Abstract

Mutations in the Rhodopsin (Rho) gene can lead to autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa (RP) in humans. Transgenic mouse models with mutations in Rho have been developed to study the disease. However, it is difficult to know the source of the photoreceptor (PR) degeneration in these transgenic models because overexpression of wild type (WT) Rho alone can lead to PR degeneration. Here, we report two chemically mutagenized mouse models carrying point mutations in Rho (Tvrm1 with an Y102H mutation and Tvrm4 with an I307N mutation). Both mutants express normal levels of rhodopsin that localize to the PR outer segments and do not exhibit PR degeneration when raised in ambient mouse room lighting; however, severe PR degeneration is observed after short exposures to bright light. Both mutations also cause a delay in recovery following bleaching. This defect might be due to a slower rate of chromophore binding by the mutant opsins compared with the WT form, and an increased rate of transducin activation by the unbound mutant opsins, which leads to a constitutive activation of the phototransduction cascade as revealed by in vitro biochemical assays. The mutant-free opsins produced by the respective mutant Rho genes appear to be more toxic to PRs, as Tvrm1 and Tvrm4 mutants lacking the 11-cis chromophore degenerate faster than mice expressing WT opsin that also lack the chromophore. Because of their phenotypic similarity to humans with B1 Rho mutations, these mutants will be important tools in examining mechanisms underlying Rho-induced RP and for testing therapeutic strategies.

Keywords: Neurodegeneration, Photoreceptors, Phototransduction, Retinoid, Rho, Rhodopsin, Light-induced Degeneration, Retinitis Pigmentosa

Introduction

Rhodopsin is a light sensitive G-protein-coupled receptor composed of a membrane-bound opsin, encoded by the rhodopsin gene (Rho), and a covalently bound, light-sensitive chromophore, 11-cis-retinal. Upon light exposure, 11-cis-retinal is isomerized to all-trans-retinal, which induces a conformational change in rhodopsin to yield its active form, metarhodopsin II (R*).2 R* is deactivated via phosphorylation by rhodopsin kinase and binding to arrestin. In parallel, all-trans-retinal is released from R* and recycled through the visual cycle, to form 11-cis-retinal, which regenerates rhodopsin in the rod outer segment. The release of chromophore from R* can also lead to high levels of free opsin in the retina. Free opsin can activate the phototransduction cascade, albeit at a lower rate than R*, and can potentially lead to constitutive activation of transduction after it is phosphorylated and forms a complex with arrestin (1, 2), a phenomena associated with photoreceptor degeneration (1).

The maintenance of rod photoreceptors is critically dependent on normal levels of rhodopsin. Rod degeneration is observed in Rho−/− mice (3–5) and the human disorder retinitis pigmentosa (RP) caused by Rho mutations is characterized by progressive rod degeneration (6). More than 100 point mutations in rhodopsin collectively account for ∼25% of autosomal dominant RP as well as some forms of autosomal recessive RP (7, 8). These observations have spurred the development of transgenic lines expressing comparable rhodopsin point mutations (9–13). Although these models are a valuable resource, rod degeneration is also observed in mice overexpressing wild type (WT) rhodopsin (14). It is, therefore, difficult to know with certainty whether rod degeneration observed in transgenic lines reflects the effects of the introduction of rhodopsin point mutations or the overexpression of rhodopsin.

Phenotypically, mutations in Rho are divided into two classes (8, 15). Class A mutations cause rapid rod degeneration, leading to early onset night blindness in patients (15). Patients with class B mutations display a slower disease progression, and may be further subdivided into class B1 and B2 (15), differentiated by whether rod degeneration is focal (class B1) or panretinal (class B2). The class B1 patients also exhibit impaired deactivation of phototransduction after exposure to high intensity light flashes (15, 16).

Despite the importance of Rho mutations in human RP, the different classes of disease causing mutations and intense efforts to identify useful models of retinal disease in mice (17), only two models expressing alleles of Rho mutations under endogenous control have been identified. The Noerg1 mouse model harbors a C110Y point mutation that results in early onset and rapidly progressing rod degeneration (18). The T4R canine model develops a phenotype that closely resembles RP patients with class B1 Rho mutations (19). From this model, we have learned that light exposure plays a significant role in accelerating the disease phenotype (16). An allelic series of models with the different rhodopsin mutations implicated in human disease would be extremely useful in gaining insights into the many rhodopsin residues that are required for rhodopsin signaling or are modified post-translationally to modulate its function.

In this study, we report two new mouse models identified through screening of cohorts of chemically mutagenized mice by indirect ophthalmoscopy in the Translational Vision Research Models (TVRM) program sited at The Jackson Laboratory. The mice carry either the Y102H (Tvrm1) or I307N (Tvrm4) point mutations in the Rho gene. Under standard housing conditions, neither model develops significant rod degeneration. Interestingly, however, in both Tvrm1 and Tvrm4 mutants, even brief exposure to high intensity light leads to rapid rod degeneration, providing a phenotypic link to humans with class B1 Rho mutations. These light-inducible Rho models will be important not only for elucidating the functional domains within rhodopsin, but also for examining the mechanisms underlying the pathological changes observed and for testing therapeutic strategies to delay or prevent visual impairment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

All procedures used in animal experiments were approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the institutions involved and were in accordance with the procedures of the Association of Research for Vision and Ophthalmology. Tvrm1 and Tvrm4 mice were identified in cohorts of mice chemically mutagenized by the Neuroscience Mutagenesis Facility or the embryonic stem cell mutagenesis program of Dr. John Schimenti. For Tvrm1, male C57BL/6J (B6) mice were mutagenized with ethylnitrosourea administered in 3 weekly injections of 80 mg/kg by the Neuroscience Mutagenesis Facility program. G3 offspring, generated using a three generation backcross mating scheme (20), which were previously screened for neurological phenotypes, were re-screened by indirect ophthalmoscopy in the TVRM program. Tvrm4, generated by chemical mutagenesis of F1 hybrid 129/SvJae × C57BL/6J embryonic stem cells and a subsequent two generation backcross mating scheme (21), was moved onto the B6 background for a minimum of 5 backcross generations, the point at which ∼3.75% of unlinked genomic regions are from the 129 strain. Rd12 mice (MGI 005379) were acquired from the Eye Mutant Resource, The Jackson Laboratory. A.B6-Tyr+ and C3A.BLiA-Pde6b〈+〉/J (i.e. C3H mice that do not carry the rd1 mutation) were used for Tvrm1 and Tvrm4 mapping crosses, respectively. The F1 progeny were backcrossed to the WT parental strain and the resultant backcross progeny were used for mapping purposes. All mice were bred and maintained under standard conditions in the Research Animal Facility at The Jackson Laboratory with a 12:12 h dark:light cycle (0–35 lux, and once a week the mice were exposed to 440 lux during box changes).

Mapping

Mice generated from the backcrosses were phenotyped by indirect ophthalmoscopy ∼24 h following light exposure to 12,000 lux for 5 min. DNA was prepared from tail snips using proteinase K digestion and isopropyl alcohol extraction. DNA isolated from 252 Tvrm1 and 150 Tvrm4 backcross progeny were genotyped with microsatellite markers to develop fine structure maps of the regions encompassing these mutations.

Sequencing

Total RNA was isolated from whole eyes of Tvrm1, Tvrm4, C57BL/6J, and 129/J mice using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen) per the manufacturer's protocol. Total RNA was treated with RNase-free DNase I (Ambion) and quantified with a NanoDrop (ND-1000) spectrophotometer. RNA quality was evaluated using an Agilent Technologies 2100 Bioanalyzer. cDNA was made using the Retroscript kit (Ambion). Two overlapping primer sets were used to amplify and sequence the entire coding region of the rhodopsin gene, amino-terminal portion: Rho-F1, GTC AGT GGC TGA GCT CGC CAA GCA, and Rho-R1, CAT GCC CTC AGG GAT GTA CCT GGA; carboxyl-terminal portion: Rho-F2, TGG TGG TCT GCA AGC CGA TGA GCA, and Rho-R2, GGA GCC TGC ATG ACC TCA TCC CAA). Reverse transcription-PCR was done using eye cDNA in a 24-μl PCR containing 1× PCR buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 50 mm KCl), 250 μm each of dATP, dCTP, dTTP, 0.2 μm forward and reverse primer, 1.5 mm MgCl2, and 0.6 units of Taq polymerase.

PCR products were electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel and visualized using ethidium bromide staining. DNA fragments were sequenced on an Applied Biosystems 3730XL Sequencer (using a 50-cm array and POP7 polymer).

Genotyping

Allele-specific genotyping protocols were developed for both mutations. The following primer sets are used for PCR amplification of Tvrm1: Tvrm1, forward, AAC TTC CTC ACG CTC TAC GTC ACC GT; Tvrm1, reverse 1, ACA GCC TGT GGG CCC AAA GAC GAA GCA, and Tvrm1, reverse 2, CAA AGA AGC CCT CGA GAT TGT AGC CTG TGG GCC CAA AGA CGA GGT G; and Tvrm4, Tvrm4, forward, GGT CAT CTT CTT CCT GAT CTG CTG GC; Tvrm4, reverse 1, GCC CAG GCA CCT GCT TGT TCA ACA TCA, and Tvrm4, reverse 2, CTC CAC ACG CCC TGC CTC ATA CCA GGC ACC TGC TTG TTC AAC TTG T. The following PCR cycling programs were used: 94 °C for 1.5 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 45 s, and 72 °C for 1 min, and a final extension of 72 °C for 2 min. PCR products were electrophoresed on 4% Metaphor-agarose gels and visualized using ethidium bromide staining.

Ophthalmic Examination and Fundus Photography

Eyes of dark-adapted mice were dilated with one drop of 1% atropine and examined with an indirect ophthalmoscope with a 78 or 90 diopter aspheric lens. Fundus photographs were taken with a Kowa small animal fundus camera using a Volk superfield lens held 2 inches from the eye as previously described (22).

Bright Light Exposure Protocol

All animals, except for those used in mapping, were dark-adapted overnight, prior to exposure to 12,000 lux of light. The animals used for mapping were not dark adapted prior to exposure to bright light. The pupils of each mouse were dilated with 1% atropine and the animals were placed in cages lined with mirrors. The mirrored cages were placed in a box equipped with 4 fluorescent bulbs that delivered 12,000 lux of achromatic light to the bottom of the cages. Light exposure occurred between 9 a.m. and noon, and exposure times varied between 30 s and 5 min.

Histological and Immunohistological Analysis

Eyes were processed as previously described (23). Briefly, eyes were enucleated and fixed in cold acetic acid:methanol:phosphate-buffered saline (1:3:5) solution overnight, immediately following euthanasia. Paraffin-embedded eyes were cut into 6-μm thick sections and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for light microscopy. De-paraffinized sections were stained with anti-rhodopsin antibody (Leinco Technologies, 1:500, anti-mouse) and subsequently labeled with Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch, 1:200) or with anti-ezrin (Santa Cruz, 1:100, anti-goat) and subsequently labeled with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody (Molecular Probes, 1:200) and visualized by fluorescence microscopy. For detection of cells undergoing apoptosis, terminal uridine deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) was used on paraffin sections according to the manufacturer's protocol (ApopTag TUNEL staining kit, Chemicon).

Western Blot Analysis

Total protein from WT, RhoTvrm1, and RhoTvrm4 retinas was isolated by standard methods in RIPA buffer (1% Nonidet P-40, 0.1% SDS, and 0.5% sodium deoxycholate in phosphate-buffered saline) containing a protease inhibitor (Roche Applied Science). Twenty μg of total protein was electrophoresed on a 12% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was stained with anti-rhodopsin (Sigma) and anti-β-actin (Sigma) for loading control. All bands were incubated with appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies followed by the ECL detection system (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). The Western blots were imaged using a LAS-1000 (Fuji) and the intensity of each band was quantified using ImageGauge (Fuji).

Electroretinography

After overnight dark adaptation, mice were anesthetized with ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylazine (16 mg/kg). Eye drops were used to anesthetize the cornea (1% proparacaine HCl) and to dilate pupils (1% tropicamide, 2.5% phenylephrine HCl, 1% cyclopentolate HCl). Mice remained on a temperature-regulated heating pad throughout the recording session. ERGs were recorded with a stainless steel loop that made contact with the corneal surface through a thin layer of 0.7% methylcellulose. Needle electrodes placed in the cheek and the tail served as reference and ground leads, respectively. Responses were differentially amplified (0.05–1500 Hz), averaged, and stored using a signal averaging system (UTAS E-3000; LKC Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD).

To examine different aspects of retinal function, three types of recording sessions were conducted. The first examined standard ERG intensity-response functions (23). Dark-adapted responses were recorded first using flash intensity that ranged from −3.6 to 2.1 log candles s/m2. Stimuli were presented in order of increasing intensity, and the number of successive responses averaged together decreased from 20 for low-intensity flashes to 2 for the highest intensity stimuli. The duration of the inter-stimulus interval (ISI) increased from 4 s for low-intensity flashes to 90 s for the highest intensity stimuli. A steady rod-desensitizing adapting field (1.5 log cd/m2) was then presented within the Ganzfeld bowl. After allowing a 7-min period of light adaptation, cone ERGs were recorded to flashes superimposed on an adapting field. Flash intensity ranged from −0.8 to 1.9 log cd s/m2, and responses to 100 flashes presented at 2.1 Hz were averaged at each intensity level.

The second recording session was used to measure rod photoreceptor response recovery by varying the ISI between pairs of high-intensity (2.1 log cd s/m2) flashes that were presented in darkness (24). Six trials were run for each mouse, in which the ISI between the first (conditioning) flash and the second (probe) flash was decreased from 64 to 2 s in octave steps. Mice were dark-adapted between stimulus pairs for 5 min.

The third recording session was used to monitor bleaching recovery, using the protocol developed by Kim et al. (25). After a dark-adapted (baseline) response was measured, mice were exposed for 3 min to a high intensity (500 cd/m2) bleaching field. After the bleaching field was extinguished, an initial response was measured at 10 s and responses were then measured at 5-min intervals thereafter.

The amplitude of the a-wave was measured 8 ms after flash onset from the prestimulus baseline. Amplitude of the b-wave was measured from the a-wave trough to the peak of the b-wave or, if no a-wave was present, from the prestimulus baseline.

Retinoid Analysis

Whole mouse eyes were grouped according to treatment and genotype (12 per group), but the identities of groups were masked during analysis. Retinoids were extracted from whole mouse eyes in pools of three eyes (four separate samples for each genotype and condition) under dim red light as described (26). Briefly, the mouse eyes were placed in a solution of 0.43 ml of MOPS buffer containing 50 mm MOPS, pH 6.8, 40 mm NH2OH, and 1 ml of methanol and homogenized with a Tekmar Tissumizer homogenizer for 20–30 s. Each sample was incubated at room temperature for 30 min to form the oximes. After the addition of 0.57 ml of 50 mm MOPS, pH 6.8, 40 mm NH2OH, the sample was extracted with 2 ml of dichloromethane by vortexing and subsequent centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. The organic phase was collected and the aqueous phase was extracted three more times with dichloromethane. The extracts were pooled and dried under an argon stream. The samples were dissolved with 300 μl of hexane:dioxane (100:6, v/v) and filtered through an Acrodisc 0.45-μm syringe filter.

Retinoid standards, retinyl palmitate, all-trans-retinal, and all-trans-retinol were purchased from Sigma and 11-cis-retinal was provided from Dr. Rosalie K. Crouch (Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC) and the National Eye Institute of the National Institutes of Health. Oxime standards were synthesized as described (27). The retinoid concentrations were determined by the absorbance spectra and extinction coefficients in hexane (28) (in units of m−1 cm−1): retinyl palmitate ϵ = 49,256 at 326 nm; all-trans-retinal ϵ = 47,996 at 368 nm; 11-cis-retinal ϵ = 26,355 at 362 nm; all-trans-retinal oxime ϵ = 55,500 at 357 nm; 11-cis-retinal oxime ϵ = 35,900 at 347 nm; and all-trans-retinol ϵ = 51,800 at 325 nm.

The samples were analyzed with a Shimadzu dual-pump (LC-20AD) gradient HPLC system and a system of hexane (solvent A) versus 1,4-dioxane (solvent B) with a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min. A 100-μl volume of each sample was injected into a normal phase column (Supelco, Ascentis Si, 15 cm × 4.6 mm, 3 μm) pre-equilibrated with hexane by an automatic sampler (SIL-20A, Shimadzu). Retinoids were eluted with a linear gradient of 0–25% dioxane in 20 min. Retinyl ester and retinol were monitored by the absorbance at 325 nm using a UV-visual photodiode array detector (SPD-M20A, Shimadzu) and at 325 nm excitation/475 nm emission (28) using a spectroflurometric detector (RF-10AXL, Shimadzu) both interfaced to a computer (LCsolution software; Shimadzu). 11-cis-Retinal, all-trans-retinal, 11-cis-retinal oxime and all-trans-retinal oxime were monitored by the absorbance at 362, 368, and 350 nm, respectively, using the UV-visible photodiode array detector. The area of the retinoid peak was calculated and compared with the area versus mass curve for the standard. Amounts were determined from the integrated peaks by comparison to the standard curves, and results for each group were averaged.

In Vitro DNA Mutagenesis, Expression, and Spectrophotometry of Opsins

All opsin variants were expressed using modified forms of a plasmid containing a synthetic bovine opsin gene cDNA in a pMT3-based vector (29, 30). The use of the bovine gene facilitates mutagenesis as multiple unique restriction sites are available, and direct comparison to a large body of work on previous rhodopsin mutations is possible. Mutations were introduced using the QuikChange® mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). Expression in COS-1 cells, membrane isolation, reconstitution with 11-cis-retinal, and protein purification using 1D4 antibody affinity chromatography were carried out as described previously (31, 32). UV-visible absorption spectra of purified receptors were recorded with the use of a Varian Cary50 spectrophotometer modified for dark room use. All readings were of 1.0-cm path length samples taken at 23–25 °C.

Determination of Metarhodopsin II Lifetimes

The rate of MII decay was measured in a manner similar to that previously published (32), with small modifications. Specifically, the decay rate was determined utilizing the fact that 11-cis-retinal binds to opsin at a faster rate than MII decays. First, the spectrum of the purified pigment in 2 mm sodium phosphate, pH 6.7, containing 0.1% (w/v) dodecyl maltoside (Anatrace, Maumee, OH) was recorded in the dark. Second, ∼2 eq of 11-cis-retinal were added to the sample, and the resulting spectrum taken. The sample was subjected to light from a 300-watt tungsten bulb passed through a 455-nm long-pass filter for 1 s to selectively activate rhodopsin in the sample, without photoisomerizing the excess 11-cis-retinal. Absorbance at 500 nm was measured post-flash until no further increase in absorbance was detected. Half-lives for the reactions were determined as previously reported (32), averaged over at least four trials, and plotted. Error bars represent the S.D. To prevent denaturation of opsin in detergent, these experiments were performed on proteins that had N2C and D282C mutations of rhodopsin that have been shown to stabilize WT rhodopsin without affecting its functional properties (33).

Retinal Binding to Opsins

Rhodopsin formation was monitored with UV-visible absorbance spectrophotometry as an increase in absorbance at 500 nm over time after addition of a 3-fold molar excess of 11-cis-retinal. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) and fit to the equation: Y = Y0 + A1*(1 − exp(−k1 × X)) + A2*(1 − exp(−k2*X)).

COS Cell Membrane Preparation

Membranes were prepared as previously described (31). In brief, 72 h after transfection with DNA, COS cells from five 150-mm culture plates were harvested with a cell scraper and washed with 10 mm sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, containing 150 mm NaCl. The cells were then hypotonically lysed with 15 ml of 10 mm Tris, pH 7.4, containing a saturating amount of phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. The cells were passed through a 25-gauge needle four times and membranes were separated by layering the lysate onto 20 ml of 37% (w/v) sucrose in 10 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm CaCl2, 0.1 mm EDTA, and centrifugation at 33,000 × g. Membranes were collected from the interface with a transfer pipette, diluted 10-fold with lysis buffer, and membranes were collected via centrifugation at 100,000 × g. The membrane pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm each of MgCl2 and CaCl2, and 0.1 mm EDTA. Rhodopsin concentration was estimated from immunoblots using the rhodopsin carboxyl-terminal 1D4 monoclonal antibody.

Transducin Activation Assays

The ability of receptors to catalyze the exchange of GDP for radiolabeled [35S]GTPγS in transducin was examined using a filter binding assay as previously described (32), with the following exceptions. Time points were taken every minute, and light was introduced at t = 6 min 10 s. All assays were performed with rhodopsin in COS cell membranes diluted 10-fold with transducin assay buffer (10 mm Bistris propane, pH 6.7, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 1 mm CaCl2, 0.1 mm EDTA). Reaction mixtures contained transducin assay buffer supplemented with 1 mm dithiothreitol, 2 μm transducin, and 3 μm [35S]GTPγS (5 Ci/mmol). Reactions were initiated by addition of GTPγS. For light-dependent reactions, membranes were incubated with 100 μm 11-cis-retinal for at least 1 h on ice prior to use in assays. The final reaction volume was 150 μl, and 10-μl aliquots were withdrawn and assayed at the times indicated. Due to inherent opsin stability in membranes, the thermally stabilizing mutations N2C and D282C were not used in this assay. Assay temperature was maintained at 23–25 °C. Under these conditions, the reaction rate was directly proportional to the rhodopsin concentration. Although COS cell membranes have a different lipid composition than rod outer segments, this disadvantage is balanced by the benefit that hydroxylamine is not needed in these assays, thus avoiding activation of opsin by retinal oxime. Data were analyzed using Kaleidagraph (Synergy Software, Inc., Reading, PA).

RESULTS

Light-induced Degeneration of Photoreceptors in Tvrm4 and Tvrm1 Mouse Mutants Is Caused by Missense Mutations in Rho

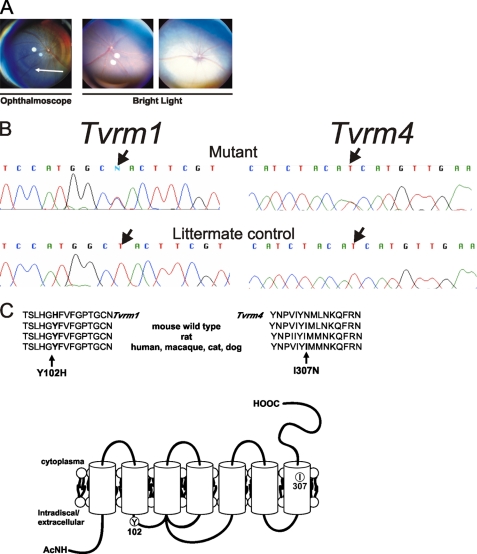

Abnormal fundus pigmentation was observed by indirect ophthalmoscopy in a family of G2 B6/129 hybrid mice generated by chemical mutagenesis of embryonic stem cells. In an outcross of affected Tvrm4 mice to WT B6 mice, 50% of F1 offspring were affected, indicating a dominant inheritance pattern. As multiple indirect ophthalmoscopic exposures were necessary to observe the phenotype, independent of the age of the mice, this suggested that the examinations were inducing the loss of photoreceptors adjacent to the optic disc (Fig. 1A, left).

FIGURE 1.

Light-induced degeneration of photoreceptors in Tvrm4 and Tvrm1 mutants are caused by missense mutations in the Rhodopsin gene (Rho). A, fundus photographs of Tvrm4 mutant mice and controls. After light exposure from indirect ophthalmoscopy (left), the central retina becomes hyperpigmented, indicating photoreceptor degeneration, shown by a white arrow. Within 24 h after exposure to bright light (center and right panels) the mutant retina becomes hyper-reflective (right), whereas the WT retina does not (center). B, schematic of the Rho sequences depicting the Tvrm4 and Tvrm1 mutations. Single base pair substitutions (arrow) were found and predicted to lead to a change of amino acid 307, isoleucine to asparagine (I307N) 102 in Tvrm4, and tyrosine to histidine (Y102H) in Tvrm1, n = 3 animals. C, the amino acid residues, Ile-307 and Tyr-102, are conserved among species. Protein sequences are from different species containing Ile-307 and Tyr-102 amino acid residues. The sites of mutations are indicated in the rhodopsin crystal structure (PDB coordinates 1U19) using the molecular modeling program UCSF Chimera.

The Tvrm4 mutant mice were outcrossed to C3A.BLiA-Pde6b〈+〉/J, and affected F1 mice were backcrossed to the C3A.BLiA-Pde6b〈+〉/J parental line, to generate a backcross population for mapping purposes. To standardize the phenotyping protocol, the backcrossed animals were exposed to 12,000 lux of light for 5 min, which in the mutants led to visible bleaching of the entire retina for 1 h following exposure (Fig. 1A, right panel). Retinas of WT mice remained unaffected by the light exposure (Fig. 1A, middle panel). The Tvrm4 mutation was mapped to chromosome 6 between D6Mit62a (115.7 Mb) and D6Jmp8 (120.3 Mb) (data not shown).

The rhodopsin gene (Rho) mapped within the critical region, located about 115.9 Mb. The light-dependent nature of the Tvrm4 phenotype suggested that Rho was an excellent candidate gene. Sequence comparisons of Rho cDNA from Tvrm4 mutant and WT mice revealed a single nucleotide change. The missense mutation was predicted to lead to a change of amino acid 307, isoleucine (ATC), to asparagine (AAC) (Fig. 1B). Ile-307 is located in the 7th transmembrane region of RHO and is conserved across species, including human, primate, cat, dog, and rat (Fig. 1C). The Tvrm4 mutation was introgressed onto the C57BL/6 (B6) background by sequential backcrossing to B6 for 5 to 7 generations to remove potential influences of a segregating B6/129 genetic background on the disease phenotype.

During the course of screening ethylnitrosourea-mutagenized G3 C57BL/6 mice, a litter of two mice with depigmented retinas was identified. This was the only litter of mice with a phenotype similar to Tvrm4 mutants observed in screening 10,000 G3s. Heritability testing of this mutation, named Tvrm1, indicated a dominant inheritance pattern, and similar to Tvrm4 mutants multiple examinations by indirect ophthalmoscopy were necessary to induce the disease phenotype. Heterozygous C57BL/6-Tvrm1 mice (hereafter referred to as Tvrm1) were outcrossed to A.B6-Tyr+ mice and affected F1 mutants were backcrossed to A.B6- Tyr+. Backcross progeny exposed to 12,000 lux of bright light were used to map the mutation to chromosome 6 between markers D6Jmp1 (115.5 Mb) and D6Jmp7 (119.3 Mb). A single base pair change was found in the Rho gene of Tvrm1 mutants. The missense mutation is predicted to lead to a change of amino acid 102, tyrosine (TAC), to histidine (CAC) (Fig. 1B). Tyr-102 is in the first extracellular loop of Rho and is also conserved among species (Fig. 1C).

Rho Mutants Raised in Ambient Light Do Not Exhibit Loss of Photoreceptor Cell Bodies or Changes in Photoreceptor Function

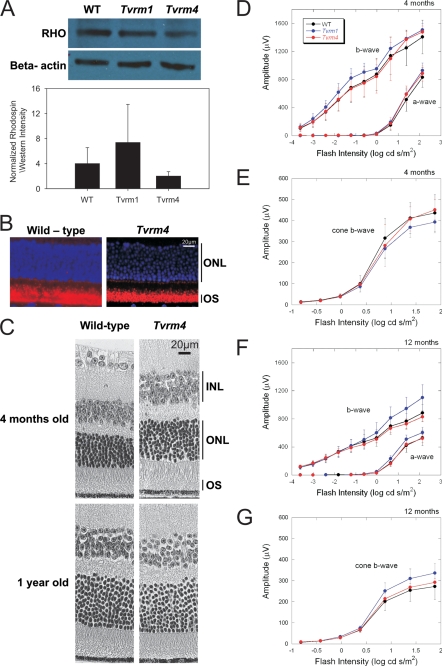

To determine whether the missense mutations identified affected either the level or localization of rhodopsin, Western analysis and immunohistochemical studies were carried out, respectively. No significant differences in the level of rhodopsin were noted at 6 months between heterozygous Tvrm4 mice (hereafter referred to as RhoTvrm4/+) and WT controls (Fig. 2A). Immunohistochemistry demonstrated that rhodopsin localized properly to the outer segments in the Tvrm4 retina (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

Photoreceptor degeneration does not occur in Tvrm4 and Tvrm1 Rho mutant mice raised in ambient light. A, Western analysis of rhodopsin levels in the retinas of WT and RhoTvrm4/+ mice. β-Actin is used as a loading control. Protein levels were quantified using ImageGauge. The rhodposin levels were normalized to the level of β-actin and are plotted as mean ± S.E. There were no significant differences between groups, one-way ANOVA, n = 3 mice. B, immunohistochemical analysis of rhodopsin in retinas of RhoTvrm4/+ mutant and WT animals raised in ambient light. Rhodopsin localization in the outer segments of Tvrm4 mutants (left) is not different from WT (right). Blue, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole staining; red, anti-rhodopsin staining, n = 3 mice. C, light microscopy of central retinas from aged animals. Photoreceptor nuclei of 4-month and 1-year-old RhoTvrm4/+ (right) animals raised in standard ambient mouse room light are preserved, comparable with wild-type littermates (left), n = 3 mice per group. D-G, intensity-response functions for ERGs obtained from WT mice and RhoTvrm1/+ and RhoTvrm4/+ mutants. ERGs were recorded at 4 (D and E) and 12 months (F and G) under dark-adapted (D and F) and light-adapted (E and G) conditions. Data points indicate the average ± S.E. for at least 5 mice. In comparison to WT littermates, there is no decrement in ERG amplitude in either RhoTvrm1/+ or RhoTvrm4/+ mice. INL, inner nuclear layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer; OS, outer segments of photoreceptors.

Unlike other models of retinal degeneration, the retinas of RhoTvrm4/+ mutant mice raised under standard mouse housing conditions were similar to those of WT controls. No loss of photoreceptor cell bodies was noted even in 1-year-old mutants. Outer segment lengths in 4-month-old mutants did not differ from WT. At 1 year, however, outer segments were slightly shorter in mutant mice compared with WT (Fig. 2C). A similar phenotypic picture was observed for heterozygous Tvrm1 mice (hereafter referred to as RhoTvrm1/+) mutants raised in ambient light. Rhodopsin levels, localization, and photoreceptor morphology of RhoTvrm1/+ mutants were comparable with that of RhoTvrm4/+ mutants and WT controls (data not shown).

To evaluate overall retinal function, ERGs were recorded to full-field stimulus flashes presented under dark-adapted conditions, to isolate rod-driven activity, or superimposed upon a steady adapting field, to monitor activity of the cone pathway. At both 4 (Fig. 2D) and 12 months (Fig. 2F) of age, there was no reduction in the amplitude of a- or b-waves recorded from RhoTvrm1/+ or RhoTvrm4/+ mice, as compared with those obtained from WT littermates. Because the leading edge of the dark-adapted ERG a-wave reflects the closure of cyclic nucleotide-gated channels along the rod photoreceptor (34), these results indicate that the normal complement of rod photoreceptors retained by RhoTvrm1/+ and RhoTvrm4/+ mice functions normally when stimulated by light flashes. Similar results were obtained for responses recorded under light-adapted conditions. In comparison to responses obtained from WT littermates, cone ERGs were not reduced in RhoTvrm1/+ or RhoTvrm4/+ mice at either of the ages tested (Fig. 2, E and G).

RhoTvrm1/+ Mutants Are More Vulnerable to Light than RhoTvrm4/+ Mutants

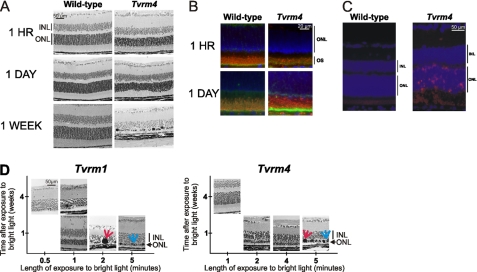

The time course over which light-induced changes developed in Tvrm4 mutant mice was examined by sacrificing RhoTvrm4/+ and WT mice at different times following a 5-min exposure to 12,000 lux of bright light. Fig. 3A presents a series of representative retinal cross-sections taken at different durations of time following light exposure. Within 1 h, the photoreceptor outer segments of RhoTvrm4/+, but not WT, mice appeared disorganized and some areas were devoid of outer segments, whereas others appeared to contain outer segment aggregates. In addition, the apical processes of retinal pigment epithelium that normally ensheath the outer segments appeared to extend further along the outer segments in RhoTvrm4/+ mice than in WT controls (Fig. 3B). Twenty-four hours following light exposure, it was not possible to discern the border between the outer and inner segments of the RhoTvrm4/+ retina, and both compartments were highly disorganized. The outer nuclear layer also appeared disorganized, although cell loss was not apparent. At this time, many RhoTvrm4/+ photoreceptors were TUNEL-positive indicating that they were undergoing apoptosis; TUNEL-positive staining was not detected in WT retinas (Fig. 3C). Thereafter, photoreceptor degeneration proceeded rapidly, with two or fewer layers of photoreceptor nuclei remaining at 1 week following light exposure. At this late stage of the degenerative process, multiple aggregates of chromatin and macrophages were also observed (Fig. 3, A and D).

FIGURE 3.

Photoreceptor degeneration in Tvrm1 and Tvrm4 mutants is rapidly induced by exposure to bright light. A, light microscopy and immunohistochemical staining of rhodopsin in the central retina from Tvrm4 mutant mice with 1- or 5-min exposures to bright light. Histological changes in the retinas of RhoTvrm4/+ mutants are observed within 1 h (top) following exposure to bright light. At 24 h (middle) following the exposure to bright light, the outer and inner segments of the RhoTvrm4/+ photoreceptors are disorganized. At 1 week (bottom) following exposure, the outer nuclear layer is reduced to two rows of cell bodies. B, rhodopsin (red), ezrin (yellow), and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue) staining of the retinas from WT and RhoTvrm4/+ animals 1 or 24 h after exposure to bright light. Photoreceptor outer segments are engulfed within the RPE cells of mutant eyes at 1 h after exposure to bright light, n = 2 animals. C, photoreceptors of Rho mutants are apoptotic 24 h following exposure to bright light. TUNEL staining of the retina was 24 h following bright light exposure, n = 3 animals. D, the Tvrm1 mutation makes the retina more vulnerable to light damage than the Tvrm4 mutation. Light microscopy of the central retina at different times following different durations of exposure to bright light. Red arrows indicate chromatin aggregates and blue arrows indicate macrophages, n = 3 mice for all groups except for RhoTvrm1/+, where n = 6.

To determine the duration of light exposure required to induce photoreceptor degeneration in RhoTvrm4/+ mutants, the duration of exposure to a 12,000 lux stimulus was varied and the retinas were harvested at varying times following exposure to a light stimulus. In 2 of 3 animals tested, a 2-min exposure was sufficient to induce photoreceptor degeneration, whereas a 1-min exposure produced no discernible changes (Fig. 3D).

The retinas of RhoTvrm1/+ animals were more sensitive to light-induced damage than the retinas of RhoTvrm4/+ animals. In RhoTvrm1/+ mice, photoreceptor degeneration was observed in 4 of 6 mice exposed to 12,000 lux for only 30 s (Fig. 3C).

Recovery from High Intensity Bleach Is Impaired in the Mutants, but the Deactivation of Phototransduction Is Normal

Our observations of extreme sensitivity to light-induced photoreceptor degeneration in RhoTvrm1/+ and RhoTvrm4/+ mice raised the possibility that these mutations interfered with phototransduction deactivation and/or bleaching recovery. We examined these possibilities using two ERG paradigms. To monitor phototransduction deactivation, we used a two-flash protocol in which a probe stimulus flash follows a conditioning by a specific ISI (35). By using high intensity stimuli that saturates the photoresponse, and a series of trials with different ISIs, the recovery of a-wave amplitude to the second probe flash monitors the deactivation process following the initial conditioning stimulus (36). This approach has been used to characterize the effect of other rhodopsin mutations on rod phototransduction deactivation (24, 37).

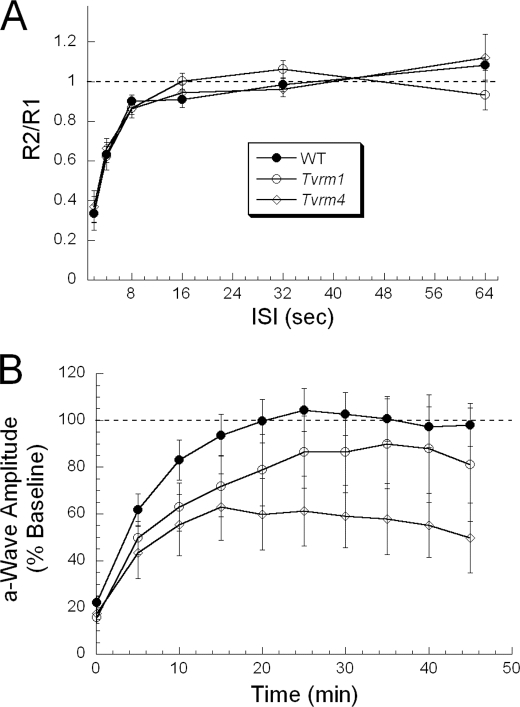

Fig. 4A summarizes the results obtained in RhoTvrm1/+ and RhoTvrm4/+ mice by plotting the ratio of the a-wave amplitude obtained to the probe flash (R2) to that obtained to the conditioning stimulus (R1). In comparison to results obtained from WT littermates, there was no difference in phototransduction deactivation in either RhoTvrm1/+ or RhoTvrm4/+ mice.

FIGURE 4.

Recovery from a high intensity level bleach is impaired in the mutants but activation and deactivation of phototransduction are normal. A, paired-flash analysis of phototransduction deactivation. In each trial, responses obtained to the probe flash (R2) are expressed relative to the response obtained to the conditioning flash (R1) and are plotted as a function of the duration of the ISI separating the conditioning and probe flashes. Data points indicate the mean ± S.E. for at least 5 mice. Recovery kinetics of the a-wave in RhoTvrm1/+ and RhoTvrm4/+ mice are comparable with those of WT littermates. B, bleaching recovery. Response recovery of a-wave amplitude following exposure to a high intensity bleaching light. For each individual mouse, responses were normalized to the dark-adapted pre-bleach baseline. Data points indicate mean ± S.E. for 19 WT, 9 RhoTvrm1/+, and 9 RhoTvrm4/+ mice. Compared with WT mice, recovery of the a-wave from bleaching light is slower and incomplete in RhoTvrm1/+ and RhoTvrm4/+ mice.

To monitor bleaching recovery, we used a standard protocol in which recovery toward a dark-adapted baseline was monitored at intervals following exposure to a bleaching stimulus (25). Fig. 4B summarizes the results obtained from WT, RhoTvrm1/+, and RhoTvrm4/+ mice. In WT mice, the amplitude of the a-wave recovered with a time constant of ∼6.5 min, achieving the dark-adapted baseline within ∼20 min. RhoTvrm1/+ mice recovered more slowly, with a time constant of ∼11.5 min, and the asymptotic level fell short of the dark-adapted value. RhoTvrm4/+ mice recovered with a time constant of ∼9.5 min, but achieved an asymptote that was only ∼60% of the dark-adapted value. Thus, both RhoTvrm1/+ and RhoTvrm4/+ mice display deficits in bleaching recovery when assayed with an outcome measure related to photoreceptor function.

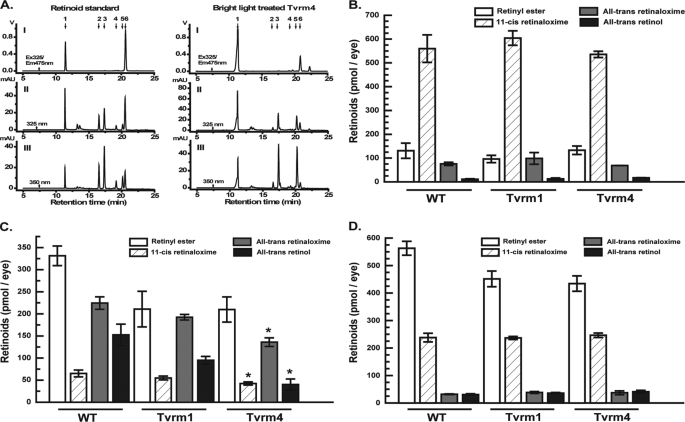

Retinoid Metabolism Is Transiently Affected in the Mutants

HPLC using both fluorescence and multiwavelength absorbance detection allowed separation and quantification of the major retinoid species (Fig. 5A). The levels of the major retinoid species present in extracts from whole dark-adapted eyes did not differ significantly for RhoTvrm1/+ or RhoTvrm4/+ mice as compared with WT controls (Fig. 5B). However, RhoTvrm4/+ eyes collected immediately after exposure to 12,000 lux for 5 min (Fig. 5C) contained significantly lower levels of all-trans-retinol than did WT eyes (p < 0.05). Levels of these retinoids were also lower in RhoTvrm1/+ eyes, although the differences were not statistically significant (p > 0.05). After 1 h of recovery following light exposure (Fig. 5D), there were no statistically significant differences in levels of any retinoids between the mutant and WT animals. The differences in retinoid levels observed in the mutants are thus transient, and do not seem to involve significant differences in the availability of 11-cis-retinal following a bleach.

FIGURE 5.

HPLC analysis of visual cycle retinoids. A, typical HPLC chromatograms; 1, retinyl esters; 2, syn-11-cis-retinaloxime; 3, syn-all-trans-retinaloxime; 4, anti-11-cis-retinaloxime; 5, anti-all-trans-retinaloxime; 6, all-trans-retinol. Panel I, fluorescence detection with 325 nm excitation and 475 nm emission; II, detection of retinyl ester and retinol at 325 nm by photodiode array detector; III, detection of oximes at 350 nm by photodiode array. B, retinoid levels in dark adapted WT, Tvrm1, and Tvrm4 mice. Total amounts extracted, as described under “Materials and Methods,” are plotted in units of pmol/eye. C, retinoid levels immediately after exposure to bright light. Amounts extracted from eyes immediately after exposure to bright light are shown. D, recovery of retinoids 1 h after return to darkness. After treatment with bright light, animals were returned to darkness for 1 h prior to collection of eyes and extraction of retinoids. Data are mean ± S.E. p < 0.05 One-way ANOVA using the F-distribution for samples from all three genotypes followed by Dunnett's test, n = 4 samples of 3 eyes each.

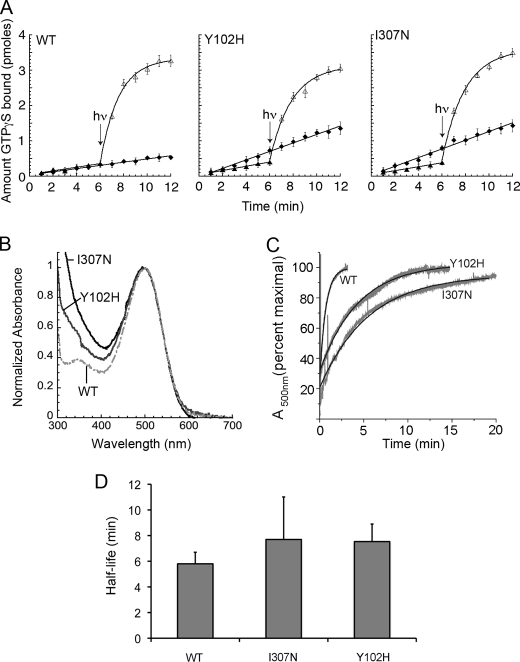

The Mutant Opsins Are Constitutively Active and Bind Chromophore More Slowly than Does WT Opsin

To better understand the relationship between the observed disease phenotype and the effects of the mutations on rhodopsin function, we expressed Y102H (Tvrm1) opsin and I307N (Tvrm4) opsin in COS cells and analyzed the biochemical outcome of the respective mutations. We first examined the ability of the receptors to signal effectively. When 11-cis-retinal was added, both Y102H and I307N rhodopsin formed pigments with visible absorbance spectra characteristic of WT rhodopsin (Fig. 6B). Similar to WT rhodopsin, both mutant rhodopsins activate transducin in a light-dependent manner (Fig. 6A), however, unlike WT opsin, Y102H and I307N opsins are constitutively active (Fig. 6A).

FIGURE 6.

In vitro biochemistry of mutant and WT rhodopsin. A, transducin activation by receptors in the presence and absence of chromophore is not impaired in the mutants. Closed diamonds, time course for the reaction catalyzed by the apoprotein opsin. Closed circles, time course for the reaction catalyzed by rhodopsin in the dark (all slopes shown are indistinguishable from those observed with transducin alone under these conditions). Open triangles, time course for the reaction catalyzed by rhodopsin after exposure to light (hν). The data are plotted as mean ± S.D. B, normalized dark absorbance spectra show maximum absorbance of mutants similar to that of WT rhodopsin. C, the mutant opsins bind chromophore more slowly than does WT opsin. Kinetics of retinal binding to Y102H (N2C, Y102H, D282C) and I307N (N2C, D282C, I307N) opsins are slowed relative to ET (N2C, D282C) opsin. Opsins were purified, and change in absorbance at 500 nm was recorded continuously after addition of a 5-fold molar excess of 11-cis-retinal. The absorbance values were normalized by the final maximum changes observed for each experiment. Representative raw data are depicted in gray, and the calculated best-fit curve for a single exponential in black. Mean lifetimes ± S.E. measured were as follows: 0.655 ± 0.014 min for WT, 4.32 ± 0.44 min for Y102H, and 5.94 ± 0.29 min for I307N (p < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA). D, mean half-lives of metarhodopsin II decay for WT (N2C, D282C), Y102H (N2C, Y102H, D282C), and I307N (N2C, D282C, I307N) rhodopsin. Rhodopsin, in the presence of a 3-fold molar excess of 11-cis-retinal, was exposed to white light passed through a 480-nm cut-on filter for 1 s, and the change of absorbance at 500 nm was monitored. Under these conditions, the rate-limiting step in regeneration is that of metarhodopsin II (3). The mean half-life of metarhodospin II decay of the mutants was not significantly different from the WT value, one-way ANOVA.

The toxicity of a constitutively active opsin mutant may depend upon how long it stays in the free opsin form before binding to 11-cis-retinal to regenerate rhodopsin. To determine the effect of the rhodopsin mutations on regeneration kinetics, we introduced them in the context of a N2C,D282C mutant background that allows WT and mutant opsins to be purified in detergent without denaturation in the absence of chromophore (33). When we measured the kinetics of regeneration (Fig. 6C), we observed that the mutants bound retinal more slowly than WT bound retinal; the mean lifetimes measured were as follows: 0.655 min (±0.014 S.E.) for WT, 4.32 min (±0.44 S.E.) for Y102H, and 5.94 (±0.29 S.E.) for I307N (p < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA). These results reveal that not only are the mutant opsins constitutively active, but their binding to the inverse agonist 11-cis-retinal is slower.

However, whereas the mutant opsins are slow to bind 11-cis-retinal and are constitutively active, the lifetimes of the active form of the mutant receptors (metarhodopsin II) are similar to that of WT metarhodopsin II. Fig. 6D shows that the mean half-life of metarhodopsin II decay is only 48% longer for Y102H than that of WT, and 53% longer for I307N. ANOVA or a Dunnett test of results for all three proteins taken together yields a p > 0.05; therefore, although we cannot rule out that there may be small differences in the kinetics of MII decay, there is no evidence for such differences contributing to the observed retinal degeneration.

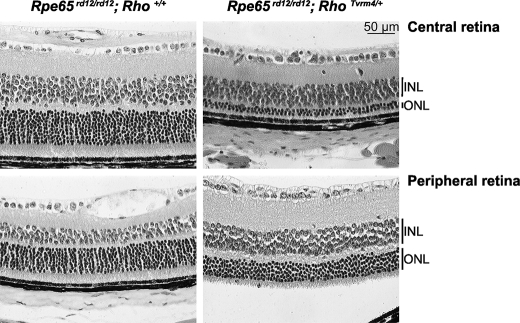

Mutant Opsin Leads to Photoreceptor Degeneration without Exposure to Bright Light

We hypothesized that free opsin might be toxic to the retina because the mutant opsins were constitutively active and the photoreceptors degenerated after exposure to bright light, which would lead to increased production of free opsin not bound to its chromophore. To test this hypothesis, we produced mice lacking the chromophore by mating Tvrm1 and Tvrm4 animals with rd12 mutants, null for Rpe65 (38), and reared them under standard light conditions. At 4 weeks of age, retinas of Rpe65rd12/rd12;Rho+/+ mice retained a full complement of photoreceptor nuclei (Fig. 7). In comparison, at this age Rpe65rd12/rd12/RhoTvrm4/+ and Rpe65rd12/rd12/RhoTvrm1/+ double mutants had only 2–3 (Fig. 7) or ∼5 rows, respectively, of cell bodies remaining in the central ONL (data not shown). In both double mutants, the peripheral retina that also showed cell loss was better preserved than the central retina. The morphological changes in the photoreceptors of the double mutants were different from those observed for RhoTvrm1/+ or RhoTvrm4/+ single mutants at 1 week following bright light exposure (Fig. 2B). Neither double mutant developed chromatin aggregates nor disruption of the laminar organization of the retina.

FIGURE 7.

Mutant opsins lead to photoreceptor degeneration without exposure to bright light. Histological sections from central and peripheral retinas of 4-week-old Rpe65rd12/rd12,Rho+/+ and Rpe65rd12/rd12/RhoTvrm4/+ animals, n = 3 mice.

DISCUSSION

Described herein are two new mouse models harboring point mutations in the rhodopsin gene. Although the affected amino acid residues involved lie in different domains of the rhodopsin molecule, these models share several important similarities. First, both lines originally identified by a hypopigmented fundus appearance are highly sensitive to light-induced photoreceptor degeneration. Second, despite this increased susceptibility to light damage, when reared under standard animal housing conditions, both lines retain a normal complement of photoreceptors up to 1 year of age, the latest time point examined. Third, whereas the activation and deactivation kinetics of rod phototransduction appear normal upon ERG analysis, both Y102H and I307N mutations cause a delay in the response recovery following bleaching. When examined at the biochemical level, this delay appears to be the net result of a decrease in the rate at which the mutant opsins bind the chromophore 11-cis-retinal and a higher than normal activation of transducin by unbound opsin. Finally, unlike transgenic lines that are currently available, the mutant rhodopsin gene is expressed under control of the endogenous promoter in both RhoTvrm1/+ and RhoTvrm4/+ mice.

Exposure to Bright Light Is Necessary for Degeneration of the RhoTvrm1/+ and RhoTvrm4/+ Photoreceptors

Unlike other Rho models in which photoreceptor degeneration is accelerated by light exposure and occurs even when mice are dark-reared (16, 39–42), RhoTvrm1/+ and RhoTvrm4/+ mice maintained under standard animal housing conditions have normal photoreceptor morphology and function. A rapid and severe degeneration of photoreceptors only occurs upon exposure to bright light. Our results show that the rate of this degeneration is dependent upon the duration of light exposure. It seems likely that the threshold at which degeneration is induced reflects the bleaching level at which the capacity of the visual cycle is surpassed, thereby allowing free opsin to remain in an active state for a damaging period of time. This feature of inducible photoreceptor degeneration may make these mice valuable models to study mechanisms underlying light-induced retinal damage and for testing pharmacological and environmental therapeutic strategies as the initiation of disease by light exposure can be reproducibly controlled.

RhoTvrm1/+ and RhoTvrm4/+ Mutants Recapitulate Features of the RHO Class B1 Phenotype

The disease phenotypes of RhoTvrm1/+ and RhoTvrm4/+ mice includes focal areas of photoreceptor degeneration and normal photoreceptor functionality with delayed dark adaptation. These features closely resemble the phenotype of patients with RHO class B1 mutations (15, 16). In fact, the residue altered in RhoTvrm1/+ mutants (Y102H) lies close to a G106Y missense mutation found in humans with class B1 RP (43). The altered residue in RhoTvrm4/+ mutants (I307N) is close to the Q312ter mutation that leads to class B RP (15) and an A295V mutation associated with stationary night blindness (44).

Although a causal role for light in the progression of photoreceptor degeneration in humans with RHO mutations has not been established, light has been shown to induce photoreceptor degeneration in animal models of class B1 RP (45). It is difficult to establish that any known human rhodopsin mutation is light-inducible, as humans with RP are typically exposed to sunlight that is much brighter than standard animal housing lighting conditions. Although mice are different from humans, it is possible that limiting exposure to bright light may not only help to slow the progression of photoreceptor loss in patients with some RHO mutations, but as shown in the mutants studied here, may actually prevent the onset of degeneration. Our data suggest that patients bearing rhodopsin mutations that cause high opsin activity or slow regeneration might be well advised to avoid exposure to bright light.

Mutant Opsin Leads to Prolonged Dark Adaptation and Constitutive Activation

Aside from light-induced photoreceptor degeneration, the only functional defect detectable in the Rho mutants is a prolonged dark adaptation recovery following bleaching light levels. Dark adaptation delays have been previously observed in RP patients bearing RHO mutations (46) and in the T4R dog model (19). Dark adaptation is a function of phototransduction deactivation and chromophore release, recycling, and regeneration with opsin (47). We hypothesized that only those processes directly involving the opsin molecule might be affected in the RhoTvrm1/+ and RhoTvrm4/+ and that recycling of the chromophore itself would not be altered by the observed mutations. Our in vitro studies implicate several features of rhodopsin biochemistry in the dark adaptation delays noted functionally. For example, rhodopsin regeneration is delayed simply because Y102H and I307N opsins bind to 11-cis-retinal at a slower rate than WT opsin. In addition, immediately following bright light exposure, the total levels of retinoids were decreased in the retinas of mutant animals compared with the WT. As a consequence, the pool of retinoids necessary for rhodopsin regeneration are significantly reduced during the initial stages of dark adaptation. Finally, we noted that the unbound Y102H and I307N opsins increase transducin activation at higher levels than WT opsin. Although free WT opsin is capable of activating transducin, the activation levels are far below those for R* (48). In the case of the Y102H and I307N mutants, constitutive transducin activation by the free mutant opsin molecules also slows recovery following exposure to bleaching levels of light.

Mutant Free Opsin May Lead to Photoreceptor Degeneration in RhoTvrm1/+ and RhoTvrm4/+ Mutants

Exposure to bright light leads to production of high levels of retinoid metabolites and intermediates of phototransduction, as well as to higher levels of free opsin. In the mutants, delayed rhodopsin regeneration serves to increase the level of free opsin following bright light exposure. This excess of mutant-free opsin is likely to have a greater propensity to activate transducin. To test the hypothesis that mutant-free opsin is an important contributor to the photoreceptor degeneration in RhoTvrm1/+ and RhoTvrm4/+ mutants, both Rho lines were crossed to Rpe65rd12/rd12 mice lacking functional RPE65 (38), in which the retinal pigment epithelium is unable to regenerate 11-cis-retinal and therefore, leads to an accumulation of free opsin. Although Rpe65rd12/rd12 mice expressing WT rhodopsin retain a near-normal complement of photoreceptors at 4 weeks of age, photoreceptors of double mutants: Rpe65rd12/rd12/RhoTvrm1/+ and Rpe65rd12/rd12/RhoTvrm4/+ mice degenerated without exposure to bright light and at a much faster rate than unexposed RhoTvrm1/+, RhoTvrm4/+, or Rpe65rd12/rd12,Rho+/+ mice. This indicates that the Y102H and I307N opsins may be more toxic than WT opsin or alternatively, higher levels of constitutive activation may accelerate the photoreceptor degeneration observed in the Rho mutants. Constitutive opsin activation is thought to underlie the loss of visual sensitivity in forms of congenital stationary night blindness caused by rhodopsin mutations in which photoreceptor degeneration does not occur (31, 49, 50), or occurs at a slow rate (44). Taken together, we interpret the results of the double mutant experiment to indicate that the Y102H and I307N rhodopsin mutations result in a longer-lived opsin with dominant cell-toxic features. Under normal housing conditions, the levels of free opsin generated are below the threshold for inducing photoreceptor degeneration. Only when exposed to bright light, or deprived of 11-cis-retinal, do the opsin levels exceed the threshold for initiation of apoptotic cell death pathways.

Allelic Differences between Tvrm1 and Tvrm4

The RhoTvrm1/+ and RhoTvrm4/+ mutations are located in the 1st extracellular loop and the 7th transmembrane region, respectively. Despite these differences in locations, they cause similar disease phenotypes. The regions in which the mutations occur do not have similar reported functions. However, it is interesting to note that they are both located near regions of the molecule that play a role in rhodopsin dimer formation (51). RhoTvrm1/+ (Y102H) lies near Tyr-96 and His-100 from helix II, which form a secondary cluster of side chains connecting the two rhodopsin subunits. RhoTvrm4/+ (I307N) lies close to Cys-322 and Cys-323 of H-8 helix that have associated palmitoyl groups that may also play a role in dimer stabilization. Although we do not have any evidence that the mutations do indeed affect the stability of the rhodopsin dimers, the availability of these Rho models will allow for further in vivo exploration of this observation.

Finally, whereas both RhoTvrm1/+ and RhoTvrm4/+ mutants share similar disease phenotypes, their rate of disease progression and the level of light exposure necessary to induce photoreceptor degeneration differ. The RhoTvrm1/+ mutation is more susceptible to light-induced damage than RhoTvrm4/+ mutants and a shorter duration of light exposure is necessary to induce photoreceptor degeneration. However, the RhoTvrm4/+ opsin appears to be more cytotoxic, as the retinas of RhoTvrm4/+ mutants degenerate faster when expressed in the absence of Rpe65. This suggests that mutant opsin toxicity and the functionality of the mutant opsin upon exposure to bright light are not completely equivalent and that bright light exposure not only increases the level of free opsin in the retina but possibly affects other factors that lead to photoreceptor degeneration. The models described here will allow for further exploration of the in vivo structure and function of the rhodopsin molecule.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ananth Badrinanth for genetic mapping of the mutation in the backcross progeny, the animal technicians, and the scientific services at The Jackson Laboratory. The Jackson Laboratory core services were supported by institutional Grant CA-24190.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant CA-34196 from the NCI, grants from the Maine Institute of Human Genetics & Health (to P. M. N.), Foundation Fighting Blindness (to P. M. N.), National Institutes of Health Grant EY016510 (to P. M. N.), Research to Prevent Blindness (to N. S. P.), Prevent Blindness Ohio (to M. S.), the Medical Research Service Department of Veterans Affairs (to N. S. P.), Hope for Vision (to N. S. P.), EyeSight Foundation of Alabama (to A. K. G.), the Karl Kirchgessner Foundation (to A. K. G.), and National Institutes of Health Grant EY07981 (to T. G. W.).

- R*

- metarhodopsin II

- TVRM

- translational vision research models

- TUNEL

- terminal uridine deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling

- ERG

- electroretinogram

- ISI

- inter-stimulus interval

- Bistris propane

- 1,3-bis[tris(hydroxymethyl)methylamino]propane

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- RP

- retinitis pigmentosa

- WT

- wild type

- MOPS

- 4-morpholinepropanesulfonic acid

- HPLC

- high pressure liquid chromatography

- GTPγS

- guanosine 5′-3-O-(thio)triphosphate.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rim J., Oprian D. D. (1995) Biochemistry 34, 11938–11945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li T., Franson W. K., Gordon J. W., Berson E. L., Dryja T. P. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 3551–3555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Humphries M. M., Rancourt D., Farrar G. J., Kenna P., Hazel M., Bush R. A., Sieving P. A., Sheils D. M., McNally N., Creighton P., Erven A., Boros A., Gulya K., Capecchi M. R., Humphries P. (1997) Nat. Genet. 15, 216–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lem J., Krasnoperova N. V., Calvert P. D., Kosaras B., Cameron D. A., Nicolò M., Makino C. L., Sidman R. L. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 736–741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toda K., Bush R. A., Humphries P., Sieving P. A. (1999) Vis. Neurosci. 16, 391–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berson E. L. (1993) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 34, 1659–1676 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartong D. T., Berson E. L., Dryja T. P. (2006) Lancet 368, 1795–1809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gal A., Apfelstedt-Sylla E., Janecke A., Zrenner E. (1997) Prog. Retinal Eye Res. 16, 51–79 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olsson J. E., Gordon J. W., Pawlyk B. S., Roof D., Hayes A., Molday R. S., Mukai S., Cowley G. S., Berson E. L., Dryja T. P. (1992) Neuron 9, 815–830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naash M. I., Hollyfield J. G., al-Ubaidi M. R., Baehr W. (1993) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 5499–5503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petters R. M., Alexander C. A., Wells K. D., Collins E. B., Sommer J. R., Blanton M. R., Rojas G., Hao Y., Flowers W. L., Banin E., Cideciyan A. V., Jacobson S. G., Wong F. (1997) Nat. Biotechnol. 15, 965–970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li T., Sandberg M. A., Pawlyk B. S., Rosner B., Hayes K. C., Dryja T. P., Berson E. L. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 11933–11938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kondo M., Sakai T., Komeima K., Kurimoto Y., Ueno S., Nishizawa Y., Usukura J., Fujikado T., Tano Y., Terasaki H. (2009) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 50, 1371–1377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tan E., Wang Q., Quiambao A. B., Xu X., Qtaishat N. M., Peachey N. S., Lem J., Fliesler S. J., Pepperberg D. R., Naash M. I., Al-Ubaidi M. R. (2001) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 42, 589–600 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cideciyan A. V., Hood D. C., Huang Y., Banin E., Li Z. Y., Stone E. M., Milam A. H., Jacobson S. G. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 7103–7108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cideciyan A. V., Jacobson S. G., Aleman T. S., Gu D., Pearce-Kelling S. E., Sumaroka A., Acland G. M., Aguirre G. D. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 5233–5238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang B., Hawes N. L., Hurd R. E., Wang J., Howell D., Davisson M. T., Roderick T. H., Nusinowitz S., Heckenlively J. R. (2005) Vis. Neurosci. 22, 587–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pinto L. H., Vitaterna M. H., Shimomura K., Siepka S. M., McDearmon E. L., Fenner D., Lumayag S. L., Omura C., Andrews A. W., Baker M., Invergo B. M., Olvera M. A., Heffron E., Mullins R. F., Sheffield V. C., Stone E. M., Takahashi J. S. (2005) Vis. Neurosci. 22, 619–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kijas J. W., Cideciyan A. V., Aleman T. S., Pianta M. J., Pearce-Kelling S. E., Miller B. J., Jacobson S. G., Aguirre G. D., Acland G. M. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 6328–6333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herron B. J., Lu W., Rao C., Liu S., Peters H., Bronson R. T., Justice M. J., McDonald J. D., Beier D. R. (2002) Nat. Genet. 30, 185–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Justice M. J., Zheng B., Woychik R. P., Bradley A. (1997) Methods 13, 423–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hawes N. L., Smith R. S., Chang B., Davisson M., Heckenlively J. R., John S. W. (1999) Mol. Vis. 5, 22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee Y., Kameya S., Cox G. A., Hsu J., Hicks W., Maddatu T. P., Smith R. S., Naggert J. K., Peachey N. S., Nishina P. M. (2005) Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 30, 160–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goto Y., Peachey N. S., Ziroli N. E., Seiple W. H., Gryczan C., Pepperberg D. R., Naash M. I. (1996) J. Opt. Soc. Am. A Opt. Image Sci. Vis. 13, 577–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim T. S., Maeda A., Maeda T., Heinlein C., Kedishvili N., Palczewski K., Nelson P. S. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 8694–8704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Groenendijk G. W., De Grip W. J., Daemen F. J. (1980) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 617, 430–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Groenendijk G. W., Jansen P. A., Bonting S. L., Daemen F. J. (1980) Methods Enzymol. 67, 203–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garwin G. G., Saari J. C. (2000) Methods Enzymol. 316, 313–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferretti L., Karnik S. S., Khorana H. G., Nassal M., Oprian D. D. (1986) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 83, 599–603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Franke R. R., Sakmar T. P., Oprian D. D., Khorana H. G. (1988) J. Biol. Chem. 263, 2119–2122 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gross A. K., Rao V. R., Oprian D. D. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 2009–2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gross A. K., Xie G., Oprian D. D. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 2002–2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xie G., Gross A. K., Oprian D. D. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 1995–2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lamb T. D. (1996) Aust. N. Z. J. Ophthalmol. 24, 105–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pepperberg D. R., Birch D. G., Hofmann K. P., Hood D. C. (1996) J. Opt. Soc. Am. A Opt. Image Sci. Vis. 13, 586–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hetling J. R., Pepperberg D. R. (1999) J. Physiol. 516, 593–609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen J., Makino C. L., Peachey N. S., Baylor D. A., Simon M. I. (1995) Science 267, 374–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pang J. J., Chang B., Hawes N. L., Hurd R. E., Davisson M. T., Li J., Noorwez S. M., Malhotra R., McDowell J. H., Kaushal S., Hauswirth W. W., Nusinowitz S., Thompson D. A., Heckenlively J. R. (2005) Mol. Vis. 11, 152–162 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Naash M. I., Ripps H., Li S., Goto Y., Peachey N. S. (1996) J. Neurosci. 16, 7853–7858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang M., Lam T. T., Tso M. O., Naash M. I. (1997) Vis. Neurosci. 14, 55–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vaughan D. K., Coulibaly S. F., Darrow R. M., Organisciak D. T. (2003) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 44, 848–855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.White D. A., Fritz J. J., Hauswirth W. W., Kaushal S., Lewin A. S. (2007) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 48, 1942–1951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sung C. H., Schneider B. G., Agarwal N., Papermaster D. S., Nathans J. (1991) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 8840–8844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zeitz C., Gross A. K., Leifert D., Kloeckener-Gruissem B., McAlear S. D., Lemke J., Neidhardt J., Berger W. (2008) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 49, 4105–4114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gu D., Beltran W. A., Li Z., Acland G. M., Aguirre G. D. (2007) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 48, 4907–4918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kemp C. M., Jacobson S. G., Roman A. J., Sung C. H., Nathans J. (1992) Am. J. Ophthalmol. 113, 165–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lamb T. D., Pugh E. N., Jr. (2006) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 47, 5137–5152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Melia T. J., Jr., Cowan C. W., Angleson J. K., Wensel T. G. (1997) Biophys. J. 73, 3182–3191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dryja T. P., Berson E. L., Rao V. R., Oprian D. D. (1993) Nat. Genet. 4, 280–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rao V. R., Cohen G. B., Oprian D. D. (1994) Nature 367, 639–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Salom D., Lodowski D. T., Stenkamp R. E., Le Trong I., Golczak M., Jastrzebska B., Harris T., Ballesteros J. A., Palczewski K. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 16123–16128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]