Abstract

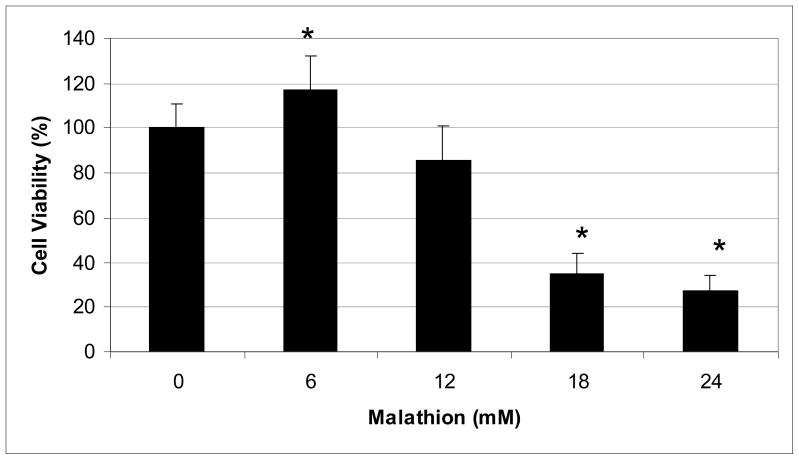

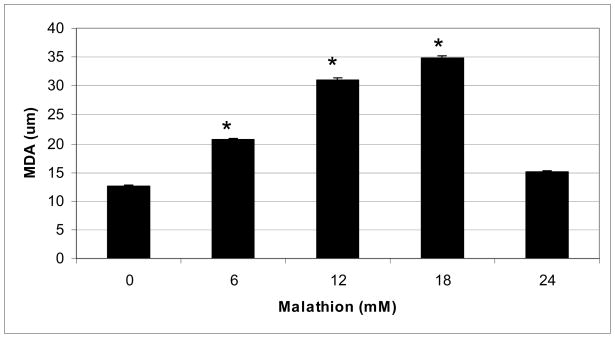

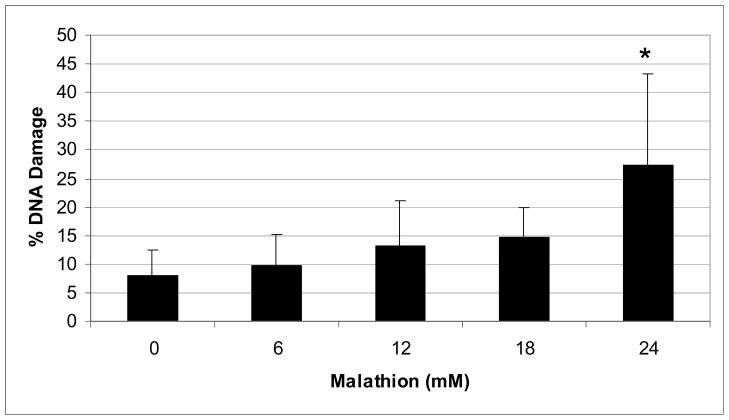

Malathion is an organophosphate pesticide that is known for its high toxicity to insects and low to moderate potency to humans and other mammals. Its toxicity has been associated with the inhibition of acetylcholinesterase activity, leading to the interference with the transmission of nerve impulse, accumulation of acetylcholine at synaptic junctions, and subsequent induction of adverse health effects including headache, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, bradycardia, and miosis. Oxidative stress (OS) has been reported as a possible mechanism of malathion toxicity in humans. Hence, the aim of the present study was to examine the role of OS in malathion-induced cytotoxicity and genotoxicity. To achieve this goal, MTT, lipid peroxidation, and single cell gel electrophoresis (Comet) assays were performed, respectively to evaluate the levels of cell viability, malondialdehyde (MDA) production, and DNA damage in human liver carcinoma (HepG2) cells. Study results indicated that malathion is mitogenic at lower levels of exposure, and cytotoxic at higher levels of exposure. Upon 48 h of exposure, the average percentages of cell viability were 100±11%, 117±15%, 86±15%, 35±9%, and 27±7% for 0, 6, 12, 18, and 24 mM, respectively. In the lipid peroxidation assay, the concentrations of MDA produced were 12.55±0.16, 20.65±0.27, 31.1±0.40, 34.75±0.45, and 15.1±0.20 μM in 0, 6, 12, 18, and 24 mM of malathion, respectively. The Comet assay showed a significant increase in DNA damage at the 24mM malathion exposure. Taken together, our results indicate that malathion exposure at higher concentrations induces cytotoxic and genotoxic effects in HepG2 cells, and its toxicity may be mediated through oxidative stress as evidenced by a significant production of MDA, an end product of lipid peroxidation.

Keywords: malathion, cytotoxicity, lipid peroxidation, DNA damage, HepG2 cells

INTRODUCTION

The use of pesticides was first introduced in order to prevent, control and eliminate unwanted insects, pests and associated diseases. However, the increased use of these compounds has caused both environmental and public health concerns (Bhanti et al., 2007). Malathion is an organophosphate insecticide used in agriculture, commercial extermination, fumigation, veterinary practices, domestic, and public health purposes (Brocardo et al., 2007; Pluth et al. 1996; Sweeney et al., 1999). Because of its low mammalian toxicity, malathion has become one of the most commonly used organophosphate compounds in the United States; therefore becoming one of the major sources of occupational exposure to pesticides (Gwinn et al., 2005; Bonner et al., 2007). Symptoms associated with malathion poisoning include headache, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, weakness of muscles, difficulty breathing (Haque et al., 1987), bradycardia, bronchospasm, and miosis (Sweeney et al., 1999).

It has previously been reported that malathion has the potential to induce lipid peroxidation of cellular membranes through various biochemical processes (Yarsan et al., 1999). During the metabolic process, malathion has shown the potential to cause DNA damage in exposed individuals. Both in vivo and in vitro studies have reported the genotoxic effects of malathion (Blasiak et al., 1999). Recently, it has been reported that the metabolism of malathion produces reactive oxygen species that lead to the onset of oxidative stress (John et al., 2001; Fortunato et al., 2006). A more recent pilot study has pointed out that oxidative stress and DNA damage are possibly linked to pesticides-induced adverse health effects in agricultural workers (Muniz, 2008). Hence, the present study was designed to elucidate the role of oxidative stress in malathion-induced toxicity and genotoxicity, using human liver carcinoma (HepG2) cells as a test system based on the fact that the liver constitutes the primary organ of biotransformation of xenobiotic compounds.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Media

Malathion (1 g solution) CAS No. 121-75-5, Lot No. 256-112 B, PS86) with a purity of 98.2% was purchased from Chem Service (West Chester, PA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS), and Dulbeco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM, Lot. No. 123577) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection –ATCC (Manassas, VA).

Cell Culture

The human liver carcinoma (HepG2) cell line was purchased from American Type Culture Collection-ATCC (Manassas, VA). In the laboratory, HepG2 cells stored in liquid nitrogen were thawed by gentle agitation of vials for 2 min in a water bath at 37°C. After thawing, the content of each vial was transferred to a 75 cm2 tissue culture flask, diluted with DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% streptomycin and penicillin, and incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator to allow the cells to grow, and form a monolayer in the flask. The growth medium was changed two times per week. Cells grown to 75–85% confluence were washed with phosphate buffer saline (PBS), trypsinized with 3 mL of 0.25% (v) trypsin-0.0.3%/v) EDTA, diluted with fresh medium, and counted using a hemacytometer.

Cell Viability/Cytotoxicity Assay

To carry out this experiment, 1 × 104 cells plated in each well of 96-well plates were placed in the humidified 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C and allowed to attach to the substrate. Cells grown to 70–85% confluence were exposed to various concentrations (0, 6, 12, 18, and 24mM) of malathion using 1% DMSO as solvent. Using the trypan blue exclusion test to determine cell viability we found that there was no difference in cell count for treated (1% DMSO) cells and untreated (control) cells. The control and treated cells were incubated for 48 h in 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator. After incubation, the cell viability was evaluated using the MTT {3-(4, 5-dimethlthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide} assay according to the standard test protocol commonly used in our laboratory (Mosmann 1983, Yedjou et al. 2006, Yedjou and Tchounwou 2007).

Lipid Peroxidation Assay

Briefly, 2 × 106 HepG2 cells/mL were placed in a total volume of 10 ml growth medium, treated with different concentrations of malathion, and incubated in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C for 48 h. After the incubation period, cells were collected in test tubes and centrifuged. The cell pellets were re-suspended in 0.5 ml of Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, and lysed using a sonicator (W-220; Ultrasonic, Farmingdale, NY) under the conditions of duty cycle 25% and output control 40% for 5 sec on ice. All samples were centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 10 min and 200μl aliquot of the sample was assayed for malondialdehyde (MDA) according to the lipid peroxidation assay kit protocol (Calbiochem-Novabiochem, San Diego, CA). The absorbance of the sample was monitored at 586 nm, and the concentration of MDA was determined from a standard curve (Janero 1990; Yedjou et al., 2008)

Genotoxicity/Comet Assay

Human liver carcinoma (HepG2) cells were counted (10,000 cells/well) and re-suspended in the growth medium with 10% FBS. Aliquots of 100 μL of the cell suspension were placed in each well of 96-well plates, treated with 100μL aliquot of either media or malathion (6, 12, 18 and 24 mM) and incubated in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C for 48 h. After incubation, cells were harvested, centrifuged, washed with PBS free calcium and magnesium, and re-suspended in 100 μL PBS. In a 2 mL tube, 50 μL of the cell suspension and 500 μL of melted LMAgarose were mixed for the comet assay experiment according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Trevigen, Inc, Gaithersburg, MD) and as recently described in our laboratory (Yedjou and Tchounwou 2007).

Statistical Analysis

Data were presented as means ± standard deviations (SDs). Statistical analysis was done using one way analysis of variance (ANOVA’s Dunnett’s test) for multiple samples. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Cell viability, DNA damage, and MDA levels were presented graphically in the form of histograms, using Microsoft Excel computer program.

RESULTS

Induction of Ctotoxicity by Malathion

With respect to the cytotoxicity of malathion to human liver carcinoma cells, the MTT assay demonstrated the effect of malathion on the viability of HepG2 cells as shown in Figure 1. The MTT assay result suggested that low concentration (6mM) of malathion has a mitogenic effect on the growth of HepG2 cells. This significant (p <0.05) increase in cell viability compared to the control indicates that malathion induces cell proliferation at low levels of exposure. However, when cells were exposed to 12mM of malathion and higher, the percentages of cell viability decreased significantly in a concentration-dependent fashion. Overall, malathion exposure resulted in a hormesis effect in HepG2 cells.

Fig. 1.

Cytotoxicity of malathion to human liver carcinoma (HepG2) cells. HepG2 cells were cultured with different concentrations of malathion for 48h as indicated in the Materials and Methods section. Cell viability was determined based on the MTT assay. Each point represents a mean value and standard deviation of three experiments.

* Significantly different from the control.

Induction of Lipid Peroxidation by Malathion

The lipid peroxidation assay showed a significant increase in MDA levels in HepG2 cells exposed to malathion following 48 h of exposure (Fig. 2). This figure shows a biphasic response with respect to malathion exposure. We observed an increase in MDA production levels within the dose range of 0–18mM, with a peak at 18mM, followed by a decrease at 24mM. This decrease can be attributed to the lower percentage of viable cells at the highest concentration.

Fig. 2.

Effect of different concentrations of malathion on MDA production in HepG2 cells, as measured using the lipid peroxidation assay. HepG2 cells were treated with various concentrations of malathion as indicated in the Materials and Methods section. Values are expressed as means ± S.Ds. * Significantly different from control.

Induction of Genotoxicity by Malathion

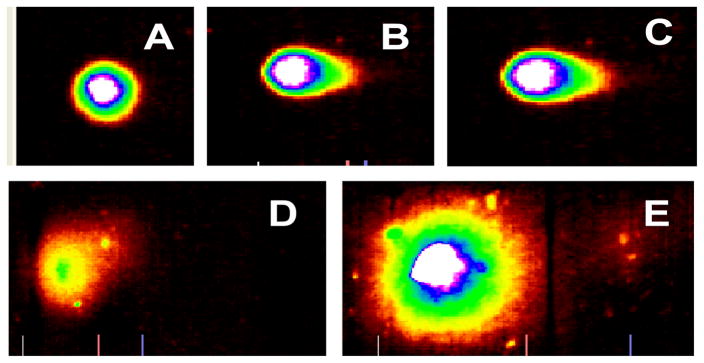

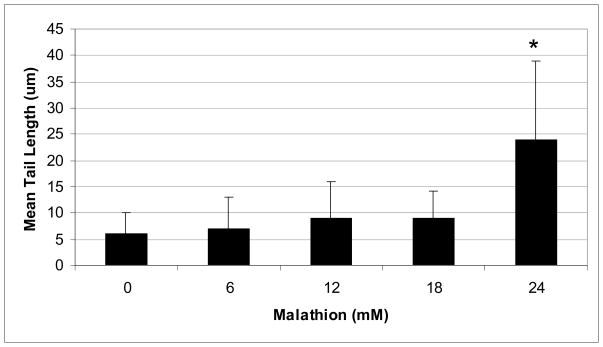

The representative comet assay images of control and malathion-treated HepG2 cells are presented in Figure 3. This figure shows an untreated (control) cell that has no DNA damage (intact nuclei), along with images that show DNA damage and the formation of a comet tail (6–24mM). Our data show a significant increase in percentage of DNA damage and comet tail length at higher levels of exposure (Figs. 4 & 5). The percentages of DNA cleavage were as follows: 7.93±4.51, 9.71±5.48, 13.16±7.87, 14.65±5.29, and 27.3±11.16% for 0, 6, 12, 18, and 24mM of malathion, respectively (Figure 4). A similar trend was observed in the mean lengths of comet tail (Fig. 5).

Fig. 3.

Representative SYBR Green Comet assay images of untreated (A-control) and malathion treated HepG2 cells at 6mM(B), 12mM(C), 18mM(D), and 24mM(E). The Comet assay was performed as stated in the Materials and Methods section.

Fig. 4.

Comet assay data showing the mean percentages of DNA damage in HepG2 cells as a function of malathion exposure. HepG2 cells were exposed to different concentrations of malathion (6, 12, 18, and 24mM) for 48h. Values are expressed as means ± S.Ds. * Significantly different from control.

Fig. 5.

Comet assay data showing the mean lengths of comet tail in HepG2 cells as a function of malathion exposure. HepG2 cells were exposed to different concentrations of malathion (6, 12, 18, and 24mM) for 48h. Values are expressed as means ± S.Ds.

* Significantly different from control.

DISCUSSION

Induction of Cytotoxicity by Malathion

Cytotoxicity can be described as the ability of a chemical compound to induce cell death. In the present study, the MTT assay was used to determine the general cytotoxicity of malathion in human liver carcinoma (HepG2) cells. Results obtained from the MTT assay indicated a strong concentration-response relationship with regard to malathion toxicity to HepG2 cells. It showed that malathion exposure modulates the viability of HepG2 cells. With exception to a proliferation of cell growth at 6mM, the percentages of viable cells showed a significant decrease (p < 0.05) compared to the control group.

Findings from our study clearly demonstrated that elevated concentrations of malathion are cytotoxic to human liver carcinoma (HepG2) cells, showing a 48 h-LC50 (concentration required to kill 50% of cell viability) of 19.78 mM. Published studies have also reported that malathion induces cytotoxic effect in splenocytes of female C57B1/6 mice (Rodgers et al., 1985), in human lymphoid cell cultures (Sobti et al., 1982), in hepatocytes and in HaCaT cells (Delescluse et al., 1998). Several other studies have demonstrated the cytotoxicity of malathion in cell and animal models. Chen and his collaborators have reported that malathion induced toxicity in fish cells in dose- and-time dependent manner (Chen et al., 2006). Some of the health concerns that have been linked to exposure to malathion and other pesticides exposure include acute and chronic toxicosis in humans and animals, liver and heart diseases, hormonal disorders, skin diseases, mutagenic and carcinogenic events and effects on lipid peroxidation (Yarsan et al., 1999).

Induction of Lipid Peroxidation by Malathion

Lipid peroxidation, a well-established mechanism of cellular injury in plants and animals, was used as an indicator of oxidative stress in the present study; by measuring the production level of MDA in HepG2 cells exposed to malathion. Previous studies have pointed out that the mechanism by which malathion exerts its toxic effect is through the accumulation of acetylcholine resulting from the inhibition of acetylcholinesterase (AchE). This accumulation often leads to the onset of side effects depending on the interaction of the substrate with cholinergic receptors. Interaction with these receptors also leads to the onset of lipid peroxidation (Hazarika et al., 2003). The release of phospholipids has therefore been reported to be very important in the action of AchE (Datta et al., 1994).

Our results showed that treatment of HepG2 cells with malathion resulted in a significant increase of MDA levels. We noted a biphasic response in MDA formation in exposed cells, with an increase of MDA formation between the concentrations of 0–18mM, followed by a decrease in MDA at 24mM. This decrease in MDA could be attributed to the lower percentage of viable cells at higher level of exposure as seen from the results of the MTT assay.

A recent study with rats has shown that malathion exposure leads to oxidative stress in cerebrospinal fluid, blood serum and brain structures (Fortunato et al., 2006). A similar study found comparable results with a dose-dependent increase of lipid peroxidation in the hippocampus and striatum of rats exposed to malathion in doses of 25, 50, 100 and 150mg/kg (Delgado et al., 2006). Haque and his collaborators reported a higher rate of lipid peroxidation in all parts of the brain of albino rats in regards to malathion exposure (Haque et al., 1987). Administration of malathion to rats for 4 weeks induced an increase in MDA formation in serum (Ahmed et al., 2000) as well as an increase in catalase (CAT) and superoxide dimutase (SOD) activities, and MDA levels in red blood cells and liver of exposed male Wister rats (Akhgari et al., 2003).

Elevated levels of lipid peroxidation products have also been reported in human erythrocyte membranes following exposure to malathion (Datta et al., 1994). In addition, Muniz and his collaborators reported an elevated level of oxidative stress and DNA damage in human lymphocytes of agricultural workers exposed to organophosphates compared to a control group (Muniz et al., 2008). MDA is a well known byproduct of lipid peroxidation, and its formation indicates a cellular damage following exposure to a xenobiotic compound. Hence, the production of higher levels of MDA in malathion-treated HepG2 cells is indicative of malathion-induced cell injury.

Induction of Genotoxicity by Malathion

We observed in the present study that malathion induced a gradual increase in DNA damage in HepG2 cells with increasing chemical concentrations. Upon 48 h of exposure, the mean percentages of DNA damage were computed to be 7.93±4.51, 9.71±5.48, 13.18±7.87, 14.65±5.29, and 27.3±11.16% for 0, 6 12, 18, and 24mM of malathion, respectively; suggesting that malathion acts as a genotoxic compound especially at the highest level of exposure. The other toxic end point (tail length) also follows the same pattern. Consistent with our findings, a group of researchers used the comet assay as an assessment tool to measure DNA damage in production workers exposed to pesticides in India. Their findings yielded an increase in mean comet tail length compared to a control group (Grover et al., 2003).

It has been reported that commercially purchasable malathion can cause DNA lesions in vivo, such as DNA breakage at sites of oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes, and induce malignancies in exposed individuals (Blasiak and Trzeciak, 1998). Although it has been pointed out that agents that have the ability to cause minimal DNA damage are generally not mutagenic or carcinogenic, those that cause sustained DNA/cell damage (but not cell death) are mutagenic and/or carcinogenic (ATSDR, 1999; Wei et al., 1999). Hence, further study is needed to investigate whether malathion represents a potential environmental mutagen and/or carcinogen. Previous studies have indicated that malathion is not a carcinogenic agent (Bonner et al., 2007). However, recent studies conducted by Reus and his groups found that malathion has the potential to induce mutagenic and/or carcinogenic effects in the cerebral tissue and peripheral blood of rats after acute and chronic exposure (Reus et al., 2008). Taken together, the results of the present study clearly show that malathion is cytotoxic and genotoxic in vitro, and its genotoxic effect is mediated by oxidative stress.

CONCLUSIONS

Overall, the present study demonstrated that higher concentrations of malathion induce cytotoxic and genotoxic effects to HepG2 cells. The induction of such cytotoxic and genotoxic effects can be associated with the formation of MDA, an end-product of lipid peroxidation. These findings suggest that oxidative stress plays an important role in malathion-induced cytotoxic and genotoxic damage in HepG2 cells. Nevertheless, malathion causes cellular proliferation and induces minimal DNA damage in HepG2 cells at low levels of exposure, providing clear evidence that low concentrations of this compound may be mitogenic.

Acknowledgments

This research was financially supported in part by the National Institutes of Health Grant No. 2G12RR13459-11 through the RCMI-Center for Environmental Health, and in part by the Department of the Army Cooperative Agreement No. W912HZ-04-2-0002, at Jackson State University.

References

- Ahmed RS, Seth V, Pasha ST, Banerjee BD. Influence of dietary ginger (Zinjiber officinales Rosc) on oxidative stress induced by malathion in rats. Food Chem Toxicol. 2000;38(5):443–450. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(00)00019-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhgari M, Abdollahi M, Kebryaeezaheh A, Hosseini R, Sabzevari O. Biochemical evidence for free radicalinduced lipid peroxidation as a mechanism for subchronic toxicity of malathion in blood and liver of rats. Human and Experimental Toxicology. 2003;22(4):205–211. doi: 10.1191/0960327103ht346oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ATSDR. Toxicological profile for arsenic (update) Agency for Toxic Substance and Disease Registry; Atlanta, GA: 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhanti M, Taneja A. Contamination of vegetables of different seasons with organophosphorus pesticides and related health risk assessment in northern India. Chemosphere. 2007;69(1):63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2007.04.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasiak J, Jaloszynski P, Trzeciak A, Szyfter K. In vitro studies on the genotoxicity of the organophosphorus insecticide malathion and its two analogues. Mutat Res. 1999;445(2):275–283. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5718(99)00132-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasiak J, Trzeciak A. Single cell gel electrophoresis (Comet Assay) as a tool for environmental biomonitoring. An example of pesticides. Polish Journal of Environmental Studies. 1998;7(4):189–194. [Google Scholar]

- Bonner M, Coble J, Blair A, Freeman L, Hoppin J, Sandler D, Alavanja M. Malathion exposure and the incidence of cancer in the agricultural health study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2007;166(9):1023–1034. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brocardo PS, Assini F, Franco JL, Pandolfo P, Muller YM, Takahashi RN, Dafre AL, Rodrigues AL. Zinc attenuates malathion-induced depressant-like behavior and confers neuroprotection in the rat brain. Toxicol Sci. 2007;97(1):140–148. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XY, Shao JZ, Xiang LX, Liu XM. Involvement of apoptosis in malathion-induced cytotoxicity in a grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus) cell line. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol. 2006;142(1–2):36–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta C, Gupta J, Sengupta D. Interaction of organophosphorus insecticides phosphamidon and malathion on lipid profile and acetylcholinesterase activity in human erythrocyte membrane. Indian J Med Res. 1994;100:87–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delescluse C, Ledirac N, de Sousa G, Pralavorio M, Lesca P, Rahmani R. Cytotoxic effects and induction of cytochromes P450 1A1/2 by insecticides, in hepatic or epidermal cells: binding capability to the Ah receptor. Toxicol Letters. 1998;96–97:33–39. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(98)00047-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado EH, Streck EL, Quevedo JL, Dal-Pizzol F. Mitochondrial respiratory dysfunction and oxidative stress after chronic malathion exposure. Neurochem Res. 2006;31(8):1021–1025. doi: 10.1007/s11064-006-9111-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortunato JJ, Agostinho FR, Reus GZ, Petronilho FC, Dal-Pizzol F, Quevedo J. Lipid peroxidative damage on malathion exposure in rats. Neurotox Res. 2006;9(1):23–28. doi: 10.1007/BF03033304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortunato JJ, Feier G, Vitali AM, Petronilho FC, Dal-Pizzol F, Quevedo J. Malathion-induced oxidative stress in rat brain regions. Neurochem Res. 2006;31(5):671–678. doi: 10.1007/s11064-006-9065-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover P, Danadevi K, Mahboob M, Rozati R, Banu BS, Rahman MF. Evaluation of genetic damage in workers employed in pesticide production utilizing the comet assay. Mutagenesis. 2003;18(2):201–205. doi: 10.1093/mutage/18.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwinn M, Whipkey D, Tennant L, Weston A. Differential gene expression in normal human mammary epithelial cells treated with malathion monitored by DNA microarrays. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2005;113(8):1046–1051. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haque N, Rizvi SJ, Khan MB. Malathion induced alterations in the lipid profile and the rate of lipid peroxidation in rat brain and spinal cord. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1987;61(1):2–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1987.tb01764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazarika A, Sarkar SN, Hajare S, Kataria M, Malik JK. Influence of malathion pretreatment on the toxicity of anilifos in male rats: a biochemical interaction study. Toxicology. 2003;185(1–2):1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(02)00574-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janero D. Malondialdehyde and thiobarbituric acid-reactivity as indices of lipid peroxidation and peroxidative tissue. Free Radical Bio Med. 1990;9:515–540. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(90)90131-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John S, Kale M, Rathore N, Bhatnager D. Protective effect of vitamin E in dimethioate and malathion induced oxidative stress in rat erythrocytes. J Nutr Biochem. 2001;12(9):500–504. doi: 10.1016/s0955-2863(01)00160-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: applications to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65 (1–2):55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muniz JF, McCauley L, Scherer J, Lasarev M, Koshy M, Kow YW, Nazar-Stewart V, Kisby GE. Biomarkers of oxidative stress and DNA damage in agricultural workers: a pilot study. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2008;227(1):97–107. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluth J, Nicklas J, O’Neill J, Albertini R. Increased frequency of specific genomic deletions resulting from in vitro malathion exposure. Cancer Research. 1996;56:2393–2399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reus GZ, Valvassori SS, Nuernberg H, Comim CM, Stringari RB, Padilha PT, Leffa DD, Tavares P, Dagostim G, Paula MM, Andrade VM, Quevedo J. DNA damage after acute and chronic treatment with malathion in rats. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56(16):7560–7565. doi: 10.1021/jf800910q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers KE, Grayson MH, Imamura T, Devens BH. In vitro effects of malathion and O, O, S-trimethyl phosphorothioate on cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses. Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology. 1985;24(2):260–266. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney M, Lyon M. Selective effect of malathion on blood coagulation versus locomotor activity. Journal of Environmental Pathology, Toxicology and Oncology. 1999;18(3):203–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobti RC, Krishan A, Pfaffenberger CD. Cytokinetic and cytogenetic effects of some agricultural chemicals on human lymphoid cells in vitro: organophosphates. Mutation Research. 1982;102:89–102. doi: 10.1016/0165-1218(82)90149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei M, Wanibuchi H, Yamamoto S, Li W, Fukushima S. Urinary bladder carcinogencitiy of dimethylarsinic acid in male F344 rats. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:1873–1876. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.9.1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarsan E, Tanyuksel M, Celik S, Aydin A. Effects of aldicarb and malathion on lipid peroxidation. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 1999;63:575–581. doi: 10.1007/s001289901019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yedjou CG, Moore P, Tchounwou PB. Dose- and time-dependent response of human acute promyelocytic leukemia (HL-60) cells to arsenic trioxide treatment. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2006;2:136–140. doi: 10.3390/ijerph2006030017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yedjou CG, Rodgers C, Brown E, Tchounwou PB. Differential effect of ascorbic acid and n-acetyl-L-cysteine on arsenic trioxide-mediated oxidative stress in human leukemia (HL-60) cells. J Biochem Molecular Toxicology. 2008;22(2):85–92. doi: 10.1002/jbt.20223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yedjou CG, Tchounwou PB. In vitro cytotoxic and genotoxic effects of arsenic trioxide on human leukemia (HL-60) cells using the MTT and alkaline single cell gel electrophoreis (comet) assays. Mol Cell Biochem. 2007;301:123–130. doi: 10.1007/s11010-006-9403-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]