Abstract

A new magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast agent based on the trimetallic nitride templated (TNT) metallofullerene, Gd3N@C80, was synthesized by a facile method in high yield. The observed longitudinal and transverse relaxivities, r1 and r2, for water hydrogens in the presence of the water-soluble gadofullerene 2, Gd3N@C80(OH)~26(CH2CH2COOM)~16 (M = Na or H), are 207 and 282 mM-1s-1 (per C80 cage) at 2.4 T, respectively; these values are 50 times larger than those of Gd3+ poly(aminocarboxylate) complexes, such as commercial Omniscan® and Magnevist®. This high 1H relaxivity for this new hydroxylated and carboxylated gadofullerene derivative provides high signal enhancement at significantly lower Gd concentration as demonstrated by in vitro and in vivo MRI studies. Dynamic light scattering data reveal a unimodal size distribution with an average hydrodynamic radius of ca. 78 nm in pure water (pH = 7), which is significantly different from other hydroxylated or carboxylated fullerene and metallofullerene derivatives reported to date. Agarose gel infusion results indicate that the gadofullerene 2 displayed diffusion properties different from that of commercial Omniscan® and those of PEG5000 modified Gd3N@C80. The reactive carboxyl functionality present on this highly efficient contrast agent may also serve as a precursor for biomarker tissue-targeting purposes.

INTRODUCTION

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a rapidly evolving noninvasive diagnostic tool that provides high quality anatomical images of soft tissue and with the application of contrast enhancement agents, clear delineation of tumors and other pathological processes (1). Currently used MRI contrast agents are mainly gadolinium poly(aminocarboxylate) chelates with non-targeted biodistribution and limited chelate-site interaction with water, resulting in reduced flexibility. These nonspecific agents accumulate passively throughout the body and are normally excreted intact through the kidneys. In brain imaging, impairment of the blood-brain barrier allows for preferential contrast accumulation in tumor areas and hence for improved lesion delineation if sufficient contrast agent is present. Since the free metal ion is toxic, complexation with a multi-dentate diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA) ligand (2, 3) provides a high safety margin against dissociation of the contrast complex. However, recent reports show that the use of these agents increases the risk of the development of a serious medical condition, nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) in patients with acute or chronic severe renal insufficiency and patients with renal dysfunction (4). Therefore, there is a continuing need for safer gadolinium-based contrast agents with higher sensitivity (relaxivity) and target specificity to increase the ability for the molecular/cellular diagnosis (5-8). To address these issues, efforts have been directed mainly toward the development of alternative contrast materials. For example, Gd-chelated contrast agents with higher relaxivity than Gd-DTPA or Gd-DTPA-BMA, gadobenate dimeglumine (Gd-BOPTA, MultiHance; Bracco Imaging SpA, Milan, Italy) (9, 10) have been approved. Though the structure of the gadobenate ion (one extra benzyloxymethyl group) differs slightly from that of the widely used gadopentetate ion, this leads to a slightly higher longitudinal relaxivity for the gadobenate ion (4.39 ± 0.01 vs. 3.77 ± 0.01 mM-1s-1, 0.5 T) (10). More importantly, the same gadobenate dimeglumine concentration in serum causes a markedly higher r1 relaxivity than is observed in water or saline in comparison with other conventional gadopentetate dimeglumine (9.7 vs. 4.8 mM-1s-1) as a result of weak and transient interactions with serum albumin (10-12). Another important example is gadofosveset (MS-325), which is the first representative member of receptor-induced magnetization enhancement (RIME) contrast agents targeted to the vasculature by exploiting noncovalent binding to the plasma protein of human serum albumin (HSA) (13-15) and has been approved in the EU. The relaxivity of MS-325 in human plasma is not constant as a function of concentration and decreases from 45 to 30 mM-1s-1 (20 MHz) from 0.1 to 1 mmolL-1, respectively (14), much higher than that of clinically used Gd-DTPA (4.6 mM-1s-1)(14).

Very recently, it has been found that water soluble gadofullerenes (16-25) and gadonanotubes (26) exhibit much higher relaxivities than commercial Magnevist® (gadolinium-diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid, Gd-DTPA) and Ominiscan® (Gd-diethylenetriaminepentaacetate-bismethylamide). Most significantly, the fullerene cage is believed to hinder both chemical attack on the lanthanide ion and the escape of the lanthanide ion, which should effectively suppress the toxicity of naked Gd3+ ions. Moreover, the bio-distribution can be improved by modifying the cages with biologically active groups that exhibit high and specific affinity for a particular tissue, resulting in accumulation of targeting probes and thus local contrast enhancement (27, 28). To date, there are three basic types of Gd-based metallofullerenes reported as potential MRI contrast agents, i.e., Gd@C82 (16-20, 22, 27), Gd@C60 (21), ScxGd3-x@C80 (x = 0, 1, 2) (23, 24, 29). Among these materials, Gd3N@C80 potentially exhibits the highest relaxivity in units of mM-1s-1 per mM of gadofullerene molecules because of the presence of three Gd+3 ions/ molecule.

Herein, we report that Gd3N@C80 reacts with an acyl peroxide to produce a highly water soluble derivative, Gd3N@C80(OH)~26(CH2CH2COOM)~16 (M = H or Na), in high yield. Since the paramagnetic Gd atoms preclude using standard high resolution NMR to confirm the structure of these nanomaterials, we have employed Sc3N@C80 as a diamagnetic model and synthesize its analog, Sc3N@C80(OH)~33(CH2CH2COOM)~19, M = Na or H. This acyl peroxide free radical procedure allows for the chemical attachment of a variety of functional groups to the carbon cage through covalent carbon-carbon bonds without destroying the cage. Most importantly, the functionalized Gd3N@C80 exhibited promising properties as an MRI contrast agent, such as significantly high relaxivity, narrow size distribution and diffusion properties different from Ominiscan® in agarose gel, a brain-mimicking material. The in vivo experimental results suggest that the long-term stay of this contrast agent around the tumor will benefit for the long term diagnostics. Based on other examples in the literature (30, 31), these functionalized Gd3N@C80 compounds also could exhibit antioxidative properties.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Gd3N@C80 were synthesized and purified as reported (32, 33). Succinic acid acyl peroxide (1) was synthesized according the literature (34).

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopic (FTIR) measurements were performed using a Nicolet magna-IR750 spectrometer. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements were taken with a PHI Quantera SXM scanning photoelectron spectrometer microprobe using Al Kα radiation. The concentration of Gd3+ ion in the aqueous solutions was determined by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES, VARIAN) at 342.247 nm. The relaxation times were measured at three different magnetic field strengths: 0.35 T with a TEACH SPIN PS1-B instrument, 2.4 T with a Bruker/Biospec system and 9.4 T with a Varian Inova 400 unit. The inversion-recovery method was used to measure T1 and the Carr-Pucell-Meiboom-Gill method was used for measurement of T2. The relaxivities (r1 and r2 in mM-1s-1) in aqueous solution (pH = 7) and phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH = 7.4) solution were obtained from linear least-squares determinations of the slopes of relaxation rates (1/T1 and 1/T2) vs. [Gd3N] plots. T1-weighted and T2-weighted images of gadofullerene solutions were obtained at a 34, 14 and 7 μM of Gd3N@C80(OH)~26(CH2CH2COOM)~16 in pure water and PBS solutions, compared with 1.0 and 0.5 mM Omniscan® on the 2.4 T MR instrument using a spin-echo pulse sequence with pulse repetition time/echo times TR/TE, 700 ms/13 ms and 6000 ms/100 ms, respectively. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements were carried out with a Spectra-Physics HeNe laser producing vertically polarized light of λ0 = 632.8 nm and the correlator consisting ca. 288 exponentially spaced channels (ALV/CGS-3 multiple tau correlator) at six different scattering angles (30, 45, 60, 75, 90 and 105°). Each sample was filtered with a 0.2 μm cellulose acetate membrane filter. The CONTIN analysis was used to obtain a hydrodynamic radius based on a diffusion coefficient and size distribution. Infusion into 0.6 % agarose gel was carried out with solutions of gadofullerene 2 and the commercial agent Omniscan® using the convection-enhanced delivery (CED) method.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

Synthesis of Gd3N@C80(OH)x(CH2CH2COOM)y (M = H, Na) (2)

For the biomedical application of the fullerenes and endofullerenes, modification of these hydrophobic materials to provide water solubility is essential. Several methods has been reported to modify the precursors of MRI contrast agents, including strong base treatment (18), electrophilic reaction or radical reaction (22, 24) and multistep Bingel reaction (21, 23). However, to date, carboxylic acid and amino functionalized Gd3N@C80 have not been reported, even though these functional groups are of special importance for the tissue-targeting purposes (23, 24). Herein, we report a facile method to modify Gd3N@C80 with carboxylic acid terminal groups (Scheme 1). Briefly, to Gd3N@C80 (4 mg) in 5 mL of o-dichlorobenzene was added succinic acid acyl peroxide (1) (3.2 mg, 5 eq). The resultant solution was deaerated with flowing argon and heated at 84 °C for 48 h. In intervals of 12 h, more 1 (3.2 mg, 5 eq) was added. After the reaction, a brown sludge precipitated from the solution. Then 8 mL of 0.2 M NaOH aqueous solution were added to extract the water soluble product. Two layers were obtained; the top layer was deep brown and the bottom layer was colorless (Figure S1a). The top layer was concentrated and the residue was purified via a Sephadex G-25 (Parmacia) size-exclusion gel column with pure water as eluent to obtain a narrow brown band with pH = 6~7 (Figure S1b). The yield was 95 % estimated from the ICP calibration. The solubility of the final product in pure water is ca. 13.2 mg/mL. This fraction was characterized by XPS, FT-IR and studied in detail as an MRI contrast agent.

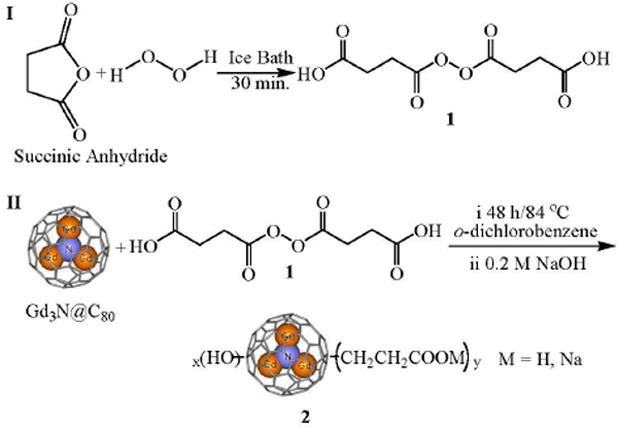

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of succinic acid acyl peroxide (1) (34) and Gd3N@C80(OH)x(CH2CH2COOM)y (M = H, Na) (2).

In a separate experiment, the Gd3N@C80(OH)x(CH2CH2COOM)y (M = H, Na) sample 2, was placed in a dialysis membrane (MW cutoff 500 D) and dialyzed for 24 hours. The resulting solution outside the membrane was subjected to ICP analysis and Gd+3 ion was not detected.

Structural Characterization

The electronic structure of the functionalized gadofullerene 2 was analyzed by measuring the binding energy spectrum for the C1s electrons. The main line of the XPS spectrum (Figure S2a) exhibits a broad and asymmetric line-shape. Gaussian analysis suggests the presence of at least three components (indicated by blue, green and purple lines, respectively). The intensities of C1s components in 2 were estimated from integration of the peak area under each line to be 66.4, 20.9 and 12.7% for the sp2 nonfunctionalized carbon (C=C) and sp3 hybridized carbons (C–C and –CH2–CH2–), hydroxylated carbon (C–OH), and carboxylate carbon (O=C–O), respectively. Thus, gadofullerene 2 can be designated as Gd3N@C80(OH)~26(CH2CH2COOM)~16 (M = Na, H). It was reported that the molecular stability of fullerenols largely depends on the quantity of the highly oxygenated carbons, but less on the number of hydroxyl groups (35). In compound 2, there are no highly oxygenated carbons based on the XPS analysis, which may be helpful to stabilize the carbon cage and thus protect the Gd3N clusters inside from leakage (36). Xiao Z., et al. reported the synthesis of [59]fullerenones starting from the fullerene mixed peroxide, C60(OO-t-Bu)6 (37). They suggested a reaction mechanism of peroxide-mediated stepwise cleavage of fullerene skeletal bonds. However, acyl peroxides, RC(O)OO(O)CR (R = aliphatic, aromatic, or another group), readily decompose to release carbon dioxide and form free radicals R upon mild heating (38). Yoshida et al reported a reaction of C60 with diacyl peroxides containing perfluoroalkyl groups to yield C60(RFOH) and C60(RFCO3H) (39). Succinic acid peroxide, 1, decomposes to form a HOOCCH2CH2COO radical (40), which can subsequently lose CO2 to yield a 2-carboxyethyl radical and add on the C=C double bonds of metallofullerenes. This method has been successfully applied to the modification of SWNTs (41).

The IR spectrum of 2 (Figure S3) displays intense bands at 1576 cm-1 and 1402 cm-1 (overlap with O–H bending vibration) for the carboxylate ion asymmetrical and symmetrical stretching vibrations, respectively. The C–O stretching absorptions at about 1120 and 1014 cm-1, an intense broad O–H band at ca. 3169 cm-1, and a very strong O–H bending vibration frequency at 1402 cm-1 indicated the –C–O–H structure of the compound. The weak peaks at 1649 cm-1 and 2893/2826 cm-1 are from C=C and C–H vibrations, respectively. It is noteworthy that the antisymmetric Gd-N stretching vibration can be observed at 689 cm-1, a frequency increase of 32 cm-1 compared to that of pristine Gd3N@C80, which appears at 657 cm-1 (42). The higher vibrational energy in 2 reflects a stronger Gd-N bond relative to pristine Gd3N@C80. The broad absorption at 3618 cm-1 is from bonded water. These IR absorptions are consistent with the results from XPS analysis.

The UV-vis absorption spectra of 2 and Gd3N@C80 (Figure S4) were measured in water and toluene, respectively. The UV-vis spectra reveal that the Gd3N@C80 derivative 2 has lost most of the characteristic absorbance for Gd3N@C80 that was centered at 706 and 676 nm (42, 43), indicating that the removal of p-orbitals from the π system of the cage by introduction of the hydroxyl and ethylenecarboxyl groups changes the electronic structure.

In Vitro MRI Study

I n order to explore the potential of compound 2 as an MRI contrast agent, the proton relaxivities (1), r1 and r2 values (the paramagnetic longitudinal and transverse relaxation rate enhancement of water protons, respectively, referred to 1 mM concentration), were measured at three different magnetic fields, 0.35 T, 2.4 T and 9.4 T. Generally, the relaxivity, ri, can be defined by equation 1:

| (1) |

in which 1/T1 and 1/T2 are the longitudinal and transverse relaxation rates of the solvent. 1/Ti,obsd, 1/Ti,d and 1/Ti,para are the observed relaxation rates in the presence of the paramagnetic species, the values in the absence of the paramagnetic species and the contribution from paramagnetic compound, respectively. [M] is the concentration of the paramagnetic species.

As shown in Table 1 (in unit of mM-1s-1 per mM of gadofullerene molecules), the r1 and r2 of 2 at 2.4 T (close to clinical used magnetic fields) are 50 and 60 times larger than those of commercial Omniscan® (Gd-DTPA BMA, r1/r2 = 4.1/4.7 mM-1s-1 as shown in Table 2) under the same conditions. In contrast, these values decrease greatly in PBS solution, which we ascribe to deaggregation, leading to smaller and faster tumbling complexes and correspondingly lower relaxivities. It can be seen that the r2/r1 ratio of the present compound 2 increases as the magnetic field increases. This observation and the high r2 value strongly suggest that gadofullerene 2 could also be used as a T2-enhancing MRI contrast agent at higher magnetic fields. Toth and coauthors have reported the first relaxometric studies on Gd@C60[C(COOH)2]10 and Gd@C60(OH)x and discovered a maximum in the high-field (10-100 MHz) region of their nuclear magnetic resonance dispersion (NMRD) profiles (36). They suggest that the relaxivity maxima could arise from an increase in the rotational correlation time, τR, of the contrast agent (46, 47). Although a more detailed NMRD profile measurement was not performed in the current study, the maximum at 2.4 T (100 MHz) rather than 0.35 T (15 MHz) and 9.4 T (400 MHz) suggests that the relaxivity maxima may also be due to an increase in the rotational time resulting from an increase in aggregation of gadofullerenes in aqueous solution relative to PBS vide infra.

Table 1.

Relaxivities (in unit of mM-1s-1 per mM of gadofullerene molecules) and r2/r1 ratios of 2 in pure water and PBS solutions, at 0.35 T, 2.4 T and 9.4 T, room temperature.

| 0.35 T (15 MHz) | 2.4 T (100 MHz) | 9.4 T (400 MHz) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r1 | r2 | r2/r1 | r1 | r2 | r2/r1 | r1 | r2 | r2/r1 | |

| Water | 154±7 | 204±22 | 1.3±0.2 | 207±9 | 282±31 | 1.8±0.2 | 76±3 | 231±25 | 3.0±0.4 |

| PBS | 29±1 | 37±4 | 1.3±0.2 | 35±2 | 62±7 | 1.6±0.2 | 18±1 | 72±8 | 4.1±0.5 |

Table 2.

Comparison of relaxivities (in unit of mM-1 s-1 per mM of gadolinium ions).

| Compound | Relaxivity (r1/r2) mM-1s-1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.35 T 15 MHz |

2.4 T 100 MHz |

9.4 T 400 MHz |

|

| 2 | 51/68 | 69/94 | 25/77 |

| Gd@C82(OH)40 (18) | 67/79 (0.47 T) | 81/108 (1.0 T) | 31/131 (4.7 T) |

| Gd@C82O2(OH)16[C(PO3Et2)]10(27) | 37/42 | 39/68 | 20/74 |

| Gd@C82O6(OH)16(NHC2H4COOH)8(22) | 16/-- | -- | -- |

| Gd@C60(OH)x(44) | -- | 83.2/-- (1.5 T) | -- |

| Gd@C60[C(COOH)2]10(44) | 4.6/-- (0.47 T) | 24.0/-- (1.5 T) | -- |

| Sc2GdN@C80Om(OH)n(29) ScGd2N@C80Om(OH)n |

-- | -- | 20.7/-- (14.1 T) 17.6/-- (14.1 T |

| Gd3N@C80Peg5000(OH)x(23) | 34/48 | 48/74 | 11/49 |

| Gd3N@C80Rx(24) R=N(OH)(CH2CH2O)6CH3 |

68/79 (0.47 T) | -- | -- |

| Gd-BOPTA (45) (in human blood plasma) | 10.9/-- (0.2 T) 4.39/5.56(9)* |

7.9/--(1.5 T) | 5.9/-- (3T) |

| MS-325(in human plasma)(14) | 53.5/-- (0.47 T) | -- | -- |

| Gd-DTPA BMA | -- | 4.1/4.7 | -- |

Notes:

is under the condition of 0.47 T, pH = 7.4, 39 °C.

In Table 2, the relaxivities of 2 are compared with other gadofullerenes under different conditions as well as the newly approved Gd-based complex in human serum plasma. It should also be noted that another Gd-based carbonaceous nanomaterial, ultrashort (20-80 nm) gadonanotubes are reported to exhibit very high relaxivities (r1 = 180, 1.5 T) at pH 6.5 and 37 °C (26). The unprecedented relaxivity and corresponding variable-field NMRD’s of the latter material is not readily rationalized using classic Solomon-Bloembergen-Morgan (SBM) theory (46). Wilson and coworkers suggested that gadonanotubes are likely an example of special properties (magnetic/relaxivity) arising from the nanoscalar confinement of Gd3+ ion clusters within their carbon capsule sheaths (26). At clinically used field strengths (1.0~3 T), polyhydroxylated Gd@C82 (18) and Gd@C60(44) exhibit higher relaxivities due to the larger aggregates and fast exchange with water via OH groups. The Gd3N@C80 derivatives are the second member of agents with high relaxivities, but the C80 cage can entrap three gadolinium ions and concentrate them safely, thus providing substantially higher relaxivities (r1/r2 from 69/94 per Gd and 207/282 per cage). The new compound 2 together with reported Gd3N@C80Rx(R=N(OH)(CH2CH2O)6CH3) (24) exhibit higher relaxivity than Gd3N@C80[Peg5000(OH)x] (23). Additionally, compound 2 with carboxylic groups may provide a unique platform for coupling with molecular targeting moieties. Under similar conditions, Gd-BOPTA and MS-325 exhibit great advantages in human plasma relative to the routinely used Gd-DTPA-BMA, but their relaxivities are still significantly lower than those of gadofullerenes.

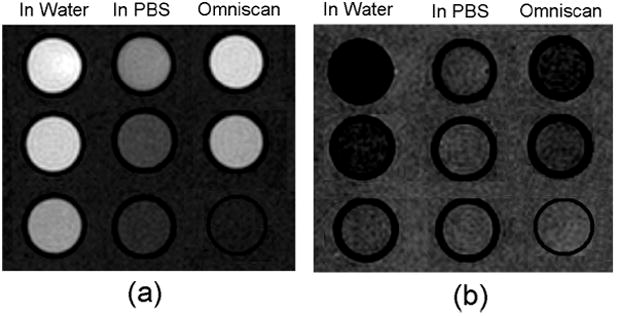

To confirm the large MRI signal enhancement of 2 at lower Gd concentration than that required for the commercial contrast agent Omniscan®, T1- and T2-weighted MR images of Gd3N@C80(OH)~26(CH2CH2COOM)~16 solutions at concentrations of 34, 14 and 7 μM [Gd3N] and Omniscan® at concentrations of 1.0 and 0.5 mmol Gd/L were measured using a spin-echo pulse sequence. A strong MRI signal enhancement was observed for 2 at 14 μM, whereas Omniscan® exhibits similar contrast at a concentration of 0.5 mM, confirming that the MRI signal-enhancing efficiency of gadofullerene 2 is indeed much higher than that of Omniscan® (Figure 1) and gadofullerene 2 is also a good T2-enhancing contrast agent (Figure 1b). These MRI data are in conformity with the high r1 and r2 values reported in Table 1.

Figure 1.

T1-weighted images with TR/TE = 700/13 ms, Number of Acquisitions (NA) = 4 (a); and T2-weighted images TR/TE = 6000/100 ms, NA = 1 (b); of 2 in pure water and PBS with concentrations of 34, 14, 7 μM [Gd3N] from top to bottom, respectively; and Omniscan™ at [Gd] concentrations of 1.0, 0.5 and 0 mM (pure water) from top to bottom. Matrix: 192 × 192; slice thickness = 2 mm.

So far, several types of functionalized MRI contrast agents based on classical metallofullerenes Gd@C2n (2n = 60, 82) and TNT metallofullerene Gd3N@C80 have been reported, such as the polyhydroxylated (16-18, 20, 29) and the carboxylated Gd@C2n (2n = 60, 82) (21, 22), sulphonated (48) and phosphated (27) Gd@C82, the PEGlated hydroxylated Gd3N@C80 (23) and Gd3N@C80Rx(R=N(OH)(CH2CH2O)6CH3) (24). Polyhydroxylated metallofullerenes with high reticuloendothelial system (RES) uptake exhibited much higher relaxivity than the sulfonated and carboxylated systems, which exhibit a favorable non-RES distribution. Although water molecules are not directly coordinated to the encapsulated metal ion, these gadofullerene-based MRI contrast agents exhibit much higher relaxivities than the Gd chelates. The mechanisms ascribed to these high relaxivities include: (a) the presence of three Gd3+ ions within the cage: the charge transfer between the Gd3N cluster and the C80 cage leads to a very stable nanoparticle and the ferromagnetic coupling gives rise to a large magnetic moment, 21 μB (49, 50); (b) a large number of hydroxyl groups attached to the carbon cage which facilitate exchange of protons with surrounding water protons; this exchange, transmits the paramagnetic relaxation to the bulk water; (c) a longer rotational correlation time τR (the order of nanoseconds) as a result of aggregation and (d) the presence of a pool of water molecules that are trapped within the aggregates are relaxed by the gadofullerenes and exchange rapidly with the bulk water molecules (51). This is in contrast with the conventional Gd-DTPA complex which has a single water molecule bound in the first coordination sphere of the metal ion and the entire complex tumbles very rapidly (τR ~ 58 ps) (1).

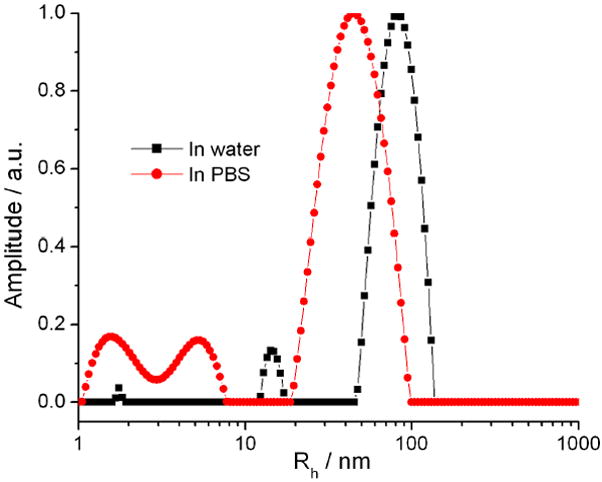

Notably, the hydrodynamic diameter distribution of as-synthesized Gd3N@C80(OH)~26(CH2CH2COOM)~16 in water is unimodal. This is significantly different from the results found for Gd@C60(OH)x and Gd@C60[C(COOH)2]10 (52), but is similar to that of our formerly synthesized Gd@C82O6(OH)16(NHCH2CH2COOH)8 (53). In the PBS medium, the relatively larger aggregate s were reduced in size by the intercalation of phosphate, since the H2PO4- and HPO42- ions can break up intermolecular H-bonding (44); the resulting smaller size aggregate distribution relative to that in pure water leads to faster tumbling entities and correspondingly lower 1H relaxivity. This interpretation is consistent with the multi-modal distributions in PBS (Figure 2), which indicates a dynamic aggregation/deaggregation process. The downward shift of the intensity-weighted size distribution in PBS solution (Figure 2) led to a marked decrease of proton relaxivities (r1/r2 = 35/62 mM-1s-1 at 2.4 T) relative to those in pure water (r1/r2 = 207/282 mM-1s-1), indicating that the aggregation size in this range isn’t large enough to increase the rotational time of entities to the ns range. Recently, Fatouros et al. (23) reported an MRI contrast agent based on a trimetallic nitride templated metallofullerene (TNT EMF), Gd3N@C80, which was PEGylated and hydroxylated. This compound also exhibited extremely high relaxivities due to the advantages described above. However, the small size distribution (less than 10 nm) of Gd3N@C80[Peg5000(OH)x] leads to a lower relaxivity compared to compound 2 (48 mM-1s-1 vs. 69 mM-1s-1 at 2.4 T), which exhibits average hydrodynamic diameter of ca. 78 nm (Figure 2). Notably, Gd3N@C80Rx(R=N(OH)(CH2CH2O)6CH3) was found to have small particle size of 10-15 nm but high relaxivity (68 mM-1s-1 at 0.47 T) (24). These Gd3N@C80-based different derivatives may lead to different tissue-uptake (21) due to the different aggregating behaviors.

Figure 2.

Intensity-weighted (intensity percent) size distribution profiles of 2 in pure water, pH = 7.0 (black line) and PBS, pH = 7.4 (red dash) at 90° scattering angle. Temperature = 25 °C.

Agarose Gel Infusion Experiment

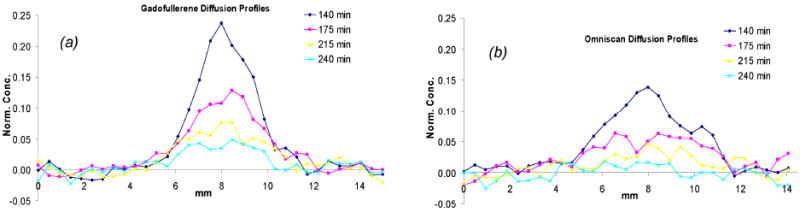

In order to understand the distribution of the new gadofullerene compound 2 upon direct infusion by Convection-Enhanced Delivery (CED) into the extracellular space of the brain, agarose gel (0.6 %) was used as a surrogate for in vivo brain tissues. With the CED method, a bilateral infusion of 0.005 mM gadofullerene 2 and 0.25 mM Ominscan® was administered into the agarose gel phantom. The infusion was applied for 120 min at 0.2 μL/min. To obtain comparable T1-weighted images, the concentration values of the infusates (0.005 mM of gadofullerenes and 0.25 mM of Gd-DTPA-BMA, respectively) were adjusted using our measured r1 values (ratio=207/4.1=50).

Figure 3 displays successive T1 computed maps of Gd3N@C80(OH)~26(CH2CH2COOM)~16 and Omniscan® in the agarose gel. The displayed times are in minutes after the start of infusion. The T1 maps shown demonstrate different diffusion patterns. That is, the gadofullerene 2 bolus is more compact, diffuses more slowly and lingers longer – see the higher residual at 240 min vs the Omniscan®. To investigate the diffusion of the new compound quantitatively, we have converted these T1 maps into concentration maps by means of the equation 1/T1 = 1/T10 + r1[M]. Concentration profiles normalized to the infused concentrations through the two infusates at different time points are shown in Figure 4. The slower diffusion of gadofullerene is consistent with the dependence of the width of the diffusion profile on diffusion coefficient D and time of diffusion t: full-width at half maximum (FWHM) ∝ (D•t)1/2 assuming an approximate Gaussian profile. From the Stokes-Einstein equation and the known particle radii, the diffusion coefficient for the gadofullerene 2 is 40-50 times smaller than Omniscan®; hence, the gadofullerene 2 diffusion time is 40-50 times longer. Our present study further qualified the diffusion time of compound 2 relative to former reported Gd3N@C80[Peg5000(OH)x] (23), which may have a shorter diffusion time due to the small size distribution.

Figure 3.

T1 computed map images of bilaterial infusion into 0.6 % agarose gel of 0.005 mM Gd3N@C80(OH)~26(CH2CH2COOM)~16 (left side of each image) and 0.25 mM Omniscan® (right side of each image). Displayed times are in minutes post beginning of infusion. Infusion was applied for 120 minutes at 0.2 μL/min on both ports. At each time point three contiguous slices are shown with infusion carried out in the middle slice.

Figure 4.

Concentration profiles normalized to the infused concentrations through the gadofullerene infusate (a) and Omniscan infusate (b) at different time points.

In vivo Infusion Experiment

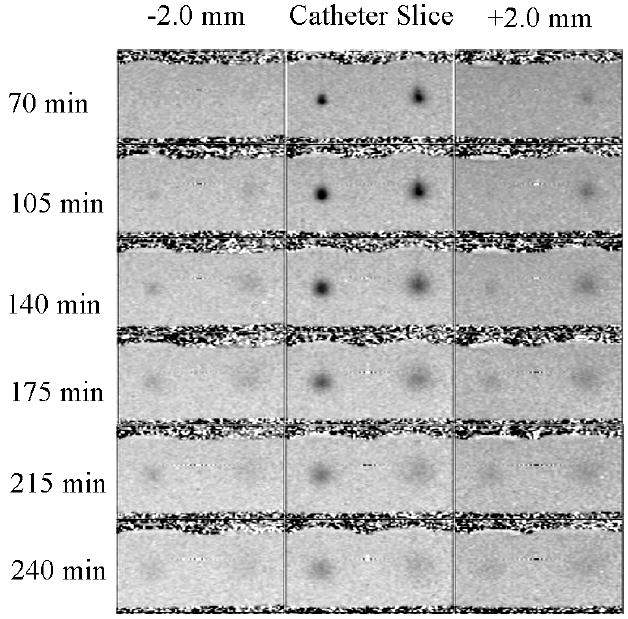

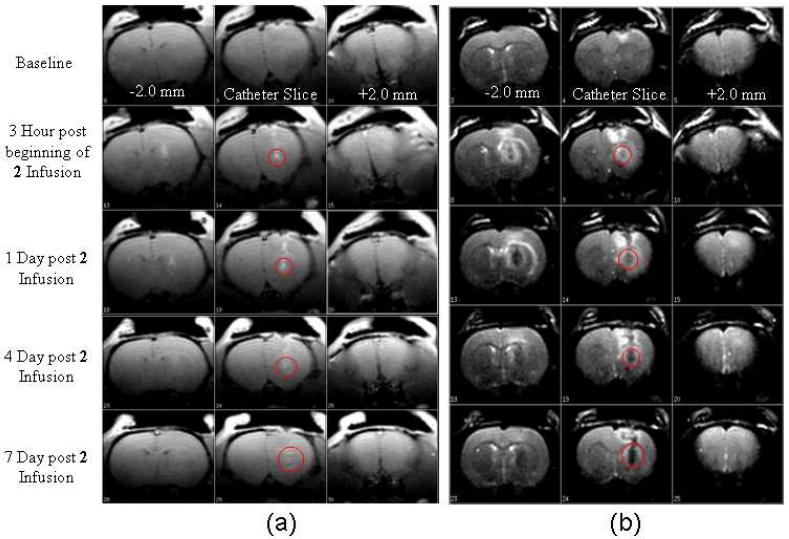

To further document and quantitate the diffusion profile of the infused gadofullerenes in vivo, we have used a Fischer 344 female rat as an animal model of an experimental brain glioma tumor: 5×104 T9 glioblastoma cells were directly deposited into the brain parenchyma through a guide cannula. Before direct infusion of Gd3N@C80(OH)26(CH2CH2COOm)16 (2) into T9 tumor bearing rat brain on day 13 post cell implantation, a baseline image of the anesthetized animal was acquired for comparison. Then direct infusion of 0.0475 mM Gd3N@C80(OH)26(CH2CH2COOm)16 (2) into the brain at the nascent tumor site was applied for 120 minutes at 0.2 μL/min using a slow, low-pressure process. The anesthetized animal was imaged in a 2.4 T/40 cm MR Bruker/Biospec system at days 13, 14, 17 and 20 post cell implantation (or at 3 h, Id, 4d and 7d post 2 infusions). Seven days after the injection, an established tumor was clearly identifiable at the implantation site.

Figure 5 shows T1 weighted images (TR/TE = 700/10) and T2 weighted images (TR/TE = 6000/100). From these successive images, we can see clearly that the new contrast agent provides contrast enhancement (red circles) at very low concentration (0.0475 mM, 24μL). Notice that a larger tumor bolus can be imaged clearly even after 7 days post injection, indicating that a prolong stay of this contrast agent in the tumor can work as long term diagnostic agent.

Figure 5.

T1 weighted images (TR/TE = 700/10) (a) and T2 weighted images (TR/TE = 6000/100) (b) of direct infusion into T9 tumor bearing rat brain of 0.0475 mM Gd3N@C80(OH)26(CH2CH2COOm)16 (2). Infusion was applied for 120 minutes at 0.2 μL/min.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, a new gadofullerene-based MRI contrast was synthesized by a facile method in high yield. This new MRI contrast agent exhibited equivalent contrast enhancement at dosage levels 1/50 of that of the commercial MRI contrast agent, Omniscan®. DLS results displayed particle size shift from 78 in pure water to 44 nm in PBS solutions. Agarose gel infusion experiments revealed different diffusion properties of gadofullerene 2 from clinically used Omniscan®. The functional carboxyl terminal groups, –COOH, may enable the conjugation of biomarkers for future tissue-targeting studies. The in vivo experimental results demonstrate that this new contrast agent can provide high contrast enhancement at very low concentration and work as long term diagnostic agent due to its slow diffusion behavior relative to Omniscan®.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

PPF, HWG and HCD are grateful for support of this work by the National Science Foundation [DMR-0507083] and the National Institutes of Health [1R01-CA119371].

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Experimental details; Graphic illustration of extraction and isolation of Gd3N@C80(OH)x(CH2CH2COOM)y, M = Na or H; C1s XPS spectra of Gd3N@C80(OH)x(CH2CH2COOM)y and Sc3N@C80(OH)x(CH2CH2COOM)y; 13C NMR of Sc3N@C80(OH)~26(CH2CH2COOM)~16 (M = Na or H); FTIR and UV-vis spectra of Gd3N@C80(OH)x(CH2CH2COOM)y. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Caravan P, Ellision JJ, McMurry TJ, Lauffer RB. Gadolinium(III) Chelates as MRI Contrast Agents: Structure, Dynamics, and Applications. Chem Rev. 1999;99:2293–2352. doi: 10.1021/cr980440x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franano FN, Edwards WB, Welch MJ, Brechbiel MW, Gansow OA, Duncan JR. Biodistribution and metabolism of targeted and nontargeted protein-chelated-gadolinium complexes-Evidence for gadolinium dissociation in vitro and in vivo. Magn Reson Imaging. 1995;13:201–214. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(94)00100-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rebizak R, Schaefer M, Dellacherie E. Polymeric conjugates of Gd3+-diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid and dextran. 2. Influence of spacer arm length and conjugate molecular mass on the paramagnetic properties and some biological parameters. Bioconjugate Chem. 1998;9:94–99. doi: 10.1021/bc9701499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gadolinium-Based Contrast Agents for Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): marketed as Magnevist, MultiHance, Omniscan, OptiMARK, ProHance. http://www.fda.gov/medwatch/safety/2007/safety07.htm#Gadolinium.

- 5.Sosnovik DE, Weissleder R. Emerging concepts in molecular MRI. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2007;18:4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson SA, Lee KK, Frank JA. Gadolinium-fullerenol as a paramagnetic contrast agent for cellular imaging. Invest Radiol. 2006;41:332–338. doi: 10.1097/01.rli.0000192420.94038.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sitharaman B, Tran LA, Pham QP, Bolskar RD, Muthupillai R, Flamm SD, Mikos AG, Wilson LJ. Gadofullerenes as nanoscale magnetic labels for cellular MRI. Contrast Media & Molecular Imaging. 2007;2:139–146. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hartman KB, Wilson LJ, Rosenblum MG. Detecting and treating cancer with nanotechnology. Molecular Diagnosis & Therapy. 2008;12:1–14. doi: 10.1007/BF03256264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uggeri F, Aime S, Anelli PL, Botta M, Brocchetta M, Dehaen C, Ermondi G, Grandi M, Paoli P. Novel contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging. Synthesis and characterization of the ligand BOPTA and its Ln(III) complexes (Ln = Gd, La, Lu). X-ray structure of disodium (TPS-9-145337286-C-S)-[4-carboxyl-5,8,11-tri(carboxymethyl)-1-phenyl-2-oxa-5,8,11-triazatridecan-13-oato(5-)]gadolinate(2-) in a mixture with its enantiomer. Inorg Chem. 1995;34:633–642. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cavagna FM, Maggioni F, Castelli PM, Dapra M, Imperatori LG, Lorusso V, Jenkins BG. Gadolinium chelates with weak binding to serum proteins - A new class of high-efficiency, general purpose contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging. Invest Radiol. 1997;32:780–796. doi: 10.1097/00004424-199712000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pintaske J, Martirosian P, Graf H, Erb G, Lodemann KP, Claussen CD, Schick F. Relaxivity of gadopentetate dimeglumine (Magnevist), gadobutrol (Gadovist), and gadobenate dimeglumine (MultiHance) in human blood plasma at 0.2, 1.5, and 3 Tesla. Invest Radiol. 2006;41:213–221. doi: 10.1097/01.rli.0000197668.44926.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giesel FL, von Tengg-Kobligk H, Wilkinson ID, Siegler P, von der Lieth CW, Frank M, Lodemann KP, Essig M. Influence of human serum albumin on longitudinal and transverse relaxation rates (R1 and R2) of magnetic resonance contrast agents. Invest Radiol. 2006;41:222–228. doi: 10.1097/01.rli.0000192421.81037.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parmelee DJ, Walovitch RC, Ouellet HS, Lauffer RB. Preclinical evaluation of the pharmacokinetics, biodistribution, and elimination of MS-325, a blood pool agent for magnetic resonance imaging. Invest Radiol. 1997;32:741–747. doi: 10.1097/00004424-199712000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lauffer RB, Parmelee DJ, Dunham SU, Ouellet HS, Dolan RP, Witte S, McMurry TJ, Walovitch RC. MS-325: Albumin-targeted contrast agent for MR angiography. Radiology. 1998;207:529–538. doi: 10.1148/radiology.207.2.9577506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caravan P, Cloutier NJ, Greenfield MT, McDermid SA, Dunham SU, Bulte JWM, Amedio JC, Looby RJ, Supkowski RM, Horrocks WD, McMurry TJ, Lauffer RB. The interaction of MS-325 with human serum albumin and its effect on proton relaxation rates. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:3152–3162. doi: 10.1021/ja017168k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang SR, Sun DY, Li XY, Pei FK, Liu SY. Synthesis and solvent enhanced relaxation property of water-soluble endohedral metallofullerenols. Fullerene Sci Technol. 1997;5:1635–1643. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson LJ. Medical Application of Fullerenes and Metallofullerenes. The Electrochem Soc Interface. 1999 Winter;:24–28. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mikawa M, Kato H, Okumura M, Narazaki M, Kanazawa Y, Miwa N, Shinohara H. Paramagnetic water-soluble metallofullerenes having the highest relaxivity for MRI contrast agents. Bioconjugate Chem. 2001;12:510–514. doi: 10.1021/bc000136m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okumura M, Mikawa M, Yokawa T, Kanazawa Y, Kato H, Shinohara H. Evaluation of water-soluble metallofullerenes as MRI contrast agents. Academic Radiology. 2002;9:S495–S497. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(03)80274-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kato H, Kanazawa Y, Okumura M, Taninaka A, Yokawa T, Shinohara H. Lanthanoid endohedral metallofullerenols for MRI contrast agents. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:4391–4397. doi: 10.1021/ja027555+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bolskar RD, Benedetto AF, Husebo LO, Price RE, Jackson EF, Wallace S, Wilson LJ, Alford JM. First soluble M@C60 derivatives provide enhanced access to metallofullerenes and permit in vivo evaluation of Gd@C60[C(COOH)2]10 as a MRI contrast agent. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:5471–5478. doi: 10.1021/ja0340984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shu CY, Gan LH, Wang CR, Pei XL, Han HB. Synthesis and characterization of a new water-soluble endohedral metallofullerene for MRI contrast agents. Carbon. 2006;44:496–500. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fatouros PP, Corwin FD, Chen ZJ, Broaddus WC, Tatum JL, Kettenmann B, Ge Z, Gibson HW, Russ JL, Leonard AP, Duchamp JC, Dorn HC. In vitro and in vivo imaging studies of a new endohedral metallofullerene nanoparticle. Radiology. 2006;240:756–764. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2403051341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacFarland DK, Walker KL, Lenk RP, Wilson SR, Kumar K, Kepley CL, Garbow JR. Hydrochalarones: A Novel endohedral metallofullerene platform for enhancing magnetic resonance imaging contrast. J Med Chem. 2008;51:3681–3683. doi: 10.1021/jm800521j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dunsch L, Yang S. Metal nitride cluster fullerenes: Their current state and future prospects. Small. 2007;3:1298–1320. doi: 10.1002/smll.200700036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hartman KB, Laus S, Bolskar RD, Muthupillai R, Helm L, Toth E, Merbach AE, Wilson LJ. Gadonanotubes as ultrasensitive pH-smart probes for magnetic resonance imaging. Nano Lett. 2008;8:415–419. doi: 10.1021/nl0720408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shu CY, Wang CR, Zhang JF, Gibson HW, Dorn HC, Corwin FD, Fatouros PP, Dennis TJS. Organophosphonate functionalized Gd@C82 as a magnetic resonance imaging contrast agent. Chem Mat. 2008;20:2106–2109. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shu CY, Ma XY, Zhang JF, Corwin FD, Sim JH, Zhang EY, Dorn HC, Gibson HW, Fatouros PP, Wang CR, Fang XH. Conjugation of a water-soluble gadolinium endohedral fulleride with an antibody as a magnetic resonance imaging contrast agent. Bioconjugate Chem. 2008;19:651–655. doi: 10.1021/bc7002742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang EY, Shu CY, Feng L, Wang CR. Preparation and characterization of two new water-soluble endohedral metallofullerenes as magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111:14223–14226. doi: 10.1021/jp075529y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen CY, Xing GM, Wang JX, Zhao YL, Li B, Tang J, Jia G, Wang TC, Sun J, Xing L, Yuan H, Gao YX, Meng H, Chen Z, Zhao F, Chai ZF, Fang XH. Multi hydroxylated [Gd@C82(OH)22]n nanoparticles: Antineoplastic activity of high efficiency and low toxicity. Nano Lett. 2005;5:2050–2057. doi: 10.1021/nl051624b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang JX, Chen CY, Li B, Yu HW, Zhao YL, Sun J, Li YF, Xing GM, Yuan H, Tang J, Chen Z, Meng H, Gao YX, Ye C, Chai ZF, Zhu CF, Ma BC, Fang XH, Wan LJ. Antioxidative function and biodistribution of [Gd@C82(OH)22]n nanoparticles in tumor-bearing mice. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;71:872–881. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stevenson S, Rice G, Glass T, Harich K, Cromer F, Jordan MR, Craft J, Hadju E, Bible R, Olmstead MM, Maitra K, Fisher AJ, Balch AL, Dorn HC. Small-bandgap endohedral metallofullerenes in high yield and purity. Nature. 1999;401:55–57. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ge ZX, Duchamp JC, Cai T, Gibson HW, Dorn HC. Purification of endohedral trimetallic nitride fullerenes in a single, facile step. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:16292–16298. doi: 10.1021/ja055089t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clover AM, Houghton AC. Action of hydrogen peroxide on anhydrides and the formation of organic acid, peroxides, and peracids. Am Chem J. 1904;32:43–68. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xing GM, Zhang J, Zhao YL, Tang J, Zhang B, Gao XF, Yuan H, Qu L, Cao WB, Chai ZF, Ibrahim K, Su R. Influences of structural properties on stability of fullerenols. J Phys Chem B. 2004;108:11473–11479. doi: 10.1021/jp0487962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Toth E, Bolskar RD, Borel A, Gonzalez G, Helm L, Merbach AE, Sitharaman B, Wilson LJ. Water-soluble gadofullerenes: Toward high-relaxivity, pH-responsive MRI contrast agents. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:799–805. doi: 10.1021/ja044688h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xiao Z, Yao JY, Yang DZ, Wang FD, Huang SH, Gan LB, Jia ZS, Jiang ZP, Yang XB, Zheng B, Yuan G, Zhang SW, Wang ZM. Synthesis of [59]fullerenones through peroxide-mediated stepwise cleavage of fullerene skeleton bonds and x-ray structures of their water-encapsulated open-cage complexes. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:16149–16162. doi: 10.1021/ja0763798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swern D, editor. Organic Peroxides. Wiley-Interscience; New York, London, Sydney, Toronto: 1971. p. 799. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yoshida M, Morinaga Y, Iyoda M, Kikuchi K, Ikemoto I, Achiba Y. Reaction of C60 with diacyl peroxides containing perfluoroalkyl groups. The first example of electron transfer reaction via C60+ in solution. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:7629–7632. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fieser LF, Turner RB. Naphthoquinone Acids and Ketols. J Am Chem Soc. 1947;69:2338–2341. doi: 10.1021/ja01202a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peng HQ, Alemany LB, Margrave JL, Khabashesku VN. Sidewall carboxylic acid functionalization of single-walled carbon nanotubes. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:15174–15182. doi: 10.1021/ja037746s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krause M, Dunsch L. Gadolinium nitride Gd3N in carbon cages: The influence of cluster size and bond strength. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:1557–1560. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang SF, Kalbac M, Popov A, Dunsch L. Gadolinium-based mixed metal nitride clusterfullerenes GdxSc3-xN@C80 (x=1, 2) ChemPhysChem. 2006;7:1990–1995. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200600323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laus S, Sitharaman B, Toth V, Bolskar RD, Helm L, Asokan S, Wong MS, Wilson LJ, Merbach AE. Destroying gadofullerene aggregates by salt addition in aqueous solution of Gd@C60(OH)x and Gd@C60[C(COOH)2]10. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:9368–9369. doi: 10.1021/ja052388+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schneider G, Altmeyer K, Kirchin MA, Seidel R, Grazioli L, Morana G, Saini S. Evaluation of a novel time-efficient protocol for gadobenate dimeglumine (Gd-BOPTA)- enhanced liver magnetic resonance imaging. Invest Radiol. 2007;42:105–115. doi: 10.1097/01.rli.0000251539.05400.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Toth E, Merbach AE. The Chemistry of Contrast Agents in Medical Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Wiley; Chichester: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sharp RR. Paramagnetic NMR. Nucl Magn Reson. 2003:473–519. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lu X, Xu JX, Shi ZJ, Sun BY, Gu ZN, Liu HD, Han HB. Studies on the relaxivities of novel MRI contrast agents two water-soluble derivatives of Gd@C82. Chem J Chin Univ -Chin. 2004;25:697–700. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qian MC, Khanna SN. An ab initio investigation on the endohedral metallofullerene Gd3N@C80. J Appl Phys. 2007;101:09E105-1–09E105-3. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Qian MC, Ong SV, Khanna SN, Knickelbein MB. Magnetic endohedral metallofullerenes with floppy interiors. Phys Rev B. 2007;75(104424):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Laus S, Sitharaman B, Toth E, Bolskar RD, Helm L, Wilson LJ, Merbach AE. Understanding paramagnetic relaxation phenomena for water-soluble gadofullerenes. J Phys Chem C. 2007;111:5633–5639. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sitharaman B, Bolskar RD, Rusakova I, Wilson LJ. Gd@C60[C(COOH)2]10 and Gd@C60(OH)x: Nanoscale aggregation studies of two metallofullerene MRI contrast agents in aqueous solution. Nano Lett. 2004;4:2373–2378. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shu CY, Zhang EY, Xiang JF, Zhu CF, Wang CR, Pei XL, Han HB. Aggregation studies of the water-soluble gadofullerene magnetic resonance imaging contrast agent: [Gd@C82O6(OH)16(NHCH2CH2COOH)8]x. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:15597–15601. doi: 10.1021/jp0615609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.