Abstract

Background

Life-sustaining medical care of cancer patients at the end-of-life (EOL) is costly. Patient-physician discussions about EOL wishes were found to be associated with lower rates of intensive interventions.

Methods

Coping with Cancer (CwC) is an NCI/NIMH-funded, longitudinal, multi-institutional study of 627 advanced cancer patients. Patients were interviewed at baseline and followed through death. Costs for ICU/hospital stays, hospice care and life-sustaining procedures (e.g., ventilation, resuscitation) received in the last week of life were aggregated. Generalized linear models were applied to test for cost differences in EOL care. Propensity score matching was used to reduce selection biases.

Results

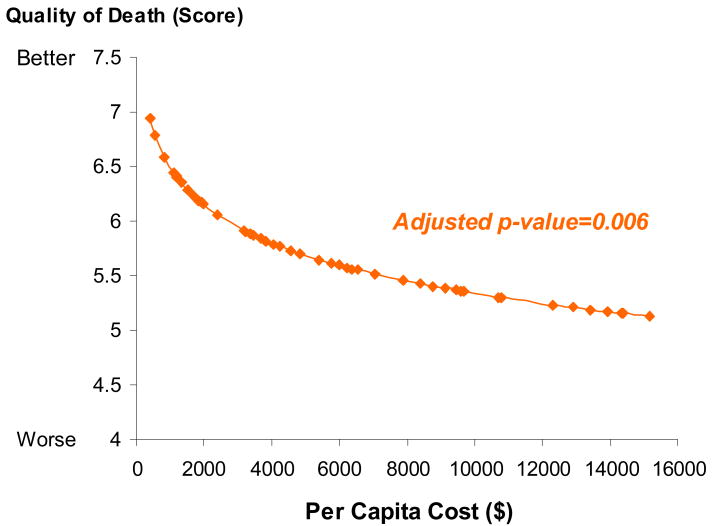

188 patients (31.2%) reported EOL discussions at baseline. After propensity score matching, the remaining 145 patients did not differ in socio-demographic characteristics, recruitment sites, illness acknowledgement or treatment preferences. Further analyses, adjusted by quintiles of propensity scores and significant confounders, revealed that the aggregate costs of care were $1876 (SE=177) for patients who reported EOL discussions compared with $2917 (SE=285) for patients who did not (in 2008 US dollars), a cost difference of $1041 (35.7% lower among patients who reported EOL discussions) [p=0.002]. Patients with higher costs had worse quality of death (Pearson partial r=-0.17, p=0.006) in their final week.

Conclusions

Advanced cancer patients who reported EOL conversations with physicians had significantly lower health care costs in their final week of life. Higher costs were associated with worse quality of death.

Keywords: cost, cancer, end-of-life care, patient-doctor communication

Introduction

U.S. health care expenditures exceeded $2 trillion in 2006 and are expected to rise rapidly over the next decade.1 A disproportionate share is spent at the end of life (EOL): 30% of Medicare expenditures are attributable to the 5% of beneficiaries who die each year;2 about one third of the expenditures in the last year of life is spent in the last month.3 Previous studies have found that most of these costs result from life-sustaining care (e.g. ventilator use and resuscitation), with acute care during the final 30 days of life accounting for 78% of costs incurred during the final year of life.4

A recent study, using data from a longitudinal, multi-institutional cohort study, Coping with Cancer (CWC), showed that EOL conversations between patients and physicians are associated with fewer life-sustaining procedures and lower rates of ICU admission.5 These findings suggest that EOL discussions might reduce health care expenditures by reducing cancer patients' utilization of intensive care. Singer et al. 6 have suggested that policies asking patients about their wishes regarding life-sustaining treatment and incorporating them into advance directives might result in cost savings by reducing undesired care at the EOL. However, other researchers 7,8 did not find the association between advance directives and cost deduction. To the best of our knowledge, the association between health care expenditures and patient-physician communication at the EOL has not been fully examined.

This study sought to monetize the differences in health care use during the final week of life for advanced cancer patients who reported having EOL discussions with their doctors compared to those who did not. We also examined the association between expenditures and patients' quality of life in the final week of life to determine whether the costly life-sustaining care might be justified by the better quality of life these expensive procedures may afford.

Methods

Study sample

Patients were recruited from September 1, 2002 to December 7, 2007, as part of an ongoing, prospective multi-institutional longitudinal evaluation (MH63892, CA106370) of advanced cancer patients and their primary, informal (unpaid) caregivers entitled the Coping with Cancer (CwC) Study. Participating sites included the Yale Cancer Center (New Haven, CT), the Veterans Affairs Connecticut Healthcare System Comprehensive Cancer Clinics (West Haven, CT), the Parkland Hospital Palliative Care Service (Dallas, TX), Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center (Dallas, TX), Massachusetts General Hospital (Boston, MA), Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (Boston, MA), and New Hampshire Oncology-Hematology (Hookset, NH). Approval was obtained from the human subjects committees of all participating centers; all enrolled patients provided written informed consent.

Eligibility criteria included:1) diagnosis of advanced cancer (presence of distant metastases, disease refractory to first-line chemotherapy, and a clinician's estimate that the patient would live less than six months); 2) diagnosis at a participating site; 3) age ≥ 20 years; 4) identified unpaid, informal caregiver; and 5) clinic staff and interviewer assessment that the patient had adequate stamina to complete the interview. Patient-caregiver dyads in which either the patient or caregiver met criteria for dementia or delirium (by neuro-behavioral cognitive status exam), or did not speak either English or Spanish, were excluded. Potentially eligible patients were identified by clinicians. Trained research staff approached identified patients to offer participation in a study examining patients' experiences coping with cancer. Once the patient's written informed consent was obtained, medical records and clinicians were consulted to confirm eligibility.

Of the 875 patients approached for inclusion into the study and confirmed to be eligible, 627 patients were enrolled. The most common reasons for nonparticipation (N=248, 28.3%) included “not interested” (N=118) or “caregiver refuses” (N=37). Compared with participants, non-participants were less likely to be of Hispanic ethnicity (5.5% vs. 13.5%; p=0.001). Otherwise, non-participants did not differ significantly from participants in age, gender, education, White, Black, or Asian race/ethnicity. Of the 627 patients enrolled, 603 (96.2%) responded to the question regarding prior EOL discussions that forms the basis for this study. Non-respondents for the EOL discussions did not differ significantly from respondents in socio-demographic characteristics, cancer type, health status, or recruitment site.

Protocol and measures

Each enrolled patient was interviewed at baseline (on average 6 months prior to death) and followed until death. Interviewers were trained by research staff at Yale University School of Medicine and were required to achieve a level of accuracy based on concordance with the Yale training director's rating of the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV (SCID) diagnoses (κ>0.85). The study was described to participants as a research protocol designed to understand how patients and their caregivers cope with cancer. Interviews were conducted in English or Spanish and took approximately 45 minutes to complete. Patients and caregivers received $25 as compensation for completing the interview. Information on care received in the last week of life was obtained from chart review.

Age, sex, marital status, race/ethnicity, years of schooling, religion, and insurance status were reported by patients at baseline. Each patient's primary cancer was identified by physicians and their functional status was assessed with the Karnofsky scale (scale 0-100, where 0=“dead” and 100=“asymptomatic”) 9 and the Charlson Index of Co-morbidity (scale 0-37, where higher scores indicate a greater burden of co-morbid conditions).10 Patient's self-reported health status was measured with the physical health and symptom burden subscales of the McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire [scale 0-10, where 0=desirable and 10=undesirable)].11

Patients were asked whether they trusted their physician and “If your doctor knew how long you had left to live, would you want him or her to tell you?” Patients were also asked whether they described their health status as “seriously and terminally ill” or not. EOL discussions were assessed at baseline by asking: “Have you and your doctor discussed any particular wishes you have about the care you would want to receive if you were dying?”

Patients were asked specific questions regarding individual treatment preferences at the EOL, e.g. “If you could choose, would you prefer 1) a course of treatment that focused on extending life as much as possible, even if it meant more pain and discomfort, or 2) on a plan of care that focused on relieving pain and discomfort as much as possible, even if that meant not living as long?” Medical services that patients received in the last week of life (e.g., ventilation, resuscitation, hospice care) were reported by either nurses present at patients' death or caregivers one month after the death. The type of care and length of stay were assessed by specific questions e.g. “Was the patient on a ventilator in the week leading up to his/her death?” and “If yes, how long prior to death? (in days)”; “For about how long did (patient) get inpatient hospice care before (his/her) death?”. After the patients' death, caregivers both formal (i.e., paid clinicians such as nurses) and informal (i.e., unpaid caretakers such as spouses) were asked to assess the patients' quality of life in the period immediately prior to death e.g. “In your opinion, how would you rate overall quality of the patient's death/last week of life?” The responses were measured on a 0-10 Likert scale.

Nationally representative per capita costs for hospital stays, including intensive medical procedures (e.g., ventilation, resuscitation), and hospice use were aggregated based on the EOL care each patient received in the last week of life. Cost data for hospitalizations that involved chemotherapy, resuscitation, ventilation, use of a feeding tube, or general hospital stays were taken from the 2004 Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) as part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) of Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.12 The NIS is the largest all-payer inpatient care database in the United States and includes inpatient data from a national sample of over 1,000 hospitals. Specifically, the cost data of different hospitalizations were extracted from an online query of HCUPnet by using ICD-9-CM codes or CCS category, which is a clinical grouper that puts ICD-9-CM codes into clinically homogeneous categories. Inpatient and outpatient hospice payments are cited from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), Office of the Actuary, Center for Heath Plans and Providers (November 2006).13 Data for routine home care and general inpatient care were used to calculate hospice costs. Because all payers use the same Medicare reimbursement cap for hospice care and HCUP is an all-payer inpatient database, both of the inpatient hospitalization and hospice costs aggregated in this analysis are from all-payer's perspective. Cost data have been inflated to US dollars in 2008 by using an inflation rate per year as measured by the US GDP deflator. 14

Statistical analysis

T-test, Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel, and χ2 test statistics were used, as appropriate, to test for significant differences in socio-demographic characteristics and other factors (e.g. recruitment sites, treatment preferences) between patients who did or did not report EOL discussions with their physicians at baseline. Propensity score matching15 was used to remove the observed differences between the two groups. Covariates, including age, gender, race, education, marriage status, health insurance, religion, Karnofsky score, Charlson Comorbidity Index, MQOL physical and symptom subscales, recruitment sites (Yale, Parkland, NHOH), treatment preferences and desire to know life expectancy, were included in predicting the conditional likelihood of having an EOL discussion. Each patient who reported an EOL conversation was matched to a patient who did not on the basis of an estimated propensity score by using the Greedy Algorithm (“gmatch” macro in sas)16 within a 0.01 caliper of propensity.17

Conditional on quintiles of the estimated propensity score in the deceased propensity-score matched cohort, logistic regression analyses were performed to test for differences in medical care use and location of death by EOL conversations. Stratified one-way ANOVA with fixed effect levels was conducted to examine the association between EOL discussions and continuous measures (e.g. patient's quality of life). Cox proportional hazards models were applied to examine differences in probability of survival for patients who reported EOL discussions versus those who did not. Generalized linear models,18 using a log link function and a gamma distribution specified for the error term, were performed to test for cost differences in EOL care during the week prior to death between patients who did and did not report EOL discussions. Models examined potential confounders of socio-demographic characteristics, religion, cancer type, recruitment sites, Karnofsky score, illness acknowledgement, treatment preferences and survival time using the backward selection procedure and controlled for those remained significant in the multivariate models. In addition, the association between cost and a patient's quality of life in the final week of life was investigated among deceased patients in the study sample (N=316). Particularly, the adjusted relationship between cost and patient's quality of death was plotted using a “LOWESS” procedure. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

Patient characteristics

The 603 advanced cancer patient participants were 71.3% White, 14.8% Black, 11.9% Hispanic, 1.7% Asian, and 51.1% male (Table 1). Among them, 188 (31.2%) reported having discussed their EOL wishes with physicians. Patient report of EOL discussions was not associated with age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, level of education, insurance status, religion, or cancer type. Rates of reporting EOL conversations did vary by treatment center (p<0.0001).

Table 1. Participants' Characteristics by End-Of-Life (EOL) Care Discussion (N=603).

| Total sample N (%) | Patient discussed EOL care preferences with physician | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| No. of cases; N (%) | 603 | 188 (31.2) | 415 (68.8) | |

| Age; mean (SD), yr | 59.0 (13.2) | 59.8 (12.9) | 58.6 (13.2) | 0.28 |

| Sex; N (%) | 0.86 | |||

| Male | 308 (51.2) | 95 (50.5) | 213 (51.3) | |

| Female | 295 (48.9) | 93 (49.5) | 202 (48.7) | |

| Race/Ethnicity; N (%) | 0.26 a | |||

| White, non-Hispanic | 430 (71.3) | 139 (73.9) | 291 (70.1) | 0.34 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 89 (14.8) | 26 (13.8) | 63 (15.2) | 0.66 |

| Hispanic | 72 (11.9) | 22 (11.7) | 50 (12.1) | 0.90 |

| Asian | 10 (1.7) | 0 (0) | 10 (2.4) | 0.04 b |

| Other | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | 0.53 |

| Marital status; N (%) | 0.27 | |||

| Married | 380 (64.1) | 112 (60.9) | 268 (65.5) | |

| Unmarried | 213 (35.9) | 73 (39.1) | 141 (34.5) | |

| Education; mean (SD), yr | 12.8 (4.0) | 12.8 (3.7) | 12.81 (4.1) | 0.97 |

| Health insurance; N (%) | 0.12 | |||

| Insured | 416 (69.1) | 119 (64.7) | 293 (71.1) | |

| Uninsured | 184 (30.9) | 65 (35.3) | 119 (28.9) | |

| Religion; N (%) | 0.97 a | |||

| Catholic | 259 (43.0) | 82 (43.6) | 177 (42.8) | 0.84 |

| Protestant | 112 (18.6) | 33 (17.6) | 79 (19.1) | 0.66 |

| Jewish | 19 (3.2) | 5 (2.7) | 14 (3.4) | 0.64 |

| Baptist | 67 (11.1) | 23 (12.2) | 44 (10.6) | 0.56 |

| Other | 99 (16.5) | 28 (14.9) | 71 (17.2) | 0.49 |

| None | 32 (5.3) | 11 (5.9) | 21 (5.1) | 0.69 |

| Cancer type; N (%) | 0.80 | |||

| Breast | 64 (10.8) | 21 (11.5) | 43 (10.5) | 0.73 |

| Colorectal | 68 (11.5) | 25 (13.7) | 43 (10.5) | 0.27 |

| Pancreatic | 50 (8.5) | 15 (8.2) | 35 (8.6) | 0.88 |

| Other GI | 74 (12.5) | 20 (10.9) | 54 (13.2) | 0.44 |

| Lung | 144 (24.3) | 41 (22.4) | 103 (25.2) | 0.47 |

| Other c | 203 (33.7) | 66 (34.1) | 137 (33.0) | 0.61 |

| Health status; mean (SD) | ||||

| Karnofsky score | 67.3 (16.8) | 61.8 (16.7) | 69.8 (16.2) | <0.0001 |

| Charlson comorbidity | 8.2 (2.7) | 8.7 (2.8) | 8.0 (2.6) | 0.002 |

| McGill physical subscale d | 6.1 (2.7) | 4.4 (2.8) | 3.7 (2.6) | 0.002 |

| McGill symptom subscale d | 11.3 (4.4) | 9.9 (4.3) | 8.1 (4.4) | <0.0001 |

| Recruitment site; N (%) | <0.0001 | |||

| Yale Cancer Center | 153 (26.7) | 20 (11.4) | 133 (33.5) | <0.0001 |

| VACCC e | 21 (3.7) | 10 (5.7) | 11 (2.8) | 0.09 |

| Parkland Hospital f | 178 (31.1) | 67 (38.1) | 111 (28.0) | 0.02 |

| Simmons Center g | 40 (7.0) | 8 (4.6) | 32 (8.1) | 0.13 |

| DFCI/MGH h | 47 (8.2) | 13 (7.4) | 34 (8.6) | 0.64 |

| NHOH i | 131 (22.9) | 57 (32.4) | 74 (18.6) | 0.0003 |

| Illness Acknowledgement | ||||

| Wants to know life expectancy | 426 (71.6) | 149 (80.1) | 277 (67.7) | 0.002 |

| Trusts physician | 591 (98.8) | 185 (98.9) | 406 (98.8) | 1.00 b |

| Acknowledge yourself to be terminal ill | 203 (34.3) | 95 (52.2) | 108 (26.3) | <0.0001 |

| Treatment preferences | ||||

| Values life extension over comfort | 158 (29.0) | 25 (14.0) | 133 (36.2) | <0.0001 |

| Prefers everything possible to extend life for a few days | 122 (20.7) | 29 (15.6) | 93 (23.1) | 0.04 |

| Prefers chemotherapy to extend life | 311 (52.7) | 87 (47.0) | 224 (55.3) | 0.06 |

| Prefers ventilator to extend life | 142 (24.1) | 36 (19.3) | 106 (26.4) | 0.06 |

| Preference against death in ICU | 221 (38.2) | 90 (48.9) | 131 (33.3) | 0.0003 |

Note: Italicized rows represent continuous measures; mean and standard deviation (SD) shown.

Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel statistics due to small cells.

Fisher's exact test due to small cells.

The remaining patients had cancer types representing <5% of the sample.

McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire Items (scale 0-10) where 0 is desirable and 10 is undesirable.

VACCC=Veterans Affairs Connecticut Healthcare System Comprehensive Cancer Clinics.

Parkland Hospital=Parkland Hospital Palliative Care Service, Texas.

Simmons Center=Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center, Texas.

DFCI/MGH =Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Massachusetts General Hospital.

NHOH=New Hampshire Oncology Hematology.

Patients reporting EOL discussions had worse performance [Karnofsky Performance Score: 61.8(16.7) vs. 69.8(16.2), p<0.0001], more co-morbid conditions [Charlson Co-morbidity Index: 8.7(2.8) vs. 8.0(2.6), p=0.002], and higher symptom burden [MQOL Physical Health Subscale: 4.4(2.8) vs. 3.7(2.6), p=0.002; MQOL Symptom Subscale: 9.9(4.3) vs. 8.1(4.4), p<0.0001]. Patients who reported EOL discussions with their physicians wanted to know their life expectancy (80.1% vs. 67.7%, p=0.002), acknowledged they were terminally ill (52.2% vs. 26.3%, p<0.0001) and reported a preference to avoid dying in the ICU (48.9% vs. 33.3%, p=0.0003). They were less likely to prefer life extension over comfort (14.0% vs. 36.2%, p<0.0001) or prefer the doctors to do everything possible to extend life for a few days (15.6% vs. 23.1%, p=0.04).

As shown in Table 2, after propensity-score matching, the respondents who reported an EOL discussion and those who did not were made essentially balanced on all of the variables listed in Table 1.

Table 2. Recipient Characteristics: Patients Reporting End of Life Conversations vs. Not in Propensity-Score Matched Groups (N=248).

| Patient discussed EOL care preferences with physician | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes 124 (50.0%) |

No 124 (50.0%) |

p-value | |

| Baseline socio-demographic variables | |||

| Age; mean (SD) | 58.8 (13.3) | 60.0 (13.7) | 0.50 |

| Male sex; N (%) | 60 (48.4) | 57 (46.0) | 0.70 |

| Race/Ethnicity; N (%) | 0.71 | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 85 (68.55) | 84 (67.7) | 0.89 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 21 (16.9) | 20 (16.1) | 0.86 |

| Hispanic | 17 (13.7) | 19 (15.3) | 0.72 |

| Asian | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | 1.00 |

| Marriage; N (%) | 75 (60.5) | 73 (58.9) | 0.80 |

| Education; mean (SD) | 12.2 (3.7) | 12.4 (3.8) | 0.65 |

| Health Insurance; N (%) | 72 (58.1) | 74 (60.0) | 0.80 |

| Religion; N (%) | 0.98 | ||

| Catholic | 55 (44.35) | 58 (46.77) | 0.70 |

| Protestant | 18 (14.5) | 19 (15.3) | 0.86 |

| Jewish | 3 (2.4) | 4 (3.2) | 1.00 |

| Baptist | 20 (16.1) | 18 (14.5) | 0.72 |

| Other | 13 (17.3) | 16 (22.9) | 0.41 |

| None | 6 (8.00) | 1 (1.4) | 0.12 |

| Cancer Type; N (%) | 0.94 | ||

| Breast | 12 (9.8) | 17 (13.7) | 0.33 |

| Colorectal | 20 (16.3) | 15 (12.1) | 0.35 |

| Pancreatic | 10 (8.1) | 11 (8.9) | 0.83 |

| Other GI | 14 (11.4) | 16 (12.9) | 0.71 |

| Lung | 27 (22.0) | 27 (21.8) | 0.97 |

| Other c | 41 (33.1) | 38 (30.7) | 0.68 |

| Baseline Health Status; mean (SD) | |||

| Karnofsky score | 66.0 (15.6) | 66.0 (16.6) | 0.97 |

| Charlson index | 8.4 (2.6) | 8.7 (2.6) | 0.35 |

| McGill physical subscale a | 6.0 (2.7) | 5.8 (2.9) | 0.60 |

| McGill symptom subscale a | 10.6 (4.3) | 10.2 (4.3) | 0.48 |

| Recruitment Site; N (%) | 0.55 | ||

| Yale Cancer Center | 14 (11.3) | 14 (11.3) | 1.00 |

| VACCC b | 8 (6.5) | 4 (3.2) | 0.24 |

| Parkland Hospital c | 56 (45.2) | 54 (43.6) | 0.80 |

| Simmons Center d | 7 (5.7) | 13 (10.5) | 0.17 |

| DFCI/MGH e | 12 (9.7) | 8 (6.5) | 0.35 |

| NHOH f | 27 (21.8) | 29 (23.4) | 0.76 |

| Illness Acknowledgement, N (%) | |||

| Wants to know life expectancy | 92 (74.2) | 95 (76.6) | 0.66 |

| Trust physician | 122 (99.2) | 120 (98.4) | 0.62 |

| Acknowledge yourself to be terminal ill | 49 (39.5) | 45 (36.3) | 0.60 |

| Treatment Preferences, N (%) | |||

| Values life extension over comfort | 20 (16.1) | 16 (12.9) | 0.47 |

| Prefers everything possible to extend life for a few days | 24 (19.4) | 24 (19.4) | 1.00 |

| Prefers chemotherapy to extend life | 72 (58.1) | 71 (57.3) | 0.90 |

| Prefers ventilator to extend life | 27 (21.8) | 26 (21.0) | 0.88 |

| Preference against death in ICU | 52 (41.9) | 47(37.9) | 0.52 |

Note: Italicized rows represent continuous measures; mean and standard deviation (SD) shown.

McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire Items (scale 0-10) where 0 is desirable and 10 is undesirable.

VACCC=Veterans Affairs Connecticut Healthcare System Comprehensive Cancer Clinics.

Parkland Hospital=Parkland Hospital Palliative Care Service, Texas.

Simmons Center=Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center, Texas.

DFCI/MGH =Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Massachusetts General Hospital.

NHOH=New Hampshire Oncology Hematology.

The matched (N=248) and unmatched (N=355) subjects did not differ by age, gender, race, cancer type, Karnofsky score or McGill QOL physical subscale. However, the matched subjects were less educated [12.3(3.8) vs. 13.1(4.1) schooling years, p=0.01], more likely to be Baptist (15.3% vs. 8.2%, p=0.006), and less likely to be insured (58.9% vs. 76.4%, p=0.0001). They had more co-morbid conditions [8.5(2.7) vs. 7.9(2.7), p=0.007) but lower symptom burden [McGill symptoms subscale score [10.4(4.3) vs. 12.0(4.4), p<0.0001)]. They also differed from the unmatched subjects by recruitment sites (Yale, Parkland) and treatment preferences.

Medical care at EOL, location of death, quality of death and survival

The deceased patients in the propensity-score matched cohort (N=145) did not differ by the variables shown in Table 2. Patients who reported EOL conversations with their physicians at baseline were less likely to undergo ventilation, resuscitation, be admitted to or die in an ICU in the final week of life. They were more likely to receive outpatient hospice care and stay longer in hospice. Patients who reported EOL discussions had less physical distress in the last week of life [3.6 (3.2) vs. 4.5 (3.7), p=0.04] than those who did not, but the two groups did not differ in psychological distress, quality of death or survival.

Medical costs in the final week of life associated with EOL discussions

Adjusted analyses, using the deceased propensity-score matched cohort (N=145), revealed that the aggregate medical costs for EOL care were $1876 (SE=177) for patients who reported EOL discussions compared with $2917 (SE=285) for patients who did not in 2008 US dollars. The costs of care were 35.7% lower among those who reported EOL discussions compared to those who did not (cost difference=$1041; p=0.002).

Association between medical costs, patients' quality of death and survival in the final week of life

Additional analyses using deceased patients in the study sample (N=316) showed that higher medical costs in the final week of life were associated with more physical distress in the last week of life (Pearson partial r=0.18, p=0.003) and worse overall quality of death as reported by the caregiver (Pearson partial r=-0.17, p=0.006) after controlling for age, race, gender, education, survival and source of report. There was no survival difference associated with higher health care expenditures at the EOL.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate that advanced cancer patients who reported EOL conversations with physicians had lower medical costs in their final week of life compared to those who did not, which is largely a function of their more limited use of intensive interventions. In this study, higher health care costs were not associated with better outcomes at the EOL: there was no survival difference associated with health care expenditures, and patients who spent more in insured health care had worse quality of life in their final week of life. These results also support findings from another CwC study that life-sustaining care is associated with worse quality of death at the EOL. 19

One strength of this study is that the matched subjects did not differ in observed variables, including patients' socio-demographic characteristics, cancer type, recruitment sites, treatment preferences, or illness acknowledgment. Additionally, these variables were also examined as potential confounders and were controlled for if they remained significant in the multivariate analyses. Therefore, the results were drawn based upon a well balanced and adjusted study sample.

Our cost estimates may be conservative in terms of the relatively low frequency of intensive medical treatment compared to other studies of advanced cancer patients. For example, our study participants had lower rate of chemotherapy use (6.7% vs. 15.7%) compared to another study; 20 and they were less likely to die in the ICU (4.7% vs. 8.0%) 21 where the highest medical costs are often incurred. Study subjects also had higher rates of hospice use (74.3% vs. 38.8%) and were more likely to die at home (53.8% vs. 37.8%) compared to national averages and other studies. 22, 23 Despite this, and a relatively low power to detect differences in EOL care, our cost estimates yielded significant results.

Because this is an observational study we cannot conclude that there is a causal relationship between EOL conversations and cost differences in the last week of life. Although propensity score matching is one of the most robust methods to correct for selection bias in observables, it cannot account for hidden biases.

Another limitation is that cost estimates were based upon aggregated costs from national averages for hospitalizations, life-sustaining procedures and hospice care instead of medical claims data. Although this method may be viewed as less accurate, our cost estimates are comparable to other studies that used medical claims data.23,24 Like most studies of medical expenditures 2,3, 23,24 which rely heavily on costs covered by insurers or Medicare, this study likely underestimates the total cost of care given that it does not include out-patient services or out-of-pocket expenditures or opportunity costs incurred by patients and their caregivers for additional pharmaceutical and home care payments.

Moreover, the EOL care and patients' quality of life in the final week before death were reported by nurses or informal caregivers. Future research should use a consistent source of reporting of patient's quality of death and examine the way the relationship of the care provider to the patient affects assessment of patient's degree of comfort and quality of care. Additionally, we acknowledge that patients and caregivers may value care differently. Patients may consider extra dollars spent and more life-sustaining care worth the added expense whereas caregivers may devalue life-sustaining care. In addition, exclusion of unmatched subjects from the study may limit generalizability of the results to general population.

Lastly, the health care costs near the end of life rise exponentially. Further research is needed to examine whether the cost difference remains significant or not over a longer period of time close to death. A study following advanced cancer patients longitudinally over the final months of life with paired survey data and claims data to capture monthly measurements of costs might provide a more accurate and dynamic estimate of the impact of EOL conversations on health care costs in the period leading up to the patient's death.

Despite these limitations, our findings suggest a potential strategy for reducing medical care expenditures and improving patients' quality of life at the EOL. If the national proportion of reporting EOL discussions were increased to 50%, our results suggest that we would expect a cost difference of $76,466,891, between individuals who had EOL discussions versus who had not, based upon the total number of US cancer deaths/year. 25

There are several reasons to be cautious about this estimate. The cost differences we observed may decrease when generalized to an older population since medical costs at the EOL decline with increasing age, and the average age in our sample was 59 years. 26 Although propensity-score matching balanced differences among the recruitment sites, our study does not include all geographic areas in the United States which may be particularly important since there are documented regional differences in the intensity of EOL care. 27 Due to a lower rate of acute care and greater use of hospice care in our sample compared to the national population, the cost differences might increase when generalized to other areas with higher use of intensive care.

Nevertheless, our study suggests that increasing communication between patients and their physicians is associated with better outcomes and less expensive medical care. These results are consistent with other studies that have shown that the greatest cost differences come from a reduction in acute care services at the end of life.4, 28 Our study is unique in that it also suggests that these cost deductions are accompanied by a better quality of life for advanced cancer patients at the EOL. Policies that promote increased communication, such as direct reimbursement for EOL conversations, enhanced physician education about EOL communication, expansion of palliative care programs in hospitals and co-management of late stage cancer patients by oncologists and palliative care physicians, may be cost-effective ways to both improve care and reduce some of the rising health care expenditures.

Figure 1. Association between Cost and Quality of Death in the Final Week of Life.

Note: Socio-demographic characteristics of age, race, gender and education, survival time and source of report were controlled for in the adjusted analyses of per capita cost predicting quality of death in the deceased cohort (N=316).

Table 3. Comparison of Patient Characteristics Between the Matched and Unmatched Subjects (N=248 vs. 355).

| Matched Subjects | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes 248 (41.1%) |

No 355 (58.9%) |

||

| Baseline socio-demographic variables | |||

| Age; mean (SD) | 59.4 (13.5) | 58.7 (12.8) | 0.54 |

| Male sex; N (%) | 117 (47.2) | 191(53.8) | 0.11 |

| Race/Ethnicity; N (%) | 0.10 | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 169 (68.2) | 261 (73.5) | 0.15 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 41 (16.5) | 48 (13.5) | 0.31 |

| Hispanic | 36 (14.5) | 36 (10.1) | 0.10 |

| Asian | 1 (0.4) | 9 (2.5) | 0.05 |

| Marriage; N (%) | 100 (40.3) | 113 (32.8) | 0.06 |

| Education; mean (SD) | 12.3 (3.8) | 13.1 (4.1) | 0.01 |

| Health Insurance; N (%) | 146 (58.9) | 266 (76.4) | 0.0001 |

| Religion; N (%) | 0.04 | ||

| Catholic | 113 (45.6) | 146 (41.2) | 0.29 |

| Protestant | 37 (14.9) | 75 (21.2) | 0.05 |

| Jewish | 7 (2.8) | 12 (3.4) | 0.70 |

| Baptist | 38 (15.3) | 29 (8.2) | 0.006 |

| Other | 12 (4.8) | 20 (5.7) | 0.66 |

| None | 6 (8.0) | 1 (1.4) | 0.20 |

| Cancer Type; N (%) | 0.45 | ||

| Breast | 29 (11.7) | 35 (10.1) | 0.54 |

| Colorectal | 35 (14.2) | 33 (9.6) | 0.08 |

| Pancreatic | 21 (8.5) | 29 (8.4) | 0.97 |

| Other GI | 30 (12.2) | 44 (12.8) | 0.83 |

| Lung | 54 (21.9) | 90 (26.1) | 0.24 |

| Other c | 79 (31.9) | 124 (34.9) | 0.43 |

| Baseline Health Status; mean (SD) | |||

| Karnofsky score | 66.0 (16.1) | 68.3 (17.2) | 0.11 |

| Charlson index | 8.5 (2.7) | 7.9 (2.7) | 0.007 |

| McGill physical subscale a | 5.9 (2.8) | 6.2 (2.6) | 0.32 |

| McGill symptom subscale a | 10.4 (4.3) | 12.0 (4.4) | <0.0001 |

| Recruitment Site; N (%) | <0.0001 | ||

| Yale Cancer Center | 28 (11.3) | 125 (38.5) | 0.0001 |

| VACCC b | 12 (4.8) | 9 (2.8) | 0.20 |

| Parkland Hospital c | 110 (44.4) | 68 (20.9) | <.0001 |

| Simmons Center d | 20 (8.1) | 20 (6.2) | 0.37 |

| DFCI/MGH e | 20 (8.1) | 27 (8.3) | 0.92 |

| NHOH f | 56 (22.6) | 75 (23.1) | 0.89 |

| Illness Acknowledgement, N (%) | |||

| Wants to know life expectancy | 187 (75.4) | 239 (68.9) | 0.08 |

| Trust physician | 242 (98.8) | 349 (98.9) | 1.00 |

| Acknowledge yourself to be terminal ill | 94 (37.9) | 109 (31.7) | 0.12 |

| Treatment Preferences, N (%) | |||

| Values life extension over comfort | 36 (14.5) | 122 (34.4) | <.0001 |

| Prefers everything possible to extend life for a few days | 48 (19.4) | 74 (21.7) | 0.49 |

| Prefers chemotherapy to extend life | 143 (57.7) | 168 (49.1) | 0.04 |

| Prefers ventilator to extend life | 53 (21.4) | 89 (26.1) | 0.19 |

| Preference against death in ICU | 99 (39.9) | 122 (37.0) | 0.47 |

Note: Italicized rows represent continuous measures; mean and standard deviation (SD) shown.

McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire Items (scale 0-10) where 0 is desirable and 10 is undesirable.

VACCC=Veterans Affairs Connecticut Healthcare System Comprehensive Cancer Clinics.

Parkland Hospital=Parkland Hospital Palliative Care Service, Texas.

Simmons Center=Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center, Texas.

DFCI/MGH =Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Massachusetts General Hospital.

NHOH=New Hampshire Oncology Hematology.

Table 4. Medical Care, Location of Death, Quality of Death and Survival by EOL Discussion among Deceased Propensity-Score Matched Patients (N=145) a.

| Patient discussed EOL care preferences with physician | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | AOR b | (95%CI) | p-value | ||

| No. of cases; N (%) | 75 (51.7) | 70 (48.3) | ||||

| Medical care received in last week; N (%) | ||||||

| ICU stay | 2 (2.7) | 10 (14.3) | 0.01 | (0.02-0.6) | 0.01* | |

| Ventilator use | 1 (1.3) | 10 (14.3) | 0.03 | (0.002-0.3) | 0.005** | |

| Resuscitation | 1 (1.4) | 6 (8.7) | 0.1 | (0.02-1.3) | 0.09§ | |

| Chemotherapy | 4 (5.3) | 7 (10.0) | 0.5 | (0.1-1.8) | 0.30 | |

| Inpatient hospice utilized | 8 (10.7) | 5 (7.1) | 1.8 | (0.5-6.5) | 0.34 | |

| Inpatient hospice stay ≥ 1 week | 4 (5.4) | 2 (3.0) | 3.7 | (0.4-38.2) | 0.27 | |

| Outpatient hospice utilized | 58 (77.3) | 40 (57.1) | 3.2 | (1.5-6.9) | 0.004** | |

| Outpatient hospice stay ≥ 1 week | 52 (69.3) | 34 (50.8) | 2.5 | (1.2-5.0) | 0.01* | |

| Place of Death; N (%) | ||||||

| ICU | 2 (2.7) | 9 (12.9) | 0.1 | (0.03-0.7) | 0.02* | |

| Hospital | 15 (20.0) | 18 (25.7) | 0.7 | (0.3-1.6) | 0.45 | |

| Inpatient Hospice | 5 (6.7) | 3 (4.3) | 1.9 | (0.4-8.8) | 0.44 | |

| Home | 47 (62.7) | 38 (54.3) | 1.3 | (0.6-2.6) | 0.49 | |

| Quality of Life in the Last Week of Life; cmean (S.D.) | β | SE | p-value | |||

| Psychological Distress | 3.7 (3.0) | 3.2 (3.3) | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.37 | |

| Physical Distress | 3.6 (3.2) | 4.5 (3.7) | -1.2 | 0.6 | 0.04* | |

| Quality of Death | 6.3 (2.7) | 5.7 (3.3) | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.39 | |

| HR | (95%CI) | p-value | ||||

| Survival; median (quartiles) | 88 [54-218] | 85 [30-253] | 0.8 | (0.6-1.1) | 0.22 | |

Borderline significant 0.05≤p-value<0.10

p-value<0.05

p-value<0.01

p-value<0.001

Among the deceased propensity-matched patients, all variables shown in Table 2 did not differ by EOL discussions.

The OR here is conditional on quintiles of predicted propensity scores and adjusted for confounders of socio-demographic characteristics, health status measures, recruitment sites, terminal illness acknowledgement, treatment preferences and survival if they remain significant in the multivariate model.

Rated at postmortem. Higher score indicates more distress for psychological and physical scales whereas higher score indicates better quality of life.

Table 5. Association of Cost Experience in the Final Week of Life with EOL Discussion among Deceased Propensity-Score Matched Patients (N=145) a.

| Factor Associated with Cost | Parameter Estimate | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate Model b | Multivariate Model b | |||||

| β | SE | p-value | β | SE | p-value | |

| EOL discussion with physician at baseline | -0.4 | 0.2 | 0.02 | -0.4 | 0.1 | 0.002 |

| Male gender | 0.5 | 0.1 | <.0001 | |||

| Race/ethnicity (Black) | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.005 | |||

| Site of parkland c | -0.4 | 0.1 | 0.02 | |||

| McGill physical subscale d | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.04 | |||

| Values life extension over comfort | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.003 | |||

| Outcome | EOL Discussion with Physician | EOL Discussion with Physician | ||||

| Yes | No | χ2 test | Yes | No | χ2 test | |

| Means (S.D.) | Least Square Means (S.D.) | |||||

| Cost e per Patient | $1925 (203) |

$2780 (303) |

χ2=5.7 d.f.=1 p=0.02 |

$1876 (177) |

$2917 (285) |

χ2=9.9 d.f.=1 p=0.002 |

| Cost e Difference per Patient | $855 (30.8% f) | $1041 (35.7% f) | ||||

Notes:

The average costs at the national level for hospital stay with ventilator use, resuscitation, being on a feeding tube, chemotherapy and general hospital stay are from the HCUPnet (Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project) of Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). URL: http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov/. The in- and out-patient hospice cost data are from Hospice Facts & Statistics, 2007 reported by the National Association for Home Care & Hospice. URL: http://www.nahc.org/facts/hospicefx07.pdf. Original citation is from Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), Office of the Actuary, Center for Heath Plans and Providers (November 2006). All cost data have been inflated to US dollars in 2008 by using an inflation rate per year as measured by the US GDP deflator.

Among the deceased propensity-matched patients, all variables shown in Table 2 did not differ by EOL discussions.

Generalized linear regression with a log link and a gamma distribution for the error term was used to model the total cost and significant confounders of gender, Black race, the treatment center of Parkland, McGill physical subscale and preference for life extension were controlled for in the multivariate model.

Parkland Hospital=Parkland Hospital Palliative Care Service, Texas.

McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire Items (scale 0-10) where 0 is desirable and 10 is undesirable.

The cost used in this study was aggregate cost for life-sustaining and/or hospice care received in the last week prior to death. Detailed discussion is referred to the text.

The percentages showed how much cost can be saved per patient by having EOL discussion with physicians.

Table 6. Association of Patient's Quality of Life and Survival with Cost Experience during the Final Week of Life in the Deceased Cohort (N=316).

| Medical Cost in the Final Week of Life | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Analyses | Adjusted Analyses b | |||||

| β | SE | p-value | β | SE | p-value | |

| Quality of Life at Postmortem a | ||||||

| Psychological Distress | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.06§ | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.09§ |

| Physical Distress | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.008** | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.003** |

| Quality of Death | -0.5 | 0.2 | 0.003** | -0.5 | 0.2 | 0.006** |

| HR | 95% CI | p-value | HR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Survival c | 0.8 | (0.7-1.0) | 0.007** | 1.0 | (0.9-1.1) | 0.7 |

Note:

Borderline significant 0.05≤p-value<0.10

p-value<0.05

p-value<0.01

p-value<0.001

Higher score indicates more distress for psychological and physical scales whereas higher score indicates better quality of life.

In the adjusted analyses, age, race, gender, education, survival and source of report were controlled for.

In the adjusted analyses for survival, age, race, gender and education and significant confounders of health insurance, Karnofsky score and treatment site of New Hampshire Oncology Hematology were controlled for.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the following grants to Dr. Prigerson: MH63892 from the National Institute of Mental Health and CA 106370 from the National Cancer Institute; the Center for Psycho-Oncology and Palliative Care Research, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

Funding Source: This study was supported in part by the following grants: Dr. Prigerson: MH63892 from the National Institute of Mental Health; CA 106370 from the National Cancer Institute; the Center for Psycho-Oncology and Palliative Care Research, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. Sponsors did not influence the analyses or reporting of the results in any way.

Footnotes

Disclosure: None of the authors have relationships with any entities having financial interest in this topic.

References

- 1.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Office of the Actuary, National Health Statistics Group, 2006 National Health Care Expenditures Data, January 2008.

- 2.Barnato Amber E, McClellan Mark B, Kagay Christopher R, Garber Alan M. Trends in inpatient treatment intensity among Medicare beneficiaries at the end of life. Health Services research. 2004 April;39(2) doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00232.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Emanuel Ezekiel J, Ash Arlene, Yu Wei, Gazelle Gail, Levinsky Norman G, Saynina Olga, McClellan Mark, Moskowitz Mark. Managed care, hospice use, site of death, and medical expenditures in the last year of life. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2002 Aug 12/26;162 doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.15.1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu W. End of Life Care: Medical Treatments and Costs by Age, Race, and Region. HSR&D study IIR 02-189. URI: http://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/research/abstracts/IIR_02-189.htm.

- 5.Wright Alexi A, Zhang Baohui, Ray Alaka, Mack Jennifer W, Trice Elizabeth, Balboni Tracy, Mitchell Susan L, Jackson Vicki A, Block Susan D, Maciejewski Paul K, Prigerson Holly G. Associations between end-of-1 life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665. (resubmitted) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singer PA, Lowy FH. Rationing, patient preferences and cost of care at the end of life. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152:478–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schneiderman LJ, Kronick R, Kaplan RM, Anderson JP, Langer RD. Effects of offering advance directives on medical treatments and costs. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:599–606. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-117-7-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teno J, Lynn J, Phillips R, et al. Do advance directives save resources? Clin Res. 1993;41:551A–551A. abstract. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karnofsky D, Abelmann W, Craver L, Burchenal J. The use of nitrogen mustard in the palliative treatment of cancer. Cancer. 1948;1:634–656. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen SR, Mount BM, Bruera E, et al. Validity of the McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire in the palliative care setting: a multi-centre Canadian study demonstrating the importance of the existential domain. Palliat Med. 1997;11:3–20. doi: 10.1177/026921639701100102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.URL: http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov/.

- 13.The in- and out-patient hospice cost data are from Hospice Facts & Statistics, 2007 reported by the National Association for Home Care & Hospice. 2006 November; URL: http://www.nahc.org/facts/hospicefx07.pdf. Original citation is from Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), Office of the Actuary, Center for Heath Plans and Providers.

- 14.Bureau of Economic Analysis, National Economic Accounts. URL: http://www.bea.gov/national/index.htm#gdp. Updated on January 31, 2008.

- 15.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70:41–55. doi: 10.1093/biomet/70.1.41. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parsons LS. Reducing bias in a propensity score matched-pair sample using greedy matching techniques. [Accessed July 15, 2006.]; http://www2.sas.com/proceedings/sugi26/p214-26.pdf.

- 17.Drake C, Fisher L. Prognostic models and the propensity score. Int J Epidemiol. 1995;24:183–187. doi: 10.1093/ije/24.1.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blough DK, Ramsey SD. Using generalized linear models to assess medical care costs. Health Services & Outcomes Research Methodology. 2000;1(2):185–202. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silverman GK, Temel J, Podgurski LM, Hickey MK, Paulk EM, Jackson VA, Block SD, Buss MK, Prigerson HG. Do aggressive treatments in the last week of life harm quality of death?. American Geriatrics Society Annual Scientific Meeting; Seattle, WA. May 3, 2007. (Oral Presentation) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Earle CC, Neville BA, Landrum MB, Ayanian JZ, Block SD, Weeks JC. Trends in the aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life. J Clin Oncol. 2004 Jan 15;22(2):315–21. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Angus DC, Barnato AE, Linde-Zwirble WT, Weissfeld LA, Watson S, Rickert T, Rubenfeld GD. Use of intensive care at the end of life in the United Sates: An epidemiologic study. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(3) doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000114816.62331.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National statistics of the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. 2001 URL: http://cecsweb.dartmouth.edu/release1.1/datatools/datatb_s1.php.

- 23.Sharma G, Freeman J, Zhang D, Goodwin JS. Trends in End-of-Life ICU Use Among Older Adults with Advanced Lung Cancer. Chest. 2008 Jan;133(1):72–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dasta JF, McLaughlin TP, Mody SH, Piech CT. Daily cost of an intensive care unit day: the contribution of mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2005 Jun;33(6):1266–71. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000164543.14619.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.The number of cancer deaths is from the National Vital Statistical Reports of 2004 which equals 550,270. URL: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr54/nvsr54_19.pdf.

- 26.Levinsky NG, Yu W, Ash A, Moskowitz M, Gazelle G, Saynina O, Emanuel EJ. Influence of age on Medicare expenditures and Medical care in the last year of life. JAMA. 2001 September 19;286(11) doi: 10.1001/jama.286.11.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barnato AE, Herndon MB, Anthony DL, Gallagher PM, Skinner JS, Bynum JP, Fisher ES. Are regional variations in end-of-life care intensity explained by patient preferences. Med Care. 2007 May;45(5):386–393. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000255248.79308.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fries JF, Koop CE, Beadle CE, et al. Reducing health care costs by reducing the need and demand for medical services. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:321–325. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199307293290506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]