Abstract

Background and objectives: The objective of this study was to describe the prevalence of ocular fundus pathology in the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) study, a multicenter, longitudinal study of individuals with varying stages of chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Design, setting, participants, & measurements: In this cross-sectional study, 45° digital photos of the disc and macula in both eyes were obtained by nonophthalmologic personnel using a nonmydriatic Canon CR-DGI fundus camera in 1936 individuals who participated in the CRIC study. Photographs were assessed in a masked manner by graders and a retinal specialist at a central photograph reading center. The purpose of this review was to inform participants quickly of conditions that warranted a complete eye examination by an ophthalmologist.

Results: Among the 1936 participants who were photographed, 1904 (98%) had assessable photographs in at least one eye. Eye pathologies that required a follow-up examination by an ophthalmologist were identified in 864 (45%) of these 1904 participants. These eye pathologies included, among others, retinopathy (diabetic and/or hypertensive), a finding that was observed in 482 (25%) of these 1904 participants. Three percent (65 participants) of the 1904 participants had serious eye conditions that required urgent follow-up and treatment. Lower estimated GFR and cardiovascular disease were associated with greater eye pathology. Estimated GFR <30 ml/min per 1.73 m2 was associated with a three times higher risk for retinopathy.

Conclusions: We found a high prevalence of fundus pathology in participants with CKD. This finding supports recommendations for regular complete eye examinations in the CKD population.

Renal microvascular pathology is thought to play an important role in the development of renal insufficiency. The assessment of renal vascular pathology requires invasive procedures. The retinal vasculature, conversely, can be observed noninvasively in humans and therefore offers a unique opportunity to explore the association between systemic microvascular disease and renal function. In addition, several studies have shown correlations between retinopathy and nephropathy changes in diabetes (1–6), in systemic hypertension (7,8), and in individuals without these two conditions (7).

A report from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study (7) demonstrated a strong association between retinopathy features and renal dysfunction that was independent of age, diabetes, hypertension, and other risk factors. Recent reports have also shown associations between renal disease and age-related macular degeneration (9–11).

To look into the association between retinal pathology and chronic kidney disease (CKD), a life-threatening condition that affects more than 10 million Americans (12), we are carrying out the Retinopathy in Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (RCRIC) study, an ancillary investigation to the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) study, a multicenter, observational longitudinal cohort study of adults with chronic renal insufficiency (13,14). The principal goals of the CRIC study are to examine risk factors for progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and cardiovascular disease (CVD) among participants with varying severity of CKD.

To investigate in more detail the relationship between ocular vascular pathology and CKD, the RCRIC investigators obtained fundus photographs of 1936 CRIC participants. Because of the increased risk for fundus pathology in these participants with CKD (1,7,11), a rapid clinic assessment of the photographs was performed upon receipt at the photography reading center. The purpose was to provide timely feedback to the clinical sites and the participants regarding fundus abnormalities that warranted follow-up with a complete eye examination by an ophthalmologist. The results of this review of the photographs are summarized in this report. We are assessing and quantifying in detail the retinal pathology and will report on this subject in the near future.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

Details of the design of the CRIC study have been previously reported (13,14). Participants in RCRIC were recruited from six of the seven CRIC clinical centers. Tulane University declined participation in our study. Because of budget constrains, only six fundus cameras were available. These six cameras were placed in the remaining CRIC participating institutions with larger numbers of CRIC participants. All CRIC participants from these six sites were eligible for this study. The following numbers of participants were photographed at each center: University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, PA), 417; University of Maryland (Baltimore, MD), 205; Case Western Reserve University (Cleveland, OH), 226; University of Michigan (Ann Arbor, MI), 305; University of Illinois (Chicago, IL), 349; and Kaiser Permanente, Oakland/University of California (San Francisco, CA), 434. This study followed the precepts of the Declaration of Helsinki.

In this cross-sectional study, CRIC participants were recruited for the RCRIC ancillary study at regular CRIC annual visits. Participants were asked to sign a consent form approved by the institutional review boards of the participating institutions. The CRIC definitions of CKD, diabetes, and systemic hypertension were used and estimated GFR (eGFR) was calculated as follows: eGFR = 186 × (serum creatinine [mg/dl])−1.154 × age −0.203 × 0.742 (if female) × 1.212 (if black) (13,14).

Photography

Photographs were taken by trained and certified CRIC study coordinators. Most photography sessions coincided with the CRIC annual visits. To standardize the competency of the personnel responsible for taking RCRIC photographs, the CRIC clinic coordinators, who were not ophthalmic photographers, were certified by the RCRIC Fundus Photograph Reading Center. The certification requirements included attending a day-long photography training meeting at the RCRIC Reading Center and successful completion of a written as well as a hands-on proficiency test.

Participants were seated in front of the fundus camera. Room light levels were reduced for a 5-minute period to induce a physiologic dilation of the pupils. No pharmacologic compounds were used to achieve pupillary dilation. A Canon CR-DGI, Non-Mydriatic Retinal Camera (Canon Inc., Tokyo, Japan) was used to obtain 45° digital, color fundus photographs. A set of two images was obtained from each eye. One image was centered on the macula and the other was centered on the optic disc. A participant was considered eligible for analysis when either the disc or the macula photograph was assessable in at least one eye.

Deidentified fundus photographs were sent in digital format by mail to the RCRIC Fundus Photograph Reading Center at the University of Pennsylvania, where they were assessed in a systematic manner by graders and a retinal specialist who was unaware of any participant information. Within 3 weeks of receipt of the photographs, a “clinical” report including the results of the retinal assessment and color prints of the patient's fundus photographs were sent to the CRIC clinical sites for reidentification and distribution to the study participants. When warranted, the report stated that an examination by an ophthalmologist was recommended. Retinopathy was defined as vascular pathology as a result of diabetes, hypertension, or other conditions. Signs suggestive of glaucoma were cup-to-disc ratio of ≥0.7 and asymmetry between two eyes. Signs of age-related macular degeneration were large drusen and pigmentary changes. Vision-threatening conditions were proliferative diabetic retinopathy and embolic plaque. Clinically actionable fundus pathology was considered any condition that would warrant an examination by an ophthalmologist.

Data Analysis

To assess whether the RCRIC population is representative of the overall CRIC cohort, we compared the CRIC baseline characteristics of participants who had photographs taken with those of CRIC participants who did not enroll in RCRIC and did not have photographs. We used t tests with the Satterthwaite adjustment for unequal variances to compare continuous variables and χ2 tests to compare the distributions of categorical variables. The association of the proportion of participants who had fundus pathology with key demographic and health characteristics was assessed first with χ2 tests and then with logistic regression, using stepwise model selection, to identify independent risk factors. Data values from the annual visit that was closest in time to RCRIC photography were used in the analysis of risk factors. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 1936 (74%) of 2605 eligible participants were photographed for RCRIC between June 2006 and May 2008. Characteristics of the RCRIC participants at their CRIC baseline visit are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of participants and nonparticipants in RCRIC

| Characteristic | Participants (n = 1936) | Nonparticipants (n = 669) | Pa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race (n [%]) | 0.69 | ||

| white | 965 (49.9) | 343 (51.3) | |

| black | 858 (44.3) | 292 (43.7) | |

| other | 113 (5.8) | 34 (5.1) | |

| Gender (n [%]) | 0.035 | ||

| male | 1055 (54.5) | 333 (49.8) | |

| female | 881 (45.5) | 336 (50.2) | |

| Ethnicity (n [%]) | 0.19 | ||

| Hispanic | 103 (5.3) | 27 (4.0) | |

| non-Hispanic | 1833 (94.7) | 642 (96.0) | |

| Hypertension (n [%]) | 0.003 | ||

| absent | 305 (15.8) | 74 (11.1) | |

| present | 1631 (84.3) | 594 (88.9) | |

| Diabetes (n [%]) | 0.005 | ||

| absent | 1070 (55.3) | 328 (49.0) | |

| present | 866 (44.7) | 341 (51.0) | |

| Age (years; mean ± SD) | 58.3 ± 10.8 | 57.8 (11.4) | 0.31 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg; mean ± SD) | 127.0 ± 21.1 | 129.2 ± 21.4 | 0.025 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg; mean ± SD) | 71.5 ± 12.7 | 71.8 ± 12.9 | 0.59 |

| eGFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2; mean ± SD) | 44.6 ± 13.7 | 40.1 ± 13.1 | 0.0001 |

| BMI (kg/m2; mean ± SD) | 31.6 ± 7.5 | 32.7 ± 8.3 | 0.0037 |

P value for comparisons calculated by χ2 test for categorical variables and t test for continuous variables.

A comparison of the CRIC participants who had fundus photography taken with the CRIC participants who did not participate in our RCRIC study showed no statistically significant differences in age, race, ethnicity distribution, or diastolic BP (Table 1). Mean systolic BP, prevalence of diabetes, proportion of women, and body mass index (BMI), however, were significantly lower in RCRIC participants than in CRIC participants who did not have photographs. Finally, the mean eGFR was significantly higher in the RCRIC participants who had photographs taken.

Assessable photographs that allowed clinical assessment of fundus pathology were obtained from 1904 (98%) of the 1936 RCRIC participants. The photographs of a participant were considered assessable when either the disc or the macula photograph of at least one eye was assessable. Both eyes were assessable for 1796 participants. Of the assessable eyes assessed, 3434 eyes had photographs of the macula and disc, 202 eyes had photographs only of the disc, and 64 eyes had photographs only of the macula.

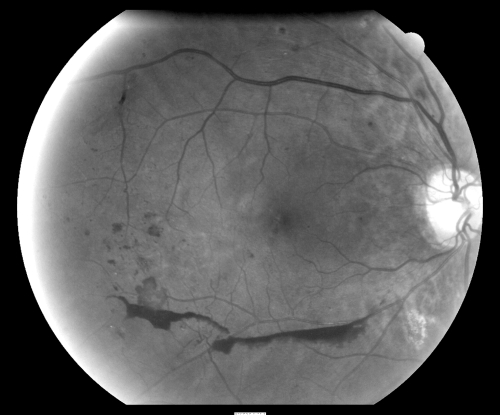

Our investigation identified a variety of fundus pathologies. We found 864 participants (45% of the 1904 RCRIC participants) who warranted a complete eye examination to determine whether treatment or careful follow-up was necessary. Sixty-five (3%) of 1904 participants had a serious condition that required an emergency eye examination for sight-threatening conditions. These participants had signs of high-risk diabetic retinopathy (58 participants) and/or an arterial embolic plaque (eight participants). A typical example of an eye with proliferative diabetic retinopathy and high-risk characteristics for visual loss that needed prompt ocular care is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Typical example of an eye with proliferative diabetic retinopathy and high-risk characteristics for visual loss that needed prompt ocular care. This gray-scale image was converted from a color photograph and was enhanced by increasing the contrast and brightness to highlight the pathologic features.

As summarized in Table 2, retinopathy (diabetic, hypertensive, or other) was observed in 482 (25%) of the 1904 participants. Signs of glaucoma were detected in 170 (9%) participants. Signs of age-related macular degeneration were present in 144 (8%) participants. A nevus was present in 25 (1%) participants, and miscellaneous abnormal findings such as retinal deposits, media opacities, macular scars, optic nerve atrophy, and other conditions were present in 120 (6%) participants.

Table 2.

Types of ocular fundus pathology present among the 1904 RCRIC participants with assessable photography

| Fundus Pathologya | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Diabetic, hypertensive, or other retinopathy | 482 (25.3) |

| Signs of glaucoma | 170 (8.9) |

| Signs of age-related macular degeneration | 144 (7.6) |

| Nevus | 25 (1.3) |

| Arterial embolic plaque | 8 (0.4) |

| Other findings (retinal deposits, media opacities, macular scars, optic nerve atrophy, and others) | 120 (6.3) |

Some participants had more than one finding.

The association of demographic and key health characteristics with fundus pathology was examined (Table 3). The percentage of participants with any eye pathology was higher among the older, male, and nonwhite demographic groups. Participants with hypertension and/or diabetes, higher eGFR, CVD, and higher BMI also had higher percentages of any eye pathology. Among the 35 patients who had neither hypertension nor diabetes and had eye pathology, the most common conditions were signs of glaucoma in 12 (34.3%) and signs of age-related macular degeneration in nine (25.7%). One patient had an embolic plaque. When all of the characteristics noted in Table 3 were included in logistic regression modeling (Table 4), neither age (P = 0.64) nor BMI (P = 0.30) was associated with a statistically significant degree with the presence of any pathology. Male gender, nonwhite race, and presence of CVD were associated with odds ratios (ORs) of 1.29, 1.63, and 1.56, respectively. The ORs increased with lower eGFR. Compared with participants with neither hypertension nor diabetes, participants with hypertension were at increased risk for any eye pathology (OR 1.47); however, the ORs for those with diabetes alone (OR 5.18) or with diabetes and hypertension (OR 3.75) were substantially greater.

Table 3.

Proportion with fundus pathology by participant characteristics

| Characteristic | n | Any Fundus Pathology (n [%]) | P | Retinopathy (n [%]) | P | Signs of Glaucoma (n [%]) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 1904 | 864 (45.4) | 482 (25.3) | 170 (8.9) | |||

| Age (years) | |||||||

| <50 | 323 | 123 (38.1) | 91 (28.2) | 21 (6.5) | |||

| 50 to 59 | 483 | 228 (47.2) | 140 (30.0) | 42 (8.7) | |||

| 60 to 69 | 727 | 324 (44.6) | 167 (23.0) | 72 (9.9) | |||

| ≥70 | 371 | 189 (50.9) | 0.01 | 84 (22.6) | 0.01 | 35 (9.4) | 0.13 |

| Gender | |||||||

| male | 1038 | 499 (48.10) | 294 (28.30) | 107 (10.30) | |||

| female | 866 | 365 (42.15) | 0.01 | 188 (21.71) | 0.001 | 63 (7.27) | 0.02 |

| Race | |||||||

| white | 954 | 360 (37.7) | 186 (19.5) | 46 (4.8) | |||

| nonwhite | 950 | 504 (53.1) | <0.001 | 296 (31.2) | <0.001 | 124 (13.1) | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Hispanic | 100 | 50 (50.0) | 38 (38.0) | 4 (4.0) | |||

| non-Hispanic | 1804 | 814 (45.1) | 0.34 | 444 (24.6) | 0.003 | 166 (9.2) | 0.10 |

| Hypertension and diabetes | |||||||

| neither | 181 | 35 (19.3) | 1 (0.6) | 12 (6.6) | |||

| hypertension | 821 | 282 (33.4) | 74 (9.0) | 93 (11.3) | |||

| diabetes | 38 | 22 (57.9) | 15 (39.5) | 4 (10.5) | |||

| both | 863 | 524 (60.7) | <0.001 | 391 (45.3) | <0.001 | 61 (7.1) | 0.01 |

| eGFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | |||||||

| ≥50 | 606 | 211 (34.8) | 92 (15.2) | 62 (10.2) | |||

| 40 to 49 | 427 | 182 (42.6) | 79 (18.5) | 42 (9.8) | |||

| 30 to 39 | 407 | 194 (47.7) | 123 (30.2) | 24 (5.9) | |||

| ≤29 | 464 | 277 (59.7) | <0.001 | 188 (40.5) | <0.001 | 42 (9.1) | 0.19 |

| Any CVD | |||||||

| present | 669 | 387 (57.9) | 240 (35.9) | 65 (9.7) | |||

| absent | 1235 | 477 (38.6) | <0.001 | 242 (19.6) | <0.001 | 105 (8.5) | 0.38 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||||||

| <25.0 | 361 | 157 (43.5) | 90 (24.9) | 33 (9.1) | |||

| 25.0 to 29.9 | 548 | 222 (40.5) | 111 (20.3 | 55 (10.0) | |||

| 30.0 to 34.9 | 497 | 239 (48.1) | 132 (26.6) | 51 (10.3) | |||

| ≥35.0 | 498 | 246 (49.4) | 0.009 | 149 (29.9) | 0.009 | 31 (6.2) | 0.11 |

Table 4.

Characteristics associated with having any pathology, retinopathy, or signs of glaucoma: Logistic regression model

| Characteristic | Any Fundus Pathology |

Retinopathya |

Signs of Glaucoma |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| <50 | – | – | 1.00 | <0.001 | – | – |

| 50 to 59 | – | 0.57 (0.38 to 0.84) | – | |||

| 60 to 69 | – | 0.36 (0.25 to 0.53) | – | |||

| ≥70 | – | 0.26 (0.17 to 0.40) | – | |||

| Gender | ||||||

| female | 1.00 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 0.01 |

| male | 1.29 (1.06 to 1.57) | 1.52 (1.17 to 1.96) | 1.59 (1.14 to 2.22) | |||

| Race | ||||||

| white | 1.00 | <0.001 | 1.00 | <0.001 | 1.00 | <0.001 |

| nonwhite | 1.63 (1.33 to 1.99) | 1.66 (1.29 to 1.96) | 3.32 (2.31 to 4.77) | |||

| Hypertension and diabetes | ||||||

| neither | 1.00 | <0.001 | – | 1.00 | 0.004 | |

| hypertension | 1.47 (0.97 to 2.23) | 1.00 | <0.001 | 1.16 (0.61 to 2.21) | ||

| diabetes | 5.18 (2.43 to 11.06) | 10.58 (5.07 to 22.06) | 1.41 (0.42 to 4.78) | |||

| both | 3.75 (2.47 to 5.71) | 9.70 (7.16 to 13.21) | 0.62 (0.32 to 1.20) | |||

| eGFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | ||||||

| ≥50 | 1.00 | <0.001 | 1.00 | <0.001 | – | – |

| 40 to 49 | 1.16 (0.88 to 1.53) | 1.01 (0.70 to 1.47) | – | |||

| 30 to 39 | 1.31 (1.00 to 1.74) | 1.98 (1.38 to 2.83) | – | |||

| ≤29 | 2.12 (1.62 to 2.78) | 2.99 (2.05 to 4.06) | – | |||

| Any CVD | ||||||

| absent | 1.00 | <0.001 | 1.00 | 0.001 | – | – |

| present | 1.56 (1.27 to 1.92) | 1.65 (1.28 to 2.14) | – | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||||

| <25.0 | – | – | 1.00 | 0.01 | – | – |

| 25.0 to 29.9 | – | 0.65 (0.44 to 0.95) | – | |||

| 30.0 to 34.9 | – | 0.69 (0.47 to 1.01) | – | |||

| ≥35.0 | – | 0.51 (0.35 to 0.76) | – | |||

All factors listed with ORs were included in the final model after stepwise selection. CI, confidence interval.

Participants (n = 181) with neither hypertension nor diabetes were excluded from the model because only one (0.55%) had retinopathy.

The association of each of the three most prevalent specific eye conditions with the demographic and health factors was also examined. Signs of diabetic or hypertensive retinopathy were associated with each of the factors included in Table 3. Only one (0.55%) of the 181 participants without a diagnosis of diabetes or hypertension had retinopathy; this group of very low-risk participants was excluded from the logistic regression models for risk of retinopathy. After adjustment for other factors, risk for retinopathy decreased with older age and increased BMI (Table 4). Male gender, nonwhite race, and presence of CVD were associated with ORs of 1.52, 1.66, and 1.65, respectively. The ORs increased with lower eGFR. Compared with participants with hypertension only, participants with diabetes alone (OR 10.58) or with diabetes and hypertension (OR 9.70) had substantially higher proportions with retinopathy. Three factors were associated with signs of glaucoma when considered individually (Table 3) and in the logistic regression model (Table 4). Nonwhite race (OR 3.32) and male gender (OR 1.59) were associated with higher proportions with glaucoma. The proportions of signs of glaucoma were highest in the participants with diabetes only and lowest in the participants with both hypertension and diabetes. The only factor associated with age-related macular degeneration was older age. With regard to serious eye conditions that required urgent eye care, the prevalence was rare in those without diabetes or hypertension (0.6%), more common in those with hypertension only (1.5%), and most common in those with diabetes alone (7.9%) or those with a combination of diabetes and hypertension (5.7%; P < 0.001).

Discussion

Our results show that this cohort of participants with CKD has a high prevalence of fundus pathology. Approximately 45% of participants who had assessable photographs had findings that warranted a follow-up examination with an ophthalmologist. In 3% of the participants, we identified serious eye conditions that required immediate and urgent follow-up. In addition, retinopathy (diabetic, hypertensive, or other) was observed in 482 (25%) participants. This prevalence is much higher than the 3.4% prevalence of retinopathy and the 0.75% prevalence of vision-threatening retinopathy reported by Kempen et al. (15) for the US adult population. Furthermore, the prevalence of fundus pathology in this study was 58% among participants with diabetes and without systemic hypertension and 61% among participants with diabetes and systemic hypertension. These values again are higher than those reported by population-based studies (1).

We also found that lower eGFR was associated with a much higher incidence of fundus pathology. The percentage of participants with any eye pathology was 60% in those with eGFR <30 and 35% in participants with eGFR ≥50. Furthermore, serious eye pathology was present in 7% of participants with eGFR <30 and only 2% of participants with eGFR ≥50. CVD was also associated with increased eye pathology. These results, which are in agreement with previous reports showing higher prevalence of eye pathology in participants with CKD (1,2,4,6–8) and CVD (16), strongly suggest that microvascular disease may play a role in the development of ocular, renal, and cardiovascular diseases; therefore, the presence of fundus pathology in participants with CKD may provide information of prognostic value regarding progression of renal disease. Common pathogenic mechanisms for retinopathy and nephropathy such as basement membrane thickening may explain this relationship to some extent (17).

In addition, our results show that male gender and nonwhite race, as well as conditions such as diabetes and hypertension, are associated with a higher prevalence of eye pathology. All of these findings fit well with previous reports (1). Possibly, genetic or socioeconomic differences, worse access to care, and worse diabetes and hypertension control in men and nonwhite participants could explain the higher prevalence.

In this report, we concentrate on our preliminary evaluation of clinically actionable fundus pathology. Our assessment was based only on nonstereo fundus photography, and we had no information about patients' visual acuity or presence or absence of ocular complaints. An important component of diabetic and hypertensive retinal pathology is the presence of clinically significant macular edema, a condition that can be effectively treated by laser photocoagulation, resulting in a significant reduction of future visual loss. Detection of macular edema, however, cannot be accurately performed on nonstereo photographs. Although there are some retinopathy features, such as hard exudates and microaneurysms in the proximity of the fovea, that may suggest the presence of edema, a definitive diagnosis can be obtained only through a clinical stereoscopic evaluation of the eye.

Using the information provided by nonstereo photographs, we identified 45% of participants who had fundus features that warranted a complete eye examination to determine whether they required close follow-up or ocular treatment. A large proportion, 25%, of RCRIC participants had retinopathy that required a complete dilated eye examination to determine the need for ocular laser photocoagulation therapy. Other participants had evidence of age-related macular degeneration, a common eye condition that can severely affect vision. This disease in its advanced stages can be treated effectively with laser photocoagulation (18), photodynamic therapy (19), or intraocular injections of vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors (20). Furthermore, there is a preventive treatment of supplementation with high-dosage vitamins C and E, beta-carotene, and zinc that can reduce the risk for vision loss by 30% in high-risk cases (21). A dilated eye examination is needed, however, to determine whether an individual patient has pathology that warrants the initiation of such preventive treatment.

Some participants (2%) had choroidal nevi, benign fundus lesions that require monitoring to assess whether there is growth that may suggest malignancy. Other participants had increased optic nerve cup-to-disc ratios, a finding suggestive of glaucoma, a frequently asymptomatic, serious sight-threatening condition that requires follow-up by an ophthalmologist. Finally, some participants had embolic plaques, a condition that requires additional workup to identify the source of this embolic material.

A comparison of the CRIC participants who had fundus photography in the RCRIC study with the rest of the available CRIC participants who did not participate in the RCRIC study suggests that the RCRIC study included healthier individuals than the overall CRIC population. Our study group included participants with higher mean eGFR, lower mean systolic BP, lower mean BMI, and less prevalence of diabetes. This suggests that the prevalence of eye conditions shown in our data may underestimate the prevalence of eye pathology in the overall CRIC population. Limitations of our study are that we had only nonstereo photographs without a complete eye examination and that not all CRIC participants were included in our study, as discussed already.

Conclusions

Our results demonstrate high prevalence of fundus pathology in the CRIC study cohort, suggesting shared causative pathways between kidney and retinal disease. Patients with CKD and with health characteristics similar to those of the CRIC study participants should be encouraged to receive a complete eye examination.

Disclosures

R.T. is a consultant for Roche, Glaxo Smithkline, and NiCox; and H.F. has a contract with RTI International Amgen.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01 DK 74151, UL1 RR-024134, MO1 RR-16500, UL1 RR-024989, MO1 RR-000042, UL1 RR-024986, UL1 RR-029879, and UL1 RR-024131; Vivian S. Lasko Research Fund; Nina C. Mackall Trust; and Research to Prevent Blindness.

Parts of this article were published as an abstract (abstract 2148) at the annual meeting of the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology; April 27 through May 1, 2008; Fort Lauderdale, FL.

We acknowledge the efforts of Martha Coleman, Anapurna Singh, and Janet Cohan.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Klein R, Klein BE: Vision disorders in diabetes. In: Diabetes in America, Bethesda, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 1995, pp 293– 338 NIH publication 95-1468 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kofoed-Enevoldsen A, Jensen T, Borch-Johnsen K, Deckert T: Incidence of retinopathy in type I (insulin dependent) diabetes: Association with clinical nephropathy. J Diabet Complications 1: 96– 99, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 329: 977– 986, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chavers BM, Mauer SM, Ramsay RC, Steffes MW: Relationship between retinal and glomerular lesions in IDDM patients. Diabetes 43: 441– 446, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klein R, Klein BE, Cruishanks KJ, Brazy PC: The 10-year incidence of renal insufficiency in people with type I diabetes. Diabetes Care 22: 743– 751, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Intervention and Complications Research Group: Retinopathy and nephropathy in patients with type I diabetes four years after the trial of intensive therapy. N Engl J Med 342: 381– 389, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wong TY, Coresh J, Klein R, Muntner P, Couper DJ, Sharrett AR, Klein BE, Heiss G, Hubbard LD, Duncan B: Retinal microvascular abnormalities and renal dysfunction: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 2469– 2476, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sabanayagam C, Shankar A, Koh D, Chia KS, Saw SM, Lim SC, Tai ES, Wong TY: Retinal microvascular caliber and chronic kidney disease in an Asian population. Am J Epidemiol 169: 625– 632, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liew G, Mitchell P, Wong TY, Iyengar SK, Wang JJ: CKD increases the risk of age-related macular degeneration. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 806– 811, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klein R, Knudtson MD, Lee KE, Klein BE: Serum cystatin C level, kidney disease markers, and incidence of age-related macular degeneration. The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol 127: 193– 199, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nitsch D, Evans J, Roderick PJ, Smeeth L, Fletcher AE: Associations between chronic kidney disease and age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 16: 181– 186, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pereira BJ: Introduction: New perspectives in chronic renal insufficiency. Am J Kidney Dis 36[ Suppl 3]: S1– S3, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feldman HI, Appel LJ, Chertow GM, Cifelli D, Cizman B, Daugirdas J, Fink JC, Franklin-Becker ED, Go AS, Hamm LL, He J, Hostetter T, Hsu CY, Jamerson K, Joffe M, Kusek JW, Landis JR, Lash JP, Miller ER, Rahman M, Townsend RR, Wright JT, Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study Investigators: The Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) study: Design and methods. J Am Soc Nephrol 14[ Suppl 2]: S148– S153, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lash JP, Go AS, Appel LG, He J, Ojo A, Rahman M, Townsend RR, Xie D, Cifelli D, Cohan J, Fink JC, Fischer MJ, Gadegbeku C, Hamm LL, Kusek JW, Landis JR, Andrew Narva A, Robinson N, Teal V, Feldman HI, Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study Group: Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study: Baseline characteristics and associations with kidney function. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 1302– 1311, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kempen JH, O'Colmain BJ, Leske MC, Haffner SM, Klein R, Moss SE, Taylor HR, Hamman RF, Eye Prevalence Research Group: The prevalence of diabetic retinopathy among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol 122: 552– 563, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong TY, Rosamond W, Chang PP, Couper DJ, Sharrett AR, Hubbard LD, Folsom AR, Klein R: Retinopathy and risk of congestive heart failure. JAMA 293: 63– 69, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olson J: Diabetes mellitus. In: Hepinstall's Pathology of the Kidney, 5th Ed., edited by Jennette JC, Olson JL, Schwartz MM, Silva FG.Philadelphia, Lippincott-Raven, 1998, pp 1247– 1287 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laser photocoagulation for juxtafoveal choroidal neovascularization. Macular Photocoagulation Study Group. Arch Ophthalmol 112: 500– 509, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Treatment of age related macular degeneration with photodynamic therapy (TAP) study group: Photodynamic therapy of subfoveal choroidal neovascularization in age related macular degeneration with Verteporfin. Arch Ophthalmol 117: 1329– 1345, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown DM, Kaiser PK, Michels M, Soubrane G, Heier JS, Kim RY, Sy JP, Schneider S, Anchor Study Group: Ranimizumab versus verteporfin for neovascular age related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med 355: 1432– 1444, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group: A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E, beta carotene, and zinc for age-related macular degeneration and vision loss: AREDS report no. 8 [published erratum appears in Arch Ophthalmol 126: 1251, 2008]. Arch Ophthalmol 119: 1417– 1436, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]