Abstract

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were made from kidney-related neurons in the intermediolateral cell column (IML) in horizontal slices of thoracolumbar spinal cord from adult rats. Kidney-related neurons were identified in vitro subsequent to inoculation of the kidney with a fluorescent, retrograde, transynaptic pseudorabies viral label (i.e., PRV-152). Kidney-related neurons detected in the IML expressed choline acetyltransferase, characteristic of spinal preganglionic motor neurons. Their mean resting potential was -51 ± 4 mV and input resistance was 448 ± 39 MΩ. Both spontaneous inhibitory and excitatory post-synaptic currents (i.e., sIPSCs and sEPSCs) were observed in all neurons. The mean frequency for sEPSCs (3.1 ± 1 Hz) was approximately 2.5 times that for sIPSCs (1.4 ± 0.3 Hz). Application of the glycine and GABAA receptor-linked Cl− channel blocker, picrotoxin (100 μM) blocked sIPSCs, while the ionotropic glutamate receptor antagonist, kynurenic acid (1 mM) blocked all sEPSCs, indicating they were mediated by GABA/glycine and glutamate receptors, respectively. Thus, using PRV-152 labeling allowed whole-cell patch-clamp recording of neurons in the adult spinal cord, which were kidney-related. Excitatory glutamatergic input dominated synaptic responses in these cells, the membrane characteristics of which resembled those of immature IML neurons. Combined PRV-152 pre-labeling and whole-cell patch-clamp recordings may allow more effective analysis of synaptic plasticity seen in adult models of injury or chronic disease.

Keywords: intermediolateral cell column, preganglionic neuron, pseudorabies virus, sympathetic, whole-cell patch-clamp

Introduction

Autonomic preganglionic neurons (i.e. sympathetic and parasympathetic) represent the final common output from the central nervous system to the viscera [5]. In particular, the sympathetic preganglionic neurons (SPN) located in the intermediolateral cell column (IML) of the thoracolumbar spinal cord play a critical role in modulating cardiovascular homeostasis [1]. In particular, SPN activity contributes to systemic blood pressure control by adjusting vascular tone, particularly in the kidneys. Several electrophysiological studies have been conducted using in vitro spinal cord slices from neonatal rats to understand the biophysical characteristics of SPNs [2, 21, 25]. Despite the utility of using spinal cord tissue from neonates, a potential drawback is that the spinal circuitry in neonates may be different than in adults [13, 17]. The electrophysiological properties of neurons that control particular organs are difficult to identify and have not been adequately described in adults using high resolution in vitro recordings. This last point is crucial to understanding how, for instance, sympathetic input to the kidneys regulates blood pressure in normal animals or following spinal trauma [15], which usually necessitates using models in adult animals.

A pseudorabies virus (PRV) construct that expresses the reporter gene for enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP; PRV-152) [24] can be used to selectively target and visualize neurons indirectly coupled to the control of specific viscera. The exclusively retrograde transport of PRV-152 occurs in synaptically linked chains of neurons, with higher order structures becoming labeled at later time-points [3, 4, 10, 12, 18]. Thus second and third order central pre-autonomic neurons that regulate a specific visceral target (i.e., the kidney) can be labeled within the spinal cord. The primary goal of the present study was to develop and verify the utility of a spinal cord slice preparation from adult rats to study the synaptic characteristics of identified kidney-related neurons using whole-cell patch-clamp recordings.

Materials and Methods

Animals and PRV injections

All animal housing conditions, surgical procedures and post-operative care techniques were conducted according to the University of Kentucky Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and the National Institutes of Health Guide animal care guidelines. Young adult female Wistar rats (5-6 wk) were anesthetized with isoflurane 3% in oxygen (AErrane; Baxter Healthcare Corp, Deerfield, IL, USA). A laparotomy was performed to expose the abdominal organs, and 3μl of PRV-152 (108 pfu/ml) was injected into the left kidney using a 30 ga Hamilton syringe (Hamilton, Reno, NV). Two 1 μl injections were uniformly made in the left renal parenchyma at sites on the longitudinal midline of the convex surface of the kidney [7, 26]. Injection sites were located by dividing this midline in thirds and injecting at the rostral and caudal end of the middle third. After rinsing the abdomen with sterile saline, the abdominal muscles were sutured with 3-0 Vycril (Ethicon, Sommerfield, NJ), the field was disinfected with povidone-iodine solution (Nova Plus, Irving, TX), and the skin was closed with Michel wound clips (Roboz, Gaithersburg, MD). For post-operative care, animals were administered 10 ml lactated Ringer's solution (Baxter Healthcare, Deerfield, IL) to maintain hydration.

Perfusion and tissue processing

Animals designated for histology were overdosed with sodium pentobarbital 96 hr post-inoculation (150 mg/kg; Abbott, Chicago, IL) and perfused transcardially with 0.1 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4, followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. The spinal cord from the conus medullaris to the upper thoracic (∼T5) was removed, post-fixed for 4 hours, rinsed in 0.2 M phosphate buffer (PB) overnight, and cryoprotected for at least 48 hours in 20% sucrose in 0.1 M PBS. As previously described [7], the spinal cords were then divided into two 3 cm portions of caudal (S4-T13; lumbosacral) and rostral segments (T12-T5; thoracic) and embedded in gum tragacanth (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in 20% sucrose/PBS for cryosectioning. Both thoracic and lumbosacral segments of cord were serially cryosectioned in the horizontal plane (i.e., longitudinally) at 50 μm and consecutively mounted onto glass slides (Superfrost plus, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) in 5 series of 5 slides.

Immunohistochemistry

For choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) immunostaining, slides with mounted sections were thawed and pre-incubated in 0.1 M PBS containing 0.5% Triton-X and 5% normal donkey serum (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 1 hour, followed by incubation with mouse anti-ChAT (1:100; Millipore, Billerica, Massachusetts, USA) in same buffer overnight at 4°C. The slides were then rinsed before applying donkey anti-mouse conjugated to Texas Red (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA; 1:200) for 3 hours at room temperature. After final rinses, slides were coverslipped using Vectashield mounting medium (Vector, Burlingame, CA) and sealed with Cutex nail hardener.

Spinal cord extraction and slice preparation

Eighty-four hrs after PRV-152 inoculation of the left kidney, animals were deeply anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (150 mg/kg) and perfused transcardially with ice-cold (0–4°C) oxygenated (95% O2-5% CO2) artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing the following (in mM): 124 NaCl, 3 KCl, 26 NaHCO3, 1.4 NaH2PO4, 11 glucose, 1.3 CaCl2, and 1.3 MgCl2, pH 7.3–7.4, with an osmolality of 290–310 mOsm/kg. Transcardial perfusion with cold ACSF may help preserve slice viability during complex dissections [23]. The thoracic (∼T5-13) spinal cord was excised by laminectomy, divided in half and blocked onto an ice-cold sectioning stage filled with oxygenated ACSF. For slicing, the spinal tissue was glued, ventral surface down onto a sectioning block with cyanoacrylate glue and supported along the sides with 2% agar block. Longitudinal slices of 300-400 μm thickness were cut on a vibratome in ice-cold ACSF. The spinal cord slices were allowed to recover in a humidified chamber for a period of 1 hour at room temperature (22-23°C).

Cell identification and whole-cell patch-clamp recordings

The spinal cord slice was placed onto a recording chamber mounted on a fixed stage under an upright fluorescent microscope (Olympus BX51WI) and continuously perfused with oxygenated ACSF at room temperature. Labeled neurons in the IML were identified under a 40× water-immersion objective (NA= 0.8) using a combination of epifluorescence to identify EGFP-containing cells and infrared differential interference contrast (IR-DIC) optics to target specific cells for patch-clamp recordings, similar to previous description in brainstem [6].

For whole-cell patch-clamp recordings, electrodes (2-4 MΩ) were filled with a solution containing the following (in mM): 130 Cs+-gluconate, 1 NaCl, 5 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 1 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 3 CsOH, 2–4 Mg-ATP, and 0.2% biocytin, pH 7.3–7.4, adjusted with 5 M CsOH. Within 1 min of obtaining a whole-cell recording, resting membrane potential was determined by temporarily removing voltage control; input resistance was measured by applying negative and positive rectangular current pulses (200-400 ms) through the recording pipette in current-clamp mode. In voltage-clamp mode, spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents (sIPSCs) were examined at a holding potential of −10 mV, while spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents (sEPSCs) were recorded at −60 mV. Electrophysiological signals were low-pass filtered at 2–5 kHz, recorded using a Multiclamp 700A amplifier (Molecular Devices, Union City, CA), and acquired with pClamp 10 software (Molecular Devices). Synaptic events were analyzed offline using pClamp or MiniAnalysis (Synaptosoft, Decatur, GA). In some experiments, picrotoxin (100 μm) was included in the ACSF to block GABAA and glycine receptors, or kynurenic acid (1 mM) was applied to block ionotropic glutamate receptors.

In addition to identifying cells a priori as EGFP-containing, posthoc identification of recorded neurons was achieved using biocytin in the recording pipette solution, which diffused into the cell during the recording. Following cessation of the recording, spinal tissues were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M PBS for 24 hours. To visualize the recorded biocytin-filled neurons, fixed slices (whole mount) were incubated in avidin–rhodamine conjugated to Texas Red (1:200; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) in PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100 overnight at 4°C.

Results

Distribution and morphology of PRV-152 labeled neurons in the intermediolateral cell column

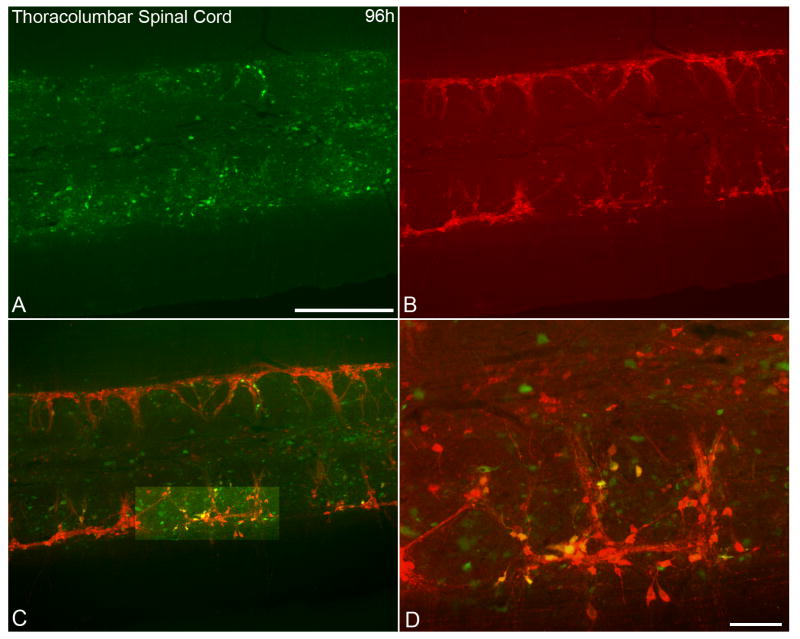

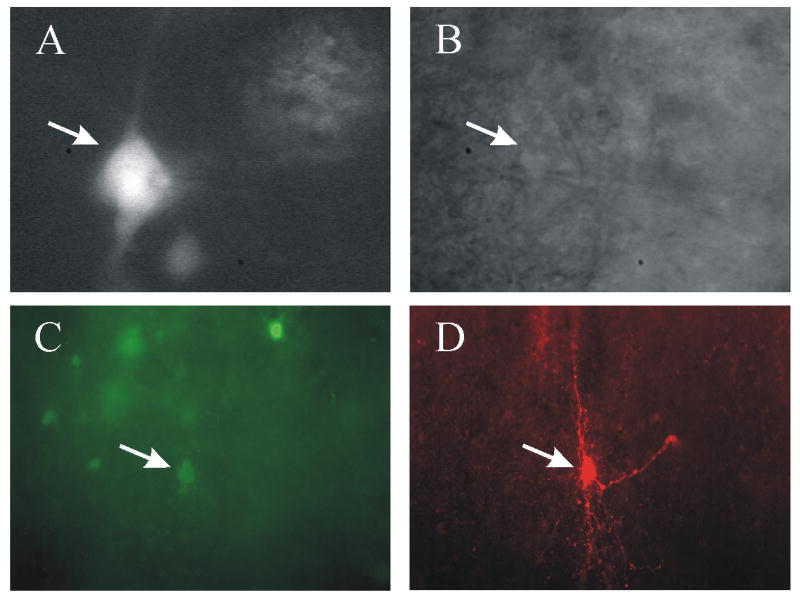

At 96 hrs following inoculation of the left kidney, PRV-152 labeled cells in fixed spinal cord tissue were distributed throughout the IML (Fig 1A). In addition, ChAT immunofluorescence (Fig. 1B) was identified in the IML in the same tissue section. Neurons that were labeled with both ChAT and PRV-152 were abundant (Fig 1 C, D). Neurons labeled with PRV-152 (Fig. 2A, C) were recorded and filled with biocytin (Fig. 2C, D). Identified and recorded cells were located predominately in the lateral edge of the grey matter. The somata of recorded neurons were either triangular or ovoid. Recorded cells typically had three or more primary dendrites (Fig. 2D) which branched within the rostrocaudal orientation of the horizontal slice (Fig. 2A, D).

Figure 1.

Photomicrographs showing identified kidney-related neurons and choline acetyltransferase (ChAT)-like immunoreactivity in a longitudinal horizontal section from the thoracolumbar spinal cord following PRV-152 inoculation into left kidney. A. Expression of enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) in spinal cord neurons 96 h post-inoculation of the kidney with the transsynaptic, retrograde viral label, PRV-152 (green). B. ChAT-like immunoreactivity (red) in the same section as in panel A. C. Image of dual-labeled PRV-152 (green) and ChAT (red) immunofluorescent staining. D. Higher magnification of highlighted region in panel C illustrating co-localization of PRV-152 and ChAT staining. Scale bars = 500 μm in A-C; 100 μm in D.

Figure 2.

Identification and visualization of kidney-related neurons pre-labeled with PRV-152 recorded in slices from adult rat spinal cord. A. Micrograph demonstrating neurons identified with EGFP and targeted for patch-clamp recording (white arrow). The tip of the recording pipette is evident at the right side of the neuron soma. B. Infra-red differential interference contrast (i.e., IR-DIC) image of the same neuron (white arrow) targeted for recording. C. Whole-mount view of a spinal cord slice (300 μm) after fixation showing EGFP-labeled neurons 84 h after inoculation of the left kidney. The neuron indicated with an arrow was recorded and filled with biocytin. D. The same slice and plane of section viewed with optics demonstrating the biocytin label (i.e. avidin-rhodamine fluorescence) in the recorded cell, indicated by the arrow.

General electrophysiological properties of SPNs

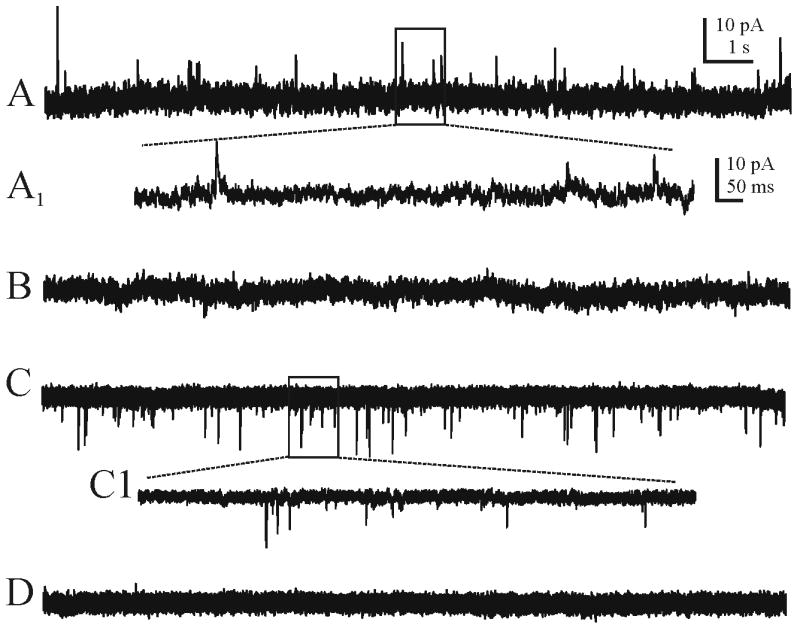

Whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings of synaptic currents were made from 11 identified PRV-152 labeled neurons in the IML of thoracolumbar spinal cord slices from adult rats (Fig 2). The resting membrane potential of labeled neurons was -51 ± 4 mV (range from -43 to -58 mV) and input resistance was 448 ± 39 MΩ (range from 350 to 650 MΩ). All PRV-152 labeled neurons displayed sIPSCs when voltage-clamped at −10 mV. The sIPSC frequency was 1.4 ± 0.3 Hz (range from 0.6 to 2.2 Hz) and amplitude was 19 ± 4.5 pA (range from 6.3 to 33 pA; Fig. 3A). Application of the glycine/GABAA receptor-linked Cl− channel blocker, picrotoxin (100 μM), blocked all sIPSCs (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Examples of spontaneous inhibitory and excitatory post-synaptic currents (i.e., sIPSCs and sEPSCs) recorded from kidney-related neurons pre-labeled with PRV-152. A. Continuous recording of sIPSCs observed at a holding potential of -10 mV. A1 is an expanded portion of the boxed area in A. B. The same neuron after application of the picrotoxin (100 μM), which blocked all sIPSCs. C. Continuous recording of sEPSCs observed at a holding potential of -60 mV. C1 is an expanded portion of the boxed area in C. D. The same neuron after application of kynurenic acid (1 mM), which blocked all sEPSCs. Recording pipette contained Cs+ in all records.

All neurons also received sEPSCs when voltage-clamped at −60 mV (Fig. 3C). The sEPSC frequency was 3.1 ± 1 Hz (range from 0.5 to 6.5 Hz) and amplitude was 11 ± 2 pA (range from 8 to 17 pA. Application of the broad spectrum ionotropic glutamate receptor antagonist, kynurenic acid (1 mM) abolished all sEPSCs (Fig. 3D).

Depolarization from a holding potential of −60 mV produced transient inward currents that were blocked by the selective Na+ channel antagonist tetrodotoxin (TTX; 1 μM). These results confirmed that retrogradely infected neurons in the spinal cord of adult rats maintained synaptic connectivity and could be targeted for physiological analysis.

Discussion

Pre-labeled renal-related SPNs in longitudinal thoracolumbar spinal cord slices from adult rats have the attributes of preganglionic neurons by virtue of their anatomical location and ChAT content [22]. Resting membrane potential, obtained prior to full equilibration of Cs+ within the cell, was similar to those reported by others in recordings from neonatal rats using whole-cell patch-clamp recordings [19] or intracellular recording [21]. Input resistance in the present study (448 ± 39 MΩ) was higher than in some previous studies [21]. This discrepancy is likely due to the different recording configurations used (i.e., whole-cell patch-clamp versus intracellular). Input resistance was somewhat less than that found in whole-cell records in neonatal preparations [19] and this could be due to either animal age or to slice orientation. The longitudinal slice preparation preserved much of the dendritic tree, which therefore may have contributed to lower input resistance measurements. Correlation of cell morphology with electrophysiological features will be further addressed in future experiments with additional recordings.

The whole-cell method allowed measurement of discrete synaptic events. As in most central areas, sEPSCs were eliminated by kynurenic acid and sIPSCs were blocked by picrotoxin. These events were likely mediated by glutamate and glycine or GABA, consistent with findings from neonates [21]. Interestingly, glutamatergic input exceeded inhibitory input. This is consistent with tonic activation of these neurons, the synaptic drive for which is maintained in the in vitro slice preparation.

Like previous studies [11, 24], the present work illustrates that fluorescent viral transneuronal tracers like PRV-152 are powerful tools for discretely labeling and recording from specific neuronal subpopulations for in vitro physiological studies, particularly in the early phases of the infection--in these studies at about 3.5 days post-inoculation. α-Herpesvirus-infected cultured peripheral neurons exhibit altered electrical activity compared to uninfected neurons [9, 14, 16]. However, like in other central neurons [10, 11, 24], electrophysiological properties of IML neurons were consistent with findings by others in unlabeled (albeit immature) cells, suggesting the virus was not obviously detrimental to maintenance of basic membrane or synaptic properties. Limitations to the utility of PRV in vitro studies may arise at longer inoculation time points (i.e., >4 days), when preganglionic neurons begin to show cytopathic effects of the virus including necrosis [20]. Despite the exclusively synaptic mode of viral uptake, transport, and cellular labeling [8, 27], which results in positive identification of kidney-related spinal neurons, it is still difficult to visually distinguish preganglionic motor neurons from interneurons, which may also be labeled subsequent to the motor neuron pool. Despite these limitations, PRV-152 has proven valuable in characterizing synaptic input to kidney-related IML neurons in adults, recordings from which have been problematic previously. Use of the fluorescent label, longitudinal slices, and transcardial perfusion with ice-cold ACSF prior to removing the spinal cord may all have contributed to the success in recording from adult tissue here. Combined PRV-152 labeling and whole cell patch recording techniques may ultimately allow analysis of possible synaptic changes in renal SPN in adult injury and disease paradigms.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Lynn Enquist (Princeton University) for the PRV-152. Funded by PVA grant #2561 (H. Duale), NIHLBI, 1R21HL091293 (A.V. Derbenev), NINDS, R01 NS049901 (A.G. Rabchevsky), NIDDK R01 DK056132 (B.N. Smith), and NINDS, P30 NS051220.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Anderson CR, McLachlan EM, Srb-Christie O. Distribution of sympathetic preganglionic neurons and monoaminergic nerve terminals in the spinal cord of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1989;283:269–284. doi: 10.1002/cne.902830208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cammack C, Logan SD. Excitation of rat sympathetic preganglionic neurones by selective activation of the NK1 receptor. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1996;57:87–92. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(95)00103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Card JP, Rinaman L, Lynn RB, Lee BH, Meade RP, Miselis RR, Enquist LW. Pseudorabies virus infection of the rat central nervous system: ultrastructural characterization of viral replication, transport, and pathogenesis. J Neurosci. 1993;13:2515–2539. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-06-02515.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ch'ng TH, Spear PG, Struyf F, Enquist LW. Glycoprotein D-independent spread of pseudorabies virus infection in cultured peripheral nervous system neurons in a compartmented system. J Virol. 2007;81:10742–10757. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00981-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coote JH. The organisation of cardiovascular neurons in the spinal cord. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 1988;110:147–285. doi: 10.1007/BFb0027531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Derbenev AV, Monroe MJ, Glatzer NR, Smith BN. Vanilloid-mediated heterosynaptic facilitation of inhibitory synaptic input to neurons of the rat dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus. J Neurosci. 2006;26:9666–9672. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1591-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duale H, Hou S, Derbenev AV, Smith BN, Rabchevsky AG. Spinal cord injury reduces the efficacy of pseudorabies virus labeling of sympathetic preganglionic neurons. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009;68:168–178. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181967df7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Enquist LW. Exploiting circuit-specific spread of pseudorabies virus in the central nervous system: insights to pathogenesis and circuit tracers. J Infect Dis. 2002;186 2:S209–214. doi: 10.1086/344278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fukuda J, Kurata T. Loss of membrane excitability after herpes simplex virus infection in tissue-cultured nerve cells from adult mammals. Brain Research. 1981;211:235–241. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)90090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glatzer NR, Hasney CP, Bhaskaran MD, Smith BN. Synaptic and morphologic properties in vitro of premotor rat nucleus tractus solitarius neurons labeled transneuronally from the stomach. J Comp Neurol. 2003;464:525–539. doi: 10.1002/cne.10831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Irnaten M, Neff RA, Wang J, Loewy AD, Mettenleiter TC, Mendelowitz D. Activity of cardiorespiratory networks revealed by transsynaptic virus expressing GFP. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:435–438. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.1.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jansen AS, Farwell DG, Loewy AD. Specificity of pseudorabies virus as a retrograde marker of sympathetic preganglionic neurons: implications for transneuronal labeling studies. Brain Res. 1993;617:103–112. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90619-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kerkut GA, Bagust J. The isolated mammalian spinal cord. Prog Neurobiol. 1995;46:1–48. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(94)00055-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kiraly M, Dolivo M. Alteration of the electrophysiological activity in sympathetic ganglia infected with a neurotropic virus. I. Presynaptic origin of the spontaneous bioelectric activity. Brain Research. 1982;240:43–54. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90642-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krassioukov AV, Johns DG, Schramm LP. Sensitivity of sympathetically correlated spinal interneurons, renal sympathetic nerve activity, and arterial pressure to somatic and visceral stimuli after chronic spinal injury. J Neurotrauma. 2002;19:1521–1529. doi: 10.1089/089771502762300193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mayer ML, James MH, Russel RJ, Kelly JS, Pasternak CA. Changes in excitability induced by herpes simplex viruses in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. J Neurosci. 1986;6:391–402. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-02-00391.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nohda K, Nakatsuka T, Takeda D, Miyazaki N, Nishi H, Sonobe H, Yoshida M. Selective vulnerability to ischemia in the rat spinal cord: a comparison between ventral and dorsal horn neurons. Spine. 2007;32:1060–1066. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000261560.53428.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pickard GE, Smeraski CA, Tomlinson CC, Banfield BW, Kaufman J, Wilcox CL, Enquist LW, Sollars PJ. Intravitreal injection of the attenuated pseudorabies virus PRV Bartha results in infection of the hamster suprachiasmatic nucleus only by retrograde transsynaptic transport via autonomic circuits. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2701–2710. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-07-02701.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pickering AE, Spanswick D, Logan SD. Whole-cell recordings from sympathetic preganglionic neurons in rat spinal cord slices. Neurosci Lett. 1991;130:237–242. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90405-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rinaman L, Card JP, Enquist LW. Spatiotemporal responses of astrocytes, ramified microglia, and brain macrophages to central neuronal infection with pseudorabies virus. J Neurosci. 1993;13:685–702. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-02-00685.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sah P, McLachlan EM. Membrane properties and synaptic potentials in rat sympathetic preganglionic neurons studied in horizontal spinal cord slices in vitro. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1995;53:1–15. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(94)00161-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schafer MK, Eiden LE, Weihe E. Cholinergic neurons and terminal fields revealed by immunohistochemistry for the vesicular acetylcholine transporter. I Central nervous system. Neuroscience. 1998;84:331–359. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00516-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith BN, Armstrong WE. Tuberal supraoptic neurons –I. Morphological and electrophysiological characteristics observed with intracellular recording and biocytin filling in vitro. Neuroscience. 1990;38:15. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith BN, Banfield BW, Smeraski CA, Wilcox CL, Dudek FE, Enquist LW, Pickard GE. Pseudorabies virus expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein: A tool for in vitro electrophysiological analysis of transsynaptically labeled neurons in identified central nervous system circuits. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:9264–9269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.9264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spanswick D, Logan SD. Sympathetic preganglionic neurones in neonatal rat spinal cord in vitro: electrophysiological characteristics and the effects of selective excitatory amino acid receptor agonists. Brain Res. 1990;525:181–188. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90862-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang X, Neckel ND, Schramm LP. Spinal interneurons infected by renal injection of pseudorabies virus in the rat. Brain Res. 2004;1004:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ugolini G. Use of rabies virus as a transneuronal tracer of neuronal connections: implications for the understanding of rabies pathogenesis. Dev Biol (Basel) 2008;131:493–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]