap up | Summarize the ideas and issues covered in previous sessions. Discuss next steps and actions. |

Select paintings and drawings/writing to be included in final product. Discuss exhibition and dissemination opportunities. |

During painting sessions, the young people sat on a large tarp that covered the floor and painted on brown craft paper precut into approximately 3 ×5-foot segments. Paint and brushes were provided for each participant, but the number of paint cups was purposefully restricted so that the young people would be encouraged to share. At the end of the painting sessions, a structured and facilitated critique/discussion session was conducted by selecting paintings and holding them in front of the group for reflection, feedback, and praise. The group collectively reflected on the content of the painting and the exchange was facilitated by the academic research partners, a modified approach to a standard focus group process.19 The facilitated discussion is directed at exploring how the group feels about the content of each creative work and collective reflection is fostered. After the group discussion, the individual artist is invited to voluntarily share their thoughts as well.

The writing and drawing sessions were conducted with the young participants sitting at tables. Each participant was given white, letter-size paper and marker and asked, based on their comfort level, to write or draw or do both. A group discussion similar to that employed during the painting sessions was used to examine the content of the writings and drawings. In addition, photographs were taken of the academic and community partners as they worked together during the creative activities to visually document the process. To extend the partnership to include young people and engage their unique expertise, experience and cultivate capacity, participants are encouraged and guided to first co-facilitate and then independently facilitate the different painting, writing, drawing, and critique phases of the process. For example, by the second or third session, young participants are most often independently leading the discussion critiques of the work by choosing a painting, standing in front of the group, and guiding the group reflection and learning process.

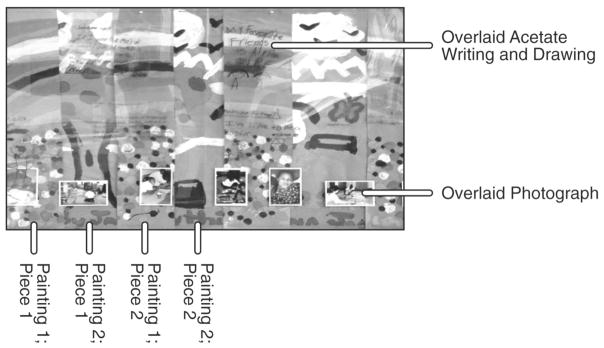

Upon completion of the painting and writing sessions, the participants were invited to help build the Visual Voice display piece. This process of “building the piece” is one that has been used previously to construct the final display. The participants were asked to look at the collected works and determine which pieces they want to include and in what order. The final exhibit integrated the different creative products from each session into a collaged exhibition, creating one “visual voice.” Construction began with dividing the dried paintings into approximately 8-inch vertical strips. Consecutive segments from each painting were retained and kept together within the final exhibition. Segments from each painting are then alternated to form a collage. Next, participants’ writings and drawing were photocopied onto clear plastic transparencies and the photographs taken during the sessions were printed in black and white. The clear acetate sheets were then taped onto thin plexi-glass sheets that hang in front of the collaged paintings and the photographs were taped along the bottom of the plexi-glass sheets. This layering allows the paintings and writings to be viewed together, as one final collaged exhibition of the participants’ work, thoughts and feelings (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Final Exhibition Example

Analysis

All participant paintings were digitally photographed and writings and drawings were scanned and then entered into the qualitative data analysis program software, NVivo, v.8. Audio recordings of the group critiques/discussions were transcribed verbatim and similarly compiled.

Consistent with qualitative data analysis methods, the data sources were iteratively reviewed and coded for themes generated by the youth.19 Certain themes, such as safe/not safe, were determined a priori. The majority of coding occurred as a result of the participant-guided priorities as exemplified in the paintings, writings, drawings, and related group discussion, such as codes related to specifics and details like “nighttime” and “vacant housing” as unsafe factors. Therefore, subthemes emerged in situ and new themes that crosscut topics were also evident.

The youth participants, after-school program staff and volunteers, parents, and other interested community members met with the academic investigators at the end of the activities to review findings and to facilitate interpretation. Public discussion forums were conducted with participants at each project site to further assist with interpreting and contextualizing findings. For example, in Pittsburgh findings were presented to local parents and to the local police department leadership to further explore findings and potential intervention opportunities. In Baltimore and Pittsburgh, a piece of the local final collage display was mounted in both a community and academic setting. For example, in Pittsburgh a piece was displayed at the UPMC Braddock Hospital and at the local public housing community after-school program.

RESULTS

The following section presents select findings from the Baltimore and Pittsburgh projects. These findings specifically address young people’s reflections on places that are safe and not safe within their communities.

Contextual and structural Factors: Safe

Young people from Baltimore consistently described their school as a safe place and as a place with caring teachers, staff, coaches and people who protect and keep you off the streets. It is a place where no gang or drug activity is tolerated. As one participant stated, “my school … we feel safe … a safe place because of the teachers, there are no [gangs], and no drugs.” Safe was additionally depicted as a locale—church is a place where people go together and it is peaceful. Participants also created many pieces depicting nature, the sky, and clouds, which were also to them peaceful.

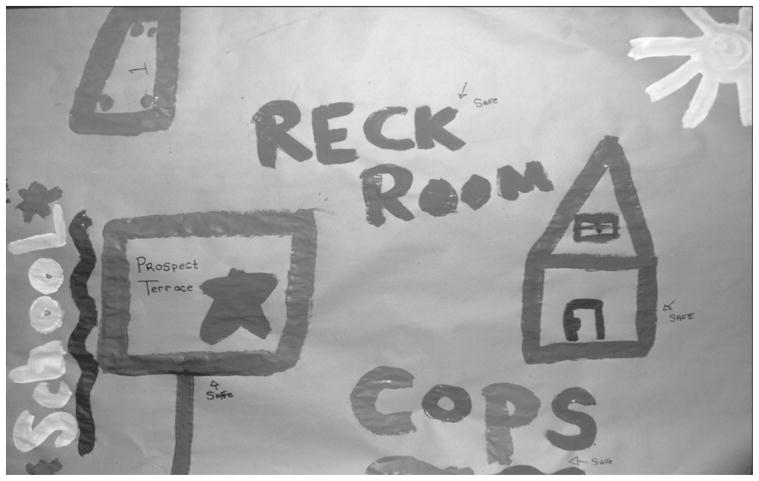

In a similar way, the young people in Pittsburgh painted about school as a safe place (Figure 2) where “teachers protect you.” However, during the critique session school was discussed as being both a safe and a not safe place: “well at our school, sometimes they just … walk through [metal scanners] beeping and you never know what they got. That’s not safe.” Although the youth participants did not talk of having experienced a shoot-out at school, there is belief that it is a possibility. The data from these sessions also illustrated some ambiguity over the perceived benefit of local services such as school, police, and the hospital. Although these organizations are there to help the community, they at times may pose a threat. Hospitals were recognized as a place that might make you sick. The police were thought of as safe, but not always—“some are racist.”

Figure 2. Safe Places.

Painting example of Safe Community Factors.

The importance of social networks was another common theme across groups. In Baltimore, safety was found in social networks which were seen as a strong part of the local community. This sentiment was articulated in the following quote, “what I like about Sandtown is how people always lookin’ out for you.” For the youth in Pittsburgh, the majority of references were to family and friends and how they are some of their favorite people and the people they like to do things with. As one participant wrote “I [heart] my family. The reason why these are my favorite people. Because they always love me. And they been there for me. And they never doubt me. That’s why these are my favorite people.”

Contextual and structural Factors: Not Safe

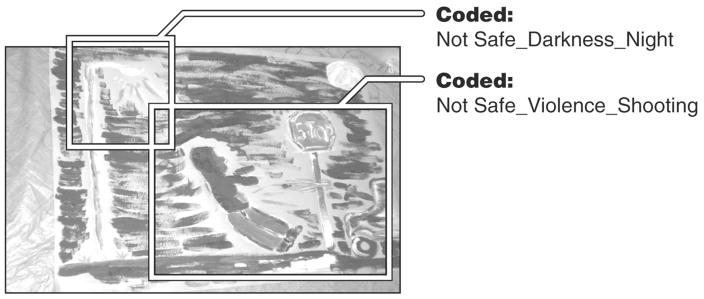

Places that are not safe for the Baltimore group included corner stores where bad things happen: drug selling, fighting, too many people “hanging out” make it dangerous and unsafe. Poor street and alley lighting (Figure 3) were also felt to be dangerous places where robbery, harassment and shootings could occur. One participant describes their thoughts, “drive by shootings, right, it comes across my mind when you walk outside.”

Figure 3. Nighttime.

Painting example of Not Safe Community Factor.

Another not safe community factor was abandoned houses, which were unsafe for both structural and contextual reasons. The abandoned houses were unsafe structurally because they had broken steps, exposed rusty nails, dilapidated conditions, and left over needles from drug use. They were unsafe contextually because they were places where people, older and younger, gathered and where fights and drug sales were common. One youth noted “people like go in abandoned houses and it’s not safe … [there are] broken steps, they do drugs there … leaving needles.”

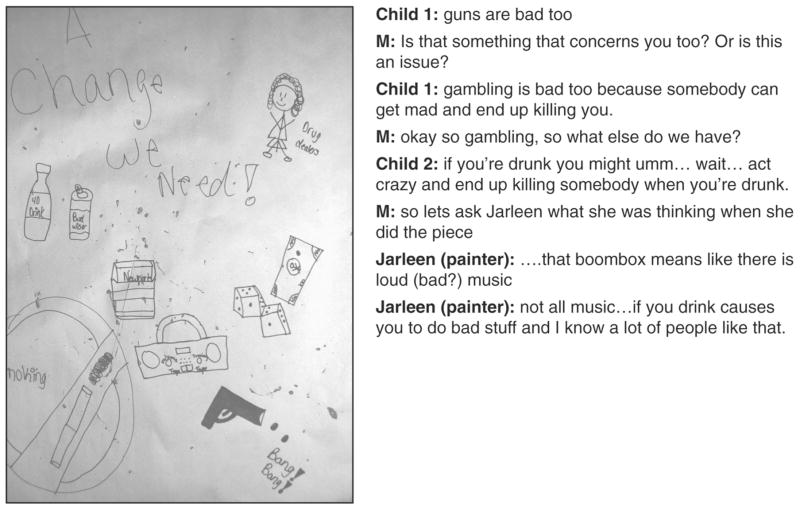

In Pittsburgh, not safe was most often associated with contextual factors and prominent among them were drugs, guns and violence, smoking, drinking, and gambling. Many of the thoughts shared were summarized in content and discussion represented in Figure 4. The images created in this piece by one young female participant not only captured those of others, but facilitated a group discussion and consensus about the unsafe factors facing young people living in their neighborhood. A description of what was in the painting included “I see a forty … I see a Bud … I see Newports … I see guns … I see, umm, dice.” It was noted that the danger in drinking, loud music, and gambling was that it might progress into violence and the use of guns. One participant from Pittsburgh said “you can have a half of that glass but people here they be like, they start to fight, then they get their guns out, then they start shooting, then the police come. Then the little kids have to run inside.” It should be noted that although overt exposure to violence is relatively low, there is concern generated by tangential experience.

Figure 4. Not Safe Places.

Painting example of Safe Community Factors with group discussion text.

DISCUSSION

Visual Voices is an arts-based participatory research method that can be used to engage young community members and to facilitate equitable involvement in CBPR. This systematic method included distinct creative writing, drawing and painting activities designed to yield culturally relevant data generated and explored by young people. The method provides a unique opportunity for young people to inform, implement, and interpret and guide the application of research findings. It is an innovative process that generates rich and valuable data about topics of interest and the lived experiences of community members.

The method productively engaged a group of young people in a research project and was successful in identifying and illustrating specific positive and negative community characteristics associated with safety. The specific illustrations and related discussions were informed by the youth themselves with the only “prompting” from facilitators being a reminder to (a) have fun, (b) respectfully share the materials and space, and (c) focus on community-level features that they considered to be safe and not safe. The youth participants, as co-facilitators, identified a range of issues related to community factors, community safety and violence. Results from follow-up focus group discussions with participants in the Visual Voices process suggest that this method is well-received for a variety of reasons, including involvement and flexibility of the different creative painting and drawing activities, the feedback they received from structured reflection and feedback sessions, and that it was simply and maybe most importantly, fun.20 Researchers interested in partnering with young people to address complex public health issues should consider using this approach.

Results from the projects provide valuable information about the young community members’ lived experiences and provide unique insights into their perspectives. Although more traditional research methods such as surveys or focus group discussions could be used with youth, the information obtained through this arts-based approach is likely to have more depth given the multiple opportunities for exploration and discussion.9 Visual Voices shares more in common with the photovoice method where cameras are placed in the hands of the community members and through a rigorous process, enables them to reflect on community strengths and weakness in order to engage in a dialogue about important issues related to their locality.3,4,10 However, unlike photovoice, which requires a certain level of comfort with technology such as cameras, the Visual Voices method uses creative approaches (paint, markers), which are common, comfortable, and familiar to children of all ages.

The observation that an arts-based method appears appropriate for CBPR with young people is consistent with existing research on creative arts and community development.21,22 Matarasso23 found participation in locally run community heritage festivals resulted in youth expressing positive feelings about their community, culture, and language. The study also found that 41% of participants interviewed stated they wanted to help in other local projects. Additionally and consistent with this method, community-based creative arts programs offer an opportunity for increased interaction and dialogue around unique and subtle community health and safety issues.9,14 These opportunities can be important for the individual as well as the community by providing group space for expression of personal beliefs, important community issues, and ethnic pride.9, 24, 25

Designed to include multiple sessions utilizing both written and painted mediums, Visual Voices permits both individual and group processing and expression. This use of multiple forms of expression is a strength of the method and allows the participants to share their thoughts and perspectives in the manner they feel most comfortable. For example, whereas participant A may feel most comfortable creating an abstract painting and then talking about it, participant B may feel most comfortable writing down her thoughts. Visual Voices is also unique in that it includes both individual and group oriented activities. Participants first are asked to individually develop their paintings and/or writings and are then asked to share them with the group. This process of group sharing can permit the other participants to reflect on their own similar thoughts and perspectives and contribute to a broader discussion. In addition to being a developmentally flexible and appropriate forum for engaging in participatory research, the Visual Voices method is fun, nontraditional, and provides multiple process and outcome opportunities for community, adult, youth, and academic partners to lead the project and process. The intimate process of working together over several sessions lays the groundwork for relationships to develop between the academic researchers and the community participants. In addition, the Visual Voices method fosters the development of trust and helps to build relationships between academic researchers and community members. The formation of partnerships is a core component of CBPR and something that needs to be nurtured.

Although the Visual Voices method was used in these two locations primarily as a research data collection tool, the approach can itself be viewed as an intervention. For example, throughout the process the facilitators can, given the appropriate backgrounds and experience, help the youth participants to explore specific issues and to address some of the public health problems that that they describe. The method has been used as just such an intervention tool to address the issue of dating violence among adolescent middle school children to facilitate discussions of violent experiences and to visualize and explore nonviolent solutions.26 For these two projects, the participatory data collection findings have led to a number of short-term yet developing prevention efforts. For example, in Pittsburgh findings have been presented and productively received by the local police department leadership to inform mutual understanding of young peoples’ perceptions of safety issues and as a potential opportunity to develop new and nontraditional communication. In Baltimore, as designed by the team, the project findings were adapted and used by the organizational leadership of EDEN Jobs.

There are some unique challenges associated with using the Visual Voices method. One limitation is that the process is time consuming and resource intensive.11 In addition, it requires adequate space and community time for the painting and writing sessions. Although previous creative-arts based experience is absolutely not required to facilitate this method, it is necessary that the community and academic research partners are comfortable working with the different media, facilitating discussions, and working with the different types of qualitative data and data analytic techniques. Finally, like other qualitative data collection techniques, the generalizabilty of findings are limited. Cultivating and integrating youth expertise in research through CBPR does come at a noted price.11 Participation costs included heavy demands of time, an added burden of work, frustration with the process, missing other opportunities, risking loss of anonymity, and loss of perceived control. Special considerations and actions need to be taken to ensure that clear benefits are realized for all project partners and that the burden is minimized.

Visual Voices is an arts-based participatory research method to facilitate young community member engagement, uncover and celebrate their expertise, inform future community-engaged research and guide intervention and prevention efforts. Our application of Visual Voices serves as an example for how this arts-based participatory method can be adapted and used in future CBPR work with youth.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this research was provided by CDC Grant No. R49 CE00198 from the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control to the Johns Hopkins Center for Injury Research and Policy and the University of Pittsburgh Clinical and Translational Science Institute Grant No. UL1 RR024153.

The authors sincerely thank all of the young creative youth research partners, adult community and academic research partners, especially Ms. Ronnica Sanders, Mr. Gerry Palmer, Ms. Lisa Guzzetti, Ms. Cara Nikolajski, and Dr. Steve Reis, that have made this partnered research effort possible and exceptionally educational for all.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; [Accessed September 24, 2009]. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) [Internet] from: http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report, 2004. Vol. 16. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strack RW, Magill C, McDonagh K. Engaging youth through photovoice. Health Promot Pract. 2004;5(1):49–58. doi: 10.1177/1524839903258015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang C, Burris MA. Empowerment through photo novella: Portraits of participation. Health Educ Behav. 1994;21(2):171–86. doi: 10.1177/109019819402100204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, editors. Methods in Community-based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wallerstein N, Duran BM, Aguilar J, Joe L, Loretto F, Toya A, et al. Jemez pueblo: Built and social-cultural environments and health within a rural American Indian community in the southwest. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(9):1517–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.9.1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flicker S, Goldberg E, Read S, Veinot T, McClelland A, Saulnier P, et al. HIV-positive youth’s perspectives on the internet and e-health. J Med Internet Res. 2004;6(3):32. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6.3.e32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delgado M. Using Hispanic adolescents to assess community needs. J Contemp Soc Work. 1981;62:607–13. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delgado M. Designs and methods for youth-led research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Streng JM, Rhodes SD, Ayala GX, Eng E, Arceo R, Phipps S. Realidad Latina: Latino adolescents, their school, and a university use photovoice to examine and address the influence of immigration. J Interprof Care. 2004;18(4):403–15. doi: 10.1080/13561820400011701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flicker S. Who benefits from community-based participatory research? A case study of the positive youth project. Health Educ Behav. 2008;35(1):70–86. doi: 10.1177/1090198105285927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Erikson EH. Identity, Youth, and Crisis. New York: W. W. Norton; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Youniss J, Yates M. Community service and social responsibility in youth. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bailey DB, Buysse V, Smith T, Elam J. The effects and perceptions of family involvement in program decisions about family-centered practices. Eval Program Plan. 1992;15(1):23–32. [Google Scholar]

- 15.McDonald M, Sarche J, Wang C. Using the arts in community organizing and community building. In: Minkler M, editor. Community Organizing and Community Building for Health. 2. Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 2004. pp. 346–64. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yonas MA, O’Campo P, Burke JG, Peak G, Gielen AC. Urban youth violence: Do definitions and reasons for violence vary by gender? J Urban Health. 2005;82(4):543–51. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yonas MA, O’Campo P, Burke JG, Gielen AC. Neighborhood-level factors and youth violence: Giving voice to the perceptions of prominent neighborhood individuals. Health Educ Behav. 2007;34(4):669–85. doi: 10.1177/1090198106290395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yonas MA, O’Campo P, Burke JG, Gielen AC. Exploring local perceptions of and responses to urban youth violence. Health Promot Pract. 2008 Mar 28; doi: 10.1177/1524839907311050. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ulin PR, Robinson ET, Tolley EE. In: Qualitative Methods in Public Health: A Field Guide for Applied Research. Robinson ET, Tolley EE, editors. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burke JG, Yonas MA, Nikolajski C, Gielen AC. Developing an Evaluation of Visual Voices: An arts-based initiative. Personal communication] International Conference on Urban Health; Baltimore, MD. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cleveland W. Making Exact Change: How U.S. arts-based programs have a significant and sustained impact on their communities. [Accessed September 23, 2009];Art in the Public Interest. 2005 November; from: http://www.communityarts.net/readingroom/archive/mec/index.php.

- 22.Gasman M, Anderson-Thompkins S. A renaissance on the east-side: Motivating inner-city youth through art. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk (JESPAR) 2003;10:8(4):429. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matarasso F. The Social Impact of Participation in the Arts. Comedia, The Round, Bournes Green; Stroud, London: 1997. Use or Ornament? [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newman T, Curtis K, Stephens J. Do community-based art projects result in social gains? A review of the literature. Community Development Journal. 2003;38:310–22. [Google Scholar]

- 25. [Accessed August 27, 2009];The Listening Tour. from: http://www.listeningtour.org/FinalReport.pdf.

- 26.Yonas M, Lary H, Fredland N, Glass N, Campbell J, Sharps P, et al. An arts based initiative for the prevention of dating violence in African American adolescents: Knowledge synthesis, theoretical basis, and evaluation design. In: Whitaker DJ, Reese LE, editors. Preventing Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence in Racial and Ethnic Minority Communities: CDC’s Demonstration Projects. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2007. [Google Scholar]