Abstract

The study is an analysis of baseline data from a pilot psychosocial support intervention for HIV-affected youth and their caregivers in Haiti. Six sites in Haiti's Central Department affiliated with Partners In Health/Zanmi Lasante (PIH/ZL) and the Haitian Ministry of Health were included. Participants were recruited from a list of HIV-positive patients receiving care at PIH/ZL. The baseline questionnaire was administered from February 2006 to January 2007 with HIV-affected youth (n = 492), ages 10–17, and their caregivers (n = 330). According to findings at baseline, the youth reported high levels of anxiety, including constant fidgeting (86%), restlessness (83%), and worrying a lot (56%). Their parents/caregivers also reported a high level of depressive symptoms, such as low energy (73%), feeling everything is an effort (71%), and sadness (69%). Parents' depressive symptoms were positively associated with their children's psychological symptoms (odds ratio [OR] =1.6–2.4) and psychosocial functioning (OR =1.6 according to parental report). The significant levels of anxiety and depression observed among HIV-affected youth and their caregivers suggest that psychosocial interventions are needed among HIV-affected families in central Haiti and other high HIV burden areas. The results suggest that a family-focused approach to service provision may be beneficial, possibly improving quality of life, as well as psychosocial and physical health-related outcomes among HIV-affected youth and their caregivers, particularly HIV-positive parents.

Introduction

Worldwide, approximately 15 million children have been orphaned by HIV/AIDS, having lost one or both parents to the disease.1 Beyond those youth who have been orphaned by HIV, there are countless others who have been affected by HIV as their parents or caregivers are living with HIV. Both children orphaned by HIV and whose parents are living with HIV are considered vulnerable due to the attendant medical, psychosocial, and economic risks of the disease—from stigma and isolation to lack of access to education and adequate nutrition.2–5 Youth affected by HIV in resource-poor settings can face a number of significant challenges on a daily basis including caring for an ill parent, assuming a parental role in the household, helping to sustain the family financially, receiving a reduced level of attention from caregivers, and having inadequate resources for sustenance or school. If one or both parents have died, the stress on children can be exacerbated because they are grieving for this significant loss in their lives.4,6–9

As antiretroviral therapy (ART) becomes more widely available in the developing world, some of this burden has lessened, yet many youth continue struggling to cope with the physical and psychological burden of HIV within the family. In particular, children who have been infected with HIV perinatally are more likely to survive because of access to ART. Following these children over time has shown that they have demonstrated challenges in cognitive development. For example, one study showed that HIV-positive youth had a greater likelihood of enrolling in special education classes.10 In addition to the potential cognitive effects of HIV, among HIV-infected youth social and emotional development can also be affected by a sense of social isolation, hopelessness, anxiety, and depression.11,12

Although there are mechanisms for resilience among youth and caregivers in HIV-affected families, the significant stressors encountered by HIV-affected families have been associated with poor mental health outcomes.6,13–16 Significant levels of depression have been observed among HIV-positive adults.16–20 In particular, up to 80% of HIV-positive parents have reported elevated levels of mental health symptoms.21

Studies have demonstrated a significant burden of both internalizing symptoms (such as withdrawal) as well as externalizing symptoms (such as aggressive behavior) among HIV-affected youth.22 School performance can also be affected due to problems with attention, memory, and cognitive difficulties related to these symptoms.22–27

Although Haiti has one of the highest burdens of HIV in the Western Hemisphere (2.2% according to UNAIDS 2008)1 and a multitude of other social and economic problems that place youth and families at risk, the psychosocial impact of HIV on families in Haiti has not been documented. The present study fills a critical gap in describing the burden of mental health symptoms among HIV-affected youth and their parents/caregivers as well as the effect of parental depressive symptoms on their children's psychosocial functioning. As efforts to reach orphans and vulnerable children are increased28 it is critical to understand the needs of the populations affected to develop appropriate interventions to reduce vulnerability and maximize psychosocial functioning among these families.

Given the high burden of mental health symptoms observed among HIV-positive adults and HIV-affected youth in many settings6,21,22 and the limited knowledge available on this area of inquiry in Haiti, the aims of the study were to: (1) describe the burden of psychological symptoms and degree of psychosocial functioning among HIV-affected youth; (2) describe the burden of depressive symptoms among their parents/caregivers; and (3) examine the association between depressive symptoms in parents/caregivers and psychosocial functioning among HIV-affected youth.

Methods

Setting

The study was performed in Haiti's Central Department at six sites affiliated with Partners In Health/ Zanmi Lasante (PIH/ZL) and the Haitian Ministry of Health. Study participants were recruited from February 2006 to January 2007 from a comprehensive list of HIV-positive patients at these sites who have received services through the HIV Equity Initiative (HEI), a program started in 1998 to provide comprehensive HIV treatment including antiretroviral therapy (ART) to people living with HIV.29 At the time the study began in 2006, over 2000 HIV-positive patients were enrolled on ART at PIH/ZL sites. Information from patients receiving ART was entered into the electronic medical record for the HIV program (HIV-EMR) and included data on the patients' medical history, names and ages of people in the household, socioeconomic and demographic characteristics, laboratory tests, drug regimens, and other related clinical information.30 The family members were engaged in care for HIV testing and the provision of social support as needed; thus, the children were known to the clinic-based and community level staff. Additionally, children known to be orphans because of HIV who were in the catchment area of the clinic sites were recruited through the social workers and medical service providers at each site.

Study population and design

Enrollment criteria included youth who were HIV affected and between 10–17 years of age. For the purpose of this study, a youth was HIV affected if: he/she was HIV positive; had a parent or caregiver who was HIV positive; or had lost one or both parents to HIV.

All patients who were eligible and receiving care at the six designated PIH/ZL sites were asked to participate in the study. Among 576 eligible youth, 492 agreed to participate (85%). Among those who participated 20 youth were HIV positive (4%). Given that a number of caregivers had more than one child participating in the study, 330 caregivers were enrolled. Informed consent from parents/caregivers and assent from youth were obtained for all study participants. All eligible individuals screened had access to counseling with a psychologist or social worker whether or not they consented to participate in the study. Once consented, adults and children in the study population were interviewed by trained social workers. Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained from the Office for Research Subject Protection at Harvard Medical School and the Zanmi Lasante ethics committee. The structured interviews targeted psychological symptomatology and psychosocial functioning described below and were adapted to the Haitian context.

Measures

Psychological symptoms in youth

Goodman's Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) was used to assess the level of psychological symptomatology in children.31 The SDQ is a 25-item questionnaire that assesses 5 domains: conduct problems, hyperactivity, emotional symptoms, peer problems, and prosocial behavior. The SDQ has been used widely, is available in over 40 languages, and has demonstrated good reliability and validity.32–35 In terms of validity for use in resource-poor settings, the SDQ was able to discriminate between emotional disorders, conduct disorder, and hyperactivity disorder, with estimates for area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve ranging from 0.84 to 0.94 for the parent version and 0.81 to 0.89 for the youth version in Bangladesh.36 The child self-report as well as the parent report versions were administered verbally with study participants. Youth who scored in the highest tertile for the SDQ were compared with those who scored in the bottom two tertiles for the purposes of this analysis.

Level of psychosocial functioning in youth

To assess psychosocial functioning in the child, the extended version of the SDQ was used, which is referred to as the “impact supplement.”37 This supplement includes questions to assess difficulties in a number of areas, including emotions, concentration, behavior, and getting along with others. The extended SDQ has also demonstrated validity in a resource-poor setting, in which the area under the ROC curve for the extended SDQ was 0.87 for the parent version and 0.89 for discriminating between clinic and community samples of children based in Dhaka, Bangladesh.36 The parent and youth report versions of the extended SDQ were used in this study. Those who had indicated having any difficulty in “emotions, concentration, behavior, or being able to get along with other people” were compared to those who did not report this difficulty for the analysis.

Symptoms of depression in parents/caregivers

The depression subscale of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 (HSCL-25) was used to assess the level of depressive symptomatology in the parents/caregivers.38 The depression subscale of the HSCL-25 has 15 items designed to obtain severity of symptomatology on a scale of “1” (not at all) to “4” (extremely) with respect to the degree to which the symptom bothered the respondent in the past week. It has been validated against criteria for major depressive disorder according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) of the American Psychiatric Association (DSM-IV and DSM-III versions)39,40 in a number of cross-cultural contexts.41,42 Among HIV-positive women in Tanzania, the 15-item depression subscale demonstrated validity compared to psychiatrists' assessment of major depressive disorder using the structured clinical interview for the DSM-IV.42 Caregivers who scored in the highest tertile for the depression subscale of the HSCL were compared to those who scored in the bottom two tertiles for the purposes of this analysis.

Other assessments

Other variables included sociodemographic information for the youth and their parents/caregivers, economic status of the household, social support for youth and caregivers, and role functioning for caregivers. Social support for youth was measured using the Provisions of Social Relation (PSR) scale to assess support from family members as well as friends.43 For social support of parents/caregivers an assessment by Gielen et al.44 was used that includes dimensions of: (1) having a confidant; (2) number of close friends and relatives (network size); and (3) level of instrumental support. In addition, role functioning of parents/caregivers was assessed using the role functioning subscale of the ACTG Short Form-21 (SF-21), which focuses on the extent the person's health keeps him/her from performing daily activities.45

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics, including frequencies, medians, means and standard deviations, were calculated for sociodemographic characteristics, economic factors, and prevalence of psychiatric symptoms among youth and parents/caregivers. Univariate analyses were performed to measure the associations between the parents' depressive symptoms and their children's level of psychological symptomatology and psychosocial functioning using χ2 tests, odds ratios (OR), and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Multivariable logistic regression was used to control for confounding variables in the analysis. Given that more than one child from the same family was included in the sample for a subset of youth, the GENMOD procedure in SAS was used to account for correlations between siblings by using an exchangeable variance-covariance structure. The multivariate modeling strategy was based on the “change-in-estimate” approach described by Greenland,46 in which those potential confounding variables that changed the exposure-disease (e.g., parents' depressive symptoms and children's symptom levels) OR estimate by more than 5% were retained in the final multivariate regression models. The percent change was reduced from 10% as suggested by Greenland46 to 5% to provide a more conservative analysis of confounding. Variables considered as potential confounding variables in the analysis included: child's age, child's gender, parents'/caregivers' role functioning, rural/urban residence, caregivers' educational level as well as socioeconomic status, social support, death of a parent from HIV, youth not living with a parent, living with a step-parent, and living with a grandparent. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).47

Results

Approximately half of the youth who participated in the study were female (51.4%) and the mean age was 13 years (range, 10–17). Most youth lived with their mothers (79.6%) and only 33.6% lived with their fathers. Nearly 10% lived with neither parent and 1.4% represented child-headed households. Grandparents frequently lived in the home, with youth reporting 21.8% of households having a grandmother and 12.6% having a grandfather. Nearly 16% of youth were orphaned by HIV, of whom 12.8% had lost one parent and over 3% had lost both parents (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics for HIV-Affected Youth and Caregivers

| Child characteristics | n (%) or Mean/median (range) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (n = 490)a | Female | 252 (51.4%) |

| Male | 238 (48.6%) | |

| Age (n = 488) | 10–13 | 291 (59.6%) |

| 14–17 | 197 (40.4%) | |

| Current guardian (n = 492) | Mother | 385 (79.6%) |

| Father | 157 (33.6%) | |

| Stepmother | 24 (5.2%) | |

| Stepfather | 76 (16.6%) | |

| Grandmother | 101 (21.8%) | |

| Grandfather | 58 (12.6%) | |

| Aunt | 74 (15.9%) | |

| Uncle | 57 (12.3%) | |

| No parent | 49 (9.9%) | |

| No adult | 7 (1.4%) | |

| Child experienced death of parent from HIV (n = 485) | Yes, one parent | 62 (12.8%) |

| Yes, both parents | 15 (3.1%) |

| Caregiver characteristics | n (%) or Mean/median (range) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (n = 319)b | Mean age in years (range) | 39.4 (19–84) |

| Gender (n = 320) | Female | 234 (73.1%) |

| Male | 86 (26.9%) | |

| Residence (n = 318) | Countryside | 132 (41.5%) |

| Small town | 75 (23.6%) | |

| Large city | 111 (34.9%) | |

| Education level (n = 319) | Never attended school | 121 (37.9%) |

| Current marital status (n = 320) | Married | 54 (16.9%) |

| Living with a partner | 122 (38.1%) | |

| Single | 47 (14.7%) | |

| Separated | 44 (13.7%) | |

| Divorced | 0 (0%) | |

| Widowed | 53 (16.6%) | |

| Average family income (USD) per month (n = 318) | 0 | 38 (11.9%) |

| $0.05–$6.25 | 17 (5.4%) | |

| $6.26–$12.50 | 23 (7.2%) | |

| $12.51–$18.75 | 17 (5.4%) | |

| $18.76–$25.00 | 15 (4.7%) | |

| $25.01–$37.45 | 34 (10.7%) | |

| $37.46–$43.70 | 13 (4.1%) | |

| $43.71–$50.00 | 16 (5.0%) | |

| >$50 | 87 (27.4%) | |

| Don't know | 58 (18.2%) | |

| Median Income | $43.71–$50.00 | |

| Number of people sharing family income (n = 276) | Median (range) | 6 (2–16) |

| Income spent on food (n = 282) | Less than 50% of income spent on food | 15 (5.3%) |

| Approximately 50% of income spent on food | 25 (8.9%) | |

| Most of income spent on food | 114 (40.4%) | |

| All income spent on food | 89 (31.6%) | |

| Type of roof (n = 319) | Aluminum roof | 257 (80.6%) |

| Thatched or Hay roof | 55 (17.2%) | |

| Concrete roof | 7 (2.2%) | |

| Wood roof | 0 |

For some categories denominator is less than 492 due to missing data.

Denominators are less than 330 due to missing data.

Although most youth reported that they had ever attended school (96.5%), school was frequently delayed, interrupted or terminated prematurely due to lack of money for school fees. Other sociodemographic and economic characteristics also reflected pervasive poverty. Over 54% of caregivers indicated that the monthly household income was less than $50 per month; with a median household size of 6.2 persons, this falls far below the international poverty line of $1 per person per day for many households. The median household size was 2.2 rooms (3 persons per room on average). Over 17% lived in a house with a thatched roof and only 41.2% had latrines. Approximately 80% of households spent at least half of their income on food and 31.6% reported spending all of their income on food. Over 31% of caregivers indicated that they engaged in farming, 21.3% were market vendors, and 38% reported being unemployed (Table 1).

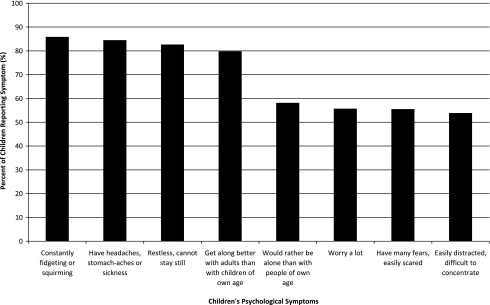

The youth demonstrated very high levels of self-reported anxiety; the most common symptoms reported were constant fidgeting (85.9%), headaches/stomachaches (84.5%), and restlessness (82.7%). Other symptoms of anxiety that were frequently reported included: worrying a lot (55.7%), having many fears/easily scared (55.5%), and nervousness in new situations (39.8%). The most prevalent depressive symptoms among the youth were difficulty concentrating (53.9%) and feeling isolated—“rather be alone than with people own age” (58.2%) and “gets along better with adults than with children own age” (79.8%). Nearly 48% reported often feeling unhappy, depressed, or tearful. Externalizing behaviors were also observed, but were overall less frequent than internalizing symptoms, with only 1.4% reporting “not true” for the item “you usually do as you are told” and 14.3% responding “not true” for “you usually share with others.” The most frequent externalizing behavior observed in this population was “getting very angry/often losing your temper” (48.2%; Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Most prevalent psychological symptoms reported by children.

Youth who were HIV positive (n = 20) compared with those who were HIV-negative in the study population demonstrated a higher likelihood of “problems with attention/ difficulty in completing work” (65.0% versus 41.7%, p = 0.039). They also were more likely to report not offering help if someone was hurt, upset or ill (55.0% versus 30.2%, p = 0.019), suggesting a greater degree of isolation among the HIV-positive youth. We also compared those who were HIV positive and HIV negative for the overall SDQ symptom scale (self-report), and observed that youth who were HIV positive were over three times more likely to have an elevated level of psychological symptoms (in the highest tertile of the distribution) compared with their HIV-negative peers (OR = 3.0; 95% CI: 1.1–8.2).

According to youth self-report, 28.8% felt that the symptoms they reported resulted in difficulties in psychosocial functioning (i.e., difficulties in “emotions, concentration, behavior, or being able to get along with other people”). Among those youth who had reported difficulties, 66.7% indicated that it was for longer than a year, 26.6% reported that these day-to-day difficulties distressed them a great deal, and 22.0% indicated that these difficulties made life harder for those around them (e.g., family, friends, teachers, etc.) a great deal. Over 22% of youth reported that they did not have a confidant to share any of these concerns or other things happening in their lives.

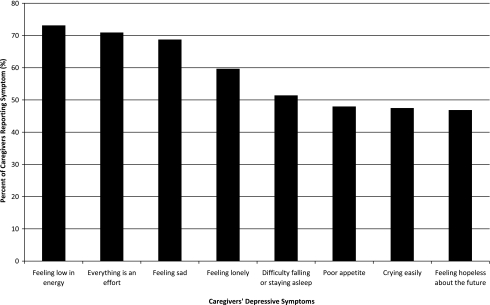

Among their parents/caregivers, of whom 88.7% were HIV positive, the most common depressive symptoms reported as “quite a bit” or “extremely” were feeling: low in energy (73.1%), “everything is an effort” (70.9%), and sadness (69%). Other prevalent symptoms included feeling lonely (59.7%), crying easily (47.5%), and feeling hopeless about the future (46.9%). Nearly 43% had feelings of worthlessness and over 19% of parents/caregivers reported “thoughts of ending your life” (see Figure 2 for most prevalent symptoms among caregivers). Nearly 40% indicated that they did not have a confidant to talk about these symptoms or other aspects of their personal lives. For role functioning, 53.1% reported that their health prevented them from working at a job, doing work around the home, or going to school, with 12.8% indicating that this occurred “all of the time.” Similarly, 57.5% reported that they have been unable to do certain kinds or amounts of work, with 11.6% this problem existed “all of the time.”

FIG. 2.

Most prevalent depressive symptoms reported by caregivers.

For unadjusted analyses, parents with higher levels of depressive symptoms reported more psychological symptoms in their children (crude OR = 2.1; 95% CI: 1.4–3.2). However, results from youth report also suggested an association (crude OR = 1.4; 95% CI: 0.96–2.1; data not shown), indicating that this relationship cannot entirely be explained by the parents' depressive symptoms. After controlling for confounding in multivariate analysis (Table 2), the strength of the association between parents' depressive symptoms and children's psychological symptoms increased. This was evident for the association between parents' depressive symptoms and children's psychological symptoms according to parents' report (OR = 2.4; 95% CI: 1.6–3.6, Model 1), after controlling for urban/rural residence, as well as youth report (OR = 1.6; 95% CI: 1.0–2.5, Model 2), after controlling for urban/rural residence as well as living with a stepparent, and role functioning of their primary caregiver. Although HIV-positive status among the youth was associated with a higher level of psychological symptoms (OR = 3.0), we also considered this variable as a potential confounding variable in the multivariate analysis. The OR estimates for the associations between caregivers' depressive symptoms and children's psychological symptoms (according to youth as well as caregiver report) did not vary by greater than 5%; therefore, this factor was not included in the final models described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Multivariate Analysis of Association of Caregivers' Depressive Symptoms and Children's Psychological Symptoms and Psychosocial Functioning

| Model | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Child psychological symptoms (adult report) (n = 476) | ||

| Parent's depressive symptoms | 2.4 | (1.6, 3.6) |

| Location of residence (rural/urban) | 1.8 | (1.1, 2.7) |

| Model 2: Child psychological symptoms (self-report) (n = 444) | ||

| Parent's depressive symptoms | 1.6 | (1.0, 2.5) |

| Role functioning of caregiver | 0.75 | (0.48, 1.2) |

| Location of residence (rural/urban) | 1.5 | (0.95, 2.3) |

| Living with stepparent | 1.2 | (0.75, 2.0) |

| Model 3: Child psychosocial functioning (adult report) (n = 443) | ||

| Parent's depressive symptoms | 1.6 | (0.96, 2.6) |

| Role functioning of caregiver | 0.69 | (0.42, 1.1) |

| Location of residence (rural/urban) | 2.1 | (1.2, 3.4) |

| Death of a parent from HIV | 1.9 | (1.0, 3.8) |

| Living with no parent | 1.4 | (0.66, 2.8) |

| Living with stepparent | 1.8 | (1.0, 3.2) |

| Living with grandparent | 0.96 | (0.55, 1.7) |

| Model 4: Child psychosocial functioning (self-report) (n = 448) | ||

| Parent's depressive symptoms | 1.3 | (0.83, 2.0) |

| Social support (financial) for caregiver | 1.9 | (1.2, 3.1) |

| Death of parent from HIV | 1.7 | (0.94, 3.2) |

| Living with no parent | 1.3 | (0.64, 2.7) |

| Living with stepparent | 1.3 | (0.72, 2.3) |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

In univariate analyses parents' level of depressive symptoms was not associated with the child's level of psychosocial functioning, according to parental report (crude OR = 1.3; 95% CI: 0.83–2.0) or youth report (crude OR = 1.4; 95% CI: 0.89–2.1; data not shown). However, after controlling for confounding variables in multivariate analyses, the findings for this association were marginally significant for parental report of their children's psychosocial functioning (OR = 1.6; 95% CI: 0.96–2.6). Confounding variables included rural/urban residence (OR = 2.1; 95% CI: 1.2–3.4), living with a stepparent (OR = 1.8; 95% CI: 1.0–3.2), and death of a parent from HIV (OR = 1.9; 95% CI: 1.0–3.8; Table 2, Model 3).

Since the majority of the parents/caregivers in the study population were HIV positive, we examined these relationships in the subsample of youth whose parents/caregivers were HIV positive. These associations were largely consistent with what was observed for the broader study population. For the HIV-positive subsample, the association between parents' depressive symptoms and children's psychological symptoms was comparable (OR = 2.4; 95% CI: 1.6–3.8, Model 1) after controlling for confounding variables (Table 3). For the associations between youth's psychosocial functioning and the parents' depressive symptoms, the associations were attenuated for parental report (OR = 1.5; 95% CI: 0.85–2.5, Model 3) as well as for youth's self-report (OR = 1.4; 95% CI: 0.87–2.2, Model 4) among the group whose parents were HIV-positive compared with the entire study population.

Table 3.

Multivariate Analysis of Association of Caregivers' Depressive Symptoms and Children's Psychological Symptoms and Psychosocial Functioning, HIV-Positive Caregivers

| Model | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Child psychological symptoms (adult report) (n = 427) | ||

| Parent's depressive symptoms | 2.4 | (1.6, 3.8) |

| Location of residence (rural/urban) | 1.7 | (1.1, 2.8) |

| Socioeconomic status | 0.62 | (0.38, 1.0) |

| Model 2: Child psychological symptoms (self-report) (n = 427) | ||

| Parent's depressive symptoms | 1.7 | (1.1, 2.7) |

| Role functioning of caregiver | 0.67 | (0.42, 1.1) |

| Location of residence (rural/urban) | 1.5 | (0.96, 2.3) |

| Model 3: Child psychosocial functioning (adult report) (n = 396) | ||

| Parent's depressive symptoms | 1.5 | (0.85, 2.5) |

| Role functioning of caregiver | 0.68 | (0.39, 1.2) |

| Location of residence (rural/urban) | 1.6 | (0.93, 2.9) |

| Socioeconomic status | 4.4 | (2.4, 7.8) |

| Living with stepparent | 1.8 | (1.0, 3.3) |

| Living with grandparent | 0.87 | (0.49, 1.6) |

| Model 4: Child psychosocial functioning (self-report) (n = 399) | ||

| Parent's depressive symptoms | 1.4 | (0.87, 2.2) |

| Child's age | 0.53 | (0.33, 0.85) |

| Socioeconomic status | 3.9 | (2.4, 6.5) |

| Living with stepparent | 1.1 | (0.61, 1.9) |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

In the current study, high levels of symptoms of anxiety were observed in this population of youth affected by HIV, with constant fidgeting, headaches/stomachaches, and restlessness being reported by over 80% of youth. A review by Donenberg et al.,22 indicates that youth affected by HIV have internalizing symptoms, including anxiety, depression, and social withdrawal. For youth in central Haiti, their daily functioning as well as their school performance can be negatively affected as a result of these symptoms.23–27,48

The high levels of anxiety experienced by youth were coupled with a significant degree of depressive symptoms among their caregivers, nearly 89% of whom were HIV positive and approximately 73% of whom were women. These symptoms were not only common but severe; over two thirds experienced sadness “quite a bit” or “extremely frequently” and nearly 20% reported this level of distress related to “thoughts of ending your life.” While significant levels of depression or depressive symptoms have also been observed for HIV-positive populations,17–19,49,50 particularly among women,20,51 the significant level of these symptoms has not been described in Haiti and is not being addressed by the majority of HIV programs within Haiti or other resource-poor settings.

This study demonstrates an association between parents' depressive symptoms and their children's symptoms that ranged from 1.6- to 2.4-fold, suggesting that parents' depressive symptoms are associated with approximately a 2-fold increase in risk of children's symptoms of anxiety, depression, anger, and loss of concentration. A U.S.-based study among HIV-affected youth demonstrated that maternal depression was more significantly associated with anxiety in their early adolescent children (ages 10–14; β = 0.16; p ≤ 0.001) compared with similar maternal symptoms in caregivers of youth not affected by HIV. The association between maternal depression resulting in internalizing symptoms (β = 0.35; p ≤ 0.001) and externalizing behaviors (β = 0.29; p ≤ 0.001) among HIV-affected youth has also been reported by Mellins et al.52 Among HIV-affected adolescents in New York, depressive symptoms were significantly associated with parental depression (p = 0.004).53

In addition to psychological symptomatology, nearly 30% of youth expressed that these symptoms had affected their daily psychosocial functioning. Although the magnitude of the associations between parents' depressive symptoms and their children's psychosocial functioning (Models 3 and 4, Table 2) was not as strong as the associations with their children's psychological symptoms (Models 1 and 2, Table 2), the relationships were in the same direction and marginally significant. Interestingly, the associations between the parents' depressive symptoms and their children's psychosocial functioning were affected by other factors to a much greater degree compared to the affect on children's symptoms. For example, the impact that the parents' symptoms had on the children's level of psychosocial functioning was affected by the living conditions of the child. When the death of a parent from HIV was controlled for the association between parents' symptoms and children's psychosocial functioning increased. When four family-related factors were simultaneously included in the final model, the overall strength of the association between parents' depressive symptoms and their children's psychosocial functioning increased. The strongest family-related factors associated with children's psychosocial functioning were death of a parent from HIV (OR = 1.9) and living with a stepparent (OR = 1.8).

In a qualitative study among youth orphaned by HIV in South Africa, bereavement over the loss of a parent was an important factor linked with emotional or behavioral problems. Youth and caregivers in this study also referred to the quality of caregiving and the home environment as having beneficial or harmful effects on youth's mental health, depending on the conditions at home.54 Although some studies have shown that orphan status does not place youth at greater risk of negative health outcomes compared to other youth in high HIV burden areas,55–59 other studies have observed a negative impact.54,60–64

Despite this varying evidence in the literature, at the service provision level the child's loss of a parent should still be considered by clinicians in terms of addressing any current situation as well as preventing future health problems. It is widely known that a death of a parent can have a significant impact on the child's well-being65–69 this has also been documented among youth who have lost their parents to HIV. In a fairly large study by Cluver et al.54 among adolescents in South Africa, elevated rates of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, conduct problems, and delinquency were observed among youth whose parents died of HIV. This evidence is corroborated by earlier studies that demonstrated higher rates of depression and anxiety among youth who lost a parent to HIV compared to children from the same community who were not orphans.14,61,62 In a study of rural Chinese children living in orphanages, the youth described feelings of depression, fear, confusion, anger as well as engaging in fights with other youth in school.70 In addition, youth's psychological distress may have an effect on risk of HIV infection. In particular, “externalizing” can result in a higher likelihood of engagement in HIV risk behaviors in adolescents.21,71–73 Internalizing symptoms, such as depression, may be related to lower self-esteem and a reduction in self-care—also possibly increasing the risk of acquiring a sexually transmitted infection in youth.74–76

The youth's living situation or family functioning can have a short-term as well as long-term impact on a child.77–83 In addition to the evidence of the association between parents' level of depressive symptoms and youth's psychological distress, the impact on the child's psychosocial functioning appears to be greater when parental support is lost through death or significantly changed through inclusion of a stepparent; although these associations were stronger for the caregiver report of psychosocial functioning versus youth's self-report. Patel et al.84 describe the importance of family functioning in relation to children's mental health. In particular, family indicators that have an impact on the mental health of children include not only parental mental health, but also parent–child attachment, family cohesion, and supervision of children's activities, all of which can be affected by changes in family structure, such as the addition of a stepparent and/or death of a parent. Similar to the results from the present study, Lee et al.85 observed that depressive symptoms among adolescents affected by HIV in New York were positively associated with death of a parent as a result of AIDS. In the same cohort of youth, Lee et al.53 also reported an association between the youth's living situation and depressive symptoms, offering evidence for the important role of the home environment even after they controlled for level of parental depression.

For children's self-report of psychosocial functioning, although the association between this outcome and the parents' depressive symptoms is attenuated compared to adult report, a key factor is social support of the parent/caregiver in terms of instrumental support. For those parents who reported that they did not have someone who could lend them money when they needed it, there was a 1.9-fold increase in risk of poor psychosocial functioning among the youth. In this regard, economic support of the family may have a protective effect on the youth's psychosocial functioning. Other studies have shown a positive association between household's low socioeconomic status and psychological symptoms and/or poor psychosocial functioning in children.74,86–90 These findings suggest that poverty reduction strategies may promote not only positive physical health outcomes, but may improve psychosocial functioning among youth affected by HIV.

Last, poor psychosocial functioning of children can worsen parents' anxiety and depression. This can have an impact on the treatment and prognosis of disease. Among HIV-positive individuals, depression has been shown to be associated with poor antiretroviral regimen adherence,91,92 increased progression of HIV,93,94 and mortality.20,95 Thus, for psychosocial functioning of both parent and child and for potentially improving physical health outcomes, mental health should be considered an important aspect of the treatment of HIV.

There are a number of limitations in the study, including the cross-sectional design since the analysis relied on baseline data. In this regard, one cannot determine the temporal relationship between parents' depressive symptoms and children's psychosocial functioning from this study. In addition, given the high level of depressive symptoms among caregivers at baseline, there may be a possibility that parents had overreported psychological symptoms in their children. However, the positive relationships between parents' depressive symptoms and children's psychosocial outcomes were largely observed in analyses that included children's self-report of their own status. Another limitation relates to the missing data in the multivariate analysis. The greatest degree of missing data was for Model 3 (Table 2), where 49 observations were dropped because of missing data. Distribution of most sociodemographic factors was similar for these youth compared to those included in Model 3 (n = 443). However, differences were observed comparing youth who were missing versus those who were included for the home environment, whereby youth who were missing were less likely to have lived with their father and more likely to have lived with their grandmother, grandfather, aunt, or uncle.

However, this pattern of missing data would bias the results toward the null. Finally, the instruments used were not validated for use in central Haiti; although the findings from the present study, demonstrating associations in the expected direction, offer a degree of face validity of these measures in this context.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates a high level of psychological vulnerability among children affected by HIV and their caregivers and that depressive symptomatology among parents/caregivers may negatively impact youth symptoms and psychosocial functioning. In addition, the psychosocial functioning of youth can impact the levels of depression in their parents/caregivers. These findings were observed despite all of the participants having access to free and comprehensive HIV treatment including antiretroviral therapy and suggest an important role for interventions specifically designed to address anxiety, depression and parent–child relationships within the context of medical care of HIV.

Evidence for a family-centered approach to services for children in high HIV burden settings has been put forth by the Joint Learning Initiative on Children and HIV/AIDS (JLICA).96 In addition, there is evidence that children/youth orphaned within the context of HIV are not worse off economically compared to other youth in high HIV burden settings.97 However, the potential impact of the death of a parent on a child's psychosocial functioning remains a critical issue at the service delivery level. The current findings demonstrated that a youth's loss of a parent and living with a stepparent significantly increased the risk of poor psychosocial functioning. This suggests that while a family-focused approach may be critical for addressing the needs of youth affected by HIV/AIDS, a deeper understanding of the youth's experience of the death of a parent as well as the family structure and functioning in the new environment is important when offering support for families in high HIV burden areas. This indicates that there is a need for enhanced psychosocial support of families affected by HIV/AIDS, in addition to economic support.

In the present study in central Haiti, the poverty level was extreme and severity of poverty within the family was associated with lower psychosocial functioning by youth self-report. Richter et al.97 indicated that poverty-reduction strategies, such as cash transfers to families in high HIV burden areas, will greatly reduce the impact of HIV in resource-poor communities. In addition, the data also suggest the need to assess the family's circumstances when offering services to ensure that youth are receiving the appropriate care for the situation, since a wide range of family functioning has been observed in high HIV burden settings, including cases of child neglect and abuse.55

Implications for services suggest that there is a greater need for psychosocial support for HIV-affected families within the context of expanding HIV-related services in resource-limited settings. In the United States, psychosocial interventions among HIV-affected families have demonstrated effectiveness in enhancing youth's short- and long-term outcomes.21,98 A holistic approach to HIV prevention and care (i.e., integrated services that are family-focused) that addresses the family's needs (e.g., supporting parents/caregivers, promoting family functioning, addressing physical as well as mental health needs, and offering financial support when needed) as well as the broad range of needs for youth (access to school, physical health needs, promotion of mental health, etc.), may be necessary to reduce the burden of the HIV pandemic and offset the negative consequences of HIV infection for current and future generations.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all of the youth and parents/caregivers who participated in the study and the staff at Partners In Health, Zanmi Lasante, and Harvard Medical School who contributed significantly to this study. Special thanks are extended to Marianne Appolon, Anna Casey, Navdya Clerveaux, Evens Coqmar, Wilder Dubuisson, Naomie Emmanuel, Oupet Evenson, Jinette Fetiere, John Guillaume, Thierry Jean-Paul, Wesler Lambert, Lucinda Leung, Joly Laramie, Fernet Leandre, Patrice Nevil, Ernst Origene, Sherley Piard, Jean Renald Pierre, Marie Lourdes Pierre, and Rivot St. Fleur. This study was supported by a grant provided by the National Institute of Mental Health (R21 MH076447). The HIV treatment program has been funded by the U.S. President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria (GFATM). The work at Zanmi Lasante has been made possible in large part through the generosity of private foundations and donors, especially Thomas J. White.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.UNAIDS. 2008 Report on the global AIDS epidemic. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tarantola D. Gruskin S. Children confronting HIV/AIDS: Charting the confluence of rights and health. Health Hum Rights. 1998;3:60–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morgan S. Response for all AIDS affected children, not AIDS orphans alone. AIDS Anal Afr. 2000;10:3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foster G. Williamson J. A review of current literature of the impact of HIV/AIDS on children in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2000;14(Suppl 3):S275–S284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.oster G. Children who live in communities affected by AIDS. Lancet. 2000;367:700–701. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68273-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stein JA. Rotheram-Borus MJ. Lester P. Impact of parentification on long-term outcomes among children of parents with HIV/AIDS. Fam Process. 2007;46:317–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2007.00214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richter L. Foster G. Sherr L. Where the Heart Is: Meeting the Psychosocial Needs of Young Children in the Context of HIV/AIDS. The Hague, The Netherlands: Bernard van Leer Foundation; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao G. Li X. Fang X. Zhao J. Yang H. Stanton B. Care arrangements, grief and psychological problems among children orphaned by AIDS in China. AIDS Care. 2007;19:1075–1082. doi: 10.1080/09540120701335220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rotheram-Borus MJ. Flanery D. Rice E. Lester P. Families living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2005;17:978–987. doi: 10.1080/09540120500101690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brackis-Cott E. Kang E. Dolezal C. Abrams EJ. Mellins CA. The impact of perinatal HIV infection on older school-aged children's and adolescents' receptive language and word recognition skills. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2009;23:415–421. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown LK. Lourie KJ. Children and adolescents living with HIV and AIDS: A review. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2000;41:81–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krener P. Miller FB. Psychiatric response to HIV spectrum disease in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1989;28:596–605. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198907000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stein JA. Riedel M. Rotheram-Borus MJ. Parentification and its impact on adolescent children of parents with AIDS. Fam Proc. 1999;38:193–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1999.00193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Earls F. Raviola GJ. Carlson M. Promoting child and adolescent mental health in the context of the HIV/AIDS pandemic with a focus on sub-Saharan Africa. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49:295–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Birdthistle I. Understanding the needs of orphans and other children affected by HIV and AIDS in Africa: The state of the science [working draft] Washington: USAID; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith Fawzi MC. Kaaya SF. Mbwambo J, et al. Multivitamin supplementation in HIV- positive pregnant women: Impact on depression and quality of life in a resource-poor setting. HIV Med. 2007;8:203–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2007.00454.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pence B. Reif S. Whetten K, et al. Minorities, the poor, and survivors of abuse: HIV-infected patients in the US Deep South. South Med J. 2007;100:1114–1122. doi: 10.1097/01.smj.0000286756.54607.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boarts JM. Sledjeski EM. Bogart L. Delahanty D. The differential impact of PTSD and depression on HIV disease markers and adherence to HAART among people living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2006;10:253–261. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whetten K. Reif S. Whetten R. Murphy-McMillan LK. Trauma, mental heath, distrust, and stigma among HIV-positive persons: Implications for effective care. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:531–538. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31817749dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ickovics JR. Hamburger ME. Vlahov D, et al. Mortality, CD4 cell count decline, and depressive symptoms among HIV-seropositive women: Longitudinal analysis from the HIV Epidemiology Research Study. JAMA. 2001;285:1466–1474. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.11.1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rotheram-Borus MJ. Stein JA. Lin YY. Impact of parent death and an intervention on the adjustment of adolescents whose parents have HIV/AIDS. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:763–773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Donenberg GR. Pao M. Youths and HIV/AIDS: Psychiatry's role in a changing epidemic. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44:728–747. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000166381.68392.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Biggar H. Forehand R. Chance MW. Morse E. Morse P. Stock M. The relationship of maternal HIV status and home variables to academic performance of African American children. AIDS Behav. 2000;4:241–252. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Esposito S. Musetti LE. Musetti MC, et al. Behavioral and psychological disorders in uninfected children age 6 to 11 years born to human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive mothers. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1999;20:411–427. doi: 10.1097/00004703-199912000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Forehand R. Steele R. Armistead L. Morse E. Simon P. Clark L. The Family Health Project: Psychosocial adjustment of children whose mothers are HIV infected. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:513–520. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.3.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Forsyth BW. Damour L. Nagler S. Adnopoz J. The psychological effects of parental human immunodeficiency virus infection on uninfected children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1996;150:1015–1020. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170350017002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee MB. Rotheram-Borus MJ. Parents' disclosure of HIV to their children. AIDS. 2002;16:2201–2207. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200211080-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.The White House Office of the Press Secretary. Press Briefing by Press Secretary Robert Gibbs and Deputy Secretary of State Jack Lew [press briefing] Washington, D.C.: The White House; May 5, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farmer P. Léandre F. Mukherjee JS, et al. Community-based approaches to HIV treatment in resource-poor settings. Lancet. 2001;358:404–409. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)05550-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fraser HS. Jazayeri D. Nevil P, et al. An information system and medical record to support HIV treatment in rural Haiti. BMJ. 2004;329:1142–1146. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7475.1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goodman R. Psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:1337–1345. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200111000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elander J. Rutter M. Use and development of the Rutter Parents' and Teachers' Scales. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 1995;5:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klasen H. Woerner W. Wolke D, et al. Comparing the German versions of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ-Deu) and the Child Behavior Checklist. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;9:271–276. doi: 10.1007/s007870070030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koskelainen M. Sourander A. Kaljonen A. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire among Finnish school-aged children and adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;9:277–284. doi: 10.1007/s007870070031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goodman R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1997;38:581–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mullick MS. Goodman R. Questionnaire screening for mental health problems in Bangladeshi children: A preliminary study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2001;36:94–99. doi: 10.1007/s001270050295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goodman R. The extended version of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire as a guide to child psychiatric caseness and consequent burden. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1999;40:791–799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Derogatis LR. Lipman RS. Rickels K. Uhlenhuth EH. Covi L. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): A self-report symptom inventory. Behav Sci. 1974;19:1–15. doi: 10.1002/bs.3830190102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 40.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3rd. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mollica RF. de Marneffe D. Tu B, et al. Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 Manual: Cambodian, Laotian and Vietnamese versions. Washington, D.C.: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaaya SF. Fawzi MC. Mbwambo JK. Lee B. Msamanga GI. Fawzi W. Validity of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 amongst HIV-positive pregnant women in Tanzania. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;106:9–19. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.01205.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Turner JB. Frankel G. Levin DM. Social support: conceptualization, measurement, and implications for mental health. In: Greenley JR, editor; Simmons RG, editor. Research in Community and Mental Health. Vol. 3. Greenwich, CT; JAI Press, Inc.: 1983. pp. 67–111. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gielen AC. McDonnell KA. Wu AW. O'Campo P. Faden R. Quality of life among women living with HIV: The importance violence, social support, and self care behaviors. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52:315–322. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00135-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Crystal S. Fleishman JA. Hays RD. Shapiro MF. Bozzette SA. Physical and role functioning among persons with HIV: Results from a nationally representative survey. Med Care. 2000;38:1210–1223. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200012000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Greenland S. Modeling and variable selection in epidemiologic analysis. Am J Public Health. 1989;79:340–349. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.3.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Statistical Analysis Software (SAS), version 9.1. Cary, NC: The SAS Institute; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Forehand R. Jones DJ. Kotchick BA, et al. Noninfected children of HIV-infected mothers: A 4-year longitudinal study of child psychosocial adjustment and parenting. Behav Ther. 2002;33:579–690. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bing EG. Burnam MA. Longshore D. Psychiatric disorders and drug use among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:721–728. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.8.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spiegel D. Israelski DM. Power R, et al. Acute stress disorder, PTSD, and depression in a clinic-based sample of patients with HIV/AIDS. J Psychosom Res. 2003;55:128. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cook JA. Grey D. Burke J, et al. Depressive symptoms and AIDS-related mortality among a multisite cohort of HIV-positive women. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1133–1140. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mellins CA. Brackis-Cott E. Dolezal C. Leu CS. Valentin C. Meyer-Bahlburg HFL. Mental health of early adolescents from high-risk neighborhoods: The role of maternal HIV and other contextual, self-regulation, and family factors. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008;33:1065–1075. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee SJ. Detels R. Rotheram-Borus MJ. Duan N. Lord L. Depression and social support among HIV-affected adolescents. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2007;21:409–417. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cluver L. Gardner F. Operatio D. Psychological distress among AIDS-orphaned children in urban South Africa. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48:755–763. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cluver L. Gardner F. Risk and protective factors for psychological well-being of children orphaned by AIDS in Cape Town: A qualitative study of children and caregivers' perspectives. AIDS Care. 2007;19:318–325. doi: 10.1080/09540120600986578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Parikh A. DeSilva MB. Cakwe M, et al. Exploring the Cinderella myth: Intrahousehold differences in child well-being between orphans and non-orphans in Amajuba District, South Africa. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 7):S95–S103. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000300540.12849.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rivers J. Mason J. Silveste E. Gillespie S. Mahy M. Monasch R. Impact of orphanhood on underweight prevalence in sub-Saharan Africa. Food Nutr Bull. 2008;29:32–42. doi: 10.1177/156482650802900104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sarker M. Neckermann C. Muller O. Assessing the health status of young AIDS and other orphans in Kampala, Uganda. Trop Med Int Health. 2005;10:210–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lindblade KA. Odhiambo F. Rosen DH. DeCock KM. Health and nutritional status of orphans <6 years old cared for by relatives in western Kenya. Trop Med Int Health. 2003;8:67–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.00987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nyamukapa CA. Gregson S. Lopman B, et al. HIV-associated orphanhood and children's psychosocial distress: Theoretical framework tested with data from Zimbabwe. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:133–141. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.116038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Makame V. Ani C. Grantham-McGregor S. Psychological well-being of orphans in Dar El Salaam, Tanzania. Acta Paediatr. 2002;91:459–465. doi: 10.1080/080352502317371724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Atwine B. Cantor-Graar E. Bajunirwe F. Psychological distress among AIDS orphans in rural Uganda. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:555–564. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ruiz-Casares M. Thomas BD. Rousseau C. The association of single and double orphanhood with symptoms of depression among children and adolescents in Namibia. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;18:369–376. doi: 10.1007/s00787-009-0739-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Miller CM. Gruskin S. Subramanian SV. Heymann J. Emerging health disparities in Botswana: Examining the situation of orphans during the AIDS epidemic. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:2476–2486. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dowdney L. Annotation: Childhood bereavement following parental death. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2000;41:819–830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Furman E. A Child's Parent Dies. New Haven: Yale University Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bowlby J. Attachment and Loss. New York: Basic Books; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Caplan MG. Douglas VL. Incidence of parental loss in children with depressed mood. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1969;10:225–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1969.tb02083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cerel J. Fristad MA. Verducci J. Weller RA. Weller EB. Childhood bereavement: Psychopathology in the 2 years postparental death. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:681–690. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000215327.58799.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhao Q. Li XM. Kaljee LM. Fang XY. Stanton B. Zhang LY. AIDS orphanages in China: reality and challenges. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2009;23:297–303. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Abrantes AM. Strong DR. Ramsey SE. Kazura AN. Brown RA. HIV-risk behaviors among psychiatrically hospitalized adolescents with and without comorbid SUD. J Dual Diagn. 2006;2:85–100. doi: 10.1300/J374v02n03_08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Caminis A. Henrich C. Ruchkin V. Schwab-Stone M. Martin A. Psychosocial predictors of sexual initiation and high-risk sexual behaviors in early adolescence. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2007;1:14. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-1-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Koopman C. Rosario M. Rotheram-Borus MJ. Alcohol and drug use and sexual behaviors placing runaways at risk for HIV infection. Addict Behav. 1994;19:95–103. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)90055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brooks-Gunn J. Duncan GJ. The effects of poverty on children. Future Child. 1997;7:55–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Brown A. Yung A. Cosgrave E, et al. Depressed mood as a risk factor for unprotected sex in young people. Australas Psychiatry. 2006;14:310–312. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1665.2006.02291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hutton HE. Lyketsos CG. Zenilman JM. Thompson RE. Erbelding EJ. Depression and HIV risk behaviors among patients in a sexually transmitted disease clinic. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:912–914. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.5.912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Costello DM. Swendense J. Rose JS. Dierker LC. Risk and protective factors associated with trajectories of depressed mood from early adolescence to early adulthood. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76:173–183. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shek DT. The relation of family functioning to adolescent psychological well-being, school adjustment, and problem behavior. J Genet Psychol. 1997;158:467–479. doi: 10.1080/00221329709596683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.dewuya AO. Ologun YA. Factors associated with depressive symptoms in Nigerian adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39:105–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pederson S. Revenson TA. Parental illness, family functioning and adolescent well-being: A family ecology framework to guide research. J Fam Psychol. 2005;19:404–419. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.3.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cuffe SP. McKeown RE. Addy CL. Garrison CZ. Family and psychosocial risk factors in a longitudinal study of adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44:L121–L129. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200502000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hamilton HA. Extended families and adolescent well-being. J Adolesc Health. 2005;36:260–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Garnefski N. Diekstra RF. Adolescents from one parent, stepparent and intact families: Emotional problems and suicide attempts. J Adolesc. 1997;20:201–208. doi: 10.1006/jado.1996.0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Patel V. Flisher AJ. Nikapota A. Malhotra S. Promoting child and adolescent mental health in low and middle income countries. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49:313–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lee SJ. Detels R. Rotheram-Borus MJ. Duan N. The effect of social support on mental and behavioral outcomes among adolescents with parents with HIV/AIDS. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:1820–1826. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.084871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lipman EL. Offord DR. Boyle MH. Relation between economic disadvantage and psychsocial morbidity in children. CMAJ. 1994;152:810–812. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dearing E. Psychological costs of growing up poor. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2008;1136:324–332. doi: 10.1196/annals.1425.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Duncan GJ. Brooks-Gunn J. Klebanov PK. Economic deprivation and early childhood development. Child Dev. 1994;65:296–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.McLoyd VC. Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. Am Psychol. 1998;53:185–204. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.McLeod JD. Shanahan MT. Trajectories of poverty and children's mental health. J Health Soc Behav. 1996;37:207–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Safren SA. Otto MW. Worth JL, et al. Two strategies to increase adherence to HIV antiretroviral medication: Life-Steps and medication monitoring. Behav Res Ther. 2001;39:1151–1162. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(00)00091-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Catz SL. Kelly JA. Bogart LM. Benotsch EG. McAuliffe TL. Patterns, correlates, and barriers to medication adherence among persons prescribed new treatments for HIV disease. Health Psychol. 2000;19:124–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Leserman J. Role of depression, stress, and trauma in HIV disease progression. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:539–545. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181777a5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Antelman G. Kaaya S. Wei R, et al. Depressive symptoms increase risk of HIV disease progression and mortality among women in Tanzania. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44:470–477. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31802f1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mayne TJ. Vittinghoff E. Chesney MA. Barrett DC. Coates TJ. Depressive affect and survival among gay and bisexual men infected with HIV. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:2233–2238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Irwin A. Adams A. Winter A, et al. Home truths: facing the facts on children, AIDS, and poverty [final report] Joint Learning Initiative on Children and HIV/AIDS (JLICA) 2009. www.jlica.org. [Jul 10;2009 ]. www.jlica.org

- 97.Richter L. Sherr L. Desmond C. An obvious truth: Children affected by HIV and AIDS are best cared for in functional families with basic income security, access to health care and education, and support from kin and community. [synthesis report] Joint Learning Initiative on Children and HIV/AIDS (JLICA) Learning Group 1: Strengthening Families. 2008. www.jlica.org. [Jul 11;2009 ]. www.jlica.org

- 98.Rotheram-Borus MJ. Lee M. Lin YY. Lester P. Six-year intervention outcomes for adolescent children of parents with the human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:742–748. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.8.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]