Abstract

HIV prevalence is the most commonly used measure to prioritize communities for HIV prevention. We show that data on two HIV infection stages (early vs. nonearly and late vs. nonlate) allow estimation of two better measures of prevention need: HIV incidence (for prevention of HIV acquisition) and expected probability of HIV transmission in unprotected sex acts between HIV-infected community members and susceptible individuals (for prevention of HIV transmission). The three ranking schemes—by prevalence, incidence, and transmission probability—lead to significantly different community rank orders. Disease stage information should be collected in HIV surveys.

Following the recent worldwide recession, prioritization of communities for HIV interventions is likely to become increasingly important as budgets for HIV are expected to decrease.1 In addition, it seems unlikely that universal antiretroviral treatment coverage can be achieved and maintained, unless the rate of new HIV infections is significantly reduced.2 Ranking is a common approach to prioritize communities for HIV prevention3 and HIV prevalence is the most commonly used measure for such ranking.4 The dominance of prevalence as a measure for prioritization for HIV prevention can be explained by the fact that it is the most widely available data on HIV, for instance, from antenatal care surveillance5 or Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS).6 However, although prevalence is a good measure for prioritization of HIV care needed by all HIV-infected individuals (e.g., tuberculosis screening), there are better measures of prevention need: the rate of new infections among susceptible community members (HIV incidence) for prevention of HIV acquisition and the expected probability of HIV transmission in a sex act between an HIV-infected community member and a susceptible individual for prevention of HIV transmission through “positive prevention.” Interventions to decrease HIV acquisition include male circumcision7 and behavior change in HIV-uninfected individuals. “Positive prevention,” i.e., targeting HIV-infected individuals to reduce HIV transmission, has recently been advocated to curb the HIV epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa.8,9 It includes disclosure of positive HIV status, behavior change in HIV-infected individuals, and antiretroviral therapy.8

We used data from a large HIV surveillance in the Hlabisa subdistrict, rural South Africa, to investigate the differences in the prioritization of geographic communities by prevalence, incidence, and transmission probabilities.10,11 The rate of new HIV infections in this area remains high.12 We first located eligible individuals (all women aged 15–49 years old and men aged 15–54 years old who were resident in the surveillance area in 2003/2004 and participated in the HIV surveillance) in 20 traditional Zulu communities, Izigodi, where they lived at the time of the HIV test in the surveillance, using a geographic information system.10 Izigodi are a meaningful concept of community, because they are the smallest unit of traditional Zulu leadership and community entry for HIV interventions would likely need to be negotiated with the local Isigodi chief, the Induna.

To measure community incidence and transmission probabilities, only two binary variables are necessary in addition to HIV status: early vs. nonearly and late vs. nonlate stage HIV infection. In each community, we measured the proportion of individuals with early-stage infection with the BED IgG-Capture Enzyme Immunoassay (BED assay), a test for recent HIV infection (TRI), which was previously validated in the surveillance area.13 The BED assay defines early-stage infection as 153 days after seroconversion, i.e., approximately half a year after HIV infection.14 We adjusted the proportion of individuals with early-stage infection for the long-term false-positive ratio of the BED assay in this community (1.69%).13 We then used the BED assay information to estimate HIV incidence following a locally validated approach.13 To identify individuals with late-stage disease, we linked the HIV data to information from a demographic surveillance. Individuals who died < 15 months after the date of their HIV test were classified as late-stage HIV infection.

We estimated the expected transmission probability in a random sex act between a community member and a susceptible individual by weighting early-, latent- (i.e., neither early nor late), and late-stage HIV prevalence by stage-specific transmission probabilities, as estimated in a recent meta-analysis.15 Per sex act, individuals in the early (late) disease stage are approximately nine (seven) times more likely to transmit HIV than individuals in the latent stage of HIV disease.15 In the ranking of communities, tied ranks were assigned the average of the ranks that would have been assigned without ties.

In total, 11,786 individuals were included in the study, on average 589 per Isigodi. The overall HIV prevalence across all Izigodi was 21.4% [95% confidence interval (CI) 20.7–22.1%]; early-stage, latent-stage, and late-stage HIV prevalences were, respectively, 1.4% (95% CI 1.2–1.6%), 19.0% (95% CI 18.3–19.7%), and 1.0% (95% CI 0.9–1.2%). The three ranking schemes—by HIV prevalence, incidence, and transmission probability—led to significantly different community rank orders (p = 0.0019, using the Friedman test) (Graph 1). Table 1 shows the point and standard error estimates of prevalence, incidence, and expected transmission probability, as well as the associated rankings for each Izigodi. The standard errors for incidence and expected transmission probability were estimated using nonparametric bootstrapping with replacement over 1000 repetitions.

Table 1.

Community Prevalence, Incidence, Transmission Probability, Rankings, and Rank Order Differencesa

| Community | n | Prevalence (%) | Incidence (per 100 person-years) | Expected transmission probability (per unprotected sex act) | Ranking based on prevalence | Ranking based on incidence | Ranking based on transmission probability | Difference in rank order based on incidence vs. prevalence | Difference in rank order based on transmission probability vs. prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 1796 | 31.18 (1.09) | 5.01 (1.18) | 0.0403 (0.0028) | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| B | 1249 | 28.42 (1.28) | 5.43 (1.37) | 0.0393 (0.0033) | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| C | 212 | 26.42 (3.03) | 10.97 (4.47) | 0.0434 (0.0092) | 3 | 1 | 1 | −2 | −2 |

| D | 291 | 23.71 (2.49) | 4.19 (2.44) | 0.0266 (0.0055) | 4 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 0 |

| E | 817 | 21.3 (1.43) | 1.91 (1.03) | 0.0237 (0.0029) | 5 | 15 | 8 | 10 | 3 |

| F | 556 | 20.68 (1.72) | 1.68 (1.24) | 0.0242 (0.0038) | 6 | 17 | 7 | 11 | 1 |

| G | 698 | 19.77 (1.51) | 2.89 (1.22) | 0.0227 (0.0032) | 7 | 11 | 10 | 4 | 3 |

| H | 921 | 19.00 (1.29) | 4.24 (1.31) | 0.0263 (0.0033) | 8 | 5 | 5 | −3 | −3 |

| I | 395 | 18.48 (1.95) | 0.58 (1.05) | 0.0181 (0.0034) | 9 | 19 | 18 | 10 | 9 |

| J | 792 | 18.43 (1.38) | 2.08 (1.04) | 0.0205 (0.0028) | 10 | 13 | 12 | 3 | 2 |

| K | 1070 | 17.85 (1.17) | 1.87 (0.88) | 0.0193 (0.0023) | 11 | 16 | 16 | 5 | 5 |

| L | 407 | 17.44 (1.88) | 2.02 (1.45) | 0.0202 (0.0040) | 12 | 14 | 13 | 2 | 1 |

| M | 237 | 17.3 (2.46) | 4.09 (2.43) | 0.0248 (0.0064) | 13 | 7 | 6 | −6 | −7 |

| N | 311 | 16.08 (2.08) | 4.79 (2.29) | 0.0215 (0.0052) | 14 | 4 | 11 | −10 | −3 |

| O | 144 | 15.97 (3.05) | 1.23 (2.09) | 0.014 (0.0050) | 15 | 18 | 20 | 3 | 5 |

| P | 722 | 15.93 (1.36) | 0.42 (0.70) | 0.0163 (0.0025) | 16 | 20 | 19 | 4 | 3 |

| Q | 602 | 14.95 (1.45) | 2.6 (1.26) | 0.0194 (0.0035) | 17 | 12 | 14 | −5 | −3 |

| R | 134 | 14.93 (3.08) | 3.54 (2.88) | 0.0181 (0.0068) | 18 | 8 | 17 | −10 | −1 |

| S | 219 | 14.16 (2.36) | 3.20 (2.21) | 0.0235 (0.0068) | 19 | 10 | 9 | −9 | −10 |

| T | 213 | 14.08 (2.38) | 3.31 (2.28) | 0.0194 (0.0060) | 20 | 9 | 15 | −11 | −5 |

Standard errors are shown in parentheses. Standard errors of incidence and transmission probability point estimates are based on nonparametric bootstrapping with replacement over 1000 repetitions.

In comparison to prevalence-based ranking, only one of the 20 communities retained its position in each of the two alternative rankings, whereas in incidence-based (transmission probability-based) ranking 15 (12) communities moved three or more places, 10 (6) communities moved five or more places, and 6 communities (1 community) moved 10 or more places (Table 1). The three communities with HIV prevalence >25% did not move more than two places when comparing ranking based on prevalence to either incidence- or transmission probability-based ranking. Among the 17 communities with lower prevalence, substantially larger changes in rank order occurred, in particular when moving from prevalence- to incidence-based ranking (Table 1). Furthermore, the ratio of the highest to the lowest value among the 20 communities was larger in incidence comparison (11.0 per 100 person-years/0.4 per 100 person-years = 27.5) and transmission probability comparison (0.043/0.014 = 3.1) than in prevalence comparison (31.2%/14.1% = 2.2).

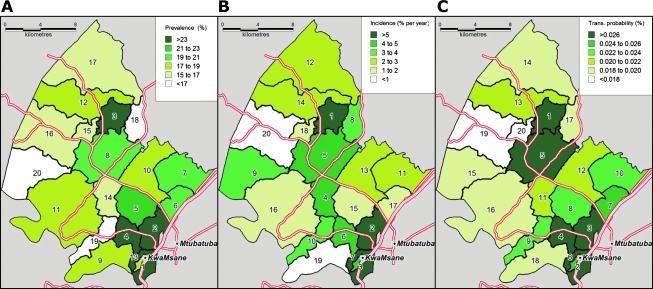

Our results demonstrate that resource allocation for HIV prevention based on ranking by HIV prevalence—e.g., giving most to the community with the highest and least to the community with the lowest prevalence—is unlikely to lead to the best possible use of prevention budgets (Fig. 1). For example, assume that policymakers had a budget to provide HIV acquisition prevention in half of the communities in our sample. If they choose to implement the prevention intervention in the 10 communities ranked highest according to prevalence instead of incidence, they would (wrongly) select communities E, F, G, I, and J instead of communities M, N, R, S, and T (see Table 1).

FIG. 1.

Community ranking according to HIV prevalence, incidence, and transmission probability. Each homogeneously colored area is a traditional Zulu community, Isigodi. The numbers in the areas represent the community rank according to HIV prevalence (A), incidence (B), and transmission probabilities (C).

Although the rankings of point estimates by the three measures differ significantly from each other, due to sampling error, not all of the cross-community differences in the individual measures are statistically significant (Table 1). Nevertheless, our findings are relevant because policymakers are likely to focus on differences in ranking rather than the statistical significance of one-by-one comparisons of communities in ranking measures. Furthermore, in larger surveys covering wider geographic areas, such as national HIV surveys, the differences in ranking measures across subareas, such as provinces, are likely to be significant.

The addition of validated TRI to cross-sectional HIV surveys,13 such as the DHS, would allow better prioritization for prevention of HIV acquisition than is currently possible. TRI are easy to apply. They involve additional laboratory testing of samples identified as HIV infected in standard HIV antibody tests but do not require repeat testing of HIV-uninfected individuals to detect early-stage infection. Thus, they are less complex and less expensive to implement than longitudinal HIV surveillances and yield incidence estimates without the delay of a second round of testing. In a systematic review,16 we identified 39 published studies (up to March 2009) that estimated HIV incidence based on information obtained by applying the BED assay, the particular TRI used in the present study. Past applications of the BED assay included national and subnational HIV surveys of general populations in sub-Saharan Africa,13,17,18 demonstrating that it is indeed feasible to add TRI to large-scale surveys in the region. Further studies are needed to estimate the cost-effectiveness of routinely adding TRI to HIV surveys in sub-Saharan Africa.

The further addition of information on the proportion of individuals with late-stage disease could improve prioritization for prevention of HIV transmission, or “positive prevention.” In most settings in sub-Saharan Africa, data on HIV-specific mortality, which could be used to estimate the proportion of individuals with late-stage HIV disease, is unlikely to be available because the vital registration systems in most countries in the region record only small proportions of all deaths19 and among the recorded deaths HIV is commonly underreported as a cause.20 However, alternative approaches to measure cause-specific mortality in developing countries have recently been developed and validated in some settings. These approaches include verbal autopsy based on symptom pattern, which could be applied in household surveys, and estimation of cause-specific mortality statistics using deaths records routinely collected in health care facilities.21–23 The use of cause-of-death data in prioritizing communities for HIV prevention adds another reason to the many existing ones as to why such data are of critical importance for health policy.

In sum, policymakers aiming to identify communities to target for HIV prevention should consider collecting information on disease stage in addition to HIV status, using locally validated methods.

Acknowledgments

We thank Phumzile Dlamini, Thobeka Mngomezulu, Zanomsa Gqwede, Claudia Wallrauch, and Kobus Herbst and the field staff at the Africa Centre for Health and Population Studies at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, for their work in collecting the data used in this study and the communities in the Africa Centre demographic surveillance area for their support and participation in this study; we also thank Thomas McWalter for helpful discussions. The study was supported by the Wellcome Trust through a grant to the Africa Centre for Health and Population Studies, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa (GR065377/Z/01/B) and the Africa Centre's Demographic Surveillance Information System (GR065377/Z/01/H), which funds the population-based HIV surveillance. In addition, this publication was supported by Cooperative Agreement Number 5U62PS022901 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Till Bärnighausen and Frank Tanser were supported by Grant 1R01-HD058482-01 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.UNAIDS, World Bank: The Global Economic Crisis and HIV Prevention and Treatment Programmes: Vulnerabilities, Impact. UNAIDS; Geneva: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bärnighausen T. Bloom DE. Humair S. Human resources for treating HIV/AIDS: Needs, capacities, and gaps. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21:799–812. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson-Masotti AP. Pinkerton SD. Holtgrave DR. Prioritization methods for HIV community planning. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2000;6:72–85. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200006040-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.UNAIDS: A Framework for Monitoring and Evaluating HIV Prevention Programmes for Most-at-Risk Populations. UNAIDS; Geneva: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rice BD. Batzing-Feigenbaum J. Hosegood V, et al. Population and antenatal-based HIV prevalence estimates in a high contracepting female population in rural South Africa. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:160. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Demographic and Health Surveys: HIV prevalence. Quickstats statistics. 2009.

- 7.Auvert B. Taljaard D. Lagarde E. Sobngwi-Tambekou J. Sitta R. Puren A. Randomized, controlled intervention trial of male circumcision for reduction of HIV infection risk: The ANRS 1265 Trial. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bunnell R. Mermin J. De Cock KM. HIV prevention for a threatened continent: Implementing positive prevention in Africa. JAMA. 2006;296:855–858. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.7.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.UNAIDS: Intensifying HIV Prevention. UNAIDS; Geneva: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanser F. Hosegood V. Bärnighausen T, et al. Cohort profile: Africa Centre Demographic Information System (ACDIS) and population-based HIV survey. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37:956–962. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bärnighausen T. Hosegood V. Timaeus IM. Newell ML. The socioeconomic determinants of HIV incidence: Evidence from a longitudinal, population-based study in rural South Africa. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 7):S29–S38. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000300533.59483.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bärnighausen T. Tanser F. Newell ML. Lack of a decline in HIV incidence in a rural community with high HIV prevalence in South Africa, 2003–2007. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2009;25:405–409. doi: 10.1089/aid.2008.0211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bärnighausen T. Wallrauch C. Welte A, et al. HIV incidence in rural South Africa: Comparison of estimates from longitudinal surveillance and cross-sectional cBED assay testing. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3640. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McDougal JS. Parekh BS. Peterson ML, et al. Comparison of HIV type 1 incidence observed during longitudinal follow-up with incidence estimated by cross-sectional analysis using the BED capture enzyme immunoassay. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2006;22:945–952. doi: 10.1089/aid.2006.22.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boily MC. Baggaley RF. Wang L, et al. Heterosexual risk of HIV-1 infection per sexual act: Systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:118–129. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70021-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bärnighausen T. McWalter TA. Rosner Z. Newell M-L. Welte A. The use of the BED capture enzyme immunoassay to estimate HIV incidence: A systematic review, sensitivity analysis. Epidemiology. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181e9e978. (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mermin J. Musinguzi J. Opio A, et al. Risk factors for recent HIV infection in Uganda. JAMA. 2008;300:540–549. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shisana O. Rehle T. Simbayi LC, et al. South African National HIV Prevalence, HIV Incidence, Behaviour and Communication Survey. HSRC Press; Cape Town: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mathers CD. Fat DM. Inoue M. Rao C. Lopez AD. Counting the dead and what they died from: An assessment of the global status of cause of death data. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:171–177. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Groenewald P. Bradshaw D. Dorrington R. Bourne D. Laubscher R. Nannan N. Identifying deaths from AIDS in South Africa: An update. AIDS. 2005;19:744–745. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000166105.74756.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murray CJ. Lopez AD. Barofsky JT. Bryson-Cahn C. Lozano R. Estimating population cause-specific mortality fractions from in-hospital mortality: Validation of a new method. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e326. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murray CJ. Lopez AD. Feehan DM. Peter ST. Yang G. Validation of the symptom pattern method for analyzing verbal autopsy data. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e327. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whiting DR. Setel PW. Chandramohan D. Wolfson LJ. Hemed Y. Lopez AD. Estimating cause-specific mortality from community- and facility-based data sources in the United Republic of Tanzania: Options and implications for mortality burden estimates. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84:940–948. doi: 10.2471/blt.05.028910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]