Abstract

Murine models of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection are essential tools in drug discovery. Here we describe a fast standardized 9-day acute assay intended to measure the efficacy of drugs against M. tuberculosis growing in the lungs of immunocompetent mice. This assay is highly reproducible, allows good throughput, and was validated for drug lead optimization using isoniazid, rifampin, ethambutol, pyrazinamide, linezolid, and moxifloxacin.

The appearance of clinical resistance to first-line drugs (8) and the long treatments have prompted a renewed effort in tuberculosis drug discovery. Efficacy in animal models is a key criterion for selection of compounds. In order to address its complexity, tuberculosis can be deconstructed by modeling specific pathological characteristics of the human infection separately (15). Assays designed to measure the ability of a drug to kill Mycobacterium tuberculosis actively replicating in the lungs can be easily modeled in mice (12) and are relevant because most fatalities are caused by lung infections. The model using C57BL/6 (B6) gamma interferon (IFN-γ)-disrupted mice (GKO) and low-dose aerosol infection (9) is particularly well suited for the objective above since (i) the lungs are the primary infected organs, (ii) antitubercular efficacy is almost exclusively due to drug action, since GKO mice do not mount an effective adaptive immune response (6), and (iii) the model is reproducible and sensitive (9). However, this model requires 30 days from infection to sacrifice, and GKO mice are relatively expensive animals. In order to overcome these drawbacks, a fast therapeutic-efficacy assay against replicating M. tuberculosis H37Rv in the lungs of wild-type B6 mice was developed and standardized.

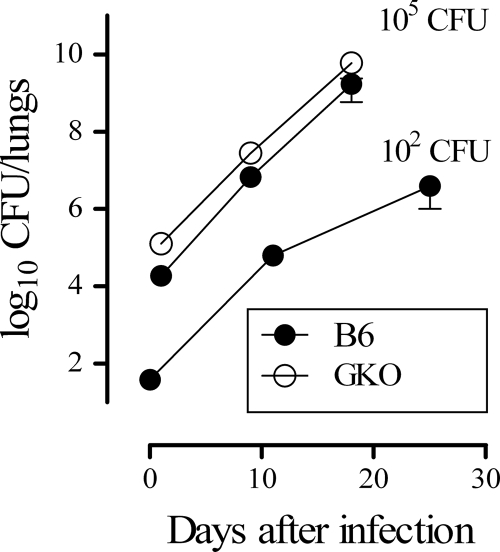

The assay should (i) allow significant bacterial growth after lung infection, (ii) enable detection of drug exposures that kill bacteria in lungs, (iii) minimize the duration of the assay, and (iv) maximize the duration of treatment. Bacterial growth of about 2 logs over the initial inoculum was determined to be a level that would provide enough dynamic range to detect statistically significant growth inhibition. Infection was initiated by nonsurgical intratracheal instillation of M. tuberculosis H37Rv. In brief, mice were anesthetized with 3% isoflurane and intubated with a metal probe (catalog number 27134; Unimed SA, Lausanne, Switzerland) as described previously (2). The inoculum (105 CFU/mouse suspended in 50 μl of phosphate-buffered saline) was put into the probe and delivered through forced inhalation with a syringe (14). To measure infection burden in lungs, all lobes were aseptically removed and homogenized. The homogenates were supplemented with 5% glycerol and stored frozen (−80°C) until plating. No significant differences were observed between fresh and frozen homogenates obtained from mice not treated or treated with antituberculars and having bacterial loads in the dynamic range of the assay (data not shown). After 14 days of culture, colonies were counted using an automatic colony counter (aCOLyte-Supercount; Synoptics Ltd., Cambridge, United Kingdom) and confirmed by visual inspection to correct potential misreadings. Consistent with an in vivo duplication time of approximately 24 h, the 2 logs of growth was achieved 9 days after infecting 8- to 10-week-old B6 female mice (Harlan, Barcelona, Spain) (Fig. 1). The initial inoculum selected for the assay (105 CFU/mouse) led to 6.94 ± 0.38 log10 CFU/lung (mean ± standard deviation [SD]) at day 9 (normally distributed; Shapiro-Wilk normality test, P = 0.46; n = 154 mice, pooled from 31 different experiments). Thus, this enabled us to detect a 0.7-log reduction in CFU/lung for the 5% confidence level and 90% power using n = 5 mice/group. Under these conditions it is possible to detect drug exposures insufficient to achieve net inhibition of bacterial growth (dynamic range, ∼2 logs) as well as drug exposures able to kill M. tuberculosis (dynamic range, ∼3 logs). Finally, the duration of treatment with test drugs was maximized by allowing a period of 24 h for phagocytosis of instilled bacteria and another additional 24 h for clearance of compounds before organ harvesting.

FIG. 1.

Kinetics of growth of H37Rv in vivo. B6 mice were infected by intratracheal instillation with 102 or 105 CFU H37Rv per mouse. CFU counts were measured from lungs obtained at different time points. GKO (B6.129S7-Ifngtm1Ts/J) mice were infected by intratracheal instillation with 105 CFU H37Rv per mouse. Data are the means ± SDs of the log10 CFU/lung of five mice per time point.

Under our experimental conditions the adaptive immune response likely did not impair growth of M. tuberculosis in B6 mice during the assay period (4, 5), since infection of wild-type B6 or GKO female mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) with 105 CFU/mouse showed the same rate of bacterial growth (Fig. 1) and it was lethal to both murine strains (median survival times, defined as a weight loss of >20% of initial weight, were 15.1, 15.7, and 18 days for B6 and 17.4 and 20.7 days for GKO mice in five independent experiments). In addition, lungs of infected B6 and GKO mice at day 9 after infection displayed similar uniformly scattered lymphoid or multicellular aggregates (lymphocytes, neutrophils, macrophages, and foamy macrophages) of less than 0.5 mm containing bacilli inside macrophages.

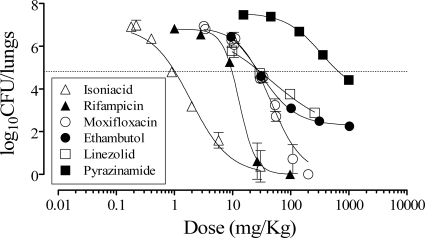

In order to validate the assay, different doses of known antituberculars were tested (Fig. 2 and Table 1). The individual log10 CFU/lung versus log10 dose administered fit a logistic equation in which compounds showed characteristic Hill's slopes and maximum inhibition (Fig. 2). The therapeutic efficacy of each drug was assessed at day 9 and expressed as the dose that inhibited 99% of CFU/lung with respect to untreated controls (ED99) and the lowest dose at which maximum inhibition of CFU/lung (EDmax) was achieved. The ED99 measures a compound's potency and is an accurate estimate of the limit between doses with no net inhibitory or net killing effect in vivo (1), while the EDmax is the optimal dose for treatment (Table 1). Although not directly comparable to other assays, the ranking of potencies found was consistent with previously published data (13). Interestingly, compounds more active against replicating bacteria (isoniazid and ethambutol) appeared more potent in this assay than in chronic models, while rifampin and pyrazinamide lost potency in our assay (10). These data are consistent with the known activity profiles of the compounds and our target assay design.

FIG. 2.

Therapeutic efficacy of antituberculars against H37Rv in vivo. B6 mice were infected by intratracheal instillation with 105 CFU H37Rv per mouse. The mice were treated with antituberculars orally once a day from day 1 to day 8. Data are the means ± SDs of the log10 CFU/lung of five mice per time point. The dashed line indicates the log10 CFU/lung at the ED99.

TABLE 1.

Therapeutic efficacies against M. tuberculosis H37Rv replicating in the lungs of B6 micea

| Compound | Vehicle | ED99 (mg/kg)b | EDmax (mg/kg)c |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isoniazid | Water | 0.95 (0.86-1.07) | 25 |

| Rifampin | Water-20% Encapsine | 9.8 (9.0-10.7) | 30 |

| Pyrazinamide | Water-1% methylcellulose | 362.0 (319.0-409.0) | ≥1,000d |

| Ethambutol | Water-1% methylcellulose | 21.6 (19.9-23.5) | 300 |

| Moxifloxacin | Water-20% Captisol | 27.7 (26.2-29.3) | 100 |

| Linezolid | Water-1% methylcellulose | 28.0 (23.7-32.9) | ≥300d |

Data are from five mice/group.

The dose that results in a 2-log reduction in bacterial burden in the lungs of mice. Data were calculated from individual log10 CFU/lung values fit to a logistic equation. Data are expressed as the ED99, with the 95% confidence interval of the ED99 shown in parentheses.

Estimated empirically as the lowest dose administered to mice that reduced bacterial burden in the lungs to a level statistically indistinguishable from reductions achieved with higher doses.

Highest dose used in the assay.

The assay was found to be very reproducible using moxifloxacin, which is stable and potent and shows a low frequency of spontaneous resistant mutants compared to controls (ED99 for moxifloxacin, 28.1, 26.7, and 26.9 mg/kg of body weight in three independent experiments). Thereafter, a group of mice treated with moxifloxacin at 30 mg/kg, a dose close to its ED99, was always included in each assay in order to obtain an assay quality parameter [ΔMOX = (log10 CFU/lung in untreated controls) − (log10 CFU/lung at the ED99 for moxifloxacin)]. An in vivo assay is deemed valid if the log10 CFU/lung in untreated controls is in the range of 6.18 to 7.7 and ΔMOX is in the range of 2.21 to 2.92 log10 CFU/lung.

In this paper we have proposed a standardized assay intended to evaluate new drugs against M. tuberculosis replicating in the lungs. Its design enables ranking of antituberculars according to their potency (ED99), a parameter currently being used in lead optimization of M. tuberculosis gyrase B and InhA inhibitors. In addition, the EDmax is proposed as another parameter of efficacy that is not intended to directly compare compounds but to estimate the lowest dose of a drug candidate to be tested in chronic models of infection. As actively replicating mycobacteria may be a subpopulation present in the lungs of chronically infected mice (3, 11), the starting drug exposures chosen should be capable of killing at least that subpopulation. Of note, rifampin's EDmax is ≥30 mg/kg (Table 1), which is higher than doses usually employed in murine chronic models and is already suspected to be suboptimal (7). Overall, the standardized assay described in this paper may be a suitable tool for drug discovery that could guide subsequent in vivo studies, for which the validity of the approach awaits confirmation.

Acknowledgments

Joaquín Rullas, Juan I. García, and Manuela Beltrán were supported by the Global Alliance for TB Drug Development—GlaxoSmithKline, Diseases of the Developing World Miniportfolio Agreement.

We acknowledge the support of all the staff at the Laboratory Animal Science Department in GlaxoSmithKline's Diseases of the Developing World Drug Discovery Center in Tres Cantos, Spain, for procuring and maintaining all mice used in this study. We are indebted to Maria Teresa Fraile and her staff from Computational, Analytical and Structural Chemistry for preparation of formulations and quality control analysis. We acknowledge the work of María Angeles Burgos for culture medium preparation and David Barros and María Belén Jiménez-Díaz for critical review of the manuscript.

All the experiments were approved by the GlaxoSmithKline Diseases of the Developing World (DDW) Ethical Committee on Animal Research, performed at the DDW Laboratory Animal Science facilities accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International, and conducted according to European Union legislation and GlaxoSmithKline policy on the care and use of animals.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 16 February 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andes, D., and W. A. Craig. 2006. Pharmacodynamics of a new streptogramin, XRP 2868, in murine thigh and lung infection models. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:243-249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown, R. H., D. M. Walters, R. S. Greenberg, and W. Mitzner. 1999. A method of endotracheal intubation and pulmonary functional assessment for repeated studies in mice. J. Appl. Physiol. 87:2362-2365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cardona, P. J. 2009. A dynamic reinfection hypothesis of latent tuberculosis infection. Infection 37:80-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chackerian, A. A., J. M. Alt, T. V. Perera, C. C. Dascher, and S. M. Behar. 2002. Dissemination of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is influenced by host factors and precedes the initiation of T-cell immunity. Infect. Immun. 70:4501-4509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooper, A. M. 2009. Cell-mediated immune responses in tuberculosis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 27:393-422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper, A. M., D. K. Dalton, T. A. Stewart, J. P. Griffin, D. G. Russell, and I. M. Orme. 1993. Disseminated tuberculosis in interferon gamma gene-disrupted mice. J. Exp. Med. 178:2243-2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies, G. R., and E. L. Nuermberger. 2008. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in the development of anti-tuberculosis drugs. Tuberculosis (Edinburgh) 88(Suppl. 1):S65-S74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jassal, M., and W. R. Bishai. 2009. Extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 9:19-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lenaerts, A. J., V. Gruppo, J. V. Brooks, and I. M. Orme. 2003. Rapid in vivo screening of experimental drugs for tuberculosis using gamma interferon gene-disrupted mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:783-785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsumoto, M., H. Hashizume, T. Tomishige, M. Kawasaki, H. Tsubouchi, H. Sasaki, Y. Shimokawa, and M. Komatsu. 2006. OPC-67683, a nitro-dihydro-imidazooxazole derivative with promising action against tuberculosis in vitro and in mice. PLoS Med. 3:e466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muñoz-Elías, E. J., J. Timm, T. Botha, W. T. Chan, J. E. Gómez, and J. D. McKinney. 2005. Replication dynamics of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in chronically infected mice. Infect. Immun. 73:546-551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nikonenko, B. V., K. A. Sacksteder, S. Hundert, L. Einck, and C. A. Nacy. 2008. Preclinical study of new TB drugs and drug combinations in mouse models. Recent Pat. Antiinfect. Drug Discov. 3:102-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nikonenko, B. V., R. Samala, L. Einck, and C. A. Nacy. 2004. Rapid, simple in vivo screen for new drugs active against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:4550-4555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oka, Y., M. Mitsui, T. Kitahashi, A. Sakamoto, O. Kusuoka, T. Tsunoda, T. T. Mori, and M. Tsutsumi. 2006. A reliable method for intratracheal instillation of materials to the entire lung in rats. J. Toxicol. Pathol. 19:107-109. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Young, D. 2009. Animal models of tuberculosis. Eur. J. Immunol. 39:2011-2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]