Abstract

The number of neurons in the ventrobasal thalamus (VB) in the adolescent rat is unaffected by prenatal exposure to ethanol. This is in sharp contrast to other parts of the trigeminal-somatosensory system which exhibit 30–35% fewer neurons after prenatal ethanol exposure. The present study tested the hypothesis that prenatal ethanol exposure affects dynamic changes in the numbers of VB neurons; such changes reflect the sum of cell proliferation and death. Neuronal number in the VB was determined during the first postnatal month in the offspring of pregnant Long-Evans rats fed an ethanol-containing diet or pair-fed an isocaloric non-alcoholic liquid diet. Offspring were examined between postnatal day (P) 1 and P30. The size of the VB and neuronal number were determined stereologically. Prenatal exposure to ethanol did not significantly alter neuronal number on any individual day, nor was the prenatal generation of VB neurons affected. Interestingly, prenatal ethanol exposure did affect the pattern of the change in neuronal number over time; total neuronal number was stable in the ethanol-treated pups after P12, but it continued to rise in the controls until P21. In addition, the rate of cell proliferation during the postnatal period was greater in ethanol-treated animals. Thus, the rate of neuronal acquisition is altered by ethanol, and by deduction there appears to be less ethanol-induced neuronal loss in the VB. A contributor to these changes is a latent effect of ethanol on postnatal neurogenesis in the VB and the apparent survival of new neurons.

Keywords: alcohol, brain development, fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, fetal alcohol syndrome, neural stem cell, proliferation, somatosensory, trigeminal, ventrobasal

INTRODUCTION

The final number of neurons in a structure depends upon the numbers of neurons in interconnected structures (Herrup et al., 1996). Such system matching occurs even in the presence of genetic alterations, e.g., lurcher or staggerer (Herrup and Sunter, 1987; Vogel et al., 1989). Alternatively, pathological states including neonatal transection of the infraorbital nerve (a major component of the trigeminal nerve) can result in the matched loss of first order neurons in the trigeminal ganglion (Savy et al., 1981; Klein et al., 1988), second order neurons in the principal sensory nucleus of the trigeminal nerve (PSN; Waite, 1984; Miller et al., 1991), and third order neurons in the ventrobasal thalamus (VB; Waite et al., 1992; Baldi et al., 2000). The changes are proportional at each level of the neuraxis such that relationships between the areas are maintained.

Gestational ethanol exposure is a leading cause of mental dysfunction, e.g., hyperactivity and learning/memory deficits. Ethanol-induced developmental toxicity affects 1–2% of live births (CDC, 2006). Ethanol can cause (1) permanent reductions in neuronal number, (2) formation of aberrant connections by surviving neurons, and (3) depression of brain metabolism (Pentney and Miller, 1992; Miller, 2006).

Mechanisms underlying system matching apparently fail in animals exposed prenatally to ethanol. In the somatosensory system of 30-day-old rats prenatally exposed to ethanol, the PSN and cortex have 30–35% fewer neurons (Miller and Muller, 1989; Miller and Potempa, 1990; Miller, 1995a; 1999). The number of VB neurons on postnatal day (P) 30, however, is unaffected by prenatal exposure to ethanol (Mooney and Miller, 1999). Conceivably, ethanol does not affect the VB. Alternatively, it may disrupt the additive processes of neuronal production and/or migration and the subtractive process of neuronal death. The VB has the peculiar property of having in situ postnatal neuronal production (Mooney and Miller, 2007). Thus, a third mechanism for ethanol-induced changes in neuronal number may come from a correction by modifying the amount of this postnatal neuronal production.

The present study examines whether ethanol affects the generation of VB neurons. Given that prenatal exposure to ethanol has no effect on the total number of VB neurons on P30, we hypothesize that ethanol affects additive and subtractive processes in an equivalent manner or has no effect on either.

METHODS

Animals

Pregnant Long-Evans rats were obtained from Harlan (Indianapolis IN) on gestational day (G) 4. Animals were housed singly in a temperature/humidity controlled Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) accredited facility in which the light/dark cycle was 12 hours/12 hours. All procedures were approved by the Committee for the Humane Use of Animals at SUNY Upstate Medical University or the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Veteran’s Affairs Medical Center in Iowa City, IA or Syracuse, NY.

Rats were paired based on body weight. One rat from each pair was arbitrarily assigned to each of two treatment groups. One group was fed an ethanol-containing liquid diet (6.7% v/v ethanol; Et) ad libitum from G11 through G21. Animals were weaned onto the ethanol-containing diet between G6 and G10 by feeding them diets with increasing concentrations of ethanol (e.g., Mooney and Miller, 1999; 2001). The second group was pair-fed an isocaloric, isonutritive, non-alcoholic liquid diet (Ct). Based on the findings from a previous study (Miller, 1992), rats were presented with fresh diet at the end of the light cycle. This served to synchronize the feeding pattern for the Et- and Ct-fed rats. Rats fed using the paradigm described above have mean peak blood ethanol concentrations of ~150 mg/dl 2–4 hr after the beginning of the dark cycle (Miller, 1987; 1992). All procedures were the same as in previous studies of the trigeminal-somatosensory system (Miller and Muller, 1989; Miller and Potempa, 1990; Mooney and Miller, 1999).

At birth, all litters were culled to ten and surrogate-fostered by rats fed chow and water ad libitum during their pregnancies. Pups were included in the study without regard to their sex because there is no evidence of sexual dimorphism in the VB. Brains were harvested from the offspring on P1 (within 24 hours of birth), P3, P6, P12, and P21. Data on 30-day-old rats from a previous study (Mooney and Miller, 1999) have been presented with the results for comparisons with the new data. In the previous study, animals were collected on P30, processed, and analyzed using the same procedures as used in the present study. Thus, the full age range includes the periods of postnatal neurogenesis (Mooney and Miller, 2007) and naturally occurring neuronal death in the rat VB (Waite et al., 1992).

Anatomical analyses

One animal per each litter at each time-point was anesthetized (100 mg/kg ketamine and 10 mg/kg xylazine), transcardially perfused with 4.0% paraformaldehyde in 0.10 M phosphate buffer (PB). The brain was removed, post-fixed in fresh fixative, and cryoprotected in 30% sucrose in PB. Coronal cryosections of the forebrain (10 µm thick) were collected and stained with cresyl violet for counting neurons. A second set was stained to localize acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity for delineation of the boundaries of the VB (Kristt, 1983; Mooney and Miller, 1999). Another set of sections was immunolabeled for the expression of the neuron-specific marker NeuN.

Acetylcholinesterase histochemistry

Tissue was processed for AChE activity (Koelle and Friedenwald, 1949; El-Badawi and Schenk, 1967; Mooney and Miller, 1999) by incubating sections in a solution containing 0.50% acetylthiocholine iodide, the substrate for acetylcholine, 5.0 mM ferricyanide, 30.0 mM copper sulfate, 0.10 mM sodium citrate, and 0.10 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.5) for 3 hr at 37°C. Subsequently, sections were dehydrated through graded alcohols, cleared in xylene, and coverslipped.

[3H]thymidine and BrdU labeling

Four pregnant dams from each treatment group were injected with [3H]thymidine ([3H]dT) on one day during the period between G13 and G17 inclusive. [3H]dT was used for the studies of prenatal neuronal generation because it allows for the discrimination of first and later generation of neurons. One pup from each litter was euthanized on P21 by transcardial perfusion as described above. Thus, a total of 40 pups (4 pups × 5 timepoints × 2 treatment groups) were used in this analysis. Brains were removed, embedded in paraffin, cut into 10 µm thick sections, and prepared for autoradiographic analyses. Slides were coated with Nuclear Track Emulsion (NTB-2; Kodak, Rochester NY). The emulsion was exposed for 25–28 days, developed in Kodak D-19, and cleared in Kodak Rapid Fixer. Sections were stained with cresyl violet and coverslipped.

For studies of postnatal neurogenesis, the thymidine analog of choice was bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU). This label was well suited to the studies of cell cycle kinetics that were performed (Nowakowski et al., 1989; Mooney and Miller, 2007). On P6, three pups from each of three Et- and three Ct-treated litters were injected with BrdU (25 mg/kg; Sigma, St. Louis MO) at time 0. One animal from each litter was euthanized by transcardial perfusion 30 min later. The remaining two animals per litter were injected with BrdU (as above) 2 hr after the first injection. One animal from each litter was euthanized by transcardial perfusion 30 min later. The remaining animal from each litter received a third injection of BrdU (as above) 4 hr after the first injection and was euthanized by transcardial perfusion 30 min later. Thus, one animal per litter was collected at each of the following times; 0.5, 2.5, or 4.5 hr. A total of 18 pups (3 litters × 3 timepoints × 2 treatment groups) were used in the BrdU-labeling study. In addition to P6 (i.e., in pups used in the BrdU study), Ki-67 expression was determined in one sibling from each of the litters at four other ages, on P9, P12, P15, and P18. BrdU- and Ki-67-positive cells were detected immunohistochemically (Miller and Nowakowski, 1988; Siegenthaler and Miller, 2005; Mooney and Miller, 2007).

Immunohistochemistry

All steps were performed at room temperature unless otherwise noted. Non-specific antibody binding was blocked by incubating in a solution of PB containing 0.10% Triton X100 (TPB), 4.0% goat serum, and 1.0% bovine serum albumin.

Sections were incubated in primary antibodies directed against NeuN (1:50; MAB 377; Chemicon, Temecula CA), p75 (1:200; G3231 Promega, Madison WI), BrdU (1:50; 347580 BD Biosciences, San Jose CA), or Ki-67 (1:30; RM9106-50 Lab Vision, Fremont CA) for 1.5 hr. Sections were rinsed in PB, incubated in biotinylated secondary antibody (1:200; Vector, Burlingame CA) for 1.5 hr, rinsed again in PB, and incubated in streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (Vectastain Elite kit; Vector). Immunolabeling appeared brown after incubation with the chromagen 3,3'-diaminobenzidine (DAB; Vector) in the presence of hydrogen peroxide, or purple after use of alkaline phosphatase (Vector) as the chromagen. Sections were counterstained with cresyl violet or methyl green, dehydrated through graded alcohols, cleared in xylene, and coverslipped. Non-specific labeling was determined by omitting either the primary or the secondary antibody. Specificity of antibodies was determined as follows. Following labeling with NeuN, no neurons were unlabeled as determined by morphology. The pattern of labeling for p75 was as described by others (Crockett et al., 2000). BrdU immunopositive cells were not seen in animals not exposed to BrdU. Further, 30 min after exposure to BrdU (at which time most cells would still be in S-phase) all BrdU-positive cells co-localized Ki67.

For BrdU immunohistochemistry, DNA was denatured by heating sections in 0.010 M citrate buffer (pH 6.0). Subsequent steps were the same as those described above beginning with blocking.

Counting methods

Stereology

The VB and its subnuclei were discriminated based on differences in labeling intensity in the AChE-stained and p75-immunolabeled sections (Paxinos and Watson, 1982; Kristt, 1983; Mooney and Miller, 1999; 2007; Crockett et al., 2000). The two subnuclei of the VB, the medial and lateral compartments of the ventral posterolateral nucleus (the VPm and VPl, respectively), were characterized by differences in AChE-staining and p75-immunolabeling. AChE was highly expressed in the VPl during the first postnatal week. It then waned over time and was absent by P21. In contrast, p75 was highly expressed in the VPm just after birth, diminished over the first postnatal week, and was virtually absent by the second postnatal week. Thus, the pattern of AChE activity and p75 immunoreactivity were spatially complementary and temporally coincident. The total number of neurons in the VB was calculated as the product of the neuronal packing density and the volume of the VB. A stereological method (Smolen et al., 1983) was used to estimate neuronal packing density. An independent assessment of the VB volume was obtained using 3-dimensional reconstructions and Cavelieri’s estimator of volume (Miller and Muller, 1989; Miller and Potempa, 1990; Mooney and Miller, 1999; 2007). Neuronal packing density was generated from cresyl violet-labeled tissue. Identification of neurons was based on morphological criteria (e.g., size of the nucleus, size of the cell body, amount of cytoplasm visible, and the appearance of the nucleus). That said, a subset of sections was labeled with NeuN to specifically identify neurons. The density of NeuN-positive neurons was similar to that of cresyl violet-labeled neurons. Volume, cell packing density, and total neuron number were also determined separately for the two subnuclei at three ages, P6, P12, and P21.

Assays of cell proliferation

Studies of prenatal neuronal generation relied on [3H]dT autoradiography. [3H]dT-positive neurons were identified as being heavily- or lightly-labeled (Angevine, 1965; Nowakowski and Rakic, 1981; Miller, 1988). This discrimination was based on the relative number of grains overlying their nuclei. Heavily-labeled cells had at least half the number of grains over their nuclei as that detected over the maximally labeled neurons. These neurons were presumed to have been in their final mitosis when the [3H]dT was injected. Lightly-labeled neurons had less than half the maximal number but more than background numbers of grains over their nuclei (background was three grains). These neurons were presumed (a) to have undergone more than one mitotic division subsequent to the [3H]dT injection or (b) to be too deep in the section to be detected as heavily-labeled.

Insight into the dynamics of postnatal cell proliferation was gleaned from analyses of sections immunostained for Ki-67 and BrdU. The proportions of Ki-67- or BrdU-positive cells (labeling indices) were calculated as the number of labeled cells divided by the total number of labeled and unlabeled cells. The Ki-67 labeling index indicated the proportion of the population that was actively cycling, the growth fraction (GF). The lengths of the total cell cycle (TC) and the S phase of the cell cycle (TS) were calculated using the formulae described by Nowakowski and colleagues (Nowakowski et al., 1989; Mooney and Miller, 2007).

Statistical analyses

Quantitative data were analyzed using a one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) factoring in age and treatment condition. Where a significant difference was detected (p<0.05), post-hoc Tukey B-tests were performed.

RESULTS

Appearance of the VB during development

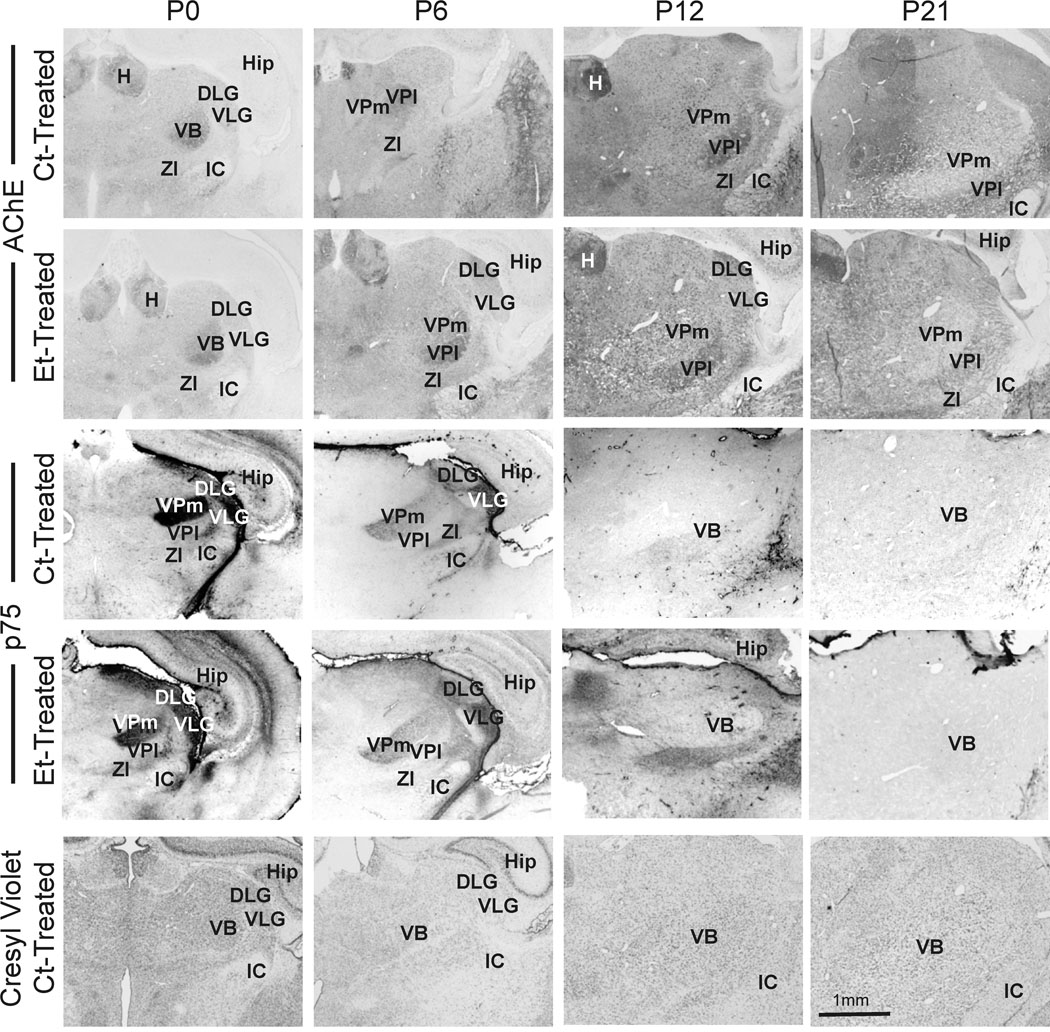

The VB was identifiable in cresyl violet-stained sections through the first postnatal month (Fig. 1). The VB can be structurally and functionally subdivided into two subnuclei; the ventral posterior medial (VPm) and ventral posterior lateral (VPl) nuclei. The VPm and VPl receive input from the face (and is part of the barrel system) and from the rest of the body, respectively (Jones, 2007).. The subnuclei were difficult to distinguish in the cresyl violet-stained sections during the first postnatal week. By the second week, however, the two subnuclei were distinguishable because the cross-sectional area of somata in the VPm was ~30% larger than those in the VPl.

Figure 1. Appearance of the VB.

The VB exhibited distinctive patterns of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity. AChE was highly expressed in the lateral ventral posterior nucleus (VPl) during the first postnatal week. In addition, p75 showed a time-dependent pattern of expression. It was highly expressed in the medial portion of the VB (VPm) during the first postnatal week. Both AChE activity and p75 immunoreactivity waned during the second postnatal week and were virtually absent by P21. The cytoarchitecture was also apparent in the cresyl violet-stained sections that were used for the stereological analysis. There were no notable effects of prenatal exposure to ethanol. DLG, dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus; H, habenula; Hip, hippocampus; IC, internal capsule; VLG, ventral lateral geniculate nucleus; ZI, zona incerta. Scale bar is 1 mm.

In addition to the subtle changes in the appearance of cresyl violet-stained tissue, the VB also exhibited dynamic patterns of AChE activity and p75 expression. AChE activity was more intense in the VB of neonates compared with surrounding thalamic nuclei. The VPl had more AChE activity than the VPm. By P12, the VPm had lost AChE staining intensity, and by P21 both subnuclei were paler than adjacent thalamic nuclei. The pattern of neurotrophin receptor expression contrasted with that of AChE staining. p75 immunolabeling was also temporally defined, and exhibited a pattern opposite to that seen with AChE staining. That is, it was highly expressed in the VPm of the neonate. Like AChE staining, p75 expression waned over time and was undetectable by P21.

Prenatal exposure to ethanol did not have a qualitative effect on the appearance of the VB and its subnuclei. This included the spatial and temporal expression of AChE activity and p75.

Numbers of neurons in the developing VB

Overall

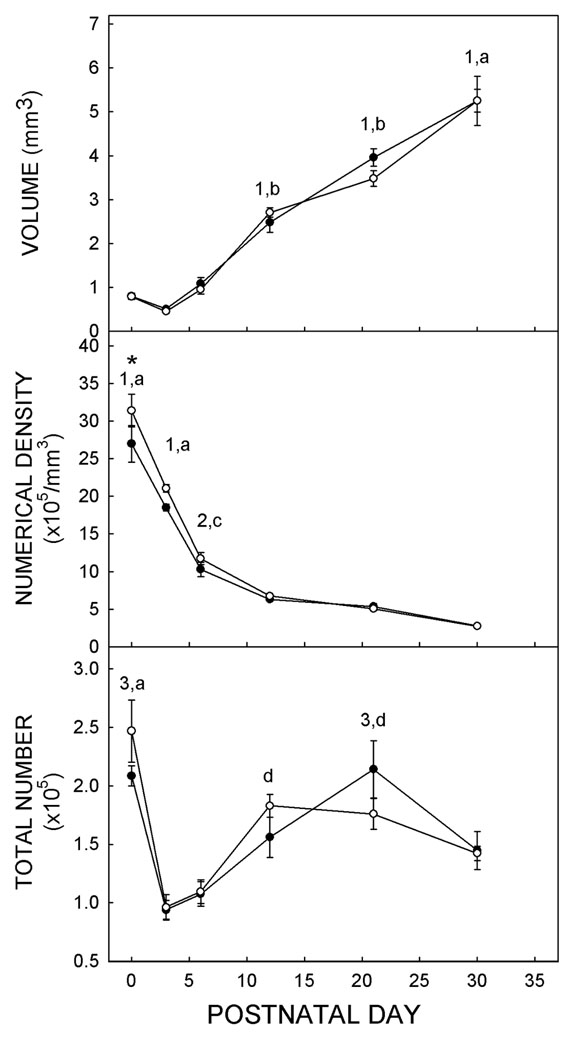

The volume of the VB increased steadily and significantly (F4,44 = 136.68; p<0.01) over the first postnatal month (Fig. 2; Supplementary Table I). Concomitantly, cell packing density of neurons in the VB fell (F4,44 = 166.19; p<0.01) over the same period. Overall, density was significantly (p<0.050 higher in Et-treated animals than in Ct-treated animals. Data for volume and density were combined to determine the neuronal number. A two-way ANOVA showed that there was a significant effect of age on neuronal number (F4,47 = 20.85; p<0.01).

Figure 2. Measurements of the VB.

Rats were exposed to ethanol prenatally and euthanized on postnatal (P) 0, P3, P6, P12, P24, or P30. The volume (top), the neuronal packing density (middle), and the total number of neurons (bottom) in the VB were quantified. Each point (solid circles identify data for controls; open circles signify data for ethanol-treated rats) represents the means of five rats, each rat being from a different litter. T-bars show standard errors of the means. * denotes significant difference between Ct- and Et-treated groups. Numbers describe significance (p<0.05) within Ct-treatment group, letters are used for Et-treated animals. 1, different to all other ages; 2, different to P21 and P30; 3, different to P3, P6, and P30. a, different to all other ages; b, different to P0, P3, P6, and P30; c, different to P12, P21, and P30; d, different to P3 and P6.

A treatment-induced difference in the temporal change in the number of neurons in the VB emerged when the data for each treatment group were assessed with a one-way ANOVA (F4,22 = 4.789; p<0.01). The total number of neurons in the VB of Ct-treated animals declined significantly (p<0.05) between P1 and P3. The number of neurons rose significantly (p<0.05) between P3 and P12 and continued to rise until P21. Neuronal number then fell significantly (p<0.05) between P21 and P30. This pattern was virtually identical to that described in the offspring of rats fed chow and water ad libitum during gestation (Mooney and Miller, 2007).

Though neuronal number rose in Et-treated animals, the timing of the changes differed from those detected in controls. As in the controls, the number of neurons declined significantly (p<0.05) between P1 and P3 and rose significantly (p<0.05) between P3 and P12. The number of VB neurons in Et-treated rats peaked on P12. After P12, there were no significant changes in neuronal number. Thus, ethanol exposure induced an acceleration in the acquisition of VB neurons and an earlier attainment of the maximal neuronal number. One result of this was a trend (p=0.083) towards a difference between Ct- and Et-treated animals in neuronal number on P21.

Subnuclei of the VB

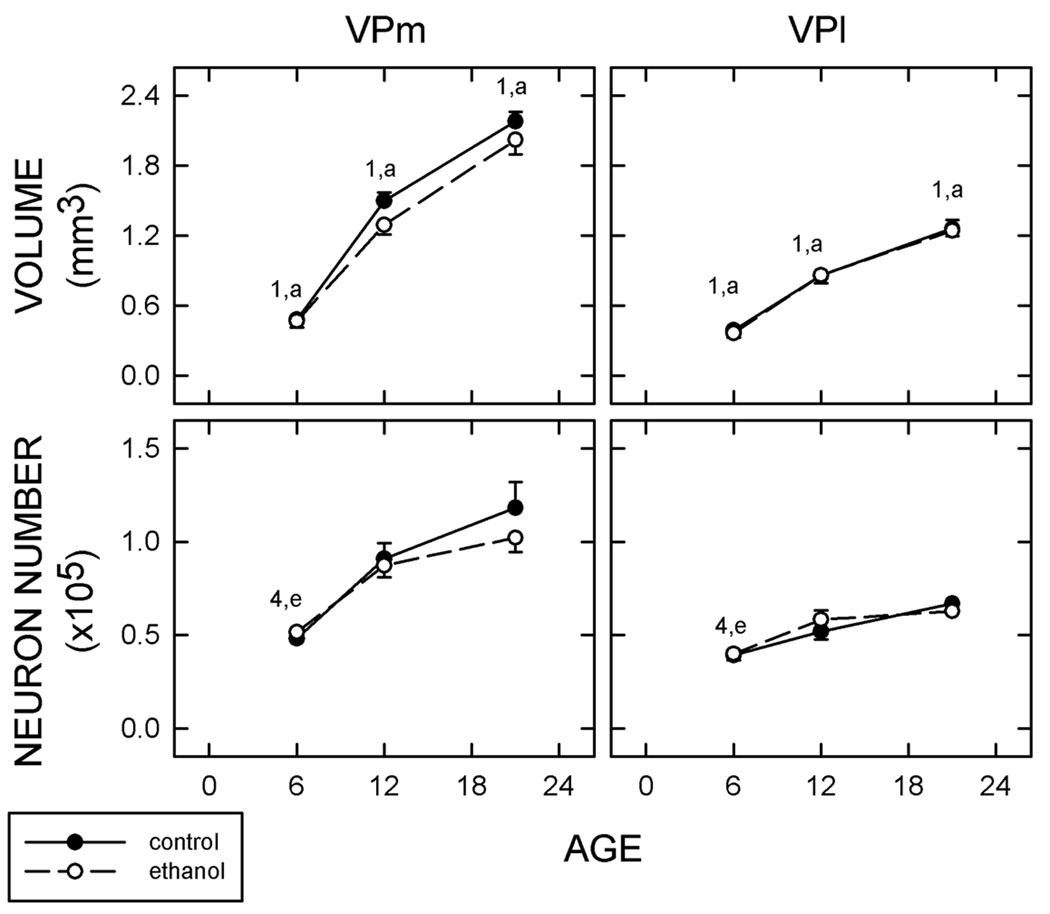

The volume, the neuronal packing density, and neuronal number for the subnuclei of the VB in control rats was determined at three ages; P6, P12, and P21 (Fig. 3; Supplementary Table II and Supplementary Table III). The volume of the VPm and VPl changed significantly with increased age (VPm F2,14 = 160.9; VPl F2,14 = 75.82; both p<0.01). The VPm was 55–62% of the VB during the first three postnatal weeks. The neuronal packing density was the same in both subnuclei (see above). By combining the above data, it was evident that the total neuronal number in both subnuclei of Ct-treated rats increased with age (VPm F2,14 = 14.152; VPl F2,14 = 13.62, p<0.01 for both).

Figure 3. Measurements of VB subnuclei.

The volume (top) and total number of neurons (bottom) were determined for the medial and lateral subnuclei of the ventral posterior nucleus, the entral posterior medial nucleus (VPm; left) and ventral posterior lateral nucleus (VPl; right), respectively. Estimates were made for 6-, 12, and 21-day-old pups (controls, solid circles and lines; ethanol-treated rats, open circles and dashed lines). Numbers describe significance (p<0.05) within Ct-treatment group, letters are used for Et-treated animals. 1, different to all other ages; 4, different to P12 and P21. a, different to all other ages; e, different to P12 and P21. n = 5.

Animals exposed to ethanol also showed an increased volume of both subnuclei (VPm F2,14 = 83.57; VPl F2,14 = 169.6, both p<0.01). There was a similar increase in neuronal number in each subnucleus with age (VPm F2,14 = 17.85, VPl F2,14 = 9.987, both p<0.01). Prenatal exposure to ethanol did not significantly affect the volume, the neuronal packing density, or neuronal number of the subnuclei at any age examined.

Generation of VB neurons

Prenatally generated neurons

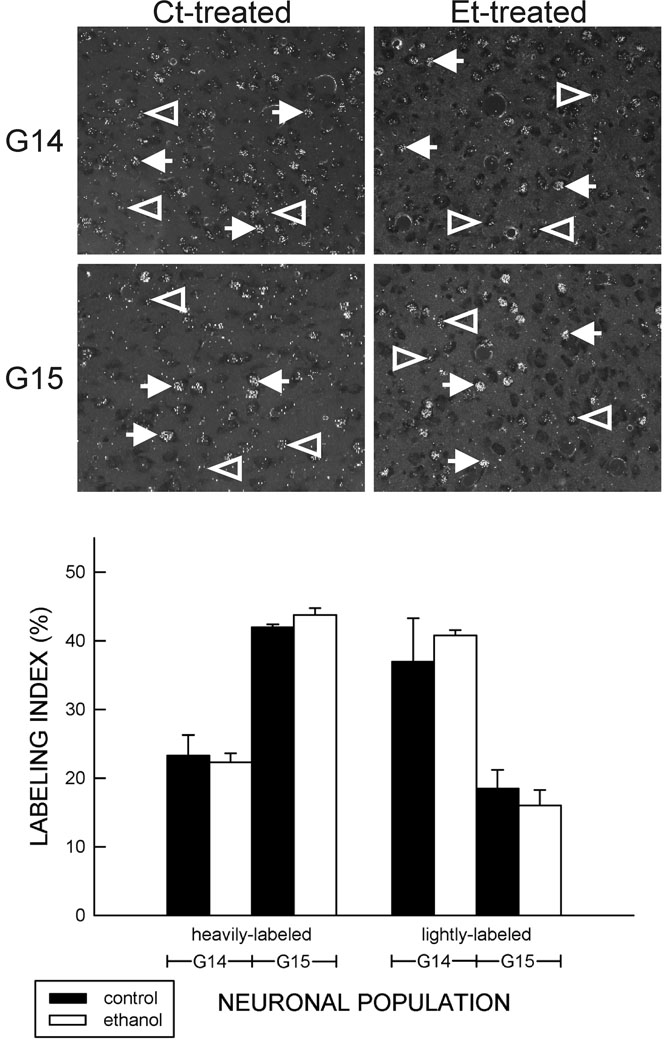

Neurons in the VB of 21-day-old Ct-treated rats were heavily-labeled by an injection of [3H]dT on G14 or G15 (Fig. 4). No heavily-labeled neurons were evident in the VB of 21-day-old animals following an injection on G13, G16, or G17 (data not shown). This pattern of labeling concurred with that previously described (Altman and Bayer, 1989; Mooney and Miller, 2007). Twice as many lightly-labeled neurons were apparent after [3H]dT injection on G14 than on G15 suggesting (a) that neuronal progenitors in the cell cycle on G14 underwent at least one more mitotic division or (b) that these cells were first generation neurons located too deep within the tissue section to be categorized as heavily labeled. In contrast, after injection on G15, twice as many heavily-labeled neurons were apparent suggesting that most progenitors had exited the cell cycle.

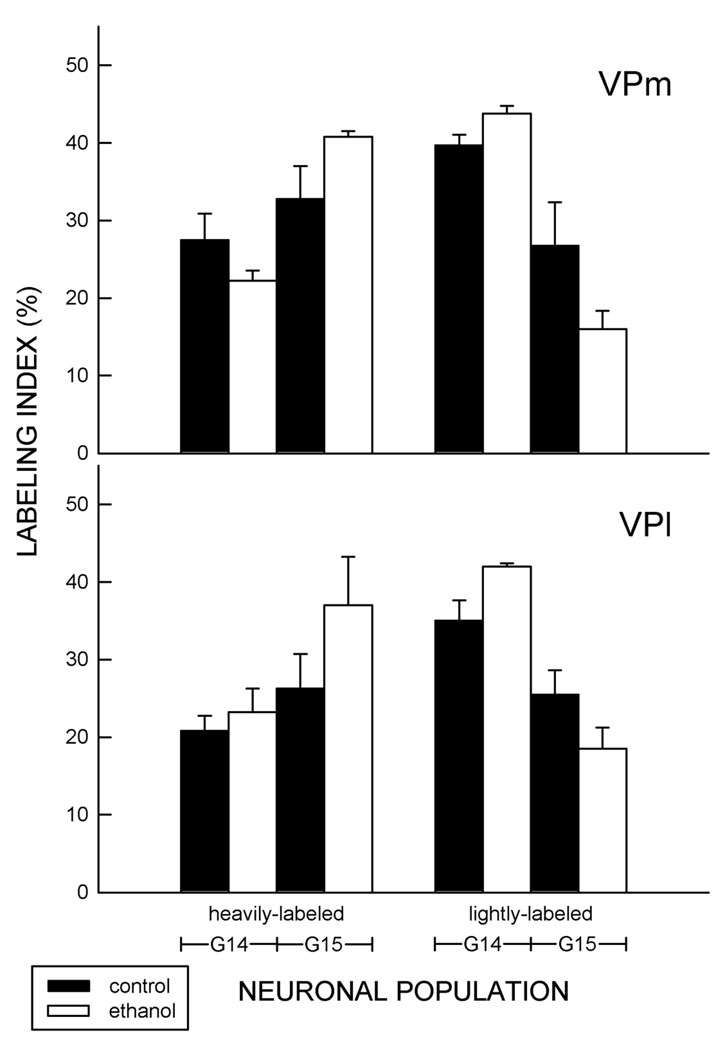

Figure 4. Prenatal neuronal generation in the VB.

Top. Dark-field images of [3H]thymidine ([3H]dT) labeling in the ventral posterior medial nucleus (VPm) after injection on G14 (top) or G15 (bottom) are shown. Cells in the ventrobasal nucleus (VB) were heavily-labeled (solid arrows) by an injection of [3H]dT on G14 or G15. Lightly-labeled neurons are indicated by open arrows. No differences between control (left) or ethanol-treated (right) animals were apparent. VPI, ventral posterior lateral nucleus.

Bottom. Prenatal exposure to ethanol including the period of VB neurogenesis did not significantly affect [3H]dT incorporation. This was evident for both heavily- and lightly-labeled neurons. Each bar depicts the means of five animals (± the standard errors of the means).

Prenatal exposure to ethanol did not significantly alter the number of cells in the VB of 21-day-old animals that incorporated [3H]dT on G14 or G15, nor did it alter the proportion of cells that were heavily- or lightly-labeled. The lack of an ethanol-induced change was evident in the VPm and VPl (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Prenatal neurogenesis in VB subnuclei.

Pregnant animals were injected with [3H]thymidine on gestational day (G) 14 or G15. The labeling indices for labeling in the ventral posterior medial nucleus (VPm; top) and ventral posterior lateral nucleus (VPl; bottom) in 21-day-old pups is shown. Data are parsed based on the amount of autoradiographic labeling over a nucleus, i.e., cells were identified as being lightly- or heavily-labeled. n = 5.

Postnatal generation of neurons in the VB

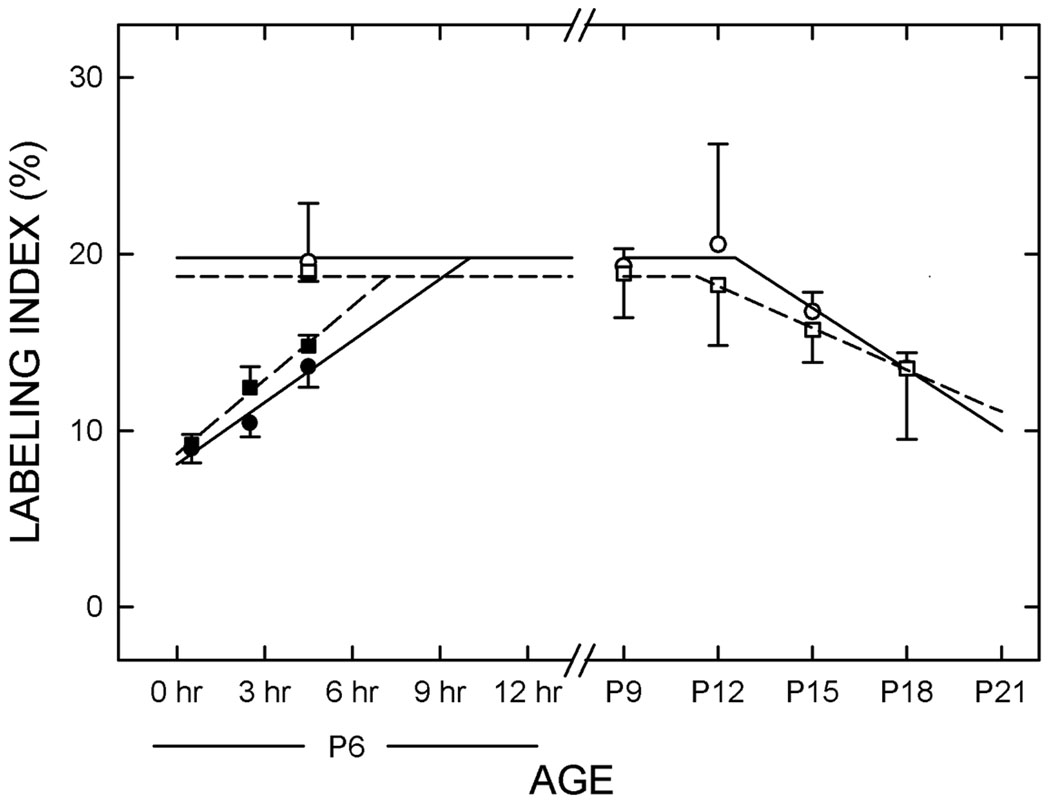

The effect of prenatal exposure to ethanol on the postnatal production of VB neurons was examined through studies of cell cycle kinetics and immunolabeling studies. The proportion of cells that were proliferating was indicated by the frequency of cells expressing Ki-67. On P6, P9, and P12, ~20% of the VB cells in Ct- and Et-treated pups were Ki-67-positive (Fig. 6; Supplementary Table IV). Note that this proportion includes neurons, glia, and progenitor cells. Endothelial cells were excluded based on their morphology. At the end of the second postnatal week, the frequency of cycling cells started to decline. It is noteworthy that most of the Ki-67-positive cells must be considered as neuronal progenitors because double-labeling studies reveal that BrdU incorporated on P6 is expressed mainly by neurons on P12 (Mooney and Miller, 2007).

Figure 6. Cell cycle kinetics in the early postnatal period.

The data from the Ki-67 labeling study were combined with those from the bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) cumulative labeling study to determine the cell cycle kinetics. The labeling index for Ki-67 immunolabeling (the ratio of the number of Ki-67-positive cells to the total number of cells) was determined at various times (on P6, P9, P12, P15, and P18) in control- (solid squares and solid lines) and ethanol-treated (open squares and dashed lines) rats. The BrdU labeling index was determined 0.5, 2.5, or 4.5 hr after the BrdU was administered. The data for controls is displayed as solid circles and solid lines and the data for the ethanol-treated rats is represented by open circles and dashed lines. n = 3 to 4.

The data from the Ki-67 labeling study were combined with those from the BrdU cumulative labeling study to determine the cell cycle kinetics. The total length of the cell cycle (Tc) was significantly (p<0.05) shorter in Et-exposed rats than in controls (11.4 ± 0.9 hr in Et-treated animals vs. 17.3 ± 1.1 hr in Ct-treated rats). Similarly, the length of S phase (Ts) was significantly (p<0.05) shorter in Et-treated animals (4.2 ± 0.3 hr) than in controls (7.0 ± 0.9 hr).

In Ct-treated animals, approximately 8,000 new neurons were added daily between P6 and P12. In contrast, prenatal exposure to ethanol increased the number of neurons added per day to approximately 12,200, a 52% increase over Ct-treated animals. Coincidentally, this percentage change is the same as the difference in Tc.

DISCUSSION

Effects of ethanol on cell proliferation in the VB

A [3H]dT birthdating study (wherein neurons are tagged prenatally and identified in mature animals) provides information about the production and survival of prenatally generated VB neurons. The lack of an ethanol-induced change in the numbers of heavily-labeled neurons implies that ethanol affects neither process. This conclusion is supported by evidence from a stereological study of the temporal change in the number of VB neurons. Accordingly, the numbers of VB neurons in ethanol- and control-treated rats during the first few postnatal days are similar. This includes the peak number of VB neurons (which reflects the number of neurons generated prenatally) achieved on the day of birth (Waite et al., 1992) and the rapid fall to a nadir (an index of neuronal loss) on P3.

In contrast to prenatal generation of VB neurons, ethanol alters the pattern of postnatal neurogenesis. (1) During the second postnatal week, between P6 and P12, the number of VB neurons rises faster in Et-treated rats. This likely results, at least in part, from the ethanol-induced shortening of the cell cycle detected on P6. One consequence of a shorter cell cycle is that proliferating cells can pass through more cell cycles in a defined period. In the case of the VB, ~50% additional cells can be produced daily in Et-treated animals than in controls. It is noteworthy that at least some of the postnatally generated cells become neurons and form connections with somatosensory cortex, whereas other newly generated cells are glia (Mooney and Miller, 2007). (2) Neuronal number decreases between P21 and P30 in control rats, hence, cell death must occur during this time. In contrast, there is no net change in the number of VB neurons in Et-treated rats between P12 and P30. There are two explanations for this finding. (a) There is no neuronal death between P12 and P30. This possibility is supported by biochemical studies showing that the ratio of bcl2 expression to bax expression and the amount of caspase 3 expression in the VB are stable during this period in both Et- and Ct-treated rats (Mooney and Miller, 2001). (b) Any death occurring in Et-treated rats is balanced by the generation of new neurons. In this case, the amount of neuronal death is similar in both Et- and Ct-treated rats, and the stability in neuronal number in Et-treated rats derives from an ethanol-induced increase in cell proliferation. .

An alternative possibility to ethanol-induced death of the newly produced cells is that proliferation of VB neurons is affected, i.e., the effect of prenatal exposure to ethanol on the population of postnatally cycling cells is dynamic. That is, although the cell cycle is shorter on P6, (1) it may differ as the rat ages, thereby altering the rate of addition of cells or (2) Et treatment may cause the depletion of progenitors by inducing cycling cells to prematurely exit the cell cycle. The second inflexion point in the graph of cell cycle kinetics (Fig. 4) shows that the reduction in the proportion of Ki-67-positive cells begins on P11 in Et-treated rats and on P12.5 in controls. Thus, there could be an earlier depletion of the progenitor pool, even though the proportion of cycling cells on any given day, and most importantly on P12, is not significantly different in Et- and Ct-treated animals.

Comparison to other neurogenic sites

In addition to the VB, postnatal neurogenesis occurs in two other forebrain sites in the rat brain, the subventricular zone (SZ; Altman, 1969; Kaplan and Hinds, 1977; Bayer, 1983; Luskin, 1993; Gritti et al., 2002) and the dentate gyrus (e.g., Altman and Das, 1965; Angevine, 1965; Schlessinger et al., 1978; Lois and Alvarez-Buylla, 1994). Ethanol affects postnatal neurogenesis in the SZ and dentate gyrus. In the SZ, exposure to moderate ethanol affects cell proliferation by increasing the GF without altering the Tc (Miller and Nowakowski, 1991). In the dentate gyrus, ethanol also has a stimulatory effect, but only when the exposures are low/moderate (Miller, 1995b). High doses decrease cell production (Miller, 1995b; Nixon and Crews, 2002; Crews et al., 2006; Redila et al., 2006). Note that in all of these previous studies, the ethanol was administered as the cells were proliferating.

An interesting aspect of the present study is that the effects of ethanol on postnatal neurogenesis occur days after ethanol is cleared from the fetal system. Such latent ethanol-induced effects are not uncommon. On a cellular level, prenatal exposure to ethanol can have long-lasting depressive effects on postnatal neurogenesis in the subgranular zone of the dentate gyrus (Miller and Spear, 2006; Redila et al., 2006; Klintsova et al., 2007). On an organismal level, preference for ethanol as an adolescent or adult can be shaped by fetal alcohol exposure (Youngentob et al., 2007a; 2007b). One mechanism for such alterations is through the neural stem cells that continue to populate the olfactory mucosa and bulb in the older animals. Thus, based on data from multiple structures where postnatal neurogenesis occurs, there is an emerging pattern that early ethanol exposure can lead to latent dynamic effects that become evident well after the ethanol exposure is completed.

Based on the new present data, a number of questions regarding the disposition of the newly generated neurons can be raised. Cells produced in the early postnatal period express markers of either neurons or glia (Mooney and Miller, 2007). Some of these neurons survive at least three weeks and project to somatosensory cortex. It is not known whether prenatal exposure to ethanol alters the fate or connectivity of the newly generated neurons. Further studies are needed to determine the role of these neurons, the importance of them to the system, their survivability, and whether there are functional differences between neurons generated prenatally and those generated postnatally.

Relevance to FASD

The VB responds to ethanol differently than other brain areas. There is no effect on the proliferating cells in the prenatal period, i.e., when the ethanol is present. In contrast, prenatal ethanol exposure has a latent effect on cells proliferating postnatally. The net result is that ethanol does not affect the total number of neurons in the developing VB. This concurs with previous findings on neuronal number (Mooney and Miller, 1999) and the lack of effect of prenatal exposure to ethanol on biochemical indicators of cell death in the mature thalamus (Mooney and Miller, 2001) and glucose utilization in the VB (Miller and Dow-Edwards, 1993).

Postnatal neurogenesis in the VB allows for compensatory responses to ethanol-induced damage. Such responses are not evident in other brain areas that are largely or totally devoid of postnatal neurogenesis. That said, compensatory responses can occur in cortical development where, like the VB, neurons are generated in two sites. Increased proliferation in the cortical SZ (Miller, 1986; 1988; Miller and Nowakowski, 1991) or subgranular zone of the dentate gyrus (Miller, 1995) makes up for early losses in VZ-derived neurogenesis.

Matching the numbers of neurons in structures that are part of the same pathway is necessary for maximizing function. For example, interactions between thalamus and cerebral cortex depend upon proper matching of afferents and target. When matching fails to develop or becomes unbalanced due to a trauma, memory deficits ensue (Armstrong-James et al., 1988). In other words, optimized thalamocortical and corticothalamic systems are essential for memory. Thus, an ethanol-induced mismatch in thalamocortical afferent and target likely underlie the cognitive deficits associated with FASD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Shirley Knapp, Renee Mezza, and Wendi Burnette for technical assistance. This research was supported by the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (AA015413 to SMM, AA06916 and AA07568 to MWM), Autism Speaks (SMM), and the Department of Veterans Affairs (MWM).

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- AChE

acetylcholinesterase

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- BrdU

bromodeoxyuridine

- Ct

isocaloric non-alcoholic liquid diet

- Et

ethanol-containing diet

- G

gestational day

- GF

growth fraction

- [3H]dT

tritiated thymidine

- P

postnatal day

- PB

0.10 M phosphate buffer

- PSN

principal sensory nucleus of the trigeminal nerve

- sem

standard error of the mean

- SZ

subventricular zone

- TC

length of the total cell cycle

- TS

length of S-phase

- TPB

PB containing 0.10% Triton X100

- TPBS

0.010 M phosphate buffered saline containing 0.10% Tween-20

- VB

ventrobasal nucleus of the thalamus

- VPm

medial subnucleus of the ventral posterior nucleus

- VPl

lateral subnucleus of the ventral posterior nucleus

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

LITERATURE CITED

- Altman J. Autoradiographic and histological studies of postnatal neurogenesis. IV. Cell proliferation and migration in the anterior forebrain, with special reference to persisting neurogenesis in the olfactory bulb. J. Comp. Neurol. 1969;137:433–457. doi: 10.1002/cne.901370404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman J, Bayer SA. Development of the rat thalamus: IV. The intermediate lobule of the thalamic neuroepithelium, and the time and site of origin and settling pattern of neurons of the ventral nuclear complex. J. Comp. Neurol. 1989;284:534–566. doi: 10.1002/cne.902840405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman J, Das GD. Autoradiographic and histological evidence of postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis in rats. J. Comp. Neurol. 1965;124:319–335. doi: 10.1002/cne.901240303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angevine JB., Jr Time of neuron origin in the hippocampal region. An autoradiographic study in the mouse. Exp. Neurol. 1965;2 Suppl.:1–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong-James M, Ross DT, Chen F, Ebner FF. The effect of thiamine deficiency on the structure and physiology of the rat forebrain. Metab. Brain Dis. 1988;3:91–124. doi: 10.1007/BF01001012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldi A, Calia E, Ciampini A, Riccio M, Vetuschi A, Persico AM, Keller F. Deafferentation-induced apoptosis of neurons in thalamic somatosensory nuclei of the newborn rat: critical period and rescue from cell death by peripherally applied neurotrophins. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2000;12:2281–2290. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer SA. 3H-Thymidine-radiographic studies of neurogenesis in the rat olfactory bulb. Exp. Brain Res. 1983;50:329–340. doi: 10.1007/BF00239197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. 2006 http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/fas/fasask.htm#how.

- Crews FT, Mdzinarishvilli A, Kim D, He J, Nixon K. Neurogenesis in adoilescent brain is potently inhibited by ethanol. Neurosci. 2006;137:437–445. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.08.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockett DP, Harris SL, Egger MD. Neurotrophin receptor (p75) in the trigeminal thalamus of the rat: development, response to injury, transient vibrissa-related patterning, and retrograde transport. Anat. Rec. 2000;259:446–460. doi: 10.1002/1097-0185(20000801)259:4<446::AID-AR80>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Badawi A, Schenk EA. Histochemical methods for separate, consecutive and simultaneous demonstration of acetylcholinesterase and norepinephrine in cryostat sections. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1967;15:580–588. doi: 10.1177/15.10.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gritti A, Bonfanti L, Doetsch F, Caille I, Alvarez-Buylla A, Lim DA, Galli R, Verdugo JM, Herrera DG, Vescovi AL. Multipotent neural stem cells reside into the rostral extension and olfactory bulb of adult rodents. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:437–445. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-02-00437.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrup K, Shojaeian-Zanjani H, Panzini L, Sunter K, Mariani J. The numerical matching of source and target populations in the CNS: the inferior olive to Purkinje cell projection. Dev. Brain Res. 1996;96:28–35. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(96)00069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrup K, Sunter K. Numerical matching during cerebellar development: quantitative analysis of granule cell death in staggerer mouse chimeras. J. Neurosci. 1987;7:829–836. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-03-00829.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EG. The Thalamus. 2nd ed. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan MS, Hinds JW. Neurogenesis in the adult rat: electron microscopic analysis of light radiographs. Science. 1977;197:1092–1094. doi: 10.1126/science.887941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein BG, Renehan WE, Jacquin MF, Rhoades RW. Anatomical consequences of neonatal infraorbital nerve transection upon the trigeminal ganglion and vibrissa follicle nerves in the adult rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 1988;268:469–488. doi: 10.1002/cne.902680402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klintsova AY, Helfer JL, Calizo LH, Dong WK, Goodlett CR, Greenough WT. Persistent impairment of hippocampal neurogenesis in young adult rats following early postnatal alcohol exposure. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2007;31:2073–2082. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koelle GB, Friedenwald JA. A histochemical method for localizing cholinesterase activity. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1949;70:617–622. doi: 10.3181/00379727-70-17013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristt DA. Acetylcholinesterase in the ventrobasal thalamus: transience and patterning during ontogenesis. Neurosci. 1983;10:923–939. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(83)90230-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lois C, Alvarez-Buylla A. Long-distance neuronal migration in the adult mammalian brain. Science. 1994;264:1145–1148. doi: 10.1126/science.8178174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luskin MB. Restricted proliferation and migration of postnatally generated neurons derived from the forebrain subventricular zone. Neuron. 1993;11:173–189. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90281-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW. Fetal alcohol effects on the generation and migration of cerebral cortical neurons. Science. 1986;233:1308–1311. doi: 10.1126/science.3749878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW. Effect of prenatal exposure to alcohol on the distribution and time of origin of corticospinal neurons in the rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 1987;257:372–382. doi: 10.1002/cne.902570306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW. Effect of prenatal exposure to ethanol on the development of cerebral cortex: I. Neuronal generation. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1988;12:440–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1988.tb00223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW. Circadian rhythm of cell proliferation in the telencephalic ventricular zone: effect of in utero ethanol exposure. Brain Res. 1992;595:17–24. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91447-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW. Effect of pre- or postnatal exposure to ethanol on the total number of neurons in the principal sensory nucleus of the trigeminal nerve: cell proliferation and neuronal death. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1995a;19:1359–1363. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW. Generation of neurons in the rat dentate gyrus and hippocampus: effects of prenatal and postnatal treatment with ethanol. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1995b;19:1500–1509. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW. A longitudinal study of the effects of prenatal exposure on neuronal acquisition and death in the principal sensory nucleus of the trigeminal nerve: interaction with changes induced by transection of the infraorbital nerve. J. Neurocytol. 1999;28:999–1015. doi: 10.1023/a:1007088021115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW. Normal Processes and the Effects of Alcohol and Nicotine. New York: Oxford Univ Press; 2006. Brain Development. [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW, Al-Ghoul WM, Murtaugh M. Expression of ALZ-50-immunoreactivity in the developing principal sensory nucleus of the trigeminal nerve: effect of transecting the infraorbital nerve. Brain Res. 1991;560:132–138. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91223-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW, Dow-Edwards DL. Vibrissal stimulation affects glucose utilization in the trigeminal/somatosensory system of normal rats and rats prenatally exposed to ethanol. J. Comp. Neurol. 1993;335:283–294. doi: 10.1002/cne.903350211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW, Muller SJ. Structure and histogenesis of the principal sensory nucleus of the trigeminal nerve: effects of prenatal exposure to ethanol. J. Comp. Neurol. 1989;282:570–580. doi: 10.1002/cne.902820408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW, Nowakowski RS. Use of bromodeoxyuridine-immunohistochemistry to examine the proliferation. migration and time of origin of cells in the central nervous system. Brain Res. 1988;457:44–52. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW, Nowakowski RS. Effect of prenatal exposure to ethanol on the cell cycle kinetics and growth fraction in the proliferative zones of fetal rat cerebral cortex. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1991;15:229–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1991.tb01861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW, Potempa G. Numbers of neurons and glia in mature rat somatosensory cortex: effects of prenatal exposure to ethanol. J. Comp. Neurol. 1990;293:92–102. doi: 10.1002/cne.902930108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW, Spear LP. The alcoholism generator. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2006;30:1466–1469. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooney SM, Miller MW. Effects of prenatal exposure to ethanol on systems matching:the number of neurons in the ventrobasal thalamic nucleus of the mature rat. Dev. Brain Res. 1999;117:121–125. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(99)00111-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooney SM, Miller MW. Effects of prenatal exposure to ethanol on the expression of bcl-2, bax and caspase 3 in the developing rat cerebral cortex and thalamus. Brain Res. 2001;911:71–81. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02718-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooney SM, Miller MW. Postnatal neuronogenesis in the ventrobasal nucleus of the thalamus. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:5023–5032. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1194-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon K, Crews FT. Binge ethanol exposure decreases neurogenesis in adult rat hippocampus. J. Neurochem. 2002;83:1087–1093. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowakowski RS, Lewin SB, Miller MW. Bromodeoxyuridine immunohistochemical determination of the lengths of the cell cycle and the DNA-synthetic phase for an anatomically defined population. J. Neurocytol. 1989;18:311–318. doi: 10.1007/BF01190834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. New York: Academic Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Pentney R, Miller MW. Effects of ethanol on neuronal morphogenesis. In: Miller MW, editor. Development of the Central Nervous System: Effects of Alcohol and Opiates. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1992. pp. 47–69. [Google Scholar]

- Rakic P, Nowakowski RS. The time of origin of neurons in the hippocampal region of the rhesus monkey. J. Comp. Neurol. 1981;196:99–128. doi: 10.1002/cne.901960109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redila VA, Olson AK, Swann SE, Mohades G, Webber AJ, Weinberg J, Christie BR. Hippocampal cell proliferation is reduced following prenatal ethanol exposure but can be rescued with voluntary exercise. Hippocampus. 2006;16:305–311. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savy C, Margules S, Farkas-Bargeton E, Verley R. A morphometric study of mouse trigeminal ganglion after unilateral destruction of vibrissae follicles at birth. Brain Res. 1981;217:265–277. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)90003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlessinger AR, Cowan WM, Swanson LW. The time of origin of neurons in Ammon's horn and the associated retrohippocampal fields. Anat. Embryol. (Berl) 1978;154:153–173. doi: 10.1007/BF00304660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegenthaler JA, Miller MW. Transforming growth factor beta 1 promotes cell cycle exit through the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 in the developing cerebral cortex. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:8627–8636. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1876-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolen AJ, Wright LL, Cunningham TJ. Neuron numbers in the superior cervical sympathetic ganglion of the rat: a critical comparison of methods for cell counting. J. Neurocytol. 1983;12:739–750. doi: 10.1007/BF01258148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel MW, Sunter K, Herrup K. Numerical matching between granule and Purkinje cells in lurcher chimeric mice: a hypothesis for the trophic rescue of granule cells from target-related cell death. J. Neurosci. 1989;9:3454–3462. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-10-03454.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waite PM. Rearrangement of neuronal responses in the trigeminal system of the rat following peripheral nerve section. J. Physiol. 1984;352:425–445. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waite PE, Li L, Ashwell KWS. Developmental and lesion induced cell death in the rat ventrobasal complex. Neuroreport. 1992;3:485–488. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199206000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngentob SL, Kent PF, Sheehe PR, Molina JC, Spear NE, Youngentob LM. Experience-induced fetal plasticity: the effect of gestational ethanol exposure on the behavioral and neurophysiologic olfactory response to ethanol odor in early postnatal and adult rats. Behav. Neurosci. 2007a;121:1293–1305. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.121.6.1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngentob SL, Molina JC, Spear NE, Youngentob LM. The effect of gestational ethanol exposure on voluntary ethanol intake in early postnatal and adult rats. Behav. Neurosci. 2007b;121:1306–1315. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.121.6.1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]