Abstract

Farnesol, a Candida albicans cell-cell signaling molecule that participates in the control of morphology, has an additional role in protection of the fungus against oxidative stress. In this report, we show that although farnesol induces the accumulation of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS), ROS generation is not necessary for the induction of catalase (Cat1)-mediated oxidative-stress resistance. Two antioxidants, α-tocopherol and, to a lesser extent, ascorbic acid effectively reduced intracellular ROS generation by farnesol but did not alter farnesol-induced oxidative-stress resistance. Farnesol inhibits the Ras1-adenylate cyclase (Cyr1) signaling pathway to achieve its effects on morphology under hypha-inducing conditions, and we demonstrate that farnesol induces oxidative-stress resistance by a similar mechanism. Strains lacking either Ras1 or Cyr1 no longer exhibited increased protection against hydrogen peroxide upon preincubation with farnesol. While we also observed the previously reported increase in the phosphorylation level of Hog1, a known regulator of oxidative-stress resistance, in the presence of farnesol, the hog1/hog1 mutant did not differ from wild-type strains in terms of farnesol-induced oxidative-stress resistance. Analysis of Hog1 levels and its phosphorylation states in different mutant backgrounds indicated that mutation of the components of the Ras1-adenylate cyclase pathway was sufficient to cause an increase of Hog1 phosphorylation even in the absence of farnesol or other exogenous sources of oxidative stress. This finding indicates the presence of unknown links between these signaling pathways. Our results suggest that farnesol effects on the Ras-adenylate cyclase cascade are responsible for many of the observed activities of this fungal signaling molecule.

Candida albicans is the most common fungal pathogen involved in life-threatening systemic infections (32). In the United States, candidemia is the fourth most common type of nosocomial bloodstream infection (5). Once C. albicans reaches the bloodstream, the immune system plays an important role in limiting candidiasis (51). Macrophages and neutrophils kill pathogenic cells using a combination of factors, including high levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (46). However, C. albicans has means by which it can resist being killed by phagocytic cells. If a yeast cell survives within a macrophage for a sufficient period of time, it can differentiate into a hypha that can pierce and kill the host cell, allowing the fungus to escape being killed (36). C. albicans resistance to oxidative (OX) stress is critical for survival within macrophages, and cells impaired in oxidative-stress defense show severely reduced infection capabilities (19).

C. albicans also frequently encounters OX stress during its commensal life. A number of the microorganisms that inhabit the same niches as C. albicans, such as lactobacilli (18, 60) and streptococci (20, 52), release large quantities of H2O2. Streptococcus sp. culture supernatants can have H2O2 concentrations approaching 10 mM (52). Its interactions both with the host immune system and with microbes within the human microflora have likely led C. albicans to acquire the ability to prepare for and survive OX stress. Recent investigations have demonstrated that C. albicans production of a small secreted signaling molecule, farnesol, may be one way that the fungus regulates factors necessary for survival in the presence of ROS (10, 65).

C. albicans-produced farnesol was first described as regulating, in a concentration-dependent manner, the morphological shifts between the yeast and hyphal forms of the fungus (26). However, farnesol has additional effects on C. albicans physiology (10, 11, 16, 45, 49, 57, 65). Westwater et al. (65) demonstrated that the pretreatment of C. albicans yeast cells with either C. albicans culture supernatants containing farnesol or exogenous farnesol led to increased survival of OX stress generated by H2O2, menadione, and plumbagin. The enhanced survival induced by farnesol was correlated with increased expression of genes involved in OX stress resistance, such as catalase and superoxide dismutase genes, but the mechanism for this protection was not described.

Farnesol has been reported to impinge on at least three central regulatory pathways that are directly or indirectly related to OX stress resistance (10, 30, 61). We previously reported that farnesol inhibits the Ras-cyclic AMP (cAMP)-protein kinase A (PKA) cascade, thereby inhibiting hyphal growth and inducing the expression of the catalase-encoding gene CAT1 (also called CTA1) (10). Although repression of the transcription of genes involved in stress response by the cAMP signaling pathway has been extensively documented (1, 24, 66), the mechanism for this repression is not yet well understood. In addition to farnesol effects on Ras1-Cyr1 signaling, Smith et al. (61) showed the Hog1 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase, which is involved in the response to high levels of OX stress by activating the transcription of stress-related genes, was phosphorylated in the presence of farnesol (8, 39). Lastly, the absence of the histidine kinase Chk1, a regulator of cell wall synthesis and filamentation (35, 49), renders strains more sensitive to OX stress than wild-type (WT) cells (7) and resistant to inhibition of filamentation by farnesol (30). The relationships between these pathways and their roles in farnesol-mediated protection against OX stress have not yet been described.

In addition to its effect on C. albicans signaling pathways, farnesol can induce ROS accumulation within C. albicans cells (57), which may protect against subsequent OX stress. The cause of ROS generation in response to farnesol is poorly understood. While farnesol is generally nontoxic to C. albicans (10, 26, 45), under certain conditions it can inhibit cell growth (31, 63) and induce cell death (31, 57). Although ROS are toxic at high concentrations, more and more reports indicate that they participate in intracellular signaling at lower concentrations (9). Subtoxic concentrations of H2O2 stimulate hyphal differentiation of C. albicans (42). Furthermore, pretreatment with a low level of ROS can protect against further OX stress in C. albicans (28).

Here, we test hypotheses regarding the mechanism by which farnesol protects against oxidative stress. While we observed that farnesol can induce ROS in C. albicans yeast from exponential-phase cultures, we show that the accumulation of ROS induced by farnesol is not necessary for protection against OX stress. We report data indicating that farnesol-mediated induction of catalase expression and ROS resistance in yeast occurs mainly by repression of the Ras1-cAMP pathway. Strains defective in this pathway did not show increased resistance to oxidative stress upon the addition of farnesol. In contrast, hog1/hog1 and chk1/chk1 mutants still exhibited increased resistance to H2O2 upon incubation with farnesol. While Hog1 was not necessary for farnesol-mediated protection against ROS, Hog1 phosphorylation increased in the presence of farnesol, as has been shown previously (61). We show that the disruption of Ras1 or Cyr1 signaling led to a marked increase in Hog1 phosphorylation even in the absence of farnesol, indicating the presence of undescribed links between the Ras1-cAMP and Hog1 MAP kinase pathways. Farnesol repression of the central Ras1-cAMP signaling pathway enables C. albicans to simultaneously control multiple traits relevant to virulence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

For a list of all strains used in these studies, refer to Table 1. Although the catalase-encoding gene (orf19.6229) has been referred to as CTA1 by Enjalbert et al. (13) and Davis-Hanna et al. (10), we refer to it here as CAT1 in accordance with the Candida Genome Database (CGD) nomenclature. Strains were streaked from freezer stocks stored at −80°C onto YPD (2% peptone, 1% yeast extract, and 2% glucose) plates every 8 days. Overnight cultures were grown in 5 ml of YPD at 30°C in a roller drum for 14 to 16 h. The cells were then centrifuged for 5 min and washed once with YPD.

Table 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Laboratory no. | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| SC5314 | Prototrophic clinical isolate | DH35 | 22 |

| CAI4 | Ura− derivative of SC5314 ura3::λimm434/ura3::λimm434 | DH332 | 33 |

| CAF2 | Ura+ derivative of CAI4 | DH331 | 33 |

| AH81 | Ura− derivative of CDH107 selected on 5-fluoroorotic acid ura3::λimm434/ura3::λimm434ras1Δ::hisG/ras1Δ::hisG | DH482 | This study |

| CDH107 (ras1/ras1) | ura3::λimm434/ura3::λimm434ras1Δ::hisG-URA3 hisG/ras1Δ::hisG | DH483 | 33 |

| CaAP16 (ras1/ras1/RAS1) | ura3::λimm434/ura3::λimm434ras1Δ::hisG/ras1Δ::hisG::FLAG-RAS1-URA3 | DH1383 | This study |

| CR216 (cyr1/cyr1) | ura3::λimm434/ura3::λimm434 | DH346 | 48 |

| cyr1Δ::hisG-URA3-hisG/cyr1Δ::hisG | |||

| RM100 | ura3::λimm434/ura3::λimm434 | DH1270 | 43 |

| CNC13 (hog1/hog1) | ura3::λimm434/ura3::λimm434 | DH1269 | 53 |

| his1Δ::hisG/his1Δ::hisG | |||

| hog1Δ::hisG-URA3-hisG/hog1Δ::hisG | |||

| CU2 (URA3/ura3) | Ura+ derivative of CAI4 | DH1209 | 40 |

| 1F54 (cat1/cat1) | ura3::λimm434/ura3::λimm434cat1Δ::hisG/cat1Δ::hisG-URA3 | DH1213 | 40 |

| CHK21 (chk1/chk1) | ura3::λimm434/ura3::λimm434chk1Δ::hisG-URA3-hisG/chk1Δ::hisG | DH177 | 6 |

| CAT1-GFP | CAI4 with plasmid pCAT1-GFP-URA3 integrated at the RPS1 locusa | DH939 | 13 |

Chemicals.

Acidified ethyl acetate (0.01% glacial acetic acid) was used to make 50 mM stock solutions of trans,trans-farnesol (Sigma-Aldrich). α-Tocopherol (α-TOH) (Sigma-Aldrich) and ascorbic acid (Sigma-Aldrich) were dissolved in ethanol and Milli-Q water to obtain stock solutions of 50 mM and 1 M, respectively. All the stock solutions were made fresh before each experiment and added to appropriate tubes at final concentrations of 50 and 100 μM (farnesol and α-tocopherol) or 50 mM (ascorbic acid).

Molecular biology procedures and plasmid constructions.

Standard molecular biology methods were used for genetic constructions. Strain CaAP16 was constructed by transforming strain DH482 (ras1::hisG/ras1::hisG [33]) by electroporation with the PacI-digested vector pAP16. To construct pAP16, a 1,000-base region upstream of the RAS1 open reading frame (ORF) was amplified from strain SC5314 genomic DNA with primers KpnIpRAS1 F (5′-AAGGAAGGTACCCGTAAAAGGTTTTTGTC-3′) and XhoIpRAS1R (5′-AGGAAGCTCGAGGGTATGTATATGTGTGG-3′) and ligated into KpnI/XhoI-digested pAU34 (62), resulting in pAP1. Next, an 800-base region downstream of the RAS1 stop codon was amplified from strain SC5314 genomic DNA with primers BamHItRAS1F (5′-CTCTCGGGATCCGCTAACTAAAAAGTTCTCG-3′) and XbaItRAS1R (5′-CCGGGCCGTCTAGACCACTTCTTCTTCCTCC-3′) and ligated into BamHI/XbaI-digested pAP1, resulting in plasmid pAP13. The RAS1 ORF was amplified from pYPB1-ADHpL-CaRAS1 (48) with primers XhoIFLRAS1F (5′-CTCGAGATGGATTATAAAGATGATGATGATAAAGCGGCGATGTTGAGAGAATAT-3′) and BamHIRAS1R (5′-CTCGGATCCTCAAACAATAACACAACATCCATT-3′), introducing a single FLAG sequence upstream of the RAS1 ORF. Following digestion with XhoI and BamHI, the FLAG-RAS1 fragment was ligated into similarly digested pAP13, resulting in plasmid pAP16.

Flow cytometry assays.

Washed cells from overnight cultures were resuspended in YPD at a density of 105 ml−1 and incubated at 30°C in a roller drum for 2 h. The cells were then treated with 50 μM farnesol or acidified ethyl acetate (negative control) and incubated at 30°C for another 2 h. The cells were spun down and resuspended in 250 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then kept on ice until they were sorted. Three populations of cells were sorted, depending on the intensity of the fluorescence of the cells, using a Becton Dickinson FACStar Plus high-speed sorting cytometer. Five thousand cells of each sorted population were resuspended in YPD containing 10 mM H2O2 and incubated for 90 min in a roller drum at 30°C. Following incubation, the cells were plated on YPD and incubated at 30°C for 24 to 36 h. The number of CFU per plate was then determined. Duplicate experiments were performed for each subpopulation, and the experiments were performed twice independently.

Effect of farnesol on survival after H2O2 treatments.

Washed cells from overnight cultures were resuspended in YPD at a density of 105 cells ml−1 and incubated at 30°C in a roller drum for 2 h. The cells were then treated with 50 μM farnesol and/or 50 μM α-tocopherol or acidified ethyl acetate (vehicle control) and incubated at 30°C for two more hours. The cells were then harvested by centrifugation to remove farnesol and resuspended in 5 ml of fresh YPD. H2O2 was added to a final concentration of 10 mM unless otherwise specified, and the cells were incubated at 30°C for 90 min. Following incubation with H2O2, the cells were plated on YPD, and the resultant colonies were counted after 24 to 36 h. Duplicates were included for each treatment, and the entire experiment was repeated independently at least three times.

ROS accumulation in C. albicans cells.

Intracellular ROS accumulation was examined using the fluorescent probe 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) (5 mM in dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]; Molecular Probes). Washed cells from overnight cultures were resuspended to a concentration of 106 cells ml−1 in 5 ml of YPD. The cells were grown at 30°C in a roller drum for 1 h and then treated with either 50 or 100 μM farnesol, 10 mM H2O2, 50 mM ascorbic acid, 50 μM α-tocopherol, or the appropriate vehicle control. The cells were incubated at 30°C in a roller drum for 30 min, and then a 1-ml aliquot was harvested, centrifuged, and washed once with YPD. The cells were resuspended in 500 μl of YPD, and 5 μl of DCFH-DA was added. The cells were incubated in the dark for 30 min under 180-rpm agitation. Then, the cells were collected by centrifugation, washed once with 1 ml PBS, and resuspended in 50 μl PBS. Fluorescence was examined by epifluorescence microscopy with a fixed exposure time, using a Zeiss Axiovert inverted microscope equipped with a 63× objective and Axiovision software. For each replicate and treatment, over 200 cells were examined in at least four different randomly chosen fields. The quantification of ROS was performed by scoring the number of green fluorescent cells (ROS) relative to all cells. Each experimental condition was tested in triplicate on different days.

Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR analysis of C. albicans transcripts.

Cells were grown as described for the H2O2 challenge experiments, except that the cells were then treated with 50 μM farnesol and/or 50 μM α-tocopherol or acidified ethyl acetate (vehicle control) prior to the second 2-h incubation or with 10 mM H2O2 followed by incubation at 30°C for 30 and 60 min. The cells were then harvested by centrifugation for 5 min at 5,000 rpm and immediately snap-frozen. The cells were lysed by mechanical disruption of the frozen pellet using 0.5-mm silica beads, and total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and DNase treated with DNA-free (Ambion). For each reaction, 400 ng of RNA was used in cDNA synthesis. cDNA synthesis and PCRs were performed as previously described (10). The complete experiments were repeated three times independently. Transcripts were quantified using ImageJ.

Hog1 phosphorylation assay.

Cells were resuspended in YPD at a density of 106 ml−1 and incubated at 30°C in a roller drum for 2 h. The cells were treated with 10 mM H2O2, 50 μM farnesol, or acidified ethyl acetate (vehicle control) and incubated at 30°C for 30 min. The cells were then harvested by centrifugation for 5 min at 5,000 rpm and immediately snap-frozen. Protein extraction was performed as previously described (59). To equalize the amounts of protein loaded, the proteins were quantified using the Bradford assay following the manufacturer's recommendations (Bio-Rad). Protein separation was performed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-10% PAGE). Then, the proteins were then transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. The phospho-p38 MAP kinase (Thr180/Tyr182) antibody (Cell Signaling technology) was used to determine the level of phosphorylation of Hog1 (61). The Hog1 protein level was determined by probing blots with the ScHog1 γ-215 polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) (4). Western blots were developed according to the manufacturer's conditions using the SuperSignal West Pico Goat IgG Detection kit (ThermoScientific). The Hog1 protein amount and Hog1 phosphorylation level were quantified using Vision work LS software (UVP, CA). For normalization, the intensities of three individualized protein bands from Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gels were measured. The average of the intensities of the three bands was then calculated and used for normalization of the amount of Hog1 protein and the level of phosphorylation of Hog1.

Statistical analyses.

One-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) and t tests were performed using Prism 5.0. (GraphPad Software).

RESULTS

CAT1 induction is essential for farnesol-mediated protection against H2O2 killing.

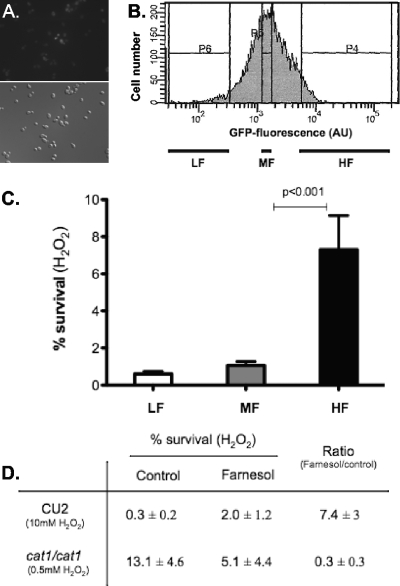

We and others have previously shown that farnesol leads to dose-dependent increases in levels of the CAT1 transcript, which encodes catalase (10, 16, 65). Because deletion of C. albicans CAT1 leads to increased sensitivity to OX stress (41, 67) and CAT1 transcription is activated in response to OX stress (13, 14), it is very likely that the enhancement of CAT1 transcription by farnesol is predictive of protection against H2O2. To assess whether the induction of CAT1 in the presence of farnesol is correlated with protection against H2O2 in yeast cells, we exploited the fact that the induction of CAT1 expression is heterogeneous within the population at moderate farnesol concentrations (10) (Fig. 1A). Using a C. albicans strain with two wild-type copies of CAT1 and a CAT1 promoter fusion to GFP at the RPS1 locus (13), we sorted yeast cells grown in the presence of farnesol into populations with low, intermediate, and high levels of green fluorescent protein (GFP) fluorescence and analyzed their susceptibility to H2O2 (Fig. 1B). The three subpopulations corresponded to the 5% of the whole population with the lowest fluorescence, 10% around the median, and the 5% with the highest fluorescence. A strong correlation between the level of expression of CAT1 and the resistance to H2O2 was observed (Fig. 1C), suggesting that the increase of resistance to OX stress in the presence of farnesol is correlated with an induction of catalase and that CAT1 transcript levels are a good marker of OX stress resistance. When control populations of CAT1-GFP cells grown without exogenous farnesol were analyzed, the proportion of cells producing high levels of CAT1 transcripts was lower than in farnesol-treated populations, but cells with higher levels of GFP still showed increased survival after H2O2 challenge in comparison to cells with intermediate or low levels of GFP (data not shown). As a control for potential effects of farnesol on GFP fluorescence or stability, a population of cells containing an ACT1 promoter fused to the GFP gene was also sorted, and the H2O2 susceptibilities of cells with low, intermediate, and high levels of fluorescence were analyzed (13). No correlation between fluorescence intensity and H2O2 resistance was observed with the strain bearing the ACT1-GFP fusion (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Role of CAT1 in farnesol-induced H2O2 survival. (A) Epifluorescence and differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopic views of CAT1-GFP cells in exponential phase treated with 50 μM farnesol for 2 h. (B) Histogram of fluorescence intensities of CAT1 in a farnesol-treated population of C. albicans cells with CAT1-GFP promoter fusion during early exponential-phase growth in liquid culture as revealed by laser scanning cytometry. Three subpopulations visualized on the histogram by the P4, P5, and P6 bars were sorted and challenged with 10 mM H2O2. LF, low fluorescence intensity (P6 subpopulation); MF, medium fluorescence (P5); HF, high fluorescence (P4). AU, arbitrary units. (C) Survival of the three subpopulations of cells shown in panel A under 10 mM H2O2 treatment. The data are expressed as the mean value (plus standard deviation [SD]) of duplicate samples. (D) Effect of pretreatment with 50 μM farnesol on the survival of cat1/cat1 and WT cells in H2O2. Following 2 h of incubation with 50 μM farnesol in YPD at 30°C, cells were harvested and challenged for 90 min with 0.5 mM (Δcat1/cat1) or 10 mM (WT) H2O2. Survival was assessed by dilution plating. The fold survival is expressed as the ratio between the survival of farnesol-treated cells and untreated cells. The data are expressed as the mean value (±SD) of three independent cultures. Survival after H2O2 exposure and pretreatment with farnesol was significantly higher in CU2 (WT), but not in the cat1/cat1 mutant (t test; P < 0.05).

As an alternative approach to determine if farnesol-mediated protection against OX stress is due to induction of CAT1 expression, we measured the survival of WT and cat1/cat1 cells after H2O2 exposure in cells pregrown with farnesol and in untreated cells. Consistent with data previously reported by Westwater et al. (65), WT cells pretreated with 50 μM farnesol had 6- to 8-fold-higher survival of harsh OX stress generated by H2O2 (10 mM) than control cultures (Fig. 1D). In contrast, farnesol did not protect cat1/cat1 cells against H2O2 stress, indicating that catalase is required for farnesol-mediated protection against H2O2. Farnesol pretreatment in fact decreased the subsequent survival of the cat1/cat1 mutant upon H2O2 exposure (5.1% survival) relative to control cultures (13% survival). As discussed in more detail below, farnesol can induce ROS accumulation (31, 57), and the inability of cat1/cat1 mutants to detoxify these ROS may have led to increased killing during the H2O2 challenge. Lower levels of H2O2 were used to assess changes in the sensitivity of the cat1/cat1 mutants upon farnesol exposure, as 10 mM H2O2 led to complete killing of the cat1/cat1 population.

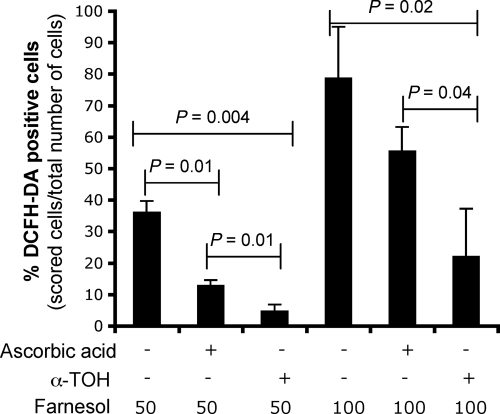

Farnesol-induced OX stress is not required for protection against subsequent OX stress.

Under some conditions, farnesol can be toxic (31, 63), and it has been shown to induce intracellular accumulation of ROS in C. albicans (57). To determine if farnesol induced ROS under our growth conditions, we treated cells with farnesol in the presence or absence of ROS scavengers. The accumulation of ROS was measured with the fluorescent dye DCFH-DA (57), and the results are shown here in the cat1/cat1 background to allow easier detection of the generation of lower levels of ROS. As a positive control, cells were challenged with H2O2, which led to 97.6% ± 1.0% of the cells being DCFH-DA positive. Consistent with the findings of Shirtliff et al. (57), farnesol induced the accumulation of ROS in a concentration-dependent manner, with 36% of cat1/cat1 cells in exponential growth containing detectable levels of ROS after a 30-min exposure to 50 μM farnesol (Fig. 2A). To determine if the ROS generated by farnesol could be scavenged by known antioxidants that localize either to the cytosol or to membranes, ROS accumulation was measured in farnesol-treated cultures amended with ascorbic acid or α-TOH. As predicted, ascorbic acid suppressed detectable intracellular ROS when added with H2O2 (1.3% ± 2.0% of cells were DCFH-DA positive), while the membrane-localized α-TOH was not protective against intracellular ROS generated by H2O2 (96.4% ± 2.0% of cells were DCFH-DA positive). α-TOH effectively reduced ROS generated by farnesol when supplied at a concentration of 50 μM (Fig. 2), and 100 μM α-TOH completely suppressed farnesol-induced ROS accumulation, as detected by DCFH-DA (data not shown). While ascorbic acid also reduced the accumulation of ROS upon farnesol exposure (Fig. 2), it never completely suppressed ROS, even at high concentrations (100 mM) (data not shown). Neither ascorbic acid nor α-TOH induced DCFH-DA in cells when added alone (data not shown). These findings suggest that farnesol-mediated induction of ROS may occur in or near plasma or intracellular membranes. When similar experiments were performed in C. albicans WT SC5314, ROS were detected in 5% of cells incubated with farnesol, but not in cells treated with 50 μM farnesol and α-TOH (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Effects of farnesol, ascorbic acid, and α-tocopherol on ROS accumulation in cat1/cat1 cells as revealed by DCFH-DA staining. The cells were incubated in YPD at 30°C for 30 min with either 50 or 100 μM farnesol, 50 mM ascorbic acid, 50 μM α-tocopherol, or the appropriate vehicle control. The cells were then harvested, washed, and incubated with DCFH-DA for 30 min. Fluorescence was examined by epifluorescence microscopy with a fixed exposure time, and the quantification of cells accumulating ROS was performed by scoring the number of green fluorescent cells relative to all cells. The data are expressed as the mean value (plus SD) of triplicate samples.

To determine if the suppression of ROS generated by farnesol would decrease the protective effect of farnesol against subsequent challenge with H2O2, WT cells were pretreated with α-TOH, farnesol, or both for 2 h, washed, and then exposed to H2O2. The numbers of CFU were determined in H2O2- and mock-treated cultures. Pretreatment with α-TOH alone did not alter OX stress resistance, and the combination of farnesol and α-TOH was as effective as farnesol alone in terms of inducing protection against H2O2 stress (Fig. 3A), suggesting that ROS generation is not the primary mechanism by which increased oxidative stress resistance occurs.

Fig. 3.

(A) Effect of α-tocopherol on farnesol protection against H2O2. α-Tocopherol, farnesol, or both (50 μM) were added simultaneously to exponential-phase C. albicans SC5314 cultures, followed by incubation for 2 h. The cells were then challenged or not with 10 mM H2O2 for 90 min, and survival was measured by counting CFU. The data are expressed as the mean value (plus SD) of three independent cultures. (B) Quantification of CAT1 transcripts in C. albicans SC5314 culture. α-Tocopherol, farnesol, or both (50 μM) were added simultaneously to exponential-phase C. albicans SC5314 cultures, followed by incubation for 2 h. The transcript levels were normalized to GPD1 control transcript. The data are expressed as the mean value (plus SD) of three independent cultures.

To confirm that CAT1 induction by farnesol still occurs in the presence of the antioxidant α-TOH, we followed the transcript levels of CAT1 in response to α-TOH, farnesol, or both. As expected, farnesol induced increased levels of CAT1 transcript, and this induction was not suppressed by cotreatment with α-TOH (Fig. 3B) (P ≤ 0.01; t test). This reinforces our hypothesis that ROS generation is not essential for farnesol-mediated induction of CAT1 expression and oxidative-stress resistance.

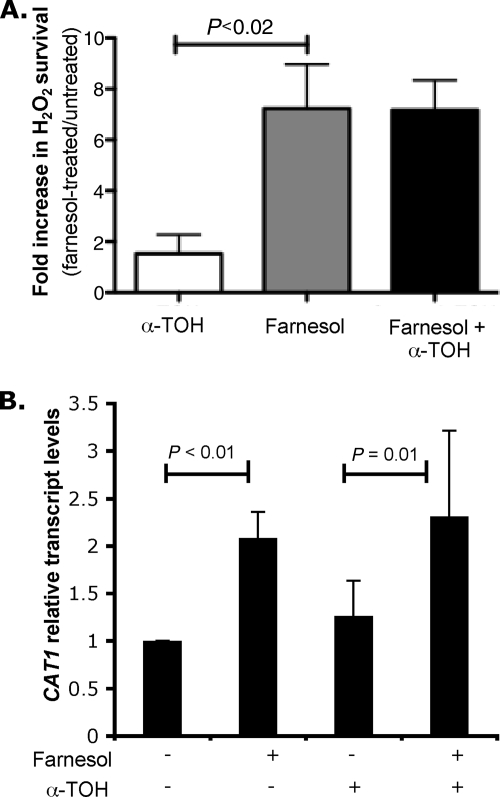

Hog1 MAP kinase and Chk1 histidine kinase are not necessary for farnesol protection against H2O2 killing.

Several signaling pathways have been described as regulating CAT1 expression. The Hog1 MAP kinase pathway plays an important role in the adaptive response to harsh OX stress in C. albicans (8, 39). OX stress is sensed by the membrane-associated protein Sln1, which activates a MAP kinase cascade leading to the phosphorylation of Hog1 (Hog1-P). Once phosphorylated, Hog1-P is translocated into the nucleus, where it activates OX stress response genes, including CAT1. Farnesol has been reported to induce the phosphorylation of Hog1, though the cause and the consequences of this increased phosphorylation have not been determined (61). We repeated this result (Fig. 4, inset), and farnesol effects on Hog1 phosphorylation are discussed further below. Since CAT1 expression is correlated with increased survival against H2O2 (Fig. 1B), we tested the hypothesis that Hog1 is necessary for farnesol-induced OX stress resistance by measuring the effects of farnesol pretreatment on survival after H2O2 exposure in hog1/hog1 and WT strains. Like the WT reference strain, the hog1/hog1 strain was more resistant to H2O2 after pretreatment with farnesol (Fig. 4). The level of protection in the hog1/hog1 mutant was slightly lower than in the WT, although the decrease was not statistically significant (t test; P > 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Hog1 and Chk1 are not required for farnesol-mediated protection against H2O2 stress. Following 2 h of incubation with 50 μM farnesol in YPD at 30°C, cells were harvested and challenged for 90 min with 10 mM H2O2. Survival was assessed by dilution plating. The fold survival is expressed as the ratio between the survival of farnesol-treated cells and untreated cells. The parental hog1/hog1 and chk1/chk1 strains RM100 and CAF2 were used as WT controls. The data are expressed as the mean value (plus SD) of three independent cultures. (Inset) The phosphorylation of Hog1 in SC5314 cells was assessed by Western blotting after 30 min of incubation without any treatment (lane 1), with 10 mM H2O2 (lane 2), or with 50 μM farnesol (lane 3). The hog1/hog1 strain is shown as a control (lane 4).

Because deletion of the two-component histidine kinase Chk1 leads to sensitivity to OX stress and filamentation is no longer inhibited by farnesol in the chk1/chk1 mutant (30, 34), we also tested the involvement of Chk1 in farnesol-mediated resistance to H2O2. Like the hog1/hog1 mutant, the chk1/chk1 mutant was still protected from H2O2-mediated killing by farnesol. Only a small, nonsignificant decrease in farnesol-induced protection against OX stress was observed (t test; P > 0.05) (Fig. 4). Thus, neither the Hog1 MAP kinase nor the Chk1 histidine kinase signaling pathway is required for farnesol-mediated protection against OX stress.

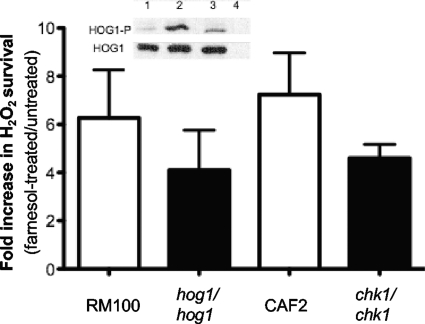

The Ras-cAMP pathway is necessary for farnesol-mediated protection against H2O2.

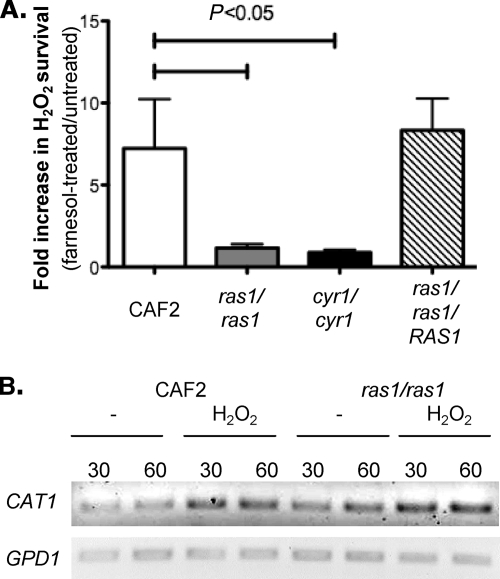

We have previously reported that farnesol inhibits Ras1-adenylate cyclase signaling, leading to the inhibition of hyphal growth (10). As the Ras-cAMP cascade represses the expression of OX stress response genes (1, 24, 66), we sought to test the hypothesis that farnesol-mediated inhibition of this pathway leads to the increased transcription of CAT1 and protection against ROS in yeast. To do this, we measured the effects of farnesol on ras1/ras1 and cyr1/cyr1 mutant survival after treatment with H2O2. Consistent with data reported by Bahn et al. (1), both ras1/ras1 and cyr1/cyr1 were 10 times less sensitive to H2O2 than the WT (data not shown). Contrary to what is observed with the wild type, ras1/ras1 and cyr1/cyr1 mutants did not gain increased ROS protection upon incubation with farnesol (Fig. 5A) (P < 0.05; t test). The ras1/ras1 strain complemented with one copy of the RAS1 gene was protected by farnesol as well as the wild type (Fig. 5A). Ras-cAMP mutants are thought to be more resistant to OX stress because of increased expression of OX stress response genes (1, 24). Therefore, ras1/ras1 and cyr1/cyr1 cells may not respond to farnesol because CAT1 is maximally derepressed. To test this hypothesis, we measured the level of expression of CAT1 in response to 10 mM H2O2 in WT and ras1/ras1 cells. Consistent with previous data (1, 24), the level of CAT1 transcripts was higher in the ras1/ras1 than in the WT cells (Fig. 5B). However, treatment with H2O2 induced CAT1 transcript levels in both backgrounds, indicating that ras1/ras1 cells are still able to respond to OX stress transcriptionally. We previously reported quantitative RT-PCR data that showed that farnesol leads to large induction in CAT1 transcript levels in WT cells, but not in ras1/ras1 or cyr1/cyr1 mutants (10). Altogether, these data are consistent with the inhibition of Ras-cAMP signaling as an important mechanism for farnesol protection against OX stress.

Fig. 5.

(A) ras1/ras1 and cyr1/cyr1 mutants lack farnesol-mediated protection against H2O2 stress. Survival was assessed as described in the legend to Fig. 4. The fold survival is expressed as the ratio between the survival of farnesol-treated cells and untreated cells. The data are expressed as the mean value (plus SD) of three independent cultures. (B) Expression of CAT1 and GPD1 in C. albicans CAF2 and ras1/ras1 cultures in response to H2O2. Cells were challenged with 10 mM H2O2 for 30 or 60 min. The experiments were performed independently three times, and the RT-PCR is representative of the results obtained each time.

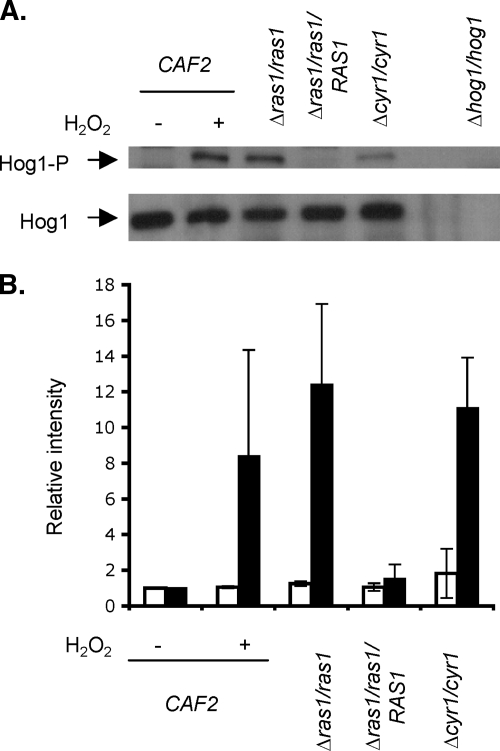

The existence of cross talk between the Ras-cAMP pathway and the Hog1 MAP kinase cascade has been suggested in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (3, 55, 64). In light of our data showing that farnesol acts via the Ras-cAMP pathway to enhance OX stress resistance and that Hog1 phosphorylation is increased in the presence of exogenous farnesol, we determined if there was also a potential connection between these two pathways in C. albicans. We studied the amounts of Hog1 and the level of Hog1 phosphorylation in the ras1/ras1 and cyr1/cyr1 backgrounds. We did not observe any difference in the concentrations of Hog1 protein in the different backgrounds (Fig. 6). In contrast, Hog1 phosphorylation was significantly increased in ras1/ras1 and cyr1/cyr1 strains (Fig. 6). The complementation of ras1/ras1 with one allele of RAS1 partially complemented the increased phosphorylation of Hog1 in the ras1/ras1 background. This suggests that the Ras1-cAMP cascade inhibits the phosphorylation of Hog1. Therefore, the phosphorylation of Hog1 in response to farnesol is likely to be at least partially a consequence of the inhibition of the Ras1-cAMP pathway by farnesol.

Fig. 6.

The Ras-cAMP cascade inhibits Hog1 phosphorylation. (A) Western blot of Hog1 and Hog1-P. Washed cells from overnight cultures of the wild-type CAF2, Δras1/ras1, Δcyr1/cyr1 Δras1/ras1/RAS1, and Δhog1/hog1 strains were resuspended in YPD and incubated for 2 h at 30°C. The CAF2 cells were then treated with 10 mM H2O2 (+) or water (−), and all strains were incubated for another 30 min. Cells were collected and processed for Western blot analyses of Hog1 and Hog1-P levels. Coomassie staining was used to visualize and normalize the total amounts of proteins. The experiments were performed independently at least three times, and the Western blot is representative of the results obtained each time. (B) Quantification of Hog1 protein (white bars) and Hog1 phosphorylation (black bars) levels in the different genetic backgrounds. The levels are expressed relative to the intensity measured in the control treatment. All data were normalized to Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE protein levels. The data are expressed as the mean value (plus SD) of two independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

Farnesol induces increased resistance to oxidative stress (Fig. 1) (65). We have shown that the accumulation of ROS in the presence of farnesol was not necessary for subsequent protection against OX stress (Fig. 3A). Instead, our data suggest that farnesol-mediated induction of catalase expression and ROS resistance in yeast occurred mainly by inhibition of the Ras1-cAMP pathway (Fig. 5A), though Hog1 or Chk1 regulators may also participate in the response. While Hog1 was not necessary for farnesol-mediated protection against H2O2, Hog1 phosphorylation increased in the presence of farnesol, as has been shown previously (61). We demonstrated that the disruption of the Ras1-cAMP cascade led to a marked increase in Hog1 phosphorylation even in the absence of farnesol or other sources of oxidative stress, indicating the presence of undescribed links between the Ras1-cAMP and Hog1 MAP kinase pathways.

It is interesting that C. albicans employs a molecule that can generate ROS for the purpose of cell-cell signaling. Farnesol has been previously shown to be poisonous to bacteria, fungi, and mammalian cells (4, 27, 37, 47, 54, 56). In contrast, farnesol toxicity for C. albicans is conditional (31), and several studies report a complete absence of lethality (10, 26, 45). Work by Machida et al. (37) suggests that ROS accumulation in the presence of farnesol occurs by perturbation of the mitochondrial electron transport chain in S. cerevisiae. Consistent with farnesol acting in a membrane environment, farnesol-induced ROS were only partially suppressed by ascorbic acid, a hydrophilic antioxidant that acts in the cytosol and at the membrane interface (38), and were more fully suppressed by α-TOH, which inserts within membranes (23). The isoprenoid structure of farnesol suggests that it does not directly generate ROS. C. albicans seems to be protected against the ROS generated by endogenous farnesol under normal culture conditions (10, 26, 45). This may be due to the signaling roles of farnesol that induce OX stress response genes, the fact that farnesol is at high concentrations when C. albicans cultures are in stationary phase, or the presence of other regulated resistance mechanisms, such as efflux pumps. Understanding how C. albicans can resist the potential toxicity of farnesol may provide interesting and important insights into C. albicans physiology.

The finding that farnesol protects against H2O2 killing via inhibition of the Ras1-Cyr1-PKA signaling pathway indicates that farnesol acts in the same way under hypha-inducing (10) and noninducing conditions but leads to different phenotypes. The increase of cellular levels of cAMP activates the Tpk2 subunit of protein kinase A which, mediates the inhibition of the transcription of OX stress-related genes, such as catalase and superoxide dismutase genes (Fig. 7A) (10, 21). The repression of the Ras1 cascade by farnesol would thus relieve the inhibition maintained on catalase transcription by Tpk2. Our data indicate that Hog1 phosphorylation is negatively regulated by the Ras1-cAMP cascade via an unknown intermediate (Fig. 6) but that the contribution of Hog1 to the farnesol-mediated protection against OX stress was minor (Fig. 4). It is possible that the contribution of Hog1 has been partially masked by the strong repression of CAT1 by PKA. It remains to be determined how much ROS production and Ras1 inhibition contributed to Hog1 phosphorylation in the presence of farnesol. Treatment of cells with farnesol and α-TOH did not provide answers, because α-TOH induced Hog1 phosphorylation (data not shown). Moreover, the role of Hog1 may have been hidden by the activity of the transcription factor Cap1, which controls oxidative-stress resistance gene expression (15) in direct response to intracellular ROS. Oxidant conditions within cells inhibit the export of Cap1 from the nucleus and allow Cap1 to activate the transcription of OX stress-related genes (25). Farnesol-mediated ROS production likely activates Cap1, but since suppression of farnesol-induced ROS by antioxidants did not suppress farnesol protection against OX stress (Fig. 3A), Cap1 is not likely a major player in farnesol-induced ROS resistance.

Fig. 7.

(A) Proposed model for the mechanism of farnesol protection against OX stress. (B) Interaction between farnesol-associated signaling pathways (2, 12, 33–35, 49, 50).

While it has been well established that downregulation of the cAMP signaling pathway increases resistance to stresses (1, 24, 66), perhaps aiding in C. albicans survival of host defenses, it is not known how Ras1-cAMP inhibits the expression of stress response genes. Our finding that the Ras1-cAMP cascade negatively regulates Hog1 phosphorylation (Fig. 6), through a mechanism yet to be described, could partially explain this increased resistance. Partial epistasis between Hog1 and Ras-PKA signaling has been also established in S. cerevisiae, although its mechanism is unknown, as well (3, 55, 64). PKA could maintain the phosphorylation of Slnp1 or Ssk1 upstream of Hog1 (8), but an intermediate kinase would be necessary, as PKA specifically phosphorylates serine and threonine residues while regulation of the activities of members of the Hog1 MAP kinase pathway involves histidine or aspartic acid phosphorylation. In mammalian cells, cAMP inhibits the phosphorylation of p38, the homolog of Hog1, via the CREB pathway (17, 68). Evidence for the existence of a functional CREB-like protein in C. albicans (cAMP response element binding protein) has recently been reported, and such a regulator may mediate Ras1 control of CAT1 and other stress response genes (58).

The finding of cross talk between the Ras1-cAMP cascade and the Hog1 MAP kinase pathway provides new insight into the understanding of the mechanism of action of farnesol. So far, farnesol has been shown to affect three different signaling pathways activated by multiple environmental cues—the Ras-cAMP pathway (10), the Hog1 MAP kinase pathway (61), and the Cek1 MAP kinase pathway (49)—and two other regulators, Chk1 (30) and the transcription factor Tup1 (29), are resistant to the effects of farnesol. The mechanism by which farnesol modulates the activities of these pathways is still unknown, as no receptor or target has been reported. Farnesol could act independently on each pathway or have a unique target that connects all of the pathways. Cross-regulation between all of these pathways via Ras1 and Hog1 has been established (Fig. 7B), except for Tup1. Because Ras1 associates with membranes and because the lipophilic nature of farnesol strongly predicts its association with membranes, Ras1 appears to be a good candidate for the master receptor of farnesol effect. The environmental conditions also influence which of these pathways are active or dominant, as they are not all necessarily active at the same time. An alternative hypothesis could be that farnesol may disturb, by altering membrane structure, the sensors Sho1, Chk1, and Ras1, which are associated with the membranes and sit on top of each pathway.

The data we have presented in this study were obtained by the addition of exogenous farnesol. Evidence indicates that endogenously produced farnesol also protects against killing by H2O2 (65). Farnesol is constantly produced by C. albicans cells and reaches its maximal concentration at the entrance to stationary phase, according to Hornby et al. (26). Interestingly, the expression of CAT1 and the resistance to OX stress are much higher in stationary-phase cells than in exponential-phase cells (65). Farnesol is also thought to accumulate within biofilms and to be responsible for the dispersal of biofilms (44, 45). From our results and those of Westwater et al. (65) linking farnesol and OX stress resistance, we expect that cells released from biofilm in response to farnesol would be highly resistant to OX stress. Cells liberated from Candida biofilms grown on implanted biomaterials, such as catheters or heart valves, directly reach the bloodstream, where they encounter macrophages and cells from the innate immune system, which uses OX stress to kill pathogens. Following this model, cells released from biofilms in response to farnesol would be strongly resistant to killing by the primary immune system. Thus, the role of farnesol in C. albicans pathogenicity may not be limited to the regulation of morphogenesis but may also include resistance to the host immune response. Further analyses of the links between biofilm dispersal, farnesol production, and resistance to OX stress should provide new and valuable insights into Candida pathogenesis that may lead to new strategies for the development of antifungal drugs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank G. Ward and A. Givan from the Herbert C. Englert cell analysis laboratory for their help and assistance in flow cytometry analyses (Norris Cotton Cancer Center/Dartmouth Medical School, Hanover, NH). We thank P. Sundstrom (Dartmouth Medical School) for her critical reading of the manuscript and for helpful comments.

This work was supported by the NIH (K22 DE016542 [D.A.H.]).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 29 January 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bahn Y. S., Molenda M., Staab J. F., Lyman C. A., Gordon L. J., Sundstrom P. 2007. Genome-wide transcriptional profiling of the cyclic AMP-dependent signaling pathway during morphogenic transitions of Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 6:2376–2390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biswas S., Van Dijck P., Datta A. 2007. Environmental sensing and signal transduction pathways regulating morphopathogenic determinants of Candida albicans. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 71:348–376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boguslawski G. 1992. PBS2, a yeast gene encoding a putative protein kinase, interacts with the RAS2 pathway and affects osmotic sensitivity of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Gen. Microbiol. 138:2425–2432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burke Y. D., Ayoubi A. S., Werner S. R., McFarland B. C., Heilman D. K., Ruggeri B. A., Crowell P. L. 2002. Effects of the isoprenoids perillyl alcohol and farnesol on apoptosis biomarkers in pancreatic cancer chemoprevention. Anticancer Res. 22:3127–3134 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bustamante C. I. 2005. Treatment of Candida infection: a view from the trenches! Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 18:490–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calera J. A., Calderone R. 1999. Flocculation of hyphae is associated with a deletion in the putative CaHK1 two-component histidine kinase gene from Candida albicans. Microbiology 145:1431–1442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calera J. A., Calderone R. 1999. Histidine kinase, two-component signal transduction proteins of Candida albicans and the pathogenesis of candidosis. Mycoses 42Suppl. 2:49–53 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chauhan N., Latge J. P., Calderone R. 2006. Signalling and oxidant adaptation in Candida albicans and Aspergillus fumigatus. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4:435–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D'Autreaux B., Toledano M. B. 2007. ROS as signalling molecules: mechanisms that generate specificity in ROS homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8:813–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis-Hanna A., Piispanen A. E., Stateva L. I., Hogan D. A. 2008. Farnesol and dodecanol effects on the Candida albicans Ras1-cAMP signalling pathway and the regulation of morphogenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 67:47–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dumitru R., Navarathna D. H., Semighini C. P., Elowsky C. G., Dumitru R. V., Dignard D., Whiteway M., Atkin A. L., Nickerson K. W. 2007. In vivo and in vitro anaerobic mating in Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 6:465–472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eisman B., Alonso-Monge R., Roman E., Arana D., Nombela C., Pla J. 2006. The Cek1 and Hog1 mitogen-activated protein kinases play complementary roles in cell wall biogenesis and chlamydospore formation in the fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 5:347–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Enjalbert B., MacCallum D. M., Odds F. C., Brown A. J. 2007. Niche-specific activation of the oxidative stress response by the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans. Infect. Immun. 75:2143–2151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Enjalbert B., Nantel A., Whiteway M. 2003. Stress-induced gene expression in Candida albicans: absence of a general stress response. Mol. Biol. Cell 14:1460–1467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Enjalbert B., Smith D. A., Cornell M. J., Alam I., Nicholls S., Brown A. J., Quinn J. 2006. Role of the Hog1 stress-activated protein kinase in the global transcriptional response to stress in the fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Mol. Biol. Cell 17:1018–1032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Enjalbert B., Whiteway M. 2005. Release from quorum-sensing molecules triggers hyphal formation during Candida albicans resumption of growth. Eukaryot. Cell 4:1203–1210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng W. G., Wang Y. B., Zhang J. S., Wang X. Y., Li C. L., Chang Z. L. 2002. cAMP elevators inhibit LPS-induced IL-12 p40 expression by interfering with phosphorylation of p38 MAPK in murine peritoneal macrophages. Cell Res. 12:331–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fitzsimmons N., Berry D. R. 1994. Inhibition of Candida albicans by Lactobacillus acidophilus: evidence for the involvement of a peroxidase system. Microbios 80:125–133 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frohner I. E., Bourgeois C., Yatsyk K., Majer O., Kuchler K. 2009. Candida albicans cell surface superoxide dismutases degrade host-derived reactive oxygen species to escape innate immune surveillance. Mol. Microbiol. 71:240–252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garcia-Mendoza A., Liebana J., Castillo A. M., De la Higuera A., Piedrola G. 1993. Evaluation of the capacity of oral Streptococci to produce hydrogen peroxide. J. Med. Microbiol. 39:434–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giacometti R., Kronberg F., Biondi R. M., Passeron S. 2009. Catalytic isoforms Tpk1 and Tpk2 of Candida albicans PKA have non-redundant roles in stress response and glycogen storage. Yeast 26:273–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gillum A. M., Tsay E. Y., Kirsch D. R. 1984. Isolation of the Candida albicans gene for orotidine-5′-phosphate decarboxylase by complementation of S. cerevisiae ura3 and E. coli pyrF mutations. Mol. Gen. Genet. 198:179–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gomez-Fernandez J. C., Villalain J., Aranda F. J., Ortiz A., Micol V., Coutinho A., Berberan-Santos M. N., Prieto M. J. 1989. Localization of alpha-tocopherol in membranes. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 570:109–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harcus D., Nantel A., Marcil A., Rigby T., Whiteway M. 2004. Transcription profiling of cyclic AMP signaling in Candida albicans. Mol. Biol. Cell 15:4490–4499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herrero E., Ros J., Belli G., Cabiscol E. 2008. Redox control and oxidative stress in yeast cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1780:1217–1235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hornby J. M., Jensen E. C., Lisec A. D., Tasto J. J., Jahnke B., Shoemaker R., Dussault P., Nickerson K. W. 2001. Quorum sensing in the dimorphic fungus Candida albicans is mediated by farnesol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:2982–2992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inoue Y., Shiraishi A., Hada T., Hirose K., Hamashima H., Shimada J. 2004. The antibacterial effects of terpene alcohols on Staphylococcus aureus and their mode of action. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 237:325–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jamieson D. J., Stephen D. W., Terriere E. C. 1996. Analysis of the adaptive oxidative stress response of Candida albicans. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 138:83–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kebaara B. W., Langford M. L., Navarathna D. H., Dumitru R., Nickerson K. W., Atkin A. L. 2008. Candida albicans Tup1 is involved in farnesol-mediated inhibition of filamentous-growth induction. Eukaryot. Cell 7:980–987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kruppa M., Krom B. P., Chauhan N., Bambach A. V., Cihlar R. L., Calderone R. A. 2004. The two-component signal transduction protein Chk1p regulates quorum sensing in Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 3:1062–1065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Langford M. L., Hasim S., Nickerson K. W., Atkin A. L. 2010. Activity and toxicity of farnesol towards Candida albicans is dependent on growth conditions. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:940–942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lass-Florl C. 2009. The changing face of epidemiology of invasive fungal disease in Europe. Mycoses 52:197–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leberer E., Harcus D., Dignard D., Johnson L., Ushinsky S., Thomas D. Y., Schroppel K. 2001. Ras links cellular morphogenesis to virulence by regulation of the MAP kinase and cAMP signalling pathways in the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans. Mol. Microbiol. 42:673–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li D., Gurkovska V., Sheridan M., Calderone R., Chauhan N. 2004. Studies on the regulation of the two-component histidine kinase gene CHK1 in Candida albicans using the heterologous lacZ reporter gene. Microbiology 150:3305–3313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li D., Williams D., Lowman D., Monteiro M. A., Tan X., Kruppa M., Fonzi W., Roman E., Pla J., Calderone R. 2009. The Candida albicans histidine kinase Chk1p: signaling and cell wall mannan. Fungal Genet Biol. 46:731–741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lorenz M. C., Bender J. A., Fink G. R. 2004. Transcriptional response of Candida albicans upon internalization by macrophages. Eukaryot. Cell 3:1076–1087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Machida K., Tanaka T., Fujita K., Taniguchi M. 1998. Farnesol-induced generation of reactive oxygen species via indirect inhibition of the mitochondrial electron transport chain in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Bacteriol. 180:4460–4465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.May J. M. 1999. Is ascorbic acid an antioxidant for the plasma membrane? FASEB J. 13:995–1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Monge R. A., Roman E., Nombela C., Pla J. 2006. The MAP kinase signal transduction network in Candida albicans. Microbiology 152:905–912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nakagawa Y. 2008. Catalase gene disruptant of the human pathogenic yeast Candida albicans is defective in hyphal growth, and a catalase-specific inhibitor can suppress hyphal growth of wild-type cells. Microbiol. Immunol. 52:16–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakagawa Y., Kanbe T., Mizuguchi I. 2003. Disruption of the human pathogenic yeast Candida albicans catalase gene decreases survival in mouse-model infection and elevates susceptibility to higher temperature and to detergents. Microbiol. Immunol. 47:395–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nasution O., Srinivasa K., Kim M., Kim Y. J., Kim W., Jeong W., Choi W. 2008. Hydrogen peroxide induces hyphal differentiation in Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 7:2008–2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Negredo A., Monteoliva L., Gil C., Pla J., Nombela C. 1997. Cloning, analysis and one-step disruption of the ARG5,6 gene of Candida albicans. Microbiology 143:297–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nickerson K. W., Atkin A. L., Hornby J. M. 2006. Quorum sensing in dimorphic fungi: farnesol and beyond. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:3805–3813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ramage G., Saville S. P., Wickes B. L., Lopez-Ribot J. L. 2002. Inhibition of Candida albicans biofilm formation by farnesol, a quorum-sensing molecule. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:5459–5463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reeves E. P., Lu H., Jacobs H. L., Messina C. G., Bolsover S., Gabella G., Potma E. O., Warley A., Roes J., Segal A. W. 2002. Killing activity of neutrophils is mediated through activation of proteases by K+ flux. Nature 416:291–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rennemeier C., Frambach T., Hennicke F., Dietl J., Staib P. 2009. Microbial quorum sensing molecules induce acrosome loss and cell death in human spermatozoa. Infect. Immun. 77:4990–4997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rocha C. R., Schroppel K., Harcus D., Marcil A., Dignard D., Taylor B. N., Thomas D. Y., Whiteway M., Leberer E. 2001. Signaling through adenylyl cyclase is essential for hyphal growth and virulence in the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans. Mol. Biol. Cell 12:3631–3643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roman E., Alonso-Monge R., Gong Q., Li D., Calderone R., Pla J. 2009. The Cek1 MAPK is a short-lived protein regulated by quorum sensing in the fungal pathogen Candida albicans. FEMS Yeast Res. 9:942–955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roman E., Nombela C., Pla J. 2005. The Sho1 adaptor protein links oxidative stress to morphogenesis and cell wall biosynthesis in the fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:10611–10627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Romani L. 2002. Immunology of invasive candidiasis. ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ryan C. S., Kleinberg I. 1995. Bacteria in human mouths involved in the production and utilization of hydrogen peroxide. Arch. Oral Biol. 40:753–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.San Jose C., Monge R. A., Perez-Diaz R., Pla J., Nombela C. 1996. The mitogen-activated protein kinase homolog HOG1 gene controls glycerol accumulation in the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans. J. Bacteriol. 178:5850–5852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scheper M. A., Shirtliff M. E., Meiller T. F., Peters B. M., Jabra-Rizk M. A. 2008. Farnesol, a fungal quorum-sensing molecule triggers apoptosis in human oral squamous carcinoma cells. Neoplasia 10:954–963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schuller C., Brewster J. L., Alexander M. R., Gustin M. C., Ruis H. 1994. The HOG pathway controls osmotic regulation of transcription via the stress response element (STRE) of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae CTT1 gene. EMBO J. 13:4382–4389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Semighini C., Hornby J., Dumitru R., Nickerson K., Harris S. 2006. Farnesol-induced apoptosis in Aspergillus nidulans reveals a possible mechanism for antagonistic interactions between fungi. Mol. Microbiol. 56:753–765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shirtliff M. E., Krom B. P., Meijering R. A., Peters B. M., Zhu J., Scheper M. A., Harris M. L., Jabra-Rizk M. A. 2009. Farnesol-induced apoptosis in Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:2392–2401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Singh A., Dhillon N. K., Sharma S., Khuller G. K. 2008. Identification and purification of CREB like protein in Candida albicans. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 308:237–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sithanandam G., Ramakrishna G., Diwan B. A., Anderson L. M. 1998. Selective mutation of K-ras by N-ethylnitrosourea shifts from codon 12 to codon 61 during fetal mouse lung maturation. Oncogene 17:493–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Slover C. M., Danziger L. 2008. Lactobacillus: a review. Clin. Microbiol. Newsl. 30:23–27 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Smith D. A., Nicholls S., Morgan B. A., Brown A. J., Quinn J. 2004. A conserved stress-activated protein kinase regulates a core stress response in the human pathogen Candida albicans. Mol. Biol. Cell 15:4179–4190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Uhl M. A., Johnson A. D. 2001. Development of Streptococcus thermophilus lacZ as a reporter gene for Candida albicans. Microbiology 147:1189–1195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Uppuluri P., Mekala S., Chaffin W. L. 2007. Farnesol-mediated inhibition of Candida albicans yeast growth and rescue by a diacylglycerol analogue. Yeast 24:681–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Varela J. C., Praekelt U. M., Meacock P. A., Planta R. J., Mager W. H. 1995. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae HSP12 gene is activated by the high-osmolarity glycerol pathway and negatively regulated by protein kinase A. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:6232–6245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Westwater C., Balish E., Schofield D. A. 2005. Candida albicans-conditioned medium protects yeast cells from oxidative stress: a possible link between quorum sensing and oxidative stress resistance. Eukaryot. Cell 4:1654–1661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wilson D., Tutulan-Cunita A., Jung W., Hauser N. C., Hernandez R., Williamson T., Piekarska K., Rupp S., Young T., Stateva L. 2007. Deletion of the high-affinity cAMP phosphodiesterase encoded by PDE2 affects stress responses and virulence in Candida albicans. Mol. Microbiol. 65:841–856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wysong D. R., Christin L., Sugar A. M., Robbins P. W., Diamond R. D. 1998. Cloning and sequencing of a Candida albicans catalase gene and effects of disruption of this gene. Infect. Immun. 66:1953–1961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang J., Bui T. N., Xiang J., Lin A. 2006. Cyclic AMP inhibits p38 activation via CREB-induced dynein light chain. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26:1223–1234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]