Abstract

Objective

Activated endothelium and increased monocyte:endothelial interactions in the vessel wall are key early events in atherogenesis. ATP binding cassette (ABC) transporters play important roles in regulating sterol homeostasis in many cell types. Endothelial cells have a high capacity to efflux sterols and express the ABC transporter, ABCG1. Here, we define the role of ABCG1 in the regulation of lipid homeostasis and inflammation in aortic endothelial cells (EC).

Methods and Results

Using EC isolated from ABCG1-deficient mice (ABCG1 KO), we observed reduced cholesterol efflux to HDL compared to C57BL/6 (B6) EC. However, total cholesteryl ester levels were not changed in ABCG1 KO EC. Secretion of KC, MCP-1, and IL6 by ABCG1 KO EC was significantly increased, and surface expression of ICAM-1 and E-selectin was increased several-fold on ABCG1 KO EC. Concomitant with these findings, we observed a 4-fold increase in monocyte adhesion to both the intact aortic endothelium of ABCG1 KO mice ex vivo as well as to isolated aortic EC from these mice in vitro. In a gain-of-function study in vitro, restoration of ABCG1 expression in ABCG1 KO EC reduced monocyte:endothelial interactions. Utilizing pharmacological inhibitors for STAT3 and the IL6 receptor (IL6R), we found that blockade of STAT3 and IL6R signaling in ABCG1 KO EC completely abrogated monocyte adhesion to ABCG1 KO endothelium.

Conclusion

ABCG1 deficiency in aortic endothelial cells activates endothelial IL6-IL6R-STAT3 signaling, thereby increasing monocyte:endothelial interactions and vascular inflammation.

Keywords: endothelial, IL6, IL6 receptor, monocyte adhesion, ABC transporters

Introduction

A key early event in atherosclerosis is the increased interaction of monocytes with endothelial cells in the vessel wall 1. In early atherogenesis, endothelial cells in the artery wall become activated, in many cases by oxidized lipids. Activated endothelial cells secrete pro-inflammatory chemokines that recruit monocytes to the activated endothelium. Interaction of monocytes with adhesion molecules and integrins on the endothelial surface causes the monocytes to tether and firmly adhere to the endothelium, where they can subsequently transmigrate into the subendothelial space2-4.

ABCG1 is an ATP-binding cassette transporter that has been well-studied in macrophages. ABCG1 has been shown to promote cholesterol efflux to HDL particles in reverse cholesterol transport 5,6. Deficiency of ABCG1 in macrophages leads to reduced cholesterol efflux and increased macrophage cholesteryl ester accumulation 5,6. Rader and colleagues have elegantly shown that ABCG1 promotes reverse cholesterol transport in mice in vivo 7. We previously reported that ABCG1 expression and function is significantly reduced in patients with Type 2 diabetes, potentially contributing to the formation of lipid-laden macrophages and accelerated atherosclerosis in these patients 8. Aortic endothelial cells also express the ABC transporters ABCA1 and ABCG1 and efflux cholesterol to HDL 9. EC have a dramatic ability to efflux cholesterol, most likely to aid in homeostasis to prevent endothelial activation in the vessel wall 9,10. There is tight regulation of sterol content and ABC transporter expression in EC. Indeed, Shyy and colleagues found that SREBP activation by sterols causes downregulation of ABCA1 in EC 11. Moreover, Genest and colleagues found that ABCG1, and not ABCA1, was induced by cholesterol loading of EC 9. There also appears to be a critical link between lipid homeostasis and inflammatory responses in vascular EC. Berliner and colleagues have shown that oxidized phospholipids activate SREBP, which in turn, induces endothelial IL-8 production 12. Moreover, several studies have shown that incubation of endothelial cells with HDL reduces the endothelial inflammatory response 13-18. This may be in part due to the ABCG1-mediated delivery of cholesterol from endothelial cells to HDL as well as to the presence on HDL particles of the paraoxonase enzyme and the anti-inflammatory lipid sphingosine-1-phosphate.

In the current study, we examined the role of ABCG1 in aortic endothelial function. We found that ABCG1 expression is important for regulation of the inflammatory response of the aortic endothelium, and for regulation of monocyte:endothelial interactions in the vessel wall.

Methods

Detailed methods and reagents used can be found in the online data supplement, available at http://atvb.ahajournals.org. C57BL/6 (B6) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. ABCG1 KO mice19 were purchased from Deltagen, and have been backcrossed for 13 generations onto the C57BL/6J background. Mice were housed in barrier facilities and maintained on rodent chow (4% fat) throughout the study. All animal studies were performed following approved guidelines of the University of Virginia Animal Care and Use Committee. Aged-matched B6 and ABCG1 KO mice between 10-12 weeks of age were used for all experiments. Aortas from B6 and ABCG1 KO mice were removed, opened longitudinally, pinned on agar, and used in an ex vivo monocyte adhesion as previously described.20 Alternatively, primary aortic endothelial cells (EC) from B6 and ABCG1 KO mice were harvested from mouse aorta under sterile conditions as outlined previously 21. Primary aortic EC at passage 2 were used for flow cytometry to measure adhesion molecule expression, and used in a Glycotech parallel plate flow chamber for monocyte adhesion studies. Cytosolic and nuclear extracts were harvested from primary EC using the NE-PER kit (Pierce) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and immunoblotting for signaling molecules was performed as previously described22.

Results

ABCG1-deficient aortic EC have increased lipid content

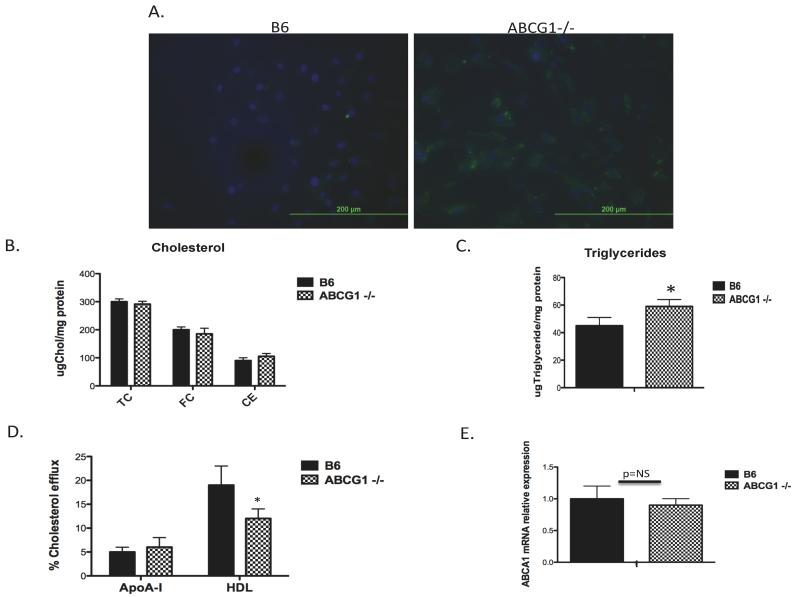

Endothelial cells (EC) possess ABC transporters, including ABCG1 and ABCA1, to assist with cholesterol homeostasis in the vessel wall 9,23. ABCG1 is the primary protein involved in the removal of cholesterol from endothelial cells 9,14. We first examined the impact of ABCG1 deficiency on the lipid content of endothelial cells. Aortic endothelial cells were isolated from control C57BL/6J (B6) and ABCG1 KO mice fed rodent chow. Lipid accumulation in chow-fed control and ABCG1 KO EC was quantified using immunofluorescence and gas chromatography. We observed lipid accumulation occurring primarily within punctate intracellular structures (lipid is stained green; Figure 1A) in aortic ABCG1-deficient EC at passage 1 compared to B6 EC. We analyzed endothelial free cholesterol (FC) and cholesteryl ester (CE) content using gas chromatography. Surprisingly, there were no statistically significant changes in total cellular CE or FC content (Figure 1B) in ABCG1 KO mice. We also measured triglyceride content in EC. We found low levels of triglycerides present in both B6 and ABCG1 KO EC. We observed a modest increase in TG content that averaged approximately 15% between B6 and ABCG1 KO EC (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. Neutral lipid content and cholesterol efflux in ABCG1-deficient aortic EC.

Panel A. Fluorescent Microscopy. Primary aortic endothelial cells isolated from C57BL/6 (B6) and ABCG1-deficient (ABCG1 KO) mice at passage 1 were stained with Nile Red to detect neutral lipid and DAPI to detect nuclei as described in Materials and Methods. Images depict overlaid DAPI and FITC channels taken at 400x while visualizing Nile Red using a fluorescent microscope. Within the cells, nuclei are stained blue with DAPI and the lipid droplets are stained green with Nile Red. Panel B. Quantification of endothelial cholesterol content. Cellular free cholesterol (FC), cholesteryl ester (CE), and total cholesterol content (TC) in MAEC at passage 2 were quantified as described in Materials and Methods using gas chromatography. MAEC were examined under basal conditions (B6, G1). N=cells from 6 mice measured in duplicate. Panel C. Quantification of endothelial triglyceride content. Triglyceride levels from MAEC at passage 2 were analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. N=cells from 4 mice per group. *p<0.01 by Student t-test. Panel D. Cholesterol efflux. B6 and ABCG1 KO EC were incubated with 3H-cholesterol for 24h followed by incubation with either HDL or lipid-free apolipoprotein AI (apoAI) acceptors for 4h. Efflux was measured as described in Materials and Methods. N=cells from 8 mice per group. *Significantly lower than B6, p<0.001. Panel E. ABCA1 mRNA expression. Expression of ABCA1 mRNA in MAEC at passage 2 was measured using real-time quantitative PCR. N=cells from 6 mice per group.

Studies have previously shown that lipid loading of EC rapidly stimulates cholesterol efflux pathways to maintain lipid homeostasis 9,23. Based upon the known role of ABCG1 in promoting cholesterol efflux from macrophages5,6, we predicted that ABCG1 KO EC would show reduced cholesterol efflux. This is indeed the case, as shown in Figure 1D. We observed no change in cholesterol efflux to lipid-free apoAI, a process mediated by ABCA1 6,24. Concomitant with these findings, we observed no changes in ABCA1 mRNA expression in ABCG1 KO EC (Figure 1E). Taken together, these studies indicate that absence of ABCG1 in endothelium results in a significant reduction in cholesterol efflux to HDL, and although the endothelial total cholesterol content is not changed, there appears to be a change in the intracellular distribution of neutral lipid in the ABCG1 KO EC.

Increased monocyte:endothelial interactions in aorta of ABCG1 KO mice

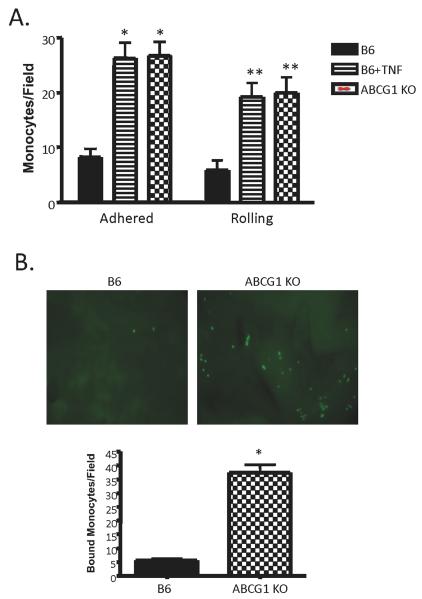

We postulated that the increase in lipid content in the ABCG1 KO endothelial cells would initiate an inflammatory response and cause increased monocyte:endothelial interactions. To test this, we utilized both in vitro and ex vivo approaches. First, using a parallel plate flow chamber system, we quantified the number of rolling and adherent monocytes to aortic endothelial cells isolated from either B6 or ABCG1 KO mice fed chow. Under normal conditions, quiescent aortic endothelium binds very few monocytes, as we have shown previously 20,25,26. However, activated endothelium is capable of binding significant numbers of monocytes, which is indicative of a classical inflammatory response. As shown in Figure 2A, ABCG1 KO endothelium had approximately 4-fold increases in the numbers of both rolling and adherent monocytes. We utilized B6 MAEC incubated with TNFα as a positive control for endothelial activation (Figure 2A). Surprisingly, ABCG1 KO EC were as activated as the TNFα-treated control EC, at least within the limits of this in vitro assay. To examine monocyte:endothelial interactions in a more physiologically relevant setting, aortas were harvested from B6 and ABCG1 KO mice fed chow and immediately used in an ex vivo monocyte adhesion assay. Monocyte adhesion was increased by 4-fold to ABCG1-deficient aortae compared to control B6 aortae (Figure 2B). The representative images in Figure 2B illustrate the number of monocytes that have adhered to the intact endothelium of the aorta of each group. The graph in Figure 2B displays the mean±SE for monocyte adhesion to intact aortae from 8 mice per group.

Figure 2. Aortas from ABCG1 KO mice show increased monocyte rolling and adhesion.

Panel A. Studies in vitro. In a flow chamber assay, fluorescently-labeled WEHI78/24 were allowed to flow over a confluent monolayer of primary murine aortic endothelial cells at 0.75 dynes/cm2. Rolling and firmly adherent monocytes were counted over a 5 minute period. Data represent the mean ±SE of 4 experiments performed in duplicate. As a positive control for rolling and adhesion, B6 EC were incubated with 10U/ml TNFα for 2h (B6+TNF) prior to performing the assay. *Significantly higher adhesion than B6 control, p<0.002; **significantly higher rolling than B6 control, p<0.005 by ANOVA. Panel B. Studies in whole aorta. Aortae were harvested from B6 and ABCG1 KO mice fed rodent chow and immediately used in an ex vivo monocyte adhesion assay. [TOP] Representative images of fluorescently-labeled monocytes adhering to intact endothelium of mouse aorta; [BOTTOM] Graph of mean±SE of monocyte adhesion to intact aorta of 8 mice per group. *Significantly higher than B6 control, p<0.0001 by ANOVA.

ABCG1-deficient endothelium is activated to recruit and bind monocytes

Next, we examined endothelial surface adhesion molecule expression and chemokine production in ABCG1 KO mice. Using flow cytometry, we found increased surface expression of E-selectin and ICAM-1 on ABCG1 KO EC, two adhesion molecules important for regulating monocyte rolling and firm adhesion to endothelium. E-selectin expression was increased from covering approximately 4% of the EC surface in control cells to 21% of the EC surface in ABCG1 KO EC (p<0.001, n=8 mice per group), whereas ICAM-1 expression on the cell surface was increased from 65% in control EC to 76% in ABCG1 KO EC, p<0.02 (n=8 mice per group). ICAM-1 is constitutively and highly expressed on endothelium, thus accounting for the higher percentages of surface expression compared to other adhesion molecules in control cells. We observed no changes in VCAM-1 surface expression between control and ABCG1 KO mice (data not shown).

We also measured chemokine production by aortic endothelial cells. ABCG1 KO aortic EC had significant elevations in secretion of KC (the mouse ortholog of IL-8), IL6 (p<0.001) and MCP-1 (p<0.01) (Supplemental Figure 1). Each of these chemokines is involved in monocyte recruitment in the vessel wall. Taken together, these results indicate that the aortic endothelium of ABCG1 KO mice is activated to interact more readily with monocytes, a key initial event in atherogenesis.

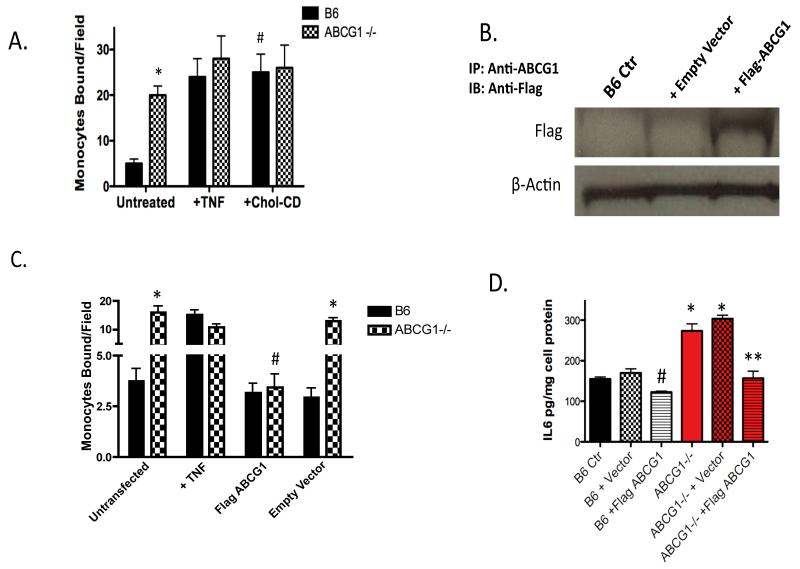

Cholesterol, ABCG1 expression, and monocyte:endothelial interactions

To focus on modulation of lipid content via ABCG1 deficiency as a possible cause of the endothelial activation observed in ABCG1-deficient EC, we performed a series of flow chamber monocyte adhesion assays in which we either modulated the level of cellular cholesterol or modulated ABCG1 expression in an ‘add-back’, or gain-of-function study. First, we loaded B6 control EC with soluble cholesterol using cholesterol-loaded cyclodextrin (Chol-CD). This method is commonly used to load cells with cholesterol, and the cholesterol is rapidly distributed into cellular pools 27,28. Incubation of B6 control EC with Chol-CD for 4h stimulated monocyte adhesion to levels observed for ABCG1-/- EC, indicating that sterol loading of EC increases monocyte:endothelial interactions (Figure 3A). Interestingly, addition of Chol-CD to ABCG1 KO EC did not further stimulate monocyte adhesion (Figure 3A). These data suggest that cholesterol loading of EC can contribute significantly to endothelial activation and monocyte:endothelial interactions.

Figure 3. ABCG1 expression and cholesterol loading impact monocyte:endothelial interactions.

Panel A. Cholesterol loading of EC. MAEC from B6 and ABCG1 KO mice at passage 2 were used at baseline (Untreated), treated with 10U/ml TNF for 4h (+TNF) or incubated with 20μg/ml Cholesterol-cyclodextrin (+Chol-CD) for 4h prior to performing a monocyte adhesion assay in a parallel plate flow chamber. *Significantly higher than B6 Untreated, p<0.0001; #significantly higher than B6 Untreated sample, p<0.0001 by ANOVA. N=cells from 5 mice assayed in quadruplicate. Panel B. Immunoprecipitation of FLAG-ABCG1. B6 MAEC were transfected with either pcDNA (+ Empty Vector) or a flag-tagged murine ABCG1 construct (+Flag-ABCG1). Cells were immunoprecipitated with antibody to murine ABCG1 and an immunoblot to detect the Flag epitope was performed. Lanes were analyzed for β-actin as a control for gel loading. Image is representative of 3 experiments; note expression of Flag-ABCG1 in +Flag-ABCG1 transfected samples. Panel C. Monocyte adhesion assay. B6 MAEC were transfected with either pcDNA (Empty Vector) or flag-tagged murine ABCG1 (Flag ABCG1). At 24h post-transfection, EC were used in a parallel plate flow chamber assay. Cells were incubated with 10 U/ml TNF (+TNF) as a positive control. *Significantly higher than B6, p<0.0001; #Significantly lower than untransfected ABCG1 MAEC, p<0.005 by ANOVA. Panel D. IL-6 production. B6 MAEC were transfected with either pcDNA (+Vector) or flag-tagged murine ABCG1 (+Flag ABCG1). At 24h post-transfection, supernatants were collected for measurement of endothelial IL-6 secretion by ELISA. *Significantly higher than B6, p<0.001; #significantly lower than B6 Ctr, p<0.01; **significantly lower than ABCG1 KO + vector, p<0.004 by ANOVA.

Rather than depleting cellular cholesterol from EC using free cyclodextrin, which can rapidly deplete EC of cellular cholesterol resulting in induction of SREBP and LDLR for cholesterol synthesis12, we chose to directly assess the role of ABCG1 in regulating monocyte adhesion through a gain-of-function experiment. In this study, we transfected B6 control and ABCG1 KO EC with either a pcDNA control vector or a vector expressing flag-tagged murine ABCG1. We were successfully able to express flag-tagged murine ABCG1 in EC (Figure 3B). As shown in Figure 3C, restoration of ABCG1 expression in ABCG1 KO EC resulted in a >90% reduction in monocyte adhesion. Addition of ABCG1 to control B6 EC caused a small reduction in monocyte adhesion (Figure 3C), but this did not reach statistical significance, most likely due to the limits of detection of our assay. To confirm that ABCG1 expression in EC modulated IL6 secretion, we measured IL6 production in EC that had been transfected with either a pcDNA control vector or a vector expressing flag-tagged murine ABCG1. ABCG1 KO EC that were used at baseline or transfected with an empty pcDNA vector showed significant release of IL6 (Figure 3D), whereas transfection of ABCG1 into ABCG1 KO EC significantly reduced IL6 production (Figure 3D). Taken together, these data indicate that ABCG1 expression in EC regulates endothelial activation and modulates IL6 production.

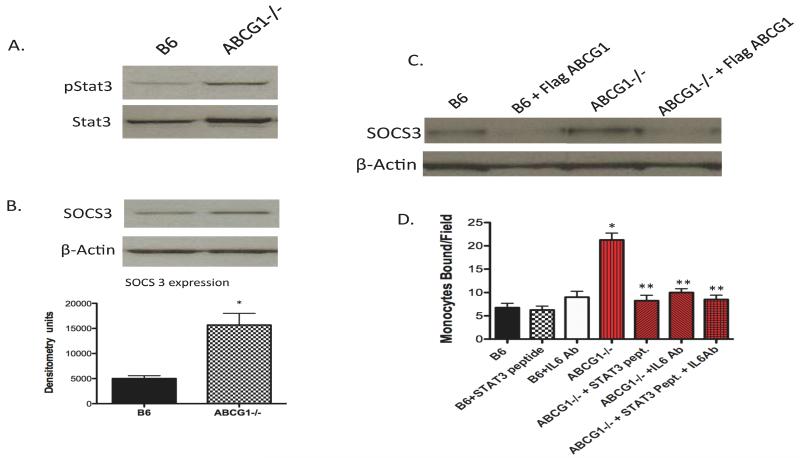

IL6 receptor signaling pathway mediates endothelial activation in the absence of ABCG1

We first examined NFκB signaling due to the increased production of KC and MCP-1 by ABCG1 KO EC. We observed no differences in NFκB activation between B6 and ABCG1 KO EC either at baseline or after TNF stimulation (supplemental Figure 2). We next examined STAT3 signaling through the IL6 receptor (IL6R) pathway since we observed a large increase in endothelial IL6 production. As shown in Figure 4A, ABCG1 KO EC have a significant increase in STAT3 phosphorylation, suggesting that the STAT3 signaling pathway is activated in ABCG1 KO EC. Total STAT3 protein was also increased in ABCG1 KO EC (see β-actin lane in Figure 4B for gel loading). SOCS3, a downstream target of IL6R-STAT3 signaling was induced approximately 2-fold (Figure 4B), further confirming STAT3 activation in ABCG1 KO EC. ABCG1 addition to ABCG1 KO EC in a gain-of-function experiment diminished SOCS3 expression (Figure 4C). Using a well-characterized STAT3 inhibitory peptide, we found that inhibition of STAT3 signaling blocked monocyte adhesion to ABCG1 KO endothelial cells (Figure 4D). In fact, monocyte:endothelial interactions were completely reduced to levels of control EC by the STAT3 inhibitory peptide. These data suggest that a STAT3 signaling pathway is responsible for much of the endothelial activation observed in ABCG1 KO mice.

Figure 4. Activation of the IL6-IL6R-STAT3 signaling pathway in ABCG1 KO aortic EC.

Panels A and B. Immunoblotting. Cytosolic lysates from B6 and ABCG1 KO aortic EC were isolated and analyzed by SDS-PAGE for SOCS3, phospho-STAT3, and STAT3. β-actin was run as a control for gel loading. Representative blots are shown. Graph shows densitometry plot for SOCS3 expression from 4 mice per group. Panel C. Regulation of SOCS3 expression in EC by ABCG1. B6 and ABCG1 KO MAEC were transfected with a flag-tagged murine ABCG1 construct (+Flag ABCG1). At 24h post-transfection, cell lysates were harvested for detection of SOCS3 protein by immunoblotting. Lanes in gel represent a pool of EC from 3 mice per group. Panel D. IL6R neutralization blocks monocyte adhesion. ABCG1 KO EC were incubated with 0.5 μg/mL of the IL6 neutralization antibody (+IL6 Ab) for 10 minutes prior to performing a monocyte adhesion assay. In some cases, EC were pre-incubated with 100μM Stat3 inhibitor peptide (+Stat3 pept.) for 45mins. Data represent the mean + SE of 3 experiments performed in duplicate. *Significantly higher than B6 control, p<0.005; **significantly lower than ABCG1 KO EC, p<0.001 by ANOVA.

To determine whether STAT3 signaling through the endothelial IL6-IL6R axis is the pathway responsible for the endothelial activation observed in the ABCG1 KO mice, we used an IL6 neutralizing antibody to interrupt IL6R signaling in MAEC. Blocking IL6R signaling using the IL6R blocking antibody completely reduced monocyte adhesion to ABCG1 KO EC (Figure 4D). Moreover, addition of both the STAT3 inhibitory peptide and the IL6 neutralizing antibody together to ABCG1 KO EC caused no further reduction in monocyte adhesion to endothelium (Figure 4D), strongly suggesting that the IL6-IL6R-STAT3 axis is primarily responsible for the observed endothelial activation that occurs in ABCG1 KO mice.

HDL binding to ABCG1 KO endothelium

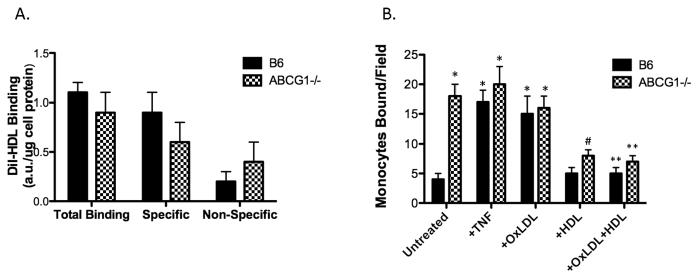

A recent report by von Eckardstein indicated that bovine endothelial cells transfected with siRNA to ABCG1 showed 30% less binding of HDL 29. To test this concept using ABCG1 KO EC, we measured HDL binding to the EC surface by flow cytometry using DiI-labeled HDL. We observed approximately a 10% reduction in specific HDL binding to the surface of ABCG1 KO EC (Figure 5A); however, this value did not reach statistical significance (n= 6 mice per group). Moreover, total HDL binding to both B6 and ABCG1 KO EC was similar (Figure 5A). Furthermore, addition of HDL to ABCG1 KO EC reduced monocyte:endothelial interactions in a flow chamber assay in a manner similar to B6 endothelium (Figure 5B). These data support findings from other cell-types that ABCG1 expression does not alter HDL association with the cell surface, and they suggest that the anti-inflammatory function of HDL in this setting is most likely independent of ABCG1.

Figure 5. Inflammatory state of ABCG1-deficient EC is independent of HDL binding.

Panel A. HDL binding to EC. EC from 6 mice per group were incubated with Di-I-HDL at 4C and total and specific binding of HDL to EC was assessed as described in Materials and Methods. No significant differences were observed in either total, specific, or non-specific HDL binding. Panel B. HDL reduces monocyte:endothelial interactions in B6 and ABCG1 KO EC. MAEC from B6 and ABCG1 KO at passage 2 were incubated for 4h with either 10U/ml TNF (+TNF) or 50μg/ml OxLDL (+OxLDL) in the absence or presence of HDL (+HDL). Monocyte adhesion was measured using a parallel plate flow chamber. *Significantly higher than B6 Untreated, p<0.0001; #significantly lower than ABCG1 Untreated, p<0.001; **significantly lower than +OxLDL, p<0.001 by ANOVA.

Discussion

A key early step in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis is endothelial dysfunction, which is characterized by enhanced expression of leukocyte adhesion molecules, increased permeability of the endothelial monolayer, and increased monocyte:endothelial interactions. Macrophages in atherosclerotic lesions can accumulate significant amounts of cholesterol leading to foam cell formation; however, vascular wall endothelial cells tightly regulate their sterol content despite expressing receptors for oxidized lipoproteins such as CD36 and LOX-110. Endothelial cells have a high capacity to efflux sterols, and the ABC transporters ABCA1 and ABCG1 are expressed in these cells23. ABCG1 mRNA is greatly induced in human EC by cholesterol, and HDL but not apoA-I promotes cholesterol efflux from endothelial cells9,30 indicating a prominent role for ABCG1 in regulating sterol homeostasis in EC. In the current study, we found that aortic EC deficient in ABCG1 have lipid accumulation occurring primarily within punctate intracellular structures (Figure 1). Moreover, ABCG1 KO EC have reduced capacity to efflux cholesterol to HDL, although cholesterol efflux to lipid-free apoAI remains intact (Figure 1). These data suggest that ABCG1 is most likely the primary mediator of cholesterol efflux in endothelium. Indeed, Terasaka and colleagues have also reported that ABCG1 is a primary regulator of cholesterol efflux in human aortic EC 14.

In the current study, we found that aortic EC from ABCG1 KO mice have increased production of chemokines, increased surface expression of the adhesion molecules ICAM-1 and E-selectin that promote monocyte adhesion, and increased monocyte:endothelial interactions. Endothelial cells under basal conditions are not activated, and bind very few monocytes. All of our experiments were performed using primary aortic EC from ABCG1 KO mice at low passage, and we did not stimulate these EC with any lipid to induce activation. Thus, all EC and aortae were studied under their basal conditions. We conclude from our studies that ABCG1 deficiency in EC causes endothelial activation, which in turn, promotes monocyte:endothelial interactions. Moreover, our data strongly suggest that reductions in ABCG1 expression in endothelium promote a pro-inflammatory endothelial phenotype.

Interestingly, the pro-inflammatory phenotype of ABCG1-deficient EC does not appear to be mediated by NFκB (supplemental Figure 2). NFκB induces rapid expression of multiple genes involved in inflammatory responses, including pro-inflammatory chemokines and adhesion molecules. This lack of NFκB activation in ABCG1 KO EC was confirmed by the fact that we observed no change in VCAM-1 expression, which is a key molecule induced by NFκB in endothelium. Similarly, Berliner and colleagues have demonstrated that OxPAPC, a component of minimally modified LDL, does not activate NFκB31.

Based on our finding that STAT3 signaling was a major regulator of monocyte adhesion in ABCG1 KO EC (Figure 4), we focused our attention primarily on the cytokine IL6. IL6 is a cytokine that is involved in mediating monocyte adhesion 32. We found significant production of IL6 by ABCG1-deficient EC (Supplemental Figure 1). Although IL6 is released from monocyte/macrophages, smooth muscle, and endothelium, we anticipate that the release of IL6 from activated endothelium in ABCG1 KO mice in vivo acts to amplify the inflammatory cascade by binding to endothelial IL6 receptors. Binding of IL6 to the IL6 receptor on the EC surface stimulates a STAT3 signaling cascade that promotes monocyte adhesion. Evans and colleagues have shown that IL6-IL6R signaling is critical for ICAM-1 induction in high endothelial venules 33, so induction of ICAM-1 (see Results) by this signaling cascade would further contribute to increased monocyte:endothelial interactions in ABCG1 KO EC. We cannot rule out that IL6 produced by other cellular sources in these mice also contribute to the observed increase in endothelial activation in vivo. However, our data indicate that the IL6-IL6R axis is induced in the ABCG1 KO EC, and we further demonstrate that this pathway, through STAT3 signaling, mediates induction of monocyte:endothelial interactions in these mice (Figure 4).

Although we observed increased Nile Red staining intensity in ABCG1 KO EC, we quantified only small increases in CE and TG content compared with B6 EC (Figure 1). Tall and colleagues have shown that ABCG1 KO macrophages from Western diet-fed mice have increased levels of 7-ketocholesterol 34. We did not quantify levels of 7-ketocholesterol in the current study, but since levels of this oxysterol are typically several orders of magnitude less than that of cholesterol, we do not think an increase in 7-ketocholesterol can explain the increased Nile Red staining of ABCG1 KO EC. A more likely explanation is related to the blue shift in fluorescence emission and increase in quantum yield reported for Nile Red with decreasing solvent polarity35. Thus, a small accumulation of triglycerides or redistribution of cholesteryl esters, especially into discrete punctuate subcellular structures, could enhance the signal intensity of Nile Red out of proportion to total cellular neutral lipid mass, as shown in Figure 1.

Intracellular location of accumulating neutral lipid may impact endothelial function. In several cell-types, ABCG1 is localized within intracellular membrane compartments, and may traffic to the plasma membrane for cholesterol efflux functions36,37. Very small changes in cholesterol content within specific cellular compartments can greatly influence cellular function. For example, minor changes in plasma membrane cholesterol content can significantly modify lipid raft formation, influencing cellular signaling events 38. Moreover, changes in cholesterol levels within intracellular vesicular compartments can influence receptor recycling 39. Finally, small changes in ER cholesterol content can influence ER stress, the unfolded protein response, and cytokine production 40. Tabas and colleagues have reported that trafficking of free cholesterol to the ER compartment of macrophages triggered IL6 production through activation of CHOP as part of the unfolded protein response 40. Thus, it is plausible that accumulation of neutral lipid within specific intracellular signaling compartments in ABCG1 KO EC could dramatically impact endothelial activation and IL6 signaling through one of the above mechanisms, and this may be reflected as only a minimal change in total cellular cholesterol content. Thus, both the total sterol content in the cell and its intracellular location could impact cell function. Studies to examine these concepts in EC and other cell types in ABCG1 KO mice are needed to fully understand the intracellular functions of ABCG1.

Recently, Tall and colleagues showed that eNOS activity was reduced in ABCG1 KO mouse aorta, yet they observed no change in eNOS expression or phosphorylation 14. We observed increased eNOS phosphorylation in aortic EC from ABCG1 KO mice (Supplemental Figure 3), although we did not measure eNOS activity. Our prior studies of EC function have suggested that eNOS phosphorylation leads to enhanced eNOS activity in aortic EC 41, although we did not directly measure eNOS activity in these cells. Since p-eNOS is believed to exert a protective effect in endothelium, we anticipate that eNOS phosphorylation is upregulated under basal conditions in ABCG1 KO mice as a counter-regulatory mechanism to the pro-inflammatory phenotype in these cells. It is difficult to directly compare our results with those of Tall’s group as we only measured phosphorylation of eNOS in isolated aortic EC and they measured both eNOS expression and activity in extracts from whole aorta. In whole aorta, SMC can release nitric oxide through eNOS action that certainly could influence both smooth muscle and endothelial responsiveness in the vessel wall 42. In either case, both studies clearly show that ABCG1 expression is important for protection against endothelial dysfunction in vivo.

A few minor points for discussion revolve around the HDL binding studies shown in Figure 5 and the known role of ABCG1 in cholesterol efflux. Studies by von Eckardstein reported that EC treated with ABCG1 siRNA showed reduced binding of HDL, which affected HDL transcytosis 29. Von Eckardstein’s study did not measure cholesterol efflux in their ABCG1 siRNA-treated EC. Although HDL transcytosis may be important for cholesterol efflux 43, it is not yet known how HDL and ABCG1 interact to facilitate cholesterol transfer, and it is most likely not through direct binding of the two molecules. In contrast to von Eckardstein’s work, we were unable to show significant reductions in HDL binding to ABCG1 KO EC although we did measure a significant reduction in cholesterol efflux. However, we used a fluorescent method for quantification of HDL binding as opposed to a radioiodination method, so there is the possibility that von Eckardstein’s method is more sensitive. Concomitant with our findings of similar levels of HDL binding, addition of HDL to B6 and ABCG1 KO EC worked equally well at reducing monocyte:endothelial interactions in an adhesion assay (Figure 5B), indicating that the well-characterized anti-inflammatory properties of HDL44-46 on endothelium are most likely independent of ABCG1. We also report that addition of soluble cholesterol to ABCG1 KO EC did not further stimulate adhesion or IL6 production (Figure 3), suggesting that the lipid content of the EC and cholesterol efflux are not based on physical binding of HDL to ABCG1 expressing cells.

In summary, we have identified the IL6-IL6R axis as an important regulator of monocyte:endothelial interactions in ABCG1 KO mice. In the absence of ABCG1, there is increased production of IL6 by endothelial cells, thereby stimulating IL6 receptor signaling to induce monocyte:endothelial interactions. Blockade of IL6R signaling in ABCG1 KO EC inhibits monocyte adhesion, and restoration of ABCG1 levels in ABCG1 KO EC block monocyte adhesion. Regulation of monocyte:endothelial interactions by ABCG1 appear to be independent of HDL binding. Thus, ABCG1 expression in endothelial cells is important for regulating the early inflammatory response in the vessel wall.

Condensed Abstract: Aortic endothelial cells (EC) from ABCG1-deficient mice have high expression of ICAM-1 and E-selectin, and elevated production of IL-6 and MCP-1. ABCG1 KO mice have increased monocyte:endothelial interactions in the aortic wall, which are due in part to induction of the IL6-IL6 receptor-STAT3 signaling pathway. Restoration of ABCG1 expression in ABCG1-deficient EC reduces monocyte:endothelial interactions through regulation of IL6-IL6R signaling.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH R01 grants HL085790 (to C.C.H.), HL049373 (to J.S.P.) and HL094525 (to J.S.P.).

Footnotes

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Angela M. Whetzel, Robert M. Berne Cardiovascular Research Center, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA 22908

David T. Bolick, Robert M. Berne Cardiovascular Research Center, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA 22908

Anthony C. Bruce, Robert M. Berne Cardiovascular Research Center, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA 22908

Marcus D. Skaflen, Robert M. Berne Cardiovascular Research Center, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA 22908

References

- 1.Witztum JL, Steinberg D. Role of oxidized low density lipoprotein in atherogenesis. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:1785–1792. doi: 10.1172/JCI115499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Springer TA. Traffic signals on endothelium for lymphocyte recirculation and leukocyte emigration. Annu Rev Physiol. 1995;57:827–872. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.004143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berliner JA, Navab M, Fogelman AM, Frank JS, Demer LL, Edwards PA, Watson AD, Lusis AJ. Atherosclerosis: basic mechanisms. Oxidation, inflammation, and genetics. Circulation. 1995;91:2488–2496. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.9.2488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berliner JA, Vora DK, Shih PT. Control of leukocyte adhesion and activation in atherogenesis. In: Pearson J, editor. Vascular Adhesion and Inflammation. Birkhauser Verlag; Basel, Switzerland: 2001. pp. 239–256. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vaughan AM, Oram JF. ABCA1 and ABCG1 or ABCG4 act sequentially to remove cellular cholesterol and generate cholesterol-rich HDL. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:2433–2443. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600218-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang N, Lan D, Chen W, Matsuura F, Tall AR. ATP-binding cassette transporters G1 and G4 mediate cellular cholesterol efflux to high-density lipoproteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:9774–9779. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403506101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang X, Collins HL, Ranalletta M, Fuki IV, Billheimer JT, Rothblat GH, Tall AR, Rader DJ. Macrophage ABCA1 and ABCG1, but not SR-BI, promote macrophage reverse cholesterol transport in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2216–2224. doi: 10.1172/JCI32057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mauldin JP, Nagelin MH, Wojcik AJ, Srinivasan S, Skaflen MD, Ayers CR, McNamara CA, Hedrick CC. Reduced expression of ATP-binding cassette transporter G1 increases cholesterol accumulation in macrophages of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2008;117:2785–2792. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.741314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Connell BJ, Denis M, Genest J. Cellular physiology of cholesterol efflux in vascular endothelial cells. Circulation. 2004;110:2881–2888. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000146333.20727.2B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fielding PE, Davison PM, Karasek MA, Fielding CJ. Regulation of sterol transport in human microvascular endothelial cells. J Cell Biol. 1982;94:350–354. doi: 10.1083/jcb.94.2.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeng L, Liao H, Liu Y, Lee TS, Zhu M, Wang X, Stemerman MB, Zhu Y, Shyy JY. Sterol-responsive element-binding protein (SREBP) 2 down-regulates ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 in vascular endothelial cells: a novel role of SREBP in regulating cholesterol metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:48801–48807. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407817200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yeh M, Cole AL, Choi J, Liu Y, Tulchinsky D, Qiao JH, Fishbein MC, Dooley AN, Hovnanian T, Mouilleseaux K, Vora DK, Yang WP, Gargalovic P, Kirchgessner T, Shyy JY, Berliner JA. Role for sterol regulatory element-binding protein in activation of endothelial cells by phospholipid oxidation products. Circ Res. 2004;95:780–788. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000146030.53089.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sima AV, Stancu CS, Simionescu M. Vascular endothelium in atherosclerosis. Cell Tissue Res. 2009;335:191–203. doi: 10.1007/s00441-008-0678-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Terasaka N, Yu S, Yvan-Charvet L, Wang N, Mzhavia N, Langlois R, Pagler T, Li R, Welch CL, Goldberg IJ, Tall AR. ABCG1 and HDL protect against endothelial dysfunction in mice fed a high-cholesterol diet. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3701–3713. doi: 10.1172/JCI35470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barter PJ, Nicholls S, Rye KA, Anantharamaiah GM, Navab M, Fogelman AM. Antiinflammatory properties of HDL. Circ Res. 2004;95:764–772. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000146094.59640.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Navab M, Hama SY, Anantharamaiah GM, Hassan K, Hough GP, Watson AD, Reddy ST, Sevanian A, Fonarow GC, Fogelman AM. Normal high density lipoprotein inhibits three steps in the formation of mildly oxidized low density lipoprotein: steps 2 and 3. J Lipid Res. 2000;41:1495–1508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Navab M, Berliner JA, Watson AD, Hama SY, Territo MC, Lusis AJ, Shih DM, Van Lenten BJ, Frank JS, Demer LL, Edwards PA, Fogelman AM. The Yin and Yang of oxidation in the development of the fatty streak. A review based on the 1994 George Lyman Duff Memorial Lecture. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1996;16:831–842. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.16.7.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Navab M, Hama SY, Cooke CJ, Anantharamaiah GM, Chaddha M, Jin L, Subbanagounder G, Faull KF, Reddy ST, Miller NE, Fogelman AM. Normal high density lipoprotein inhibits three steps in the formation of mildly oxidized low density lipoprotein: step 1. J Lipid Res. 2000;41:1481–1494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kennedy MA, Barrera GC, Nakamura K, Baldan A, Tarr P, Fishbein MC, Frank J, Francone OL, Edwards PA. ABCG1 has a critical role in mediating cholesterol efflux to HDL and preventing cellular lipid accumulation. Cell Metab. 2005;1:121–131. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bolick DT, Srinivasan S, Kim KW, Hatley ME, Clemens JJ, Whetzel A, Ferger N, Macdonald TL, Davis MD, Tsao PS, Lynch KR, Hedrick CC. Sphingosine-1-phosphate prevents tumor necrosis factor-{alpha}-mediated monocyte adhesion to aortic endothelium in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:976–981. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000162171.30089.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Srinivasan S, Hatley ME, Reilly KB, Danziger EC, Hedrick CC. Modulation of PPAR{alpha} Expression and Inflammatory Interleukin-6 Production by Chronic Glucose Increases Monocyte/Endothelial Adhesion. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004:851–857. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.zhq0504.2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Orr AW, Pallero MA, Murphy-Ullrich JE. Thrombospondin stimulates focal adhesion disassembly through Gi- and phosphoinositide 3-kinase-dependent ERK activation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:20453–20460. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112091200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hassan HH, Denis M, Krimbou L, Marcil M, Genest J. Cellular cholesterol homeostasis in vascular endothelial cells. Can J Cardiol. 2006;22(Suppl B):35B–40B. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(06)70985-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klucken J, Buchler C, Orso E, Kaminski WE, Porsch-Ozcurumez M, Liebisch G, Kapinsky M, Diederich W, Drobnik W, Dean M, Allikmets R, Schmitz G. ABCG1 (ABC8), the human homolog of the Drosophila white gene, is a regulator of macrophage cholesterol and phospholipid transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:817–822. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whetzel AM, Bolick DT, Srinivasan S, Macdonald TL, Morris MA, Ley K, Hedrick CC. Sphingosine-1 phosphate prevents monocyte/endothelial interactions in type 1 diabetic NOD mice through activation of the S1P1 receptor. Circ Res. 2006;99:731–739. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000244088.33375.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bolick DT, Whetzel AM, Skaflen M, Deem TL, Lee J, Hedrick CC. Absence of the G protein-coupled receptor G2A in mice promotes monocyte/endothelial interactions in aorta. Circ Res. 2007;100:572–580. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000258877.57836.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zidovetzki R, Levitan I. Use of cyclodextrins to manipulate plasma membrane cholesterol content: evidence, misconceptions and control strategies. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1768:1311–1324. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mukherjee S, Zha X, Tabas I, Maxfield FR. Cholesterol distribution in living cells: fluorescence imaging using dehydroergosterol as a fluorescent cholesterol analog. Biophys J. 1998;75:1915–1925. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77632-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rohrer L, Ohnsorg PM, Lehner M, Landolt F, Rinninger F, von Eckardstein A. High-density lipoprotein transport through aortic endothelial cells involves scavenger receptor BI and ATP-binding cassette transporter G1. Circ Res. 2009;104:1142–1150. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.190587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hassan HH, Denis M, Krimbou L, Marcil M, Genest J. Cellular cholesterol homeostasis in vascular endothelial cells. Can J Cardiol. 2006;22(Suppl B):35B–40B. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(06)70985-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yeh M, Leitinger N, de Martin R, Onai N, Matsushima K, Vora DK, Berliner JA, Reddy ST. Increased transcription of IL-8 in endothelial cells is differentially regulated by TNF-alpha and oxidized phospholipids. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:1585–1591. doi: 10.1161/hq1001.097027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaplanski G, Marin V, Montero-Julian F, Mantovani A, Farnarier C. IL-6: a regulator of the transition from neutrophil to monocyte recruitment during inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2003;24:25–29. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)00013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen Q, Fisher DT, Clancy KA, Gauguet JM, Wang WC, Unger E, Rose-John S, von Andrian UH, Baumann H, Evans SS. Fever-range thermal stress promotes lymphocyte trafficking across high endothelial venules via an interleukin 6 transsignaling mechanism. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:1299–1308. doi: 10.1038/ni1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Terasaka N, Wang N, Yvan-Charvet L, Tall AR. High-density lipoprotein protects macrophages from oxidized low-density lipoprotein-induced apoptosis by promoting efflux of 7-ketocholesterol via ABCG1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:15093–15098. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704602104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Greenspan P, Fowler SD. Spectrofluorometric studies of the lipid probe, nile red. J Lipid Res. 1985;26:781–789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ranalletta M, Wang N, Han S, Yvan-Charvet L, Welch C, Tall AR. Decreased atherosclerosis in low-density lipoprotein receptor knockout mice transplanted with Abcg1-/- bone marrow. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2308–2315. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000242275.92915.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tarr PT, Edwards PA. ABCG1 and ABCG4 are coexpressed in neurons and astrocytes of the CNS and regulate cholesterol homeostasis through SREBP-2. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:169–182. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700364-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lajoie P, Goetz JG, Dennis JW, Nabi IR. Lattices, rafts, and scaffolds: domain regulation of receptor signaling at the plasma membrane. J Cell Biol. 2009;185:381–385. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200811059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Balse E, El Haou S, Dillanian G, Dauphin A, Eldstrom J, Fedida D, Coulombe A, Hatem SN. Cholesterol modulates the recruitment of Kv1.5 channels from Rab11-associated recycling endosome in native atrial myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:14681–14686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902809106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li Y, Schwabe RF, Devries-Seimon T, Yao PM, Gerbod-Giannone MC, Tall AR, Davis RJ, Flavell R, Brenner DA, Tabas I. Free cholesterol-loaded macrophages are an abundant source of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-6: model of NF-kappaB- and map kinase-dependent inflammation in advanced atherosclerosis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:21763–21772. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501759200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Srinivasan S, Hatley ME, Bolick DT, Palmer LA, Edelstein D, Brownlee M, Hedrick CC. Hyperglycaemia-induced superoxide production decreases eNOS expression via AP-1 activation in aortic endothelial cells. Diabetologia. 2004 doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1525-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wei B, Chen Z, Zhang X, Feldman M, Dong XZ, Doran R, Zhao BL, Yin WX, Kotlikoff MI, Ji G. Nitric oxide mediates stretch-induced Ca2+ release via activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-Akt pathway in smooth muscle. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2526. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Curtiss LK. Is two out of three enough for ABCG1? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2175–2177. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000243741.89303.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Argraves KM, Gazzolo PJ, Groh EM, Wilkerson BA, Matsuura BS, Twal WO, Hammad SM, Argraves WS. High density lipoprotein-associated sphingosine 1-phosphate promotes endothelial barrier function. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:25074–25081. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801214200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watson AD, Berliner JA, Hama SY, La Du BN, Faull KF, Fogelman AM, Navab M. Protective effect of high density lipoprotein associated paraoxonase. Inhibition of the biological activity of minimally oxidized low density lipoprotein. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2882–2891. doi: 10.1172/JCI118359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barter PJ, Nicholls S, Rye KA, Anantharamaiah GM, Navab M, Fogelman AM. Antiinflammatory properties of HDL. Circ Res. 2004;95:764–772. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000146094.59640.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.