Abstract

Limited research has captured the wide varieties of distinct, but interrelated, life stressors that young men who have sex with men (YMSM) experience as emerging adults. We examined the way recent experiences of a diverse set of stressors predict illicit drug use, alcohol misuse, and inconsistent condom use (i.e., unprotected anal intercourse) among an ethnically diverse cohort of YMSM (N=526). Results indicated that stress related to financial and health concerns were associated with increased risk for substance use, while health concerns and partner-related stress were associated with sexual risk-taking. Additional analyses indicated drug use and alcohol misuse did not significantly mediate the impact that stressors have on sexual risk. Findings show that stressors from different life domains can have impact on different HIV-risk behavior. Results challenge the way diverse stressful life experiences are conceptualized for this population.

Introduction

Gay and bisexual men between the ages of 18 and 25 are among the fastest growing segment of the population affected by the HIV/AIDS epidemic (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008). While emerging adulthood can be a time filled with possibilities, it is also a critical period as young adults strive to develop a positive adult identity, which is a primary developmental task for all adolescents (Arnett & Tanner, 2006). In addition to navigating this often difficult process, young men who have sex with men (YMSM) may face additional challenges as they struggle to define who they are sexually (Harper, 2007; Savin-Williams, 1994, 1998). Research indicates that lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) individuals often experience additional stress that stems from prejudice and discrimination encountered in their daily lives, as compared to their heterosexual counterparts (Meyer, 2003; Wolitski, Stall, & Valdiserri, 2008). The additional stressful experiences can contribute to increased psychological, social, and health problems, including drug use, alcohol misuse, anxiety disorders, and depression, as shown in population-based studies comparing LGB and non-LGB groups (Balsam, Rothblum, & Beauchaine, 2005; S. D. Cochran & Mays, 2006; S. D. Cochran, Sullivan, & Mays, 2003; Mays & Cochran, 2001; Mills et al., 2004; Remafedi, 2008).

In their journey to adulthood, YMSM contend with stressors from multiple life domains (e.g., family, work, relationship). While sexual identity stress may permeate throughout these different life contexts, emerging adult YMSM also face challenges that may not be a result of sexual identity (e.g., ending of relationships). Building upon previous critical work that utilized multidimensional conceptualizations of sexual identity-related or gay-related stress among young MSM (Rosario, Schrimshaw, Hunter, & Gwadz, 2002; Rotheram-Borus, Rosario, Van Rossem, Reid, & Gillis, 1995), the current study proposes a framework that incorporates stressors from life domains most relevant for YMSM, in addition to those related to sexual identity. This presents YMSM not only as individuals dealing with stressors associated with their sexual identity, but as emerging adults facing many interrelated life challenges (Meyer, Schwartz, & Frost, in press; Savin-Williams, 2001).

Previous research among LGB youth has shown that gay-related stress (e.g., homophobic discrimination, victimization/harassment, internalized homophobia, and discomfort associated with disclosure of sexual identity) to be significantly associated with adverse mental health outcomes (D'Augelli, Grossman, & Starks, 2006; Hershberger & D'Augelli, 1995; Rosario, Schrimshaw, & Hunter, 2004; Rotheram-Borus, Hunter, & Rosario, 1994). Evidence also suggests that these stressors are linked to increased substance use (DuRant, Krowchuk, & Sinai, 1998; Jordan, 2000; Rosario, Hunter, & Gwadz, 1997) and sexual risk-taking (Garofalo, Wolf, Kessel, Palfrey, & DuRant, 1998) among this population. In addition to sexual identity-related stress, the present study examines stress that occurs in different life contexts particularly relevant for emerging adult YMSM, including family relationships, peer acceptance, school/work environment, romantic relationships, health, and residential/financial stability. The following reviews recent findings and discusses how these interrelated stressors from various life domains may affect YMSM.

As emerging adults, YMSM may face increased conflict within their families as they begin to renegotiate/redefine these relationships. This conflict often results in physical or verbal victimization, particularly when they begin to disclose their sexual identity status (D'Augelli, 2005; Huebner, Rebchook, & Kegeles, 2004; Rivers, 2000; Willoughby, Malik, & Lindahl, 2006). A recent study found that LGB young adults (ages between 21 to 25) who experienced greater family rejection not only have increased odds of suicide attempts and depression, but are also significantly more likely to use drugs and engage in unprotected sexual intercourse (Ryan, Huebner, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2009). In addition, young adults who are coming to terms with their sexual identity often report stress associated with peer acceptance and discrimination within their school and work environments. LGB youth such as YMSM are often subjected to verbal and physical harassment from their peers (Henning-Stout, James, & Macintosh, 2000). This lack of acceptance has been shown to adversely impact them socially and psychologically, including their academic performance (Roffman, 2000).

Data from national studies consistently demonstrate that sexual minority youth in US schools frequently encounter anti-gay slurs, harassment, or physical violence (Hatred in the hallways: Violence and discrimination against lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender students in U.S schools, 2001; Kosciw & Diaz, 2006). In a representative national sample of rural high school students, LGB youth report lower levels of school belonging, perhaps as a result of such experiences (Rostosky, Owens, Zimmerman, & Riggle, 2003). While few studies have examined work-related stress among LGB youth, those that do examine work-related stress among LGB adults have focused on issues related to sexual identity disclosure in the workplace. While disclosure can have serious consequences in the workplace (e.g., harassment and termination) (D'Augelli & Grossman, 2001), recent findings suggest that the fear of being discovered, or “outed”, may be even more distressing than actual discrimination (Ragins & Cornwell, 2001; Ragins, Singh, & Cornwell, 2007). This issue could be particularly pertinent for emerging adult YMSM entering the workforce who may be challenged with greater pressure to perform.

Romantic relationships can take on great importance in the lives of emerging adult YMSM. In fact, research suggests that LGB youth experience considerable stress around romantic relationships. They report lower levels of control in relationships than heterosexual youth (Diamond & Lucas, 2004) and high levels of dependence on partners for social support and information about sexual health, which in turn may result in receiving insufficient support from family or peers (Diamond, 2003). Similar to findings among heterosexual emerging adults (Feldman & Cauffman, 1999), many YMSM also report stress related to sexual infidelity in relationships, which may lead to break-ups and temporarily lowered self-esteem (Eyre, Milbrath, & Peacock, 2007).

Health concerns can be a source of stress for individuals in any age group or sexual orientation. However because of high rates of HIV, YMSM may face additional stress or anxiety about the potential for infection. Our own research indicates that while many physical health indicators of YMSM are comparable to a national sample of same-aged non-YMSM youth, with regard to diet, weight, physical activity, and obesity, HIV stands out as the most prominent health risk and source of stress facing these youth (Kipke, Kubicek et al., 2007). Little research has considered the impact of stress surrounding concerns about ones' health and friends' among YMSM.

As with other emerging adults, concerns about financial stability can be very stressful for YMSM, particularly because they often face reduced levels of support from family, and may even be forced out of their homes after disclosing their sexual identity status (Savin-Williams, 2000). LGB individuals are more likely than heterosexual youth to leave home during adolescence, and the most common reason reported for doing so is conflict with family members (B. N. Cochran, Stewart, Ginzler, & Cauce, 2002). Although the psychosocial impact of financial or residential stress has been the subject of limited research in this population, our findings indicate that YMSM with an unstable residential status due to being forced out of their home, are significantly more likely to engage in HIV-risk behaviors (Kipke, Weiss, & Wong, 2007).

Current study

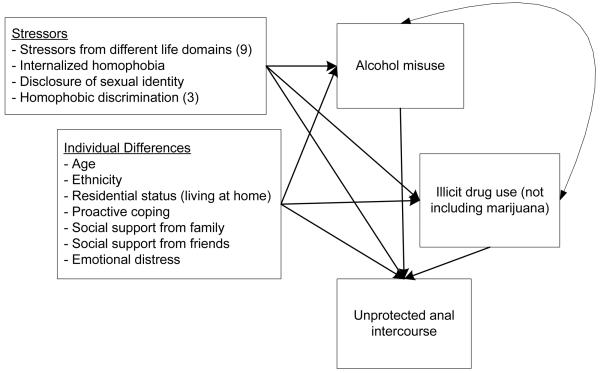

Even though many of the experiences described can be linked to one's sexual identity, non-sexual identity-related stressors are also present in the lives of YMSM. For example, despite the way sexual identity status could impact both academic and work performance, the extent to which these school/work-related stressors (e.g., failed a test or being demoted) affect YMSM and their risk-behaviors is largely unknown. Given our incomplete understanding of the complex stressful life contexts that these young men face and the extent to which various stressful experiences significantly contribute to sexual risk-taking, additional research that investigates these relationships can offer valuable insights. Based on Problem Behavior Theory, which postulates that behaviors are the result of person-environment interactions (Jessor, 1991) and the theoretical and empirical work reviewed, we devised a conceptual model (see Figure 1) that considers stressors encountered by YMSM, individual differences in socio-demographic (e.g., ethnicity, age) and psychosocial factors (e.g., family and peer support) and their links to HIV-risk behaviors, including illicit drug use, alcohol misuse, and inconsistent condom use. As an association between substance use and sexual risk-taking has often been observed (Koblin et al., 2003; Rotheram-Borus et al., 1995; Stall & Purcell, 2000), we further specified that the relationship between stress and sexual risk-taking is mediated, at least in part, by substance use.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model Linking Stressors and Individual Differences Variables to Substance Use and Unprotected Anal Intercourse

Using the baseline data from a longitudinal study (Healthy Young Men Study) conducted with an ethnically diverse cohort of YMSM in Los Angeles (N=526), this paper addresses the following questions: 1) what are common types of life stressors YMSM face; 2) how are these stressors associated with each other and with emotional distress; 3) to what extent do different types of stressors and individual-level risk and protective factors affect involvement in substance use and inconsistent condom use among YMSM, after controlling for effects associated with distress; and finally 4) whether illicit drug use and alcohol misuse are significant mediators between stressors and sexual risk-taking. We expect that regardless of types of stressors experienced, each would be significantly associated with emotional distress. As it is well-established that different stressors can have disparate impact on health and well-being (Bolger, DeLongis, Kessler, & Schilling, 1989), we suspect that different types of stressors could have distinct impact on each of the risk behaviors examined. Moreover, as noted above, based on previous findings of the significant association between substance use and sexual risk-taking, we suspect that substance use would significantly mediates the association between stress and sexual risk-taking in the current study.

Method

Participants

A total of 526 subjects were recruited into the Healthy Young Men's Study (HYM). The HYM study utilized quantitative and qualitative methods to explore individual, familial, interpersonal, and community factors that may influence drug use, HIV risk, and mental health. Young men were eligible to participate in the study if they were: a) 18 to 24 years old; b) self-identified as gay, bisexual, or uncertain about their sexual orientation and/or reported having had sex with a man; c) a resident of Los Angeles County and anticipated living in Los Angeles for at least six months; and d) self-identified as Caucasian, African American, or Latino of Mexican descent. As few studies have systematically examined racial/ethnic differences within the YMSM population, we stratified the sample to make such comparisons. Furthermore, we limited our Latino cohort to Latinos of Mexican descent to avoid inappropriately attributing study findings to a heterogeneous and diverse group of Latino YMSM.

Procedures

YMSM were recruited at public venues using the stratified probability sampling design developed by the Young Men's Study (MacKellar, Valleroy, Karon, Lemp, & Janssen, 1996) and later modified by the Community Intervention Trials for Youth (Muhib et al., 2001). Study participants were recruited from 36 different public venues that had previously been identified as settings where YMSM spend time, including bars/clubs (50%); Pride Festivals (14%); special events/private parties (14%); social service agencies (11%) and high-traffic street locations (11%). (For more information on sampling procedures please see Ford et al. (in press)).

Measures

The survey was administered in both English and Spanish using computer-assisted interview (CAI) technologies and an online testing format. CAI technologies have increasingly been found to improve both the quality of collected data and the validity of subjects' responses, particularly to questions of a sensitive nature, such as drug use and sexual behavior (Kissinger et al., 1999; Radloff, 1977; Ross, Tikkanen, & Mansoon, 2000; Turner et al., 1998). The CAI software used in this study incorporated sound files that allowed participants to either read questions on the computer screen or listen to the questions read through headphones and enter their responses directly into the computer. Participants completed a survey that required about 1 1/2 hours to complete and were compensated with $35 for their time and effort. Analyses were conducted with the following variables:

Individual Differences in Demographic and Psychosocial Characteristics

Demographic variables

Participants reported on a variety of demographic information including age, race/ethnicity, and current residential status (e.g., living with family or not).

Social support

The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet, & Farley, 1988) is a 12-item scale that measures perceived support from family and friends. A mean score of the items for each subscale was calculated. Cronbach's alpha was .87 for the family support subscale and .85 for friends' support.

Proactive coping

Proactive coping was measured by the Proactive Coping Scale, a part of the Proactive Coping Inventory (Greenglass, Schwarzer, Jakubiec, Fiksenbaum, & Taubert, 1999). This 14-item scale taps into individuals' ability to engage in autonomous goal setting with self-regulatory cognitions and behavior (α=.79). Responses are typically summed, with a higher score indicating greater proactive coping.

Emotional Distress/Depression

Emotional distress or depression was measured using the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale (Radloff, 1977) whereby participants were asked to report whether they had experienced depressive symptoms within the past week (α=.90). The sum score was used.

Stressors

Stressful life events

Stressful life events were measured by asking participants if they had experienced stressful events during the previous 3 months using a 35-item instrument that was developed with an adult MSM population (Nott & Vedhara, 1995). In addition to using items from the established scale, the scale was adapted for YMSM by adding 8 items that were generated from qualitative data during the formative phase of the study (α=.76). Formative phase interviews were designed to contextualize and refine key constructs to be further examined in the main phase of the Healthy Young Men's Study1. Respondents were asked to describe the two most stressful events (determined by the respondents) that had occurred in their families. The most frequently reported types of stressful events were then added to the scale.

Items are typically summed for this measure to create a summary score. However, because of the interest in whether these events can be meaningfully distinguished, an exploratory factor analysis was performed on this adapted scale. We evaluated the integrity and structure of this scale using Mplus (v. 5.02; Muthén and Muthén, 2008). Results informed the development of nine conceptually distinct subscales, which include: family-related stress (e.g., family has financial troubles, violence in the family), partner-related stress (e.g., arguments with partner, relationship with partner ended), death-related stress (e.g., partner or a close friend/relative died), school/work related stress (e.g., failed an exam, demoted), others' health stress (e.g., a close friend/relative has serious illness), self-health stress (e.g., you felt your own health is deteriorating; you thought you were HIV-positive), finance-related stress (e.g., financial problems, residential instability, credit card debt), physical/emotional threat stress (e.g., harassed or verbally threatened, problems with police), and peer non-acceptance of sexuality (e.g., trouble with your classmate over your sexual orientation, losing a close friend because of sexual orientation). Because no one reported that a partner had passed away, a single item represents the death stress subscale. This resulted in nine dichotomized variables that reflected whether or not individuals recently experienced any of these stressors.

Internalized homophobia

Ross and Rosser's (Ross & Simon Rosser, 1996) 26-item instrument measured internalized homophobia (α=.74). Respondents responded to these items in a 4-point, Likert-type scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. A mean score of the responses was computed.

Disclosure of sexuality

Participants were asked how many of their family, best/closest friends, and other friends know about their sexual identity, attractions, or behavior, here referred to as “out to friends and family”. Mean scores were calculated from responses to this 6-item measure with a 4-point scale that ranged from “none” to “all”. A greater score indicated more people were aware of participants' sexuality (α=0.85).

Homophobic discrimination

Experiences of homophobic discrimination were measured using a scale developed by Diaz (Díaz, Ayala, Bein, Henne, & Marin, 2001). These scales measure instances of rejection and verbal harassment associated with participants' sexual orientation and/or gender nonconformity using a 4-item response format (1= never, 2 = once or twice, 3 = a few times and 4 = many times; α=.72). Three subscales were identified: 1) experiences of homophobia when growing up (e.g., hearing that homosexuals are sinners and will go to hell); 2) evading or managing sexual identity to avoid negative consequences (e.g., moving away from friends and family); and 3) extreme form of homophobic discrimination (e.g., losing a job or career for being a homosexual).

HIV-Risk Outcomes

Drug use

Participants were asked if they had in the last 3 months used a variety of illicit drugs, including crack, cocaine, crystal/methamphetamine, ecstasy, poppers, GHB, Ketamine, and “other forms of speed”, LSD, PCP, heroin, mushrooms, and prescription drugs without a physician's order (i.e., anti-anxiety, depressants, anti-depressant/sedatives, opiate/narcotics, and attention deficit disorder medications). We elected to separate alcohol and marijuana from inclusion in the illicit drug use category given that both substances are readily available and commonly used within the general population of adolescents and young adults. A dichotomous variable of drug use represents the use of at least one of the drugs mentioned.

Alcohol use/misuse

Participants were asked about their lifetime, past 3-month, past 30-day use of alcohol, and on average the number of drinks they consume in one sitting. Heavy and frequent use were classified using criteria from previous research conducted with young adults (Presley & Pimental, 2006), whereby frequent use was defined as alcohol use for 3 or more days during the past week, and binge drinking was defined as 5 or more drinks within a single setting in the past week (McNall & Remafedi, 1999). In creating a dichotomous outcome variable for alcohol misuse, those considered frequent and/or binge users were grouped into the alcohol misuse group (Wong, Kipke, & Weiss, 2008).

Inconsistent Condom Use (i.e., unprotected anal intercourse)

Respondents were asked about their sexual activity during the past 3 months if they had engaged in anal insertive and/or receptive sex, and the extent to which they had used a condom during these times. A dichotomous variable represents inconsistent condom use in the last 3 months during any anal intercourse. While we also collected data on participants' condom use with sero-concordant primary partners, it represents only 10% of the sample, and given the transient nature of primary partner relationships at this age, we decided to not draw a distinction between inconsistent condom use with primary partners and non-primary partners.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive and correlation analyses examined the distribution of stressful life events by domains and the way stressors and emotional distress are associated with each other. Next, a series of hierarchical logistic regression models examined how stressors were associated with each HIV-risk related outcome after accounting for effects of statistically significant variables from the previous step. Following procedures described by Baron and Kenny (1986), MacKinnon and Dwyer (1993), and more recently, Shrout and Bolger (2002) on investigating mediated relationships with dichotomous outcomes, we evaluated a partially mediated model (where direct and indirect paths are specified) using weighted least squares-mean and variance adjusted (WLSMV) estimation. Model fit was determined based on the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and the comparative fit index (CFI). A value that is less than or equal to .05 for RMSEA and values greater than or equal to .95 for the TLI and CFI suggest good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Finally, given the non-normal distribution of dichotomous mediators and outcome variables, we used bias-corrected bootstrap tests to estimate and test direct and indirect effects of our mediated model instead of the Sobel test in order to increase power (Fritz & MacKinnon, 2007; Shrout & Bolger, 2002).

Results

Descriptive findings

As shown in Table 1, our sample included 195 (37%) Caucasian, 126 (24%) African American, and 205 (39%) Latinos of Mexican descent. The average age was 20.1 years (SD=1.58), with about 40% of the sample being 18-19 years of age. Among participants who were of Mexican descent, 30% had been born outside of the US. Over half of the sample was still living at home. Descriptive analyses revealed that family stress experience (75%) was the most common, followed by work- or school-related stress (73%). In addition, many youth reported stress related to personal financial difficulties (68%), which included credit card debt and residential instability. Also common was stress associated with romantic partners (61%).

Table 1.

Description of the Study Sample (N=526)

| Variables | Categories | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity | African-American | 126 (24) |

| Mexican descent | 205 (39) | |

| Caucasian | 195 (37) | |

| Age | 18 - 19 yrs | 206 (39) |

| 20 - 21 yrs | 196 (37) | |

| 22+ yrs | 124 (24) | |

| Immigration | Born in another country | 82 (16) |

| Residence | Family | 281 (53) |

| Own place/apartment/dorm | 191 (36) | |

| With friends/partner | 36 (7) | |

| No regular place/other | 18 (3) | |

| School/Employment | In school | 113 (21) |

| In school, employed | 142 (27) | |

| Employed, not in school | 201 (38) | |

| Not employed, not in school | 70 (13) | |

| Sexual identity | Gay | 391 (74) |

| Other same-sex identity | 38 (7) | |

| Bisexual | 85 (16) | |

| Straight | 3 (1) | |

| DK/RF | 9 (2) | |

| Sexual attraction | Males only | 371 (71) |

| Males and females | 144 (27) | |

| Females only | 6 (1) | |

| Neither, don't know, missing | 5 (1) | |

| Stressful Life Events | Family Stress | 392 (75) |

| School/work Stress | 382 (73) | |

| Financial Stress | 360 (68) | |

| Partner-Related Stress | 320 (61) | |

| Peer Non-acceptance of Sexuality | 302 (57) | |

| Stress Related to Own Health Concerns | 231 (44) | |

| Stress Related to Friends' Health | 206 (39) | |

| Threat Related Stress | 178 (34) | |

| Death Stress | 85 (16) | |

| Emotional Distress (CESD) | Non-distressed/non-depressed (CESD score < 16) |

320 (61) |

| Distressed (CESD score 16-21) |

97 (18) | |

| Depressed (CESD score > 21) |

108 (21) | |

| Illicit drug use (w/o marijuana) | 148 (28) | |

| Alcohol misuse (frequent/binge drinking) |

170 (32) | |

| Unprotected anal intercourse (inconsistent condom use) |

197 (38) |

Note. Percentage calculated based on valid response.

Bivariate-level associations

Table 2 presents associations between experiences of life and sexual identity-related stressors and level of distress. Due to the large number of tests, results were evaluated at p≤.01. Findings clearly show a high degree of associations among different stressors, with the exception of death-related stress, possibly due to its low frequency. Again, with the exception of death-related stress and level of disclosure, each type of stressful life event was highly and significantly associated with a higher number of depressive symptoms.

Table 2.

Associations between Experiences of Stress and Psychological Functioning (N=526)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Types of Stress | |||||||||||||||

| 1. Family Stress | 1.00 | 0.17** | 0.19** | 0.10+ | 0.26** | 0.15** | 0.22** | 0.14** | 0.14** | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.21** | 0.13* | 0.09+ | 0.25** |

| 2. School/work Stress | 1.00 | 0.27** | 0.04 | 0.20 | 0.12* | 0.13* | 0.15** | 0.06 | −0.05 | 0.05 | 0.13* | 0.10+ | 0.10+ | 0.21** | |

| 3. Financial Stress | 1.00 | 0.04 | 0.22** | 0.21** | 0.13* | 0.17** | 0.10+ | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.15** | 0.12* | 0.13* | 0.22** | ||

| 4. Partner-Related Stress | 1.00 | 0.07 | 0.21** | 0.11* | 0.16** | 0.12* | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.15** | 0.05 | 0.14** | 0.17** | |||

| 5. Peer Non-acceptance of Sexuality | 1.00 | 0.16** | 0.12* | 0.19** | 0.05 | 0.10+ | −0.06 | 0.19** | 0.19** | 0.10+ | 0.24** | ||||

| 6. Stress Related to Own Health Concerns | 1.00 | 0.21** | 0.29** | 0.03 | −0.05 | 0.10+ | 0.22** | 0.08 | 0.15** | 0.26** | |||||

| 7. Stress Related to Friends' Health | 1.00 | 0.21** | 0.20** | −0.08 | 0.10+ | 0.16** | 0.05 | 0.12* | 0.20** | ||||||

| 8. Threat Related Stress | 1.00 | 0.11* | 0.03 | −0.07 | 0.17** | 0.19** | 0.21** | 0.26** | |||||||

| 9. Death Stress | 1.00 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.10+ | 0.06 | 0.08+ | 0.06 | ||||||||

| 10. Internalized Homophobia | 1.00 | −0.46** | −0.09+ | 0.17** | −0.08+ | 0.13* | |||||||||

| 11. Level of Disclosure | 1.00 | 0.08 | −0.34** | 0.20** | 0.01 | ||||||||||

| 12. Homophobia Growing Up | 1.00 | 0.30** | 0.26** | 0.31** | |||||||||||

| 13. Homophobia that Requires Identity Management | 1.00 | 0.13* | 0.27** | ||||||||||||

| 14. Extreme Homophobia (e.g., physical assault) | 1.00 | 0.24** | |||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Psychological Functioning | |||||||||||||||

| 15. Emotional Distress | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||

Note. Due to the large number of tests, significance is set at

p ≤ .05;

p ≤ .01;

p ≤ .001.

Presented in Table 3 are bivariate associations between stressors, individual differences in psychosocial and demographic factors, and outcome variables of interest. Similar to what was found previously (Wong et al., 2008), Caucasian YMSM were significantly more likely to engage in drug use and alcohol misuse compared to the African American cohort. While there were no age effects, we found living with family to be a significant protective factor for drug use and alcohol misuse. Among stressors, greater experience of extreme gay harassment was significantly associated with greater likelihood of all three HIV-risk related behaviors (p values ranged from ≤.05 to ≤ .01). Greater disclosure predicted increased odds of drug use and alcohol misuse (p<.01; p<.001, respectively) while greater internalized homophobia was associated with decreased odds of both drug use (p≤.05) and alcohol misuse (p≤.05). Stress related to concerns about own health predicted greater drug use (p≤.01), alcohol misuse (p≤.05), and inconsistent condom use (p≤.001). In contrast, experiences of peer non-acceptance of sexuality predicted lower likelihood of alcohol misuse (p≤.01). Financial stress was associated with greater odds of drug use (p≤.01) and alcohol misuse (p≤.05). School- and work-related stress and partner-related stress were associated with greater likelihood of inconsistent condom use (p≤.05; p≤.001, respectively).

Table 3.

Bivariate Associations between Stress, Psychosocial/Demographic Covariates and HIV-Risk Related Behaviors (N = 526)

| Illicit Drug Use |

Alcohol Misuse |

Unprotected Anal Intercourse (UAI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-Demographic Variables | |||

| Ethnicity | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

| African - American | 22 (18) | 24 (19) | 48 (38) |

| Latino of Mexican descent | 51 (25) | 66 (32) | 72 (35) |

| Caucasian | 75 (39)*** | 80 (41)*** | 77 (39) |

| Age group | |||

| 18 - 19 yrs | 53 (26) | 59 (29) | 72 (35) |

| 20 – 21 yrs | 52 (27) | 68 (35) | 77 (39) |

| 22+ yrs | 43 (35) | 43 (35) | 48 (39) |

| Living with Family | 62 (42)*** | 75 (44)** | 100 (51) |

|

Psychosocial Characteristics (sample range) |

m (sd) | m (sd) | m (sd) |

| Distress (CESD) (0 – 54.00) | 16.60 (11.19)* | 15.91 (10.82) | 16.38 (11.45)* |

| Proactive Coping (23.00-56.00) | 45.53 (5.55)* | 46.82 (5.11) | 45.73 (5.40)* |

| Family Support (1.00-4.00) | 2.95 (0.73) | 3.02 (0.72) | 2.95 (0.72) |

| Friends' Support (.175-4.00) | 3.52 (0.52) | 3.59 (0.47)** | 3.49 (0.54) |

|

Sexual Identity-Related Stress (sample range) |

m (sd) | m (sd) | m (sd) |

| Internalized homophobia (1.27-3.20) | 2.05 (0.31)* | 2.04 (0.30)* | 2.07 (0.30) |

| Level of Disclosure (1.00-4.00) | 3.15 (0.73)*** | 3.10 (0.75)** | 2.94 (0.78) |

| Homophobia Growing Up (1.00-4.00) | 2.85 (0.78) | 2.93 (0.78) | 2.87 (0.79) |

| Homophobia that Requires Identity Management (1.00-4.00) | 1.88 (0.77) | 1.87 (0.73) | 1.88 (0.72) |

| Extreme Homophobia (e.g., physical assault) (1.00-3.00) | 1.18 (0.33)* | 1.18 (0.33)* | 1.18 (0.33)* |

| Stressful Life Events | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

| Family Stress | 118 (30)+ | 132 (34) | 155 (40)+ |

| School/work Stress | 114 (30) | 127 (33) | 153 (40)* |

| Financial Stress | 116 (32)** | 127 (35)* | 139 (39) |

| Partner-Related Stress | 92 (29) | 111 (35) | 144 (45)*** |

| Peer Non-acceptance of Sexuality | 91 (30) | 84 (28)** | 110 (36) |

| Stress Related to Own Health Concerns | 81 (35)** | 88 (38)* | 108 (47)*** |

| Stress Related to Friends' Health | 61 (30) | 69 (34) | 83 (40) |

| Threat Related Stress | 58 (33) | 64 (36) | 71 (40) |

| Death Stress | 22 (26) | 28 (33) | 32 (38) |

| HIV-Risk Related Behaviors | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

|

| |||

| Illicit Drug Use | 74 (50)*** | 72 (49)*** | |

| Alcohol Misuse | 70 (41) | ||

| Unprotected Anal Intercourse | |||

Note. For all continuous variables, the greater the score, the greater the likelihood of experience.

p ≤ .10;

p ≤ .05;

p ≤ .01;

p ≤ .001

Regression Findings

Results from hierarchical logistic regression models found that stress related to finances remained significant and lead to a greater likelihood of recent drug use (OR=1.77; 95% CI=1.07,2.92; p≤.05) and alcohol misuse (OR=1.63; 95% CI=1.07,2.64; p≤.05) after accounting for other significant effects of covariates at each step. Similar to bivariate findings, greater experience of peer non-acceptance of sexuality was significantly associated with less alcohol misuse (OR=.58; 95% CI=0.38,0.87; p≤.01). Partner-related stress (e.g., arguments with partners or breakup) and stress associated with own health were significant predictors of recent inconsistent condom use (OR=2.23; 95% CI=1.49,3.35; p≤.001; OR=1.67; 95% CI=1.13,2.46; p≤.01, respectively). Stress related to own health was also associated with greater odds of alcohol misuse (OR=1.55; 95% CI=1.03,2.32; p≤.05).

Mediation findings

Results from bivariate analysis indicated that drug use was significantly associated with inconsistent condom use and alcohol misuse, but alcohol misuse was not significantly associated with inconsistent condom use, thereby suggesting that alcohol misuse may not be a viable mediator in the current analysis. Hence, we revised the hypothesized model and removed the path linking alcohol misuse and inconsistent condom use, then proceeded to test the partially mediated model involving only drug use as the mediator (see Figure 2). It should be noted that even though no direct relationships at the bivariate level were observed between some of the variables that predicted drug use (e.g., race/ethnicity, living with family) and inconsistent condom use, researchers have concurred that such an association, as initially proposed by Baron and Kenny (1986), may not be necessary, particularly when effect sizes could be small or if suppression is suspected (Shrout & Bolger, 2002).

Figure 2.

Estimated Path Model Linking Specific Stressors and Individual Differences Variables to Substance Use and Unprotected Anal Intercourse

Note. Model indicates only significant paths (p ≤.05). Unstandardized coefficients are presented along with standardized coefficients (in parentheses).

The partially mediated model appears to have good fit to the data as indicated by the TLI and CFI to be >.95 and the RMSEA to be <.001. Significant path coefficients that led to a lower probability of drug use include: 1) living at home (B= −0.31, 95%CI =−0.59,−0.01)2; 2) being African American relative to Caucasians (B= −0.58, 95%CI= −0.90,−0.22); and 3) greater proactive coping (B= −0.03, 95%CI= −0.05,0.00). Paths that to led to a higher probability of drug use are: 1) financial stress (B=0.31, 95%CI=0.03,0.63); and 2) sexual identity disclosure (B=0.22, 95%CI=0.10,0.41). Significant paths to lower probability of alcohol misuse are: 1) being African American relative to Caucasians (B= −0.50, 95%CI= −0.85,−0.15); and 2) greater experience of peer non-acceptance of sexuality (B= −0.38, 95%CI = −0.62,−0.08). The only path that showed a higher probability of alcohol misuse is greater perceived support from peers (B = 0.30, 95%CI = 0.02, 0.57). Finally, drug use, experience of partner-related stress, and stress about one's own health all predicted greater probability of inconsistent condom use (B=0.23, 95%CI=0.05,0.37; B=0.47, 95%CI=0.21,0.71; and B=0.29, 95%CI=0.02,0.56, respectively). Tests of indirect effects using the bias-corrected bootstrap method revealed no significant association between specific stressors and inconsistent condom use via drug use. Overall, these results suggested that even though drug use may be an important predictor of inconsistent condom use, it does not appear to significantly mediate the impact of stressors on inconsistent condom use.

Discussion

Findings from the current study clearly show that emerging adult YMSM experience a wide variety of stressors. These experiences are in turn associated with increased risk for substance use and HIV infection/transmission. Participants experienced stressors across life domains that are particularly relevant for emerging adults (Arnett & Tanner, 2006) including work/school environment, finances, and romantic attachments. As young adult gay men, there also appears to be an acute concern for HIV-related health issues. Consistent with previous studies (Lewis, Derlega, Griffin, & Krowinski, 2003; Rosario, Rotheram-Borus, & Reid, 1996), experiences of stressful life events were significantly associated with participants' level of distress. While psychological distress was associated with drug use and inconsistent condom use at the bivariate level, once the effects of stressful life events were considered, psychological functioning was no longer a significant predictor of these HIV-risk behaviors. Among individual difference factors, the protective effects of proactive coping and living with family were both diminished when stressful life events were considered.

Results from this study highlight the significant impact that stressful life events can have in the lives of YMSM and show that the patterns of risk behaviors differ depending on the type of stressful event(s) experienced by YMSM. Results also point to the importance of examining stressors related to both sexual identity and emerging adulthood as they have significant and distinct impact on HIV-risk behaviors. For example, when each risk behavior is examined separately, the experience of stress associated with financial difficulties consistently predicted both drug use and alcohol misuse. Level of sexual identity disclosure was only significantly associated with drug use. Stress related to one's own health concerns also predicted alcohol misuse. Partner-related stress and stress associated with concerns about ones' own health were significantly associated with sexual risk-taking.

While previous research has linked alcohol use with risky sexual behaviors (Stall, McKusick, Wiley, Coates, & Ostrow, 1986), only illicit drug use significantly predicted inconsistent condom use in the current study. This finding is consistent with research that showed a causal link between illicit drug use and HIV-risk behavior in this population (Halkitis, Parsons, & Stirratt, 2001; Stall et al., 1986; Stall & Purcell, 2000; Waldo, McFarland, Katz, MacKellar, & Valleroy, 2000). However, drug use did not significantly mediate the effects of stress on unprotected anal intercourse. Despite this, drug use may be a significant mediator of other psychosocial processes not examined currently.

Limitations associated with this study may affect the interpretation and generalizability of the findings. First, current findings rely on participants' self-reported behaviors, which cannot be independently verified. Self-report data regarding participants' involvement in risky behaviors and their psychological state can potentially underestimate their true prevalence. However, the use of ACAI may have minimized underreporting of these behaviors. In addition, the data are cross-sectional and therefore we cannot establish causality between experience of stressful life events, distress, and adoption of risky behaviors. For example, the association between the stress of health concerns and HIV-risk behavior may either suggest that individuals who have engaged in risky behavior may experience greater fears that they are HIV infected, or that health-related fears and concerns may trigger self-destructive behaviors that lead to greater involvement in risky behaviors. Moreover, given this is not a population-based study, we lack a comparison group of similarly aged heterosexual young men. Despite the importance of understanding whether observed effects are unique to this population compared to others, studies that examine within-group differences allow for an in-depth investigation of psychosocial processes. The current study enables us to focus on how variability in the experience of stressors from different life domains can differentially impact risk-taking behaviors for this population. Finally, although this sample is likely to be representative of YMSM who can be recruited through gay-identified venues, it is not representative of the larger YMSM population. However, given the rigor used to recruit participants into the study, one can have a fair amount of confidence with respect to the generalizablity of these findings to those YMSM who spend time in these venues. This is an important consideration given that the ultimate goal of such research is to understand risks and identify opportunities for prevention and early intervention.

To understand the mechanisms linking stress and psychosocial and environmental factors with HIV-risk taking, future research must focus on identifying potential factors (e.g., self-efficacy, emotion regulation) that can moderate the influences of stressful life experiences YMSM encounter. This research could then inform the design of targeted intervention. For example, if financial stressors may lead to alcohol and drug use, the development of programs that improve self-efficacy or control, such as those that teach youth basic skills in money management, may help alleviate some of the stress associated with this stressor and may lead to a reduction in risk behaviors. Qualitative research or diary studies could also help identify a variety of contextual factors that may affect these associations. In addition, future research must also examine longitudinal changes in the complex associations between specific types of stressful events and particular risk behaviors. As observed in current results, the significant association between greater perceived peer support and greater odds of alcohol misuse could be a function of this developmental timeframe. Despite the limitations, findings from the current study clearly show that emerging adulthood is an enormously stressful time in the lives of YMSM and that stressors from different life domains can have distinct impact on YMSM's risk-taking. The heterogeneity of these stressful experiences and their differential impact on risk behaviors suggest that interventions may need to be targeted at specific sets of stressors if they seek to diminish YMSM's adoption of specific types of risk behaviors.

Table 4.

Hierarchical Logistic Regression Analyses of Stress as Predictors of HIV-Risk Behaviors among YMSM (N=526)

| Illicit drug use | Alcohol Misuse | Unprotected Anal Intercourse(UAI) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | |

| Steps | ||||||

| 1. Socio-Demographic Variables | ||||||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| Caucasian | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| African-American | 0.37*** | (0.21-0.67) | 0.45** | (0.26-0.79) | - | - |

| Latino of Mexican descent | 0.69 | (0.42-1.11) | 0.94 | (0.60-1.48) | - | - |

| Living with Family | 0.63* | (0.40-0.99) | 0.64* | (0.42-.0.98) | - | - |

| 2. Psychosocial Characteristics | ||||||

| Distress (CESD) | 1.00 | (0.98-1.02) | - | - | 1.00 | (0.98-1.02) |

| Proactive Coping | 0.96* | (0.92-0.99) | - | - | 0.97+ | (0.93-1.00) |

| Friend's Support | - | - | 1.82* | (1.20-2.76) | - | - |

| 3. Sexual Identity-Related Stress | ||||||

| Internalized Homophobia | 0.80 | (0.37-1.73) | 0.90 | (0.43-1.86) | - | - |

| Level of Disclosure | 1.46* | (1.07-2.00) | 1.19 | (0.89-1.59) | - | - |

| Extreme Homophobia (e.g., physical assault) | 1.52 | (0.83-2.82) | 1.69+ | (0.94-3.05) | 1.24 | (0.69-2.22) |

| 4. Stressful Life Events | ||||||

| Family Stress | 1.24 | (0.73-2.10) | - | - | 1.09 | (0.69-1.72) |

| School/work Stress | - | - | - | - | 1.33 | (0.86-2.06) |

| Financial Stress | 1.77* | (1.07-2.92) | 1.63* | (1.07-2.64) | ||

| Partner-related Stress | - | - | - | - | 2.23*** | (1.49-3.35) |

| Peer Non-Acceptance of Sexuality | - | - | 0.58** | (0.38-0.87) | ||

| Stress Related to Own Health Concerns | 1.40 | (0.91-2.16) | 1.55* | (1.03-2.32) | 1.67** | (1.13-2.46) |

Note. Only those variables were significant at p ≤ .10 from bivariate results were included in multivariate models. Dash “-” denotes the variable not included in each specific model. Omnibus tests of model coefficients were significant at each of the four steps with the exception of extreme homophobia for unprotected anal intercourse. Hosmer-Lemeshow Goodness-of-fit Chi2(8) for illicit drug use, alcohol misuse, and unprotected anal intercourse werre not significant, suggesting good or adequate fit; bolded numbers denote statistical significance.

p ≤ .10;

p ≤ .05;

p ≤ .01;

p ≤ .001

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Qualitative data is an integral component of the larger study, providing an in-depth understanding and greater context for specific key constructs. Qualitative sub-studies were conducted concurrently with the longitudinal quantitative data collection as well as during the formative phase of the research. For more information regarding the formative phase, please refer to McDavitt et al. (2008). To learn more about the qualitative component of the main phase of the project, please see Kubicek, Weiss, Iverson, & Kipke (in press).

Unstandardized coefficients and corresponding confidence intervals are reported.

References

- Arnett JJ, Tanner JL, editors. Emerging Adulthood: Coming of Age in the 21st Century. American Psychological Association; Washington, D.C.: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, Rothblum ED, Beauchaine TP. Victimization over the life span: A comparison of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and heterosexual siblings. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(3):477–487. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, DeLongis A, Kessler RC, Schilling EA. Effects of daily stress on negative mood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;57(5):808–818. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.57.5.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Trends in HIV/AIDS Diagnoses Among Men Who Have Sex with Men in 33 states. Minority Morbidity Weekly Report. 2008;57(25) [Google Scholar]

- Cochran BN, Stewart AJ, Ginzler JA, Cauce AM. Challenges faced by homeless sexual minorities: Comparison of gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender homeless adolescents with their heterosexual counterparts. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(5):772–777. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.5.773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran SD, Mays VM. Estimating prevalence of mental and substance-using disorders among lesbians and gay men from existing national health data. In: Omoto AM, Kurtzman HS, editors. Sexual orientation and mental health. American Psychological Association; Washington D.C.: 2006. pp. 143–165. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran SD, Sullivan JG, Mays VM. Prevalence of mental disorders, psychological distress, and mental health services use among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(1):53–61. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.71.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Augelli AR. Developmental and contextual factors and mental health among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths. In: Omoto AM, Kurtzman HS, editors. Sexual orientation and mental health: Examining identity and development in lesbian, gay, and bisexual people. Washington D.C.: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- D'Augelli AR, Grossman AH. Disclosure of sexual orientation, vicitmization, and mental health among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2001;16:1008–1027. [Google Scholar]

- D'Augelli AR, Grossman AH, Starks MT. Childhood gender atypicality, victimization, and PTSD among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21:1462–1482. doi: 10.1177/0886260506293482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond LM. Love matters: Romantic relationships among sexual-minority adolescents. In: Florsheim P, editor. Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: Theory, research, and practical implications. Lawrence Earlbaum Associates, Inc; Mahwah, NJ: 2003. pp. 85–107. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond LM, Lucas S. Sexual-minority and heterosexual youths' peer relationships: Experiences, expectations, and implications for well-being. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2004;14(3):313–340. [Google Scholar]

- Dĺaz RM, Ayala G, Bein E, Henne J, Marin BV. The impact of homophobia, poverty, and racism on the mental health of gay and bisexual Latino men: Findings from 3 US cities. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(6):927–932. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuRant RH, Krowchuk DP, Sinai SH. Victimization, use of violence, and drug use at school among male adolescents who engage in same=sex sexual behavior. Journal of Pediatrics. 1998;133:113–118. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70189-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre SL, Milbrath C, Peacock B. Romantic relationship trajectories of African American gay/bisexual adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2007;22(2):107–131. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman SS, Cauffman E. Your cheatin' heart: Attitudes, behaviors, and correlates of sexual betrayal in late adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1999;9(3):227–252. [Google Scholar]

- Ford W, Weiss G, Kipke MD, Ritt-Olson A, Iverson E, Lopez D. The Healthy Young Men's Study: Sampling methods for enrolling a cohort of young men who have sex with men. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services: Issues in practice, policy and research. doi: 10.1080/10538720802498280. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz MS, MacKinnon DP. Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science. 2007;18(3):233–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garofalo R, Wolf C, Kessel S, Palfrey J, DuRant RH. The association between risk behaviors and sexual orientation among a school=based sample of adolescents. Pediatrics. 1998;101(5):895–902. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.5.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenglass E, Schwarzer R, Jakubiec D, Fiksenbaum L, Taubert S. The proactive coping inventory (PCI): A multidimensional research instrument; Paper presented at the 20th International Conference of the Stress and Anxiety Research Society; Cracow, Poland. 1999, July 12-14; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis PN, Parsons JT, Stirratt M. A double epidemic: Crystal methamphetamine drug use in relation to HIV transmission among gay men. Journal of Homosexuality. 2001;41(2):17–35. doi: 10.1300/J082v41n02_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper GW. Sex isn't that simple: Culture and context in HIV prevention interventions for gay and bisexual male adolescents. American Psychologist. 2007:806–819. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.8.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatred in the hallways: Violence and discrimination against lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender students in U.S schools. New York, NY: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Henning-Stout M, James S, Macintosh S. Reducing harassment of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning youth. School Psychology Review. 2000;29(2):180–192. [Google Scholar]

- Hershberger SL, D'Augelli AR. The impact of victimization on the mental heatlh and suicidality of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31(1):65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Huebner DM, Rebchook GM, Kegeles SM. Experiences of harassment, discrimination, and physical violence among young gay and bisexual men. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(7):1200–1203. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R. Risk behavior in adolescence: A psychosocial framework for understanding and action. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1991;12:597–605. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(91)90007-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan KM. Substance abuse among gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, and questioning adolescents. School Psychology Review. Special Issue: Mini-Series: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transexual, and Questioning Youths. 2000;29(2) [Google Scholar]

- Kipke MD, Kubicek K, Weiss G, Wong CF, Lopez D, Iverson E, et al. The health and health behaviors of young men who have sex with men. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;40(4):342–350. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kipke MD, Weiss G, Wong CF. Residential status as a risk factor for drug use and HIV risk among YMSM. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11(6 Suppl):56–69. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9204-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissinger P, Rice J, Farley T, Trim S, Jewitt K, Margavio V, et al. Application of computer-assisted interviews to sexual behavior research. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1999;149(10):950–954. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koblin BA, Chesney MA, Husnik M, Bozeman S, Celum C, Buchbinder S, et al. High-risk behaviors among men who have sex with men in 6 US cities: Baseline data from the EXPLORE Study. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(6):926–932. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.6.926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, Diaz EM. The 2005 national school climate survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth in our nation's schools. GLSEN; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kubicek K, Weiss G, Iverson E, Kipke MD. Unpacking the complexity of substance use among YMSM: Increasing the role of qualitative strategies to make the most of mixed methods research. Substance Use & Misuse. doi: 10.3109/10826081003595366. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis RJ, Derlega VJ, Griffin JL, Krowinski AC. Stressors for gay men and lesbians: Life stress, gay-related stress, stigma consciousness, and depressive symptoms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2003;22(6):716–729. [Google Scholar]

- MacKellar DA, Valleroy LA, Karon JM, Lemp GF, Janssen RS. The Young Men's Survey: Methods for estimating HIV seroprevalence and risk factors among young men who have sex with men. Public Health Reports. 1996;111(Supplement 1):138–144. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Dwyer JH. Estimating mediated effects in prevention studies. Evaluative Review. 1993;17:144–158. [Google Scholar]

- Mays V, Cochran SD. Mental health correlates of perceived discrimination among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(11):1869–1876. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.11.1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDavitt B, Iverson E, Kubicek K, Weiss G, Wong CF, Kipke MD. Strategies used by gay and bisexual young men to cope with heterosexism. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services. 2008;20(4) doi: 10.1080/10538720802310741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNall M, Remafedi G. Relationship of amphetamine and other substance use to unprotected intercourse among young men who have sex with men. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 1999;153:1130–1135. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.11.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129(5):674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, Schwartz S, Frost DM. Social patterning of stress and coping: Does disadvantaged social status confer more stress and fewer coping resources? Social Science & Medicine. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.012. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills TC, Paul JP, Stall RD, Pollack LM, Canchola JA, Chang YJ, et al. Distress and depression in men who have sex with men: The urban men's health study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161(2):278. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.2.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhib F, Lin L, Steuve A, Miller R, Ford W, Johnson W, et al. The Community Intervention Trial for Youth (CITY) Study team: A venue-based method for sampling hard to reach populations. Public Health Reports. 2001;116(S2):216–222. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.S1.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nott KH, Vedhara K. The measurement and significance of stressful life events in a cohort of homosexual HIV positive men. AIDS Care. 1995;7(11):55–69. doi: 10.1080/09540129550126966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presley CA, Pimental ER. The introduction of the heavy and frequent drinker: A proposed classification to increase accuracy of alcohol assessments in postsecondary educational setting. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67(2):324–331. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Ragins BR, Cornwell JM. Pink triangles: Antecedents and consequences of perceived workplace discrimination against gay and lesbian employees. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2001;86(6):1244–1261. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.6.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragins BR, Singh R, Cornwell JM. Making the invisible visible: Fear and disclosure of sexual orientation at work. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2007;92(4):1103–1118. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.4.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remafedi G. Health disparities for homosexual youth: The children left behind. In: Wolitski R, Stall R, Valdiserri R, editors. Unequal opportunity: Health disparities affecting gay and bisexual men in the United States. Oxford University Press; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rivers I. Social exclusion, absenteeism and sexual minority youth. Support for Learning. 2000;15(1):13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Roffman DM. A model of helping schools address policy options regarding gay and lesbian youth. Journal of Sex Education & Therapy. 2000;25(2/3):130–137. [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Hunter J, Gwadz MV. Exploration of substance use among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth: Prevalence and correlates. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1997;12(4):454–476. [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Reid H. Gay-related stress and its correlates among gay and bisexual adolescents of predominantly Black and Hispanic background. Journal of Community Psychology. 1996;24:136–159. [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J. Predictors of substance use over time among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths: An examination of three hypotheses. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:1623–1631. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J, Gwadz MV. Gay-related stress and emotional distress among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths: A longitudinal examination. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70(4):967–975. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.4.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross MW, Simon Rosser BR. Measurement and correlates of internalized homophobia: A factor analytic study. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1996;52(1):15–21. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(199601)52:1<15::AID-JCLP2>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross MW, Tikkanen R, Mansoon SA. Differences between Internet and samples and conventional samples of men who have sex with men. Social Science and Medicine. 2000;4:749–758. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00493-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostosky SS, Owens GP, Zimmerman RS, Riggle EDB. Associations among sexual attraction status, school belonging, and alcohol and marijuana use in rural high school students. Journal of Adolescence. 2003;26:741–751. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Hunter J, Rosario M. Suicidal behavior and gay-related stress among gay and bisexual male adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1994;9(4):498–508. [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Rosario M, Van Rossem R, Reid H, Gillis R. Prevalence, course, and predictors of multiple problem behaviors among gay and bisexual male adolescents. Developmental Psychology. Special Issue: Sexual Orientation and Human Development. 1995;31(1):75–85. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C, Huebner D, Diaz RM, Sanchez BA. Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in White and Latino Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Young Adults. Pediatrics. 2009;123:346–352. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC. Verbal and physical abuse as stressors in the lives of lesbian, gay male, and bisexual youths: Associations with school problems, running away, substance abuse, prostitution, and suicide. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62(2):261–269. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC. And then I became gay. Routledge; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC. Mom, dad. I'm gay. How families negotiate coming out. American Psychological Association; Washington D.C.: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC. A critique of research on sexual-minority youths. Journal of Adolescence. 2001;24:5–13. doi: 10.1006/jado.2000.0369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(4):422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stall RD, McKusick L, Wiley J, Coates TJ, Ostrow DG. Alcohol and drug use during sexual activity and compliance with safe sex guidelines for AIDS: The AIDS behavioral research project. Health Education Quarterly. 1986;13(4):359–371. doi: 10.1177/109019818601300407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stall RD, Purcell DW. Intertwining epidemics: A review of research on substance use among men who have sex with men and its connection to the AIDS epidemic. AIDS and Behavior. 2000;(4):181–192. [Google Scholar]

- Turner CF, Ku L, Rogers SM, Lindberg LD, Pleck JH, Sonenstein FL. Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, and violence: Increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science. 1998;280:867–873. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldo CR, McFarland W, Katz MH, MacKellar DA, Valleroy LA. Very young gay and bisexual men are at risk for HIV infection: The San Francisco Bay Area Young Men's Survey II. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2000;24:168–174. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200006010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby BLB, Malik NM, Lindahl KM. Parental reactions to their sons' sexual orientation disclosures: The roles of family cohesion, adaptability, and parenting style. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2006;714(1) [Google Scholar]

- Wolitski R, Stall R, Valdiserri RO, editors. Unequal Opportunity: Health Disparities Affecting Gya and Biseuxal Men in the United States. Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wong CF, Kipke MD, Weiss G. Risk factors for alcohol use, frequent use, and binge drinking among young men who have sex with men. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33(8):1012–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimet G, Dahlem N, Zimet S, Farley G. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1988;52(1):30–41. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]