Abstract

Guanylyl cyclases (GCs), a ubiquitous family of enzymes that metabolize GTP to cyclic GMP (cGMP), are traditionally divided into membrane-bound forms (GC-A-G) that are activated by peptides and cytosolic forms that are activated by nitric oxide (NO) and carbon monoxide. However, recent data has shown that NO activated GC’s (NOGC) also may be associated with membranes. In the present study, interactions of guanylyl cyclase A (GC-A), a caveolae-associated, membrane-bound, homodimer activated by atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), with NOGC, a heme-containing heterodimer (α/β) β1 isoform of the β subunit of NOGC (NOGCβ1) was specifically focused. NOGCβ1 co-localized with GC-A and caveolin on the membrane in human kidney (HK-2) cells. Interaction of GC-A with NOGCβ1 was found using immunoprecipitations. In a second set of experiments, the possibility that NOGCβ1 regulates signaling by GC-A in HK-2 cells was explored. ANP-stimulated membrane guanylyl cyclase activity (0.05 ± 0.006 pmol/mg protein/5 min; P < 0.01) and intra cellular GMP (18.1 ± 3.4 vs. 1.2 ± 0.5 pmol/mg protein; P < 0.01) were reduced in cells in which NOGCβ1 abundance was reduced using specific siRNA to NOGCβ1. On the other hand, ANP-stimulated cGMP formation was increased in cells transiently transfected with NOGCβ1 (530.2 ± 141.4 vs. 26.1 ± 13.6 pmol/mg protein; P < 0.01). siRNA to NOGCβ1 attenuated inhibition of basolateral Na/K ATPase activity by ANP (192 ± 22 vs. 92 ± 9 nmol phosphate/mg protein/min; P < 0.05). In summary, the results show that NOGCβ1 and GC-A interact and that NOGCβ1 regulates ANP signaling in HK-2 cells. The results raise the novel possibility of crosstalk between NOGC and GC-A signaling pathways in membrane caveolae.

Keywords: GC-A, Guanylyl cyclases, cGMP, HK-2 cells, Nitric oxide, Atrial natriuretic peptide

Introduction

Guanylyl cyclases (GCs) are a family of enzymes that metabolize GTP to cyclic GMP (cGMP). These have conventionally been divided into membrane-bound forms that are activated by peptides, and cytosolic forms that are activated by nitric oxide (NO) and carbon monoxide [1, 2].

Peptide-activated GCs are a family of seven membrane-bound proteins (GC-A to GC-G) [3]. Based on their ligand specificities, membrane-bound GCs have been classified into natriuretic peptide GC receptors (GC-A and GC-B), intestinal peptide-binding receptors (GC-C), and orphan receptors, (GCD-GCG) [4]. GC-A and GC-B, principal receptors for atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), are generally accepted to be homodimers consisting of subunit of approx 115 kDa with highly conserved regions, including an extra cellular ligand binding domain important in ANP binding; a single transmembrane domain; a cytoplasmic juxta-membrane domain; a regulatory domain consisting of kinase homology domain (KHD); a hinge region required for dimerization; and a C-terminal catalytic domain which catalyzes the synthesis of cGMP [5–7]. Although GC-A exists as monomers and oligomers, it is generally accepted that only the dimer is activated by ANP [8–10]. GC-B was first identified by E. Page and demonstrated to be caveolin-associated and expressed in caveolae [11].

NOGCs are a ubiquitous family of heme-containing heterodimers (α and β subunits of approx 80 and 72 kDa, respectively) [12, 13]. Two isoforms of each subunit, i.e., (α1, α2, β1, and β2) have been identified with the α1/β1 heterodimer considered the universal form. Both α and β subunits contain an amino-terminal domain important in heme binding; a central dimerization domain required for subunit association; and a carboxyl terminal catalytic domain. Although originally isolated from cytosol, NOGC has more recently been detected in cells membranes [14, 15] and a functional membrane caveolae-associated NOGC and PKG signaling complex identified in both rat aortic and corpus cavernosum endothelial cells [16, 17].

Recently, complex multi-protein caveolae-associated interactive “signaling complexes” have been determined. This signaling complex includes, eNOS [18], GC-A [11], cGK [19], caveolin-1 [20], heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) [21], eNOS interacting protein (NOSIP) [22], and dynamin-2 [23]. The localization of both NOGCbeta1 and ANP-stimulated guanylyl cyclase in membrane caveolae raises the possibility that NOGC influences GC-A signaling. As a first step toward investigating this possibility, we determined whether the β1 subunit of NOGC (NOGCβ1) was capable of interacting with GC-A and whether an effect of NOGCβ1 on GC-A activity could be detected in HK-2 cells.

Materials and methods

Isobutyl methyl xanthine (IBMX) and ANP were purchased from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO). N (G)-Nitro-L-Arginine Methyl Ester (L-NAME) and H-3048 were obtained from Calbiochem Gibbstown, NJ) and Bachem Inc (Torrance, CA), respectively. siRNA duplex oligonucleotides r (GAGGC-ACAGUUA GAU GAAG) d (TT), r (CUUC AUCUA ACUG UGCC UC d (TT) directed against amino-terminal portion of NOGCβ1 were synthesized by Qiagen (Valencia, CA). NOGCβ1 and GC-A polyclonal antibodies were purchased from FabGennix Inc (Frisco, TX). Rabbit polyclonal Ab for caveolin, and rabbit anti-6× HIS polyclonal primary antibodies were from Upstate and Abcam, respectively. Cultured Human kidney-2 (HK-2) cells, (ATCC) were used at early passages and cultured in DMEM F12 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum under 5% CO2.

Transfections

Plasmids coding for full-length cDNAs of rat NOGCβ1 and GC-A were kindly provided by Dr. David Garbers (Dallas, TX). Expression plasmid for full length NOGCβ1 with yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) at the C-terminal end (pIRES-NOGCβ1-EYFP) for use in immunofluorescence experiments was generated by cloning NOGCβ1 into pIRES-EYFP (Clontech Inc) at EcoRV and Nco1 sites. In order to generate expression plasmids for use in transient transfection assays, cDNAs for NOGCβ1 and GC-A were PCR amplified by using gene specific primers and the PCR products were cloned in Hind III and Bam HI sites of cDNA 3.1 vector. Transient transfection of HK-2 cells was performed using lipofectamine 2,000 reagent (Invitrogen/life technologies). Briefly, cells were plated in a six well plate at the density of 1.8 × 106 cells per plate and transfected 24 h after plating using lipofectamine 2000 as per manufacturer’s instructions. Transfections with siRNA duplexes were carried out with trans messenger transfect reagent (Qiagen).

Immunoprecipitation (IP)

HK-2 cells were harvested from 10 cm2 tissue culture dishes and cell pellets lysed in RIPA buffer (25 mM Tris–HCl—pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 1% non-idet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS). Cell extracts were mixed with GC-A antibody (1 mg/ml) (FabGennix) and incubated at 4°C with continuous shaking overnight. Protein A/G agarose beads (20 μl) were added and incubated for 2 h with continuous shaking. The beads were washed with 1% Triton-X-100 in PBS, 0.5% Triton-X-100 in PBS, and 0.05% Triton-X-100 in PBS, respectively, resuspended in SDS sample loading buffer, and subjected to SDS PAGE followed by a western blot with NOGCβ1 antibodies.

Immunofluorescence

HK-2 cells were cultured in 2-well chamber slides at a density of ~10,000 cells/cm2 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium with 10% Fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin solution. Forty-eight hours after transfection cells were fixed in 3% Para formaldehyde and permeabilized with 1% Triton-X-100 in phosphate-buffered saline for 10 min. Fixed slides were incubated with a primary antibody mixture containing anti 6× HIS polyclonal primary antibody for 1 h (as GCA expression plasmid has the 6-His tag fused to its carboxyl terminus) followed by incubation in Alexa fluor 405-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody to detect GC-A signal. Expression of NOGCβ1 was detected by yellow fluorescence. To appreciate the merger signals, they were assigned pseudo colors red for GC-A staining and green for NOGCβ1. Confocal images were obtained using Zeiss laser-scanning confocal microscope LSM 510 META in multi-tracking mode to prevent interference of the dyes.

cGMP and guanylyl cyclase activity assays

Intracellular cGMP was measured in cultured cells pre-treated with IBMX (1 mM × 1 h), a broad spectrum phosphodiesterase inhibitor that prevents degradation of cGMP by PDEs. Cells were lysed with three cycles of freezing in liquid nitrogen for 5 min and thawing at 37°C for 5 min. cGMP was measured using a commercially available enzyme immuno assay (EIA) Direct cGMP kit (Assay Design Inc (Ann Arbor, MI)). Intracellular cGMP was normalized to total protein determined by Bradford.

Guanylyl cyclase activity was measured in whole cell membranes as previously described [24]. Membranes were isolated as follows. Cells from numbers 5–6 150-mm2 dishes were washed twice with 5 ml chilled phosphate-free buffer (2.36 M NaCl, 0.54 M NaHCO3, 0.4 M KCl, and 0.12 M MgCl2scraped in phosphate-free buffer) and centrifuged at 3,000g for 8–10 min. The cells were then placed on ice and lysed by dounce homogenization in 2 ml of lysis buffer (1 mM NaHCO3, 2 mM CaCl2, and 5 mM MgCl2). Cellular lysates were centrifuged at 3,000g for 1–2 min to remove intact cells, debris, and nuclei. The resulting supernatant was suspended in an equal volume of 1 M NaI, and the mixture was centrifuged at 48,000g for 25 min. The pellet (membrane fraction) was washed one to two times and suspended in 10 mM Tris and 1 mM EDTA (pH 7.4). Protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford assay and adjusted to 1 mg/ml. The membranes were stored at −70°C until further use. Guanylyl cyclase activity was measured in the presence of phosphatase inhibitors (50 mM sodium fluoride, 1 mM sodium ortho-vanadate, and 1 mM sodium pyrophosphate), protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma), and IBMX. cGMP was measured with the use of enzyme immuno assay (EIA) Direct cGMP kit (Assay Design Inc (Ann Arbor, MI)).

Na+/K+ ATPase activity

Na+/K+ ATPase activity of membrane extractions was measured as inorganic phosphate released in the presence or absence of ouabain as previously described [25]. Na+/K+ ATPase activity was calculated as the difference between total ATPase activity and the ouabain-insensitive ATPase activity and expressed as nmol phosphate produced per mg protein per min.

Statistics

Values are expressed as the mean ± SD. Differences among groups are determined by ANOVA two-factor for repeated measurements. Results were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Endogenous NOGCβ1 increases GC-A activity

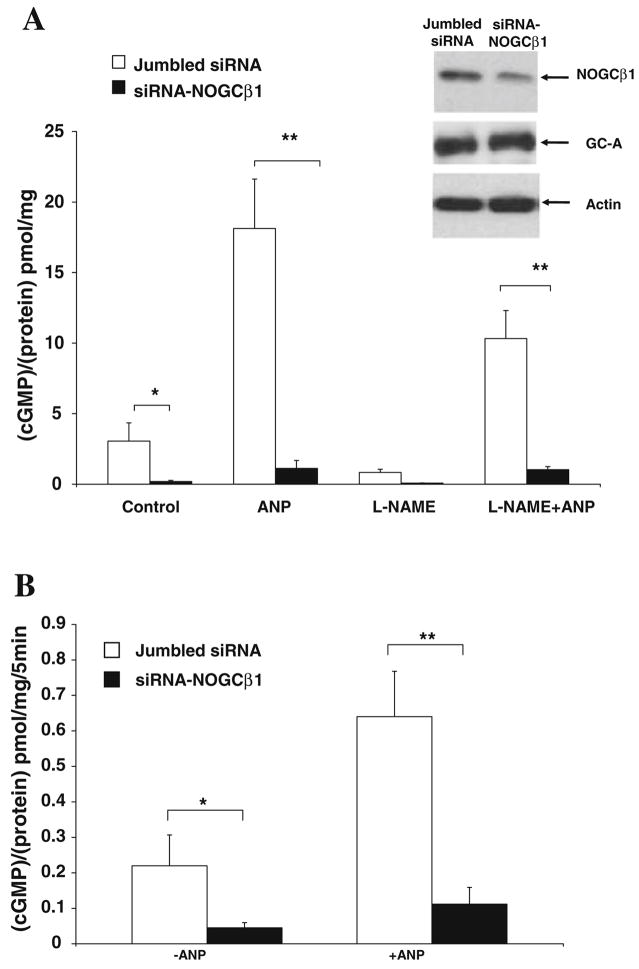

In order to determine whether NOGCβ1 effects GC-A activity, ANP-stimulated cGMP formation was evaluated in HK-2 cells in which endogenous NOGCβ1 protein expression was suppressed with specific siRNA using transient transfections (Fig. 1, panel A). ANP-stimulated cGMP formation was decreased in which endogenous NOGCβ1 expression was reduced with specific siRNA. GC-A protein expression was the same in control and siRNA treated cells (Fig. 1, panel A-inset).

Fig. 1.

Panel A: siRNA against NOGCβ1 decreases basal and ANP-stimulated intracellular cGMP levels in HK-2.HK-2 cells (jumbled siRNA-white bars) and HK-2 cells transfected with siRNA directed against N-terminal part of NOGCβ1 (black bars) were treated with ANP for 45 min (ANP), L-NAME for 16 h (L-NAME) and both L-NAME and ANP and cGMP assay was carried out as described in “Materials and methods” section. Inset: Representative immunoblot with actin, GC-A, and NOGCβ1 specific polyclonal Abs showing abundance of GC-A, and NOGCβ1 levels (arrows with GC-A and NOGCβ1) in cells transiently transfected with jumbled siRNA or siRNA to NOGCβ1. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01; n = 4. Panel B: siRNA against NOGCβ1 decreases ANP-stimulated membrane guanylyl cyclase activity. HK-2 cells were transfected with siRNA duplex oligonucleotides and incubated in the presence or absence of 10−7 M ANP for 45 min. Membrane fractions were collected and membrane guanylyl cyclase activity was determined as described in “Materials and methods” section. Experiments are repeated twice. * P < 0.05; n = 4

To more closely link the membrane-association of NOGCβ1 to GC-A activity, guanylyl cyclase activity was measured in membranes prepared from HK-2 cells transfected with siRNA-NOGCβ1 (Fig. 1, Panel B). ANP-stimulated guanylyl cyclase activity was significantly less than in membranes from HK-2 cells transfected with a control—scrambled siRNA.

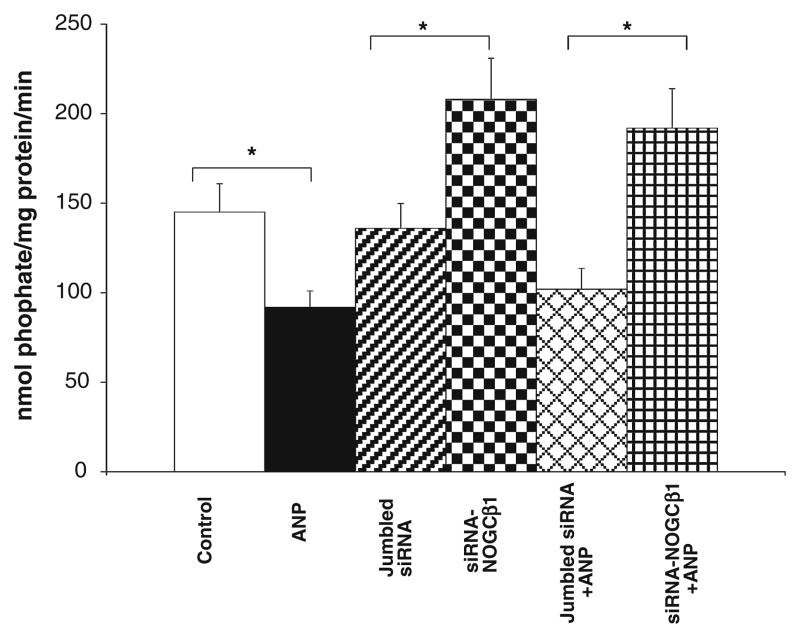

Endogenous NOGCβ1 augments ANP-mediated inhibition of basolateral Na/K ATPase in HK-2 cells

ANP, via cGMP signaling, and PKG phosphorylation inhibits basolateral Na/K ATPase in renal epithelial cells [26, 27]. So whether endogenous NOGCβ1 effects inhibition of Na+/K+ ATPase by ANP in HK-2 cells was investigated. In these experiments, HK-2 cells were pre-treated with L-NAME (1 mM × 16 h) to inhibit endogenous NO-synthase activity. ANP reduced Na+/K+ ATPase activity in control cells by approx 40% (Fig. 2). Na+/K+ ATPase activity was increased by 40% and ANP-mediated inhibition of Na+/K+ ATPase activity was reduced in cells treated with siRNA-NOGCβ1, suggesting that NOGCβ1 enhances inhibition of endogenous Na+/K+ ATPase activity by ANP in HK2 cells and that this effect is independent of NO signaling.

Fig. 2.

siRNA to NOGCβ1 blocks ANP-mediated inhibition of endogenous Na+/K/ATPase activity in HK-2 cells pre-treated with L-NAME. HK-2 cells (control) and HK-2 cells were pretreated with L-NAME (1 mM × 16 h) to inhibit endogenous NO formation. Cells were transfected with jumbled siRNA (2 μg) or siRNA to NOGCβ1 (2 μg) and treated with 10−7 M ANP (45 min) as indicated. * P < 0.05; n = 3

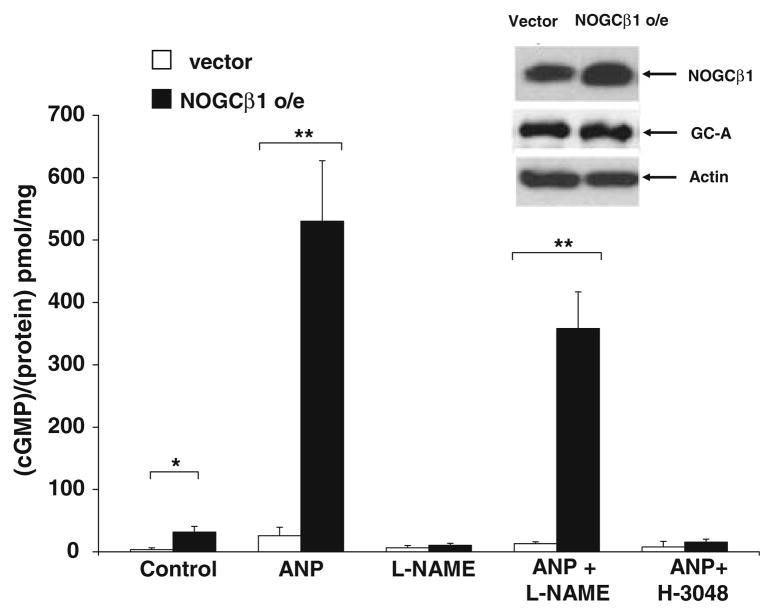

Over-expression of NOGCβ1 increases GC-A activity

In experiments complementary to those in which endogenous expression of NOGCβ1 was blocked, NOGCβ1 was over-expressed in transiently transfected HK-2 cells (Fig. 3). Basal and ANP-stimulated cGMP formation were increased 5–10 fold (P < 0.05). There was a trend toward less stimulation in cells pretreated with L-NAME (1 mM × 16 h). The effect of ANP on cGMP was blocked by the GC-A inhibitor H-3048 (10−6 M × 1 h). GC-A protein expression was the same in vector and NOGCβ1 transfected cells (Fig. 3, inset) indicating that NOGCβ1 does not regulate GC-A expression.

Fig. 3.

NOGC β1 over expression increases basal and ANP-stimulated cGMP formation in HK-2 cells. HK-2 cells were transiently transfected with pcDNA3.1 vector (white bars) or NOGCβ1 expression plasmid (NOGCβ1, black bars) and incubated with IBMX (1 mM) and ANP (10−7 M × 45 min), L-NAME (1 mM × 16 h), ANP and L-NAME, or ANP and H-3048, an inhibitor of ANP (10−6 M × 45 min). At the end of treatment periods, the cells were harvested and cell lysates were subjected to cGMP assay as described in “Materials and methods” section; n = 4. Inset: Western analysis with Actin, GC-A, and NOGCβ1 specific polyclonal Abs showing GC-A abundance (arrow with GC-A), and NOGCβ1 levels (arrow with NOGCβ1) in cells transfected with vector (pcDNA3.1) or NOGCβ1 expression plasmid (NOGCβ1 o/e). n = 4; * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01

NOGCβ1 can interact with GC-A on the surface membrane of HK-2 Cells

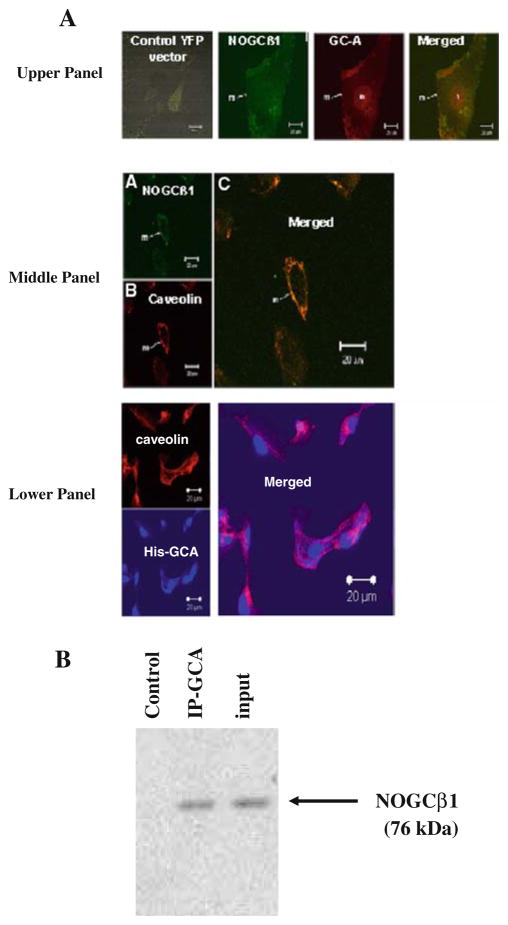

The distribution of YFP-tagged NOGCβ1 was examined in HK-2 cells transiently transfected with pIRES-NOGCβ1-YFP plasmid and cellular localization determined by YFP yellow fluorescence (Fig. 4a, upper panel NOGCβ1). In these cells approximately 50–60% of the NOGCβ1 signal was detected in the cell membranes with some cytosolic and nuclear staining. Control vector, pIRES-YFP showed diffused staining throughout the cell (Fig. 4a upper panel, control YFP vector). In order to determine the distribution of NOGCβ1 relative to GC-A, cells were co-transfected with His-tagged GC-A (His-GC-A) and immunofluorescence performed with a polyclonal Ab against the 6-His tag. His-GC-A (red) was most concentrated on the cell membrane and in the nucleus (Fig. 4a, upper panel, GC-A). When the confocal images were overlayed, merger (yellow) of His-GC-A (red) and YFP-NOGCβ1 (green) signals was observed (Fig. 4a, upper panel, merged). In overlays of confocal images with caveolin labeled with rhodamine, there was also merger of signals from YFP-NOGCβ1 and His-GC-A (Fig. 4a, middle and lower panels). Together these results suggest that NOGCβ1 is expressed in membrane caveolae with GC-A. To examine whether NOGCβ1 interacts with GC-A, immunoprecipitations were performed (Fig. 4b). Whole cell extracts were prepared from HK-2 cells and immunoprecipitated with affinity purified rabbit polyclonal anti-GC-A antibody directed against the N terminus of GC-A (FabGennix international Inc) (see “Materials and methods” section). The resulting immunoprecipitates were assayed with antibody against NOGCβ1. NOGCβ1 was immunoprecipitated in extracts from HK-2 cells, but not with normal goat IgG as a negative control.

Fig. 4.

a YFP-tagged NOGCβ1 and GC-A localize to membrane in HK-2 cells. NOGCβ1: Confocal images of HK-2 cells transiently co-transfected with YFP-tagged NOGCβ1 and His-tagged GC-A (see “Materials and methods” section). Upper panels: control pIRES-YFP vector (yellow fluorescence): NOGCβ1: pIRES-NOGCβ1-YFP transfected cells (Green fluorescence); GC-A: Immunostaining with polyclonal Ab to His tag GC-A. (red fluorescence). Merged images of NOGCβ1 and GC-A. m membrane, n nucleus. Middle panel: NOGCβ1: HK-2 cells transfected with YFP-tagged NOGCβ1[YFP fluorescence (green)]. Caveolin: Immunostaining with polyclonal Ab to caveolin (red fluorescence); merged images of NOGCβ1 and caveolin. Lower panel: Caveolin: Immunostaining with polyclonal Ab to caveolin (red fluorescence); HIS GC-A: Immunostaining with polyclonal Ab to His tag GC-A. (blue fluorescence); merged images of HIS GC-A and caveolin. b NOGCβ1 interacts with GC-A. Human Kidney-2 (HK-2) cells were harvested and cell pellets lysed in RIPA buffer. Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with control IgG (control) anti GC-A Ab (IP-GCA) and NOGCβ1 identified on Western analysis using a polyclonal anti NOGCβ1 Ab as described in “Materials and methods” section. Total lysate “Input” (Color figure online)

Discussion

The present findings both challenges the traditional paradigm that NO and natriuretic peptide guanylate cyclases function independently of each other and raise the spector of cross-talk between the two pathways. The present results show that the NOGCβ1 subunit of NOGC is capable of associating with and regulating GC-A activity/signaling, thereby revealing a novel potential for cross-talk between NO- and ANP-stimulated guanylyl cyclases.

Our findings that (1) reducing expression of endogenous NOGCβ1 with siRNA and recombinant NOGCβ1 decrease and increase, respectively, ANP-stimulated cGMP formation in HK-2 cells; and (2) membrane guanylyl cyclase activity is reduced in cells treated with siRNA to NOGCβ1 suggests that NOGCβ1 regulates GC-A activity within caveolae. However, the mechanism by which NOGCβ1 affects GC-A activity remains to be fully elucidated. It does not appear to be dependent upon NOGC activity since L-NAME, an inhibitor of NOS, did not abolish it. It is possible that other cyclase subunits, in particular of NOGCα associate with peptide-activated GCs, and that the association between NOGCβ1 and GC-A proteins involves other proteins in the caveolae-associated signaling complex. Our results suggest a cross talk between ANP/GC-A and NOGCβ1. Furthermore, ANP has been reported to stimulate the nitric oxide signaling pathway via activation of nitric oxide synthase in rat kidney [28], primary cultures of human proximal tubular cells [29], and rabbit ventricular myocytes [30]. Together, these results suggest a novel cross-talk between these two guanylyl cyclase signaling pathways.

Basolateral Na/K ATPase is a principal regulator of Na reabsorption in the proximal tubule and of natriuresis. cGMP, through cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG) reduces basolateral Na/K ATPase activity in renal tubule cells [31, 32]. Changes in basolateral Na/K ATPase activity in HK-2 cells are consistent with changes in cellular cGMP with siRNA to NOGCβ1 blocking ANP-mediated inhibition of Na/K ATPase activity. The finding that inhibition of endogenous basolateral caveolae-associated Na/K ATPase activity by ANP in HK-2 cells in which endogenous NOGCβ1 expression is reduced by specific siRNA (Fig. 2) provides both collaborative support and suggests physiological relevance of NOGCβ1 in ANP signaling [32, 33]. Additionally, it raises the possibility that in previous studies of ANP and GC-A signaling, changes in NOGCβ1 could have played a role.

The present confocal image results showed that GC-A and NOGCβ1 are concentrated on the cell surface membranes of HK-2 cells and co-localize with caveolin (Fig. 4a). ANP and GC-B have previously been reported to be expressed in caveolae in cardiac myocytes [11]. NOGCβ1 has recently been detected in membranes from neuronal and endothelial cells [14, 15].

We showed that endogenous GC-A associates with recombinant NOGCβ1 protein in HK-2 cells (Fig. 4b). That GC-A immunoprecipitates NOGCβ1 suggests that NOGCβ1 is actually associated, via direct and indirect protein–protein interactions, with GC-A in membrane of HK-2 cells. Even though both GC-A and NOGCβ1 have few similar regions thought to be important for dimerization [8, 19], we speculate that the interaction is most likely indirect, involving other caveolae-associated proteins, e.g., caveolin. While we are proposing that caveolae-associated GC-A targets NOGCβ1 to the membrane, there is evidence for other proteins associated with caveolae. Both B-type natriuretic receptor guanylate cyclase (GC-B) and NOGCβ1 localize in caveolae in cardiac myocytes [11] and in rat aortic and corpus cavernosus endothelial cells [16, 17], respectively. An endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), NOGC and cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG) signaling “complex” in endothelial cell caveolae has been demonstrated [16, 17].

That NOGCβ1 immunoprecipitates with GC-A and co-localizes with caveolin indicates that it too is in caveolae in HK-2 cells. Caveolae association of NOGC has recently been both reported in cavernosal and aortic endothelial cells and shown to be critical to NO-induced smooth muscle relaxation and erection [16, 17]. Whether NOGCβ1 association with caveolae is regulated in HK-2 cells was not addressed in the present study and remains to be determined.

Acknowledgments

National Institute of Health H R21DK 065628-02 (to RSD); American Heart Association Grant-in-Aid (to RSD); Tobacco Research Institute (to RSD); National Institute of Health K01 DK071641-03 (to KUK).

References

- 1.Lucas KA, Pitari GM, Kazerounian S, Ruiz-Stewart I, Park J, Schulz S, Chepenik KP, Waldman SA. Guanylyl cyclases and signaling by cyclic GMP. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52:375–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foster DC, Wedel BJ, Robinson SW, Garbers DL. Mechanisms of regulation and functions of guanylyl cyclases. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;135:1–39. doi: 10.1007/BFb0033668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuhn M. Structure, regulation, and function of mammalian membrane guanylyl cyclase receptors, with a focus on guanylyl cyclase-A. Circ Res. 2003;93:700–709. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000094745.28948.4D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruskoaho H. Atrial natriuretic peptide: synthesis, release, and metabolism. Pharmacol Rev. 1992;44:479–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson EM, Chinkers M. Identification of sequences mediating guanylyl cyclase dimerization. Biochemistry. 1995;34:4696–4701. doi: 10.1021/bi00014a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duda T, Goraczniak RM, Sharma RK. Glutamic acid-332 residue of the type C natriuretic peptide receptor guanylate cyclase is important for signaling. Biochemistry. 1994;33:7430–7433. doi: 10.1021/bi00189a050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson DK, Garbers DL. Dominant negative mutations of the guanylyl cyclase-A receptor. Extracellular domain deletion and catalytic domain point mutations. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:425–430. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chinkers M, Wilson EM. Ligand-independent oligomerization of natriuretic peptide receptors. Identification of heteromeric receptors and a dominant negative mutant. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:18589–18597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lowe DG. Human natriuretic peptide receptor-A guanylyl cyclase is self-associated prior to hormone binding. Biochemistry. 1992;31:10421–10425. doi: 10.1021/bi00158a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Lean A, McNicoll N, Labrecque J. Natriuretic peptide receptor A activation stabilizes a membrane-distal dimer interface. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:11159–11166. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212862200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doyle DD, Ambler SK, Upshaw-Earley J, Bastawrous A, Goings GE, Page E. Type B atrial natriuretic peptide receptor in cardiac myocyte caveolae. Circ Res. 1997;81:86–91. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koglin M, Behrends S. Native human nitric oxide sensitive guanylyl cyclase: purification and characterization. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;67:1579–1585. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foerster J, Harteneck C, Malkewitz J, Schultz G, Koesling D. A functional heme-binding site of soluble guanylyl cyclase requires intact N-termini of alpha 1 and beta 1 subunits. Eur J Biochem. 1996;240:380–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0380h.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balashova N, Chang FJ, Lamothe M, Sun Q, Beuve A. Characterization of a novel type of endogenous activator of soluble guanylyl cyclase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:2186–2196. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411545200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Russwurm M, Wittau N, Koesling D. Guanylyl cyclase/PSD-95 interaction: targeting of the nitric oxide-sensitive alpha2-beta1 guanylyl cyclase to synaptic membranes. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:44647–44652. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105587200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Linder AE, McCluskey LP, Cole KR, III, Lanning KM, Webb RC. Dynamic association of nitric oxide downstream signaling molecules with endothelial caveolin-1 in rat aorta. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;314:9–15. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.083634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Linder AE, Leite R, Lauria K, Mills TM, Webb RC. Penile erection requires association of soluble guanylyl cyclase with endothelial caveolin-1 in rat corpus cavernosum. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290:R1302–R1308. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00601.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Venema RC, Venema VJ, Ju H, Harris MB, Snead C, Jilling T, Dimitropoulou C, Maragoudakis ME, Catravas JD. Novel complexes of guanylate cyclase with heat shock protein 90 and nitric oxide synthase. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H669–H678. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01025.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Airhart N, Yang YF, Roberts CT, Jr, Silberbach M. Atrial natriuretic peptide induces natriuretic peptide receptor-cGMP-dependent protein kinase interaction. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:38693–38698. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304098200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garcia-Cardena G, Martasek P, Masters BS, Skidd PM, Couet J, Li S, Lisanti MP, Sessa WC. Dissecting the interaction between nitric oxide synthase (NOS) and caveolin. Functional significance of the nos caveolin binding domain in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:25437–25440. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Russell KS, Haynes MP, Caulin-Glaser T, Rosneck J, Sessa WC, Bender JR. Estrogen stimulates heat shock protein 90 binding to endothelial nitric oxide synthase in human vascular endothelial cells. Effects on calcium sensitivity and NO release. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:5026–5030. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.7.5026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dedio J, Konig P, Wohlfart P, Schroeder C, Kummer W, Muller-Esterl W. NOSIP, a novel modulator of endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity. Faseb J. 2001;15:79–89. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0078com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cao S, Yao J, McCabe TJ, Yao Q, Katusic ZS, Sessa WC, Shah V. Direct interaction between endothelial nitric-oxide synthase and dynamin-2. Implications for nitric-oxide synthase function. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:14249–14256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006258200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Potter LR, Garbers DL. Dephosphorylation of the guanylyl cyclase-A receptor causes desensitization. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:14531–14534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newaz MA, Ranganna K, Oyekan AO. Relationship between PPARalpha activation and NO on proximal tubular Na+ transport in the rat. BMC Pharmacol. 2004;4:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2210-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aperia A, Holtback U, Syren ML, Svensson LB, Fryckstedt J, Greengard P. Activation/deactivation of renal Na+, K(+)-ATPase: a final common pathway for regulation of natriuresis. Faseb J. 1994;8:436–439. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.8.6.8168694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beltowski J, Marciniak A, Wojcicka G, Gorny D. Regulation of renal Na(+), K(+)-ATPase and ouabain-sensitive H(+), K(+)-ATPase by the cyclic AMP-protein kinase A signal transduction pathway. Acta Biochim Pol. 2003;50:103–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elesgaray R, Caniffi C, Ierace DR, Jaime MF, Fellet A, Arranz C, Costa MA. Signaling cascade that mediates endothelial nitric oxide synthase activation induced by atrial natriuretic peptide. Regul Pept. 2008;151:130–134. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McLay JS, Chatterjee PK, Jardine AG, Hawksworth GM. Atrial natriuretic factor modulates nitric oxide production: an ANF-C receptor-mediated effect. J Hypertens. 1995;13:625–630. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199506000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.William M, Hamilton EJ, Garcia A, Bundgaard H, Chia KK, Figtree GA, Rasmussen HH. Natriuretic peptides stimulate the cardiac sodium pump via NPR-C-coupled NOS activation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;294:C1067–C1073. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00243.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Correa AH, Choi MR, Gironacci M, Valera MS, Fernandez BE. Signaling pathways involved in atrial natriuretic factor and dopamine regulation of renal Na+, K+-ATPase activity. Regul Pept. 2007;138:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hakam AC, Hussain T. Angiotensin II AT2 receptors inhibit proximal tubular Na+-K+-ATPase activity via a NO/cGMP-dependent pathway. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;290:F1430–F1436. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00218.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abraham NG. Gene targeting and heme oxygenase-1 expression in prevention of hypertension induced by angiotensin II. Hypertension. 2008;52:618–620. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.117762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]