Abstract

Objectives

To describe recruitment of Latinas in a randomized clinical trial conducted within 2 health-care organizations.

Methods

The study relied on project-initiated telephone calls as part of a multi-faceted recruitment approach. Chi-square and t tests were conducted to compare participants and nonparticipants on a number of variables.

Results

From 4,045 telephone contacts, 280 Latinas agreed to participate. Most were ineligible due to non-Latino ethnicity (89%). Of eligible candidates, 61% took part. Few significant differences were found on participant vs. nonparticipant characteristics.

Conclusion

Using appropriate recruitment procedures, a representative sample of Latinas can be obtained.

Keywords: heart disease, diabetes, Latinas, multiple health behaviors, participation

Introduction

In 1993, the National Institutes of Health began requiring researchers to include women and minorities in randomized clinical trials and epidemiological studies.1 Prior to 1993, studies tended to include insufficient numbers of women, especially from diverse cultures, which hampered generalizability. Given the mandate, researchers were compelled to find ways to adapt recruitment methods to adequately sample people from diverse populations. A number of publications address this issue.2-7 However, in reviewing these studies, Froelicher and Lorig8 noted that many researchers used recruitment techniques such as local media advertising or word of mouth which can increase the likelihood of self-selection, and can thus bias samples and jeopardize generalizability.9

The purpose of this paper is to address minority recruitment issues by documenting the recruitment of Latinas with type 2 diabetes for a comprehensive lifestyle program called ¡Viva Bien!. Included are details about recruitment procedures, participation rates, and comparisons between participant and nonparticipant characteristics to assess representativeness.

Background

Hispanic Americans, the fastest-growing ethnic population in the U.S.—and particularly postmenopausal Hispanic women (Latinas)—have a greater prevalence of type 2 diabetes and higher incidence of diabetes complications than Anglos10. Diabetes is an independent risk factor for coronary heart disease (CHD) in both Latino and Anglo women, but appears to be a greater risk factor for U.S.-born Latinas11,12. Among Latinas, diabetes ranks as the third leading cause of death. Interventions aimed at promoting healthful lifestyle behaviors offer great potential for diabetes treatment13.

The goal of ¡Viva Bien! was to evaluate an established, efficacious lifestyle change program with an important under-served population at high risk for CHD: Latinas with type 2 diabetes. The research team had twice shown the effectiveness of this theory-based program in improving behavioral, psychosocial, quality of life, and biological outcomes in postmenopausal, mostly Anglo women with type 2 diabetes in Oregon (the Women’s Lifestyle Heart Trial14,15 and the Mediterranean Lifestyle Program [MLP]16,17). The ¡Viva Bien! project was designed to evaluate whether the same program would succeed with Latinas in Colorado (Kaiser Permanente [KP], Denver, and Salud Family Health Center, Commerce City). Participants in the 2-year ¡Viva Bien! program were instructed to: (a) follow the Mediterranean diet adapted for the Latino culture18, (b) practice stress-management techniques daily, (c) engage in 30 minutes of physical activity 5 days per week, (d) stop smoking (for smokers), and (e) participate in problem-solving-based social support sessions. ¡Viva Bien! was a less-intense version of the Ornish19 program to fit women who were at risk for but did not have CHD. The intervention began with a 2½-day retreat to jumpstart the program and create camaraderie among participants. After that, women attended 4-hour weekly meetings for 6 months to practice their behavior changes and bolster social support, then met on a fading schedule for the final 18 months.

METHODS

The study was conducted in 4 waves with roughly one-fourth of the sample per wave. Participants were recruited in the 3 months prior to their retreat.

Participants

The study sought to recruit 300 Latinas with type 2 diabetes who received their medical care from 19 clinics associated with KP in the Denver, Colorado, metropolitan area. In addition, non-KP members were recruited from the Salud Family Health Center in Commerce City near Denver. In order to sample from different socioeconomic levels, each of the 4 waves of participants was recruited from a different geographic area (roughly described as west, central, northwest, and northeast Denver). Original inclusion criteria were: female sex, diagnosis of type 2 diabetes for at least 6 months identified by electronic medical record codes and using the Welborn criteria20, living independently, having a telephone, ability to read in either English or Spanish, not developmentally disabled, and living close to the intervention site. Original exclusion criteria included being older than 75 or younger than 40 years of age, being on an insulin pump, or having end-stage renal disease. After sluggish initial recruitment for the study, it was necessary to lower the minimum age criterion from 40 to 30 years of age and to remove the postmenopausal requirement in order to make the sample more inclusive, and thus more representative, and to increase the likelihood that the recruitment goal of N=300 would be met.

Recruitment Procedures

A multi-faceted recruitment strategy was used. Bilingual project staff initiated contact by telephoning prospective participants, describing the program in either Spanish or English, determining eligibility, and inviting qualified candidates to participate. This approach contrasts with a strategy that requires potential participants to initiate contact, perhaps as a result of Internet, radio, or television advertisements or public service announcements. The multi-faceted method was selected to yield a less-biased sample than would be obtained by methods requiring potential participants to self-select by initiating contact. To maximize success of the telephone calls, the recruitment method included an initial phase that increased awareness and created a positive impression of the program. Letters in English and Spanish signed by the project’s Latino physician were mailed to potential participants, along with self-addressed stamped postcards that recipients could return to decline further contact or request further information. The postcard included a checklist of reasons for declining participation. Women who did not return postcards or requested further information were telephoned by project recruiters.

In an effort to reduce participation barriers, the project offered flexible assessment times, bilingual staff and materials, convenient assessment locations, follow-up reminders, and free transportation. Such practices have been shown to enhance recruitment in diverse populations4. Recruitment procedures were approved by the KP Colorado and Oregon Research Institute Institutional Review Boards.

The recruitment approach was tested in a pilot study21. In the pilot, Generally Useful Ethnic Search System (GUESS) software (developed by the University of New Mexico28), was used with KP’s diabetes registry to identify women with type 2 diabetes having Spanish surnames. The GUESS system, however, failed to identify many women who had married and adopted non-Spanish surnames. Therefore, in the main study the GUESS software was not used. Instead, all women fitting age and diabetes criteria were contacted, and self-ethnicity was determined during telephone screening. This strategic change meant that recruiters would be required to telephone a large number of women who would prove ineligible due to non-Latino ethnicity, but the situation could not be avoided as otherwise many eligible Latinas would never have been contacted. Patients were identified through KP’s electronic prevention and disease population management system, HealthTrac, and its electronic medical records system, Health Connect.

KP usual diabetes care consisted of diabetes management directed by a primary care physician with the support of a diabetes nurse case manager. Diabetes case managers assisted those with very elevated hemoglobin A1c levels and helped manage medications along with the primary treating physician. Regular basic diabetes classes were available (limited availability in Spanish) to diabetes patients who had not previously received such education.

Despite good recruitment for the ¡Viva Bien! pilot, achieving the enrollment target of 300 for the main study proved challenging. As a result of slow initial recruitment efforts, changes were made in recruitment strategies to bolster participation. Recruiters more strongly stressed the personal nature of ¡Viva Bien!, the focus on family/friends and health, the lack of a program fee, and free transportation. In addition, in-house ¡Viva Bien! staff took over the recruitment calling, and use of an off-site marketing organization for recruitment was discontinued. With in-house recruiters, KP caller ID was displayed on the telephones of potential participants, and pickups increased.

Another strategy to increase the sampling pool, and to broaden the reach of the intervention, was to expand recruitment in the fourth wave to include patients from Plan de Salud del Valle, Inc. Salud is a community health center providing comprehensive primary health services to all residents of a catchment area covering parts of 6 counties without regard to age, sex, disease, or ability to pay. Most of Salud’s clients lack private insurance and have little or no access to other health-care providers. Salud provided a list of female diabetes patients aged 30 and older. The same recruitment procedures were used for Salud as for KP.

Salud usual care consisted of diabetes management directed by the primary care physician, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant. Monthly diabetes classes were conducted in Spanish and English. Medications were available through a non-profit pharmacy offering reduced rates. Specialty services were available through partnerships with community providers and offered at discounted rates.

In addition to adding the Salud clinic, the usual-care control condition was enhanced to boost recruitment: Participants were given health information packets and were permitted to participate in one health-oriented course (eg, Tai Chi, yoga) free of charge (although none did so).

Within 2 weeks of mailing letters describing ¡Viva Bien!, project recruiters conducted scripted telephone calls with potential participants who had not returned the decliner card. Recruiters described the study, answered questions, screened for eligibility, advised participants of random assignment, invited participation, and scheduled baseline assessment visits. Those who declined participation were asked for a reason, and responses were categorized and coded. Of those agreeing to participate, women failing to complete baseline assessments and undergo randomization, or continue contact with the study, were defined as dropouts.

Recruitment procedures in ¡Viva Bien! were identical with those used in the MLP, the program upon which ¡Viva Bien! was based, with one exception: In the MLP, primary care physicians were first contacted and then patients were sent letters from their doctors before being telephoned to invite participation.

Measures

A large battery of behavioral, psychosocial, and biologic variables was collected in the ¡Viva Bien! study. A subset of measures was selected for the present analyses based on their hypothesized importance in affecting an individual’s decision to enroll in a randomized clinical trial. From our previous research22, socioeconomic and demographic characteristics (eg, income, education, age, severity of diabetes) were hypothesized to influence participation. Measures of body weight and smoking status were included, given the behavioral outcomes of the study’s intervention (eg, diet, smoking cessation). This subset of measures is described below.

Telephone screening form

In the initial telephone screening, the following information was obtained: language preference, ethnicity, smoking status, and presence or absence of end-stage renal or kidney disease. To verify type 2 diabetes status, the following information was solicited: age, age at diabetes diagnosis, type of diabetes medications, years taking diabetes medications, and self-reported height and weight.

Baseline assessment

The following information was collected from participants at the baseline assessment: body weight and height, waist/hip ratio, income, living arrangement, education, and acculturation (using the Brief Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans-II [ARSMA-II scale23]). Data from the acculturation measure were converted to a 5-point scale (Level 1=mostly Latino-oriented to Level 5=mostly Anglo-oriented). Participants at baseline were assessed at one of 4 centrally located KP clinics or at the Salud clinic. Two baseline visits were scheduled at least one week apart.

Analyses

Data were entered electronically and verified. Descriptive statistics were computed for all variables to clean the data (eg, remove out-of-range values, identify outliers), understand the nature of the data, and ensure the appropriateness of distributions for the planned statistical tests. Descriptive statistics for the variables of interest were examined overall and separately by study condition to confirm that the intended initial comparability of the groups was achieved. These variables included age, age diagnosed with diabetes, body mass index, smoking habits, language preference, years taking diabetes medications, and type of diabetes medications. To assess representativeness of the study participants, chi-square tests for nominal variables and t tests for continuous variables were performed to compare the characteristics of women who refused to participate with women who were randomized to the study, with the significance threshold set at P<.05. Chi-square and t tests, as appropriate, also were conducted to compare characteristics of KP and Salud participants. Data imputation was not performed, as missing data were negligible. All data analyses were performed using SPSS version 14.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago IL).

Power analyses conducted prior to the study indicated that, assuming a conservatively moderate effect size of f=.20 based on our studies and other published research with women having type 2 diabetes, a final sample of N=220 (n=110 in treatment and n=110 in control conditions) would be necessary to provide adequate power (at .85, alpha = .05, 2-tailed) to detect anticipated effects. Thus, the sample achieved, consisting of N=280 participants, is more than adequately powered for the analyses.

RESULTS

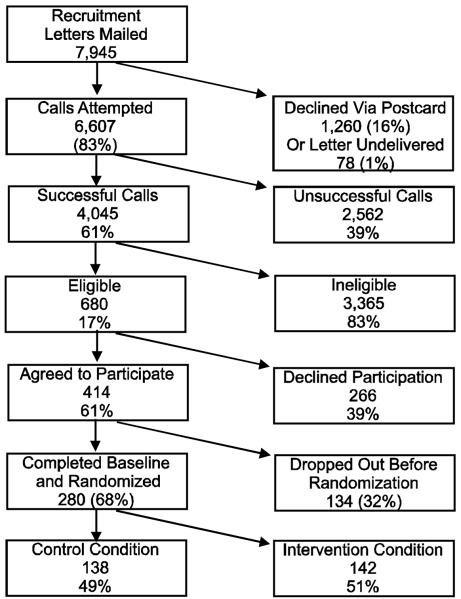

As shown in the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram (Figure 1), 7,945 women from KP or Salud were mailed recruitment letters, of whom 16% returned decliner postcards. Of those remaining, 4,045 women (61%) were contacted by telephone. The most common reasons for unsuccessful phone contact were unanswered or unreturned calls (65%) or phones disconnected (9%). Of women successfully reached by phone, 680 (17%) met eligibility criteria. Most were ineligible due to not being Latina (89%), not having type 2 diabetes (5%), not being a KP or Salud patient (2%), or not being in the specified age range (1%).

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram of ¡Viva Bien! Recruitment

Among eligible KP and Salud patients, 61% (KP = 60%; Salud =67%) agreed to participate in ¡Viva Bien!. Of those giving a reason for declining participation, most said the program was too time-consuming (18.8%) or they were too busy (16.9%). About 6% said they were too ill. Other reasons for declining participation included inability to attend the retreat or weekly meetings (15.3%), having a husband who disapproved (0.8%), and objections to being labeled Hispanic (0.4%). Twelve of the 16 eligible Salud patients who declined participation gave a reason; most often they were unable to attend the weekly meetings (18.8%) or lacked interest in research (18.8%).

About 32% of ¡Viva Bien! participants dropped out prior to baseline assessment, with no significant differences on demographic or medical variables between those who continued participation and those who did not. Of the 414 women agreeing to participate in ¡Viva Bien!, 68% completed the baseline assessment and were randomized to one of the 2 treatment conditions.

Participation rates in ¡Viva Bien! did not differ significantly between KP (60%) and Salud (67%) patients in the fourth wave of the study: χ2(1) = .13, P = .72, nor did dropout rates prior to the retreat (Salud = 67% vs. KP = 60%): χ2(1) = 1.28, P = .26.

Among those eligible, no statistically significant differences were found between ¡Viva Bien! participants and nonparticipants in age, age diagnosed with diabetes, number of years taking diabetes medications, type of diabetes medication, or language preference (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparisons Between ¡Viva Bien! Participants and Nonparticipants (Mean (SD) or %)

| Characteristic | Participant | Nonparticipant | Sig.a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Telephone Screening | |||

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 33.9 (7.48) | 31.9 (7.29) | .002 |

| % Smokers | 9.8% | 16.4% | .03 |

| Age | 57.2 (10.0) | 58.5 (10.7) | .14 |

| Age Diagnosed | 47.8 (11.8) | 50.0 (12.3) | .88 |

| % Prefer Spanish | 14.8% | 12.8% | .58 |

| Years Taking Meds. | 6.2 (6.0) | 6.7 (6.4) | .55 |

| Type of Diabetes Meds. | .27 | ||

| None | 10.4% | 8.3% | |

| Oral Only | 58.2% | 57.9% | |

| Insulin Only | 10.4% | 15.5% | |

| Oral + Insulin | 21.1% | 18.3% | |

| Screening to Baseline Attrition | |||

| Age | 57.0 (10.1) | 58.7 (8.7) | .40 |

| Age Diagnosed | 47.6 (11.9) | 49.5 (9.7) | .43 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 33.94 (7.54) | 32.94 (6.82) | .50 |

| % Smokers | 9.2% | 16.7% | .24 |

| % Prefer Spanish | 15.2% | 9.5% | .48 |

| Years Taking Meds. | 6.2 (6.0) | 7.5 (5.8) | .53 |

| Type of Meds. | .07 | ||

| None | 11.4% | 0% | |

| Oral Only | 58.5% | 55.6% | |

| Insulin Only | 9.2% | 22.2% | |

| Oral + Insulin | 21.0% | 22.2% | |

t test or chi-square test, as appropriate

Smokers were more likely to decline participation than nonsmokers (16.4% smoking rate among nonparticipants vs. 9.8% for participants, P < .03), and nonparticipants tended to have a lower BMI than participants (mean BMI=31.9 kg/m2 for nonparticipants vs. 33.9 kg/m2 for participants, P < .002). On the ARSMA-II, the recruited sample for ¡Viva Bien! was classified as 40.8% mostly Anglo-oriented, 24.3% somewhat Anglo-oriented, 17.6% mixed Latino-and-Anglo-oriented, 4.8% somewhat Latino-oriented, and 12.5% mostly Latino-oriented. Most participants were born in the U.S. (79.6%) or Mexico (15.8%), with one to 2 women each reporting their birth country as El Salvador, France, Morocco, Brazil, Peru, Panama, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guatemala, or Honduras. The participants’ parents also were born primarily in the U.S. (mother=72.1%; father=69.8%) and Mexico (mother=21.6%; father=23.7%), with small percentages in many other European, Asian, and Latin American countries.

No statistically significant differences were found between KP and Salud patients in the fourth wave of ¡Viva Bien! in BMI, smoking prevalence, years taking diabetes medications, or types of diabetes medication. However, Salud patients, relative to KP patients, tended to be younger (mean age=50.5 years vs. 58.2 years, P < .001), to have been diagnosed with diabetes at a younger age (mean age at diagnosis=43.7 vs. 48.1, P < .05), and to prefer Spanish (44.8% vs. 11.6%, P < .001).

The total cost of recruiting study participants for ¡Viva Bien! was $71,673.50, or $262.54 per randomized participant. ¡Viva Bien! recruitment costs included identifying potential subjects, assembling and mailing letters and postcards, telephoning potential participants (including unsuccessful calls), completing the telephone screening form, and scheduling baseline visits.

DISCUSSION

To maximize the public health impact of diabetes lifestyle interventions, programs must attract their intended audience, including ethnically diverse and high-risk participants. One way of assessing program reach is to examine differences between eligible enrollees and non-enrollees. Our analyses revealed few differences between participants and nonparticipants in ¡Viva Bien!, suggesting that a representative sample of Latinas was obtained. Other studies have reported few significant differences between Latino participants and eligible nonparticipants2,3, noting only differences in education and age2, and gender and language preference.

The reach of ¡Viva Bien! was likely enhanced by attractive program characteristics such as the lack of a fee, bilingual staff, culturally appropriate materials in Spanish and English, and affiliation with one’s regular health-care system. The program attracted (nonsignificantly) more eligible Salud than KP patients by percentage, suggesting that it reached lower-income, ethnically diverse, and high-risk populations as well as those with more economic resources. Latina participants represented a range of acculturation, and were drawn from both low- and higher-income levels. Language preference did not play a significant role in ¡Viva Bien! participation, nor in the Escobar-Chaves et al2 trial, but significantly more participants than nonparticipants preferred to speak Spanish in Eakin et al.3

The ¡Viva Bien! telephone recruitment strategy, as part of a multi-faceted approach, was highly effective. Most women (61%) reached by telephone who were eligible for the study agreed to participate, and a representative sample was achieved (ie, there were few significant differences between nonparticipants and participants). The greatest barrier to participation was not refusal to take part, but ineligibility due to non-Latino ethnicity (89%) or not having type 2 diabetes (5%), and this was expected given that the patient lists used for recruitment were known to consist mostly of non-Latinas. Our findings suggest that future studies with Latinas might benefit from a similar multi-faceted recruitment strategy, in which the project initiates contact with potential participants, rather than a self-selection strategy, which requires potential participants to initiate contact. While more costly, this approach produces a less-biased sample.

Numerous similarities were found in the results between ¡Viva Bien! and the MLP, the study with mostly Anglo women upon which ¡Viva Bien! was based. Women in the 2 studies gave similar reasons for nonparticipation, primarily being too busy or too time-consuming, with a few saying they were too ill to participate. Reasons for declining participation unique to ¡Viva Bien! included inability to attend the retreat or weekly meetings, and objections to being labeled Hispanic, although the latter objections were raised by very few of the women. These obstacles to participation were similar to those found in the other studies24. The most common reason given by Latinos for nonparticipation in Robertson25 was lack of information; a review of studies by Ford et al24 of under-represented populations noted that mistrust of research and the medical system was paramount. Trust may have been bolstered in ¡Viva Bien! by endorsements from the women’s health-care providers.

Samples recruited in the ¡Viva Bien! and MLP studies were similar in employment status, smoking status, percent prescribed oral medications, percent prescribed insulin, and waist/hip ratio. Compared to the mostly Anglo MLP women, the ¡Viva Bien! Latinas on average weighed less, had lower BMIs, had higher hemoglobin A1c values, were younger, were diagnosed with diabetes at a younger age, had been taking diabetes medications longer, and had higher incomes (adjusted for inflation) and less formal education. Compared to the MLP participants, more ¡Viva Bien! participants took no diabetes medications or took a combination of insulin and oral medications. ¡Viva Bien! participants were more likely than MLP women to live with their spouse and children, or with children and others; a greater percentage of MLP participants lived alone. Since there were very few differences between participants and nonparticipants in either study, the above differences between MLP and ¡Viva Bien! samples are most likely due to underlying differences in the Latina/Denver and largely Anglo Oregon target populations.

¡Viva Bien! had a higher rate of women who agreed to participate completing baseline assessment (68%) than the MLP (51%), and much higher than other, less-intensive intervention programs with similar ethnically diverse samples. Participation rates were 14% in the Preferences of Women Evaluating Risks of Tamoxifen (POWER) study4 and 27% to 53% in a cancer prevention study of mostly Latina women26. As in the MLP, ¡Viva Bien! participants and nonparticipants did not differ significantly on many variables.

The cost of recruitment for ¡Viva Bien! was $262.54 per randomized participant, compared to the $714 for the MLP27 (with a 14% inflation adjustment). ¡Viva Bien! recruitment cost less per unit than the MLP because of the efficient use of electronic medical record and administrative databases, and because the MLP required an additional step of recruiting individual physician practices prior to initiating patient recruitment. Reflecting the well-recognized challenges of recruiting Latinas for clinical trials6, ¡Viva Bien! recruitment was moderately expensive. Most of the expense was due to telephone screening, which should be reported in more studies. KP Colorado is now undertaking a major effort to obtain information on race and ethnicity; had this information been available, it would have greatly reduced recruitment costs.

Given the importance of including ethnically diverse populations in research, recruitment lessons learned from the ¡Viva Bien! study may be informative for research and practice. Similar to the experiences described in Rodríguez et al5, ¡Viva Bien! had varying levels of difficulty in recruiting Latino women across 4 waves. Especially challenging was wave 2, which required a 63% larger sampling pool than the other waves. After sluggish initial recruitment, strategic changes made in procedures resulted in more favorable participation rates. Especially important was the switch to in-house recruiters, who were more invested, more familiar with the study, more likely to be bilingual, and able to ask project managers to immediately address concerns. ¡Viva Bien! recruiters tried to complete calls without deferring to another time, and to make multiple call attempts instead of leaving messages. Using these measures, ¡Viva Bien! nearly achieved the recruitment goal of 300 participants.

This study has both methodological strengths and limitations. Strengths include a defined population to assess program reach, assessment of sample representativeness on demographic and medical characteristics, identification of reasons for nonparticipation, analysis of patient factors related to participation, and multi-faceted recruitment procedures to limit bias in the sample. An intentional but somewhat specialized feature of the study is that much of the sample (KP) represented a largely employed population in one health maintenance organization. As with all studies conducted within one geographical area or organization, generalizability is reduced. However, the subsample recruited from Salud provided additional diversity.

Health research could benefit from more widespread reporting and evaluation of recruitment efforts8. This is especially true of studies involving under-represented populations, such as Latinos, who have poorer health outcomes. The ¡Viva Bien! project provides a useful case study of how participation rates may be enhanced by addressing cultural characteristics, and systematically removing obstacles to participation. Future researchers could expand on this work by exploring the relative effectiveness of different contact points (eg, churches, schools, social groups, health fairs, and the Internet) for recruiting minority samples.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant #1 RO1 HL76151-01A1 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. We are grateful to our diligent recruitment staff, especially Breanne Griffin, Sara Hoerlein, and Fabio Almeida. We thank KP Colorado and Salud physicians for their contributions. We are deeply indebted to the wonderful women who participated in this study.

Grant number: R01 HL76151; ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00233259

Footnotes

The authors of this manuscript have no relevant conflict of interest to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Pinn VW, Roth C, Bates AC, et al. [Accessed November 12, 2008];Monitoring adherence to the NIH policy on the inclusion of women and minorities as subjects in clinical research: comprehensive report: Tracking of human subjects research reported in FY 2002 and FY 2003 (on-line) Available at: http://orwh.od.nih.gov/inclusion/Updated_2002-2003.pdf.

- 2.Escobar-Chaves S, Tortolero S, Masse L, et al. Recruiting and retaining minority women: Findings. Ethn Dis. 2007;12:242–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eakin EG, Bull SS, Riley K, et al. Recruitment and retention of Latinos in a primary care-based physical activity and diet trial: The Resources for Health Study. Health Educ Res. 2007;22:361–371. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keyzer J, Melnikow J, Kuppermann M, et al. Recruitment strategies for minority participation: challenges and cost lessons from the POWER interview. Ethn Dis. 2005;15:395–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodríguez MD, Rodríguez J, Davis M. Recruitment of first-generation Latinos in a rural community: the essential nature of personal contact. Fam Process. 2006;45:87–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swanson GM, Ward AJ. Recruiting minorities into clinical trials: Toward a participant-friendly system. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;87:1747–1759. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.23.1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis B, George V, Urban N, et al. Recruitment strategies in the Women’s Health Trial Feasibility Study in Minority Populations. Controlled Clin Trials. 1998;19:461–476. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(98)00031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Froelicher ES, Lorig K. Who cares about recruitment anyway? Patient Educ Couns. 2002;48:97. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00168-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sandler DP. On revealing what we’d rather hide: The problem of describing study participation. Epidemiology. 2002;13:117. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200203000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Narayan KMV, D’Agostino RB, Kirk JK, et al. Disparities in A1C levels between Hispanic and non-Hispanic white adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:240–246. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saydah SH, Eberhardt MS, Loria CM, et al. Age and the burden of death attributable to diabetes in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:714–719. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elley CR, Kenealy T, Robinson E, et al. Glycated heamoglobin and cardiovascular outcomes in people with type 2 diabetes: a large prospective cohort study. Diabet Med. 2008;25:1295–1301. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarkisian CA, Brown AF, Norris KC, et al. A Systematic Review of Diabetes Self-Care Interventions for Older, African American, or Latino Adults. Diabetes Educ. 2003;29:467–479. doi: 10.1177/014572170302900311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toobert DJ, Glasgow RE, Nettekoven LA, et al. Behavioral and psychosocial effects of intensive lifestyle management for women with coronary heart disease. Patient Educ Couns. 1998;35:177–188. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(98)00074-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toobert DJ, Glasgow RE, Radcliffe JL. Physiologic and related behavioral outcomes from the Women’s Lifestyle Heart Trial. Ann Behav Med. 2000;22:1–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02895162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toobert DJ, Glasgow RE, Strycker LA, et al. Physiologic and quality of life outcomes from the Mediterranean Lifestyle Program: a randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:2288–2293. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.8.2288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toobert DJ, Strycker LA, Glasgow RE, et al. Effects of the Mediterranean Lifestyle Program on multiple risk behaviors and psychosocial outcomes among women at risk for heart disease. Ann Behav Med. 2005;29:128–137. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2902_7. PMCID: PMC 1557654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Renaud S, de Lorgeril M, Delaye J, et al. Cretan Mediterranean diet for prevention of coronary heart disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;61:1360S–1367S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/61.6.1360S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ornish D, Brown SE, Scherwitz LW, et al. Can lifestyle changes reverse coronary heart disease? The Lifestyle Heart Trial. Lancet. 1990;336:129–133. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91656-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Welborn TA, Garcia-Webb P, Bonser A, et al. Clinical criteria that reflect c-peptide status in idiopathic diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1983;6:315–316. doi: 10.2337/diacare.6.3.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Osuna D, Barrera M, Jr, Strycker LA, et al. Methods for the cultural adaptation of a diabetes lifestyle intervention for Latinas: An illustrative project. Health Promot Pract. doi: 10.1177/1524839909343279. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toobert DJ, Strycker LA, Glasgow RE, et al. If you build it, will they come? Reach and adoption associated with a comprehensive lifestyle management program for women with type 2 diabetes. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;48:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cuéllar I, Arnold B, Maldonado R. Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans-II: A revision of the original ARSMA scale. Hisp J of Beh Sci. 1995;17:275–304. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ford JG, Howerton MW, Bolen S, et al. Knowledge and access to information on recruitment of underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ) 2005;122:1–11. doi: 10.1037/e439572005-001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robertson NL. Clinical trial participation: viewpoints from racial/ethnic groups. Cancer. 1994;74:2687–2691. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19941101)74:9+<2687::aid-cncr2820741817>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brewster WR, Anton-Culver H, Ziogas A, et al. Recruitment strategies for cervical cancer prevention study. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;85:250–254. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2002.6592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ritzwoller DP, Toobert DJ, Sukhanova A. Economic analysis of the Mediterranean Lifestyle Program for postmenopausal women with diabetes. Diab Educ. 2006;32:761–769. doi: 10.1177/0145721706291757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenwaike I. The status of death statistics from the Hispanic population of the Southwest. Soc Sci Q. 1988;69:722–736. [Google Scholar]