Abstract

Problem Maternal mortality in Uganda has remained unchanged at 500/100 000 over the past 10 years despite concerted efforts to improve the standard of maternity care. It is especially difficult to improve standards in rural areas, where there is little money for improvements. Furthermore, staff may be isolated, poorly paid, disempowered, lacking in morale, and have few skills to bring about change.

Design Training programme to introduce criteria based audit into rural Uganda.

Setting Makerere University Medical School, Mulago Hospital (large government teaching hospital in Kampala), and Mpigi District (rural area with 10 small health centres around a district hospital).

Strategies for change Didactic teaching about criteria based audit followed by practical work in own units, with ongoing support and follow up workshops.

Effects of change Improvements were seen in many standards of care. Staff showed universal enthusiasm for the training; many staff produced simple, cost-free improvements in their standard of care.

Lessons learnt Teaching of criteria based audit to those providing health care in developing countries can produce low cost improvements in the standards of care. Because the method is simple and can be used to provide improvements even without new funding, it has the potential to produce sustainable and cost effective changes in the standard of health care. Follow up is needed to prevent a waning of enthusiasm with time.

Background

Uganda has one of the highest maternal mortalities in the world at 508/100 000.1 Although delays in women getting to a health centre are important, many problems can be attributed to the poor care they receive after reaching a health facility.2 These problems are often difficult to change, requiring changes in staff attitude and skills as well as financial input.

Criteria based audit has been introduced as a way of improving the quality of clinical care.3,4 It is adaptable to all situations as it does not give answers but empowers those performing it to develop local solutions for their problems. It is therefore relevant for healthcare workers at all levels. The traditional model has been criticised for focusing too much on data collection and not enough on the implementation of change.5 We sought to introduce a form of criteria based audit that focused on problem analysis and implementation of changes into Ugandan maternity units.

Outline of problem

Ugandan medical training has been criticised for being overcentralised, leaving staff unable to deal with the new situations and challenges of work in rural areas.6 This not only leaves health workers frustrated and demoralised but may lead to underuse and inefficient use of existing resources. We therefore sought to train healthcare workers of all levels in audit skills, teaching them to identify problems in the standard of clinical care, analyse the causes of suboptimal performance, and find locally appropriate solutions. We hoped that this would empower staff to make their own decisions and encourage active learning and participation.

Strategy for change

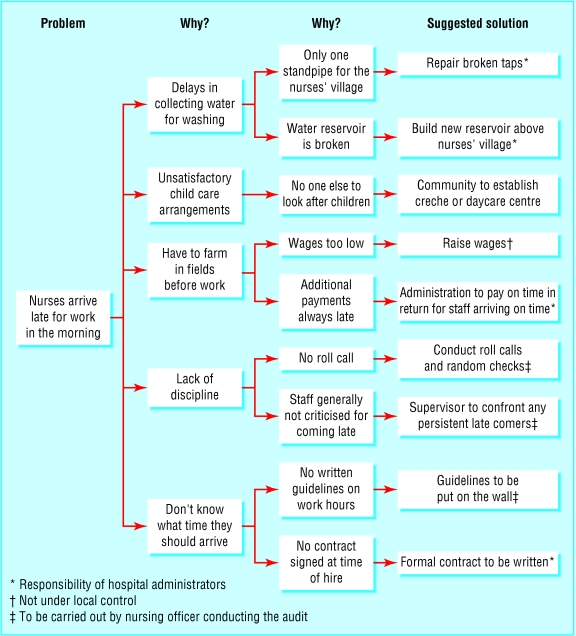

We set up a pilot programme to introduce criteria based audit into Ugandan maternity units. In addition to the usual audit cycle,7 we added two items from the performance improvement toolkit.8,9 These were “root cause” (or “why? why?”) analysis, which assists in analysing the underlying cause of a deficiency (see fig 1), and “action planning,” a system for project organisation.

Fig 1.

Example of a “why? why?” analysis for identifying the underlying cause of nursing staff arriving late for work

The “Audit in Maternity Care” pilot project was run between August and December 2001 jointly by the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology and the Regional Centre for Quality of Health Care at Makerere University Medical School. A small management team ran the project and reported back monthly to a stakeholders' meeting that included participants from the government and local non-governmental organisations.

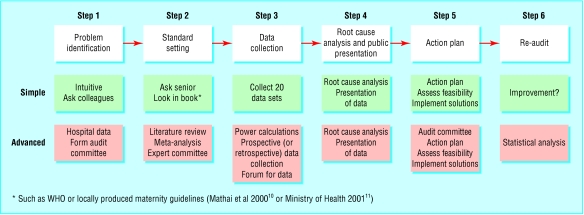

The audit training was made adaptable so that it would be relevant to the audience irrespective of whether they were rural health workers with little formal education or postgraduate medical trainees (fig 2). The versions differed primarily in the complexity of the standard setting and data collection (see bmj.com). All staff were expected to present their data, conduct a root cause analysis, and implement changes.

Fig 2.

The modified audit process, with simplified and advanced versions making it suitable for the training of all healthcare workers

The public presentation of the data allowed brainstorming among all those present, irrespective of whether they were an administrator, patient, local politician, doctor, healthcare assistant, or laboratory technician. This resulted in a wide range of suggested solutions, with public commitments by staff to implement changes. At the end of each root cause analysis, the list of solutions drawn up was sorted according to whether they were achievable by the person conducting the audit, someone locally, or only by authorities in the Ministry of Health. The action plan was simply a table (with columns for “Problem,” “Action,” “Who will implement the action?” and “By when?”) that would be completed for reference at each successive audit meeting.

Audit training

At service level—Workshops were held at Gombe Hospital in Mpigi District, a rural district hospital 60 miles from Kampala that acts as a referral centre for 10 surrounding health centres. Staff from the hospital and surrounding health centres were invited to each of the four workshops held: “introduction to audit,” “implementing change,” “troubleshooting,” and “long term follow up.” After each workshop, participants returned to their units to put what they had learnt into practice, presenting their progress at the next workshop. No new funding was available to implement changes.

Pre-service training at Makerere University— Undergraduate and postgraduate students in obstetrics received training sessions in audit skills. In addition, all interns passing through the department were required to complete an audit project. Large audit meetings in the form of “grand rounds” were also held in the medical school to allow those conducting the projects to present their work and to raise awareness of criteria based audit among hospital staff.

Effects of change

Over the six months of the pilot project, 170 maternity health workers were directly taught audit methods, and 23 audit projects were completed on various aspects of maternity care, including intraoperative monitoring for caesarean sections (see audit example on bmj.com for details), delays in starting drug treatment for malaria, late arrival for work among nursing staff (see fig 1 for the root cause analysis of this project), and high stillbirth rates. Staff used a variety of measures to improve care, including posting notices, improving organisation of the facility, and repairing broken equipment. In only one project was a formal re-audit conducted, and this showed significant improvements in the attainment of standards (see first audit example on bmj.com).

Evaluations after the training showed high satisfaction rates among attendees. Of the postgraduates attending the audit seminars, all agreed that the seminars were important for improving the quality of maternity care, although only 75% said that they would feel confident enough to conduct an audit on their own or teach audit methods to others. All of the 25 health workers attending the rural workshops felt that these were enjoyable and that they would feel able to conduct their own audits in future and teach the methods to others. All participants felt that their places of work had benefited from the workshops and that they would conduct additional audits in their own units in the future.

The authorities warmly received the project. The medical school has accepted audit as an important part of pre-service education and in service training, and has formally added it to the undergraduate and postgraduate curriculums. The Ministry of Health is to set up a central audit committee to coordinate audit projects nationally. The project itself has received funding for full implementation from the funders and is working with the government and local non-governmental organisations to expand the district training.

Lessons learnt

Criteria based audit can be taught and used in Africa

It is sometimes believed that criteria based audit is best used to perfect care in Western countries' healthcare systems, where the basic infrastructure is already in place. However, our experience is that criteria based audit can be effective even in much poorer areas with very limited resources. It can empower grassroots health workers to look for their own solutions to common problems, thus producing sustainable and cost effective changes in the standard of health care.

The importance of the root cause analysis in the criteria based audit cycle

For many participants the use of the “why? why?” analysis formed the central part of their project and provided a catchphrase for the workshops. Criteria based audit has often focused on the process of data collection, with many projects going no further than that. In this project we changed the emphasis and put the problem analysis and implementation of change at the heart of the process, only adding data collection in the more advanced versions. This simplified the process for the less educated participants and ensured that the most important component was never left out of the projects.

Involving government, senior staff, and administrators is crucial

Medical hierarchies in Africa are traditionally strong, and the empowerment of junior health workers to innovate and make their own improvements can cause anger and resentment if local government and hospital officials are not part of the process. Those in charge need to claim ownership of the process and see the improvements as their own, even if their contribution was facilitatory rather than active. Furthermore, many of the changes will require financial or organisational changes that can be made only by those who have authority within the system. It is therefore important that local government officials and hospital officials are involved throughout the audit process.

Continued support is needed for rural units

There was a gap of a year between the third and fourth workshops at Gombe Hospital, while reports were written and further funding sought. It was clear that little progress had been made on the projects until we declared our intention to return for follow up, when action plans were retrieved and hurriedly implemented. To remedy this, a local audit committee (and chairperson) was elected from among the participants, and a commitment was made for the project to return quarterly for follow up meetings. An annual national audit conference is being funded by the World Health Organization to allow those conducting audits around the country to present their audits and compete for prizes.

Conclusions

The “Audit in Maternity Care” programme has so far proved to be highly effective in stimulating health workers to analyse their own situations and provide creative solutions to problems. Feedback has been universally enthusiastic, and changes in practice have already been seen. And, perhaps more importantly, maternity staff have been empowered to analyse their own situations and provide their own solutions to healthcare problems.

Staff at all levels found that problems that they thought required large amounts of money and the work of powerful politicians to solve can often be tackled from below. Often an apparently insurmountable problem can be improved by surprisingly simple acts—a guideline posted on the labour suite wall, the repair of a broken machine, allowing women to keep their placentas after delivery as an incentive for institutional delivery, making accessible the equipment from the ward sister's cupboard, and regularly checking stocks. Because these small improvements can be made cheaply and by many members of staff, the combined effect can be impressive.

Only time will tell whether the widespread introduction of maternity audit can significantly improve maternal mortality in Africa, but history shows that many major advances have occurred only when ordinary people started taking action themselves rather than leaving problems to be sorted out by others. The Audit in Maternity Care project gives people the tools to do this.

Supplementary Material

Examples of audits undertaken appear on bmj.com

Examples of audits undertaken appear on bmj.com

We thank Nelson Sewankambo, dean of the Faculty of Medicine, for his support; Christine Biryabarema, Florence Ebanyat, Joel Okullo, and Olive Sentumbwe of the stakeholders committee; and the staff of Gombe Hospital, especially Valentine Kanyike, Fred Mukasa, and the late Mary Nalubega.

Contributors: ADW had the original idea for the work, supervised the project, chaired the project management committee, and wrote the paper. GA carried out the pre-eclampsia audit and implemented the changes. SO coordinated the audit project. AM and EOO advised on audit methods and the logistics of implementation. FMM had overall supervision of the implementation of the changes. All authors were part of the project management committee, taught the methods, and passed the final draft of this paper. ADW is guarantor for the study.

Funding: This project was funded by the Rockefeller Foundation through the Makerere University capacity building programme for decentralisation (I@mak.com).

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Uganda Bureau of Statistics and ORC Macro. Uganda demographic and health survey 2000-2001. Entebbe: UBOS, ORC Macro, 2001.

- 2.Jahn A, De Brouwere V. Referral in pregnancy and childbirth: concepts and strategies. Stud Health Services Organ Policy 2001;17: 229-46. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graham W, Wagaarachchi P, Penney G, McCaw-Binns A, Yeboah Antwi K, Hall MH. Criteria for clinical audit of the quality of hospital-based obstetric care in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ 2000;78: 614-20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Principles for best practice in clinical audit. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press, 2002.

- 5.Berger A. Why doesn't audit work? BMJ 1998;316: 875-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Makerere Institute of Social Research. Human resource demand assessment from the perspective of the district. Kampala: Makerere University, 2001.

- 7.Morrel C, Harvey G. The clinical audit handbook. London: Harcourt Brace, 1999.

- 8.Lande RE. Performance improvement. Population reports. Series J, No 52. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Population Information Program, 2002.

- 9.PRIME II Project. Performance improvement: Stages, steps and tools. www.prime2.org/sst (accessed 13 Feb 2003).

- 10.Mathai M, Sanghvi H. Guidotti RJ. Managing complications in pregnancy and childbirth: a guide for midwives and doctors. Geneva: WHO, 2000.

- 11.Ministry of Health. Essential maternal and neonatal care clinical guidelines for Uganda 2001. Kampala: Ministry of Health, 2001.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.