Abstract

Apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 (APE1 or Ref-1) is the major enzyme in mammals for processing abasic sites in DNA. These cytotoxic and mutagenic lesions arise via spontaneous rupture of the base-sugar bond or the removal of damaged bases by a DNA glycosylase. APE1 cleaves the DNA backbone 5′ to an abasic site, giving a 3′-OH primer for repair synthesis, and mediates other key repair activities. The DNA repair functions are essential for embryogenesis and cell viability. APE1-deficient cells are hypersensitive to DNA-damaging agents, and APE1 is considered an attractive target for inhibitors that could potentially enhance the efficacy of some anti-cancer agents. To enable an important new method for studying the structure, dynamics, catalytic mechanism, and inhibition of APE1, we assigned the chemical shifts (backbone and 13Cβ) of APE1 residues 39-318. We also report a protocol for refolding APE1, which was essential for achieving complete exchange of backbone amide sites for the perdeuterated protein.

Keywords: APE1, Ref-1, APEX1, Apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease, DNA base excision repair, NMR chemical shift assignments

Biological context

Apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 (APE1) is a multifunctional protein with essential roles in DNA repair and transcriptional regulation in mammals (Bhakat et al. 2009). APE1 is also known as Ref-1 (redox enhancing factor-1), reflecting its role in activating c-Jun, NF-κB, and other key transcription factors, which is thought to involve the reduction of a Cys side chain in their DNA-binding domain. In addition, APE1, together with other proteins, binds to so-called negative Ca2+-response elements (nCaRE) to regulate the expression of some genes, an activity that requires acetylation of APE1 (Ca2+-dependent) by the transcriptional co-activator p300. APE1 initiates the repair of mutagenic and cytotoxic abasic sites in DNA, lesions that are generated by spontaneous depurination (~10,000 times per cell per day) or removal of damaged bases by a DNA glycosylase to initiate base excision repair. APE1 hydrolyses the phosphodiester bond 5′ to AP sites to give a single strand break, and its 3′-phosphodiesterase activity can remove fragmented sugar moieties at the 3′ end of DNA strand breaks caused by some drugs (bleomycin) or ionizing radiation. In both cases, APE1 produces a 3′-OH primer for repair synthesis by DNA polymerase pol β. APE1 is the major AP endonuclease in humans; its repair activity is essential for embryogenesis and cell viability and its suppression increases the number of abasic sites and triggers apoptosis. APE1 confers resistance to pro-apoptotic stimuli including ionizing radiation, oxidative stress, and some chemotherapeutic agents, and suppression of APE1 sensitizes cells to DNA-damaging agents including some used to treat cancer (Fishel and Kelley 2007). Thus, inhibition of APE1 is an attractive strategy for increasing the efficacy of anti-cancer drugs, including alkylating agents and antimetabolites such as 5-fluorouracil (McNeill et al. 2009). While potent and clinically useful inhibitors of APE1 are highly desirable, none have been identified to date. Despite the significant biochemical and structural studies conducted on APE1 over the past two decades, including crystal structures of free and DNA-bound APE1 (Beernink et al. 2001; Gorman et al. 1997; Mol et al. 2000), its catalytic mechanism has not been elucidated. To enable an important new experimental approach for studying the structure, dynamics, catalytic mechanism, post-translational modification (oxidation, acetylation), and inhibition of APE1, we have assigned the chemical shifts (backbone and 13Cβ) of perdeuterated APE1 residues 39-318.

Methods and experiments

While full length human APE1 contains 318 residues (35.6 kDa), previous structural and biochemical studies and our observations indicate that residues 1 to ~44 are disordered and are dispensable for AP endonuclease activity (Beernink et al. 2001; Gorman et al. 1997; Mol et al. 2000). Consistent with crystallographic studies showing a lack of electron density for residues 1–44, we observe~45 1H-15N peaks with very strong intensity and poor dispersion in a 15N-HSQC spectrum of full-length APE1 (not shown). Accordingly, we produced a plasmid for expressing residues 39-318 of APE1 (APE1ΔN38) via PCR amplification from a plasmid harboring the intact human APE1 gene and sub-cloning into the NheI and BamHI sites of a pET-28 plasmid (Novagen), and verified the construct by DNA sequencing. APE1ΔN38 is expressed and purified at 4°C as described for full-length APE1 (Fitzgerald and Drohat 2008), including Ni-affinity chromatography (Qiagen), overnight thrombin cleavage of the N-terminal poly-His tag (giving six non-native N-terminal residues, GSHMAS), and ion exchange using a 5 ml HiTrap SP HP column (GE Healthcare). This provides APE1ΔN38 (286 residues, 32.1 kDa) that is >99% pure as judged by SDS–PAGE (commassie stained gel). APE1ΔN38 is quantified by absorbance (ε280 = 54.4 mM−1cm−1). APE1ΔN38 has the same AP endonuclease activity (kcat) as full-length APE1 (not shown). Consistent with a disordered N-terminal domain, most of the very intense and poorly dispersed 1H-15N resonances in a 15N-HSQC spectrum of APE1 are not observed for APE1ΔN38 (not shown).

We initially sought to assign the chemical shifts for uniformly 13C,15N-labeled APE1ΔN38 using the standard triple-resonance NMR experiments, but we were unable to assign more than ~40% of the backbone resonances due to insufficient signal, indicating a need for perdeuterated protein and TROSY-based NMR experiments. To produce uniformly 2H,13C,15N-labeled APE1ΔN38, we transformed BL21(DE3) cells (Novagen) with the APE1ΔN38 expression plasmid, inoculated an LB plate and incubated overnight at 37°C. A single colony was added to 5 ml LB medium (H2O) and grown at 37°C to OD600 = 0.7, then a 1.4 ml volume was centrifuged and the isolated cells added to 20 ml MOPS minimal medium (H2O) and grown to OD600 = 0.6. Subsequently, a 4 ml volume was centrifuged and the isolated cells were added to 80 ml of MOPS-2H2O medium prepared with 99.9% 2H2O, U-[15N]-NH4Cl (1 g/l), and U-[2H,13C]-glucose (2 g/l) (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories). At OD600 = 0.5 the cells were diluted to 160 ml with MOPS-2H2O, grown to OD600 = 0.5, and diluted to 800 ml with MOPS-2H2O. At OD600 = 0.4 the temperature was reduced to 15°C and expression was induced with 0.4 mM isopropyl-1-thio-β-D-galactopyranoside and continued for 24 h. The 2H,13C,15N-labeled APE1ΔN38 was purified as outlined above, giving a final yield of 15 mg.

A key step in producing perdeuterated protein that is optimal for NMR studies is to replace 2H with 1H at backbone amide sites exhibiting slow exchange. This was important for APE1, because over 20% of the 1HN-15N peaks were substantially diminished or absent in a 2D 15N-TROSY spectrum of 2H,13C,15N-labeled APE1ΔN38 that was purified as described above, and many were still weak or absent after incubation of the protein at 30°C for several weeks (not shown). To achieve complete exchange of the backbone amide sites, we denatured APE1ΔN38 (6 M Gnd-HCl) and screened for refolding conditions that would provide the highest yield of catalytically active enzyme using a previously published buffer screen (Willis et al. 2005) with some important modifications. The protocol used to prepare the NMR sample is as follows. We denatured 15 mg of pure 2H,13C,15N-labeled APE1ΔN38 in 7.7 ml of buffer containing 6 M Gdn-HCl, 0.02 M Tris–HCl pH 7.8, 0.1 M NaCl, 5 mM DTT for 1 h at room temperature with stirring. The denatured protein was rapidly diluted in 154 ml refolding buffer containing a 2.5-fold molar excess of abasic DNA (an APE1 substrate), and incubated with stirring for 1 h at room temperature. The refolding buffer included 0.05 M Tris–HCl pH 8.2, 0.55 M Gnd-HCl, 0.011 M NaCl, 0.4 mM KCl, 5 mM TCEP, 2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2. The duplex DNA was prepared from two oligonucleotides (Keck Facility, Yale University), 5′-TCAFGTACAGA GCTGC (F is the tetrahydrofuran abasic site analog) and 5′-AGTGCATGTCTCGACG, which were purified and quantified as described (Fitzgerald and Drohat 2008). The refolded protein was dialyzed 16 h at 4°C versus ion exchange buffer (25 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 0.15 M NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.2 mM EDTA, 1% glycerol), and the DNA was fully removed by ion exchange chromatography, conducted twice, using a 5 ml HiTrap Q Sepharose HP column (GE Healthcare). The purified APE1ΔN38 was dialyzed against NMR buffer (0.02 M sodium phosphate pH 6.5, 0.1 M NaCl, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.2 mM EDTA) overnight at 4°C and then concentrated. The complete removal of DNA and proper refolding was demonstrated by our observation that the A280/A260 ratio and 15N-TROSY spectrum for refolded APE1ΔN38 is identical to that observed for APE1ΔN38 that had not been denatured or exposed to DNA. Moreover, the AP endonuclease activity (kcat) is the same for APE1ΔN38 that had and had not been denatured and refolded (not shown).

The NMR sample (0.33 ml) consisted of 0.8 mM APE1ΔN38 in NMR buffer with 10% 2H2O. The NMR experiments were performed at 298 K on a Bruker AVANCE 800 MHz NMR spectrometer equipped with a 5 mm triple-resonance cryogenic probe with z-axis pulse field gradients. We collected a 2D 15N-edited TROSY and TROSY-based versions of the standard triple resonance experiments, including the HNCA, HN(CO)CA, HNCACB, HN(CO)CACB, HNCO, and HN(CA)CO (Salzmann et al. 1999). NMR data were processed with NMRPipe (Delaglio et al. 1995) and analyzed with Sparky (Goddard and Kneller). The MARS program was used to obtain initial chemical shift assignments for many residues (Jung and Zweckstetter 2004). The 1H chemical shifts were referenced to external DSS, the 13C shifts were referenced indirectly to DSS using the frequency ratio 13C/1H = 0.251449530, and the 15N shifts were referenced indirectly to liquid ammonia using 15N/1H = 0.101329118.

Extent of assignments and data deposition

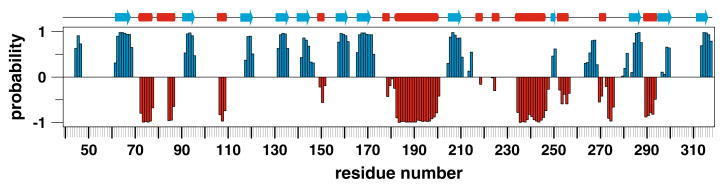

Analysis of the triple resonance experiments provided the sequence-specific assignments for over 90% of the backbone (1HN, 15N, 13Cα, 13C′) and 13Cβ resonances for APE1ΔN38. Figure 1 shows a 15N-TROSY spectrum of APE1ΔN38 with the backbone 1H-15N resonances assigned. We assigned 235 of 261 (90%) of the backbone 1HN-15N resonances (APE1ΔN38 has 280 native residues with 19 Pro), and 94% of 13Cα, 93% of 13Cβ, and 93% of 13C′ resonances. We assigned the 13Cα, 13Cβ, and 13C′ resonances for all Pro residues except Pro48, which is followed by Pro49, and Pro122 located in a loop region. The backbone 1HN-15N chemical shifts could not be assigned for residues G80-V84, E87, D90, E101, L104, S120, S123-G130, Q153-R156, G178, D210, T268, and G279. These residues are located in loops or regions for which low electron density or high temperature (B) factors are observed in one or more of the three crystal structures of free APE1 (Beernink et al. 2001; Gorman et al. 1997). The absence of backbone 1HN-15N resonances for residues in helix 1 (80-87) is consistent with evidence of mobility from crystallographic studies (higher than average B factors) and molecular dynamics simulations (Beernink et al. 2001). It was proposed that mobility of this helix may expose the buried Cys65 side chain, which has been proposed to play a role in the redox activation of transcription factors by APE1 (Beernink et al. 2001). As shown in Fig. 2, the secondary structure predicted by the program TALOS+ (Shen et al. 2009) using our assigned chemical shifts is in close agreement with crystal structures of APE1. Our assignment of the 13Cα and 13Cβ chemical shifts for all seven Cys residues of APE1 will facilitate NMR studies into the potential role of Cys oxidation in regulating its DNA repair activity and in its redox-mediated activation of transcription factors including c-Jun and NF-κB. We have also assigned chemical shifts for three residues essential for AP endonuclease activity, Tyr171, D210 (except 1HN, 15N) and His309, which could facilitate future NMR studies of their role in catalysis. The chemical shift assignments for APE1ΔN38 have been deposited in the BioMagResBank under the accession number 16516.

Fig. 1.

Shown is the 2D 15N-TROSY spectrum of 2H,13C,15N-labeled APE1ΔN38 (0.8 mM) collected at 298 K on an 800 MHz NMR spectrometer. For clarity, the region shown does not include G231 (δ1H = 6.23, δ15N = 118.3)

Fig. 2.

Secondary structure of APE1 predicted by TALOS+ using the chemical shifts reported here agrees with that observed in crystal structures of APE1. The output from the program TALOS+ (Shen et al. 2009) is displayed as a column chart (blue, β-strand; red, α-helix) and column height reflects the probability assigned by the prediction program of TALOS+ (α-helical values are negative for clarity). Shown above the column chart is the secondary structure observed in APE1 crystal structures (PDB ID: 1BIX, 1HD7)

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01-GM72711 to A.C.D.) and the University of Maryland Marlene and Stewart Greenebaum Cancer Center. B.M. is supported by a Chemistry-Biology Interface (CBI) Training grant from the NIH, T32-GM066706. The NMR spectrometers used in these studies were purchased, in part, with funds from shared instrumentation grants from the NIH (S10-RR10441; S10-RR15741; S10-RR16812; S10-RR23447) and the NSF (DBI 0115795). We thank Mike Morgan for producing the expression plasmid for APE1ΔN38.

References

- Beernink PT, Segelke BW, Hadi MZ, Erzberger JP, Wilson DM, 3rd, Rupp B. Two divalent metal ions in the active site of a new crystal form of human apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease, Ape1: implications for the catalytic mechanism. J Mol Biol. 2001;307:1023–1034. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhakat KK, Mantha AK, Mitra S. Transcriptional regulatory functions of mammalian ap-endonuclease (APE1/Ref-1), an essential multifunctional protein. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:621–637. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishel ML, Kelley MR. The DNA base excision repair protein Ape1/Ref-1 as a therapeutic and chemopreventive target. Mol Asp Med. 2007;28:375–395. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald ME, Drohat AC. Coordinating the initial steps of base excision repair: apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 actively stimulates thymine DNA glycosylase by disrupting the product complex. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:32680–32690. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805504200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard TD, Kneller DG. SPARKY. Vol. 3. University of California; San Francisco: [Google Scholar]

- Gorman MA, Morera S, Rothwell DG, de La Fortelle E, Mol CD, Tainer JA, Hickson ID, Freemont PS. The crystal structure of the human DNA repair endonuclease HAP1 suggests the recognition of extra-helical deoxyribose at DNA abasic sites. EMBO J. 1997;16:6548–6558. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.21.6548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung YS, Zweckstetter M. Mars—robust automatic backbone assignment of proteins. J Biomol NMR. 2004;30:11–23. doi: 10.1023/B:JNMR.0000042954.99056.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeill DR, Lam W, DeWeese TL, Cheng YC, Wilson DM., 3rd Impairment of APE1 function enhances cellular sensitivity to clinically relevant alkylators and antimetabolites. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7:897–906. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mol CD, Izumi T, Mitra S, Tainer JA. DNA-bound structures and mutants reveal abasic DNA binding by APE1 and DNA repair coordination [corrected] Nature. 2000;403:451–456. doi: 10.1038/35000249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzmann M, Wider G, Pervushin K, Senn H, Wuthrich K. TROSY-type triple-resonance experiments for sequential NMR assignments of large proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:844–848. [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y, Delaglio F, Cornilescu G, Bax A. TALOS plus: a hybrid method for predicting protein backbone torsion angles from NMR chemical shifts. J Biomol NMR. 2009;44:213–223. doi: 10.1007/s10858-009-9333-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis MS, Hogan JK, Prabhakar P, Liu X, Tsai K, Wei Y, Fox T. Investigation of protein refolding using a fractional factorial screen: a study of reagent effects and interactions. Protein Sci. 2005;14:1818–1826. doi: 10.1110/ps.051433205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]