Abstract

While normal aging is associated with a marked decline in cognitive abilities, such as memory and executive functions, recent evidence suggests that control processes involved in regulating responses to emotional stimuli may remain well-preserved in the elderly. However, neither the precise nature of these preserved control processes, nor their domain-specificity with respect to comparable non-emotional control processes, are currently well-established. Here, we tested the hypothesis of domain-specific preservation of emotional control in the elderly by employing two closely matched behavioral tasks that assessed the ability to shield the processing of task-relevant stimulus information from competition by task-irrelevant distracter stimuli that could be either non-emotional or emotional in nature. The efficacy of non-emotional versus emotional task-set shielding, gauged via the ‘conflict adaptation effect’, was compared between cohorts of healthy young adults, healthy elderly adults, and individuals diagnosed with probable Alzheimer’s disease (PRAD), age-matched to the elderly subjects. It was found that, compared to the young adult cohort, the healthy elderly displayed deficits in task-set shielding in the non-emotional but not in the emotional task, whereas PRAD subjects displayed impaired performance in both tasks. These results provide new evidence that healthy aging is associated with a domain-specific preservation of emotional control functions, specifically, the shielding of a current task-set from interference by emotional distracter stimuli. This selective preservation of function supports the notion of partly dissociable affective control mechanisms, and may either reflect different time-courses of degeneration in the neuroanatomical circuits mediating task-set maintenance in the face of non-emotional versus emotional distracters, or a motivational shift towards affective processing in the elderly.

Keywords: aging, cognitive control, emotional control, conflict adaptation, face-word Stroop task, probable Alzheimer’s disease

Introduction

Aging is associated with a decline in mental function across multiple domains, including memory and executive control processes (Buckner, 2004; Dennis & Cabeza, 2008). However, recent evidence also suggests that functional decline is not uniform across all types of information processing. Specifically, it appears that some facets of emotional processing remain well-preserved across the lifespan in healthy aging (Charles & Carstensen, 2007; Denburg, Buchanan, Tranel, & Adolphs, 2003; Gross, et al., 1997; Kensinger, 2008; Scheibe & Blanchard-Fields, 2009). For instance, the typical drop-off in declarative memory performance in older adults compared to younger adults does not seem to affect memories of emotionally salient material (Denburg, et al., 2003). Similarly, elderly individuals display attentional orientating responses towards emotionally salient stimuli that are comparable to those of young adults (LaBar, Mesulam, Gitelman, & Weintraub, 2000).

Studies that have tapped into processes associated with the regulation of emotional responses have even reported superior performance in the elderly. For example, the engagement in explicit emotion-regulation strategies (e.g., down-regulating emotional responses to disgust-inducing stimuli) has been found to interfere with working memory performance in younger but not in older adults (Scheibe & Blanchard-Fields, 2009), and older adults self-report fewer negative emotions and higher levels of emotional control than younger adults (Gross, et al., 1997). Finally, while there is ample evidence for an age-related decline in performance on classic ‘cognitive’ executive function tests, like the traditional color-naming Stroop task (e.g., Cohn, Dustman, & Bradford, 1984; Comalli, Wapner, & Werner, 1962; Houx, Jolles, & Vreeling, 1993; Spieler, Balota, & Faust, 1996), recent data from a study employing the ‘emotional Stroop’ task suggest that older adults do not differ from younger adults in the degree to which they are distracted by task-irrelevant emotional stimuli (Ashley & Swick, 2009; but see Wurm, Labouvie-Vief, Aycock, Rebucal, & Koch, 2004), and exhibit less carryover effects of emotional distraction from one trial to the next (Ashley & Swick, 2009).

Taken together, previous studies thus suggest preserved detection, encoding, and retrieval of emotional stimuli in older adults (e.g., Denburg, et al., 2003; Kensinger, 2008; LaBar et al., 2000), as well as a preserved (or even superior) capacity for regulating responses to emotional stimuli in the service of protecting (or ‘shielding’) task-relevant cognitive processing (Ashley & Swick, 2009; Scheibe & Blanchard-Fields, 2009). However, the precise nature of the latter regulatory processes, and their specificity with respect to comparable non-emotional control processes, remain open to question. For instance, the cited studies reporting on emotional control processes in aging did not include comparable measures of non-emotional control operations (e.g., Ashley & Swick, 2009; Scheibe & Blanchard-Fields, 2009; Wurm, et al., 2004), and could therefore not establish unambiguously the domain-specificity of the preserved functions.

In the current study, we tested the hypothesis of domain-specific preservation of emotional control processes in the elderly, by exploiting a pair of recently developed, closely matched tasks that assess a specific and central aspect of executive control, namely, the online maintenance of a current task-set (‘task-set shielding’) in the face of competition from task-irrelevant stimulus information (Egner, Etkin, Gale, & Hirsch, 2008; Etkin, Egner, Peraza, Kandel, & Hirsch, 2006). Specifically, we investigated task-set shielding, gauged via the ‘conflict adaptation effect’ (see below for details; for reviews, see Egner, 2007, 2008), in the context of conflict stemming from either non-emotional or emotional distracter stimuli, in healthy younger and older adults. In addition, we also recruited a sample of patients with probable Alzheimer’s disease (PRAD), age-matched to the healthy older adults, in order to contrast the profile of non-emotional and emotional control processes in healthy aging with that observed in the most prevalent of neurodegenerative diseases, which is thought to affect both non-emotional and emotional control functions (e.g., Doninger & Bylsma, 2007). Hence, in comparison to younger adults, we would expect the healthy elderly subjects to display a decline in non-emotional task-set shielding but not in emotional task-set shielding, whereas PRAD subjects would be expected to display impaired task-set shielding in both domains.

Before detailing the methods and results, we will here briefly introduce the theoretical background and previous findings associated with the behavioral protocols employed. ‘Cognitive control’ (which we use synonymously with ‘executive control’) refers to a collection of mechanisms that allow us to generate, maintain, and adapt sets of processing strategies (task-sets) in the pursuit of some internal goal (e.g., Botvinick, Braver, Barch, Carter, & Cohen, 2001; Miller & Cohen, 2001; Posner & Snyder, 1975). A central challenge to the control of goal-directed behavior is how to adequately maintain a current task set (a collection of top-down biasing processes), such that no processing resources are wasted, on the one hand, but task performance remains satisfactory, on the other hand. The influential ‘conflict-monitoring model’ proposes that this function is served by a regulatory loop, where a conflict-monitoring component detects processing conflicts and, if conflict occurs, recruits a strategic control component that in turn aims to resolve conflict by reinforcing top-down biasing processes associated with the current task set (Botvinick, et al., 2001). For illustration, consider the classic color-naming Stroop task (MacLeod, 1991; Stroop, 1935), where the task set consists of enhancing the processing of color relative to word information. Since top-down selection is not perfect (and processing is noisy), the relatively automatic process of word-reading nevertheless impinges on response selection. Whenever word-meaning and stimulus color are incongruent with each other (e.g., the word GREEN printed in red), this leads to conflicting representations, prolonging response times and causing occasional errors. These conflicting representations would be detected by the conflict-monitor, which in turn would reinforce the top-down biasing of color processing relative to word processing, thus ensuring that levels of top-down biasing remain commensurate with current processing difficulty (Botvinick, et al., 2001).

The most prominent measure of the workings of this proposed regulatory loop is the so-called ‘conflict adaptation effect’, which is gleaned from a first order sequential analysis of behavioral performance on conflict tasks, like the Stroop protocol (for reviews, see Egner, 2007, 2008). Here, the typical finding (first reported by Gratton, Coles, & Donchin, 1992) is that a main effect of current trial congruency (slower and less accurate responses to incongruent than to congruent stimuli) is modulated by congruency on the previous trial, with the current trial congruency effect being reduced subsequent to incongruent as compared to congruent stimuli. The conflict-monitoring model explains this effect by supposing that conflict stemming from an incongruent stimulus, via the conflict-monitor, triggers reinforced top-down biasing, enhancing the processing of task-relevant relative to task-irrelevant stimulus information. Assuming that this enhanced level of top-down control endures until the next stimulus appears, it should lead to a speed-up on incongruent trials, reflecting reduced interference by incongruent irrelevant stimulus information, and a slow-down on congruent trials, reflecting reduced facilitation by congruent irrelevant stimulus information (Botvinick, et al., 2001). While this sequential effect can in some instances be equally well explained by associative mechanisms (Hommel, Proctor, & Vu, 2004; Mayr, Awh, & Laurey, 2003), many recent studies have documented significant effects of conflict-driven task-set reinforcement when associative or ‘priming’ effects across trials were controlled for (Egner, 2007; Notebaert, Gevers, Verbruggen, & Liefooghe, 2006; Ullsperger, Bylsma, & Botvinick, 2005; Verbruggen, Notebaert, Liefooghe, & Vandierendonck, 2006).

The conflict adaptation effect has also been harnessed for exploring neural substrates of conflict-monitoring and control processes. The effect entails a particularly attractive feature for neuroimaging studies, since it allows one to directly compare activation related to incongruent trials, depending on whether they have been preceded by a congruent trial (‘CI trials’) or whether they have been preceded by an incongruent trial (‘II trials’). CI trials should be associated with low control (and thus, high conflict), since top-down biasing has not been up-regulated following the previous (congruent) trial, whereas II trials should be associated with high control (and thus, low conflict), since top-down biasing has been reinforced following the previous (incongruent) trial. By this logic, brain regions that are more active during CI than II trials are likely involved in conflict-related processing, whereas brain regions more active during II than CI trials likely represent sources or targets of top-down biasing processes of cognitive control (Botvinick, Nystrom, Fissell, Carter, & Cohen, 1999; Egner & Hirsch, 2005a). Studies pursuing this approach have shown that the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) appears to be particularly susceptible to conflict (Botvinick, et al., 1999; Egner, et al., 2008; Kerns, et al., 2004; MacDonald, Cohen, Stenger, & Carter, 2000), whereas the implementation of top-down control in Stroop-like tasks is associated with activation of lateral prefrontal cortex (lPFC) (Egner, et al., 2008; Egner & Hirsch, 2005a, 2005b; Kerns, et al., 2004; MacDonald, et al., 2000).

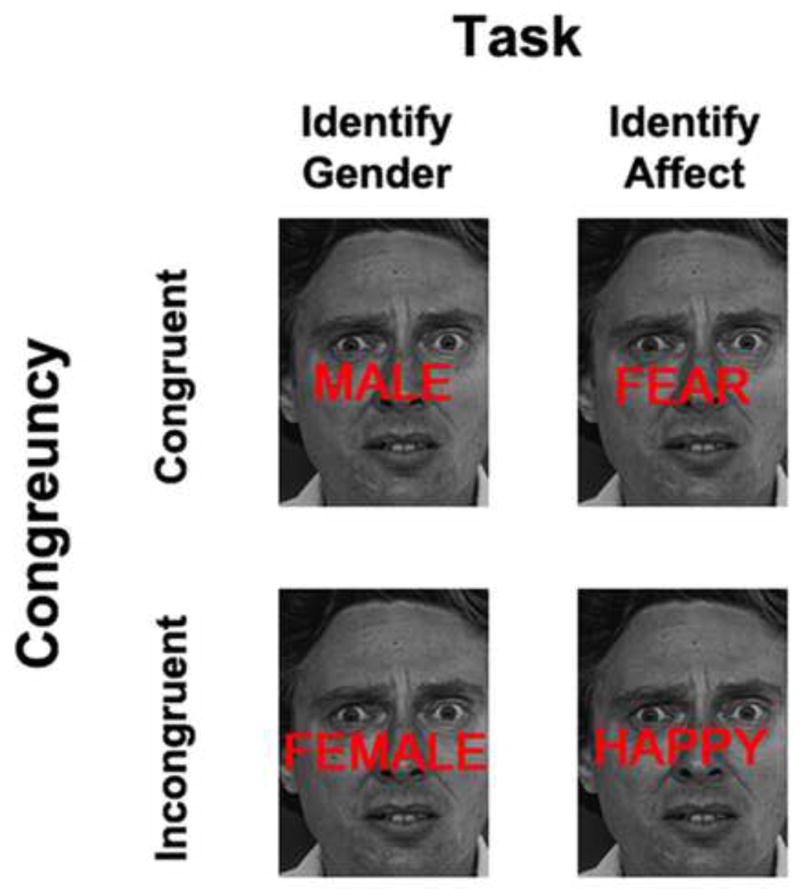

In order to probe the relation between the neural mechanisms underlying conflict adaptation in these traditional ‘cognitive’ conflict tasks with adaptation in the face of competition from emotionally salient distracter stimuli, we recently developed a pair of closely matched ‘non-emotional’ and ‘emotional’ conflict adaptation paradigms (Egner, et al., 2008; Etkin, et al., 2006). The non-emotional task consists of asking subjects to categorize face stimuli according to gender (see Figure 1), while attempting to ignore congruent or incongruent gender labels overlaid on the face stimuli. In the emotional task, subjects are required to categorize facial affect (happy versus fearful) while attempting to ignore congruent or incongruent affective labels overlaid across the face stimuli. Both tasks are associated with behavioral conflict and conflict adaptation effects, but the underlying neural substrates of conflict-monitoring and control processes differ: in the non-emotional task, conflict was associated with dACC activation and top-down control during interference reduction with lPFC activation, replicating the previous literature (Egner, et al., 2008). In the emotional task, conflict was associated both with dACC and amygdala activity, and top-down control during interference reduction was associated with rostral ACC (rACC) activity, which in turn was accompanied by reduced amygdala activation during conflict resolution (Egner, et al., 2008; Etkin, et al., 2006). From these data, we concluded that this pair of tasks taps into two distinct conflict adaptation ‘loops’ that have an overlapping conflict monitoring component (in the dACC) but recruit dissociable neural substrates for conflict resolution, depending on whether a current task set requires shielding from interference by emotional (recruiting the rACC) or non-emotional (recruiting the lPFC) stimulus processing (see also Ochsner et al., 2009).

Figure 1.

Example stimuli and experimental design. The protocol varied task (in the non-emotional task participants had to identify the gender of the face while in the emotional task participants identified the emotional expression of the face) and stimulus congruency (distracter words were placed over the face which resulted in semantically congruent or incongruent stimuli), while using the same face stimuli throughout.

These tasks may thus provide an excellent vehicle for testing the specific nature of supposedly preserved emotional control function in healthy aging. First, they measure an important and well-formalized component of executive function. Second, they facilitate a direct comparison of the integrity of emotional and non-emotional control processes. And finally, the functions gauged by these protocols are mediated by well-described neuroanatomical circuits. Here, we contrasted emotional and non-emotional conflict adaptation measures in healthy young, healthy elderly, and PRAD subjects. We expected the degree of conflict adaptation to vary between groups, as a function of task (emotional versus non-emotional). Specifically, in comparison to younger adults, we predicted that healthy elderly subjects would display a decline in non-emotional but not in emotional conflict adaptation, and that PRAD subjects would display relatively impaired conflict adaptation in both domains.

Methods

Participants

19 participants with probable Alzheimer’s disease (PRAD) and 15 age-matched healthy elderly control participants were recruited from the Clinical Core Registry of the Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer’s Disease Center at Northwestern University. Participants in the PRAD group had been diagnosed by a neurologist in a clinical setting and met current research diagnostic criteria for PRAD (McKhann, et al., 1984). Patients were screened using the Mini Mental Status Exam (MMSE) (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975) and only those with scores greater than or equal to 18/30 were included in the study. The PRAD group (mean age = 69.4) and the healthy elderly group (mean age = 69.6) did not differ in age (P > 0.1), nor did the two groups differ in years of education (P > 0.1). Table 1 summarizes demographic and neuropsychological data from the two groups. In addition to comparing performance measures between the PRAD and healthy elderly groups, we also contrasted these groups’ data with data from a sample of 22 young healthy subjects (mean age = 26.6 years). Note that data derived from the latter group have been published previously (Egner, et al., 2008). All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision, and written informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to data collection in line with institutional guidelines. Data from 6 members of the PRAD group had to be excluded from the analysis due to these participants’ encountering difficulty in understanding and completing the experimental tasks (accuracy < 70%). Therefore, the results reported below are based on 13 PRAD subjects, 15 healthy elderly subjects, and 22 healthy young subjects.

Table 1.

Mean (SD) demographic and neuropsychological data for subject groups a

| Group | Gender | Age (years) | Education (years) | MMSE | CDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young Adult | 8 M 14 F | 26.6 (5.4) | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Healthy Elderly | 7 M 8 F | 69.6 (3.19) | 16.3 (1.60) | 29.6 (.63) | 0 (0) |

| PRAD | 7 M 6 F | 69.4 (10.5) | 15.7 (2.28) | 24.4 (2.96) | .92 (.53) |

PRAD = probable Alzheimer’s disease; MMSE= mini mental status exam (maximum score of 30); CDR (Morris, 1997) = clinical dementia rating scale: (0 = no dementia, .5 = very mild dementia, 1 = mild dementia, 2 = moderate dementia, 3 = severe dementia)

Experimental Protocol and Procedure

Stimulus presentation and the recording of responses were performed using Presentation software (Neurobehavioral Systems, http://nbs.neuro-bs.com). Each trial consisted of an inter-trial interval during which there was a white central fixation cross displayed on a black background, followed by presentation of a stimulus, a single black and white photograph displayed on a black background, depicting a male or female face expressing a happy or fearful expression (Ekman & Friesen, 1976). The stimulus set consisted of 5 male and 5 female individuals, each pictured displaying a happy and a fearful expression. In the non-emotional conflict task, each face was presented with either the word ‘MALE’ or ‘FEMALE’, written in red letters, superimposed on the image (Figure 1, left panel). This created gender-congruent and gender-incongruent stimuli. In this task, the participants were required to categorize the gender of the face stimuli, while trying to ignore the task-irrelevant gender distracter words written across the faces. In the emotional conflict task, the words ‘HAPPY’ or ‘FEAR’ were superimposed on the faces (Figure 1, right panel), creating emotionally congruent and incongruent stimuli. In this task, the participants were required to categorize the emotional expression of the faces, while ignoring the task-irrelevant emotion distracter words written across the faces. In each task the participants gave their responses by pressing one of two response buttons, with their right index and middle fingers. The participant’s instructions were to respond as quickly but as accurately as possible. The right index finger was used for male/happy faces and the right middle finger for female/fearful faces.

The order of tasks was counter-balanced across subjects in each group. Each subject in each group performed 148 trials of each task. The order of trials was pseudo-random, so as to produce an equal number of congruent-congruent (CC), congruent-incongruent (CI), incongruent-congruent (IC) and incongruent-incongruent (II) first order trial sequences. In addition, gender and facial expression were counterbalanced across trial types and responses (left/right). Moreover, as described in detail elsewhere (Egner, et al., 2008; Etkin, et al., 2006), factors that could confound conflict adaptation effects, such as repetition priming (Mayr, et al., 2003) and partial repetition effects (Hommel, et al., 2004), were controlled for by ensuring that target face stimuli always changed from trial to trial, and that each trial type (CC, CI, IC, II) contained 50% response repetitions and 50% response alternations. Additionally, since there were no direct repetitions of the same face with different word distracters, we also controlled for the possibility of negative priming effects in these data.

There were some procedural differences in the way the tasks were administered to the young healthy participants on the one hand, and the healthy elderly and PRAD groups on the other hand. First, the young participants performed the tasks during fMRI data acquisition, whereas the other groups performed the tasks on a laptop computer outside the scanner. Second, the healthy young group performed each task in a single run of 148 trials (in 4 consecutive blocks of 37 trials each), while each task was broken down into two runs of 74 trials (2 consecutive blocks of 37 trials each) in the elderly and PRAD groups. This was done to provide the latter participants with some breaks, thus enhancing our chances of obtaining a satisfactory level of performance in these groups. Third, in the young sample, each stimulus was shown for 1s and the inter-trial interval (ITI) was jittered between 3s, 4s, and 5s, along a uniform distribution (mean ITI = 4s). Stimuli were shown for 1.5s to the healthy elderly and PRAD participants, and the ITI was kept constant at 3s. This was again done in order to reduce the procedural complexity of the tasks for these participant groups. Finally, prior to each task, the elderly and PRAD participants took part in two short practice runs. The first practice run consisted of twelve stimuli with no words superimposed on the faces and was implemented so that the participants could acquire the correct stimulus-to-response mappings, in the absence of competing distracter information. The participants had to categorize each face as being either male or female, or as bearing a happy or fearful expression, depending on the subsequent task. The second practice run consisted of twelve stimuli identical to those used in the main tasks, and the participants practiced to categorize the faces while ignoring the word distracters. The young healthy participants were given only this second type of practice run prior to performing the main tasks. Please note that procedural differences in how the tasks were administered between groups bear the potential for confounding main effects of group-membership on behavioral performance. However, since all of the hypotheses of interest are concerned with interaction effects between between-subject and within-subject factors, these potential confounds should not impinge on any of the main conclusions (see Results and Discussion).

Data Analyses

The two dependent variables consisted of mean reaction time (RT) and mean error rates. RT data reported excludes error and post-error trials, as well as outlier RT values that were below or above two standard deviations from the participant’s mean. RT data and error rates were initially analyzed in 4-way mixed-measures 2 × 2 × 2 × 3 ANOVAs, with the within-subject factors of task (emotional vs. non-emotional), previous trial congruency (congruent vs. incongruent) and current trial congruency (congruent vs. incongruent), and the between-subject factor of group-membership (healthy young vs. healthy elderly vs. PRAD), followed by planned comparisons within tasks (between groups) and within groups (between tasks). In addition to these analyses containing all trials, we also conducted additional sets of analyses that involved either only incongruent trials, in order to assess specifically the conflict-driven reduction of interference effects, or only congruent trials, in order to measure specifically the conflict-driven reduction of facilitation effects. We pursued this strategy because a number of behavioral studies (reviewed in MacLeod & MacDonald, 2000) and neuroimaging findings (Cohen Kadosh, Cohen Kadosh, Henik, & Linden, 2008; Szucs & Soltesz, 2007) suggest that Stroop interference and facilitation effects may derive from distinct, independent processes, rather than representing two ends of a continuum of congruency effects. Therefore, parsing the non-emotional and emotional conflict adaptation effects into interference- and facilitation-removal processes might shed additional light on the nature of performance differences between groups in our study. Thus, incongruent and congruent trials were each analyzed separately, depending on whether those trials were preceded by a congruent trial (CI or CC trials, ‘low control’) or by an incongruent trial (II or IC trial, ‘high control’), analyzing RT and accuracy data in 3-way 2 × 2 × 3 mixed-measures ANOVAs involving the within-subject factors of task (emotional vs. non-emotional) and control (low control vs. high control), and the between-subject factor of group-membership (healthy young vs. healthy elderly vs. PRAD). We will refer to the results derived from these analyses as reflecting ‘interference reduction’ and ‘facilitation reduction’ effects, respectively, as opposed to the overall ‘conflict adaptation’ effects, which are a mesh of reductions in interference and facilitation effects. Statistical significance for all tests was accepted at P < 0.05.

Results

Analyses Including Congruent and Incongruent Trials

Descriptive statistics for mean reaction time (RT) and percent accuracy in each condition for each experimental group are displayed in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. Due to the heterogeneity of our subject groups, we tested all results for unequal variances between samples (using Levene’s test of equality of variances), and whenever those are observed, we report statistical significance values from Welch’s t-test, which does not rely on the assumption of equal variances between samples.

Table 2.

Mean RT descriptive statistics across group and trial type b

| Trial | Young Adult | Healthy Elderly | PRAD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Emotional Task RT (SD) in ms | |||

| CC | 679 (118) | 749 (63) | 837 (210) |

| CI | 746 (191) | 777 (94) | 893 (258) |

| IC | 682 (191) | 751 (75) | 842 (204) |

| II | 721 (158) | 795 (98) | 942 (330) |

| Emotional Task RT (SD) in ms | |||

| CC | 780 (134) | 813 (101) | 943 (225) |

| CI | 868 (168) | 915 (104) | 1043 (278) |

| IC | 821 (175) | 839 (115) | 936 (218) |

| II | 852 (173) | 912 (110) | 1032 (253) |

Trials are split up by previous and current trial congruency. CC = previous trial congruent, current trial congruent; CI = previous trial congruent, current trial incongruent; IC = previous trial incongruent, current trial congruent; II = previous trial incongruent, current trial incongruent. RT = reaction time; SD = standard deviation; ms = milliseconds; PRAD = probable Alzheimer’s disease

Table 3.

Mean accuracy descriptive statistics across group and trial type c

| Trial | Young Adult | Healthy Elderly | PRAD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Emotional Task Accuracy (SD) | |||

| CC | 99.4% (1.19) | 98.5% (3.46) | 92.7% (7.90) |

| CI | 98.1% (3.02) | 98.9% (2.93) | 93.2% (6.57) |

| IC | 99.1% (1.58) | 98.1% (2.71) | 92.7% (10.0) |

| II | 98.2% (2.65) | 98.7% (2.32) | 90.4% (9.26) |

| Emotional Task Accuracy (SD) | |||

| CC | 98.0% (2.99) | 99.4% (1.56) | 93.2% (7.40) |

| CI | 93.6% (7.24) | 96.3% (3.74) | 82.7% (13.8) |

| IC | 96.3% (3.77) | 98.5% (1.78) | 91.9% (6.56) |

| II | 95.2% (5.16) | 98.1% (1.71) | 95.2% (5.16) |

Trials are split up by previous and current trial congruency. CC = previous trial congruent, current trial congruent; CI = previous trial congruent, current trial incongruent; IC = previous trial incongruent, current trial congruent; II = previous trial incongruent, current trial incongruent. SD = standard deviation; PRAD = probable Alzheimer’s disease

RT Data – Conflict Adaptation Effects

The RT data exhibited a main effect of task (F [1, 47] = 41.7, P < 0.001), as the emotional task was associated with higher RT (mean = 883ms, SD = 180) than the non-emotional task (mean = 770ms, SD = 174); a significant main effect of previous trial congruency (F [1, 47]= 4.2, P < 0.05), since RT was generally slightly slower on trials following incongruent trials (829ms, SD = 171) than congruent ones (mean = 824ms, SD = 164); and a main effect of current trial congruency (F [1, 47] = 61.5, P < 0.001), due to substantially slower RT on incongruent (mean = 860ms, SD = 189) as compared to congruent trials (mean = 793ms, SD = 149). The effect of current trial congruency interacted with task (F [1, 47] = 6.5, P < 0.05), as the congruency (conflict) effect was larger in the emotional task (mean = 78ms, SD = 58) than in the non-emotional task (mean = 54ms, SD = 81). Furthermore, the effect of previous trial congruency was qualified by a 3-way interaction with the task and group factors (F [2, 47] = 5.2, P < 0.01). This interaction was attributable to the fact that the PRAD group displayed a significant slowing of RT following incongruent trials in the non-emotional task (F [1, 12] = 5.1, P < 0.05) but not in the emotional task, while neither of the other groups displayed main effects of previous trial congruency in either task (all Ps > 0.1). In other words, the PRAD group displayed a selective response slowing effect following incongruent trials in the non-emotional task.

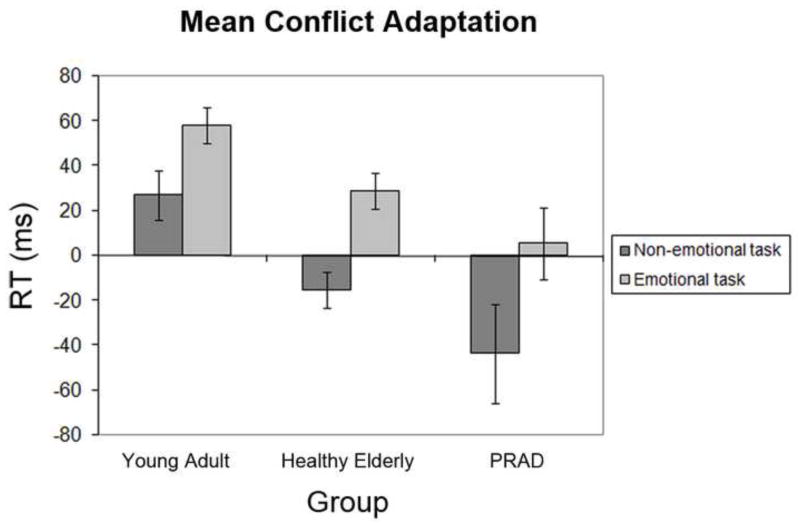

Importantly, the analysis also revealed a 3-way interaction of previous and current trial congruency with group (F [2, 47] = 5.3, P < 0.01), indicating that general conflict adaptation (irrespective of task) varied between subject cohorts. This interaction was characterized by the findings that conflict adaptation (the previous × current trial congruency interaction effect) was significant in the healthy young subjects (F [1, 21] = 22.11, P < 0.001), with an average reduction in conflict effects of 43ms following incongruent trials as compared to congruent ones, and that this degree of overall conflict adaptation in the healthy young subjects was significantly larger than that obtained in the healthy elderly group (F [1, 35] = 7.9, P < 0.01), as well as that observed in the PRAD sample (F [1, 34] = 7.7, P < 0.01). In fact, neither the healthy elderly group nor the PRAD group displayed significant overall conflict adaptation effects. However, planned within-group follow-up analyses revealed that conflict adaptation in the healthy elderly subjects interacted with task (F [1, 14] = 9.2, P < 0.01), as this group displayed significant conflict adaptation in the emotional task (F [1, 14] = 9.7, P < 0.01), but not in the non-emotional task (P > 0.1). In the PRAD group, on the other hand, no significant conflict adaptation effects were evident in either task (all Ps > 0.1). To visualize these data, Figure 2 displays mean RT conflict adaptation effects (i.e., the subtraction [CI –CC] – [II – IC]) in emotional and non-emotional tasks, for each group. In further planned follow-up analyses, we conducted pair-wise comparisons between the groups’ conflict adaptation effects (previous × current trial congruency interaction) within each task. In the emotional task, the conflict adaptation effect did not differ significantly (but displayed a marginal trend) between healthy young and healthy elderly subjects (F [1, 35] = 3.0, P = 0.09), but was significantly reduced in the PRAD group compared to the healthy young group (F [1, 34] = 5.0, P < 0.05). Emotional conflict adaptation did not differ significantly between the healthy elderly and PRAD groups, however (P > 0.1). In the non-emotional task, on the other hand, conflict adaptation was significantly reduced both in the healthy elderly (F [1, 35] = 7.1, P < 0.05) as well as in the PRAD group (F [1, 34] = 5.6, P < 0.05), in comparison with the healthy young group, with no difference between the healthy elderly and PRAD participants (P > 0.1). In summary, these RT data suggest that conflict adaptation processes in the healthy elderly were relatively impaired in the non-emotional domain, but relatively preserved in the emotional domain, whereas PRAD subjects displayed relatively impaired performance in both domains. However, it should be kept in mind that the full ANOVA did not display a significant 4-way interaction effect, such that these data are suggestive rather than conclusive (but see following sections).

Figure 2.

Mean reaction time (RT) conflict adaptation data, by group and task. Mean conflict adaptation RT reflects the previous × current trial congruency interaction [(CI-CC) - (II-IC)]. Values above zero indicate recued conflict following incongruent as compared to congruent trials (i.e., successful conflict adaptation). Error bars reflect mean standard error for within-group and within-task previous × current trial congruency ANOVAs (Masson & Loftus, 2003).

RT Data – Interference Reduction Effects

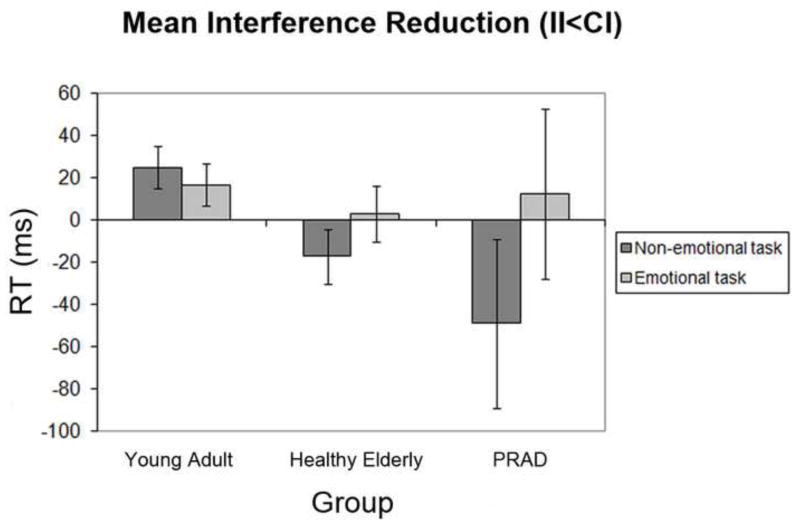

As laid out in the Methods section (see Data Analysis), we also analyzed data stemming from incongruent trials only, depending on whether those trials were preceded by a congruent trial (‘low control’) or by an incongruent trial (‘high control’) in order to isolate the interference reduction aspect of the conflict adaptation effect. Accordingly, we analyzed the incongruent trial RT data in a 3-way 2 × 2 × 3 mixed-measures ANOVA involving the within-subject factors of task (emotional vs. non-emotional) and control (low control vs. high control), and the between-subject factor of group-membership (healthy young vs. healthy elderly vs. PRAD). The RT data exhibited a main effect of task (F [1, 47] = 39.2, P < 0.001), as incongruent trials were altogether responded to more slowly in the emotional (mean = 922ms, SD = 195) than in the non-emotional task (mean = 797ms, SD = 206). Furthermore, a 2-way interaction effect was observed between the factors of control and group (F [2, 47] = 5.7, P < 0.01), as overall interference reduction (low control RT – high control RT) was stronger in the healthy young subjects than in the healthy elderly (t [35] = 3.0, P = 0.005) and the PRAD cohorts (t [33] = 2.9, P < 0.01), with no difference between the healthy elderly and PRAD samples (P > 0.1). Additionally, a 2-way interaction effect was obtained involving the factors of task and control (F [1, 47] = 5.5, P < 0.05), since interference reduction was generally more pronounced in the emotional task (mean = 11.3ms, SD = 39) than in the non-emotional task (mean = −7.0ms, SD = 66). However, most importantly, a 3-way interaction effect between task, control and group was evident in the data (F [2, 47] = 3.9, P < 0.05). This interaction was attributable to the fact that the size of the interference reduction effect differed between groups in the non-emotional task (F [2, 47] = 6.6, P < 0.005), but not in the emotional task (P > 0.1). Figure 3 depicts the degree of interference reduction (low control – high control RT) for each group in each task. Planned follow-up paired comparisons between the groups showed that, in the non-emotional task, the young healthy subjects displayed stronger interference reduction effects than the healthy elderly (t [35] = 2.9, P < 0.01) and PRAD groups (t [33] = 3.2, P < 0.005), whereas no difference was evident between the healthy elderly and PRAD cohorts (P > 0.1). In the emotional task, on the other hand, interference reduction did not differ significantly between any of the experimental groups. It should be noted, however, that the degree of interference reduction was significantly greater than zero only for the young adults (in both tasks), whereas this was not the case for the elderly or the PRAD groups, in either task. In sum, the analyses of RT data stemming from incongruent trials only has produced evidence for relatively preserved emotional control processes and a selective decline in non-emotional control processes in both healthy aging and PRAD.

Figure 3.

Mean reaction time (RT) interference-reduction, by group and task. Bars reflect the subtraction (CI-II), with values above zero representing reduced interference effects from incongruent distracter stimuli following incongruent trials as compared to congruent trials. Error bars depict standard mean error for within-group level of control × task ANOVAs (Masson & Loftus, 2003).

RT Data – Facilitation Reduction Effects

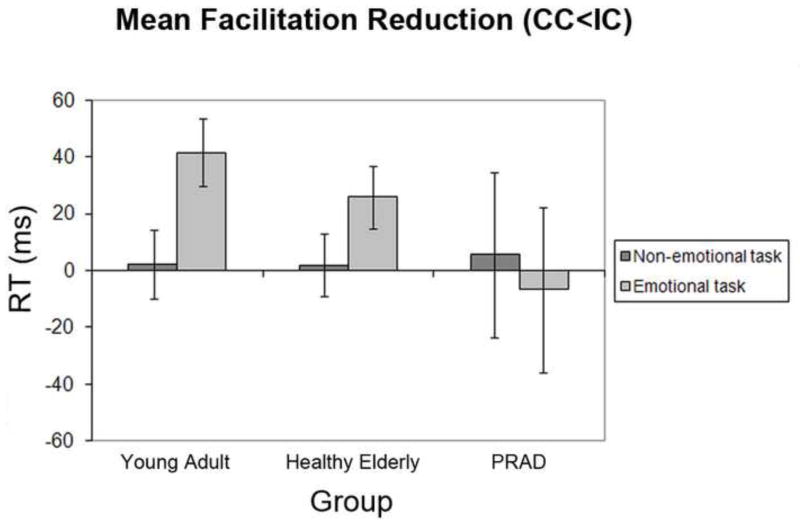

As pointed out in the Methods section (see Data Analysis), we also analyzed data stemming from congruent trials only, depending on whether those trials were preceded by a congruent trial (‘low control’) or by an incongruent trial (‘high control’), in order to isolate the facilitation reduction aspect of the conflict adaptation effect. Accordingly, we analyzed the congruent trial RT data in a 3-way 2 × 2 × 3 mixed-measures ANOVA involving the within-subject factors of task (emotional vs. non-emotional) and control (low control vs. high control), and the between-subject factor of group-membership (healthy young vs. healthy elderly vs. PRAD). The RT data displayed a main effect of task (F [1, 47] = 38.4, P < 0.001), as congruent trials were altogether responded to more slowly in the emotional (mean = 844ms, SD = 169) than in the non-emotional task (mean = 743ms, SD = 147). There was also a main effect of control on congruent trial RT (i.e., facilitation reduction) (F [1, 47] = 5.1, P < 0.05), in that congruent trials that followed an incongruent trial (IC trials) were generally responded to more slowly (mean = 800ms, SD = 153) than congruent trials that followed a congruent trial (CC trials) (mean = 787ms, SD = 147). This facilitation reduction effect interacted marginally with task (F [1, 47] = 3.6, P = 0.064), due to a stronger tendency for RT slowing due to control in the emotional task (mean = 24ms, SD = 56) than in the non-emotional task (mean = 3ms, SD = 40). Crucially, this relationship between the task and control factors was also qualified by a marginal task × control × group interaction effect (F [1, 47] = 2.9, P = 0.066). The latter is reflected in the finding that facilitation reduction was significantly more pronounced in the emotional than in the non-emotional task for both the healthy young adults (t [21] = 2.5, P < 0.05) and the healthy elderly (t [14] = 3.1, P < 0.01), but not in the PRAD group (t [12] = 0.7, P > 0.1). Furthermore, in the younger adults, the facilitation reduction effect was significant in the emotional (t [21] = 3.4, P < 0.005) but not in the non-emotional task (t [21] = 0.3, P > 0.1). Similarly, in the healthy elderly, the facilitation reduction effect was also significant in the emotional (t [14] = 3.4, P < 0.01) but not in the non-emotional task (t [14] = 0.3, P > 0.1). By contrast, in the PRAD group, there were no facilitation reduction effects in either task (both Ps > 0.1). Finally, additional tests within each task showed no differences in facilitation reduction effects between the healthy young and elderly groups (in either task), or between the healthy elderly and the PRAD groups, but a significantly stronger facilitation reduction effect in the young adults compared with the PRAD subjects in the emotional task version. In order to summarize these data, and to juxtapose the pattern of facilitation reduction effects with the pattern of interference reduction effect, Figure 4 depicts the degree of facilitation reduction (high control – low control RT) for each group in each task. To summarize, the healthy young and elderly groups displayed selective RT facilitation reduction effects in the emotional conflict task, whereas the PRAD group displayed no signs of facilitation reduction in either task.

Figure 4.

Mean reaction time (RT) facilitation-reduction, by group and task. Bars reflect the subtraction (IC-CC), with values above zero representing reduced facilitation effects from congruent distracter stimuli following incongruent trials as compared to congruent trials. Error bars depict standard mean error for within-group level of control × task ANOVAs (Masson & Loftus, 2003).

Error Rate Data – Conflict Adaptation Effects

The overall accuracy, averaged across groups and conditions, was 95.7% (SD = 5.2) (see Table 3 for detailed descriptive statistics). The mean error rates were found to be affected by the type of task (F [1, 47] = 11.5, P < 0.005), current trial congruency (F [1, 47] = 16.7, P < 0.001), and the interaction of these two factors (F [1, 47] = 14.7, P < 0.001). Akin to the RT data, more errors were committed in the emotional task (mean = 2.0, SD = 2.3) than in the non-emotional task (mean = 1.1, SD = 1.7), and the congruency (conflict) effect was stronger in the emotional (mean = 1.5, SD = 2.7) than in the non-emotional task (mean = 0.2, SD = 1.6). In addition, there was a task × previous trial congruency × current trial congruency interaction (F [1, 47] = 4.5, P < 0.05), as conflict adaptation was stronger in the emotional (mean = 1.0, SD = 2.6) than in the non-emotional task (mean = −0.2, SD = 2.4).

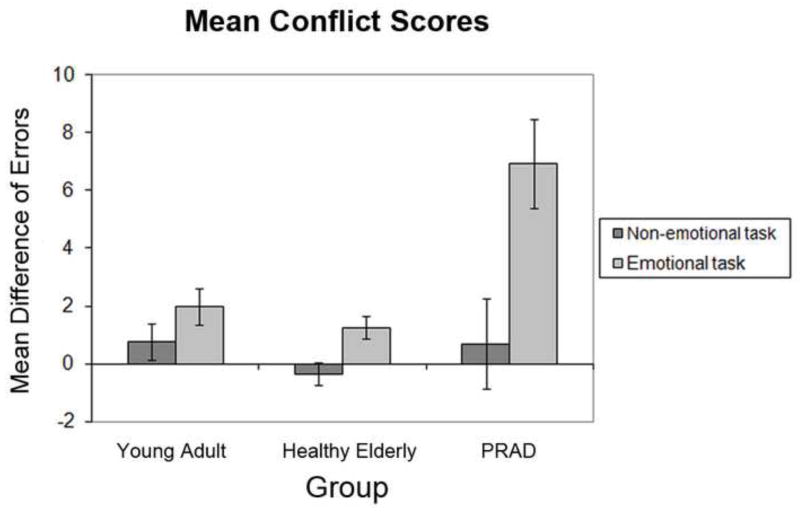

Importantly, interaction effects involving the factor of group-membership were also observed. First, the group factor interacted with current trial congruency (F [1, 47] = 14.7, P < 0.001), as the PRAD group displayed higher average conflict scores (mean = 2.0, SD = 3.35) than the healthy elderly (mean = 0.2, SD = 1.1) and young groups (mean = 0.7, SD = 1.5). However, this interaction was further qualified by a 3-way group × task × current congruency interaction effect (F [2, 47] = 4.9, P < 0.05). This interaction appeared to reflect the fact that the PRAD group displayed significantly higher conflict effects than the healthy elderly (F [1, 26] = 7.0, P < 0.05) and young groups (F [1, 33] = 5.8, P < 0.05) in the emotional task, but not in the non-emotional task (all Ps > 0.1). Another way to look at this interaction is that all three groups displayed a tendency for stronger conflict effects in the emotional than the non-emotional task, but that this difference reached significance only in the PRAD group (F [1, 12] = 6.0, P < 0.05) but not in the healthy elderly (F [1, 14] = 3.9, P = 0.07) and young groups (F [1, 21] = 3.0, P = 0.1). To visualize these data, Figure 5 depicts the mean conflict scores (incongruent –congruent trial error rate) for each group in each task. In summary, the accuracy data indicate that the PRAD patient group experienced strong interference from emotional distracters, both relative to non-emotional distracters, and to the healthy elderly and young subject cohorts.

Figure 5.

Mean error rate conflict scores, by group and task. Mean conflict scores reflect the subtraction (incongruent errors -congruent errors). Higher values signify relatively greater interference from incongruent distracter stimuli. Error bars represent mean standard error for within-group current trial congruency × task ANOVAs (Masson & Loftus, 2003).

Error Rate Data – Interference Reduction Effects

The mean error rates on incongruent trials were affected by a main effect of task (F [1, 47] = 17.6, P < 0.001), as more errors were committed on incongruent trials in the emotional (mean = 2.8, SD = 3.4) than in the non-emotional task (mean = 1.2, SD = 1.8). There was furthermore a marginal task × group interaction effect (F [2, 47] = 3.2, P = 0.051). This interaction was characterized by the fact that PRAD subjects made more errors on incongruent trials in both tasks than the healthy elderly (emotional: t [12.7] = 3.9, P < 0.01; non-emotional: t [14.1] = 3.4, P < 0.01) and young groups (emotional: t [14.6] = 3.0, P < 0.01; non-emotional: t [13.8] = 3.1, P < 0.01). In addition, the young and healthy elderly subjects did not differ in the amount of errors committed during the non-emotional task (P > 0.1), but, interestingly, the young subjects committed more errors in the emotional task than the healthy elderly (t [30.6] = 2.1, P < 0.05). We also observed a marginal task × control interaction (F [1, 47] = 3.5, P = 0.069), due to the fact that interference reduction effects tended to be larger in the emotional (mean = 0.5, SD = 2.2) than in the non-emotional task (mean = −0.3, SD = 1.6). Finally, no 3-way interaction effect was obtained. In summary, the PRAD subjects suffered greater interference from incongruent distracters than the healthy young and elderly groups across both tasks, and the healthy elderly group displayed a trend for better performance on incongruent trials in the emotional domain than the young adults.

Error Rate Data – Facilitation Reduction Effects

The mean error rates on congruent trials displayed only a marginal effect of control (i.e., facilitation reduction) (F [1, 47] = 3.6, P = 0.064), as congruent trials that followed an incongruent trial (IC trials) tended to incur more errors (mean = 1.3, SD = 1.6) than congruent trials that followed a congruent trial (CC trials) (mean = 1.0, SD = 1.5). No other effects were observed.

Discussion

The current study probed the efficacy of non-emotional and emotional conflict adaptation mechanisms in healthy young, healthy elderly, and PRAD subjects, in order to test the hypothesis that normal aging is associated with a selective preservation of emotional control functions. When considering RT for both congruent and incongruent trial types, we observed generally superior adaptation processes in the young subjects than in the elderly and PRAD groups. However, planned within-group and within-task analyses revealed that the healthy elderly group displayed an interaction between conflict adaptation and task, with significant adaptation effects observed in the emotional but not in the non-emotional task, and that this group’s performance differed from that of the healthy young in the non-emotional task but not in the emotional task (Figure 2). This pattern of differential performance on emotional versus non-emotional conflict tasks broadly replicates recent findings by Samanez-Larkin et al., (2009), who observed less overall interference from incongruent distracters for healthy older adults compared to younger adults on an emotional flanker task, but not in a non-emotional flanker task.

On the other hand, the PRAD subjects did not exhibit significant conflict adaptation effects in either protocol, and were significantly impaired in comparison to the young healthy individuals on both tasks. When considering performance on incongruent trials only, response times exhibited a 3-way interaction between control, task, and group, where the young subjects displayed significantly greater interference reduction effects than the elderly and PRAD groups in the non-emotional task, but not in the emotional task (Figure 3). While these data represent evidence for selective preservation of emotional control functions in the healthy elderly (and the PRAD subjects), it has to be noted that the overall degree of conflict-triggered interference reduction in the latter two groups was not actually statistically significant, in either task. This indicates that the significant overall conflict adaptation effect in the emotional task that we observed in the healthy elderly group was carried to a substantial degree by the removal of facilitation from congruent stimuli following incongruent trials. Indeed, the selective analysis of congruent trials documented significant facilitation reduction effects in the healthy elderly group that interacted with task, in that facilitation was significantly reduced in the emotional but not in the non-emotional task. The same pattern of facilitation reduction was observed in the young adults, but no facilitation reduction in either task was evident in the PRAD group (Figure 4).

In addition to these response time data, the mean error rates indicated that the PRAD subjects had particular difficulty with task-set shielding in the presence of emotional distracters, showing larger conflict effects in the emotional than non-emotional domain, as well as larger emotional conflict effects than either of the other groups (Figure 5). The separate analyses of accuracy data derived from incongruent and congruent trials, respectively, furthermore documented that the these higher conflict scores in the PRAD group were primarily driven by this group’s higher error rate on incongruent trials, which was evident in both the emotional and non-emotional tasks. Interestingly, we also observed overall fewer incongruent trial errors in the emotional task in the healthy elderly than in the young subjects, a finding that again supports the claim of well-preserved emotional control processes in normal aging.

Some caveats notwithstanding, the current results support the hypotheses of a domain-specific preservation of emotional control processes in healthy aging, and of domain-general impairments in control functions in early, probable Alzheimer’s disease patients, in line with predictions derived from the literature (e.g., Ashley & Swick, 2009; Denburg, et al., 2003; Doninger & Bylsma, 2007; Gross, et al., 1997; Kensinger, 2008; LaBar, et al., 2000; Scheibe & Blanchard-Fields, 2009). On the one hand, the healthy elderly group did not perform significantly worse than the healthy younger adults on any of our performance metrics for the emotional conflict task (on the contrary, they tended to commit less errors on this task than the young adults). On the other hand, the healthy elderly did exhibit poorer performance than the younger adults on several performance measures derived from the non-emotional task, most importantly, in terms of RT conflict adaptation and interference reduction effects. This pattern of preserved performance in the emotional task in the healthy elderly is particularly remarkable given that the emotional task was overall more difficult than the non-emotional task. The PRAD group, by contrast, displayed some performance impairments on either task. When compared with the younger adults, these included reduced response time conflict adaptation effects in both tasks, diminished interference reduction effects in the non-emotional task, and diminished facilitation reduction effects in the emotional task, as well as higher error rates in the emotional conflict task, both in terms of errors on incongruent trials, as well as in terms of the overall error conflict score. The PRAD group was differentiated from the healthy elderly group in particular by higher conflict error scores and a higher number of errors on incongruent trials in the emotional conflict task.

With respect to the hypothesis of selective preservation of emotional regulation in healthy aging, importantly, the use of the closely matched non-emotional and emotional conflict adaptation protocols in the current study facilitates stronger and more specific conclusions than those associated with previous studies in this field. First, the current study assessed the integrity of a very well-defined and central aspect of executive control, namely, the conflict-triggered, adaptive shielding of stimulus information that is relevant to the current task from competition by task-irrelevant stimulus information. Of course, it remains an open question for future research whether the preservation of emotional control processes in the elderly extends to other important aspects of executive control, such as the flexible shifting between task sets, but the current data, documenting preserved task set maintenance mechanisms, provide a solid starting point for such future explorations. Second, the fact that we employed tightly matched non-emotional and emotional tasks, and measured control processes as a function of task context, allows us to make firm claims in regard to the domain-specificity of the preserved functions in healthy elderly subjects. In spite of using identical face target stimuli and highly similar task requirements, we documented significant differences in the performance of healthy elderly subjects between non-emotional and emotional task versions, and performance impairments relative to younger adults that were specific to the non-emotional task. Unlike previous studies of emotional control processes in the elderly (e.g., Ashley & Swick, 2009; Scheibe & Blanchard-Fields, 2009; Wurm, et al., 2004), the current study therefore provides a clear indication that the preservation of a particular control mechanism in the elderly is indeed specific to the emotional domain.

Naturally, these findings provoke the question of why this should be the case. At the psychological level, it has been hypothesized that emotion regulation in the healthy elderly is characterized by a ‘positivity effect’, a selection bias for positively valenced information (Carstensen, Mikels, & Mather, 2005). While we did not address this hypothesis directly, it should be pointed out that this type of bias cannot easily account for the selectively preserved emotional adaptation effects observed in the healthy elderly in our study. This is because in order to successfully perform the emotional conflict task, our subjects were in fact required to attend in equal measure to negatively as well as to positively valenced stimuli (fearful versus happy faces), and a bias towards positive stimuli would confer no performance benefit in this task. On the contrary, such a bias would impair performance on incongruent trial that consist of a fearful face paired with a ‘happy’ word label. However, the healthy elderly group in our study was evidently not impaired at processing incongruent trials in the emotional task, thus arguing against a positivity-bias account for the current results. However, our data could be interpreted as broadly consistent with socioemotional selectivity theory (SST), which posits that as people age they prioritize emotional goals, undergoing a general motivational shift towards the processing of emotions (Carstensen, Isaacowitz & Charles, 1999). Such prioritizing of emotional information may in theory have aided the elderly subjects’ performance of the emotional task, relative to the non-emotional task.

At the biological level, the findings of conserved task-set shielding for the emotional task in healthy aging can potentially be accounted for by different time-courses of age-related neurodegeneration across different anatomical regions. As described in the introduction, we have previously shown that adaptation processes in these two tasks are mediated by distinct (although partially overlapping) neuroanatomical circuits (Egner, et al., 2008; Etkin, et al., 2006). Both tasks seem to share the dACC as a conflict monitor, but conflict resolution in the non-emotional task is associated with lPFC activity, whereas in the emotional task it is associated with recruitment of the rACC (and concurrent reduction in amygdalar responses). Interestingly, the literature suggests that these two circuits may be subject to different temporal profiles of degeneration: while the lPFC has been shown to display a relatively large degree of age-related degradation (Raz, et al., 2005), areas of the medial prefrontal cortex, subsuming the dACC and rACC, appear to be far less susceptible to structural changes with aging (Salat, Kaye, & Janowsky, 2001). Similarly, age-related structural changes in the amygdala have also been reported to occur at a relatively slow rate (Good, et al., 2001; Grieve, Clark, Williams, Peduto, & Gordon, 2005). In addition, neuroimaging studies have provided functional evidence for the integrity of the circuitry implicated in emotional conflict adaptation in aging, with findings of increased medial frontal activity in concert with decreased amygdala activity in the elderly in response to negative emotional stimuli (e.g., St Jacques, Dolcos, & Cabeza, 2008; Urry, et al., 2006; for a review, see St Jacques, Bessette-Symons, & Cabeza, in press). In sum, the preserved emotional conflict adaptation observed in the healthy elderly group in the current study may be reflective of the slower rate of structural degradation in limbic brain structures as compared to, in particular, the lateral prefrontal cortex.

It should be noted, however, that an alternative account (based on SST) views the age-related shift of lateral-to-medial frontal activity not as a consequence of differential degradation, but rather as reflecting a motivational shift towards more affective processing associated with age. In other words, this shift may reflect ‘cortical tuning’ rather than neural degeneration, due to preferential recruitment of areas within the PFC related to affective processing, notably the mPFC (for a recent review, see Samanez-Larkin & Carstensen, in press). Our current data cannot adjudicate between these two possibilities.

Neuroanatomical considerations can also provide a sensible account for the fact that emotional processing was not as well preserved in the PRAD sample; rather, this group displayed some signs of being particularly impaired in the emotional task (Figure 5). The progressive neurodegeneration that is characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease begins and is most prevalent in the limbic system, particularly the medial temporal lobes (Braak & Braak, 1991, 1997), and even in mild stages of the disease, neuropathological changes are already observed in the amygdala (Haroutunian, et al., 1999). Given the close association of emotional conflict adaptation processes with this limbic circuitry (Egner, et al., 2008; Etkin, et al., 2006), it is unsurprising that PRAD subjects displayed disturbed performance in this domain. It is important to note though that we did not collect structural imaging data in the current sample, such that the link between our results and differing neurodegeneration profiles in health and disease remains speculative.

Finally, two additional aspects of the current results merit commenting upon. First, as can be seen in Figures 2 and 3, the PRAD group exhibited a tendency for ‘reverse’ conflict adaptation and interference reduction effects in the non-emotional task. This pattern of response times is not predicted by the conflict-monitoring model (or by any other model we know of). One possible interpretation is to view this data pattern as a ‘conflict sensitization effect’: in certain individuals, for reasons currently not understood, conflict might trigger an enhanced alertness towards distracter stimuli, rather than an adaptation response that overrides the future processing of such stimuli. This conjecture may merit future investigation of individual differences in conflict adaptation, which has so far been lacking from the literature. Second, unlike what is typical in the conflict adaptation literature, we have pursued separate analyses of interference reduction and facilitation reduction effects. Some previous neuroimaging studies have isolated the interference reduction aspect of this effect (e.g., Egner & Hirsch, 2005a; Egner et al., 2008; Etkin et al., 2006), but the relative weights of contribution from interference versus facilitation reduction effects to conflict adaptation have not typically been addressed. Our data suggest that this might be a worthwhile endeavor, however, since it appears that interference reduction effects may be observed in the absence of facilitation reduction effects, and vice versa. This observation seems to fit well with the proposal that interference and facilitation effects may generally be attributable to distinct processes (Cohen Kadosh, et al., 2008; MacLeod & MacDonald, 2000; Szucs & Soltesz, 2007), such that individuals may display asymmetrical costs/benefits due to interference/facilitation in Stroop-like tasks. An interesting question arising from this is whether the reductions in interference and facilitation effects following conflict are nevertheless mediated by the same top-down control processes, or not. The conflict-monitoring model assumes that it is one and the same control mechanism (the reinforcement of attentional top-down biasing towards the relevant stimulus information) that leads to reduced interference and reduced facilitation effects following incongruent trials (Botvinick et al., 2001), but the possibility of distinct control mechanisms has not yet been explored in the literature and may represent another interesting target for future investigation.

To conclude, we employed two closely matched tasks to gauge the efficacy of emotional and non-emotional conflict-driven task-set shielding, in healthy young and older adults, as well as in age-matched PRAD subjects. The results provide evidence for a domain-specific preservation of emotional task-set shielding in healthy aging and domain-general impairments in PRAD. These data contribute to a growing literature describing the phenomenon of selectively preserved emotional function in the elderly. Future work, particularly deploying structural and functional neuroimaging in healthy elderly subjects, in conjunction with the type of closely matched emotional and non-emotional tasks described here, should aim at directly assessing to what extent differential neuroanatomical decline, shifting of motivational priorities, or both of these processes, may account for these findings.

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted at the Cognitive Neurology & Alzheimer’s Disease Center, Northwestern University

We would like to thank Amit Etkin and Roberto Cabeza for helpful comments on a previous version of this manuscript. This work was supported by NIA Alzheimer’s Disease Center Core Pilot Grant PHS AG13854 to Tobias Egner.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ashley V, Swick D. Consequences of emotional stimuli: age differences on pure and mixed blocks of the emotional Stroop. Behav Brain Funct. 2009;5:14. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-5-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvinick M, Nystrom LE, Fissell K, Carter CS, Cohen JD. Conflict monitoring versus selection-for-action in anterior cingulate cortex. Nature. 1999;402(6758):179–181. doi: 10.1038/46035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvinick MM, Braver TS, Barch DM, Carter CS, Cohen JD. Conflict monitoring and cognitive control. Psychol Rev. 2001;108(3):624–652. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.108.3.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82(4):239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E. Staging of Alzheimer-related cortical destruction. Int Psychogeriatr. 1997;9(Suppl 1):257–261. discussion 269–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner RL. Memory and executive function in aging and AD: multiple factors that cause decline and reserve factors that compensate. Neuron. 2004;44(1):195–208. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Isaacowitz DM, Charles ST. Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. American Psychologist. 1999;54(3):165–181. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.3.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Mikels JA, Mather M. Aging and the intersection of cognition, motivation, and emotion. In: Birren JE, Schaie KW, editors. Handbook of the Psychology of Aging. 6. Academic Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST, Carstensen LL. Emotion regulation and aging. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of Emotion Regulation. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen Kadosh R, Cohen Kadosh K, Henik A, Linden DE. Processing conflicting information: facilitation, interference, and functional connectivity. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46(12):2872–2879. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn NB, Dustman RE, Bradford DC. Age-related decrements in Stroop Color Test performance. J Clin Psychol. 1984;40(5):1244–1250. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198409)40:5<1244::aid-jclp2270400521>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comalli PE, Jr, Wapner S, Werner H. Interfernce effects of Stroop color-word test in childhood, adulthood, and aging. J Genet Psychol. 1962;100:47–53. doi: 10.1080/00221325.1962.10533572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denburg NL, Buchanan TW, Tranel D, Adolphs R. Evidence for preserved emotional memory in normal older persons. Emotion. 2003;3(3):239–253. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.3.3.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis NA, Cabeza R. Neuroimaging of healthy cognitive aging. In: Craik FIM, Salthouse TA, editors. The Handbook of Aging and Cognition. 3. Mahwah, NJ: Howard Erlbaum Associates; 2008. pp. 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- Doninger NA, Bylsma FW. Inhibitory control and affective valence processing in dementia of the Alzheimer type. J Neuropsychol. 2007;1(Pt 1):65–83. doi: 10.1348/174866407x180828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egner T. Congruency sequence effects and cognitive control. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2007;7(4):380–390. doi: 10.3758/cabn.7.4.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egner T. Multiple conflict-driven control mechanisms in the human brain. Trends Cogn Sci. 2008;12(10):374–380. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egner T, Etkin A, Gale S, Hirsch J. Dissociable neural systems resolve conflict from emotional versus nonemotional distracters. Cereb Cortex. 2008;18(6):1475–1484. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egner T, Hirsch J. Cognitive control mechanisms resolve conflict through cortical amplification of task-relevant information. Nat Neurosci. 2005a;8(12):1784–1790. doi: 10.1038/nn1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egner T, Hirsch J. The neural correlates and functional integration of cognitive control in a Stroop task. Neuroimage. 2005b;24(2):539–547. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekman P, Friesen WV. Pictures of Facial Affect. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Etkin A, Egner T, Peraza DM, Kandel ER, Hirsch J. Resolving emotional conflict: a role for the rostral anterior cingulate cortex in modulating activity in the amygdala. Neuron. 2006;51(6):871–882. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good CD, Johnsrude IS, Ashburner J, Henson RN, Friston KJ, Frackowiak RS. A voxel-based morphometric study of ageing in 465 normal adult human brains. Neuroimage. 2001;14(1 Pt 1):21–36. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratton G, Coles MG, Donchin E. Optimizing the use of information: strategic control of activation of responses. J Exp Psychol Gen. 1992;121(4):480–506. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.121.4.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieve SM, Clark CR, Williams LM, Peduto AJ, Gordon E. Preservation of limbic and paralimbic structures in aging. Hum Brain Mapp. 2005;25(4):391–401. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, Carstensen LL, Pasupathi M, Tsai J, Skorpen CG, Hsu AY. Emotion and aging: experience, expression, and control. Psychol Aging. 1997;12(4):590–599. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.12.4.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haroutunian V, Purohit DP, Perl DP, Marin D, Khan K, Lantz M, et al. Neurofibrillary tangles in nondemented elderly subjects and mild Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 1999;56(6):713–718. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.6.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hommel B, Proctor RW, Vu KP. A feature-integration account of sequential effects in the Simon task. Psychol Res. 2004;68(1):1–17. doi: 10.1007/s00426-003-0132-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houx PJ, Jolles J, Vreeling FW. Stroop interference: aging effects assessed with the Stroop Color-Word Test. Exp Aging Res. 1993;19(3):209–224. doi: 10.1080/03610739308253934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kensinger EA. Emotional Memory Across the Adult Lifespan. New York: Psychology Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kerns JG, Cohen JD, MacDonald AW, 3rd, Cho RY, Stenger VA, Carter CS. Anterior cingulate conflict monitoring and adjustments in control. Science. 2004;303(5660):1023–1026. doi: 10.1126/science.1089910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBar KS, Mesulam M, Gitelman DR, Weintraub S. Emotional curiosity: modulation of visuospatial attention by arousal is preserved in aging and early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychologia. 2000;38(13):1734–1740. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(00)00077-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald AW, 3rd, Cohen JD, Stenger VA, Carter CS. Dissociating the role of the dorsolateral prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortex in cognitive control. Science. 2000;288(5472):1835–1838. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5472.1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod CM. Half a century of research on the Stroop effect: an integrative review. Psychol Bull. 1991;109(2):163–203. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.109.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod CM, MacDonald PA. Interdimensional interference in the Stroop effect: uncovering the cognitive and neural anatomy of attention. Trends Cogn Sci. 2000;4(10):383–391. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01530-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masson ME, Loftus GR. Using confidence intervals for graphically based data interpretation. Can J Exp Psychol. 2003;57(3):203–220. doi: 10.1037/h0087426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayr U, Awh E, Laurey P. Conflict adaptation effects in the absence of executive control. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6(5):450–452. doi: 10.1038/nn1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller EK, Cohen JD. An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:167–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC. Clinical dementia rating: a reliable and valid diagnostic and staging measure for dementia of the Alzheimer type. Int Psychogeriatr. 1997;9(Suppl 1):173–176. doi: 10.1017/s1041610297004870. discussion 177–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notebaert W, Gevers W, Verbruggen F, Liefooghe B. Top-down and bottom-up sequential modulations of congruency effects. Psychon Bull Rev. 2006;13(1):112–117. doi: 10.3758/bf03193821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner KN, Hughes B, Robertson ER, Cooper JC, Gabrieli JDE. Neural systems supporting the control of affective and cognitive conflicts. J Cogn Neurosci. 2009;21(9):1841–1854. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner MI, Snyder CR. Attention and cognitive control. In: Solso RL, editor. Information Processing and Cognition. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1975. pp. 55–85. [Google Scholar]

- Raz N, Lindenberger U, Rodrigue KM, Kennedy KM, Head D, Williamson A, et al. Regional brain changes in aging healthy adults: general trends, individual differences and modifiers. Cereb Cortex. 2005;15(11):1676–1689. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salat DH, Kaye JA, Janowsky JS. Selective preservation and degeneration within the prefrontal cortex in aging and Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2001;58(9):1403–1408. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.9.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samanez-Larkin GR, Robertson ER, Mikels JA, Carstensen LL, Gotlib IH. Selective attention to emotion in the aging brain. Psychol Aging. 2009;24(3):519–529. doi: 10.1037/a0016952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samanez-Larkin GR, Carstensen LL. Socioemotional functioning and the aging brain. In: Decety J, Cacioppo JT, editors. The Handbook of Social Neuroscience. New York: Oxford University Press; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Scheibe S, Blanchard-Fields F. Effects of regulating emotions on cognitive performance: what is costly for young adults is not so costly for older adults. Psychol Aging. 2009;24(1):217–223. doi: 10.1037/a0013807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spieler DH, Balota DA, Faust ME. Stroop performance in healthy younger and older adults and in individuals with dementia of the Alzheimer’s type. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform. 1996;22(2):461–479. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.22.2.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St Jacques P, Dolcos F, Cabeza R. Effects of aging on functional connectivity of the amygdala during negative evaluation: A network analysis of fMRI data. Neurobiol Aging. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St Jacques PL, Bessette-Symons B, Cabeza R. Functional neuroiaging studies of aging and emotion: Fronto-amygdalar differences during emotional perception and episodic memory. Journal of International Neuropsychological Society. doi: 10.1017/S1355617709990439. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroop JR. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. J Exp Psychol. 1935;18:643–662. [Google Scholar]

- Szucs D, Soltesz F. Event-related potentials dissociate facilitation and interference effects in the numerical Stroop paradigm. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45(14):3190–3202. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullsperger M, Bylsma LM, Botvinick MM. The conflict adaptation effect: it’s not just priming. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2005;5(4):467–472. doi: 10.3758/cabn.5.4.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urry HL, van Reekum CM, Johnstone T, Kalin NH, Thurow ME, Schaefer HS, et al. Amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex are inversely coupled during regulation of negative affect and predict the diurnal pattern of cortisol secretion among older adults. J Neurosci. 2006;26(16):4415–4425. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3215-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbruggen F, Notebaert W, Liefooghe B, Vandierendonck A. Stimulus-and response-conflict-induced cognitive control in the flanker task. Psychon Bull Rev. 2006;13(2):328–333. doi: 10.3758/bf03193852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurm LH, Labouvie-Vief G, Aycock J, Rebucal KA, Koch HE. Performance in auditory and visual emotional stroop tasks: a comparison of older and younger adults. Psychol Aging. 2004;19(3):523–535. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.3.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]