Abstract

Background

A common polymorphism, C776G, in the plasma B12 transport protein transcobalamin (TC), encodes for either proline or arginine at codon 259. This polymorphism may affect the affinity of TC for B12 and subsequent delivery of B12 to tissues.

Methods

TC genotype and its associations with indicators of B12 status, including total B12, holotranscobalamin (holoTC), methylmalonic acid, and homocysteine, were evaluated in a cohort of elderly Latinos (N=554, age 60–93y) from the Sacramento Area Latino Study on Aging (SALSA).

Results

The distribution of TC genotypes was 41.3% homozygous reference (776CC) and 11.6% homozygous variant (776GG). No differences between the homozygous genotypes were observed in total B12, holoTC, methylmalonic acid, or homocysteine. The holoTC/total B12 ratio was lower in the 776GG group compared with the 776CC group (p=0.04). Significant interactions of TC genotype with total B12 (p=0.04) and with holoTC (p≤0.03) were observed such that mean homocysteine concentrations and the odds ratios for hyperhomocysteinemia (>13 µmol/L) were higher in the 776CC subjects compared with all carriers of the G allele (776CG and 776GG combined) when total B12 (<156 pmol/L) or holoTC (<35 pmol/L) were low.

Conclusions

This population of older Latinos has a lower prevalence of the TC 776GG variant than reported for Caucasian populations. The association between vitamin B12 and homocysteine concentrations is modified by TC 776 genotype. It remains to be determined if the TC C776G polymorphism has a significant effect on the hematological and neurological manifestations of B12 deficiency or on vascular and other morbidities associated with hyperhomocysteinemia.

Keywords: Transcobalamin, polymorphism, homocysteine, vitamin B12, Hispanic elderly

INTRODUCTION

Vitamin B12 (B12) in plasma is bound to two distinct transport proteins, haptocorrin and transcobalamin (TC) (Chanarin, 1969; Green and Miller, 2007). Of these two proteins, only TC is known to play a role in both B12 absorption and cellular delivery. Dietary B12 is bound to TC in the ileal enterocyte and the TC-B12 complex (holoTC) enters the circulation. The circulating holoTC binds a specific TC receptor that is found on all tissues and is taken into the cell through endocytosis of the holoTC-receptor complex (Quadros et al., 2009). Thus, holoTC represents the fraction of total plasma B12 available for uptake into tissue. Accordingly, holoTC is considered to be a potential indicator of B12 status both independently and in conjunction with total B12 and other biochemical indicators of status (Ulleland et al., 2002; Refsum et al., 2006; Nexo et al., 2002; Herrmann et al., 2003; Miller et al., 2006; Garrod et al., 2008).

Several single nucleotide polymorphisms have been identified in the TC gene (gene designation: TCN2) (Li et al., 1994; Namour et al., 1998; Namour et al., 2001; Afman et al., 2002). The most common is a cytosine-to-guanine substitution at base position 776 of the genomic DNA sequence (776C>G). This substitution encodes for arginine in place of proline at codon 259 of the amino acid sequence. It is unclear if this amino acid substitution affects the structure and function of the protein (Namour et al., 1998; Namour et al., 2001; Afman et al., 2002; Wuergas et al., 2006). The prevalence of the homozygous variant form of TC (776GG) is high, with reported estimates in different populations ranging from 3–42% (Bowan et al., 2004; Gueant et al., 2007), which has led investigators to assess its influence on indicators of B12 status. Typically, no significant difference is found in total serum B12 concentrations among the TC 776 genotypes. In contrast, the 776GG variant has consistently been associated with lower serum or CSF levels of holoTC compared to the homozygous reference variant (776CC) (Afman et al., 2002; Wans et al., 2003; McCaddon et al., 2004; Zetterberg et al., 2003; von Castel-Dunwoody et al., 2005; Miller et al., 2002). The 776GG variant has also been associated with higher methylmalonic acid, a metabolite that becomes elevated in B12 deficiency (Miller et al., 2002; Fredriksen et al., 2007), a lower percentage of total B12 bound to TC (holoTC/B12 ratio) (Miller et al., 2002), and lower concentrations of TC with no B12 bound (apoTC) (Namour et al., 1998; Namour et al., 2001; Afman et al., 2002).

Homocysteine, an independent risk factor for vascular disease and related disorders (Refsum et al., 1998), is elevated in B12 deficiency. It has been reported that individuals heterozygous for the TC 776 variant (776CG) have higher homocysteine concentrations than individuals homozygous for either the reference or variant forms (Namour et al., Namour and Gueant, 2001). This remains to be confirmed, however, and more typically no difference in homocysteine levels is observed among the TC genotypes (Afman et al., 2002; von Castel-Dunwoody et al., 2005; Miller et al., 2002; Fredriksen et al., 2007; McCaddon et al., 2001; Zetterberg et al., 2002). A notable exception is the observation by Lievers et al. (2002) of a significant interaction between total B12 concentrations and TC genotype; the 776CC reference was associated with lower total plasma homocysteine than the 776GG variant when total B12 was greater than 300 pmol/L. This suggests that the association between B12 concentration and homocysteine is modified by TC 776 genotype and that plasma homocysteine concentrations may be more responsive to dietary B12 or B12 supplements in carriers of the 776CC reference compared with carriers of the 776GG variant.

In the present study, we examined associations between TC 776 genotype and indicators of B12 status in a cohort of community-dwelling older Hispanics participating in the Sacramento Area Latino Study on Aging (SALSA). We also determined if TC 776 genotype serves as an effect modifier of the associations between indicators of B12 status and homocysteine and methylmalonic acid concentrations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

The original SALSA study population consisted of a representative sample of community-dwelling older adults (age ≥60y) of Latino ancestry residing in Sacramento, CA, and surrounding Northern California communities (n=1789). Subjects were recruited over a period of 18 months beginning in February 1998. The details of sampling and recruitment have been described elsewhere (Wu et al., 2002; Haan et al., 2003). Approximately five years after initial recruitment, additional blood samples were collected from 834 subjects and made available for genomic DNA isolation and genotyping. Of these 834, baseline holoTC and total B12 measures were available from 554 subjects for the present study. Subject recruitment and study procedures for the SALSA study were approved by the Human Subjects Review Committee at the University of California, Davis, and written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Sample Processing and Analysis

Fasting blood samples were collected from all subjects during home visits. The blood was transported on ice to the University of California Davis Medical Center Clinical Laboratory for processing within 4 h of collection. Plasma and serum were isolated and stored at −80 °C until analysis. Total plasma vitamin B12 concentrations were determined by radioassay Quantaphase II; BioRad Diagnostics, Hercules, CA); plasma holoTC by monoclonal antibody capture assay (HoloTC RIA; Axis-Shield, Oslo, Norway); plasma methylmalonic acid by tandem mass spectrometry at ARUP Laboratories, Salt Lake City, Utah (Kushnir et al., 2001); total plasma homocysteine by HPLC with post-column fluorescence detection (Gilfix et al., 1997); red blood cell (RBC) folate by automated chemiluminescence assay (ACS 180: Chiron Diagnostics now Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics], Tarrytown, NY); and serum creatinine by the Jaffe rate reaction method using a SYNCHRON LX20 instrument (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA). Inter-assay coefficients of variation for each of the assays are: total B12, 4.7%; holoTC, 5.7%; homocysteine, 4.2%; methylmalonic acid, 5.8%; RBC folate, 10%; and creatinine 3.3%. Cutoff values for low (deficient) or elevated plasma concentrations used in this study were: total B12 <156 pmol/L (reference value used by the UC Davis Medical Center Clinical Laboratory, Sacramento, CA, based on 100% specificity for clinically diagnosed B12 deficiency); holoTC <35 pmol/L (Herrmann et al., 2003; Lindgren et al., 1999); homocysteine >13 µmol/L (Jacques et al., 1999); and methylmalonic acid >350 nmol/L (Clarke et al., 2003).

DNA was isolated from EDTA whole blood using QIAamp DNA Blood Maxi Kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). TC 776 genotype was determined by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), using an Eppendorf Mastercycler (Brinkmann, Westbury, NY), and restriction enzyme digest as previously published (Miller et al., 2002). The PCR protocol was modified to shorten the assay time as follows: 1) bringing of lid temperature to 102 °C; 2) initial denaturation (94 °C, minutes); 3) 34 cycles of denaturation (94 °C, 1 minute), annealing (64 °C, 1 minute), and extension (72 °C, 1 minute); 4) final extension (72 °C, 7 minutes).

Statistical Analyses

TC genotype and allele frequencies with Clopper-Pearson exact 95% confidence intervals were calculated. Chi-square analysis was used to determine if the TC genotypes were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Mean metabolite values were compared among the TC genotypes using Scheffe’s test. Sex distribution and percentage of subjects with low or high metabolite levels were compared among the TC genotypes by chi-square analysis. Interactive effects of TC genotype and total B12 (nominally divided into groups of < and ≥156 pmol/L) and holoTC (nominally divided into groups < and ≥35 pmol/L) on homocysteine and methylmalonic acid levels were assessed by 2-factor ANOVA. Due to the small number of subjects in the 776GG group, the 776CG and 776GG genotypes were combined into one group and compared with the 776CC reference group for the 2-factor ANOVA. Because the distributions of homocysteine and methylmalonic acid did not conform to a Gaussian distribution (tailing toward higher values), these variables were natural log transformed before analysis. In secondary analyses, logistic regression was carried out to determine the odds ratios (95% C.I.) for elevated homocysteine (>13 µmol/L) for the 776CC group compared with the combined 776CG/776GG group, for total B12 <156 pmol/L compared with total B12 ≥156 pmol/L, for holoTC <35 pmol/L compared with holoTC ≥35 pmol/L, and for the interactions between TC 776 genotype and total B12 or holoTC. For both the 2-factor ANOVA and logistic regression analyses, we controlled for confounding by age, sex, RBC folate, and creatinine. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05.

RESULTS

The characteristics of the study sample are presented in Table 1. The distribution of the TC polymorphism (with 95% C.I.) was: 776CC (homozygous reference), 41.3% (37.2, 45.6); 776CG (heterozygotes), 47.1% (42.9, 51.4); and 776GG (homozygous variant), 11.6% (9.0, 14.5). The allele frequencies (95% C.I.) for 776C and 776G were 0.65 (0.62, 0.68) and 0.35 (0.32, 0.38), respectively. The distribution is within Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (X2=0.64, p=0.42). No significant difference in total B12 was observed among the genotypes. Mean holoTC in the 776GG group was lower than in the 776CC group, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (p=0.09). The difference in mean holoTC/B12 ratio was, however, significantly lower in the 776GG group compared with the 776CC group (p=0.01). There were no significant differences in homocysteine or methylmalonic acid levels among the genotypes, nor were there significant differences among the genotypes in percentages of subjects with low total B12 (<156 pmol/L), low holoTC (<35 pmol/L), high methylmalonic acid (>350 nmol/L), or high homocysteine (>13 µmol/L).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study sample grouped by transcobalamin 776 genotype*

| TC 776 Genotype | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Subjects | CC | CG | GG | |

| N | 554 | 229 | 261 | 64 |

| Frequency % (95% C.I.) | 41.3 (37.2, 45.6) | 47.2 (42.9, 51.4) | 11.6 (9.0, 14.5) | |

| Sex (% female) | 60 | 63 | 57 | 64 |

| Age (y) | 69 ± 6 | 69 ± 6 | 70 ± 6 | 69 ± 6 |

| Vitamin B12 (pmol/L) | 314 ± 128 | 316 ± 142 | 312 ± 121 | 316 ± 107 |

| B12 <156 pmol/L (%) | 8.5 | 9.6 | 7.7 | 7.8 |

| HoloTC (pmol/L) | 78 ± 32 | 80 ± 33 | 77 ± 33 | 70 ± 27 |

| HoloTC <35 pmol/L (%) | 8.5 | 8.3 | 9.6 | 4.7 |

| HoloTC/B12 Ratio (%) | 25.7 ± 0.1 | 26.5 ± 0.1 | 25.6 ± 0.1 | 22.8 ± 0.1** |

| MMA (nmol/L) | 239 ± 562 | 286 ± 841 | 204 ± 182 | 207 ± 134 |

| MMA >350 (%) | 10.3 | 10.4 | 9.0 | 16.7 |

| Hcy (μmol/L) | 10.4 ± 6.4 | 10.8 ± 9.1 | 10.2 ± 3.3 | 9.7 ± 3.3 |

| Hcy >13 μmol/L (%) | 12.3 | 12.7 | 12.6 | 9.4 |

| RBC Folate (ng/mL) | 509 ± 157 | 505 ± 153 | 513 ± 160 | 509 ± 158 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.2 |

Values are means ± SD, except for N, frequency, sex, and percentage below or above cutoff values.

Significantly different from 776CC group by Scheffe’s test (p=0.04).

Abbreviations: TC, transcobalamin; HoloTC, holotranscobalamin; MMA, methylmalonic acid; Hcy, homocysteine; RBC, red blood cell.

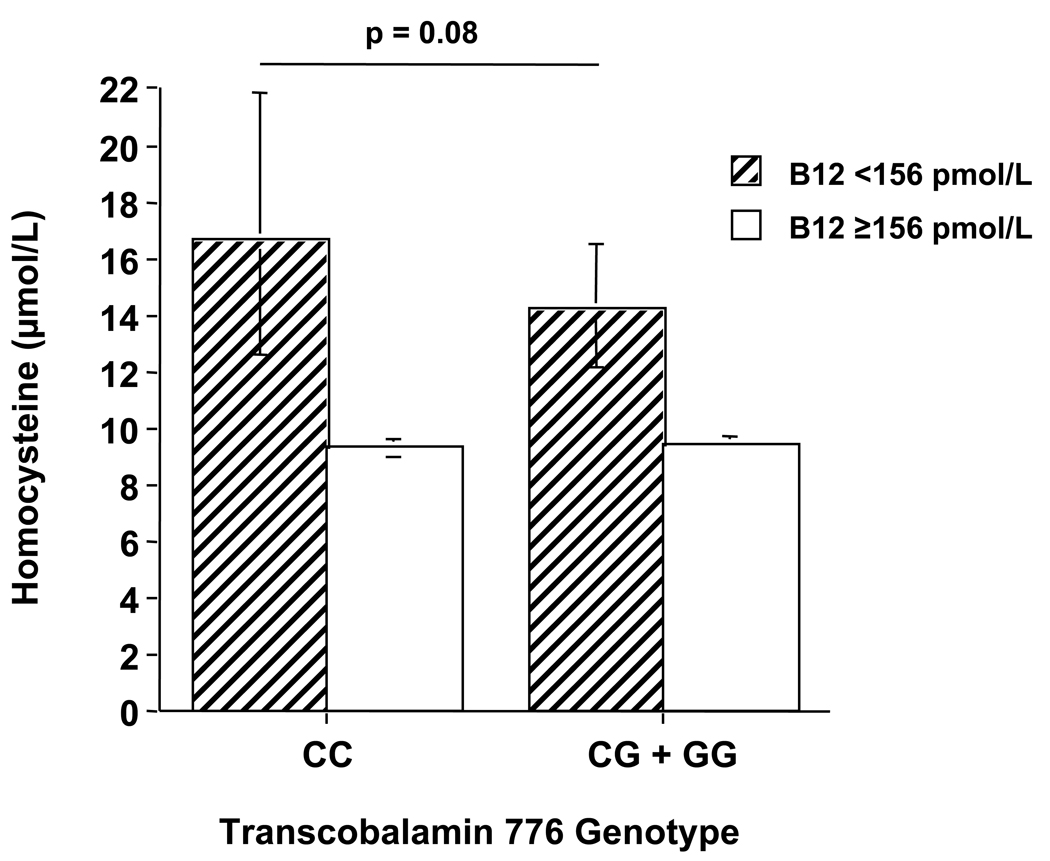

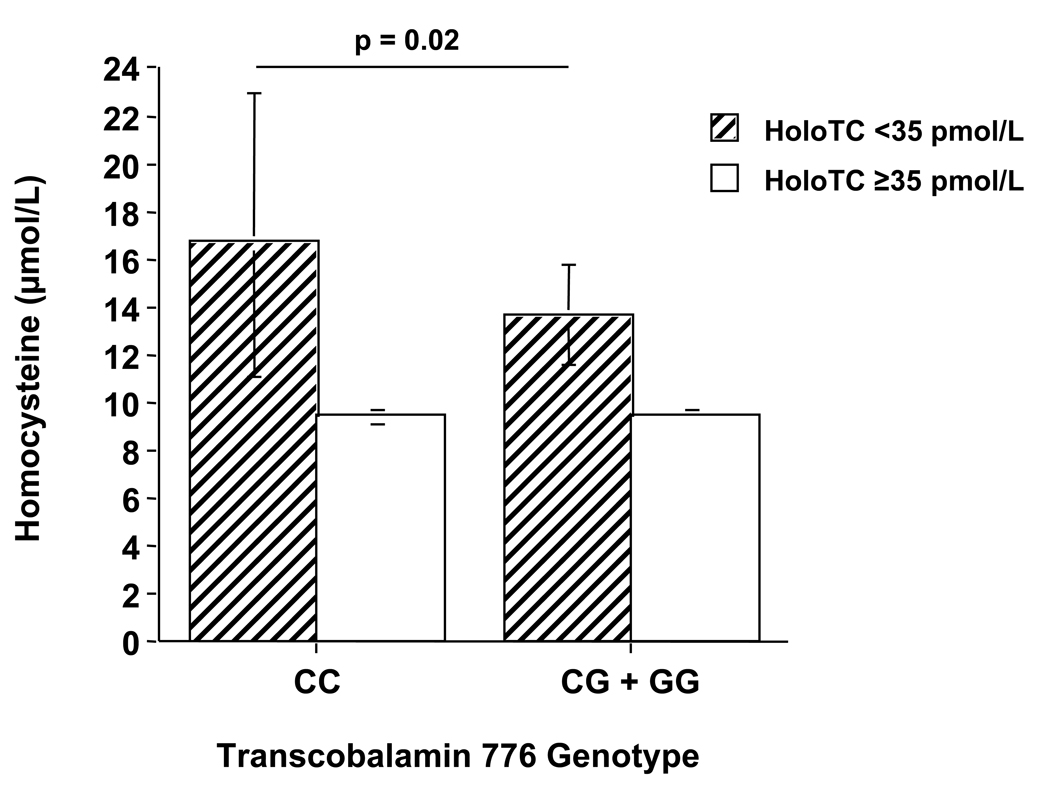

By 2-factor ANOVA, significant interactions between TC genotype and total B12 (p=0.04) and between TC genotype and holoTC (p=0.02) on homocysteine were observed. Subsequent analyses for subjects divided by low and high total B12 (< or ≥156 pmol/L) revealed that homocysteine was higher in the 776CC group compared with the combined 776CG/776GG group for those subjects with low total B12, though the difference did not reach statistical significance (p=0.08). No difference was observed in homocysteine between the genotype groups for subjects with high total B12 (Figure 1). For subjects divided by low and high holoTC (< or ≥35 pmol/L), homocysteine was significantly higher in the 776CC group compared with the combined 776CG/776GG group for those subjects with low holoTC (p=0.02), while no difference was observed between the genotype groups for subjects with high holoTC (Figure 2). No significant interactive effects were observed between TC genotype and either total B12 or holoTC on methylmalonic acid concentrations (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Interaction between total B12 and transcobalamin genotype on homocysteine. ANOVA for interaction between TC genotype (grouped as 776 CC and 776CG + 776GG) and total B12 (grouped as < and ≥ 156 pmol/L) was significant (p=0.04). Post-hoc comparisons of group means were made using Scheffe’s test, with controlling for age, sex, red blood cell folate, and creatinine. Bars represent geometric means with 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 2.

Interaction between holotranscobalamin (holoTC) and TC genotype on homocysteine. ANOVA for interaction between TC genotype (grouped as 776 CC and 776CG + 776GG) and holoTC (grouped as < and ≥ 35 pmol/L) was significant (p=0.02). Post-hoc comparisons of group means were made using Scheffe’s test, with controlling for age, sex, red blood cell folate, and creatinine. Bars represent geometric means with 95% confidence intervals.

Multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to assess the risk of having hyperhomocysteinemia (>13 µmol/L) between the TC 776 genotype groups, between subjects with low and high total B12 or low and high holoTC, and for the interaction between TC 776 genotype and total B12 or holoTC. For the model including low and high total B12 as an independent variable (Table 2, Model 1), the interaction between genotype and total B12 was significant (p=0.04), and subjects with low total B12 (p<0.001) or who were homozygous for the 776CC reference (p=0.05) had elevated odds ratios for hyperhomocysteinemia. Similarly, for the model including low and high holoTC as an independent variable (Table 2, Model 2), the interaction between genotype and holoTC was significant (p=0.03), and subjects with low total holoTC (p<0.001) or who were homozygous for the 776CC reference (p=0.03) had elevated odds ratios for hyperhomocysteinemia.

Table 2.

Odds ratios for elevated homocysteine (>13 μmol/L)**

| Model | OR (95% C.I.) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Model 1: | ||

| 776CC vs 776CG+776GG | 18.8 (1.04, 339) | 0.05 |

| Total B12 <156 vs ≥156 pmol/L | 220 (14.7, 3310) | <0.001 |

| TC Genotype * Total B12 | 5.41 (1.08, 27.0) | 0.04 |

| Model 2: | ||

| 776CC vs 776CG+776GG | 27.9 (1.33, 584) | 0.03 |

| HoloTC <35 vs ≥35 pmol/L | 227 (13.7, 3760) | <0.001 |

| TC Genotype * HoloTC | 5.99 (1.14, 31.6) | 0.03 |

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated controlling for confounding by age, sex, red blood cell folate, and creatinine.

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; C.I., confidence interval; TC, transcobalamin; HoloTC, holotranscobalamin; 776CC, transcobalamin homozygous wild-type; 776CG, transcobalamin heterozygotes; 776GG, transcobalamin homozygous variant.

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of the homozygous TC 776GG variant in the SALSA study sample was 11.6%, compared to 17.6% in a group of 239 Hispanic blood donors from the Mexico City area (Gueant et al., 2007). The reason for the difference in prevalence between these two study samples of the same ethnicity is unclear, but the latter study included subjects age 20–60y, while in SALSA they were ≥60y. In addition, it is not known whether these Hispanic cohorts are genetically similar. Reported prevalence of the 776GG variant in other ethnic groups ranges from ~3% in West Africans to ~11% in Italian Caucasians; ~13% in Afro-Americans; ~13% in Brazilians; ~20% in French, Scandinavian, and American Caucasians; and ~42% in ethnic Hans from Central China (Bowen et al., 2004; Gueant et al., 2007; Miller et al., 2002; Bottiger and Nilsson et al., 2007; Pereira et al., 2007; Alessio et al., 2007). Gueant et al. (2007) have proposed that environmental factors, in particular malaria, may have imposed selective pressures that contribute to the wide variation in prevalence of the TC 776 polymorphism in different populations.

There was no difference among the genotypes in total B12 concentration, consistent with previous reports (Namour et al., 2001; Zetterberg et al., 2003; von Castel-Dunwoody et al., 2005; Miller et al., 2002; McCaddon et al., 2001; Zetterberg et al., 2002). HoloTC was lower in the 776GG homozygous variant group, also consistent with reports by others (Afman et al., 2002; Wans et al., 2003; McCaddon et al., 2004; Zetterberg et al., 2003; von Castel-Dunwoody et al., 2005; Miller et al., 2002), although the difference in the SALSA study sample did not reach statistical significance. There was a significant difference among the genotypes in holoTC/B12 ratio, an observation we made previously in a study of primarily Caucasian individuals (Miller et al., 2002). It has been proposed that the TC 776 polymorphism may affect the intra-molecular folding of the transcobalamin protein resulting in reduced affinity for B12, though there is some disagreement on this issue (Namour et al., 1998; Namour et al., 2001; Afman et al., 2002; Wuergas et al., 2006). The lower holoTC/B12 ratio observed in individuals with the 776GG homozygous variant suggests that the G allele may indeed encode a protein with a significantly lower affinity for B12 than that encoded by the C allele. This may have important clinical implications based on our published finding that the holoTC/B12 ratio is associated with cognitive impairment in the SALSA population, particularly in those with elevated depressive symptoms (Garrod et al., 2008). A possible influence of TC genotype on the binding of holoTC to the TC receptor is also a potential consideration. This may now be investigated since the TC receptor has been cloned recently (Quadros et al., 2009).

The most novel findings in this study are the significant interactions between TC genotype and indicators of B12 status (total B12 and holoTC) on homocysteine concentrations. Differences in homocysteine were observed between the genotypes only in those subjects with low total B12 or low holoTC. Mean homocysteine concentrations and odds ratios for hyperhomocysteinemia were higher for 776CC homozygotes compared with carriers of the G allele (776CG and 776GG combined) when total B12 or holoTC were low. Lievers et al. (2002) made a similar, though not identical observation: individuals homozygous for the reference allele with total B12 ≥300 pmol/L had lower homocysteine than those with the variant allele. An interaction between TC genotype and holoTC on homocysteine, however, was not assessed in this study (Lievers et al., 2002). Together these findings suggest that TC 776 genotype is an effect modifier of the association between B12 status and homocysteine concentration, and that in those homozygous for the C allele, homocysteine levels may be more responsive to dietary B12 or B12 supplementation than in those with one or two G alleles. This may be an important consideration when evaluating the effect of B12 supplements or other modes of B12 intervention on plasma homocysteine. It is also important to note that since higher homocysteine was observed in the 776CC reference group when B12 status was low, the influence of the polymorphism on homocysteine levels may be more complicated than simply reduced affinity of TC for B12 caused by the presence of the G allele, as discussed above. It could be argued that the G allele is actually protective rather than deleterious when B12 status is low, which perhaps explains the relatively high prevalence of the variant form observed in different populations.

No significant difference was observed in methylmalonic acid concentrations among the TC genotypes, nor was a significant interaction detected between TC genotype and total B12 or holoTC on methylmalonic acid. This differs from our previous study in which we observed higher methylmalonic acid concentrations in the TC 776GG homozygotes compared with the TC 776CC homozygotes (Miller et al., 2002). This discrepancy between the two studies may be due to genetic, dietary or other environmental differences between Caucasian and Hispanic populations.

The influence of the TC 776 polymorphism on risk of clinical B12 deficiency remains to be determined. There are reports of direct associations between the 776 G allele and neural tube defects (Pietrzyk and Bik-Multanowski, 2003; Gueant-Rodriguez et al., 2003), spontaneous abortion (Zetterberg et al., 2002), cleft palate/lip (Martinelli et al., 2006), and autism (James et al., 2006). Other studies did not confirm the associations with neural tube defects and spontaneous abortion (Afman et al., 2002; Swanson et al., 2005; Brouns et al., 2008; Parle-McDermott et al., 2005). One report found that TC genotype may influence the age of onset of Alzheimer’s disease (McCaddon et al., 2004). TC genotype was not associated with congenital heart defects (Verkleij-Hagoort et al., 2008) and thrombosis (Zetterberg et al., 2002; Pereira et al., 2007). Notably, in none of these studies was the interaction between TC genotype and indicators of B12 status (i.e. total B12 or holoTC) on clinical risk considered. TC genotype might be an effect modifier of the associations between markers of B12 status and clinical disorders, as suggested by our finding of a significant interaction between holoTC and TC genotype on homocysteine concentrations in the SALSA study.

A final consideration is that our present findings were made in a population exposed to folic acid fortification, fully implemented in the United States as of January 1998 with the purpose of reducing the incidence of neural tube defects. We have shown elsewhere that in the SALSA study sample the prevalence of folate deficiency is very low (~1%) and that vitamin B12 status is now the dominant nutritional determinant of homocysteine levels (Green and Miller, 2005), at least in older adults. The present study suggests that in a folic acid fortified population, TC 776 genotype is an effect modifier of the associations between total B12 or holoTC concentrations and the risk of hyperhomocysteinemia, a condition which is associated with vascular disorders, cognitive dysfunction and dementia, birth defects, and osteoporosis Refsum et al., 1998, Selhub, 2008).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was financially supported by NIH AG12975; USDA 00-35200-9073; and a Freedom to Discover pilot grant from Bristol-Meyers Squibb Foundation, Inc. We thank Teresa Ortiz, RN, and the staff of the SALSA study for subject recruitment, phlebotomy, data collection, and data management. We acknowledge the contribution of Rebecca Cotterman in blood sample processing and biochemical assessments.

Footnotes

CONTRIBUTION OF AUTHORS

The authors made the following contributions to the study: MG Garrod performed the transcobalamin genotyping assays, participated in the statistical analysis and interpretation of the data, and was responsible for drafting the article with JW Miller; LH Allen (Principal Investigator of USDA grant 00-35200-9073) participated in the concept and design of the study and provided input into the final draft of the article; MN Haan (Principal Investigator of the SALSA study – NIH Grant AG12975) participated in the concept and design of the study, was responsible for recruitment of study subjects, acquisition of blood samples, data collection, and data management, participated in the statistical analysis and interpretation of the data, and provided input into the final draft of the article; R Green participated in the concept and design of the study and the interpretation of the data and provided input into the final draft of the article; JW Miller (Principal Investigator of the Bristol-Meyers Squibb Foundation pilot grant) participated in the concept and design of the study, supervised blood processing and biochemical analyses, participated in the statistical analysis and interpretation of the data, and was responsible for drafting the article with MG Garrod. The authors report no conflicts of interest with respect to this study.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Afman LA, Lievers KJA, van der Put NMJ, Trijbels FJM, Blom HJ. Single nucleotide polymorphisms in the transcobalamin gene: relationship with transcobalamin concentrations and risk for neural tube defects. Eur J Hum Genet. 2002;10:433–438. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alessio AC, Hoehr NF, Siqueira LH, Bydlowski SP, Annichino-Bizzacchi JM. Polymorphism C776G in the transcobalamin II gene and homocysteine, folate and vitamin B12 concentrations. Association with MTHFR C677T and A1298C and MTRR A66G polymorphisms in healthy children. Thromb Res. 2007;119:571–577. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bottiger AK, Nilsson TK. Pyrosequencing assay for genotyping of the transcobalamin II 776C>G polymorphism. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2007;67:247–251. doi: 10.1080/00365510601026542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowen RAR, Wong BYL, Cole DEC. Population-based differences in frequency of the transcobalamin II Pro259Arg polymorphism. Clin Biochem. 2004;37:128–133. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brouns R, Ursem N, Lindemans J, Hop W, Pluijm S, Steegers E, et al. Polymorphisms in genes related to folate and cobalamin metabolism and the associations with complex birth defects. Prenat Diagn. 2008;28:485–493. doi: 10.1002/pd.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chanarin I. The megaloblastic anemias. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clarke R, Refsum H, Birks J, Evans JG, Johnston C, Sherliker P, et al. Screening for vitamin B-12 and folate deficiency in older persons. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:1241–1247. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.5.1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fredriksen A, Meyer K, Ueland PM, Vollset SE, Grotmol T, Schneede J. Large-scale population-based metabolic phenotyping of thirteen genetic polymorphisms related to one-carbon metabolism. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:856–865. doi: 10.1002/humu.20522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garrod MG, Green R, Allen LH, Mungas DM, Jagust WJ, Haan MN, et al. Fraction of total plasma vitamin B12 bound to transcobalamin correlates with cognitive function in elderly Latinos with depressive symptoms. Clin Chem. 2008;54:1210–1217. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.102632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilfix BM, Blank DW, Rosenblatt DS. Novel reductant for determination of total plasma homocysteine. Clin Chem. 1997;43:687–688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green R, Miller JW. Vitamin B12 deficiency is the dominant nutritional cause of hyperhomocysteinemia in a folic acid-fortified population. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2005;43:1048–1051. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2005.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Green R, Miller JW. In: Handbook of Vitamins. Fourth Edition. Zempleni J, Rucker RB, McCormick DB, Suttie JW, editors. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor and Francis; 2007. pp. 413–457. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gueant J-L, Chabi NW, Gueant-Rodriguez R-M, Mutchinick OM, Debard R, Payet C, et al. Environmental influence on the worldwide prevalence of a 776C->G variant in the transcobalamin gene (TCN2) J Med Genet. 2007;44:363–367. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.048041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gueant-Rodriguez RM, Rendeli C, Namour B, Venuti L, Romano A, Anello G, et al. Transcobalamin and methionine synthase reductase mutated polymorphisms aggravate the risk of neural tube defects in humans. Neurosci Lett. 2003;344:189–192. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00468-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haan MN, Mungas DM, Gonzalez HM, Ortiz TA, Acharya A, Jagust WJ. Prevalence of dementia in older Latinos: the influence of type 2 diabetes mellitus, stroke and genetic factors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:169–177. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herrmann W, Obeid R, Schorr H, Geisel J. Functional vitamin B12 deficiency and determination of holotranscobalamin in populations at risk. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2003;41:1478–1488. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2003.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacques PF, Selhub J, Bostom AG, Wilson PW, Rosenberg IH. The effect of folic acid fortification on plasma folate and total homocysteine concentrations. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1449–1454. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905133401901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.James SJ, Melnyk S, Jernigan S, Cleves MA, Halsted CH, Wong DH, et al. Metabolic endophenotype and related genotypes are associated with oxidative stress in children with autism. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2006;141B:947–956. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kushnir MM, Komaromy-Hiller G, Shushan B, Urry FM, Roberts WL. Analysis of dicarboxylic acids by tandem mass spectrometry: high-throughput quantitative measurement of methylmalonic acid in serum, plasma, and urine. Clin Chem. 2001;47:1993–2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li N, Sood GK, Seetharam S, Seetharam B. Polymorphism of human transcobalamin II: substitution of proline and/or glutamine residues by arginine. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1219:515–520. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(94)90079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lievers KJA, Afman LA, Kluijtmans LAJ, Boers GH, Verhoef P, den Heijer M, et al. Polymorphisms in the transcobalamin gene: association with plasma homocysteine in healthy individuals and vascular disease patients. Clin Chem. 2002;48:1383–1389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lindgren A, Kilander A, Bagge E, Nexø E. Holotranscobalamin - a sensitive marker of cobalamin malabsorption. Eur J Clin Invest. 1999;29:321–329. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.1999.00446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martinelli M, Scapoli L, Palmieri A, Pezzetti F, Baciliero U, Padula E, et al. Study of four genes belonging to the folate pathway: transcobalamin 2 is involved in the onset of non-syndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:294. doi: 10.1002/humu.9411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCaddon A, Blennow K, Hudson P, Hughes A, Barber J, Gray R, et al. Transcobalamin polymorphism and serum holo-transcobalamin in relation to Alzheimer's disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;17:215–221. doi: 10.1159/000076359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCaddon A, Blennow K, Hudson P, Regland B, Hill D. Transcobalamin polymorphism and homocysteine. Blood. 2001;98:3497–3499. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.12.3497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller JW, Garrod MG, Rockwood AL, Kushnir MM, Allen LH, Haan MN, et al. Measurement of total vitamin B12 and holotranscobalamin, singly and in combination, in screening for metabolic vitamin B12 deficiency. Clin Chem. 2006;52:278–285. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.061382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller JW, Ramos MI, Garrod MG, Flynn MA, Green R. Transcobalamin II 775G>C polymorphism and indices of vitamin B12 status in healthy older adults. Blood. 2002;100:718–720. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0209. (Erratum in: Blood 100, 3483.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Namour F, Gueant J-L. Transcobalamin polymorphism, homocysteine, and aging. Blood. 2001;98:3499. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.12.3497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Namour F, Guy M, Aimone-Gastin I, de Nonancourt M, Mrabet N, Gueant J-L. Isoelectric phenotype and relative concentration of transcobalamin II isoproteins related to the codon 259 Arg/Pro polymorphism. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1998;251:769–774. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Namour F, Olivier J, Abdelmouttaleb I, Adjalla C, Debard R, Salvat C, et al. Transcobalamin codon 259 polymorphism in HT-29 and Caco-2 cells and in Caucasians: relation to transcobalamin and homocysteine concentration in blood. Blood. 2001;97:1092–1098. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.4.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nexo E, Hvas AM, Bleie O, Refsum H, Fedosov SN, Vollset SE, et al. Holo-transcobalamin is an early marker of changes in cobalamin homeostasis. A randomized placebo-controlled study. Clin Chem. 2002;48:1768–1771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parle-McDermott A, Pangilinan F, Mills JL, Signore CC, Molloy AM, Cotter A, et al. A polymorphism in the MTHFD1 gene increases a mother’s risk of having an unexplained second trimester pregnancy loss. Mol Hum Reprod. 2005;11:477–480. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pereira AC, Lourenco DM, Maffei FH, Morelli VM, Rollo HA, Zago MA, et al. A transcobalamin gene polymorphism and the risk of venous thrombosis. The BRATROS (Brazilian Thrombosis Study) Thromb Res. 2007;119:183–188. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pietrzyk JJ, Bik-Multanowski M. 776C>G polymorphism of the transcobalamin II gene as a risk factor for spina bifida. Mol Gen Metab. 2003;80:364. doi: 10.1016/S1096-7192(03)00131-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Quadros EV, Nakayama Y, Sequeira JM. The protein and the gene encoding the receptor for the cellular uptake of transcobalamin bound cobalamin. Blood. 2009;113:186–192. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-158949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Refsum H, Johnston C, Guttormsen AB, Nexo E. Holotranscobalamin and total transcobalamin in human plasma: determination, determinants, and reference values in healthy adults. Clin Chem. 2006;52:129–137. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.054619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Refsum H, Ueland PM, Nygård O, Vollset SE. Homocysteine and cardiovascular disease. Annu Rev Med. 1998;49:31–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.49.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Selhub J. Public health significance of elevated homocysteine. Food Nutr Bull. 2008;29(2 Suppl):S116–S125. doi: 10.1177/15648265080292S116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Swanson DA, Pangilinan F, Mills JL, Kirke PN, Conley M, Weiler A, et al. Evaluation of transcobalamin II polymorphisms as neural tube defect risk factors in an Irish population. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2005;73:239–244. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ulleland M, Eilertsen I, Quadros EV, Rothenberg SP, Fedasov SN, Sundrehagen E, et al. Direct assay for cobalamin bound to transcobalamin (holo-transcobalamin) in serum. Clin Chem. 2002;48:526–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Verkleij-Hagoort AC, van Driel LM, Lindemans J, Isaacs A, Steegers EA, Helbing WA, et al. Genetic and lifestyle factors related to the periconception vitamin B12 status and congenital heart defects: a Dutch case-control study. Mol Genet Metab. 2008;94:112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.von Castel-Dunwoody KM, Kauwell GPA, Shelnutt KP, Vaughn JD, Griffin ER, Maneval DR, et al. Transcobalamin 776C->G polymorphism negatively affects vitamin B-12 metabolism. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:1436–1441. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.6.1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wans S, Schuttler K, Jakubiczka S, Muller A, Luley C, Dierkes J. Analysis of the transcobalamin II 776C>G (259P>R) single nucleotide polymorphism by denaturing HPLC in healthy elderly: associations with cobalamin, homocysteine and holo-transcobalamin II. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2003;41:1532–1536. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2003.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu CC, Mungas D, Petkov CI, Eberling JL, Zrelak PA, Buonocore MH, et al. Brain structure and cognition in a community sample of elderly Latinos. Neurology. 2002;59:383–391. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.3.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wuergas J, Garau G, Gerenia S, Fedosov SN, Petersen TE, Randaccio L. Structural basis for mammalian vitamin B12 transport by transcobalamin. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006;103:4386–4391. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509099103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zetterberg H, Coppola A, D'Angelo A, Palmer M, Rymo L, Blennow K. No association between the MTHFR A1298C and transcobalamin C776G genetic polymorphisms and hyperhomocysteinemia in thrombotic disease. Thromb Res. 2002;108:127–131. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(03)00004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zetterberg H, Nexo E, Regland B, Minthon L, Boson R, Palmér M, et al. The transcobalamin (TC) codon 259 genetic polymorphism influences holo-TC concentration in cerebrospinal fluid from patients with Alzheimer disease. Clin Chem. 2003;49:1195–1198. doi: 10.1373/49.7.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zetterberg H, Regland B, Palmer M, Rymo L, Zafiropoulos A, Arvanitis DA, et al. The transcobalamin codon 259 polymorphism influences the risk of human spontaneous abortion. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:3033–3036. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.12.3033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]