Abstract

The protease that cleaves the most abundant non-collagenous protein of dentin matrix, dentin sialophosphoprotein (DSPP), into its two final dentin matrix products, dentin sialoprotein (DSP) and dentin phosphoprotein (DPP), has not been directly identified. In this study, full-length recombinant mouse DSPP was made for the first time in furin-deficient mammalian LoVo cells and used to test the ability of three different isoforms of one candidate protease, bone morphogenetic protein-1 (BMP1) to cleave DSPP at the appropriate site. Furthermore, two reported enhancers of BMP1/mTLD activity (procollagen C-endopeptidase enhancer-1, PCPE-1, and secreted frizzled-related protein-2, sFRP2) were tested for their abilities to modulate BMP1-mediated processing of both DSPP and another SIBLING family member with a similar cleavage motif, dentin matrix protein-1 (DMP1). Three splice variants of BMP1 (classic BMP1, the full-length mTolloid (mTLD), and the shorter isoform lacking the CUB3 domain, BMP1-5) were all shown to cleave the recombinant DSPP in vitro although mTLD was relatively inefficient at processing both DSPP and DMP1. Mutation of the MQGDD peptide motif to IEGDD completely eliminated the ability of all three recombinant isoforms to process full-length recombinant DSPP in vitro thereby verifying the single predicted cleavage site. Furthermore when human bone marrow stromal cells (which naturally express furin-activated BMP1) were transduced with the adenovirus-encoding either wild-type or mutant DSPP, they were observed to fully cleave wild-type DSPP but failed to process the mutant DSPPMQΔIE during biogenesis. All three BMP1 isoforms were shown to process type I procollagen as well as DSPP and DMP1 much more efficiently in low salt buffer (≤50 mM NaCl) compared to commonly used normal saline buffers (150 mM NaCl). Neither PCPE-1 nor sFRP2 were able to enhance any of the three BMP1 isoforms in cleaving either DSPP or DMP1 under either low or normal saline conditions. Interestingly, we were unable to reproduce sFRP2’s reported ability to enhance the processing of type I procollagen by BMP1/mTLD. In summary, three isoforms of BMP1 process both DSPP and DMP1 at the MQX/DDP motif, but the identity of a protein that can enhance the cleavage of the two SIBLING proteins remains elusive.

Keywords: DSPP, DMP1, BMP1, mTLD, PCPE-1, sFRP2

1. Introduction

The SIBLING1 (Small Integrin-Binding LIgand, N-linked Glycoprotein) family is comprised of five tandem genes encoding osteopontin (OPN), matrix extracellular phosphoprotein (MEPE), bone sialoprotein (BSP), dentin matrix protein-1 (DMP1), and dentin sialophosphoprotein (DSPP) (Fisher et al., 2001). Although originally thought to be associated only with the mineral compartments of bones and teeth, all five members have subsequently been found to also be made in specific soft tissues including metabolically active ductal epithelial cells (e.g., salivary gland and kidney) as well as in many different types of human cancer (for review see (Bellahcene et al., 2008). All human SIBLINGs contain the integrin-binding tripeptide, RGD, and most appear to be cleaved into well-defined fragments by specific proteases. OPN, for example, is cleaved by thrombin at a site carboxy-terminal to the RGD domain, an event that is reported to uncover additional, cryptic binding sites for integrins α9β1, α4β1, and α4β7 (Barry et al., 2000; Bayless et al., 1998; Green et al., 2001; Smith et al., 1996; Yokosaki et al., 1999). The most abundant noncollagenouse matrix proteins found in dentin, dentin sialoprotein (DSP) and dentin phosphoprotein (DPP, also known as dentin phosphophoryn), are known from genomic evidence to be encoded by the single gene, DSPP (MacDougall et al., 1997; Ritchie and Wang, 1997), starting a search for the protease that processes the protein into these two well-defined proteins. Qin and colleagues (Qin et al., 2004) proposed that the cleavage on the amino-terminal side of the Asp bond for both DMP1 and DSPP could have been by a protease encoded by PHEX (phosphate-regulating gene with homologies to endopeptidases on X chromosome). However, the proteases for DMP1 cleavage were shown by Steiglitz et al. (Steiglitz et al., 2004) to be members of the BMP1/Tolloid family of metalloproteinases. Due to the similarity of the DMP1-cleavage motif (MQS/DDP) with the one predicted in DSPP from the known amino-terminus of DPP (MQG/DDP), Steiglitz and coworkers (Steiglitz et al., 2004) logically hypothesized that this family would also cleave DSPP but the inability to purify intact full-length DSPP from dentin or to make full-length recombinant DSPP has hindered the appropriate studies.

Due to their ability to bind to many calcium ions, the two phosphorylated dentin matrix proteins have long been thought to be involved in the biomineralization of the dentin matrix. Indeed, mice lacking both Dspp alleles have mineralization defects in their dentin (Sreenath et al., 2003). Expression of the DSP domain alone only partially rescued the mouse tooth phenotype (Suzuki et al., 2009). Furthermore, all known nonsyndromic genetic diseases of human dentin exclusively involve the DSPP gene (Barron et al., 2008; McKnight et al., 2008). Although none of the currently published disease-causing mutations of DSPP involve the proposed BMP1 cleavage motif, we have recently noted that the motif is conserved among all 21 mammals (plus one reptile) studied to date (McKnight and Fisher, 2009) suggesting that some patients in the future diagnosed with dentin disease may have mutations in this highly conserved region. Recently it has also been shown that the expression of DSPP in prostate cancer (Chaplet et al., 2006) and oral premalignant lesions (Ogbureke et al. Cancer, in press 2010) serves as useful marker for tumor aggressiveness and progression respectively. These observations raise a wider interest in the regulation of DSPP biosynthesis including questions about which proteases as well as enhancing/inhibiting proteins may be involved in the processing of DSPP in dentin as well as in other tissues.

In recent years, the family of BMP1/Tolloid metalloproteinases has been shown to play key functions in morphogenesis as well as the formation of extracellular matrices in many diverse species through their abilities to activate several important bioactive proteins and in the processing of a variety of precursors into mature extracellular matrix proteins. For example, Tolloids possess procollagen C-proteinase (PCP) activity whereby they remove the C-propeptides of the three major fibrillar procollagens (type I, II, and III) in preparation for fibrillogenesis. Other examples of BMP1/Tolloid substrates include: several members of the TGFβ superfamily; the bone morphogenetic protein antagonist, chordin; prolysyl oxidase; biglycan; osteoglycin; procollagen V, VII, XI; and laminin-5 (γ2 chain) (for review see (Hopkins et al., 2007)). In mammals, there are three Tolloid proteinase-encoding genes. Bone morphogenetic protein-1 (BMP1 also known as splice variant BMP1-1) was the first member to be identified in higher vertebrates. BMP1was originally purified from the osteogenic extracts of bone (Wozney et al., 1988) and turned out to be a protease rather than a true morphogenetic protein. Later it was proposed to activate the other members of the BMP family (Kessler et al., 1996; Li et al., 1996). Mammalian Tolloid (mTLD) was discovered to be an ortholog of the Drosophila Tolloid protease and the longest splice variant (BMP1-3) of the BMP1 gene (Takahara et al., 1994b). A total of six BMP1 splice variants have been described. BMP1-2 (BMP1/His) variant was found to have the last domain of BMP1-1 substituted by a longer, histidine-rich domain (Takahara et al., 1994b) and later three additional splice variants of the BMP1 gene were identified (BMP1-4, BMP1-5, and BMP1-6) (Janitz et al., 1998). Two other genes encode additional Tolloid-like proteinases in vertebrates; mammalian Tolloid like-1 (mTLL1) and -2 (mTLL2) (Scott et al., 1999; Takahara et al., 1996). All Tolloids contain a signal peptide, a prodomain (which must be removed by furin or furin-like proteases to produce an active protease, (Leighton and Kadler, 2003)), and an astacin-like metalloproteinase domain. The splice variants of BMP1 involve combinations of carboxy-terminal CUB (complement, Uegf, and BMP1) and EGF-like domains with each variant ending in a C-terminal sequence-specific domain (Hopkins et al., 2007). The non-catalytic domains have been suggested to involve substrate specificity and thereby enzyme efficiency. For example, BMP1 and mTLL1 but neither mTLD nor mTLL2 cleave chordin, whereas all four were shown to have some level of PCP activity with BMP1 showing the highest and mTLL2 the lowest levels (Berry et al., 2009; Garrigue-Antar et al., 2004; Pappano et al., 2003; Petropoulou et al., 2005; Scott et al., 1999; Wermter et al., 2007). Mammalian TLL2 was similarly found to have lower activity against DMP1 in comparison with BMP1, mTLD, or mTLL1 (Steiglitz et al., 2004). The actual cleavage efficiency of the isoform lacking the CUB 3 domain, BMP1-5, on DMP1 or other substrates is not known.

Like many other known protease networks, the PCP activity of BMP1-1/Tolloids on fibrillar procollagens can be enhanced by a family of secreted proteins, procollagen C-endopeptidase enhancers (PCPE-1 and PCPE-2) (Kessler et al., 1986; Steiglitz et al., 2002; Xu et al., 2000). These proteins were reported to be devoid of intrinsic enzymatic activity and are thought to function via a direct interaction with their procollagen substrates (Blanc et al., 2007; Kessler and Adar, 1989; Kessler et al., 1996; Moali et al., 2005; Moschcovich et al., 2001; Ricard-Blum et al., 2002; Takahara et al., 1994a). Recent data suggested that the secreted frizzled-related protein-2 (sFRP2), an important extracellular regulator of Wnt signaling, can also act as an endogenous enhancer of PCP activity (Kobayashi et al., 2009). The mechanism of this enhancement was proposed to involve formation of trimeric complexes (composed of the protease, the substrate, and sFRP2), a complex reminiscent of that observed for PCPE-1. Interestingly Szl, another member of the secreted frizzled-related protein family, has been reported to act as a competitive inhibitor of the TLD-like proteinase cleavage of both frog and zebrafish chordin as well as of a synthetic peptide substrate that resembles a procollagen C-propeptide cleavage site (Lee et al., 2006). It has also been reported that mouse sFRP2 can inhibit the cleavage of frog chordin by the Xenopus TLD-like proteinase, Xlr (Lee et al., 2006).

In this paper, we generated recombinant normal and mutant full-length DSPP in furin-deficient mammalian cells to address the question of whether three different isoforms of BMP1 could cleave this SIBLING as well as another member of the family, DMP1, into their well-known fragments. Furthermore, two reported enhancers of BMP1/mTLD, PCPE-1 and sFRP2, were tested to see if they enhanced the extracellular processing of DSPP and DMP1.

2. Results

2.1. Three BMP1 isoforms cleave DSPP at MQG/DDP motif

The two most abundant non-collagenous proteins in dentin, the amino-terminal dentin sialoprotein (DSP) and the carboxy-terminal dentin phosphoprotein (DPP), are the result of a single cleavage of the full-length DSPP gene product. Because another SIBLING family member, DMP1, was previously shown to be cleaved by the family of BMP1/Tolloid-like metalloproteinases at a MQXDD motif, DSPP was predicted to be processed by the same protease family at its similar motif. To test this hypothesis, we made a replication-deficient adenovirus that resulted over expression of full-length mouse DSPP message utilizing the cytomegalovirus promoter. Unlike other SIBLING proteins, DSPP appeared to be cytotoxic and only small amounts of recombinant DSPP-related products were found after infection of a number of different cell types in vitro. Furthermore, for all cell lines first tried, only the DSP and DPP breakdown products were recovered in the media (data not shown). This was likely due to the nearly ubiquitous expression of various members of the BMP1/Tolloid-like metalloproteinases in cells. Since all BMP1/Tolloid-like metalloproteinases require activation by furin-related proteases, we tried two different cell lines that were known to be deficient in furin-like activity. The Chinese hamster ovary furin-deficient (CHO-FD11) cells (Gordon et al., 1995) were observed by Western blot to produce BMP1 retaining its inhibitory propeptide but adenovirally induced expression of DSPP in these cells was found to be insufficient (data not shown). Fortunately, the LoVo human colon cancer cell line (known to posses two inactivating mutations in the furin gene, (Takahashi et al., 1993; Takahashi et al., 1995)) was found to be more useful. Transduction of LoVo cells with the DSPP-encoding adenovirus enabled us to obtain, under serum-free conditions, full-length DSPP protein (DSPPwt) in sufficient amounts to immunodetect by Western blot (Fig. 1A).

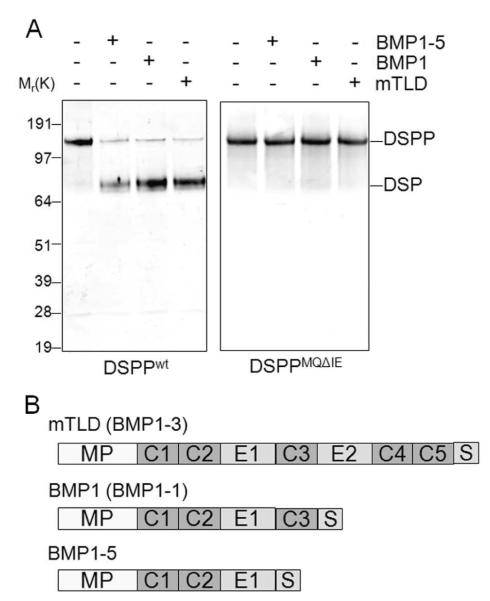

Fig.1.

Mutation of the Met-Gln to Ile-Glu in DSPP’s proposed BMP1-cleavage site completely prevented its processing by all three isoforms of BMP1. A. Recombinant wild-type DSPPwt and mutant protein DSPPMQΔIE were incubated 21 h at 37 °C in low-salt reaction buffer (25 mM HEPES, 10 mM NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2, 0.01% Brij) alone or in the presence of the indicated BMP1 isoforms. Samples were electrophoresed on a SDS 4-12% NuPAGE gel, transferred to a PVDF membrane, and immunodetected with anti-DSP domain (LF-153) as detected by fluorescent second antibody and monitored on the Li-COR Odyssey Imager. Note that DSPPwt was processed by all three BMP1 isoforms while DSPPMQΔIE was not. Left side numbers indicate the location of molecular weight standards (in kDa). B. Schematic illustrating the domain structures of the three mature BMP1 isoforms used in this study. Domains are as follows: MP, metalloproteinase catalytic domain; C1-C5, CUB domains; E1-E2, EGF-like domains; S, isoform-specific regions.

Recombinant mTLD and BMP1 as well as the short isoform lacking the CUB3 domain (BMP1-5, Fig. 1B), all cleaved the ion-exchange column-enriched, full-length recombinant mDSPP (~160,000 Mr) into the ~85,000 Mr DSP fragment during an extended digestion time period (21 h) as seen in Fig. 1A. Unfortunately, due to cytotoxicity of DSPP expression, the amounts of DPP made were not sufficient for clear Stains-All detection or direct protein sequencing. Since the lack of an antibody against mouse DPP kept us from directly observing the production of this second digestion product, we constructed a variant of the full-length DSPP in which the predicted cleavage motif, MQGDD, was changed to IEGDD. As seen in Fig. 1A, all three isoforms of BMP1 were completely unable to cleave the mutant DSPPMQΔIE product in vitro, supporting the hypothesis that BMP1 metalloproteinases cleave one time only and precisely at the DMP1-like MQXDD motif. Furthermore, because only full-length DSPPMQΔIE was obtained from medium of transduced hBMSC (cells that we have found to 1) express BMP1, 2) make a modest fibrillar type I collagen matrix, as well as 3) possessing an innate ability to process recombinant DMP1, (von Marschall and Fisher, 2008), the mutant DSPPMQΔIE was proven to be also resistant to endogenous proteases.

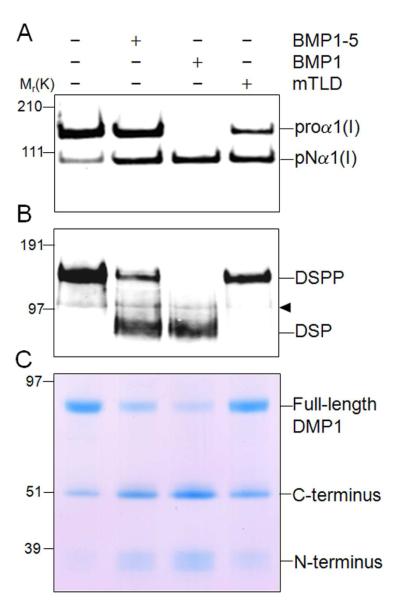

Having shown that all three tested BMP1 isoforms exhibited the ability to cleave wild-type DSPP during a prolonged incubation time, we next conducted shorter experiments to gain insight into the relative efficiency of the isoforms to digest DSPP. Because the absolute activity of the three isoforms could not be accurately determined using these reagents, we compared to their abilities to digest DSPP and DMP1 relative to their ability remove the C-propeptides of type I procollagen. Fig. 2A shows that under these specific reaction conditions and using a fixed amount of each of the three recombinant BMP1 isoforms, BMP1 was the most efficient at removing the C-propeptide of procollagen while both the full-length mTLD and the BMP1-5 isoforms were less efficient. Using the same relative amounts of the three recombinant BMP1 isoforms, BMP1 was also the most efficient enzyme in cleaving both DSPP (Fig. 2B) and DMP1 recombinant proteins (Fig. 2C). Unlike the processing of procollagen C-propeptide in which both BMP1-5 and mTLD were approximately equally affective proteases, mTLD was not able to efficiently process either SIBLING protein while the isoform lacking the CUB-3 domain, BMP1-5, was of intermediate effectiveness. Together these results show that relative to their effectiveness in removing the C-propeptides of type I procollagen, mTLD is much less effective than the two shorter isoforms in cleaving both acidic SIBLINGs.

Fig. 2.

Compared to their respective PCP activities, BMP1 isoforms exhibit differential effectiveness in cleaving both DSPP and DMP1. Type I procollagen, DSPP, and DMP1 were incubated for 1h at 37 °C alone or in the presence of the same relative amounts of either BMP1-5, or BMP1 (BMP1-1), or mTLD (BMP1-3) in low-salt reaction buffer (25 mM HEPES, 10 mM NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2, 0.01% Brij). Samples were then electrophoresed on the appropriate polyacrylamide gel, transferred to membranes when necessary, and detected with (A) antibody against the human collagen α1(I) amino-propeptide (LF-39), (B) antibody against the DSP portion of DSPP (LF-153), or (C) stained with Stains-All to detect DMP1/fragments. Note the differential loss of proα1(I) bands (with concurrent increase in pNα1(I) bands) with BMP1 being the most effective, followed by mTLD, and then BMP1-5(A). Note that BMP1 was the most effective isoform to cleave both DSPP (B) and DMP1 (C), while mTLD (BMP1-3) was ineffective, and BMP1-5 was of intermediate activity. Left side numbers indicate the approximate molecular weights in kDa for relevant prestained standards within each specific gel type. The arrowhead indicates a false-positive protein band variably detected in some preparations of LoVo-derived media on Western blots by the LF-153 antibody. (Note that as would be expected for a false-positive DSPP band, it is not affected by any BMP1 protease.)

2.2. SFRP2 does not enhance DSPP and DMP1 processing by three BMP1 isoforms

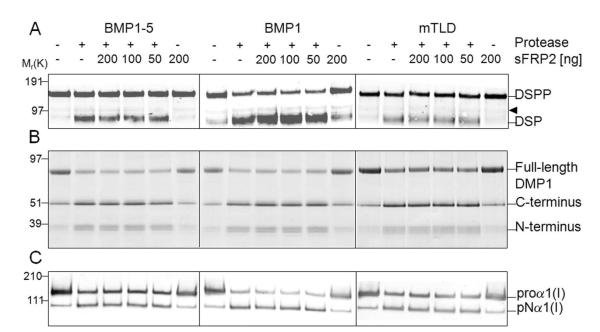

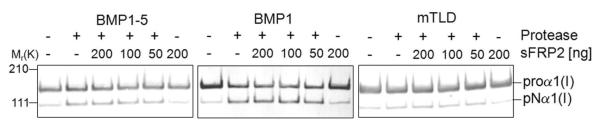

Recent studies showed that Szl, a member of the secreted frizzled-related proteins (sFRP) might act as a competitive inhibitor in Tolloid’s cleavage of the BMP-inhibiting protein, chordin, in frog and zebrafish (Lee et al., 2006). In contrast, the mammalian sFRP2 was shown to not affect chordin processing, but instead to act as a direct if weak enhancer of procollagen C-endopeptidase activity of BMP1 (Kobayashi et al., 2009). Therefore, experiments were conducted to study whether sFRP2 could modulate the BMP1-mediated processing of DSPP and DMP1. First, our commercial source of recombinant sFRP2 was found to have potent biological activity in a Wnt3a-LEF/TCF/luciferase reporter assay (data not shown). Next, the effect of sFRP2 on BMP1-1, mTLD (BMP1-3), and BMP1-5 mediated processing of DSPP and DMP1 was examined. As shown in Fig. 3A and 3B respectively, none of the three BMP1 isoforms were either substantially inhibited or enhanced in their cleavage of DSPP or DMP1 substrates under our standard, low-salt conditions. In contrast to the previous report that the same commercial source and range of concentrations of recombinant mammalian sFRP2 enhanced the removal of the C-propeptides of type I procollagen by BMP1 (Kobayashi et al., 2009), we did not find any obvious differences in this assay with addition of sFRP2 to BMP1, mTLD, or BMP1-5 (representative results shown in Fig. 3C). To see if minor changes in buffer conditions could explain this unanticipated result, additional experiments were performed as described below.

Fig. 3.

Secreted frizzled-related protein-2 (sFRP2) does not enhance SIBLINGs processing by BMP1 isoforms nor does it enhance their PCP activities. DSPP (A), DMP1 (B) and type I procollagen (C) samples were incubated for 2 h at 37 °C in low-salt reaction buffer (25 mM HEPES, 10 mM NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2, 0.01% Brij) in the presence of the same amounts (relative to that used for their respective PCP activities) of each isoform and indicated amounts of recombinant sFRP2. Samples without proteases and samples containing only sFRP2 were used as controls. Completed reactions were electrophoresed and detection was performed as described above in Methods. Shown are representative immunoblots for DSPP (A) and type I procollagen (C) as well as a representative Stains-All staining used to detect DMP1. Note that all BMP1 isoforms cleave each substrate but the addition of 50, 100 or 200 ng sFRP2 (12.5, 25 and 50 nM, respectively) did not enhance or inhibit their proteolytic effectiveness. The arrowhead indicates a false-positive protein band variably detected in some preparations of LoVo-derived media on Western blots by the mouse DSP antibody. Left side numbers indicate the approximate molecular weights in kDa for relevant prestained standards.

2.3. Salt concentration affects BMP1 isoform’s PCP efficacy

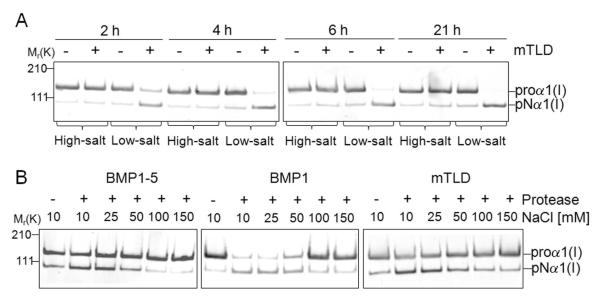

The documentation accompanying our commercial source of BMP1 (BMP1-1) suggested conducting peptide-based assays under low salt conditions. We found that while BMP1’s PCP activity was lost during dialysis and storage under such low salt conditions (data not shown), it did result in much more efficient short-term reactions compared to the higher saline conditions (Tris-buffered saline) used in the previously published results (Kobayashi et al., 2009). Using mTLD as a representative example, its PCP activity in low salt (25 mM HEPES buffer containing 5 mM CaCl2 and 0.02% Brij) was compared with the previously described ”high” salt buffer (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2). As shown in Fig. 4A, the type I procollagen C-propeptide was effectively processed by mTLD in a time-dependent manner under low-salt conditions whereas the same amount of the enzyme resulted in almost no processing under high-salt conditions even with the incubation time extended to 21 hours. To more fully document the effects of sodium chloride concentrations that best supported the PCP activity for each isoform, the processing of procollagen was studied under increasing concentrations of the saline component. As shown in Fig. 4B, all three isoforms worked best under low-salt conditions (10-50 mM NaCl) with dose-dependent decreases in activity noted at concentration higher than 50 mM NaCl in the HEPES buffer. To address that the lack of PCP-enhancing activity of sFRP2 in our study might have been due to different assay conditions, the experiments were repeated in buffers with 150 mM saline conditions that duplicated the apparent assay conditions described by Kobayashi and colleagues (Kobayashi et al., 2009). However, as shown in representative Western blots (Fig. 5), sFRP2 in our hands continued to fail to enhance the PCP activity of all three tested isoforms of BMP1 even in the normal saline environment.

Fig. 4.

The three BMP1 isoforms cleave human type I procollagen in a salt-dependent manner. A. Type I procollagen samples were incubated for noted times with mTLD (BMP1-3) in low-salt (25 mM HEPES, 10 mM NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2, 0.01% Brij) or high-salt (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2) reaction buffers. Samples collected after 2, 4, 6, and 21 h were electrophoresed with SDS on a 3-8% Tris-acetate NuPAGE gels followed by immunoblotting with antibody against the human collagen α1(I) amino-propeptide (LF-39). Note that the same amount of mTLD in low-salt conditions processes much more procollagen in shorter periods of time than it does in normal saline. B. Type I procollagen samples were incubated separately with BMP1-5, BMP1, and mTLD under increasing NaCl concentration for 1 h at 37 °C before being subjected to immunoblotting with LF-39 antibody. Immunoblots demonstrate dose-dependent decrease in enzymatic activity by all three BMP1 isoforms as the salt concentration reached concentrations above ~50-100 mM NaCl. Left side numbers indicate the approximate molecular weights in kDa for relevant prestained standards.

Fig. 5.

Secreted frizzled-related protein-2 (sFRP2) does not enhance the PCP activity of the three BMP1 isoforms in normal saline conditions. Type I procollagen was incubated at 37 °C for 21 h alone or with each of the three BMP1 isoforms plus 50, 100, and 200 ng sFRP2 (~ 12.5, 25, and 50 nM, respectively) under the normal saline conditions (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2) reported earlier (Kobayashi et al., 2009). The processing of type I procollagen (proα1(I)) into pNα1(I) bands was detected by means of Western blot using antibody against the human collagen α1(I) amino-propeptide (LF-39). Representative immunoblots show that increasing sFRP2 concentrations have no effect on any BMP1 isoform’s processing of type I procollagen even in normal saline (high-salt) conditions previously reported. Left side numbers indicate the approximate molecular weights in kDa for relevant prestained standards.

2.4. PCPE-1 enhances the PCP activity of BMP1 isoforms but has no effect on cleavage of DSPP and DMP1

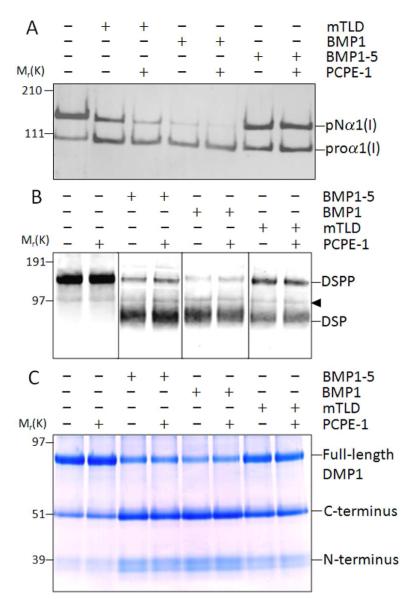

To verify that we could observe at least one protein enhancing the BMP1/mTLD activity in our experimental conditions, we also produced recombinant PCPE-1 in primary hBMSC by means of adenoviral gene transduction. Western blot analysis of this serum-free conditioned medium using an anti-PCPE-1 antibody showed the presence of a single immunoreactive protein at the expected size for PCPE-1 of approximately 50 kDa (data not shown). PCPE-1 is an accessory protein well documented to enhance the ability of BMP1 to remove the C-propeptides of type I procollagen. As shown in Fig. 6A, the C-propeptides of type I procollagen were partially removed by BMP1 and mTLD under these specific experimental time/conditions and the addition of recombinant PCPE-1 further increased the extent of the processing. The BMP1-5-mediated processing was less effective under these conditions and, at best, was only slightly increased as indicated by the decrease in proα1(I) band density after the addition of PCPE-1. These results confirm that our source of PCPE-1 had the expected PCP-enhancing activity. To address the question whether PCPE-1 has any effect on DSPP and DMP1 processing by three isoforms of BMP1, the recombinant human PCPE-1 was used in similar doses in digestions of DSPP (Fig. 6B) and DMP1 (Fig. 6C) for each of the three BMP1 isoforms. PCPE-1 had no enhancing or inhibitory affects on the in vitro cleavage of either DSPP or DMP1 by any of the three BMP1 isoforms.

Fig. 6.

Cleavage of DSPP and DMP1 by BMP1 isoforms is not enhanced by PCPE-1. Type I procollagen (A), DSPP (B), and DMP1 (C) samples were incubated alone or separately with BMP1-5, BMP1, or mTLD (BMP1-3) for 2 h with or without PCPE-1 in low-salt reaction buffer (25 mM HEPES, 10 mM NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2, 0.01% Brij) before electrophoresis on their appropriate gels (see methods). The processing of type I procollagen (proα1(I)) into pNα1(I) bands was detected by means of Western blot using antibody against the human collagen α1(I) amino-propeptide (LF-39). Intact DSPP and DSP cleavage fragments were detected by Western blot using anti-DSP antibody described in Fig. 1 whereas the DMP1 and its cleavage products were directly visualized in the gel with Stains-All. Shown are representative results. Note that the processing of procollagen by both BMP1 and mTLD (BMP1-3) is enhanced by PCPE-1 while the reaction using BMP1-5 is not affected. The processing of both SIBLINGs by BMP1 isoforms is unaffected by PCPE-1. The arrowhead indicates a false-positive protein band variably detected in some preparations of LoVo-derived media on Western blots by the LF-153 antibody. Left side numbers indicate the approximate molecular weights in kDa of relevant prestained standards for each gel type.

3. Discussion

DSPP, particularly the DPP domain, is perhaps the most highly phosphorylated and most acidic protein produced by mammals. The biosynthesis, packaging, and secretion of this calcium-binding protein may present a considerable challenge to any cells programmed to produce it because it can logically be expected to gel or form a precipitate in the relatively high calcium ion environment of organelles such as the rough endoplasmic reticulum (rER). Although DSPP can be detected in metabolically active ductal epithelial cells, only the dentin-synthesizing odontoblasts may produce DSPP in large quantities. In contrast to the other acidic SIBLING proteins, our laboratory has had considerable difficulty expressing significant amounts of full-length human and mouse DSPP (or their DPP corresponding fragments) even after transducing a variety of different cell types in culture. We have had more success expressing the human DSPP when all but a few copies of the phosphorylation motifs of the DPP domain were deleted (de Vega et al., 2007) suggesting that the many tandem repeats of the SerSerAsp phosphorylation motif (from ~75 in elephant, to ~120 in mouse, and >240 in human, (McKnight and Fisher, 2009) are the problematical aspects of the protein. These observations suggest that the DSP domain could play an important role in the biosynthesis and/or trafficking of the DPP domain. A corollary hypothesis is that once the DPP is safely made and delivered to the pericellular or extracellular environment, it may perform its extracellular functions more effectively if the DSP domain is separated from the DPP. When the deduced sequence of the full-length DSPP protein was reported (MacDougall et al., 1997; Ritchie and Wang, 1997), the cleavage site of the intact DSPP protein into its two well-known components (DSP and DPP) was hypothesized, but the protease that cleaved at the MQG/DDP site was not known. Because another SIBILNG protein, DMP1, was shown to be cleaved at a similar motif (MQSDDP) by members of the BMP1/Tolloid family (Steiglitz et al., 2004), this small family of metalloproteinases was the obvious candidate to perform this function in DSPP. As discussed in the introduction, the BMP1 family currently includes various splice variants of three genes (BMP1, mTLL1, and mTLL2) and is involved with the processing of an ever-growing list of secreted matrix and bioactive proteins (Hopkins et al., 2007). There is also a growing body of literature showing that these critical proteases work in balance with both enhancing and inhibitory proteins.

We purchased recombinant BMP1 (BMP1-1) and also made adenoviral constructs encoding the full-length splice variant, mTolloid (mTLD, BMP1-3), as well as a short isoform that lacked the CUB3 domain, BMP1-5. The effects of this latter, short isoform on DSPP and DMP1 is of particular interest as this isoform was found to be the predominant splice variant of the BMP1 gene in kidney (Janitz et al., 1998), a tissue that also expresses DSPP and DMP1 (Ogbureke and Fisher, 2005). As expected from the previous literature (Kessler et al., 1996; Li et al., 1996; Pappano et al., 2003; Scott et al., 1999), all three of our recombinant isoforms removed the C-propeptides from type I procollagen in our in vitro assays. Furthermore, recombinant PCPE-1 substantially enhanced this activity for both BMP1 and mTLD but not for the isoform lacking the CUB3 domain, BMP1-5. Petropoulou et al. (Petropoulou et al., 2005) reported that removal of the CUB3 domain from BMP1 resulted in the decreased ability of PCPE-1 to enhance the removal of the type I collagen C-propeptides. Our results with BMP1-5, the splice variant naturally lacking this CUB3 domain, support this observation although these two protein constructs do also have different carboxy-terminal domains. Secreted frizzled-related protein-2 (sFRP2) was first reported to be an inhibitor of the Xenopus TLD-like proteinase Xlr (Lee et al., 2006) and then later it was described to enhance BMP1-1 activity on type I procollagen (Kobayashi et al., 2009). In our assays, however, sFRP2 did not enhance the type I procollagen PCP activity for any of the three recombinant BMP1 isoforms. One possible explanation for this unexpected result was our specific reaction conditions, so experiments were performed to test this hypothesis. We found that while BMP1 isoforms were more stable when stored in buffer with normal (150 mM) saline salt concentrations, all three enzymes digested substrates much more effectively in low salt (≤50 mM NaCl) conditions. Each isoform became much less efficient at final concentrations of NaCl above ~100 mM. In our hands however, the sFRP2 (which did exhibit activity in a Wnt3a/Luciferase assay) remained inactive’ in our PCP assay even under conditions identical to those reported in the original publication. Eventually these types of experiments should be repeated with all highly purified protein components in carefully controlled buffer conditions to finally decide the role of sFRP2 in the BMP1/Tolloid protease network.

In the serum-free conditioned media of normal human bone marrow stromal cells (fibroblasts) transduced with an adenoviral construct to express wild-type mouse DSPP, we typically found most of the DSPP cleaved into the expected fragments as judged by the presence of the DSP-immunoreactive band of the expected size detected using an antibody (LF-153) made against a portion of the mouse DSP domain produced in E. coli (Ogbureke and Fisher, 2004). Note that this same antibody was shown in Western blots to be non-reactive to tooth extracts of Dspp-null mice while detecting one major and several minor DSP-related bands in the tooth extracts of heterozygotic (+/−) littermates (Suzuki et al., 2009). The several DSP-related Western blot bands in dentin extracts are likely due to subsequent proteases such as MMP-2 and MMP-20 proposed by Yamakoshi et al. (Yamakoshi et al., 2006). In contrast, when we transduced furin-deficient LoVo cells (which do not activate BMP1 family members) with the same DSPP construct and analyzed the conditioned media, we detected the intact DSPP. Over extended incubation times, all three recombinant isoforms of BMP1 were able to cleave this anion exchange-enriched, intact DSPP and produce an immunodetectable band of a size expected for DSP. Because we do not have an antibody that detects the mouse DPP fragment on Western blots, this corresponding fragment was not directly detected. To overcome this shortfall, we made a second DSPP adenovirus in which we changed the MQGDDP motif to IEGDDP, a modification similar to what has been shown to negate the ability of BMP1 to cleave DMP1 in vitro and in vivo (von Marschall and Fisher, 2008). This permitted the production of a full-length DSPPMQΔIE protein even in normal hBMSC known to produce active BMP1 and to be able to cleave all recombinant DSPPwt protein biosynthesized. Furthermore, all three recombinant BMP1 isoforms were unable to cleave the same anion exchange-purified DSPPMQΔIE protein in vitro even over extended digestion times. Thus, these results show that furin-activated BMP1 family members cleave DSPP at the predicted MQG/DDP site. The lack of any observed lower molecular weight bands on the DSPPMQΔIE Western blot strongly suggests that the DPP domain must logically remain intact in the wild-type DSPP cleavage event even though our lack of an antibody against mouse DPP kept us from directly observing the production of this second digestion product.

While the specific activity of the three recombinant BMP1 isoforms was not sufficiently well defined to denote their absolute efficiencies in the digestion of DSPP and its SIBLING relative, DMP1, we were able to compare their activities relative to their abilities to remove the C-propeptides from type I procollagen in vitro. BMP1 and BMP1-5 isoforms cleaved both DSPP and DMP1 about as well as they had processed type I procollagen. This suggests that the CUB3 domain (missing in BMP1-5) is not critical for the binding and/or processing of these two acidic SIBLINGs. In contrast, the full-length mTLD (BMP1-3) was ineffective in processing either of the two SIBLINGs within the brief digestion period suggesting that mTLD acting alone is not an efficient protease for processing DSPP or DMP1. Berry et al. (Berry et al., 2009) have recently shown that mTLD uses its additional EGF-like 2 domain to form calcium ion-dependent homodimers which, through substrate exclusion mechanisms, may keep the enzyme from cleaving some substrates. Together these results suggest that the proposed dimerized mTLD alone cannot interact efficiently with either DSPP or DMP1 substrates. Because BMP1-related isoforms, particularly BMP1-5, have been reported to be transcribed in the kidney (Janitz et al., 1998) and we have observed BMP1 immuno-expression in salivary gland ducts (data not shown), it is reasonable to hypothesize that DSPP and DMP1 may also be processed into their respective fragments when expressed in ductal epithelial tissues such as kidney and salivary glands although future experiments involving direct analysis of soft tissue extracts must be performed to prove this point.

In our hands, full-length recombinant DSPP remained intact in LoVo culture media as well as for 21 h at 37 °C in low salt conditions after ion exchange chromatography enrichment. In contrast to this, Godovikova and Ritchie (Godovikova and Ritchie, 2007) previously noted a DSPP-related construct made in insect cells undergoing a spontaneous cleavage event (“dynamic processing”) at the MQG/DDP motif within 30 minutes, reportedly without the benefit of any co-purified proteases. Because the three other acidic SIBLINGs (BSP, OPN, and DMP1) have been shown under certain conditions to co-purify with specific matrix metalloproteinases MMP-2, MMP-3 and MMP-9, respectively (Fedarko et al., 2004), future experiments can be envisioned in which insect cell BMP1/Tolloid-related or other proteases are tested for their ability to bind (and co-purify with) polyacidic DPP-like phosphoproteins.

Like many proteases, the BMP1/Tolloid family has its activity modulated by enhancing cofactors. PCPE-1 has been shown to enhance the ability of BMP1 isoforms to remove the C-propeptides of type I procollagen, an effect we also observed in our experiments. Neither DSPP nor DMP1, however, were more efficiently digested into their respective fragments upon addition of PCPE-1 under either low or normal saline conditions. This adds the acidic DMP1 and DSPP proteins to the growing list of proteins (e.g., type VII procollagen, laminin, osteoglycin, prolysyl oxidase, and chordin) whose BMP1-related cleavage is not accelerated by PCPE-1 (Moali et al., 2005). Secreted frizzled-related protein-2 (sFRP2) also had no effect on the processing of DSPP or DMP1 under our experimental conditions. In our laboratory we have noticed that DMP1, which can be made in significantly larger quantities than DSPP in transduced cells, is much more efficiently processed into its two BMP1-cleaved fragments during biosynthesis compared to our use of purified recombinant proteins. While this may be due solely to the more favorable buffer/salt/pH conditions within the cell’s processing microenvironment, it is also possible that another BMP1/Tolloid family activity-enhancing protein will eventually be identified in cells such as odontoblasts that can accelerate the processing of DMP1 and DSPP into their well-known and presumably bioactive fragments. One possibility for future studies is procollagen C-endopeptidase enhancer-2 (PCPE-2) protein because, unlike PCPE-1, PCPE-2 has recently been shown to enhance the BMP1 family’s ability to digest a non-fibrillar collagen substrate. The authors show that PCPE-2 accelerated the proteolytic processing of pro-apolipoprotein AI (apoAI) by BMP1 through the stabilization of the protease-substrate complex (Zhu et al., 2009).

In summary, three isoforms of BMP1/mTLD have been shown to cleave intact DSPP at the hypothesized MQGDDP motif although at different efficiencies. The enhancer protein that can accelerate this process for the two acidic SIBLING proteins, if any exist, remains elusive at this time.

4. Materials and methods

4.1. Cell culture

The human colorectal carcinoma cell line, LoVo, was obtained from ATCC (catalog # CCL-229; Manassas, VA) and propagated in F-12K medium (ATCC) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Atlanta Biologicals, Lawrenceville, GA). The human embryonic kidney 293A (HEK293A) cell line was obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) and was maintained in DMEM (Gibco-BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) supplemented with 10% FBS. Primary human bone marrow stromal cells (hBMSC) (gift from Drs. Pamela Gehron Robey and Sergei Kuznetsov at the CSDB/NIDCR/NIH) were grown in α-minimal essential medium (Gibco-BRL) supplemented with 20% FBS. All media were supplemented with L-glutamine (2 mM), penicillin (100 IU/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). Cells were grown at 37 °C in 5% CO2/air.

4.2. Antibodies

Polyclonal goat anti-human BMP1 antibody (AF1927) was from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Polyclonal antibodies against the mouse DSP portion of DSPP (LF-153) and against human collagen α1(I) amino-propeptide (LF-39) were generated as described previously (Fisher et al., 1987; Ogbureke and Fisher, 2004). Polyclonal rabbit anti-human PCPE-1 antibody (catalog #18-272-195450) was from GenWay Biotech, Inc. (San Diego, CA). IRDye 680 donkey anti-goat and IRDye 680 goat anti-rabbit IgG second antibodies were from Li-COR Biosciences (Lincoln, NE).

4.3. Recombinant proteins

Recombinant mouse DSPP (mDSPPwt) was made from a full length mouse DSPP cDNA, a generous gift of Drs. S. Suzuki and A.B. Kulkarni of the Laboratory of Cell and Developmental Biology, NIDCR, NIH. The DSPP sequence was amplified in a thermocycler using Phusion High-Fidelity Hot Start DNA Polymerase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) and two primers encoding the mDSPP-3′ (CTAATCATCACTGGTTGAGTG) and mDSPP-5′ (CACCATGAAAATGAAGATAATTATATATATATGC) ends of the mDSPP sequence plus the bases necessary for recombination into pENTR/D-TOPO plasmid (Invitrogen). The DNA from the recombination reaction was used to transform competent STBL2 E. coli cells (Invitrogen) and selected with the appropriate antibiotic (kanamycin for pENTR and ampicillin for pAd/CMV/V5-DEST, below) under conditions developed for cloning human DSPP repetitive region sequences as previously described (McKnight et al., 2008). One sequence-verified mDSPP-pENTR clone was then recombined into the pAd/CMV/V5-DEST vector (Invitrogen). The purified DNA from one Destination clone was linearized with Pac I and transfected into HEK 293A cells for production and expansion of the replication-deficient adenovirus (Ad-mDSPP1wt) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. The adenovirus encoding the mouse protein mutant DSPPMQΔIE cDNA (Ad-mDSPP1MQΔIE) was generated using the QuikChange II Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) with the original cDNA plasmid as the template and two complementary oligonucleotides (forward = GTTCGATGACGAGTCAATTGAAGGAGATGATCCCAAG) encoding the change of the proposed BMP1-cleavage motif, MQGDD, into IEGDD. One sequence-verified clone was used as the template with the two mDSPP flanking oligonucleotides (mDSPP-3′ and mDSPP-5′) in the Phusion High Fidelity PCR reaction described above. All subsequent cloning, sequencing, recombination, and transfection steps described above for the production of the wild-type mDSPP adenovirus were then followed for the generation of the mutant-encoding adenovirus (mDSPPMQΔIE). Recombinant mDSPPwt and mDSPPMQΔIE proteins were concentrated and purified from serum-free media of the furin-deficient LoVo cells (Takahashi et al., 1993; Takahashi et al., 1995) transduced with the respective viruses by means of anion exchange chromatography as previously described for DMP1 (Fedarko et al., 2000). Human DMP1 was purified from conditioned serum-free medium of hBMSC transduced with the human DMP1-encoding adenovirus as described previously (Fedarko et al., 2000; von Marschall and Fisher, 2008).

Recombinant human BMP1-5 was generated from adenovirus-transduced hBMSC cells as described previously (von Marschall and Fisher, 2008). An adenoviral expression plasmid containing the mouse mammalian Tolloid (mTLD, BMP1-3) was generated using the clone ID6849066 (Invitrogen) containing mouse full-length mTLD cDNA. The mTLD-encoding insert was PCR-amplified using the Phusion High Fidelity DNA polymerase procedures described above and the mouse mTLD oligonucleotides (3′ = CACCATGCCCGGCGTGGCCCG and 5′ = TCACTTCCTGCTGTGGAGTGTGTCC). The amplicon was processed through the pENTR and pAD/CMV/V5-DEST vectors as described above to make and amplify the replication-deficient adenovirus. The recombinant protein was made in serum-free medium by transducing hBMSC. The expression of all three isoforms of recombinant BMP1 proteins was verified by Western blot using the goat anti-human BMP1 catalytic domain antibody. An adenoviral expression plasmid for human PCPE-1 was generated as described above using an Ultimate™ ORF human clone (IOH4174, Invitrogen) containing full-length cDNA for human PCPE-1 in pENTER™221 vector as the Gateway entry clone and recombined into the pAD/CMV/V5-DEST vector. The adenovirus was made, amplified, and used to transduce hBMSC. The serum-free conditioned medium was enriched in PCPE-1 by passing the protein through a Centriprep (Amicon/Millipore) device with a 300-kDA cutoff filter. The protein was verified by means of Western blot using the rabbit anti-human PCPE-1 antibody. Carrier-free recombinant mouse sFRP-2 (catalog # 1169-FR/CF) and recombinant human BMP1 (catalog # 1927-ZN) were purchased from R & D Systems.

4.4. In vitro cleavage assays

For type I procollagen-cleavage assays, samples of native procollagen from hBMSC-conditioned, serum-free media were incubated at 37 °C; 1) alone or in the presence of BMP1 isoforms, 2) with or without sFRP2 or PCPE-1 under either 3a) low-salt conditions (25 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 10 mM NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2, 0.01% Brij/2) or 3b) high-salt conditions (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2). Reactions were stopped after indicated times by adding 2-mercaptoethanol-containing SDS sample buffer (NuPage LDS sample buffer, Invitrogen) and heating for 10 min at 70° C. Proteins were separated on NuPAGE 3-8% Tris-Acetate gels (Invitrogen) with the company’s Tris-acetate running buffer and electro-transferred onto an Immobilon-FL membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Blots were blocked for 1 hr in Odyssey Blocking Buffer (Li-COR Biosciences), followed by incubation in a 1:1000 dilution of the polyclonal rabbit antibody against human collagen α1(I) amino-propeptide (LF-39) for 1 hr. After three washes of 5 min each in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T), blots were incubated in a 1:10,000 dilution of IRDye goat anti-rabbit IgG for 1 hr and then given a final wash (3 × 5 min in PBS-T). All steps were at room temperature. Proteins were visualized using the Li-COR Odyssey infrared imaging system (Li-COR Biosciences). Processing of type I procollagen was judged by the loss of the proα1(I) chain band and increased band intensity of the pNα1(I) chains. The SeeBlue Plus2 Pre-Stained Standards (Invitogen) were run on each gel and the apparent molecular weights of proteins were estimated based on the company’s migration charts noted for each running buffer system.

For DMP1 cleavage, 2.5 μg (dry weight) samples of purified recombinant human DMP1 in low-salt reaction buffer were incubated alone or in the presence of the noted BMP1 isoforms with or without noted amounts of sFRP2 or PCPE-1. Reactions were stopped after indicated times by adding reducing SDS sample buffer and analyzed by electrophoresing on NuPAGE 4-12% Bis-Tris gels with the company’s MOPS running buffer, followed by staining with Stains-All [3,3′-Diethyl-9-methyl-4,5,4′,5′-dibenzothiacarbo cyanine, 1-Ethyl-2-[3-(1-ethylnaphtho[1,2-d] thiazolin-2-ylidene)-2-methylpropenyl]naphtho[1,2-d]thiazolium bromide (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY)]. The DMP1 processing was noted by the decrease in the intensity of the full-length DMP1 and corresponding increase of the C- and N-terminal fragments.

For DSPP cleavage, samples of ion exchange-concentrated recombinant mouse DSPP were dialyzed into low-salt reaction buffer and then incubated alone or in the presence of BMP1 isoforms, with or without indicated amounts of sFRP2 or PCPE-1. Reactions were stopped after indicated times by adding reducing SDS sample buffer, heating for 10 min at 70° C, and analyzed by electrophoresing in SDS on NuPAGE 4-12% Bis-Tris gels in MOPS running buffer, followed by the Li-COR/Western blot procedure described above using the polyclonal rabbit LF-153 antibody (incubated overnight at 4° C) which detects both the full-length and the N-terminal fragment (DSP) of DSPP. The processing of DSPP was judged by both the decrease in the full-length DSPP and the appearance of the lower Mr DSP immunoreactive band. Except as noted, all reaction conditions were kept identical with respect to final NaCl concentrations due to the sensitivity of all three BMP1 isoforms to final salt concentrations.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Division of Intramural Research, NIDCR, of the Intramural Research Program, NIH, DHHS.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

- SIBLING

- Small Integrin-Binding LIgand, N-linked Glycoprotein

- DSP

- dentin sialoprotein

- DPP

- dentin phosphoprotein

- DSPP

- dentin sialophosphoprotein

- BMP1

- bone morphogenetic protein-1

- OPN

- osteopontin

- DMP1

- dentin matrix protein-1

- MEPE

- matrix extracellular phosphoprotein

- BSP

- bone sialoprotein

- PCPE-1

- procollagen C-endopeptidase enhancer-1

- sFRP2

- secreted frizzled-related protein-2

- PCP

- procollagen C-proteinase

- PHEX

- phosphate-regulating gene with homologies to endopeptidases on X chromosome

- mTLD

- mammalian Tolloid

- CUB domain

- a protein first found in the complement components C1r/c1s, the sea urchin protein Uegf, and BMP1

- mTLL

- mammalian Tolloid-like

- FBS

- fetal bovine serum

- hBMSC

- human bone marrow stromal cells

- HEPES

- 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid

- EGF

- epidermal growth factor.

References

- Barron MJ, McDonnell ST, Mackie I, Dixon MJ. Hereditary dentine disorders: dentinogenesis imperfecta and dentine dysplasia. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2008;3:31. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-3-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry ST, Ludbrook SB, Murrison E, Horgan CM. Analysis of the alpha4beta1 integrin-osteopontin interaction. Exp Cell Res. 2000;258:342–351. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayless KJ, Meininger GA, Scholtz JM, Davis GE. Osteopontin is a ligand for the alpha4beta1 integrin. J Cell Sci. 1998;111(Pt 9):1165–1174. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.9.1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellahcene A, Castronovo V, Ogbureke KU, Fisher LW, Fedarko NS. Small integrin-binding ligand N-linked glycoproteins (SIBLINGs): multifunctional proteins in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:212–226. doi: 10.1038/nrc2345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry R, Jowitt TA, Ferrand J, Roessle M, Grossmann JG, Canty-Laird EG, Kammerer RA, Kadler KE, Baldock C. Role of dimerization and substrate exclusion in the regulation of bone morphogenetic protein-1 and mammalian tolloid. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:8561–8566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812178106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanc G, Font B, Eichenberger D, Moreau C, Ricard-Blum S, Hulmes DJ, Moali C. Insights into how CUB domains can exert specific functions while sharing a common fold: conserved and specific features of the CUB1 domain contribute to the molecular basis of procollagen C-proteinase enhancer-1 activity. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:16924–16933. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701610200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaplet M, Waltregny D, Detry C, Fisher LW, Castronovo V, Bellahcene A. Expression of dentin sialophosphoprotein in human prostate cancer and its correlation with tumor aggressiveness. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:850–856. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vega S, Iwamoto T, Nakamura T, Hozumi K, McKnight DA, Fisher LW, Fukumoto S, Yamada Y. TM14 is a new member of the fibulin family (fibulin-7) that interacts with extracellular matrix molecules and is active for cell binding. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:30878–30888. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705847200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedarko NS, Fohr B, Robey PG, Young MF, Fisher LW. Factor H binding to bone sialoprotein and osteopontin enables tumor cell evasion of complement-mediated attack. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:16666–16672. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001123200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedarko NS, Jain A, Karadag A, Fisher LW. Three small integrin binding ligand N-linked glycoproteins (SIBLINGs) bind and activate specific matrix metalloproteinases. FASEB J. 2004;18:734–736. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0966fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher LW, Hawkins GR, Tuross N, Termine JD. Purification and partial characterization of small proteoglycans I and II, bone sialoproteins I and II, and osteonectin from the mineral compartment of developing human bone. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:9702–9708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher LW, Torchia DA, Fohr B, Young MF, Fedarko NS. Flexible structures of SIBLING proteins, bone sialoprotein, and osteopontin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;280:460–465. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.4146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrigue-Antar L, Francois V, Kadler KE. Deletion of epidermal growth factor-like domains converts mammalian tolloid into a chordinase and effective procollagen C-proteinase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:49835–49841. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408134200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godovikova V, Ritchie HH. Dynamic processing of recombinant dentin sialoprotein-phosphophoryn protein. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:31341–31348. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702605200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon VM, Klimpel KR, Arora N, Henderson MA, Leppla SH. Proteolytic activation of bacterial toxins by eukaryotic cells is performed by furin and by additional cellular proteases. Infect Immun. 1995;63:82–87. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.1.82-87.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green PM, Ludbrook SB, Miller DD, Horgan CM, Barry ST. Structural elements of the osteopontin SVVYGLR motif important for the interaction with alpha(4) integrins. FEBS Lett. 2001;503:75–79. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02690-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins DR, Keles S, Greenspan DS. The bone morphogenetic protein 1/Tolloid-like metalloproteinases. Matrix Biol. 2007;26:508–523. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janitz M, Heiser V, Bottcher U, Landt O, Lauster R. Three alternatively spliced variants of the gene coding for the human bone morphogenetic protein-1. J Mol Med. 1998;76:141–146. doi: 10.1007/s001090050202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler E, Adar R. Type I procollagen C-proteinase from mouse fibroblasts. Purification and demonstration of a 55-kDa enhancer glycoprotein. Eur J Biochem. 1989;186:115–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb15184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler E, Adar R, Goldberg B, Niece R. Partial purification and characterization of a procollagen C-proteinase from the culture medium of mouse fibroblasts. Coll Relat Res. 1986;6:249–266. doi: 10.1016/s0174-173x(86)80010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler E, Takahara K, Biniaminov L, Brusel M, Greenspan DS. Bone morphogenetic protein-1: the type I procollagen C-proteinase. Science. 1996;271:360–362. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5247.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K, Luo M, Zhang Y, Wilkes DC, Ge G, Grieskamp T, Yamada C, Liu TC, Huang G, Basson CT, et al. Secreted Frizzled-related protein 2 is a procollagen C proteinase enhancer with a role in fibrosis associated with myocardial infarction. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:46–55. doi: 10.1038/ncb1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HX, Ambrosio AL, Reversade B, De Robertis EM. Embryonic dorsal-ventral signaling: secreted frizzled-related proteins as inhibitors of tolloid proteinases. Cell. 2006;124:147–159. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leighton M, Kadler KE. Paired basic/Furin-like proprotein convertase cleavage of Pro-BMP-1 in the trans-Golgi network. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:18478–18484. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M213021200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li SW, Sieron AL, Fertala A, Hojima Y, Arnold WV, Prockop DJ. The C-proteinase that processes procollagens to fibrillar collagens is identical to the protein previously identified as bone morphogenic protein-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:5127–5130. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.5127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDougall M, Simmons D, Luan X, Nydegger J, Feng J, Gu TT. Dentin phosphoprotein and dentin sialoprotein are cleavage products expressed from a single transcript coded by a gene on human chromosome 4. Dentin phosphoprotein DNA sequence determination. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:835–842. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.2.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKnight DA, Fisher LW. Molecular evolution of dentin phosphoprotein among toothed and toothless animals. BMC Evol Biol. 2009;9:299. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-9-299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKnight DA, Hart P. Suzanne, Hart TC, Hartsfield JK, Wilson A, Wright JT, Fisher LW. A comprehensive analysis of normal variation and disease-causing mutations in the human DSPP gene. Hum Mutat. 2008;29:1392–1404. doi: 10.1002/humu.20783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moali C, Font B, Ruggiero F, Eichenberger D, Rousselle P, Francois V, Oldberg A, Bruckner-Tuderman L, Hulmes DJ. Substrate-specific modulation of a multisubstrate proteinase. C-terminal processing of fibrillar procollagens is the only BMP-1-dependent activity to be enhanced by PCPE-1. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:24188–24194. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501486200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moschcovich L, Bernocco S, Font B, Rivkin H, Eichenberger D, Chejanovsky N, Hulmes DJ, Kessler E. Folding and activity of recombinant human procollagen C-proteinase enhancer. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:2991–2996. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogbureke KU, Fisher LW. Expression of SIBLINGs and their partner MMPs in salivary glands. J Dent Res. 2004;83:664–670. doi: 10.1177/154405910408300902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogbureke KU, Fisher LW. Renal expression of SIBLING proteins and their partner matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) Kidney Int. 2005;68:155–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappano WN, Steiglitz BM, Scott IC, Keene DR, Greenspan DS. Use of Bmp1/Tll1 doubly homozygous null mice and proteomics to identify and validate in vivo substrates of bone morphogenetic protein 1/tolloid-like metalloproteinases. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:4428–4438. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.13.4428-4438.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petropoulou V, Garrigue-Antar L, Kadler KE. Identification of the minimal domain structure of bone morphogenetic protein-1 (BMP-1) for chordinase activity: chordinase activity is not enhanced by procollagen C-proteinase enhancer-1 (PCPE-1) J Biol Chem. 2005;280:22616–22623. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413468200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin C, Baba O, Butler WT. Post-translational modifications of sibling proteins and their roles in osteogenesis and dentinogenesis. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2004;15:126–136. doi: 10.1177/154411130401500302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricard-Blum S, Bernocco S, Font B, Moali C, Eichenberger D, Farjanel J, Burchardt ER, van der Rest M, Kessler E, Hulmes DJ. Interaction properties of the procollagen C-proteinase enhancer protein shed light on the mechanism of stimulation of BMP-1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:33864–33869. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205018200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie H, Wang LH. A mammalian bicistronic transcript encoding two dentin-specific proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;231:425–428. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott IC, Blitz IL, Pappano WN, Imamura Y, Clark TG, Steiglitz BM, Thomas CL, Maas SA, Takahara K, Cho KW, et al. Mammalian BMP-1/Tolloid-related metalloproteinases, including novel family member mammalian Tolloid-like 2, have differential enzymatic activities and distributions of expression relevant to patterning and skeletogenesis. Dev Biol. 1999;213:283–300. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LL, Cheung HK, Ling LE, Chen J, Sheppard D, Pytela R, Giachelli CM. Osteopontin N-terminal domain contains a cryptic adhesive sequence recognized by alpha9beta1 integrin. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:28485–28491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sreenath T, Thyagarajan T, Hall B, Longenecker G, D’Souza R, Hong S, Wright JT, MacDougall M, Sauk J, Kulkarni AB. Dentin sialophosphoprotein knockout mouse teeth display widened predentin zone and develop defective dentin mineralization similar to human dentinogenesis imperfecta type III. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:24874–24880. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303908200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiglitz BM, Ayala M, Narayanan K, George A, Greenspan DS. Bone morphogenetic protein-1/Tolloid-like proteinases process dentin matrix protein-1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:980–986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310179200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiglitz BM, Keene DR, Greenspan DS. PCOLCE2 encodes a functional procollagen C-proteinase enhancer (PCPE2) that is a collagen-binding protein differing in distribution of expression and post-translational modification from the previously described PCPE1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:49820–49830. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209891200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki S, Sreenath T, Haruyama N, Honeycutt C, Terse A, Cho A, Kohler T, Muller R, Goldberg M, Kulkarni AB. Dentin sialoprotein and dentin phosphoprotein have distinct roles in dentin mineralization. Matrix Biol. 2009;28:221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahara K, Brevard R, Hoffman GG, Suzuki N, Greenspan DS. Characterization of a novel gene product (mammalian tolloid-like) with high sequence similarity to mammalian tolloid/bone morphogenetic protein-1. Genomics. 1996;34:157–165. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahara K, Kessler E, Biniaminov L, Brusel M, Eddy RL, Jani-Sait S, Shows TB, Greenspan DS. Type I procollagen COOH-terminal proteinase enhancer protein: identification, primary structure, and chromosomal localization of the cognate human gene (PCOLCE) J Biol Chem. 1994a;269:26280–26285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahara K, Lyons GE, Greenspan DS. Bone morphogenetic protein-1 and a mammalian tolloid homologue (mTld) are encoded by alternatively spliced transcripts which are differentially expressed in some tissues. J Biol Chem. 1994b;269:32572–32578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi S, Kasai K, Hatsuzawa K, Kitamura N, Misumi Y, Ikehara Y, Murakami K, Nakayama K. A mutation of furin causes the lack of precursor-processing activity in human colon carcinoma LoVo cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;195:1019–1026. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi S, Nakagawa T, Kasai K, Banno T, Duguay SJ, Van de Ven WJ, Murakami K, Nakayama K. A second mutant allele of furin in the processing-incompetent cell line, LoVo. Evidence for involvement of the homo B domain in autocatalytic activation. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:26565–26569. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.44.26565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Marschall Z, Fisher LW. Dentin matrix protein-1 isoforms promote differential cell attachment and migration. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:32730–32740. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804283200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wermter C, Howel M, Hintze V, Bombosch B, Aufenvenne K, Yiallouros I, Stocker W. The protease domain of procollagen C-proteinase (BMP1) lacks substrate selectivity, which is conferred by non-proteolytic domains. Biol Chem. 2007;388:513–521. doi: 10.1515/BC.2007.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozney JM, Rosen V, Celeste AJ, Mitsock LM, Whitters MJ, Kriz RW, Hewick RM, Wang EA. Novel regulators of bone formation: molecular clones and activities. Science. 1988;242:1528–1534. doi: 10.1126/science.3201241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Acott TS, Wirtz MK. Identification and expression of a novel type I procollagen C-proteinase enhancer protein gene from the glaucoma candidate region on 3q21-q24. Genomics. 2000;66:264–273. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamakoshi Y, Hu JC, Iwata T, Kobayashi K, Fukae M, Simmer JP. Dentin sialophosphoprotein is processed by MMP-2 and MMP-20 in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:38235–38243. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607767200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokosaki Y, Matsuura N, Sasaki T, Murakami I, Schneider H, Higashiyama S, Saitoh Y, Yamakido M, Taooka Y, Sheppard D. The integrin alpha(9)beta(1) binds to a novel recognition sequence (SVVYGLR) in the thrombin-cleaved amino-terminal fragment of osteopontin. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:36328–36334. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Gardner J, Pullinger CR, Kane JP, Thompson JF, Francone OL. Regulation of apoAI processing by procollagen C-proteinase enhancer-2 and bone morphogenetic protein-1. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:1330–1339. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M900034-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]