Abstract

ClpP is a serine protease whose active sites are sequestered in a cavity enclosed between two heptameric rings of subunits. The ability of ClpP to process folded protein substrates depends on its being partnered by an AAA+ ATPase/unfoldase, ClpA or ClpX. In active complexes, substrates are unfolded and fed along an axial channel to the degradation chamber inside ClpP. We have used cryoelectron microscopy at ∼11-Å resolution to investigate the three-dimensional structure of ClpP complexed with either one or two end-mounted ClpA hexamers. In the absence of ClpA, the apical region of ClpP is sealed; however, it opens on ClpA binding, creating an access channel. This region is occupied by the N-terminal loops (residues 1–17) of ClpP, which tend to be poorly visible in crystal structures, indicative of conformational variability. Nevertheless, we were able to model the closed-to-open transition that accompanies ClpA binding in terms of movements of these loops; in particular, “up” conformations of the loops correlate with the open state. The main part of ClpP, the barrel formed by 14 copies of residues 18–193, is essentially unchanged by the interaction with ClpA. Using difference mapping, we localized the binding site for ClpA to a peripheral pocket between adjacent ClpP subunits. Based on these observations, we propose that access to the ClpP degradation chamber is controlled allosterically by hinged movements of its N-terminal loops, which the symmetry-mismatched binding of ClpA suffices to induce.

Keywords: Allosteric Regulation, ATP-dependent Protease, Chaperone Chaperonin, Electron Microscopy, Peptidases

Introduction

Controlled proteolysis is essential for homeostasis in living cells, by serving to eliminate damaged or misfolded proteins and to limit correctly folded proteins to appropriate levels (1). Intracellular protein degradation is carried by bi-partite proteases such as the 26 S proteasome in eukaryotes and ClpAP in bacteria (2). In bacteria (and in mitochondria and chloroplasts), protein turnover is achieved in part by members of the Clp family (clp = caseinolytic protease), including ClpAP, ClpXP, and ClpYQ (HslUV) (3, 4). These proteases all consist of a ring-like regulatory component (e.g. ClpA) mounted coaxially on a barrel-shaped peptidase (e.g. ClpP). The regulator recognizes, binds, and unfolds valid substrates and translocates them into the peptidase for degradation. The regulator is (in ClpA) or includes (in the proteasome) a hexameric AAA+ unfoldase (5, 6). Although most of the more sophisticated functions of the protease (e.g. substrate selection) are assigned to the unfoldase, often in conjunction with associated factors (7, 8), the peptidase also has additional responsibilities. In particular, it may help to assemble the regulatory particle, and it must exclude all but specifically targeted substrates from the active sites to avoid damage to the surrounding proteome. Selected substrates, once unfolded, are thought to be threaded into the peptidase as linear polypeptides; however, experiments in the ClpXP system with cross-linked model substrates (9) have indicated that a wider bundle of two or three polypeptide chains can enter the ClpP degradation chamber. These considerations invoke the existence of a gating mechanism, raising the questions of how such a gate is formed and how it is regulated.

Escherichia coli ClpP is a tetradecameric barrel-shaped enzyme (10), formed by head-to-head stacking of two heptameric rings (11). Alone, ClpP can slowly degrade small peptides but requires the cooperation of ClpA or ClpX to process larger peptides or unfolded proteins and to process folded proteins (12–14). Substrates are fed axially into ClpP (15, 16) and hydrolyzed processively into peptides of 7 or 8 amino acids (17, 18). A number of crystal structures have been determined for ClpPs from several organisms (11, 19–23). The organization of the 21-kDa hatchet-shaped subunit is quite well conserved: it has three subdomains: a “handle,” a globular “head,” and an N-terminal loop. The handles interdigitate at the interface between the two rings, and the heads form the main body of the barrel (the catalytic serines are on the inside at the handle-head junction) (24). The N-loops are associated with the axial region but are somewhat enigmatic: in several crystal structures, they are partially or completely untraceable and thus have been conceived to be elements that are either mobile or do not fully comply with 7-fold symmetry. N-loops that have been seen in crystal structures have been classified in two groups: in the “up” conformation, a β-hairpin motif extends outward in an axial direction (20–22), whereas the “down” conformation is less well defined but appears to involve hairpins in orientations approximately perpendicular to the 7-fold axis (22). The near axial region that they occupy makes it likely that the N-terminal regions of ClpP subunits play a role in gating the channel.

The existence of a gating mechanism is suggested by several lines of evidence. Removal of 7 or more residues from the N terminus of ClpP provides greatly increased access to peptides of 8–30 residues (25). Moreover, deletion of 14 amino acids from the N terminus allows even large unfolded proteins to be degraded rapidly (26). These data imply that low peptidase activity is due to blockage of the axial channel by the N-terminal portions of ClpP. Gating is also suggested by the existence of allosteric mechanisms for increasing access to the degradation chamber. Binding of ClpA and ClpX in the absence of ATP hydrolysis is sufficient to increase accessibility for moderate sized peptides and to increase their cleavage rate by >50-fold (12, 27). Even more dramatically, binding of an antibiotic acyldepsipeptide in the absence of ClpA or ClpX allows ClpP to degrade unfolded proteins at rates comparable with the ClpA- or ClpX-activated rates (28). A recent study by synchrotron hydroxyl radical footprinting (25) reported that the N-loops become more solvent-exposed upon ClpA binding, a shift that would be consistent with ClpP opening upon ClpA attachment. Other studies have also attributed to them a role in ClpA/ClpX binding (20, 22, 23).

Although a considerable amount of high resolution structural information has been compiled on ClpP, the 6:7 symmetry mismatch between ClpA and ClpP (29) has hindered crystallographic analysis of ClpAP complexes. In this study, we have used cryoelectron microscopy (cryo-EM)2 to visualize ClpAP, aiming to gain insight into ClpP as complexed with ClpA and the structural changes that their interaction may entail. The availability of crystal structures for ClpP that could be fitted into the cryo-EM density maps allowed us to detect and characterize its changes in conformation that accompany binding of ClpA.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Protein Expression and Cryo-EM

ClpA and ClpP were expressed and purified as described (30–32). ClpAP complexes were assembled by mixing ClpP tetradecamers and preassembled ClpA hexamers in 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mm KCl, 10 mm MgCl2 to final concentrations of ∼70 μg/ml (ClpP) and ∼120 μg/ml (ClpA). 3-μl drops of sample were applied to EM grids bearing holey carbon films. Excess fluid was then blotted away, and the grid quenched in liquid ethane, using a KF80 (Leica) or a Vitrobot (FEI) cryostation. Specimens were then transferred into a Philips CM200 FEG electron microscope, and focal pairs were recorded on Kodak SO-163 film under low dose conditions at 120 kV and ×38,000 magnification.

Three-dimensional Reconstruction of ClpP

Preprocessing of images was carried with the Bsoft package (33). Micrographs were first screened for the absence of drift or astigmatism and for showing a large proportion of ClpAP side views. Selected negatives were digitized on a Zeiss scanner at 7-μm step, giving 1.84 Å/pixel at the specimen. Separate particle sets were picked for the 1:1 and the 2:1 complex, using the further-from-focus image of each pair. Picked images were normalized and subjected to CTF correction, by phase flipping for orientation and with base-line correction added, for reconstruction.

To extract the ClpP parts of the ClpAP complexes, several cycles of classification by multivariate statistical analysis, averaging, and multireference alignment were performed in SPIDER (34), as described previously (35–37). To the aligned images, a rectangular mask centered on ClpP but including ∼25% of ClpA (when present) was applied. Data sets comprising 5132 (1982) focal pair images of the ClpP-containing portions of 1:1 (2:1) complexes were thus compiled and then used for three-dimensional reconstruction in SPIDER.

As a check against reference bias, two different starting models were used in the projection-matching scheme. One was a 7-fold-symmetrized two-dimensional class average representing a ClpP side view as determined by the two-dimensional classification described above. The second was a ClpP crystal structure (11), band limited to 20 Å. Both led to the same final structure. A first three-dimensional reconstruction was calculated using only the further-from-focus images; once a stable model was obtained, focal pairs were used. The sampling grid used in projection matching was reduced progressively to 3° intervals as orientations were refined until no significant improvement in resolution was observed from one cycle to the next. Phase-flipped images were used for projection matching and for back-projection-based reconstruction until the last few iterations where the CTF baseline-corrected images were used for reconstruction. With a priori knowledge that we were dealing with ClpP molecules in orientations close to side views, only particles with the Euler angle θ in the range 60 < θ < 90° were accepted for reconstruction. The final resolution determined by Fourier shell correlation at 0.5 (0.3) cutoff was 11.3 (10.0) Å for the 1:1 and 12.2 (11.6) Å for the 2:1 map.

Fitting of ClpP Crystal Structures and N-loop Modeling

The various ClpP crystal structures used in this study were fitted into the cryo-EM density maps in Chimera (38). ClpP tetradecamers were manually inserted into the EM maps, and their positions were locally refined, automatically, using the Fit in Map option. All manipulations and modifications of crystal structures were also done in Chimera. Density maps of the various crystal structures at reduced resolution were calculated in EMAN (39) with the pdb2mrc command.

For difference mapping, radial profiles for the resolution-limited density maps from crystal structures and the cryo-EM reconstructions were calculated using bradial in Bsoft (33). Maps were then scaled relative to the 1:1 reconstruction, and difference maps were generated in SPIDER (34).

RESULTS

Cryo-EM Structure of ClpP Complexed with 1 or 2 ClpA Hexamers

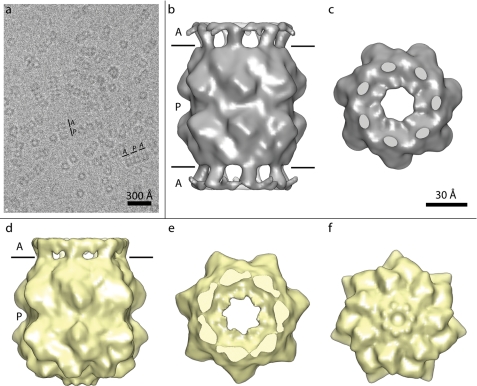

ClpAP complexes were formed by mixing equimolar amounts of ClpP tetradecamers and hexamers of ClpA, and cryo-EM data were acquired (e.g. Fig. 1a). These conditions give a majority of “1:1 complexes” with ClpA bound at one end of ClpP, but also some “2:1 complexes” with ClpA at both ends. We observed them in a ratio of ∼5:2 (see “Experimental Procedures”). Three-dimensional reconstructions of the ClpP-containing portions of both complexes were calculated, applying 7-fold symmetry. The 1:1 complex allowed us to compare the ClpA-bound and ClpA-free halves of the ClpP tetradecamer under identical imaging conditions. The 2:1 complexes allowed us to assess the reproducibility of the structure visualized at the ClpA-bound end. Because of a larger data set, the 1:1 map reached a slightly higher resolution, 11.3 Å versus 12.2 Å for the 2:1 map (supplemental Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Cryo-EM reconstructions of ClpP attached to 1 or 2 ClpA. a, cryo-EM showing a field of ClpAP complexes. Two side views, of a 1:1 (A P) and a 2:1 complex (A P A), are indexed. b and c, surface renderings of the ClpP-containing portion of the reconstructed 2:1 complex in side view (b) and axial view (c). d–f, surface renderings of the reconstructed 1:1 complex in side view (d) and both axial views (e and f). The boundaries between ClpA and ClpP are marked in b and d. The reconstructions were cross-cut at the levels marked to give the axial views shown in c and e.

To avoid truncating ClpP when images were masked out from side views of ClpAP complexes, the masking window used was somewhat longer than ClpP (120 versus 90 Å). In consequence, a small part of ClpA was included (when present), and we observed rings of density from this source on the apical surface of ClpP in both reconstructions. This ring is peripherally located at a radius of ∼30 Å from the symmetry axis (Fig. 1, b and d). Because ClpA is a hexamer, the 7-fold symmetry of this feature is artifactual; nevertheless, it allowed us to identify the interaction site between ClpA and ClpP in a molecular model (see below). Apart from these densities, the most striking difference between the two ends of the 1:1 complex is the presence of an axial channel at the ClpA-bound end (Fig. 1e); in contrast, this region is closed on the ClpA-free end (Fig. 1f). Otherwise, the two ClpP rings are essentially indistinguishable (cf. Fig. 1d).

In the 2:1 reconstruction, an opening similar to that seen at the ClpA-bound end of the 1:1 complex is observed at both ends (e.g. Fig. 1c). We note that D7 symmetry was imposed in the reconstruction only at a late stage, after confirming that both ends had a consistent appearance in a C7 reconstruction in which they were calculated separately (data not shown). Likewise, the structures visualized for both halves of the 2:1 complex (with C7 symmetry) tallied closely with the ClpA-bound part of the 1:1 complex, establishing its reproducibility. Except for the markedly different axial region and the ring of ClpA-associated density, there were no discernible differences between the ClpP heptamers at the ClpA-bound and ClpA-free ends (Fig. 1, b and d).

The Crystal Structure of the ClpP Core Fits Well into the Cryo-EM Density Maps

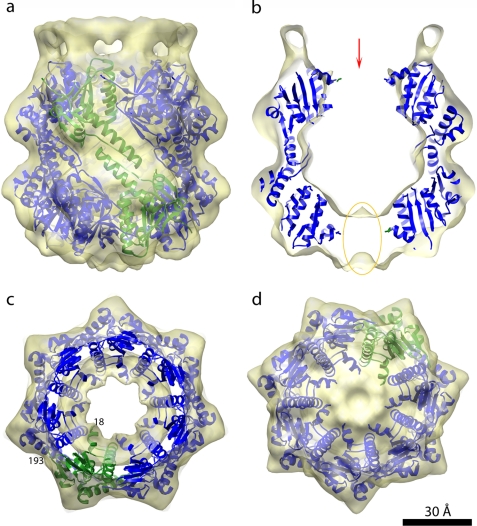

When crystal structure(s) for the barrel formed by 14 copies of residues 18–193 (from Ref. 11) of ClpP were fitted into the density maps of both the 1:1 (Fig. 2, a–d) and 2:1 (not shown in Fig. 2, but see Fig. 4) complexes, excellent agreement was obtained. At the ClpA-free end of the 1:1 complex, the reconstruction has unoccupied density only in its near axial region (Fig. 2b, orange oval, and Fig. 2d). Accordingly, and because residue 18 is immediately adjacent to this density (Fig. 2c), the observed axial closure of ClpP is attributable to its N-terminal regions (residues 1–17). At the ClpA-bound end, unoccupied density is limited to the ring of peripheral densities. However, these densities are too far from residue 18 to be contributed by N-terminal regions of ClpP (cf. Fig. 2b), further confirming that they are ClpA-derived.

FIGURE 2.

Fitting of an atomic model of the ClpP tetradecamer barrel (residues 18–193; PDB code 1tyf) into the cryo-EM reconstruction of the 1:1 complex. In all four panels, the cryo-EM map is shown as a transparent surface with the subunits represented as blue ribbon diagrams except for one subunit in each ring, colored in green. a, side view of the outer surface. b, cutaway side view contrasting the axial opening at the ClpA-bound end (red arrow) with the blocked axial channel at the ClpA-free end (orange oval). c and d show axial views from the ClpA-bound and the ClpA-free ends, respectively. The first residue on the head domain (residue 18) and its C terminus (residue 193) are marked on the green subunit in c.

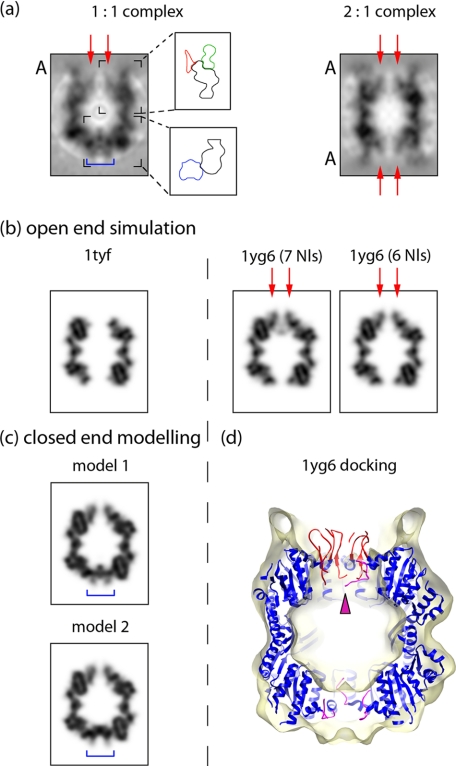

FIGURE 4.

Point of contact of ClpA on the surface of ClpP. a and b, axial (a) and side view (b) representations of the interaction between the ClpA and ClpP rings. The cryo-EM density for the 2:1 complex is shown in transparent gray, and the fitted ClpP model is in ribbon diagrams (red for residues 1–17 and blue for residues 18–193). Two neighboring subunits are colored yellow and cyan. The difference map between the cryo-EM density and a 12-Å resolution rendering of the docked ClpP model (residues 18–193) is overlaid in green. c, magnification of the marked region in b, with the cryo-EM density (other than the difference density) removed for clarity. Residues forming the pore at the interface of the yellow and cyan monomers and which have side chains pointing toward the ClpA density (green) are numbered and represented as balls and sticks.

Axial Density Differs Markedly between the ClpA-bound and the ClpA-free Ends of ClpP

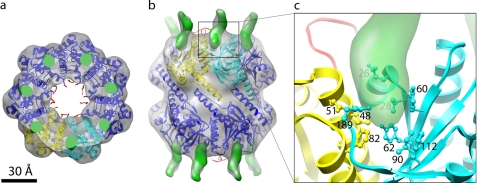

When the axial regions of the 1:1 complex are viewed in gray scale sections (as opposed to surface rendering), the ClpA-free end of ClpP is seen to be solidly blocked (blue bar in left panel in Fig. 3a). At the ClpA-bound ends of both complexes, the axial channel is reproducibly present but appears narrower (∼12 Å across) than in the surface renderings. In fact, this 12-Å channel is surrounded by a sleeve of density that, although significantly above background, is below the contour level used for rendering and therefore is not detected in that representation (Figs. 1, c and e, and 2b). This sleeve of density is pointed out by red arrows in Fig. 3a and outlined by a red contour in the upper enlarged box in Fig. 3a; the green contour outlines ClpA-associated density and the black contour, the ClpP barrel. It is noteworthy that the sleeve extends ∼15 Å beyond the apical surface of the barrel.

FIGURE 3.

Different distributions of N-loops in the ClpA-bound and ClpA-free states of ClpP. a, gray scale longitudinal central sections of the 1:1 (left) and 2:1 (right) reconstructions. A marks ends where ClpA is bound. Beside the 1:1 section are schematics delineating density zones in the designated portions of the section. In the top panel (part of the ClpA-bound end of ClpP), the sleeve of N-loop-associated density is in red contour; the contacting portion of ClpA is in green, and the ClpP barrel is in black. The blue bar marks the channel-blocking density at the ClpA-free (bottom) end of ClpP. Red arrows in both sections point to the sleeve. b, gray scale longitudinal central sections simulated from crystal structures of ClpP, band-limited to 12-Å resolution and 7-fold symmetrized. Left, structure for PDB 1tyf for residues 18–193, i.e. without any N-loops. Note the wide axial channel. Right, structure for PDB 1yg6 with (left) all seven N-loops, six up and 1 down, and (right) with only the six up N-loops (Nl = N-loop). d, 1yg6 structure, as docked into the cryo-EM density map of the 1:1 complex. The six up N-loops at the ClpA-bound end are in red, and the one down N-loop is in magenta (magenta arrowhead). The partially visualized N-loops at the ClpA-free end are in magenta. c, gray scale longitudinal central sections through two models for the 1:1 complex. The top half of both models is from PDB 1yg6 with six up N-loops. The bottom halves were modified from 1yg6 in two different ways by allowing rigid body rotation of the N-loops around residues 17 and 18. They give examples of how N-loops may be packed so as to close the channel (blue bars).

When gray scale sections through crystal structures for the barrel are viewed at similar resolution (e.g.1tyf in Fig. 3b), a wider channel, ∼25 Å across, is seen; elsewhere, there is good agreement with the cryo-EM density maps. It follows that the channel-blocking density at the ClpA-free end of the 1:1 complex and the density sleeve surrounding the channel at ClpA-bound end are both contributed by the N-terminal regions (residues 1–17), distributed differently. At the ClpA-free end, this density forms a bolus, ∼30 Å thick (blue bar in Fig. 3a and blue contour in the bottom enlarged box), that protrudes only slightly beyond the apical surface of the barrel and into the internal cavity.

Modeling the Near Axial Densities in Terms of Distributions of N-terminal Loops

In most ClpP crystal structures, the N-terminal regions are visualized incompletely if at all (11, 20–23), implying that their conformations are variable. In the structure of E. coli ClpP by Bewley et al. (22) (Protein Data Bank (PDB) code 1yg6), which was solved without applying 7-fold symmetry, different structures were observed at the two ends of the tetradecamer. At one end, six of the seven N-terminal regions were seen to extend distally in a β-hairpin (N-loop) conformation, whose tip protrudes 10–15 Å beyond the apical surface (Fig. 3d, red loops); this was called the up conformation. The seventh N-loop had the same β-hairpin fold but lay in a different, nonprotruding, position (Fig. 3d, magenta arrowhead); this was called the down conformation. Because this N-loop and side chains from another one lay across the channel, this conformation was proposed to represent a closed state of the channel. At the other end of ClpP, all seven N-loops, albeit incompletely visualized, appeared to be in down conformations (Fig. 3d, magenta loops), and were taken to represent an open state of the channel. However, our reconstruction implies that the open and closed ends should be assigned in the opposite manner, i.e. the channel is open when the loops are up.

To allow closer comparison with the cryo-EM map, we calculated 7-fold-symmetrized representations of this crystal structure of ClpP and band-limited them to 12-Å resolution (Fig. 3b, 1yg6). The periaxial density at the up end matched well with the ClpP ring at the ClpA-bound end of the EM map in terms of the bore of the axial channel (∼12 Å), and the surrounding sleeve of density, although the latter feature is more strongly contrasted in the simulation (Fig. 3b, 1yg6, red arrows). Excluding chain C (the single loop in down conformation) makes little difference to the simulation (Fig. 3b, cf. 7Nls and 6Nls), and it cannot be determined whether the cryo-EM density map conveys one (or a few) N-loops in down conformations.

At the other end of the simulated section, the channel appears wider (Fig. 3b, 1yg6), and this feature is not consistent with the cryo-EM density at either end of the complex and, in particular, with the blocked channel at the ClpA-free end (cf. Fig. 3a, blue bar, versus Fig. 3b, bottom halves). However, the simulation accounts for only 34% of the N-loop density that should be present (41 of 119 amino acids). The most straightforward interpretation of the cryo-EM density in this region is that it represents distributions of N-loops in conformations that are somewhat variable (and thus not seen in the crystal structure), but definitely different from the up conformation that prevails at the other end of the complex. Our density map does not allow these conformations to be specified, but we have modeled two possible distributions of nonoverlapping N-loops that retain the β-hairpin motif but pivot variably about a hinge at residue 18 and adequately reproduce the cryo-EM density (Fig. 3c, models 1 and 2, blue bars).

We followed the same procedure with two other crystal structures, from E. coli (PDB 2fzs) (21) and Saccharomyces pneumoniae (PDB 1y7o) (20), which show seven N-loops in an up conformation but are missing some residues at the tip of the hairpin. Again, when gray scale sections are compared, the simulations reproduce a channel very similar to the one seen by cryo-EM at the ClpA-bound end (supplemental Fig. 2). They differ slightly in the density surrounding the channel; in the case of 2fzs, these features are shorter, consistent with the absence of the loop tips in this structure.

Localization of ClpA Interaction Sites on the ClpP Apical Surface

As described above, the 7-fold-symmetrized reconstructions show a ring of ClpA-derived density on the apical surface of ClpP (Fig. 1, b and d). Because ClpA is a hexamer, these rings are almost annular (supplemental Fig. 3); nevertheless, they show a slight 7-fold modulation, and we take their maxima to mark positions on ClpP where ClpA can bind. To localize and accentuate these maxima, we generated a difference map between the 2:1 reconstruction and the ClpP crystal structure band-limited to 12 Å resolution and sharpened its edges by surface rendering; in this image, discrete difference densities are seen around the ClpP periphery (green densities in Fig. 4). When the difference densities, the cryo-EM map and the docked ClpP crystal structure are superimposed (Fig. 4, a and b), they depict ClpA as binding at the interface between two ClpP monomers. This interaction has been proposed, on other grounds, to be mediated by a ClpA loop containing a conserved “IGL” motif (31, 40). This loop was not seen in the crystal structure of ClpA (32) and was therefore assumed to be disordered. We infer that it becomes structured upon binding to ClpP and surmise that its initial plasticity may allow more than one interaction on the same complex, despite the symmetry mismatch, as proposed for the related ClpX chaperone (41). The binding site on ClpP involves a small cavity between the adjacent subunits (Fig. 4c). The residues at this site include Phe-112, which was shown by mutagenesis to be an important ClpP residue for ClpA interaction (22).

DISCUSSION

Allosteric Mechanism of Pore Opening

We conclude that ClpA binds to ClpP via its IGL motif(s) at a peripheral site on the ClpP apical surface, and this interaction elicits a conformational change in the axial region of the same ClpP ring, opening a channel through it. In this transition, most or all of the seven N-loops are displaced from their original positions, where they block the channel (Fig. 2b, red arrow and orange oval, and Fig. 3a, blue bar). When crystal structures that depict configurations of N-loops, most or all in up conformations, are matched with ClpA-bound ClpP rings in cryo-EM reconstructions, which we take to represent the open state of the gated pore, - there is good agreement (cf. Fig. 3, a and b; see also supplemental Fig. 2). We infer, therefore, that this part of these crystal structures also represents the open state of the gated pore or conformations close to it.

The channel-blocking density seen at the ClpA-free end of the 1:1 complex indicates that in solution and in the absence of ClpA or any other “activator,” the pore is closed. None of the crystal structures shows the axial channel as fully blocked, but if the incomplete N-loops at the down end of the 1yg6 structure were to be completed, the channel could be blocked, as seen in the cryo-EM reconstruction and as modeled in Fig. 3c. To account for the open-like conformations of most of the ClpP rings visualized in crystal structures, we suppose that crystal contacts between ClpP barrels may exert forces on each other that mimic the allosteric interaction with ClpA, causing the channel to open. We note also that the up conformation of the N-loop in some subunits is stabilized by lattice contacts with adjacent molecules (22).

Even in cases where some (faint) density is seen close to or in the channel, it may not offer much resistance to the entry of forcefully translocated substrates unless the motifs involved are firmly clamped in place; i.e. such density may represent the molecular equivalent of a “beaded curtain” across a doorway that may be easily brushed aside. We suggest that the “sleeve” densities around the open channel (contributed by residues 11–17 of the N-loops) are similarly movable, so as to allow the entry of substrates wider than a single extended polypeptide chain (9). In this context, we propose that the effective diameter of the open channel is a somewhat variable quantity, adaptable from a minimum of the 12 Å seen in the cryo-EM and crystal structures to a maximum of 25 Å, as delimited by the core domains (Fig. 3b, 1tyf panel).

Secondary, Near Axial, Interaction between ClpA and ClpP

In our cryo-EM reconstructions, the ClpA peripheral interaction between two ClpP monomers is the only direct contact we could observe. Nevertheless, major changes in the conformations of the N-loops, ∼25 Å away, accompany the attachment of ClpA. It follows that ClpA binding is somehow sensed by ClpP and communicated to the axial region occupied by the N-loops. Another factor that could favor the open conformation for the N-terminal loops would be an axial interaction with D2 the ClpP-proximal AAA+ domains of ClpA (41). For ClpX, it was shown by cross-linking experiments that the N-loops interact with a pore loop of ClpX (42). Mutations in residues at the tip of the N-loop also affect the stability of ClpAP and ClpXP complexes (22). Although our density maps of ClpP do not point to strong axial contact between ClpP and ClpA, they do not rule out some such interaction, particularly if it were to be dynamic and to involve only one or a few N-loops at a time.

Gate Opening in Other Proteases

Bipartite proteases consisting of a regulatory complex attached to a peptidase, as in ClpAP, are quite widespread (3). Among other shared properties, they employ gating mechanisms that restrict access to the proteolytic chamber. A conserved mode of interaction in E. coli HslUV and the 26 S or 20 S/11 S proteasome complexes involves the insertion of C termini of regulatory protein subunits between adjacent subunits of the peptidase. It resembles the peripheral interaction of ClpA between two ClpP monomers except that ClpA interacts through a tripeptide part of a flexible loop.

The 11 S activator induces channel opening on the 20 S proteasome by a second axial interaction via an insertion peptide that contacts the 20 S N-terminal loops (43, 44). On the other hand, gate opening by the archeal ATPase PAN can be mimicked simply by the 20 S particle binding an octapeptide corresponding to the PAN C-terminal region, an observation that excludes the requirement for any axial interaction with the PAN ATPase domain (45, 46). Additionally, PAN binding which, as in ClpAP, features a 6:7 symmetry mismatch causes a small rigid-body rotation of each 20 S α-subunit, whereas 11 S binding leaves them nearly unchanged.

It appears, therefore, that the interaction between peptidase and regulatory complex has mechanistically similar elements in ClpAP and the proteasome, although the details of execution may differ. Such underlying similarity correlates well with our observation that the main interaction between ClpA and ClpP takes place at the periphery. A second, axial, interaction helps to stabilize the complex and may be needed to usher substrates into the proteolytic chamber.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Programs of NIAMS and NCI of the National Institutes of Health.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1–3.

- cryo-EM

- cryoelectron microscopy

- EM

- electron microscopy

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank

- PAN

- proteasome-activating nucleotidase.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wickner S., Maurizi M. R., Gottesman S. (1999) Science 286, 1888–1893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Striebel F., Kress W., Weber-Ban E. (2009) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 19, 209–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gottesman S. (2003) Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 19, 565–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker T. A., Sauer R. T. (2006) Trends Biochem. Sci. 31, 647–653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Snider J., Houry W. A. (2008) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 36, 72–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erzberger J. P., Berger J. M. (2006) Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 35, 93–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flynn J. M., Neher S. B., Kim Y. I., Sauer R. T., Baker T. A. (2003) Mol. Cell 11, 671–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mogk A., Dougan D., Weibezahn J., Schlieker C., Turgay K., Bukau B. (2004) J. Struct. Biol. 146, 90–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burton R. E., Siddiqui S. M., Kim Y. I., Baker T. A., Sauer R. T. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 3092–3100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kessel M., Maurizi M. R., Kim B., Kocsis E., Trus B. L., Singh S. K., Steven A. C. (1995) J. Mol. Biol. 250, 587–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J., Hartling J. A., Flanagan J. M. (1997) Cell 91, 447–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thompson M. W., Singh S. K., Maurizi M. R. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 18209–18215 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grimaud R., Kessel M., Beuron F., Steven A. C., Maurizi M. R. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 12476–12481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weber-Ban E. U., Reid B. G., Miranker A. D., Horwich A. L. (1999) Nature 401, 90–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh S. K., Grimaud R., Hoskins J. R., Wickner S., Maurizi M. R. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 8898–8903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishikawa T., Beuron F., Kessel M., Wickner S., Maurizi M. R., Steven A. C. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 4328–4333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi K. H., Licht S. (2005) Biochemistry 44, 13921–13931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jennings L. D., Lun D. S., Médard M., Licht S. (2008) Biochemistry 47, 11536–11546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu A. Y., Houry W. A. (2007) FEBS Lett. 581, 3749–3757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gribun A., Kimber M. S., Ching R., Sprangers R., Fiebig K. M., Houry W. A. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 16185–16196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Szyk A., Maurizi M. R. (2006) J. Struct. Biol. 156, 165–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bewley M. C., Graziano V., Griffin K., Flanagan J. M. (2006) J. Struct. Biol. 153, 113–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kang S. G., Maurizi M. R., Thompson M., Mueser T., Ahvazi B. (2004) J. Struct. Biol. 148, 338–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maurizi M. R., Clark W. P., Kim S. H., Gottesman S. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265, 12546–12552 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jennings L. D., Bohon J., Chance M. R., Licht S. (2008) Biochemistry 47, 11031–11040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bewley M. C., Graziano V., Griffin K., Flanagan J. M. (2009) J. Struct. Biol. 165, 118–125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thompson M. W., Maurizi M. R. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 18201–18208 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brötz-Oesterhelt H., Beyer D., Kroll H. P., Endermann R., Ladel C., Schroeder W., Hinzen B., Raddatz S., Paulsen H., Henninger K., Bandow J. E., Sahl H. G., Labischinski H. (2005) Nat. Med. 11, 1082–1087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beuron F., Maurizi M. R., Belnap D. M., Kocsis E., Booy F. P., Kessel M., Steven A. C. (1998) J. Struct. Biol. 123, 248–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maurizi M. R., Thompson M. W., Singh S. K., Kim S. H. (1994) Methods Enzymol. 244, 314–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh S. K., Rozycki J., Ortega J., Ishikawa T., Lo J., Steven A. C., Maurizi M. R. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 29420–29429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guo F., Maurizi M. R., Esser L., Xia D. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 46743–46752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heymann J. B., Belnap D. M. (2007) J. Struct. Biol. 157, 3–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frank J., Radermacher M., Penczek P., Zhu J., Li Y., Ladjadj M., Leith A. (1996) J. Struct. Biol. 116, 190–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adams P., Kandiah E., Effantin G., Steven A. C., Ehrenfeld E. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 22012–22021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Effantin G., Rosenzweig R., Glickman M. H., Steven A. C. (2009) J. Mol. Biol. 386, 1204–1211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hierro A., Rojas A. L., Rojas R., Murthy N., Effantin G., Kajava A. V., Steven A. C., Bonifacino J. S., Hurley J. H. (2007) Nature 449, 1063–1067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pettersen E. F., Goddard T. D., Huang C. C., Couch G. S., Greenblatt D. M., Meng E. C., Ferrin T. E. (2004) J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ludtke S. J., Baldwin P. R., Chiu W. (1999) J. Struct. Biol. 128, 82–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim Y. I., Levchenko I., Fraczkowska K., Woodruff R. V., Sauer R. T., Baker T. A. (2001) Nat. Struct. Biol. 8, 230–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Effantin G., Ishikawa T., De Donatis G., Maurizi M. R., Steven A. C. (2010) Structure, in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martin A., Baker T. A., Sauer R. T. (2007) Mol. Cell 27, 41–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Förster A., Masters E. I., Whitby F. G., Robinson H., Hill C. P. (2005) Mol. Cell 18, 589–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Förster A., Whitby F. G., Hill C. P. (2003) EMBO J. 22, 4356–4364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith D. M., Chang S. C., Park S., Finley D., Cheng Y., Goldberg A. L. (2007) Mol. Cell 27, 731–744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rabl J., Smith D. M., Yu Y., Chang S. C., Goldberg A. L., Cheng Y. (2008) Mol. Cell 30, 360–368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.