Abstract

Purpose

To determine by pharmacokinetic (PK) means the role of erythropoietin-receptor (EPO-R) upregulation in fetuses on the elimination of erythropoietin (EPO).

Materials and Methods

Six fetal sheep were catheterized at a gestational age of 125–127 days and phlebotomized daily for 6 days. Paired tracer PK studies using recombinant human EPO (rHuEPO) were conducted in the sheep fetuses at baseline and post-phlebotomy, 7 days later. A PK model with Michaelis-Menten elimination was simultaneously fit to the PK data at baseline and post-phlebotomy for each fetus.

Results

Daily phlebotomies reduced the hemoglobin levels from baseline values of 10.8 (5%) (mean (C.V.)) g/dl to a nadir of 4.5 (17%) g/dl post-phlebotomy. The endogenous EPO concentration rapidly increased after the first phlebotomy and remained elevated, although variable, thereafter. The Michaelis-Menten maximal rHuEPO elimination rate parameter, Vmax, was significantly greater post-phlebotomy than at baseline (p < 0.05), increasing 1.31 fold. The fetal baseline “linear” clearance at very low concentrations of rHuEPO was determined to be 117 ml/kg/h, similar to that determined in newborn sheep but 2–3 fold higher than that determined in adult sheep.

Conclusions

The observed increase in Vmax is consistent with an up-regulation of EPO-R due to a positive feedback resulting from the phlebotomy-induced anemia.

Keywords: developmental comparison, erythropoietin receptors, fetus, pharmacokinetics, receptor regulation

INTRODUCTION

Erythropoietin (EPO) is a 35 kD glycoprotein hormone produced by the pertibular cells of the kidney in response to oxygen need (1). It is an obligate growth factor for developing erythroid cells, the primary function of which is to regulate erythrocyte production by preventing apoptosis and stimulating proliferation of erythroid progenitor cells (BFU-Es and CFU-Es) (1,2). EPO exerts its erythropoietic effects by binding to specific cell surface erythropoietin receptors (EPO-R) on erythroid progenitor cells primarily residing in the bone marrow (1). EPO-Rs have also been identified in many other tissues, but at much lower receptor densities than that observed for BFU-E and CFU-E cells (3). In non-erythroid cells, e.g., brain, heart, kidney, and other tissues, stimulation of EPO-R by its ligand, EPO, exerts a protective role by attenuating ischemic injury and inflammatory cytokines (4).

The number of EPO-Rs per cell and the number of erythroid cells with EPO-Rs increases through ligand-induced receptor upregulation as EPO stimulates the proliferation and maturation of progenitor cells (1,5), thereby increasing the erythroid cell mass (6,7) and further amplifying ligand-induced receptor upregulation. Additionally, upon binding to EPO-Rs on cell surfaces, EPO is internalized and a substantial fraction is degraded in the lysosomes (8–10). Therefore, it is likely that receptor-mediated elimination plays an important role in EPO disposition (11,12), with EPO stimulation inducing its own increased elimination through the increased erythroid cell mass and receptor number as a result of continued EPO stimulation (13). In support of this are several in vivo studies demonstrating that continued EPO stimulation either through anemia or exogenous recombinant human EPO (rHuEPO) administration increases EPO clearance (14–18). Removal of the EPO-R in the bone marrow through chemical ablation has also demonstrated decreased EPO clearance, providing additional evidence of receptor mediated elimination (19,20). Finally, clinical studies in humans have demonstrated increased levels of circulating EPO when the marrow activity or mass is reduced (17,21–23).

In human fetuses EPO-R is widely expressed in many cell types throughout the body (24). In adults EPO-R and its mRNA are also distributed in many tissues besides the bone marrow, but to date it has not been identified in as many tissues as in the fetus (3,25). Consistent with wider EPO-R distribution in the fetus and receptor mediated EPO elimination, fetal and neonatal sheep and infants have been shown to have greater EPO clearances than adults (26,27). While the EPO-R distribution has been studied in adults and fetuses, the contribution of receptor mediated clearance has thus far only been studied in adult and newborn animals (14,17,18, 20). Thus, the objective of the current study was to determine by pharmacokinetic means the in vivo role of EPO-R upregulation in fetuses on the elimination of exogenously administered rHuEPO. We hypothesize that in fetuses under conditions of EPO-R upregulation the EPO elimination capacity will be significantly increased relative to baseline conditions. To test this hypothesis, paired tracer interaction method (TIM) pharmacokinetic (PK) (28) studies of 125I-labeled rHuEPO (125I-rHuEPO) were conducted in fetal sheep both before and after 6 days of chronic daily phlebotomy. TIM is a sensitive methodology developed in our laboratory for accurately identifying and quantifying a nonlinear PK disposition process which has been previously identified for EPO in sheep and humans (15,17,18,20,28–31). A two compartment model with central Michaelis-Menten elimination kinetics was incorporated in the TIM methodology and the resulting PK parameters compared at baseline and post-phlebotomy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

All animal care and experimental procedures were approved by the University of Iowa Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Six healthy fetal sheep ranging in approximate gestational age of 125–127 days, with term being 145 days, and having an estimated weight of 2.56 (28%) kg (mean (C.V.)) at study initiation were selected. Gestational ages were estimated based on the induced ovulation technique as previously described (32). Fetal weights were estimated by linear back extrapolation of fetal growth curves from the fetal weight at sacrifice. If ewes were carrying twin or triplet fetuses, only one fetus was studied. Pregnant ewes were housed in an indoor, light- and temperature-controlled environment with ad lib access to feed and water. Prior to PK study, fetuses were surgically prepared as described previously (33). In brief, pregnant ewes were fasted for 24 h prior to anesthesia induction with thiopental sodium. Anesthesia was maintained with a mixture of halothane (1%), oxygen (33%), and nitrous oxide (66%). Under sterile conditions, a maternal left flank incision was made and the uterus exposed. The uterus was opened, the fetal extremities exposed, and polyethylene catheters inserted bilaterally in the fetal femoral arteries and veins. Uterine and maternal incisions were closed in separate layers. All catheters were exteriorized through a subcutaneous tunnel and placed in a cloth pouch on the ewe’s flank. Following surgery, amipicillin was directly infused into the amniotic cavity (2 g) and administered intramuscularly (2 g) to the ewe. The antibiotic administration was continued for 3 days post-surgery, after which the study protocol was initiated.

Study Protocol

Paired TIM studies were conducted on each fetus, consisting of one baseline TIM study prior to any phlebotomies (day 0), and a second post-phlebotomy TIM study seven days later (day 7) after daily phlebotomies. Twenty to ninety milliliters of blood were removed at each daily phlebotomy, for a total mean hemoglobin (Hb) removal of 24.6 (33%) g from day 1 through day 6. To assist in maintaining a relatively constant blood volume during the phlebotomies, an equal volume 0.9% NaCl solution was infused for each volume of blood removed. Prior to each daily phlebotomy, blood samples were collected to determine the endogenous plasma EPO, Hb, and reticulocyte count concentration. A detailed description of the theory and principles of the TIM methodology has been published previously (28). In brief, the TIM methodology is a sensitive method to detect and accurately quantify nonlinear pharmacokinetics using an infusion of tracer quantities of the labeled compound of interest and a single large unlabeled dose of the same compound. Each TIM study consisted of an intravenous (IV) 125I-rHuEPO constant rate infusion (CRI) at tracer levels preceded by an IV 125I-rHuEPO loading dose. Then, approximately 2–3 h after initiation of the CRI when plasma concentrations are near steady-state, a 100 U/kg IV rHuEPO bolus dose was administered. For each TIM study, approximately 25–30 venous blood samples (~1 ml/sample) were collected over the 8–10 h of the infusion. Bolus doses and the infusion were administered via a separate catheter from the catheter blood samples were collected. The specific activity of the utilized 125I- rHuEPO was approximately 1.4 × 106 cpm/U. No iron supplementation other than that in the ewe’s feed was given. To minimize Hb loss due to frequent blood sampling in the TIM studies, blood was centrifuged, the plasma removed, and the RBCs re-infused for all TIM study samples. Fetuses and pregnant ewes were sacrificed 1 day after the post-phlebotomy TIM study to obtain fetal sacrifice weights.

Sample Analysis

Plasma exogenous rHuEPO and endogenous sheep EPO concentrations were measured in duplicate using a double antibody radioimmunoassay (RIA) procedure as previously described (lower limit of quantitation 1 mU/ml) (26). Plasma 125I- rHuEPO concentrations were measured in duplicate using a sensitive and specific immunoprecipitation assay (IPA) developed in our laboratory (34). Hemoglobin concentrations were measured spectrophotometrically using an IL482 CO-oximeter (Instrumentation Laboratories, Watham, MA) and reticulocyte count concentrations were measured using an Advia 120 hematology analyzer (Bayer Corp., Tarrytown, NY).

Data Analysis

The plasma 125I-rHuEPO concentrations were analyzed according to the TIM-based PK model (28) given by differential Eqs. 1 and 2 below:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where CL and CU are the 125I-rHuEPO (labeled, in cpms/ml) and rHuEPO (unlabeled, in mU/ml) plasma concentrations, respectively, Z is a variable that is introduced to mathematically account for convolution due to a distribution effect, R is the infusion rate, k12 and k21 are the first order rate constants of distribution, V is the apparent volume of distribution, Vmax and km are the Michaelis-Menten terms of EPO elimination, DL is the bolus 125I-rHuEPO loading dose, and t0 is the initial time of the study start. The plasma rHuEPO concentrations were nonparametrically represented using a generalized cross validated cubic spline function (35). For samples drawn prior to administration of rHuEPO the mean endogenous EPO concentration was used for CU in Eq. 1. The mU/ml contribution of the tracer 125I-rHuEPO infusion can be ignored in the denominator of the Michaelis-Menten elimination term of Eq. 1 due to the very low concentrations of 125I-rHuEPO (<1 mU/ml). The plasma 125I-rHuEPO concentrations were modeled by fitting Eqs. 1 and 2 simultaneously to both the baseline and post-phlebotomy plasma 125I-rHuEPO concentration-time data of each subject. A separate V and Vmax term were estimated at baseline and post-phlebotomy. The separate V terms allow for changes in the volume of distribution as the fetus grows and/or miscalculation in the fetus weight. The separate Vmax terms allows for an increased EPO clearance through EPO-R upregulation post-phlebotomy (i.e. receptor mediated clearance). Other similar models with different combinations of separate and shared V, Vmax, and km terms at baseline and post-phlebotomy were also fitted to the data. The final model was selected based on residual analysis and Akaike’s Information Criterion (36).

Due to the nonlinear elimination of EPO (17–28) and the subsequently utilized model (Eqs. 1 and 2), the clearance of EPO is not a constant parameter but instead is a function of the EPO concentration. However, a “linear” clearance parameter can be calculated at “very low” concentrations of EPO, i.e. in the linear concentration range, defined as concentrations much lower than the km value (i.e. CL≪km) giving:

| (3) |

This “linear” clearance (Cl) parameter is reported only for comparison to other published work (18,20).

All modeling was conducted using WINFUNFIT, an interactive Windows (Microsoft) version evolved from the general nonlinear regression program FUNFIT (37). Ordinary least squares regression was used. Determined parameters were compared at baseline and post-phlebotomy using a nonparametric one-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test for Vmax, and a two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test for V. The Cl and V values determined in fetal sheep at baseline and post-phlebotomy were compared to that determined in newborn and adult sheep using a 2-sided Student’s t-test with unequal variance. Statistically significant differences were determined at the α = 0.05 type I error rate.

RESULTS

The mean plasma endogenous EPO, whole blood Hb, and blood reticulocyte count concentrations for the six fetuses over the course of the study are displayed in Fig. 1. The daily phlebotomies caused a 58% decrease in Hb concentration from a baseline, i.e., from 10.8 (5%) (mean (C.V.)) g/dl at day 0 to 4.5 (17%) g/dl at day 7. The endogenous EPO concentrations rapidly increased within a day of the first phlebotomy from a baseline of 21.2 (108%) mU/ml and then remained elevated and highly variable throughout the remainder of the study. The reticulocyte counts gradually increased after the phlebotomies began from a baseline value of 88.1 (66%) × 103 cells/μl. The baseline values of EPO and Hb in the fetal sheep are very similar to that observed in adult sheep (38–40). The observed baseline EPO concentration is somewhat higher than that previously determined in fetal sheep of 7.1 mU/ml and lower than that observed in newborn sheep of 55.2 mU/ml, while the observed Hb value is similar to that previously observed in fetuses and newborns (26).

Fig. 1.

Endogenous plasma EPO (□), Hb (•), and reticulocyte ( ) count concentrations from the baseline TIM study (day 0) to the post-phlebotomy TIM study (day 7). Daily phlebotomies were performed from day 1 through day 6. Values are mean ± standard error (n = 6).

) count concentrations from the baseline TIM study (day 0) to the post-phlebotomy TIM study (day 7). Daily phlebotomies were performed from day 1 through day 6. Values are mean ± standard error (n = 6).

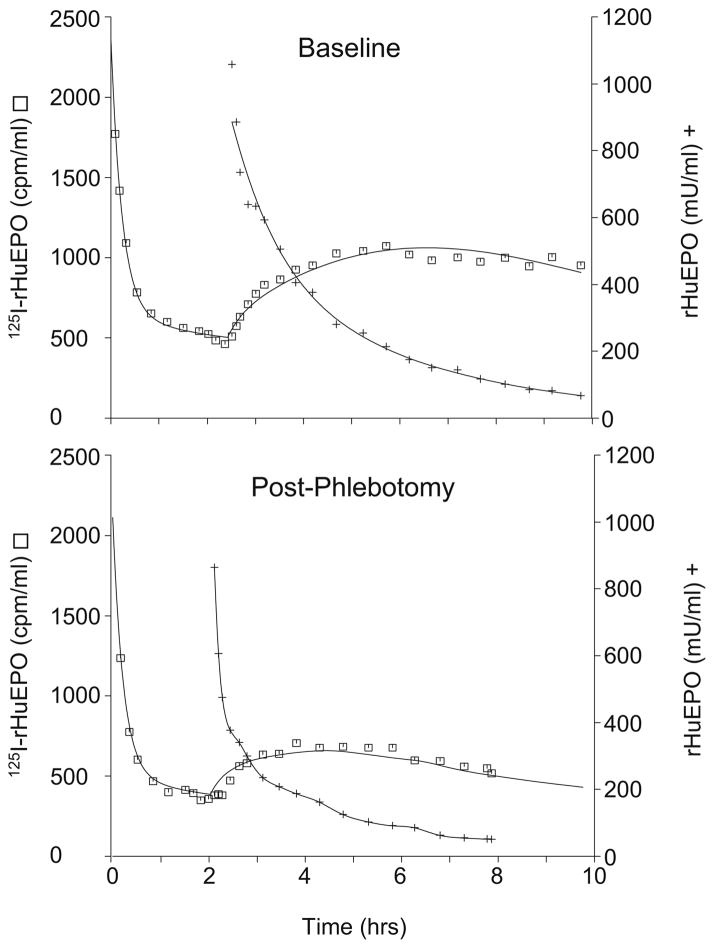

Nonparametric and parametric model fits to the rHuEPO and 125I-rHuEPO plasma concentrations, respectively, for a representative study animal is displayed in Fig. 2. As can be observed from the representative plot, the fitted model showed good agreement with the data (r = 0.980). 125I-rHuEPO plasma concentrations reached near steady-state conditions immediately prior to 100 U/kg bolus dose administration of unlabeled rHuEPO (to reach steady state is not critical for the TIM analysis). The bolus dose administration caused a substantial perturbation in the 125I-rHuEPO kinetics, indicating non-linearity in the fetal EPO disposition. As illustrated in Fig. 2, qualitatively the magnitude of the perturbation of the 125I-rHuEPO kinetics upon bolus dose rHuEPO administration is reduced in the anemic post-phlebotomy TIM study compared to the baseline TIM study.

Fig. 2.

Fit (lines) to plasma 125I-rHuEPO (□) and rHuEPO (+) concentration-time data for a representative study animal.

The PK model parameters from the six study animals are summarized in Table I. The volume of distribution (V) at baseline and post-phlebotomy were not significantly different (p = 0.20), with an overall mean of 122 (17%) ml/kg. The maximal estimated EPO elimination rate (Vmax) post-phlebotomy was 161 (62%) mU/ml/hr. The post-phlebotomy Vmax was significantly greater than the estimated Vmax at baseline of 123 (52%) mU/ml/h (p < 0.05). The increase in the Vmax term post-phlebotomy is consistent with the observed reduced perturbation of 125I-rHuEPO kinetics upon bolus dose rHuEPO administration, because with a single km value, as the Vmax term increases the elimination rate at a given EPO concentration is increased. The common km value was estimated at 147 (93%) mU/ml.

Table I.

PK Model Parameter Summary (n=6)

| V (ml/kg) | Vmax (mU/ml/h) | kma (mU/ml) | k12a (1/h) | k21a (1/h) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (Mean (C.V.)) | 116 (19%) | 123 (52%) | 147 (93%) | 1.12 (53%) | 1.04 (61%) |

| Post-phlebotomy (Mean (C.V.)) | 128 (16%) | 161* (62%) | 147 (93%) | 1.12 (53%) | 1.04 (61%) |

Parameter shared at baseline and post-phlebotomy (see Data Analysis section for details).

Significantly different from baseline (p < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Similar to adult and newborn sheep and humans, EPO in fetal sheep demonstrated non-linear pharmacokinetics (15,18) that were adequately described by Michaelis-Menten elimination mechanism (17,20,28–31). The daily phlebotomies resulted in a decrease in the mean Hb concentrations and an increase in the Vmax, which represents the rHuEPO elimination capacity (Fig. 1 and Table I). The estimated mean maximal elimination rate increased 1.31 fold post-phlebotomy. The Vmax term most likely increased post-phlebotomy due to EPO induced EPO-R upregulation caused by the high circulating levels of endogenous EPO produced from the anemia (13). Given the wide distribution of EPO-R in fetuses though (24), the proposed upregulation of EPO-R may be occurring in both erythropoietic and non-erythropoietic tissues. The increased Vmax and endogenous EPO concentration, along with the observed reticulocyte response, suggests that the fetus has the ability to increase the rate of erythropoiesis when necessary (Fig. 1). The phlebotomy/EPO induced affects on rHuEPO elimination can also be observed in Fig. 2, as the perturbation of the 125I-rHuEPO plasma concentrations upon administration of the large exogenous rHuEPO dose is reduced post-phlebotomy, indicating an increased elimination rate of rHuEPO as occurs when the Vmax is increased. The observed reduced perturbation in the plasma 125I-rHuEPO concentrations post-phlebotomy occurred even though the endogenous EPO concentrations were 6-fold higher relative to the baseline TIM study at the time of the post-phlebotomy TIM study (and well above the km value). This high EPO concentration would at least partially obscure the increased elimination capacity through partial saturation of the Michaelis-Menten elimination, which without an opposing increase in Vmax would increase the perturbation in the plasma 125I-rHuEPO concentrations post-phlebotomy.

Like in the current fetal sheep study, in adult sheep the phlebotomy induced increase in EPO, and the hypothesized subsequent increase in EPO-R, results in an increased nonlinear elimination of rHuEPO (17). The total fetal “linear” clearance (Cl) of rHuEPO at baseline, as calculated by Eq. 3, is 117 (37%) ml/h/kg, which is the same as that determined previously in newborn sheep of 118 ml/h/kg (p = 0.96) (20), and about 2 to 3-fold higher to that similarly determined in adult sheep of 45.6 ml/h/kg (p < 0.05) (18) (Table II). The fetal volume of distribution (V) at baseline and post-phlebotomy (116 and 128 ml/kg, respectively), is higher than that determined in newborn sheep of 74.4 ml/kg (p < 0.05) (20), and that determined in adult sheep of 52.3–57.6 ml/kg (p < 0.05)(18) (Table II). The higher V for fetal sheep is hardly surprising though, since the fetal blood volume also includes the blood volume of the placenta (41). In both fetal and adult sheep, phlebotomy increased the Cl relative to baseline, but had no effect on the V (18). The fetal Cl increased relative to baseline 1.36-fold post-phlebotomy to 159 ml/h and the adult Cl increased 1.98-fold 8 days post-acute phlebotomy to 90.2 ml/h. However, unlike at baseline, the difference in the rHuEPO clearance values between fetuses and adults post-phlebotomy did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.10). Differences in the fetal and adult Cl values post-phlebotomy may be at least partially obscured by different methods of anemia induction in these studies, chronic vs. acute, respectively. Like newborn sheep, it appears that under non-erythropoietic stimulated conditions that fetal sheep have a higher EPO clearance than adult sheep.

Table II.

Pharmacokinetic Parameter Comparison of Fetal, Newborn, and Adult Sheep

Pharmacokinetic analysis of the EPO-R population in newborn and adult sheep has also been studied by removal of the bone marrow fraction of the EPO-R pool through chemical bone marrow ablation (20). That study indicated that newborn sheep, like adults, have a substantial fraction of the EPO elimination occurring in the bone marrow, presumably through EPO-R located primarily on erythroid cells located in the marrow. The study also indicates that the fraction of elimination occurring in the bone marrow for newborn sheep is less than that observed for adult sheep. This may partially explain why the relative increase in rHuEPO clearance in the fetuses (1.36-fold) is less than the relative increase in clearance in adults (1.98-fold) since a smaller fraction of EPO’s elimination pathway would be stimulated in the fetus if their physiology is similar to that of newborn sheep (18,20). Additionally, it may reflect different total body distribution of EPO-R in fetuses/neonates relative to adults (3,24,25). Alternatively, the difference may be due to the method of anemia induction, chronic verses acute phlebotomy(ies), respectively.

It is possible that the changes in the maximal elimination rate are purely due to developmental changes in the fetal erythropoiesis physiology, since no control (non-phlebotomized) fetuses were studied in the TIM experiments. Because of the relatively short 7-day interval between the TIM studies, this is unlikely. This speculation is further supported by the observed increase in endogenous EPO concentrations and by the baseline fetal “linear” clearance of rHuEPO being nearly identical to that observed in newborn lambs. Further studies with a control group are needed though to confirm that the maximum elimination rate does not change in fetuses over a short time interval when no phlebotomies are conducted. It is also possible that the anemia induced increased cardiac output to maintain oxygen delivery to tissues affects the EPO elimination rate (42). However, this is unlikely to occur since EPO is largely eliminated by tissues (i.e. bone marrow) that have a baseline high blood flow (42), and hence its elimination is most likely not blood flow limited (i.e. marrow blood flow is much greater than EPO clearance). Acute changes total blood volume could also occur immediately following the phlebotomy due to extra-vascular distribution of the isovolumetric saline administered. However, any resulting transient hypovolemia would likely be resolved within 24 h, i.e. prior to the post-phlebotomy TIM study, and therefore have minimal effect on the study results (43).

In an effort to assess the sensitivity of the hypothesis tests to the final selected model, conclusions drawn from other similar models that fitted the data reasonably well were compared to the conclusions reached with the reported model. Specifically, models that had a separate V, Vmax, and km terms or a single V term and separate Vmax and km terms at baseline and post-phlebotomy were analyzed. All models resulted in identical conclusions based on a Wilcoxon signed-rank test, that only the Vmax term was significantly different post-phlebotomy relative to baseline values.

Despite the rapid approximately 5-fold increase in endogenous EPO following the phlebotomies, the increase in reticulocyte count concentrations was delayed 2–3 days relative to the EPO increase (3–4 days post-phlebotomy) in the fetuses (Fig. 1). While there is a well recognized delay in reticulocyte production and release into the systemic circulation relative to EPO stimulation (44,45), in adult sheep the lag time between the phlebotomy and the reticulocyte increase following acute phlebotomy was only 0.2–2.0 days (40). The initial increase in reticulocyte count following a rapid increase in EPO concentrations is likely related to immature reticulocyte release from the bone marrow independent of its stimulating effects on erythropoiesis (46,47). Additionally, the baseline reticulocyte count of 88.1 × 103 cells/μl in the fetuses is substantially higher than that observed in adult sheep of 10.9 × 103 cells/μl (40), indicating either higher baseline erythropoiesis and/or a longer reticulocyte peripheral blood residence time in fetuses. When one considers the rapid growth rate of the fetus, the first of these two possibilities appears more likely. Therefore, the observed differences between adult and fetal sheep in their reticulocyte response relative to the EPO response may reflect inherent differences in EPO’s effect in fetal and adult bone marrow or a reduced capacity to release reticulocytes from the bone marrow in response to EPO since higher basal levels of erythropoiesis may limit the reticulocyte “pool” available for release. Alternatively, differences may also be related to the more gradual creation of anemia, and thus more gradual increase in EPO, in the present experiments.

CONCLUSION

In summary, the pharmacokinetics of EPO in fetal sheep were non-linear and well characterized by Michaelis-Menten elimination kinetics. Chronic phlebotomy of fetal sheep resulted in an increase in the circulating levels of endogenous EPO and an increase in the maximal elimination rate of rHuEPO, which is consistent with EPO induced receptor upregulation and receptor mediated elimination observed in other studies in the more mature animals. The observed increase in Vmax and the calculated “linear” clearance following phlebotomy is qualitatively similar to that observed in adult sheep, suggesting that the fetus, like the adult, has the reserve to increase the rate of erythropoiesis when necessary. Additionally, the clearance of rHuEPO in fetal sheep in the linear concentration range is quantitatively similar to that observed in newborn sheep and approximately half of that observed in adult sheep. Further in vivo studies that quantify the erythropoietic cellular mass and its EPO-R density are needed to confirm that the observed increase in Vmax following phlebotomy in fetal sheep is directly related to EPO-R upregulation and elimination, and not due to other pathways of elimination.

Acknowledgments

The rabbit antiserum used in the erythropoietin radio-immunoassay was a generous gift from Gisela K. Clemons, PhD. This work is supported by United States Public Health Service, National Institute of Health grants R01 HL-64770 (JLS) and P01 HL49625 (JAW).

ABBREVIATIONS

- 125I-rHuEPO

125I-labeled rHuEPO

- BFU-E

burst forming unit-erythroid

- CFU-E

colony forming unit-erythroid

- Cl

clearance at “very low” concentrations

- CL

plasma 125I- rHuEPO concentration in cpms/ml (labeled)

- CRI

constant rate infusion

- CU

plasma rHuEPO concentration in mU/ml (unlabeled)

- DL

IV bolus 125I- rHuEPO loading dose

- EPO

erythropoietin

- EPO-R

erythropoietin receptor

- Hb

hemoglobin

- IV

intravenous

- k12

first order rate constant of distribution out of the central compartment

- k21

first order rate constant of distribution into the central compartment

- km

plasma rHuEPO concentration where 50% of Vmax occurs

- PD

pharmacodynamic

- PK

pharmacokinetic

- R

IV infusion rate of 125I-rHuEPO

- RhuEPO

recombinant human erythropoietin

- t0

initial time

- TIM

tracer interaction method

- V

apparent volume of distribution

- Vmax

maximal rate of rHuEPO elimination

- Z

125I- rHuEPO distribution variable

References

- 1.Hoffman R, Benz EJ, Jr, Shattil SJ, Furie B, Cohen HJ, Silberstein LE, McGlave P. Hematology: Basic Principles and Applications. Elsevier; USA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fisher JW. Erythropoietin: physiology and pharmacology update. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2003;228:1–14. doi: 10.1177/153537020322800101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rossert J, Eckardt KU. Erythropoietin receptors: their role beyond erythropoiesis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:1025–1028. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brines M, Cerami A. Discovering erythropoietin’s extra-hematopoietic functions: biology and clinical promise. Kidney Int. 2006;70:246–250. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sawada K, Krantz SB, Dai CH, Koury ST, Horn ST, Glick AD, Civin CI. Purification of human blood burst-forming units-erythroid and demonstration of the evolution of erythropoietin receptors. J Cell Physiol. 1990;142:219–230. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041420202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adamson JW. Regulation of red blood cell production. Am J Med. 1996;101:4S–6S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(96)00160-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jandl JH. Blood: Textbook of Hematology. Little Brown; USA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sawyer ST, Krantz SB, Goldwasser E. Binding and receptor-mediated endocytosis of erythropoietin in Friend virus-infected erythroid cells. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:5554–5562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beckman DL, Lin LL, Quinones ME, Longmore GD. Activation of the erythropoietin receptor is not required for internalization of bound erythropoietin. Blood. 1999;94:2667–2675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sawyer ST, Hankins WD. The functional form of the erythropoietin receptor is a 78-kDa protein: correlation with cell surface expression, endocytosis, and phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6849–6853. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kato M, Kamiyama H, Okazaki A, Kumaki K, Kato Y, Sugiyama Y. Mechanism for the nonlinear pharmacokinetics of erythropoietin in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;283:520–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jelkmann W. The enigma of the metabolic fate of circulating erythropoietin (Epo) in view of the pharmacokinetics of the recombinant drugs rhEpo and NESP. Eur J Haematol. 2002;69:265–274. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0609.2002.02813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kato M, Kato Y, Sugiyama Y. Mechanism of the upregulation of erythropoietin-induced uptake clearance by the spleen. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:E887–E895. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1999.276.5.E887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kinoshita H, Ohishi N, Tokura S, Okazaki A. Pharmacokinetics and distribution of recombinant human erythropoietin in rats with renal dysfunction. Arzneim-Forsch/Drug Res. 1992;42(I):682–686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Widness JA, Veng-Pedersen P, Peters C, Periera LM, Schmidt RL, Lowe LS. Erythropoietin pharmacokinetics in premature infants: developmental, nonlinearity, and treatment effects. J Appl Physiol. 1996;80:140–148. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.80.1.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sans T, Joven J, Vilella E, Masdeu G, Farre M. Pharmacokinetics of several subcutaneous doses of erythropoietin: potential implications for blood transfusion. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2000;27:179–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Veng-Pedersen P, Chapel S, Al-Huniti NH, Schmidt RL, Sedars EM, Hohl RJ, Widness JA. Pharmacokinetic tracer kinetics analysis of changes in erythropoietin receptor population in phlebotomy-induced anemia and bone marrow ablation. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 2004;25:149–156. doi: 10.1002/bdd.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chapel SH, Veng-Pedersen P, Schmidt RL, Widness JA. Receptor-based model accounts for phlebotomy-induced changes in erythropoietin pharmacokinetics. Exp Hematol. 2001;29:425–431. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(01)00614-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chapel S, Veng-Pedersen P, Hohl RJ, Schmidt RL, McGuire EM, Widness JA. Changes in erythropoietin pharmacokinetics following busulfan-induced bone marrow ablation in sheep: evidence for bone marrow as a major erythropoietin elimination pathway. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;298:820–824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Veng-Pedersen P, Chapel S, Al-Huniti NH, Schmidt RL, Sedars EM, Hohl RJ, Widness JA. A differential pharmacokinetic analysis of the erythropoietin receptor population in newborn and adult sheep. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;306:532–537. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.052431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cazzola M, Guarnone R, Cerani P, Centenara E, Rovati A, Beguin Y. Red blood cell precursor mass as an independent determinant of serum erythropoietin level. Blood. 1998;91:2139–2145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beguin Y, Clemons GK, Pootrakul P, Fillet G. Quantitative assessment of erythropoiesis and functional classification of anemia based on measurements of serum transferrin receptor and erythropoietin. Blood. 1993;81:1067–1076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Klerk G, Rosengarten PC, Vet RJ, Goudsmit R. Serum erythropoietin (EST) titers in anemia. Blood. 1981;58:1164–1170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Juul SE, Yachnis AT, Christensen RD. Tissue distribution of erythropoietin and erythropoietin receptor in the developing human fetus. Early Hum Dev. 1998;52:235–249. doi: 10.1016/s0378-3782(98)00030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farrell F, Lee A. The erythropoietin receptor and its expression in tumor cells and other tissues. Oncologist. 2004;9(Suppl 5):18–30. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.9-90005-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Widness JA, Veng-Pedersen P, Modi NB, Schmidt RL, Chestnut DH. Developmental differences in erythropoietin pharmacokinetics: Increased clearance and distribution in fetal and neonatal sheep. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;261:977–984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown MS, Jones MA, Ohls RK, Christensen RD. Single-dose pharmacokinetics of recombinant human erythropoietin in preterm infants after intravenous and subcutaneous administration. J Pediatr. 1993;122:655–657. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)83559-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Veng-Pedersen P, Widness JA, Wang J, Schmidt RL. A tracer interaction method for nonlinear pharmacokinetics analysis: application to evaluation of nonlinear elimination. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1997;25:569–593. doi: 10.1023/a:1025765330455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramakrishnan R, Cheung WK, Wacholtz MC, Minton N, Jusko WJ. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic modeling of recombinant human erythropoietin after single and multiple doses in healthy volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;44:991–1002. doi: 10.1177/0091270004268411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Veng-Pedersen P, Widness JA, Pereira LM, Schmidt RL, Lowe LS. A comparison of nonlinear pharmacokinetics of erythropoietin in sheep and humans. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 1999;20:217–223. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-081x(199905)20:4<217::aid-bdd177>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Veng-Pedersen P, Widness JA, Pereira LM, Peters C, Schmidt RL, Lowe LS. Kinetic evaluation of nonlinear drug elimination by a disposition decomposition analysis. Application to the analysis of the nonlinear elimination kinetics of erythropoietin in adult humans. J Pharm Sci. 1995;84:760–767. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600840619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jennings JJ, Crowley JP. The influence of mating management on fertility in ewes following progesterone-PMS treatment. Vet Rec. 1972;90:495–498. doi: 10.1136/vr.90.18.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Segar JL, Bedell K, Page WV, Mazursky JE, Nuyt AM, Robillard JE. Effect of cortisol on gene expression of the renin-angiotensin system in fetal sheep. Pediatr Res. 1995;37:741–746. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199506000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Widness JA, Schmidt RL, Veng-Pedersen P, Modi NB, Sawyer ST. A sensitive and specific erythropoietin immunoprecipitation assay: application to pharmacokinetic studies. J Lab Clin Med. 1992;119:285–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hutchinson MF, deHoog FR. Smoothing noise data with spline functions. Numer Math. 1985;47:99–106. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Akaike H. Automatic control: A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans. 1974;19:716–723. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Veng-Pedersen P. Curve fitting and modelling in pharmacokinetics and some practical experiences with NONLIN and a new program FUNFIT. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1977;5:513–531. doi: 10.1007/BF01061732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chapel SH, Veng-Pedersen P, Schmidt RL, Widness JA. A pharmacodynamic analysis of erythropoietin-stimulated reticulocyte response in phlebotomized sheep. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;295:346–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Veng-Pedersen P, Chapel S, Schmidt RL, Al-Huniti NH, Cook RT, Widness JA. An integrated pharmacodynamic analysis of erythropoietin, reticulocyte, and hemoglobin responses in acute anemia. Pharm Res. 2002;19:1630–1635. doi: 10.1023/a:1020797110836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Al-Huniti NH, Widness JA, Schmidt RL, Veng-Pedersen P. Pharmacodynamic analysis of changes in reticulocyte subtype distribution in phlebotomy-induced stress erythropoiesis. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2005;32:359–376. doi: 10.1007/s10928-005-0009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brace RA. Blood volume and its measurement in the chronically catheterized sheep fetus. Am J Physiol. 1983;244:H487–H494. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1983.244.4.H487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guyton AC, Hall JE. Textbook of Medical Physiology. Saunders; Philadelphia: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hillman RS, Ault KA, Rinder HM. Hematology in Clinical Practice. McGraw-Hill; USA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pierre RV. Reticulocytes. Their usefulness and measurement in peripheral blood. Clin Lab Med. 2002;22:63–79. doi: 10.1016/s0272-2712(03)00067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brugnara C. Use of reticulocyte cellular indices in the diagnosis and treatment of hematological disorders. Int J Clin Lab Res. 1998;28:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s005990050011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Major A, Bauer C, Breymann C, Huch A, Huch R. Rherythropoietin stimulates immature reticulocyte release in man. Br J Haematol. 1994;87:605–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1994.tb08320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chamberlain JK, Weiss L, Weed RI. Bone marrow sinus cell packing: a determinant of cell release. Blood. 1975;46:91–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]