Abstract

According to a highly polymorphic region in the lytA gene, encoding the major autolysin of Streptococcus pneumoniae, two different families of alleles can be differentiated by PCR and restriction digestion. Here, we provide evidence that this polymorphic region arose from recombination events with homologous genes of pneumococcal temperate phages.

Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus) is currently the main cause of acute otitis media, sinusitis, pneumonia requiring hospitalization in adults, and meningitis. These infections cause substantial morbidity and mortality worldwide (31). The three standard tests used in clinical laboratories to differentiate pneumococcus from other alpha-hemolytic streptococci are optochin (Opt) sensitivity, immunological reaction with type-specific antisera (capsular reaction or quellung test), and bile or deoxycholate (Doc) solubility (38). The property of bile solubility was first reported by Neufeld in 1900 (40) and is attributed to triggering of the major pneumococcal autolysin, LytA, an N-acetylmuramoyl-l-alanine amidase (NAM-amidase; EC 3.5.1.28) (30). This amidase is considered an important virulence factor of S. pneumoniae (6, 28, 41, 45).

Pneumococcal LytA (here designated LytASpn) exhibits a modular organization whereby the amino (N)-terminal domain acts as the enzyme's catalytic region and the carboxy (C)-terminal domain (choline-binding domain; ChBD) features a tandem of 7 repeated motifs involved in recognizing the choline residues present in the cell wall teichoic acids (for reviews, see references 36 and 37). LytA enzymes belong to the amidase_2 family of proteins (PF01510) (http://pfam.sanger.ac.uk/).

It is now well known that Streptococcus pseudopneumoniae and other streptococci of the mitis group (SMG) also synthesize a LytA-like NAM-amidase. However, and in sharp contrast with LytASpn, the LytASMG enzymes were inhibited by 1% Doc (43). As a consequence of this inhibition, SMG isolates are unable to lyse with Doc (Doc− phenotype), although they may still harbor a lytA-like gene (4, 12, 20, 34, 43, 55). These Doc− isolates are frequently nontypeable and/or resistant to optochin. Moreover, while lytASpn alleles are 957 bp long, SMG lytA alleles (951 bp) show a characteristic 6-bp deletion (ACAGGC) between nucleotide positions 868 and 873, which in the sixth repeated motif of LytASpn amidase codes for Thr290-Gly291 (43). Altogether, the main difference between the S. pneumoniae and SMG lytA alleles resides in 102 nucleotide positions (including the 6 bp missing from the SMG alleles). These nucleotides are perfectly conserved in all the S. pneumoniae alleles examined, as are the corresponding nucleotides in the SMG alleles (34).

Prophages seem to have an important role in S. pneumoniae biology, since it is now clear that more than half of all clinical pneumococcal isolates are lysogenic (47, 50). Especially important are the enzymes (endolysins) involved in cell lysis that are encoded by these phages. Interestingly, all pneumococcal prophages reported to date code for a 318-amino-acid-long NAM-amidase (LytAPPH) that closely resembles the bacterial LytA enzyme. This characteristic was first reported for the temperate phages HB-3 (48), MM1 (42), and VO1 (44), and recently, 11 more prophages have been added to the list (23, 49). However, all previously reported lytic phages infecting S. pneumoniae carry genes that code for lysozymes (as do the so-called Cp family of phages) or for NAM-amidases (phage Dp-1), but in Dp-1, the endolysin belongs to a protein family (amidase_5; PF05382) different from that of S. pneumoniae (amidase_2) (25). Two temperate bacteriophages of Streptococcus mitis, φB6 and φHER, also code for a LytASpn-like endolysin of 318 amino acid residues (51), whereas the EJ-1 inducible prophage isolated from S. mitis 101 harbors a gene (ejl) with the characteristic deletion shown by lytASMG alleles (11).

The most significant characteristics of the bacterial strains and temperate phages analyzed here are listed in Table 1. We identified 112 entries in the databases (corresponding to 30 different sequence types [STs]) that fulfilled the requirements established, i.e., at least 900 nucleotides of the lytA gene available and no indeterminate nucleotides. Accessible lytA sequences corresponded to 58 pneumococcal isolates (26 lytASpn alleles), 28 SMG (23 lytASMG alleles), 23 pneumococcal prophages (19 lytAPPH alleles), and 3 SMG prophages (3 lytASPH alleles) (last date accessed, 20 January 2010). The relatedness between STs was shown as a dendrogram, constructed by the unweighted pair group cluster method with arithmetic averages from the matrix of allelic mismatches between the STs. Multiple sequence alignments of the lytA alleles were generated with the Clustal W 2.0 program (33). Pairwise evolutionary distances (PED) (estimated number of substitutions per 100 bases) were determined with the Distances program (10) with the correction adequate to each case. Tree construction methods and bootstrap analysis were implemented using MEGA version 4.0 (52).

TABLE 1.

lytA alleles analyzed in this study

| Gene/family (protein) and allele | Strain/phage designation (accession no.) | Type/groupa | Sequence type (allelic profile) | Length (nt)b | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pneumococcus | |||||

| 1_Spn/B (1) | Rst7 (M13812) | Nc | 128 (7,5,1,5,10,7,15,18) | 957 | 24 |

| R800 (Z34303) | Nc | 128 | 957 | 39 | |

| R6 (AE008540) | Nc | 128 | 957 | 29 | |

| D39 (CP000410) | 2 | 128 | 957 | 32 | |

| 2_Spn/B (2) | TIGR4 (AE007483) | 4 | 205 (10,5,4,5,13,10,18) | 957 | 53 |

| CDC1873-00 (NZ_ABFS01000011) | 6A | 376 (6,11,1,1,15,72,77) | 957 | Unpublished | |

| SP6-BS73 (NZ_ABAA01000016) | 6A | 460 (5,7,4,10,10,1,27) | 957 | 27 | |

| CDC0288-04 (NZ_ABGF01000008) | 12F | 220 (10,20,14,1,9,1,29) | 957 | Unpublished | |

| CDC3059-06 (NZ_ABGG01000012) | 19A | 199 (8,13,14,4,17,4,14) | 957 | Unpublished | |

| JJA (CP000919) | 14 | 66 (2,8,2,4,6,1,1) | 957 | Unpublished | |

| 150 (AF345845) | 12 | 940 | Unpublished | ||

| 3_Spn/B (2) | 147 (AF345844) | 29 | 937 | Unpublished | |

| 4_Spn/A (3) | 494 (AJ243399) | 3 | 906 | 54 | |

| 5_Spn/A (10) | 670c | 6B | 90 (5,6,1,2,6,3,4) | 957 | Unpublished |

| 670 (AJ243400) | 6B | 906 | 54 | ||

| 6_Spn/B (9) | INV104Bd | 1 | 227 (12,5,13,5,17,4,20) | 957 | Unpublished |

| 7_Spn/B (2) | PN58 (AJ243403) | 19A | 906 | 54 | |

| 8_Spn/A (12) | VA1 (AJ243404) | 19 | 906 | 54 | |

| 9_Spn/B (13) | CL18 (AJ243405) | 10 | 906 | 54 | |

| 10_Spn/A (3) | 1012 (AJ243406) | 35 | 906 | 54 | |

| 11_Spn/A (3) | PN15 (AJ243407) | 12 | 906 | 54 | |

| 12_Spn/A (11) | 234 (AJ243408) | 23F | 906 | 54 | |

| 233 (AJ243409) | 23F | 906 | 54 | ||

| 13_Spn/A (3) | 949 (AJ490805) | 23F | 81 (4,4,2,4,4,1,1) | 957 | 44 |

| ATCC 700669 (FM211187) | 23F | 81 | 957 | 9 | |

| Sp18-BS74 (NZ_ABAE01000010) | 6B | New (7,6,1,2,6,15,new) | 957 | 27 | |

| MLV-016 (NZ_ABGH01000008) | 11A | 62 (2,5,29,12,16,3,14) | 957 | Unpublished | |

| TCH8431/19A (NZ_ACJP01000181) | 19A | 320 (4,16,19,15,6,20,1) | 957 | Unpublished | |

| Taiwan19F-14 (CP000921) | 19F | 236 (15,16,19,15,6,20,26) | 957 | Unpublished | |

| PN8 (AJ2431413) | 23 | 906 | 54 | ||

| 7751 (AJ243414) | 6 | 906 | 54 | ||

| Canada MDR_19A (ACNU01000124) | 19A | 320 (4,16,19,15,6,20,1) | 957 | 46 | |

| Canada MDR_19F (ACNV01000155) | 19F | 320 | 957 | 46 | |

| 14_Spn/A (8) | 8249 (AJ490328) | 19A | 68 (2,8,9,5,12,1,13) | 957 | 44 |

| 15_Spn/Ae | S3 (FM865975) | 23F | 81 | 956 | Unpublished |

| 16_Spn/B (4) | ST344 (AM113493) | NT | 344 (8,37,9,29,2,12,53) | 957 | 5, 34 |

| 17_Spn/B (6) | ST942 (AM113494) | NT | 942 (8,10,15,27,2,28,4) | 957 | 5, 34 |

| 18_Spn/A (3) | OXC141d | 3 | 180 (7,15,2,10,6,1,22) | 957 | Unpublished |

| Sp3-BS71 (NZ_AAZZ01000010) | 3 | 180 | 957 | 27 | |

| 19_Spn/A (5) | CDC1087-00 (NZ_ABFT01000024) | 7F | 191 (8,9,2,1,6,1,17) | 957 | Unpublished |

| 219 (AF345846) | 7F | 940 | Unpublished | ||

| 20_Spn/A (2) | SP195 (NZ_ABGE01000012) | 9V | 156 (7,11,10,1,6,8,1) | 957 | Unpublished |

| INV200d | 14 | 9 (1,5,4,5,5,1,8) | 957 | Unpublished | |

| CGSP14 (CP001033) | 14 | 124 (7,5,1,8,14,11,14) | 957 | 13 | |

| SP9-BS68 (NZ_ABAB01000008) | 9V | 1269 (7,11,10,1,6,76,14) | 957 | 27 | |

| Sp19-BS75 (NZ_ABAF01000008) | 19F | 485 (1,5,1,1,1,1,8) | 957 | 27 | |

| Tupelo (FM865976) | 14 | 13 (1,5,4,5,5,27,8) | 957 | Unpublished | |

| 472 (AJ243410) | 3 | 906 | 54 | ||

| 860 (AJ243411) | NK | 906 | 54 | ||

| 29044 (AJ243412) | 14 | 906 | 54 | ||

| 21_Spn/A (7) | Sp11-BS70 (NZ_ABAC01000008) | 11D | 62 (2,5,29,12,16,3,14) | 957 | 27 |

| 22_Spn/B (2) | Sp14-BS69 (NZ_ABAD01000012) | 14 | 124 (7,5,1,8,14,11,14) | 957 | 27 |

| CCRI 1974 (NZ_ABZC01000110) | 14 | 124 | 957 | 19 | |

| 23_Spn/A (2) | Hungary19A-6 (CP000936) | 19A | 268 (7,13,42,6,10,6,56) | 957 | Unpublished |

| G54 (CP001015) | 19F | 63 (2,5,36,12,17,21,14) | 957 | 15 | |

| 24_Spn/B (2) | Sp23-BS72 (NZ_ABAG01000011) | 23F | 37 (1,8,6,2,6,4,6) | 957 | 27 |

| 25_Spn/A (3) | P1031 (CP000920) | 1 | 303 (10,5,4,1,7,19,9) | 957 | Unpublished |

| 26_Spn/B (2) | 70585 (CP000918) | 5 | 289 (16,12,9,1,41,33,33) | 957 | Unpublished |

| SMG | |||||

| 1_SMG | 101/87 (S43511) | NT | 951 | 12 | |

| 2_SMG | COL17 (AJ252190) | NT | 900 | 55 | |

| 3_SMG | COL16 (AJ252192) | NT | 900 | 55 | |

| 4_SMG | COL20 (AJ252194) | NT | 900 | 55 | |

| 5_SMG | CCUG 49455T (AM113495) | NT | 951 | 3, 34 | |

| CCUG 48465 (AM113496) | NT | 951 | 3, 34 | ||

| COL26 (AJ252195) | NT | 900 | 55 | ||

| 6_SMG | COL27 (AJ252196) | NT | 900 | 55 | |

| 7_SMG | 1508/92 (AJ419973) | NT | 951 | 43 | |

| 8_SMG | 11923/1992 (AJ419974) | NT | 951 | 43 | |

| 9_SMG | 8224/1994 (AJ419975) | NT | 951 | 43 | |

| 10_SMG | 10546/1994 (AJ419976) | 19 | 951 | 43 | |

| 11_SMG | 782/1996 (AJ419977) | NT | 951 | 43 | |

| 12_SMG | 1230/1996 (AJ419978) | 19 | 951 | 43 | |

| 13_SMG | 1283/1996 (AJ419979) | NT | 951 | 43 | |

| 14_SMG | 1338/1996 (AJ419980) | NT | 951 | 43 | |

| 15_SMG | 1078/1997 (AJ419981) | NT | 951 | 43 | |

| 16_SMG | 1383/1997 (AJ419982) | 19 | 951 | 43 | |

| 17_SMG | 1629/1997 (AJ419983) | 19 | 951 | 43 | |

| 18_SMG | 578 (AM113497) | NT | 951 | 34 | |

| 19_SMG | 1504 (AM113500) | NT | 951 | 34 | |

| 1956 (AM113501) | NT | 951 | 4 | ||

| 20_SMG | 3072 (AM113504) | NT | 951 | 34 | |

| 3198 (AM113505) | NT | 951 | 4 | ||

| 21_SMG | 3137 (AM113502) | NT | 951 | 4 | |

| 22_SMG | 2410 (AM113503) | NT | 951 | 4 | |

| 23_SMG | 1237 (AM113498) | NT | 951 | 4 | |

| 2859 (AM113499) | NT | 951 | 4 | ||

| Pneumococcal prophage (host strain) | |||||

| 1_PPH (NK)f | HB-3 (M34652) | 957 | 48 | ||

| 2_PPH (949) | MM1 (AJ302074) | 957 | 42 | ||

| (DCC1808) | MM1-1998 (DQ113772) | 957 | 35 | ||

| (ATCC 700669) | MM1-2008 (FM211187) | 957 | 49 | ||

| 3_PPH (8249) | VO1 (AJ490329) | 957 | 44 | ||

| 4_PPH (OXC141) | φSpn_OXCc | 957 | 49 | ||

| (SP3-BS71) | φSpn-3 (NZ_AAZZ01000017) | 957 | 49 | ||

| 5_PPH (Hungary19A-6) | φSpn_H_1 (CP000936) | 957 | 49 | ||

| 6_PPH (SP195) | φSpn_195_1 (NZ_ABGE01000002) | 957 | 49 | ||

| 7_PPH (SP195) | φSpn_195_2 (NZ_ABGE01000013) | 957 | 49 | ||

| 8_PPH (CDC1873-00) | φSpn_1873 (NZ_ABSF01000005) | 957 | 49 | ||

| (SVMC28) | SV1 (FJ765451) | 957 | 23 | ||

| 9_PPH (SP11-BS70) | φSpn_11 (NZ_ABAC01000001) | 957 | 49 | ||

| 10_PPH (CDC3059-06) | φSpn_3059 (NZ_ABGG01000014) | 957 | 49 | ||

| 11_PPH (SP19-BS75) | φSpn_19 (NZ_ABAF01000004) | 957 | 49 | ||

| 12_PPH (SP6-BS73) | φSpn_6 (NZ_ABAA01000020) | 957 | 49 | ||

| 13_PPH (SP23-BS72) | φSpn_23 (NZ_ABAG01000010) | 957 | 49 | ||

| 14_PPH (SP14-BS69) | φSpn_14 (NZ_ABAD01000023) | 957 | 49 | ||

| 15_PPH (670) | φSpn_670_1c | 957 | Unpublished | ||

| 16_PPH (670) | φSpn_670_2c | 957 | Unpublished | ||

| 17_PPH (JJA) | φSpn_JJA (CP000919) | 957 | Unpublished | ||

| 18_PPH (P1031) | φSpn_1031 (CP000920) | 957 | Unpublished | ||

| 19_PPH (70585) | φSpn_70585 (CP000918) | 957 | Unpublished | ||

| SMG prophage (host strain) | |||||

| 1_SPH (101) | EJ-1 (AJ609634) | 951 | 11 | ||

| 2_SPH (HER 1055) | φHER (AJ617815) | 957 | 51 | ||

| 3_SPH (B6) | φB6 (AJ617816) | 957 | 51 |

Nc, nonencapsulated; NT, nontypeable.

Indicates the number of nucleotides (nt) sequenced.

Preliminary sequence data (ftp://ftp.tigr.org/private/ufmg/s_pneumoniae_spuser_str670/s_pneumoniae-strain670).

Preliminary sequence data (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/S_pneumoniae).

This allele encodes a truncated protein.

NK, not known.

Identification of two families of lytA alleles in S. pneumoniae.

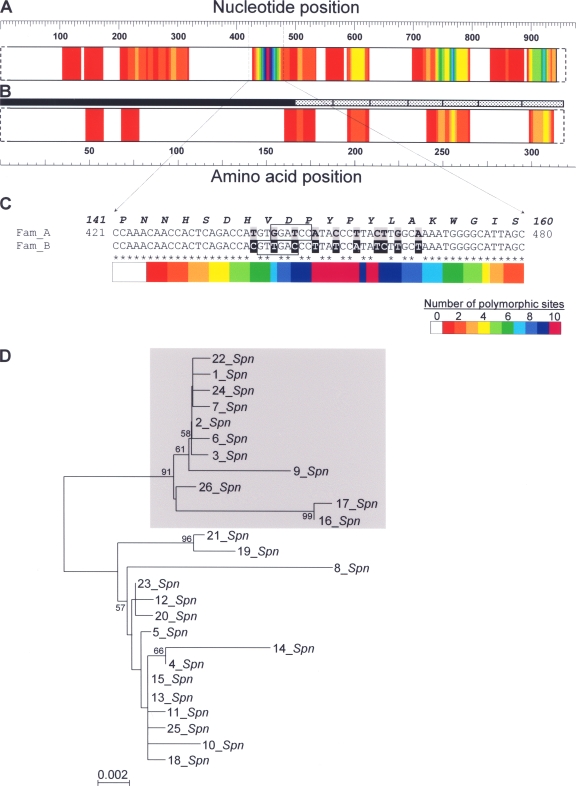

Figure 1 shows a diagram of lytASpn polymorphism. When full-length lytASpn (or LytASpn) sequences were compared (17 alleles), they differed at only 44 nucleotide and 13 amino acid positions. Although two peaks around nucleotide positions 767 and 923 were detected, the most remarkably polymorphic region occurs near the middle of the gene (around position 453). Thus, polymorphism between nucleotide positions 421 and 480 accounts for an estimated PED of 18.9%, which contrasts greatly with a PED value of less than 3.5% characteristic of the full lytASpn allele length (data not shown). Notably, nucleotide polymorphism is not mirrored in the primary structure of the protein, in which perfect amino acid sequence conservation was observed (Fig. 1B). Upon closer examination of the nucleotide sequence of this polymorphic region, we observed that the 26 different lytASpn alleles examined here could be divided into two families (here designated Fam_A and Fam_B) depending on their precise sequence (Fig. 1C). Hence, Fam_A and Fam_B lytA alleles, respectively, include a BamHI or HincII restriction sequence. This feature can be used for rapid discrimination between the two types of alleles (unpublished observations). Fam_B lytA alleles form an independent and consistent clade (Fig. 1D).

FIG. 1.

Polymorphic sites of lytASpn and the LytASpn NAM-amidase alleles. (A and B) Only full-length (957-bp) lytASpn alleles (17 alleles) and the corresponding 318-amino-acid-long LytASpn NAM-amidases were aligned using Clustal W 2. Polymorphism within a window of 31 nucleotides (or 11 amino acid residues), while advancing through the sequence, was calculated from a multiple sequence alignment. Overlapping windows were displaced from each other by one nucleotide (or residue). The sum of polymorphic positions found was plotted at the middle position of the window. The blackened bar or the stippled boxes, respectively, represent the N-terminal domain or the C-terminal repeats of NAM-amidase. (C) Nucleotide sequence around position 453 (taking as position 1 the first nucleotide of the ATG initiation codon) that identifies two different lytASpn families. The deduced amino acid sequence and its corresponding positions are boldfaced and italicized. Asterisks indicate nucleotides conserved in all lytASpn alleles described in Table 1. Nucleotides distinctive of each family of lytASpn alleles are highlighted on a gray (Fam_A) or black (Fam_B) background. The BamHI and HincII restriction sites characteristic of Fam_A and Fam_B lytA alleles, respectively, are boxed. (D) Phylogenetic tree of the S. pneumoniae lytA alleles. The neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree (phylogram) shows evolutionary relationships among lytA alleles. Sequences were trimmed so that the length of the alignment was adjusted to 906 nucleotides. The statistical significance of the tree branches was assessed by bootstrap analysis involving the construction of 1,000 trees from resampled data. Bootstrap values of >50% are indicated. The gray box indicates the positions of Fam_B lytA alleles. The scale bar represents the number of nucleotide substitutions per site.

Distribution of polymorphic sites in nonpneumococcal lytA genes.

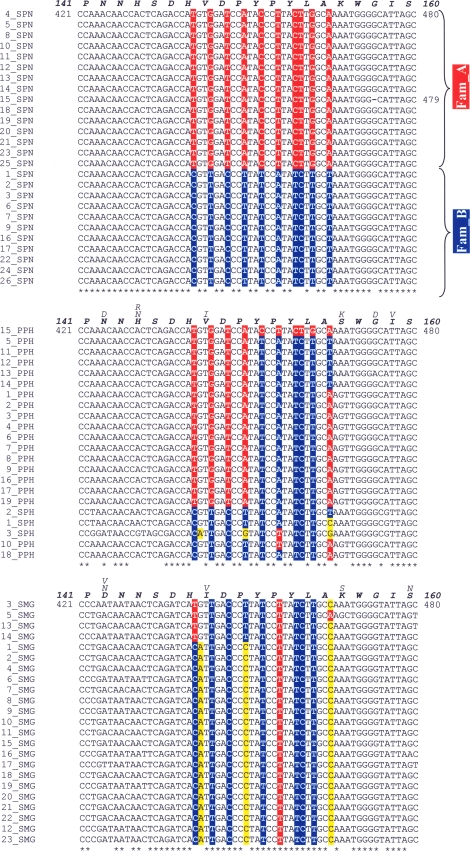

To determine the possible evolutionary origin of the lytASpn families, complete lytA alleles from SMG or pneumococcal prophages were aligned and polymorphic site distributions were compared to that of lytASpn. Figure 2 shows that the lytA alleles from SMG or temperate phages are much more polymorphic than those from S. pneumoniae, the variable sites appearing along the whole gene (or protein), in contrast to that noted in the lytASpn alleles. The lytASMG alleles differed at 138 positions (35 amino acid residues), whereas 158 polymorphic nucleotide positions (31 amino acid residues) were detected in the lytAPPH alignments. Since phage genes evolve faster than their bacterial counterparts (reviewed in references 1 and 2), it was not surprising to find that the phage alleles were so diverse. In contrast, the reduced polymorphism observed for the lytASpn alleles relative to that exhibited by lytASMG alleles suggests that the former alleles were acquired fairly recently in evolutionary terms and/or that S. pneumoniae strains are a much more closely related group than SMG, as recently demonstrated (7, 14, 26). Further, in a multiple alignment of the 71 lytA alleles examined here around nucleotide position 453, it was noted that only two phage alleles, lytA15_PPH (φSpn_670_1) and lytA2_SPH (φHER), have sequences identical to those characteristic of Fam_A and Fam_B lytA alleles, respectively (Fig. 3). Quite unexpectedly, signatures identical to either lytA family were absent among the lytASMG alleles.

FIG. 2.

Distributions of polymorphic sites in bacterial and phage lytA alleles and their encoded NAM-amidases. Only full-length lytA alleles were analyzed. Polymorphic sites were calculated as indicated in Fig. 1. Nucleotide (nt) and amino acid (aa) positions appear as black or red symbols, respectively. (A) Pneumococcal temperate phages. (B) S. pneumoniae alleles. (C) Streptococci of the mitis group (SMG). A hatched bar indicates the position of the 6-nucleotide deletion distinctive of lytASMG alleles.

FIG. 3.

Multiple alignments of pneumococcal, phage, and SMG lytA alleles. Nucleotides distinctive of the Fam_A and Fam_B lytA alleles are shown on a red or on a blue background, respectively. Other polymorphic nucleotides are shown on a yellow background. Asterisks indicate nucleotides identical in all the sequences. The hyphen corresponds to a 1-bp deletion. Nucleotide (and amino acid) positions (taking 1 as the first nucleotide of the ATG initiation codon or the first residue) are shown. Amino acid polymorphisms are indicated.

Prophage-host recombination in the lytA gene.

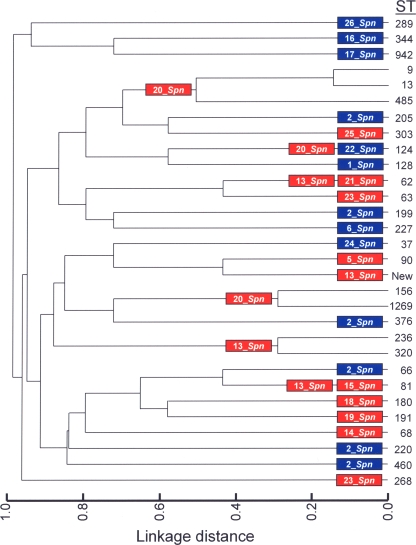

Recent recombinational events are apparent by visual inspection of sequence alignments, particularly if the replacements are short enough that breakpoints can be defined within the sequenced region (17), as is the case for the mosaicism in the genes of S. pneumoniae coding for the penicillin-binding proteins (16), rpoB genes of rifampin-resistant strains (21), or DNA topoisomerase genes of fluoroquinolone-resistant isolates (22). Descendants from a particular clone that differ at one of the seven loci defined by multilocus sequence typing (MLST) are named single locus variants (SLVs). Variant alleles in SLVs are therefore assigned as having arisen by a point mutation if they differ from the ancestral allele at a single nucleotide site. Variant alleles that differ at multiple sites (plus those that differ at a single site but are present in an unrelated lineage) are assigned as having arisen by recombination (for a review, see reference 17). Following this criterion, evidence strongly suggesting the existence of recombination events in the lytA gene between host and prophages was found, particularly in the case of serotype 14 strains CGSP14 and SP14-BS69, which belong to ST124. Whereas strain CGSP14 harbors a Fam_A allele (lytA20_Spn), SP14-BS69 possesses a Fam_B allele (lytA222_Spn) (Table 1 and Fig. 4). A nucleotide alignment (not shown) illustrated that the two alleles differ at 13 positions, 10 of them located between positions 441 and 465 (i.e., the signature characteristic of Fam_A/Fam_B lytA alleles), and only 3 more changes elsewhere in the lytA gene (at positions 264, 282, and 567). Moreover, the data presented in Fig. 4 indicate that recombination events between bacteria and phage lytA genes have occurred more than once, because the same alleles are present in isolates that are not closely related. For example, lytA20_Spn (Fam_A) appears in strains of ST9, ST13, ST485, ST156, and ST1269, whereas lytA2_Spn (Fam_B) is present in isolates of ST66, ST199, ST205, ST220, ST376, and ST460.

FIG. 4.

Dendrogram of genetic relationships among 109 strains belonging to 30 different STs based on multilocus sequence typing data (http://www.mlst.net/). Linkage distance is indicated by a scale at the bottom. The lytASpn allele present in pneumococcal strains of each ST is shown. Fam_A and Fam_B alleles are shown on a red or on a blue background, respectively.

Out of all the lytASpn alleles whose complete sequence is known, the lytA gene of prophage φSpn_670_1 shows the greatest similarity (92% identity; PED, 7.10%) with the lytA gene (lytA5_Spn) of its host strain, i.e., strain 670, a member of the globally distributed, antibiotic-resistant clone Spain6B-2. In effect, bacterial and phage lytA genes were identical from positions 343 to 495 and from 497 to the gene end (data not shown). In contrast, only 85% identity (817 out of 957 nucleotides) (PED, 16.33%) was seen when alleles lytA5_Spn (from strain 670) and lytA16_PPH (from φSpn_670_2, the second prophage harbored by strain 670) were aligned (not shown). Besides, the lytA gene of the S. mitis prophage φHER (lytA2_SPH) showed the highest similarity (82% identity; PED, 20.12%) with the NAM-amidase gene (lytA16_Spn) of the nontypeable pneumococcal isolate ST344. Although the implication of this finding is unclear, it suggests that temperate phages from SMG play a role in dissemination of the pneumococcal lytA gene among alpha-hemolytic streptococci sharing the same habitat (50).

Genetic transformation is envisaged as the main mechanism of horizontal gene transfer among SMG, whereas the contribution of phages, either lytic or temperate, to the dissemination of clinically relevant genes had not been so well established. Almost 20 years ago, Romero et al. provided direct evidence of recombination between the lytA gene of a pneumococcal prophage and that of the host under laboratory conditions (48). These authors observed remarkable nucleotide similarity (87%) between the lytA gene and the hbl gene. The hbl gene, encoding the NAM-amidase of the temperate phage HB-3 (designated allele 1_PPH in Table 1), transformed NAM-amidase-deficient strains of S. pneumoniae into the wild-type phenotype. In 1999, the possibility of in vivo localized recombination events between phage and bacterial lytA genes was proposed (54). Nevertheless, since only a reduced number of lytASpn alleles and only one temperate S. pneumoniae phage (HB-3) and another S. mitis prophage (EJ-1; allele 1_SPH) were known at that time, only a preliminary conclusion could be reached. Our data confirm and extend these past findings and strongly suggest that phage genes could play a significant role in the evolution of bacterial genes involved in disease processes, as is the case for LytA NAM-amidase. The remarkable similarity between the lytA genes either from bacteria or from phages, as well as their capacity to recombine, allows us to properly use the term “homologous.” This homology makes it likely that the phage-encoded NAM-amidase derived directly from the corresponding S. pneumoniae gene, although we cannot exclude the possibility that the host genes are descended from related phage genes, as previously suggested (8).

Acknowledgments

We thank R. López and V. Rodríguez-Cerrato for helpful comments and critical reading of the manuscript, A. Burton for revising the English version of the manuscript, and E. Cano and B. Piñeiro for skillful technical assistance.

This work was supported by grants from the Dirección General de Investigación Científica y Técnica (SAF2006-00390 and BIO2008-02189). CIBER de Enfermedades Respiratorias (CIBERES) is an initiative of ISCIII.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 19 March 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abedon, S. T. 2009. Phage evolution and ecology. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 67:1-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abedon, S. T., and J. T. LeJeune. 2005. Why bacteriophage encode exotoxins and other virulence factors. Evol. Bioinform. 1:97-110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arbique, J. C., C. Poyart, P. Trieu-Cuot, G. Quesne, M. D. S. Carvalho, A. G. Steigerwalt, R. E. Morey, D. Jackson, R. J. Davidson, and R. R. Facklam. 2004. Accuracy of phenotypic and genotypic testing for identification of Streptococcus pneumoniae and description of Streptococcus pseudopneumoniae sp. nov. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:4686-4696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balsalobre, L., A. Hernández-Madrid, D. Llull, A. J. Martín-Galiano, E. García, A. Fenoll, and A. G. de la Campa. 2006. Molecular characterization of disease-associated streptococci of the mitis group that are optochin susceptible. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:4163-4171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berrón, S., A. Fenoll, M. Ortega, N. Arellano, and J. Casal. 2005. Analysis of the genetic structure of nontypeable pneumococcal strains isolated from conjunctiva. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:1694-1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berry, A. M., and J. C. Paton. 2000. Additive attenuation of virulence of Streptococcus pneumoniae by mutation of the genes encoding pneumolysin and other putative pneumococcal virulence proteins. Infect. Immun. 68:133-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bishop, C. J., D. M. Aanensen, G. E. Jordan, M. Kilian, W. P. Hanage, and B. G. Spratt. 2009. Assigning strains to bacterial species via the internet. BMC Biol. 7:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell, A. 1988. Phage evolution and speciation, p. 1-14. In R. Calendar (ed.), The bacteriophages, vol. 1. Plenum Publishing Corp., New York, NY.

- 9.Croucher, N. J., D. Walker, P. Romero, N. Lennard, G. K. Paterson, N. C. Bason, A. M. Mitchell, M. A. Quail, P. W. Andrew, J. Parkhill, S. D. Bentley, and T. J. Mitchell. 2009. Role of conjugative elements in the evolution of the multidrug-resistant pandemic clone Streptococcus pneumoniaeSpain23F ST81. J. Bacteriol. 191:1480-1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devereux, J., P. Haeberli, and O. Smithies. 1984. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 12:387-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Díaz, E., R. López, and J. L. García. 1992. EJ-1, a temperate bacteriophage of Streptococcus pneumoniae with a Myoviridae morphotype. J. Bacteriol. 174:5516-5525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Díaz, E., R. López, and J. L. García. 1992. Role of the major pneumococcal autolysin in the atypical response of a clinical isolate of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 174:5508-5515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ding, F., P. Tang, M.-H. Hsu, P. Cui, S. Hu, J. Yu, and C.-H. Chiu. 2009. Genome evolution driven by host adaptations results in a more virulent and antimicrobial-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 14. BMC Genomics 10:158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Do, T., K. A. Jolley, M. C. J. Maiden, S. C. Gilbert, D. Clark, W. G. Wade, and D. Beighton. 2009. Population structure of Streptococcus oralis. Microbiology 155:2593-2602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dopazo, J., A. Mendoza, J. Herrero, F. Caldara, Y. Humbert, L. Friedli, M. Guerrier, E. Grand-Schenk, C. Gandin, M. de Francesco, A. Polissi, G. Buell, G. Feger, E. García, M. Peitsch, and J. F. García-Bustos. 2001. Annotated draft genomic sequence from a Streptococcus pneumoniae type 19F clinical isolate. Microb. Drug Resist. 7:99-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dowson, C. G., A. Hutchison, N. Woodford, A. P. Johnson, R. C. George, and B. G. Spratt. 1990. Penicillin-resistant viridans streptococci have obtained altered penicillin-binding protein genes from penicillin-resistant strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 87:5858-5862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feil, E. J. 2004. Small change: keeping pace with microevolution. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2:483-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feil, E. J., and B. G. Spratt. 2001. Recombination and the population structures of bacterial pathogens. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 55:561-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feng, J., A. Lupien, H. Gingras, J. Wasserscheid, K. Dewar, D. Légaré, and M. Ouellette. 2009. Genome sequencing of linezolid-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae mutants reveals novel mechanisms of resistance. Genome Res. 19:1214-1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fenoll, A., J. V. Martínez-Suárez, R. Muñoz, J. Casal, and J. L. García. 1990. Identification of atypical strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae by a specific DNA probe. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 9:396-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferrándiz, M. J., C. Ardanuy, J. Liñares, J. M. García-Arenzana, E. Cercenado, A. Fleites, A. G. de la Campa, and the Spanish Pneumococcal Infection Study Network. 2005. New mutations and horizontal transfer of rpoB among rifampin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae from four Spanish hospitals. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:2237-2245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferrándiz, M. J., A. Fenoll, J. Liñares, and A. G. de la Campa. 2000. Horizontal transfer of parC and gyrA in fluoroquinolone-resistant clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:840-847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frias, M. J., J. Melo-Cristino, and M. Ramirez. 2009. The autolysin LytA contributes to efficient bacteriophage progeny release in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 191:5428-5440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.García, P., J. L. García, E. García, and R. López. 1986. Nucleotide sequence and expression of the pneumococcal autolysin gene from its own promoter in Escherichia coli. Gene 43:265-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.García, P., J. L. García, R. López, and E. García. 2005. Pneumococcal phages, p. 335-361. In M. K. Waldor, D. L. I. Friedman, and S. Adhya (ed.), Phages: their role in bacterial pathogenesis and biotechnology. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 26.Hanage, W. P., C. Fraser, J. Tang, T. R. Connor, and J. Corander. 2009. Hyper-recombination, diversity, and antibiotic resistance in pneumococcus. Science 324:1454-1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hiller, N. L., B. Janto, J. S. Hogg, R. Boissy, S. Yu, E. Powell, R. Keefe, N. E. Ehrlich, K. Shen, J. Hayes, K. Barbadora, W. Klimke, D. Dernovoy, T. Tatusova, J. Parkhill, S. D. Bentley, J. C. Post, G. D. Ehrlich, and F. Z. Hu. 2007. Comparative genomic analyses of seventeen Streptococcus pneumoniae strains: insights into the pneumococcal supragenome. J. Bacteriol. 189:8186-8195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hirst, R., B. Gosai, A. Rutman, C. Guerin, P. Nicotera, P. Andrew, and C. O'Callaghan. 2008. Streptococcus pneumoniae deficient in pneumolysin or autolysin has reduced virulence in meningitis. J. Infect. Dis. 197:744-751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoskins, J., W. E. Alborn, Jr., J. Arnold, L. C. Blaszczak, S. Burgett, B. S. DeHoff, S. T. Estrem, L. Fritz, D.-J. Fu, W. Fuller, C. Geringer, R. Gilmour, J. S. Glass, H. Khoje, A. R. Kraft, R. E. Lagace, D. J. LeBlanc, L. N. Lee, E. J. Lefkowitz, J. Lu, P. Matsushima, S. M. McAhren, M. McHenney, K. McLeaster, C. W. Mundy, T. I. Nicas, F. H. Norris, M. O'Gara, R. B. Peery, G. T. Robertson, P. Rockey, P.-M. Sun, M. E. Winkler, Y. Yang, M. Young-Bellido, G. Zhao, C. A. Zook, R. H. Baltz, R. Jaskunas, P. R. J. Rosteck, P. L. Skatrud, and J. I. Glass. 2001. Genome of the bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae strain R6. J. Bacteriol. 183:5709-5717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Howard, L. V., and H. Gooder. 1974. Specificity of the autolysin of Streptococcus (Diplococcus) pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 117:796-804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jedrzejas, M. J. 2001. Pneumococcal virulence factors: structure and function. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 65:187-207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lanie, J. A., W. L. Ng, K. M. Kazmierczak, T. M. Andrzejewski, T. M. Davidsen, K. J. Wayne, H. Tettelin, J. I. Glass, and M. E. Winkler. 2007. Genome sequence of Avery's virulent serotype 2 strain D39 of Streptococcus pneumoniae and comparison with that of unencapsulated laboratory strain R6. J. Bacteriol. 189:38-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Larkin, M. A., G. Blackshields, N. P. Brown, R. Chenna, P. A. McGettigan, H. McWilliam, F. Valentin, I. M. Wallace, A. Wilm, R. Lopez, J. D. Thompson, T. J. Gibson, and D. G. Higgins. 2007. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23:2947-2948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Llull, D., R. López, and E. García. 2006. Characteristic signatures of the lytA gene provide a rapid and reliable diagnosis of Streptococcus pneumoniae infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:1250-1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loeffler, J. M., and V. A. Fischetti. 2006. Lysogeny of Streptococcus pneumoniae with MM1 phage: improved adherence and other phenotypic changes. Infect. Immun. 74:4486-4495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.López, R., and E. García. 2004. Recent trends on the molecular biology of pneumococcal capsules, lytic enzymes, and bacteriophage. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 28:553-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.López, R., E. García, P. García, and J. L. García. 2004. Cell wall hydrolases, p. 75-88. In E. I. Tuomanen, T. J. Mitchell, D. A. Morrison, and B. G. Spratt (ed.), The pneumococcus. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 38.Lund, E., and J. Henrichsen. 1978. Laboratory diagnosis, serology and epidemiology of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Methods Microbiol. 12:241-262. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mortier-Barrière, I., A. de Saizieu, J. P. Claverys, and B. Martin. 1998. Competence-specific induction of recA is required for full recombination proficiency during transformation in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 27:159-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neufeld, F. 1900. Üeber eine specifische bakteriolystische wirkung der galle. Z. Hyg. Infektionskr. 34:454-464. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ng, E. W., J. R. Costa, N. Samiy, K. L. Ruoff, E. Connolly, F. V. Cousins, and D. J. D'Amico. 2002. Contribution of pneumolysin and autolysin to the pathogenesis of experimental pneumococcal endophthalmitis. Retina 22:622-632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Obregón, V., J. L. García, E. García, R. López, and P. García. 2003. Genome organization and molecular analysis of the temperate bacteriophage MM1 of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 185:2362-2368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Obregón, V., P. García, E. García, A. Fenoll, R. López, and J. L. García. 2002. Molecular peculiarities of the lytA gene isolated from clinical pneumococcal strains that are bile-insoluble. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2545-2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Obregón, V., P. García, R. López, and J. L. García. 2003. VO1, a temperate bacteriophage of the type 19A multiresistant epidemic 8249 strain of Streptococcus pneumoniae: analysis of variability of lytic and putative C5 methyltransferase genes. Microb. Drug Resist. 9:7-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Orihuela, C. J., G. Gao, K. P. Francis, J. Yu, and E. I. Tuomanen. 2004. Tissue-specific contributions of pneumococcal virulence factors to pathogenesis. J. Infect. Dis. 190:1661-1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pillai, D., D. Shahinas, A. Buzina, R. Pollock, R. Lau, K. Khairnar, A. Wong, D. Farrell, K. Green, A. McGeer, and D. Low. 2009. Genome-wide dissection of globally emergent multi-drug resistant serotype 19A Streptococcus pneumoniae. BMC Genomics 10:642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramirez, M., E. Severina, and A. Tomasz. 1999. A high incidence of prophage carriage among natural isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 181:3618-3625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Romero, A., R. López, and P. García. 1990. Sequence of the Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteriophage HB-3 amidase reveals high homology with the major host autolysin. J. Bacteriol. 172:5064-5070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Romero, P., N. J. Croucher, N. L. Hiller, F. Z. Hu, G. D. Ehrlich, S. D. Bentley, E. García, and T. J. Mitchell. 2009. Comparative genomic analysis of ten Streptococcus pneumoniae temperate bacteriophages. J. Bacteriol. 191:4854-4862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Romero, P., E. García, and T. J. Mitchell. 2009. Development of a prophage typing system and analysis of prophage carriage in Streptococcus pneumoniae Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:1642-1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Romero, P., R. López, and E. García. 2004. Characterization of LytA-like N-acetylmuramoyl-L-alanine amidases from two new Streptococcus mitis bacteriophages provides insights into the properties of the major pneumococcal autolysin. J. Bacteriol. 186:8229-8239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tamura, K., J. Dudley, M. Nei, and S. Kumar. 2007. MEGA4: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24:1596-1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tettelin, H., K. E. Nelson, I. T. Paulsen, J. A. Eisen, T. D. Read, S. Peterson, J. Heidelber, R. T. DeBoy, D. H. Haft, R. J. Dodson, A. S. Durkin, M. Gwinn, J. F. Kolonay, W. C. Nelson, J. D. Peterson, L. A. Umayam, O. White, S. L. Salzberg, M. R. Lewis, D. Radune, E. Holtzapple, H. Khouri, A. M. Wolf, T. R. Utterback, C. L. Hansen, L. A. McDonald, T. V. Feldblyum, S. Angiuoli, T. Dickinson, E. K. Hickey, I. E. Holt, B. J. Loftus, F. Yang, H. O. Smith, J. C. Venter, B. A. Dougherty, D. A. Morrison, S. K. Hollingshead, and C. M. Fraser. 2001. Complete genome sequence of a virulent isolate of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Science 293:498-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Whatmore, A. M., and C. G. Dowson. 1999. The autolysin-encoding gene (lytA) of Streptococcus pneumoniae displays restricted allelic variation despite localized recombination events with genes of pneumococcal bacteriophage encoding cell wall lytic enzymes. Infect. Immun. 67:4551-4556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Whatmore, A. M., A. Efstratiou, A. P. Pickerill, K. Broughton, G. Woodard, D. Sturgeon, R. George, and C. G. Dowson. 2000. Genetic relationships between clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus oralis, and Streptococcus mitis: characterization of “atypical” pneumococci and organisms allied to S. mitis harboring S. pneumoniae virulence factor-encoding genes. Infect. Immun. 68:1374-1382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]