Abstract

Protein kinase C (PKC) regulates a variety of neural functions, including ion channel activity, neurotransmitter release, receptor desensitization and differentiation. We have shown previously that mice lacking the ε-isoform of PKC (PKCε) self-administer 75% less ethanol and exhibit supersensitivity to acute ethanol and allosteric positive modulators of GABAA receptors when compared with wild-type controls. The purpose of the present study was to examine involvement of PKCε in GABAA receptor regulation of voluntary ethanol drinking. To address this question, PKCε null-mutant and wild-type control mice were allowed to drink ethanol (10% v/v) vs. water on a two-bottle continuous access protocol. The effects of diazepam (nonselective GABAA BZ positive modulator), zolpidem (GABAA α1 agonist), L-655,708 (BZ-sensitive GABAA α5 inverse agonist), and flumazenil (BZ antagonist) were then tested on ethanol drinking. Ethanol intake (grams/kg/day) by wild-type mice decreased significantly after diazepam or zolpidem but increased after L-655,708 administration. Flumazenil antagonized diazepam-induced reductions in ethanol drinking in wild-type mice. However, ethanol intake by PKCε null mice was not altered by any of the GABAergic compounds even though effects were seen on water drinking in these mice. Increased acute sensitivity to ethanol and diazepam, which was previously reported, was confirmed in PKCε null mice. Thus, results of the present study show that PKCε null mice do not respond to doses of GABAA BZ receptor ligands that regulate ethanol drinking by wild-type control mice. This suggests that PKCε may be required for GABAA receptor regulation of chronic ethanol drinking.

Keywords: ethanol drinking, PKC, PKCε, GABA, GABAA, diazepam, zolpidem, L-655, 708, benzodiazepine

INTRODUCTION

Protein kinase C (PKC) is a family of serine–threo-nine kinases that is divided into three major subsets: conventional (α, βI, βII, and γ), novel (δ, ε, Z, and θ), and atypical (λ and ζ), based primarily on structural and functional properties of the kinase regulatory domain (Newton, 2003). In general, PKC regulates a variety of neural functions, including ion channel activity, neurotransmitter release, receptor desensitization and differentiation (Tanaka and Nishizuka, 1994). Evidence suggests that specific isoforms of PKC (PKCγ and PKCε) regulate the biochemical and behavioral effects of ethanol (Harris et al., 1995; Hodge et al., 1999). Mice lacking the PKCε isozyme show greater sensitivity to low and high doses of ethanol (Hodge et al., 1999). Consistent with increased acute sensitivity to ethanol, PKCε null-mutant mice have been shown to self-administer less ethanol than do wild-type controls under voluntary home-cage (Hodge et al., 1999) and operant self-administration (Olive et al., 2000) conditions. PKCε null mice also exhibit reduced relapse to ethanol self-administration (Olive et al., 2000). These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that increased acute sensitivity to ethanol is negatively correlated with ethanol consumption in animals (Blednov et al., 2003; Thiele et al., 1998) and alcoholism risk in humans (Schuckit, 1994).

Evidence also indicates that ethanol self-administration is regulated by GABAA receptor activity (Boyle et al., 1993; Shelton and Grant, 2001; Smith et al., 1992; Wegelius et al., 1994), and PKCε can influence GABAA-mediated actions of ethanol (Hodge et al., 1999). Accordingly, PKCε null-mutant mice show increased behavioral (motor activation and hypnosis) and biochemical (Cl− flux) sensitivity to allosteric positive modulation of GABAA receptors (Hodge et al., 1999), suggesting that PKCε regulates GABAA receptor function (Proctor et al., 2003). Consistent with these results from null mutant mice, PKCε is abundant in brain regions (Saito et al., 1993) where GABAA receptors are known to influence ethanol self-administration, such as the nucleus accumbens and amygdala (Hodge et al., 1995, 1996; Hyytia and Koob, 1995; Roberts et al., 1996). These data suggest that PKCε-regulated changes in GABAA receptor sensitivity may regulate ethanol self-administration.

Although it is not yet known which GABAA receptor subunit(s) are required for PKC modulation of ethanol-associated effects, PKCε has been shown to be colocalized with benzodiazepine (BZ)-sensitive GABAA receptors (i.e., α1 subunit containing) in the nucleus accumbens and amygdala (Olive and Hodge, 2000). BZ-sensitive GABAA receptors have been shown to modulate voluntary ethanol drinking (June et al., 1996; Schmitt et al., 2002). It is not known, however, whether ethanol drinking is modulated by interactions between PKCε and BZ-sensitive GABAA receptors.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine involvement of BZ-sensitive GABAA receptors in voluntary ethanol drinking by PKCε null-mutant and wild-type control mice. To accomplish this goal, mice were first exposed to ascending concentrations of ethanol (2–18% (v/v) vs. H2O) and then maintained at 10% ethanol (v/v) vs. H2O for the duration of the study. Then, the effects of the nonselective GABAA BZ positive modulator diazepam, the GABAA α1 agonist zolpidem, the BZ-sensitive GABAA α5 inverse agonist L-655,708, and the BZ antagonist flumazenil were tested on ethanol drinking. Finally, to confirm involvement of BZ-sensitive GABAA receptors in modulating ethanol drinking, animals were pretreated with the BZ antagonist flumazenil before diazepam administration and ethanol intake was measured. Given that these animals are bred on a different genetic background when compared with previous studies, we also sought to replicate previously reported differences in ethanol and diazepam acute sensitivity (i.e., Hodge et al., 1999).

METHODS

Animals

Male PKCε wild-type (PKCε+/+) and PKCε null-mutant mice (PKCε−/−) weighing between 25 and 35 g were used in the present study. PKCε null mice were first derived by homologous recombination in J1 embryonic stem cells (Khasar et al., 1999) and have now been backcrossed to each of the inbred mouse strains C57BL/6J and 129SvJae. PKCε heterozygous null mice from each strain were mated to produce male F1 hybrid null and wild-type controls for use in the present study. This breeding scheme is considered to be a rigorous control for genetic background of experimental animals and is in agreement with the recommendations of the Branbury Conference on Genetic Background in Mice (Silva et al., 1997). Mice were housed individually (drinking studies) or in groups of 3–4 (acute response studies) in standard Plexiglas cages with food and water available continuously. The colony room was maintained on a reverse 12-h light/dark cycle with lights off at 2200 hrs. All procedures were in accordance with the NIH Guide to Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and institutional guidelines.

Apparatus

Eight Plexiglas chambers (28 × 28 cm2; Med Associates) were used to measure locomotor activity. Each chamber was equipped with two sets of 16 pulse-modulated infrared photo beams (2.5 cm from the floor) placed on opposite walls to record x–y ambulatory movements. Activity chambers were computer interfaced (Med Associates) for data sampling at 100-ms resolution.

Procedures

Alcohol drinking and testing

Mice (PKCε+/+, n = 6; PKCε−/−, n = 5) were given access to two 50-ml plastic bottles equipped with ballbearing stoppers to limit spillage. Throughout the duration of the study, mice always had access to 2 bottles, one containing ethanol and the other water. The position of the bottles (left or right side) was alternated daily. Mice were weighed and the volumes were recorded daily ~30 min prior to the onset of the dark cycle. In order to investigate acquisition of ethanol drinking behavior in each group, mice were exposed to ascending ethanol concentrations (2, 4, 8, 10, 14, 18%, v/v) for 4 days at each concentration. After the ethanol dose–response curve was determined, mice were maintained at 10% ethanol (v/v) for the duration of the study.

In order to assess benzodiazepine (BZ)-sensitive GABAA modulation of ethanol drinking, the initial assessment involved administration of diazepam (0, 10 mg/kg, i.p.). Second, the effects of the BZ-sensitive GABAA α1 agonist zolpidem were tested (0, 10 mg/kg, i.p.). L-655,708 (0, 1 mg/kg, i.p.) was used to test the effects of the BZ-sensitive GABAA α5 inverse agonist, and flumazenil (0, 5 mg/kg, i.p.) was used to test the effects of a BZ-antagonist on ethanol drinking. Finally, the ability of flumazenil to antagonize the effects of diazepam on ethanol drinking was tested. Specifically, mice were pretreated with flumazenil (0, 5 mg/kg) 10 min before receiving diazepam (0, 10 mg/kg). For all the tests in this study (except when mentioned), the test compound was administered at the onset of the 24 h cycle with no more than two tests per week (Tuesdays and Thursdays). There was at least 1 week between testing of different compounds.

Ethanol-induced hypnosis

Mice (PKCε+/+, n = 4; PKCε−/−, n = 3) were injected with a sedative dose of ethanol (3.5 g/kg, i.p.) and intermittently placed on their backs in a v-shaped trough to test for the loss of righting reflex. Loss of righting was defined as the inability of an animal to right itself after being placed on its back within a 30-s interval. Recovery of the righting reflex was determined when the animal righted itself three times within 30 s. Duration was defined as the time interval between loss and recovery of the righting reflex.

Locomotor activity

To test the effects of ethanol (2 g/kg) and diazepam (1.5 mg/kg) on locomotor ability, mice were allowed 1 h to habituate to the activity chambers. After 1 h, mice were removed from the chamber and injected i.p. with ethanol or diazepam and immediately returned to the chamber. For the ethanol test (PKCε+/+, n = 12; PKCε−/−, n = 10), locomotor activity was monitored for 5 min based on preliminary data showing greatest ethanol-induced effect within the first 5 min, and for the diazepam test (PKCε+/+, n = 4; PKCε−/−, n = 3), locomotor activity was monitored for 1 h.

Drugs

For acute injection (ethanol sedation and locomotor assessment), ethanol (95%, w/v) was diluted in saline to a concentration of 20% (v/v) and administered i.p. in various volumes to obtain the appropriate dose (gram per kilogram). For alcohol drinking, ethanol (95%, w/v) was diluted in water to the desired concentration. Diazepam, flumazenil and zolpidem (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and their vehicles, 1, 0.5, and 0.5% carboxymethylcellulose, respectively, were injected i.p. at a volume of 10 ml/kg. L-655,708 (Tocris, Ellisville, MO) was diluted in a vehicle containing saline (80%) and DMSO (20%) vehicle and injected at a volume of 10 ml/kg.

Data analysis

Duration of the loss of righting reflex and the locomotor assessments were analyzed using t-tests. Two-bottle drinking data were analyzed using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with ethanol concentration or pretreatment drug dose as a repeated factor. Tukey’s post hoc tests were used to extract significant main effects and interactions. In the absence of a significant interaction, within genotype planned comparisons were used to follow-up a significant main effect of ethanol concentration/drug dose to determine whether drug treatment altered ethanol intake relative to vehicle injection.

RESULTS

Alcohol drinking

Exposure to ascending concentrations of ethanol was not accompanied by a significant difference in genotype, as both the PKCε null mutants and PKCε wild-type mice showed similar ethanol intake (g/kg; Table I). There was, however, a significant main effect of ethanol dose [F(5,45) = 39.56, P < 0.001]. In PKCε wild-type mice, greater ethanol intake was observed at all concentrations relative to 2% ethanol, Ps < 0.006; in PKCε null-mutant mice, greater ethanol intake was observed at all concentrations (except 8%) relative to 2%, Ps < 0.02. The genotype x ethanol concentration interaction was not significant. Ethanol intake is also expressed as milliliters consumed. As with the gram per kilogram analysis, there was a significant main effect of ethanol dose [F(5,45) = 3.37, P = 0.01], which was driven by a downward trend in milliliters consumed by the PKCε null-mutant mice and a significant decrease in the wild-type mice at the 14% ethanol concentration, P = 0.047. There was no significant difference in genotype and the genotype x ethanol concentration interaction was not significant. Water consumption was not altered by exposure to the ascending ethanol concentrations, and PKCε null-mutant and PKCε wild-type mice did not differ in overall water consumption (Table I).

TABLE I.

Ethanol (g/kg) and water intake (ml) at different ethanol concentrations

| Ethanol concentration (%, v/v) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 4 | 8 | 10 | 14 | 18 | ||

| Ethanol intake (g/kg) | |||||||

| PKCε+/+ | 2.12 ± 0.21 | 3.73 ± 0.18* | 6.70 ± 0.95* | 10.71 ± 1.60* | 9.35 ± 1.61* | 18.14 ± 2.53* | |

| PKCε−/− | 1.81 ± 0.21 | 3.66 ± 0.66* | 6.38 ± 1.92 | 7.88 ± 1.13* | 8.42 ± 0.75* | 14.15 ± 1.76* | |

| Ethanol intake (ml) | |||||||

| PKCε+/+ | 3.79 ± 0.33 | 3.42 ± 0.19 | 3.06 ± 0.45 | 3.90 ± 0.60 | 2.46 ± 0.44 | 3.08 ± 0.43 | |

| PKCε−/− | 3.30 ± 0.32 | 3.30 ± 0.52 | 2.90 ± 0.83 | 2.90 ± 0.38 | 2.25 ± 0.21 | 2.72 ± 0.22 | |

| Water intake (ml) | |||||||

| PKCε+/+ | 3.60 ± 0.35 | 3.77 ± 0.27 | 3.88 ± 0.61 | 2.67 ± 0.48 | 3.96 ± 0.58 | 4.38 ± 0.57 | |

| PKCε−/− | 4.03 ± 0.26 | 3.73 ± 0.29 | 3.68 ± 0.67 | 4.23 ± 0.74 | 4.40 ± 0.62 | 4.85 ± 0.65 | |

Values given are mean ± SEM.

PKCε+/+, n = 6; PKCε−/−, n = 5.

P < 0.05 relative to 2% within genotype.

Modulation of ethanol drinking by diazepam (10 mg/kg), zolpidem (10 mg/kg), flumazenil (5 mg/kg), and L-655,708 (1 mg/kg)

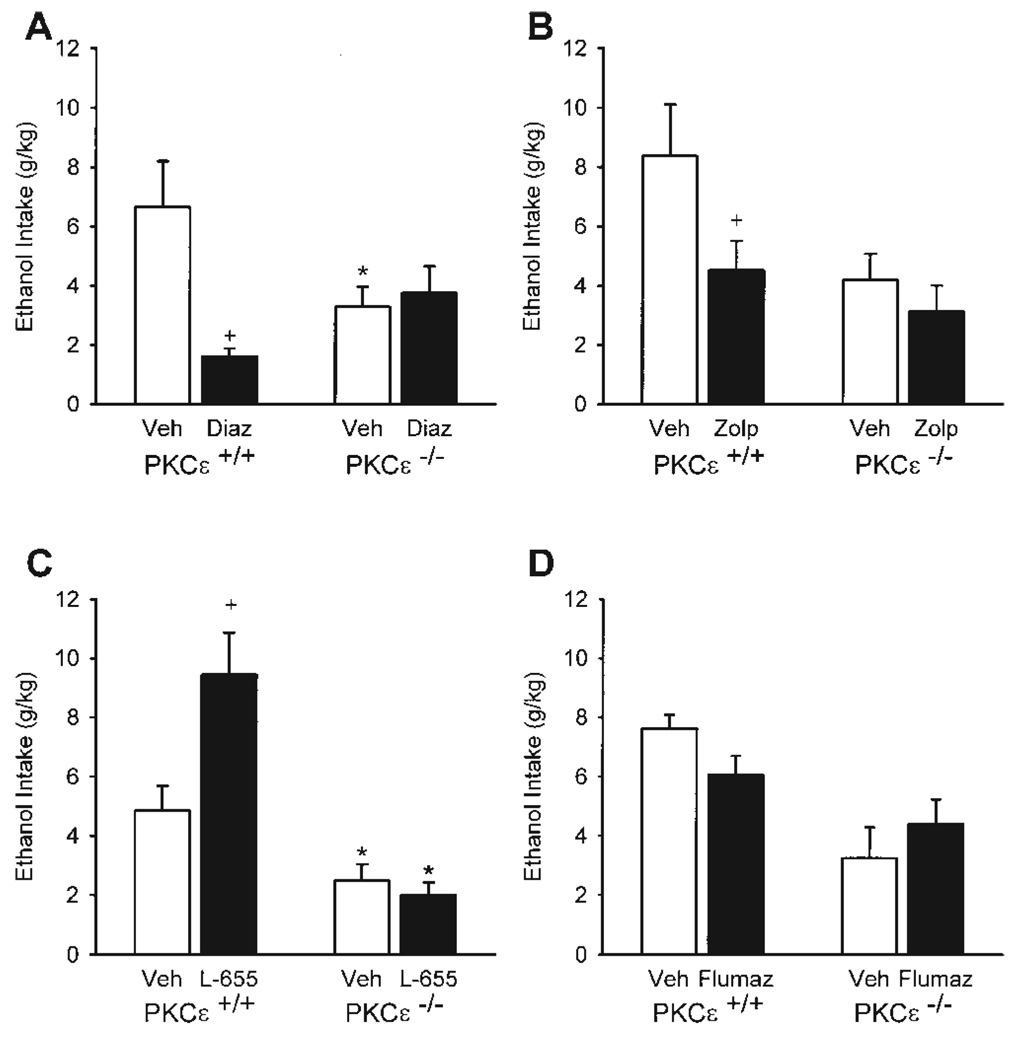

Diazepam selectively reduced ethanol intake (g/kg) as shown by a significant genotype x diazepam treatment interaction [F(1,9) = 6.86, P = 0.03; Fig. 1A]. Specifically, diazepam treatment significantly reduced ethanol intake in the PKCε wild-type mice, P = 0.006, with no effect of ethanol intake in the null-mutant mice. PKCε+/+ mice consumed significantly greater ethanol relative to the null-mutant mice, P = 0.03, after vehicle treatment; diazepam treatment eliminated this difference. The PKCε wild-type and null-mutant mice did not differ on water intake (Table II). However, diazepam (10 mg/kg) treatment increased water intake [F(1,9) = 7.93, P = 0.02; Table II], with greater water intake after diazepam treatment in the PKCε wild-type mice, P = 0.045. The genotype x diazepam treatment interaction was not significant. Overall, there was no change in total fluid consumption (ethanol + water, milliliters), which indicates that the diazepam-induced reduction in ethanol intake was accompanied by a compensatory increase in water intake.

Fig. 1.

Ethanol intake (±SEM; in gram per kilogram) by PKCε wild-type (+/+) and null-mutant (−/−) mice after administration of 10 mg diazepam/kg (Diaz, A), 10 mg zolpidem/kg (Zolp, B), 1 mg L-655,708/kg (L-655, C), and 5 mg flumazenil/kg (Flumaz, D). * Denotes significant difference between genotypes at the respective dose (Tukey, P < 0.05). + Denotes significant difference from vehicle within genotype. For all compounds, n = 6 and 5 for PKCε+/+ and PKCε−/− respectively, except for L-655,708, wherein n = 5 for both PKCε+/+ and PKCε−/−.

TABLE II.

Water intake for BZ-tests

| Water intake (ml) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Vehicle | Diazepam (10 mg/kg) | |

| PKCε+/+ (n = 6) | 3.67 ± 0.77 | 6.58 ± 0.40* |

| PKCε−/− (n = 5) | 4.70 ± 0.41 | 5.40 ± 0.58 |

| Vehicle | Zolpidem (10 mg/kg) | |

| PKCε+/+ (n = 6) | 4.00 ± 0.22 | 1.92 ± 0.30* |

| PKCε−/− (n = 5) | 3.80 ± 0.34 | 2.20 ± 0.54* |

| Vehicle | L-655,708 (1 mg/kg) | |

| PKCε+/+ (n = 5) | 4.90 ± 0.68 | 2.83 ± 0.60* |

| PKCε−/− (n = 5) | 5.30 ± 0.44 | 6.00 ± 0.35 |

| Vehicle | Flumazenil (5 mg/kg) | |

| PKCε+/+ (n = 6) | 3.58 ± 0.91 | 4.33 ± 0.68 |

| PKCε−/− (n = 5) | 3.10 ± 0.70 | 4.10 ± 0.51* |

Values given are mean ± SEM.

P < 0.05 relative to vehicle within genotype.

Zolpidem (10 mg/kg) treatment significantly reduced ethanol intake [F(1,9) = 7.10, P = 0.03; Fig. 1B], with a significant zolpidem-induced reduction in PKCε wild-type mice, P = 0.049. No change was observed in the PKCε null-mutant mice. There was no significant main effect of genotype or interaction. Zolpidem also significantly reduced water intake [F(1,9) = 56.36, P < 0.001; Table II] in both PKCε wild-type mice and null mutant mice, Ps < 0.03. Overall, zolpidem decreased total fluid consumption [ethanol + water, milliliters; F(1,9) = 54.99, P < 0.001], in both PKCε wild-type and null mutant mice, Ps = 0.002, which suggests a nonspecific effect on drinking behavior.

The effects of L-655,708 (1 mg/kg) treatment on ethanol intake are shown in Figure 1C. The ethanol and water intake data from one PKCε wild-type mouse are not included in this analysis because of a leak in the ethanol bottle. There was a significant main effect of genotype [F(1,9) = 24.14, P < 0.001], and a significant interaction [F(1,8) = 5.76, P = 0.04]. L-655,708 significantly increased ethanol intake in PKCε wild-type mice, P = 0.02, with no effect on ethanol intake in PKCε null-mutant mice. PKCε wild-type mice consumed significantly greater ethanol relative to the null-mutant mice, P = 0.04, after vehicle treatment and L-655,708 treatment, P < 0.001. Water intake was also altered by L-655,708 treatment (Table II). A significant main effect of genotype [F(1,9) = 8.80, P = 0.02] and a significant dose x genotype interaction [F(1,8) = 8.19, P = 0.02] were found. L-655,708 did not affect water intake in the PKCε null-mutant mice; however, a significant decrease was observed in the PKCε wild-type mice, P = 0.02, which likely represents a compensatory decrease in fluid intake, corresponding to the increase in ethanol intake. Water intake between the genotypes did not differ after vehicle injection; however, PKCε wild-type mice did show lower levels of water intake relative to the null-mutant mice after 1 mg L-655,708/kg, P < 0.001. Overall, there was no change in total fluid consumption (ethanol + water, milliliters), which indicates that the increase in ethanol intake produced by L-655,708 was accompanied by a compensatory decrease in water intake.

Flumazenil (5 mg/kg) treatment did not affect ethanol consumption (Fig. 1D). A significant main effect of genotype was observed [F(1,9) = 15.73, P = 0.003] with the PKCε wild-type mice exhibiting higher levels of ethanol intake than the null-mutant mice. The interaction was not significant. Flumazenil treatment significantly increased water intake (Table II), as evident by a significant main effect of drug treatment [F(1,9) = 7.61, P = 0.02], with an increase in water intake in the PKCε null-mutant mice, P = 0.03. Overall, there was no change in total fluid (ethanol + water, milliliters) consumed.

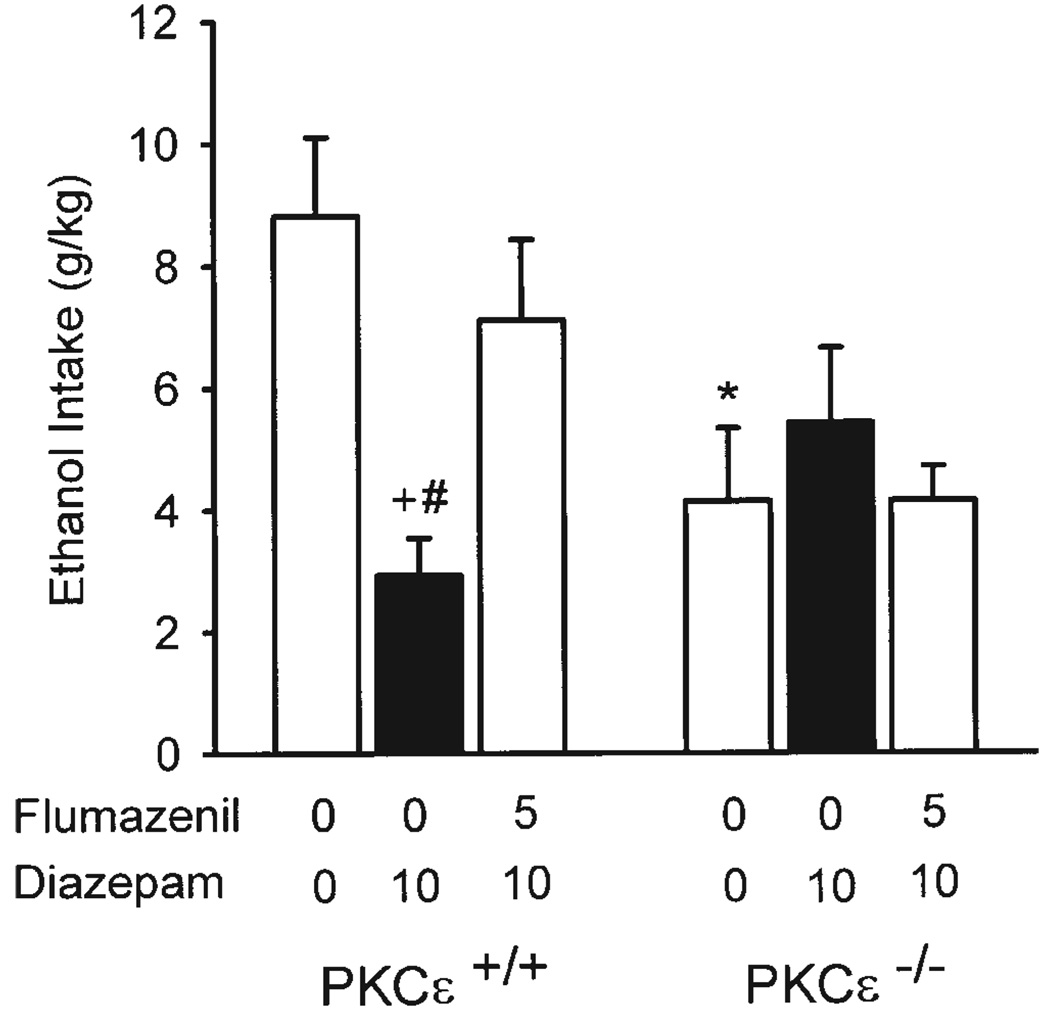

Flumazenil blockade of diazepam-induced drinking

Pretreatment with flumazenil (5 mg/kg) significantly altered the pattern of drinking induced by diazepam (10 mg/kg), as shown in Figure 2. A significant main effect of drug [F(2,18) = 3.98, P = 0.04] and a significant genotype x drug interaction [F(2,18) = 10.31, P = 0.001] were observed. In the PKCε wild-type mice, diazepam treatment significantly reduced ethanol intake, P < 0.001, as previously observed. Further, flumazenil pretreatment prevented the diazepam-induced reduction, as ethanol intake was similar to vehicle alone levels, and significantly greater than diazepam alone levels, P = 0.004. In the PKCε null-mutant mice, diazepam did not significantly alter ethanol intake, consistent with our previous findings (Fig. 1A), and flumazenil pretreatment had no effect on the pattern of diazepam-induced drinking. Further, with vehicle alone, ethanol intake was significantly greater in PKCε wild-type than in null-mutant mice, P = 0.007. This difference was prevented by diazepam treatment and flumazenil pretreatment. Water intake was not influenced by drug treatment or genotype (Table III). A significant interaction was observed [F(2,18) = 3.70, P = 0.045]; however, no significant differences were detected by the Tukey post hoc tests. Overall, flumazenil blocked the effects of diazepam on both ethanol and water intake, resulting in no change in total fluid (ethanol + water, milliliters) consumed.

Fig. 2.

Ethanol intake (±SEM; gram per kilogram) in PKCε wild-type (+/+; n = 6) and null-mutant (−/−; n = 5) mice after pre-treatment with flumazenil, followed by diazepam 10 min later. * Denotes significant difference between genotypes at the respective dose (Tukey, P < 0.05). + Denotes significant difference from vehicle (0 + 0) within genotype (Tukey, P < 0.05). # Denotes significant difference from 5 mg flumazenil/kg + 10 mg diazepam/kg treatment (Tukey, P < 0.05).

TABLE III.

Water intake for flumazenil modulation of diazepam-induced drinking

| Water intake (ml) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Veh + Veh | Veh + Diaz | Flu + Diaz | |

| PKCε+/+ (n = 6) | 3.08 ± 0.54 | 4.50 ± 0.37 | 3.75 ± 0.36 |

| PKCε−/− (n = 5) | 4.00 ± 0.91 | 2.90 ± 0.48 | 3.00 ± 1.19 |

Veh, vehicle; Diaz, 10 mg diazepam/kg; Flu, 5 mg flumazenil/kg.

Values given are mean ± SEM.

Ethanol sedation and locomotor activity

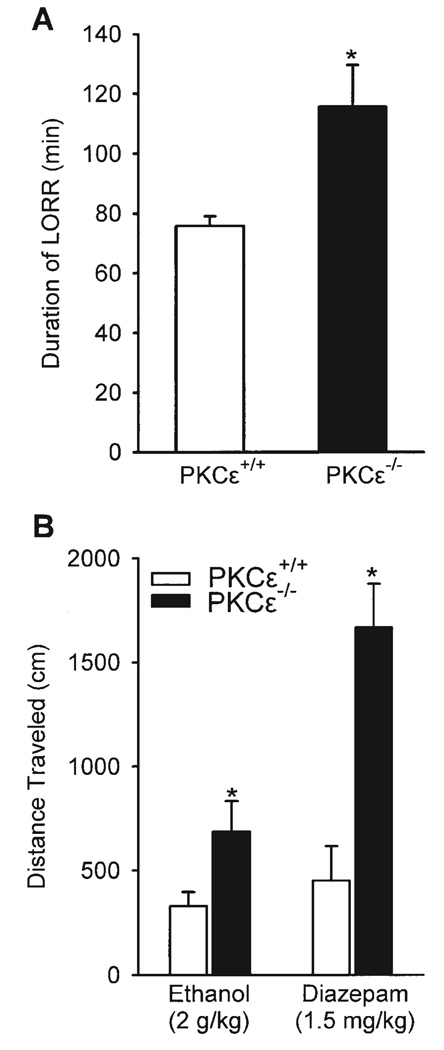

As shown in Figure 3A, ethanol (3.5 g/kg) significantly increased the duration of the loss of righting reflex in the PKCε null-mutant mice, P = 0.02. The tests of ethanol and diazepam-induced locomotor activity are illustrated in Figure 3B (left and right panel respectively). PKCε null-mutant mice showed greater locomotor response to an acute administration of ethanol (2 g/kg), P = 0.03, and to acute administration of diazepam (1.5 mg/kg), P = 0.006, than did PKCε wild-type mice. These findings confirm the results of previous work showing greater sensitivity to ethanol-induced sedation and acute administration of ethanol and diazepam in PKCε null-mutant mice (Hodge et al., 1999).

Fig. 3.

A. Duration (min) ±SEM of the loss of righting reflex induced by 3.5 g ethanol/kg in PKCε wild-type (+/+; n = 4) and null-mutant (−/−; n = 3) mice. B. Distance traveled (cm) ±SEM by PKCε wild-type (+/+) and null-mutant (−/−) mice during a 5-min ethanol test (2 g/kg, i.p.; PKCε+/+, n = 12; PKCε−/−, n = 10), and a 1-h diazepam test (1.5 mg/kg, i.p.; PKCε+/+, n = 4; PKCε−/−, n = 3). * Denotes significant difference (P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

The primary goal of this study was to examine potential interactions between PKCε and GABAA receptors in regulation of alcohol self-administration. Substantial evidence indicates that GABAA receptors modulate alcohol self-administration (Hodge et al., 1995, 1996; June et al., 2003; McKay et al., 2004; Rassnick et al., 1993; Roberts et al., 1996). Alcohol exposure and withdrawal produces adaptations in GABAA systems (Crews et al., 1996; Kumar et al., 2003; Morrow et al., 1988), which may increase subsequent alcohol self-administration behavior (Roberts et al., 1996) and function through a PKC mechanism (Kumar et al., 2002). Moreover, PKCε null mice are supersensitive to behavioral and biochemical effects of acute alcohol and GABAA positive modulators (Hodge et al., 1999). This supersensitivity is associated with reduced alcohol self-administration behavior and ethanol withdrawal seizure severity (Hodge et al., 1999; Olive et al., 2000, 2001). We have shown that PKCε is colocalized with BZ-sensitive GABAA α1 containing receptors in the nucleus accumbens (Olive and Hodge, 2000). This suggests that PKCε may modulate the GABAA-receptor-mediated properties of ethanol self-administration.

In the present work, ethanol consumption in PKCε null-mutant and wild-type mice did not differ during exposure to ascending ethanol concentrations (2–18%, (v/v) vs. H2O). However, a significant difference in ethanol intake emerged after completion of the ascending concentration curve with less ethanol (10%, v/v) consumption in PKCε null-mutant mice than in wild-type controls, which agrees with previously published results (Hodge et al., 1999). It is unclear why the PKCε null mutation did not influence ethanol intake during the initial phase of ethanol exposure (i.e., ascending concentrations), which is in contrast with published work showing decreased ethanol intake in PKCε null-mutant mice during exposure to a similar ethanol concentration curve (Hodge et al., 1999). One possible explanation for this inconsistency is that the mice used in previous work were F2–F4 hybrid C57BL/6J × 129 SvJae mice (from initial chimeras) (Khasar et al., 1999) whereas the mice used in the present study were F1 hybrid congenic C57BL/6J × 129 SvJae mice. This suggests that genetic background or Sv129 flanking genes (Crawley et al., 1997; Gerlai, 2001) may contribute to the apparent involvement of PKCε in regulation of initial ethanol intake. However, the previously reported phenotypic difference emerged and was maintained when mice were exposed to ethanol (10%, v/v) throughout the extended baseline and drug testing phases of the experiment. Thus, it appears that PKCε regulates the maintenance of voluntary ethanol drinking in a manner that may not depend on genetic background.

Results of the present study show that administration of the nonselective BZ positive modulator diazepam (10 mg/kg) or the GABAA α1 receptor agonist zolpidem (10 mg/kg) decreased voluntary ethanol intake in wild-type mice, but did not affect ethanol drinking in the PKCε null-mutant mice. Importantly, PKCε null mice showed significant changes in water drinking, indicating that drug doses were behaviorally active and that drinking patterns can be modulated by GABAergics in these mice. The diazepam-induced reduction of ethanol intake was completely blocked by pretreatment with the BZ antagonist flumazenil, confirming involvement of GABAA BZ receptors in wild-type mice. Previous work has found that treatment with BZs increases (Ingman et al., 2004; Soderpalm and Hansen, 1998; Wegelius et al., 1994) and decreases (Hedlund and Wahlstrom, 1998; Petry, 1995; Samson and Grant, 1985) ethanol intake. The effects of the compounds can vary by different factors such as BZ dose, self-administration protocol (i.e., continuous access, limited access—for a review, see Chester and Cunningham, 2002), and ethanol self-administration dose. The findings of the present work are consistent with diazepam (20 mg/kg)-induced decreases in ethanol intake using a continuous access two-bottle voluntary drinking procedure in rats (Hedlund and Wahl-strom, 1998). Flumazenil, the BZ receptor antagonist, has been shown to reverse reductions in drinking induced by GABAA/BZ partial inverse agonists (June et al., 1992; McBride et al., 1988); however, to our knowledge the effects of a BZ receptor antagonist on diazepam-induced reductions in ethanol intake have not been evaluated. Pretreatment with the GABAA α5 partial inverse agonist L-655,708 increased ethanol intake in the wild-type mice, but was without effect on ethanol consumption in the PKCε null-mutant mice. Although L-655,708 has not been previously tested in alcohol self-administration studies, this result is consistent with its anxiogenic effects (Navarro et al., 2002) and general association between anxiety and alcohol drinking (Pandey, 2003).

Overall, these results appear inconsistent with previously published results. That is, given that PKCε null-mutant mice show greater sensitivity to allosteric positive modulation of GABAA receptors (Hodge et al., 1999), one would predict greater sensitivity to the modulation of voluntary ethanol drinking by BZ-sensitive GABAA receptors. However, as discussed earlier, the BZ compounds tested were without effect on ethanol drinking in the PKCε null-mutant mice. To confirm previously reported differences in acute sensitivity to ethanol and diazepam, PKCε null-mutant mice were exposed to acute administration of ethanol and diazepam. Consistent with previous findings, PKCε null-mutant mice showed greater sensitivity to a hypnotic dose of ethanol (3.5 g/kg) as indicated by a significant increase in the duration of the loss of righting reflex relative to PKCε wild-type mice. Also consistent with previous work, PKCε null-mutant mice showed greater locomotor activity in response to 2 g ethanol/kg and 1.5 mg diazepam/kg (Hodge et al., 1999) than did PKCε wild-type mice. These data demonstrate that previously published phenotypes remain intact in these mice and that changes in GABAA or ethanol sensitivity do not account for the lack of response to GABAergic drugs by the PKCε null mice.

Thus, it is important to consider why PKCε null mice are more sensitive to the acute effects of ethanol and GABAA receptor positive modulators but show an apparent lack of sensitivity to modulation of ethanol self-administration by this receptor system. First, in this study mice chronically self-administered ethanol for an extended period, which may have induced adaptive changes in wild-type mice that were absent in PKCε mutants. For example, in vitro evidence shows that chronic ethanol increases the abundance of PKCε (Messing et al., 1991), which may decrease behavioral and biochemical sensitivity to ethanol and/or GABAA receptor compounds (Hodge et al., 1999, 2002). PKCε is colocalized with BZ-sensitive GABAA α1-containing receptors in a variety of limbic brain regions (Olive and Hodge, 2000) and chronic ethanol increases receptor binding of compounds that target this subtype of the GABAA receptor (Devaud et al., 1995; Mhatre et al., 1988). Thus, upregulation of PKCε by chronic ethanol could contribute to altered sensitivity to BZs or ethanol in wild-type mice, which would be absent in PKCε null-mutant mice. Second, since PKCε null mice show heightened GABAA receptor responses to acute ethanol (Hodge et al., 1999; Proctor et al., 2003), chronic ethanol might lead to a downregulation of GABAA receptor function or expression in the null mice, which could result in decreased sensitivity (e.g., tolerance) to ethanol or GABAergic compounds.

There are several issues related to the present study that merit discussion. First, the effects of the GABA-ergic compounds were tested using a repeated measures design, which has the potential to confound order of testing with individual drug effects. For example, chronic ethanol exposure or repeated drug testing may have altered response to the GABAergic compounds. However, the effects of diazepam were constant across two separate tests, indicating no change in response after repeated testing. Second, although acute ethanol (4 g/kg, i.p.) clearance does not differ between PKCε null-mutant and wild-type mice (4 g/kg, i.p.; Hodge et al., 1999), measurement of blood ethanol concentrations in the present work would have allowed us to determine whether PKCε regulates ethanol metabolism after chronic exposure. However, baseline ethanol intake remained stable throughout the experiment in both PKCε null mice and wild-type controls, suggesting that ethanol metabolism was not changed. Third, while acute response to ethanol and diazepam confirmed previously published phenotypes (e.g., Hodge et al., 1999), conducting the same tests after ethanol self-administration would have allowed a direct assessment of adaptive changes in ethanol or GABAergic sensitivity. More research is needed to address these issues and potential changes in PKCε regulation of GABAA receptor function induced by chronic ethanol self-administration.

In conclusion, results of this study show that PKCε null mice do not respond to doses of GABAA BZ receptor ligands that decrease (diazepam and zolpidem), or increase (L-655,708), ethanol drinking in wild-type mice. This lack of response by the PKCε null mice occurs in spite of increased sensitivity to acute ethanol and diazepam. These findings suggest that GABAA receptor regulation of ethanol self-administration requires PKCε.

Acknowledgments

Contract grant sponsor: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Contract grant numbers: AA014983, AA011605; Contract grant sponsor: Bowles Center for Alcohol Studies.

REFERENCES

- Blednov YA, Walker D, Alva H, Creech K, Findlay G, Harris RA. GABAA receptor α1 and β2 subunit null mutant mice: Behavioral responses to ethanol. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;305:854–863. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.049478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle AE, Segal R, Smith BR, Amit Z. Bidirectional effects of GABAergic agonists and antagonists on maintenance of voluntary ethanol intake in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1993;46:179–182. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(93)90338-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chester JA, Cunningham CL. GABA(A) receptor modulation of the rewarding and aversive effects of ethanol. Alcohol. 2002;26:131–143. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(02)00199-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawley JN, Belknap JK, Collins A, Crabbe JC, Frankel W, Henderson N, Hitzemann RJ, Maxson SC, Miner LL, Silva AJ, Wehner JM, Wynshaw-Boris A, Paylor R. Behavioral phenotypes of inbred mouse strains: Implications and recommendations for molecular studies. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1997;132:107–124. doi: 10.1007/s002130050327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews FT, Morrow AL, Criswell H, Breese G. Effects of ethanol on ion channels. Int Rev Neurobiol. 1996;39:283–367. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(08)60670-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devaud LL, Morrow AL, Criswell HE, Breese GR, Duncan GE. Regional differences in the effects of chronic ethanol administration on [3H]zolpidem binding in rat brain. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1995;19:910–914. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb00966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlai R. Gene targeting: Technical confounds and potential solutions in behavioral brain research. Behav Brain Res. 2001;125:13–21. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00282-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris RA, McQuilkin SJ, Paylor R, Abeliovich A, Tonegawa S, Wehner JM. Mutant mice lacking the γ-isoform of protein kinase C show decreased behavioral actions of ethanol and altered function of γ-aminobutyrate type A receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3658–3662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedlund L, Wahlstrom G. The effect of diazepam on voluntary ethanol intake in a rat model of alcoholism. Alcohol. 1998;33:207–219. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.alcalc.a008384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge CW, Chappelle AM, Samson HH. GABAergic transmission in the nucleus accumbens is involved in the termination of ethanol self-administration in rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1995;19:1486–1493. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge CW, Haraguchi M, Chappelle AM, Samson HH. Effects of ventral tegmental microinjections of the GABAA agonist muscimol on self-administration of ethanol and sucrose. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1996;53:971–977. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(95)02146-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge CW, Mehmert KK, Kelley SP, McMahon T, Haywood A, Olive MF, Wang D, Sanchez-Perez AM, Messing RO. Supersensitivity to allosteric GABA(A) receptor modulators and alcohol in mice lacking PKCepsilon. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:997–1002. doi: 10.1038/14795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge CW, Raber J, McMahon T, Walter H, Sanchez-Perez AM, Olive MF, Mehmert K, Morrow AL, Messing RO. Decreased anxiety-like behavior, reduced stress hormones, and neurosteroid supersensitivity in mice lacking protein kinase C ε. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1003–1010. doi: 10.1172/JCI15903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyytia P, Koob GF. GABAA receptor antagonism in the extended amygdala decreases ethanol self-administration in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;283:151–159. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00314-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingman K, Sallinen J, Honkanen A, Korpi ER. Comparison of deramciclane to benzodiazepine agonists in behavioural activity of mice and in alcohol drinking of alcohol-preferring rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004;77:847–854. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- June HL, Colker RE, Domangue KR, Perry LE, Hicks LH, June PL, Lewis MJ. Ethanol self-administration in deprived rats: Effects of Ro15-4513 alone, and in combination with flumazenil (Ro15-1788) Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1992;16:11–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1992.tb00628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- June HL, Greene TL, Murphy JM, Hite ML, Williams JA, Cason CR, Mellon-Burke J, Cox R, Duemler SE, Torres L, Lumeng L, Li TK. Effects of the benzodiazepine inverse agonist RO19-4603 alone and in combination with the benzodiazepine receptor antagonists flumazenil, ZK 93426 and CGS 8216, on ethanol intake in alcohol-preferring (P) rats. Brain Res. 1996;734:19–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- June HL, Foster KL, McKay PF, Seyoum R, Woods JE, Harvey SC, Eiler WJ, Grey C, Carroll MR, McCane S, Jones CM, Yin W, Mason D, Cummings R, Garcia M, Ma C, Sarma PV, Cook JM, Skolnick P. The reinforcing properties of alcohol are mediated by GABA(A1) receptors in the ventral pallidum. Neuropsy-chopharmacology. 2003;28:2124–2137. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khasar SG, Lin YH, Martin A, Dadgar J, McMahon T, Wang D, Hundle B, Aley KO, Isenberg W, McCarter G, Green PG, Hodge CW, Levine JD, Messing RO. A novel nociceptor signaling pathway revealed in protein kinase C ε mutant mice. Neuron. 1999;24:253–260. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80837-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Sieghart W, Morrow AL. Association of protein kinase C with GABA(A) receptors containing α1 and α4 subunits in the cerebral cortex: Selective effects of chronic ethanol consumption. J Neurochem. 2002;82:110–117. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Kralic JE, O’Buckley TK, Grobin AC, Morrow AL. Chronic ethanol consumption enhances internalization of α1 subunit-containing GABAA receptors in cerebral cortex. J Neurochem. 2003;86:700–708. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride WJ, Murphy JM, Lumeng L, Li TK. Effects of Ro 15–4513, fluoxetine and desipramine on the intake of ethanol, water and food by the alcohol-preferring (P) and -nonpreferring (NP) lines of rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1988;30:1045–1050. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(88)90137-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay PF, Foster KL, Mason D, Cummings R, Garcia M, Williams LS, Grey C, McCane S, He X, Cook JM, June HL. A high affinity ligand for GABAA-receptor containing α5 subunit antagonizes ethanol’s neurobehavioral effects in Long-Evans rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;172:455–462. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1671-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messing RO, Petersen PJ, Henrich CJ. Chronic ethanol exposure increases levels of protein kinase C δ and ε and protein kinase C-mediated phosphorylation in cultured neural cells. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:23428–23432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mhatre M, Mehta AK, Ticku MK. Chronic ethanol administration increases the binding of the benzodiazepine inverse agonist and alcohol antagonist [3H]RO15-4513 in rat brain. Eur J Pharmacol. 1988;153:141–145. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90599-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow AL, Suzdak PD, Karanian JW, Paul SM. Chronic ethanol administration alters γ-aminobutyric acid, pentobarbital and ethanol-mediated 36Cl-uptake in cerebral cortical synapto-neurosomes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1988;246:158–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro JF, Buron E, Martin-Lopez M. Anxiogenic-like activity of L-655,708, a selective ligand for the benzodiazepine site of GABA(A) receptors which contain the α-5 subunit, in the elevated plus-maze test. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2002;26:1389–1392. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(02)00305-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton AC. Regulation of the ABC kinases by phosphorylation: Protein kinase C as a paradigm. Biochem J. 2003;370(Part 2):361–371. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olive MF, Hodge CW. Co-localization of PKCε with various GABA(A) receptor subunits in the mouse limbic system. Neurore-port. 2000;11:683–687. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200003200-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olive MF, Mehmert KK, Messing RO, Hodge CW. Reduced operant ethanol self-administration and in vivo mesolimbic dopamine responses to ethanol in PKCε-deficient mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:4131–4140. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olive MF, Mehmert KK, Nannini MA, Camarini R, Messing RO, Hodge CW. Reduced ethanol withdrawal severity and altered withdrawal-induced c-fos expression in various brain regions of mice lacking protein kinase C-ε. Neuroscience. 2001;103:171–179. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00566-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey SC. Anxiety and alcohol abuse disorders: A common role for CREB and its target, the neuropeptide Y gene. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2003;24:456–460. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(03)00226-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM. Ro 15–4513 selectively attenuates ethanol, but not sucrose, reinforced responding in a concurrent access procedure; comparison to other drugs. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1995;121:192–203. doi: 10.1007/BF02245630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor WR, Poelchen W, Bowers BJ, Wehner JM, Messing RO, Dunwiddie TV. Ethanol differentially enhances hippocampal GABA A receptor-mediated responses in protein kinase C-γ (PKC-γ) and PKC-ε null mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;305:264–270. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.045450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rassnick S, D’Amico E, Riley E, Koob GF. GABA antagonist and benzodiazepine partial inverse agonist reduce motivated responding for ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1993;17:124–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb00736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AJ, Cole M, Koob GF. Intra-amygdala muscimol decreases operant ethanol self-administration in dependent rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20:1289–1298. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito N, Itouji A, Totani Y, Osawa I, Koide H, Fujisawa N, Ogita K, Tanaka C. Cellular and intracellular localization of ε-sub-species of protein kinase C in the rat brain; presynaptic localization of the epsilon-subspecies. Brain Res. 1993;607:241–248. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91512-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson HH, Grant KA. Chlordiazepoxide effects on ethanol self-administration: Dependence on concurrent conditions. J Exp Anal Behav. 1985;43:353–364. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1985.43-353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt U, Waldhofer S, Weigelt T, Hiemke C. Free-choice ethanol consumption under the influence of GABAergic drugs in rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:457–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA. Low level of response to alcohol as a predictor of future alcoholism. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:184–189. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton KL, Grant KA. Effects of naltrexone and Ro 15–4513 on a multiple schedule of ethanol and Tang self-administration. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:1576–1585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva AJ, Simpson EM, Takahashi JS, Lipp H-P, Nakanishi S, Wehner JM, Giese KP, Tully T, Abel T, Chapman PF, Fox K, Grant S, Itohara S, Lathe R, Mayford M, McNamara JO, Morris RJ, Picciotto M, Roder J, Shin H-S, Slesinger PA, Storm DR, Stryker MP, Tone-gawa S, Wang Y, Wolfer DP. Mutant mice and neuroscience: Recommendations concerning genetic background. Neuron. 1997;19:755. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80958-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BR, Robidoux J, Amit Z. GABAergic involvement in the acquisition of voluntary ethanol intake in laboratory rats. Alcohol. 1992;27:227–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderpalm AH, Hansen S. Benzodiazepines enhance the consumption and palatability of alcohol in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1998;137:215–222. doi: 10.1007/s002130050613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka C, Nishizuka Y. The protein kinase C family for neuronal signaling. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1994;17:551–567. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.17.030194.003003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiele TE, Marsh DJ, Ste Marie L, Bernstein IL, Palmiter RD. Ethanol consumption and resistance are inversely related to neuropeptide Y levels. Nature. 1998;396:366–369. doi: 10.1038/24614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegelius K, Honkanen A, Korpi ER. Benzodiazepine receptor ligands modulate ethanol drinking in alcohol-preferring rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 1994;263:141–147. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90534-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]