Abstract

Imbalance of brain metal homeostasis and associated oxidative stress by redox-active metals like iron and copper is an important trigger of neurotoxicity in several neurodegenerative conditions, including prion disorders. Whereas some reports attribute this to end-stage disease, others provide evidence for specific mechanisms leading to brain metal dyshomeostasis during disease progression. In prion disorders, imbalance of brain-iron homeostasis is observed before end-stage disease and worsens with disease progression, implicating iron-induced oxidative stress in disease pathogenesis. This is an unexpected observation, because the underlying cause of brain pathology in all prion disorders is PrP-scrapie (PrPSc), a β-sheet–rich conformation of a normal glycoprotein, the prion protein (PrPC). Whether brain-iron dyshomeostasis occurs because of gain of toxic function by PrPSc or loss of normal function of PrPC remains unclear. In this review, we summarize available evidence suggesting the involvement of oxidative stress in prion-disease pathogenesis. Subsequently, we review the biology of PrPC to highlight its possible role in maintaining brain metal homeostasis during health and the contribution of PrPSc in inducing brain metal imbalance with disease progression. Finally, we discuss possible therapeutic avenues directed at restoring brain metal homeostasis and alleviating metal-induced oxidative stress in prion disorders. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 12, 1271–1294.

I. Introduction

Neurodegenerative conditions such as prion disorders, Alzheimer's disease (AD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Parkinson's disease (PD), and Huntington's disease (HD) share a common pathogenic event involving the accumulation of β-sheet–rich aggregates of a specific protein in the brain parenchyma of affected individuals. Such protein aggregates are believed to be the proximate cause of neurotoxicity in some conditions and are considered to be an end-stage product of a cascade of events in others (181). The underlying mechanism leading to the development of protein aggregates and accompanying neurotoxicity is relatively clear for some of these conditions, whereas in others, it is still debated. Recent evidence suggests the imbalance of brain metal homeostasis as a common cause of neuronal death in several of these disorders (9, 45, 48, 60, 61, 70, 111, 148, 171, 203, 242). It is believed that a redox-active metal interacts with a specific protein and is reduced in its presence, resulting in the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radicals (OH•) that cause aggregation of the involved protein (16, 206, 215, 224, 225). Prominent redox-active metals that undergo this type of reaction include copper and iron, metals that are often detected in association with protein aggregates specific to AD, PD, and prion disorders (9, 150, 171, 206, 252). Whether the accumulation of these metals is a cause or consequence of the disease process is a subject of much dispute. Although significant information on the contribution of redox-active metals in the pathogenesis of AD, PD, and HD is available, similar information on prion disease–associated neurotoxicity is limited.

Studies aimed at understanding the role of metals in prion-disease pathogenesis have been hindered because of the insoluble nature of PrPSc, the principal agent involved in the pathogenesis of prion disorders (37, 49, 176). Although the biology and pathophysiology of metal–PrPSc interaction has been difficult to elucidate, the interaction of metals with PrPC, the normal counterpart of and the substrate for PrPSc, has been studied extensively by using both in vitro and in vivo techniques. Collectively, the available evidence points to a functional role for PrPC in the uptake and metabolism of copper and iron (117, 142, 143, 204, 205), leading to the hypothesis that dysfunction of PrPC due to conversion to the PrPSc form may contribute to the imbalance of brain metal homeostasis observed in prion disorders (203). Other mechanisms leading to altered metal metabolism and disease pathogenesis have been proposed, and consensus on this issue is still lacking (40, 44).

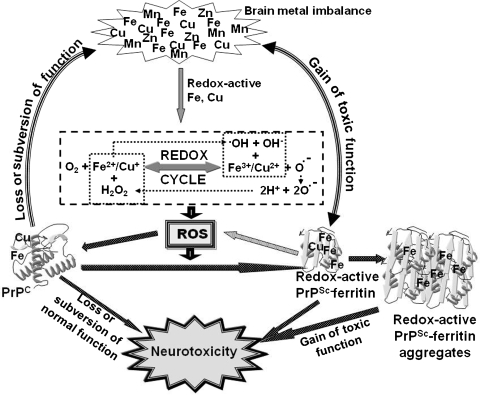

At the center of this debate is PrPSc, the principal molecule involved in the pathogenesis of all prion disorders through mechanisms that are still unclear (1–3). Several pathways of neurotoxicity by PrPSc have been suggested, the most prominent being the induction of toxic signals through PrPC at the neuronal plasma membrane (136). However, neuronal death is often seen in the absence of PrPSc and vice versa, suggesting the presence of alternative pathways of neurotoxicity in addition to PrPSc (119). One of these factors that is often ignored is the depletion of PrPC due to conversion to the PrPSc form. Because PrPC plays a prominent role in protecting neurons against oxidative stress, a significant reduction in PrPC levels may increase the susceptibility of neurons to toxic insults (31, 46, 129, 135, 189). Keeping these facts in mind, both gain of toxic function by PrPSc and loss of normal function of PrPC have been proposed as possible mechanisms of neurotoxicity, and information on both fronts is still emerging. The contribution of these factors individually to disease pathogenesis is difficult to assess because the normal function of PrPC itself is not entirely clear. Diverse functions have been attributed to PrPC based on the model and the experimental design used for evaluation (126, 129, 239). However, because PrPC is involved in copper and iron uptake, it is possible that loss of normal function of PrPC in copper and iron metabolism, combined with gain of toxic function by redox-active PrPSc-ferritin aggregates, induce a state of brain metal imbalance, resulting in metal-induced oxidative stress and neurotoxicity (12, 166, 203–205, 239). The accumulated redox-active iron and copper would further react with dioxygen species abundant in the metabolically active environment of the brain, further aggravating the oxidative damage (169).

In this review, we describe the unique nature of prion disorders and the prevailing hypotheses on the mechanism of neurotoxicity in these conditions. Emphasis is placed on reports that support or contradict the involvement of redox-active metals and associated oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of these disorders. Evidence from other neurodegenerative conditions in which the pathogenic role of redox-active metals has been established is discussed with relevance to the available information on prion disorders. Specific information on the pathophysiology of redox-active metals in prion-disease pathogenesis is divided into three sections: (a) physiologic functions of PrPC as an antioxidant and in copper and iron uptake, (b) pathologic implications of PrPC–metal interaction, and (c) the origin and functional significance of brain-iron dyshomeostasis in prion disorders. We conclude by summarizing possible therapeutic strategies based on the premise that redox-active metal–mediated oxidative stress is a significant cause of neurotoxicity in prion disorders.

II. Prion Disorders: An Overview

A. The unique nature of prion disorders

Prion disorders affect humans and animals and are unique among neurodegenerative conditions of protein aggregation because of their infectious nature. Human prion disorders include sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (sCJD), which comprises 80% of all cases, the less-common inherited forms classified as familial CJD, Gerstmann-Straussler-Scheinker (GSS) disease, and fatal familial insomnia (FFI), based primarily on their phenotypic presentation, and the relatively rare infectious forms such as variant CJD. Animal prion disorders include bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) of cattle, scrapie of sheep, chronic wasting disease (CWD) of deer and elk, and prion diseases of other animals. The principal event in all prion disorders is the change in conformation of PrPC from a mainly α-helical to a β-sheet–rich PrPSc form. Deposits of PrPSc in the brain parenchyma are considered to be the principal cause of neurotoxicity and infectivity in most prion disorders, although prion disease–associated neurotoxicity is sometimes seen in the absence of PrPSc and vice versa (1–3, 40, 79, 115).

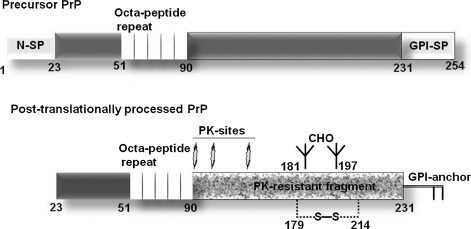

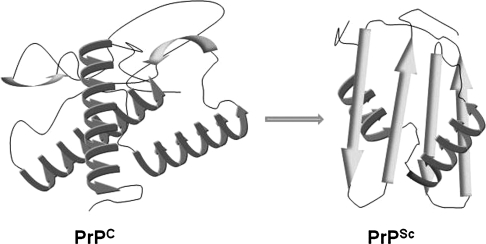

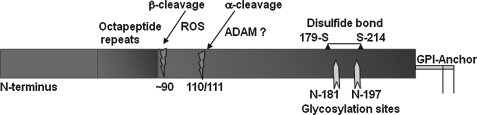

PrPC is a normal cell-surface glycoprotein linked to the plasma membrane by a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) membrane anchor. Like other glycoproteins, PrPC is synthesized as a precursor form with N- and C-terminal signal peptides and is translocated into the endoplasmic reticulum co-translationally (Fig. 1). The N-signal peptide is cleaved soon after translocation, and the C-terminal signal peptide is replaced by a preassembled GPI-anchor in a transamidation reaction within 5 min of synthesis. Subsequently, high-mannose glycans and a disulfide bond are added, and the glycans are trimmed and modified as the protein traverses the Golgi apparatus on its way to the plasma membrane (Fig. 1) (41). The change in conformation of PrPC to the PrPSc form renders it resistant to limited digestion by proteinase-K (PK), sparing the C-terminal fragment comprising of amino acids 90 to 231 and the GPI anchor (Fig. 1). In most instances, the PK-resistant C-terminal fragment is sufficient to transmit prion infection and induce neurotoxicity in the recipient animal. Both full-length and the C-terminal fragment of PrPSc aggregate easily, are insoluble in non-ionic detergents, and resist degradation when exposed to a variety of denaturing agents (Table 1) (1–3). Often referred to as the prion agent (176), PrPSc derives its infectious nature from its unique characteristic of transforming additional PrPC molecules to its own β-sheet–rich PrPSc conformation (Fig. 2). However, the mechanistic details of the conversion process are not completely clear. In sporadic prion disorders, the conversion of PrPC to PrPSc is believed to occur as a random event. In inherited disorders, certain point mutations in the prion protein-coding region induce the transformation of PrPC to PrPSc, and in infectious disorders, PrPSc from an exogenous source induces the conversion of host PrPC to its own conformation (1–3, 40, 176). Figure 3 demonstrates aggregates of PrPSc in the brain parenchyma of a sCJD case immunostained with PrP-specific antibody and spongiform change in the surrounding cells.

FIG. 1.

Precursor and posttranslationally processed PrPC. Precursor PrPC is translocated co-translationally into the ER where the N-signal peptide is cleaved by a signal peptidase. After translocation, the C-terminal GPI-signal peptide is replaced by a preassembled GPI anchor in a transamidation reaction within 5 min of synthesis. Subsequently, the disulfide bond and mannose-rich glycans are added in the ER, and the protein is transported to the Golgi complex where immature glycans are processed to their complex form. The mature protein is transported to the plasma membrane through secretory vesicles. The change in conformation of PrPC to PrPSc renders the protein partially resistant to digestion by limited amounts of PK that cleaves PrPSc at the indicated sites. The C-terminal PK-resistant fragment is sufficient by itself for prion disease–associated neurotoxicity and infectivity. CHO, carbohydrates; S-S, disulfide bond; PK, proteinase K; N-SP, N-terminal signal peptide; GPI-SP, C-terminal signal peptide.

Table 1.

Biochemical and Biophysical Characteristics of PrPC and PrPSc

| Biochemical characteristic | PrPC | PrPSc |

|---|---|---|

| Secondary structure | 43% α-helix | 30% α-helix 43% β-sheet |

| Solubility in non-ionic detergents | Soluble | Insoluble |

| Sensitivity to limited digestion with PK | PK sensitive | PK resistant |

| Aggregation | Not aggregated | Aggregated |

| Infection | Not infectious | Infectious |

FIG. 2.

Structural differences between PrPC and PrPSc. A model of the α-helical structure of PrPC and the β-sheet–rich PrPSc form implicated in prion-disease pathogenesis.

FIG. 3.

Deposits of PrPSc in the brain. Brain section from a case of sCJD immunostained with anti-PrP antibody 3F4 shows immunoreactive deposits and spongiform change in the surrounding tissue.

Infectious prion disorders were first recognized as Kuru in the Fore tribe of Papua New Guinea, where cannibalism was a ritualistic practice, and later as variant CJD that was most likely transmitted to humans through the consumption of BSE-infected meat (36, 50). Currently, CWD is spreading in certain parts of the United States, and the possibility of horizontal spread of this agent and transmission to cattle and humans is uncertain (56, 237). In addition to the oral route, the prion agent can be transmitted through the bloodstream or peripheral nerves, either accidentally, iatrogenically, or through skin abrasions (128, 221). Although much publicized, infectious prion disorders of humans are relatively rare and comprise only 1% of all reported cases of prion disorders (Table 2). It is important to note that although infectivity of PrPSc has been demonstrated for most cases, some forms are relatively resistant to transmission. The prion disorders of humans and animals and the underlying cause of disease are described in Table 2 (2, 40, 53, 176). For discussion, we do not distinguish between PrPSc of sporadic, inherited, or infectious origin, and consider it as the common pathogenic agent for all prion disorders.

Table 2.

Human and Animal Prion Disorders

| Prion disease | Underlying cause of disease |

|---|---|

| Human | |

| Sporadic | Spontaneous conversion of PrPC to PrPSc |

| Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (sCJD), Fatal | |

| Familial insomnia (sFFI) | |

| Familial | Point mutations in the coding region of PRNP gene leading to conversion of mutant PrP to the PrPSc form |

| fCJD, FFI | |

| Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker syndrome (GSS) | |

| Infectious | Acquired from an exogenous source of PrPSc through food products or iatrogenically |

| Variant CJD | |

| Iatrogenic CJD | |

| Kuru | |

| Animal | |

| Sporadic | Spontaneous conversion of PrPC to PrPSc |

| Scrapie of sheep | |

| Chronic wasting disease (CWD) of deer and elk | |

| Infectious | |

| Bovine encephalopathy of cattle (BSE) | Horizontal and vertical transmission of PrPSc from feed and through poorly understood mechanisms |

| Exotic ungulate encephalopathy | |

| Feline spongiform encephalopathy | |

| Scrapie and CWD | |

| Transmissible mink encephalopathy |

1. The “prion” agent

Mammalian prions are considered synonymous with PrPSc, and the word “prion” is derived from proteinaceous infectious particle to symbolize the unique characteristic of a protein as the principal infectious agent (176). Over the years, diverse experimental models have been used to understand the mechanism(s) of conversion of PrPC to PrPSc and the cause of the associated neurotoxicity. Several important facts have emerged from these studies. For example, it is now clear that for prion transmission, a certain degree of homology between the exogenous PrPSc and host PrPC is required, the absence of which accounts for the species barrier in prion transmission and the presence of prion-resistant genotypes (2, 79, 115). In some cases, however, heterologous PrPSc has been demonstrated to induce subclinical disease or adapt to an apparently resistant host and to cause disease on subsequent passage (92, 178). In familial disorders, point mutations are believed to render mutant PrP forms susceptible to a change in conformation to PrPSc at an advanced age, although the contributing factors that precipitate this change remain unidentified (2, 176). The fact that PrPSc can be taken up by neuronal cells fairly nonspecifically, but only a few cell lines can sustain persistent PrPSc infection, points to cell-specific factors that are necessary for successful propagation (19, 59, 134, 229). Several experimental paradigms have been tried to understand the generation of PrPSc in vitro and in vivo. The most prominent in vitro method involves conversion of cellular, brain-derived, or recombinant PrPC to a form similar to PrPSc by the protein-misfolding cyclic-amplification reaction (PMCA) by using brain-derived PrPSc as the inoculum (39). The conversion process is enhanced by RNA molecules, redox-active metals like copper, certain denaturants, sulfated glycans, solvents, pH, temperature, reducing agents, inhibition of glycosylation, and a combination of buffer conditions and metal ions (156, 197, 246). However, PrPSc generated by only some of these reactions can change additional PrPC to PrPSc in vitro and cause disease when introduced to recipient animals (39, 54). Other forms resemble PrPSc in certain biochemical characteristics and either are not infectious, or have not been assessed in bioassays to evaluate infectivity (8, 156).

2. Mechanism(s) underlying prion-associated neurotoxicity

Despite evidence suggesting PrPSc as the principal pathogenic and transmissible agent responsible for all prion disorders, it is important to note that prion-specific neurotoxicity is sometimes observed in the absence of detectable PrPSc, and PrPSc deposits may occur in the absence of neurotoxicity (43, 67, 119, 173). Thus, other players besides PrPSc that influence prion transmission and neurotoxicity exist and are gradually being discovered. Several important facts have emerged from these studies. For example, it is clear that regardless of PrPSc load, expression of PrPC on the host neuronal plasma membrane is essential for neurotoxicity. Transgenic mice expressing anchorless PrPC accumulate infectious PrPSc in the extracellular milieu but do not demonstrate neuronal death, suggesting that the neurotoxic signal is transmitted through plasma membrane–associated PrPC (43, 79, 136). However, astrocyte-specific expression of PrPC is sufficient to support the replication and neurotoxicity of infectious PrPSc, even in the absence of neuronal PrPC expression, indicating the involvement of other neurotoxic molecules or mechanisms in this process (98). Controversies about the neurotoxic nature of PrPSc have led to the identification of other PrP conformers that may be involved in the pathology of prion disorders (44, 81). Prominent among these are the C-transmembrane and cytosolic forms of PrP that induce neurotoxicity by poorly understood mechanisms (72, 82–84, 130, 131, 145). Investigations of mutant PrP forms by using cell models of familial prion disorders indicate that a combination of direct and indirect effects of the mutation alter posttranslational processing, transport, and the cellular site of accumulation of specific PrP forms, resulting in toxicity due to aggregation or conversion of PrPC to a PrPSc-like form at that site (71–75, 101, 145). In addition, PrP amyloid fibrils (157), certain structurally misfolded intermediates of PrPC, and small oligomers in the pathway of PrPSc formation (79, 202) also are considered neurotoxic, possibly because of characteristics unique to their structure. Cross-linking of PrPC on the plasma membrane has been noted to induce neurotoxicity (209), perhaps by activating certain apoptotic pathways or by compromising the normal function of PrPC (174, 182–184).

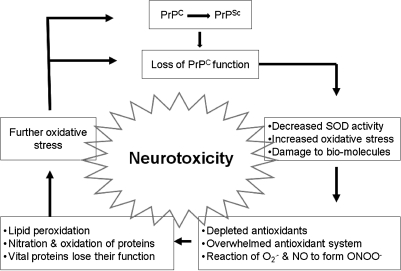

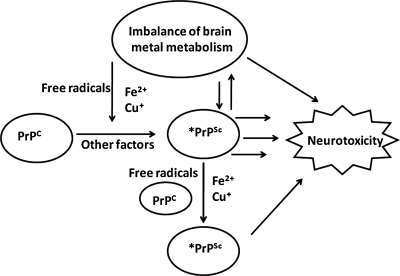

A compelling set of observations suggest that subversion or loss of normal function of PrPC is an equally significant cause of prion disease–associated neurotoxicity (34, 66, 79, 155). The specific function of PrPC involved in this process, however, has been difficult to identify because of the variety of functional activities attributed to this protein, based on the experimental design and the method used. Among these, the neuroprotective function of PrPC demonstrated in cell lines, primary neurons, and in vivo models is noteworthy (174, 183). Studies of primary human neurons suggest that PrPC protects cells against Bax-induced cell death by inhibiting the conformational change of Bax, supporting the loss-of-function hypothesis of neuronal death (184, 185). Other studies suggest a protective role of PrPC by virtue of its property to function as a Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase (SOD), although several other studies refute this claim (26, 32, 96). It is likely that compromised function of this enzyme in prion disease–affected brains (245) increases the susceptibility of neurons to toxic signals that are generated as a by-product of normal cellular metabolic processes. It has also been proposed that PrPC is a free radical–scavenging protein, and loss of this activity in mutant PrP forms increases the susceptibility of neurons to toxicity (236). The protective function of PrPC is further exemplified by the fact that expression of a single copy of PrPC can rescue the ataxic phenotype of transgenic mice expressing a deletion construct of PrP (PrP▵32-121/134) (199), slow neurodegeneration in transgenic mice expressing a pathogenic mutation of PrP (217), rescue neurons from Doppel-induced toxicity (149), and protect brain tissue from ischemia- and trauma-induced insult (210, 238). Moreover, PrPC is believed to function as a copper- and iron-uptake protein, suggesting a role in the maintenance of cellular copper and iron homeostasis (33, 126, 205, 226). Collectively, these reports suggest that loss of normal function of PrPC can be as significant as accumulation of PrPSc in inducing prion disease–associated neurotoxicity (Fig. 4). Although it is difficult to distinguish between these possibilities because PrPC is the substrate for PrPSc, these observations underscore the importance of the physiologic function of PrPC in disease-associated neurotoxicity.

FIG. 4.

Loss of PrPC function as a contributing factor in prion disease–associated neurotoxicity. PrPC has been ascribed several physiologic functions, including a role in protecting cells from oxidative stress. The change in conformation of PrPC to the PrPSc form is likely to compromise the normal protective function of PrPC, resulting in neurotoxicity.

B. Redox metals, oxidative stress, and prion-disease pathogenesis

Among the redox-active metals, iron and copper are most relevant because PrPC is involved in their metabolism, thereby increasing the likelihood of their involvement in prion-disease pathogenesis. A significant amount of information is already available on the neurotoxic role of iron in disorders such as AD, multiple sclerosis, PD, tardive dyskinesia, Pick's disease, HD, Hallervorden-Spatz disease, Friedreich's ataxia, and aceruloplasminemia (10, 11, 68, 250–253). In addition to iron excess, a deficiency of this metal is equally harmful and can result in compromised motor and cognitive function, in addition to other manifestations of anemia (15, 133). Likewise, an increase in brain copper content is neurotoxic (213, 218), and copper deficiency is known to compromise the function of Cu/Zn-SOD, an important antioxidant enzyme essential for cell survival (13). Zinc is redox inactive but is important for neurotransmission, and inadequate supplies can result in compromised neuronal function (235). The role of other metals in brain function has been reviewed elsewhere (148).

Observations from prion disease–affected human and mouse brains suggest that iron- and copper-induced oxidative damage is a significant factor affecting disease pathogenesis (107, 109–111, 142, 171, 201). Although the underlying cause of metal imbalance is not clear, recent reports indicating a facilitative role of PrPC in iron and copper uptake and interference with manganese uptake suggest that loss of this function as a result of aggregation to the PrPSc form may contribute to brain metal dyshomeostasis, resulting in metal-induced oxidative damage (147, 166, 204, 205). Furthermore, iron and copper may remain associated with PrPSc, thus rendering the complex redox active and neurotoxic (12, 203). Observations reporting the generation of H2O2 by certain fragments of PrP, when exposed to iron or copper, lend credence to this hypothesis (106, 224, 225). Whether these fragments exist in vivo and undergo such a reaction is not clear, but it suggests that abnormal forms of PrP or its fragments are likely to contribute to the generation of free radicals. Similar observations have been reported for amyloid-beta (Aβ), the principal component of neurotoxicity in AD. The interaction of Aβ with iron and copper is believed to mediate its protease resistance and oxygen-dependent production of free radicals (4, 207). Normally, antioxidants such as glutathione transferase and catalase detoxify the free radicals produced through these reactions to protect the cells from the highly neurotoxic OH• radical generated by the Fenton reaction. However, increased production combined with compromised capability to detoxify such radicals is likely to result in the neurotoxicity associated with AD.

A similar process of oxidative stress and associated neurotoxicity is likely to occur during prion-disease progression. Markers of metal-induced oxidative stress such as products of lipid peroxidation, including free malondialdehyde (MDA) and increased levels of Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions, have been identified in the cerebral cortex, striatum, and brainstem of prion disease–affected human and mouse brains, supporting this assumption (5, 108, 109, 111, 171, 203). The state of increased oxidative stress could result from direct toxicity by PrP–metal complexes, increased susceptibility of neuronal cells to free radicals due to the compromised function of PrPC, or a combination of both processes (22, 140, 141, 182). It is more likely that both processes operate simultaneously because PrP knockout (PrP-/-) mice that lack PrP expression exhibit increased vulnerability to superoxide, H2O2, and copper ions, and show evidence of oxidative stress, such as elevated levels of protein carbonyls and ubiquitin-protein conjugates in their brains (20, 112, 187, 244, 245). In scrapie-infected mouse brains and cells replicating mouse prions, activities of antioxidant enzymes glutathione-peroxidase, reductase, and SOD are reduced, whereas markers of oxidative stress such as MDA, 4-hydroxyalkenals (HAE), and reactive aldehyde products of lipid peroxidation are increased (25, 141, 249). In addition, levels of 3-nitrotyrosine, heme oxygenase-1, carbon monoxide, and iron are increased, further supporting these observations (47, 77, 203, 249). These changes cause oxidative damage to proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids, prominent features of scrapie-infected mouse and CJD-affected human brains (64, 76, 162).

Evidence of oxidative stress is also noted in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and plasma of sCJD patients that show lipid peroxidation and reduced levels of polyunsaturated fatty acids, ascorbate, and α-tocopherol (6). In certain cases of GSS and vCJD, deposits of iron and its storage protein, ferritin, are seen in the brain parenchyma in association with and in the tissue surrounding PrPSc plaques (171), suggesting a causal relation. In addition, sCJD- and scrapie-infected Syrian hamster brains show a combination of oxidative, glycoxidative, lipoxidative, and nitrative protein damage, accompanied by increased oxidative response, as indicated by elevated levels of the oxidized nucleic acid base 8-hydroxyguanosine (8OHG) and HNE-modified proteins, neuronal, endothelial, and inducible nitric oxide synthase (nNos, eNos and iNos), SOD 1, and SOD 2, glutamic and aminoadipic semialdehydes (products of metal-catalyzed oxidation), malondialdehydelysine (product of lipoxidation), N-ɛ-carboxyethyl lysine (product of glycoxidation), and N-ɛ-carboxymethyl lysine (generated by lipoxidation and glycoxidation) (64, 76, 162, 249). An in vivo study of scrapie-infected mice links peroxidative damage directly to neuronal loss and de novo PrPSc propagation, establishing a causal link between PrPSc accumulation, oxidative damage, and disease pathogenesis (25). PrPSc itself is a target of increased oxidative modifications (162), suggesting the presence of chronic oxidative stress in diseased brains. Interestingly, metal-induced oxidative stress has been reported to cause the aggregation and insolubility of PrPC to a form similar to PrPSc in cell models (12) and to decrease infectivity by causing the hydroxylation and degradation of PrPSc (164), indicating a role in both the generation and degradation of PrPSc. Besides, it has been suggested that the conversion of PrPC to PrPSc involves the formation of a redox-active copper complex within the plasma membrane (125, 142, 154), supporting the idea that the generation of PrPSc is facilitated by redox ions. Although apparently contradictory, these observations probably reflect a continuum of the same process; redox-iron induced aggregation of PrPC to PrPSc, followed by degradation of oxidatively modified PrPSc by scavenger cells using a similar metal-catalyzed reaction.

In addition to the direct damage to proteins and lipids noted earlier, reactive oxygen species (ROS) also sensitize the cells to endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress (88). This is an important observation because several mutant forms of PrP associated with familial prion disorders induce ER stress due to misfolding or aggregation or both. This would aggravate the toxicity due to ER and oxidative stress individually, providing a common pathway of neuronal death for sporadic and familial prion disorders (88, 89). Furthermore, activity of NF-κβ, a transcriptional activator of proinflammatory cytokines, and proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and interleukins 1α and 1β are elevated in scrapie-infected mouse brains, a situation that can further induce the upregulation of iron-uptake proteins and increase the content of brain iron, thus creating an ongoing state of oxidative stress (108, 114, 150).

Collectively, this information leaves little doubt that oxidative stress plays a prominent role in prion disease–associated neurotoxicity. However, it is difficult to conclude whether this is a cause or consequence of the disease process. Subsequently, we review available information on PrP–metal interaction, the physiologic and pathologic implications of this association, and the likely cause(s) of brain metal dyshomeostasis in prion disorders.

III. Redox Control of Prion Protein: Physiological Implications

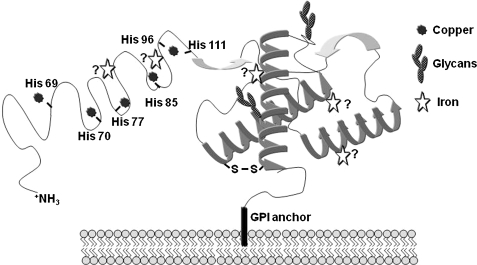

The physiologic role of PrPC in cellular redox control is poorly understood. However, enough evidence exists to implicate PrPC in redox reactions that serve the general purpose of intracellular signaling (174, 193), protection against oxidative stress (120, 219), and modulation of synaptic activity (85, 117, 228). The redox potential of PrPC is mainly because of its association with redox-active metals such as copper and iron, although PrP is known to interact with other metals, including zinc, manganese, and nickel (23, 29, 97, 233). Copper and zinc interact with the octapeptide repeat region of PrPC at the N-terminus and influence its functional characteristics in distinct ways (142, 233). It has been suggested that this interaction facilitates the folding of the largely unstructured N-terminus, providing stability to the protein (121). Because prion disease–affected brains contain altered concentrations of Cu and other divalent cations (87, 219, 243), it is likely that a deficiency or excess of these metals further contributes to the instability of PrPC and an increased propensity to convert to the PrPSc form (125). Manganese also interacts with PrPC and alters its function (28, 48). Relatively less is known about the interaction of PrPC with iron, a metal with significantly higher redox potential than copper. Because both copper and iron are essential for cellular metabolism and are toxic if mismanaged, the interaction of PrPC with these metals has both physiologic and pathologic implications. We first summarize information on PrPC–copper interaction, because this is better understood, followed by available information on the interaction of PrPC with other metals, including iron.

A. PrP and copper interaction

A growing body of evidence suggests that PrPC is involved in copper metabolism. This phenomenon has been studied extensively by using recombinant PrPC, peptide fragments of PrPC, cell models, and mouse models (29, 52, 102, 113, 226). Collectively, these studies indicate that human PrPC binds five Cu2+ ions under physiologic conditions. Four copper-binding sites are within the octapeptide repeat sequence Pro-His-Gly-Gly-Gly-Trp-Gly-Gln, between residues 61 and 91 of PrP (Fig. 5). This region binds copper ions with femto- and nanomolar affinity, and other metal ions like Ni2+, Zn2+, and Mn2+ with affinities lower by at least three orders of magnitude. The fifth copper-binding domain is between residues 91 and 111 and is coordinated by histidine residues at positions 96 and 111 of the PrP sequence (Fig. 5). This site has a lower affinity for copper than the octapeptide repeat region (7, 93–95, 103, 195). The binding is optimal at physiologic pH 7.4, and decreases precipitately at acidic pH (241). However, the in vitro results should be interpreted with caution because these studies use recombinant PrPC, and the affinity of proteins for metals is known to differ by several orders of magnitude when they are in their native conformation and environment. It is notable that the octapeptide repeat region is conserved among mammalian species, and insertion of one or more octapeptide units in the PrP sequence is associated with familial CJD in humans and prion disease in experimental mice (211). The mechanism by which additional repeats induce disease, however, is not entirely clear. It is probable that altered copper concentrations in the brain due to increased binding sites play a role (116). Further investigations are required to understand this phenomenon fully.

FIG. 5.

Copper- and iron-binding sites on PrPC. A model of PrPC with known copper-binding sites in the octapeptide repeat region and the histidine residue 111. The putative iron-binding sites are based on data from recombinant full-length PrPC and its fragments. Denaturation of PrPC releases all bound iron, suggesting that the interaction of PrPC with iron is sensitive to its secondary or tertiary structure.

Although the binding sites and affinity of PrPC for copper are known, the redox state of bound copper is not clear. Some reports suggest that PrPC-associated copper is in its reduced form because of the presence of tryptophan residues within the PrP sequence that function as redox acceptors (186). Contradictory reports indicate that copper is bound in the nonreduced form and sequesters potentially harmful free radicals, thereby serving a protective function (198). Exposure of PrPC-bound copper to H2O2 oxidizes Cu1+ to Cu2+ with the generation of hydroxyl radicals that are highly toxic and are believed to cause the aggregation of PrPC. The redox-active form of copper reacts with free radicals and induces the generation of ROS, resulting in β-cleavage of PrPC near the octapeptide repeat region, a reaction facilitated by tryptophan residues that act as one-electron donors to mediate the reduction of the Cu2+ center to Cu1+ (Fig. 6) (234). Based on these observations, PrPC has been proposed as a “sacrificial quencher” of free radicals (154). Similar aggregation of PrPC is noted when the cells are exposed to a source of redox-iron (12), suggesting that the PrP–metal interaction may serve a protective role by sequestering extracellular redox-active ions, and aggregation of PrPC may in part be a consequence of this process. The affinity of PrPC for copper is optimal to quench excess copper ions and to function as a copper-uptake protein, supporting these observations (125, 126, 142).

FIG. 6.

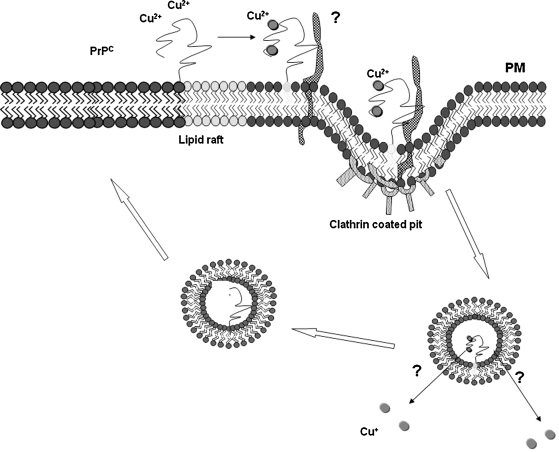

Regulated and ROS-mediated cleavage of PrPC. PrPC undergoes a regulated cleavage at amino acids 110/111 mediated by the ADAM family of proteases in an endocytic compartment, termed α-cleavage. The resulting C-terminal fragment is transported back to the plasma membrane. In addition, PrPC undergoes ROS-mediated cleavage near amino acid 90, termed β-cleavage. This event believed to protect PrPC-expressing cells from free radical damage.

The functional role of PrPC in copper uptake from the extracellular milieu has been studied in cultured cells and mouse models. In mouse neuroblastoma cells, extracellular copper ions stimulate the endocytosis of PrPC, supporting the idea that PrPC may bind and deliver extracellular copper ions to endocytic compartments. Deletion of the octapeptide repeat region or mutation of histidine residues within this region abolishes copper uptake by PrPC, emphasizing the role of this region in copper binding (35, 166, 167, 198, 212, 216). A similar mechanism of copper uptake has been demonstrated in PrPC-GFP–expressing SN56 cells (122). In addition to serving as a copper-uptake protein, it is believed that the octapeptide repeat region of PrPC reduces captured Cu2+ ions before their delivery to Cu1+-specific intracellular copper-carrying proteins (147), serving an important role in copper transport across the endosomal membrane. Studies using radioactive copper indicate that nonchelated 67Cu is taken up by PrPC-deficient neurons as efficiently as neurons expressing PrPC, whereas 67Cu chelated with histidine is taken up in proportion to neuronal PrPC expression. Interestingly, 67Cu levels in SOD 1 are in direct proportion to PrPC-expression levels, suggesting that decreased SOD 1 activity in PrPC-deficient cells may in part be due to deficient delivery of copper to the enzyme (33). Similar observations have been reported for a rat kidney cell line RK13A, in which expression of PrPC increases copper binding and the activities of antioxidant enzymes without altering copper delivery (180). Although these observations implicate PrPC as a major copper-uptake and -delivery protein, this is unlikely, because the brain copper and zinc content of mice expressing wild-type levels or 10-fold higher levels of PrPC are similar to those in mice lacking PrP (PrP−/−) (231), leaving the matter unsettled. A plausible explanation for these disparate findings could be that PrPC alters the distribution of copper rather than its overall content in the brain, as observed for zinc (179). This assumption is supported by the fact that the copper content of synaptosomal membranes that express high levels of PrPC is twofold higher in wild-type mice compared with PrP−/− mice, an observation that has prompted the suggestion that PrPC regulates copper concentration at the synapse by serving as a sink for excess copper ions released during synaptic vesicle fusion (117, 228). Such a function would maintain physiologically safe levels of copper in presynaptic cytosol, a site that is exposed to high concentrations of copper because of release of copper ions from nerve endings after depolarization. In addition, such a function would prevent the potentially harmful participation of unbound copper in Fenton- and Heber-Weiss–type redox reactions that generate reactive oxygen species and redistribute the released copper back to presynaptic cytosol for recycling (228). Figure 7 is a diagrammatic representation of the putative mechanism(s) of copper uptake and transport by PrPC.

FIG. 7.

Mechanism of copper uptake by PrPC. PrPC is a GPI-linked protein that normally resides in cholesterol- and sphingolipid-rich rafts on the plasma membrane. On exposure to copper, PrPC binds copper in the octapeptide repeat region and relocates to the vicinity of a transmembrane protein, and the complex is internalized in clathrin-coated pits. Bound copper is released in an endosomal compartment and reduced by the octapeptide repeat region of PrPC before transfer to cytosolic copper-carrier proteins. The N-terminal region of PrPC is cleaved proteolytically in an endocytic compartment (α-cleavage), and the C-terminal 18-kDa fragment is transported back to the plasma membrane.

Interestingly, copper ions have been demonstrated to upregulate PrPC expression, and conversely, PrPC regulates the copper content of cells. The former function is achieved by activating a metal-responsive element in the promoter region of PrPC (17, 227), and the latter, by shedding PrPC into the culture medium when exposed to copper or to a zinc metalloprotease (165, 223). Upregulation of PrPC by copper is reversed by copper chelators, confirming the specificity of the reaction. A similar upregulation of PrPC is noted when cells are exposed to iron or cadmium, but not to zinc or manganese (12, 226). In this regard, the effect of metals on PrPC expression differs from metallothionines and Cu/Zn-SOD genes that are induced by all three metals: copper, cadmium, and zinc (153, 179, 247).

Together, these studies suggest a role for PrPC in cellular copper uptake and transport, maintenance of physiologically safe copper concentrations at the synapse, upregulation of PrPC expression in response to copper, and cleavage, shedding, and aggregation of copper-bound PrPC when exposed to free radicals. Other less-defined outcomes of PrPC–copper interaction have also been reported, leading to the conclusion that the role of PrPC in copper metabolism is complex and is likely to involve presently unidentified pathways that influence cellular copper homeostasis.

B. PrP and other metals, in particular iron

Physiological implications of the interaction of PrPC with other metals, such as manganese, iron, zinc, and nickel, are poorly understood (86, 87). The majority of these metals induce the aggregation of purified or recombinant PrPC to a form resembling PrPSc in certain characteristics (156). However, these evaluations involve in vitro experiments, and the influence of these metals in the in vivo situation is unclear, except for zinc, which induces rapid turnover of PrPC (35). Limited studies suggest that manganese can displace copper and bind to PrPC, which then mediates its uptake into cells and is rendered protease resistant by this association (28).

The interaction of PrPC with iron deserves a special note, because iron is required for optimal neuronal growth (14), and, like copper, is considered a toxin because of its ability to exist in two oxidation states, ferric (Fe3+) and ferrous (Fe2+) (104, 220). Free iron can catalyze the conversion of hydrogen peroxide to reactive hydroxyl radicals by the Fenton reaction, resulting in oxidative damage. Furthermore, iron-dependent lipid peroxidation generates potentially toxic peroxyl/alkoxyl radicals (78), and iron is known to convert neutral catechols to neurotoxic intermediates, compounding the neurotoxicity (192). Figure 8 provides a partial list of normal functions of iron in the brain and possible mechanisms of iron-mediated toxicity, and Fig. 9 illustrates the possible contribution of PrPC and PrPSc in this process.

FIG. 8.

Brain-iron dyshomeostasis as a possible cause of prion disease–associated neurotoxicity. Maintenance of normal brain-iron homeostasis is essential for several vital metabolic processes, and iron deficiency is likely to compromise essential brain functions. Excess iron can induce neurotoxicity because of its redox-active nature, underscoring the necessity for maintaining brain-iron levels within normal limits.

FIG. 9.

Possible mechanisms of neurotoxicity in prion disorders. Several triggers induce the conversion of PrPC to the disease-causing PrPSc form, including metal-induced oxidative stress. Once formed, PrPSc deposits increase the content of redox-active iron in the brain, thus feeding into the generation of additional PrPSc and worsening the state of brain-metal homeostasis. Neurotoxicity results from the direct effect of PK-resistant or certain species of PK-sensitive PrPSc, or both, and because of the redox-active nature of PrPSc complexes through poorly understood pathways.

It has been demonstrated that brain iron increases with age in humans, rats, and mice, increasing the chances of metal-induced free radical injury detected most often in the basal ganglia, hippocampus, and cerebellar nuclei (51, 137, 208). Levels of ferritin also increase with aging in human brains, suggesting a precarious balance of iron metabolism and an increased propensity for dysregulation with the slightest insult (251). Because imbalance of cellular iron homeostasis can result in the generation of ROS, the transport of iron in and out of the cells is tightly regulated. Within cells, iron is present in ferritin, which serves the general function of intracellular iron sequestration, detoxification, and storage. Under conditions in which capacity of ferritin to detoxify iron is exceeded, Fe2+ can participate in one-electron transfer reactions, resulting in the formation of reactive intermediates, including OH• radicals that can catalyze the oxidation of proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, and nucleic acids, ultimately leading to cell death by apoptosis or necrosis. Cells have therefore developed sophisticated mechanisms to regulate iron metabolism through coordinated control of transferrin (Tf ) and transferrin receptor (TfR)– mediated uptake, and ferritin-mediated sequestration in the cytosol. Ferritin regulates the labile iron pool within cells and is itself regulated by iron-regulatory proteins (IRP) 1 and 2. When cells are iron deplete, IRP 1 and 2 bind to iron-responsive elements (IREs) in the TfR and ferritin mRNAs, blocking degradation of the former and decreasing translation of the latter. The net result is an increase of a labile iron pool for metabolic use. The opposite scenario takes effect when cells are iron replete (132, 150, 163).

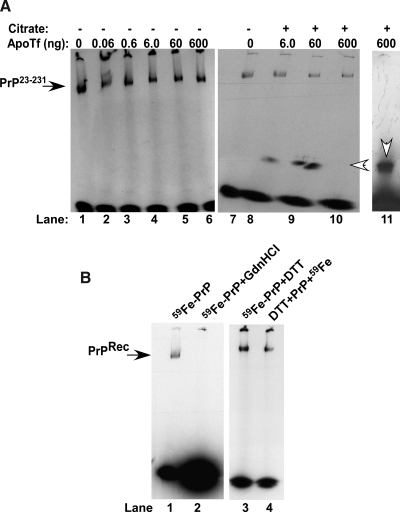

Within this tightly orchestrated mechanism of homeostasis by well-characterized proteins, it is surprising that PrPC influences iron uptake and transport (204, 205). Efforts aimed at understanding the stoichiometry of PrPC–iron interaction and specific binding sites have yielded mixed results. Recombinant full-length PrP (PrP23-231) can be radiolabeled with iron (59Fe) and fractionated on nondenaturing gels, indicating a sufficiently strong interaction (12). Cell-associated PrP can also be radiolabeled, and the PrP–iron complex can be isolated by immunoprecipitation, indicating a biologically relevant interaction (12). Surprisingly, 59Fe bound to PrP23-231 is not transferred to apo-transferrin, a protein with a very high affinity for iron (Fig. 10A, lanes 1–6) except in the presence of citrate, which forms a 59Fe–citrate complex for transfer to transferrin. This is evident from the appearance of a faster-migrating band with increasing concentrations of apo-Tf that co-migrates with 59Fe-charged Tf (Fig. 10A, lanes 1–11) (172). These results indicate that the association of 59Fe with PrP23-231 is not due to nonspecific sticking or an artifact of the experimental procedure. Interestingly, denaturation of recombinant PrP23-231 with guanidinium hydrochloride releases the bound iron completely, whereas reduction of disulfide bonds before or after the addition of the 59Fe–citrate complex has no measurable effect, suggesting that the interaction of PrPC with iron is sensitive to its conformation (Fig. 10B, lanes 1 to 4). However, these observations are of limited relevance, because cell- and brain-associated PrPC does not show a similar affinity for iron (12, 205). It is therefore likely that under physiological conditions, the interaction of PrPC with iron is transient or of low affinity, such that the bound iron is released during experimental manipulation (205).

FIG. 10.

Recombinant full-length PrP binds iron with relatively high affinity. (A) PrP23-231 (1 μg) was radiolabeled with 59Fe–citrate complex for 10 min, dialyzed extensively, and incubated with increasing concentrations of apo-Tf in the absence (lanes 1–6) or presence (lanes 7–10) of citrate, followed by fractionation on a native gel (172, 203–205). Autoradiography reveals a prominent 59Fe-labeled band of PrP23-231 (lanes 1–6) that releases bound 59Fe to a faster-migrating band that co-migrates with 59Fe-charged Tf only in the presence of citrate (lanes 7–11, open arrowheads). (B) Denaturation of 59Fe-PrP23-231 with guanidine hydrochloride (GdnHCl) releases 59Fe completely (lanes 1 and 2), whereas reduction of disulfides with DTT either after or before exposure to 59Fe has no effect on PrP23-231-iron interaction (lanes 3 and 4).

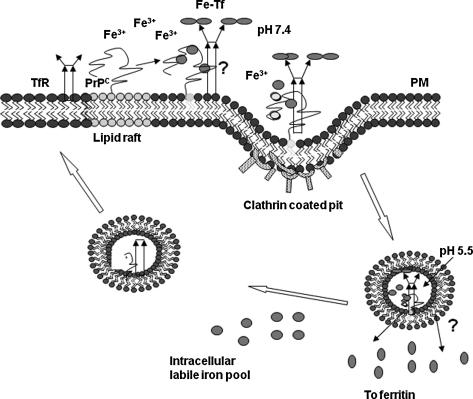

Despite uncertainties about the affinity and binding site(s) of PrPC for iron, recent studies leave little doubt that PrPC plays a significant role in cellular iron metabolism (204, 205). Observations on human neuroblastoma cells show that overexpression of PrPC increases the cellular labile iron pool (LIP) and iron saturation of ferritin, whereas pathogenic and nonpathogenic mutations of PrP overexpressed to the same extent as PrPC alter cellular LIP and ferritin iron levels in a manner that is specific to each mutation (205). The difference in the iron content of these cells is maintained when they are exposed to excess extracellular iron, suggesting a dominant role for PrPC in cellular iron uptake and transport (205). Whether PrPC mediates iron uptake by a novel pathway or modulates the conventional pathway(s) of iron uptake through Tf/TfR-mediated endocytosis is unclear from published reports. However, stimulation of endocytosis by a PrPC-specific antibody increases intracellular iron stores, whereas expression of anchorless PrPC that is not expressed on the plasma membrane abolishes this effect, suggesting an active role for PrPC in iron uptake at the plasma membrane (205). It is clear that PrPC is not involved in iron efflux from cells, reinforcing the idea that it influences iron uptake, not export (100, 205). The possible mechanism by which PrPC modulates cellular iron levels is unknown at present. It is also possible that extracellular iron induces the movement of PrPC from detergent-insoluble membrane domains, where it normally resides, to the proximity of TfR, as suggested for copper (147). Here it may enhance the binding of iron to Tf, the binding of iron-loaded Tf to its receptor, or stimulate the endocytosis of Tf/TfR complex by direct or indirect mechanisms (Fig. 11). Conflicting reports suggest that PrPC undergoes clathrin-mediated endocytosis after associating with a transmembrane protein through its N-terminal domain (200) or through a caveolae-mediated endosomal pathway (170). It is interesting to note that PrP co-localizes with Tf and TfR within the endosomes, an observation suggestive of a functional association rather than co-residence due to a common mode of endocytosis (170). Other proteins known to modulate iron uptake by regulating the interaction of the Tf/TfR complex include hereditary hemachromatosis protein (HFE), although HFE decreases iron uptake in contrast to PrPC, which has the opposite effect (232). It also is possible that PrPC functions as a ferric reductase to facilitate the transport of Fe3+ iron released from Tf to cytosolic ferritin, as described for copper, with which PrPC is believed to reduce Cu2+ before transfer to Cu1+-specific trafficking proteins in the cytosol (147). Figure 11 represents possible pathways of uptake and transport of iron by PrPC.

FIG. 11.

Possible mechanisms of iron uptake by PrPC. Cell-surface PrPC may bind iron from the extracellular milieu and mediate its uptake directly by endocytosis, or modulate the uptake of iron by the Tf/TfR complex. Alternately, PrPC may mediate the transport of iron across the endosomal membrane by functioning as a ferric reductase. Iron transported to the cytosol enters the labile iron pool for metabolic processes, and excess is stored within ferritin in a relatively inert form.

The functional role of PrPC in iron uptake is further exemplified by PrP−/− mice that contain a targeted deletion of PRNP, the gene encoding PrP, and do not express PrPC. As noted in cell models, lack of PrPC expression induces a phenotype of iron deficiency in PrP−/− mice relative to matched wild-type controls (204). The levels of iron in the plasma, liver, spleen, and brain of PrP-/- mice are significantly lower than those in wild-type controls, and neuronal TfR levels are upregulated, demonstrating a state of neuronal iron deficiency. It is noteworthy that the absence of PrPC in PrP−/− mice decreases the transport of iron from the intestinal epithelium to the bloodstream and hampers subsequent uptake by cells of all major organs, including hematopoietic progenitor cells (204). Analysis of other hematologic parameters shows minimal differences in the number of red cells and hematocrit, but a significant increase in reticulocytes in the peripheral blood of PrP−/− mice relative to wild-type controls. Likewise, a proliferation of red cell precursors occurs in the bone marrow of PrP−/− animals, indicating an attempt by the iron homeostatic machinery to compensate for the iron deficiency in these animals. The iron-deficient phenotype of PrP−/− mice is reversed by expressing wild-type PrPC in the PrP−/− background, reinforcing the idea that PrPC plays a functional role in iron uptake and transport (204). Because the iron deficiency of PrP−/− mice is largely compensated and the animals live normally except for specific deficiencies mainly restricted to the central nervous system (127, 187, 191, 222), we believe that PrPC modulates the function of other iron-uptake proteins or is involved in a parallel pathway of iron uptake that compensates for its absence. Because distinct iron-modulating proteins are involved in mediating iron transport from the intestine and uptake by hematopoietic cells, the hypothesis that PrPC acts at a point downstream from these pathways deserves further consideration. Further investigations are necessary to understand the underlying mechanism of iron transport and the identity of iron-modulating proteins that interact with PrPC to influence iron levels in different cell types.

C. The antioxidant activity of PrP

PrPC is believed to protect cells against oxidative stress, thus functioning as an antioxidant. The underlying mechanism of this activity, however, has remained elusive. It has been reported that neurons devoid of PrPC expression show increased sensitivity to superoxide anions (31, 188), hydrogen peroxide (240), manganese (46), and copper toxicity (30) compared with wild-type controls. In PrP−/− mice that lack PrP expression, markers of oxidative stress are evident in the brain (244). Likewise, loss of PrPC function due to conversion to the PrPSc form may account for the increase in protein damage and markers of oxidative stress observed in sCJD and scrapie-infected mouse brains (64, 245). Continued oxidative stress is likely to deplete glutathione, a potent free-radical scavenger in the brain, thus intensifying toxicity (57).

Conflicting reports on the mechanism of the antioxidant function of PrPC suggest that it influences the activity of cytosolic Cu/Zn SOD, or functions as an SOD enzyme itself (32, 96, 190). It remains plausible, though, that PrPC modulates the activity of Cu/Zn-SOD indirectly by functioning as a copper-uptake and -transport protein, as observed in cultured cells incubated with radioactive copper, in which PrPC modulates copper incorporation into the active site of this enzyme (32). Other studies suggest that association of PrPC with copper in the octapeptide repeat region induces a conformational change in the C-terminal region that is considered important for its antioxidant property (27, 95, 146). Furthermore, PrPC is believed to quench extracellular free radicals, an activity that may account for its function as an antioxidant (154).

Collectively, these observations suggest that PrPC protects cells against oxidative stress, although the mechanisms sustaining this action are still elusive.

IV. Redox Homeostasis and Prion-Disease Pathogenesis

A. PrP and metal interaction: the ironic connection

In addition to serving as physiologic ligands for PrPC, copper and iron have significant pathologic implications because of their redox-active nature (150, 158). Recent studies demonstrate that copper-bound PrPC is capable of accepting and donating electrons cyclically, although the significance of these observations is not clear (196). Likewise, the influence of the PrPC–copper interaction on the generation of PrPSc is controversial. In some experimental paradigms, copper induces PrPSc formation, whereas in others, it has the opposite effect. For example, exposure of purified PrPC to copper induces its conversion to a form similar to PrPSc (177), whereas addition of copper to synthetic prions slows the formation of amyloid, indicating an inhibitory role (21, 159). When added to scrapie-infected cells, copper reduces the accumulation of PrPSc (91), whereas in scrapie-infected mouse brains, copper is associated with PrPSc deposits, and chelation of copper delays the onset of prion disease (201). In addition, copper induces the interconversion of PrPSc strains in vitro from clinically distinct subtypes of CJD, most likely by altering their metal-ion occupancy and secondary structure (230). Furthermore, humans carrying an expansion of the copper-binding octapeptide repeat region are more prone to a familial form of CJD, whereas deletion of these repeats has no effect (62, 211), suggesting a direct role of copper levels with prion-disease pathogenesis.

Some of the contradictory results pertaining to beneficial or harmful effects of copper noted earlier can be explained by observations from in vitro studies in which copper inhibits amplification of PrPSc from purified brain-derived and recombinant PrPC by stabilizing the structure of the latter (93, 143). At the same time, copper is known to enhance the β-sheet structure when added to preformed PrP fibrils, increasing their overall PrPSc content (21). Thus, copper could delay or augment disease pathogenesis, based on the time within the incubation period when it is introduced. Alternately, these disparate findings could be explained by the redox-active nature of copper and the metal content of PrPC. Purified brain-derived and recombinant PrPC are associated with little copper or iron and are not likely to generate free radicals in response to added copper. Preformed fibrils, conversely, are associated with both copper and iron and are likely to aggregate further when exposed to added copper because of the initiation of the Fenton reaction (124).

Cell-associated PrPC responds to redox-active metals in a similar manner. Exposure of cells expressing PrPC to a source of redox-iron causes aggregation of PrPC in association with cellular ferritin, and the complex mimics PrPSc in several biochemical characteristics (12). It is likely that interaction of metal-associated PrPC on the cell surface with a source of redox-iron initiates the Fenton reaction, resulting in its aggregation. These aggregates are diverted to lysosomes for degradation where they come into contact with ferritin and assume a redox-active nature because of the associated iron and copper. The aggregated PrP–ferritin complexes initiate the generation of additional PrP–ferritin aggregates, propagating PrPSc-like conformation within the cells (12). Cells exposed to hemin, an iron-containing compound, show a similar aggregation, internalization, and degradation of PrPC, demonstrating the sensitivity of PrPC to free radicals and the significance of metal-induced oxidative stress in prion-disease pathogenesis (123). It is interesting to note that a marginal increase in the concentration of redox-active copper or iron in the culture medium of PrPC-expressing cells results in accumulation of PrPSc-like aggregates with the redox activity of the metal preserved, suggesting that PrP co-aggregates with the metal and becomes redox active (12, 118, 154). A similar aggregation of α-synuclein is noted when it is exposed to ferrous chloride in vitro or when expressed in cells (69, 80, 160), suggesting that protein aggregation by redox-active metals is not specific to PrPC. A partial list of neurodegenerative conditions associated with metal-ion–induced protein aggregation is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Neurodegenerative Diseases Involving Metal-induced Protein Aggregation

| Protein involved | Metal | Disease |

|---|---|---|

| PrPC or PrPSc | Cu, Fe, Mn | Prion disorders |

| Aβ | Cu, Fe, Zn | Alzheimer's disease |

| SOD1 | Cu | ALS |

| α-Synuclein | Fe, Cu | Parkinson's disease |

The association of PrPSc with ferritin was also observed in sCJD-affected brain homogenates and mouse scrapie–infected cell lines ScN2a and SMB (144, 203). Interestingly, ferritin is not degraded by exposure to proteinase-K, and the interaction of ferritin with PrPSc is maintained in the presence of digestive enzymes (144, 203), raising the possibility that PrPSc is co-internalized by intestinal epithelial cells along with ferritin. In vitro experiments with the epithelial cell line Caco-2 suggest that the PrPSc–ferritin complex is indeed transported intact across a monolayer of these cells, suggesting an important role for ferritin in this process (144). Whether the interaction of PrPSc with ferritin is essential for its PK-resistant nature is not entirely clear. However, chelation of iron from prion disease–affected brain homogenates decreases the total amount of PK-resistant PrPSc, suggesting that iron is somehow involved in the stability of PrPSc (12).

A similar role for iron has been reported in scrapie-infected mouse neuroblastoma cells (ScN2a) that actively replicate mouse prions in culture. These cells show alteration of cellular iron homeostasis and increased susceptibility to iron-induced oxidative stress (60, 61). The total iron content and calcein chelatable iron pool in ScN2a cells is twofold lower, and unexpectedly, the activity of iron regulatory proteins IRE1 and 2 also is lower by 40% and 50%, indicating mismanagement of cellular iron homeostasis (61). Moreover, the levels of redox-active Fe2+ iron are higher in ScN2a cells, increasing their susceptibility to free radical–induced toxicity (61). Exposure of ScN2a cells to exogenous iron results in increased production of ROS, further supporting the idea that accumulation of PrPSc causes mismanagement of cellular iron homeostasis (60). GT-1 cells infected with scrapie show a similar response to exogenous iron, ruling out artifactual effects due to clonal selection of either cell line (60).

These studies suggest that the association of PrPC with copper and iron can have deleterious consequences under certain circumstances because of their redox-active nature. Perhaps the site and nature of PrP–metal interaction and the structure of PrPC itself are important underlying factors in this process, because the formation of β-sheet–rich aggregates on exposure to free radicals has been reported only for a few proteins such as PrPC and α-synuclein (215). Other major iron- and copper-binding proteins do not show this response. It is likely that sequestration of iron in PrPSc aggregates renders them redox active, thus accentuating the associated toxicity. Future investigations are necessary to understand this phenomenon fully.

B. Prion disorders and brain-iron homeostasis

The contribution of redox-active PrPSc aggregates and altered brain-iron homeostasis to prion-disease pathogenesis is further supported by observations in diseased human and animal brains. In human brains affected with vCJD, redox-active iron is detected in association with PrPSc plaques, along with iron- and ferritin-rich microglia in the region surrounding the plaque (171). Although the underlying mechanism leading to iron deposits is not clear, redox-active iron is likely to induce oxidative damage in the surrounding neuronal population (99, 132). Other reports indicate alteration of the activity of iron-regulatory proteins 1 and 2 and expression of iron-storage protein ferritin in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex of prion-infected mouse brains, suggesting a state of iron imbalance (107). This assumption is supported by observations indicating a consistent increase in total and redox-active Fe2+ iron, and paradoxically, a phenotype of iron deficiency in sCJD-affected brain tissue (203). As a consequence, major iron-uptake proteins Tf and TfR are upregulated to compensate for the deficiency, worsening the state of iron imbalance. The deficiency of iron is evident in Purkinje cells of sCJD brains, suggesting that the neuronal population is especially affected by this metabolic alteration. This phenotype of brain-iron deficiency develops during the incubation period and shows a direct correlation with PrPSc levels, supporting the hypothesis that PrPSc itself or PrPSc–ferritin aggregates sequester iron in a biologically unavailable form, resulting in a state of iron deficiency in the presence of excess iron (203). Because PrPSc-ferritin aggregates are themselves redox active, it is likely that once initiated, this complex propagates PrPSc accumulation and iron deficiency, worsening the state of iron dyshomeostasis and associated neurotoxicity. Figure 12 summarizes the possible mechanisms of iron-induced neurotoxicity in prion disease–affected brains.

FIG. 12.

A model of possible mechanisms of iron-mediated neurotoxicity in prion disorders. Free radicals generated from normal metabolic processes in the brain are normally detoxified by antioxidant enzymes and proteins, including PrPC. When the antioxidant capability of the brain is exceeded, free radicals are likely to react with PrPC-bound copper and iron and induce their aggregation to the PrPSc form that co-aggregates with ferritin and becomes redox active (12, 203). This causes further production of free radicals, resulting in a state of brain-iron imbalance. This increases the production of ROS, resulting in further aggregation of PrPC and neurotoxicity.

Although studies supporting imbalance of iron homeostasis as a significant contributing factor of prion-disease pathogenesis are limited, the observations noted here provide a viable means of developing a prophylactic and therapeutic strategy, both of which are lacking at this time. Equally strong evidence supporting other mechanisms of prion replication and disease-associated neurotoxicity exists, but has not been included in this review in an attempt to keep the focus limited to the redox activity of prion-disease pathogenesis.

V. Therapeutic Options

Investigations directed at possible therapeutic options for prion disorders are still at a formative stage and demand a clear objective and in-depth evaluation to design and test successfully possible therapies. Because all prion disorders except vCJD have a relatively long incubation period, effective treatment can be initiated much before clinical symptoms appear. Given the focus of this review, two possible avenues hold promise: (a) antioxidants and free radical scavengers (63, 139, 214), and (b) metal chelators (38, 65, 248). Limited studies conducted in this direction have been quite promising and are reviewed here.

A. Antioxidants

Studies on prion-infected cell and mouse models have provided useful information on the therapeutic potential of antioxidants. In cell models, both direct application of cell-permeable antioxidants and indirect methods to restore endogenous antioxidant levels have been tried (24). Flupirtine, a triaminopyridine compound, has become quite popular among researchers because it can act as an N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) antagonist without binding to NMDA receptors. This drug has the exceptional ability to normalize intracellular glutathione levels and restore oxidative balance within the cell, thereby combating accumulation of ROS and other free radicals. The associated upregulation of antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2 and the relatively favorable pharmacokinetic profile of flupirtine make it a promising therapeutic agent to treat prion disorders (151, 161, 168, 194). An equally promising agent is the nonpsychoactive cannabis constituent cannabidiol, by virtue of its antioxidant property, NMDA antagonism, reduction in glutamate release, and blockade of microglial migration and activation, all of which are detrimental factors that aggravate PrPSc-mediated neurotoxicity (55, 138). Similarly, the disaccharide trehalose, known for its ability to reduce Aβ-mediated toxicity by inhibiting its aggregation, also protects prion-infected cells from oxidative damage (18). Another effective agent is EUK-189, a potent Mn SOD/catalase mimetic, that reduces oxidative damage in prion-infected mouse models, as evidenced by reduction in nitrative damage to vital cellular proteins, prolongation of incubation time, and decreased spongiform change in the brains of terminally ill mice (24). Although a clinically viable antioxidant that can alleviate prion disease–associated neurotoxicity is lacking, these observations argue that counteracting oxidative stress may have therapeutic benefit in prion disease and provide the basis for future investigations in this area.

B. Metal chelators

Most of the strategies aimed at metal chelation are targeted toward copper because the association of iron with prion-disease pathogenesis is a relatively new observation (203). Contradictory observations have been reported for copper, in which both increased and reduced levels of brain copper have been implicated in disease-associated neurotoxicity. In an experimental paradigm in which the loss of neurons and astrogliosis was induced by introduction of copper into the dorsal hippocampus of rats, co-injection of a synthetic peptide corresponding to the octapeptide repeat domain of PrP (PrP59-91) that binds copper reduced neuronal death (42). With a similar premise, chelation of copper with d-penicillamine, a drug used routinely for treating Wilson disease, decreased brain-copper content of prion-infected mice by 30% and increased the incubation period, supporting the idea that increased levels of brain copper promote diseases (58, 201). However, contradictory reports suggest a protective role for copper in prion disorders. It was observed that neuroblastoma cells cultured in the presence of copper ions lost the ability to bind and internalize PrPSc, thereby evading infection and toxicity. A significant delay in the onset of clinical disease also was observed in scrapie-infected hamsters given a dietary supplement of copper (91), supporting these observations. It is likely that the protective effect of copper reflects internalization and degradation of PrPC on exposure to copper, the substrate for PrPSc generation, although a direct effect on the generation of PrPSc cannot be ruled out because inhibition of PrPSc accumulation is observed after the addition of copper in vitro to PMCA reactions, a procedure used to amplify PrPSc (39, 159).

The involvement of redox iron and imbalance of brain-iron homeostasis in prion disease–associated neurotoxicity is a relatively new observation, and the effect of iron chelation on disease pathogenesis has not been tried in cell or mouse models. However, chelation of iron from prion disease–affected human and mouse brain homogenates in vitro reduces the amount of disease-associated PrPSc, suggesting that this method may be used prophylactically to decrease prion infectivity in consumable products (12). A similar reduction of PrPSc levels in vivo may prove useful in decreasing PrPSc load, although optimal iron chelators that are nontoxic at therapeutic doses and can cross the blood–brain barrier effectively have not been developed. Studies in MPTP mouse models of Parkinson disease report significant benefit from the concomitant administration of blood–brain barrier–permeable iron chelator VK-28 [5-(4-(2-hydroxyethyl) piperazin-1-yl (methyl)-8-hydroxyquinoline] and its derivative M30 [5-(N-methyl-N-propargyaminomethyl)-8-hydroxyquinoline], providing direct evidence for the involvement of iron in disease pathogenesis (253). However, the applicability of these compounds in prion disease–associated neurotoxicity is yet to be investigated. Although apparently encouraging, the reduction of brain iron may aggravate the disease by increasing iron uptake by surviving cells, warranting caution in using such compounds. Restoring brain-iron homeostasis in diseased brains is therefore a daunting task, because complex biochemical pathways are involved in iron metabolism.

However, iron chelation as a means to reduce the toxicity associated with its redox-active nature has been pursued actively in diseases like AD and PD. Several chelators have been tried, the most prominent ones being desferrioxamine (DFO) and 5-chloro-7-iodo-quinolin-8-ol (Clioquinol) (90). Although DFO showed some success in studies with AD patients, it does not cross the blood–brain barrier effectively and is toxic in therapeutic doses, making it an unsuitable drug for the treatment of AD or prion disorders. Clioquinol is an antibiotic that binds to Zn, Cu, and iron, and crosses the blood–brain barrier effectively (90). Structurally, Clioquinol is related to quinacrine analogues that have been used effectively in other studies on prion disease–affected experimental models and in human trials and could be a safe drug for in vivo use (152). The use of Clioquinol in scrapie-infected hamsters increases the incubation time modestly, suggesting a future potential for the use of this drug in humans (175). Likewise, promising results were observed when Clioquinol was administered orally to mouse models of AD and PD (38, 105).

The use of antioxidants and metal ion chelators are the major approach toward developing therapies for prion disorders; however, most of the drugs are effective when administered at a very early stage of the disease. The imposed problem is that prion disorders in most cases go unnoticed at early stages and can be diagnosed much later when most of the damage and neurodegeneration have occurred. Hence, proper treatment of prion disorders also demands a better diagnostic tool to allow detection at an early stage that can complement the use of reported drugs with greater efficiency.

VI. Summary and Perspective

The complexity and multiplicity of factors involved in the pathogenesis of prion disorders has hampered our progress toward the development of a therapeutic strategy, although each report brings us closer to an answer. Collective evidence from different models suggests a key role for PrPSc, a β-sheet–rich form of the cell-surface glycoprotein PrPC, as the principal neurotoxic element. Equally strong data support loss of protective function of PrPC as a significant contributing factor in disease-associated neuronal death. Several mechanisms of neurotoxicity have been suggested for PrPSc, and an equally diverse set of functions has been proposed for PrPC, the loss of which could induce neuronal death. Consensus on either of these issues is still lacking. Recent reports on the association of PrPC with redox-active metals such as copper and iron provide a new perspective on the mechanisms underlying prion disease–associated neurotoxicity. Human PrPC binds to five copper ions with a relatively high affinity and mediates the uptake of copper ions from the extracellular mileu. The octapeptide repeat region of PrPC also functions as a reductase, facilitating the transport of copper from the endosomes to cytosolic carrier proteins. The binding site and affinity of PrPC for iron is less well defined, although it is clear that PrPC mediates the uptake and transport of iron, and lack of PrPC induces a phenotype of iron deficiency in PrP−/− mice. Thus, the association of PrPC with copper and iron has significant physiologic implications. Conversely, the inherently redox-active nature of these metals increases the suscptibility of PrPC to free radicals that causes its aggregation to a form resembling PrPSc in several characteristics. The PrPSc thus formed co-aggregates with ferritin and associated iron, rendering it redox active. This complex induces the aggregation of additional PrPC to PrPSc, and the process continues. The lack of bioavailability of sequestetred iron results in a state of iron deficiency, resulting in brain-iron imbalance and associated neurotoxicity. These observations suggest a significant role for metal-induced oxidative stress in prion disease–associated neurotoxicity, and the prospect of using antioxidants and iron chelators such as Clioquinol that can cross the blood–brain barrier effectively as useful therapeutic agents. However, given the complex nature of brain-iron metabolism, chelation per se may provide only limited help or even worsen the situation. Future investigations are necessary to resolve this issue, keeping in mind other aspects of prion-disease pathogenesis that are not discussed here due to the specific focus of this review.

Abbreviations Used

- 8OHG

8-hydroxyguanosine

- Aβ

amyloid-β

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- ADAM10 and ADAM17

members of the disintegrin and metallopeptidase family

- ALS

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- Bcl-2

family of antiapoptotic proteins that derive their name from B-cell lymphoma 2 protein

- BSE

bovine spongiform encephalopathy

- CJD

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- DFO

desferroxamine

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- 59Fe

radioactive iron

- Fe2+

ferrous iron

- Fe3+

ferric iron

- FFI

fatal familial insomnia

- GPI

glycosylphosphatidylinositol

- GSS

Gerstmann-Straussler-Scheinker disease

- GT-1

a hypothalamic neuronal cell line

- HAE

4-hydroxyalkenal

- HD

Huntington's disease

- HFE

hereditary hemachromatosis protein

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- IRE

iron-responsive element

- IRP 1 and 2

iron-responsive proteins 1 and 2

- LIP

labile iron pool

- MDA

malondialdehyde

- Mn2+

manganese

- N2a

mouse neuroblastoma cell

- NF-κβ

nuclear factor κB (transcription factor)

- Ni2+

nickel

- NMDA

N-methyl-d-aspartate

- NOS

nitric oxide synthase

- OH•

hydroxyl radical

- PD

Parkinson's disease

- PK

proteinase-K

- PMCA

protein-misfolding cyclic amplification

- PRNP

gene encoding PrP

- PrP−/−

mice lacking PrP expression

- PrPC

prion protein

- PrPC-GFP

PrPC tagged with green fluorescent protein

- PrPSc

PrP-scrapie

- RK13A

rat kidney cell line

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- ScN2a

scrapie infected mouse neuroblastoma cell

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecylsulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- SMB

mouse brain cell of mesenchymal origin

- SOD

Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase

- Tf

transferrin

- TfR

transferrin receptor

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- Zn2+

zinc

Footnotes

Reviewing Editors: Andrew F. Hill, Sophie Mouillet-Richard, Jesús R. Requena, and Jason Shearer