Abstract

Prenatal stress has been associated with increased vulnerability to psychiatric disturbances including schizophrenia, depression, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and autism. Elevated maternal circulating stress hormones alter development of neural circuits in the fetal brain and cause long-term changes in behaviour. The aim of the present study was to investigate whether mild prenatal stress increases the vulnerability of dopamine neurons in adulthood. A low dose of 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA, 5 μg/4 μl saline) was unilaterally infused into the medial forebrain bundle of nerve fibres in the rat brain in order to create a partial lesion of dopamine neurons which was sufficient to cause subtle behavioural deficits associated with early onset of Parkinson’s disease without complete destruction of dopamine neurons. Voluntary exercise appeared to have a neuroprotective effect resulting in an improvement in motor control and decreased asymmetry in the use of left and right forelimbs to explore a novel environment as well as decreased asymmetry of tyrosine hydroxylase-positive cells in the substantia nigra pars compacta and decreased dopamine cell loss in 6-OHDA-lesioned rats. Prenatal stress appeared to enhance the toxic effect of 6-OHDA possibly by reducing the compensatory adaptations to exercise.

Keywords: Prenatal, Stress, Dopamine, 6-OHDA, Lesion, Exercise, Running

Introduction

Prenatal stress has been associated with increased vulnerability to psychiatric disturbances such as schizophrenia, depression, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and autism (Kinney 2001; Weinstock 2001; Khashan et al. 2008; Weinstock 2008; Kinney et al. 2008). There is increasing evidence to suggest that prenatal stress may have long-term effects on brain structure and function (Van den Hove et al. 2006). Excess circulating maternal stress hormones can alter the programming of fetal neurons and interfere with development of the nervous system (Kinney et al. 2008). Together with genetic factors, the nature of the postnatal environment, the quality of maternal attention, and stress experienced in utero can determine the behaviour of offspring (Weinstock 2008). Vulnerability to prenatal stress increases towards the third trimester of pregnancy when the placental barrier becomes less active and the fetus is exposed to maternal stress hormones (Kinney et al. 2008). Maternal anxiety in late pregnancy has been shown to produce anxiety-like behaviour as well as alterations in plasma cortisol in the offspring, reflecting altered regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary- adrenal (HPA) axis (O’Connor et al. 2005; Weinstock 2008). Similar changes in HPA axis activity and behaviour have been induced by prenatal stress in laboratory rodents and non-human primates (Mabandla et al. 2008; Weinstock 2008). The nature of such changes depends on the timing of the maternal stress, its intensity and duration, as well as the gender of the offspring (Weinstock 2008).

The present study set out to investigate whether mild prenatal stress increases the vulnerability of dopamine neurons to toxic insult in adulthood. The prenatal stress model used in this study has been described previously (Mabandla et al. 2008). An established rodent model for Parkinson’s disease was used to assess vulnerability of dopamine neurons (Mabandla et al. 2004; Ungerstedt 1971). Previous studies have mainly used large doses of the neurotoxin, 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA), that cause almost complete loss of substantia nigra pars compacta dopamine neurons which is comparable to end stage Parkinson’s disease (Henderson et al 2003; Emborg 2004; Mabandla et al. 2004; Howells et al. 2005). However, in order to mimic preclinical Parkinson’s disease, much lower doses of 6-OHDA were used in order to create a partial lesion which is sufficient to cause subtle behavioural deficits associated with early onset of Parkinson’s disease but not total loss of dopamine neurons (Truong et al. 2006). Adult offspring of maternally stressed rats were subjected to unilateral infusion of 6-OHDA into the medial forebrain bundle of nerve fibers two weeks prior to behavioural assessment of ability to initiate movement and forelimb asymmetry as well as determination of dopamine neuron survival. Since previous studies have shown that the toxic effects of 6-OHDA can be partially prevented by voluntary exercise (Mabandla et al. 2004; Howells et al. 2005), prenatally stressed and control rats were allowed to exercise voluntarily for 1 week prior to, and for two weeks following infusion of the toxin in order to determine whether adverse effects of prenatal stress could be reversed by exercise.

Method

Animals

Forty-eight adult Sprague Dawley rats (24 female and 24 male) were housed under standard laboratory conditions with a 12-h (06h00–18h00) light/dark cycle and free access to commercial pellet food and tap water.

Female rats were housed together (four per cage) for eight weeks to synchronise their ovarian cycles. They were then placed in individual cages and vaginal smears were taken daily for 4 days to monitor their oestrous cycle. A rat’s ovarian cycle is normally 4–5 days long and is divided into proestrus, oestrus, and dioestrus which is a 48-h period divided into dioestrus 1 and dioestrus 2 (Marcondes et al. 2002). Ovulation occurs from the commencement of proestrus to the end of oestrus (Marcondes et al. 2002). On the day of proestrous, a male, randomly selected, was placed in a proestrus female’s cage. Since the neonatal HPA axis is functional in the last week of gestation, the pregnant dams were subjected to mild stress during the last week of gestation i.e. from gestational day 14 to 19, as described previously (Mabandla et al. 2008). The presence of vaginal plugs was used to determine the exact day of conception. The males were immediately removed from the breeding cage and this was called gestational day 0 (GND0).

Prenatal stress protocol

On GND14, the female rats were divided into two groups, non-stressed rats (n=18) and mildly stressed rats (n=18). At 9 am, the mildly stressed rats were taken to a room where the 12 h light/dark cycle was shifted by 7 h. On GND15 the reversed light/dark cycle was maintained. At 9 am on GND16 the light/dark cycle was changed back to the original 6 am to 6 pm cycle. On GND17, food was removed from the cages for a period of 24 h. On GND18, the rats received multiple stressors: they were placed in clean cages for a period of 5 min and then returned to their home cage for 5 min. Next, they were handled for 5 min and then placed in a cage in which the floor was covered with wire mesh for 5 min after which they were returned to their home cages.

Postnatal handling

On postnatal day 2 (P2), the pups were sexed and litters culled to eight males. Stress during gestation affects not only the foetus but also produces long-lasting effects on the emotional reactivity of the dam (Darnaudéry et al. 2004). It was therefore decided to cross-foster the pups of the stressed dams onto non-stressed dams, in order to ensure that any effects measured were due to prenatal stress only. The stressed dams were removed from the study. The pups of the non-stressed dams were cross-fostered onto different control dams to ensure an appropriate control. Only pups from the same litter were “cross-fostered” onto a dam. These dams and “cross-fostered” pups were housed under normal conditions. Litters were kept with foster mothers until they were weaned at P21, after which the pups were housed 4 per cage and received food and water ad libitum.

Exercise

On P47, the rats housed 4 per cage were moved to a room with a 23h00–11h00 light/dark cycle. On P53, 18 prenatally stressed rats and 18 non-stressed rats were weighed and divided into two groups each. Nine prenatally stressed rats and 9 non-stressed rats were placed in individual cages that had running wheels attached. The remaining rats, nine in each group, were placed individually in plexiglass cages. The rats received food and water ad libitum. The running wheels were fitted with counters which measured the revolutions made by the rats. One complete revolution was one meter in distance. Running in the wheels was recorded daily between 10h00 and 11h00 which was 1 h before the dark cycle began. On P60, the rats in the four groups were weighed and taken to the laboratory where they were to undergo stereotaxic surgery.

Stereotaxic surgery

As 6-OHDA is also toxic to norepinephrine neurons, a norepinephrine transporter blocker, desipramine (15 mg/kg, Sigma, U.S.A), was injected intraperitoneally 30 min before 6-OHDA infusion. The rats were anaesthetised using a mixture of oxygen and halothane administered via a calibrated Blease Vaporiser (DATUM). After exposing the skull, a burr-hole was constructed above the target area (see coordinates below). Both prenatally stressed and non-stressed rats received 6-OHDA HCl (5 μg/4 μl saline; Sigma, U.S.A) infusion unilaterally (0.5 μl/min) using a 32G dental needle into the left medial forebrain bundle (4.7 mm anterior to lambda, 1.6 mm lateral to midline and 8.4 mm ventral to dura, Paxinos and Watson 1986; Guan et al 2000). The infusion needle was left in the medial forebrain bundle for 1 min before infusion began. After the infusion, the needle was left in position for a further 5 min so as to allow time for the neurotoxin to diffuse into the tissue. The needle was then retracted and the burr-hole closed with bone wax. After suturing the wound, the rats were allowed to recover in plexiglass cages (one rat per cage) for 2 h in the surgical laboratory before they were returned to their respective cages. The number of revolutions produced by the rats in the cages with attached running wheels was recorded daily for a further two weeks following surgery.

Behavioural tests

On P74, the rats were weighed and taken to a behavioural room at least one hour before testing so as to acclimatize to the new environment. Tests to be conducted included the forelimb akinesia test (step test), the limb use asymmetry test (cylinder test) and the open field test. The light in the behavioural room had an intensity of 48 lux. The equipment used in the tests was cleaned with 70% alcohol between tests.

Step test

The step test was designed to measure movement initiation and thus provided a measure of forelimb impairment which indirectly reflected the extent of the lesion of nigrostriatal dopamine neurons in each hemisphere (Schallert and Tillerson 2000). The rat was held by the torso such that the hind limbs were in mid air and the weight of the rat centred over one forelimb (Tillerson et al 2001). To minimize head turning, the head and the forelimb that was not being tested were gently oriented forward by means of the thumb and index finger (Schallert and Woodlee 2005). The length of the step taken by each forelimb was measured. Each forelimb was tested three times and the mean was recorded as the step length for each limb.

Cylinder test

Each rat was placed in a plexiglass cylinder, 30 cm high by 20 cm in diameter with the bottom and top end open. A video camera was used to record the number of times the rat’s forelimbs touched the cylinder wall while still standing on its hindlimbs. Each test lasted 5 min which allowed sufficient time to assess forelimb use while exploring the cylinder before the rats habituated to the environment and became inactive. Limb use asymmetry was scored as the percentage preferential placement of the left unimpaired forelimb on the wall of the cylinder (Tillerson et al 2001; Schallert and Woodlee 2005), calculated as

where ipsi stands for the limb ipsilateral to the lesioned hemisphere which is the unimpaired limb and contra (contralateral limb) is the limb contralateral to the lesioned hemisphere and therefore the impaired limb. After the test, the rats were returned to their cages in the holding room where they remained for 2 h before being tested in the open field apparatus.

Open field test

The open field apparatus was used to measure the activity of the rats in a novel environment (Colorado et al. 2006) which includes locomotor activity (line crossing), exploration (rearing) and fear and anxiety (centre square entries, McFadyen-Leussis et al. 2004). The open field activity box measured 1 m×1 m×0.5 m with charcoal grey fibreglass flooring and the four lateral sides painted cream. The inner zone measured 0.7 m×0.7 m. Each rat was tested for a period of 5 min. To aid with the analysis, a video camera was used to record behavioural activity. Following the tests, the rats were returned to the animal facility. On P75 the rats were sacrificed by transcardial perfusion and the brains removed for tyrosine hydroxylase immunohistochemistry.

Transcardial perfusion

The rats were deeply anaesthetized and perfused with 0.15 M Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS, 150 ml) followed by 4% parafomaldehyde (MERCK, Germany, 300 ml) until the animal became rigid. The skull was removed and the brain scooped from the calverium. The brains were post fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h and then cryoprotected in 20% sucrose for 48 h after which the brains were stored in a −80°C freezer for tyrosine hydroxylase immunohistochemistry.

Tyrosine hydroxylase immunohistochemistry

Sixty micron (μm) sections were cut antero-posterially until the striatum was visible. A metal prong (1 mm in diameter) was driven through the striatum to the back of the right hemisphere (non-lesioned hemisphere). The hole was used as a marker to differentiate the two hemispheres after immunohistochemistry. The brain was sliced coronally and striatal and substantia nigra tissue was collected in the −20°C environment of the cryostat machine.

The slices were washed in PBS (0.15 M, pH 7.6) and then incubated for 15 min in 3% hydrogen peroxide to quench endogenous peroxidase activity. Following quenching, the slices were washed several times in PBS and then incubated for 1 h in blocking solution containing PBS, normal horse serum (Vectastain) and Triton-X. Following the blocking step, the slices were incubated in primary monoclonal anti-tyrosine hydroxylase mouse antibody (Sigma, U.S.A) at 1:16000 dilution. The slices were kept at 4°C for 2 days. The slices were washed in PBS and then incubated in biotinylated secondary antibody (Vectastain) for 90 min. After washing with PBS, the slices were incubated for 90 min in Vectastain PK-6102, Mouse IgG ABC reagent (Vectastain) prepared 90 min before use. The slices were washed and then incubated with diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB) in Tris buffer (pH7.2, Sigma, USA) at room temperature for 10 min or until staining appeared. The slices were washed 6 times with distilled water and then mounted onto gelatinized glass slides (10 g commercial gelatine in 500 ml distilled water).

The slides were placed in glass slide holders, dehydrated in increasing concentrations of ethanol (96–100%) for 1 min in each concentration. The slides were cleared in xylol for 2 min and then cover slips were placed over the slices using Entellan (MERCK, Germany).

The tyrosine hydroxylase positive dopamine neurons in the substantia nigra of both hemispheres were counted using a Nikon Microphot-fx microscope (10× magnification). Only complete dopamine neurons with stained cell bodies, dendrites and axons were counted.

Statistical analysis

Repeated measures analysis of variation (ANOVA) was used to compare daily distance travelled in the running wheels by prenatally stressed and non-stressed rats. A paired t-test was used to compare left and right forelimb step length. Two-way factorial ANOVA was performed on the behavioural and tyrosine hydroxylase data with “stress” and “exercise” as between rat factors. Significant main effects or interaction were followed by Tukey HSD test for multiple comparisons of mean values. Results are reported as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

Results

Locomotor activity

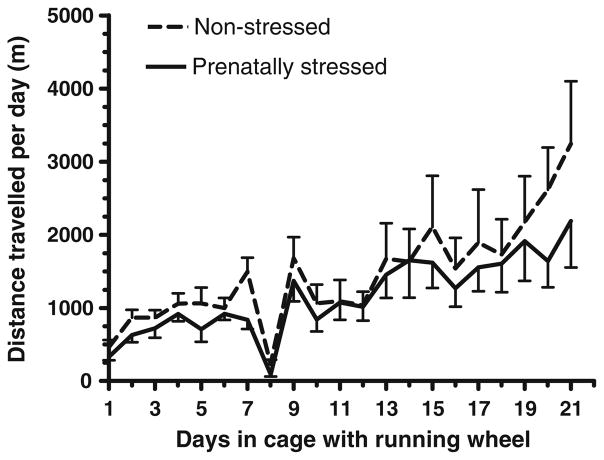

There was no significant difference between the mean distance travelled by the prenatally-stressed rats and the non-stressed rats that were housed in cages with attached running wheels (Fig. 1). The mean number of revolutions of the running wheels increased steadily from day 1 to day 7 in the cages with attached running wheels. Following stereotaxic surgery (Day 7), there was a dramatic decrease in the mean distance travelled by the rats on day 8. Both the non-stressed rats and the prenatally-stressed rats regained pre-lesion levels of activity in the running wheels 3 days later (Day 10).

Fig. 1.

Mean daily distance travelled by prenatally stressed rats (n=9) and non-stressed rats (n=9)

Rat weights

There was no significant difference between the weights of prenatally stressed rats and non-stressed rats at any stage of the study.

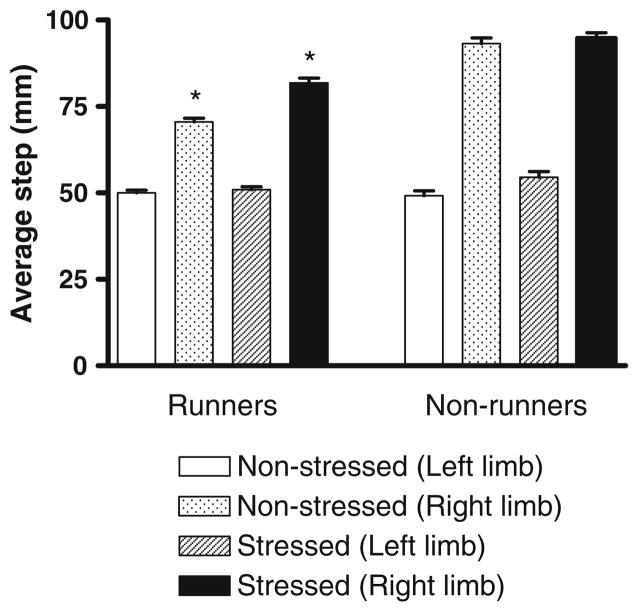

Step test

The step taken by the impaired (right) forelimb whose motor function is controlled by the lesioned hemisphere was significantly longer than the step taken by the unimpaired (left) forelimb that is controlled by the non-lesioned hemisphere in all rats (Fig. 2, P<0.0001). Prenatal stress and exercise did not affect the step length of the left (unimpaired) forelimb. However, exercise significantly reduced the step length of the right (impaired) forelimb (Fig. 2, P<0.0001) while prenatal stress significantly increased the right forelimb step length (P<0.01). This effect was mainly due to prenatal stress reducing the beneficial effect of exercise, as indicated by the significant interaction between stress and exercise (Fig. 2, P<0.005). Post-hoc analysis revealed that both stressed and non-stressed exercised rats differed from all other groups (P<0.005). The step taken by the impaired forelimb (right) of both the prenatally stressed and non-stressed runners was significantly shorter than the step taken by the non-runners. The step taken by the impaired forelimb (right) of the prenatally stressed runners was significantly longer than the step taken by the impaired limb of the non-stressed runners (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Average length of step taken by non-stressed runners (n=9), prenatally stressed runners (n=9), non-stressed non-runners (n=9) and prenatally stressed non-runners (n=9). The mean step length of the left forelimb of all groups was significantly shorter than the step length of the right forelimb (paired t-test, p<0.0001). Two-way ANOVA of the right forelimb step length revealed significant effects of stress (F(1,32)=7.67, P<0.01) and exercise (F(1,32)=72.4, P<0.0001) as well as a significant interaction between stress and exercise (F(1,32)=9.51, P<0.005). *Significantly different from all other groups (Tukey HSD post-hoc test, p<0.005)

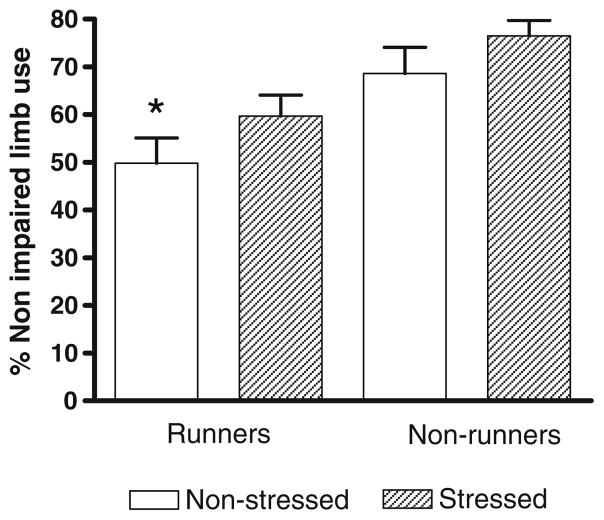

Cylinder test

Wall touch

Exercise significantly reduced the percentage use of the unimpaired forelimb (Fig. 3, P<0.005). There was an overall tendency for prenatal stress to increase use of the unimpaired forelimb but this was not significant (P=0.078). Non-stressed runners used the unimpaired forelimb significantly less than the non-stressed non-runners (P<0.005) for placement on the wall of the cylinder. Prenatal stress appeared to reduce the beneficial effect of exercise, since prenatally stressed runners used their unimpaired forelimb significantly more frequently than non-stressed runners (Fig. 3, P<0.05).

Fig. 3.

Percentage use of unimpaired limb to touch the wall of the cylinder while the rat stands on its hindlimbs. Exercise significantly reduced the percentage use of the unimpaired forelimb (2-way ANOVA, F(1,50)=13.1, P<0.005). *Significantly different from stressed runners (Tukey HSD post-hoc test, P<0.05) and non-stressed non-runners (Tukey HSD post-hoc test, P<0.005)

Open field test

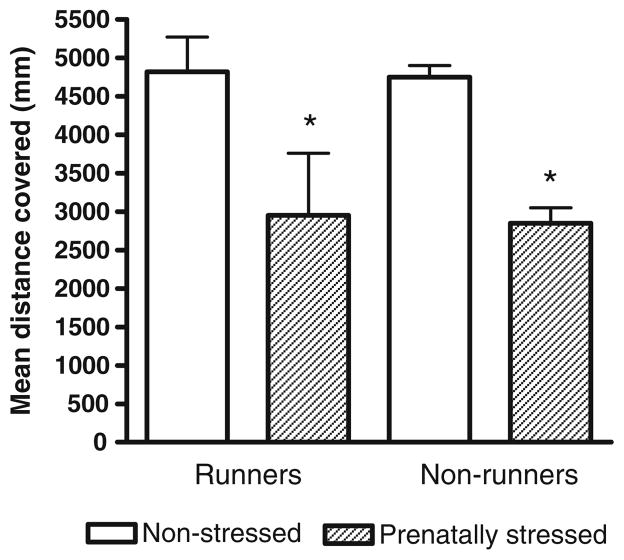

Total distance

A 2-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of stress on distance travelled in the open field (F(1,32)=15.43, P<0.0005). The mean distance travelled by the prenatally stressed rats was significantly less than the distance covered by the non-stressed rats (Fig. 4, P<0.05).

Fig. 4.

Total distance travelled by prenatally stressed and non-stressed rats that had access to running wheels compared to rats that did not. A 2-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of stress on distance travelled in the open field (F(1,32)=15.43, P<0.0005). *Significantly different from non-stressed rats (Tukey HSD test, P<0.05)

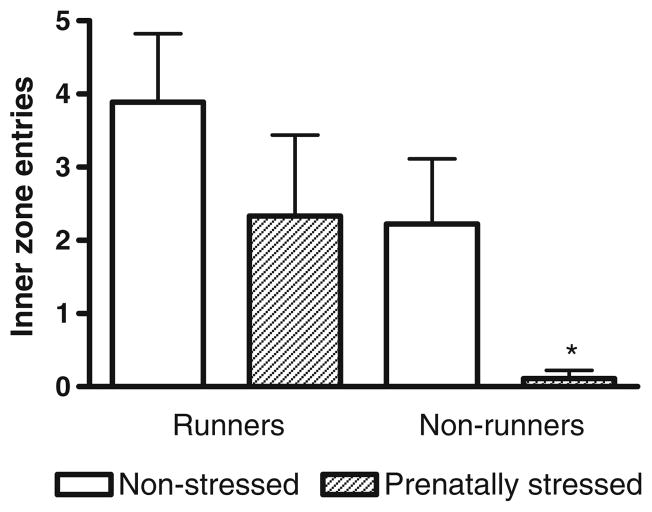

Entries into the inner zone of the open field

Exercise significantly increased the number of entries into the inner zone of the open field while prenatal stress significantly reduced the number of entries (Fig. 5, P<0.05).

Fig. 5.

The number of times prenatally stressed and non-stressed rats entered the inner zone of the open field. Two-way ANOVA revealed significant effects of exercise (F(1,32)=5.20, P<0.05) and stress (F(1,32)=4.6, P<0.05). *Significantly different from non-stressed runners (P<0.05)

Rearing in the open field

There was no significant effect of prenatal stress or exercise on the number of times the rats reared during the 5-min test in the open field (Table 1)

Table 1.

The number of rears made by prenatally stressed and non-stressed rats that either had access to running wheels or not, in a 5-min interval in the open field

| Rat | Runners | Non-runners |

|---|---|---|

| Non-stressed | 6.11±1.27 | 4.67±1.28 |

| Prenatally stressed | 5.11±1.02 | 4.33±0.87 |

Results are mean ± SEM (N=9)

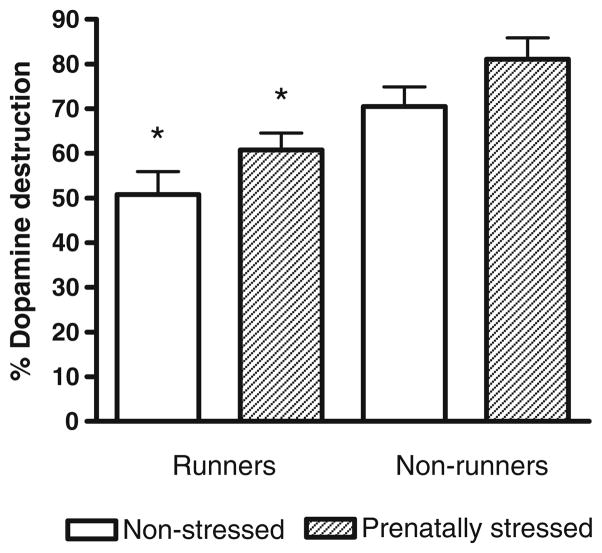

Tyrosine hydroxylase immunohistochemistry

Dopamine neuron destruction in the lesioned hemisphere was calculated as a percentage of the number of tyrosine hyroxylase positive cells in the non-lesioned hemisphere. Exercise significantly reduced dopamine neuron destruction in prenatally stressed and non-stressed rats (Fig. 6, P<0.0001) while prenatal stress significantly enhanced the toxic effect of 6-OHDA in both exercised and non-exercised rats (P<0.005).

Fig. 6.

Percentage loss of dopamine neurons in the lesioned hemisphere expressed as a percentage of the non-lesioned hemisphere of prenatally stressed and non-stressed rats, half of whom were allowed to exercise in running wheels. A two-way ANOVA revealed significant effects of stress (F(1,32)=12.1, P<0.005) and exercise (F(1,32)=49, P<0.0001). Post-hoc Tukey HSD test revealed that both non-stressed runners and stressed runners had suffered significantly less destruction of dopamine neurons than the corresponding non-runners (P<0.0005). *Significantly different from corresponding non-runners (Tukey HSD test, P<0.0005)

The actual number of completely stained tyrosine hydroxylase-positive cells observed in 60 μm sections of rat midbrain was significantly lower in the left (lesioned) substantia nigra pars compacta of prenatally stressed non-runners than in non-stressed non-runners or stressed runners (Table 2, P<0.0005). Exercise decreased the dopamine cell count in the right (non-lesioned) substantia nigra pars compacta of non-stressed runners, thereby decreasing the left–right forelimb asymmetry and stress prevented this compensatory adaptation from occurring (Table 2). The dopamine cell count in the non-lesioned substantia nigra pars compacta of prenatally stressed runners was not significantly different from non-runners.

Table 2.

Dopamine cell count in lesioned and non-lesioned substantia nigra pars compacta of prenatally stressed and non-stressed rats

| Rat | Lesionedhemisphere |

Non-lesionedhemisphere |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Runners | Non-runners | Runners | Non-runners | |

| Non-stressed | 9.31±0.96 | 8.20±0.48 | 19.31±0.97b | 27.67±0.56 |

| Prenatally stressed | 10.92±0.57 | 5.33±0.18a | 27.54±0.51 | 28.61±1.42 |

Two-way ANOVA of dopamine cell count in the left (lesioned) substantia nigra pars compacta of prenatally stressed and non-stressed rats revealed a significant effect of exercise (F(1,32)=29.4, P<0.0001) and a significant interaction between prenatal stress and exercise (F(1,32)=13.1, P<0.001). Post-hoc Tukey HSD test revealed significant difference between dopamine cell count in the left (lesioned) substantia nigra pars compacta of stressed runners and stressed non-runners (P<0.0005). Stressed non-runner dopamine cell counts in the left (lesioned) substantia nigra were lower than non-stressed non-runners (P<0.05). Two-way ANOVA of dopamine cell count in the right (non-lesioned) substantia nigra pars compacta of prenatally stressed and non-stressed rats revealed significant effects of stress (F(1,32)= 23.7, P<0.0001) and exercise (F(1,32)=25.0, P<0.0001) and a significant interaction between stress and exercise (F(1,32)=14.9, P<0.001). Results are mean ± SEM (n=9)

Significantly lower than other lesioned substantia nigra TH-positive cell counts (Tukey HSD post-hoc test, P<0.05)

Significantly lower than other non-lesioned substantia nigra TH-positive cell counts (Tukey HSD post-hoc test, P<0.0005)

Discussion

The present findings provide further evidence to support the suggestion (Mabandla et al. 2004; Howells et al. 2005) that voluntary exercise has a neuroprotective effect, in that exercise reduced the vulnerability of dopamine neurons to the neurotoxic effects of 6-OHDA infusion into the medial forebrain bundle of nerve fibres in the rat brain. The beneficial effects of exercise were seen as an improvement in motor control i.e. earlier initiation of movement in the step test and decreased asymmetry in the use of left and right forelimbs to explore the novel environment in the cylinder test. Adult offspring of prenatally stressed dams also displayed the beneficial effects of exercise but to a lesser extent. Prenatal stress significantly enhanced the toxic effect of 6-OHDA administered in adulthood.

Prenatally stressed rats and non-stressed rats did not differ in terms of body weight or amount of exercise. There was no difference between the mean daily distance covered by non-stressed runners and stressed runners. The daily distance increased steadily from day 1 to day 7 the day of the lesion. Following the decrease in mean revolutions of the wheels after unilateral 6-OHDA infusion, both the non-stressed and the stressed runners took 3 days to reach pre-lesion running distances and ran at similar mean daily distances until day 21 of exercise.

In the step test, exercise reduced the step length of the impaired forelimb towards the normal step length of the non-lesioned forelimb. The mean step length taken by both non-stressed and stressed runners was significantly shorter than the mean step length taken by the non-runners. Prenatal stress significantly increased the right forelimb step length in rats that were allowed to exercise voluntarily, suggesting that prenatal stress is capable of reducing the beneficial effect of exercise. The step test is used to model movement initiation involving weight shifts in animal models of Parkinson’s disease and is sensitive to partial dopamine neuron degeneration (Schallert and Tillerson 2000). The step test assesses the capacity to regain postural stability and center of gravity when rapid weight shifts are imposed (Schallert and Tillerson 2000). Studies have shown that 6-OHDA lesioned animals tend to drag or brace the impaired limb rather than make catch up steps (Schallert and Tillerson 2000; Olsson et al. 1995; Lindner et al. 1995) and injection of direct dopamine agonists permits adequate/normal stepping (Olsson et al. 1995; Lindner et al. 1995). Since dopamine agonists were not used to achieve normal weight shifting movements in the present study, the significantly shorter step length of the non-stressed runners compared to stressed runners may suggest that dopamine degeneration in the nigrostriatal pathway of non-stressed, exercised rats was not as severe as in stressed runners. In the cylinder test which analyses forelimb use for postural support (Schallert and Tillerson 2000; Tillerson et al. 2001) non-stressed runners did not show a preference for use of the unimpaired limb, further supporting the finding that voluntary exercise reduced the toxic effects of 6-OHDA infused into the medial forebrain bundle of non-stressed rats. Schallert and Tillerson (2000) suggested that the preference for the unimpaired limb may be due to the absence of recovery following injury or due to degeneration continuing at a faster rate than ongoing plasticity resulting in a decreased ability to control movement in the impaired limb. In the present study, the mean dopamine neuron destruction in the substantia nigra of non-stressed runners was 51% which according to Schallert and Tillerson (2000) should have resulted in more frequent use of the unimpaired limb than the injured limb in the cylinder test. The present findings are in agreement with previous studies that have shown that exercise abolishes forelimb use asymmetries associated with unilateral infusion of 6-OHDA into the medial forebrain bundle (Tillerson et al. 2001, 2002). The presence of asymmetry in the cylinder test in stressed runners suggests that the beneficial effects of exercise were not as prominent as in the non-stressed runners. High levels of circulating corticosterone have been shown to have an inhibitory effect on the release of neurotrophic factors (Smith 1996; Chao and McEwen 1994; Schaaf et al. 1998). In a previous study we showed that there was no significant difference between basal corticosterone levels of the non-stressed and prenatally stressed rats (Mabandla et al. 2008). Therefore in the present study, the greater dopamine neuron destruction in the substantia nigra of the lesioned hemisphere of prenatally stressed runners is unlikely to be due to high corticosterone levels inhibiting the expression of neurotrophic factors. However in some prenatal stress models, increases in circulating corticosterone are evident after exposure to an acute stressor (Lesage et al. 2002) and therefore corticosterone levels might be increased after stereotaxic surgery or due to isolation in cages with or without running wheels. Other studies have shown that neurotrophic factors such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) are decreased in offspring of rats that were prenatally stressed (Van den Hove et al. 2006). Increased circulating corticosterone levels in the presence of decreased BDNF levels might result in greater destruction of dopamine neurons in the substantia nigra, as observed in the present study. Exercise has been shown to increase GDNF levels in rats treated with 6-OHDA (Cohen et al. 2003). In the present study, exercise reduced the percentage loss of dopamine neurons in both stressed and non-stressed rats. These findings suggest that exercise provides neuroprotection in both stressed and non-stressed rats and that prenatally stressed rats are more susceptible to brain injury in adulthood than non-stressed rats.

When assessing the number of tyrosine hydroxylase positive cells in the substantia nigra of the lesioned hemispheres, the non-stressed runners, stressed runners and non-stressed non-runners fall within the range of non-severely lesioned rats (41–79% dopamine neuron destruction) whereas the stressed non-runners fell within the severely lesioned rat category (80–99% dopamine neuron destruction) as defined by Schallert and Tillerson (2000).

Consistent with the suggestion that prenatal stress exacerbates the toxic effect of 6-OHDA, the actual number of completely stained tyrosine hydroxylase-positive cells observed in 60 μm sections of the left (lesioned) substantia nigra pars compacta of prenatally stressed non-runners was significantly lower than that of non-stressed non-runners. Voluntary exercise significantly increased dopamine cell survival in prenatally stressed runners, consistent with its beneficial effects. However, exercise also decreased the dopamine cell count in the right (non-lesioned) substantia nigra pars compacta of non-stressed runners suggesting that the reduction in asymmetry of behaviour may have been partly due to a compensatory decrease in tyrosine hydroxylase expression in the non-lesioned hemisphere. Interestingly, neural changes that resulted from prenatal stress appeared to prevent this compensatory adaptation from occurring. The dopamine cell count in the non-lesioned substantia nigra pars compacta of prenatally stressed runners was not significantly different from non-runners.

Prenatally stressed rats displayed anxiety-like behaviour in the open field (McFadyen-Leussis et al. 2004), they travelled a shorter distance and entered the inner zone of the open field less frequently than non-stressed rats which is in agreement with results obtained with the mild stress model reported by Mabandla et al. (2008). Exercise reduced the anxiety-like behaviour associated with open field exploration, exercised rats displayed increased locomotor activity and ventured into the more open inner zone of the open field more frequently than non-exercised rats. It must be noted, however, that most of the running done by the rats in the open field was along the wall of the open field. Therefore the absence of anxiety-like behaviour in the stressed runners might be due to adaptation to the exercise regimen rather than to the inhibition of the anxiety-like behaviour associated with prenatal stress. The severity of the lesion in the stressed non-runners (>80%) could mean that the rats were less inclined to explore the open field due to locomotor activity deficits rather than anxiety-like behaviour. It must be noted that the rats were tested in their dark cycle as Sprague Dawley rats tend to be inactive during the light cycle (Schallert 2006).

The present results confirm and extend a previous study where female Sprague Dawley rats were subjected to postnatal maternal separation which exacerbated the toxic effect of 6-OHDA unilaterally infused into the left striatum at a younger age of 35 days (Pienaar et al. 2008). The effect of 6-OHDA on behavioural asymmetry and dopamine neuron survival was not as marked as in the female rat study. This difference may be due to sex differences in vulnerability of dopamine neurons to 6-OHDA (Pienaar et al. 2007). Compared to males, female rats appeared to be relatively protected from the neurotoxic effects of 6-OHDA possibly due to circulating hormones affecting neurotrophic factors in the brain, specifically nerve growth factor levels were found to be higher in 6-OHDA treated females than males.

Conclusion

By using small doses of 6-OHDA, we were able to create dopamine neuron destruction more representative of early Parkinson’s disease (Truong et al. 2006). This made it possible to unmask the beneficial effects of exercise in non-stressed rats. In a prenatal stress rat model, injecting a small dose of 6-OHDA resulted in a lesion more consistent with larger doses of 6-OHDA (Truong et al. 2006) with dopamine neuron destruction equivalent to the destruction seen when a higher dose of 6-OHDA was used (Mabandla et al. 2004; Howells et al. 2005), thus implying that the prenatally stressed rats are more vulnerable to the toxic effects of 6-OHDA than non-stressed rats however with voluntary exercise, substantia nigra dopamine destruction and the asymmetrical behaviour associated with a Parkinsonian rat model can be reversed or cancelled. Therefore trauma to the substantia nigra might increase the susceptibility to developing Parkinson’s disease in people or animals that were exposed to prenatal stress in utero.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the University of Cape Town and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Fogarty International Center grants R21DA018087 & R01TW008040 to Michael J. Zigmond, principal investigator. The authors wish to express their thanks to Ms Shula Johnson for technical support and to Dr Michael Zigmond, Dr Amanda Smith and Ms Sandy Castro for their invaluable advice and training provided for Dr Musa Mabandla. This work forms part of the PhD thesis of Dr Musa Mabandla.

References

- Chao HM, McEwen BS. Glucocorticoids and the expression of mRNA’s for neurotrophins, their receptors and GAP-43 in the rat hippocampus. Molec Brain Res. 1994;26:271–276. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)90099-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen Ad, Tillerson JL, Smith AD, Schallert T, Zigmond MJ. Neuroprotective effects of prior limb use in 6-hydroxydopamine-treated rats: possible role of GDNF. J Neurochem. 2003;85:299–305. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colorado RA, Shumake J, Conejo NM, Gonzalez-Pardo H, Gonzalez-Lima F. Effects of maternal separation, early handling, and standard facility rearing, on orienting and impulsive behavior of adolescent rats. Behav Proc. 2006;71:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnaudéry M, Dutriez I, Viltart O, Morley-Fletcher S, Maccari S. Stress during gestation induces lasting effects on emotional reactivity of the dam rat. Behav Brain Res. 2004;153:211–216. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emborg E. Evaluation of animal models of Parkinson’s disease for neuroprotective stratergies. J Neurosci Meth. 2004;131:121–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan J, Krishnamurthi R, Waldvogel HJ, Faull RLM, Clark R, Gluckman P. N-terminal tripeptide of IGF-1 (GPE) prevents the loss of TH positive neurons after 6-OHDA induced nigral lesion in rats. Brain Res. 2000;859:286–292. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)01988-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson JM, Watson SH, Halliday GM, Heinemann T, Gerlach M. Relationships between various behavioural abnormalities and nigrostriatal dopamine depletion in the unilateral 6-OHDA-lesioned rat. Behav Brain Res. 2003;139:105–113. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howells FA, Russell VA, Mabandla MV, Kellaway LA. Stress reduces the neuroprotective effect of exercise in a rat model for Parkinson’s disease. Behav Brain Res. 2005;165:210–220. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khashan AS, Abel KM, McNamee R, Pedersen MG, Webb RT, Baker PN, Kenny LC, Mortensen PB. Higher risk of offspring schizophrenia following antenatal maternal exposure to severe adverse life events. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:146–152. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinney DK. Prenatal stress and risk for schizophrenia. Int J Ment Health. 2001;29:62–72. [Google Scholar]

- Kinney DK, Munir KM, Crowley DJ, Miller AM. Prenatal stress and risk for autism. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32:1519–1532. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesage J, Dufourny L, Laborie C, Bernet F, Blondeau B, Avril I, Bréant B, Dupouy JP. Perinatal malnutrition programs sympathoadrenal and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis responsiveness to restraint stress in adult male rats. J Neuroendocrinol. 2002;14:135–43. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1331.2001.00753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindner MD, Winn SR, Baetge EE, Hammang JP, Gentile FT, Doherty E, McDermott PE, Frydel B, Ullman MD, Schallert T, Emerich DF. Implantation of encapsulated catecholamine and GDNF-producing cells in rats with unilateral dopamine depletions and Parkinsonian symptoms. Exp Neurol. 1995;132:62–76. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(95)90059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabandla M, Kellaway L, St Clair Gibson A, Russell VA. Voluntary Running Provides Neuroprotection in Rats after 6-Hydroxydopamine Injection into the Medial Forebrain Bundle. Metab Brain Dis. 2004;19:43–50. doi: 10.1023/b:mebr.0000027416.13070.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabandla MV, Dobson B, Johnson S, Kellaway LA, Daniels WM, Russell VA. Development of a mild prenatal stress rat model to study long term effects on neural function and survival. Metab Brain Dis. 2008;23:31–42. doi: 10.1007/s11011-007-9049-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcondes FK, Bianchi FJ, Tanno AP. Determination of the estrous cycle phases of rats: some helpful considerations. Braz J Biol. 2002;62(4A):609–614. doi: 10.1590/s1519-69842002000400008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFadyen-Leussis MP, Lewis SP, Bond TLY, Carrey N, Brown RE. Prenatal exposure to methylphenidate hydrochloride decreases anxiety and increases exploration in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004;77:491–500. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2003.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor TG, Ben-Shlomo Y, Heron J, Golding J, Adams D, Glover V. Prenatal anxiety predicts individual differences in cortisol in pre-adolescent children. Biol Psychiat. 2005;58:211–217. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson M, Nikkah G, Bentlage C, Bjorklund A. Forelimb akinesia in the rat Parkinsons model: differential effects of dopamine agonists and nigra transplants as assessed by a new stepping test. J Neurosci. 1995;15:3863–3875. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-03863.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. 2. Academic; New York: 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pienaar IS, Schallert T, Russell VA, Kellaway LA, Carr JA, Daniels WMU. Early pubertal female rats are more resistant than males to 6-hydroxydopamine neurotoxicity and behavioural deficits: a possible role for trophic factors. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2007;25:513–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pienaar IS, Kellaway LA, Russell VA, Smith AD, Stein D, Zigmond MJ, Daniels WMU. Maternal separation exaggerates the toxic effects of 6-hydroxydopamine in rats: implications for neurodegenerative disorders. Stress. 2008;11(6):448–456. doi: 10.1080/10253890801890721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaaf MJM, de Jong J, de Kloet ER, Vreugdenhil E. Downregulation of BDNF mRNA and protein in the rat hippocampus by corticosterone. Brain Res. 1998;813:112–120. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)01010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schallert T. Behavioral tests for preclinical intervention assessment. NeuroRx. 2006;3:497–504. doi: 10.1016/j.nurx.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schallert T, Tillerson JL. Intervention strategies for degeneration of dopamine neurons in Parkinsonism: optimizing behavioral assessment of outcome. In: Emerich DF, Dean RL, Sandberg PR, editors. Central nervous system diseases: innovative models of CNS diseases from molecule to therapy. Humana; Totowa: 2000. pp. 131–151. [Google Scholar]

- Schallert T, Woodlee MT. Motor systems: orienting and placing. In: Whishaw I, Kolb B, editors. The behavior of the laboratory rat: a handbook with tests. Oxford University Press; New York: 2005. pp. 129–140. [Google Scholar]

- Smith MA. Hippocampal vulnerability to stress and aging: possible role of neurotrophic factors. Behav Brain Res. 1996;78:25–36. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(95)00220-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillerson JL, Cohen AD, Philhower J, Miller GW, Zigmond MJ, Schallert T. Forced limb-use effects on the behavioural and neurochemical effects of 6-Hydroxydopamine. J Neurosci. 2001;21:4427–4435. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-12-04427.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillerson JL, Cohen AD, Caudle WM, Zigmond MJ, Schallert T, Miller GW. Forced nonuse in unilateral Parkinsonian rats exacerbates injury. J Neurosci. 2002;22(15):6790–6799. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06790.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truong L, Allbutt H, Kassiou M, Henderson JM. Developing a preclinical model for Parkinson’s disease: a study of behaviour in rats with graded 6-OHDA lesion. Behav Brain Res. 2006;169(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungerstedt U. Postsynaptic supersensitivity after 6-hydroxydopamine induced degeneration of the nigro-striatal dopamine system. Acta Physiol Scand Suppl. 1971;367:69–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-201x.1971.tb11000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Hove DLA, Steinbusch HWV, Scheepens A, Van de Berg WDJ, Kooiman LAM, Boosten BJG, Prickaerts J, Blanco CE. Prenatal stress and neonatal brain development. Neurosci. 2006;137(1):145–155. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.08.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstock M. The long-term behavioural consequences of prenatal stress. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32:1073–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstock M. Alterations induced by gestational stress in brain morphology and behaviour of the offspring. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;65:427–451. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(01)00018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]