Abstract

Background

Urinary markers were tested as predictors of macroalbuminuria or microalbuminuria in type 1 diabetes.

Study Design

Nested case:control of participants in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT)

Setting & Participants

Eighty-seven cases of microalbuminuria were matched to 174 controls in a 1:2 ratio, while 4 cases were matched to 4 controls in a 1:1 ratio, resulting in 91 cases and 178 controls for microalbuminuria. Fifty-five cases of macroalbuminuria were matched to 110 controls in a 1:2 ratio. Controls were free of micro/macroalbuminuria when their matching case first developed micro/macroalbuminuria.

Predictors

Urinary N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase, pentosidine, AGE fluorescence, albumin excretion rate (AER)

Outcomes

Incident microalbuminuria (two consecutive annual AER > 40 but <= 300 mg/day), or macroalbuminuria (AER > 300 mg/day)

Measurements

Stored urine samples from DCCT entry, and 1–9 years later when macroalbuminuria or microalbuminuria occurred, were measured for the lysosomal enzyme, N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase, and the advanced glycosylation end-products (AGEs) pentosidine and AGE-fluorescence. AER and adjustor variables were obtained from the DCCT.

Results

Sub-microalbuminuric levels of AER at baseline independently predicted microalbuminuria (adjusted OR 1.83; p<.001) and macroalbuminuria (adjusted OR 1.82; p<.001). Baseline N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase independently predicted macroalbuminuria (adjusted OR 2.26; p<.001), and microalbuminuria (adjusted OR 1.86; p<.001).

Baseline pentosidine predicted macroalbuminuria (adjusted OR 6.89; p=.002). Baseline AGE fluorescence predicted microalbuminuria (adjusted OR 1.68; p=.02). However, adjusted for N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase, pentosidine and AGE-fluorescence lost predictive association with macroalbuminuria and microalbuminuria, respectively.

Limitations

Use of angiotensin converting-enzyme inhibitors was not directly ascertained, although their use was proscribed during the DCCT.

Conclusions

Early in type 1 diabetes, repeated measurements of AER and urinary NAG may identify individuals susceptible to future diabetic nephropathy. Combining the two markers may yield a better predictive model than either one alone. Renal tubule stress may be more severe, reflecting abnormal renal tubule processing of AGE-modified proteins, among individuals susceptible to diabetic nephropathy.

Keywords: Diabetic nephropathy, Advanced glycosylation end-products, N-acetyl beta glucosaminidase, Albuminuria

INTRODUCTION

While hyperglycemia is a strong risk factor for diabetic nephropathy, susceptibility varies among individuals. 1–3 Identifying early markers of susceptibility may help to elucidate the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy and assist in designing new interventions targeted to susceptible individuals.

An early metabolic event in diabetes is the non-enzymatic glycation of proteins, generating advanced glycation end products (AGEs). AGEs are a chemically heterogeneous group of compounds, many of which have intrinsic fluorescence. Fluorescing AGEs in the skin collagen of diabetic subjects from the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) predicted complications occurring years later. 4 AGEs have been associated with diabetic nephropathy, 5, 6 although their role is unclear. Normally, AGE-modified proteins and peptides filtered by the glomerulus are catabolized by the endocytic-lysosomal apparatus of proximal renal tubule cells.7, 8 Therefore, we postulated that AGE-modified protein fragments in the urine might signal early dysfunction of renal tubule cells, and herald clinical nephropathy.9 For this study, pentosidine, a structurally-identified AGE formed by glycoxidative pathways, was selected.10 Urinary pentosidine represents the product of the fragmentation of a long-lived protein crosslink.11, 12 In contrast, urinary AGE fluorescence was chosen as a surrogate for AGE imidazoles, reflecting glycemic control and dicarbonyl stress.5, 13

Albumin excretion rate (AER) was selected as a third urinary marker because of its significance in the pathophysiology of diabetic nephropathy and its potential associations with the other markers under study.14 To examine relationships of AGE excretion and AER with renal tubule dysfunction, urinary excretion of the tubular lysosomal enzyme, N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase (NAG) was chosen as a fourth marker. Urinary NAG is a well-validated marker of proximal tubular cell injury of diverse causes.15–19 Lysosomal dysfunction of the tubule epithelium has been associated with diminished tubular reabsorption of filtered albumin.7 Urinary NAG increases with hyperglycemia 20–22, and decreases with improved glycemia. 23, 24

The primary aim of this study was to investigate the predictive associations of urinary pentosidine, AGE fluorescence, AER, and NAG with microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria in type 1 diabetes. A secondary aim was to explore associations among the urinary markers to better understand potential mechanisms of early renal damage. We used stored urine samples from the DCCT. 2 Measurements of the urinary markers were made twice: at DCCT baseline and at time of first detection of microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria within DCCT follow-up. We controlled for hyperglycemia and blood pressure across time, duration of diabetes, presence of retinopathy, intensity of insulin treatment, creatinine clearance, age, and sex. Since diabetic nephropathy evolves across time, we hypothesized that the change in excretion of a marker across time might enhance its predictive association with outcomes, over and above a single point-in-time value.

METHODS

Participants

Participants were selected from the DCCT using a nested case-control design with a 2:1 control-to-case ratio. The DCCT enrolled individuals with type 1 diabetes mellitus, 13–39 years of age, 1–15 years of diabetes duration, free of advanced micro- or macrovascular complications of diabetes. 2 At DCCT baseline, AER was < 40 mg / 24 hours for the primary prevention cohort (1–5 years of diabetes and no retinopathy), and <200 mg / 24 hours for the secondary intervention cohort (1–15 years of diabetes and at least 1 microaneurysm). HgbA1c and blood pressures were recorded at quarterly visits, while creatinine clearance and AER were assessed annually over nine years of follow-up.

The current case: control study included 322 individuals from the DCCT. A case of microalbuminuria was defined by 1) AER <= 40mg/day at DCCT entry and 2) two consecutive annual measures of AER > 40 but <= 300 mg/day. The year of first occurrence of microalbuminuria is termed the ‘microalbuminuria event’ year. A case of macroalbuminuria is defined by 1) AER < 200 mg/day at DCCT entry and 2) the first annual measure of AER > 300 mg/day. The year of first occurrence of macroalbuminuria is termed the ‘macroalbuminuria event’ year.

Twenty-eight participants developed microalbuminuria, and later developed macroalbuminuria. One case of macroalbuminuria later regressed to microalbuminuria. These individuals are included as cases in both the microalbuminuria and macroalbuminuria sets. Each case was matched to 2 controls free of microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria at the same follow-up year as the case. A prior control was eligible to become a future case. To have required controls to be selected only from non-cases, and to have required participants to be used only once, would have biased the estimates of relative risk. 25 Thus, case or control status was dependent not only on the AER values, but also the time period (year) from study entry.

Four cases of microalbuminuria were able to be matched to only one control: thus, the number of controls for the microalbuminuria set is 178 rather than 182. The number of cases and controls for each study year is shown in Table 1. Matching factors were 1) DCCT primary or secondary cohort, 2) conventional or intensive insulin treatment arm, 3) closest quartile of mean hemoglobinA1c (HbA1c) from DCCT entry until microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria event year, 4) duration of diabetes category. For the primary cohort, duration of diabetes was matched by five categories: 1-< 2 years, 2-<3 years, 3-< 4 years, 4-< 5 years, and 5 or more years. For the secondary cohort, diabetes duration was matched by 1-< 5 years, 5-<8 years, 8-<11 years, 11-< 13 years, and 13-<15 years.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Cases and Controls

| Macroalbuminuria | Microalbuminuria | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases n=55 |

Controls n=110 |

p-value | Cases n=91 |

Controls n=178 |

p-value | |

| MATCHED VARIABLES | ||||||

| DCCT ‘Primary Prevention Cohort’ Number (%) |

9 (16) | 18 (16) | -- | 24 (26) | 48 (27) | .9 |

| DCCT intensive treatment group Number (%) |

18 (33) | 36 (33) | -- | 28 (31) | 54 (30) | .9 |

| Mean ± s.d Duration of DM before DCCT (years) |

8.7 ± .44 | 8.3 ± .34 | .04 | 7.7 ± .42 | 7.6 ± .31 | .4 |

| Mean ± s.d. DCCT HbA1c (%) |

9.4 ± 1.6 | 9.1 ± 1.3 | .006 | 9.2 ± 1.5 | 9.0 ± 1.4 | .06 |

| Mean ± s.d. Time to albuminuria event during DCCT study (years) |

4.3 ± .27 | 4.3 ± .19 | -- | 3.6 ± .19 | 3.6 ± .13 | -- |

| Study Year 1 (No.) | 6 | 12 | 14 | 27 | ||

| Study Year 2 (No.) | 5 | 10 | 12 | 24 | ||

| Study Year 3 (No.) | 8 | 16 | 22 | 44 | ||

| Study Year 4 (No.) | 10 | 20 | 15 | 29 | ||

| Study Year 5 (No.) | 8 | 16 | 14 | 26 | ||

| Study Year 6 (No.) | 11 | 22 | 10 | 20 | ||

| Study Year 7 (No.) | 4 | 8 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Study Year 8 (No.) | 2 | 4 | 3 | 6 | ||

| Study Year 9 (No.) | 1 | 2 | ||||

| UNMATCHED VARIABLES | ||||||

| Males Number (%) | 33 (60) | 52 (47) | .1 | 57 (63) | 95 (53) | .1 |

| Never smokers Number (%) |

39 (71) | 84 (76) | .4 | 65 (71) | 139 (78) | .2 |

| Mean ± s.d.BMI (baseline) | 23 ± 3 | 23 ± 3 | .8 | 23 ± 3 | 24 ± 3 | .3 |

| Mean ± s.d. Age (baseline) (years) |

25 ± 7 | 26 ± 8 | .4 | 24 ± 8 | 26 ± 7 | .03 |

| Mean ± s.d. DCCT Mean Arterial BP (mm Hg) |

91 ± 6 | 88 ± 7 | .01 | 90 ± 6 | 88 ± 6 | .07 |

| Mean ± s.d. HbA1c (baseline) (%) |

10.2 ± 1.5 | 9.4 ± 1.6 | .003 | 9.7 ± 1.7 | 9.4 ± 1.5 | .04 |

| Mean ± s.d. Standardized CCr (baseline) (ml/min/1.73m2) |

129 ± 36 | 132 ± 29 | .6 | 125 ± 28 | 129 ± 26 | .1 |

Four cases of Microalbuminuria were able to be matched with only one instead of two controls.

P-value is from conditional logistic regression. For details, see Statistical Methods.

DCCT HbA1c is calculated from the first quarterly post-baseline HbA1c through the HbA1c at the time of the occurrence of macroalbuminuria or microalbuminuria. Cases and controls were matched to closest quartile of mean DCCT HbA1c, accounting for the imperfect matching on actual mean values.

DCCT Mean Arterial BP includes all quarterly blood pressure values from (and including) baseline through the time of occurrence of macroalbuminuria or microalbuminuria.

MAP is calculated as (diastolic BP) + [(systolic BP − diastolic BP) / 3]

Abbreviations: DM, diabetes mellitus.

Measures of renal function

Methods of urine collection have been described previously. 26 Urine samples were stored at −70 degrees centigrade, without protease inhibitors. Serum creatinine was measured by a variation of the Jaffe method. Urine albumin was measured by fluoro-immunoassay.27 From masked split aliquots, the intra-assay coefficients of variation for urine albumin, urine creatinine, and serum creatinine were 8.4%, 4.7%, and 4.4% respectively, while the coefficients of reliability were 98%, 98%, and 85%. 27

Due to missing or inadequate specimens, some cases and controls are missing baseline or event data of urinary markers. Urinary NAG activity was measured using an enzymatic assay based on a fluorimetric stop rate determination. 28 One unit of activity was the amount of enzyme that hydrolyzed 1.0 micromole of the substrate 4-methylumbelliferyl N-acetyl-b-D-glucosaminide (Sigma, www.sigmaaldrich.com) in one minute. Results are expressed as units of NAG/gram creatinine. A total of 37 assays were performed. The coefficient of variation was 4%.

Urine aliquots were filtered with a 30 KD cut-off membrane (Microcon, Millipore Bioscience, www.millipore.com), excluding intact albumin but allowing free AGEs and low molecular-weight AGE-modified protein fragments to pass into the filtrate. Samples were pretreated with CF-11 cellulose (Whatman, www.whatman.com) in l-butanol, followed by acid hydrolysis. Pentosidine was quantified by HPLC. 29 The detection limit of the assay is 0.375 pmol/ml. Results are expressed as picomoles/milligram urinary creatinine. We have found free pentosidine in urine to remain stable after storage at −80 degrees centigrade for 8 years. The inter-assay coefficient of variation in six assays for pentosidine was 6.32%. Forty-five assays in total were performed: the coefficient of variation was 7%.

AGE fluorescence was measured using a fluorescence spectrophotometer (Jasco, www.jascoinc.com) at 370/440 nm excitation/emission, expressed as fluorescence units/milligram urinary creatinine. 13 Thirty assays were performed for AGE fluorescence: the coefficient of variation was 1%.

Statistical Methods

Predictor variables included the urine marker value measured at baseline, and the change in the marker from baseline to the microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria event year. Natural logarithm transformation was applied to urinary NAG, pentosidine, AGE fluorescence, AER, and creatinine clearance (standardized to body surface area) to reduce the skew. Conditional Logistic Regression 30 was performed in between-group comparisons for quantitative and categorical variables, to incorporate the intra-class correlation among each case:control set. Multivariate Conditional Logistic Regression was used to assess the effect of urinary markers, individually or in combination, on the risk of micro-/macroalbuminuria, with and without adjustment for other risk factors. Adjustor variables included age, sex, baseline HbA1c, HbA1c taken quarterly and averaged from DCCT start to time of micro/ macroalbuminuria event year (DCCT HbA1c), mean arterial blood pressure taken quarterly and averaged from baseline to time of micro/or macroalbuminuria event year (DCCT MAP), baseline creatinine clearance standardized to body surface area, and duration of diabetes. The odds ratio is the ratio of the risk of micro/ macroalbuminuria per 50% increase in the urinary markers unless noted otherwise. Spearman’s rank correlation was used to assess correlations among the urinary markers and HbA1c among the cases. Analyses used SAS (SAS Institute, www.sas.com) software, Version 9.1.

RESULTS

Case:Controls

Ninety-one participants developed microalbuminuria; 55 participants developed macroalbuminuria. Cases and controls were perfectly matched for cohort, treatment group, and DCCT time-to-nephropathy-event (Table 1). DCCT mean HbA1c was slightly higher for cases than controls of macroalbuminuria (9.4% versus 9.1%; p=.006) owing to the fact that cases and controls were matched, for simplicity, within quartiles of HbA1c. Likewise, duration of diabetes was slightly longer in cases of macroalbuminuria compared to controls (104 vs. 100 months; P=.04) because duration was matched to closest category. Cases of microalbuminuria were slightly younger than controls (24 versus 26 years; P=.03). Cases of macroalbuminuria and microalbuminuria each had higher baseline HbA1c than did their respective controls (10.2% versus 9.6%; p=.003) and (9.7% versus 9.4%; p=.04).

AER

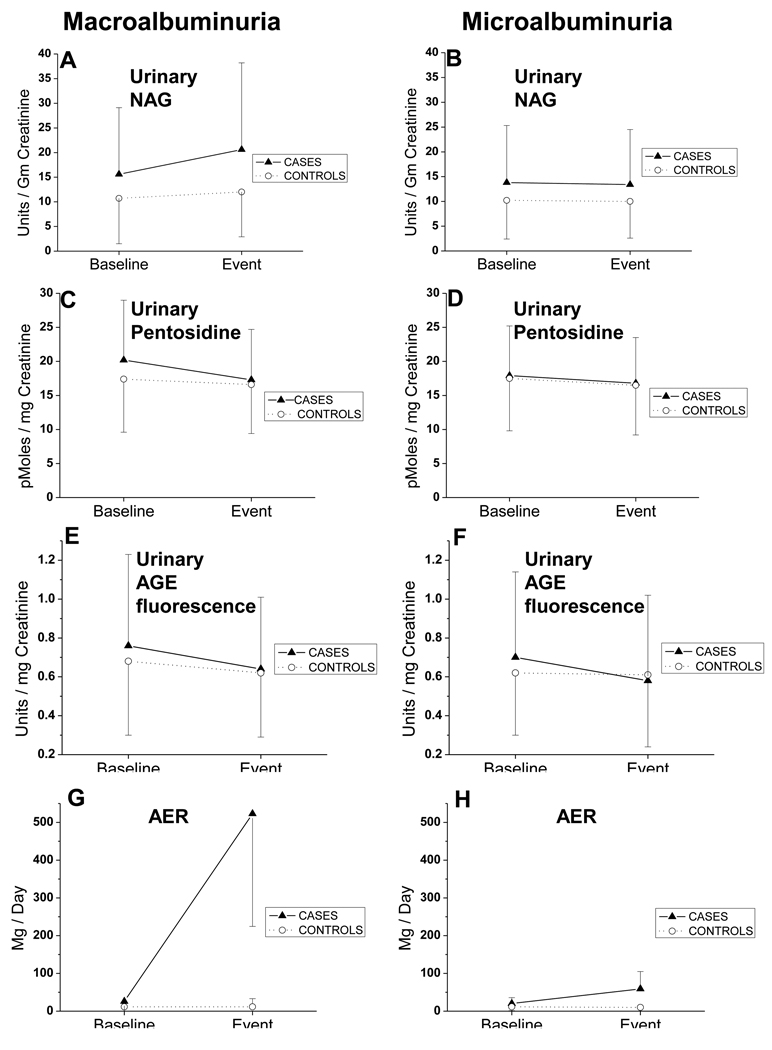

Baseline AER was higher among cases of macroalbuminuria and microalbuminuria than controls (25.9 versus 11.5 mg/day; p <.001) and (20.2 versus 11.5 mg/day; p <.001), respectively. (Table 2, Figure 1) AER predicted macroalbuminuria in the uni-variate model (OR 2.11; CI 1.360–3.28; p <.001) (Table 3) and the fully adjusted model (adjusted OR 1.82; CI 1.36–2.42; p <.001). AER predicted microalbuminuria in the uni-variate model (OR 1.64; CI 1.34–2.00; p <.001) and the fully adjusted model (adjusted OR 1.83; CI 1.36–2.46; p <.001). Thus, the risk for macroalbuminuria and microalbuminuria rose by over 80% for each 50% increase in AER, expressed in mg/day.

Table 2.

Urinary Markers for Macroalbuminuria or Microalbuminuria

| MACROALBUMINURIA | MICROALBUMINURIA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Matched Controls |

P-value | Cases | Matched Controls |

P-value | |

| URINE MARKERS at BASELINE | ||||||

| AER (mg/day) | 25.9 (15.8, 46.1) |

11.5 (7.2, 15.8) |

<.001 | 20.2 (11.5, 27.4) |

11.5 (7.2, 17.3) |

<.001 |

| NAG (U per g creatinine) |

15.6 (8.6, 22.0) |

10.7 (7.1, 16.3) |

.005 | 13.8 (9.2, 20.7) |

10.2 (6.9, 14.7) |

<.001 |

| Pentosidine (pmol/L per mg creatinine) |

20.2 (15.7, 24.5) |

17.4 (14.2, 22.0) |

.02 | 17.9 (15.3, 22.6) |

17.5 (13.5, 21.3) |

.1 |

| AGE fluorescence (U per mg of creatinine) |

0.76 (0.57, 1.05) |

0.68 (0.52, 0.90) |

.2 | 0.70 (0.56, 1.00) |

0.62 (0.52, 0.84) |

.03 |

| URINE MARKERS at FIRST OCCURRENCE* of MACRO OR MICROALBUMINURIA | ||||||

| AER (mg/day) | 522.7 (393.1, 691.2) |

11.5 (7.2, 28.8) |

<.001 | 59.0 (47.5, 93.6) |

10.1 (7.2, 17.3) |

<.001 |

| NAG (U per g creatinine) |

20.6 (13.1, 30.7) |

12.0 (8.5, 17.6) |

<.001 | 13.4 (8.6, 19.7) |

10.0 (6.7, 14.1) |

<.001 |

| Pentosidine (pmol/L per mg creatinine) |

17.3 (13.5, 20.9) |

16.6 (14.0, 21.2) |

.5 | 16.8 (13.3, 20.0) |

16.5 (13.2, 20.5) |

.8 |

| AGE-Fluorescence (U per mg of creatinine) |

0.64 (0.51, 0.88) |

0.62 (0.52, 0.85) |

.9 | 0.58 (0.44, 0.88) |

0.61 (0.48, 0.85) |

.5 |

Note: Values shown are Median (25th, 75th percentile. P-value is from conditional logistic regression. For details, see Statistical Methods.

First occurrence is defined as the time (year) of the annual DCCT study visit when urine samples were routinely collected, and the presence of micro or macroalbuminuria was first documented.

Figure 1.

Each panel on the left (A–D) depicts the change across time, from baseline to the event of macroalbuminuria, for each urinary marker. Each panel on the right (E–H) depicts the change across time, from baseline to the event of microalbuminuria. Values shown are the median, and error bars represent the interquartile range.

Table 3.

Multivariate Models for Individual Urinary Markers

| Urine Marker | Model 1 (Uni-variate) |

Model 2 (Includes baseline and change) |

Model 3 (Fully adjusted) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | aOR | 95% CI | aOR | 95% CI | |

| OUTCOME of MACROALBUMINURIA | ||||||

| Baseline AER | 2.11 *** |

1.36, 3.28 | -- | -- | 1.82 *** |

1.36, 2.42 |

| Baseline NAG | 1.37 ** |

1.10, 1.70 | 2.14 *** |

1.50, 3.07 | 2.26 *** |

1.41, 3.603 |

| Change in NAG | 1.02 | 0.98, 1.06 | 1.07 *** |

1.03, 1.12 | 1.09 ** |

1.03, 1.14 |

| Baseline Pentosidine | 1.63 * |

1.08, 2.47 | 1.76 | 0.99, 3.13 | 6.89 ** |

2.01, 23.66 |

| Change in Pentosidine | 0.97 | 0.93, 1.01 | 1.00 | 0.95, 1.06 | 1.04 | 0.97, 1.13 |

| Baseline AGE fluorescence | 1.25 | 0.91, 1.72 | 1.21 | 0.83, 1.78 | 1.74 | 1.02, 3.00 |

| Change in AGE fluorescence | 0.43 | 0.16, 1.14 | 0.57 | 0.19, 1.74 | 1.25 | 0.28, 5.68 |

| OUTCOME of MICROALBUMINURIA | ||||||

| Baseline AER | 1.64 *** |

1.34, 2.00 | -- | -- | 1.83 *** |

1.36, 2.46 |

| Baseline NAG | 1.35 *** |

1.14, 1.59 | 1.60 *** |

1.27, 2.03 | 1.86 *** |

1.41, 2.46 |

| Change in NAG | 1.00 | 0.98, 1.03 | 1.04 ** |

1.01, 1.07 | 1.07 *** |

1.03, 1.11 |

| Baseline Pentosidine | 1.27 | 0.96, 1.68 | 1.27 | 0.88, 1.81 | 1.24 | 0.81, 1.91 |

| Change in Pentosidine | 0.98 | 0.95, 1.01 | 1.00 | 0.96, 1.04 | 1.01 | 0.96, 1.06 |

| Baseline AGE-Fluorescence |

1.36 * |

1.03, 1.78 | 1.26 | 0.92, 1.72 | 1.42 | 0.99, 2.03 |

| Change in AGE- Fluorescence |

0.49 * |

0.24, 0.98 | 0.65 | 0.30, 1.41 | 0.98 | 0.42, 2.30 |

Model 1 contains only the single variable.

Model 2 contains the baseline variable and the change across time of that variable – with the exception of AER not having a change across time value.

Model 3 is fully adjusted for sex, age, baseline HbA1c, DCCT HbA1c, mean arterial BP from baseline through the time of first recognition of micro or macroalbuminuria, duration of diabetes, and baseline standardized creatinine clearance.

Odds Ratios for the baseline values of the urinary markers represent the odds ratio per 50% increase in raw values.

Odds Ratios for the change in value of the urinary marker represent the odds ratio per 1 unit increase in raw values.

p<.05

P<.01

P<.001

Abbreviation: aOR, adjusted Odds Ratio

AER remained an independent predictor for macroalbuminuria as well as microalbuminuria (Table 4,Table 5) when its effect was adjusted for other urinary markers, individually or in combination.

Table 4.

Multivariate Models for Macroalbuminuria Outcome Adjusted for Combined Urinary Markers

| + AER, adjustors |

+ NAG, adjustors |

+ Pentosidine, adjustors |

+ AGE fluorescence, adjustors |

+ AER, NAG,ΔNAG, pentosidine, Δpentosidine, AGE-fluorescence, ΔAGE fluorescence, adjustors |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urine Marker (Predictor) |

aOR 95% CI |

aOR 95% CI |

aOR 95% CI |

aOR 95% CI |

aOR 95% CI |

| Baseline AER | -- | 2.11 1.36, 3.28 *** |

1.78 1.26, 2.51 ** |

1.79 1.31, 2.46 *** |

2.31 1.32, 4.05 ** |

| Baseline NAG | 2.32 1.16, 4.36 * |

-- | 1.79 1.04, 3.09 * |

2.92 1.51, 5.64 ** |

2.60 0.83, 8.11 |

| Change in NAG | 1.14 1.05, 1.24 ** |

-- | 1.08 1.02, 1.15 * |

1.14 1.05, 1.23 ** |

1.20 1.05, 1.37 ** |

| Baseline Pentosidine |

7.02 1.70, 29.03 ** |

2.99 0.77, 11.62 |

-- | 7.00 1.92, 25.52 ** |

2.72 0.35, 20.81 |

| Change in Pentosidine |

1.05 0.96, 1.16 |

1.00 0.91, 1.10 |

-- | 1.06 0.97, 1.15 |

1.01 0.87, 1.18 |

| Baseline AGE- Fluorescence |

1.80 0.96, 3.38 |

1.14 0.56, 2.31 |

1.54 0.84, 2.83 |

-- | 1.70 0.65, 4.41 |

| Change in AGE- Fluorescence |

1.97 0.36, 10.65 |

0.12 0.02, 0.99* |

0.92 0.18, 4.56 |

-- | 0.26 0.02, 3.90 |

Urine markers in the left-hand column were adjusted for the urine markers in the column headings.

Adjustor variables are sex, age, baseline HbA1c, mean DCCT HbA1c, mean arterial BP from baseline through the time of first recognition of macroalbuminuria, duration of diabetes, and baseline standardized creatinine clearance.

p< .05

P<.01

p< .001

Table 5.

Multivariate Models for Microalbuminuria Outcome Adjusted for Combined Urinary Markers

| + AER, adjustors |

+ NAG, adjustors |

+ Pentosidine, adjustors |

+ AGE fluorescence, adjustors |

+ AER, NAG,ΔNAG, pentosidine, Δpentosidine, AGE-fluorescence, ΔAGE fluorescence, adjustors |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urinary Marker (Predictor) |

aOR 95% CIe |

aOR 95% CI |

aOR 95% CI |

aOR 95% CI |

aOR 95% CI |

| Baseline AER | -- | 1.61 1.26, 2.07 *** |

1.61 1.29, 2.02 *** |

1.69 1.33, 2.15 *** |

1.83 1.36, 2.46 *** |

| Baseline NAG | 1.82 1.33, 2.49 *** |

-- | 1.87 1.40, 2.49 *** |

1.92 1.42, 2.61 *** |

1.90 1.34, 2.68 *** |

| Change in NAG | 1.08 1.04, 1.13 *** |

-- | 1.07 1.03, 1.11 *** |

1.07 1.03, 1.12 *** |

1.10 1.04, 1.15 *** |

| Baseline Pentosidine |

1.25 0.78, 1.98 |

1.85 0.65, 1.71 |

-- | 1.17 0.71, 1.92 |

0.96 0.51, 1.83 |

| Change in Pentosidine |

1.03 0.97, 1.08 |

0.99 0.93, 1.05 |

-- | 1.01 0.96, 1.07 |

1.01 0.94, 1.09 |

| Baseline AGE- Fluorescence |

1.68 1.09, 2.60 * |

1.16 0.79, 1.71 |

1.36 0.92, 2.00 |

-- | 1.61 0.97, 2.66 |

| Change in AGE- Fluorescence |

0.82 0.32, 2.09 |

0.51 0.20, 1.28 |

0.77 0.31, 1.95 |

-- | 0.48 0.16, 1.44 |

Urine markers in the left-hand column were adjusted for the urine markers in the column headings.

Adjustor variables are Age, Sex, Baseline HbA1c, DCCT HbA1c, DCCT mean arterial blood pressure, Duration of diabetes, Baseline standardized creatinine clearance. For details see Methods.

p< .05

P<.01

p< .001

NAG

Baseline urinary NAG was higher among cases than controls of macroalbuminuria (15.6 versus 10.7 units/gram creatinine; p=.005), and higher among cases than controls of microalbuminuria (13.8 versus 10.2 units/gram creatinine; p<.001) (Table 2, Figure 1)

In uni-variate analysis, NAG predicted macroalbuminuria (OR 1.37; CI 1.10–1.70; p=.005) (Table 3). Baseline NAG, adjusted for the change in NAG, strengthened its association with macroalbuminuria (adjusted OR 2.14; CI 1.50–3.07; p<.001). The change in NAG independently predicted macroalbuminuria when adjusted for baseline NAG (adjusted OR 1.07; CI 1.03, 1.12; p<.001). When fully adjusted for all covariates, baseline NAG (adjusted OR 2.26; CI 1.41, 3.60; p<.001) and change in NAG (adjusted OR 1.09; CI 1.03, 1.14; p=.002) predicted macroalbuminuria. Thus, the risk for macroalbuminuria rose more than two-fold for every 50% increase in urine NAG at baseline, and additionally rose almost 9% for every unit increase in urine NAG across the time interval from baseline to the occurrence of macroalbuminuria.

In uni-variate analysis, baseline NAG predicted microalbuminuria (OR 1.35; CI 1.14, 1.59; p<.001). (Table 3) Adjusted for the change in NAG, baseline NAG slightly strengthened its association with microalbuminuria (adjusted OR 1.60; CI 1.27–2.03; p <.001). When fully adjusted, baseline NAG remained independently associated with future microalbuminuria (adjusted OR= 1.86; CI 1.41–2.46; p<.001), as did change in NAG (adjusted OR 1.07; CI 1.03–1.11; p <.001). Thus, the risk for microalbuminuria rose more than 80% for every 50% increase in urine NAG at baseline, and additionally rose almost 7% for every unit increase in urine NAG across the time interval from baseline to the occurrence of microalbuminuria.

Baseline NAG independently predicted macroalbuminuria (Table 4) when adjusted for other urinary markers, but lost significance when all four markers were combined in the same model. However, the change in NAG remained an independent predictor for macroalbuminuria regardless of adjustment by other urinary markers, individually or in combination. Baseline NAG remained an independent predictor for microalbuminuria (Table 5) when adjusted for other urinary markers, individually or in combination. The change in NAG independently predicted microalbuminuria regardless of adjustment by other urinary markers, individually or in combination.

Among cases of macro/ and microalbuminuria, baseline NAG excretion correlated with baseline HbA1c (r=.48; p<.001) and (r=.35; p=.0006), respectively, while the change in NAG correlated with the difference between baseline HbA1c and mean DCCT HbA1c (r= .30; p=.03) and (r= .34; p=.001), respectively.

Pentosidine

Median urinary pentosidine among cases of macroalbuminuria was higher than controls (20.2 versus 17.4 pM/mg creatinine; p=.02) but did not differ between cases and controls of microalbuminuria (17.9 versus 17.5 pM/mg creatinine; p=.1). (Table 2, Figure 1) Baseline urinary pentosidine predicted macroalbuminuria (OR 1.64; CI 1.08–2.47; p=.02). (Table 3) Adjusted for change in pentosidine across time, plus all adjustor covariates, baseline pentosidine strongly and significantly predicted macroalbuminuria (adjusted OR 6.89; CI 2.01, 23.66; p=.002). Thus, the risk for macroalbuminuria rose almost seven-fold for every 50% increase in urinary free and low-molecular-weight pentosidine, expressed as pmoles/mg urine creatinine. In contrast, urinary pentosidine had no association with microalbuminuria. (Table 3, 5)

Baseline pentosidine remained an independent predictor for macroalbuminuria (Table 4) adjusted for urinary AGE fluorescence (adjusted OR 7.00; CI 1.92, 25.52; p=.003), but the association decreased and lost significance when pentosidine was adjusted for NAG, either individually or in combination with the other urine markers.

Among cases of macroalbuminuria, baseline urinary pentosidine did not correlate with baseline HbA1c (r=.06; p=.7). The change in pentosidine correlated weakly with mean DCCT HbA1c (r=.28; p=.05).

AGE Fluorescence

Baseline urinary AGE fluorescence among future cases of macroalbuminuria was not significantly different from controls (0.76 versus 0.68 Units/mg creatinine; p=.2) (Table 2, Figure 1). However, baseline urinary AGE fluorescence was greater among future cases of microalbuminuria than controls (0.70 versus 0.62 Units/mg creatinine; p=.03).

Baseline AGE-fluorescence was not associated with future macroalbuminuria (Table 3). However, baseline AGE fluorescence and the change across time of AGE fluorescence were each individually associated with microalbuminuria (OR 1.36; CI 1.03, 1.78; p=.03) and (OR 0.49; CI 0.24, 0.98; p=.03), respectively. These associations lost significance when adjusted for each other, or other adjustor covariates were entered into the regression model. Further adjustment for baseline AER (Table 5) resulted in a statistically significant association of baseline AGE-fluorescence with microalbuminuria (adjusted OR 1.68; CI 1.09, 2.60; p= .02). The addition of NAG or pentosidine into the model weakened the association of baseline AGE-fluorescence with microalbuminuria.

Among cases of macroalbuminuria, baseline urinary AGE fluorescence did not correlate with baseline HbA1c (r=.07; p=.6), nor did the change in urinary AGE fluorescence correlate with mean DCCT HbA1c (r=.20; p=.2).

DISCUSSION

We examined four putative markers of susceptibility to future diabetic nephropathy. The markers were selected to possibly reflect early tubular injury, which is thought to be an early event in the pathophysiology of clinical diabetic nephropathy.

We hypothesized that sub-microalbuminuric values of AER may distinguish individuals at risk to develop clinical diabetic nephropathy by indicating early tubular injury.6 A fraction of serum albumin is normally filtered through the glomerulus, but is completely reabsorbed by the cells of the proximal tubule. 31 Damage to tubular cells or interstitium may cause increased AER by impairing endocytosis, degradation, or transport of albumin and its degradation products. 32

We found that sub-microalbuminuric levels of AER (20 to 26 mg/day) were strongly associated with future microalbuminuria and macroalbuminuria. Such levels of AER are within the range consistent with a lack of reabsorption by the proximal tubule. 8Tubular processing of proteins that normally pass the glomerular filter is disrupted in experimental diabetes, 33, 34 and a recent study demonstrated that albuminuria induced by experimental diabetes is due to changes in proximal tubule handling of filtered albumin in the hyperglycemic state.8 However, increased AER can indicate impaired glomerular sieving as well as impaired tubular reabsorption. 35, 36 Our finding that sub-microalbuminuric AER predicted micro/macroalbuminuria after adjustment for urinary NAG, a known marker for tubular injury, suggests that early AER may be independent of tubular damage.

Urinary NAG is a well-studied marker specific for renal tubular injury. 37, 38 We found that baseline excretion of NAG, and rising NAG excretion across time, predict both microalbuminuria and macroalbuminuria. These results support the idea that early NAG excretion may be a marker of susceptibility to diabetic nephropathy, and suggest that early tubular dysfunction/injury that persists and accelerates characterizes individuals destined to develop diabetic nephropathy. In practical application for the individual patient, NAG excretion that continues to rise despite stable or improving glycemia may indicate high risk of future nephropathy, and prove to be more reliable than an absolute value of urinary NAG at a single point in time.

NAG excretion correlates with hyperglycemia in diabetes. 20, 39–41 Therefore it is critical to exclude hyperglycemia as a confounder for the association of NAG with future micro/macroalbuminuria. We controlled for exposure to hyperglycemia across time. Controls were matched to cases by 1) the closest quartile of time-averaged DCCT HbA1c, 2) DCCT treatment arm (intensive versus conventional insulin therapy), and 3) follow-up time to the year in which microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria first developed/ or not. We made further statistical adjustment for HbA1c in the multivariate models. We believe that the study design and analytic approach allow us to make a reasonable assumption that our findings are not simply the consequence of worse diabetes regulation, although this possibility cannot be excluded with absolute certainty.

We found baseline urinary NAG to be modestly correlated with baseline hyperglycemia among future cases of macroalbuminuria or microalbuminuria. Taken overall, our results support the interpretation that, although NAG excretion is, to some degree, associated with hyperglycemia, a glycemia-independent component of NAG excretion marks individuals susceptible to rapid progression to either microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria. Kordonouri, et al. reached a similar conclusion in a study of incident microalbuminuria among young patients with type 1 diabetes. 21 Our study extends this interpretation to include urinary NAG as a predictor of macroalbuminuria. Others have concluded that NAG excretion in diabetes fails to distinguish those who will develop microalbuminuria from those who will not. 42, 43 The differing conclusions may lie in our treatment of urinary NAG as a continuous rather than a dichotomous variable, and our control of multiple risk factors known to influence development of microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria.

Controlling for baseline AER did not confound the association of urinary NAG with macroalbuminuria or microalbuminuria. The independence of the two markers from hyperglycemia, and from each other, suggests that simultaneous measurement of AER and urinary NAG early in diabetes may identify individuals with high risk of future nephropathy.

A role for AGEs in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy is supported by previous observations 4, 29 and by recent data showing that exposure to AGE-modified albumin results in abnormal processing of unmodified albumin by cultured renal tubular cells. 6 We found urinary pentosidine, free and bound to low molecular weight proteins, was significantly and strongly associated with macroalbuminuria, controlling for hyperglycemia, diabetes duration, sex, age, creatinine clearance, and blood pressure. Our findings extend those of a prior study-- in which urinary free pentosidine predicted more rapid loss of GFR in advanced diabetic nephropathy 29--to include increased pentosidine excretion as an early marker predictive of macroalbuminuria. The confounding of the association of pentosidine with macroalbuminuria by NAG, but not by AER or AGE fluorescence, suggests that urinary pentosidine excretion-- in its free form and bound to low molecular weight proteins-- may be an indicator of early tubular damage.

In contrast to pentosidine, AGE fluorescence of low-molecular weight urinary proteins was significantly associated with future microalbuminuria, but not macroalbuminuria. The lack of statistical significance with macroalbuminuria may have been due to the smaller number of cases of macroalbuminuria, since odds ratios were similar for both outcomes. Like pentosidine, AGE fluorescence was confounded by NAG in its association with microalbuminuria, suggesting that AGE fluorescence may indicate early tubular damage.

Our study is limited in that urinary markers were measured at only two time points-- from an arbitrary baseline, to the time when micro/ or macroalbuminuria was first recognized. If the changes in urine NAG across time are non-linear, odds ratios for the association with micro/macroalbuminuria may over or under-estimate the relationships. We lacked participant-level information on use of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors. 24, 44 The DCCT discouraged use of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors during the trial period, prior to evidence that these agents modified the risk of nephropathy. 45 Thus, our results may not generalize to patients treated with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors.

In conclusion, early urinary elevations of albumin and NAG in type 1 diabetes, coupled with rising NAG, independently herald future microalbuminuria and macroalbuminuria. Combining AER and NAG in repeated measures may help to identify individuals susceptible to diabetic nephropathy. Urinary excretion of free and low molecular weight pentosidine may predict macroalbuminuria, while urinary excretion of AGE fluorescence may predict microalbuminuria. Renal tubule stress may be more severe, reflecting abnormal renal tubule processing of AGE-modified proteins among individuals with type 1 diabetes susceptible to develop diabetic nephropathy. These data provide clinical evidence in support of the hypothesis that tubular stress, along with abnormal glomerular sieving, contributes to the pathophysiology of diabetic nephropathy.46, 47

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank David Kenny of the DCCT Data Coordinating Center at the Biostatistics Center of George Washington University for his help in designing the case-control study and identifying the cases and their controls from the DCCT data base, and the Data Coordinating Center for making available the urine samples and associated demographic and biochemical data..

Support This work was supported under cooperative agreements and a research contract with the Division of Diabetes, Endocrinology, and Metabolic Diseases of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, by Department of Health and Human Services grants P01DK57733, DK57733 and DK45619 (M.F.W.), by the Frontier Research Division of Taisho Pharmaceutical Company (Saitama Japan), and by the Leonard B. Rosenberg Renal Research Foundation of the Center for Dialysis Care (Cleveland, OH).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Krolewski M, Eggers PW, Warram JH. Magnitude of end-stage renal disease in IDDM: a 35 year follow-up study. Kidney Int. 1996 Dec;50(6):2041–2046. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(14):977–986. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. Clustering of long-term complications in families with diabetes in the diabetes control and complications trial. Diabetes. 1997 Nov;46(11):1829–1839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Genuth S, Sun W, Cleary P, et al. Glycation and carboxymethyllysine levels in skin collagen predict the risk of future 10-year progression of diabetic retinopathy and nephropathy in the diabetes control and complications trial and epidemiology of diabetes interventions and complications participants with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2005 Nov;54(11):3103–3111. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.11.3103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beisswenger PJ, Drummond KS, Nelson RG, Howell SK, Szwergold BS, Mauer M. Susceptibility to diabetic nephropathy is related to dicarbonyl and oxidative stress. Diabetes. 2005 Nov;54(11):3274–3281. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.11.3274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ozdemir AM, Hopfer U, Rosca MV, Fan XJ, Monnier VM, Weiss MF. Effects of advanced glycation end product modification on proximal tubule epithelial cell processing of albumin. Am J Nephrol. 2008;28(1):14–24. doi: 10.1159/000108757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osicka TM, Houlihan CA, Chan JG, Jerums G, Comper WD. Albuminuria in patients with type 1 diabetes is directly linked to changes in the lysosome-mediated degradation of albumin during renal passage. Diabetes. 2000 Sep;49(9):1579–1584. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.9.1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Russo LM, Sandoval RM, Campos SB, Molitoris BA, Comper WD, Brown D. Impaired tubular uptake explains albuminuria in early diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009 Mar;20(3):489–494. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008050503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saito A, Takeda T, Sato K, et al. Significance of proximal tubular metabolism of advanced glycation end products in kidney diseases. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005 Jun;1043:637–643. doi: 10.1196/annals.1333.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Odetti PFJ, Sell DR, Monnier VM. Chromatographic quantification of plasma and erythrocyte pentosidine in diabetic and uremic subjects. Diabetes. 1992;41(2):153–159. doi: 10.2337/diab.41.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gugliucci A, Bendayan M. Renal fate of circulating advanced glycated end products (AGE): evidence for reabsorption and catabolism of AGE-peptides by renal proximal tubular cells. Diabetologia. 1996 Feb;39(2):149–160. doi: 10.1007/BF00403957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Londono I, Bendayan M. Glomerular handling of native albumin in the presence of circulating modified albumins by the normal rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005 Dec;289(6):F1201–F1209. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00027.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yanagisawa K, Makita Z, Shiroshita K, et al. Specific fluorescence assay for advanced glycation end products in blood and urine of diabetic patients. Metabolism. 1998 Nov;47(11):1348–1353. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(98)90303-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kowluru A, Kowluru R, Bitensky MW, Corwin EJ, Solomon SS, Johnson JD. Suggested mechanism for the selective excretion of glucosylated albumin. The effects of diabetes mellitus and aging on this process and the origins of diabetic microalbuminuria. J Exp Med. 1987 Nov 1;166(5):1259–1279. doi: 10.1084/jem.166.5.1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bosomworth MP, Aparicio SR, Hay AW. Urine N-acetyl-beta-D-glucosaminidase--a marker of tubular damage? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999 Mar;14(3):620–626. doi: 10.1093/ndt/14.3.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ellis EN, Brouhard BH, LaGrone L. Urinary N-acetyl-beta-D-glucosaminidase in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Biochem Med. 1984 Jun;31(3):303–310. doi: 10.1016/0006-2944(84)90086-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guder WG, Hofmann W. Markers for the diagnosis and monitoring of renal tubular lesions. Clin Nephrol. 1992;38 Suppl 1:S3–S7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hong CY, Chia KS. Markers of diabetic nephropathy. J Diabetes Complications. 1998 Jan-Feb;12(1):43–60. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8727(97)00045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watts GF, Vlitos MA, Morris RW, Price RG. Urinary N-acetyl-beta-D-glucosaminidase excretion in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: relation to microalbuminuria, retinopathy and glycaemic control. Diabete Metab. 1988 Sep-Oct;14(5):653–658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsiao PH, Tsai WS, Tsai WY, Lee JS, Tsau YK, Chen CH. Urinary N-acetyl-beta-D-glucosaminidase activity in children with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Am J Nephrol. 1996;16(4):300–303. doi: 10.1159/000169013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kordonouri O, Hartmann R, Muller C, Danne T, Weber B. Predictive value of tubular markers for the development of microalbuminuria in adolescents with diabetes. Horm Res. 1998;50 Suppl 1:23–27. doi: 10.1159/000053098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mocan Z, Erem C, Yildirim M, Telatar M, Deger O. Urinary beta 2-microglobulin levels and urinary N-acetyl-beta-D-glucosaminidase enzyme activities in early diagnosis of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus nephropathy. Diabetes Res. 1994;26(3):101–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamanouchi T, Kawasaki T, Yoshimura T, et al. Relationship between serum 1,5-anhydroglucitol and urinary excretion of N-acetylglucosaminidase and albumin determined at onset of NIDDM with 3-year follow-up. Diabetes Care. 1998 Apr;21(4):619–624. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.4.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Basturk T, Altuntas Y, Kurklu A, Aydin L, Eren N, Unsal A. Urinary N-acetyl B glucosaminidase as an earlier marker of diabetic nephropathy and influence of low-dose perindopril/indapamide combination. Ren Fail. 2006;28(2):125–128. doi: 10.1080/08860220500530510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lubin JH, Gail MH. Biased selection of controls for case-control analyses of cohort studies. Biometrics. 1984 Mar;40(1):63–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. Effect of intensive therapy on the development and progression of diabetic nephropathy in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. Kidney Int. 1995 Jun;47(6):1703–1720. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Molitch ME, Steffes MW, Cleary PA, Nathan DM. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. Baseline analysis of renal function in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. [corrected] Kidney Int. 1993 Mar;43(3):668–674. doi: 10.1038/ki.1993.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noto A, Ogawa Y, Mori S, et al. Simple, rapid spectrophotometry of urinary N-acetyl-beta-D-glucosaminidase, with use of a new chromogenic substrate. Clin Chem. 1983 Oct;29(10):1713–1716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weiss MF, Rodby RA, Justice AC, Hricik DE Collaborative Study Group. Free pentosidine and neopterin as markers of progression rate in diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int. 1998 Jul;54(1):193–202. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.4495352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.SAS Help and Documentation Example 54.3: Conditional Logistic Regression for m:n Matching. [Accessed March 20, 2007]; [Google Scholar]

- 31.Birn H, Christensen EI. Renal albumin absorption in physiology and pathology. Kidney Int. 2006 Feb;69(3):440–449. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.D'Amico G, Bazzi C. Pathophysiology of proteinuria. Kidney Int. 2003 Mar;63(3):809–825. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Layton GJ, Jerums G. Effect of glycation of albumin on its renal clearance in normal and diabetic rats. Kidney Int. 1988 Mar;33(3):673–676. doi: 10.1038/ki.1988.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Osicka TM, Forbes JM, Thallas V, Brammar GC, Jerums G, Comper WD. Ramipril prevents microtubular changes in proximal tubules from streptozotocin diabetic rats. Nephrology (Carlton) 2003 Aug;8(4):205–211. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1797.2003.00159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deckert T, Kofoed-Enevoldsen A, Vidal P, Norgaard K, Andreasen HB, Feldt-Rasmussen B. Size- and charge selectivity of glomerular filtration in Type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetic patients with and without albuminuria. Diabetologia. 1993 Mar;36(3):244–251. doi: 10.1007/BF00399958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scandling JD, Myers BD. Glomerular size-selectivity and microalbuminuria in early diabetic glomerular disease. Kidney Int. 1992 Apr;41(4):840–846. doi: 10.1038/ki.1992.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Etherington C, Bosomworth M, Clifton I, Peckham DG, Conway SP. Measurement of urinary N-acetyl-b-D-glucosaminidase in adult patients with cystic fibrosis: before, during and after treatment with intravenous antibiotics. J Cyst Fibros. 2007 Jan;6(1):67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu Y, Liu J, Habeebu SS, Klaassen CD. Metallothionein protects against the nephrotoxicity produced by chronic CdMT exposure. Toxicol Sci. 1999 Aug;50(2):221–227. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/50.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) IX: Relationships of urinary albumin and N-acetylglucosaminidase to glycaemia and hypertension at diagnosis of type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus and after 3 months diet therapy. Diabetologia. 1993 Sep;36(9):835–842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Agardh CD, Agardh E, Isaksson A, Hultberg B. Association between urinary N-acetyl-beta-glucosaminidase and its isoenzyme patterns and microangiopathy in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Clin Chem. 1991 Oct;37(10 Pt 1):1696–1699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patrick AW, Oliver MD, Howie AF, Dawes J, Macintyre CC, Frier BM. Urinary excretion of beta-thromboglobulin and N-acetyl-beta-D-glucosaminidase in type 1 diabetes: potential indicators of early nephropathy? Diabete Metab. 1990 Sep-Oct;16(5):441–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schultz CJ, Dalton RN, Neil HA, Konopelska-Bahu T, Dunger DB. Markers of renal tubular dysfunction measured annually do not predict risk of microalbuminuria in the first few years after diagnosis of Type I diabetes. Diabetologia. 2001 Feb;44(2):224–229. doi: 10.1007/s001250051603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Agardh CD, Tallroth G, Hultberg B. Urinary N-acetyl-beta-D-glucosaminidase activity does not predict development of diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes Care. 1987 Sep-Oct;10(5):604–606. doi: 10.2337/diacare.10.5.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Remuzzi A, Perico N, Amuchastegui CS, et al. Short- and long-term effect of angiotensin II receptor blockade in rats with experimental diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1993 Jul;4(1):40–49. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V4140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Bain RP, Rohde RD The Collaborative Study Group. The effect of angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibition on diabetic nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 1993 Nov 11;329(20):1456–1462. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199311113292004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thomson SC, Vallon V, Blantz RC. Kidney function in early diabetes: the tubular hypothesis of glomerular filtration. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004 Jan;286(1):F8–F15. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00208.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tucker BJ, Rasch R, Blantz RC. Glomerular filtration and tubular reabsorption of albumin in preproteinuric and proteinuric diabetic rats. J Clin Invest. 1993 Aug;92(2):686–694. doi: 10.1172/JCI116638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]