Abstract

ColV plasmids of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli (ExPEC) encode a variety of fitness and virulence factors and have long been associated with septicemia and avian colibacillosis. These plasmids are found significantly more often in ExPEC, including ExPEC associated with human neonatal meningitis and avian colibacillosis, than in commensal E. coli. Here we describe pAPEC-O103-ColBM, a hybrid RepFIIA/FIB plasmid harboring components of the ColV pathogenicity island and a multidrug resistance (MDR)-encoding island. This plasmid is mobilizable and confers the ability to cause septicemia in chickens, the ability to cause bacteremia resulting in meningitis in the rat model of human disease, and the ability to resist the killing effects of multiple antimicrobial agents and human serum. The results of a sequence analysis of this and other ColV plasmids supported previous findings which indicated that these plasmid types arose from a RepFIIA/FIB plasmid backbone on multiple occasions. Comparisons of pAPEC-O103-ColBM with other sequenced ColV and ColBM plasmids indicated that there is a core repertoire of virulence genes that might contribute to the ability of some ExPEC strains to cause high-level bacteremia and meningitis in a rat model. Examination of a neonatal meningitis E. coli (NMEC) population revealed that approximately 58% of the isolates examined harbored ColV-type plasmids and that 26% of these plasmids had genetic contents similar to that of pAPEC-O103-ColBM. The linkage of the ability to confer MDR and the ability contribute to multiple forms of human and animal disease on a single plasmid presents further challenges for preventing and treating ExPEC infections.

ColV plasmids have a long history in scientific literature describing their association with the virulence of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli (ExPEC) (58). The first completed ColV plasmid sequence (24) localized the genes encoding the virulence traits to a 94-kb pathogenicity-associated island (PAI). Gene prevalence studies involving the genes in this PAI confirmed the hypothesis of Waters and Crosa that there are “constant” and “variable” portions of the ColV PAI and that the constant region contains the RepFIB and aerobactin operons (58). Since those studies, several more of these plasmids have been sequenced, including a plasmid variant known as ColBM, which is closely related to ColV plasmids, containing remnants of the ColV operon and the ColV PAI in a very similar arrangement (23). ColV and ColBM plasmids have been found to occur significantly more often in ExPEC than in commensal E. coli. Furthermore, recent work suggests that some ExPEC subpathotypes, including avian pathogenic E. coli (APEC) and human neonatal meningitis E. coli (NMEC), harbor these plasmids more often than other subpathotypes (10, 24, 26, 35, 42). Interestingly, although these plasmids are very prevalent in NMEC populations, the most-studied NMEC isolates appear to lack these plasmids (31, 61). Thus, far, it has been shown that ColV and ColBM plasmids contribute to E. coli's growth in human urine, its ability to cause a murine urinary tract infection (UTI), and its ability to contribute to septicemia and avian colibacillosis (1, 2, 49, 50, 60). Certain genes in the ColV plasmid PAI are upregulated greatly during avian infection and during growth in human urine (49), and certain genetic regions of the ColV plasmids have been associated with avian disease (57), further suggesting that the ColV and ColBM plasmids have a role in the pathogenesis of avian colibacillosis and UTI. However, despite the large number of phenotypic properties attributed to these plasmids, the underlying molecular mechanisms of these traits and the overall molecular biology of the ColV plasmid are not completely understood.

There is great concern about the possible emergence of multidrug-resistant bacteria. This is particularly true of the bacteria inhabiting production animals, in which antibiotics are routinely used as growth-promoting and therapeutic agents (47). Of particular interest are transmissible plasmids that, in a singe transfer event, are able to cause a major shift in the bacterial population dynamics by conferring resistance to multiple antimicrobial agents. Other types of virulence plasmids have been shown to encode multidrug resistance (MDR), but this has not been observed for ColV and ColBM plasmids previously. The initial aims of this study were to determine if naturally occurring plasmids containing the ColV PAI and an MDR-encoding island could be identified. Once a representative plasmid was identified, we sequenced and analyzed this plasmid to determine its roles in virulence and drug resistance and to determine if such plasmids present a risk to human and animal health. Here we describe this plasmid and the traits that it confers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

All strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Plasmid pAPEC-O103-ColBM was originally derived from ExPEC strain 408, which was isolated from a commercial laying hen with peritonitis. This strain was identified because it harbored a single large plasmid and contained both ColV plasmid virulence-associated genes and class 1 integron-associated genes. ExPEC 408 is a member of the O103 serogroup and B1 phylogenetic group (42). This strain was cured of pAPEC-O103-ColBM by repeated passage in overnight cultures grown in LB broth with shaking at 37°C. After overnight passage, replica plating was used to select for loss of plasmid-mediated resistance to streptomycin at a concentration of 50 μg/ml. pAPEC-O103-ColBM was reintroduced into the plasmid-cured derivative using electroporation (46). For ColV and ColBM gene prevalence studies, a total of 283 isolates were used, including 96 isolates from cases of human UTI, 96 E. coli isolates implicated in avian colisepticemia, and 91 isolates from cases of human neonatal meningitis. APEC isolates were obtained from lesion sites in chickens and turkeys raised for meat consumption and laying hens from commercial farms throughout the United States (42, 43). Seventy of the NMEC strains were obtained from the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of newborns in the Netherlands and were isolated from 1989 through 1997 (21, 26). The remaining NMEC isolates were isolated in a similar way in a similar time period from patients in the United States. The uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) isolates were obtained from MeritCare Medical Center in Fargo, ND (43). These isolates were obtained from urine of patients who were different ages and sexes and had uncomplicated UTI.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| E. coli strain or plasmid | Description |

|---|---|

| Strains | |

| 408 | Wild-type ExPEC containing pAPEC-O103-ColBM |

| 408.1 | Plasmid-cured derivative of ExPEC 408 |

| 408.2 | Plasmid-complemented derivative of ExPEC 408.1 |

| 408.3 | DH5α containing pAPEC-O103-ColBM |

| DH5α | Avirulent recipient strain |

| NMEC RS218 | Wild-type NMEC positive control |

| APEC O1 | Wild-type APEC positive control |

| Plasmids | |

| pAPEC-O103-ColBM | ColBM virulence plasmid |

| pRK2013 | Mobilization helper plasmid |

Plasmid isolation.

ExPEC strain 408's plasmid DNA was isolated using a Qiagen midi plasmid kit and a modified procedure optimized for bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) isolation (Qiagen). A single colony was inoculated into 100 ml of LB broth and grown overnight at 37°C with shaking. After purification, plasmid DNA was precipitated twice with 3 volumes of 100% ethanol, washed twice with 70% ethanol, and resuspended in sterile water.

Shotgun library construction and sequencing.

A random shotgun library of pAPEC-O103-ColBM was prepared from purified plasmid DNA. DNA was sheared, concentrated, desalted, end repaired, tailed, and size fractionated by electrophoresis. The 1.5- to 2.5-kb fraction was isolated and purified using standard methods prior to cloning into pWRIGHT. Shotgun sequencing was performed by Seqwright, Inc. (Houston, TX). The data were collected with ABI 3700 and ABI 3730xl capillary sequencers.

Assembly and annotation.

Sequencing reads were assembled using SeqMan software from DNASTAR (Madison, WI). Gap closure for pAPEC-O103-ColBM was accomplished using the pooled primer technique described by Tettelin et al. (56). Open reading frames (ORFs) in the plasmid sequence were identified using GeneQuest from DNASTAR (Madison, WI), followed by manual inspection, as previously described (23).

Comparative genomics.

Nucleotide similarities to previously described ColV and ColBM sequences were determined using a local standalone BLAST analysis (3). Protein alignment and nucleotide alignment were performed using the ClustalW algorithm in the DNASTAR package (LaserGene). A circular map was constructed using GenVision (LaserGene).

Conjugation assay.

The transmissibility of pAPEC-O103-ColBM was assessed by performing a liquid conjugation experiment (28). Briefly, 0.2 ml of donor cells in exponential growth phase was mixed with 1.8 ml of an overnight culture of recipient cells in Antibiotic 3 broth (Difco Laboratories). Mixtures were incubated overnight without shaking at 25°C, 37°C, and 42°C. Transconjugants were selected on LB agar containing a donor-inhibiting concentration of nalidixic acid (30 μg/ml) and a recipient-inhibiting concentration of streptomycin (50 μg/ml).

Triparental mating assay.

Because pAPEC-O103-ColBM was found to be non-self-transmissible, triparental mating was performed using helper plasmid pRK2013 in an effort to mobilize pAPEC-O103-ColBM into E. coli DH5α (13). The donor, recipient, and helper strains were grown to mid-logarithmic phase and then spotted either together or separately on LB agar plates and incubated overnight. The spots were then restreaked on selective agar containing 30 μg/ml nalidixic acid and 50 μg/ml streptomycin. Replica plating on agar containing 50 μg/ml kanamycin was used to verify the absence of pRK2013.

Phylogenetic typing and virulence genotyping.

Isolates were assigned to phylogenetic groups using the method of Clermont et al. (6). Using this method, isolates were assigned to one of four groups (group A, B1, B2, or D) based on the presence of two genes (chuA and yjaA) and a DNA fragment (TSPE4.C2) as determined by PCR. Boiled lysates of overnight cultures were used as a source of template DNA for this study (20). Amplification was performed with a 25-μl reaction mixture as previously described (43).

Multiplex PCR was performed to determine the presence of 49 genes or traits. Some of the multiplex panels used have been described previously (23, 24, 42, 43). The experiments included positive- and negative-control organisms. All primers were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). Strains known to possess or lack the genes of interest were examined with each amplification procedure. Experiments were performed twice. An isolate was considered to contain a gene of interest if it produced an amplicon of the expected size.

PFGE.

ExPEC strain 408 and its derivatives were subtyped by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) using the PulseNet 1-day (24- to 28-h) standardized laboratory protocol described by Ribot et al. (41). Salmonella enterica serovar Branderup H9812 (ATCC BAA-664) was used as the size standard. Restriction was carried out using XbaI (Invitrogen). DNA macrorestriction fragments were resolved on 1% SeaKem Gold agarose (Cambrex Bio Science Inc., Rockland, ME) in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA. PFGE was carried out as previously described (11, 53). Images were captured using a UV imager (Alpha Innotech, CA) and stored as .tif files.

Antimicrobial susceptibility.

ExPEC 408 and its derivatives were examined to determine their antimicrobial susceptibilities using the Sensititre CMV1AGNF plate-SIW 2004 panel (Trek Diagnostics) according to Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) (formerly NCCLS) recommendations. A 96-well microtiter plate was used to test the susceptibilities of strains to 15 different antimicrobials commonly associated with animal and human health. The antimicrobials used were amikacin (0.5 to 64 μg/ml), amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (0.25 to 64 μg/ml), ampicillin (1 to 32 μg/ml), cefoxitin (0.5 to 32 μg/ml), ceftiofur (0.12 to 8 μg/ml), ceftriaxone (0.25 to 64 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (2 to 32 μg/ml), ciprofloxacin (0.015 to 4 μg/ml), gentamicin (0.25 to 16 μg/ml), kanamycin (8 to 64 μg/ml), nalidixic acid (0.5 to 32 μg/ml), streptomycin (32 to 64 μg/ml), sulfisoxazole (16 to 512 μg/ml), tetracycline (4 to 32 μg/ml), and trimethoprim (0.12 to 4 μg/ml)-sulfamethoxazole (2.38 to 76 μg/ml). The panels were inoculated according to the manufacturer's instructions (Trek Diagnostics). Isolates were defined as susceptible or resistant by comparison to FDA- and NCCLS-recommended breakpoints for each antimicrobial agent, where the breakpoint is the minimum drug concentration above which growth of an isolate should occur. Additionally, disk diffusion was used to determine the susceptibilities of isolates to the following drugs: streptomycin, tetracycline, chloramphenicol, gentamicin, trimethoprim, ampicillin, nalidixic acid, kanamycin, sulfisoxazole, rifampin, and erythromycin.

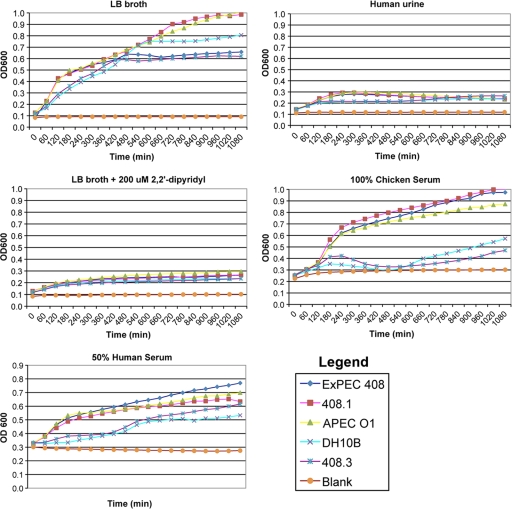

In vitro bacterial growth assays.

The abilities of ExPEC 408 and its derivatives to grow in LB broth were compared. Strains were grown overnight in 2 ml of LB broth. The next day, cell densities were calculated using spectrophotometry, and cultures were diluted in fresh LB broth to obtain a starting optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.05. Cultures were incubated at 37°C with shaking in a SpectraMax Plus384 spectrophotometer. Samples were taken every 15 min for 18 h. The results shown are the averages of two independent trials with four replicates each. In all of the growth assays described here, the size of the inoculum was limited to less than 5% of the total volume to limit dilution of the growth medium used. Viable counts were also determined by performing the same assay with 2 ml of LB broth, followed by plating of serial dilutions each hour on MacConkey agar.

Strains were also assessed to determine their abilities to survive in filtered chicken serum and filtered human serum. Strains were first grown overnight in 2 ml of LB broth. The next day, cell densities were calculated using spectrophotometry, and the cultures were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and diluted in LB broth with 100% chicken serum or 50% human serum to obtain a starting OD600 of 0.05. The cultures were incubated at 37°C with shaking in a SpectraMax Plus384 spectrophotometer. Samples were taken every 15 min for 18 h. The results shown are the averages of two independent trials with four replicates each. Viable counts were also determined by performing the same assays with 2 ml of 100% chicken serum, 90% human serum, or 75% human serum, followed by plating of serial dilutions each hour on MacConkey agar.

Strains were also assessed to determine their abilities to grow in LB broth containing the iron chelator 2,2′-dipyridyl (38). Strains were first grown overnight in 2 ml of LB broth. The next day, cell densities were calculated using spectrophotometry, the cultures were washed in PBS, and pellets were diluted in LB broth with 400 μM 2,2′-dipyridyl to obtain a starting OD600 of 0.05. The cultures were incubated at 37°C with shaking in a SpectraMax Plus384 spectrophotometer. Samples were taken every 15 min for 18 h. The results shown are the averages of two independent trials with four replicates each. Viable counts were also determined by performing the same assay with 2 ml of LB broth containing 2,2′-dipyridyl, followed by plating of serial dilutions each hour on MacConkey agar.

Strains were also assessed to determine their abilities to grow in human urine. The assay was performed as described elsewhere (45). Only urine from healthy, antibiotic-free volunteers who reported that they never had had a UTI was used for this study. Prior to the study, urine from five volunteers was collected, individually filter sterilized with 0.2-μm filters, pooled, and stored at −20°C. On the day before the assay was performed, the strains tested were grown overnight in 2 ml of LB broth (52). The next day, the cell densities were estimated using spectrophotometry, and cultures were diluted in PBS prior to inoculation into urine to obtain a starting OD600 of approximately 0.05. The cultures were incubated at 37°C with shaking in a SpectraMax Plus384 spectrophotometer. Samples were taken every 15 min for 18 h. The results shown are the averages of two independent trials with four replicates each. Viable counts were also determined by performing the same assay with 2 ml of urine, followed by plating of serial dilutions each hour on MacConkey agar.

Rat model of human bacteremia and neonatal meningitis.

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the institutional guidelines for the ethical treatment of animals at Iowa State University. ExPEC 408 and its plasmid-cured and complemented derivatives were assessed to determine their abilities to induce septicemia and meningitis in 5-day-old rats, as previously described (17). Each experimental group contained at least 20 rats, and each experiment was performed twice on separate occasions. Briefly, specific-pathogen-free Sprague-Dawley rats were inoculated via intraperitoneal injection when they were 5 days old with 200 CFU of each bacterial strain suspended in PBS. At 18 h postinoculation, 25 μl of blood was drawn from each rat and plated on MacConkey agar to determine the concentration of the strain in the blood. Rats were subsequently euthanized, and 10 μl of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was removed via cisternal puncture and plated on MacConkey agar to determine the concentration of each strain in the CSF. Brain tissues were also collected for histopathology.

Models of avian colibacillosis.

ExPEC 408 and its derivatives were assessed to determine their abilities to cause avian colibacillosis using broiler chicks, as described previously (29, 30). One-day-old chicks that were vaccinated only against Marek's disease were obtained from a commercial source, were divided into groups containing 10 chicks, and were placed in Horsfall units or in separate rooms. The chicks were given food and water ad libitum. For intratracheal inoculation, chicks were inoculated with 0.1 ml of a bacterial suspension containing 108 CFU/ml of bacteria or with 0.1 ml of PBS directly in the trachea. For subcutaneous inoculation, birds were injected with 0.1 ml of a bacterial suspension containing 107 CFU/ml of bacteria or with 0.1 ml of PBS in the back of the neck. Chicks were challenged on the day that they were received, and they were monitored for the first 6 h postchallenge on day 1 and then every 12 h for 7 days. Deaths were recorded, and the survivors were euthanatized and examined for macroscopic lesions. Strains were compared to the wild-type positive-control strain APEC O1 (27) and the negative-control strain DH5α. A lesion scoring system was used as previously described (44). Each experiment was performed twice on separate occasions.

E. coli adherence to and invasion of human BMECs.

ExPEC 408 and its derivatives were assessed to determine their abilities to adhere to and invade human brain microvascular epithelial cells (BMECs), since these activities are a prerequisite for penetration of E. coli into the central nervous system to cause meningitis. The invasion assay was performed as described by Huang et al. (19). Briefly, ∼2 × 106 mid-log-phase bacteria were added to confluent monolayers of BMECs in 96-well microtiter plates, and the plates were centrifuged to synchronize invasion. The plates were incubated for 90 min, the wells were washed, and the cells were incubated in gentamicin-containing medium to kill bacteria that were not internalized. BMECs were washed and lysed with Triton X-100. Aliquots of the lysate were diluted and plated to determine viable counts. The results shown below are the averages of three replicates. The adhesion assay was performed like the invasion assay, except that gentamicin was not used.

Statistics.

All growth rate data were analyzed using linear regression analysis (Systat, Evanston, IL) to determine the specific growth rate of each strain. A Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare lesion scores obtained in the chick experiments and bacterial counts obtained in the rat experiments. A two-tailed Student t test was used to compare differences among the growth rates and among the BMEC adherence and invasion data (51).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The complete sequence and annotation of pAPEC-O103-ColBM has been deposited in the GenBank database under accession number CP001232.

RESULTS

Sequencing of pAPEC-O103-ColBM.

A search of an ExPEC collection consisting of over 1,000 isolates was performed in an effort to identify candidate hybrid plasmids harboring both ColV virulence-associated genes and an MDR-encoding island. ExPEC strain 408, which was isolated from a laying hen with peritonitis, was identified because it contained a single plasmid harboring ColV-associated virulence genes and class 1 integron-associated genes. pAPEC-O103-ColBM was sequenced and analyzed because of the linkage of virulence and MDR on the same plasmid. Draft sequencing, assembly, and finishing were performed to obtain a single contiguous sequence with an average of 8-fold coverage spanning 124,705 bp. In this sequence, 137 ORFs that encoded sequences that were more than 80 amino acids long were identified. pAPEC-O103-ColBM can be divided into three functional modules that are involved in virulence, transfer, and antimicrobial resistance (Fig. 1). The virulence-associated module spanned approximately 55,000 bp and closely resembled the virulence-associated modules of other sequenced ColV plasmids (15, 23, 24, 34, 39). This region contained the previously described “conserved region” of the ColV PAI encoding multiple iron acquisition and transport systems (aerobactin, SitABCD, and IroBCDEN), the RepFIB replicon, the hemolysin HlyF, and the Iss protein involved in serum resistance (24). Like other sequenced ColBM plasmids, this plasmid also had a colicin-encoding region containing truncated portions of the ColV operon along with the ColBM operon (23, 57). In its PAI, however, was a 5,871-bp insertion between the sitABCD and aerobactin operons (Fig. 2). This region appears to have been acquired via a conjugative transposon, as it included a 70-bp imperfect inverted repeat region and exhibited 92% nucleotide identity with the transposase sequence for Tn1000 (GenBank accession no. AY598759). Additionally, this region contained two coding regions whose predicted protein products exhibited similarity with a manganese-dependent inorganic pyrophosphatase and a universal stress protein UspA homolog (Table 2). These products most closely match predicted proteins from Citrobacter koseri strain ATCC BAA-895, whose genome is the first sequenced genome of this bacterial species implicated in human neonatal meningitis (9). Analysis of the predicted UspA protein sequence revealed that it did not closely resemble other chromosomally encoded UspA sequences of E. coli strains. The uspA gene in the E. coli and Salmonella chromosomes has been recognized because of its roles in oxidative stress resistance, iron scavenging, motility, and adhesion, all of which are traits that are required in an extraintestinal pathogen (36), and to our knowledge this uspA homolog is the only uspA homolog introduced into a plasmid.

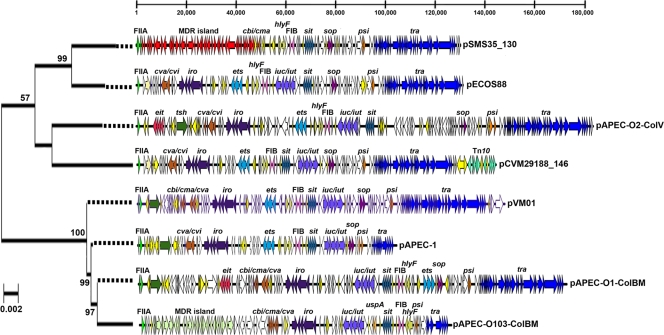

FIG. 1.

Circular map of pAPEC-O103-ColBM. The outer two circles show predicted coding regions in forward and reverse orientations, and different colors indicate different predicted functions. The next circle shows the G+C content in a 1,000-bp window with 10-bp steps. The next five circles show levels of nucleotide homology with other sequenced ColV-type plasmids. Blue indicates ≥90% homology with pAPEC-O103-ColBM, while black indicates <90% homology. The numbers on these circles indicate comparisons with pAPEC-O2-ColV (circle 1), pAPEC-O1-ColBM (circle 2), pVM01 (circle 3), pCVM29188_146 (circle 4), and pSMS-3-5_130 (circle 5). The map was created using GenVision from DNASTAR.

FIG. 2.

Linear maps of sequenced ColV and ColBM plasmids. The bar at the top indicates positions (in base pairs). The maps begin with RepFIIA and are drawn to scale. Virulence genes of interest are identified and indicated by different colors. The plasmids are ordered according to evolutionary relationships of concatenated gene sequences (hlyF, traX, finO, repA, repA1). The evolutionary history was inferred using the neighbor-joining method (54). Bootstrap consensus trees were inferred using 500 replicates. Bootstrap confidence values greater than 50% are indicated at the nodes. The tree is drawn to scale based on evolutionary distances, and dotted lines extend the branches to the plasmid maps. Distances were computed using the maximum composite likelihood method (scale bar = 0.02 base substitution per site). Phylogenetic analyses were conducted with MEGA4 (55).

TABLE 2.

Predicted proteins unique to pAPEC-O103-ColBM compared to other sequenced ColV-type plasmids

| Start site | Stop site | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 5289 | 5645 | Putative transposase subunit |

| 12369 | 11653 | Putative transposase subunit |

| 12391 | 12669 | Putative resolvase |

| 12884 | 13207 | Putative resolvase |

| 13488 | 14390 | Putative manganese-dependent inorganic pyrophosphatase |

| 16020 | 16448 | Universal stress protein UspA |

| 15085 | 14819 | Hypothetical protein |

| 15089 | 16117 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| 49878 | 48862 | Transposase protein for IS5 |

| 51219 | 51494 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| 57018 | 58109 | Replication protein RepC |

| 58111 | 60336 | Plasmid inhibition protein PifA |

| 75811 | 76338 | Putative resolvase |

| 77713 | 78663 | Putative replication protein |

| 78971 | 79786 | Putative replication protein |

| 80052 | 79783 | Hypothetical protein |

| 82733 | 83206 | Dihydrofolate reductase type I protein DhfrA1 |

| 83299 | 84090 | Aminoglycoside resistance protein AadA |

| 84254 | 84601 | Quaternary ammonium compound resistance protein QacEdelta1 |

| 84508 | 85434 | Dihydropteroate synthase protein Sul1 |

| 85562 | 86062 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| 87023 | 86238 | Putative transposase protein IstB |

| 88533 | 87010 | Putative transposase protein IstA |

| 89363 | 88635 | Partial transposase protein TniB |

| 90018 | 90734 | Putative penicillin binding protein |

| 91830 | 92252 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| 92289 | 93128 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| 93165 | 94073 | Putative macrolide 2′-phosphotransferase II |

| 96268 | 94592 | Partial transposase protein TniB |

| 97977 | 96262 | Putative transposase TniA |

| 98900 | 98016 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| 99336 | 98953 | Mercury resistance operon transcriptional regulator MerD |

| 101027 | 99333 | Mercury resistance operon mercuric reductase MerA |

| 101540 | 101079 | Mercury resistance operon transport protein MerC |

| 101848 | 101537 | Mercury resistance operon protein MerP |

| 102230 | 101826 | Mercury resistance operon mercuric transport protein MerT |

| 102601 | 102239 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

The transfer module of pAPEC-O103-ColBM spanned about 10,000 bp and was not intact, containing only finO-traXIDTSG. The traI gene in this truncated region was interrupted by an IS26 element, and the traG gene was disrupted and fused with a putative transposase element gene. This truncation was reflected phenotypically by the inability of pAPEC-O103-ColBM to self-transfer to E. coli DH5α.

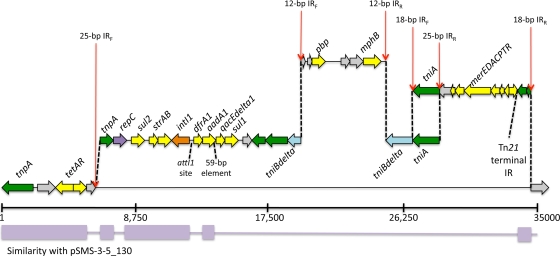

The MDR-encoding region of pAPEC-O103-ColBM spanned approximately 35,000 bp and was between the RepFIIA and RepFIB plasmid replicons. A detailed analysis of this region identified 10 resistance-associated elements (Fig. 3). The 5′ end of pAPEC-O103-ColBM's MDR-encoding module contained a portion of the transposon Tn1721, including tetAR and tnpA (8). Downstream of this region was an approximately 22-kb region flanked by 25-bp exact inverted repeats. This region contained the sul2 and strAB genes at its 5′ end, which encode sulfonamide and streptomycin resistance, respectively. Immediately downstream of strAB was a class 1 integron in an In2-like region that contained dfrA1 in the gene cassette region encoding trimethoprim resistance. This gene was in addition to the core class 1 integron genes intI1, aadA1, qacEΔ1, and sulI (32). Downstream of the class 1 integron were other typical components of In2, including tniABΔ and the merEDACPTR genes encoding mercury resistance (32). Unlike a typical In2 element, pAPEC-O103-ColBM contained an insertion in the tniBΔ gene, flanked by 12-bp exact inverted repeats, with homology to plasmid pTZ3721 in the GenBank database sequence (Fig. 4) (37). This 6.5-kb region contained the mphB gene encoding macrolide resistance and a gene exhibiting homology to a putative penicillin binding protein gene (37).

FIG. 3.

Linear map of the MDR-encoding region of pAPEC-O103-ColBM. Dashed lines indicate potential evolutionary breakpoints identified by nucleotide sequence comparisons and identified inverted repeats in the sequence. Nucleotide similarity (>90%) with pSMS35_130 is indicated below the scale (in base pairs).

FIG. 4.

Growth of bacterial strains in various growth media determined using OD600. Counts for an 18-h period are shown. Each strain was tested in quadruplicate, and each experiment was performed twice on separate occasions. The data are averages for the experiments for each time point.

pAPEC-O103-ColBM was compared to five other sequenced ColV and ColBM plasmids in an effort to better understand the evolution of these plasmids (Fig. 1). The plasmids examined were pAPEC-O1-ColBM (23), pAPEC-O2-ColV (24), pCVM29188_146 (15), pSMS35_130 (14), and pVM01 (57). Of the 137 predicted coding regions, 18 (13.1%) were shared by all 5 plasmids with a level of nucleotide similarity greater than 90%. The genes shared by all plasmids included hlyF, sitABCD, repA (RepFIB), some genes of the F transfer region, and a putative transcriptional regulator gene. If not for pSMS35_130, which lacks much of the ColV PAI, much more of this PAI, including the aerobactin and iroBCDEN operons and the iss gene, would be conserved among all of the plasmids sequenced. Most of the plasmids studied lacked the genes of the MDR-encoding island; the exception was pSMS35_130, which contained a portion of these resistance-associated genes. Overall, 43 (31.4%) of the pAPEC-O103-ColBM coding regions examined were not found in any other plasmid sequenced (Table 2). Among the predicted proteins were mobile genetic elements, replication proteins, resistance-associated proteins, proteins of unknown function, and UspA.

We also examined the current ColV pangenome based on the available plasmid sequences. The results demonstrated that there is a high degree of diversity outside the “core” ColV regions. In the six plasmids, 358 nonredundant ORFs were identified. The “core” ORFs that apparently define the typical ColV backbone include the F transfer region, portions of the ColV operon, plasmid stability genes, the RepFIB replicon, and the conserved portion of the ColV PAI. However, each plasmid had its own set of unique ORFs, and the plasmids that were the largest ColV plasmids sequenced, such as pAPEC-O2-ColV, were the plasmids with the largest numbers of unique ORFs. The ORFs were usually clusters of genes on a plasmid surrounded by IS1 elements, suggesting that they were acquired via homologous recombination. Multilocus sequence analysis was performed using genetic regions conserved in the 6 plasmids studied, including hlyF, finO, traX, repA1, and repA (Fig. 2). This analysis suggested that the plasmids fell into two lineages, a lineage containing pSMS35_130, pECOS88, pCVM29188_146, and pAPEC-O2-ColV and a lineage containing pVM01, pAPEC-1, pAPEC-O1-ColBM, and pAPEC-O103-ColBM.

Phenotypic characteristics of pAPEC-O103-ColBM.

Liquid conjugation assays in which we attempted to transfer pAPEC-O103-ColBM into E. coli DH5α were not successful. This plasmid was successfully mobilized into DH5α, however, using the helper plasmid pRK2013. pAPEC-O103-ColBM was also successfully electroporated into DH5α using streptomycin as a selectable marker. Serial passage successfully cured pAPEC-O103-ColBM from its wild-type host, and subsequent plasmid complementation via electroporation was successful (Table 1). The donor and transconjugant strains were examined to determine the presence of 49 ExPEC-associated genes and the phylogenetic type using multiplex PCR. The transconjugants had the expected gene profiles compared to the donor strain, ExPEC 408 (data not shown); that is, the transconjugant strains appeared to have acquired ColV plasmid-associated genes but not to have acquired any chromosomal genes found in ExPEC 408. Additionally, all strains belonged to the B1 phylotype. PFGE of these strains verified that they had identical chromosomal backgrounds, further suggesting that only the plasmid DNA in each transconjugant had been altered (data not shown).

ExPEC 408 and its cured and complemented derivatives were tested to determine their abilities to grow in LB broth, LB broth supplemented with 400 μM 2,2′-dipyridyl (an iron chelator), filtered human urine, 90% filtered chicken serum, and 90%, 75%, or 50% filtered human serum (Table 3 and Fig. 4). In LB broth, broth containing 400 μM 2,2′-dipyridyl, and urine, the loss of pAPEC-O103-ColBM did not correlate with attenuated growth. However, in 75 and 90% human serum, loss of the plasmid resulted in a significantly lower survival rate (P < 0.05). Complementation of the cured strain with the plasmid restored wild-type levels of growth in serum.

TABLE 3.

Growth of ExPEC 408 and its derivatives in various media as determined using viable counts

| Strain | Growth rate ina: |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LB broth (pH 7.0) | LB broth (pH 5.0) | LB broth + 400 μM 2,2′-dipyridyl | 90% Chicken serum | 75% Human serum | 90% Human serum | Human urine | |

| APEC O1 | 0.76 | 0.51 | 0.29 | 0.78 | 0.04 | 0.10 | NDb |

| APEC O2 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.69 |

| DH5α | 0.44 | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.31 | −1 | −1 | 0.16 |

| ExPEC 408 | 0.76 | 0.56 | 0.20c | 0.75 | −0.15c | −0.09c | 0.66 |

| 408.1 | 0.75 | 0.57 | 0.18c | 0.77 | −0.30d | −0.22d | 0.59 |

| 408.2 | 0.76 | 0.58 | 0.21c | 0.74 | −0.13c | −0.12c | 0.63 |

The growth rate was determined by calculating the slope of log-transformed data during exponential growth. Negative values reflect a decline in survival as determined using viable counts.

ND, not determined.

Significantly different (P < 0.05) than the value for the known positive control (APEC O1 or APEC O2) as determined using a two-tailed Student t test.

Significantly different (P < 0.05) than the value for the known positive control and ExPEC wild-type strain 408 as determined using a two-tailed Student t test.

Contribution of pAPEC-O103-ColBM to the pathogenesis of disease in multiple animal models.

ExPEC 408 and its derivatives were tested using several animal models of human and avian disease. Two models of avian colibacillosis were tested. In the chick models of avian colibacillosis, the plasmid-cured strain showed attenuation of virulence compared to wild-type strain and the plasmid-complemented strain (Table 4). The differences in both the intratracheal and subcutaneous models were statistically significant (P < 0.05).

TABLE 4.

Results for chick infection models of avian colibacillosis

| Strain | Mean lesion score for subcutaneous modela | Mean lesion score for intratracheal modela |

|---|---|---|

| DH5α | 0b | 0f |

| APEC O1 | 8.33c | 7.08c |

| ExPEC 408 | 3.08d | 3.50d |

| 408.1 | 0.58e | 0.17f |

| 408.2 | 2.50d | 2.33d |

The range of lesion scores was 0 to 10.

Significantly different (P < 0.05) than the scores for APEC O1, ExPEC 408, 408.1, and 408.2.

Significantly different (P < 0.05) than the scores for DH5α, ExPEC 408, 408.1, and 408.2.

Significantly different (P < 0.05) than the scores for DH5α, APEC O1, and 408.1.

Significantly different (P < 0.05) than the scores for DH5α, APEC O1, ExPEC 408, and 408.2.

Significantly different (P < 0.05) than the scores for APEC O1, ExPEC 408, and 408.2.

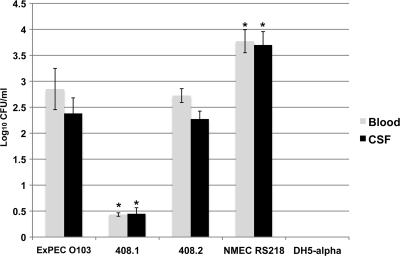

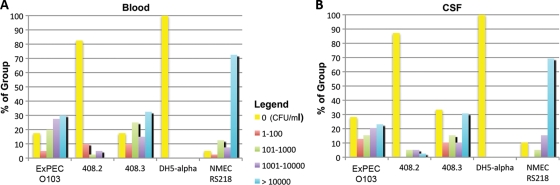

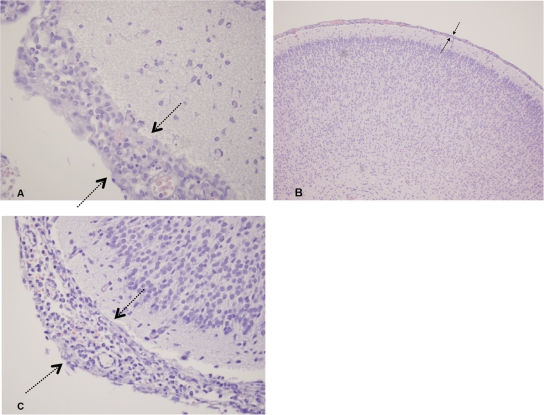

In the rat model of human bacteremia and meningitis, ExPEC 408 caused both bacteremia and meningitis (Fig. 5). The plasmid-cured strain was significantly attenuated compared to the wild type and the complemented strain. The viable counts of bacteria isolated from blood and CSF paralleled these findings; most of the rats inoculated with the plasmid-cured strain and the negative-control rats did not contain bacteria in their blood or CSF (Fig. 6), whereas the viable counts for rats infected with the wild type and rats infected with the complemented strain were similar. It is also interesting that the viable counts for ExPEC 408 and the complemented strain in the blood and CSF were approximately 10-fold less than the viable counts for the positive-control strain, prototypic NMEC strain RS218. The counts for these strains were about 100-fold higher than those for the ExPEC 408 plasmid-cured derivative (Fig. 6). A histopathology analysis was performed using brain tissue from rats infected with ExPEC 408 or its derivatives (Fig. 7). When wild-type ExPEC strain 408 and its plasmid-complemented derivative were used, moderate diffuse meningitis was observed, and neutrophils and lymphocytes were scattered throughout the cerebral parenchyma and areas of mild edema. The plasmid-cured strain did not produce any lesions. ExPEC 408 and its derivative were also tested to determine their abilities to adhere to and invade human BMECs in order to model the ability to cross the blood-brain barrier. ExPEC 408 and its plasmid-complemented derivative adhered to and invaded human BMECs at a significantly higher rate (P < 0.05) than the plasmid-cured derivative (Table 5). Again, the association and infectivity values for the wild-type and complemented strains were lower than those for the archetypal strain RS218 but higher than those for the plasmid-cured strain.

FIG. 5.

Average concentrations of bacteria in the blood and CSF of rats infected with ExPEC 408 and its derivatives. The error bars indicate the average results for two experimental trials, and at least 11 rats were used for experimental group. An asterisk indicates that a value is significantly different (P < 0.05) from the value for ExPEC 408.

FIG. 6.

Percentages of animals in each experimental group in the rat model containing different concentrations of bacteria in (A) blood and (B) CSF.

FIG. 7.

Histopathology of rat brain tissue 18 h after inoculation of ExPEC wild-type strain 408 (A), ExPEC 408 cured of pAPEC-O103-ColBM (B), and ExPEC 408 complemented with pAPEC-O103-ColBM (C). In panels A and C, moderate diffuse meningitis was observed (arrows), with neutrophils and lymphocytes scattered throughout the cerebral parenchyma and mild areas of edema. There were similar inflammatory cells that were scattered throughout the cerebral parenchyma and mild areas of edema (not shown). The plasmid-cured strain (B) (the lower magnification shows a larger region) did not cause any lesions.

TABLE 5.

Association with and invasion of human BMECs by ExPEC 408 and its derivatives

| E. coli strain | % Association based on total number of cells | % Invasion compared to invasion by RS218 |

|---|---|---|

| NMEC RS218 | 5.6 | 100 |

| ExPEC 408 | 12.4 | 21.3 |

| 408.1 | 7.7a | 1.3a |

| 408.2 | 12.1 | 24.7 |

Significantly different (P < 0.05) than the value for ExPEC 408, as calculated with a two-tailed Student t test.

Decreased drug susceptibility conferred by pAPEC-O103-ColBM.

ExPEC 408 and its derivatives were also examined to determine their susceptibilities to various antimicrobial agents (Table 6). Using observed resistance phenotypes based on MICs and disk diffusion results, pAPEC-O103-ColBM was found to confer decreased susceptibilities to streptomycin (strAB), sulfisoxazole (sul2 and sulI), tetracycline (tetAR), erythromycin (mphB), and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (sul2, sulI, and dhfrA1). However, decreased susceptibility to ampicillin was not conferred by pAPEC-O103-ColBM, suggesting that the penicillin binding protein homolog is not active against this class of antimicrobial agents.

TABLE 6.

Antimicrobial susceptibilities of ExPEC 408 and its derivatives

| Antibiotic | Susceptibility ofa: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ExPEC 408 | 408.1 | DH5α | 408.3 | |

| Streptomycin | R | S | S | R |

| Tetracycline | R | I | S | R |

| Chloramphenicol | S | S | S | S |

| Gentamicin | S | S | S | S |

| Trimethoprim | R | R | S | I |

| Ampicillin | I | I | S | S |

| Nalidixic acid | I | I | R | R |

| Kanamycin | I | I | S | S |

| Sulfisoxazole | R | R | S | R |

| Rifampin | S | S | S | S |

| Erythromycin | R | S | S | R |

S, sensitive; R, resistant; I, intermediate.

Prevalence of ColV and ColBM plasmids in ExPEC.

Using markers for the ColV and ColBM operons and genes specific for pAPEC-O103-ColBM, ExPEC populations were examined to determine the prevalence of these plasmids (Table 7). High percentages of the isolates in the APEC and NMEC populations contained a ColV or ColBM plasmid (66.7% and 58.2%, respectively), whereas UPEC isolates generally lacked this plasmid (5.2%). Of the isolates containing a ColV or ColBM plasmid, nearly one-third contained a ColBM plasmid, and approximately 15 to 16% of the ColV or ColBM plasmids contained genes unique to pAPEC-O103-ColBM compared to the other sequenced ColV and ColBM plasmids.

TABLE 7.

Prevalence of ColV and ColBM plasmids in the ExPEC subpathotypes

| Plasmids | % of strains |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| APEC (n = 96) | NMEC (n = 91) | UPEC (n = 96) | |

| ColV or ColBM type (hlyF, repA, iss, iroN, cvaC, or cma) | 66.7 | 58.2 | 5.2 |

| ColBM type (hlyF, repA, iss, iroN, or cma) | 31.3 | 20.9 | 1 |

| pAPEC-O103-ColBM type harboring uspA (hlyF, repA, iss, iroN, cma, or uspA) | 16.7 | 15.4 | 2.1 |

DISCUSSION

ColV and ColBM plasmids have been associated with a variety of traits, including serum resistance (4), iron acquisition (7, 48), resistance to chlorine and disinfectants (16), growth in human urine (49), improved growth under acidic pH conditions (40), bacteriophage resistance (18), establishment of avian colibacillosis (49, 60), and establishment of septicemia and urinary tract infections (2, 39). Here, a ColBM plasmid was sequenced and analyzed because of its mosaic nature; it contains both virulence-associated and drug resistance-associated genes. The ExPEC strain harboring this plasmid was isolated from a peritonitis lesion in a commercial layer hen. In subcutaneous and intratracheal models mimicking aspects of avian pathogenesis, ExPEC 408 cured of its plasmid was significantly attenuated compared to the wild-type strain. As observed for other avian E. coli strains belonging to more typically encountered serogroups, such as serogroups O2 and O78, it appears that this serogroup O103 isolate owes much of its virulence for birds to its plasmid.

In addition to contributing to avian disease, pAPEC-O103-ColBM also contributed to disease in an animal model of human septicemia and human meningitis. Surprisingly, curing of pAPEC-O103-ColBM from its host did not affect the host's ability to grow in chicken serum, low-iron medium, or urine, as previously described for the ColV and ColBM plasmids (33, 59). Perhaps this lack of a significant change in the phenotype upon curing reflects the presence of redundant systems on ExPEC 408's chromosome and hints that ExPEC 408 is a coincidental host in birds. Similarly, introduction of the plasmid into strain DH5α did not increase the ability of this strain to grow in these media, suggesting that a certain chromosomal background is required for this plasmid to exhibit its effects. Despite its ability to cause disease in several models of infection or survival, ExPEC 408 lacked most the 49 ExPEC-associated or virulence-associated genes examined here, including some genes and/or operons associated with iron acquisition. The absence of typical ExPEC chromosomal virulence factors in ExPEC 408 was reflected by the fact that it belonged to the B1 phylogenetic group (22). Thus, several possibilities could account for ExPEC 408's ability to cause disease. These include the possibility that there are as-yet-unidentified virulence factors in ExPEC 408's chromosome, the possibility that pAPEC-O103-ColBM carries known or novel virulence factors that contribute to disease, or a combination of both. The latter seems to be the most likely explanation. However, it is evident from the results that pAPEC-O103-ColBM contributes to establishment of both human disease and avian disease.

Several studies have identified ColV plasmids in ExPEC isolates obtained from the CSF of neonatal meningitis patients (2, 10, 26, 39). However, these isolates belong to common serogroups of NMEC strains, such as serogroups O18, O45, and O7. Because these strains contain other essential NMEC virulence factors, it has been difficult to elucidate the precise role of the ColV and ColBM plasmids in establishment of neonatal meningitis in isolates possessing other typical NMEC virulence factors. ExPEC 408 belongs to the O103 serogroup, a serogroup not known for its role in human neonatal meningitis. ExPEC 408 also lacks the K1 capsule, the ibeA gene, S fimbriae, and cnf1, all of which are chromosomal traits known to be involved in translocation across the blood-brain barrier (5). A ColV plasmid from an O45:K1 human isolate was recently associated with the ability of ExPEC to establish septicemia in the rat model (39). Here, a ColBM plasmid from an avian isolate behaved similarly, but it was also found to contribute to the overall establishment of meningitis and to contribute to the adhesion and invasion of human BMECs. Since many NMEC isolates appear to possess ColV or ColBM plasmids, it is possible that these plasmids play an important role in establishment of human neonatal meningitis in some strains. Certainly, studies have demonstrated a role for some ColV-associated genes, such as iroN, in the invasion of extraintestinal cell types (12). Further examination of our ExPEC collections showed that NMEC isolates harbored ColV and ColBM plasmids at ratios very similar to those for APEC isolates (Table 7). Certainly, there is evidence for a food-borne link between the two groups (25). At the very least, it appears that at least some NMEC isolates rely on these plasmid types for establishment of septicemia and/or meningitis in the neonatal human host.

The hosts of pSMS35_130 and pAPEC-O103-ColBM were isolated from environments where antimicrobial pressures were likely to be present (14). The acquisition of MDR-encoding virulence plasmids by environmental strains is disturbing, since these plasmids provide a means for MDR with apparently high concentrations and also provide selectable virulence. The resistance mechanisms employed by pAPEC-O103-ColBM are typical of the resistance mechanisms of bacterial isolates found in the poultry environment (47). Interestingly, th MDR region described here apparently evolved differently than that of pSMS35_130. While the pSMS35_130 MDR-encoding region appears to have evolved via integration of DNA into multiple IS26 “hotspots,” the MDR-encoding region of pAPEC-O103-ColBM appears to have evolved in a way more typical of F plasmids. For example, pAPEC-O103-ColBM contains an In2-like element originally described by Liebert et al., and this region alone confers resistance to at least five antimicrobial agents (32). It appears that in this region on pAPEC-O103-ColBM an interesting insertion occurred via 12-bp inverted repeats, and this region contains a gene that confers macrolide resistance but is largely uncharacterized. Finally, the entire In2 region appears to have been inserted in a region sharing homology with the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium IncI1 plasmid R64 (GenBank accession no. AP005147), since the sequence surrounding In2 shares homology at both ends with plasmid R64, and this region is bounded by transposable elements in pAPEC-O103-ColBM. Thus, pAPEC-O103-ColBM appears to have undergone stepwise evolution involving introduction of an MDR-encoding region that evolved via multiple recombinational events.

In conclusion, we determined the sequence of an MDR-encoding ColBM virulence plasmid from an avian ExPEC isolate and characterized this plasmid. This plasmid contributes to the key steps in establishment of human neonatal meningitis and avian colibacillosis, suggesting that it confers zoonotic capabilities on its ExPEC host. ColV and ColBM plasmids appear to be common in NMEC isolates, irrespective of the presence of chromosome-encoded NMEC virulence factors. The emergence of ExPEC strains with MDR and zoonotic potential encoded by transmissible elements is alarming and should prompt further efforts to prevent and control the dissemination of the plasmids conferring such abilities.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by National Science Foundation grant EFO062666 (L.K.N. and T.J.J.), by USDA Formula Funds administered through Iowa State University (L.K.N. and T.J.J.), by the Dean's Office in the College of Veterinary Medicine at Iowa State University (L.K.N.), and by the University of Minnesota College of Veterinary Medicine (T.J.J.).

Editor: S. M. Payne

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 16 February 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aguero, M. E., H. Harrison, and F. C. Cabello. 1983. Increased frequency of ColV plasmids and mannose-resistant hemagglutinating activity in an Escherichia coli K1 population. J. Clin. Microbiol. 18:1413-1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguero, M., G. de la Fuente, E. Vivaldi, and F. Cabello. 1989. ColV increases the virulence of Escherichia coli K1 strains in animal models of neonatal meningitis and urinary infection. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 178:211-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altschul, S., T. Madden, A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Binns, M., J. Mayden, and R. Levine. 1982. Further characterization of complement resistance conferred on Escherichia coli by the plasmid genes traT of R100 and iss of colV,I-K94. Infect. Immun. 35:654-659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonacorsi, S., and E. Bingen. 2005. Molecular epidemiology of Escherichia coli causing neonatal meningitis. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 295:373-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clermont, O., S. Bonacorsi, and E. Bingen. 2000. Rapid and simple determination of the Escherichia coli phylogenetic group. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4555-4558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Lorenzo, V., A. Bindereif, B. H. Paw, and J. B. Neilands. 1986. Aerobactin biosynthesis and transport genes of plasmid ColV-K30 in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 165:570-578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diver, W. P., J. Grinsted, D. C. Fritzinger, N. L. Brown, J. Altenbuchner, P. Rogowsky, and R. Schmitt. 1983. DNA sequences of and complementation by the tnpR genes of Tn21, Tn501 and Tn1721. Mol. Gen. Genet. 191:189-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doran, T. I. 1999. The role of Citrobacter in clinical disease of children: review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 28:384-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ewers, C., G. Li, H. Wilking, S. Kiessling, K. Alt, E. M. Antao, C. Laturnus, I. Diehl, S. Glodde, T. Homeier, U. Bohnke, H. Steinruck, H. C. Philipp, and L. H. Wieler. 2007. Avian pathogenic, uropathogenic, and newborn meningitis-causing Escherichia coli: how closely related are they? Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 297:163-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fakhr, M. K., J. S. Sherwood, J. Thorsness, and C. M. Logue. 2006. Molecular characterization and antibiotic resistance profiling of Salmonella isolated from retail turkey meat products. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 3:366-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feldmann, F., L. J. Sorsa, K. Hildinger, and S. Schubert. 2007. The salmochelin siderophore receptor IroN contributes to invasion of urothelial cells by extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli in vitro. Infect. Immun. 75:3183-3187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Figurski, D. H., and D. R. Helinski. 1979. Replication of an origin-containing derivative of plasmid RK2 dependent on a plasmid function provided in trans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 76:1648-1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fricke, W. F., M. S. Wright, A. H. Lindell, D. M. Harkins, C. Baker-Austin, J. Ravel, and R. Stepanauskas. 2008. Insights into the environmental resistance gene pool from the genome sequence of the multidrug-resistant environmental isolate Escherichia coli SMS-3-5. J. Bacteriol. 190:6779-6794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fricke, W. F., P. F. McDermott, M. K. Mammel, S. Zhao, T. J. Johnson, D. A. Rasko, P. J. Fedorka-Cray, A. Pedroso, J. M. Whichard, J. E. Leclerc, D. G. White, T. A. Cebula, and J. Ravel. 2009. Antimicrobial resistance-conferring plasmids with similarity to virulence plasmids from avian pathogenic Escherichia coli strains in Salmonella enterica serovar Kentucky isolates from poultry. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:5963-5971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hicks, S. J., and R. J. Rowbury. 1986. Virulence plasmid-associated adhesion of Escherichia coli and its significance for chlorine resistance. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 61:209-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Houdouin, V., S. Bonacorsi, N. Brahimi, O. Clermont, X. Nassif, and E. Bingen. 2002. A uropathogenicity island contributes to the pathogenicity of Escherichia coli strains that cause neonatal meningitis. Infect. Immun. 70:5865-5869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu, Y. 1992. The effect of plasmids on the resistance of E. coli to phages. Wei Sheng Wu Xue Bao 32:456-458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang, S. H., C. Wass, Q. Fu, N. V. Prasadarao, M. Stins, and K. S. Kim. 1995. Escherichia coli invasion of brain microvascular endothelial cells in vitro and in vivo: molecular cloning and characterization of invasion gene ibe10. Infect. Immun. 63:4470-4475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson, J. R., and A. L. Stell. 2000. Extended virulence genotypes of Escherichia coli strains from patients with urosepsis in relation to phylogeny and host compromise. J. Infect. Dis. 181:261-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson, J. R., E. Oswald, T. T. O'Bryan, M. A. Kuskowski, and L. Spanjaard. 2002. Phylogenetic distribution of virulence-associated genes among Escherichia coli isolates associated with neonatal bacterial meningitis in the Netherlands. J. Infect. Dis. 185:774-784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson, J. R., M. A. Kuskowski, A. Gajewski, S. Soto, J. P. Horcajada, M. T. Jimenez de Anta, and J. Vila. 2005. Extended virulence genotypes and phylogenetic background of Escherichia coli isolates from patients with cystitis, pyelonephritis, or prostatitis. J. Infect. Dis. 191:46-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson, T. J., S. J. Johnson, and L. K. Nolan. 2006. Complete DNA sequence of a ColBM plasmid from avian pathogenic Escherichia coli suggests that it evolved from closely related ColV virulence plasmids. J. Bacteriol. 188:5975-5983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson, T. J., K. E. Siek, S. J. Johnson, and L. K. Nolan. 2006. DNA sequence of a ColV plasmid and prevalence of selected plasmid-encoded virulence genes among avian Escherichia coli strains. J. Bacteriol. 188:745-758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson, T. J., C. M. Logue, Y. Wannemuehler, S. Kariyawasam, C. Doetkott, C. DebRoy, D. G. White, and L. K. Nolan. 2009. Examination of the source and extended virulence genotypes of Escherichia coli contaminating retail poultry meat. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 6:657-667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson, T. J., Y. Wannemuehler, S. J. Johnson, A. L. Stell, C. Doetkott, J. R. Johnson, K. S. Kim, L. Spanjaard, and L. K. Nolan. 2008. Comparison of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli strains from human and avian sources reveals a mixed subset representing potential zoonotic pathogens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:7043-7050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson, T. J., S. Kariyawasam, Y. Wannemuehler, P. Mangiamele, S. J. Johnson, C. Doetkott, J. A. Skyberg, A. M. Lynne, J. R. Johnson, and L. K. Nolan. 2007. The genome sequence of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli strain O1:K1:H7 shares strong similarities with human extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli genomes. J. Bacteriol. 189:3228-3236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson, T. J., C. W. Giddings, S. M. Horne, P. S. Gibbs, R. E. Wooley, J. Skyberg, P. Olah, R. Kercher, J. S. Sherwood, S. L. Foley, and L. K. Nolan. 2002. Location of increased serum survival gene and selected virulence traits on a conjugative R plasmid in an avian Escherichia coli isolate. Avian Dis. 46:342-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kariyawasam, S., B. N. Wilkie, and C. L. Gyles. 2004. Resistance of broiler chickens to Escherichia coli respiratory tract infection induced by passively transferred egg-yolk antibodies. Vet. Microbiol. 98:273-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kariyawasam, S., B. N. Wilkie, and C. L. Gyles. 2004. Construction, characterization, and evaluation of the vaccine potential of three genetically defined mutants of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli. Avian Dis. 48:287-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim, K. S. 12 October 2006, posting date. Meningitis-associated Escherichia coli. In A. Böck, R. Curtiss III, J. B. Kaper, P. D. Karp, F. C. Neidhardt, T. Nyström, J. M. Slauch, C. L. Squires, and D. Ussery (ed.), EcoSal—Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. ASM Press, Washington, DC. http://www.ecosal.org.

- 32.Liebert, C. A., R. M. Hall, and A. O. Summers. 1999. Transposon Tn21, flagship of the floating genome. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63:507-522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lynne, A. M., J. A. Skyberg, C. M. Logue, C. Doetkott, S. L. Foley, and L. K. Nolan. 2007. Characterization of a series of transconjugant mutants of an avian pathogenic Escherichia coli isolate for resistance to serum complement. Avian Dis. 51:771-776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mellata, M., J. W. Touchman, and R. Curtiss. 2009. Full sequence and comparative analysis of the plasmid pAPEC-1 of avian pathogenic E. coli chi7122 (O78:K80:H9). PLoS One 4:e4232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moulin-Schouleur, M., M. Reperant, S. Laurent, A. Bree, S. Mignon-Grasteau, P. Germon, D. Rasschaert, and C. Schouler. 2007. Extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli strains of avian and human origin: link between phylogenetic relationships and common virulence patterns. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:3366-3376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nachin, L., U. Nannmark, and T. Nystrom. 2005. Differential roles of the universal stress proteins of Escherichia coli in oxidative stress resistance, adhesion, and motility. J. Bacteriol. 187:6265-6272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Noguchi, N., J. Katayama, and M. Sasatsu. 2000. A transposon carrying the gene mphB for macrolide 2′-phosphotransferase II. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 192:175-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ouyang, Z., and R. Isaacson. 2006. Identification and characterization of a novel ABC iron transport system, fit, in Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 74:6949-6956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peigne, C., P. Bidet, F. Mahjoub-Messai, C. Plainvert, V. Barbe, C. Medigue, E. Frapy, X. Nassif, E. Denamur, E. Bingen, and S. Bonacorsi. 2009. The plasmid of neonatal meningitis Escherichia coli strain S88 (O45:K1:H7) is closely related to avian pathogenic E. coli plasmids and is associated with high level bacteremia in neonatal rat meningitis model. Infect. Immun. 77:2272-2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raja, N., M. Goodson, W. C. Chui, D. G. Smith, and R. J. Rowbury. 1991. Habituation to acid in Escherichia coli: conditions for habituation and its effects on plasmid transfer. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 70:59-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ribot, E. M., M. A. Fair, R. Gautom, D. N. Cameron, S. B. Hunter, B. Swaminathan, and T. J. Barrett. 2006. Standardization of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis protocols for the subtyping of Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella, and Shigella for PulseNet. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 3:59-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rodriguez-Siek, K. E., C. W. Giddings, C. Doetkott, T. J. Johnson, and L. K. Nolan. 2005. Characterizing the APEC pathotype. Vet. Res. 36:241-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rodriguez-Siek, K. E., C. W. Giddings, C. Doetkott, T. J. Johnson, M. K. Fakhr, and L. K. Nolan. 2005. Comparison of Escherichia coli isolates implicated in human urinary tract infection and avian colibacillosis. Microbiology 151:2097-2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosenberger, J. K., P. A. Fries, S. S. Cloud, and R. A. Wilson. 1985. In vitro and in vivo characterization of avian Escherichia coli. II. Factors associated with pathogenicity. Avian Dis. 29:1094-1107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Russo, T. A., U. B. Carlino, A. Mong, and S. T. Jodush. 1999. Identification of genes in an extraintestinal isolate of Escherichia coli with increased expression after exposure to human urine. Infect. Immun. 67:5306-5314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sanderson, K. E., P. R. MacLachlan, and A. Hessel. 1995. Electrotransformation in Salmonella. Methods Mol. Biol. 47:115-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singer, R. S., and C. L. Hofacre. 2006. Potential impacts of antibiotic use in poultry production. Avian Dis. 50:161-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Skyberg, J. A., T. J. Johnson, and L. K. Nolan. 2008. Mutational and transcriptional analyses of an avian pathogenic Escherichia coli ColV plasmid. BMC Microbiol. 8:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Skyberg, J. A., T. J. Johnson, J. R. Johnson, C. Clabots, C. M. Logue, and L. K. Nolan. 2006. Acquisition of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli plasmids by a commensal E. coli isolate enhances its abilities to kill chicken embryos, grow in human urine, and colonize the murine kidney. Infect. Immun. 74:6287-6292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith, H. W., and M. B. Huggins. 1976. Further observations on the association of the colicine V plasmid of Escherichia coli with pathogenicity and with survival in the alimentary tract. J. Gen. Microbiol. 92:335-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Snedecor, G. W., and W. G. Cochran. 1989. Statistical methods. Iowa State University Press, Ames, IA.

- 52.Stamm, W. E. 2001. An epidemic of urinary tract infections? N. Engl. l J. Med. 345:1055-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Struelens, M. J. 1996. Consensus guidelines for appropriate use and evaluation of microbial epidemiologic typing systems. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2:2-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tamura, K., M. Nei, and S. Kumar. 2004. Prospects for inferring very large phylogenies by using the neighbor-joining method. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:11030-11035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tamura, K., J. Dudley, M. Nei, and S. Kumar. 2007. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24:1596-1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tettelin, H., D. Radune, S. Kasif, H. Khouri, and S. L. Salzberg. 1999. Optimized multiplex PCR: efficiently closing a whole-genome shotgun sequencing project. Genomics 62:500-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tivendale, K. A., A. H. Noormohammadi, J. L. Allen, and G. F. Browning. 2009. The conserved portion of the putative virulence region contributes to virulence of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli. Microbiology 155:450-460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Waters, V., and J. Crosa. 1991. Colicin V virulence plasmids. Microbiol. Rev. 55:437-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Williams, P. H., and N. H. Carbonetti. 1986. Iron, siderophores, and the pursuit of virulence: independence of the aerobactin and enterochelin iron uptake systems in Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 51:942-947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wooley, R. E., L. K. Nolan, J. Brown, P. S. Gibbs, C. W. Giddings, and K. S. Turner. 1993. Association of K-1 capsule, smooth lipopolysaccharides, traT gene, and colicin V production with complement resistance and virulence of avian Escherichia coli. Avian Dis. 37:1092-1096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xie, Y., V. Kolisnychenko, M. Paul-Satyaseela, S. Elliott, G. Parthasarathy, Y. Yao, G. Plunkett III, F. R. Blattner, and K. S. Kim. 2006. Identification and characterization of Escherichia coli RS218-derived islands in the pathogenesis of E. coli meningitis. J. Infect. Dis. 194:358-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]