Abstract

Candida albicans can form biofilms that exhibit elevated intrinsic resistance to various antifungal agents, in particular azoles and polyenes. The molecular mechanisms involved in the antifungal resistance of biofilms remain poorly understood. We have used transcript profiling to explore the early transcriptional responses of mature C. albicans biofilms exposed to various antifungal agents. Mature C. albicans biofilms grown under continuous flow were exposed for as long as 2 h to concentrations of fluconazole (FLU), amphotericin B (AMB), and caspofungin (CAS) that, while lethal for planktonic cells, were not lethal for biofilms. Interestingly, FLU-exposed biofilms showed no significant changes in gene expression over the course of the experiment. In AMB-exposed biofilms, 2.7% of the genes showed altered expression, while in CAS-exposed biofilms, 13.0% of the genes had their expression modified. In particular, exposure to CAS resulted in the upregulation of hypha-specific genes known to play a role in biofilm formation, such as ALS3 and HWP1. There was little overlap between AMB- or CAS-responsive genes in biofilms and those that have been identified as AMB, FLU, or CAS responsive in C. albicans planktonic cultures. These results suggested that the resistance of C. albicans biofilms to azoles or polyenes was due not to the activation of specific mechanisms in response to exposure to these antifungals but rather to the intrinsic properties of the mature biofilms. In this regard, our study led us to observe that AMB physically bound C. albicans biofilms and beta-glucans, which have been proposed to be major constituents of the biofilm extracellular matrix and to prevent azoles from reaching biofilm cells. Thus, enhanced extracellular matrix or beta-glucan synthesis during biofilm growth might prevent antifungals, such as azoles and polyenes, from reaching biofilm cells, thus limiting their toxicity to these cells and the associated transcriptional responses.

Candida albicans is a polymorphic fungus that exists either as a commensal of the gastrointestinal and genitourinary tracts or as an opportunistic pathogen. It is responsible for mucosal infections in immunocompetent individuals, as well as for life-threatening systemic infections in patients treated in intensive care units (ICUs), cancer patients receiving chemotherapy, and organ transplant patients (37, 40, 58, 74-76). C. albicans is currently regarded as the fourth and third leading causes of hospital-acquired bloodstream and urinary tract infections, respectively (34, 54).

Microbial biofilms are communities of microbial cells that grow on biotic or abiotic surfaces and display specific phenotypic traits, such as high resistance to drugs to which their planktonic counterparts remain susceptible. Biofilm formation by C. albicans is a well-recognized phenomenon. A C. albicans biofilm is a heterogeneous community of yeast, pseudohyphal, and hyphal cells embedded in an extracellular polymeric matrix, noticeably including soluble beta-glucans (11, 17, 18, 47, 49). The formation of biofilms is intimately associated with C. albicans pathogenesis. This is the case in superficial infections, where C. albicans colonizes several tissues, such as vaginal and oral epithelia, or inert surfaces, such as dental prostheses (34, 60). Patients at risk of developing disseminated candidiasis often have implants—such as implantable ports, or intravascular or urinary catheters—and these constitute potential substrates for the formation of Candida biofilms. In particular, it has been shown that the presence of a central venous catheter is a risk factor for the establishment and persistence of nosocomial C. albicans infections (21, 64). Antifungal treatment without implant removal is rarely successful, leading to relapse in a significant number of cases. Consequently, catheter withdrawal is considered a prerequisite to successful antifungal treatment (42). These observations provide indirect evidence that C. albicans biofilms formed under clinical conditions display intrinsic resistance to antifungals. Consistent with these observations, a number of studies show that C. albicans biofilms obtained in vitro display decreased sensitivity to almost all available antifungals: amphotericin B (AMB), flucytosine, terbinafine, nystatin, and, most notably, azoles (6, 13, 14, 28, 35, 61-63). Fifty percent inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) are increased as much as 10-fold, while MICs are increased 30- to 20,000-fold; the highest level of resistance observed is that to azoles (16, 17, 36). However, C. albicans biofilms remain susceptible to treatments with echinocandins and some lipid formulations of AMB (5, 35, 63). In particular, it has been shown that caspofungin (CAS) application to C. albicans biofilms results in an almost complete loss of metabolic activity, even at concentrations in the range of those used in a clinical setting (63).

Several hypotheses have been formulated to explain the decreased sensitivity of C. albicans biofilms to antifungal agents: (i) a reduced metabolic state or specific physiology of biofilm cells, (ii) restricted drug penetration through the biofilm matrix, and (iii) expression of genes specific to biofilm cells that contribute to antifungal resistance (13). A reduced growth rate of C. albicans biofilms is unlikely to account for antifungal resistance, since it has been shown that changes in growth rates do not influence the sensitivity of biofilms to antifungals, and a majority of biofilm cells are metabolically active, with elevated transcription of genes associated with ribosome biogenesis (7, 24). In contrast, changes in the physiology of biofilms might contribute to resistance to azoles and AMB. Indeed, decreased levels of ergosterol, whose biosynthesis is inhibited by azoles and which is bound by AMB, and diminished expression of ergosterol biosynthetic genes have been reported in mature C. albicans biofilms (24, 46). It has also been proposed that resistance to antifungals might result from the occurrence of biofilm-specific persister cells highly tolerant to antifungals, even though such persister cells do not always occur in C. albicans biofilms (1, 38).

A role of the biofilm extracellular matrix (ECM) in antifungal resistance has recently gained credit, even though the chemistry of the ECM of C. albicans biofilms remains to be fully elucidated. Indeed, while it is known that varying the levels of ECM does not influence antifungal sensitivity (8) and that antifungals such as fluconazole (FLU) and 5-flucytosine permeate biofilms efficiently and reach concentrations far above MICs (3, 67), it has been shown that FLU binds to β-1,3-glucans, a structural component of the fungal cell wall as well as of the biofilm ECM, and that altering β-1,3-glucans increases the sensitivity of biofilms to FLU and AMB (49). A current model is that antifungals such as FLU, and possibly AMB, might bind β-1,3-glucans in the ECM, thus accumulating to high concentrations in the biofilm and yet not reaching their target.

Exposure of C. albicans planktonic cells to azole antifungals is associated with the upregulation of genes that encode components of the ergosterol biosynthetic pathway and drug efflux pumps, thus providing a transient resistance mechanism (68). Genes encoding drug efflux pumps, namely, MDR1, CDR1, and CDR2, are upregulated upon attachment of C. albicans cells to a surface, and this probably accounts for the resistance of early-stage biofilms to azole drugs (13, 46, 59). However, deletion of these three genes, either singly or in combination, does not affect the high level of drug resistance of mature biofilms, indicating that they do not play a major role in this phenomenon (46, 59).

Like that of planktonic cells, the resistance of C. albicans biofilm cells to antifungals might result from changes in gene expression in response to antifungal exposure. In the present study we have used transcript profiling to investigate the early transcriptional responses of mature biofilms exposed to various antifungal agents at concentrations that are relatively ineffective on biofilms but effective on planktonic cells. Interestingly, our results showed that the extents of the transcriptional responses of mature biofilms to FLU, AMB, and CAS were well correlated with the efficacies of these antifungals against biofilms. Moreover, we showed that AMB, like FLU (49), bound to biofilms and β-1,3-glucans. Taken together, these data suggested that the resistance of C. albicans biofilms to antifungals resulted in part from the binding to ECM components of antifungal molecules, which then could not effectively trigger cellular responses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

C. albicans strains and growth conditions.

C. albicans strain SC5314, an isolate from a patient with systemic candidiasis (25), was used for the production of biofilms and transcriptome analysis. Strain CEC161 (ura3::λimm434/ura3::λimm434 ARG4/arg4::hisG HIS1/his1::hisG) (22) was used to transform gLUC59 reporter constructs (see below). These strains were routinely grown in flasks at 30°C in YPD (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% glucose). When necessary, YNB (0.67% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids; Difco) medium with 0.4% glucose, supplemented with histidine (20 mg/liter), arginine (20 mg/liter), and uridine (40 mg/liter), was used. Biofilms of wild-type C. albicans strain SC5314 were formed on plastic slides (Thermanox; Nunc) using microfermentors as previously described (24). Thermanox slides were immersed in cell suspensions for 30 min to allow cell adhesion. The slides were then transferred to microfermentors and were incubated for 30 h at 37°C with a continuous flow of YNB medium supplemented with 0.4% glucose, arginine (0.1 g/liter), methionine (0.2 g/liter), and histidine (0.1 g/liter), and with air bubbling. Under these conditions, growth of planktonic cells was minimized. After 30 h of growth, sets of biofilms in microfermentors were exposed to antifungal agents at the following selected concentrations: amphotericin B (AMB), 8 μg/ml; fluconazole (FLU), 80 μg/ml; caspofungin (CAS), 5 and 0.5 μg/ml. A calculated volume of the antifungal stock solution was directly added to the microfermentor in order to bring the culture to the desired antifungal concentration. The flow of supplemented YNB medium was then replaced by a flow of supplemented YNB medium containing the antifungal at the desired concentration, and growth was continued for 2 h at 37°C. Control biofilms were exposed to similar volumes of the solvents used to prepare the antifungal stock solutions, namely, 100% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) for AMB and water for FLU or CAS. At 0, 30, 60, and 120 min post-antifungal exposure, control and antifungal-exposed biofilms were recovered and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. These experiments were performed in duplicate or triplicate, except for that with 0.5 μg/ml CAS, which was performed only once for each time point.

Metabolic activity and vital staining.

The metabolic activity of biofilms was quantified using the fluorescein diacetate (FDA) hydrolytic activity method as described by Honraet et al. (30) and Peeters et al. (56). This assay involves the conversion of colorless, nonfluorescent FDA into yellow, highly fluorescent fluorescein by nonspecific intra- and extracellular esterases of viable cells in a given time interval and has been shown to provide an accurate measurement of planktonic and biofilm yeast biomass (30). FUN-1 viability staining was performed as described in reference 29.

Transcript profiling.

Total RNA was isolated using the Qiagen RNeasy kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA samples (5 μg) were indirectly labeled using an Atlas PowerScript fluorescent labeling kit (Clontech) or the SuperScript indirect cDNA labeling system (Invitrogen) with 1 μg oligo(dT) (Invitrogen), according to the conditions recommended by the manufacturers. cDNAs were coupled with cyanines using Cy3 monoreactive dye or Cy5 monoreactive dye (GE Healthcare). Fluorescent cDNAs were then purified with the Fluortrap matrix (Clontech) or S.N.A.P columns (Invitrogen). Equal quantities of the Cy3 and Cy5 targets were mixed and concentrated by a Microcon YM-30 filter unit (Millipore). Probes were hybridized to C. albicans microarrays (Array Express accession number A-MEXP-1725; Eurogentec, Seraing, Belgium) according to the conditions recommended by the manufacturer. Arrays were scanned with an Axon 4000a scanner. Data were acquired and analyzed by Genepix Pro, version 5.0 (Axon Instruments). Data normalization (Lowess) and analysis were performed using GeneSpring (Silicon Genetics, Redwood City, CA). Statistical significance for differential expression of genes by control and antifungal-exposed biofilms at 0, 30, 60, and 120 min was determined using the t test (with the Benjamini-Hochberg correction). For all time points, RNAs obtained from AMB-, FLU- and CAS-exposed and control biofilms were compared using a dye swap and biological duplicates or triplicates, except for 0.5 μg/ml CAS, for which there was only one biological replicate. Genes with 1.5-fold upregulation or downregulation and a P value of <0.05 were considered significantly regulated, except for 0.5 μg/ml CAS, where 2-fold up- or downregulation and a P value of <0.05 were used.

Validation of transcript profiling data.

The impact of exposure to caspofungin on the expression of genes identified by transcript profiling was evaluated using strains with fusions to the gLUC59 reporter (20). Briefly, regions encompassing 2 kb upstream of the start codon of the ALS3 or HWP1 gene were amplified using oligonucleotides HWP1_XhoI_5′ (5′-CGGCTCGAGTGGTTTGGAGATGAGAATTGG-3′) and HWP1_HindIII_3′ (5′-GACAAGCTTATTGACGAAACTAAAAGCG-3′) or ALS3_XhoI_5′ (5′-CTCGAGCAAGGCTCATATCATAAGCTAACCACC-3′) and ALS3_HindIII_3′ (5′-GACAAGCTTGTTGTAGCATCTAATATTAGCAGTTGG-3′), respectively (underlining indicates XhoI and HindIII restriction sites). The PCR products were digested with XhoI and HindIII and were subcloned into XhoI- and HindIII-digested CIp10::ACT1p-gLUC59 (20), yielding CIp10::HWP1p-gLUC59 and CIp10::ALS3p-gLUC59. These plasmids were linearized by StuI and were transformed into C. albicans CEC161. Integration of reporter constructs at the RPS10 locus in the C. albicans genome was verified by PCR (20). The resulting C. albicans strains, which express the gLUC59 reporter gene under the control of the HWP1 or ALS3 promoter (CEC971 [ura3::λimm434/ura3::λimm434 ARG4/arg4::hisG HIS1/his1::hisG RPS10/RPS10::CIp10-HWP1p-PGA59-gLUC]; CEC939 [ura3::λimm434/ura3::λimm434 ARG4/arg4::hisG HIS1/his1::hisG RPS10/RPS10::CIp10-ALS3p-PGA59-gLUC]), were used to develop mature biofilms (30 h) in the microfermentor system, which were exposed to CAS (5 μg/ml) as described above. Biofilms either left unexposed or exposed to CAS for 1 h were recovered by vortexing at maximum speed for 1 min in 2 ml YNB medium, collected by centrifugation, and resuspended in 5 ml of RLUC buffer (0.5 M NaCl, 0.1 M NaPO4 [pH 6.7], and 1 mM EDTA). The cell suspensions were adjusted to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1.6 using RLUC buffer. Planktonic cells expressing the reporters described above and grown in flasks with or without CAS at similar cell densities were also used. Luciferase activity was assayed using coelenterazine (Molecular Probes, OR; Synchem OHG, Germany) as a substrate. A 5 mM stock solution in methanol was prepared and stored in the dark at −20°C. The substrate was diluted freshly in RLUC buffer to a final concentration of 2.5 μg/ml. A 100-μl volume of the cell suspension was mixed with 100 μl of coelenterazine in a microtiter plate (a flat-bottom black-wall plate; Nunc), and luminescence was recorded immediately using a microtiter plate reader (Infinite M200; Tecan, Austria) with an integration time of 100 ms. Assays were repeated at least twice each with triplicate samples. Planktonic hyphal cells expressing the ALS3p-gLUC59 or HWP1p-gLUC59 fusion were prepared by incubating stationary-phase yeast cells in RPMI medium adjusted with HEPES buffer for 3 h at 37°C with gentle shaking in flasks. Then CAS was added to hyphal cultures to a final concentration of 5 μg/ml, and the incubation was continued for 1 to 2 h at 37°C. Untreated hyphal cultures incubated for 1 to 2 h at 37°C served as controls. Both control and CAS-exposed planktonic hyphal cells were collected by centrifugation, adjusted to an equal cell density (OD600, 1.6), and processed for luciferase assays as mentioned above.

Amphotericin B extraction from biofilms and quantification.

To extract AMB from the biofilm cells/matrix polymers, 1 ml of 100% DMSO was added to biofilms attached to Thermanox plastic slides and placed in a 15-ml Falcon tube, and the tube was vortexed at high speed for 1 min in order to dislodge the biofilm. This mixture was incubated for 5 min at room temperature in the dark. Dislodged biofilms plus the solvent were removed, and the cell-free AMB-containing solvent was collected after microcentrifugation. The biofilm pellets were extracted a second time with another 1 ml of 100% DMSO, and the extracts were saved separately. This extraction method was applied to biofilm samples exposed to AMB at 0, 30, 60, and 120 min. Non-AMB-exposed biofilms were also included as controls. DMSO extracts from biofilms were assayed for their antifungal activity against C. albicans using the broth microdilution assay (15) and were compared to an AMB standard in order to infer the AMB concentration in the extracts. DMSO extracts were examined for their UV-visible absorption maxima by spectroscopic methods (33, 66). Planktonic C. albicans cells in the exponential and stationary phases of growth were also subjected to AMB binding analysis. Absorption maxima at 415 nm of serial dilutions of fresh AMB resuspended in 100% DMSO were used to obtain a standard curve. The ratio between the AMB concentration and the OD415 maximum was linear in the range of concentrations used in this study and allowed quantification of DMSO-extracted AMB by absorption spectra.

AMB binding to β-glucans chitin and gelatin.

Commercial sources of purified water-insoluble β-1,3-glucans (pachyman, derived from Poria cocos [Megazyme, United Kingdom]; β-1,3-glucan from Saccharomyces cerevisiae [Calbiochem]), chitin powder (from crab shells; Sigma), and gelatin (Difco) were employed for AMB binding studies. Pachyman (5 mg), S. cerevisiae β-glucan (2 mg), chitin powder (5 mg), and gelatin (5 mg) were suspended in 0.5 ml sterile water for 5 min. Then 0.5 ml of 16 μg/ml AMB was added to the polymer suspension, which was allowed to stand in the dark for 5 min at room temperature (RT). Unbound AMB was removed by centrifugation (4,000 rpm, 45 s), and the pellets were washed twice each with 1 volume of water. Polymer-bound AMB was extracted once with 1 volume (0.5 ml) of 100% DMSO, and the extracts were scanned for absorption spectra using a spectrophotometer (33, 66).

Microarray data accession number.

The microarray data obtained in this study have been deposited at Array Express under accession number E-MEXP-2436.

RESULTS

Exposure of mature biofilms to antifungals and transcript profiling.

In order to assess the impact on gene expression of exposing mature C. albicans biofilms to various antifungals, we selected antifungal concentrations that, while lethal to planktonic cells, were not lethal to biofilm cells. Biofilms of C. albicans strain SC5314 developed in microfermentors for 30 h (24) were exposed to different concentrations of amphotericin B (AMB), fluconazole (FLU), and caspofungin (CAS) for 1 h or 2 h under flow conditions (see Materials and Methods). Biofilms grown similarly and exposed to an equivalent volume of solvent (100% DMSO or water) were also included as controls. After antifungal or solvent exposure, biofilm cells were recovered by vortexing and were adjusted to equal cell densities (OD600 = 1). Antifungal-exposed and control biofilms were subjected to metabolic activity measurement using FDA hydrolysis and viability determination using FUN-1 staining. Based on these preliminary assays, concentrations of 8 μg/ml AMB, 80 μg/ml FLU, and 5 μg/ml CAS were selected, because more than 80% of the metabolic activity of an untreated biofilm was retained after 2 h of biofilm exposure to these antifungals at these concentrations (data not shown). These concentrations were 10 to 40 times the corresponding MICs for C. albicans strain SC5314 planktonic cells under the same temperature and medium conditions as determined by NCCLS (now CLSI) (15) and EUCAST (data not shown) methods.

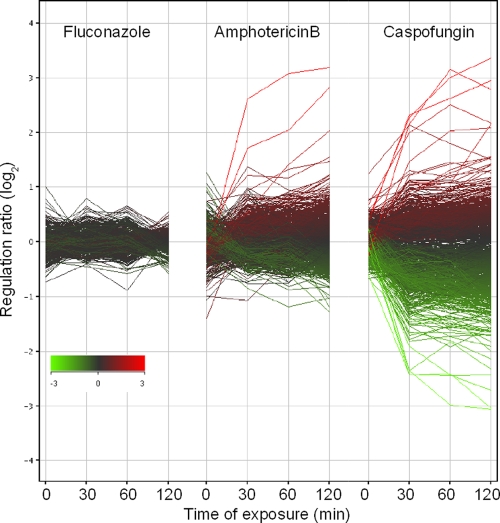

Since we aimed to assess the transcriptional responses of biofilms early after antifungal exposure, 30 h-biofilms exposed for 0 min, 30 min, 60 min, or 120 min to 8 μg/ml AMB, 80 μg/ml FLU, 5 μg/ml CAS, or 0.5 μg/ml CAS and respective control biofilms were collected and subjected to transcript profiling (see Materials and Methods). Genes that were statistically significantly (P, ≤0.05 by a t test) overexpressed or repressed more than 1.5-fold in biofilms exposed to 8 μg/ml AMB, 80 μg/ml FLU, or 5 μg/ml CAS relative to expression in unexposed biofilms at one or more time points were identified (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Because only one biological replicate was obtained for biofilms exposed to 0.5 μg/ml CAS, only those genes that were overexpressed or repressed more than 2-fold relative to expression in unexposed biofilms were identified (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Unexpectedly, under the assay conditions used in this study, biofilms exposed to fluconazole (80 μg/ml) showed no significant change in gene expression, even after a 2-h exposure (Table 1 and Fig. 1).

TABLE 1.

Number of genes differentially expressed upon exposure of mature C. albicans biofilms to fluconazole, amphotericin B, or caspofungin

| Drug (concn [μg/ml]) | No. of genes upregulated/no. of genes downregulateda at: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 min | 60 min | 120 min | 30, 60, and 120 min | 30, 60, or 120 min | |

| FLU (80) | 1/0 | 3/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 4/1 |

| AMB (8) | 26/7 | 38/10 | 82/51 | 14/1 | 98/62 |

| CAS (5) | 90/256 | 132/378 | 191/432 | 41/205 | 256/522 |

| CAS (0.5) | 71/16 | 153/113 | 214/198 | 41/8 | 269/230 |

| CAS (5 and 0.5) | 15/4 | 8/24 | 7/34 | 5/4 | 68/95 |

Genes were counted as up- or downregulated if their expression in a culture exposed to a given antifungal at a given concentration was more than 1.5-fold (for FLU, AMB, or CAS at 5 μg/ml) or more than 2.0-fold (for CAS at 0.5 μg/ml) increased or decreased, respectively, from that in an unexposed culture (P < 0.05).

FIG. 1.

Differential gene expression in mature antifungal-exposed biofilms. Thirty-hour-old C. albicans SC5314 biofilms were exposed to fluconazole (80 μg/ml), amphotericin B (8 μg/ml), or caspofungin (5 μg/ml). Age-matched control biofilms and antifungal-exposed biofilms were collected and subjected to transcript profiling. Data were analyzed and viewed with GeneSpring software. The ratios of gene expression between antifungal-exposed and control biofilms are shown for all C. albicans genes. Graphs are colored according to the ratio observed at 120 min postexposure for each antifungal.

Transcriptional responses of C. albicans biofilms exposed to amphotericin B.

In AMB-exposed biofilms, 98 genes were significantly overexpressed and 62 were underexpressed more than 1.5-fold at one or more time points (Table 1 and Fig. 1). The most relevant regulated genes are listed in Table 2. Of these, only 18 were over- or underexpressed more than 2-fold, and this regulation occurred mainly at the 120-min time point (9/18), indicating that the transcriptional response of biofilms to AMB was modest. Among the 98 overexpressed genes, only 15 have been described as AMB responsive under planktonic conditions (39) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). These 15 genes included 8 of the 10 genes that showed the highest upregulation upon exposure of planktonic cultures to AMB (39), namely, orf19.1774, orf19.2552, orf19.1117, HAK1, CYC1, YHB1, CYS3, and ACO1. However, a large proportion of the 98 genes overexpressed in AMB-exposed biofilms reflected a biofilm-specific transcriptional response to AMB. For instance, a significant number of genes related to amino acid biosynthesis were identified in the overexpressed gene set (Table 2), while this functional category was not overrepresented among genes that are upregulated upon AMB exposure of planktonic cells (39). Moreover, a significant number of genes involved in the process of hyphal formation and hyphal regulation were specifically upregulated in AMB-exposed biofilms (Table 2). These regulations might represent a biofilm-specific response to AMB. Similarly, we identified only one gene, PRE1, that was underexpressed in AMB-exposed biofilms (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) and had been described as downregulated by AMB under planktonic conditions (39).

TABLE 2.

Selected Candida albicans genes showing significantly increased expression (>1.5-fold) upon exposure of mature biofilms to amphotericin B (8 μg/ml)

| Function and IDa | Nameb | Descriptionb | Gene expression ratioc at: |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 min | 60 min | 120 min | |||

| Amino acid biosynthesis | |||||

| orf19.568 | SPE2 | Predicted ORF; possibly adherence induced | 1.691 | 1.732 | 2.298 |

| orf19.6385 | ACO1 | Protein described as aconitase; Gcn4p regulated; amino acid starvation (3-AT treatment), amphotericin B, phagocytosis, farnesol induced; fluconazole downregulated; expression greater under high-iron conditions | 1.087 | 1.096 | 1.753 |

| orf19.6402 | CYS3 | Predicted enzyme of sulfur amino acid biosynthesis; upregulated in biofilms; alkaline upregulated; amphotericin B induced; possibly adherence induced; induced by heavy metal (cadmium) stress, oxidative stress (via Cap1p); Hog1p regulated | 1.584 | 1.527 | 1.731 |

| orf19.4040 | ILV3 | Putative dihydroxyacid dehydratase; upregulated in biofilms; S. cerevisiae ortholog is Gcn4p regulated; repressed by nitric oxide; macrophage-induced protein; farnesol downregulated | 1.271 | 1.234 | 1.674 |

| orf19.198 | ASN1 | Protein described as asparagine synthetase; regulated by Rim101p; decreased expression at pH 4 compared to pH 8 | 1.441 | 1.231 | 1.616 |

| orf19.923 | THR1 | Putative homoserine kinase; transcription is regulated by Tup1p; amphotericin B repressed; regulated by Gcn2p and Gcn4p | 1.286 | 1.271 | 1.587 |

| orf19.6086 | LEU4 | Putative 2-isopropylmalalate synthase; regulated by Nrg1p, Mig1p, Tup1p, Gcn4p; upregulated in the presence of human whole blood or polymorphonuclear cells; macrophage/pseudohyphal repressed after 16 h | 1.025 | 0.991 | 1.553 |

| orf19.7498 | LEU1 | Protein described as 3-isopropylmalate dehydratase; decreased expression in hyphae compared to yeast-form cells; alkaline downregulated; upregulated in the presence of human whole blood or polymorphonuclear cells | 1.553 | 1.648 | 1.535 |

| orf19.2876 | CBF1 | Transcription factor that binds to a conserved sequence at ribosomal protein genes and the rDNA locus, with Tbf1p; also regulates sulfur starvation response and other genes; binds centromeres and has a role in centromere maintenance | 1.601 | 1.328 | 1.224 |

| orf19.3221 | CPA2 | Predicted ORF; protein detected by mass spectrometry in stationary-phase cultures | 1.555 | 1.536 | 1.183 |

| orf19.7469 | ARG1 | Similar to argininosuccinate synthase; enzyme of arginine biosynthesis; increased transcription is observed upon benomyl treatment; regulated by Gcn4p, Rim101p; induced in response to amino acid starvation (3-aminotriazole treatment) | 1.489 | 1.57 | 1.045 |

| Ribosome biogenesis | |||||

| orf19.2111.2 | RPL38 | Predicted ribosomal protein; genes encoding cytoplasmic ribosomal subunits, translation factors, and tRNA synthetases are downregulated upon phagocytosis by murine macrophages | 1.185 | 1.494 | 1.777 |

| orf19.5507 | ENP1 | Protein similar to S. cerevisiae Enp1p; transposon mutation affects filamentous growth; decreased expression in response to prostaglandins | 1.363 | 1.498 | 1.766 |

| orf19.5299 | ECM1 | Decreased mRNA abundance observed in cyr1 homozygous mutant hyphae; induced by heavy metal (cadmium) stress; Hog1p regulated | 1.231 | 1.434 | 1.717 |

| orf19.1642 | Predicted ORF | 1.301 | 1.425 | 1.607 | |

| orf19.3034 | RLI1 | Member of RNase L inhibitor (RLI) subfamily of ABC family; predicted not to be a transporter | 1.607 | 1.32 | 1.588 |

| orf19.76 | SPB1 | Predicted ORF; decreased expression in response to prostaglandins | 1.283 | 1.277 | 1.585 |

| orf19.5198 | NOP4 | Predicted ORF; mutation confers hypersensitivity to 5-FC, 5-FU, and tubercidin (7-deazaadenosine); downregulated in core stress response | 1.3 | 1.412 | 1.571 |

| orf19.7569 | SIK1 | Predicted ORF; physically interacts with TAP-tagged Nop1p | 1.365 | 1.462 | 1.542 |

| orf19.2319 | Predicted ORF; downregulated in core stress response | 1.241 | 1.291 | 1.526 | |

| orf19.1633 | UTP4 | Predicted ORF; physically interacts with TAP-tagged Nop1p | 1.385 | 1.468 | 1.517 |

| orf19.2329.1 | RPS17B | Putative ribosomal protein; genes encoding cytoplasmic ribosomal subunits, translation factors, and tRNA synthetases are downregulated upon phagocytosis by murine macrophages | 1.398 | 1.338 | 1.506 |

| orf19.6686 | ENP2 | Predicted ORF; essential; heterozygous mutation confers resistance to 5-FC, 5-FU, and tubercidin (7-deazaadenosine) | 1.35 | 1.623 | 1.506 |

| orf19.5500 | MAK16 | Predicted ORF; decreased expression in response to prostaglandins | 1.354 | 1.679 | 1.503 |

| orf19.124 | Predicted ORF | 1.336 | 1.53 | 1.367 | |

| Hyphal growth | |||||

| orf19.4445 | Predicted ORF; Plc1p regulated | 2.288 | 2.248 | 2.901 | |

| orf19.5908 | TEC1 | TEA/ATTS transcription factor involved in regulation of hypha-specific genes; required for wild-type biofilm formation; regulates BCR1; directly transcriptionally regulated by Cph2p under some growth conditions; alkaline upregulated | 2.563 | 1.916 | 1.798 |

| orf19.1996 | CHA1 | Protein similar to serine/threonine dehydratases, catabolic; negatively regulated by Rim101p; expression greater under low-iron conditions; regulated on white-opaque switching; filament induced; transposon mutation affects filamentous growth | 1.206 | 1.486 | 1.752 |

| orf19.7359 | CRZ1 | Putative transcription factor; similar to S. cerevisiae calcineurin-regulated transcription factor Crz1p; mutant is fluconazole hypersensitive; likely to act downstream of calcineurin; has C2H2 zinc fingers; not required for mouse virulence | 1.213 | 1.356 | 1.614 |

| orf19.6028 | HGC1 | Hypha-specific G1 cyclin-related protein involved in regulation of hyphal morphogenesis; Cdc28p-Hgc1p maintains Cdc11p S394 phosphorylation during hyphal growth; required for virulence in mouse model; regulated by Nrg1p, Tup1p, farnesol | 1.569 | 1.421 | 1.61 |

| orf19.5265 | KIP4 | Transposon mutation affects filamentous growth; filament induced; shows Mob2p-dependent hyphal regulation; regulated by Nrg1p, Tup1p | x1.136 | 1.499 | 1.58 |

| orf19.3127 | CZF1 | Transcriptional regulator of white-opaque switching frequency; hyphal growth regulator; has C-terminal zinc finger and central Glu-rich region; expression in S. cerevisiae causes dominant-negative inhibition of pheromone response | 1.143 | 1.231 | 1.557 |

| orf19.4012 | PCL5 | Protein similar to S. cerevisiae Pcl5p and other cyclins for Pho85p kinase; Gcn4p induced; suppresses toxicity of C. albicans Gcn4p overproduction in S. cerevisiae via increased Pho85p-dependent phosphorylation and degradation of Gcn4p | 1.439 | 1.67 | 1.554 |

| orf19.5741 | ALS1 | Adhesin; ALS family of cell surface glycoproteins; adhesion, virulence roles; immunoprotective; biofilm induced; Rfg1p, Ssk1p, growth regulated; strain background affects expression | 1.558 | 1.182 | 1.553 |

| orf19.6817 | FCR1 | Putative zinc cluster transcription factor; negative regulator of fluconazole, ketoconazole, brefeldin A resistance; transposon mutation affects filamentous growth; partially suppresses S. cerevisiae pdr1 pdr3 mutant fluconazole sensitivity | 1.215 | 1.349 | 1.548 |

| orf19.1822 | UME6 | Transcription factor; required for wild-type hyphal extension, virulence; zinc cluster DNA-binding motif; similar to S. cerevisiae Ume6p, which is a meiotic regulator; alkaline upregulated; filament induced; regulated by Nrg1p, Tup1p, RFG1p | 1.077 | 1.199 | 1.535 |

| orf19.4892 | TPK1 | Catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA), isoform of Tpk2p; involved in control of morphogenesis and stress response; produced during stationary but not exponential growth | 1.239 | 1.225 | 1.513 |

| orf19.2972 | PDE2 | Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase, high affinity; role in moderating signaling via cAMP; required for wild-type virulence, hyphal growth, switching, and cell wall but not for pseudohyphal growth; expressed shortly after hyphal induction | 1.57 | 1.325 | 1.36 |

| Other functions | |||||

| orf19.6249 | HAK1 | Putative potassium transporter; similar to Schwanniomyces occidentalis Hak1p; amphotericin B induced; transcriptionally induced upon phagocytosis by macrophages | 5.995 | 8.297 | 8.91 |

| orf19.2552 | Protein similar to S. cerevisiae Pmr1p; amphotericin B induced | 3.41 | 4.301 | 7.721 | |

| orf19.2846 | Predicted ORF; induced in core caspofungin response; transcription regulated upon yeast-hypha switch | 1.449 | 2.625 | 4.003 | |

| orf19.6586 | Predicted ORF; increased transcription is observed upon benomyl treatment or in an azole-resistant strain that overexpresses MDR1; shows colony morphology-related gene regulation by Ssn6p; induced by nitric oxide, 17-beta-estradiol | 1.892 | 2.495 | 2.733 | |

| orf19.1774 | Predicted ORF; transcription is upregulated in an RHE model of oral candidiasis; virulence-group-correlated expression | 1.169 | 1.866 | 2.253 | |

| orf19.4773 | AOX2 | Alternative oxidase; induced by antimycin A, some oxidants; growth and carbon source regulated; one of two isoforms (Aox1p and Aox2p); involved in a cyanide-resistant respiratory pathway that is absent from S. cerevisiae | 1.231 | 1.679 | 2.189 |

| orf19.3854 | Protein similar to S. cerevisiae Sat4p; amphotericin B induced; clade-associated gene expression | 1.501 | 1.544 | 2.088 | |

| orf19.1742 | HEM3 | Hydroxymethylbilane synthase (uroporphyrinogen I synthase); catalyzes conversion of 4-porphobilinogen to hydroxymethylbilane, the third step in the heme biosynthetic pathway; transcription greater in high iron, CO2; alkaline downregulated | 1.726 | 1.641 | 1.879 |

| orf19.6899 | Predicted ORF; mutation confers hypersensitivity to toxic ergosterol analog | 1.54 | 1.597 | 1.856 | |

| orf19.2283 | DQD1 | Predicted ORF; ketoconazole repressed; macrophage-downregulated protein abundance | 1.163 | 1.338 | 1.831 |

| orf19.5280 | MUP1 | Alkaline upregulated by Rim101p | 1.494 | 1.358 | 1.827 |

| orf19.4737 | TPO3 | Possible role in polyamine transport; MFS-MDR family; transcription induced by Sfu1p, regulated upon white-opaque switching; decreased expression in hyphae compared to yeast-form cells; regulated by Nrg1p; fungus specific | 1.492 | 1.283 | 1.796 |

| orf19.3707 | YHB1 | Nitric oxide dioxygenase; acts in nitric oxide scavenging/detoxification; role in virulence in mouse; not essential for viability; transcription activated by NO, macrophage interaction; hyphally downregulated | 1.264 | 1.789 | 1.741 |

| orf19.2833 | PGA34 | Putative GPI-anchored protein of unknown function; transcription is repressed in response to alpha pheromone in SpiderM medium | 1.129 | 1.317 | 1.696 |

| orf19.2251 | AAH1 | Protein not essential for viability; similar to S. cerevisiae Aah1p, which is an adenine deaminase involved in purine salvage and nitrogen catabolism; shows colony morphology-related gene regulation by Ssn6p; Hog1p, biofilm, CO2 induced | 1.696 | 1.407 | 1.69 |

| orf19.3378 | Predicted ORF; regulated by Tsa1p, Tsa1Bp in minimal medium at 37°C | 1.012 | 1.321 | 1.69 | |

| orf19.5992 | WOR2 | Transcriptional regulator of white-opaque switching; required for maintenance of opaque state | 1.752 | 1.399 | 1.684 |

| orf19.6073 | HMX1 | Heme oxygenase; acts in utilization of hemin iron; gene transcriptionally activated by heat, low iron, or hemin; negatively regulated by Efg1p; expression greater in low iron; upregulated by Rim101p at pH 8 | 1.682 | 1.811 | 1.648 |

| orf19.4152 | CEF3 | Translation elongation factor 3 (EF-3); polystyrene adherence induced | 1.013 | 1.108 | 1.628 |

| orf19.4526 | HSP30 | Protein described as similar to heat shock protein; fluconazole downregulated; amphotericin B induced | 0.928 | 1.567 | 1.623 |

| orf19.2654 | RMS1 | Protein induced during the mating process | 1.519 | 1.575 | 1.613 |

| orf19.3664 | HSP31 | Protein repressed during the mating process | 1.043 | 1.173 | 1.59 |

| orf19.4377 | KRE1 | Predicted GPI anchor, role in 1,6-β-d-glucan biosynthesis; caspofungin induced | 1.456 | 1.442 | 1.573 |

| orf19.7042 | Increased transcription is observed upon benomyl treatment or in an azole-resistant strain that overexpresses MDR1; induced by nitric oxide | 1.487 | 1.854 | 1.559 | |

| orf19.1770 | CYC1 | Cytochrome c; transcriptionally regulated by iron; expression greater in high iron; alkaline downregulated; repressed by nitric oxide | 1.588 | 1.85 | 1.543 |

| orf19.7370 | Member of family of putative 7-transmembrane, PQ loop-family of G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) similar to Schizosaccharomyces pombe Stm1p | 1.504 | 1.404 | 1.541 | |

| orf19.5893 | RIP1 | Protein described as subunit of ubiquinol cytochrome c reductase; transcriptionally regulated by iron; expression greater in high iron; alkaline downregulated; repressed by nitric oxide | 1.182 | 1.092 | 1.536 |

| orf19.451 | SOK1 | Transcription is induced in response to alpha pheromone in SpiderM medium | 1.133 | 1.259 | 1.534 |

| orf19.3756 | CHR1 | Predicted DEAD-box ATP-dependent RNA helicase, functional homolog of S. cerevisiae Rok1p | 1.2 | 1.373 | 1.525 |

| orf19.909 | STP4 | Putative transcription factor with zinc finger DNA-binding motif; induced in core caspofungin response; shows colony morphology-related gene regulation by Ssn6p; induced by 17-beta-estradiol, ethynyl estradiol | 1.163 | 1.397 | 1.524 |

| orf19.4335 | TNA1 | Putative nicotinic acid transporter; detected at germ tube plasma membrane by mass spectrometry; transcriptionally induced upon phagocytosis by macrophages | 1.435 | 1.176 | 1.521 |

| orf19.2467 | PRN1 | Protein with similarity to pirins; increased transcription is observed upon benomyl treatment and in response to alpha pheromone in SpiderM medium; transcriptionally activated by Mnl1p under weak acid stress | 0.964 | 1.506 | 1.521 |

| orf19.789 | PYC2 | Putative pyruvate carboxylase, binds to biotin cofactor; upregulated in mutant lacking the Ssk1p response regulator protein, upon benomyl treatment, or in an azole-resistant strain overexpressing MDR1 | 1.529 | 1.288 | 1.516 |

| orf19.336 | YAH1 | Similar to oxidoreductases; transcriptionally regulated by iron; expression greater in high iron | 1.195 | 1.317 | 1.514 |

| orf19.1926 | SEF2 | Putative zinc cluster protein; expression is repressed by Sfu1p under high-iron conditions | 1.199 | 1.555 | 1.257 |

Underlining of a gene identifier (ID) indicates that the gene is known to be upregulated upon exposure of a C. albicans planktonic culture to amphotericin B (39).

Gene names and descriptions were obtained from the Candida Genome Database (http://www.candidagenome.org). ORF, open reading frame; 3-AT, 3-aminotriazole; 5-FC, flucytosine; 5-FU, 5-fluorouracil; ALS, agglutinin-like sequence; cAMP, cyclic AMP; RHE, reconstituted human epithelium; MFS, major facilitator superfamily; MDR, multidrug resistance; GPI, glycosylphosphatidylinositol.

Ratios with P values of <0.05 are shown in roman type, and ratios with P values of ≥0.05 are shown in italics.

Transcriptional responses of C. albicans biofilms exposed to caspofungin.

In contrast to FLU or AMB, CAS elicited much more significant changes in gene expression at the two concentrations tested (0.5 or 5 μg/ml). A total of 256 genes were overexpressed at one or more time points at 5 μg/ml CAS, while 269 were overexpressed at one or more time points at 0.5 μg/ml CAS (Table 1 and Fig. 1). A total of 522 genes were underexpressed at one or more time points at 5 μg/ml CAS, and 230 genes were underexpressed at 0.5 μg/ml CAS (Table 1 and Fig. 1; see also Table S1 in the supplemental material).

Sixty-eight genes were overexpressed at one or more time points at both CAS concentrations (Table 3; see also Table S1 in the supplemental material). Among these, only 4 have been identified as induced by CAS under planktonic conditions (39), namely, ACO1, CRH11, orf19.5698, and orf19.3681, suggesting that CAS elicited dramatically different transcriptional responses in planktonic and biofilm cultures.

TABLE 3.

Differential expression (>1.5-fold or <1.5-fold) of selected C. albicans genes upon exposure of mature biofilms to caspofungin for 30, 60, or 120 min

| Function and IDa | Nameb | Descriptionb | Expression ratioc after exposure to CAS for the indicated time at: |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 μg/ml |

0.5 μg/ml |

|||||||

| 30 min | 60 min | 120 min | 30 min | 60 min | 120 min | |||

| Upregulated genes | ||||||||

| Biofilm formation | ||||||||

| orf19.1321 | HWP1 | Hyphal cell wall protein; covalently cross-linked to epithelial cells by host transglutaminase; opaque and a specific, α-factor induced; at MTLa side of conjugation tube | 3.989 | 5.567 | 4.328 | 4.242 | 5.062 | 3.78 |

| orf19.1816 | ALS3 | Adhesin; ALS family; role in epithelial adhesion, endothelial invasiveness; predicted GPI anchor cell wall protein; induced by macrophages, hyphae; pH, Nrg1p, Rfg1p, Tup1p regulated | 2.389 | 3.06 | 2.915 | 2.859 | 3.552 | 4.257 |

| orf19.3374 | ECE1 | Protein comprising eight 34-residue repeats; hypha-specific expression increases with extent of elongation of the cell; regulated by Rfg1p, Nrg1p, Tup1p, Cph1p, Efg1p, Hog1p, farnesol, phagocytosis; may contribute to biofilm formation | 4.473 | 3.474 | 2.837 | 1.954 | 3.472 | 4.451 |

| orf19.1327 | RBT1 | Putative cell wall protein with similarity to Hwp1p, required for virulence; Tup1p repressed; serum, hypha, and alkaline induced; farnesol, α-factor induced; Rfg1p, Rim101p regulated | 1.738 | 1.788 | 2.019 | 4.066 | 4.746 | 3.931 |

| orf19.5171 | PMT1 | Protein mannosyltransferase, required for virulence in mouse systemic infection and for adhesion to epithelial cells; has a role in hyphal growth and drug sensitivity | 1.465 | 1.386 | 1.581 | 1.439 | 2.279 | 2.787 |

| orf19.5908 | TEC1 | TEA/ATTS transcription factor involved in regulation of hypha-specific genes; required for wild-type biofilm formation; regulates BCR1; directly transcriptionally regulated by Cph2p under some growth conditions; alkaline upregulated | 1.538 | 1.376 | 1.448 | 1.726 | 2.546 | 2.11 |

| orf19.3618 | YWP1 | Protein with suggested role in dispersal in host; mutation causes increased adhesion and biofilm formation; putative GPI anchor; cell wall and secreted; has stable propeptide; regulated by growth phase, phosphate, Ssk1p, Ssn6p, Efg1p, Efh1p | 1.719 | 1.525 | 1.413 | 0.804 | 2.42 | 3.753 |

| Hyphal regulation | ||||||||

| orf19.663 | GIN4 | Kinase involved in pseudohypha-to-hypha switch; phosphorylates Cdc11p on S395 (regulatory); autophosphorylates; necessary for septin ring within germ tube but not for septin band at mother cell junction; role in cytokinesis | 1.176 | 1.487 | 1.657 | 1.589 | 2.869 | 2.482 |

| orf19.1822 | UME6 | Transcription factor; required for wild-type hyphal extension, virulence; zinc cluster DNA-binding motif; filament induced; regulated by Nrg1p, Tup1p, RFG1p | 1.479 | 1.504 | 1.457 | 1.591 | 2.443 | 3.352 |

| Cell wall | ||||||||

| orf19.2767 | PGA59 | Putative GPI-anchored protein of unknown function; shows colony morphology-related gene regulation by Ssn6p | 2.423 | 2.758 | 2.402 | 2.202 | 2.252 | 2.383 |

| orf19.2685 | PGA54 | Putative GPI-anchored protein; hypha induced; Hog1p downregulated; induced in a cyr1 or efg1 homozygous null mutant; shows colony morphology-related gene regulation by Ssn6p; upregulated in an RHE model | 1.481 | 2.046 | 2.228 | 1.526 | 2.298 | 2.421 |

| orf19.2765 | PGA62 | Putative GPI-anchored protein; fluconazole induced; transcriptionally regulated by iron; expression greater in high iron; induced during cell wall regeneration; Cyr1p or Ras1p downregulated; transcription is positively regulated by Tbf1p | 2.308 | 3.057 | 2.047 | 1.937 | 2.302 | 1.406 |

| orf19.7610 | PTP3 | Protein not essential for viability; similar to S. cerevisiae Ptp3p, which is a protein tyrosine phosphatase; hypha induced; alkaline upregulated; regulated by Efg1p, Ras1p, cAMP pathways | 1.659 | 1.789 | 1.993 | 1.409 | 1.747 | 2.203 |

| orf19.4152 | CEF3 | Translation elongation factor 3 (EF-3); localizes to surface of yeast form, not hyphae; polystyrene adherence induced | 2.258 | 2.184 | 1.952 | 2.494 | 3.168 | 3.893 |

| orf19.1618 | GFA1 | Glucosamine-6-phosphate synthase; enzyme of chitin/hexosamine biosynthesis; growth phase regulated | 1.634 | 1.625 | 1.871 | 1.838 | 2.001 | 2.331 |

| orf19.2706 | CRH11 | Putative ortholog of S. cerevisiae Crh1p; predicted glycosyl hydrolase domain; predicted Kex2p substrate; putative GPI anchor; localizes to cell wall; caspofungin induced | 1.415 | 1.529 | 1.743 | 1.375 | 1.783 | 2.472 |

| orf19.1390 | PMI1 | Phosphomannose isomerase; cell wall biosynthesis enzyme; Gcn4p regulated; repressed by 3-AT; induced upon adherence to polystyrene, phagocytosis | 1.393 | 1.235 | 1.726 | 1.454 | 1.867 | 2.288 |

| orf19.6081 | PHR2 | Glycosidase; role in cell wall structure; may act on β-1,3-glucan prior to β-1,6-glucan linkage; role in vaginal but not systemic virulence (low pH, not neutral); low pH, high iron, fluconazole induced; Rim101p downregulated at pH 8 | 1.252 | 1.361 | 1.713 | 1.505 | 1.919 | 3.164 |

| orf19.6367 | SSB1 | Putative heat shock protein; SSB subfamily of the HSP70 family; mRNA in yeast-form cells, germ tubes; at surfaces of yeast-form cells but not hyphae; soluble in hyphae; macrophage, GCN induced | 1.874 | 1.868 | 1.518 | 1.754 | 1.982 | 3.059 |

| orf19.4765 | PGA6 | Putative GPI-anchored cell wall protein of unknown function; similar to S. cerevisiae Ccw12p/Ylr110cp; transcriptionally regulated by iron; expression greater in high iron; upregulated upon Als2p depletion | 1.162 | 1.512 | 1.511 | 2.297 | 3.421 | 6.175 |

| orf19.2251 | AAH1 | Protein not essential for viability; similar to S. cerevisiae Aah1p, which is an adenine deaminase involved in purine salvage and nitrogen catabolism; shows colony morphology-related gene regulation by Ssn6p; Hog1p, biofilm, CO2 induced | 1.319 | 1.528 | 1.411 | 3.398 | 1.949 | 2.808 |

| orf19.1065 | SSA2 | HSP70 family chaperone; role in sensitivity to, import of beta-defensin peptides; ATPase domain binds histatin 5; at surfaces of hyphae but not yeast-form cells; farnesol downregulated in biofilms; caspofungin repressed | 1.731 | 1.624 | 1.372 | 1.947 | 2.434 | 3.249 |

| orf19.4311 | YNK1 | Nucleoside diphosphate kinase (NDP kinase); homohexameric; soluble protein in hyphae; flucytosine induced; biofilm induced; macrophage-induced protein | 1.52 | 1.429 | 1.327 | 1.396 | 1.932 | 2.153 |

| Ribosome biogenesis and RNA metabolic process | ||||||||

| orf19.1601 | RPL3 | Putative ribosomal protein; similar to S. cerevisiae Rpl3p; gene induced by ciclopirox olamine treatment; genes encoding cytoplasmic ribosomal subunits are downregulated upon phagocytosis by murine macrophage | 2.181 | 2.001 | 2.105 | 1.829 | 2.583 | 3.252 |

| orf19.6873 | RPS8A | Putative ribosomal protein; similar to S. cerevisiae Rps8Bp; gene is induced by ciclopirox olamine treatment; genes encoding cytoplasmic ribosomal subunits are downregulated upon phagocytosis by murine macrophage | 1.819 | 1.691 | 2.007 | 1.548 | 2.051 | 2.176 |

| orf19.7015 | RPP0 | Putative ribosomal protein; antigenic in mouse; biofilm induced; cytoplasmic ribosomal subunit, translation factor, and tRNA synthetase genes are downregulated upon phagocytosis by murine macrophages; transcription induced by Tbf1p | 1.598 | 1.681 | 1.764 | 1.744 | 1.94 | 3.082 |

| orf19.1833 | Predicted ORF | 1.673 | 1.757 | 1.686 | 1.979 | 2.418 | 2.55 | |

| orf19.2960 | FRS2 | Putative tRNA-Phe synthetase; genes encoding ribosomal subunits, translation factors, and tRNA synthetases are downregulated upon phagocytosis by murine macrophages | 1.498 | 1.376 | 1.547 | 1.898 | 2.786 | 2.616 |

| orf19.3599 | TIF4631 | Putative translation initiation factor eIF4G; overexpression causes hyperfilamentation; hypha and macrophage induced; genes encoding some translation factors are downregulated upon phagocytosis by murine macrophages | 1.477 | 1.586 | 1.54 | 1.323 | 2.12 | 1.998 |

| orf19.6355 | Predicted ORF | 1.388 | 1.463 | 1.509 | 1.468 | 1.63 | 2.273 | |

| orf19.2319 | Predicted ORF; downregulated in core stress response | 1.565 | 1.338 | 1.504 | 1.692 | 1.934 | 2.028 | |

| orf19.2564 | Predicted ORF | 1.379 | 1.569 | 1.49 | 2.048 | 1.817 | 2.497 | |

| orf19.7217 | RPL4B | Putative ribosomal protein; genes encoding cytoplasmic ribosomal subunits, translation factors, and tRNA synthetases are downregulated upon phagocytosis by murine macrophages | 1.774 | 1.514 | 1.482 | 1.721 | 2.559 | 3.288 |

| orf19.5106 | DIP2 | Protein similar to S. cerevisiae Dip2p, of small ribonucleoprotein complex; transposon mutation affects filamentous growth | 1.549 | 1.516 | 1.472 | 2.133 | 2.64 | 3.105 |

| orf19.4093 | NOP7 | Pescadillo homolog required for filament-to-yeast switching; mutation confers hypersensitivity to 5-FC, 5-FU, and tubercidin (7-deazaadenosine) | 1.911 | 1.485 | 1.464 | 2.121 | 2.586 | 2.237 |

| orf19.6906 | ASC1 | Protein described as part of 40S ribosomal subunit; similar to G-beta subunits; soluble in hyphae; iron, temp, Gcn4p regulated; amino acid starvation (3-aminotriazole), caspofungin repressed | 1.512 | 1.476 | 1.462 | 1.906 | 2.374 | 3.123 |

| orf19.7569 | SIK1 | Predicted ORF; physically interacts with TAP-tagged Nop1p | 1.702 | 1.349 | 1.435 | 1.872 | 2.147 | 2.457 |

| orf19.5698 | Putative ribosomal protein, transcription is upregulated in clinical isolates from HIV-positive patients with oral candidiasis | 1.515 | 1.439 | 1.434 | 1.494 | 2.811 | 2.47 | |

| orf19.4051 | HTS1 | Putative tRNA-His synthetase; genes encoding ribosomal subunits, translation factors, and tRNA synthetases are downregulated upon phagocytosis by murine macrophages | 1.528 | 1.465 | 1.415 | 1.939 | 2.941 | 2.176 |

| orf19.3138 | NOP1 | Nucleolar protein; flucytosine induced | 1.635 | 1.491 | 1.407 | 3.087 | 3.536 | 4.297 |

| orf19.6589 | Predicted ORF | 1.708 | 1.327 | 1.383 | 2.161 | 2.513 | 2.606 | |

| orf19.1199 | NOP5 | Protein similar to S. cerevisiae Nop5p protein of small nucleolar ribonucleoprotein complex; transposon mutation affects filamentous growth; macrophage/pseudohypha induced | 2.027 | 1.461 | 1.38 | 3.254 | 4.134 | 5.428 |

| orf19.5500 | MAK16 | Predicted ORF; decreased expression in response to prostaglandins | 1.552 | 1.079 | 1.356 | 2.147 | 2.225 | 2.893 |

| orf19.5991 | Predicted ORF | 1.586 | 1.27 | 1.317 | 1.838 | 2.094 | 2.867 | |

| orf19.1609 | Predicted ORF | 1.558 | 1.34 | 1.308 | 2.187 | 2.21 | 2.121 | |

| orf19.5198 | NOP4 | Predicted ORF; mutation confers hypersensitivity to 5-FC, 5-FU, and tubercidin (7-deazaadenosine); downregulated in core stress response | 1.53 | 1.126 | 1.179 | 1.808 | 1.79 | 2.404 |

| Downregulated genes | ||||||||

| Generation of precursor metabolites and energy | Ratio 30 min | Ratio 60 min | Ratio 120 min | Ratio 30 min | Ratio 60 min | Ratio 120 min | ||

| orf19.7227 | Predicted ORF; mutation confers hypersensitivity to toxic ergosterol analog | 0.389 | 0.496 | 0.334 | 0.632 | 0.559 | 0.342 | |

| orf19.3278 | GSY1 | Protein described as glycogen synthase; enzyme of glycogen metabolism; transcription downregulated upon yeast-hypha switch and regulated by Efg1p; induced by strong oxidative stress; shows colony morphology-related gene regulation by Ssn6p | 0.605 | 0.65 | 0.463 | 0.719 | 0.566 | 0.385 |

| orf19.2841 | PGM2 | Protein not essential for viability; similar to S. cerevisiae Pgm2p, which is phosphoglucomutase | 0.476 | 0.411 | 0.507 | 0.578 | 0.43 | 0.302 |

| orf19.7481 | MDH1 | Protein described as malate dehydrogenase, mitochondrial; transcription regulated by Mig1p and Tup1p, white-opaque switching; induced in high iron, biofilms; regulated upon phagocytosis | 0.574 | 0.572 | 0.538 | 0.624 | 0.412 | 0.286 |

| orf19.4773 | AOX2 | Alternative oxidase; induced by antimycin A, some oxidants; growth and carbon source regulated; one of two isoforms (Aox1p and Aox2p); involved in a cyanide-resistant respiratory pathway that is absent from S. cerevisiae | 0.85 | 0.853 | 0.568 | 0.885 | 0.572 | 0.34 |

| orf19.5113 | ADH2 | Putative alcohol dehydrogenase; soluble protein in hyphae; expression is regulated upon white-opaque switching; regulated by Ssn6p; transcriptionally activated by Mnl1p under weak acid stress | 0.551 | 0.555 | 0.574 | 0.548 | 0.326 | 0.243 |

| orf19.6602 | Predicted ORF | 0.576 | 0.61 | 0.58 | 0.631 | 0.493 | 0.329 | |

| orf19.744 | GDB1 | Putative glycogen debranching enzyme; expression is regulated upon white-opaque switching; regulated by Nrg1p, Tup1p | 0.667 | 0.631 | 0.588 | 0.636 | 0.632 | 0.476 |

| orf19.2608 | ADH5 | Putative alcohol dehydrogenase; expression is regulated upon white-opaque switching; fluconazole induced; antigenic during systemic murine infection; regulated by Nrg1p, Tup1p; macrophage-downregulated protein | 0.454 | 0.552 | 0.591 | 0.667 | 0.426 | 0.219 |

| orf19.3997 | ADH1 | Alcohol dehydrogenase; at surfaces of yeast-form cells but not hyphae; regulated by growth phase, carbon source; fluconazole induced | 0.649 | 0.674 | 0.677 | 0.907 | 0.737 | 0.496 |

| Response to stress | ||||||||

| orf19.2762 | AHP1 | Putative alkyl hydroperoxide reductase; biofilm induced; fluconazole induced; amphotericin B, caspofungin, alkaline downregulated; induced in core stress response; regulated by Ssk1p, Nrg1p, Tup1p, Ssn6p, Hog1p | 0.318 | 0.349 | 0.32 | 0.606 | 0.443 | 0.373 |

| orf19.2344 | ASR1 | Protein described as similar to heat shock proteins; transcription regulated by cAMP, osmotic stress, ciclopirox olamine, ketoconazole; negatively regulated by Cyr1p, Ras1p; shows colony morphology-related gene regulation by Ssn6p | 0.358 | 0.364 | 0.329 | 0.434 | 0.305 | 0.268 |

| orf19.6059 | TTR1 | Putative glutaredoxin; described as a glutathione reductase; upregulated in the presence of human neutrophils and upon benomyl treatment; alkaline downregulated; regulated by Gcn2p and Gcn4p; required for virulence in a mouse model | 0.463 | 0.436 | 0.416 | 0.584 | 0.464 | 0.471 |

| orf19.6349 | RVS162 | Predicted ORF | 0.486 | 0.507 | 0.421 | 0.744 | 0.466 | 0.37 |

| orf19.3537 | Predicted ORF in assemblies 19, 20, and 21; regulated by Tsa1p, Tsa1Bp in minimal medium at 37°C | 0.533 | 0.608 | 0.448 | 0.842 | 0.38 | 0.344 | |

| orf19.1153 | GAD1 | Protein described as glutamate decarboxylase; macrophage-downregulated gene; alkaline downregulated; amphotericin B induced; transcriptionally activated by Mnl1p under weak acid stress | 0.469 | 0.491 | 0.473 | 0.652 | 0.524 | 0.393 |

| orf19.2770.1 | SOD1 | Cytosolic copper- and zinc-containing superoxide dismutase, involved in protection from oxidative stress and required for full virulence; alkaline upregulated by Rim101p; upregulated in the presence of human blood | 0.574 | 0.596 | 0.555 | 0.646 | 0.472 | 0.505 |

| orf19.3150 | GRE2 | Protein described as a reductase; transcription is regulated by Nrg1p and Tup1p; benomyl induced; hypha induced; macrophage/pseudohypha repressed; expression greater in low iron; reported to be involved in osmotic stress response | 0.692 | 0.557 | 0.569 | 0.668 | 0.503 | 0.471 |

| orf19.6973 | Predicted ORF; regulated by Gcn2p and Gcn4p | 0.634 | 0.598 | 0.573 | 0.628 | 0.558 | 0.473 | |

| orf19.882 | HSP78 | Protein described as a heat shock protein; transcriptionally regulated by macrophage response; transcription is regulated by Nrg1p, Mig1p, Gcn2p, Gcn4p, Mnl1p; heavy metal (cadmium) stress induced | 0.623 | 0.689 | 0.587 | 0.774 | 0.628 | 0.468 |

| orf19.6757 | GCY1 | Predicted ORF; mutation confers hypersensitivity to toxic ergosterol analog | 0.679 | 0.582 | 0.597 | 0.5 | 0.397 | 0.301 |

| orf19.1891 | APR1 | Vacuolar aspartic proteinase; mRNA abundance is equivalent in yeast-form and mycelial cells but is elevated at lower growth temperatures; upregulated in the presence of human neutrophils | 0.696 | 0.532 | 0.625 | 0.714 | 0.623 | 0.481 |

| orf19.5620 | Predicted ORF; regulated by Gcn4p; induced in response to amino acid starvation (3-aminotriazole treatment); increased transcription is observed upon benomyl treatment or in an azole-resistant strain that overexpresses MDR1 | 0.519 | 0.585 | 0.639 | 0.758 | 0.486 | 0.442 | |

| orf19.2480.1 | AUT7 | Predicted ORF; macrophage/pseudohypha repressed | 0.501 | 0.535 | 0.641 | 0.597 | 0.463 | 0.324 |

| orf19.7196 | Protein described as a vacuolar protease; upregulated in the presence of human neutrophils | 0.596 | 0.593 | 0.685 | 0.724 | 0.527 | 0.43 | |

| Possible link to cell wall or hyphae | ||||||||

| orf19.822 | Predicted ORF; protein detected in some, not all biofilm extracts; fluconazole downregulated; greater mRNA abundance observed in a cyr1 or ras1 homozygous null mutant than in wild type; transcription is upregulated in response to treatment with ciclopirox olamine | 0.203 | 0.291 | 0.204 | 0.553 | 0.363 | 0.205 | |

| orf19.6601.1 | YKE2 | Possible cytoskeletal modulator; transcription induced upon yeast-to-hypha switch; regulated by Nrg1p, Tup1p | 0.303 | 0.351 | 0.324 | 0.647 | 0.398 | 0.324 |

| orf19.2531 | CSP37 | Plasma membrane, hyphal cell wall protein; role in progression of murine systemic infection; expressed in yeast and hyphae; hyphally downregulated | 0.354 | 0.27 | 0.345 | 0.364 | 0.224 | 0.156 |

| orf19.2758 | PGA38 | Putative GPI-anchored protein of unknown function; repressed during cell wall regeneration | 0.517 | 0.446 | 0.398 | 0.691 | 0.379 | 0.265 |

| orf19.2768 | AMS1 | Putative alpha-mannosidase; transcription is regulated by Nrg1p; induced during cell wall regeneration | 0.416 | 0.493 | 0.455 | 0.583 | 0.436 | 0.323 |

| orf19.2613 | ECM4 | Protein similar to S. cerevisiae Ecm4p; transcription is regulated by Nrg1p and Tup1p; induced in core stress response or in cyr1 or ras1 homozygous null mutant (yeast-form or hyphal cells); transposon mutation affects filamentous growth | 0.66 | 0.511 | 0.547 | 0.503 | 0.382 | 0.272 |

| orf19.4318 | MIG1 | Transcriptional repressor; regulates genes for utilization of carbon sources; Tup1p-dependent and -independent functions; upregulated in biofilms; hyphally downregulated; caspofungin repressed; functional homolog of S. cerevisiae Mig1p | 0.553 | 0.577 | 0.625 | 0.815 | 0.632 | 0.488 |

| orf19.5635 | PGA7 | Protein described as a putative precursor of a hyphal surface antigen; putative GPI anchor; induced by ciclopirox olamine, ketoconazole, or by Rim101p at pH 8; regulated during planktonic growth; induced during cell wall regeneration | 0.638 | 0.683 | 0.731 | 0.752 | 0.506 | 0.373 |

| orf19.4477 | CSH1 | Member of aldo-keto reductase family, similar to aryl alcohol dehydrogenases; role in adhesion to fibronectin, cell surface hydrophobicity; regulated by temp, growth phase, benomyl, macrophage interaction; azole resistance associated | 0.775 | 0.655 | 0.86 | 0.438 | 0.397 | 0.366 |

Underlining of a gene identifier (ID) indicates that the gene is known to be upregulated or downregulated upon exposure of a C. albicans planktonic culture to caspofungin (39).

Gene names and descriptions were obtained from the Candida Genome Database (http://www.candidagenome.org).

Ratios with a P value of <0.05 are shown in roman type, and ratios with a P value of ≥0.05 are shown in italics.

Analysis of these 68 genes revealed a significant overrepresentation of genes that have previously been associated with biofilm formation. Indeed, HWP1, ALS3, ECE1, YWP1, PMT1, TEC1, and RBT1 (19, 26, 50-52, 57) were overexpressed in CAS-exposed biofilms (Table 3). A subset of these genes has also been shown to play important roles in hyphal morphogenesis and function, and it is noteworthy that other regulators of hyphal morphogenesis, such as UME6 and GIN4 (9, 12, 70, 73), were overexpressed in CAS-exposed biofilms. Moreover, 14 CAS-overexpressed genes encoded cell wall proteins, of which 7 are putative glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored proteins, suggesting that exposure of mature biofilms to CAS resulted in intense cell wall remodeling. Interestingly, the GSC1 gene, encoding a catalytic subunit of β-1,3-glucan synthase (43), the CAS target, was overexpressed only at 0.5 μg/ml CAS (Table 3). In contrast, the GSL1 and GSL2 genes, which encode other subunits of the β-1,3-glucan synthase (43), were not overexpressed in biofilms exposed to CAS. In addition, 23 genes overexpressed in CAS-exposed biofilms encoded proteins involved in ribosome biogenesis or RNA metabolic processes, suggesting that CAS elicited a modification of the metabolic activity in biofilms. Yet this probably did not reflect paradoxical growth of CAS-exposed biofilms, since upregulation of these genes was also observed at 0.5 μg/ml CAS, a concentration that does not elicit paradoxical growth in planktonic cultures.

Ninety-five genes were underexpressed at one or more time points at both CAS concentrations (Table 3). An enrichment in genes involved in the generation of precursor metabolites and energy, including the three alcohol dehydrogenase genes ADH1, ADH2, and ADH5, and in glycogen metabolism was observed. A significant number of genes linked to stress responses were also underexpressed in CAS-exposed biofilms (Table 3). Of the 399 C. albicans genes that have been shown to be downregulated in planktonic cultures exposed to CAS (39), only 24 were downregulated in CAS-exposed biofilms, among which were alcohol dehydrogenase genes and other genes involved in the generation of precursor metabolites and energy (Table 3).

ALS3 and HWP1 gene expression is CAS induced in biofilms only.

The data presented above revealed that the ALS3 and HWP1 genes, encoding two cell surface GPI-anchored adhesins that have been shown to participate in biofilm formation (50, 77), were systematically and significantly upregulated at all time points following exposure of C. albicans biofilms to CAS (Table 2). In contrast, these genes had not been identified as being upregulated in planktonic cultures exposed to CAS. In order to confirm this result, two C. albicans strains that express the gLUC59 reporter gene, encoding an artificial cell surface luciferase (20) under the control of the ALS3 or HWP1 promoter region, were constructed. Biofilms formed by these strains using the microfermentor model were exposed to CAS (5 μg/ml) or to a solvent, and the luciferase activity was measured. The results presented in Table 4 showed that expression of the ALS3p-gLUC59 or HWP1p-gLUC59 fusion increased upon exposure to CAS, confirming the transcript profiling data. Moreover, when exponentially growing or stationary-phase planktonic cells expressing the ALS3p-gLUC59 or HWP1p-gLUC59 fusion were exposed to CAS, no increase in luciferase activity was observed, suggesting that CAS-mediated upregulation of the ALS3 and HWP1 genes was biofilm specific. Biofilms contain yeast, pseudohyphal, and hyphal cells. Because the exponentially growing and stationary-phase planktonic cultures used in the experiment described above contained mainly yeast cells, we also exposed cells expressing the ALS3p-gLUC59 or HWP1p-gLUC59 fusion and undergoing the yeast-to-hypha transition to CAS. Planktonic hyphal cells did not respond to CAS by upregulating the ALS3 or HWP1 gene (data not shown). Thus, the upregulation of ALS3 and HWP1 in response to CAS is a biofilm-specific response.

TABLE 4.

Luciferase activity in caspofungin-exposed biofilms or planktonically grown C. albicans strains expressing the ALS3p-gLUC59 or HWP1p-gLUC59 gene fusiona

| Gene fusion | Luciferase activity of cells exposed to caspofungin at the indicated concnb |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biofilms |

Planktonic cells |

||||

| 0 μg/ml | 5 μg/ml | 0 μg/ml | 2.5 μg/ml | 5 μg/ml | |

| ALS3p-gLUC59 | 3,174 ± 152 | 11,822 ± 2,007 | 1,742 ± 447 | 1,388 ± 447 | 1,254 ± 287 |

| HWP1p-gLUC59 | 94,627 ± 15,544 | 175,815 ± 21,978 | 3,502 ± 836 | 2,996 ± 666 | 2,800 ± 477 |

Thirty-hour-old biofilms on Thermanox plastic slides or 20-h-old YNB medium-grown planktonic cells of C. albicans strains expressing the ALS3p-gLUC59 or HWP1p-gLUC59 gene fusion were exposed to CAS at the indicated concentrations, and relative luciferase activity encoded by the gLUC59 reporter gene was measured. Values are means and standard deviations of five independent measurements obtained for one experiment. Experiments were repeated at least twice, and representative values are given.

Luciferase activity is expressed in relative luciferase units (RLU).

Amphotericin B binds to mature biofilms.

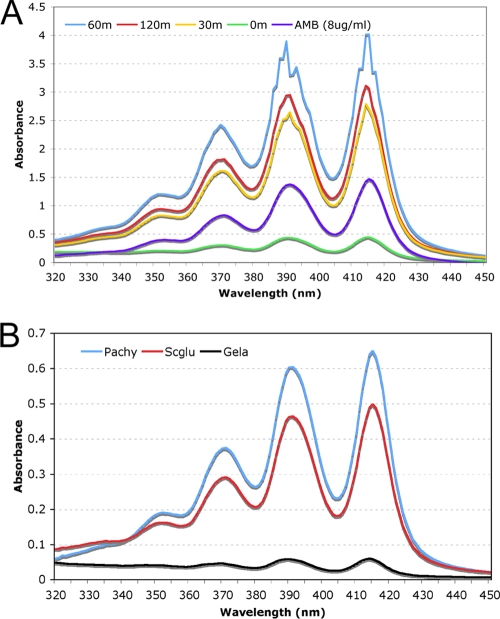

In the course of the experiments described above, we noticed that exposure of mature 30-h biofilms to 8 μg/ml AMB resulted in a change of color of the biofilm. While biofilms exposed to the solvent were white, AMB-exposed biofilms rapidly became yellow. Maximum coloration was observed after 60 min of AMB exposure (data not shown). Since AMB-exposed biofilms maintain metabolic activity (see above), this change in biofilm color was unlikely to reflect a loss of viability of the biofilm cells following exposure to AMB. AMB is yellow with absorption maxima around 390, 415 (monomeric), 365, and 336 nm (dimeric or aggregate) in organic or aqueous solutions (33, 66), suggesting that the yellow color of the biofilm might reflect binding of AMB to the biofilm. Since AMB is soluble in DMSO, AMB-exposed and control biofilms were subjected to two rounds of 100% DMSO extraction, and the resulting extracts were scanned for UV-visible spectral properties (Fig. 2) and evaluated for their abilities to inhibit C. albicans growth. DMSO extracts from unexposed control biofilms did not show AMB-specific spectra (data not shown). In contrast, the data in Table 5 showed that while an equivalent of 2.7 μg of AMB could be recovered from biofilms exposed to AMB for less than 1 min, 6.9- to 12.3-fold-higher levels could be recovered from biofilms exposed to AMB for 30, 60 or 120 min. A decrease in AMB concentration in the microfermentor flowthrough medium was also observed at these time points, even though AMB saturation of the biofilm might have been reached at 120 min postexposure. This decrease was dependent on the presence of a biofilm in the microfermentor (data not shown). All extracts from AMB-treated biofilms showed anticandidal activity when assessed using a broth microdilution assay in microtiter plates. Importantly, the anticandidal activity was comparable to that obtained using AMB stocks with concentrations equivalent to those defined through UV absorption spectra of the biofilm extracts (data not shown). This indicated that AMB extracted from biofilms remained active against planktonic cells. When similar experiments were performed using planktonic cells, no significant binding of AMB was observed (data not shown). Taken together, these data suggested that AMB was able to bind biofilms and remained active upon binding.

FIG. 2.

UV-visible absorption spectra of AMB extracted from biofilms and β-1,3-glucans. (A) One hundred percent DMSO (1 ml) was used to extract AMB-exposed biofilms (0, 30, 60, and 120 min post-AMB exposure), and extracts were scanned for absorption maximum spectra. The biofilm medium containing AMB (8 μg/ml) was also scanned in parallel as a control. (B) Insoluble β-1,3-glucans derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Scglu) and Poria cocos (Pachy) were incubated with AMB. After removal of unbound AMB, polymer-bound AMB was extracted by 100% DMSO and analyzed as described for panel A. Gelatin (as a nonspecific control) was treated similarly for AMB binding and was analyzed in parallel.

TABLE 5.

Quantitation of AMB recovered from AMB-exposed biofilms through DMSO extraction

| Duration of AMB exposure (min)a | Amt of AMB in DMSO extracts (μg)b |

AMB concn in biofilms (μg/ml)c | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st extract | 2nd extract | Total | ||

| 0 | 2.13 | 0.53 | 2.66 | 4.43 |

| 30 | 14.39 | 4.27 | 18.66 | 31.1 |

| 60 | 21.85 | 11.19 | 33.06 | 55.1 |

| 120 | 16.52 | 15.46 | 31.98 | 53.3 |

Mature 30-h biofilms were exposed for the indicated time to a flow of AMB-containing medium (8 μg AMB/ml) and were extracted twice using 1 ml 100% DMSO.

AMB in the DMSO extracts was quantified based on maxima in UV-visible spectra.

Determined using an estimated volume of 0.6 ml for mature 30-h biofilms.

We estimated the volume of mature 30-h biofilms on the plastic slide as 0.6 ml. Based on the recovery of AMB from the biofilms (Table 5), we estimated that the concentration of AMB associated with the biofilm cells and matrix was at least 55.1 μg/ml after 60 min, remaining constant later on. This AMB concentration was 6.8 times higher than that in the surrounding medium (8 μg/ml). Moreover, we did not consider the medium circulating in the biofilm, thus underestimating the actual concentration of AMB associated with the biofilm cells and matrix. This indicated that AMB associated relatively avidly with the biofilm despite its lack of efficacy against biofilm cells and its inability to elicit a strong transcriptional response in biofilm cells.

Amphotericin B binds to β-glucans.

C. albicans biofilms produce abundant extracellular polymeric material during biofilm growth under flow conditions. This biofilm matrix is thought to consist mainly of soluble β-glucans (2, 27, 49). Importantly, it has been shown previously that fluconazole binds β-glucans and that altering β-glucans in biofilms increases the susceptibility of biofilms to FLU, suggesting that cell wall or matrix β-glucans could prevent FLU from reaching biofilm cells and exerting its antifungal effect (49). Our observation that AMB bound biofilms prompted us to test whether AMB was also able to bind purified β-glucans. AMB was incubated with β-glucans from different commercial sources, as well as with chitin, an N-acetylglucosamine polymer that is a component of the C. albicans cell wall, and gelatin, a proteinaceous polymer. The polymers were subsequently washed and subjected to DMSO extraction, and UV/visible spectra of the resulting extracts were obtained. The data in Fig. 2B showed that AMB could be recovered from β-glucans, while no AMB was found associated with gelatin or chitin (data not shown). Thus, AMB appeared to bind specifically to β-glucans.

DISCUSSION

In order to better understand the mechanisms that confer antifungal resistance to C. albicans biofilms, we have undertaken a transcript profiling analysis of mature biofilms that were exposed to three different antifungal agents from the major families of antifungal agents, i.e., polyenes (e.g., AMB), azoles (e.g., FLU), and echinocandins (e.g., CAS). Surprisingly, FLU, though used at a high concentration (80 μg/ml), did not significantly affect the level of gene expression in C. albicans biofilms at any time point of exposure, except for 5 genes with very marginal regulation. AMB triggered relatively mild modifications in gene expression, even though we used 10 times the MIC for planktonic cells. Only 15 genes were upregulated by a factor greater than 2 at one or more time points. Half of these genes have previously been shown to be induced in response to AMB exposure under planktonic conditions (39), suggesting that the transcriptional response of biofilms to AMB overlaps that of planktonic cells. Yet most of the genes that were upregulated to a lesser extent in biofilms exposed to AMB have not been identified as upregulated in antifungal-treated planktonic cells (39), resistant clinical strains (65), or strains in which resistance was laboratory induced (10). Notably, we did not observe any change in the expression of ergosterol and fatty acid biosynthesis genes, although such changes were observed under planktonic conditions (39). Moreover, AMB exposure resulted in marginal downregulation of genes. In contrast to AMB- or FLU-exposed biofilms, CAS exposed biofilms exhibited marked changes in gene expression, irrespective of the concentration used. Very few of the genes that we identified as up- or downregulated upon exposure of biofilms to CAS have been described previously as regulated by CAS under planktonic conditions, highlighting a specific transcriptional response of biofilms to CAS. There was a relative overlap between CAS- and AMB-responsive genes in biofilms, including genes involved in amino acid biosynthesis and ribosomal biogenesis. Taken together, our data showed that antifungals elicit a transcriptional response in C. albicans biofilms that is distinct from that elicited in C. albicans planktonic cells. Moreover, the extent of the transcriptional response of biofilms to antifungals appeared well correlated to the efficacy of these antifungals toward biofilms, with caspofungin eliciting higher transcriptome alterations than amphotericin B and amphotericin B eliciting higher transcriptome alterations than fluconazole (2, 28, 35, 49, 59, 69, 71).

One striking difference between biofilm and planktonic cells was the upregulation in CAS-exposed biofilms of several genes coding for cell wall proteins, in particular ALS3 and HWP1, which play important roles in biofilm formation (50, 77). Since this observation resulted from the comparison of our transcript profiling data with those reported by others for CAS-exposed planktonic cells (39), we examined the expression of ALS3 and HWP1 by using C. albicans strains where expression of the gLUC59 gene encoding an artificial cell surface luciferase (20) was driven by the ALS3 or HWP1 promoter. Our data showed that CAS induced the expression of HWP1 and ALS3 when C. albicans was growing in biofilms, while it had no effect on the expression of these genes in C. albicans planktonic yeast or hyphal cells. These data confirmed the specificity of the response of biofilms to CAS. Complementary roles have been demonstrated for Als1/Als3 and Hwp1 during biofilm growth in vitro or in vivo; the interaction between these adhesins is responsible for interactions between hyphae and consequently for biofilm cohesiveness (53). In this regard, increased levels of the Als3 and Hwp1 proteins might provide a defense mechanism against the deleterious effects of CAS by increasing biofilm cohesiveness. Additionally, the increased expression of genes encoding other cell wall proteins might help to protect the cell wall from reduced β-1,3-glucan biosynthesis, since several of these proteins, such as Phr2, Pga59, Pga62, and Crh11, have been proven to contribute to cell wall integrity (23, 44, 55).

In a previous report, Nett et al. (49) showed that FLU binds to β-1,3-glucans, structural components of the fungal cell wall as well as of the biofilm ECM, and that altering β-1,3-glucans increases the sensitivity of biofilms to FLU and AMB. Here we have observed that AMB binds to biofilms as well as to β-1,3-glucans, while it does not bind other polymers, such as chitin and gelatin. Binding to the polyanionic biofilm matrix (32) and specifically to β-1,3-glucans might be facilitated by the amphiphilic nature of AMB. Our data indicated that high concentrations of AMB could be reached within the biofilm. This is similar to what has been observed for FLU and flucytosine, which, despite accumulating in the biofilm at concentrations above the MIC, are unable to kill biofilm cells completely (3). Taken together, these observations suggest that AMB, FLU, and other antifungals are retained within the ECM through their affinity for β-1,3-glucans. Entrapment of AMB and FLU in the ECM might prevent them from reaching biofilm cells, and this may explain the limited transcriptional responses of biofilm cells to these antifungals. This mechanism might not act in the case of caspofungin, which shows effectiveness against biofilms and elicits a significant transcriptional response in biofilm cells. Thus, the ECM might play a central role in the resistance of C. albicans to a subset of antifungals. This hypothesis is consistent with the observation that biofilms with increased matrix polymers display increased resistance to antifungals (27, 45). Yet it does not exclude the possibility that other resistance mechanisms are operating in C. albicans biofilms. Of interest, such a role of matrix components in resistance to antimicrobials has been proposed for bacterial biofilms (31, 32, 72). A genetic basis for the resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms to various antibiotics (tobramycin, gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, and chloramphenicol) has been linked to glucan production by this bacterium (41). Those authors showed the physical binding of tobramycin to purified glucans from P. aeruginosa, suggesting that glucans prevent antibiotics from reaching their sites of action by a sequestration mechanism. Bacterial ECM polymers, such as polysaccharides or DNA, can limit the diffusion of antibiotics or elicit a protective response through the quenching of cations, respectively (4, 48). Thus, the use of biofilm matrix components as a barrier against antimicrobial molecules appears to be conserved in prokaryotic and eukaryotic biofilms, and strategies aimed at preventing matrix production may find useful applications in the fight against biofilm-borne infections.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Caroline Proux and Jean-Yves Coppée at the PF2 Platform of Pasteur Genopole Ile-de-France for help with microarray experiments. Caspofungin was kindly provided by Merck & Co. Fluconazole was kindly provided by Pfizer Inc.