Abstract

Background

Chronically institutionalized patients with schizophrenia have been reported to manifest cognitive and functional decline. Previous studies were limited by the fact that current environment could not be separated from life-time illness course. The present study examined older outpatients who varied in their lifetime history of long-term psychiatric inpatient stay.

Methods

Community dwelling patients with schizophrenia (n=111) and healthy comparison subjects (n=76) were followed up to 45 months and examined two or more times with a neuropsychological (NP) battery and performance-based measures of everyday living skills (UCSD Performance-based skills assessment; UPSA) and social competence. A mixed-effects model repeated-measures method was used to examine changes.

Results

There was a significant effect of institutional stay on the course of the UPSA. When the schizophrenia patients who completed all three assessments were divided on the basis of length of institutional stay and compared to healthy comparison subjects, patients with longer stays worsened on the UPSA and social competence while patients with shorter stays improved. For NP performance, both patient samples worsened slightly while the HC group manifested a practice effect. Reliable change index (RCI) analyses showed that worsening on the UPSA for longer stay patients was definitely nonrandom.

Conclusions

Life-time history of institutional stay was associated with worsening on measures of social and everyday living skills. NP performance in schizophrenia did not evidence the practice effect seen in the HC sample. These data suggest that schizophrenia patients with a history of long institutional stay may worsen even if they are no longer institutionalized.

Cognitive functioning in schizophrenia appears to be stable over the lifespan. When adjusting for normative changes with aging and for demographic factors, little change is seen over time across different follow-up periods in patients of different ages (1). Further, people with schizophrenia show generally similar improvements in performance (i.e., practice effects) with re-testing as healthy individuals (2). There have been some suggestions that there are greater aging-related differences on more demanding “cognitive neuroscience” tests (3–4), but even these differences are minimal compared to the cognitive declines noted in neurodegenerative conditions.

An apparent exception to these findings is older individuals with a history of a chronic course of illness and lengthy institutional stay. Changes in cognitive performance have been detected in this population with follow-up intervals as abbreviated as 18 months (5). Findings of greater cognitive impairment in such populations has been found at different research sites (6–7), arguing against the interpretation that there is something unique about one patient sample. Among these institutionalized samples, poorer baseline performance, lower educational attainment and older age are correlates of risk for cognitive and functional decline (5, 8), as are more severe symptoms of psychosis (9).

Of course it is not possible to determine in institutionalized samples whether characteristics of the environment or the patients that lead to institutionalization are determinants of decline. Only a longitudinal comparison of trajectories of currently ambulatory people with schizophrenia who vary in their history of institutionalization can address the question of environmental influence or patient individual differences. This paper presents the results of such a study.

During the 1990s and early 2000s in the metropolitan New York area, several large state psychiatric facilities were consolidated and many of the patients residing there discharged to community residences or nursing facilities. Concurrently the New York regional Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) initiated an effort to reduce the size of its extensive inpatient facilities. We reported on this process, showing that only current aggression and length of previous institutional stay were predictors of the likelihood of discharge during this downsizing process (10). Many patients were sent to the community and received clinical care at the same facilities where patients with no history of institutional stay were treated.

In the current study, a sample of older (age>50) community dwelling people with schizophrenia were identified and assessed with neuropsychological (NP) tests and performance-based measures of everyday living skills and social competence (referred to as functional capacity [FC]). These patients had a wide-ranging history of previous institutional stay, from 1 to 360 months, and all were seen for their baseline assessment more than 5 years after the longest stay. A sample of healthy individuals with no lifetime history of major mental illness was also examined with the NP and FC assessment. These healthy individuals were selected for a lifetime history of moderate educational and occupational attainment. Reassessments were performed at 18 month intervals.

Thus, this study minimized many of the confounds of previous studies, by including older aged noninstitutionalized samples, avoiding the environmental effects of institutional care, and assessing course in comparison to healthy, generally demographically similar, individuals. This design allowed us to use longitudinal statistical techniques while considering both diagnosis and demographic factors as predictors. Our basic hypotheses were that people with schizophrenia and a history of long institutional stays would be at higher risk for cognitive and functional decline, and that the variables that previously predicted risk for decline in samples of institutionalized patients, including older age (11) and lower educational attainment, would add to the prediction of cognitive and functional decline.

Methods

Participants

Older community dwelling outpatients who met DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder were enrolled in this longitudinal study investigating the course of cognitive and functional status. Exclusion criteria consisted of a primary DSM-IV Axis I diagnosis other than schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, a lifetime history of substance dependence or current substance abuse disorders, Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; 12) score below 18, Wide Range Achievement Test 3rd Edition (WRAT-3;13) reading grade-equivalent of grade 6 or less, or any medical illnesses that might interfere with performance on tests of cognitive functioning. The Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History (CASH; 14) was completed by trained research assistants and diagnosis was confirmed by a senior clinician. Subjects were also required to demonstrate evidence of not having fully recovered at the time of recruitment, as evidenced by meeting at least one of three criteria: 1) an inpatient admission for psychosis in the past two years; 2) an emergency room visit for psychosis in the past two years; or 3) a score on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS;15) positive symptoms items regarding delusions, hallucinations, or conceptual disorganization of 4 (moderate) or more at the time of their baseline assessment.

In the patient group, all subjects were receiving treatment with second-generation antipsychotic medications at each assessment. After the testing procedures were fully explained, all subjects signed a written informed consent form approved by the institutional review board at each research site, where ethical committee approval was obtained.

Healthy comparison subjects were recruited at a “naturally occurring retirement community” in Manhattan. All residents had to be eligible to reside in public housing, which created a population of individuals who were not extraordinarily high functioning over their lifespan. All healthy comparison subjects were screened with the CASH as well and were excluded from participation if they met current or lifetime criteria for major depression or any psychotic condition and met the screening criteria applied to the schizophrenia sample. Healthy control subjects also signed written informed consent approved by the local institutional review board.

Measures

All subjects completed the test battery in a fixed order, with functional skills assessment, a cognitive test battery, and a symptom interview. All interviewers received extensive training in performing all assessments and every three months their performance was evaluated through re-rating of training tapes, dual-ratings of the functional status measures with a senior staff, and quality assurance assessments of all testing.

Performance-based Measures of Functional Capacity

The UCSD Performance-Based Skills Assessment Battery (UPSA; 16) was designed to directly evaluate the ability to perform everyday tasks that are considered necessary for independent functioning in the community. In this study, four derived domains of the UPSA were used: Comprehension/Planning (e.g., organizing outings to the beach or the zoo), Finance (e.g., counting change, and paying bills), Transportation (e.g., using public transportation), and Communication (e.g., using the telephone, rescheduling medication appointments). We excluded the household chores subtest because the analogue kitchen required was not portable enough to be used at field sites. We then re-standardized the scores to a 100-point scale, like the original 5-subtest UPSA, thus allowing comparisons to previous results. This modified version was used in our previous reports with the UPSA (17,18).

The Social Skills Performance Assessment (SSPA; 19) is a social role-play task in which the subject initiates and maintains a conversation in two 3-minute role-play tasks: greeting a new neighbor and calling a landlord to request a repair for a leak that has gone unfixed. These sessions were audiotaped and scored by a trained rater who was unaware of diagnosis (patient or HC) and all other data from the study. These raters were trained to the gold standard ratings of the instrument developers, with an Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) of .86 and high inter-rater reliability was maintained at three months (ICC=.87). The mean of the ratings across the two subtests was the dependent variable.

Cognitive Assessment

Neuropsychological tests were selected to represent diverse cognitive domains that were previously shown to be the most consistently correlated with functional skills (20, 21). These tests included the Wisconsin Card Sorting test (WCST; 22), Trail Making Test Parts A and B (23), learning trials 1–5, long delay recall, and recognition from the Rey Auditory Learning Test (RAVLT;24, ), FAS verbal fluency (24), animal naming (24), and the Digit Span, Letter-Number-Sequencing, and Digit Symbol Coding subtests of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, 3rd edition (25).

All raw scores on the NP tests were converted to age, education, and gender corrected standardized (Z) scores from published norms. These normative corrections were also applied to the performance of the HC sample as well, because this was a sample whose performance was expected to be slightly below the population average.

Procedures

Assessment and Follow-up

Follow-up assessments were scheduled at 18 month intervals after initial entry into the study. Patients and healthy comparison subjects were examined with the same assessments in the same sequence at each subsequent follow-up visit (with the exception of the MMSE and WRAT Reading Recognition, which were only administered at baseline for screening purposes). Alternate test forms were not available for most of the tests, so the same forms were used for all assessments for all participants.

Determination of Institutionalization Status

Length of longest single hospital stay in months was our critical variable in the analyses of institutionalization status. This information was collected from medical records only, because of concerns with the accuracy of self report on the part of patients. This lead to loss of data on 84 schizophrenia patients who resided at a site that did not carry forward their lifetime medical records. As a result, there were 111 patients out of a potential sample of 195 with longitudinal assessment data who constituted the participant sample for this study.

Data Analyses

A mixed-effects model repeated-measures method (26) was used for the first set of analyses which examined the effect of three variables: longest hospitalization, age, and education on the course of NP performance measured with the composite score and the total scores on the UPSA and the SSPA. Since institutionalization is a variable that is only measured in the patients sample we initially examined the covariate effects in the patients sample only. In the mixed-effects models longest hospitalization, age, and education were the fixed factors (covariates) and time was modeled as a random effect. If a significant effect of institutionalization was evident, we aimed to identify a psychometrically meaningful and clinically relevant cutting score that reflected both the distribution of scores in the sample and a clearly lengthy inpatient stay. This score was then used in the next set of analyses

These included a General Linear Model Repeated Measures Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) carried out on the completing cases. The between group factor had 3 levels (HC and two groups of patients: longer stay and shorter stay), and the within-group factor had three time-points (assessments). The repeated-measures ANOVA was done separately for each of the three outcome variables. Significance level was set at p=0.05.

We also computed reliable change indices (RCI). These analyses are designed to determine if changes in performance on the part of individuals exceed the level of change expected by random retest variation and practice effects. Using the RCI plus practice effect model (27–28), we identified the threshold for determination of reliable changes in performance. Specifically, 90% confidence intervals were developed using the standard error of the difference (SEdiff) for each test, which describes the spread of the distribution of change scores that would be expected if no actual change had occurred. The SEdiff was determined for each test using the following formula:

Where x is the first assessment and y is the last The values of SDx and rxy, were determined from the present subsamples, divided by longest hospital stay, using baseline to final observation changes. The practice effect from healthy comparison subjects was used as the “normal” practice effect. Then, a 90% confidence interval for expected retest scores (X2) was determined by multiplying the SEdiff by ± 1.64, using the formula:

Thus, X1 represents the baseline score for each subject, and the mean practice effect equals the mean of the change scores (retest score minus baseline) for subjects in the HC sample. Using this definition, 90% of the retest scores should fall between the lower and upper boundaries (adjusted for practice effects), by chance alone, of this confidence interval and retest scores above and below this boundary are expected to occur less than 5% of the time.

Results

Demographic characteristics of the sample and baseline scores are presented in Table 1. This table presents data only on the individuals who were reassessed at least once and on schizophrenia patients where their longest institutional stay could be documented. The healthy comparison sample was older, slightly more educated, and included a higher proportion of females and Caucasians than the patient sample. Despite the age differences in the samples, HC participants outperformed the patient sample on all three performance based domains at baseline. The average duration of the second follow-up was 41 months (SD=14) for the patient sample and 39 months (SD=8.6) for the healthy controls. We compared the 195 patients with a post-baseline assessment for whom we could (n=111) and could not (n=84) determine their longest hospital stay on baseline scores for the NP assessment, SSPA, and UPSA and changes from the first to last assessment for the three measures. All 6 t-tests were non-significant (all t[194]<1.10, all p>.31.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline performance characteristics of the two samples including only those participants with follow-up data and Data on Longest Hospital Stay

| Schizophrenia Patients | Healthy Controls | |

|---|---|---|

| N | 111 | 76 |

| % Male | 73 | 47 |

| Ethnicity (%) | ||

| Caucasian | 58 | 79 |

| African-American | 33 | 17 |

| Other | 9 | 4 |

| M | SD | M | SD | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 56.99 | 9.00 | 68.01 | 11.18 | 6.33 | .001 |

| Years of Education | 11.86 | 4.42 | 13.19 | 2.19 | 2.59 | .011 |

| UPSA Scaled Score | 75.73 | 17.38 | 86.47 | 7.50 | −6.07 | .001 |

| SSPA Mean Score | 3.89 | 0.74 | 4.59 | 0.35 | −7.78 | .001 |

| Cognitive Composite Score | −1.47 | 0.95 | −0.25 | 0.89 | −9.40 | .001 |

| Illness History Variables | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | Min | Max | Median | |

| Longest Hospital Stay (Months) | 16.12 | 28.61 | 1 | 360 | 6 |

| Number of Hospitalizations | 7.72 | 6.95 | 1 | 36 | 5 |

| Total Lifetime Months in Hospital | 43.62 | 61.40 | 1 | 366 | 20 |

| Age At First Admission | 23.65 | 10.26 | 16 | 45 | 23 |

Longitudinal data was analyzed using a mixed-effects model repeated-measures analysis for the patient sample only. For NP performance in the patient sample, there was no statistically significant effect of time F(2,88)=1.77, p>.25, but there were statistically significant effects of age, [F(1,108)=37.23, p<.001], longest stay, [F(1,108)=4.81, p<.05], and education [F(1,108)=22.11, p<.001]. The time of assessment × longest hospitalization interaction[ F(2,76)=2.06, p>.15] and education × longest hospitalization interaction, [F(2,85)=1.36, p>.25] were not significant.

For UPSA scores in the patient sample, there were statistically significant effects of time [F(2,88)=3.48, p<.035], age, [F(1,108)=30.15, p<.001], longest stay, [F(1,106)=5.63, p<.025], and education [F(1,106)=14.45, p<.001]. The interaction of time of assessment and longest hospitalization, was significant, [F(2,76)=16.95, p<.001], but not the education × longest hospitalization interaction, [F(2,85)=1.31, p>.25]. Thus, older age and lower education had adverse relationships on UPSA scores, while longer institutional stays predicted greater worsening.

For SSPA scores in the patient sample, there were statistically significant effects of time [F(2,80)=10.79, p<.001], age, [F(1,106)=11.37, p<.001], trend level effects for longest stay, [F(1,106)=3.91, p<.07], and a trend level effect of education [F(1,106)=3.76, p<.055]. The interaction of time of assessment and longest hospitalization was not significant, [F(2,69)=1.43, p=.23]. There was, however, a significant interaction of education × time of assessment,[ F(2,82)=8.45, p<.001]. Thus, for SSPA scores, there was significant worsening over time and lower educational attainment predicted greater worsening over time.

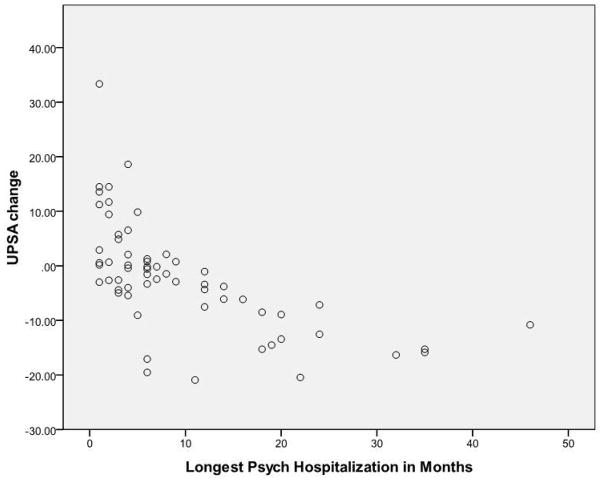

Figure 1 presents a scatterplot for the association between changes from the first to last assessment on the UPSA and length of stay in the schizophrenia patients who completed the study. As noted in the figure, two outliers are trimmed from the graph in order to simplify the presentation.

Figure 1. Scatterplot of Change Scores on the UCSD Performance-Based Skills assessment as a function of longest institutional Stay in Months.

Note. Two outliers for length of stay are not presented. Case with a 120 month stay had a 12 point worsening. Case with a 360 month stay worsened by 21 points

As the first set of analyses demonstrated an effect of length of stay on the course of several elements of functional performance, we split the patients sample by the median length of stay, which was 6 months or longer vs. less than 6 months (see table 1). The means and standard deviations from each assessment for the UPSA, SSPA and NP measures in the analysis of schizophrenia cases with short or long stay and healthy controls who completed all three assessments are presented in Table 2. In order to ensure that this analysis was not being biased by attrition, we compared the baseline scores in the healthy and schizophrenia patients who were seen for one vs. both of the follow-ups on the UPSA, SSPA, and NP assessment. None of these t-tests was significant (all t<1.12, all p values>.26).

Table 2.

Scores on the Performance Based Measures for Participants who Completed All Three Assessments

| UPSA Scores | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | ||||||

| Longer Stay Patients N=35 | Shorter Stay Patients N=26 | Healthy Controls N=53 | ||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Baseline | 74.38 | 20.77 | 78.33 | 15.93 | 85.80 | 7.62 |

| First Reassessment | 70.04 | 15.54 | 78.84 | 11.13 | 87.61 | 6.57 |

| Second Reassessment | 65.16 | 18.69 | 82.14 | 12.91 | 86.43 | 6.99 |

| Effect Size First to Last Assessment (d) | 0.45 | (−) | 0.24 | (+) | 0.08 | (+) |

| SSPA Scores | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | ||||||

| Longer Stay Patients N=35 | Shorter Stay Patients N=26 | Healthy Controls N=53 | ||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Baseline | 3.81 | 0.69 | 4.04 | 0.70 | 4.56 | 0.38 |

| First Reassessment | 3.71 | 0.71 | 4.25 | 0.54 | 4.63 | 0.41 |

| Second Reassessment | 3.57 | 0.79 | 4.10 | 0.67 | 4.67 | 0.33 |

| Effect Size First to Last Assessment (d) | 0.35 | (−) | 0.09 | (+) | 0.29 | (+) |

| Neuropsychological Performance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | ||||||

| Longer Stay Patients N=35 | Shorter Stay Patients N=26 | Healthy Controls N=53 | ||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Baseline | −1.47 | 0.91 | −1.29 | 0.91 | −0.14 | 0.77 |

| First Reassessment | −1.43 | 0.94 | −1.36 | 0.90 | 0.09 | 0.70 |

| Second Reassessment | −1.60 | 0.99 | −1.38 | 0.99 | 0.13 | 0.70 |

| Effect Size First to Last Assessment (d) | 0.14 | (−) | 0.11 | (−) | 0.35 | (+) |

For UPSA scores in the completers, we found a significant group × time interaction, [F(4,220)=22.76, p<.001]. This interaction reflected moderate worsening on the part of the longer-stay institutionalized patients, minimal improvements on the part of short-stay institutionalized patients, and no changes in the HC sample. Tukey follow-up tests indicated that all three groups differed significantly from each other, with significantly greater practice effects for shorter stay patients than the HC sample. SSPA performance also was associated with a significant group × time interaction, [F(4,220)=4.90, p<.025]. This interaction reflected improvement on the part of the HC sample and the shorter-stay patients combined with modest worsening on the part of the longer-stay group. Tukey follow-up tests found that longer stay patients worsened more than the other two groups, who did not differ. NP performance was associated with a statistically significant group × time interaction [(F(4,220)= 6.18, p<001]. This interaction reflected improvements on the part of the HC sample and minimal changes for both of the two patient samples. Tukey follow-up tests found that the HC sample manifested a larger improvement with re-testing than the two patient samples, who did not differ.

Because statistically significant changes in performance were detected for some of the measures, we identified the test-retest stability of these measures from 1 to 2nd, 2nd to 3rd, and 1st to 3rd assessments. These correlations for each group are presented in table 3. All of the correlations were statistically significant at p<.05. Using the procedures described above, we applied the RCI to changes in NP scores, SSPA scores, and UPSA scores for the longer and shorter stay schizophrenia patients. We found that for NP performance there were no differences across long stay and short stay patients in terms of worsening vs improving, χ2 (1)=0.67. However, for the SSPA, 11 long stay patients worsened and 7 improved, while 2 short stay patients worsened and 6 improved, χ2 (1)=4.51, p<.05. Greater reliable changes were seen for UPSA scores, where 12 long-stay patients worsened and none improved and 15 short-stay patients improved and none-worsened, χ2 (1)=24.02, p<.001.

Table 3.

Test-Retest Stability and Reliable Change Intervals For The Participant groups including all participants who completed the Assessments at those time periods

| Participant Sample Group | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Longer Stay Patients | Shorter Stay Patients | Healthy Controls | |||||

| UPSA Scores | |||||||

| Retest Correlations | Period | r | n | r | n | r | n |

| 1–2 | .84 | 63 | .75 | 48 | .52 | 71 | |

| 2–3 | .85 | 35 | .74 | 26 | .41 | 53 | |

| 1–3 | .90 | 35 | .84 | 26 | .53 | 53 | |

| 90 % RCI | 15.11 | 14.10 | |||||

| SSPA Scores | |||||||

| Retest Correlations | |||||||

| 1–2 | .79 | 63 | .54 | 48 | .53 | 71 | |

| 2–3 | .88 | 35 | .64 | 26 | .52 | 53 | |

| 1–3 | .84 | 35 | .78 | 26 | .56 | 53 | |

| 90% RCI | 0.43 | 0.56 | |||||

| NP Performance | |||||||

| Retest Correlations | |||||||

| 1–2 | .78 | 63 | .76 | 48 | .86 | 71 | |

| 2–3 | .94 | 35 | .95 | 26 | .87 | 53 | |

| 1–3 | .77 | 35 | .82 | 26 | .76 | 53 | |

| 90 % RCI | 0.91 | 0.84 | |||||

In a final analysis aimed at determining whether UPSA scores were being affected by level of residential independence and opportunities to perform skills, we classified the residential status of the 111 into three groups, independent and financially responsible (n=44; 40%), independent but not financially responsible (n=25; 23%), and not financially responsible (n=42;37%). We then regressed residential status onto changes in UPSA scores from the first to last assessment, finding that there was a significant association between the two variables, F(1,109)=14.84, p<.001, R2=.11. We then entered longest psychiatric hospitalization into the equation first, finding a strong relationship between longest hospitalization and decline in UPSA scores, F(1,109)=27.96, p<.001, R2=.31. When we entered residential status as the second block in the equation, it failed to enter the equation, F(1,108)=.13, p=.74. Thus, residential status failed to account for variance in functional decline when longest inpatient stay was considered.

Discussion

These results suggest that people with schizophrenia with a history of lengthy institutional stay show evidence of differential declines in the ability to perform everyday living skills over a 3 to 4 year follow-up period. The declines in the longer-stay patients are subtle and would not have been notable without the reference points of the improvements in the non-institutionalized patients. Neuropsychological test performance did not decline, but the patients did not show a practice effect, which was detected in the healthy comparison subjects. This lack of practice effect may truly reflect worsening in performance relative to healthy standards. The results of mixed model analyses were also generally replicated in the repeated-measures analyses including all cases and by the analyses of the reliable change indices that we calculated. Age and education exerted adverse effects on cognitive and functional performance that did not interact with history of institutional stay. The test-retest correlations for the variables of interest were not different in the samples of people with schizophrenia who were quite different in their longest institutional stay.

There are some limitations of this study. We had to exclude a number of patients because we could not determine their length of institutional stay, because there was not clear enough information in records. We cannot determine how being able to include those patients would have affected the results, but at least they did not differ at baseline from the group whose stay could be ascertained. The sample size at follow-up was reduced because of attrition. However, the results of the analyses of the completers, with a smaller sample size, were very similar to the MMRM analyses with a larger sample. An exception is the SSPA data, for which we found worsening in the institutionalized patients which was confirmed with RCI analyses. The formerly institutionalized patients may not be completely representative of chronically institutionalized cases, because they left the hospital at some point. There are many other patients who were either never discharged from long term psychiatric hospital care or referred directly to a nursing home. Those patients are likely to be more disabled at baseline and, further, to manifest much more severe psychotic symptoms than the current sample. Finally, performance-based measures of disability may not overlap completely with real-world functional outcomes.

Given the early stage of development of these performance-based assessments, there is no valid way to infer the clinical meaning of these changes. Interestingly, cognitive performance did not show evidence of either decline on the part of previously institutionalized patients or improvement on the part of individuals with no such history. The lack of decline may be consistent with previous findings of slightly reduced sensitivity to cross-sectional age effects for clinical NP tests compared to experimental neuroscience measures (3). Truncated practice effects are consistent with the results of several studies of older people with schizophrenia (27), although this issue clearly requires more attention. It does appear that changes in the ability to perform everyday living and social skills are detectable in this population, but we were unable to correlate cognitive and functional changes because of the minimal changes over time in NP performance.

There are several potential neurobiological mechanisms of this decline, although none were measured in this study. These include different rates of change in cortical gray matter volume; several previous reports have shown more rapid decline in individuals with long-term institutionalization and disability compared to similar-aged people with schizophrenia without lengthy institutional stay (29). Recent data have suggested that changes in the volume of elements of the basal ganglia and the corpus callosum are greater in fully disabled patients than in individuals who were higher functioning (30–31). Poor outcome is associated with reductions in fractional anisotropy of the white matter tracts in the brain as well (32). The biological markers or indicators of functional decline remain a very intriguing question.

It is also possible that the declines observed in functional capacity are reduced opportunities. In our analyses, residential status did not predict functional declines when longest institutional stay is considered. While lengthy institutional stay may be associated with placement in a more restricted setting after discharge, the setting itself in this study does not predict additional functional decline. These data suggest that interventions aimed at reduction of disability and promotion of independent living skills, through cognitive remediation or psychosocial treatments, may benefit this increasing population of older individuals with schizophrenia who have experienced long histories of institutionalized care.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by NIMH grant number RO1MH63116 to Dr. Harvey. During the past year Dr. Harvey has served as a consultant for Eli Lilly and Company, Merck and Company, Shire Pharma, Johnson and Johnson, and Dainippon Sumitomo America. He has current grant support from Astra-Zeneca. Dr. Bowie has grant support from Johnson and Johnson. Dr. Reichenberg received speaker honoraria from Astra-Zeneca (Greece). All other authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Philip D. Harvey, Department of Psychiatry, Emory University School of Medicine.

Abraham Reichenberg, Department of Psychological Medicine, Institute of Psychiatry, London.

Christopher R. Bowie, Departments of Psychology and Psychiatry, Queens University, Canada.

Thomas L. Patterson, Department of Psychiatry, UCSD Medical Center.

Robert K. Heaton, Department of Psychiatry, UCSD Medical Center.

References

- 1.Heaton RK, Gladsjo JA, Palmer BW, Kuck J, Marcotte TD, Jeste DV. Stability and course of neuropsychological deficits in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:24–32. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldberg TE, Goldman RS, Burdick KE, Malhotra AM, Lencz T, Patel RC, et al. Cognitive improvements after treatment with second-generation antipsychotic medications in first episode schizophrenia: Is it a practice effect? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:1115–1122. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowie CR, Reichenberg A, McClure MM, Harvey PD. Age-Associated Differences in Cognitive Performance in Older Community Dwelling Schizophrenia Patients: Differential Sensitivity of Neuropsychological and Information Processing Tests? Schizophr Res. 2008;106:50–58. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Granholm E, Morris S, Asarnow RF, Chock D, Jeste DV. Accelerated age-related decline in processing resources in schizophrenia: evidence from pupillary responses recorded during the span of apprehension task. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2000;6:30–43. doi: 10.1017/s1355617700611049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harvey PD, Silverman JM, Mohs RC, Parrella M, White L, Powchik P, et al. Cognitive decline in late-life schizophrenia: a longitudinal study of geriatric chronically hospitalized patients. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45:32–40. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00273-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arnold SE, Gur RE, Shapiro RM, Fisher KR, Moberg PJ, Gibney MR, et al. Prospective clinicopathological studies of schizophrenia: Accrual and assessment of patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:731–737. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.5.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bartels SJ, Mueser KT, Miles KM. A comparative study of elderly patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in nursing homes and the community. Schizophr Res. 1997;27:181–190. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(97)00080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harvey PD, Davidson M. Schizophrenia: Course over the lifetime. In: Davis KL, et al., editors. Neuropsychopharmacology: Fifth generation of progress. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harvey PD, Bertisch H, Friedman JI, Marcus S, Parrella M, White L, et al. The course of functional decline in geriatric patients with schizophrenia: cognitive, functional, and clinical symptoms as determinants of change. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11:610–619. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.11.6.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.White L, Parrella M, McCrystal-Simon J, Harvey PD, Masiar S, Davidson M. Characteristics of elderly psychiatric patients retained in a state hospital during downsizing: A prospective study with replication. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1997;12:474–480. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1166(199704)12:4<474::aid-gps530>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedman J, Harvey PD, Coleman T, Moriarty PJ, Bowie C, Parrella M, White L, et al. A Six Year Follow-up Study of Cognitive and Functional Status Across the Life-span in Schizophrenia: A Comparison with Alzheimer’s Disease And Healthy Subjects. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1441–1448. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.9.1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-Mental State: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilkinson GS. The Wide Range Achievement Test. Wilmington, DE: Wide Range, Inc; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andreasen NC, Flaum M, Arndt S. The comprehensive assessment of symptoms and history (CASH): An instrument for assessing psychopathology and diagnosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:615–623. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080023004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kay SR. Positive and negative syndromes in schizophrenia. New York: Brunner/Mazel; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patterson TL, Goldman S, McKibbin CL, Hughs T, Jeste DV. UCSD Performance-Based Skills Assessment: development of a new measure of everyday functioning for severely mentally ill adults. Schizophr Bull. 2001;27:235–245. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McClure MM, Bowie CR, Patterson TL, Heaton RK, Weaver C, Anderson H, et al. Correlations of functional capacity and neuropsychological performance in older patients with schizophrenia: evidence for specificity of relationships? Schizophr Res. 2007;89:330–338. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bowie CR, Reichenberg A, Patterson TL, Heaton RK, Harvey PD. Determinants of real-world functional performance in schizophrenia subjects: correlations with cognition, functional capacity, and symptoms. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:418–425. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patterson TL, Moscona S, McKibbin CL, Davidson K, Jeste DV. Social skills performance assessment among older patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2001;48:351–360. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(00)00109-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Green MF, Kern RS, Braff DL, Mintz J. Neurocognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia: Are we measuring the “right stuff? Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2000;26:119–136. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harvey PD, Moriarty PJ, Friedman JI, Parrella M, White L, Mohs RC, et al. Differential Preservation of Cognitive Functions in Geriatric Patients with Lifelong Chronic Schizophrenia: Less Impairment in Reading Scores Compared to Other Skill Areas. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47:962–968. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00245-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heaton RK, Chellune CJ, Talley JL, Kay GG, Curtiss G. Wisconsin Card Sorting Test Manual-Revised and expanded. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reitan RM, Wolfson D. The Halstead-Reitan neuropsychological test battery: Theory and clinical interpretation. 2. Tucson, AZ: Neuropsychology Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spreen O, Strauss E. A compendium of neuropsychological tests and norms. 2. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Psychological Corporation. WAIS-III and WMS-III Technical Manual. San Antonio, TX: Author; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gibbons RD. Mixed-effects models for mental health services research. Health Services Outcomes Research Methodology. 2000;1:91–129. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harvey PD, Palmer BW, Heaton RK, Mohamed S, Kennedy J, Brickman A. Stability of cognitive performance in older patients with schizophrenia: An 8-week test-retest study. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:110–117. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heaton RK, Temkin N, Dikmen S, Avitable N, Taylor MJ, Marcotte TD, Grant I. Detecting change: A comparison of three neuropsychological methods, using normal and clinical samples. Arch Clin Neuropsychology. 2001;16:75–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davis KL, Buchsbaum MS, Shihabuddin L, Spiegel-Cohen J, Metzger M, Frecska E, et al. Ventricular enlargement in poor outcome schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry. 1998;43:783–793. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(97)00553-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mitelman SA, Nikiforova YK, Canfield EL, Hazlett EA, Brickman AM, Shihabuddin L, et al. Poor outcome in chronic schizophrenia is associated with progressive loss of volume of the putamen. Schizophr Res. 2009;113:241–245. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mitelman SA, Nikiforova YK, Canfield EL, Hazlett EA, Brickman AM, Shihabuddin L, et al. A longitudinal study of the corpus callosum in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2009;114:144–153. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mitelman SA, Newmark RE, Torosjan Y, Chu KW, Brickman AM, Haznedar MM, et al. White matter fractional anisotropy and outcome in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2006;87:138–59. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]