Abstract

By choosing membranes as targets of action, antibacterial peptides offer the promise of providing antibiotics to which bacteria would not become resistant. However, there is a need to increase their potency against bacteria along with achieving a reduction in toxicity to host cells. Here, we report that three de novo-designed antibacterial peptides (ΔFm, ΔFmscr, and Ud) with poor to moderate antibacterial potencies and kill kinetics improved significantly in all of these aspects when synergized with rifampin and kanamycin against Escherichia coli. (ΔFm and ΔFmscr [a scrambled-sequence version of ΔFm] are isomeric, monomeric decapeptides containing the nonproteinogenic amino acid α,β-didehydrophenylalanine [ΔF] in their sequences. Ud is a lysine-branched dimeric peptide containing the helicogenic amino acid α-aminoisobutyric acid [Aib].) In synergy with rifampin, the MIC of ΔFmscr showed a 34-fold decrease (67.9 μg/ml alone, compared to 2 μg/ml in combination). A 20-fold improvement in the minimum bactericidal concentration of Ud was observed when the peptide was used in combination with rifampin (369.9 μg/ml alone, compared to 18.5 μg/ml in combination). Synergy with kanamycin resulted in an enhancement in kill kinetics for ΔFmscr (no killing until 60 min for ΔFmscr alone, versus 50% and 90% killing within 20 min and 60 min, respectively, in combination with kanamycin). Combination of the dendrimeric peptide ΔFq (a K-K2 dendrimer for which the sequence of ΔFm constitutes each of the four branches) (MIC, 21.3 μg/ml) with kanamycin (MIC, 2.1 μg/ml) not only lowered the MIC of each by 4-fold but also improved the therapeutic potential of this highly hemolytic (37% hemolysis alone, compared to 4% hemolysis in combination) and cytotoxic (70% toxicity at 10× MIC alone, versus 30% toxicity in combination) peptide. Thus, synergy between peptide and nonpeptide antibiotics has the potential to enhance the potency and target selectivity of antibacterial peptides, providing regimens which are more potent, faster acting, and safer for clinical use.

With the rapid emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, extensive efforts have been focused on the development of new classes of antimicrobial agents (32). Naturally occurring, cationic antibacterial peptides are promising candidates in this search for novel therapeutic agents. Antibacterial peptides have been isolated from a wide variety of organisms ranging from bacteria to humans (5, 14). They target the membranes as well as paralyze the cellular functions of bacteria (4, 13). The merits inherent to these peptides as antimicrobials include low chances of bacterial resistance and a broad spectrum of action. Therefore, they are suitable templates to develop future antibiotics. However, in spite of the isolation of ∼1,000 naturally occurring antibacterial peptides to date (http://www.bbcm.units.it/∼tossi/pag1.htm), drawbacks such as poor potency, specificity, and in vivo stability have permitted only a few to be clinically useful (15). For their effective translation from discovery in research laboratories to use in clinics, antibacterial peptides have to be rid of these shortcomings. Therefore, efforts have been focused on modifying antibacterial peptides to increase their potency and specificity.

Previous findings have shown that the activity and selectivity of antibacterial peptides are governed by physicochemical factors such as charge, amphipathicity, and hydrophobicity (9, 12, 18, 31). Based on these results, several groups have attempted to improve the activity and specificity of these peptides by altering their sequence, length, charge, etc. (6, 19, 23, 28). For example, Ahmad et al. have shown that substitution of a leucine zipper sequence with alanine abrogates the hemolytic activity of the bee venom antibacterial peptide melittin (1). However, such peptide-directed approaches are time-consuming, as they involve detailed studies and require a number of sequence modifications to generate improved analogs. In contrast, synergy in antibiotic action relies on the abilities of two different molecules to exert a greater deleterious effect on the target organism than the sum of the effects due to each drug alone. Synergy reduces the dose of each drug in the combination, and such combination therapy is also well known to prevent the development of resistance in bacteria (3, 29). These features have been instrumental to a revived interest in the study of synergy in antibiotic action in several laboratories (8, 11, 20, 21, 25, 30).

In the present work, we have studied the prospects of synergy between antimicrobial peptide and nonpeptide antibiotics. Here, we have identified a few interesting combinations which showed impressive synergistic complementation (evaluated by fractional inhibitory concentration [FIC] indices). Interestingly, the peptides that showed synergy in our study, when assessed individually, suffered from poor to moderate antibacterial potency (MIC, 67.9 to 135.8 μg/ml [concentration, 30 to 100 μM]) or poor selectivity for bacterial membranes (as evidenced by the high hemolytic activity of the dendrimeric peptide ΔFq [see Results] at its MIC). In contrast, there is a dramatic increase in antibacterial potency in these peptides when delivered in combination with the nonpeptide antibiotics kanamycin and rifampin. In addition to potency, we have found that synergy has a beneficial influence on other aspects of antibacterial activity, such as kill kinetics, bactericidal action, and selectivity. Our results show that synergy is an extremely effective strategy to enhance the activity and specificity of antibacterial peptides without modifying their sequences. We report that synergy of peptide and nonpeptide antibiotics (i) improves the activity of peptides which exhibit poor potency and kill kinetics, thus increasing the number of candidates for antibacterial therapeutics, and (ii) reduces the undesirable toxic effects of antibiotic peptides to host cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Amino acid derivatives and resin for peptide synthesis were obtained from Nova Biochem; diisopropylcarbodiimide (DIPCDI), piperidine, dimethyl formamide (DMF), dichloromethane (DCM), hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt), isobutylchloroformate (IBCF), trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), triisopropyl silane (TIS), dl-threo-β-phenylserine, sodium hydroxide, citric acid, 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), bovine serum albumin (BSA), and N-methyl morpholine (NMM) were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO); sodium chloride, acetic anhydride, and tetrahydrofuran (THF) were from Qualigens (Mumbai, India); ethyl acetate, diethyl ether, sodium acetate, and sodium sulfate were from Merck (Mumbai, India); silica gel thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plates (60F-254) were from Merck (Germany); acetic acid was from SD Fine Chem Limited (Mumbai, India); acetonitrile was from Burdick and Jackson (Muskegon, MI); rifampin and kanamycin sulfate were from HiMedia Laboratories Pvt. Ltd. (Mumbai, India); and RPMI 1640 and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA).

Preparation of Fmoc-X-dl-threo-β-phenylserine.

Fmoc-X-dl-threo-β-phenylserine (where Fmoc is 9-fluorenylmethoxy carbonyl and X is Gly, Lys [Boc], or Ala) was synthesized by a method of salt coupling using mixed anhydride. Fmoc amino acid (15 mmol) (dissolved in 15 ml of sodium-refluxed and distilled THF) was activated at −15°C for 10 min with IBCF and NMM (15 mmol each). A solution of 15 mmol of dl-threo-β-phenylserine made in 1 equivalent of NaOH (15 ml) was added to the mixed anhydride, and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight. Following evaporation of THF, citric acid was added to the aqueous solution to attain a solution of pH ∼2. The precipitate obtained was dissolved in 100 ml ethyl acetate and transferred to a separating funnel. Following the removal of the lower aqueous layer, the ethyl acetate layer was washed extensively with water to remove citric acid. The complete removal of citric acid was confirmed using pH paper. The ethyl acetate layer was washed with brine and allowed to pass through a bed of anhydrous sodium sulfate. Evaporation of ethyl acetate on a rotary evaporator resulted in solid dipeptide acids.

Preparation of Fmoc-X-ΔPhe azalactone.

Fmoc-X-dl-threo-β-phenylserine was mixed with recrystallized anhydrous sodium acetate (obtained by fusing the salt and allowing it to cool in a desiccator) in freshly distilled acetic anhydride and stirred overnight. The thick slurry obtained was mixed with ice and stirred in a cold room. Following trituration, the yellow dipeptide azalactone was filtered on a sinter funnel and dried to constant weight. The authenticity and purity of the azalactones were assessed by TLC, mass spectroscopy, and UV-visible spectroscopy.

Peptide synthesis.

Peptides were synthesized as C-terminal amides using standard Fmoc chemistry on rink amide MBHA (4-methylbenzhydrylamine hydrochloride salt) resin in the manual mode, with DIPCDI and HOBt as coupling agents. Fmoc-Lys (Fmoc)-OH was used to make a branching core for the synthesis of the lysine-branched dimer Ud, containing the helicogenic amino acid α-aminoisobutyric acid (Aib). Piperidine treatment of the lysine derivative immobilized on the resin gave rise to two amino groups (α and Σ), allowing the synthesis of two identical peptide chains, as shown in Table 1. The synthesis of the dendrimer ΔFq was accomplished on a K-K2 core generated by coupling of Fmoc-Lys (Fmoc)-OH to the two amino groups of the lysine resin synthesized as described above. The side-chain protections used were Pmc (Arg) and Boc (Lys, Trp). Couplings were carried out using DMF at a 4-fold molar excess at final concentrations of ∼500 mM. Removal of Fmoc was carried out using 20% piperidine in DMF. Both the coupling of amino acids and the Fmoc deprotection were monitored by the Kaiser test (17). ΔPhe was introduced into peptides as an Fmoc-X-ΔPhe azalactone (where X is Gly, Lys [Boc], or Ala) dipeptide block (24), which was allowed to couple overnight in DMF. At the completion of assembly of the peptides, following Fmoc removal, the amino termini were acetylated using 20% acetic anhydride in DCM. After acetylation of the peptides, the resin was washed extensively with DMF, DCM, and methanol and dried in a desiccator under vacuum.

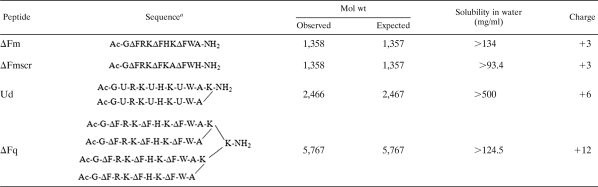

TABLE 1.

Sequences and physicochemical properties of peptides used in this study

ΔF, α,β-didehydrophenylalanine; U, α-aminoisobutyric acid.

Cleavage of the peptides from resin.

Peptides were cleaved by stirring the resin in a cleavage mixture (95% TFA, 2.5% water, and 2.5% TIS) for 2 h at room temperature. The suspension was filtered using a sinter funnel, TFA was rotary evaporated, and the peptide was precipitated by adding cold dry ether. The ether was filtered through a sinter funnel, and the peptide on the funnel was dissolved in 5% acetic acid and lyophilized.

Peptide purification and mass spectrometry.

Crude peptides were purified by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RPHPLC) using a water-acetonitrile gradient (C18 PRC-ODS column [2 by 15 cm, 15 μm, flow rate of 5 ml/min; Shimadzu]; gradient of 5 to 75% acetonitrile and 0.1% TFA for 70 min, with detection at 214 and 280 nm). The identity of the highly purified (>95%) peptides was confirmed by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry performed at ICGEB, New Delhi, India.

Solubility measurements.

Water was added to the purified peptide powders to attain complete dissolution, and the concentration of peptide in the spun supernatant (13,000 rpm, 10 min) was determined by measurement of the absorbance at 280 nm (ɛ280, 19,000 M−1cm−1 for α,β-didehydrophenylalanine [ΔF] and 5,050 M−1cm−1 for tryptophan).

Antibiotic susceptibility testing.

MICs were determined against Escherichia coli ML35p according to a modified MIC method for cationic antimicrobial peptides (26). Bacterial cells grown overnight were diluted in Mueller-Hinton (MH) broth to a cell density of 105 CFU/ml. A portion (100 μl) of this culture was aliquoted into the wells of a 96-well, flat-bottomed microtiter plate (Costar), and 11 μl of 10× stock of each peptide (in 0.2% BSA and 0.01% acetic acid) was added. This mixture was incubated at 37°C in a rotary shaker incubator (Kuhner, Switzerland) set at 200 rpm. After 18 h of incubation, the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was measured using a microtiter plate reader (VERSA max tunable; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). The MIC is defined as the lowest concentration of a drug that inhibits the measurable growth of an organism after overnight incubation. Peptide concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically at 280 nm (ɛ280, 19,000 M−1cm−1 for ΔF and 5,050 M−1cm−1 for tryptophan). Each experiment was done in triplicate and was repeated at least twice.

Minimum bactericidal concentrations (MBC) were determined by plating 100 μl from each clear well of the MIC experiment on MH agar plates in triplicate. After incubation for 18 h, the MBC was identified as the lowest concentration that did not permit growth of 99.9% bacteria on the agar surface.

Bacterial kill kinetics.

Overnight cultures of E. coli ML35p were diluted in MH broth to a working cell density of 105 CFU/ml. The antibiotics were added to 100 μl of the diluted culture, and this suspension was incubated at 37°C, 200 rpm, in a rotary shaker incubator (Kuhner, Switzerland). At regular intervals after antibiotic addition, samples were removed, diluted, and plated onto MH agar plates. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 20 h and colonies counted.

Hemolytic-activity testing.

Human blood in 10% citrate phosphate dextrose was obtained from the Rotary Blood Bank, New Delhi. Red blood cells (RBCs) were harvested by spinning (1,000 × g, 5 min, room temperature). They were washed three to five times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The packed cell volume obtained was used to make a 0.4% (vol/vol) suspension in PBS. A portion (100 μl) of this RBC suspension was transferred to each well of a 96-well microtiter plate and mixed with 100 μl of peptide solution at twice the desired concentration. For the synergy combinations, 50 μl of 4× the desired concentration of each antibiotic was mixed and 100 μl of this mixture was added to 100 μl of the RBC suspension. The microtiter plate was incubated (37°C, 60 min) and centrifuged (1,000 × g, 5 min, room temperature). The supernatant (100 μl) was transferred to new wells, and the OD414 was measured with a microtiter plate reader (VERSA max tunable; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) to monitor RBC lysis. Cells incubated with PBS alone acted as the negative control, and RBCs lysed using 0.1% Triton X-100 were used to measure 100% lysis.

Mammalian-cell cytotoxicity.

Cytotoxicity of the antibiotics individually and in combination was determined using an MTT assay against HeLa cells and L929 fibroblasts. Briefly, cells (5 × 104 cells/well) were cultured at 37°C overnight in RPMI 1640 containing 10% fetal bovine serum in 96-well microtiter plates. After removal of the medium, cells were incubated (37°C, 24 h) with 0.1 ml of peptide antibiotics, nonpeptide antibiotics, their synergy combinations (at 1× and 10× MIC), or 10% DMSO (positive control), all prepared in RPMI 1640. Untreated cells served as the negative control. Twenty microliters of MTT solution (5 mg/ml) in PBS was added, and the cells were incubated (37°C, 2 h). Supernatant (120 μl) was removed, DMSO (0.1 ml) was added, and the resulting suspension was mixed to dissolve the formazan crystals formed by MTT reduction. The ratio of OD570 for treated cells to OD570 for untreated cells was used to calculate percent viability.

Checkerboard dilution assay for synergy.

Synergy was measured by a checkerboard titration method in which individual drugs or mixtures of two drugs were incubated with bacteria to observe bactericidal effects (30). Stocks (40× the desired final concentration) of individual drugs were prepared in water. A portion (12.5 μl) of each stock was mixed with 12.5 μl of water (for testing of individual drug samples) or 12.5 μl of a second drug stock solution (for testing of drugs in combination). A portion (25 μl) of each 20× sample thus prepared was mixed with 25 μl of 0.4% BSA and 0.02% acetic acid to make a 10× stock of the drug or drug mixture. E. coli ML35p cells grown overnight were diluted in Mueller-Hinton (MH) broth to a cell density of 105 CFU/ml. A portion (100 μl) of this culture was aliquoted into the wells of a 96-well, flat-bottomed microtiter plate (Costar), and 11 μl of the 10× stock of the drug mixture was added to the bacterial cell suspension. This mixture was incubated at 37°C in a rotary shaker incubator (Kuhner, Switzerland) set at 200 rpm. After 18 h of incubation, the OD600 was measured with a microtiter plate reader (VERSA max tunable; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). The MIC is defined as the lowest concentration of a drug that inhibits the measurable growth of an organism after overnight incubation. The fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) index for each drug mixture (drug A and drug B) was computed using the following equation: FIC index = (MIC A combination/MIC A alone) + (MIC B combination/MIC B alone). Peptide combinations with an FIC index of ≤0.5 were considered to show synergy of antibiotic action (30).

RESULTS

Synergy between peptide and nonpeptide antibiotics.

De novo-designed peptides which incorporated the essential requirements of antimicrobial peptide design, i.e., amphipathicity, positive charge, and a helical conformation (31), were synthesized. All peptides used in this study (ΔFm, ΔFmscr, Ud, and ΔFq) were highly soluble (>93 to 500 mg/ml) in water (Table 1). ΔFm and ΔFmscr (a scrambled-sequence version of ΔFm) (Table 1) are isomeric, monomeric decapeptides containing the nonproteinogenic amino acid α,β-didehydrophenylalanine (ΔF) in their sequences. Such didehydroamino acids are well known to constrain peptides in a helical conformation (24). Previous results from our laboratory established that ΔFm (MIC of 135.8 μg/ml [concentration of 100 μM] and MBC of >611.1 μg/ml [>500 μM]) has poor potency and kill kinetics (no killing effects observed in 60 min even at 4× MIC) against Escherichia coli ML35p (10). As shown in the present work, ΔFmscr was only moderately active against E. coli ML35p (MIC of 67.9 μg/ml [50 μM]). Ud is a lysine-branched dimeric peptide containing the helicogenic amino acid α-aminoisobutyric acid (Aib) and has a moderate potency against E. coli ML35p (MIC of 73.9 μg/ml [30 μM] and MBC of 369.9 μg/ml [150 μM]) (10). The fourth peptide, ΔFq, is a K-K2 dendrimer for which the sequence of ΔFm constitutes each of the four branches (Table 1). ΔFq is a potent, broad-spectrum antibiotic, with action on both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacterial membranes (MIC of 21.3 μg/ml [3.7 μM] against E. coli ML35p and 23 μg/ml [4 μM] against Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 23219). However, this peptide is highly hemolytic (37% hemolysis at MIC).

Synergy between ΔFm, ΔFmscr, Ud, and ΔFq and two nonpeptide antibiotics, kanamycin and rifampin (Fig. 1), was tested in vitro by the checkerboard dilution assay against E. coli ML35p (Table 2). Each antibiotic combination was assigned a fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) index (see Materials and Methods). FIC indices of ≤0.5 were considered to be synergistic. ΔFm, ΔFmscr, and Ud (Table 1) showed synergy with rifampin or kanamycin in inhibiting bacterial growth. Our results (Table 2) indicated that rifampin or kanamycin caused a significant enhancement in the potencies of the antibacterial peptides. In combination with rifampin, the observed potentiations of antibacterial activity were ∼16-fold for ΔFm (MIC of 135.8 to 8.4 μg/ml), 34-fold for ΔFmscr (MIC of 67.9 to 2 μg/ml), and ∼17-fold for Ud (MIC of 73.9 to 4.4 μg/ml). These results demonstrate that synergizing peptide and nonpeptide antibiotics represents a good strategy to improve antibacterial potency and thus the cost-effectiveness of antibacterial peptides.

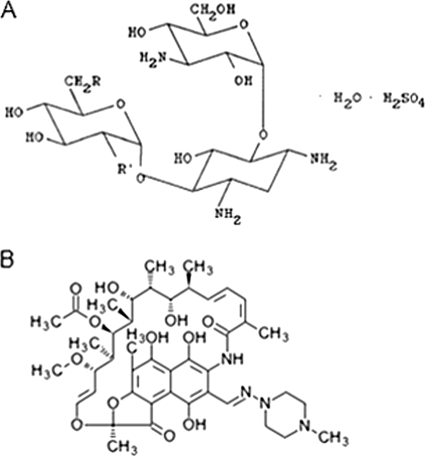

FIG. 1.

Chemical structures of kanamycin (22) (A) and rifampin (KEGG drug database) (B).

TABLE 2.

Synergistic activities of tested antibiotic combinations

| Peptide antibiotic | Nonpeptide antibiotic | MIC, μg/ml (concn, μM) |

FIC index | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide antibiotic |

Nonpeptide antibiotic |

|||||

| Nonsynergy | Synergy | Nonsynergy | Synergy | |||

| ΔFm | Rifampin | 135.8 (100) | 8.4 (6.2) | 3.6 (4.4) | 0.9 (1.1) | 0.3 |

| Kanamycin | 135.8 (100) | 33.9 (25) | 2.1 (3.6) | 0.5 (0.9) | 0.5 | |

| ΔFmscr | Rifampin | 67.9 (50) | 2 (1.5) | 3.6 (4.4) | 0.4 (0.5) | 0.14 |

| Kanamycin | 67.9 (50) | 16.9 (12.5) | 2.1 (3.6) | 0.5 (0.9) | 0.5 | |

| Ud | Rifampin | 73.9 (30) | 4.4 (1.8) | 3.6 (4.4) | 0.4 (0.5) | 0.17 |

| ΔFq | Kanamycin | 21.3 (3.7) | 5.1 (0.9) | 2.1 (3.6) | 0.5 (0.9) | 0.5 |

Effect of synergy on bactericidal activity.

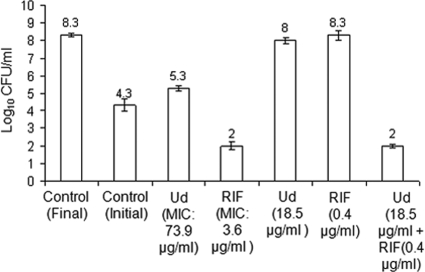

Antimicrobial agents can be classified into bacteriostatic and bactericidal agents. Bacteriostatic drugs inhibit the growth of bacteria while bactericidal drugs are known to kill them. In order to study the bactericidal properties of antibiotic combinations, we determined the minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) of the synergistic combination of Ud (individual MBC, 369.9 μg/ml) and rifampin (individual MBC, 3.6 μg/ml) against E. coli ML35p. As shown in Fig. 2, the combination of Ud (combination MBC, 18.5 μg/ml) and rifampin (combination MBC, 0.4 μg/ml) was bactericidal. The fractional bactericidal concentration (FBC) index for the combination was very low (0.16), indicating strong synergy toward bactericidal action. Thus, rifampin acts as a potentiator of bactericidal activity by causing a 20-fold improvement in the MBC of Ud, from 369.9 μg/ml (Ud alone) to 18.5 μg/ml (Ud plus rifampin). It is noteworthy that the concentrations of both Ud and rifampin needed to achieve the augmentation in bactericidal activity were significantly reduced when the agents were used in combination. This suggests that synergy with a nonpeptide drug has the potential to convert a weakly bacteriostatic drug to a highly potent bactericidal one.

FIG. 2.

Synergy in bactericidal action. Histogram showing results for untreated and antibiotic-treated samples of E. coli ML35p. The antibiotic concentrations used are indicated below the bars. Cells were treated with or without drug for 18 h and plated on MH agar plates. After 20 h of incubation at 37°C, the colonies were counted. Synergy in bactericidal activity was observed for Ud and rifampin at an FBC index of 0.16. The log10 CFU/ml observed at the end point is indicated above each bar. Standard deviations from triplicate experiments are plotted. RIF, rifampin.

Effect of synergy on bacterial kill kinetics.

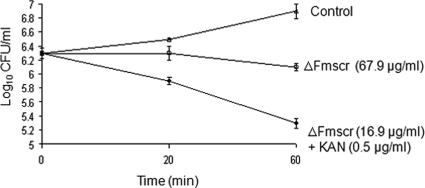

Another important parameter of the performance of an antibiotic is the rate at which it kills the target bacterium. Faster killing action of an antibiotic should correspond to faster clearance of bacterial load in a patient. To test whether a synergistic combination of antibiotics can influence the rate of bacterial killing, the kill kinetics of ΔFmscr (MIC of 67.9 μg/ml) alone was compared to that of the synergistic combination (Table 2) of ΔFmscr (MIC of 16.9 μg/ml) and kanamycin (MIC of 0.5 μg/ml) against E. coli ML35p. At 60 min, ΔFmscr (MIC of 67.9 μg/ml) alone was largely bacteriostatic (Fig. 3). However, in synergy with kanamycin, ΔFmscr showed both a 4-fold improved potency (MIC of 16.9 μg/ml) and faster kill kinetics (1 log10 CFU/ml decrease in 60 min). Therefore, in addition to the improvement in potency of antibacterial peptides, the rate of bacterial killing can be improved by synergizing the peptides with nonpeptide antibiotics.

FIG. 3.

Synergy enhances kill kinetics of antimicrobial peptides. Kill kinetics of ΔFmscr and the combination of ΔFmscr and kanamycin (KAN) at an FIC index of 0.5 against E. coli ML35p at the concentrations indicated.

Effect of synergy on peptide toxicity.

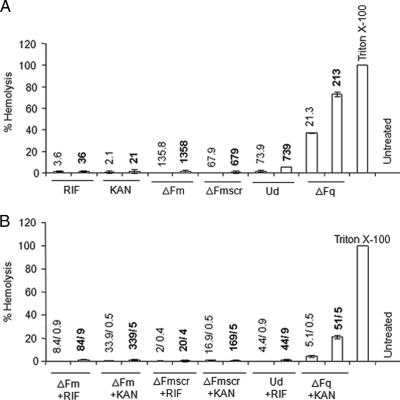

Toxicity to human cells is one of the known drawbacks of several antimicrobial peptides that have limited their use in the clinic (15). To study the effects of peptide and nonpeptide antibiotics used alone and in combination on mammalian cells, we studied their hemolytic potentials (Fig. 4) as well as their toxicities to HeLa and fibroblast cell lines (Fig. 5).

FIG. 4.

Hemolytic activities of peptide and nonpeptide antibiotics alone (A) and in combination (B) at MIC and 10× MIC. The values above the bars indicate the concentrations (MIC [lightface] and 10× MIC [boldface]) at which the antibiotics alone or in combination were studied. For the combinations, the concentrations are given as x/y, where x and y represent the concentrations (μg/ml) of peptide and nonpeptide antibiotics, respectively. Peptide and nonpeptide antibiotics were incubated with 0.4% RBCs in PBS. The results are expressed as percent hemolysis. RBCs incubated with 0.1% Triton X-100 were considered to be 100% lysed. The percent hemolysis was calculated as follows: [OD414 (antibiotic + RBCs) − OD414 (RBCs in PBS)]/[OD414 (RBCs in Triton X-100) − OD414 (RBCs in PBS)] × 100. RIF, rifampin; KAN, kanamycin. Standard deviations from three observations are plotted.

FIG. 5.

Mammalian-cell cytotoxicity (MTT assay) of peptide and nonpeptide antibiotics at MIC and 10× MIC alone and in combination against L929 (A) and HeLa (B) cell lines. Test samples (individual antibiotics or antibiotic mixtures) were incubated with cells for 24 h in RPMI 1640. Untreated cells served as the negative control. The values above the bars indicate the concentrations (MIC [lightface] and 10× MIC [boldface]) at which the antibiotics alone or in combination were studied. For the combinations, the concentrations are given as x/y, where x and y represent the concentrations of peptide and nonpeptide antibiotics, respectively. The ratio of OD570 for peptide-treated cells to OD570 for untreated cells was used to calculate the percent viability of cells. RIF, rifampin; KAN, kanamycin. Standard deviations from three observations are plotted.

To evaluate hemolysis, the antibiotics alone and in combination (at concentrations equal to MIC and 10× MIC) were incubated with RBCs and the release of hemoglobin (due to RBC lysis) was measured. The results showed that all antibiotics (peptide and nonpeptide) alone, except ΔFq, showed very low (≤5%) hemolysis. ΔFq is a potent antibiotic, with an MIC of 21.3 μg/ml (3.7 μM) against E. coli ML35p (Table 2); however, the lack of target specificity reflected in its high hemolytic potential (37% hemolysis at MIC and 70% at 10× MIC) (Fig. 4A) limits its clinical potential. All tested antibiotic combinations exhibited very low (≤5%) hemolysis (Fig. 4). This was particularly remarkable in the case of the highly hemolytic (37% hemolysis at MIC) ΔFq, which in combination with kanamycin kills bacteria with minimum (4%) hemolysis at an FIC index of 0.5. Even at 10× MIC, while ΔFq alone shows 75% hemolysis, the synergy combination of ΔFq with kanamycin shows only 21% hemolysis. Therefore, ΔFq in synergy with kanamycin exhibits not only a 4-fold increase in its antibiotic potency but also a 4-fold reduction in its hemolytic activity.

Mammalian-cell cytotoxicity was further assessed by analyzing the effects of the peptide and nonpeptide antibiotics, both alone and in combination, on HeLa cell and fibroblast lines. Cells were incubated with antibiotics alone and in combination at MIC and 10× MIC. Cell viability was determined by the MTT assay. The viability of antibiotic-treated cells was enumerated as the percent viability compared to the viability of cells incubated under identical conditions but in the absence of antibiotic(s). As shown in Fig. 5, at MIC, none of the peptide or nonpeptide antibiotics alone or in combination showed toxicity to HeLa cell or fibroblast lines. At 10× MIC, none of the peptides (except ΔFq) exhibited any cytotoxicity against HeLa cell or L929 fibroblast lines. However, it may be noted that kanamycin and rifampin alone (at 10× MIC) displayed substantial (∼40%) cytotoxicity against fibroblasts. At 10× MIC, while ΔFq alone was highly cytotoxic against both cell lines (∼60%), the combination of ΔFq and kanamycin was significantly less toxic to fibroblasts, with a 30% increase in the percentage of viable cells (from 40% viability with ΔFq alone to 70% viability in synergy with kanamycin). Unlike fibroblasts, HeLa cells exhibited a heightened cytotoxicity to 10× MIC of ΔFq both alone and in combination with kanamycin. The results suggest that the cytotoxicity profiles of even hemolytic and cytotoxic peptides like ΔFq can be improved by synergy with nonpeptide antibiotics.

DISCUSSION

One of the most obvious benefits of synergizing antibiotics is the lowering of the dosage of each molecule in the synergy combination. This is of particular importance in the case of antibacterial peptides, for which poor potency and the high expense of production have proven to be major hurdles for clinical development (15). Our study shows a significant improvement in MICs of peptides ΔFm, ΔFmscr, and Ud in synergistic combination with rifampin and kanamycin. Thus, synergy resulted in dramatic decreases in MICs for ΔFm (135.8 μg/ml [100 μM] to 8.4 μg/ml [6.2 μM]), ΔFmscr (67.9 μg/ml [50 μM] to 2 μg/ml [2 μM]), and Ud (73.9 μg/ml [30 μM] to 4.4 μg/ml [1.8 μM]) against E. coli. The power of synergy can be gauged from the fact that it enabled the utilization of even weakly antibacterial peptides, which in isolation would have been abandoned as poor antibiotics. That synergy influences the antibiotic potency of both partners in a peptide-nonpeptide antibiotic combination is apparent from the fact that, in the presence of the peptides, rifampin and kanamycin also showed a 4- to 8-fold improvement in potency (Table 2). Therefore, by decreasing the absolute amount of each agent in a drug combination, synergy makes therapy more cost-effective. Rifampin (a tetrahydroxy piperazinyl) and kanamycin (a carbohydrate) are chemically distinct (Fig. 1) classes of antibiotics which affect different processes like transcription (rifampin) and translation (kanamycin). The observed synergy of peptides with both rifampin and kanamycin suggests that antimicrobial peptides may show synergy with a diversity of antibiotics.

Synergy not only potentiates the bacteriostatic effect but can also improve bactericidal activity. In synergy with rifampin (0.4 μg/ml), the bactericidal potency of Ud improved from 369.9 μg/ml (150 μM) to 18.5 μg/ml (7.5 μM) (20-fold), making this a potent bactericidal combination (Fig. 2). In antimicrobial therapy, bactericidal drugs are preferred over bacteriostatic agents as they prevent the emergence of resistant mutants by killing the microorganism (27). Therefore, by increasing the bactericidal potency of antibacterial peptides we can reduce the chances of resistance to these antibiotics.

In addition to high potency, faster kinetics of bacterial killing is a useful attribute of an antibiotic. Antibiotics that display rapid kinetics of bacterial killing can potentially contain infection with greater rapidity. In this study, the synergy of kanamycin and ΔFmscr displayed not only a 4-fold improvement in potency (67.9 to 16.9 μg/ml) but also a kill kinetics 1 order of magnitude faster against E. coli (Fig. 3). In contrast to a mere inhibition of growth as late as 60 min when ΔFmscr was used alone, the combination was found to kill E. coli within its doubling time of 20 min. Thus, synergy can be used to enhance the kill kinetics of antibiotics. Synergy in potency (MIC and MBC) is likely to be seen when two components of the synergy combination target different niches in a cell. Vancomycin (bacterial cell wall synthesis inhibitor) is known to synergize with the aminoglycoside antibiotic gentamicin (translational inhibitor) against penicillin-resistant pneumococci. The mechanism underlying this synergy involves vancomycin-mediated enhanced entry of gentamicin into pneumococci (7). It is likely that in synergy combinations reported by us, the antimicrobial peptides enhance the rate and extent of permeabilization of rifampin or kanamycin. However, in view of the ability of antimicrobial peptides to penetrate bacterial cells (10), the presence of both antimicrobial peptides and rifampin or kanamycin in the cell can lead to several new avenues by which synergy in potency and kill kinetics as seen in our studies can be manifested.

Because the toxicity of a drug to the bystander host cells could render it unsuitable for therapeutic purposes, we assessed the possible hemolytic (Fig. 4) and cytotoxic (Fig. 5) effects of peptides alone and in combination with nonpeptide antibiotics. None of the peptides (except ΔFq) alone or in combination showed any significant hemolytic activity (Fig. 4). Although ΔFq is a potent antibacterial peptide (MIC of 21.3 μg/ml [3.7 μM]), it is highly hemolytic at its MIC (37% hemolysis) (Fig. 4A). Since the primary requirement of any drug is minimal toxicity to the host, we wanted to see whether the concentration (5.1 μg/ml) at which ΔFq exhibits synergy with kanamycin is below the threshold of hemolysis for this peptide. Indeed, as shown in Fig. 4B, ΔFq in synergy with kanamycin is not significantly hemolytic (4% hemolysis) and can be considered suitable for clinical use. Even at 10× MIC, the hemolytic activity of ΔFq is reduced ∼3-fold (from 70% alone to 21% in combination). The results suggest that it may be worthwhile to explore synergy as a means to reduce the hemolytic activity of potent antimicrobial peptides, like melittin, which are considered unsuitable for therapeutic use as they are very hemolytic (2, 16). Similarly, none of the peptide or nonpeptide antibiotics (alone or in synergy combinations) when tested at the respective MICs were cytotoxic against HeLa cells or fibroblasts (Fig. 5). In addition, the cytotoxic activity of ΔFq (at 10× MIC) against fibroblasts (40% viability) was significantly reduced (70% viability) when ΔFq was synergized with kanamycin (Fig. 5). The synergy combination of ΔFq and kanamycin seems to be selective in causing 70% toxicity to HeLa cells, versus ∼30% to fibroblasts. Since HeLa is a cancer cell line, it may be interesting to determine the finer molecular features of this selectivity and to assess whether such a combination would be useful in anticancer therapy. Taken together, the results show that synergy is an effective strategy to lower both the hemolytic and the cytotoxic effects of antibacterial peptides and to improve their therapeutic potential.

In summary, we have used synergy as a simple, quick, and effective strategy to enhance the activities and selectivities of four antimicrobial peptides without modifying them in any manner. The results obtained in this study emphasize the need to use synergy as a strategy to enhance the therapeutic potential of antibacterial peptides. Such a strategy can be extended to a wide range of antibacterial peptides to generate a higher number of strong candidates to treat life-threatening bacterial infections.

Acknowledgments

A research fellowship from the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, Government of India, to A.A. is acknowledged. This research was supported by grant BT/PR3325/BRB/10/283/2002 to D.S. from the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India.

The gift of E. coli ML35p from Liam Good, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden, is gratefully acknowledged. We thank Pooja Chetal Dewan for the synthesis and purification of ΔFq and Dinesh Mohanakrishnan for assistance with the MTT assay.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 February 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmad, A., S. P. Yadav, N. Asthana, K. Mitra, S. P. Srivastava, and J. K. Ghosh. 2006. Utilization of an amphipathic leucine zipper sequence to design antibacterial peptides with simultaneous modulation of toxic activity against human red blood cells. J. Biol. Chem. 281:22029-22038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asthana, N., S. P. Yadav, and J. K. Ghosh. 2004. Dissection of antibacterial and toxic activity of melittin. J. Biol. Chem. 279:55042-55050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barriere, S. L. 1992. Bacterial resistance to beta-lactams and its prevention with combination antimicrobial therapy. Pharmacotherapy 12:397-402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brogden, K. A. 2005. Antimicrobial peptides: pore formers or metabolic inhibitors in bacteria? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:238-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bulet, P., R. Stocklin, and L. Menin. 2004. Anti-microbial peptides: from invertebrates to vertebrates. Immunol. Rev. 198:169-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chu-Kung, A. F., K. N. Bozzelli, N. A. Lockwood, J. R. Haseman, K. H. Mayo, and M. V. Tirrell. 2004. Promotion of peptide antimicrobial activity by fatty acid conjugation. Bioconjug. Chem. 15:530-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cottagnoud, P., M. Cottagnoud, and M. G. Täuber. 2003. Vancomycin acts synergistically with gentamicin against penicillin-resistant pneumococci by increasing the intracellular penetration of gentamicin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:144-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darveau, R. P., M. D. Cunningham, C. L. Seachord, L. C. Clough, W. L. Cosand, J. Blake, and C. S. Watkins. 1991. Beta-lactam antibiotics potentiate magainin 2 antimicrobial activity in vitro and in vivo. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:1153-1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dathe, M., T. Wieprecht, H. Nikolenko, L. Handel, W. L. Maloy, D. L. MacDonald, D. L. Beyermann, and M. Bienert. 1997. Hydrophobicity, hydrophobic moment and angle subtended by charged residues modulate antibacterial and hemolytic activity of amphipathic helical peptides. FEBS Lett. 403:208-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dewan, P. C., A. Anantharaman, V. S. Chauhan, and D. Sahal. 2009. Antimicrobial action of prototypic amphipathic cationic decapeptides and their branched dimers. Biochemistry 48:5642-5657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fehri, L. F., H. Wro′blewski, and A. Blanchard. 2007. Activities of antimicrobial peptides and synergy with enrofloxacin against Mycoplasma pulmonis. Antimicrob. Agent Chemother. 51:468-474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giangaspero, A., L. Sandri, and A. Tossi. 2001. Amphipathic alpha helical antimicrobial peptides. A systematic study of the effects of structural and physical properties on biological activity. Eur. J. Biochem. 268:5589-5600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hale, J. D. F., and R. E. W. Hancock. 2007. Alternative mechanisms of action of cationic antimicrobial peptides on bacteria. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 5:951-959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hancock, R. E. W., and D. S. Chapple. 1999. Peptide antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1317-1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hancock, R. E. W., and H. Sahl. 2006. Antimicrobial and host defense peptides as new anti-infective therapeutic strategies. Nat. Biotechnol. 24:1551-1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Juvvadi, P., S. Vunnam, and R. B. Merrifield. 1996. Synthetic melittin, its enantio, retro, and retroenantio isomers, and selected chimeric analogs: their antibacterial, hemolytic, and lipid bilayer action. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118:8989-8997. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaiser, E., R. L. Colescott, C. D. Bossinger, and P. I. Cook. 1970. Color test for detection of free terminal amino groups in the solid-phase synthesis of peptides. Anal. Biochem. 34:595-598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kondejewskii, L. H., M. J. Niaraki, S. W. Farmer, B. Lix, C. M. Kay, B. D. Sykes, R. E. W. Hancock, and R. S. Hodges. 1999. Dissociation of antimicrobial and hemolytic activities in cyclic peptide diastereomers by systematic alterations in amphipathicity. J. Biol. Chem. 274:13181-13192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Makovitzki, A., D. Avrahami, and Y. Shai. 2006. Ultrashort antibacterial and antifungal lipopeptides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:15997-16002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCafferty, D. G., P. Cudic, M. K. Yu, D. C. Behenna, and R. Kruger. 1999. Synergy and duality in peptide antibiotic mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 3:672-680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park, Y., H. J. Kim, and K. Hahm. 2004. Antibacterial synergism of novel antibiotic peptides with chloramphenicol. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 321:109-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Puius, Y. A., T. H. Stievater, and T. Srikrishnan. 2006. Crystal structure, conformation and absolute configuration of kanamycin A. Carbohydr. Res. 341:2871-2875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Radzishevsky, I. S., S. Rotem, D. Bourdetsky, S. Navon-Venezia, Y. Carmeli, and A. Mor. 2007. Improved antimicrobial peptides based on acyl-lysine oligomers. Nat. Biotechnol. 25:657-659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramagopal, U. A., S. Ramakumar, D. Sahal, and V. S. Chauhan. 2001. De novo design and characterization of an apolar helical hairpin peptide at atomic resolution: compaction mediated by weak interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:870-874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rand, K. H., and H. J. Houck. 2004. Daptomycin synergy with rifampicin and ampicillin against vancomycin-resistant enterococci. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 53:530-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steinberg, D. A., M. A. Hurst, C. A. Fujii, A. H. C. Kung, J. F. Ho, F. C. Cheng, D. J. Loury, and J. C. Fiddes. 1997. Protegrin-1: a broad-spectrum, rapidly microbicidal peptide with in vivo activity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:1738-1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stratton, C. W. 2003. Dead bugs don't mutate: susceptibility issues in the emergence of bacterial resistance. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9:10-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tenecza, S. B., D. J. Creighton, T. Yuan, H. J. Vogel, R. C. Montelaro, and T. A. Meitzner. 1999. Lentivirus-derived antimicrobial peptides: increased potency by sequence engineering and dimerization. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 44:33-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu, Y. L., E. M. Scott, A. L. W. Po, and V. N. Tariq. 1999. Ability of azlocillin and tobramycin in combination to delay or prevent resistance development in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 44:389-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yan, H., and R. E. W. Hancock. 2001. Synergistic interactions between mammalian antimicrobial defense peptides. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1558-1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yeaman, M. R., and N. Y. Yount. 2003. Mechanisms of antimicrobial peptide action and resistance. Pharmacol. Rev. 55:27-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zasloff, M. 2002. Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature 415:389-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]