Abstract

The rate of ribosome synthesis is proportional to the rate of cell proliferation; thus, transcription of rRNA by RNA polymerase I (Pol I) is an important target for the regulation of this process. Most previous investigations into mechanisms that regulate the rate of ribosome synthesis have focused on the initiation step of transcription by Pol I; however, recent studies in yeast and mammals have identified factors that influence transcription elongation by Pol I. The RNA polymerase-associated factor 1 complex (Paf1C) is a transcription elongation factor with known roles in Pol II transcription. We previously identified a role for Paf1C in transcription elongation by Pol I. In this study, genetic interactions between genes for Paf1C and Pol I subunits confirm this conclusion. In vitro studies demonstrate that purified Paf1C directly increases the rate of transcription elongation by Pol I. Finally, we show that Paf1C function is required for efficient control of Pol I transcription in response to target of rapamycin (TOR) signaling or amino acid limitation. These studies demonstrate that Paf1C plays an important direct role in cellular control of rRNA expression.

Keywords: Ribosomal RNA (rRNA), Ribosomal RNA Processing, RNA Polymerase I, RNA Polymerase II, Transcription, Transcription Elongation Factors, Transcription Regulation

Introduction

RNA polymerase I (Pol I)2 transcribes the rRNA gene (rDNA) to produce the bulk of the ribosome. The synthesis of rRNA is an important rate-limiting step in ribosome assembly, which is connected to environmental stimulation, nutritional conditions, and cell growth rate (1, 2). Thus, appropriate regulation of rRNA synthesis is critical. Although the essential factors that compose the Pol I transcription machinery have been characterized, the molecular mechanisms responsible for the control of Pol I activity remain largely unknown. Definitive studies in yeast and mammalian cells have shown that the transcription initiation factor Rrn3p is an important target for the control of the rRNA synthesis rate (3–5); however, changes in Pol I loading (transcription initiation rate) cannot entirely account for observed changes in the rate of rRNA transcription (3).Thus, we and others have postulated that the elongation rate of Pol I transcription is regulated in response to growth conditions (6, 7). In this study, we define a direct role for the RNA polymerase-associated factor 1 complex (Paf1C) in this form of regulation.

Paf1C consists of five subunits: Cdc73p, Ctr9p, Leo1p, Rtf1p, and Paf1p (8, 9). Several lines of evidence suggest that Paf1C can influence transcription initiation and elongation by Pol II. Paf1C associates with both the promoter and coding regions of actively transcribed mRNA genes (10). Defects in Paf1C function affect expression of a subset of genes transcribed by Pol II (11, 12). Paf1C can regulate transcription initiation by affecting the association of the TATA-binding protein with the TATA box (13). Paf1C also interacts physically and/or genetically with known transcription elongation factors (Spt4p/Spt5p and FACT) (14, 15). Additionally, both in vivo and in vitro transcription assays show that Paf1C enhances the efficiency of transcription elongation by Pol II (11, 16, 17). Thus, the roles for Paf1C in Pol II transcription are robust.

Paf1C also influences mRNA processing and modifications of chromatin structure. Mutations in genes for Paf1C subunits affect the length of poly(A) tails on multiple mRNAs and impair the processing of small nucleolar RNAs (18, 19). Paf1C recruits the COMPASS methyltransferase to Pol II and is essential for the methylation of histone H3 Lys4 and Lys79 in yeast, fly, and human (20–22). Efficient monoubiquitination of histone H2B requires Paf1C as well (23).

We recently identified a new role for Paf1C in transcription elongation by Pol I (7). Paf1C associates with rDNA in vivo. Deletion of the Paf1C subunit gene CDC73, CTR9, or PAF1 caused a reduced rRNA synthesis rate; however, this decrease was not due to a reduction in Pol I occupancy of the rDNA or a decline in the percentage of actively transcribed rDNA repeats. These data led us to conclude that Paf1C plays a positive role in transcription elongation by Pol I (7). Because Paf1C participates in both Pol I and Pol II transcription, our previous in vivo studies could not exclude indirect effects of Paf1C on Pol I through changes in mRNA expression.

In this study, we demonstrate that Paf1C directly participates in Pol I transcription elongation. Synthetic genetic interactions between mutations in genes for Paf1C subunits (ctr9Δ and paf1Δ) and a nonessential Pol I subunit (rpa49Δ) support the conclusion that Paf1C is important for transcription elongation by Pol I in vivo (7). Furthermore, we demonstrate that purified Paf1C directly increases the rate of transcription elongation by Pol I in vitro. Finally, Paf1C is required for efficient control of rRNA synthesis in response to rapamycin treatment or starvation for histidine (using 3-aminotriazole (3-AT)). In the absence of PAF1, Pol I occupancy of the rDNA and rRNA synthesis rates remain elevated after treatment with rapamycin compared with wild-type (WT) cells. Taken together, these data demonstrate that Paf1C directly enhances the rate of transcription elongation by Pol I and serves as an important regulator of rRNA synthesis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Strains and Media

The yeast strains and plasmids used are listed in Table 1. Yeast cells were grown in either synthetic glucose (SD) medium or yeast extract/peptone/dextrose (YEPD) medium at 30°C with aeration. YEPD medium consisted of 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 2% dextrose. S-minimal medium supplemented with glucose and essential nutrients was made according to the following recipe: 0.17% yeast nitrogen base (without amino acids or ammonium; Difco, Detroit, MI), 0.5% ammonium sulfate, 2% dextrose, and 0.087% nutrient mixture. The complete nutrient mixture contained 0.8 g of adenine, 0.8 g of arginine, 4 g of aspartic acid, 0.8 g of histidine, 2.4 g of leucine, 1.2 g of lysine, 0.8 g of methionine, 2 g of phenylalanine, 8 g of threonine, 0.8 g of tryptophan, 1.2 g of tyrosine, and 0.8 g of uracil. Where indicated, dropout nutrient mixtures were made, omitting the specified nutrients (e.g. −Met −His dropout used for methylmethionine labeling in the presence of 3-AT).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Description | |

|---|---|

| Strain | |

| NOY396 | MATα ade2-1 ura3-1 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 his3-11,15 can1-100 |

| DAS50 | Same as NOY396, but rpa49Δ::LEU2; MATa |

| DAS317 | Same as NOY396, but PAF1-His7-(HA)3::HIS3 |

| DAS511 | Same as NOY396, but cdc73Δ::HIS3 |

| DAS513 | Same as NOY396, but ctr9Δ::HIS3 |

| DAS516 | Same as NOY396, but paf1Δ::HIS3 |

| DAS549 | Same as NOY396, but rtf1Δ::HIS3 |

| DAS550 | Same as NOY396, but leo1Δ::HIS3 |

| Plasmid | |

| pRS313 | pBluescript, CEN6, ARSH4, HIS3 (36) |

| pRS316 | pBluescript, CEN6, ARSH4, URA3 (36) |

Genetic Interactions

Genes were deleted as described previously (37). Strains with the indicated deletions (cdc73Δ, ctr9Δ, leo1Δ, paf1Δ, and rtf1Δ) were individually mated with DAS50 (rpa49Δ). The resulting diploids were sporulated and dissected on YEPD plates. Four segregants from a single tetrad representing all four possible genotypes were grown in SD complete medium overnight and diluted to A600 = 0.1, and then 10-μl samples of serial dilutions were spotted onto SD complete medium. After 2 days of incubation at 30°C, colonies were photographed.

Measurement of RNA Synthesis

[3H]Uridine and [3H]methylmethionine incorporation assays were performed as described (7). The final concentration of rapamycin added to each culture was 0.2 μg/ml. 3-AT was added to a final concentration of 10 mm in medium lacking histidine.

Purification of Paf1C

Cells expressing His7-(HA)3-tagged Paf1p (DAS317) were grown in 12 liters of YEPD medium to A600 = 0.6. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed in breakage buffer (500 mm potassium acetate, 20 mm Tris acetate, 10% glycerol, 20 mm imidazole, and 0.1% Tween 20, pH 7.9), and frozen at −80 °C. Cells were resuspended in breakage buffer and broken with glass beads in a FastPrep system (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH). Cleared lysates were incubated with 1 ml of nickel resin for 1 h in batch at 4 °C. Resin was loaded into a column and washed with 5 column volumes of breakage buffer. Proteins were eluted from the nickel resin using breakage buffer and 500 mm imidazole. This eluate was incubated with 200 μl of anti-HA affinity resin (Sigma) for 2 h at 4 °C with agitation. Beads were washed four times with 1 ml of breakage buffer and eluted with four successive 1-ml washes with breakage buffer and 150 μg/ml HA peptide. This eluate was washed and concentrated into storage buffer (100 mm potassium glutamate, 25 mm Tris acetate, pH 7.9, 8 mm magnesium acetate, and 10% glycerol) using a 50-kDa cutoff column (Millipore, Billerica, MA).

Mass Spectrometry

Mass spectrometry was performed essentially as described previously (38). Individual protein bands were excised from the gel with a razor blade and subjected to in-gel tryptic digestion (with reduction by 10 mm dithiothreitol and alkylation with 50 mm iodoacetamide). Tryptic digests were loaded onto a liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry system composed of a Micro AS autosampler, LC nanopump (Eksigent), and a linear ion trap-Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance hybrid mass spectrometer (LTQ FT-ICR, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The analytical column was a 100-μm diameter, 11-cm column pulled tip packed with Jupiter 5-μm C18 reversed-phase beads (Phenomenex). An acetonitrile gradient from 5 to 40% in 0.1% formic acid was run over 50 min at 650 nl/min. LTQ FT-ICR parameters were set as described previously(38). Yeast peptides were identified using TurboSEQUEST v.27 (rev.12, Thermo Fisher Scientific), MASCOT 2.2 (Matrix Biosciences), and Protein Prospector v.5.2.2 (University of California, San Francisco) (39) algorithms with tryptic cleavage and a parent ion mass accuracy of 10.0 ppm. SEQUEST and MASCOT results were further refined through the transproteomic pipeline with Peptide Prophet and Protein Prophet (40). All proteins isolated as part of Paf1C were identified with at least 10 or more unique peptides for protein assignment.

In Vitro Transcription by Pol I

Transcription elongation assays were performed as described previously (25), except the nucleotide triphosphate concentrations used were 100 μm ATP and UTP and 10 μm GTP (+[α-32P]GTP) for transcription initiation, followed by 100 μm CTP to clear the +56 block. The reduced NTP concentrations used account for the relatively slow elongation rates measured (see Fig. 2C). This reduction is necessary to permit accurate quantification of elongation rates in vitro.

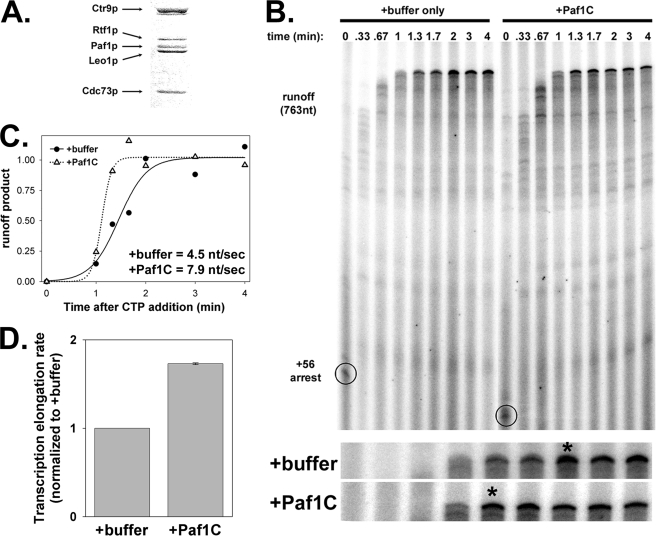

FIGURE 2.

Paf1C directly affects Pol I transcription in vitro. A, Paf1C was purified using His7-(HA)3-Paf1p. The Coomassie Blue-stained gel shows the positions of the five Paf1C subunits. Subunit identification was assigned based on molecular mass (the His7-(HA)3 tag adds 5.5 kDa to Paf1p) and confirmed by mass spectrometry. B, transcription elongation assays were performed in the presence of Paf1C or a buffer-only control. The positions of complexes synchronized (−CTP) at position +56 and the 763-nucleotide (nt) runoff product are indicated. Below the gel, an expanded view of runoff product accumulation is provided, with first point of maximum accumulation denoted with an asterisk. C, runoff product accumulation was quantified by phosphorimaging analysis and plotted versus time. Data were fit to sigmoidal curves. Elongation rates were estimated from the plots. D, activation of the Pol I elongation rate, normalized to the +buffer control, was averaged between three independent transcription elongation assays. Error bars represent ±1 S.D.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation

ChIP analysis was performed as described previously (7). Pol I was immunoprecipitated with a rabbit polyclonal antibody specific to the A190 subunit.

RESULTS

Genetic Interactions Confirm a Role for Paf1C in Pol I Transcription

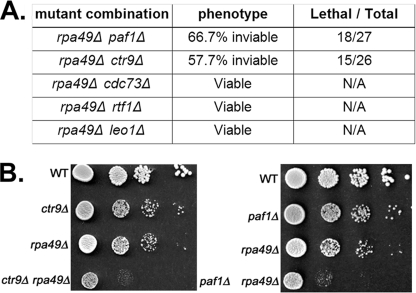

Pol I consists of 14 subunits; however, four of these subunits (A49, A34, A14, and A12) are not essential for growth (for review, see Ref. 2). In vitro studies have demonstrated that A49 functions as an intrinsic transcription elongation factor for Pol I (24). Therefore, genetic interactions between rpa49Δ and mutations in genes for Paf1C subunits would support the model that Paf1C participates in Pol I transcription elongation.

We mated a strain carrying a deletion of RPA49 with strains carrying deletions of genes for each of the five subunits of Paf1C. We sporulated the resulting diploid strains and scored for synthetic growth defects after tetrad dissection (Fig. 1A). To recover double mutants, we incubated the dissection plates >7 days at 30 °C. We found that only ∼30% of paf1Δ rpa49Δ double mutants produced viable spores. Similarly, only 40% of ctr9Δ rpa49Δ segregants germinated (Fig. 1A). We confirmed the synthetic growth defect of the double mutant strains by plating serial dilutions of the cells on standard medium compared with single mutant parental strains and the WT control (Fig. 1B). Growth of the double mutant strains was worse than the additive growth defects of the individual parental mutants (Fig. 1B).The simplest interpretation of this synthetic growth defect is that PAF1 and CTR9 are required for efficient Pol I transcription.

FIGURE 1.

rpa49Δ paf1Δ and rpa49Δ ctr9Δ strains exhibit severe growth and survival defects. A, shown are genetic interactions between rpa49Δ and deletion of genes for all five Paf1C subunits. B, segregants were grown in SD complete medium overnight and diluted to A600 = 0.1, and then 10-fold serial dilutions were spotted on SD complete plates. After 2 days of incubation at 30°C, colonies were photographed.

In contrast, the modest growth defects in the cdc73Δ, leo1Δ, and rtf1Δ strains were not exacerbated by the absence of RPA49 (Fig. 1A). It is well known that deletion of CDC73, LEO1, or RTF1 does not lead to severe defects in growth rate, whereas deletion of PAF1 or CTR9 does. It is also clear that expression of rRNA is intimately linked to cell growth and proliferation rates. Thus, our observation that Paf1p and Ctr9p play more critical roles in Pol I transcription than the other three subunits is expected.

As a control for these genetic experiments, we also mated paf1Δ and ctr9Δ strains with strains carrying deletions of RPA34 or RPA12 (genes for subunits of Pol I that do not have defined roles in transcription elongation). These mutant combinations were not synthetic lethal (data not shown). These data, together with previous observations, demonstrate that Paf1p and Ctr9p play central roles in transcription elongation by Pol I.

Paf1C Directly Increases the Rate of Transcription Elongation by Pol I

Genetic interactions (Fig. 1) and previously reported in vivo analyses suggested (7) that Paf1C is involved in Pol I transcription elongation. However, it is difficult to differentiate direct from indirect roles for Paf1C in Pol I transcription, given its many published roles in Pol II activity and chromatin modifications. Thus, we purified Paf1C and performed in vitro transcription elongation assays to directly measure the effect of Paf1C on the rate of Pol I transcription elongation (25).

To purify Paf1C, we used a strain expressing His7-(HA)3-tagged Paf1p. After nickel affinity chromatography and anti-HA immunoaffinity enrichment, we concentrated the protein preparation and analyzed the sample by SDS-PAGE. Coomassie Blue-stained gel bands were digested with trypsin, and all five Paf1C subunits were confirmed by high resolution mass spectrometry (Fig. 2A). No other transcription elongation factors (e.g. Spt4p/Spt5p or FACT) were detected. By inspection of the gel, we estimated that the protein preparation was at least 90% pure.

We have previously developed an assay for accurate measurement of Pol I transcription elongation rate in vitro (25). The linear rDNA template used in this assay is identical to the chromosomal rDNA promoter region and 5′-external transcribed spacer except that all C residues (in the nontemplate strand) in the first 56 positions of the 5′-external transcribed spacer are mutated to G. To perform the assay, we incubated purified Pol I and required transcription factors (upstream activation factor, TATA-binding protein, core factor, and Rrn3p) with the rDNA template to pre-form transcription initiation complexes. Then, purified Paf1C (or storage buffer as a negative control) was added to the transcription reactions. Transcription was initiated with a mixture of three NTPs (ATP, GTP, UTP, [α-32P]GTP). As a result, transcription elongation complexes were synchronized at +56 (the position of the first C in the nontemplate strand, numbered relative to the transcription start site). Heparin was added to reactions to disrupt remaining preinitiation complexes and to prevent reinitiation. Thus, we assayed only a single round of transcription. Finally, CTP was added to the master reactions, and samples were collected as a function of time. The resulting products were analyzed by phosphorimaging after electrophoresis (Fig. 2B). Qualitative analysis revealed that maximum runoff product accumulated faster in the presence of Paf1C than in its absence (Fig. 2B, asterisks in expanded views of the product). To quantify the data, we generated a regression from the amount of runoff products versus time (Fig. 2C). The data were fit to a sigmoidal curve as expected for runoff product accumulation, and from these plots, we estimated that the Pol I transcription rate in the presence of Paf1C was 1.75-fold higher than in the control reaction.

Although this difference is relatively small, it was highly reproducible under variable buffer conditions and using independent preparations of Paf1C. In each experiment, the absolute elongation rate calculated varied for +buffer and +Paf1C reactions (due to small variation in temperature or intentional changes in NTP concentration). However, when we normalized the +Paf1C elongation rate to the +buffer control rate, we observed a reproducible 1.75-fold induction of the elongation rate by Paf1C (Fig. 2D). The magnitude of activation observed here is comparable with data published recently using the transcription elongation factor NusG in the presence of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase (26). Because in vitro and in vivo conditions cannot be compared directly, it is not surprising that the magnitude of activation observed here is different from the ∼3-fold effect calculated previously (7). These data demonstrate that Paf1C can directly enhance Pol I transcription elongation in the absence of accessory elongation factors or chromatin.

Pol I Transcription Is Less Responsive to Nutrient Limitation in paf1Δ Cells

The above data indicated that Paf1C plays an important positive role in Pol I transcription elongation. Previous reports have suggested that regulation of Pol I loading on rDNA does not fully explain the magnitude of regulation of rRNA synthesis observed after various growth challenges (3, 27). Thus, we tested whether Paf1C may play a role in regulation of rRNA synthesis in response to nutrient limitation.

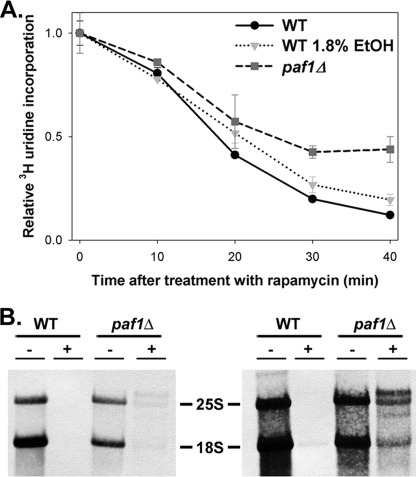

Because TOR is a central nutrient signaling pathway in eukaryotes (28), we measured Pol I transcription activity after inhibition of TOR signaling using rapamycin in WT and paf1Δ cells. Initially, we conducted [3H]uridine incorporation assays to determine total RNA synthesis rates. Because most RNA synthesis is derived from Pol I in exponentially growing cells, this is a useful method to approximate Pol I transcription. WT cells were sensitive to rapamycin treatment; the total RNA synthesis rate decreased by >90% over the 40-min time course (Fig. 3A). In contrast, [3H]uridine incorporation decreased by only ∼60% during the length of rapamycin treatment in the paf1Δ strain. These data suggest that Paf1p is required for efficient control of rRNA synthesis in response to nutrient conditions.

FIGURE 3.

Pol I transcription in paf1Δ cells is resistant to rapamycin treatment. A, relative RNA synthesis rates were measured using [3H]uridine incorporation ± rapamycin (0.2 μg/ml) in WT (NOY396) and paf1Δ (DAS516) strains. Both strains, carrying the pRS316 plasmid, were grown in SD−Ura medium to A600 ≈ 0.3. After labeling with [3H]uridine, cultures were treated with 10% trichloroacetic acid and unlabeled uridine. Samples were then filtered using nitrocellulose, washed, dried, and counted in a scintillation counter. To control for the effect of slow growth on rapamycin sensitivity, a WT strain grown in S-ethanol−Ura was included. Data were averaged from duplicate samples from two independent cultures with error (S.D.) shown. B, RNA was purified from cells pulse-labeled with [3H]methylmethionine ± treatment with rapamycin (0.2 μg/ml, 40 min). Total RNA was run on a 1% formaldehyde-agarose gel, transferred to a membrane, and visualized by autoradiography. Both 1-day and 1-week exposures of the same blot are shown with the positions of major rRNA species indicated.

The paf1Δ strain grows ∼3-fold slower than WT cells (7). To rule out the effect of slow growth rate on the responsiveness of Pol I transcription to rapamycin, we included the WT strain grown in medium with 1.8% ethanol as the sole carbon source instead of glucose. Under these conditions, the WT strain grew at approximately the same rate as the paf1Δ strain, and the Pol I transcription rate was similarly reduced. However, unlike in the paf1Δ strain, Pol I transcription remained responsive to rapamycin treatment in WT cells grown in ethanol (Fig. 3A). Thus, the altered sensitivity to rapamycin in the paf1Δ strain is not simply a consequence of decreased growth rate.

To specifically measure changes in the Pol I transcription rate, we pulse-labeled WT and paf1Δ cells using [3H]methylmethionine in the absence of rapamycin and after a 40-min treatment. Because rRNA is cotranscriptionally methylated in yeast, this method permits accurate quantification of Pol I transcription rates in vivo using short pulse times (29). After chasing with unlabeled methionine, RNA was isolated, and [3H]methylmethionine incorporation into 25 S and 18 S rRNAs was visualized by autoradiography. In the absence of rapamycin, we observed a reduction in the Pol I transcription rate in the paf1Δ mutant compared with WT cells (Fig. 3B). This observation is consistent with our published observations (7). After treatment with rapamycin, Pol I transcription was below our level of detection in WT strains; however, the Pol I transcription rate in the paf1Δ strain was clearly detectable above background levels especially after 7 days of exposure (Fig. 3B). These data confirm that Paf1C function is required for the efficient response of Pol I transcription to the inhibition of TOR signaling.

We also observed defects in rRNA processing in the paf1Δ mutant in the presence of rapamycin. There was a significant accumulation of 27 S and 23 S rRNAs (Fig. 3B) even after the 5-min chase with unlabeled methionine. Previous studies demonstrated that without rapamycin treatment, the paf1Δ mutant exhibits modest rRNA-processing defects (7, 11). The present data show that rapamycin aggravated the processing defects in paf1Δ cells. These data are consistent with the model that Pol I transcription elongation is coupled to rRNA processing, and Paf1C plays important roles in both processes (25).

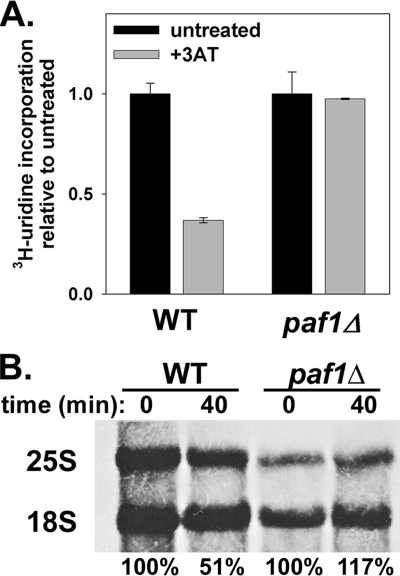

In yeast, starvation for any one of 10 amino acids induces “general amino acid control” (30). 3-AT is a competitive inhibitor of the HIS3 gene product and was used to simulate cell starvation for histidine. We found that transcription in the paf1Δ mutant was insensitive to 3-AT treatment, whereas total RNA synthesis was reduced by ∼3-fold in WT cells (Fig. 4A). Pulse labeling rRNA with [3H]methylmethionine revealed an ∼2-fold reduction of Pol I transcription in WT cells in the presence of 3-AT relative to untreated cells but no decrease in Pol I transcription in paf1Δ cells relative to control cells (Fig. 4B). Thus, Paf1p is also required for control of Pol I transcription in response to amino acid starvation.

FIGURE 4.

Pol I transcription in paf1Δ cells is resistant to 3-AT treatment. A, relative RNA synthesis rates were measured using [3H]uridine incorporation ± 3-AT (10 mm, 40 min) in WT (NOY396) and paf1Δ (DAS516) strains. Strains were made His+ and Ura+ by transformation with pRS313 and pRS316, respectively. Both strains were grown in SD−His−Ura medium to A600 ≈ 0.3. Samples were processed and quantified as described for Fig. 3. Data were averaged from duplicate samples from two independent cultures with error (S.D.) shown. B, RNA was purified from cells pulse-labeled with [3H]methylmethionine ± 3-AT (10 mm, 40 min). Total RNA was run on a 1% formaldehyde-agarose gel, transferred to a membrane, and visualized by autoradiography. 18 S and 25 S RNA bands were excised and counted in a scintillation counter. After correction for minimal background signal, 18 S and 25 S data were added together and expressed as a percentage of the untreated signal.

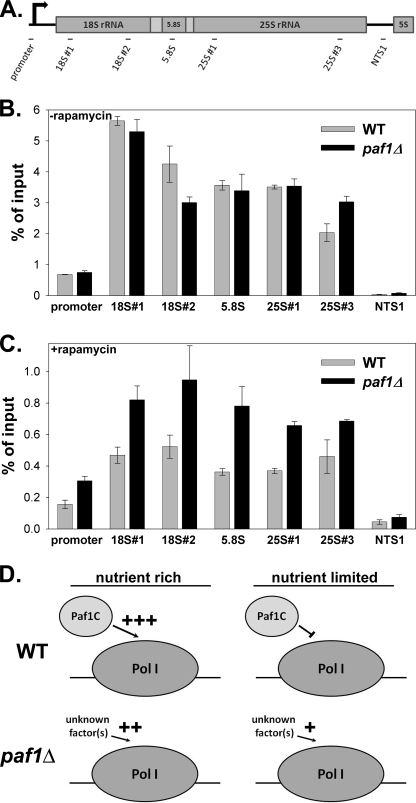

Model for Nutritional Control of Paf1C Activity at the rDNA

We measured Pol I occupancy of the rDNA in WT and paf1Δ cells in the absence and presence of rapamycin using ChIP. As described previously (by ChIP and electron microscopy) (7), we did not observe a decrease in the ChIP signal for Pol I over the rDNA in the paf1Δ mutant in the absence of rapamycin (Fig. 5B), despite the ∼3-fold lower rRNA synthesis rate in these cells. However, after a 40-min exposure to rapamycin, Pol I loading on the rDNA was reduced by ∼3–6-fold in the WT strain (depending on which rDNA region was analyzed) (Fig. 5, B and C). This observation is consistent with previous work demonstrating that Rrn3p-dependent recruitment of Pol I to the promoter is reduced in response to rapamycin (3). Surprisingly, in the paf1Δ strain, the occupancy of Pol I over the rDNA remained higher than in the WT strain after rapamycin treatment (Fig. 5C). This increase in Pol I loading at least partially explains the elevated rRNA synthesis observed in the paf1Δ strain after treatment with rapamycin (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 5.

Paf1C function is required to reduce activity by Pol I in the presence of rapamycin. A, diagram of primer pairs used in real-time PCR analysis of ChIP data. B, Pol I occupancy over the rDNA as measured by ChIP. WT (NOY396) and paf1Δ (DAS516) cells were grown to mid-log phase in SD complete medium, harvested, and analyzed as described (7). Each bar represents the average of three 10-fold dilutions of immunoprecipitated DNA expressed as a percentage of total input DNA. Error bars represent ±1 S.D. C, Pol I occupancy of rDNA in WT (NOY396) and paf1Δ (DAS516) cells measured by ChIP after treatment with rapamycin (0.2 μg/ml, 40 min). Data were analyzed as described for B. D, model for the role of Paf1C in the activation and regulation of Pol I transcription.

From these data, we can propose a model for the role of Paf1C in the regulation of Pol I activity (Fig. 5D). Under normal growth conditions in WT cells, Paf1C increases the transcription elongation rate by Pol I; however, under nutritional stress, we propose that this activity is decreased, contributing to the overall reduction of the rRNA synthesis rate (Figs. 3 and 4) despite robust Pol I binding over the rDNA (Fig. 5C). In paf1Δ cells, the activation of the Pol I elongation rate is partially lost; thus, we propose that other (as yet unidentified) cellular factors are induced to partially overcome the loss of Paf1C function (Fig. 5D). Because these feedback-induced factors are not fully sensitive to repression by rapamycin, Pol I synthesis remains detectable after treatment (Fig. 3B). Although many indirect mechanisms are possible, this is the simplest model that accounts for all of the observed data.

DISCUSSION

Mechanism by Which Paf1C Affects Pol I Transcription

Previous reports have identified synthetic lethal interactions between deletions of genes encoding Paf1C subunits and deletions of other Pol II transcription elongation factors or subunits of Pol II (14, 15, 31). These data support the role(s) of Paf1C in Pol II transcription. Similarly, we have shown that deletion of PAF1 or CTR9 leads to severe synthetic growth defects in combination with the rpa49Δ mutation. Because the A49 subunit of Pol I has been implicated in transcription elongation by the enzyme, these data support the model that Paf1C plays a role in Pol I transcription elongation.

We did not observe any synthetic growth defects in double mutants of rpa49Δ and cdc73Δ, leo1Δ, or rtf1Δ. This observation is not surprising, given the less severe phenotype of these mutations (7, 11). However, we did observe occupancy of the rDNA by Leo1p and Cdc73p (Rtf1p was not tested) (7). The lack of synthetic interaction described here does not exclude these proteins from functioning in Pol I transcription; however, these data at least suggest that other cellular mechanisms can compensate for the loss of function of Cdc73p, Leo1p, or Rtf1p at the rDNA. Alternatively, it is possible that the predominant roles for Cdc73p, Leo1p, and Rtf1p may be in Paf1C function at mRNA-encoding genes rather than at the rDNA. Further studies are required to differentiate these possibilities.

Our in vitro analysis demonstrated that Paf1C can increase the transcription elongation rate of Pol I through a naked rDNA template. Because our system contains only essential transcription initiation factors and the polymerase, it is likely that Paf1C must directly contact Pol I to enhance the kinetics of elongation (perhaps through allosteric changes in the enzyme). Such a mechanism would be consistent with the previous observation that cell extracts made from WT but not paf1Δ or cdc73Δ strains could increase the rate of Pol II transcription elongation through naked DNA (17). Although the use of cell extracts precluded differentiation between direct and indirect effects, the work by Rondón and co-workers (17) is consistent with the data shown here. Recent work of Handa and co-workers (16) demonstrated that purified Paf1C from human cells also stimulates Pol II transcription elongation in vitro. Thus, as originally proposed (32), Paf1C can directly communicate with the RNA polymerase (I or II) and enhance transcription elongation.

We added only purified Paf1C to our transcription elongation assays shown in Fig. 2. Handa and co-workers (16) did not observe any activation of human Pol II transcription elongation by Paf1C unless hSpt4p/hSpt5p (also called DSIF) was also added to the reactions. There are at least two reasonable explanations for this discrepancy. The reaction conditions used by Handa and co-workers were more restrictive than those used here. In the absence of elongation factors, they observed no significant elongation through their template. We used higher nucleotide triphosphate concentrations and a shorter template, and we observed efficient transcription elongation with only pure initiation factors and Pol I (Fig. 2). Thus, our assay is more sensitive to small changes in elongation rate. Alternatively, Pol II may be less responsive to Paf1C than Pol I, perhaps requiring additional factors (e.g. Spt4p/Spt5p). Irrespective of these minor differences, the data shown here, together with those of Rondón and co-workers (17) and Handa and co-workers, clearly demonstrate that Paf1C is capable of directly influencing the transcription elongation rate of RNA polymerases, independently of chromatin modifications.

We note that unlike Pol II, we did not detect stable co-immunoprecipitation of Paf1C with Pol I (data not shown), despite its association with the rDNA as detected with ChIP (7). There are at least two reasonable models to explain this observation. Perhaps Paf1C associates only with the elongating Pol I complex (thus, the interaction would be lost in solution/cell extracts). Alternatively, Paf1C may interact directly with all populations of Pol I, but the interaction may not be stable enough for co-purification. Irrespective of the nature of this interaction, it is apparent from the studies presented here and previously that Paf1C plays an important role in Pol I transcription elongation.

Regulation of Paf1C Activity in Response to Nutrient Conditions

We have shown that Paf1C can directly increase the rate of Pol I transcription elongation and that Paf1C is required for efficient control of Pol I activity in response to nutrient limitation. The simplest model to explain these data is that the activity of Paf1C is directly regulated by TOR signaling or amino acid limitation (Fig. 5D). The mammalian Pol I-specific factor upstream binding factor (UBF) is the only other protein that is known to directly regulate transcription elongation by Pol I. Moss and co-workers (6) showed that stimulation of serum-starved cells with growth factor increased the rate of Pol I transcription elongation. They also showed that UBF can inhibit transcription elongation by Pol I in vitro and that extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)-dependent phosphorylation of UBF relieved the inhibition. Perhaps Paf1C also undergoes covalent modification(s) in response to growth stimuli. The precise modifications that occur and how they relate to transcription by Pol I and Pol II are the focus of ongoing studies in our laboratory.

Relationship between Paf1C, Pol I, Tumorigenesis, and Stem Cell Development

The human homologs of PAF1 (PD2 (pancreatic differentiation 2) gene) (33) and Cdc73p (parafibromin, HRPT2) (34)) have been directly implicated in tumorigenesis (for review, see Ref. 35). Recently, another study identified a role for human Paf1C in maintaining pluripotent embryonic stem cell identity (36). This work demonstrated that Paf1C associated with promoters of genes important for pluripotency, potentially maintaining an active chromatin structure. Paf1C expression was reduced in early embryonic development, and its overexpression inhibited embryonic stem cell differentiation. The authors concluded that Paf1C likely plays an important role in the complex processes of embryonic stem cell growth and terminal differentiation. Given the capacity for tumor cells and stem cells to grow and proliferate and the central role of ribosome synthesis in these processes, perhaps Paf1C influences Pol I activity in mammalian cells as in yeast.

For the first time, we have shown that Paf1C plays an important direct role in transcription elongation by Pol I. We further demonstrate that Paf1C is required for efficient control of Pol I transcription in response to nutrient limitation. Although the molecular mechanisms by which Paf1C activity is regulated remain unknown, these studies clearly define a new important role for this conserved transcription factor in rRNA synthesis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Peter Detloff, Susan Anderson, and Olga Viktorovskaya for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant CA-13148-31 from NCI and Grant GM084946 (to D. A. S.). This work was also supported by American Cancer Society Grant IRG-60-001-47 and by University of Alabama at Birmingham institutional start-up funding from the Health Services Foundation-General Endowment Fund.

- Pol I

- RNA polymerase I

- Paf1C

- RNA polymerase-associated factor 1 complex

- 3-AT

- 3-aminotriazole

- WT

- wild-type

- HA

- hemagglutinin

- ChIP

- chromatin immunoprecipitation

- TOR

- target of rapamycin

- UBF

- upstream binding factor.

REFERENCES

- 1.Grummt I. (1999) Prog. Nucleic Acids Res. Mol. Biol. 62, 109–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nomura M., Nogi Y., Oakes M. (2004) in The Nucleolus ( Olson M. O. J., ed) pp. 128–153, Landes Bioscience, Georgetown, TX [Google Scholar]

- 3.Claypool J. A., French S. L., Johzuka K., Eliason K., Vu L., Dodd J. A., Beyer A. L., Nomura M. (2004) Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 946–956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fath S., Milkereit P., Peyroche G., Riva M., Carles C., Tschochner H. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 14334–14339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grummt I. (2003) Genes Dev. 17, 1691–1702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stefanovsky V., Langlois F., Gagnon-Kugler T., Rothblum L. I., Moss T. (2006) Mol. Cell 21, 629–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y., Sikes M. L., Beyer A. L., Schneider D. A. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 2153–2158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krogan N. J., Kim M., Ahn S. H., Zhong G., Kobor M. S., Cagney G., Emili A., Shilatifard A., Buratowski S., Greenblatt J. F. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 6979–6992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mueller C. L., Jaehning J. A. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 1971–1980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pokholok D. K., Hannett N. M., Young R. A. (2002) Mol. Cell 9, 799–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Porter S. E., Penheiter K. L., Jaehning J. A. (2005) Eukaryot. Cell 4, 209–220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Porter S. E., Washburn T. M., Chang M., Jaehning J. A. (2002) Eukaryot. Cell 1, 830–842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stolinski L. A., Eisenmann D. M., Arndt K. M. (1997) Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 4490–4500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qiu H., Hu C., Wong C. M., Hinnebusch A. G. (2006) Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 3135–3148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Squazzo S. L., Costa P. J., Lindstrom D. L., Kumer K. E., Simic R., Jennings J. L., Link A. J., Arndt K. M., Hartzog G. A. (2002) EMBO J. 21, 1764–1774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Y., Yamaguchi Y., Tsugeno Y., Yamamoto J., Yamada T., Nakamura M., Hisatake K., Handa H. (2009) Genes Dev. 23, 2765–2777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rondón A. G., Gallardo M., García-Rubio M., Aguilera A. (2004) EMBO Rep. 5, 47–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mueller C. L., Porter S. E., Hoffman M. G., Jaehning J. A. (2004) Mol. Cell 14, 447–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheldon K. E., Mauger D. M., Arndt K. M. (2005) Mol. Cell 20, 225–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adelman K., Wei W., Ardehali M. B., Werner J., Zhu B., Reinberg D., Lis J. T. (2006) Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 250–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krogan N. J., Dover J., Wood A., Schneider J., Heidt J., Boateng M. A., Dean K., Ryan O. W., Golshani A., Johnston M., Greenblatt J. F., Shilatifard A. (2003) Mol. Cell 11, 721–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu B., Mandal S. S., Pham A. D., Zheng Y., Erdjument-Bromage H., Batra S. K., Tempst P., Reinberg D. (2005) Genes Dev. 19, 1668–1673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wood A., Schneider J., Dover J., Johnston M., Shilatifard A. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 34739–34742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuhn C. D., Geiger S. R., Baumli S., Gartmann M., Gerber J., Jennebach S., Mielke T., Tschochner H., Beckmann R., Cramer P. (2007) Cell 131, 1260–1272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schneider D. A., Michel A., Sikes M. L., Vu L., Dodd J. A., Salgia S., Osheim Y. N., Beyer A. L., Nomura M. (2007) Mol. Cell 26, 217–229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mooney R. A., Schweimer K., Rösch P., Gottesman M., Landick R. (2009) J. Mol. Biol. 391, 341–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tongaonkar P., French S. L., Oakes M. L., Vu L., Schneider D. A., Beyer A. L., Nomura M. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 10129–10134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wullschleger S., Loewith R., Hall M. N. (2006) Cell 124, 471–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Warner J. R. (1991) Methods Enzymol. 194, 423–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hinnebusch A. G. (1988) Microbiol. Rev. 52, 248–273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Betz J. L., Chang M., Washburn T. M., Porter S. E., Mueller C. L., Jaehning J. A. (2002) Mol. Genet. Genomics 268, 272–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shi X., Finkelstein A., Wolf A. J., Wade P. A., Burton Z. F., Jaehning J. A. (1996) Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 669–676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moniaux N., Nemos C., Schmied B. M., Chauhan S. C., Deb S., Morikane K., Choudhury A., Vanlith M., Sutherlin M., Sikela J. M., Hollingsworth M. A., Batra S. K. (2006) Oncogene 25, 3247–3257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woodard G. E., Lin L., Zhang J. H., Agarwal S. K., Marx S. J., Simonds W. F. (2005) Oncogene 24, 1272–1276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chaudhary K., Deb S., Moniaux N., Ponnusamy M. P., Batra S. K. (2007) Oncogene 26, 7499–7507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ding L., Paszkowski-Rogacz M., Nitzsche A., Slabicki M. M., Heninger A. K., de Vries I., Kittler R., Junqueira M., Shevchenko A., Schulz H., Hubner N., Doss M. X., Sachinidis A., Hescheler J., Iacone R., Anastassiadis K., Stewart A. F., Pisabarro M. T., Caldarelli A., Poser I., Theis M., Buchholz F. (2009) Cell Stem Cell 4, 403–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Longtine M. S., McKenzie A., 3rd, Demarini D. J., Shah N. G., Wach A., Brachat A., Philippsen P., Pringle J. R. (1998) Yeast 14, 953–961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Renfrow M. B., Mackay C. L., Chalmers M. J., Julian B. A., Mestecky J., Kilian M., Poulsen K., Emmett M. R., Marshall A. G., Novak J. (2007) Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 389, 1397–1407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chalkley R. J., Baker P. R., Medzihradszky K. F., Lynn A. J., Burlingame A. L. (2008) Mol. Cell. Proteomics 7, 2386–2398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nesvizhskii A. I., Keller A., Kolker E., Aebersold R. (2003) Anal. Chem. 75, 4646–4658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]