Abstract

Objective

The aim of the study was to examine the rates and predictors of treatment modification following combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) failure in Asian patients with HIV enrolled in the TREAT Asia HIV Observational Database (TAHOD).

Methods

Treatment failure (immunological, virological and clinical) was defined by World Health Organization criteria. Countries were categorized as high or low income by World Bank criteria.

Results

Among 2446 patients who initiated cART, 447 were documented to have developed treatment failure over 5697 person-years (7.8 per 100 person-years). A total of 253 patients changed at least one drug after failure (51.6 per 100 person-years). There was no difference between patients from high- and low-income countries [adjusted hazard ratio (HR) 1.02; P = 0.891]. Advanced disease stage [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) category C vs. A; adjusted HR 1.38, P = 0.040], a lower CD4 count (≥ 51 cells/μL vs. ≤ 50 cells/μL; adjusted HR 0.61, P = 0.022) and a higher HIV viral load (≥ 400 HIV-1 RNA copies/mL vs. < 400 copies/mL; adjusted HR 2.69, P < 0.001) were associated with a higher rate of treatment modification after failure. Compared with patients from low-income countries, patients from high-income countries were more likely to change two or more drugs (67% vs. 49%; P = 0.009) and to change to a protease-inhibitor-containing regimen (48% vs. 16%; P< 0.001).

Conclusions

In a cohort of Asian patients with HIV infection, nearly half remained on the failing regimen in the first year following documented treatment failure. This deferred modification is likely to have negative implications for accumulation of drug resistance and response to second-line treatment. There is a need to scale up the availability of second-line regimens and virological monitoring in this region.

Keywords: antiretroviral treatment, Asia Pacific region, observational cohort, treatment failure

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that about 3 million people were receiving antiretroviral therapy by the end of 2007, nearly 950 000 more compared with the year before and a 7.5-fold increase over the past 4 years [1].

The aim of antiretroviral treatment is to prolong life by suppression of viral replication to below the level of detection with standard assays in plasma, leading to immune reconstitution [2]. The decision to modify a treatment regimen when treatment failure develops is crucial to prevent the accumulation of drug resistance and preserve any remaining activity within the nucleoside (nucleotide) reverse transcriptase inhibitor [N(t)RTI] class, thereby ensuring the maximal effectiveness of second-line therapy, as agents from N(t)RTIs are recommended in combination with a boosted protease inhibitor [3–5].

There are few data on antiretroviral change following treatment failure that can inform decisions in HIV-infected patients in the Asia and Pacific region, where many settings are resource-limited and diagnostic and resistance testing is not routinely available. In addition, there is limited access to effective new antiretroviral regimens in many developing countries in the Asia and Pacific region [6,7].

The objective of this paper was to examine the rates and predictors of treatment modification following documented treatment failure in Asian patients, using data from the TREAT Asia HIV Observational Database (TAHOD).

Methods

TAHOD is a collaborative observational cohort study involving 17 participating clinical sites in the Asia and Pacific region (see Acknowledgements). Detailed methods are published elsewhere [8]; briefly, each site recruited approximately 200 patients, both treated and untreated with antiretroviral therapy; recruitment was based on a consecutive series of patients regularly attending a given clinical site from a particular start-up time; Ethics Committee approval for the study was obtained from the University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Committee and from a local ethics committee for each participating TAHOD site.

The following data were collected: (i) patient demographics and baseline data: date of the clinical visit, age, sex, ethnicity, exposure category, date of first positive HIV test, HIV-1 subtype, and date and result of hepatitis B, hepatitis C and syphilis serology; (ii) stage of disease: CD4 and CD8 cell count, HIV viral load, prior and new AIDS-defining illnesses, and date and cause of death; (iii) treatment history: prior and current prescribed antiretro-viral treatments, reason for treatment changes and prophylactic treatments for opportunistic infections. The reasons for treatment change were coded as treatment failure, clinical progression or hospitalization, patient decision or request, compliance difficulties, drug interaction, adverse events and other reasons.

TAHOD patients were included in the analysis if they were naïve to antiretroviral treatment, and had initiated treatment with triple or more combination therapy since 1996. Treatment failure was defined using WHO guidelines for antiretroviral therapy for adults and adolescents [3]. The guidelines include definitions according to immunological, virological and clinical status to guide modification of treatment:

CD4 cell count: after 6 months of therapy, a CD4 cell count below the pretreatment level, or a 50% decline from the on-treatment peak CD4 cell count, or three consecutive CD4 counts below 100 cells/μL;

HIV viral load: after 6 months of therapy, an HIV viral load test result of >10 000 copies/mL;

Clinical progression: after 6 months of therapy, development of an AIDS-defining illness.

The date of treatment failure was identified from the database according to the WHO guidelines. The earliest failure was included for patients with more than one type of failure during treatment.

TAHOD sites were grouped into low (low and lower-middle) and high (upper-middle and upper) income categories according to the gross national income per capita from The World Bank [9].

Modification of antiretroviral treatment following treatment failure was defined as a change to (adding, stopping or substituting) at least one drug in the treatment combination received at the time at which treatment failure was identified. A treatment modification with a duration of 14 days or less was ignored. TAHOD sites were asked to provide reasons when an antiretroviral drug was stopped, using a standard format specified in the TAHOD protocol. The reasons include treatment failure, clinical progression/hospitalization, patient decision/request, compliance difficulties, drug interaction, adverse event and other.

Follow-up was censored at the date of treatment change or the last clinical visit. Time to treatment modification was determined by univariate and multivariate survival analysis methods (Kaplan–Meier and Cox proportional hazards models). Predictors associated with modification after treatment failure were assessed using multivariate Cox proportional hazards models with a forward stepwise approach. The final multivariate model was stratified by site and included only covariates that remained significant at the 0.05 level (two-sided). Nonsignificant variables were presented and adjusted for final multivariate models. Analysis was performed using the statistical package STATA 10 for Windows (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Up to March 2007, there were 2446 TAHOD patients who were treatment-naïve and initiated combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) regimens after 1996. There were 16 patients who died after treatment initiation and before a treatment failure was identified; of these, five patients died from AIDS-related causes, seven from non-AIDS-related causes and four from unknown causes. The median treatment period was 1.97 years [interquartile range (IQR) 0.75–3.55 years]. During the treatment period, the median number of CD4 tests was 4 (IQR 2–8), the median interval between each CD4 test was 147 days (IQR 105–200 days), the median number of HIV viral load tests was also 4 (IQR 2–7), and the median interval between each viral load test was 168 days (IQR 112–231 days). The proportion of patients having four or more CD4 tests and/or viral tests varied considerably across the TAHOD sites (from < 10% to over 80%).

A total of 447 patients were identified with at least one type of treatment failure [Table 1; rate of treatment failure 7.85 per 100 person-years; 95% confidence interval (CI) 7.15–8.61]. There were 277 patients with immunological failure (after 6 months of therapy, 151 with a CD4 cell count below the pretreatment level; 157 with a 50% decline from the on-treatment peak CD4 cell count; and 36 with three consecutive CD4 counts below 100 cells/μL), 158 patients with virological failure (>10 000 copies/mL after 6 months of therapy), and 116 patients with an AIDS-defining illness diagnosed after 6 months of therapy. For a patient with multiple documented failures, the earliest failure was identified for analysis in this paper (242 with immunological failure, 112 with virological failure and 93 with disease progression; a total of 447 patients).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (n = 447)

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 342 (77) |

| Female | 105 (23) |

| Age at time of failure (years) | |

| ≤30 | 119 (27) |

| 31–40 | 203 (45) |

| 41 + | 125 (28) |

| Reported mode of infection | |

| Heterosexual contact | 288 (65) |

| Homosexual contact | 94 (21) |

| Injecting drug use | 24 (5) |

| Blood products | 32 (7) |

| Other/unknown | 9 (2) |

| CDC classification at time of failure | |

| Category A | 173 (39) |

| Category B | 39 (9) |

| Category C | 235 (52) |

| Country income category | |

| Low-income | 323 (72) |

| High-income | 124 (28) |

| CD4 count (cells/μL) at time of failure | |

| ≤50 | 39 (9) |

| 51 + | 349 (78) |

| 51–100 | 46 (10) |

| 101–200 | 108 (24) |

| 201–300 | 91 (20) |

| 301 + | 104 (23) |

| Not tested | 59 (13) |

| HIV viral load (copies/mL) at time of failure | |

| <400 | 121 (27) |

| 400 or more | 145 (33) |

| 400–10 000 | 13 (3) |

| 10 000 + | 132 (30) |

| Not tested | 181 (40) |

| Antiretroviral treatment* at time of failure | |

| 3 + (NRTI +NNRTI – PI) | 318 (71) |

| 3 +(NRTI – NNRTI + PI) | 100 (22) |

| Others | 29 (7) |

| Type of treatment failure | |

| Immunological | 242 (54) |

| Virological | 112 (25) |

| Clinical | 93 (21) |

Antiretroviral treatment:

3 + (NRTI + NNRTI – PI), combination of three or more drugs including NRTI and NNRTI but not PI.

3 + (NRTI – NNRTI + PI), combination of three or more drugs including NRTI and PI but not NNRTI.

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; PI, protease inhibitor; NRTI, nucleoside (nucleotide) reverse transcriptase inhibitor; NNRTI, nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor.

Following treatment failure, a total of 253 patients had a treatment modification after failure, of whom 44 had their treatment modified on the same day on which treatment failure was identified. During a median follow-up time of 0.64 years (IQR 0.15–1.61 years), a further 209 patients changed at least one drug. The rate of treatment modification after failure was 51.6 per 100 person-years (95% CI 45.6–58.4). Of the 194 patients whose treatment was not modified after treatment failure, three patients died, and 18 patients were lost to follow-up.

Time to treatment modification after failure, by country income category and by type of treatment failure, is shown in Figure 1. The rate of treatment modification was similar in patients from high- and low-income countries. However, the rate of modification was higher in patients with a virological failure than in patients with either immunological failure or clinical progression. At the end of the first year following failure, approximately 40% of patients with virological failure remained on the previous regimen, compared with over 60% of patients with either immunological failure or clinical progression.

Fig. 1.

Time to treatment modification after treatment failure, by country income category and type of treatment failure. cART, combination antiretroviral therapy.

Table 2 shows the factors associated with time to antiretroviral treatment modification after treatment failure by univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards models. In the final model (stratified by TAHOD sites) the factors independently associated with treatment modification after failure included CDC classification, CD4 cell count and HIV viral load, all at the time of treatment failure: compared with patients who were in CDC category A, patients in category C were more likely to have a modification of treatment [hazard ratio (HR) 1.38, CI 1.01–1.87, P = 0.040]; compared with patients with a CD4 count ≤ 50 cells/μL at the time of failure, patients with a CD4 count ≥ 51 cells/μL were less likely have their treatment modified (HR 0.61, CI 0.40–0.93, P = 0.022); lastly, compared with patients with an HIV load < 400 copies/mL at the time of failure, patients with an HIV viral load ≥ 400 copies/mL or those with an unavailable HIV load were more likely to have their treatment modified (HR 2.69, CI 1.90–3.81, P< 0.001; HR 1.74, CI 1.14–2.66, P = 0.010, respectively).

Table 2.

Time to treatment modification following treatment failure

| No. patients | Follow-up (years) | No. of events | Rate (/100py) | Univariate HR | Multivariate*P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 447 | 490 | 253 | 51.6 | ||||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 342 | 374 | 197 | 52.7 | ||||

| Female | 105 | 116 | 56 | 48.3 | 0.93 | 0.640 | 0.87 (0.63, 1.22) | 0.423 |

| Age at time of failure (years) | ||||||||

| ≤ 30 | 119 | 143 | 63 | 44.2 | ||||

| 31–40 | 203 | 208 | 116 | 55.7 | 1.23 | 0.193 | 1.19 (0.86, 1.66) | 0.294 |

| 41 + | 125 | 139 | 74 | 53.1 | 1.22 | 0.243 | 1.20 (0.84, 1.74) | 0.319 |

| Reported mode of infection | ||||||||

| Heterosexual contact | 288 | 328 | 162 | 49.5 | ||||

| Homosexual contact | 94 | 117 | 50 | 42.8 | 0.89 | 0.461 | 0.66 (0.42, 1.05) | 0.079 |

| Injecting drug use | 24 | 22 | 16 | 71.6 | 1.26 | 0.366 | 1.25 (0.67, 2.32) | 0.484 |

| Blood products | 32 | 18 | 19 | 103.0 | 1.73 | 0.024 | 1.02 (0.48, 2.14) | 0.968 |

| Other/unknown | 9 | 5 | 6 | 109.7 | 1.64 | 0.238 | 1.34 (0.55, 3.29) | 0.519 |

| CDC classification at time of failure | ||||||||

| Category A | 173 | 192 | 95 | 49.4 | ||||

| Category B | 39 | 43 | 18 | 41.4 | 0.82 | 0.448 | 1.25 (0.70, 2.23) | 0.444 |

| Category C | 235 | 255 | 140 | 55.0 | 1.08 | 0.567 | 1.38 (1.01, 1.87) | 0.040 |

| CD4 count (cells/μL) at time of failure | ||||||||

| ≤ 50 | 39 | 29 | 30 | 104.3 | ||||

| 51 + | 349 | 386 | 192 | 49.7 | 0.56 | 0.003 | 0.61 (0.40, 0.93) | 0.022 |

| Not tested | 59 | 75 | 31 | 41.4 | 0.49 | 0.006 | 0.60 (0.34, 1.05) | 0.074 |

| HIV viral load (copies/mL) at time of failure | ||||||||

| < 400 | 121 | 169 | 56 | 33.1 | ||||

| 400 or more | 145 | 107 | 106 | 99.5 | 2.46 | o0.001 | 2.69 (1.90, 3.81) | o0.001 |

| Not tested | 181 | 214 | 91 | 42.4 | 1.25 | 0.196 | 1.74 (1.14, 2.66) | 0.010 |

| Antiretroviral treatment† at time of failure | ||||||||

| 3 +(NRTI + NNRTI-PI) | 318 | 376 | 168 | 44.7 | ||||

| 3 +(NRTI-NNRTI + PI) | 100 | 86 | 61 | 70.4 | 1.37 | 0.038 | 1.28 (0.91, 1.82) | 0.157 |

| Others | 29 | 28 | 24 | 87.5 | 1.83 | 0.006 | 1.58 (0.96, 2.57) | 0.069 |

| Type of treatment failure | ||||||||

| Immunological | 242 | 273 | 123 | 45.0 | ||||

| Virological | 112 | 89 | 82 | 91.8 | 1.83 | o0.001 | 0.90 (0.53, 1.53) | 0.704 |

| Clinical | 93 | 128 | 48 | 37.6 | 0.91 | 0.595 | 1.02 (0.63, 1.65) | 0.941 |

| Country income category | ||||||||

| Low-income | 323 | 346 | 178 | 51.4 | ||||

| High-income | 124 | 144 | 75 | 52.2 | 1.03 | 0.829 | 1.02 (0.77, 1.35) | 0.891 |

Stratified by site (except for country income category).

Antiretroviral treatment:

3 + (NRTI + NNRTI-PI), combination of three or more drugs including NRTI and NNRTI but not PI.

3 +(NRTI-NNRTI +PI), combination of three or more drugs including NRTI and PI but not NNRTI.

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; PI, protease inhibitor; py, person-years; NRTI, nucleoside (nucleotide) reverse transcriptase inhibitor; NNRTI, nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor.

Values in bold were factors associated with treatment change in the final model.

Overall, there was little difference between high- and low-income sites in terms of time to treatment modification after failure. However, from Figure 1 it appears that there may be some divergence after 2 years. We therefore performed an additional stratified analysis, comparing high- and low-income countries in the first 2 years, and more than 2 years, after failure. In the first 2 years, the rate of modification was similar in low- and high-income countries (low- vs. high-income, HR 1.08, 95% CI 0.80–1.46, P = 0.632). In follow-up after 2 years, the rate was lower in patients from low-income countries; however, possibly because of the small numbers of patients with up to 2 years of follow-up (90 in total), the difference was not statistically significant (low vs. high, HR 0.49, 95% CI 0.23–1.03, P = 0.059). Sensitivity analyses were also performed on patients who started treatment in or after 2003; the results were similar to those obtained when all eligible patients were included (data not shown).

When their treatment was modified, 24 (10% of 253) patients had one or more drugs added, 92 (36%) had one drug changed and 137 (54%) had two or more drugs changed. Although the rates of treatment modification were similar in patients from high- and low-income countries (adjusted HR 1.02, P = 0.891), patients from high-income countries were more likely to have two or more drugs changed (67% vs. 49%, P = 0.009) and to change to a protease-inhibitor-based regimen (48% vs. 16%, P < 0.001).

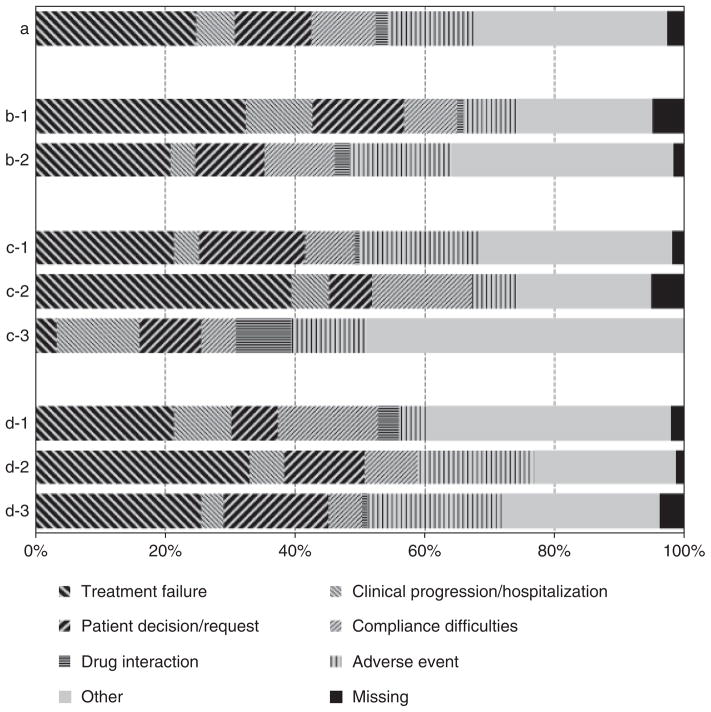

Figure 2 shows the reported reasons for stopping a drug when treatment was modified, summarized according to country income category, type of treatment failure and time from treatment failure. Treatment failure was only one of the reasons for modifying drugs (25% of all reported reasons). Patients from high-income countries were more likely to report treatment failure as the reason for stopping a drug than those from low-income countries (32% vs. 21%, P = 0.003). More drugs were reported to be stopped because of treatment failure following an identified virological failure than following immunological failure and clinical progression (39% vs. 21% and 3%, respectively; P< 0.001). Treatment failure as the reason for stopping a drug was reported at similar rates in the first 90 days, at 91–180 days and at 181 days or more from the documented treatment failure (26%, 33% and 21%, respectively; P = 0.125).

Fig. 2.

Reported reasons for stopping a drug when treatment was modified. (a) all drugs; (b) by country income category (b-1, low-income; b-2, high-income); (c) by type of treatment failure (c-1, immunological failure; c-2, virological failure; c-3, clinical progression), (d) by time from treatment failure (d-1, up to 90 days; d-2, 91–180 days; d-3, 181 days or more).

Discussion

In this study, we found that among a cohort of HIV-infected patients in the Asia and Pacific region, in the first year following documented treatment failure, nearly half remained on the same failing regimen. Advanced disease stage (CDC category C), lower CD4 cell count and higher HIV viral load were associated with a higher rate of treatment modification after failure. Compared with patients from low-income countries, patients from high-income countries were more likely to have two or more drugs changed and to change to a protease-inhibitor-based regimen when their treatment was modified after failure.

Definitions of treatment failure vary in the guidelines from different countries and regions [3,10–12]. The WHO guidelines include definitions according to immunological, virological and clinical status to guide modification of treatment, taking into consideration the fact that sophisticated laboratory investigations, including baseline and longitudinal CD4 and viral load measurements, are not always available and are likely to remain limited in the short- to mid-term for a number of reasons, including cost and capacity. It is perhaps not surprising in our study that the TAHOD patients from sites in high-income countries had more drugs to change and more access to protease-inhibitor-based regimens. Previous analysis in TAHOD [13] showed that drug availability influences treatment prescription patterns.

According to the WHO guidelines [3], when HIV viral load testing is not available, patients with immunological failure are not recommended to switch treatment if they have WHO stage 2 or 3 disease (i.e. not stage 4). The WHO guidelines also recommend that premature modification from first-line to second-line treatment should be avoided, with the assumption that the provision of second-line drugs is in the public sector and the availability is usually limited. This may mean that clinicians are not willing to modify the regimen immediately in the presence of treatment failure if virological failure cannot be confirmed. The higher rate of modification after virological failure in TAHOD than after immunological and clinical failure lends support to this interpretation. However, there remain a large proportion of patients (nearly 40%) who continue the same failing regimen 1 year after identification of virological failure, which is probably a result of the limited treatment options available. We found that advanced disease stage (CDC category C), a lower CD4 cell count and a higher HIV viral load were associated with a higher rate of treatment modification after failure. This probably indicates that the clinicians in TAHOD clinics were prioritizing treatment options to those failed patients with more advanced immune deficiency as a result of limited resources.

In a case note and questionnaire-based audit in the United Kingdom [14], after virological failure (defined as a viral load rebound from undetectable, not reaching an undetectable level, and/or an increase in viral load), change of therapy was found to occur in < 4 months in 43% of patients, in 4–6 months in 20% of patients and in >6 months in 34% of patients. Of the patients with virological failure who had their treatment modified, 48% switched to three or more new drugs, 32% to two new drugs and 20% to one new drug. In another study from the United Kingdom, Collaborative HIV Cohort (CHIC) [15], only one-third of patients remained on a failing regimen for more than 6 months after virological rebound of >400 copies/mL, and the proportions were 20% and 9% at 1 and 2 years after rebound, respectively. The rate of treatment modification after treatment failure in TAHOD patients is clearly slower than that seen in the United Kingdom, where routine HIV viral load tests and second-line treatment options are readily available.

Treatment failure was only one of the reported reasons for modification of treatment after identification of failure. These clinical data provide an insight into clinical practice with regard to HIV treatment and care in the Asia and Pacific region. Adverse events were reported to be a major reason for treatment change after initiation, both in TAHOD [13,16] and in other cohorts [14]. This suggests that the TAHOD clinicians are aware of the adverse effects associated with cART and are ready to change treatment if toxicity is present. The difference in the proportions of reported reasons for stopping a drug between high- and low-income countries may reflect differences in the availability of clinical monitoring, treatment and care, and clinical expertise in the Asia and Pacific region.

One systematic review [17] showed that there is insufficient evidence to evaluate second-line therapies in patients with HIV infection who fail first-line treatment with nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) + N(t)RTI combinations. Individualized treatment decisions are recommended to be based on patient treatment history, appropriate agents for inclusion and HIV drug resistance testing. A number of new agents, including some in new antiretroviral classes [for instance CCR5 inhibitors (e.g. maraviroc) and integrase strand transfer inhibitors (e.g. InSTI and raltegravir)], have recently been approved, raising the possibility that second-line therapy could be constructed from two agents from two drug classes to which the patient is naïve (e.g. a boosted protease inhibitor plus InSTI). Such a strategy would remove the need for genotypic resistance testing and would be more consistent with the simplified, public health approach to antiretroviral management recommended for use in resource-limited settings [18]. There is a need to design randomized controlled trials to determine optimal second-line therapy strategies for both resource-rich and resource-limited settings.

Failure of first-line antiretroviral therapy is inevitable sooner or later in a proportion of patients. Access to second-line antiretroviral therapy regimens in developing countries is limited by the expense of second-line treatment as a result of the inclusion of protease inhibitors [7]; the cost of a protease-inhibitor-containing second-line regimen is in the order of five times the cost of the cheapest available fixed-dose generic NNRTI + N(t)RTI combination. It was estimated that in India, by 2, 3 and 3.5 years after 2007, there will be 16 000, 35 000 and 51000 patients, respectively, who are currently receiving antiretroviral therapy and who are likely to require second-line treatment [19].

In resource-limited settings where second-line treatment options are limited, and where preservation of activity in the N(t)RTI class may be critical to the success of second-line therapy, it is crucial to prevent HIV drug resistance. Early detection of virological failure may provide more options and better treatment outcomes [20]. Orrell et al. [21] also showed that regular follow-up with viral load tests and adherence intervention by a peer counsellor is associated with a low rate of treatment failure, which leads to the retention of individuals on first-line therapy and the conservation of more expensive second-line treatment options. With the increasing need for second-line regimens, more effort should be made urgently to ensure HIV viral load testing becomes affordable, simple and easy to use in routine clinical practice, even in resource-limited settings [22,23]

Several limitations should be considered in interpreting the results in this paper. One recent study [24] showed that WHO clinical and CD4 criteria have poor sensitivity and specificity in detecting virological failure. The observational nature of TAHOD means that treatment failure was identified depending on the local clinic approach, which would differ across the TAHOD sites. The frequency of CD4 testing and HIV viral load measurement varies significantly across the TAHOD sites, and, in particular, there is no systematic monitoring of CD4 and/or HIV viral load testing at TAHOD sites according to a standardized visit schedule. These issues relating to differences in monitoring among sites may result in underestimation of the overall rate of treatment failure and hence actual treatment modification may have been deferred for even longer times. However, the main objective of this paper was to examine the time from any documented treatment failure to any treatment change. The failures we analysed were documented treatment failures, and so might be expected to give an indication of real-life clinical practice in this region. In addition, adherence data are not collected in TAHOD, and it is possible that in the presence of failure another reason for the delay in treatment switch may be that clinicians were trying to improve adherence to the existing regimen before definitively declaring treatment failure. Furthermore, as TAHOD participating sites are generally urban referral centres, and each site recruits approximately 200 patients who are judged to have a reasonably good prospect of long-term follow-up, TAHOD patients may not be entirely representative of HIV-infected patients in the Asia and Pacific region. Finally, a more thorough analysis would include the survival outcome of treatment change after treatment failure was identified. However, because of the limited number and follow-up of patients who have treatment modification after failure, this analysis is currently underpowered, and a further analysis will be performed when TAHOD has more follow-up data.

Deferred modification of regimen following treatment failure in many Asian countries following rapid scale-up of antiretroviral treatment is likely to have negative implications for accumulation of drug resistance and response to second-line treatment which incorporates agents from the N(t)RTI class. There is a need to scale up the availability of agents for use in second-line regimens and implement the use of virological monitoring in this region.

Acknowledgments

The TREAT Asia HIV Observational Database is part of the Asia Pacific HIV Observational Database and is an initiative of TREAT Asia, a programme of The Foundation for AIDS Research (amfAR), with support from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) of the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) as part of the International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) (grant no. U01AI069907), and from the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs through a partnership with Stichting Aids Fonds. The National Centre in HIV Epidemiology and Clinical Research is funded by the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, and is affiliated with the Faculty of Medicine, The University of New South Wales. The content of this publication is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent he official views of any of the institutions mentioned above.

Appendix: the TREAT Asia HIV Observational Database

C. V. Mean, V. Saphonn* and K. Vohith, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Dermatology & STDs, Phnom Penh, Cambodia; F. J. Zhang*, H. X. Zhao and N. Han, Beijing Ditan Hospital, Beijing, China; P. C. K. Li*† and M. P. Lee, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong, China; N. Kumarasamy* and S. Saghayam, YRG Centre for AIDS Research and Education, Chennai, India; S. Pujari* and K. Joshi, Institute of Infectious Diseases, Pune, India; T. P. Merati* and F. Yuliana, Faculty of Medicine, Udayana University & Sanglah Hospital, Bali, Indonesia; S. Oka* and M. Honda, International Medical Centre of Japan, Tokyo, Japan; J. Y. Choi* and S. H. Han, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, South Korea; C. K. C. Lee* and R. David, Hospital Sungai Buloh, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; A. Kamarulzaman* and A. Kajindran, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; G. Tau*, Port Moresby General Hospital, Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea; R. Ditangco* and R. Capistrano, Research Institute for Tropical Medicine, Manila, Philippines; Y. M. A. Chen*, W. W. Wong and Y. W. Yang, Taipei Veterans General Hospital and AIDS Prevention and Research Centre, National Yang-Ming University, Taipei, Taiwan; P. L. Lim*, O. T. Ng and E. Foo, Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore; P. Phanuphak* and M. Khong-phattanayothing, HIV-NAT/Thai Red Cross AIDS Research Centre, Bangkok, Thailand; S. Sungkanuparph* and B. Piyavong, Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand; T. Sirisanthana*‡ and W. Kotarathiti-tum, Research Institute for Health Sciences, Chiang Mai, Thailand; J. Chuah*, Gold Coast Sexual Health Clinic, Miami, Queensland, Australia; A. H. Sohn*, J. Smith* and B. Nakornsri, The Foundation for AIDS Research, New York, USA; D. A. Cooper, M. G. Law* and J. Zhou*, National Centre in HIV Epidemiology and Clinical Research, The University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia. *TAHOD Steering Committee member; † Steering Committee chair; ‡co-chair.

References

- 1.WHO. Towards Universal Access, Scaling up Priority HIV/AIDS Interventions in the Health Sector, Progress Report 2008. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hammer SM, Saag MS, Schechter M, et al. Treatment for adult HIV infection: 2006 recommendations of the International AIDS Society-USA Panel. JAMA. 2006;296:827–843. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.7.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO. Antiretroviral Therapy for HIV Infection in Adults and Adolescents. Recommendations for a Public Health Approach. 2006 Revision. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spacek LA, Shihab HM, Kamya MR, et al. Response to antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected patients attending a public, urban clinic in Kampala, Uganda. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42 :252–259. doi: 10.1086/499044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marconi VC, Sunpath H, Lu Z, et al. Prevalence of HIV-1 drug resistance after failure of a first highly active antiretroviral therapy regimen in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1589–1597. doi: 10.1086/587109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hogan DR, Salomon JA. Prevention and treatment of human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in resource-limited settings. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:135–143. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyd MA, Cooper DA. Second-line combination antiretroviral therapy in resource-limited settings: facing the challenges through clinical research. AIDS. 2007;21 (Suppl 4):S55–S63. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000279707.01557.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou J, Kumarasamy N, Ditangco R, et al. The TREAT Asia HIV Observational Database: baseline and retrospective data. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;38:174–179. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000145351.96815.d5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The World Bank. [accessed 15 March 2008];The World Bank Country Classification. 2008 Available at http://go.worldbank.org/K2CKM78CC0.

- 10.European Medicines Agency. [accessed 15 May 2005];Guideline on the choice of the non-inferiority margin. 2005 Available at www.emea.europa.eu/pdfs/human/ewp/215899en.pdf.

- 11.Gazzard BG on behalf of the BHIVA Treatment Guidelines Writing Group. British HIV Association guidelines for the treatment of HIV-1-infected adults with antiretroviral therapy 2008. HIV Med. 2008;9:563–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2008.00636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Department of Health and Human Services; Jan 29, 2008. [accessed 4 August 2008]. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. Available at www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/ContentFiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Srasuebkul P, Calmy A, Zhou J, Kumarasamy N, Law M, Lim PL. Impact of drug classes and treatment availability on the rate of antiretroviral treatment change in the TREAT Asia HIV Observational Database (TAHOD) AIDS Res Ther. 2007;4:18. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-4-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hart E, Curtis H, Wilkins E, Johnson M. National review of first treatment change after starting highly active antiretroviral therapy in antiretroviral-naïve patients. HIV Med. 2007;8:186–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2007.00451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee KJ, Dunn D, Porter K, et al. Treatment switches after viral rebound in HIV-infected adults starting antiretroviral therapy: multicentre cohort study. AIDS. 2008;22:1943–1950. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830e4cf3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou J, Paton N, Ditangco R, et al. Experience with the use of a first-line regimen of stavudine, lamivudine and nevirapine in patients in the TREAT Asia HIV Observational Database. HIV Med. 2007;8:8–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2007.00417.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Humphreys EH, Hernandez LB, Rutherford GW. Antiretroviral regimens for patients with HIV who fail first-line antiretroviral therapy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007:CD006517. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006517.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilks CF, Crowley S, Ekpini R, et al. The WHO public-health approach to antiretroviral treatment against HIV in resource-limited settings. Lancet. 2006;368:505–510. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69158-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rajasekaran S, Jeyaseelan L, Vijila S, Gomathi C, Raja K. Predictors of failure of first-line antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected adults: Indian experience. AIDS. 2007;21 (Suppl 4):S47–S53. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000279706.24428.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sungkanuparph S, Manosuthi W, Kiertiburanakul S, Piyavong B, Chumpathat N, Chantratita W. Options for a second-line antiretroviral regimen for HIV type 1-infected patients whose initial regimen of a fixed-dose combination of stavudine, lamivudine, and nevirapine fails. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:447–452. doi: 10.1086/510745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Orrell C, Harling G, Lawn SD, et al. Conservation of first-line antiretroviral treatment regimen where therapeutic options are limited. Antivir Ther. 2007;12:83–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calmy A, Ford N, Hirschel B, et al. HIV viral load monitoring in resource-limited regions: optional or necessary? Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:128–134. doi: 10.1086/510073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith DM, Schooley RT. Running with scissors: using antiretroviral therapy without monitoring viral load. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1598–1600. doi: 10.1086/587110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mee P, Fielding KL, Charalambous S, Churchyard GJ, Grant AD. Evaluation of the WHO criteria for antiretroviral treatment failure among adults in South Africa. AIDS. 2008;22:1971–1977. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830e4cd8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]