Abstract

Determining the “correlates of protection” is one of the challenges in human immunodeficiency virus vaccine design. To date, T-cell-based AIDS vaccines have been evaluated with validated techniques that measure the number of CD8+ T cells in the blood that secrete cytokines, mainly gamma interferon (IFN-γ), in response to synthetic peptides. Despite providing accurate and reproducible measurements of immunogenicity, these methods do not directly assess antiviral function and thus may not identify protective CD8+ T-cell responses. To better understand the correlates of vaccine efficacy, we analyzed the immune responses elicited by a successful T-cell-based vaccine against a heterologous simian immunodeficiency virus challenge. We searched for correlates of protection using a viral suppression assay (VSA) and an IFN-γ enzyme-linked immunospot assay. While the VSA measured in vitro suppression, it did not predict the outcome of the vaccine trial. However, we found several aspects of the vaccine-induced T-cell response that were associated with improved outcome after challenge. Of note, broad vaccine-induced prechallenge T-cell responses directed against Gag and Vif correlated with lower viral loads and higher CD4+ lymphocyte counts. These results may be relevant for the development of T-cell-based AIDS vaccines since they indicate that broad epitope-specific repertoires elicited by vaccination might serve as a correlate of vaccine efficacy. Furthermore, the present study demonstrates that certain viral proteins may be more effective than others as vaccine immunogens.

CD8+ T cells play a vital role in immune control of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection (2, 12, 20, 22, 27, 41). As a result, many vaccine candidates under development aim to induce cellular immune responses against the virus (16, 58, 61). These strategies have been evaluated based on their immunogenicity, that is, their capacity to induce gamma interferon (IFN-γ) production by HIV-specific CD8+ T cells (15, 60). However, it is becoming increasingly clear that this measure of T-cell responses cannot solely be used to predict vaccine efficacy (11, 15, 44, 60, 61). We therefore need to develop a technique for measuring T-cell immunity that will reflect effective antiviral responses in vivo.

Two assays have been validated to assess T-cell responses in HIV vaccine trials (15). Based on IFN-γ secretion by antigen-stimulated T cells, the enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay provides a quantitative measure of circulating virus-specific T lymphocytes. Similarly, intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) uses flow cytometric methods to identify responding cells in both the CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell compartments. Using these assays, it has been shown that control of viral replication in HIV-infected individuals is affected by which viral proteins are targeted by the immune system (31). Gag-directed cellular responses, for instance, have been repeatedly associated with lower viral loads (9, 17, 31, 52), whereas T-cell responses targeting Env have actually been linked to higher viremia (31, 49). These studies are directly applicable to vaccine development, since they provide information on which immunogens might induce the most effective T-cell responses.

Despite being invaluable tools for determining cellular reactivity to HIV antigens, the ELISPOT assay and ICS do not directly measure antiviral function (4, 60, 61). These assays typically involve loading cells with supraphysiological concentrations of synthetic peptides containing T-cell epitopes. These conditions bypass the antigen trafficking and processing pathways that operate in naturally infected cells to allow for CD8+ T-cell recognition. Importantly, it has been demonstrated that the ability of CD8+ T cells to recognize epitope variants in the ELISPOT assay does not correlate with their capacity to suppress replication of variant viruses in tissue culture (7, 8, 57). Furthermore, cytokine secretion does not always identify CD8+ T cells capable of suppressing viral replication in vitro (14). Most importantly, the ability to produce IFN-γ in an ELISPOT assay does not correlate with the control of viral replication (1).

A few alternative approaches have been proposed as surrogate markers of efficacious T-cell responses. The ability of T cells to perform multiple functions upon antigen encounter, commonly referred to as polyfunctionality, has been correlated with enhanced immune control of HIV-1 infection (10, 56). However, it is unknown to what extent polyfunctional T cells are a cause or effect of viral containment. A more direct analysis of CD8+ T-cell-mediated antiviral activity has come from studies measuring in vitro suppression of HIV-1 replication in autologous CD4+ targets (18, 47, 55). Using this parameter, two groups have demonstrated that individuals who spontaneously control HIV-1 replication (termed elite controllers) have CD8+ T cells that suppress viral replication more efficiently than those obtained from patients progressing to AIDS (47, 55). Thus, assays based on the HIV-suppressive capacity of CD8+ T cells might be useful for screening potential AIDS T-cell-based vaccine strategies.

We have recently vaccinated eight Indian rhesus macaques with a DNA prime, Ad5 boost regimen encoding all SIVmac239 proteins, except for the Envelope protein (59). After repeated low-dose mucosal challenge with the heterologous swarm virus SIVsmE660, most vaccinated animals controlled acute-phase viremia (59). Indeed, six of the eight vaccinees have no detectable virus 1 year after challenge. Here, we attempted to determine the correlates of this vaccine-induced protection. Surprisingly, the ability of prechallenge vaccine-elicited CD8+ T cells to suppress viral replication in vitro did not predict the control of viral replication in vivo. However, a comprehensive analysis of cellular immune responses in vaccinees revealed several positive correlations with successful outcome after challenge. In particular, the breadth of T-cell responses directed against Gag and Vif correlated with lower viral loads and preservation of CD4+ T-cell numbers after a heterologous challenge.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

The animals in the present study were Indian rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) from the Wisconsin National Primate Research Center colony. They were typed for major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) alleles Mamu-A*01, Mamu-A*02, Mamu-A*08, Mamu-A*11, Mamu-B*01, Mamu-B*03, Mamu-B*04, Mamu-B*08, Mamu-B*17, and Mamu-B*29 by sequence-specific PCR analysis (28, 36). We chose animals that were Mamu-A*02 positive for the present study, whereas those that were positive for Mamu-A*01, Mamu-B*08, and Mamu-B*17 were excluded. The presence of Mamu-B*08 or Mamu-B*17 alone has been correlated to a reduction in plasma viremia (36, 62). Although the effect is much weaker, Mamu-A*01 expression has also been linked to control of viral replication (13, 63). Animals were cared for according to the regulations and guidelines of the University of Wisconsin Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Viral suppression assay.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were obtained on day −2 by using Ficoll-Paque Plus (Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden) density centrifugation. We generated targets by depleting CD8+ cells from PBMC by using a MACS nonhuman primate CD8 MicroBead kit (Miltenyi Biotec), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The targets were activated by incubation with concanavalin A (5 μg/ml) for 18 to 24 h. Cells were cultured in R15-50 (RPMI 1640 containing 15% fetal calf serum and 50 U of interleukin-2/ml) throughout all parts of the assay. On day 0, we obtained CD3+ CD8+ effectors from control and vaccinated animals by using a MACS nonhuman primate CD8+ T-cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec). These cells were consistently >90% pure. We used sucrose-purified SIVmac239 or SIVsmE660 (109 vRNA copies) to infect targets by spinoculation (48). We incubated 5 × 105 target cells per well in 96-well plates with the concentrated viruses in a final volume of 100 μl. Then, we centrifuged the plates at 1,200 × g for 2 h at 25°C and washed the cells twice with medium. We mixed the superinfected targets with uninfected targets in a 1:10 ratio to seed the infection. We cocultured 105 cells of this mixture of infected targets with autologous effectors in 24-well plates for 7 days. We used three effector/target (E:T) ratios: 0.1:1, 0.5:1, and 1:1. On days 3 and 5, we removed 0.5 ml of supernatant from each well and replaced it with fresh R15-50. On day 7, we harvested the cells and stained them with fluorescently labeled antibodies specific to CD3, CD4, and CD8 (BD Biosciences). We then permeabilized the cells with Fix-and-Perm (Caltag, Burlingame, CA) and stained them with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated antibodies specific to SIV Gag p27 (NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Germantown, MD). The samples were then washed twice and run on a BD-LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) using FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences). The data were analyzed by using FlowJo for Macintosh (Tree star). We quantified suppression of viral replication based on the percent reduction of SIV Gag+ cells using the following formula: [(% of SIV Gag+ targets in the absence of effectors) - (% of SIV Gag+ targets at E:T ratios)/(% of SIV Gag+ targets in the absence of effectors)] × 100.

Vaccination and challenge.

A complete description of these items was published as part of a prior study (59). Briefly, we used a DNA/Ad5 prime-boost regimen to immunize animals with codon-optimized sequences encoding the following proteins from SIVmac239: Gag, Tat, Rev, Nef, Pol, Vif, Vpr, and Vpx. Thirty-seven weeks after vaccination was completed, animals in the vaccinated and control groups were challenged intrarectally with up to five challenges of SIVsmE660 (800 50% tissue culture infective doses [TCID50]; 1.2 × 107 SIV RNA copy eq). If not infected, they were subsequently challenged with a five times higher dose (4,000 TCID50 or 6.0 × 107 SIV RNA copy eq) until infected. We used repeated low-dose mucosal challenges (43) with SIVsmE660 to better approximate clinical exposures to HIV. Animals were considered to be infected after at least two consecutive positive viral load determinations, after which they were no longer challenged.

Viral load determination and absolute CD4+ T-cell counts.

A complete description of these items was published as part of a prior study (59). Levels of circulating plasma virus were determined by using a previously described quantitative reverse transcription-PCR assay (51). Virus concentrations were determined by interpolation onto a standard curve of in vitro-transcribed RNA standards in serial 10-fold dilutions by using the Lightcycler 2.0 (v4; Roche). To get absolute CD4+ T-cell counts, whole PBMC were stained with fluorescently labeled antibodies specific for CD3 Alexa 700 (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), CD4 PerCP (BD Pharmingen), CD8 Pacific Blue (BD Pharmingen), CD95 fluorescein isothiocyanate (BD Pharmingen), CD28 phycoerythrin (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA), and beta7 integrin allophycocyanin (BD Biosciences). In brief, 500,000 PBMC were incubated with these antibodies for 30 min at room temperature. The samples were then washed twice, fixed with paraformaldehyde, and run on a BD-LSR-II flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) using FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences). The data were analyzed by using FlowJo software (Tree Star). Absolute counts were calculated by multiplying the frequency of CD3+/CD4+ T cells within the lymphocyte gate by the lymphocyte counts per microliter of blood obtained from matching complete blood counts.

IFN-γ ELISPOT assays.

A complete description of this technique has been published as part of a prior study (59). Briefly, whole or CD8-depleted PBMC were used in ELISPOT assays for the detection of IFN-γ-secreting cells. To determine positivity, the number of spots in duplicate wells (105 per well) was averaged, and the background was subtracted. This resultant number is required to be greater than five spots (50 spot-forming cells [SFC]/million PBMC) and also greater than two standard deviations over the background. Positive results were multiplied by 10 to get SFC/million cells.

Statistical analyses.

To compare vaccinees and control animals in the viral suppression assays, we first tested the normality and homogeneity of variances (homoscedasticity) of the suppression values by using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Levene's tests, respectively. If the variances in a given E:T ratio were heterogeneous, we used natural log-transformed values to correct for this and retested for the normality and homoscedasticity of residuals. We then compared the two groups at each E:T ratio by using either the Wilcoxon signed-rank test or the Student t test, as appropriate. For plasma viral concentrations, we log-transformed the values to reduce right-skewness and heteroscedasticity. In the comparisons of T-cell parameters and markers of disease progression (viral loads and absolute CD4+ T-cell counts), we measured correlation using the Kendall's tau and Spearman correlation tests. All significance tests were two-tailed.

RESULTS

Vaccine-induced CD8+ T cells suppress replication of a homologous virus in vitro.

We have recently tested the efficacy of a DNA/Ad5 T-cell-based vaccine encoding all SIVmac239 proteins except for Env (59). In order to define correlates of protection, we developed a viral suppression assay (VSA) to directly measure the antiviral activity of CD8+ T cells in vitro (37). This assay may be relevant for screening CD8+ T-cell responses associated with control of HIV infection (47, 55). Thus, we hypothesized that the ability of prechallenge vaccine-induced CD8+ T cells to suppress viral replication in vitro would predict the outcome of the vaccine trial.

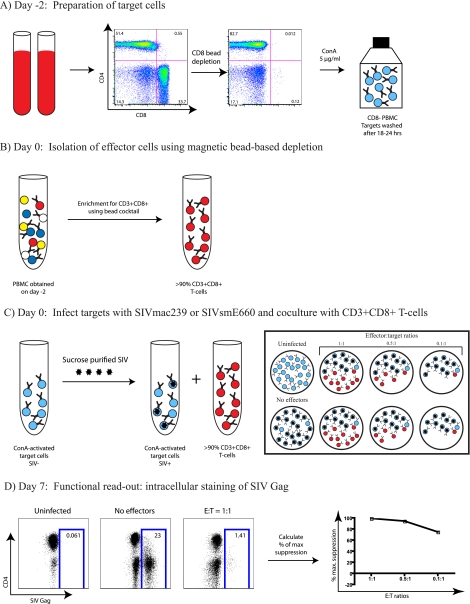

Sixteen weeks after the Ad5 boost, we began screening the suppressive ability of CD8+ T cells from both control and vaccinated animals. To setup the VSAs, we obtained fresh PBMC on day −2 (Fig. 1). Then, we depleted CD8+ cells from half of the PBMC to generate target cells and incubated them overnight with concanavalin A (ConA; 5 μg/ml) to stimulate them (Fig. 1A). We kept the unstimulated PBMC until day 0, when we isolated bulk CD8+ T cells to use as effectors (Fig. 1B). On day 0, we infected the ConA-activated targets with SIVmac239 and cultured them with the autologous unstimulated CD8+ T cells. We used 3 E:T ratios: 0.1:1, 0.5:1, and 1:1 (Fig. 1C). As described in a previous study (37), we measured suppression of viral replication after 7 days by comparing the percentage of SIV-Gag+ cells in the presence or absence of effectors (Fig. 1D).

FIG. 1.

VSA schematic. (A) PBMC-derived CD8-depleted target cells were activated with concanavalin A (5 μg/ml) for 18 to 24 h. (B) Using part of the PBMC obtained on day −2, we generated effectors (CD3+ CD8+ T cells) by bead depletion of non-CD3+ CD8+ cells. (C) We infected target cells with SIVmac239 or SIVsmE660 and then mixed effectors and targets at E:T ratios of 0.1:1, 0.5:1, and 1:1. (D) We maintained the cocultures for 7 days, and then performed intracellular staining of SIV Gag. We evaluated the percentage of maximum suppression by comparing the frequency of SIV Gag+ cells in the presence or absence of effectors.

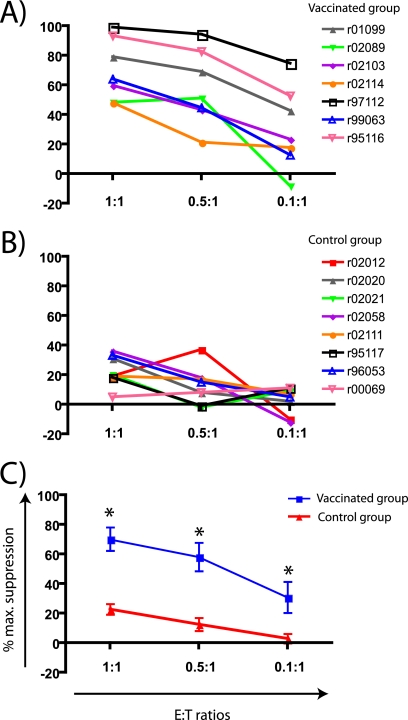

CD8+ T cells from all vaccinees suppressed SIVmac239 replication with various levels of efficiency (Table 1 and Fig. 2A). Animal r97112, for instance, had the best performance in the VSAs with suppression values higher than 75% at all E:Ts (Table 1 and Fig. 2A). However, the CD8+ T cells from animals r02114 and r02089 only suppressed viral replication by 60% or less, even at the highest E:T ratio (Table 1 and Fig. 2A). Control unvaccinated animals had low levels of suppression at the highest E:T ratio (Table 1 and Fig. 2B). Importantly, the average suppression among vaccinees was significantly higher than that of control animals at all E:T ratios (Fig. 2C). Together, these results indicate that vaccine-induced CD8+ T cells can suppress the replication of SIVmac239, a virus whose sequence is identical to the one used in the vaccine formulation.

TABLE 1.

Mean percentages of maximum suppression of SIVmac239 replication of individual vaccinated and control animals at three different E:T ratios

| Group and animal | Maximum suppression of SIVmac239 replication at E:T ratioa: |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1:1 |

0.5:1 |

0.1:1 |

|||||||

| % Suppression |

% Suppression |

% Suppression |

|||||||

| Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n | |

| Vaccinated group | |||||||||

| r00061 | 68.00 | 9.17 | 3 | 44.67 | 12.66 | 3 | 15.67 | 6.43 | 3 |

| r01099 | 79.00 | 8.89 | 3 | 69.00 | 10.44 | 3 | 42.67 | 21.08 | 3 |

| r02089 | 48.33 | 30.29 | 3 | 51.00 | 15.72 | 3 | -8.33 | 16.07 | 3 |

| r02103 | 59.67 | 22.37 | 3 | 43.33 | 20.82 | 3 | 23.33 | 6.03 | 3 |

| r02114 | 48.00 | 19.31 | 3 | 21.33 | 14.22 | 3 | 17.67 | 17.95 | 3 |

| r97112 | 99.00 | 1.00 | 3 | 94.33 | 1.53 | 3 | 74.67 | 5.51 | 3 |

| r99063 | 64.00 | 2.83 | 2 | 44.67 | 18.82 | 3 | 12.67 | 13.61 | 3 |

| r95116 | 93.33 | 2.08 | 3 | 82.67 | 8.08 | 3 | 52.67 | 5.86 | 3 |

| Control group | |||||||||

| r00069 | 5.00 | 0.00 | 1 | 8.00 | 0.00 | 1 | 11.00 | 0.00 | 1 |

| r02012 | 19.00 | 0.00 | 1 | 37.00 | 0.00 | 1 | -10.00 | 0.00 | 1 |

| r02020 | 31.00 | 0.00 | 1 | 8.00 | 0.00 | 1 | 2.00 | 0.00 | 1 |

| r02021 | 20.00 | 0.00 | 1 | -2.00 | 0.00 | 1 | 9.00 | 0.00 | 1 |

| r02058 | 36.00 | 0.00 | 1 | 18.00 | 0.00 | 1 | -12.00 | 0.00 | 1 |

| r02111 | 19.00 | 0.00 | 1 | 17.00 | 0.00 | 1 | 7.00 | 0.00 | 1 |

| r95117 | 18.33 | 3.21 | 3 | -1.00 | 32.91 | 3 | 11.00 | 40.34 | 3 |

| r96053 | 33.33 | 35.85 | 3 | 15.00 | 18.52 | 3 | 5.00 | 13.23 | 3 |

n, Number of independent measurements.

FIG. 2.

Suppression of SIVmac239 replication by vaccine-induced CD8+ T cells. Mean percentages of maximum suppression of SIVmac239 replication of individual animals in the vaccinated (A) and control (B) groups at three E:T ratios. (C) After testing for normality and homogeneity of variances, we averaged the mean percentages of maximum suppression from both vaccinated and control groups as described in Materials and Methods. We then compared both groups at each E:T ratio. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. *, P < 0.05 according to the Student t test.

Vaccine-induced CD8+ T cells suppress replication of a heterologous virus in vitro.

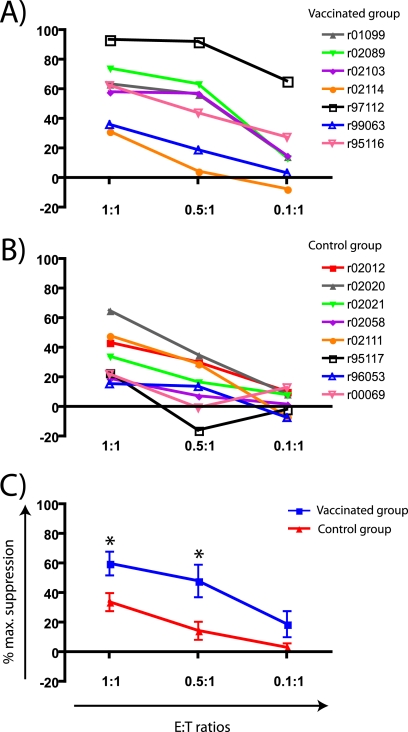

An effective AIDS vaccine must generate immunity against the tremendously diverse population of circulating viruses. Indeed, HIV isolates within a single clade can vary in sequence as much as 10 to 20%, depending on the viral gene (21). Using this rationale, we determined whether the antiviral activity of CD8+ T cells elicited against SIVmac239 by vaccination would also be effective against a different strain of SIV. We performed VSAs using targets infected with SIVsmE660, a biological isolate that differs from SIVmac239 by approximately 15% of its amino acids (59). Compared to the control group, CD8+ T cells from vaccinees suppressed the replication of SIVsmE660 in vitro at E:T ratios of 1:1 and 0.5:1 (Table 2 and Fig. 3A and C). However, suppression at the E:T ratio of 0.1:1 was not significantly different between the vaccinated and control groups (P > 0.05) (Fig. 3C). Similar to our results with SIVmac239, CD8+ T cells from r97112 had the best performance in the VSAs, while r99063 and r02114 were the worst suppressors (Table 2 and Fig. 3A). Overall, suppression of SIVsmE660 replication among vaccinees tended to match that of SIVmac239 in the VSAs, although this association only reached statistical significance at the E:T ratio of 0.1:1 (P = 0.0446; r = 0.72) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). CD8+ T cells from control animals also suppressed SIVsmE660 replication at the highest E:T ratio (Table 2 and Fig. 3B). In sum, CD8+ T cells elicited by vaccination exerted antiviral activity against a heterologous “swarm” virus in vitro. Nonetheless, this suppressive ability was lost when vaccine-induced effectors were diluted to a 0.1:1 E:T ratio.

TABLE 2.

Mean percentages of maximum suppression of SIVsmE660 replication of individual vaccinated and control animals at three different E:T ratios

| Group and animal | Maximum suppression of SIVsmE660 replication at E:T ratioa: |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1:1 |

0.5:1 |

0.1:1 |

|||||||

| % Suppression |

% Suppression |

% Suppression |

|||||||

| Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n | |

| Vaccinated group | |||||||||

| r00061 | 62.50 | 10.61 | 2 | 43.00 | 12.73 | 2 | 15.00 | 2.83 | 2 |

| r01099 | 63.50 | 16.26 | 2 | 56.50 | 7.78 | 2 | 14.50 | 17.68 | 2 |

| r02089 | 74.00 | 15.56 | 2 | 63.50 | 10.61 | 2 | 13.50 | 13.44 | 2 |

| r02103 | 58.00 | 36.77 | 2 | 57.00 | 26.87 | 2 | 15.00 | 41.01 | 2 |

| r02114 | 31.45 | 16.14 | 2 | 4.49 | 28.67 | 2 | -7.45 | 26.70 | 2 |

| r97112 | 93.56 | 2.33 | 2 | 92.10 | 1.44 | 2 | 65.44 | 8.50 | 2 |

| r99063 | 36.19 | 1.15 | 2 | 18.87 | 2.86 | 2 | 3.36 | 7.08 | 2 |

| r95116 | 62.47 | 2.20 | 2 | 43.92 | 1.90 | 2 | 27.54 | 4.36 | 2 |

| Control group | |||||||||

| r00069 | 22.12 | 35.42 | 2 | -0.61 | 24.74 | 2 | 12.98 | 17.42 | 2 |

| r02012 | 43.47 | 13.13 | 2 | 30.17 | 13.12 | 2 | 10.20 | 19.45 | 2 |

| r02020 | 65.13 | 8.28 | 2 | 35.08 | 19.81 | 2 | 8.66 | 15.37 | 2 |

| r02021 | 34.00 | 9.96 | 2 | 16.75 | 1.70 | 2 | 8.03 | 12.64 | 2 |

| r02058 | 19.15 | 8.97 | 2 | 7.23 | 6.03 | 2 | 1.69 | 2.03 | 2 |

| r02111 | 48.13 | 9.72 | 2 | 29.13 | 19.89 | 2 | -6.63 | 20.50 | 2 |

| r95117 | 23.00 | 5.66 | 2 | -16.00 | 43.84 | 2 | -2.00 | 9.90 | 2 |

| r96053 | 15.44 | 2.28 | 2 | 13.69 | 21.51 | 2 | -7.38 | 18.58 | 2 |

n, Number of independent measurements.

FIG. 3.

Suppression of SIVsmE660 replication by vaccine-induced CD8+ T cells. Mean percentages of maximum suppression of SIVsmE660 replication of individual animals in the vaccinated (A) and control (B) groups at three E:T ratios. (C) After testing for normality and homogeneity of variances, we averaged the mean percentages of maximum suppression from both vaccinated and control groups as described in Materials and Methods. Then, we compared both groups at each E:T ratio. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. *, P < 0.05 according to the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

In vitro suppression of SIV replication did not predict vaccine efficacy.

Thirty-seven weeks after vaccination, we challenged the animals intrarectally with repeated low doses of SIVsmE660 (59). The vaccine did not confer protection against acquisition of SIV infection, since both vaccinees and control animals became infected after an average of four challenges (59). However, it is possible that one vaccinee, r00061, did not become productively infected (59). We detected low levels of viremia in this animal at only three time points. Nevertheless, two independent laboratories could not amplify virus from shipped frozen samples. We found no evidence of viral replication even after depleting this animal's CD8+ cells in vivo with a monoclonal antibody—a treatment that normally causes viral rebound even in animals controlling SIV infection. Therefore, we excluded r00061 from all correlative analyses.

After infection, five of eight vaccinees controlled viral replication to less than 80,000 vRNA copies/ml in the acute phase and to less than 100 vRNA copies/ml in the chronic phase (Table 3) (59). Compared to control animals, this represented a reduction of 1.9 and 2.6 logs in peak and set point viremias, respectively (59). We therefore sought to determine the cellular factors associated with the successful outcome of this vaccine trial.

TABLE 3.

Summary of viral loads and absolute CD4+ T-cell counts for vaccinated animals during both acute and chronic phases

| Animal | Plasma viral loads (vRNA copies/ml)a |

Absolute no. of CD4+ T cells/μl of bloodb |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak viremia | Set point viremia | Acute phase | Chronic phase | |

| r00061 | 220 (2.3) | 0 (0) | 1,122 | 2,868 |

| r01099 | 446,000 (5.6) | 2 (0.3) | 683 | 576 |

| r02089 | 1,390 (3.1) | 0 (0) | 867 | 1,389 |

| r02103 | 302 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 1,026 | 1,728 |

| r02114 | 71,200 (4.9) | 57 (1.8) | 886 | 1,177 |

| r97112 | 8,360 (3.9) | 20 (1.3) | 848 | 1,309 |

| r99063 | 24,100,000 (7.4) | 585,907 (5.8) | 926 | 205 |

| r95116 | 2,000,000 (6.3) | 2,913 (3.5) | 633 | 495 |

Values are given as absolute values, with the log-transformed values in parentheses. Peak viremia was defined as the highest viral load measurement within the first 4 weeks of infection. Set point viremia was defined as the average of log-transformed viral loads at weeks 6 to 24 postinfection.

Acute-phase values were obtained at weeks 2 to 3 postinfection. Chronic-phase values were obtained at week 24 postinfection.

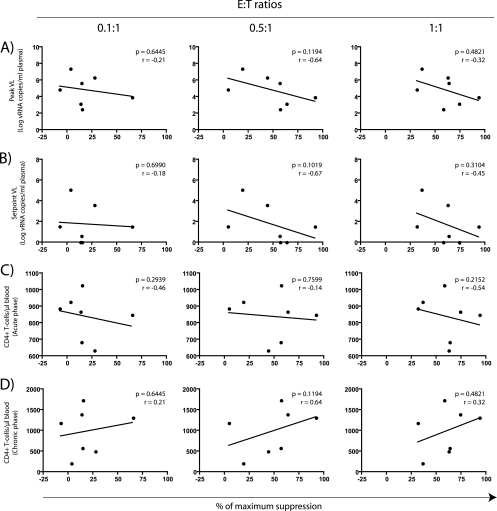

CD8+ T-cell-mediated suppression of viral replication has been suggested to reflect immune control of HIV replication in vivo (47, 55). To test this ability as a surrogate marker for CD8+ T-cell efficacy in our vaccine trial, we compared the percentages of maximum suppression of SIVsmE660 replication (Table 2 and Fig. 3A) with prognostic markers of AIDS progression. The latter markers included peak and set point viral loads, and CD4+ lymphocyte counts measured in both the acute (weeks 2 to 3 postinfection) and chronic (week 24 postinfection) phases of infection (33, 45, 46). We measured correlation between the above variables using the Spearman rank correlation test and plotted the results as scatterplots (Fig. 4). Of note, we also used the Kendall's tau correlation test to analyze these data and obtained similar results (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Comparison between in vitro suppression of SIVsmE660 replication and markers of disease progression. Each symbol represents the mean percentage of maximum suppression from one vaccinee plotted against its corresponding viral load (VLs) (A and B) and absolute CD4+ T-cell counts (C and D). In vitro suppression of viral replication was compared to peak VLs (A), set point VLs (B), absolute CD4+ T-cell counts in the acute phase (weeks 2 to 3 postinfection) (C), and absolute CD4+ T-cell counts in the chronic phase (week 24 postinfection) (D). We determined the correlation coefficients (r) and P values by using the Spearman rank correlation test.

The ability of vaccine-induced CD8+ T cells to suppress replication of the heterologous isolate SIVsmE660 in vitro did not predict vaccine efficacy (Fig. 4). Compared to the animals’ viral loads in both the acute (Fig. 4A) and chronic phases (Fig. 4B), the VSA values at all three E:T ratios yielded no statistically significant correlations. Likewise, in vitro suppression did not associate with the absolute CD4+ T-cell counts obtained in either the acute or chronic phases (Fig. 4C and D). Similarly, we found no correlation between the ability to suppress replication of the homologous clone SIVmac239 and these markers of disease progression (data not shown). Therefore, although vaccine-induced CD8+ T cells suppressed the replication of SIVsmE660 and SIVmac239 in vitro, this ability was not predictive of vaccine efficacy after a heterologous challenge.

Correlations between the magnitude of vaccine-induced responses and markers of disease progression.

Since the VSA values did not predict the outcome of the heterologous challenge, we analyzed pre- and postchallenge T-cell responses and attempted to correlate them with outcome. We measured prechallenge responses on day 14 after the Ad5 boost by carrying out a whole-proteome ELISPOT assay with PBMC from all of the vaccinees. We used 83 pools consisting of ten 15-mers (overlapping by 11 amino acids) spanning the nine SIVmac239 open reading frames. In addition, we mapped as many epitopes as possible to single 15-mers (59). Unfortunately, we did not have sufficient numbers of cells to measure the extent of vaccine-elicited SIV-specific CD4+ T-cell responses. Thus, all ELISPOT data generated before challenge included both CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses.

As shown in Table 4, the vaccinees mounted high-frequency T-cell responses against 11 to 34 epitopes in the vaccine (59). Unexpectedly, all animals developed at least one response against Env even though the vaccine did not encode this protein (Table 4). Further analyses demonstrated that these Env-specific responses were derived from alternate reading frames (ARFs) in the Rev-encoding plasmid and Ad5 vector (38). Of note, we detected no Env-specific antibodies engendered by the vaccine. Importantly, none of these ARF-derived responses against Env correlated with any markers of disease progression in the present study (data not shown).

TABLE 4.

Prechallenge vaccine-induced cellular responses (frequency and breadth) detected in PBMC of vaccineesa

| Parameter (frequency or breadth of response) and animal | Prechallenge vaccine-induced cellular response |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gag | Nef | Tat | Rev | Vpr | Vpx | Vif | Env | Pol | Total | |

| Frequency of vaccine-induced immune responses (SFC/106 PBMC) | ||||||||||

| r02103 | 3,258 | 785 | 0 | 0 | 255 | 60 | 2,675 | 163 | 328 | 7,523 |

| r02114 | 7,183 | 385 | 1,133 | 305 | 63 | 0 | 6,565 | 3,425 | 0 | 19,058 |

| r01099 | 2,745 | 680 | 0 | 1,000 | 303 | 0 | 733 | 1,510 | 1,130 | 8,100 |

| r97112 | 5,720 | 3,365 | 0 | 920 | 725 | 0 | 2,508 | 1,515 | 8,065 | 22,818 |

| r02089 | 8,683 | 218 | 0 | 1,510 | 2,493 | 0 | 1,278 | 1,943 | 4,670 | 20,793 |

| r95116 | 6,120 | 0 | 0 | 1,495 | 143 | 0 | 1,343 | 358 | 170 | 9,628 |

| r99063 | 3,225 | 295 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 358 | 1,235 | 288 | 5,500 |

| Avg | 5,276 | 818 | 162 | 761 | 569 | 9 | 2,209 | 1,450 | 2,093 | 13,346 |

| Median | 5,720 | 385 | 0 | 920 | 255 | 0 | 1,343 | 1,510 | 328 | 9,628 |

| Breadth of vaccine-induced immune responses (no. of unique epitopes) | ||||||||||

| r02103 | 9 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 21 |

| r02114 | 11 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 23 |

| r01099 | 9 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 22 |

| r97112 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 24 |

| r02089 | 13 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 9 | 34 |

| r95116 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 13 |

| r99063 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 11 |

| Avg | 8 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 21 |

| Median | 9 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 22 |

Adapted from Wilson et al. (59). Breadth was defined as the number of single 15-mers for which positive ELISPOT assay responses were observed. An ELISPOT assay was considered positive if it was ≥50 SFC/106 PBMC and ≥2 standard deviations over the background. Prechallenge, measured on day 14 after vaccination.

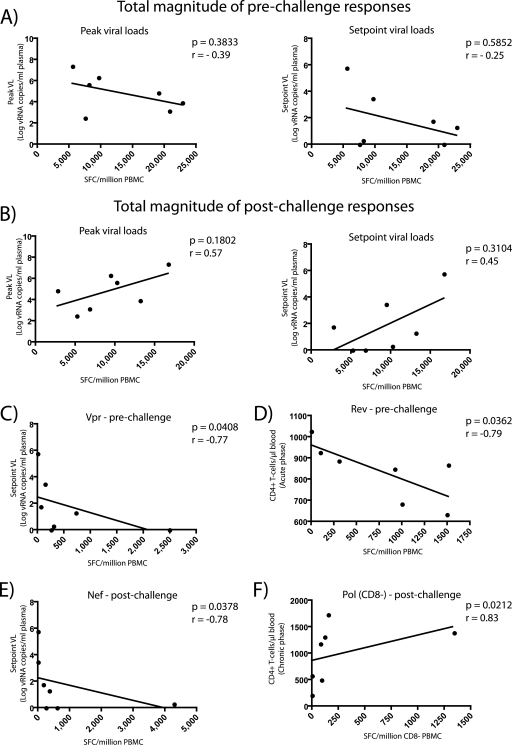

Our analysis revealed that there was no statistically significant correlation between the total magnitude of prechallenge responses and either peak or set point viral loads (Fig. 5A). Nonetheless, vaccine-induced responses directed against Vpr were associated with delayed disease progression. We found an inverse correlation between the magnitude of Vpr-specific T cells and set point viremia (P = 0.0408; r = −0.77) (Fig. 5C). However, the frequency of responses against this protein varied significantly among vaccinees. IFN-γ+ T cells specific for Vpr ranged from 0 to 2,493 SFC/106 PBMC in r99063 and r02089, respectively, compared to a median of 255 SFC/106 PBMC (Table 4).

FIG. 5.

Correlations between the magnitude of vaccine-induced T-cell responses and markers of disease progression. Each symbol represents the magnitude of IFN-γ+ responses from one vaccinee measured before (A, C, and D) or after (B, E, and F) infection. (A) Total magnitude of prechallenge vaccine-induced T-cell responses compared to peak (left panel) and set point (right panel) viral loads (VLs). (B) Total magnitude of postchallenge vaccine-induced T-cell responses compared to peak (left panel) and set point (right panel) viral loads. (C) Prechallenge response to Vpr compared to set point viral loads. (D) Prechallenge response to Rev compared to absolute CD4+ T-cell counts in the acute phase (weeks 2 to 3 postinfection). (E) Postchallenge anamnestic response to Nef compared to set point viral loads. (D) Postchallenge anamnestic CD4+ T-cell response to Pol compared to absolute CD4+ T-cell counts in the chronic phase (week 24 postinfection). We determined the correlation coefficients (r) and P values by using the Spearman rank correlation test. SFC, spot-forming cells.

To our surprise, the magnitude of Rev-directed responses was associated with diminished CD4+ T-cell counts in the acute phase (P = 0.0362; r = −0.79) (Fig. 5D). Responses against this protein had a median of 920 SFC/106 PBMC and ranged from no responses in r02103 to 1,510 SFC/106 PBMC in r02089 (Table 4). Despite this negative association with CD4+ T-cell counts, we did not find any relationship between the frequency of Rev-specific T cells and either peak (P = 0.8790; r = 0.07) or set point (P = 0.7578; r = −0.14) viral loads.

We also studied the anamnestic expansion of vaccine-induced responses after challenge with SIVsmE660. To do that, we performed an IFN-γ ELISPOT assay at approximately 2 weeks after infection, before the expansion of de novo responses against SIVsmE660. Since we were interested in vaccine-elicited responses, we only analyzed responses we had seen after vaccination. Interestingly, only 50% of the vaccine-induced responses expanded after challenge, likely due to the difference in sequence between the vaccine and challenge virus. The magnitude of the entire anamnestic postchallenge T-cell response did not correlate with the peak or set point viral loads (Fig. 5B). However, the magnitude of recall responses directed to Nef inversely correlated with set point viremia (P = 0.0378; r = −0.78) (Fig. 5E). Given a median of 255 SFC/106 PBMC, the anamnestic responses against this protein were highly variable among vaccinees (Table 5). The frequency of Nef-specific IFN-γ+ T cells ranged from no responses in r95116 and r99063 to 4,286 SFC/106 PBMC in r01099 (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Postchallenge anamnestic cellular responses (frequency and breadth) detected in PBMC of vaccineesa

| Parameter (frequency or breadth of response) and animal | Postchallenge anamnestic cellular response |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gag | Nef | Tat | Rev | Vpr | Vpx | Vif | Env | Pol | Total | |

| Frequency of anamnestic immune responses in PBMC (SFC/106 PBMC) | ||||||||||

| r02103 | 2,738 | 600 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 690 | 240 | 912 | 5,180 |

| r02114 | 1,455 | 170 | 205 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 525 | 320 | 100 | 2,775 |

| r01099 | 5,457 | 4,286 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 475 | 0 | 0 | 10,218 |

| r97112 | 11,259 | 360 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1,540 | 13,159 |

| r02089 | 4,890 | 255 | 0 | 205 | 610 | 0 | 0 | 155 | 670 | 6,785 |

| r95116 | 8,532 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 603 | 83 | 215 | 9,433 |

| r99063 | 16,178 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 318 | 0 | 205 | 16,701 |

| Avg | 7,216 | 810 | 29 | 29 | 87 | 0 | 373 | 114 | 520 | 9,179 |

| Median | 5,457 | 255 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 475 | 83 | 215 | 9,433 |

| Frequency of anamnestic immune responses in CD8− PBMC (SFC/106 PBMC) | ||||||||||

| r02103 | 464 | 78 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 78 | 153 | 773 |

| r02114 | 1,960 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 70 | 0 | 80 | 2,110 |

| r01099 | 890 | 0 | 0 | 125 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1,015 |

| r97112 | 1,590 | 0 | 0 | 250 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 120 | 1,960 |

| r02089 | 7,044 | 0 | 137 | 1,236 | 0 | 0 | 751 | 0 | 1,342 | 10,510 |

| r95116 | 405 | 0 | 0 | 110 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 90 | 605 |

| r99063 | 234 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 234 |

| Avg | 1,798 | 11 | 20 | 246 | 0 | 0 | 117 | 11 | 255 | 2,458 |

| Median | 890 | 0 | 0 | 110 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 90 | 1,015 |

| Breadth of anamnestic immune responses in PBMC (no. of unique epitopes) | ||||||||||

| r02103 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 9 |

| r02114 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 14 |

| r01099 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| r97112 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 10 |

| r02089 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 16 |

| r95116 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 9 |

| r99063 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| Avg | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 10 |

| Median | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 9 |

Adapted from Wilson et al. (59). Breadth was defined as the number of single 15-mers for which positive ELISPOT assay responses were observed. An ELISPOT assay was considered positive if it was ≥50 SFC/106 PBMC and ≥2 standard deviations over the background. Postchallenge, measured on day 14 or 15 after infection.

We also performed a CD8-depleted ELISPOT assay to evaluate the expansion of the virus-specific CD4+ T-cell compartment after challenge. We found that IFN-γ+ responses against Pol positively associated with the absolute CD4+ T-cell counts in the chronic phase (P = 0.0212; r = 0.83) (Fig. 5F). However, similar to the Vpr and Nef correlations above, the magnitude of Pol-specific CD4+ T-cell responses varied significantly. Its median was 90 SFC/106 PBMC, and the frequency of responses ranged from no responses in r01099 and r99063 to 1,342 SFC/106 PBMC in r02089 (Table 5).

We also searched for correlations among the frequency of pre- and postchallenge responses directed against combinations of structural, accessory, and regulatory proteins and the outcome of challenge (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). In agreement with these results, we found that T-cell responses targeting combinations of the accessory proteins Vpr, Nef, and Vpx were associated with delayed disease progression (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

In order to maintain the family wise type I error rate no higher than alpha, we applied the Bonferroni correction to our analyses. Although the associations described above for the magnitude of immune responses directed against Vpr, Rev, and Pol were significant at the uncorrected nominal 0.05 level, they did not meet the statistical criterion established by the Bonferroni adjustment (0.0008).

In summary, we found a negative association between the frequency of vaccine-induced Rev-specific responses and CD4+ T-cell counts in the acute phase. In addition, the magnitude of responses against Vpr, Nef, and Pol were associated with delayed disease progression. However, these correlations might not reflect the true role of these responses in SIV infection due to high animal-to-animal variability.

Correlations between the breadth of vaccine-induced responses and markers of disease progression.

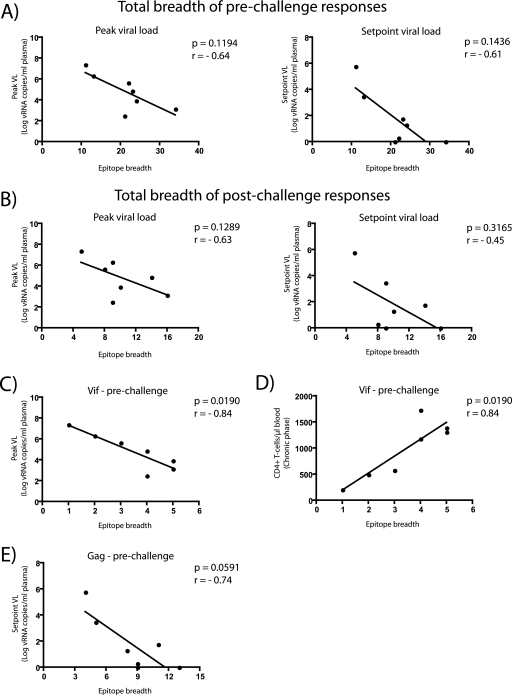

We investigated whether the breadth of the vaccine-induced T-cell responses was associated with any markers of disease progression. There was no statistically significant correlation between the total number of epitopes recognized by each vaccinee and either peak or set point viral loads (Fig. 6A and B). However, we found that the number of Vif epitopes was associated with two markers of delayed disease progression. Animals that targeted more epitopes in this protein had reduced peak viremia (P = 0.0190; r = −0.84) (Fig. 6C) and higher CD4+ T-cell counts in the chronic phase (P = 0.0190; r = 0.84) (Fig. 6D). Of note, these associations were not significant at the Bonferroni-corrected level (0.0008). Importantly, all vaccinees mounted Vif-specific responses, ranging from 1 epitope in r99063 to 5 epitopes in both r97112 and r02089 (Table 4).

FIG. 6.

Correlations between the epitope breadth of vaccine-induced T-cell responses and markers of disease progression. Each symbol represents the epitope breadth of T-cell responses from one vaccinee measured before (A, C, D, and E) or after (B) infection. (A) Total breadth of prechallenge vaccine-induced T-cell responses compared to peak (left panel) and set point (right panel) viral loads (VLs). (B) Total breadth of postchallenge vaccine-induced T-cell responses compared to peak (left panel) or set point (right panel) viral loads. (C) Prechallenge Vif epitope breadth compared to peak VLs. (D) Prechallenge Vif epitope breadth compared to absolute CD4+ T-cell counts in the chronic phase (week 24 postinfection). (E) Prechallenge Gag epitope breadth compared to set point viral loads. We determined the correlation coefficients (r) and P values by using the Spearman rank correlation test.

Broad epitope recognition in Gag was also associated with control of SIV replication (Fig. 6E). Increasing the breadth of prechallenge responses against this protein correlated with lower set point viremia (P = 0.0591; r = −0.74) (Fig. 6E). Despite the borderline P value, this association may be biologically relevant given several other studies demonstrating a protective role for broad Gag-specific responses in the control of chronic HIV (17, 31) and SIV (53) infections. In addition, the number of prechallenge Gag epitopes has recently been correlated with control of chronic phase viral replication in vaccinated macaques that were challenged with SIVmac251 (35).

Correlation analyses with responses targeting combinations of viral proteins yielded several significant associations. The total number of epitopes recognized in Gag and Pol after vaccination was associated with control of viral replication in the chronic phase (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Furthermore, the breadth of responses directed against all accessory proteins was linked to controlled viremia and preservation of CD4+ T-cell counts in the chronic phase. Notably, the number of epitopes in Vif, combined to the number of T-cell responses targeting epitopes in either Vpr or Vpx, correlated with delayed disease progression even at the more strict Bonferroni corrected level (P ≤ 0.0008) (see Table S2 in the supplemental material).

Together, these findings suggest that increasing the breadth of cellular responses against Vif and Gag may contribute to the control of SIV replication. Thus, vaccines that engender broad Gag- and Vif-specific T cells might be useful in controlling AIDS virus replication.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we defined aspects of vaccine-induced cellular responses that correlated with the control of viral replication after a heterologous challenge with the pathogenic swarm virus SIVsmE660 (59). Although we demonstrated that CD8+ T cells from vaccinated animals suppressed replication of both homologous and heterologous viruses in vitro, this ability did not predict viral control in vivo after challenge. We found, however, that broad immune responses against Vif and Gag and high-frequency T-cell responses to Vpr, Nef, and Pol correlated with containment of SIVsmE660 infection.

The notion that broad cellular responses to certain viral proteins may impact control of immunodeficiency virus replication has been proposed before (31). In the present study, we found that broad prechallenge vaccine-induced responses against Gag and Vif were associated with markers of delayed disease progression. The number of epitopes in Vif, in particular, correlated with higher CD4+ T-cell counts in the chronic phase and lower peak viral loads. Achieving the latter result would be greatly desired for a T-cell-based AIDS vaccine, since limiting viral replication in the acute phase would alleviate the damage to the gut CD4+ T-cell memory compartment that occurs in this stage of infection (34, 42). To our knowledge, this is the first report to implicate vaccine-induced cellular immune responses against Vif in the containment of SIV infection. The prechallenge epitope breadth in Gag also correlated with a marker of delayed disease progression. Vaccinees that mounted broad responses against this protein had lower set point viral loads, although the P value for this correlation (P = 0.0591) was slightly greater than the 0.05 threshold of statistical significance. However, this finding agrees with previous studies showing that Gag-specific responses elicited by vaccination were associated with control of chronic phase viral replication (25, 26, 35). Thus, our results indicate that cellular immune responses targeting Gag and Vif might be particularly efficient at containing viral replication after a heterologous SIV challenge.

Several studies have attempted to identify associations between the magnitude of HIV-1-specific responses and markers of disease progression (9, 17, 23, 39). These studies have generated variable results, and no particular pattern of responses is consistently associated with delayed disease progression. In our cohort of vaccinated Indian rhesus macaques, we found that lower set point viral loads correlated with two aspects of vaccine-induced immune responses: (i) the frequency of prechallenge responses to Vpr and (ii) the magnitude of postchallenge Nef-specific responses. The latter finding is consistent with a recent report showing that the magnitude of postchallenge responses to Nef inversely correlated with set point viral loads in vaccinated macaques challenged with SHIV89.6P (32). Furthermore, Vpr has been suggested as a preferential target of cytotoxic T lymphocytes in natural HIV-1 infection, although its role on the control of viral replication is unknown (3). We also found that the anamnestic CD4+ T-cell response to Pol correlated with the preservation of CD4+ T-cell counts in the chronic phase. This result agrees with the notion that virus-specific T-helper responses actively participate in the control of immunodeficiency virus infection (25, 50, 54). Nonetheless, the animal-to-animal variability in the frequency of IFN-γ+ T cells against Vpr, Nef, and Pol among vaccinees was high, which makes it difficult to interpret these results. With a sample size limited to seven vaccinees, the presence of outliers in these correlations may have affected the predictive value of these comparisons. Therefore, more studies will be required to determine the precise role of vaccine-induced responses to Vpr, Nef, and Pol in the control of SIV infection.

Our analyses also indicate that the prechallenge magnitude of Rev-specific IFN-γ-secreting T cells inversely correlated with absolute CD4+ lymphocyte counts in the acute phase. However, RNA viral load has been suggested to carry more prognostic value than CD4+ lymphocyte counts early in the infection (33). Since we found no correlation between the frequency of T cells targeting Rev and either peak or set point viral loads, it is unlikely that cellular responses to this protein accelerated the progression to AIDS.

Measuring the ability of CD8+ T cells to suppress viral replication has been proposed as a relevant readout for immune control of HIV-1 (18). Recently, two groups have shown that CD8+ T cells from elite controllers suppress HIV-1 replication more efficiently than those of progressors (47, 55). These findings are encouraging in that they begin to shed light on the mechanism of elite control and thus may be useful for the screening of efficient HIV-1-specific responses after vaccination. Using this rationale, we explored whether the ability of prechallenge vaccine-elicited CD8+ T cells to suppress SIV replication in vitro would predict how well vaccinees controlled viral replication after challenge. CD8+ T cells from vaccinated animals suppressed the replication of both SIVmac239, the virus whose sequence is identical to the one used in the vaccine, and SIVsmE660, the heterologous virus used for the challenge. Although suppression among vaccinees was heterogeneous, this measurement did not correlate with any prognostic markers of progression to AIDS. Therefore, suppression of viral replication in vitro by vaccine-elicited CD8+ T cells did not predict the efficacy of a T-cell-based vaccine against SIV.

Two factors likely interfered with the comparisons between the VSA values and markers of disease progression. The first was our sample size (n = 7 vaccinees), which might not have been large enough for the detection of statistically significant differences, especially given the complexity of CD8+ T-lymphocyte-mediated antiviral immunity (4, 60). Characteristics of the swarm virus SIVsmE660 and the low-dose challenge route used in this vaccine trial may also have hampered our ability to correlate virus suppression and vaccine challenge outcome (59). Recent studies have shown that productive HIV-1 infection across a mucosal surface is initiated by one or a few viral quasispecies (29). To mimic these human HIV-1 exposures, we challenged the animals intrarectally with repeated low doses of SIVsmE660 (30, 59). By using a titrated inoculum, both control and vaccinated animals became infected by one or a few SIVsmE660 viral variants (59). In contrast, the targets used in the VSAs were exposed to the entire diversity of viral variants present in our SIVsmE660 stock and likely at a higher multiplicity of infection. Thus, we likely measured in vitro suppression of a multitude of quasispecies whose replicative fitness may not directly compare to those of the few variants that established infection in the animals.

The lack of significant correlations between in vitro suppression of viral replication and the outcome of challenge with SIVsmE660 may also be explained by the use of blood-derived CD8+ T cells in the VSAs. Evaluating cellular immune responses from peripheral blood is convenient because of the ease in obtaining samples from this compartment. However, circulating T cells might not be functionally equivalent to those present in mucosa-associated lymphoid tissues, where viral replication is concentrated (5, 6, 19, 24, 40). In elite controllers, for example, mucosal CD8+ T-cell responses to HIV-1 have been shown to be more “polyfunctional” than those measured in blood (19). Furthermore, the presence of virus-specific CD8+ T cells in colonic lamina propria, but not in blood, has been correlated with delayed disease progression in vaccinated macaques challenged intrarectally with SHIV-ku2 (6). Therefore, assays that measure the antiviral function of mucosa-residing CD8+ T cells might provide a more accurate approximation of the host cellular responses against the virus.

In summary, the goal of the present study was to identify the correlates of protection in vaccinated macaques that controlled viral replication after a heterologous SIV challenge (59). We found that the ability of vaccine-induced CD8+ T cells to suppress viral replication in vitro did not predict viral containment in vivo. Nevertheless, we found that broad cellular immune responses directed to Gag and Vif predicted the efficacy of a T-cell-based vaccine against a heterologous SIV challenge. This knowledge may provide a rationale for the selection of immunogens that will be included in future T-cell-based AIDS vaccines.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. R. Reynolds for helpful discussions and T. C. Friedrich and J. T. Loffredo for help in reviewing the manuscript. Interleukin-2 was kindly provided by the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program (Germantown, MD).

D.I.W. and his laboratory are supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (grants R01 AI049120, R37 AI052056, R01 AI076114, R24 RR015371, R24 RR016038, and R21 AI077472; contract HHSN266200400088C). This publication was made possible in part by P51 RR000167 from the Wisconsin National Primate Research Center. This research was conducted at a facility constructed with support from the Research Facilities Improvement Program grants RR15459-01 and RR020141-01 and was also supported by grants from the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 17 February 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jvi.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Addo, M. M., X. G. Yu, A. Rathod, D. Cohen, R. L. Eldridge, D. Strick, M. N. Johnston, C. Corcoran, A. G. Wurcel, C. A. Fitzpatrick, M. E. Feeney, W. R. Rodriguez, N. Basgoz, R. Draenert, D. R. Stone, C. Brander, P. J. Goulder, E. S. Rosenberg, M. Altfeld, and B. D. Walker. 2003. Comprehensive epitope analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-specific T-cell responses directed against the entire expressed HIV-1 genome demonstrate broadly directed responses, but no correlation to viral load. J. Virol. 77:2081-2092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen, T. M., M. Altfeld, S. C. Geer, E. T. Kalife, C. Moore, K. M. O'sullivan, I. Desouza, M. E. Feeney, R. L. Eldridge, E. L. Maier, D. E. Kaufmann, M. P. Lahaie, L. Reyor, G. Tanzi, M. N. Johnston, C. Brander, R. Draenert, J. K. Rockstroh, H. Jessen, E. S. Rosenberg, S. A. Mallal, and B. D. Walker. 2005. Selective escape from CD8+ T-cell responses represents a major driving force of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) sequence diversity and reveals constraints on HIV-1 evolution. J. Virol. 79:13239-13249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altfeld, M., M. M. Addo, R. L. Eldridge, X. G. Yu, S. Thomas, A. Khatri, D. Strick, M. N. Phillips, G. B. Cohen, S. A. Islam, S. A. Kalams, C. Brander, P. J. Goulder, E. S. Rosenberg, and B. D. Walker. 2001. Vpr is preferentially targeted by CTL during HIV-1 infection. J. Immunol. 167:2743-2752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Appay, V., D. C. Douek, and D. A. Price. 2008. CD8+ T-cell efficacy in vaccination and disease. Nat. Med. 14:623-628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belyakov, I. M., and J. D. Ahlers. 2008. Functional CD8+ CTLs in mucosal sites and HIV infection: moving forward toward a mucosal AIDS vaccine. Trends Immunol. 29:574-585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belyakov, I. M., V. A. Kuznetsov, B. Kelsall, D. Klinman, M. Moniuszko, M. Lemon, P. D. Markham, R. Pal, J. D. Clements, M. G. Lewis, W. Strober, G. Franchini, and J. A. Berzofsky. 2006. Impact of vaccine-induced mucosal high-avidity CD8+ CTLs in delay of AIDS viral dissemination from mucosa. Blood 107:3258-3264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bennett, M. S., H. L. Ng, A. Ali, and O. O. Yang. 2008. Cross-clade detection of HIV-1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes does not reflect cross-clade antiviral activity. J. Infect. Dis. 197:390-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bennett, M. S., H. L. Ng, M. Dagarag, A. Ali, and O. O. Yang. 2007. Epitope-dependent avidity thresholds for cytotoxic T-lymphocyte clearance of virus-infected cells. J. Virol. 81:4973-4980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Betts, M. R., D. R. Ambrozak, D. C. Douek, S. Bonhoeffer, J. M. Brenchley, J. P. Casazza, R. A. Koup, and L. J. Picker. 2001. Analysis of total human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses: relationship to viral load in untreated HIV infection. J. Virol. 75:11983-11991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Betts, M. R., M. C. Nason, S. M. West, S. C. De Rosa, S. A. Migueles, J. Abraham, M. M. Lederman, J. M. Benito, P. A. Goepfert, M. Connors, M. Roederer, and R. A. Koup. 2006. HIV nonprogressors preferentially maintain highly functional HIV-specific CD8+ T cells. Blood 107:4781-4789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buchbinder, S. P., D. V. Mehrotra, A. Duerr, D. W. Fitzgerald, R. Mogg, D. Li, P. B. Gilbert, J. R. Lama, M. Marmor, C. Del Rio, M. J. McElrath, D. R. Casimiro, K. M. Gottesdiener, J. A. Chodakewitz, L. Corey, and M. N. Robertson. 2008. Efficacy assessment of a cell-mediated immunity HIV-1 vaccine (the Step Study): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, test-of-concept trial. Lancet 372:1881-1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carrington, M., and S. J. O'Brien. 2003. The influence of HLA genotype on AIDS. Annu. Rev. Med. 54:535-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casimiro, D. R., F. Wang, W. A. Schleif, X. Liang, Z. Q. Zhang, T. W. Tobery, M. E. Davies, A. B. McDermott, D. H. O'Connor, A. Fridman, A. Bagchi, L. G. Tussey, A. J. Bett, A. C. Finnefrock, T. M. Fu, A. Tang, K. A. Wilson, M. Chen, H. C. Perry, G. J. Heidecker, D. C. Freed, A. Carella, K. S. Punt, K. J. Sykes, L. Huang, V. I. Ausensi, M. Bachinsky, U. Sadasivan-Nair, D. I. Watkins, E. A. Emini, and J. W. Shiver. 2005. Attenuation of simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac239 infection by prophylactic immunization with DNA and recombinant adenoviral vaccine vectors expressing Gag. J. Virol. 79:15547-15555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chung, C., W. Lee, J. T. Loffredo, B. Burwitz, T. C. Friedrich, J. P. Giraldo Vela, G. Napoe, E. G. Rakasz, N. A. Wilson, D. B. Allison, and D. I. Watkins. 2007. Not all cytokine-producing CD8+ T cells suppress simian immunodeficiency virus replication. J. Virol. 81:1517-1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Rosa, S. D., and M. J. McElrath. 2008. T-cell responses generated by HIV vaccines in clinical trials. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS. 3:375-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Desrosiers, R. C. 2004. Prospects for an AIDS vaccine. Nat. Med. 10:221-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edwards, B. H., A. Bansal, S. Sabbaj, J. Bakari, M. J. Mulligan, and P. A. Goepfert. 2002. Magnitude of functional CD8+ T-cell responses to the gag protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 correlates inversely with viral load in plasma. J. Virol. 76:2298-2305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fauce, S. R., O. O. Yang, and R. B. Effros. 2007. Autologous CD4/CD8 coculture assay: a physiologically-relevant composite measure of CD8+ T lymphocyte function in HIV-infected persons. J. Immunol. Methods 327:75-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferre, A. L., P. W. Hunt, J. W. Critchfield, D. H. Young, M. M. Morris, J. C. Garcia, R. B. Pollard, H. F. J. Yee, J. N. Martin, S. G. Deeks, and B. L. Shacklett. 2009. Mucosal immune responses to HIV-1 in elite controllers: a potential correlate of immune control. Blood 113:3978-3989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Friedrich, T. C., L. E. Valentine, L. J. Yant, E. G. Rakasz, S. M. Piaskowski, J. R. Furlott, K. L. Weisgrau, B. Burwitz, G. E. May, E. J. Leon, T. Soma, G. Napoe, S. V. R. Capuano, N. A. Wilson, and D. I. Watkins. 2007. Subdominant CD8+ T-cell responses are involved in durable control of AIDS virus replication. J. Virol. 81:3465-3476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaschen, B., J. Taylor, K. Yusim, B. Foley, F. Gao, D. Lang, V. Novitsky, B. Haynes, B. H. Hahn, T. Bhattacharya, and B. Korber. 2002. Diversity considerations in HIV-1 vaccine selection. Science 296:2354-2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goulder, P. J., and D. I. Watkins. 2008. Impact of MHC class I diversity on immune control of immunodeficiency virus replication. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8:619-630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gray, C. M., M. Mlotshwa, C. Riou, T. Mathebula, D. de Assis Rosa, T. Mashishi, C. Seoighe, N. Ngandu, F. van Loggerenberg, L. Morris, K. Mlisana, C. Williamson, and S. A. Karim. 2009. Human immunodeficiency virus-specific gamma interferon enzyme-linked immunospot assay responses targeting specific regions of the proteome during primary subtype C infection are poor predictors of the course of viremia and set point. J. Virol. 83:470-478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greene, J. M., J. J. Lhost, B. J. Burwitz, M. L. Budde, C. E. Macnair, M. K. Weiker, E. Gostick, T. C. Friedrich, K. W. Broman, D. A. Price, S. O'Connor, and D. H. O'Connor. 2010. Extra-lymphoid tissue-resident CD8+ T cells from SIVmac239Δnef-vaccinated macaques suppress SIVmac239 replication ex vivo. J. Virol. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02028-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Hel, Z., J. Nacsa, E. Tryniszewska, W. P. Tsai, R. W. Parks, D. C. Montefiori, B. K. Felber, J. Tartaglia, G. N. Pavlakis, and G. Franchini. 2002. Containment of simian immunodeficiency virus infection in vaccinated macaques: correlation with the magnitude of virus-specific pre- and postchallenge CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses. J. Immunol. 169:4778-4787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hel, Z., W. P. Tsai, E. Tryniszewska, J. Nacsa, P. D. Markham, M. G. Lewis, G. N. Pavlakis, B. K. Felber, J. Tartaglia, and G. Franchini. 2006. Improved vaccine protection from simian AIDS by the addition of nonstructural simian immunodeficiency virus genes. J. Immunol. 176:85-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jin, X., D. E. Bauer, S. E. Tuttleton, S. Lewin, A. Gettie, J. Blanchard, C. E. Irwin, J. T. Safrit, J. Mittler, L. Weinberger, L. G. Kostrikis, L. Zhang, A. S. Perelson, and D. D. Ho. 1999. Dramatic rise in plasma viremia after CD8+ T-cell depletion in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. J. Exp. Med. 189:991-998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaizu, M., G. J. Borchardt, C. E. Glidden, D. L. Fisk, J. T. Loffredo, D. I. Watkins, and W. M. Rehrauer. 2007. Molecular typing of major histocompatibility complex class I alleles in the Indian rhesus macaque which restrict SIV CD8+ T-cell epitopes. Immunogenetics 59:693-703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keele, B. F., E. E. Giorgi, J. F. Salazar-Gonzalez, J. M. Decker, K. T. Pham, M. G. Salazar, C. Sun, T. Grayson, S. Wang, H. Li, X. Wei, C. Jiang, J. L. Kirchherr, F. Gao, J. A. Anderson, L. H. Ping, R. Swanstrom, G. D. Tomaras, W. A. Blattner, P. A. Goepfert, J. M. Kilby, M. S. Saag, E. L. Delwart, M. P. Busch, M. S. Cohen, D. C. Montefiori, B. F. Haynes, B. Gaschen, G. S. Athreya, H. Y. Lee, N. Wood, C. Seoighe, A. S. Perelson, T. Bhattacharya, B. T. Korber, B. H. Hahn, and G. M. Shaw. 2008. Identification and characterization of transmitted and early founder virus envelopes in primary HIV-1 infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:7552-7557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keele, B. F., H. Li, G. H. Learn, P. Hraber, E. E. Giorgi, T. Grayson, C. Sun, Y. Chen, W. W. Yeh, N. L. Letvin, J. R. Mascola, G. J. Nabel, B. F. Haynes, T. Bhattacharya, A. S. Perelson, B. T. Korber, B. H. Hahn, and G. M. Shaw. 2009. Low-dose rectal inoculation of rhesus macaques by SIVsmE660 or SIVmac251 recapitulates human mucosal infection by HIV-1. J. Exp. Med. 206:1117-1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kiepiela, P., K. Ngumbela, C. Thobakgale, D. Ramduth, I. Honeyborne, E. Moodley, S. Reddy, C. de Pierres, Z. Mncube, N. Mkhwanazi, K. Bishop, M. van der Stok, K. Nair, N. Khan, H. Crawford, R. Payne, A. Leslie, J. Prado, A. Prendergast, J. Frater, N. McCarthy, C. Brander, G. H. Learn, D. Nickle, C. Rousseau, H. Coovadia, J. I. Mullins, D. Heckerman, B. D. Walker, and P. Goulder. 2007. CD8+ T-cell responses to different HIV proteins have discordant associations with viral load. Nat. Med. 13:46-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koopman, G., D. Mortier, S. Hofman, N. Mathy, M. Koutsoukos, P. Ertl, P. Overend, C. van Wely, L. L. Thomsen, B. Wahren, G. Voss, and J. L. Heeney. 2008. Immune-response profiles induced by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vaccine DNA, protein or mixed-modality immunization: increased protection from pathogenic simian-human immunodeficiency virus viraemia with protein/DNA combination. J. Gen. Virol. 89:540-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Korenromp, E. L., B. G. Williams, G. P. Schmid, and C. Dye. 2009. Clinical prognostic value of RNA viral load and CD4 cell counts during untreated HIV-1 infection: a quantitative review. PLoS One 4:e5950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li, Q., L. Duan, J. D. Estes, Z. M. Ma, T. Rourke, Y. Wang, C. Reilly, J. Carlis, C. J. Miller, and A. T. Haase. 2005. Peak SIV replication in resting memory CD4+ T cells depletes gut lamina propria CD4+ T cells. Nature 434:1148-1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu, J., K. L. O'Brien, D. M. Lynch, N. L. Simmons, A. La Porte, A. M. Riggs, P. Abbink, R. T. Coffey, L. E. Grandpre, M. S. Seaman, G. Landucci, D. N. Forthal, D. C. Montefiori, A. Carville, K. G. Mansfield, M. J. Havenga, M. G. Pau, J. Goudsmit, and D. H. Barouch. 2009. Immune control of an SIV challenge by a T-cell-based vaccine in rhesus monkeys. Nature 457:87-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Loffredo, J. T., J. Maxwell, Y. Qi, C. E. Glidden, G. J. Borchardt, T. Soma, A. T. Bean, D. R. Beal, N. A. Wilson, W. M. Rehrauer, J. D. Lifson, M. Carrington, and D. I. Watkins. 2007. Mamu-B*08-positive macaques control simian immunodeficiency virus replication. J. Virol. 81:8827-8832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Loffredo, J. T., E. G. Rakasz, J. P. Giraldo, S. P. Spencer, K. K. Grafton, S. R. Martin, G. Napoe, L. J. Yant, N. A. Wilson, and D. I. Watkins. 2005. Tat(28-35)SL8-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes are more effective than Gag(181-189)CM9-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes at suppressing simian immunodeficiency virus replication in a functional in vitro assay. J. Virol. 79:14986-14991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maness, N. J., N. A. Wilson, J. S. Reed, S. M. Piaskowski, J. B. Sacha, A. D. Walsh, E. Thoryk, G. J. Heidecker, M. P. Citron, X. Liang, A. J. Bett, D. R. Casimiro, and D. I. Watkins. Robust, vaccine-induced CD8+ T lymphocyte response against an out of frame epitope. J. Immunol. 184:67-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Masemola, A., T. Mashishi, G. Khoury, P. Mohube, P. Mokgotho, E. Vardas, M. Colvin, L. Zijenah, D. Katzenstein, R. Musonda, S. Allen, N. Kumwenda, T. Taha, G. Gray, J. McIntyre, S. A. Karim, H. W. Sheppard, and C. M. Gray. 2004. Hierarchical targeting of subtype C human immunodeficiency virus type 1 proteins by CD8+ T cells: correlation with viral load. J. Virol. 78:3233-3243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Masopust, D., V. Vezys, E. J. Wherry, D. L. Barber, and R. Ahmed. 2006. Cutting edge: gut microenvironment promotes differentiation of a unique memory CD8 T-cell population. J. Immunol. 176:2079-2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matano, T., R. Shibata, C. Siemon, M. Connors, H. C. Lane, and M. A. Martin. 1998. Administration of an anti-CD8 monoclonal antibody interferes with the clearance of chimeric simian/human immunodeficiency virus during primary infections of rhesus macaques. J. Virol. 72:164-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mattapallil, J. J., D. C. Douek, B. Hill, Y. Nishimura, M. Martin, and M. Roederer. 2005. Massive infection and loss of memory CD4+ T cells in multiple tissues during acute SIV infection. Nature 434:1093-1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McDermott, A. B., J. Mitchen, S. Piaskowski, I. De Souza, L. J. Yant, J. Stephany, J. Furlott, and D. I. Watkins. 2004. Repeated low-dose mucosal simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac239 challenge results in the same viral and immunological kinetics as high-dose challenge: a model for the evaluation of vaccine efficacy in nonhuman primates. J. Virol. 78:3140-3144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McElrath, M. J., S. C. De Rosa, Z. Moodie, S. Dubey, L. Kierstead, H. Janes, O. D. Defawe, D. K. Carter, J. Hural, R. Akondy, S. P. Buchbinder, M. N. Robertson, D. V. Mehrotra, S. G. Self, L. Corey, J. W. Shiver, and D. R. Casimiro. 2008. HIV-1 vaccine-induced immunity in the test-of-concept Step Study: a case-cohort analysis. Lancet 372:1894-1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mellors, J. W., A. Munoz, J. V. Giorgi, J. B. Margolick, C. J. Tassoni, P. Gupta, L. A. Kingsley, J. A. Todd, A. J. Saah, R. Detels, J. P. Phair, and C. R. J. Rinaldo. 1997. Plasma viral load and CD4+ lymphocytes as prognostic markers of HIV-1 infection. Ann. Intern. Med. 126:946-954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mellors, J. W., C. R. J. Rinaldo, P. Gupta, R. M. White, J. A. Todd, and L. A. Kingsley. 1996. Prognosis in HIV-1 infection predicted by the quantity of virus in plasma. Science 272:1167-1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Migueles, S. A., C. M. Osborne, C. Royce, A. A. Compton, R. P. Joshi, K. A. Weeks, J. E. Rood, A. M. Berkley, J. B. Sacha, N. A. Cogliano-Shutta, M. Lloyd, G. Roby, R. Kwan, M. McLaughlin, S. Stallings, C. Rehm, M. A. O'Shea, J. Mican, B. Z. Packard, A. Komoriya, S. Palmer, A. P. Wiegand, F. Maldarelli, J. M. Coffin, J. W. Mellors, C. W. Hallahan, D. A. Follman, and M. Connors. 2008. Lytic granule loading of CD8+ T cells is required for HIV-infected cell elimination associated with immune control. Immunity 29:1009-1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.O'Doherty, U., W. J. Swiggard, and M. H. Malim. 2000. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 spinoculation enhances infection through virus binding. J. Virol. 74:10074-10080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peut, V., and S. J. Kent. 2007. Utility of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope as a T-cell immunogen. J. Virol. 81:13125-13134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ramduth, D., C. L. Day, C. F. Thobakgale, N. P. Mkhwanazi, C. de Pierres, S. Reddy, M. van der Stok, Z. Mncube, K. Nair, E. S. Moodley, D. E. Kaufmann, H. Streeck, H. M. Coovadia, P. Kiepiela, P. J. Goulder, and B. D. Walker. 2009. Immunodominant HIV-1 CD4+ T-cell epitopes in chronic untreated clade C HIV-1 infection. PLoS One 4:e5013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reynolds, M. R., A. M. Weiler, K. L. Weisgrau, S. M. Piaskowski, J. R. Furlott, J. T. Weinfurter, M. Kaizu, T. Soma, E. J. Leon, C. MacNair, D. P. Leaman, M. B. Zwick, E. Gostick, S. K. Musani, D. A. Price, T. C. Friedrich, E. G. Rakasz, N. A. Wilson, A. B. McDermott, R. Boyle, D. B. Allison, D. R. Burton, W. C. Koff, and D. I. Watkins. 2008. Macaques vaccinated with live-attenuated SIV control replication of heterologous virus. J. Exp. Med. 205:2537-2550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rolland, M., D. Heckerman, W. Deng, C. M. Rousseau, H. Coovadia, K. Bishop, P. J. Goulder, B. D. Walker, C. Brander, and J. I. Mullins. 2008. Broad and Gag-biased HIV-1 epitope repertoires are associated with lower viral loads. PLoS One 3:e1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sacha, J. B., C. Chung, E. G. Rakasz, S. P. Spencer, A. K. Jonas, A. T. Bean, W. Lee, B. J. Burwitz, J. J. Stephany, J. T. Loffredo, D. B. Allison, S. Adnan, A. Hoji, N. A. Wilson, T. C. Friedrich, J. D. Lifson, O. O. Yang, and D. I. Watkins. 2007. Gag-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes recognize infected cells before AIDS-virus integration and viral protein expression. J. Immunol. 178:2746-2754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sacha, J. B., J. P. Giraldo-Vela, M. B. Buechler, M. A. Martins, N. J. Maness, C. Chung, L. T. Wallace, E. J. Leon, T. C. Friedrich, N. A. Wilson, A. Hiraoka, and D. I. Watkins. 2009. Gag- and Nef-specific CD4+ T cells recognize and inhibit SIV replication in infected macrophages early after infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:9791-9796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saez-Cirion, A., C. Lacabaratz, O. Lambotte, P. Versmisse, A. Urrutia, F. Boufassa, F. Barre-Sinoussi, J. F. Delfraissy, M. Sinet, G. Pancino, and A. Venet. 2007. HIV controllers exhibit potent CD8 T-cell capacity to suppress HIV infection ex vivo and peculiar cytotoxic T lymphocyte activation phenotype. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:6776-6781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Seder, R. A., P. A. Darrah, and M. Roederer. 2008. T-cell quality in memory and protection: implications for vaccine design. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8:247-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Valentine, L. E., S. M. Piaskowski, E. G. Rakasz, N. L. Henry, N. A. Wilson, and D. I. Watkins. 2008. Recognition of escape variants in ELISPOT does not always predict CD8+ T-cell recognition of simian immunodeficiency virus-infected cells expressing the same variant sequences. J. Virol. 82:575-581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Watkins, D. I. 2008. The hope for an HIV vaccine based on induction of CD8+ T lymphocytes: a review. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 103:119-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wilson, N. A., B. F. Keele, J. S. Reed, S. M. Piaskowski, C. E. MacNair, A. J. Bett, X. Liang, F. Wang, E. Thoryk, G. J. Heidecker, M. P. Citron, L. Huang, J. Lin, S. Vitelli, C. D. Ahn, M. Kaizu, N. J. Maness, M. R. Reynolds, T. C. Friedrich, J. T. Loffredo, E. G. Rakasz, S. Erickson, D. B. Allison, M. J. Piatak, J. D. Lifson, J. W. Shiver, D. R. Casimiro, G. M. Shaw, B. H. Hahn, and D. I. Watkins. 2009. Vaccine-induced cellular responses control simian immunodeficiency virus replication after heterologous challenge. J. Virol. 83:6508-6521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yang, O. O. 2003. Will we be able to ‘spot’ an effective HIV-1 vaccine? Trends Immunol. 24:67-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yang, O. O. 2008. Retracing our STEP toward a successful CTL-based HIV-1 vaccine. Vaccine 26:3138-3141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yant, L. J., T. C. Friedrich, R. C. Johnson, G. E. May, N. J. Maness, A. M. Enz, J. D. Lifson, D. H. O'Connor, M. Carrington, and D. I. Watkins. 2006. The high-frequency major histocompatibility complex class I allele Mamu-B*17 is associated with control of simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac239 replication. J. Virol. 80:5074-5077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang, Z. Q., T. M. Fu, D. R. Casimiro, M. E. Davies, X. Liang, W. A. Schleif, L. Handt, L. Tussey, M. Chen, A. Tang, K. A. Wilson, W. L. Trigona, D. C. Freed, C. Y. Tan, M. Horton, E. A. Emini, and J. W. Shiver. 2002. Mamu-A*01 allele-mediated attenuation of disease progression in simian-human immunodeficiency virus infection. J. Virol. 76:12845-12854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.