Abstract

Streptomyces lydicus NRRL2433 and S. spectabilis NRRL2494 produce two inhibitors of bacterial RNA polymerase: the 3-acyltetramic acid streptolydigin and the naphthalenic ansamycin streptovaricin, respectively. Both strains are highly resistant to their own antibiotics. Independent expression of the S. lydicus and S. spectabilis rpoB and rpoC genes, encoding the β- and β′-subunits of RNA polymerase, respectively, in S. albus showed that resistance is mediated by rpoB, with no effect of rpoC. Within the β-subunit, resistance was confined to an amino acid region harboring the “rif region.” Comparison of the β-subunit amino acid sequences of this region from the producer strains and those of other streptomycetes and site-directed mutagenesis of specific differential residues located in it (L485 and D486 in S. lydicus and N474 and S475 in S. spectabilis) showed their involvement in streptolydigin and streptovaricin resistance. Other amino acids located close to the “Stl pocket” in the S. lydicus β-subunit (L555, F593, and M594) were also found to exert influence on streptolydigin resistance.

Actinomycetes (particularly streptomycetes) are producers of approximately three quarters of all known antibiotics. This prolific group of Gram-positive, mycelial, sporulating bacteria has developed specific resistance mechanisms through evolution to facilitate survival during production of the potentially toxic compounds (10, 11, 24). Interestingly, many of the resistance mechanisms found in producer organisms have homologues in clinically isolated bacteria. This has raised a question about the origin of antibiotic resistance determinants found in bacteria, with an early proposition that producing organisms might represent the source of (at least some of) the resistance determinants commonly encountered in clinical isolates (4). Among these resistance mechanisms, modification of the antibiotic target site is a quite frequent and efficient resistance mechanism in producing organisms, and it has been reported for producers of inhibitors of ribosomal function, DNA gyrase, elongation factor EF-Tu, and fatty acid synthase (11).

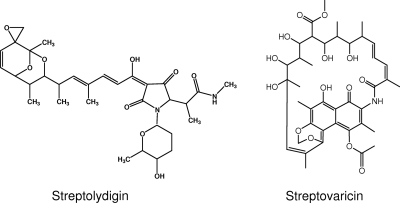

There are a number of RNA polymerase (RNAP) inhibitors produced by actinomycetes. Streptolydigin (Fig. 1) is a 3-acyltetramic acid antibiotic which specifically inhibits bacterial DNA-dependent RNA polymerase (8, 12, 23, 33). Streptovaricin (Fig. 1) is a naphthalenic ansamycin similar to rifampin (34). They exert their inhibition basically through interaction with the β-subunit of RNAP, but the defined mechanisms of action are different. Rifampin and streptovaricin likely share the same transcription inhibition mechanism (39), which occurs at the promoter and has no effect on RNAP once it has elongated past the promoter (7). On the other hand, streptolydigin blocks transcription immediately upon addition, causing the inhibition of elongation of nascent mRNAs (8, 23). Mutations conferring resistance to rifampin and streptolydigin are usually located in the rpoB gene (encoding the β-subunit), although some mutations in rpoC (encoding the β′-subunit) can also confer streptolydigin resistance in Escherichia coli (13, 32) and Bacillus subtilis (40). Interestingly, streptolydigin exhibits only limited cross-resistance with streptovaricin and rifampin (6) and no cross-resistance with other inhibitors of RNAP, such as microcin J25 (1, 41) and sorangicin (7).

FIG. 1.

Structures of streptolydigin and streptovaricin.

Within our studies on antibiotic biosynthesis and resistance in antibiotic-producing actinomycetes, we were interested in the characterization of the self-resistance mechanisms in the producer organisms of these two RNA polymerase inhibitors and, particularly, in the role of different mutations on the RNA polymerase. Both producer strains have been shown to possess an RNAP resistant to the produced antibiotic (5). The recent cloning and sequencing of the streptolydigin gene cluster (26) showed that no RNAP subunit-encoding gene was present within the streptolydigin gene cluster. Here we report a detailed molecular analysis of the Streptomyces lydicus (streptolydigin producer) and Streptomyces spectabilis (streptovaricin producer) rpoB genes, proofs supporting their involvement in resistance, and the identification of amino acid residues in the β-subunit responsible for self-resistance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, culture conditions, and plasmids.

Streptomyces lydicus NRRL2433 and Streptomyces spectabilis NRRL2494 were used as streptolydigin and streptovaricin producers and as donors for chromosomal DNA. Streptomyces albus J1074 (9), a streptolydigin- and streptovaricin-sensitive strain, was used as a recipient host in conjugation experiments, for heterologous expression of RNA polymerase subunits, and in bioassays. E. coli DH10B (Gibco) was used as a subcloning host, and E. coli ET12567(pUB307) (20) was used as a donor for intergeneric conjugation. For growth in liquid medium, microorganisms were cultured in Trypticase soy broth (TSB; Oxoid). For sporulation and bioassays in solid medium, Streptomyces strains were cultured at 30°C on Bennet's agar plates (20). When needed, antibiotics (Sigma) were added at the following concentrations: 5 or 25 μg/ml thiostrepton for liquid or solid medium, respectively; 25 μg/ml kanamycin; 25 μg/ml chloramphenicol; 25 μg/ml nalidixic acid; and 100 μg/ml ampicillin. pUK21 (37) was used as an E. coli cloning vector, and pEM4T (25) was used for E. coli-Streptomyces intergeneric conjugation and heterologous expression.

DNA manipulation, sequencing, and analysis.

Total DNA isolation, plasmid DNA preparations, restriction endonuclease digestions, ligations, alkaline phosphatase treatment, and other DNA manipulations were performed according to standard procedures for E. coli (29) and for Streptomyces (20). Intergeneric conjugation from E. coli ET12567(pUB307) into S. albus was performed as previously described (20). DNA sequencing was performed on double-stranded DNA templates by the dideoxynucleotide chain termination method (30) and by use of a Cy5 Autocycle sequencing kit (GE Healthcare), using an Alf-Express automatic DNA sequencer (GE Healthcare). Computer-assisted database searching and sequence analyses were performed using the BLAST program (2) and the Vector NTI sequence analysis software package (Invitrogen). PCRs were performed using Platinum Pfx DNA polymerase (Invitrogen), and several PCR products were sequenced.

Cloning of rpoB and rpoC.

Both rpoB and rpoC from S. lydicus and S. spectabilis and rpoB from S. albus were PCR amplified using the oligonucleotides described in Table 1. The amplification products were cloned into pUK21 (pUK21-Lβ, pUK21-Lβ′, pUK21-Sβ, pUK21-Sβ′, and pUK21-Aβ constructs) (Table 2) and sequenced. A blunt-ended SpeI fragment was rescued from these constructs and cloned under the control of the ermE* promoter into blunt-ended EcoRI-digested pEM4T, generating pEM4T-Lβ, pEM4T-Lβ′, pEM4T-SLβ, pEM4T-SLβ′, and pEM4T-Aβ (Table 2). These constructs were independently introduced by conjugation from E. coli into S. albus.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used for PCR amplification, site-directed mutagenesis, and chimeric RpoB construction

| Oligonucleotide name and purpose | Sequence (5′→3′)a | Tm (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| Primers for RpoB and RpoC subunit amplification | ||

| RpoB_fw | ACGTAAGCTTATCCAGGTCATCAAGGTCG | 78 |

| RpoB_rev | ACGTTCTAGAAGATCTTCTCGCAGAAGAG | 77 |

| RpoC_fw | ACGTAAGCTTGTGCTCGACGTCAACTTCT | 73.3 |

| RpoC3_rev | ACGTTCTAGATTACTGGTTGTACGGACCG | 70.6 |

| Primers for site-directed mutagenesis | ||

| 2433_T458N_fw | AGTTCATGGACCAGAACAACCCGCTGTCGGG | 80.31 |

| 2433_T458N_rev | CCCGACAGCGGGTTGTTCTGGTCCATGAACT | 80.31 |

| 2433_A636S_fw | TTCCGCTGATCAAGTCGGAGTCGCCGCTGGTC | 82.91 |

| 2433_A636S_rev | GACCAGCGGCGACTCCGACTTGATCAGCGGAA | 82.91 |

| 2433_D486E_fw | GCGGGCCGGCCTGGAGGTCCGTGACGTGCAC | 88.25 |

| 2433_D486E_rev | GTGCACGTCACGGACCTCCAGGCCGGCCCGC | 88.25 |

| 2433_L555V_fw | AGGAGGACCGCTTCGTGATCGCGCAGGCCAAC | 84.19 |

| 2433_L555V_rev | GTTGGCCTGCGCGATCACGAAGCGGTCCTCCT | 84.19 |

| 2433_F593Y_fw | GCCGACGAGGTGGACTACATGGACGTCTCGCCG | 85.35 |

| 2433_F593Y_rev | CGGCGAGACGTCCATGTAGTCCACCTCGTCGGC | 85.35 |

| 2433_S624A_fw | CGCGCGCTCATGGGAGCGAACATGATGCGCC | 84.28 |

| 2433_S624A_rev | GGCGCATCATGTTCGCTCCCATGAGCGCGCG | 84.28 |

| 2433_L485F_fw | TGAGCGGGCCGGCTTCGACGTCCGTGACGTG | 87.60 |

| 2433_L485F_rev | CACGTCACGGACGTCGAAGCCGGCCCGCTCA | 87.60 |

| 2433_LD485FE_fw | TGAGCGGGCCGGCTTCGAGGTCCGTGACGTGC | 83.70 |

| 2433_LD485FE_rev | GCACGTCACGGACCTCGAAGCCGGCCCGCTCA | 83.70 |

| 2494_I467L_fw | CCCGCTGCTGGGCCTCACCCACAAGCGGCGTC | 83.7 |

| 2494_I467L_rev | GACGCCGCTTGTGGGTGAGGCCCAGCAGCGGG | 83.7 |

| 2494_N474S_fw | CACAAGCGGCGTCTGAGCTCGCTCGGCCCGGGT | 91.3 |

| 2494_N474S_rev | ACCCGGGCCGAGCGAGCTCAGACGCCGCTTGTG | 91.3 |

| 2494_S475A_fw | AGCGGCGTCTGAACGCGCTCGGCCCGGGTGG | 85.0 |

| 2494_S475A_rev | CCACCCGGGCCGAGCGCGTTCAGACGCCGCT | 85.0 |

| 2494_T638K_fw | CCGTGCCGCTGATCAAGGCCGAGGCCCCCCTCG | 92.5 |

| 2494_T638K_rev | CGAGGGGGGCCTCGGCCTTGATCAGCGGCACGG | 92.5 |

| 2494_A639S_fw | TGCCGCTGATCACCTCCGAGGCCCCCCTCGTC | 81.8 |

| 2494_A639S_rev | GACGAGGGGGGCCTCGGAGGTGATCAGCGGCA | 81.8 |

| 2494_NS474SA_fw | CAAGCGGCGTCTGACGGCGCTCGGCCCGGGTG | 86.2 |

| 2494_NS474SA_rev | CACCCGGGCCGAGCGCCGTCAGACGCCGCTTG | 86.2 |

| SA_L463I_fw | CCCGCTCTCGGGAATCACCCACAAGCGCCGTC | 80.6 |

| SA_L463I_rev | GACGGCGCTTGTGGGTGATTCCCGAGAGCGGG | 80.6 |

| SA_S470N_fw | CACAAGCGCCGTCTGAACG CGCTCGGCCCGG | 91.8 |

| SA_S470N_rev | CCGGGCCGAGCGCGTTCAGACGGCGCTTGTG | 91.8 |

| SA_A471S_fw | AGCGCCGTCTGTCGTCGCTCGGCCCGGGTG | 91.3 |

| SA_A471S_rev | CACCCGGGCCGAGCGACGACAGACGGCGCT | 91.3 |

| SA_F484L_fw | CGTGAGCGGGCCGGCCTCGAGGTCCGTGACGT | 88.03 |

| SA_F484L_rev | ACGTCACGGACCTCGAGGCCGGCCCGCTCACG | 88.03 |

| SA_E485D_fw | AGCGGGCCGGCTTCGACGTCCGTGACGTGCAC | 86.75 |

| SA_E485D_rev | GTGCACGTCACGGACGTCGAAGCCGGCCCGCT | 86.75 |

| SA_FE485LD_fw | TGAGCGGGCCGGCCTCGACGTCCGTGACGTGC | 78.66 |

| SA_FE485LD_rev | GCACGTCACGGACGTCGAGGCCGGCCCGCTCA | 78.66 |

| SA_SA470NS_fw | CAAGCGCCGTCTGAACTCGCTCGGCCCGGGTG | 82.4 |

| SA_SA470NS_rev | CACCCGGGCCGAGCGAGTTCAGACGGCGCTTG | 82.4 |

| Primers for chimeric RpoB construction | ||

| NheSA_fw | ATCCGGCCGGTCGTCGCTAGCATCAAGGAGTTCTTC | 78.33 |

| NheSA_rev | GAAGAACTCCTTGATGCTAGCGACGACCGGCCGGAT | 78.33 |

| BspTISA_fw | ACGCCGGCGACGTGCTTAAGGCGGAGAAGGACGGTG | 87.31 |

| BspTISA_rev | ACCGTCCTTCTCCGCCTTAAGCACGTCGCCGGCGTC | 87.31 |

| Nhe_fw | CAGGTCGCTAGCATCAAGGAGTTCTTCG | 61 |

| BspTI_rev | CTCGGCCTTAAGGACGTCACCGGCGTCG | 70 |

Introduced mutations are underlined.

TABLE 2.

Plasmids constructed in this work

| Plasmid | Characteristic(s) |

|---|---|

| pUK21-Lβ | S. lydicus rpoB gene cloned in pUK21 |

| pUK21-Lβ ′ | S. lydicus rpoC gene cloned in pUK21 |

| pUK21-Sβ | S. spectabilis rpoB gene cloned in pUK21 |

| pUK21-Sβ ′ | S. spectabilis rpoC gene cloned in pUK21 |

| pUK21-Aβ | S. albus rpoB gene cloned in pUK21 |

| pUK21-CALβ | Chimeric S. lydicus rpoB gene cloned in pUK21 |

| pUK21-CASβ | Chimeric S. spectabilis rpoB gene cloned in pUK21 |

| pEM4T-Lβ | S. lydicus rpoB gene cloned in pEM4T |

| pEM4T-Lβ ′ | S. lydicus rpoC gene cloned in pEM4T |

| pEM4T-Lβ100 | pEM4T-Lβ containing T458N mutation |

| pEM4T-Lβ101 | pEM4T-Lβ containing L485F mutation |

| pEM4T-Lβ102 | pEM4T-Lβ containing D486E mutation |

| pEM4T-Lβ103 | pEM4T-Lβ containing L555V mutation |

| pEM4T-Lβ104 | pEM4T-Lβ containing F593Y mutation |

| pEM4T-Lβ105 | pEM4T-Lβ containing S624A mutation |

| pEM4T-Lβ106 | pEM4T-Lβ containing A636S mutation |

| pEM4T-Lβ107 | pEM4T-Lβ containing L485F and D486E mutations |

| pEM4T-Lβ108 | pEM4T-Lβ containing F593Y and M594L mutations |

| pEM4T-Sβ | S. spectabilis rpoB gene cloned in pEM4T |

| pEM4T-Sβ ′ | S. spectabilis rpoC gene cloned in pEM4T |

| pEM4T-Sβ100 | pEM4T-Sβ containing I467L mutation |

| pEM4T-Sβ101 | pEM4T-Sβ containing N474S mutation |

| pEM4T-Sβ102 | pEM4T-Sβ containing S475A mutation |

| pEM4T-Sβ103 | pEM4T-Sβ containing T638K mutation |

| pEM4T-Sβ104 | pEM4T-Sβ containing A639S mutation |

| pEM4T-Sβ105 | pEM4T-Sβ containing N474S and S475A mutations |

| pEM4T-Aβ | S. albus rpoB gene cloned in pEM4T |

| pEM4T-Aβ201 | pEM4T-Aβ containing F484L mutation |

| pEM4T-Aβ202 | pEM4T-Aβ containing E485D mutation |

| pEM4T-Aβ203 | pEM4T-Aβ containing F484L and E485D mutations |

| pEM4T-Aβ204 | pEM4T-Aβ containing L463I mutation |

| pEM4T-Aβ205 | pEM4T-Aβ containing S470N mutation |

| pEM4T-Aβ206 | pEM4T-Aβ containing A471S mutation |

| pEM4T-Aβ207 | pEM4T-Aβ containing S470N and A471S mutations |

| pEM4T-CALβ | Chimeric S. lydicus rpoB gene cloned in pEM4T |

| pEM4T-CASβ | Chimeric S. spectabilis rpoB gene cloned in pEM4T |

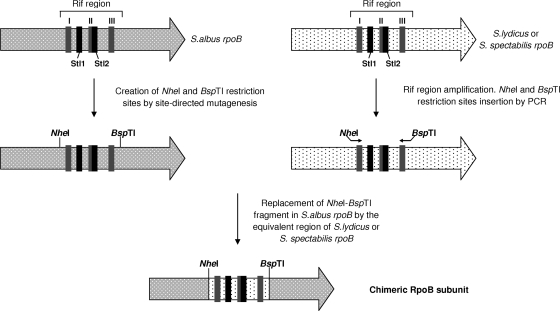

Chimeric RpoB subunit constructs.

Two chimeric rpoB genes were constructed by replacing the rif region of the S. albus rpoB gene (amino acids 435 to 534) with the corresponding region from the S. lydicus rpoB gene (amino acids 470 to 569) or the S. spectabilis rpoB gene (amino acids 443 to 661) (see Fig. 3). Four primers (Table 1) were used to introduce two unique restriction sites (NheI and BspTI sites) flanking the rif region in pUK21-Aβ by site-directed mutagenesis. Two additional oligonucleotides carrying NheI and BspTI restriction sites (Table 1) were used to amplify the rif region, using pUK21-Lβ and pUK21-Sβ as templates. The PCR product was digested with NheI and BspTI and cloned into mutagenized pUK21-Aβ, previously digested with the same enzymes. Each chimeric rpoB gene was cloned as a blunt-ended SpeI fragment into blunt-ended EcoRI-digested pEM4T, generating pEM4T-CLAβ and pEM4T-CSAβ, and then these constructs were transferred to S. albus by conjugation.

FIG. 3.

Scheme representing the construction of chimeric RpoB subunits.

Site-directed mutagenesis of rpoB.

Site-directed mutagenesis was carried out using a QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). As templates, pUK21-Lβ, pUK21-Sβ, and pUK21-Aβ constructs were used, and oligonucleotides were designed to introduce changes in specific amino acids (Table 1). Mutagenesis was verified by DNA sequencing, and the SpeI fragment containing the mutagenized gene was cloned into pEM4T. The new plasmids (pEM4T-Lβ, pEM4T-Sβ, and pEM4T-Aβ derivatives) (Table 2) were independently introduced by conjugation from E. coli into S. albus.

Determination of MIC.

Using a plate replicator, spore suspensions of the different strains were replica plated on 25-ml Bennet's agar plates containing different concentrations of streptolydigin and streptovaricin, and the plates were incubated for 5 to 7 days at 30°C. The MIC was defined as the minimal streptolydigin or streptovaricin concentration that completely inhibited growth.

Homology modeling.

Searches for sequences similar to those of S. lydicus and S. spectabilis RpoB and RpoC subunits were performed with the BLAST program (2). Sequences were aligned and manually adjusted using the Swiss-Model server (3), and a three-dimensional model was built and energy minimized. Models were validated using the Procheck and Whatcheck programs, available from the Joint Center for Structural Genomics (14, 21; http://www.jcsg.org/prod/scripts/validation/sv_final.cgi).

RESULTS

Self-resistance in streptolydigin and streptovaricin producer organisms.

As a first step in this study, we determined the susceptibility to streptolydigin of the producer strain S. lydicus NRRL2433, the susceptibility to streptovaricin of the producer strain S. spectabilis NRRL2494, and the susceptibility to both antibiotics of the strain to be used as a host for gene expression, S. albus J1074, by cultivating the strains in solid agar medium in the presence of different concentrations of the drugs. In agreement with previous reports (5), the streptolydigin producer was highly resistant to its own produced antibiotic (MIC > 200 μg/ml), while growth of S. albus was inhibited by a concentration of only 1 μg/ml (Table 3). On the other hand, the streptovaricin producer was also highly resistant to streptovaricin (MIC > 200 μg/ml), while S. albus was sensitive to a concentration of 70 μg/ml (Table 4).

TABLE 3.

MICs of streptolydigin against S. lydicus NRRL2433 and S. albus transconjugants containing different mutagenized and nonmutagenized β- and β′ subunits

| Strain | Plasmid | Amino acid substitution(s) | MIC (μg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. lydicus NRRL 2433 | >200 | ||

| S. albus J1074 | 1 | ||

| S. albus(pEM4T) | pEM4T | 1 | |

| S. albus Aβ | pEM4T-Aβ | 1 | |

| S. albus Lβ | pEM4T-Lβ | 20 | |

| S. albus Lβ′ | pEM4T-Lβ′ | 1 | |

| S. albus CALβ | pEM4T-CALβ | 20 | |

| S. albus Lβ100 | pEM4T-Lβ100 | T458N | 20 |

| S. albus Lβ101 | pEM4T-Lβ101 | L485F | 1 |

| S. albus Lβ102 | pEM4T-Lβ102 | D486E | 10 |

| S. albus Lβ103 | pEM4T-Lβ103 | L555V | 1 |

| S. albus Lβ104 | pEM4T-Lβ104 | F593Y | 10 |

| S. albus Lβ105 | pEM4T-Lβ105 | S624A | 20 |

| S. albus Lβ106 | pEM4T-Lβ106 | A636S | 10 |

| S. albus Lβ107 | pEM4T-Lβ107 | L485F/D486E | 1 |

| S. albus Lβ108 | pEM4T-Lβ108 | F593Y/M594L | 1 |

| S. albus Aβ201 | pEM4T-Aβ201 | F484L | 6 |

| S. albus Aβ202 | pEM4T-Aβ202 | E485D | 1 |

| S. albus Aβ203 | pEM4T-Aβ203 | F484L/E485D | 9 |

TABLE 4.

MICs of streptovaricin (STV) and rifampin (RIF) against S. spectabilis NRRL2494 and S. albus transconjugants containing different mutagenized and nonmutagenized β- and β′-subunits

| Strain | Plasmid | Amino acid substitution(s) | STV MIC (μg/ml) | RIF MIC (μg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. spectabilis NRRL 2494 | >200 | >40 | ||

| S. albus J1074 | 70 | 5 | ||

| S. albus(pEM4T) | pEM4T | 70 | 5 | |

| S. albus Aβ | pEM4T-Aβ | 70 | 5 | |

| S. albus Sβ | pEM4T-Sβ | 200 | 40 | |

| S. albus Sβ′ | pEM4T-Sβ′ | 70 | 5 | |

| S. albus CASβ | pEM4T-CASβ | 200 | 40 | |

| S. albus Sβ100 | pEM4T-Sβ100 | I467L | 200 | 40 |

| S. albus Sβ101 | pEM4T-Sβ101 | N474S | 200 | 5 |

| S. albus Sβ102 | pEM4T-Sβ102 | S475A | 200 | 40 |

| S. albus Sβ103 | pEM4T-Sβ103 | T638K | 200 | 20 |

| S. albus Sβ104 | pEM4T-Sβ104 | A639S | 200 | 40 |

| S. albus Sβ105 | pEM4T-Sβ105 | N474S/S475A | 70 | 5 |

| S. albus Aβ204 | pEM4T-Aβ204 | L463I | 70 | 5 |

| S. albus Aβ205 | pEM4T-Aβ205 | S470N | 80 | 5 |

| S. albus Aβ206 | pEM4T-Aβ206 | A471S | 80 | 5 |

| S. albus Aβ207 | pEM4T-Aβ207 | S470N/A471S | 200 | 40 |

The rpoB genes of S. lydicus and S. spectabilis confer resistance to streptolydigin and streptovaricin, respectively.

Different reports showed that resistance to streptolydigin and streptovaricin in several bacteria is based mainly on mutations located in the β-subunit of RNAP (13, 27, 31, 39), but some reports also pointed to some mutations in the β′-subunit in E. coli (32). We therefore decided to verify if streptolydigin and streptovaricin resistance in the respective producer organisms was due to either or both of the β- and β′-subunits. We independently amplified rpoB and rpoC from S. lydicus and S. spectabilis and cloned them into the conjugative vector pEM4T, and the resulting constructs (pEM4T-Lβ, pEM4T-Lβ′, pEM4T-Sβ and pEM4T-Sβ′) were transferred to S. albus by conjugation. Susceptibility of different isolates to streptolydigin or streptovaricin was determined on Bennet agar plates containing different concentrations of the drugs (Tables 3 and 4). Recombinant strains harboring S. lydicus or S. spectabilis rpoB (named S. albus Lβ and S. albus Sβ, respectively) showed high levels of resistance to streptolydigin (20 μg/ml) or streptovaricin (200 μg/ml), while those harboring S. lydicus or S. spectabilis rpoC (S. albus Lβ′ and S. albus Sβ′) showed the same levels of sensitivity as the control harboring only the vector. These results suggest that resistance to streptolydigin in S. lydicus and to streptovaricin in S. spectabilis is mostly (if not exclusively) provided by the β-subunit, with a negligible contribution of the β′-subunit.

Sequencing of the genome of Nocardia farcinica IFM10152 has shown the existence of two genes for the β-subunit of RNAP (16), one of which, rpoB2, confers resistance to rifampin, while the other, rpoB, does not (17). A similar situation has been reported for Nonomuraea sp. (38). We wondered if two different rpoB genes could also coexist in S. lydicus and S. spectabilis. However, after extensive analysis by Southern hybridization and PCR amplifications, we always arrived at the detection of a single rpoB gene, corresponding to the one later characterized by DNA sequencing in this work. Furthermore, the streptolydigin gene cluster was recently isolated and characterized in our laboratory (26), and no resistance gene was found in the cluster affecting target modification (i.e., rpoB resistance gene or inactivating/modifying enzyme gene).

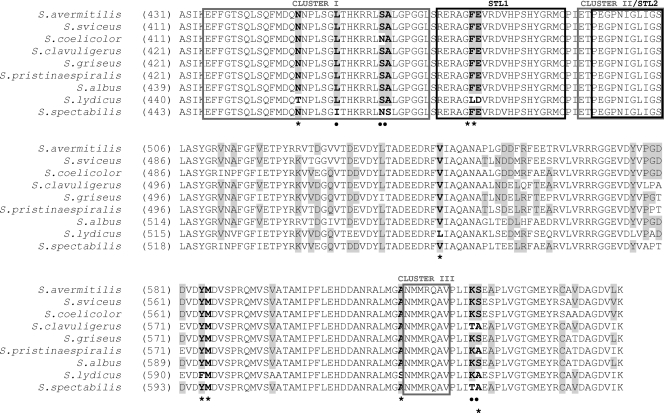

Streptolydigin resistance is located in a region of the β-subunit containing the Stl1 and Stl2 motifs.

Mutations in rpoB in different bacteria conferring resistance to either streptovaricin (and rifampin) or streptolydigin are usually located in an approximately 200-amino-acid region named the “rif region.” In this region, mutations conferring resistance to rifampin are located in the so-called clusters I, II, and III (18, 31), and those conferring resistance to streptolydigin are in the Stl1 loop (between clusters I and II) and the Stl2 loop (mostly overlapping with cluster II) (35, 36) (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Sequence alignments of RpoB rif regions from S. lydicus, S. spectabilis, and other Streptomyces strains. Rifampin resistance clusters (I, II, and III) and streptolydigin resistance motifs (Stl1 and Stl2) are indicated. Asterisks and circles indicate mutagenized residues in S. lydicus and S. spectabilis rpoB, respectively.

We sequenced rpoB genes from S. lydicus, S. spectabilis, and S. albus and compared their sequences with those of other Streptomyces β-subunits. From these comparisons, we decided to construct chimeric β-subunits in S. albus by exchanging a 657-bp region containing the “rif region” in S. albus rpoB for the analogous region from S. lydicus or S. spectabilis rpoB (Fig. 3). The resulting chimeric plasmids (pEM4T-CLAβ and pEM4T-CSAβ) were transferred to S. albus by conjugation. S. albus transconjugants (strains S. albus CLAβ and S. albus CSAβ) displayed MICs of 20 μg/ml (against streptolydigin) and 200 μg/ml (against streptovaricin). These results demonstrated that the S. lydicus and S. spectabilis cloned DNA fragments containing the “rif region” were responsible for streptolydigin and streptovaricin resistance, respectively.

Site-directed mutagenesis of S. lydicus rpoB.

A detailed analysis of the amino acids in the Stl1 and Stl2 domains of the “Stl pocket” and the adjacent regions showed some differences between different Streptomyces strains (Fig. 2). The Stl1 domains were identical for all Streptomyces rpoB gene products analyzed, with the exception of two consecutive residues, leucine (L485) and aspartic acid (D486), which were encoded in S. lydicus rpoB, while all other streptomycetes showed phenylalanine (F) and glutamic acid (E) residues at these positions (Fig. 2). No amino acid differences were found when the Stl2 domains were compared. To test if these two amino acids in Stl1 were important for streptolydigin resistance in S. lydicus, we performed site-directed mutagenesis experiments. S. lydicus rpoB codons encoding L485 and D486 were independently and simultaneously replaced by those for amino acids present at the same position in S. albus, creating L485F, D486E, and L485F/D486E mutations. Single substitution at L485 completely abolished streptolydigin resistance (MIC, 1 μg/ml) (Table 3), and substitution at D486 caused an important decrease in streptolydigin resistance (MIC, 10 μg/ml). In addition, double replacement of the LD pair with FE also greatly diminished the levels of resistance to those similar to the control level (MIC, 1 μg/ml). These results strongly suggest that residues L485 and D486 encoded by S. lydicus rpoB are important for streptolydigin resistance.

To verify if changing these residues was sufficient to confer resistance to streptolydigin, we carried out site-directed mutagenesis in the other direction, i.e., trying to make S. albus resistant to streptolydigin. We mutagenized the FE residues encoded by S. albus rpoB into LD amino acids, in both single and double substitutions, creating F484L, E485D, and F484L/E485D mutations. The E485D change did not cause an increase in streptolydigin resistance (MIC, 1 μg/ml). However, the F484L modification caused an increase compared to the control level (MIC, 6 μg/ml), and the double mutation (F484L/E485D) produced a higher increase in the level of resistance (MIC, 9 μg/ml).

The above-mentioned results prompted us to determine if some other amino acids in the S. lydicus β-subunit also contributed to streptolydigin resistance. We selected some amino acids outside the “Stl pocket” (but located within the “rif region” subcloned into pEM4T-Cβ) that were present in the S. lydicus β-subunit and different in the other streptomycete β-subunits analyzed, creating L555V, F593Y, F593Y/M594L, S624A, T458N, and A636S mutations. Two of them, L555V and F593Y/M594L, greatly affected streptolydigin resistance (MIC, 1 μg/ml), two others caused a 50% reduction in resistance (F593Y and A636S), and two mutations, T458N and S624A, did not affect resistance. These results suggest that some additional residues outside the “Stl pocket” influence resistance to streptolydigin.

Site-directed mutagenesis of S. spectabilis rpoB.

In the case of the S. spectabilis rpoB gene product, we found some amino acid differences in cluster I only when the “rif region” was compared with that of other streptomycetes (Fig. 2). An isoleucine (I467) and a serine (S475) residue, present only in S. spectabilis, were replaced by leucine and alanine, respectively, to test if they were involved in streptovaricin resistance. We deemed it worthwhile to mutate the asparagine at position 474 (N474), which is also present in S. coelicolor, to serine. The N474S/S475A double mutation was also performed. None of the single replacements affected streptovaricin resistance compared with that of S. albus Sβ (MIC, 200 μg/ml) (Table 4). In contrast, the double substitution (N474S/S475A) reduced streptovaricin resistance to the level of the negative controls (70 μg/ml).

The opposite mutations were also made in the S. albus rpoB gene, creating S470N, A471S, L467I, and S470N/A471S mutations (Table 4). While the L467I mutation did not increase streptovaricin resistance, the S470N and A471S changes slightly increased the MIC (80 μg/ml). However, double substitution (S470N/A471S) raised resistance to a similar level to that conferred by S. spectabilis rpoB (200 μg/ml), confirming that the simultaneous replacement of these two positions is needed to confer high levels of streptovaricin resistance in S. albus.

We also performed two additional mutations in the S. spectabilis β-subunit: a threonine (T638) and an alanine (A639) located close to cluster III (Fig. 2) were replaced by lysine and serine, respectively, but these changes did not affect streptovaricin resistance.

Since rifampin and streptovaricin are structurally very similar, we determined if the substitutions performed within the S. spectabilis and S. albus rpoB genes influenced rifampin resistance. The MIC of the negative controls [S. albus J1074, S. albus(pEM4T), and S. albus Aβ] for rifampin was 5 μg/ml (Table 4), while the strains carrying S. spectabilis rpoB (S. albus Sβ) and chimeric rpoB (S. albus CASβ) were resistant, with a MIC of 40 μg/ml. In contrast with what was previously observed for streptovaricin resistance, N474S and T638K mutations decreased rifampin resistance to different extents (MICs of 5 μg/ml and 20 μg/ml, respectively). The double substitution (N474S/S475A) also reduced resistance (MIC, 5 μg/ml), while the rest of the mutations had no effect. In the case of the S. albus mutants, only the simultaneous replacement of S470 and A471 (S470N/A471S) increased rifampin resistance to the level conferred by S. spectabilis rpoB (Table 4). These results indicate that the interactions between rifampin or streptovaricin and the S. spectabilis β subunit might be different but that both the N474 and S475 residues are involved in them.

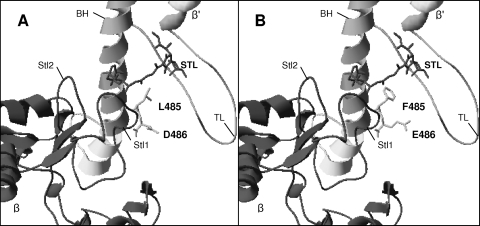

Homology modeling of S. lydicus and S. spectabilis RpoB and RpoC.

Given that the structures of S. lydicus and S. spectabilis RNAP have not been resolved, we decided to construct structural homology models that could explain the effects of mutations. The homology models of the S. lydicus RpoB and RpoC subunits were constructed with the X-ray structure of Thermus aquaticus RNAP as a template, using STL (Protein Data Bank [PDB] accession no. 1zyr [32]) (Fig. 4). We found 42.8% and 43.5% identities at the amino acid level between S. lydicus RpoB and RpoC and the equivalent subunits of T. aquaticus (1zyr_M and 1zyr_N template sequences, respectively). The Ramachandran plots of the models showed 64.4% and 69% of the residues in the most-favored regions for RpoB and RpoC, respectively, while the percentage of residues in additional allowed regions was 34.2% and 29.6%, respectively (data not shown). The homology models and the three-dimensional structures of the templates were superimposed to check their compatibility. The superimposition gave a root mean square deviation (RMSD) of 0.261 Å in both models. Based on these putative models, it can be observed that mutations in L485 should clearly affect streptolydigin resistance, as has been described for T. aquaticus (36). Thus, in the wild-type S. lydicus β-subunit, the main chain and side chain atoms of residue L485 (corresponding to F545 in T. aquaticus) are located directly adjacent to the C-4 to C-7 atoms and the C-15 and C-16 methyl groups of the streptolol moiety of streptolydigin (33). The L485F substitution is expected to favor hydrophobic and/or steric interactions with streptolydigin, thus conferring streptolydigin sensitivity. This amino acid substitution in the S. lydicus β-subunit drastically affected streptolydigin resistance. In the case of S. albus, replacement of F484 by the less bulky amino acid Leu likely would prevent streptolydigin binding. In addition to L485, the D486 residue is also located in the Stl1 domain. The D486E substitution only partially affected streptolydigin resistance in S. lydicus, and when the opposite substitution was done in S. albus, no increase in resistance was obtained. This could be explained because of the structural similarity between these two negatively charged amino acids (D and E), which differ only in the lengths of their side chains. The fact that streptolydigin susceptibility was influenced most by the double mutation strongly suggests that both residues might create a local environment affecting the interaction of streptolydigin with the Stl pocket.

FIG. 4.

Streptolydigin binding sites in modeled structures of wild-type (A) and mutated (B) RpoB (dark gray) and RpoC (light gray) subunits from S. lydicus NRRL 2433 in the presence of streptolydigin (STL). The following regions that interact with streptolydigin are indicated: Stl1, Stl2, bridge helix (BH), and trigger loop (TL). Mutated residues are shown.

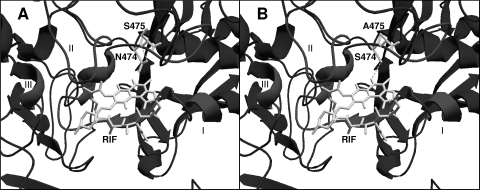

Since there is not a resolved structure of RNAP with streptovaricin, we used the structure of T. aquaticus RNAP with rifampin (PDB accession no. 1I6V [6]) to build a homology model of S. spectabilis RpoB (Fig. 5). We found 46% identity at the amino acid level between S. spectabilis RpoB and the equivalent subunit of T. aquaticus (1I6V_C). The Ramachandran plot showed 52.8% of the residues in the most-favored regions and 39.5% in additional allowed regions (data not shown). The superimposition of the homology model and the three-dimensional structure of the template showed an RMSD of 0.255 Å. In this model, a serine located at the same position as N474 makes a hydrogen bond with a critical hydroxyl group of rifampin (O-2) (Fig. 5B), so when an asparagine residue is present this interaction might not exist. The S475A substitution had no effect on either streptovaricin or rifampin resistance. However, simultaneous replacement of N474 and S475 decreased both rifampin and streptovaricin resistance to the levels of the negative controls. Interestingly, when the opposite mutations were made in S. albus, only the double substitution (S470N/A471S) restored the streptovaricin and rifampin resistance to the level conferred by S. spectabilis rpoB. The single S470N and A471S substitutions just slightly increased streptovaricin resistance. These results indicate that interactions of rifampin and streptovaricin with RNAP may be different despite their similar chemical structures.

FIG. 5.

Rifampin binding sites in modeled structures of wild-type (A) and mutated (B) RpoB from S. spectabilis NRRL 2494 in the presence of rifampin (RIF). Clusters I, II, and III (rif region) and mutated residues are indicated. Hydrogen bonds are shown as dashed lines.

DISCUSSION

Modification of the antibiotic target site is a well-extended molecular resistance mechanism in antibiotic producers. Streptomycetes producing inhibitors of RNAP seem to have developed target site modification by altering specific and selective residues of the RNAP. In the streptolydigin and streptovaricin producers, modifications in this complex enzyme apparently reside in rpoB, since its expression in a sensitive host confers resistance to these drugs. However, expression of resistance-conferring rpoB in S. albus did not confer such a high level of resistance to streptolydigin or streptovaricin as that of the producer organism. There are at least two possible explanations for this fact. On one hand, the newly formed recombinant S. albus strains contained two types of RNAP complexes: one harboring the host β-subunit (streptolydigin or streptovaricin sensitive) and the other containing the β-subunit of the producer organism. It might be possible that in these partial diploids (or merodiploids) sensitivity could be dominant against resistance, as has been reported for other merodiploid systems (15, 19). On the other hand, some other genes are well known to contribute to self-resistance in the producer organism. In particular, genes involved in secretion of the drug upon its biosynthesis have been found quite generally to be present within the gene cluster and to confer resistance to the produced antibiotic. In the streptolydigin cluster, genes of this class form part of the cluster (26), and they are supposed to also be present in the streptovaricin cluster.

According to the model of interaction between streptolydigin and Thermus aquaticus RNAP (35), streptolydigin interacts with two β-subunit loops (Stl1 and Stl2) and the bridge helix and trigger loop of the β′-subunit. In the case of the S. lydicus β′-subunit, amino acid sequence comparisons with the same subunits of other streptomycetes did not show differences in the bridge helix, but in the trigger loop there was a leucine at position 1021 that differed from the glutamine present in the rest of the streptomycetes. However, since S. albus transconjugants harboring S. lydicus rpoC were totally sensitive to streptolydigin, we can discard a direct and important role of this subunit in streptolydigin resistance in S. lydicus, but we cannot exclude a potential collaborative effect with the β-subunit.

Expression of S. lydicus rpoB in S. albus and also that of the “rif region” did confer resistance to streptolydigin, thus involving the β-subunit of RNAP, in particular a region encompassing 219 amino acids, in streptolydigin resistance. Two amino acid residues (L485 and D486) located within the Stl1 motif were found to be important for streptolydigin resistance in S. lydicus. Replacement of the LD pair (present in S. lydicus) with the FE pair (present in S. albus) or vice versa (changing FE to LD) caused streptolydigin sensitivity or resistance, respectively. The structural models constructed with S. lydicus RpoB and RpoC clearly explain the involvement of the L485 residue in streptolydigin resistance. In fact, it has been described that replacement of the equivalent Phe residue in E. coli confers high levels of streptolydigin resistance (13, 22, 32, 36).

In the case of mutations conferring resistance to streptovaricin, we also confirmed that both the expression of S. spectabilis rpoB in S. albus and that of the “rif region” conferred resistance to streptovaricin and rifampin. The N474S substitution, as shown in the RpoB structural model, was found to be important for rifampin resistance, but not for streptovaricin resistance, in S. spectabilis. Interestingly, mutations of this amino acid residue have been found in rifampin-resistant clinical isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (28). Only the N474S/S475A double mutation abolished streptovaricin resistance, indicating that streptovaricin and rifampin interact differentially with RNAP. Nevertheless, in spite of the importance of all these residues, other amino acid residues may influence streptolydigin and streptovaricin resistance in some way. Further studies at the structural level, together with mutagenesis experiments, will be necessary to evaluate the exact roles of the different mutations.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (grant BFU2006-00404 to J.A.S.) and the Red Temática de Investigación Cooperativa de Centros de Cáncer (Ministry of Health; grant ISCIII-RETIC RD06/0020/0026).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 February 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adelman, K., J. Yuzenkova, A. La Porta, N. Zenkin, J. Lee, J. T. Lis, S. Borukhov, M. D. Wang, and K. Severinov. 2004. Molecular mechanism of transcription inhibition by peptide antibiotic microcin J25. Mol. Cell 14:753-762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnold, K., L. Bordoli, J. Kopp, and T. Schwede. 2006. The SWISS-MODEL workspace: a web-based environment for protein structure homology modelling. Bioinformatics 22:195-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benveniste, R., and J. Davies. 1973. Aminoglycoside antibiotic-inactivating enzymes in actinomycetes similar to those present in clinical isolates of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 70:2276-2280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanco, M. G., C. Hardisson, and J. A. Salas. 1984. Resistance in inhibitors of RNA polymerase in actinomycetes which produce them. J. Gen. Microbiol. 130:2883-2891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell, E. A., N. Korzheva, A. Mustaev, K. Murakami, S. Nair, A. Goldfarb, and S. A. Darst. 2001. Structural mechanism for rifampicin inhibition of bacterial RNA polymerase. Cell 104:901-912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell, E. A., O. Pavlova, N. Zenkin, F. Leon, H. Irschik, R. Jansen, K. Severinov, and S. A. Darst. 2005. Structural, functional, and genetic analysis of sorangicin inhibition of bacterial RNA polymerase. EMBO J. 24:674-682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cassani, G., R. R. Burgess, H. M. Goodman, and L. Gold. 1971. Inhibition of RNA polymerase by streptolydigin. Nat. New Biol. 230:197-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chater, K. F., and L. C. Wilde. 1980. Streptomyces albus G mutants defective in the SalGI restriction-modification system. J. Gen. Microbiol. 116:323-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cundliffe, E. 1989. How antibiotic-producing organisms avoid suicide. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 43:207-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cundliffe, E. 1992. Self-protection mechanisms in antibiotic producers. Ciba Found. Symp. 171:199-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Darst, S. A. 2004. New inhibitors targeting bacterial RNA polymerase. Trends Biochem. Sci. 29:159-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heisler, L. M., H. Suzuki, R. Landick, and C. A. Gross. 1993. Four contiguous amino acids define the target for streptolydigin resistance in the beta subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. J. Biol. Chem. 268:25369-25375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hooft, R. W. W., G. Vriend, C. Sander, and E. E. Abola. 1996. Errors in protein structures. Nature 381:272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ilyina, T. S., M. I. Ovadis, S. Z. Mindlin, Z. M. Gorlenko, and R. B. Khesin. 1971. Interaction of RNA polymerase mutations in haploid and merodiploid cells of Escherichia coli K-12. Mol. Gen. Genet. 110:118-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishikawa, J., A. Yamashita, Y. Mikami, Y. Hoshino, H. Kurita, K. Hotta, T. Shiba, and M. Hattori. 2004. The complete genomic sequence of Nocardia farcinica IFM 10152. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:14925-14930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ishikawa, J., K. Chiba, H. Kurita, and H. Satoh. 2006. Contribution of rpoB2 RNA polymerase beta subunit gene to rifampin resistance in Nocardia species. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:1342-1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jin, D. J., and C. A. Gross. 1988. Mapping and sequencing of mutations in the Escherichia coli rpoB gene that lead to rifampicin resistance. J. Mol. Biol. 202:45-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kashlev, M. V., A. I. Gragerov, and V. G. Nikiforov. 1989. Heat shock response in Escherichia coli promotes assembly of plasmid encoded RNA polymerase β-subunit into RNA polymerase. Mol. Gen. Genet. 216:469-474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kieser, T., M. J. Bibb, M. J. Buttner, K. F. Chater, and D. A. Hopwood. 2000. Practical Streptomyces genetics. The John Innes Foundation, Norwich, United Kingdom.

- 21.Laskowski, R. A., M. W. MacArthur, D. S. Moss, and J. M. Thornton. 1993. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26:283-291. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lisitsyn, N. A., E. D. Sverdlov, E. P. Moiseeva, and V. G. Nikiforov. 1985. Localization of mutation leading to resistance of E. coli RNA polymerase to the antibiotic streptolydigin in the gene rpoB coding for the beta-subunit of the enzyme. Bioorg. Khim. 11:132-134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McClure, W. R. 1980. On the mechanism of streptolydigin inhibition of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. J. Biol. Chem. 255:1610-1616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Méndez, C., and J. A. Salas. 1998. ABC transporters in antibiotic-producing actinomycetes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 158:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Menéndez, N., M. Nur-e-Alam, C. Fischer, A. F. Braña, J. A. Salas, J. Rohr, and C. Méndez. 2006. Deoxysugar transfer during chromomycin A3 biosynthesis in Streptomyces griseus subsp. griseus: new derivatives with antitumor activity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 53:903-915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olano, C., C. Gómez, M. Pérez, M. Palomino, A. Pineda-Lucena, R. J. Carbajo, A. F. Braña, C. Méndez, and J. A. Salas. 2009. Deciphering biosynthesis of the RNA polymerase inhibitor streptolydigin and generation of glycosylated derivatives. Chem. Biol. 16:1031-1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Neill, A., B. Oliva, C. Storey, A. Hoyle, C. Fishwick, and I. Chopra. 2000. RNA polymerase inhibitors with activity against rifampin-resistant mutants of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:3163-3166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramaswamy, S., and J. M. Musser. 1998. Molecular genetic basis of antimicrobial agent resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: 1998 update. Tuber. Lung Dis. 79:3-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 30.Sanger, F., S. Nicklen, and A. R. Coulson. 1977. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 74:5463-5467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Severinov, K., M. Soushko, A. Goldfarb, and V. Nikiforov. 1993. Rifampicin region revisited. New rifampicin-resistant and streptolydigin-resistant mutants in the beta subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. J. Biol. Chem. 268:14820-14825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Severinov, K., D. Markov, E. Severinova, V. Nikiforov, R. Landick, S. A. Darst, and A. Goldfarb. 1995. Streptolydigin-resistant mutants in an evolutionarily conserved region of the beta′ subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. J. Biol. Chem. 270:23926-23929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siddhikol, C., J. W. Erbstoeszer, and B. Weisblum. 1969. Mode of action of streptolydigin. J. Bacteriol. 99:151-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siminoff, P., R. M. Smith, W. T. Sokolski, and G. M. Savage. 1957. Streptovaricin. I. Discovery and biologic activity. Am. Rev. Tuberc. Pulmon. Dis. 75:576-583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Temiakov, D., N. Zenkin, M. N. Vassylyeva, A. Perederina, T. H. Tahirov, E. Kashkina, M. Savkina, S. Zorov, V. Nikiforov, N. Igarashi, N. Matsugaki, S. Wakatsuki, K. Severinov, and D. G. Vassylyev. 2005. Structural basis of transcription inhibition by antibiotic streptolydigin. Mol. Cell 19:655-666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tuske, S., S. G. Sarafianos, X. Wang, B. Hudson, E. Sineva, J. Mukhopadhyay, J. J. Birktoft, O. Leroy, S. Ismail, A. D. Clark, Jr., C. Dharia, A. Napoli, O. Laptenko, J. Lee, S. Borukhov, R. H. Ebright, and E. Arnold. 2005. Inhibition of bacterial RNA polymerase by streptolydigin: stabilization of a straight-bridge-helix active-center conformation. Cell 122:541-552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vieira, J., and J. Messing. 1991. New pUC-derived cloning vectors with different selectable markers and DNA replication origins. Gene 100:189-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vigliotta, G., S. M. Tredici, F. Damiano, M. R. Montinaro, R. Pulimeno, R. di Summa, D. R. Massardo, G. V. Gnoni, and P. Alifano. 2005. Natural merodiploidy involving duplicated rpoB alleles affects secondary metabolism in a producer actinomycete. Mol. Microbiol. 55:396-412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wehrli, W. 1977. Ansamycins. Chemistry, biosynthesis and biological activity. Top. Curr. Chem. 72:21-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang, X., and C. W. Price. 1995. Streptolydigin resistance can be conferred by alterations to either the beta or beta′ subunits of Bacillus subtilis RNA polymerase. J. Biol. Chem. 270:23930-23933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yuzenkova, J., M. Delgado, S. Nechaev, D. Savalia, V. Epshtein, I. Artsimovitch, R. A. Mooney, R. Landick, R. N. Farias, R. Salomon, and K. Severinov. 2002. Mutations of bacterial RNA polymerase leading to resistance to microcin J25. J. Biol. Chem. 277:50867-50875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]