Abstract

Low-income adults suffer more severe tooth loss and are less likely to have had a dental visit than their wealthier counterparts. Insurance coverage increases the likelihood of a dental visit, but lower income older adults are less likely to have dental coverage than those with higher incomes. This is further complicated for many older workers who face losing health benefits from their employer as they plan their retirement. The purpose of this article is to consider more closely the relationship of dental care coverage, retirement, and utilization in an aging population, using data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS). We estimate dental care use as a function of dental care coverage status, retirement, and individual and household characteristics. Overall, sixty-six percent of all older adults had a dental visit during the two year period ending in 2006. Controlling for confounding variables our logistic regression model shows that fully retired persons are actually more likely to have had a dental visit than persons who are not retired. These results suggest that the loss of income and dental coverage associated with retirement may lead to lower use rates but this effect may be offset by other unobserved aspects of retirement including more available free time leading to an overall higher use rate. We posit and present a model showing the role of retirement whereby retirement acts as the independent variable and where income, coverage and free time (unobserved) are intervening variables.

Keywords: Dental, Utilization, Dentistry, Insurance, Coverage, Retirement

Introduction

Approximately three quarters of the elderly report dental symptoms, and half perceive their dental health as poor or very poor.[1] Low-income adults suffer more severe tooth loss and are less likely to have had a dental visit than their wealthier counterparts.[2-3] Although the failure to receive needed care may result in poorer oral health, only 43% of the older adult population had at least one dental visit during 2004.[2] Overall, forty-eight percent of all older adults had dental coverage during 2006.[4-5] Insurance coverage increases the likelihood of a dental visit, but there is an income gradient in coverage such that lower income older adults are less likely to have dental coverage than those with higher incomes.[4-5] At the time of retirement, many workers lose health benefits from their employer; a change that is likely to get larger as offers of retiree benefits fall.[6] Further, Medicare, which nearly universally provides health insurance to Americans age 65 and older, does not cover routine dental care.[7]

The purpose of this article is to consider more closely the relationship of dental care coverage, retirement, and utilization in an aging population, using data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS). We estimate dental care use as a function of dental care coverage status, retirement, and individual and household characteristics. Specifically, we calculate national estimates of the number, percent of the population, and characteristics of those persons age 51 years and above with a dental visit, by dental coverage and retirement status.

Methods

The Health and Retirement Study (HRS) is a nationally representative longitudinal household survey that interviews individuals over age 50 and their spouses every two years; approximately 20,000 interviews are completed in each survey wave. Administered by the Institute for Social Research (ISR) at the University of Michigan and sponsored by the National Institute on Aging, the HRS is useful for the study of aging, retirement, and health among older populations in the United States.[8-9]1 Each respondent is asked a large battery of questions including information about demographics; income and assets; physical and mental health; cognition, family structure and social supports; health care utilization and costs; health insurance coverage; labor force status and job history; and retirement planning and expectations. Because of the breadth of data available across health and labor force measures and the large sample of older Americans, the HRS is the ideal data source for assessing the association between dental coverage, use, and retirement among an older population.

This analysis focuses on self reports in the HRS of whether or not a person visited the dentist for dental care at least once during the two-year period prior to the most recent survey in 2006. Survey respondents are designated as fully retired if at the time of the survey interview they were not working for pay or self-employed and either (1) said that they were completely retired, or (2) reported their sole employment status as retired. Individuals are classified as partially retired if they were not fully retired but report retirement and either working or looking for work. Individuals not classified as fully or partly retired are designated as in the labor force if they report working for pay or report their labor force status as working full-time, part-time, or unemployed. Persons are classified as not retired and out of the labor force if they report being disabled, not in the labor force or never in the labor force.

Along with calculating the bivariate relationships between dental visits and dental coverage, retirement status, and other person and household characteristics, we also estimate a logistic regression model of the association of dental service use with retirement status and dental coverage, controlling for other potentially confounding variables.

The HRS core sample design is a multistage area probability sample of households, so all estimates and statistics reported were computed taking into account this design with the use of the software packages SUDAAN and STATA. [10-11]

Results

The 16,911 participants in the 2006 HRS represented 76,367,762 members of the community-based population age 51 and above in that year, and comprise the study sample. Of these, more than half of the participants were female (58 percent, N=9,722). Fourteen percent (N=2,349) of the participants were non-Hispanic Black and 9 percent (N=1,523) were Hispanic. Twenty-eight percent (N=4,696) of the participants were age 75 or older, 36 percent (N=6,158) were between the ages of 65 and 74, and 36 percent (N=6,057) were between the ages of 51 and 64. More than half the sample (52 percent, N=8,877) were classified as fully retired; 10 percent (N=1,652) as partially retired; 26 percent (N=4,315) as not retired and in the labor force; and 12 percent (N=2,067) as not retired and out of the labor force.

Descriptive Results

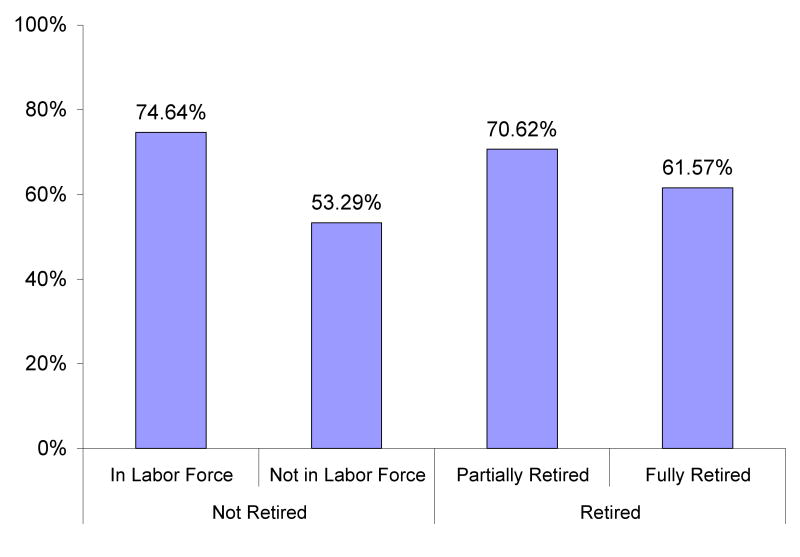

Overall, 66 percent of all older adults had a dental visit during the two year period ending in 2006 (Table 1). Figure 1 shows the percent of the population age 51 years and above with a dental visit in the two year period ending in 2006 by labor force and retirement status. There was a gradient in the likelihood of use by retirement status; 75 percent of those not retired and out of the labor force had a dental visit in the previous two years, compared with 71 percent of those partially retired, 62 percent of the fully retired, and 53 percent of those not retired and out of the labor force.

Table 1. Weighted Estimates.

Number, percent and characteristics of persons age 51 years and above in the two year period ending in 2006 with a dental visit by retirement status.

| Not Retired In Labor Force | Fully Retired | Partially Retired | Not Retired Out of Labor Force | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population characteristic | Total Population | Percent Population With Dental Visit | Total Population | Percent Population With Dental Visit | Total Population | Percent Population With Dental Visit | Total Population | Percent Population With Dental Visit | Total Population | Percent Population With Dental Visit |

| Total | 76,367,762 | 66.08 | 27,026,355 | 74.64 | 33,738,154 | 61.57 | 6,942,509 | 70.62 | 8,660,744 | 53.29 |

| 0.84 | 0.95 | 1.11 | 1.54 | 1.75 | ||||||

| Age in years | ||||||||||

| 51 to 64 | 40,059,704 | 70.64 | 24,044,316 | 75.34 | 8,390,652 | 64.12 | 3,229,179 | 72.95 | 4,395,557 | 55.71 |

| 0.95 | 0.97 | 1.82 | 2.32 | 2.49 | ||||||

| 65 to 74 | 19,070,630 | 64.37 | 2,599,961 | 69.62 | 12,049,010 | 63.56 | 2,672,783 | 69.50 | 1,748,876 | 54.35 |

| 1.21 | 1.76 | 1.25 | 1.99 | 2.26 | ||||||

| 75 and over | 17,237,428 | 57.37 | 382,078 | 64.93 | 13,298,492 | 58.17 | 1,040,547 | 66.28 | 2,516,311 | 48.34 |

| 1.16 | 5.50 | 1.25 | 3.44 | 2.42 | ||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Male | 34,813,702 | 64.92 | 14,080,596 | 71.33 | 15,565,561 | 59.35 | 3,882,070 | 70.53 | 1,285,475 | 45.21 |

| 0.95 | 1.13 | 1.33 | 1.99 | 3.84 | ||||||

| Female | 41,554,060 | 67.06 | 12,945,759 | 78.24 | 18,172,593 | 63.48 | 3,060,439 | 70.74 | 7,375,269 | 54.70 |

| 0.90 | 1.19 | 1.17 | 2.18 | 1.68 | ||||||

| Race | ||||||||||

| Black Non-Hispanic | 6,954,398 | 47.12 | 2,408,306 | 58.72 | 3,010,198 | 41.60 | 533,453 | 55.57 | 1,002,441 | 31.33 |

| 1.66 | 2.54 | 1.74 | 4.62 | 3.73 | ||||||

| Hispanic | 5,366,874 | 48.47 | 2,004,130 | 57.11 | 1,576,080 | 45.72 | 238,990 | 41.00 | 1,547,674 | 41.24 |

| 3.04 | 3.86 | 4.53 | 6.93 | 3.15 | ||||||

| White Non-Hispanic | 62,060,861 | 69.95 | 21,762,316 | 78.37 | 28,469,702 | 64.87 | 6,012,262 | 73.15 | 5,816,581 | 60.00 |

| 0.85 | 0.91 | 1.21 | 1.65 | 1.85 | ||||||

| Other | 1,985,629 | 59.13 | 851,603 | 65.58 | 682,174 | 48.58 | 157,804 | 70.29 | 294,048 | 58.92 |

| 3.67 | 4.83 | 4.77 | 8.89 | 8.64 | ||||||

| Family Income a | ||||||||||

| Poor | 5,966,351 | 38.11 | 861,217 | 49.87 | 3,021,476 | 37.74 | 262,147 | 51.16 | 1,821,511 | 31.28 |

| 1.90 | 4.54 | 2.78 | 7.53 | 2.93 | ||||||

| Low Income | 12,254,186 | 46.22 | 1,705,339 | 45.18 | 7,558,701 | 47.10 | 814,512 | 48.82 | 2,175,634 | 43.01 |

| 1.19 | 3.65 | 1.15 | 5.23 | 2.67 | ||||||

| Middle income | 22,083,996 | 60.81 | 5,769,977 | 60.12 | 11,913,169 | 61.91 | 2,023,837 | 62.37 | 2,377,013 | 55.67 |

| 1.22 | 1.93 | 1.43 | 2.81 | 2.32 | ||||||

| High income | 36,063,229 | 80.68 | 18,689,822 | 82.95 | 11,244,808 | 77.35 | 3,842,013 | 80.92 | 2,286,586 | 78.14 |

| 0.65 | 0.72 | 1.27 | 1.61 | 2.12 | ||||||

| Education | ||||||||||

| Some or no school | 13,555,848 | 36.41 | 2,424,290 | 40.31 | 7,251,915 | 36.40 | 767,457 | 38.09 | 3,112,186 | 32.97 |

| 1.40 | 2.76 | 1.66 | 3.70 | 1.89 | ||||||

| High school graduate | 44,395,424 | 66.54 | 15,810,061 | 71.68 | 19,952,180 | 63.45 | 3,901,116 | 67.99 | 4,732,067 | 61.19 |

| 0.81 | 1.08 | 1.17 | 1.79 | 1.98 | ||||||

| College graduate | 18,354,991 | 86.95 | 8,777,295 | 89.47 | 6,498,176 | 83.99 | 2,273,936 | 86.13 | 805,584 | 85.80 |

| 0.68 | 0.86 | 1.15 | 1.68 | 3.65 | ||||||

| Marital Status | ||||||||||

| Married | 50,975,418 | 70.94 | 20,529,982 | 76.64 | 20,421,526 | 67.03 | 4,985,398 | 74.29 | 5,038,512 | 60.24 |

| 0.97 | 1.01 | 1.30 | 1.63 | 2.24 | ||||||

| Widowed, Divorced | 22,611,797 | 55.64 | 5,396,040 | 67.91 | 12,224,815 | 52.87 | 1,702,719 | 59.99 | 3,288,223 | 43.52 |

| 1.06 | 1.77 | 1.34 | 2.76 | 2.21 | ||||||

| Never Married | 2,773,339 | 62.07 | 1,095,237 | 70.58 | 1,091,813 | 56.86 | 254,392 | 69.96 | 331,897 | 45.03 |

| 2.55 | 3.87 | 3.58 | 5.75 | 5.22 | ||||||

| Family Size | ||||||||||

| One | 16,246,353 | 59.72 | 3,919,525 | 69.59 | 9,039,513 | 57.33 | 1,314,791 | 62.48 | 1,972,524 | 49.19 |

| 0.98 | 1.78 | 1.33 | 3.06 | 2.39 | ||||||

| Two | 40,622,537 | 70.42 | 13,568,018 | 77.45 | 18,893,437 | 66.80 | 4,247,613 | 75.93 | 3,913,469 | 57.58 |

| 1.05 | 1.15 | 1.37 | 1.85 | 2.59 | ||||||

| Three or more | 19,498,872 | 62.34 | 9,538,812 | 72.73 | 5,805,204 | 51.18 | 1,380,105 | 62.05 | 2,774,751 | 50.16 |

| 1.25 | 1.47 | 1.94 | 3.04 | 2.49 | ||||||

| Health Status | ||||||||||

| Excellent/Very Good | 33,062,282 | 77.96 | 15,435,332 | 81.37 | 11,425,926 | 74.90 | 3,892,179 | 76.77 | 2,308,845 | 72.38 |

| 0.85 | 1.12 | 1.16 | 1.79 | 2.62 | ||||||

| Good | 22,813,107 | 65.54 | 7,949,098 | 69.96 | 10,658,786 | 63.49 | 2,085,131 | 65.97 | 2,120,092 | 58.91 |

| 1.06 | 1.27 | 1.33 | 2.55 | 2.68 | ||||||

| Fair/Poor | 20,402,655 | 47.44 | 3,625,693 | 56.15 | 11,598,557 | 46.73 | 965,199 | 55.88 | 4,213,206 | 39.97 |

| 1.07 | 2.23 | 1.27 | 3.33 | 1.89 | ||||||

| Teeth | ||||||||||

| Has No Teeth | 12,575,712 | 20.87 | 2,148,610 | 25.03 | 7,387,046 | 20.50 | 1,033,960 | 23.34 | 2,006,096 | 16.50 |

| 0.86 | 2.33 | 1.23 | 2.93 | 1.55 | ||||||

| Has Teeth | 63,787,930 | 74.99 | 24,877,745 | 78.93 | 26,346,988 | 73.08 | 5,908,549 | 78.90 | 6,654,648 | 64.39 |

| 0.81 | 0.95 | 1.00 | 1.42 | 1.95 | ||||||

| Dental Coverage | ||||||||||

| Has Coverage | 36,296,560 | 77.57 | 17,688,371 | 83.12 | 12,330,932 | 71.69 | 3,123,214 | 79.24 | 3,154,043 | 67.84 |

| 0.74 | 0.85 | 1.31 | 1.73 | 2.17 | ||||||

| No Coverage | 40,071,202 | 55.67 | 9,337,984 | 58.58 | 21,407,222 | 55.75 | 3,819,295 | 63.58 | 5,506,701 | 44.97 |

| 0.99 | 1.55 | 1.16 | 2.13 | 1.94 | ||||||

Source: RAND HRS Data, Version H. Produced by the RAND Center for the Study of Aging, with funding from the National Institute on Aging and the Social Security Administration. Santa Monica, CA (February 2008).

Note: Persons with missing data for race/ethnicity, education, marital status, and health status are included in the population total but excluded from the respective categories. Persons never in the labor force are included in the not retired, not in the labor force group. Sample size is 16,911.

Standard errors appear beneath estimated dental use percentages in the shaded rows of the table.

Where low income refers to persons in families with incomes 101 percent to 199 percent of the poverty line; middle income, 201 percent to 400 percent of the poverty line; and high income, over 400 percent of the poverty line. Poor persons are at or below 100 percent of the poverty line including persons in families with negative income.

Figure 1. Percent population with a dental visit of persons age 51 years and above for the two year period ending in 2006 by retirement status, labor force status and retirement extent.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study sample with a dental visit, by retirement status, for selected population characteristics. We used z tests to identify differences in use rates across the four groups based on retirement status for a given characteristic. Unless otherwise stated, all reported results are significant at the .05 level.

Fully Retired Compared to Not Retired In The Labor Force

According to Figure 1, fully retired persons are less likely to visit the dentist than non-retired elderly persons still in the labor force. With few exceptions, this impact of full retirement generally holds across population subgroups in Table 1. For example, 78 percent of not retired females in the labor force had a dental visit compared to 63 percent of fully retired females. Significant differences were not found for persons 75 years and older, Hispanic, non-poor, never graduating from high school, and without dental coverage. Very rarely were the dental use rate estimates for the fully retired greater than those of not retired and in the labor force, and in no cases were they statistically significantly greater.

Fully Retired Compared to Partially Retired

In Table 1, fully retired persons were less likely than partially retired persons to visit the dentist. This result generally held up across the population subgroups in Table 1. For example, 73 percent of persons aged 51 to 64 who were partially retired had a dental visit compared to 64 percent of those fully retired in the same age group. The subgroup exceptions included Hispanics, all income groups, the single person family group, college graduates and those with less than a high school education, the never married group, and persons with no worse than good self-reported health status. Only for Hispanics and college graduates did the fully retired have a higher estimated probability of dental use than the partially retired, but the difference was not statistically significant.

Fully Retired Compared to Non-Retired Out Of Labor Force

Among all elderly persons, the fully retired were nearly 10 percentage points more likely to visit the dentist than non-retired persons out of the labor force. This result was also generally widespread across the population subgroups in Table 1. For example, 42 percent of fully retired black, non-Hispanics visited the dentist compared to 31 percent in the same race/ethnicity group who were not retired but out of the labor force. Subgroup exceptions to this general finding occurred among Hispanics, other non-Hispanics, all but middle income classes, college graduates and less than high school education, the never married group, those in families of size three or more, persons with at least good health status, and those without teeth or with dental coverage. Only for other non-Hispanics, high income and college graduate categories was the estimated percentage with a dental visit greater for those not retired and out of the labor force than the fully retired, but in no case was the difference statistically significant.

Other Comparisons

Although partially retired persons in Figure 1 had a lower probability of a dental visit than non-retired persons in the labor force, the difference was only 4 percentage points. More often than not in the population subgroups in Table 1, the differences in use rates between these two groups were not statistically significant. The rare exceptions where this relation did hold up included population groups for females, white non-Hispanics, the widowed and divorced, and for persons in families other than size two, in excellent or very good health, without teeth, and with dental coverage. For example, 68 percent of widowed and divorced persons who were not retired and in the labor force visited the dentist, compared to 60 percent of partially retired widowed and divorced individuals. In some cases the estimated dental use rate for the partially retired group was greater than the rate for the not retired and in the labor force group, such as for persons without dental coverage, but in no case were these differences statistically significant.

Dental visit rates of the non-retired persons out of the labor force for the overall population in Figure 1, and generally across all population subgroups in Table 1, were lower than dental use rates for partially retired persons and those not retired and in the labor force. Other non-Hispanics, persons in low and middle income categories, and college graduates are the only subgroups in which this relation did not hold between the not retired in labor force and not retired out of labor force groups. Between the partially retired and those not retired out of the labor force, the aforementioned relationship did not hold for Hispanics and for persons in poor families, without a high school education, and with at least a good self-reported health status.

Looking down the columns of Table 1, we observe differences in dental use rates within each category of person and household characteristics that are generally independent of retirement status. Particularly strong influences on dental use are found within categories for race/ethnicity, income, education, health status, edentulous status, and dental coverage that persisted regardless of retirement status. For example, in the full population non-Hispanic whites were more likely to have a dental visit (70 percent) than were Hispanics (48 percent) or non-Hispanic blacks (47 percent). Use rates increased with both increased income and education, and individuals in excellent health, not edentulous, and with dental insurance coverage were more likely than those in poorer health, edentulous, and without coverage, respectively, to have a dental visit.

Logistic Regression Results

The complex relationships between characteristics suggests that a better understanding of the association between retirement and dental utilization can be obtained using a multivariate model. Table 2 presents the results of a logistic regression model that controls for confounding factors that could influence the observed association between retirement and dental use. Adjusted odds ratios of the probability of having a dental visit during the two year period ending in 2006 are shown. To help interpret the table, the odds ratio estimate for females of 1.593 indicates that the odds of an elderly female having a dental visit are nearly 60 percent greater than the odds of an elderly male after adjusting for other covariates, where the odds are defined as the probability of a dental visit divided by the probability of not having a dental visit.

Table 2. Adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals for predictors of dental care use during the two-year survey period ending in 2006, HRS Estimates.

| 95 % WaldConfidence Limits | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Population Characteristic | Odds Ratio | Low | High |

| Age | |||

| 51 - 64 | Omitted | ||

| 65 to 74 | 1.187 | 1.048 | 1.343 |

| 75 and over | 1.241 | 1.093 | 1.410 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | Omitted | ||

| Female | 1.593 | 1.476 | 1.720 |

| Ethnic/racial Background | |||

| Black Non-Hispanic | 0.541 | 0.465 | 0.629 |

| Hispanic | 0.766 | 0.603 | 0.974 |

| White | Omitted | ||

| Other | 0.666 | 0.499 | 0.890 |

| Family income by poverty status a | |||

| Poor | 0.351 | 0.283 | 0.435 |

| Low income | 0.457 | 0.388 | 0.537 |

| Middle income | 0.592 | 0.523 | 0.672 |

| High income | Omitted | ||

| Education | |||

| Some or no School | 0.282 | 0.237 | 0.335 |

| High school graduate | 0.502 | 0.436 | 0.578 |

| College graduate | Omitted | ||

| Marital Status | |||

| Married | Omitted | ||

| Widowed, Divorced | 0.707 | 0.599 | 0.833 |

| Never Married | 0.809 | 0.592 | 1.106 |

| Family Size | |||

| One | Omitted | ||

| Two | 0.860 | 0.730 | 1.014 |

| Three or more | 0.690 | 0.583 | 0.816 |

| Teeth Status | |||

| Has Teeth | Omitted | ||

| Has No Teeth | 0.124 | 0.110 | 0.138 |

| Health Status | |||

| Excellent/Very Good | Omitted | ||

| Good | 0.743 | 0.661 | 0.835 |

| Fair/Poor | 0.565 | 0.506 | 0.631 |

| Dental Coverage | |||

| Has Coverage | Omitted | ||

| No Coverage | 0.444 | 0.406 | 0.487 |

| Retirement Status | |||

| Not Retired In Labor Force | Omitted | ||

| Fully Retired | 1.198 | 1.034 | 1.388 |

| Partially Retired | 1.093 | 0.915 | 1.306 |

| Not Retired Out of Labor Force | 1.077 | 0.903 | 1.284 |

Source: RAND HRS Data, Version H. Produced by the RAND Center for the Study of Aging, with funding from the National Institute on Aging and the Social Security Administration. Santa Monica, CA (February 2008).

Note: Reference Groups are indicated by the omitted class for each categorical variable in the table. Sample size is 16,911. Pseudo R2 = 0.25.

Where low income refers to persons in families with incomes 101 percent to 199 percent of the poverty line; middle income, 201 percent to 400 percent of the poverty line; and high income, over 400 percent of the poverty line. Poor persons are at or below 100 percent of the poverty line including persons in families with negative income.

Non-Retirement Status Effects

In Table 2, the odds of having a dental visit were higher for individuals who were female and 65 and older compared to males and persons under 65, respectively. The odds of having a dental visit were lower for widowed or divorced minority persons in middle or lower income groups, without a college degree, in families of size three or more, without teeth and dental coverage, and in good, fair, or poor self-reported health compared to respective married, white non-Hispanics in high income groups with a college degree, living in a single person family, not missing their teeth, with dental coverage, and in excellent or very good health. For example, the odds of an individual without a high school degree having a dental visit are less than one third the odds for a college graduate. Without dental coverage, the odds of having a dental visit are less than half the odds of an individual with coverage.

Retirement Status Effects

Interestingly, controlling for covariates with strong influences on dental use and highly correlated with retirement status, such as income and dental coverage, neutralizes the effect of retirement status on use and even reverses the effect of full retirement observed above. Persons who are fully retired have estimated odds of having a dental visit that are 20 percent greater than those of non-retired persons in the labor force. On the other hand, persons who are partially retired and in the labor force, or who are not retired and out of the labor force, are no more likely to have a dental visit than non-retired persons who are in the labor force.

Discussion

The descriptive statistics in Table 1 highlighted the complex relationships that exists between dental utilization and a range of potential confounders, including age, income, dental coverage, and retirement. The complexity of these relationships led us to model dental utilization in a multivariate framework. Some of the differences we observed between the descriptive and multivariate models were surprising.

Retirement Status Anomaly

The impact of confounding variables in our logistic model on the estimated effect of retirement status on dental use was unexpected. We found a relatively strong relationship between retirement and utilization in the descriptive statistics that did not appear once we controlled for confounders such as income and coverage. We were not surprised that partially retired individuals in our multivariate model were no more likely to have a visit then the non-retired individuals in the labor force because the partially retired likely maintain income and coverage while still attached to the labor force. However, we were surprised that full retirement did not have a significant impact on use. After testing variants of the model in Table 2 without some of the confounding variables, we concluded that the effect of full retirement on dental use is mediated by a loss of income and insurance as well as other unobserved aspects of retirement. As one example, retirees may have more free time than those in the labor force, and may therefore be more inclined to seek dental care.

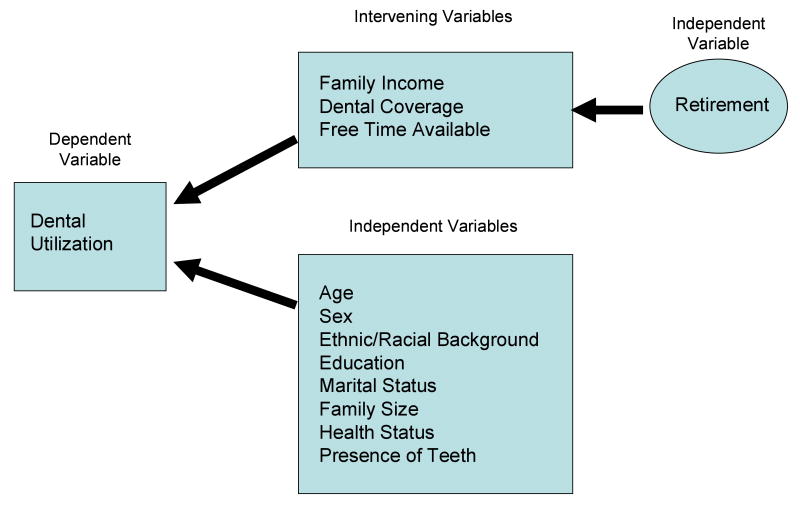

There appear to be competing effects of the impact of full retirement on the use of dental services. On one hand, these retirees usually have lower incomes and rates of dental coverage than before retirement which work in the direction of reducing the likelihood of a dental visit. [13] On the other hand, retirees may have more time available for dental appointments and therefore may have an increased likelihood of visiting the dentist. In Figure 2 we illustrate our analysis of the role of retirement in a model of dental use in which income, coverage and free time (unobserved) behave as intervening variables. Further study is warranted to determine if the availability of free time after retirement, or some other mitigating circumstances, cause an increase in the rate of use among retirees after holding income and coverage constant.

Figure 2. Retirement, Intervening Variables and Dental Utilization.

Age Effect Anomaly

When controlling for confounding variables, the age gradient changes, so that persons 65 to 74 and persons 75 and over were more likely to have had a dental visit than those who were younger. Correlation between age and retirement status suggests that the likely cause of this unexpected finding stems from controlling for confounding variables such as coverage and income that purge age of its dominant effect on dental use. What remains is a secondary age effect that works in the opposite direction and reflects the fact that a growing proportion of U.S. adults are retaining an increasing number of their teeth throughout their life span. [14] Accompanying a need for more preventive dental care as the rate of older Americans without teeth decreases is a relative increase in the need for treatment of coronal and root caries, periodontal diseases, and inadequate or absent prostheses. [15] Jones et al. (1990) notes that older Americans may actually have the highest prevalence of caries as a percentage of retained teeth among all age groups. [16]

Policy Implications

Despite the anomalous age and retirement findings in our logistic model, we conclude from our study that full retirement accompanied by reduced income and dental insurance coverage produces lower utilization of dental services. Loss of dental coverage and income are the driving forces behind this effect as elderly people retire and leave the labor force. Although there are secondary influences that work in the opposite direction, a policy of providing, at a minimum, coverage for preventive dental care to Medicare beneficiaries would be highly effective in promoting dental care and good oral health for our nation's elderly retirees who might currently lack such coverage.

Limitations

The HRS data are useful, comprehensive, and provide estimates that are nationally representative. Nonetheless, they do have limitations. Analyses of data from different survey sources have historically resulted in varied national estimates of dental coverage. The self-reporting of data, as is done in the HRS, is less accurate than collection by observation. Further, data available in the HRS do not disaggregate results by benefit plan generosity or show the extent to which public coverage is included.

Despite some limitations, our results using the HRS appear to comport well with results of other studies. While data from different survey sources have historically resulted in national estimates that vary, one-year use rates typically range from forty-three percent with the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) to sixty-three percent with the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS).[2,12] The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) use rates have ranged from a low of forty-seven percent with NHANES I to fifty-two percent with NHANES II and sixty-seven percent with NHANES III.[12] Our results fall within the upper range of these other surveys, and represent two-year rather than one-year use rates.

Finally, in future research we intend to analyze the effect of retirement on dental use longitudinally with the HRS data, and to estimate any potential bias in our findings from the possible influence of dental use on dental coverage or, more technically, from the potential endogeneity of the dental coverage variable. These are two refinements that go beyond the scope of our current paper and are best addressed with multiple waves of the HRS data.

Acknowledgments

This investigation was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health. (R01 AG026090-01A2, Dental Coverage Transitions, Utilization and Retirement)

The HRS (Health and Retirement Study) is sponsored by the National Institute of Aging (grant number NIA U01AG009740) and is conducted by the University of Michigan.

Footnotes

This analysis uses Early Release data from 2006. These data have not been cleaned and may contain errors that will be corrected in the Final Public Release version of the dataset.

Contributor Information

Richard J. Manski, Division of Health Services Research, Department of Health Promotion and Policy, Dental School, University of Maryland.

John Moeller, Division of Health Services Research, Department of Health Promotion and Policy, Dental School, University of Maryland.

Haiyan Chen, Division of Health Services Research, Department of Health Promotion and Policy, Dental School, University of Maryland.

Patricia A. St. Clair, RAND Corporation

Jody Schimmel, Mathematica Policy Research, Inc.

Larry Magder, Division of Biostatistics, Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, School of Medicine, University of Maryland.

John V. Pepper, Department of Economics, University of Virginia

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manski RJ, Brown E. Dental Use, Expenses, Private Dental Coverage, and Changes, 1996 and 2004. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2007. MEPS Chartbook No.17. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oral Health: Dental Disease Is a Chronic Problem Among Low-Income Populations GAO HEHS-00-72. 2000 April 12; [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manski RJ, Macek MD, Moeller JF. Private Dental Coverage: Who Has it and How Does it Influence Dental Visits and Expenditures? Journal of the American Dental Association. 2002 November;133(11):1551–1559. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2002.0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manski RJ, Goodman HS, Reid BC, Macek MD. Dental Insurance Visits And Expenditures Among Older Adults. American Journal of Public Health. 2004 May;94(5):759–764. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.5.759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Kaiser Family Foundation and Health Research & Educational Trust. Employer Health Benefits: 2008 Annual Survey. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; Sep 24, 2008. Publication Number 7790. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare & You, 2009. Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2008. Publication Number 10050. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Growing Older in America: The Health and Retirement Study. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Aging; 2007. p. 41. Available at http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu. [Google Scholar]

- 9.RAND HRS Data, Version H. Produced by the RAND Center for the Study of Aging, with funding from the National Institute on Aging and the Social Security Administration; Santa Monica, CA: Feb, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Research Triangle Institute. SUDAAN Software for analysis of correlated data Release 6.40. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Statacorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 7.0. College Station, TX: Stata Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Macek MD, Manski RJ, Vargas CM, Moeller JF. Comparing Oral Health Care Utilization Estimates in the U.S. Across Three Nationally Representative Surveys. Health Services Research. 2002 April;37(2):499–521. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manski RJ, Moeller JF, Chen H, St Clair PA, Schimmel J, Magder L, Pepper JV. Dental Care Coverage and Retirement. Journal of Public Health Dentistry. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2009.00137.x. Submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Douglass CW, Ostry L, Shih A. Denture Usage in the United States: a 25-year prediction. Journal of Dental Research. 1998;77(SI A):209. Abstract No. 829. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burt BA. Epidemiology of dental diseases in the elderly. Clinical Geriatric Medicine. 1992;8(3):447–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones J, Adelson R, Niessen LC, Gilbert GH. Issues in financing dental care for the elderly. Journal of Public Health Dentistry. 1990;50(4):268–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1990.tb02134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]