Abstract

Background:

A lumbar pedicular dynamic stabilization system (LPDSS) is an alternative to fusion for treatment of degenerative disc disease (DDD). In this study, clinical and radiological results of one LPDSS (Saphinaz, Medikon AS, Turkey) were compared with results of rigid fixation after two-year follow-up.

Methods:

All patients had anteroposterior and lateral standing x-rays of the lumbar spine preoperatively and at 3 months, 12 months and 24 months after surgery. Lordosis of the lumbar spine, segmental lordosis and ratio of the height of the intervertebral disc spaces (IVS) measured preoperatively and at 3 months, 12 months and 24 months after surgery.

All patients underwent MRI and/or CT preoperatively, 3months, 12 months and 24 months postoperatively. The ratio of intervertebral disc space to vertebral body height (IVS) and segmental and lumbar lordosis were evaluated preoperatively and postoperatively. Pain scores were evaluated via Visual Analog Scale (VAS) and Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) preoperatively and postoperatively.

Results:

In both groups, the VAS and ODI scores decreased significantly from preoperatively to postoperatively. There was no difference in the scores between groups except that a lower VAS and ODI scores were observed after 3 months in the LPDSS group. In both groups, the IVS ratio remained unchanged between preoperative and postoperative conditions. The lumbar and segmental lordotic angles decreased insignificantly to preoperative levels in the months following surgery.

Conclusions:

Patients with LPDSS had equivalent relief of pain and maintenance of sagittal balance to patients with standard rigid screw-rod fixation. LPDSS appears to be a good alternative to rigid fixation.

Keywords: Degenerative disc disease, dynamic stabilization, lumbar spine, rigid stabilization.

INTRODUCTION

After the Second World War, especially for the last two decades, lumbar degenerative disc disease (LDDD) has become a chronic health problem because of the aging population. Chronic low back pain is the major finding of LDDD in the aging spine. Generally, low back pain may originate from the vertebral endplates, disc annulus, vertebral periosteum, facet joints, and soft tissues [1]. As a conventional surgical treatment, fusion was the first choice for chronic low back pain for many years. However, the clinical outcome of fusion has been shown to be worse than the radiological outcome [2]. Many patients have failed to improve after successful spinal fusion [3]. Additionally, fusion may accelerate degeneration of adjacent segments, making alternative treatments attractive [4].

The primary mechanism of chronic low back pain is theorized to be abnormal load distribution across the disc space following disc degeneration [5]. Lack of relief of low back pain postoperatively may be a result of failure to rectify abnormal load transmission patterns in the disc space [6]. Controlled movement among the elements of an implant and increased load transfer through the stabilized segments may be essential to avoid the adverse effects of rigid implants on the stabilized and adjacent levels and to prevent implant failure. The ideal system should permit controlled motion and increased load sharing without sacrificing construct stability. Especially over the last 10 years, the interest of spine surgeons in dynamic stabilization procedures has increased. Recently, various posterior lumbar pedicular dynamic stabilization systems (LPDSS) have become an alternative to fusion for the treatment of degenerative problems in the lumbar spine. The goals of dynamic stabilization are to unload the disc/facet joints, preserve motion under mechanical load, and restrict abnormal motion in the spinal segment [6].

The purpose of this study is to review the clinical and radiological results of a particular LPDSS (Saphinaz, Medikon AS , Turkey, Fig. 1) after two years follow-up and to compare clinical outcomes using this system to those in patients receiving rigid hardware systems.

Fig. (1).

Dynamic (hinged) pedicle screw (Saphinaz, Medikon AS, Turkey). The screw is free to pivot primerly in one plane and is oriented so that the hinge is perpendicular to the sagittal plane and to the rod interconnecting screw heads at adjacent levels.

MATERIALS AND METHODOLOGY

A total of 41 DDD patients were selected for this study. 19 patients were stabilized with LPDSS and the remaining 22 patients were stabilized with rigid systems. The patients were informed about different surgical treatment methods. Both surgical techniques and postoperative courses were explained to the patients. The decision on which surgical method would be applied was based on the patient preference. Patients with disc degeneration with degenerative spondylolisthesis, failed nucleoplasty, and recurrent disc herniation were excluded from the study. Operation time, blood loss during surgery, and duration of hospital stay of the two groups were also collected.

Patient Population for LPDSS Group

19 LDDD adult patients comprised the LPDSS group. There were 5 men and 14 women, with mean age 57.4 years (range 17-80 years). The mean weight of patients was 69.5 kg (range 56-88 kg). 9 of the 19 patients were cigarette smokers. All of the patients were stabilized at 1 lumbar level.

Patient Population for Rigid Stabilization Group

22 LDDD adult patients comprised the rigid stabilization group. There were 10 men and 12 women, with mean age 54.5 years (range 20-86 years). The mean weight of patients was 68.8kg (range 46-90 kg). 6 of these 22 patients were cigarette smokers. All patients were stabilized at one lumbar level.

Evaluation of Quality and Pain Scores

The quality of life and pain scores of the LPDSS and rigid stabilized groups were evaluated via Visual Analog Scale (VAS) and Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) preoperatively and at 3 12 and 24 months after surgery. The VAS and ODI of both groups were compared at all time intervals.

Radiological Analysis

The patients of both groups underwent preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and/or computed tomography (CT). Furthermore, all patients had anteroposterior and lateral standing x-rays of the lumbar spine preoperatively and at 3 months, 12 months and 24 months after surgery. Lordosis of the lumbar spine (L1-S1) was measured as the angle between the lines drawn on lateral standing X-Rays from the lower endplate of L1 and upper endplate of S1. Segmental lordosis of the operative level (or levels) was measured as the angle between lines drawn from the upper and lower endplates of the vertebrae across which instrumentation spanned preoperatively and at, 3 months, 12 months and 24 months after surgery. The ratio of the height of the intervertebral disc spaces (IVS) to the vertebral body height was measured and compared preoperatively and postoperatively. IVS ratio was calculated as the mean anterior and posterior intervertebral disc height divided by the vertebral height of the rostral vertebra of the motion segment.

Surgical Procedure

All operations were performed under general anesthesia in knee-chest position to maintain lordosis of lumbar vertebrae. The surgical approach was along the median line, opening the lumbar aponeurosis, and rasping the paravertebral muscles through the facet joints. Facet joints and ligaments were preserved from iatrogenic damage during exposure in the LPDSS group; facet joints were decorticated to promote fusion in the rigidly stabilized group. Hemilaminectomy, laminectomy and/or discectomy were performed according to the indications of each patient before pedicle screw insertion. Dynamic screws and rigid screws were placed under fluoroscopic visualization.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Mann Whitney U and T-test. Clinical and radiological parameters were statistically compared between groups. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

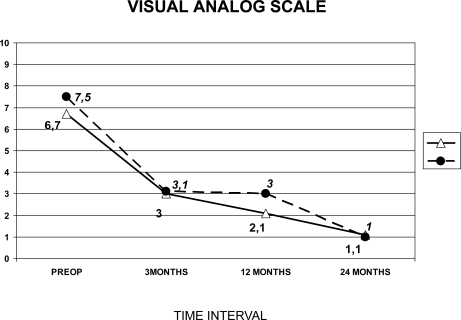

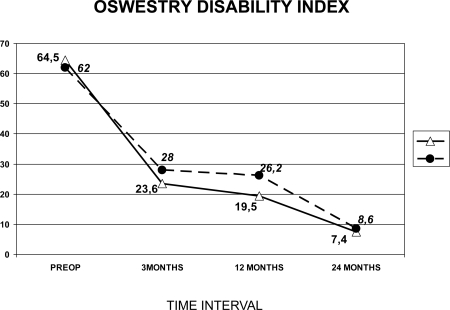

Preoperatively, the mean VAS pain score was greater in the rigidly stabilized group than in the LPDSS group, significantly (p = 0.045, Fig. 2). The ODI score was greater in the LPDSS group than in the rigidly stabilized group, although not significantly (p = 0.111, Fig. 3). The mean preoperative IVS ratio was significantly greater in the rigidly stabilized group than in the LPDSS group (p = 0.03, Table 1). The mean preoperative angles of lumbar lordosis and segmental lordosis were not significantly different between rigidly stabilized and LPDSS subjects (p > 0.18, Table 2).

Fig. (2).

Comparison in outcomes of Visual Analog Scale (VAS) scores between rigidly stabilized patients and patients receiving LPDSS at three time points. Both groups exhibited significant reduction in pain over time.

Fig. (3).

Comparison in outcomes of Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) scores between rigidly stabilized patients and patients receiving LPDSS at three time points.

Table 1.

Mean Intervertebral Space Ratio (IVS) ± Standard Deviation for LPDSS and Rigidly Stabilized Groups

| Group | Preoperative | Postoperative (3 Months) | Postoperative (12 Months) | Postoperative (24 Months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LPDSS | 0.298 ± 0.067 | 0.322 ± 0.065 | 0.296 ± 0.065 | 0.298 ± 0.061 |

| Rigid | 0.342 ± 0.051 | 0.340 ± 0.031 | 0.325 ± 0.048 | 0.322 ± 0.056 |

| p-value (LPDSS vs Rigid) | 0.030 | 0.472 | 0.307 | 0.209 |

Table 2.

Results of Radiological Lumbar and Segmental Lordotic Angles of Dynamic and Rigidly Stabilized Groups

| Preoperative | Postoperative (3 Months) | Postoperative (12 Months) | Postoperative (24 Months) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lumbar lordosis angle LPDSS |

mean range |

45.9 ± 15.1 6-72 |

45.9 ± 12.6 20-81 |

45.3 ± 14.1 21-77 |

45.8 ± 13.0 24-76 |

| Lumbar lordosis angle Rigid |

mean range |

51.2 ± 10.9 22-63 |

48.4 ± 9.4 32-65 |

47.0 ± 10.7 29-64 |

46.1 ± 10.2 23-61 |

| p-value (LPDSS vs. Rigid) | 0.186 | 0.367 | 0.538 | 0.937 | |

| Segmental lordosis angle LPDSS |

mean range |

11.0 ± 5.5 1-20 |

9.84 ± 6.0 2-24 |

10.8 ± 4.7 3-21 |

9.3 ± 4.4 1-20 |

| Segmental lordosis angle Rigid |

mean range |

10.9 ± 5.0 2-22 |

10.3 ± 4.2 4-21 |

9.7 ± 3.7 4-19 |

9.9 ± 3.0 5-17 |

| p-value (LPDSS vs. Rigid) | 0.885 | 0.520 | 0.635 | 0.511 |

In the LPDSS group, the mean duration of surgery was 111.8 minutes (range 90-195 minutes). The mean estimated blood loss was 186.8 ml (range 50-400 ml). The mean duration of hospital stay was 6.2 days (range 3-14 days).

In the rigidly stabilized group, the mean duration of surgery was 130.2 minutes (range 80-240 minutes), which was not significantly different from the duration of LPDSS surgery (p = 0.51). The mean estimated blood loss was 252.7 ml (range 60-700 ml), which was not significantly different from that of the LPDSS group (p = 0.93). The mean duration of hospital stay was 7.9 days (range 5-18 days), and not significantly than the mean hospital stay of the LPDSS group (p = 0.26).

The mean postoperative IVS ratio at each level (Table 1) was not significantly different from the preoperative IVS ratio in either group at this time point or any subsequent time point (p > 0.2). As in the preoperative condition, the mean IVS ratio remained greater in the rigidly stabilized group than in the LPDSS group (p = 0.030, Table 1).

In the LPDSS group: The mean angles of segmental lordosis significant differed at 3 months to 24 months postoperative period (p = 0.033) and no significant changes in other periods (p > 0.07). IVS significant differed at 3 months to 12 months postoperatively (p = 0.015) and no significant changes in all periods (p > 0.063). There is no any significant difference in lumbar lordosis angle at follow up periods (p > 0.79).

In the rigidly stabilized group: Lumbar lordosis was significant differed preoperative and postoperative 24 months (p = 0.038) and no significant changes in other periods (p > 0.137). IVS and segmental lordosis angles remained unchanged or showed a slight but insignificant decrease compared to preoperative angles at this time point and at subsequent time points (p > 0.145).

Three months after surgery, the mean VAS pain score and ODI score decreased significantly compared to preoperative scores in both groups (p = 0.000, Figs. 2 and 3). The mean VAS pain score and ODI score was not significantly different between screw types.

Twelve months after surgery, the mean VAS pain score and ODI score decreased significantly compared to preoperative scores in both groups (p < 0.001, Figs. 2 and 3). Comparing between LPDSS and rigidly stabilized patients, the mean VAS score was significantly greater in rigidly stabilized patients than in LPDSS patients (p = 0.002). However, the mean ODI score was significantly different between screw types (p = 0.004). As in previous time points, the mean IVS ratio, lumbar and segmental lordosis angles did not differ at 12 months between patients treated with rigid stabilization or LPDSS (p > 0.307, Tables 1 and 2).

Twenty-four months after surgery, the mean VAS score and ODI score decreased significantly compared to preoperative scores and postoperative 3and 12 month scores in both groups (p < 0.002, Figs. 2 and 3). There was no significant difference between rigid stabilization and LPDSS in VAS score (p = 0.135) or ODI score (p = 0.051) at 24 months. As in previous time points, the mean IVS ratio was not significant in the rigidly stabilized group than in the LPDSS group (p = 0.209, Table 1). Lumbar and segmental lordosis angles did not differ at 24 months between patients treated with rigid stabilization or LPDSS (p > 0.51, Table 2).

No infection, chronic inflammation, or fibrosis was observed at the two-year follow-up in the LPDSS group. In two cases, loosening was noted in caudal screws. Complications in the rigidly fixated group were more numerous than in the LPDSS group. In 2 cases, pseudoarthrosis was found and these patients were reoperated. In two cases, screws were broken although fusion had occurred at the instrumented levels. For this reason, reoperation was not considered.

DISCUSSION

In this study, the clinical and radiological results are presented for a new LPDSS used to treat chronic low back pain in DDD patients. These results are also compared to those of patients treated with standard rigid stabilization. Two years follow up of the present study showed that LPDSS has satisfactory clinical and radiological results for the treatment of lumbar DDD as compared to rigid stabilization systems.

Rigid fixation systems have numerous disadvantages. There are reports of rigid instrumentation-associated complications, such as risk of pseudoarthrosis (15-96%) [7], facet and disc degeneration [4], adjacent segment disease because of the stress-shielding properties (2-3% per year after stabilization) [8], device-related osteopenia [9], worsened biomechanical properties of the spinal ligaments [10], morbidity and mortality risk because of severe surgery, donor area pain, and loss of motion in treated spinal segments. Additionally, the absence of controlled motion makes the rigid system tend to fracture at the bone-implant interface because of increased surface stress [11]. The surgery for LPDSS is simpler than for rigid stabilization; there is little bone and ligament damage as compared to rigid stabilization. Furthermore, if necessary, the dynamic system may be removed and fusion performed in case of unsuccessful outcome.

Dynamic stabilization devices are a recent technological development in the last two decades. Their theoretical success is based on immobilization of the injured segment to protect it from further injury, and sharing of load across the bridged segment. The goals of dynamic stabilization devices are to: 1) control neutral posture of the segment, 2) control sagittal plane bending of the treated level, 3) unload the intervertebral disk at the treated level, and 4) modify the distribution of loads within the segment, in particular within the intervertebral disk [12].

The Graf ligament system (SEM Sarl, Montroge, France), which was invented by Henri Graf in 1992 [13], is one of the first dynamic stabilization systems used. Graf theorized that the origin of chronic low back pain is abnormal rotational motion, so the device aimed to lock the lumbar facets with limited flexion movement. The system was intended to redistribute the transmission pathway for load across the painful disc by providing posterior tensioning. Clinical outcomes with the system are similar to those after fusion [6].

The Dynesys Dynamic Stabilization System (DSS) (Zimmer Spine, Inc., Warsaw, IN, USA), is a LPDSS that has been shown to achieve some of the goals of dynamic stabilization, namely, control of neutral posture, controlled (but not eliminated) motion, and unloading of the posterior portion of the disc [14]. Whether appropriate levels of reduction in motion and appropriately redistributed loading across the spine are achieved with the device is questionable, however, especially in light of poor results in the hands of some investigators [15].

Recently, the fulcrum assisted soft stabilization (FASS) (Neoligaments, Leads, UK) system was improved which was based on the same technique as the previous ones [16]. The second generation Dynamic Stabilization System (DSS II) was developed which unloads the disk by sharing 25% of the load off the disk at full flexion and extension [17]. Strempel designed and developed the first dynamic hinged screw system (Cosmic, Ulrich GmBH & Co. KG, Ulm, Germany) in 1999. This system (Cosmic) was developed as a stable and nonrigid implant with calcium phosphate coated and hinged screws to maintain limited flexion and extension capability during stabilization [18]. The hinged screw of the Cosmic system prevents rotation, translational instability and screw loosening as compared to the previous systems.

Saphinas screw utilized in this system was designed according to the principles of the Cosmic screw. Based on the fact that the posterior rod is rigid and as the number of treated segments increase the rigidity of the system will surpass the dynamic quanity, critics assert that this system is not fully dynamic but is semirigid. This judgment is correct; however, if pain eradication is the target, then this surgical intervention which is much simpler, will biomechnaically provide an almost stabilizing outcome in comparison to fusion.

Comparison of the components of these dynamic devices shows that the mechanism of dynamism differs among systems. The rods were chosen as the dynamic part in the Graf ligament, Dynesys and DSS II, while the FASS system used the neck of the screw as a fulcrum for movement. In the Cosmic and in the system studied here, the hinged head of the screw was chosen as the dynamic part to enable flexion and extension. Theoretically, a pivoting screw head encompassing a rigid rod should allow a greater magnitude of load bearing than a non-pivoting screw head encompassing a deformable rod if the load vector is such that the rod is under direct compression.

Load transmission across the columns of the lumbar spine are 20-25% in the anterior column, 20-25% in the posterior column and 40-50% in the middle column for young men. In DDD, this distribution is shifted such that 50% of load transmission occurs in the anterior column [19]. The biomechanical study of the LPDSS described here showed that load transmission across the posterior column was reduced relative to a rigid system. Although it is not possible to conclude what percent of load is borne by each column from the biomechanical findings, the posterior shift in axis of rotation that was observed shows that redistribution of loading toward the posterior column does occur. It is possible that less anterior load transmission provides a better chance for regeneration of degenerated discs [20]. In fact, follow-up in our institution of some cases after dynamic screw fixation with the Cosmic system has shown evidence of rehydration of previously degenerated discs (unpublished data).

Although follow up was relatively short in the current study (average 24 months), no degeneration at the vertebral segments adjacent to fixated levels was noted in the dynamically stabilized group. However, two patients in the rigidly stabilized group were reoperated because of adjacent segment disease. Lumbar and segmental lordosis angles were maintained during the follow up period in both the rigidly stabilized and the LPDSS group. The VAS and ODI scores of the patients decreased significantly at 3months, 12 months and 24 months follow-up compared to preoperative scores. However, the differences of decrease between the groups were not significant except in the VAS and ODI score at 12 months.

CONCLUSION

The LPDSS device that was studied has a hinged screw design allowing small axial rotation capacity in addition to primary flexion-extension capacity. This device as a posterior dynamic stabilization system performs clinically with similar outcomes to rigid stabilization after two years in terms of maintenance of lumbar and segmental lordosis and intervertebral space ratio, and improvement in pain and disability. This LPDSS appears to be a good alternative to rigid stabilization.

In longer spaces the rod is required to be dynamically compatible with the dynamic screws. Successful results obtained in our cases in which the dynamic screw and dynamic rod were used, will be published later.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bogduk N. The innervation of the lumbar spine. Spine. 1983;8:286–93. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198304000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fritzell P, Hägg O, Wessberg P, et al. Swedish Lumbar Spine Study Group. Chronic low back pain and fusion; a comparison of three surgical techniques: A prospective multicenter randomized study from the Swedish lumbar spine study group. Spine. 2002;27:1131–41. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200206010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boos N, Webb JK. Pedicle screw fixation in spinal disorders: A European view. Eur Spine J. 1997;6:2–18. doi: 10.1007/BF01676569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cunningham BW, Kotani Y, McNulty PS, et al. The effect of spinal destabilization and instrumentation on lumbar intradiscal pressure: An in vitro biomechanical analysis. Spine. 1997;22:2655–63. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199711150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mulholland RC, Sengupta DK. Rationale, principles and experimental evaluation of the concept of soft stabilization. Eur Spine J. 2002;11(2):198–205. doi: 10.1007/s00586-002-0422-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nockels RP. Dynamic stabilization in the surgical management of painful lumbar spinal disorders. Spine. 2005;30:68–72. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000174531.19982.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Etminan M, Girardi F, Khan S, et al. Revision strategies for lumbar pseudarthrosis. Orthoped Clin North Am. 2002;33(2):381–92. doi: 10.1016/s0030-5898(02)00005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hilibrand AS, Carlson GD, Palumbo MA, et al. Radiculopathy and myelopathy at segments adjacent to the site of a previous anterior cervical arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:519–28. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199904000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McAfee PC, Farey ID, Sutterlin CE, et al. The effect of spinal implant rigidity on vertebral bone density. A canine model. Spine. 1991;16:190–97. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199106001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kotani Y, Cunningham BW, Cappuccino A, et al. The effects of spinal fixation and destabilization on the biomechanical and histologic properties of spinal ligaments. An in vivo study. Spine. 1998;23:672–82. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199803150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goel VK, Lim TH, Gwon J, et al. Effects of rigidity of an internal fixation device. A comprehensive biomechanical investigation. Spine. 1991;16:155–61. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199103001-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McNally DS. Rationale for dynamic stabilization. In: Kim DH, Cammisa FP, Fessler RG, editors. Dynamic Reconstruction of the Spine. 1st. Thieme: New York; 2006. pp. 237–43. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graf H. Lumbar instability; surgical treatment without fusion. Rachis. 1992;412:123–37. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beastall J, Karadimas E, Siddiqui M, et al. The Dynesys lumbar spinal stabilization system; a preliminary report on positional magnetic resonance imaging findings. Spine. 2007;32(6):685–90. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000257578.44134.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grob D, Benini A, Junge A, et al. Clinical experience with the Dynesys semirigid fixation system for the lumbar spine; surgical and patient-oriented outcome in 50 cases after an average of 2 years. Spine. 2005;30:324–31. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000152584.46266.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sengupta DK, Mulholland RC. Fulcrum assisted soft stabilization system; A new concept in the surgical treatment of degenerative low back pain. Spine. 2005;30:1019–30. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000160986.39171.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pimenta L, Diaz R, Sengupta DK. Minimally ınvasive posterior dynamic stabilization system. In: Kim DH, Cammisa FP, Fessler RG, editors. Dynamic Reconstruction of the Spine. 1st. Thieme: New York; 2006. pp. 323–9. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strempel A. Nonfusion stabilization of the degenerated lumbar spine with Cosmic. In: Kim DH, Cammisa FP, Fessler RG, editors. Dynamic Reconstruction of the Spine. 1st. Thieme: New York; 2006. pp. 330–9. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ray CD, Hale JE, Norton BK. Minimally ?nvasive posterior dynamic stabilization system. In: Kim DH, Cammisa FP, Fessler RG, editors. Dynamic Reconstruction of the Spine. 1st ed. Thieme: New York; 2006. pp. 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bozku H, Senoğlu M, Baek S, et al. Dynamic lumber pedicle screw-rod stabilization in vitro biomechanical comparison with standard rigid pedicle screw-rod stabilization. J Neurosurg Spine. 2010;12:183–9. doi: 10.3171/2009.9.SPINE0951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]