Abstract

Mediation analysis is a newer statistical tool that is becoming more prominent in nutritional research. Its use provides insight into the relationship among variables in a potential causal chain. For intervention studies, it can define the impact of different programmatic components, and in doing so allow investigators to identify and refine a program’s critical aspects. We present an overview of mediation analysis, compare mediators with other variables (confounders, moderators and covariates) and illustrate how mediation analysis permits interpretation of the change process. A framework is outlined for the critical appraisal of articles purporting to use mediation analysis. The framework’s utility is demonstrated by searching the nutrition literature and identifying articles citing mediation cross referenced with nutrition, diet, food and obesity. Seventy-two articles were identified that involved human subjects and behavioral outcomes, and almost half mentioned mediation without tests to define its presence. Tabulation of the 40 articles appropriately assessing mediation demonstrates an increase in these techniques’ appearance and the breadth of nutrition topics addressed. Mediation analysis is an important new statistical tool. Familiarity with its methodology and a framework for assessing articles will allow readers to critically appraise the literature and make informed independent evaluations of works using these techniques.

Keywords: mediation analysis, critical review, nutrition literature

The word mediate comes from the Latin mediare ‘place in the middle,’ and mediation refers to a facilitator resolving a dispute between two parties. In the last ten years, mediation increasingly is used in another context related to study design, data analysis and interpretation of findings (1–3). The term is well used in that setting as mediation analysis assesses events between two variables or between an intervention and its outcomes.

Researchers from many fields, including nutrition, have stressed moving beyond evaluating only study efficacy to deconstruct how programs achieve their results (4–8). Mediation analysis can determine the impact of each link in a hypothetical chain of events and define the contribution of different program components. It provides an explicit check on an intervention’s theoretical underpinnings and whether the proposed change process was achieved. Importantly, mediation analysis helps researchers modify, improve, and make more cost-effective interventions by identifying and refining their critical components.

However, mediation analysis is a newer statistical technique. The Journal of the American Dietetic Association has been a vehicle to inform its readers about statistical concepts (9) and the application of evidence-based assessments (10). In that tradition, we describe mediation analyses and contrast mediators with others types of variables, such as a confounders, covariates and moderators. Basic statistical methods to assess mediation are reviewed and an analytic framework proposed to guide reading articles purporting to use mediation analysis. We illustrate the concepts with nutrition examples and apply the framework to recent nutrition publications. Our objective is to enhance readers’ ability to critically interpret the literature when investigators use these newer statistical tools.

METHODS

We searched Ovid MEDLINE(R) and PubMed using the terms mediation combined with nutrition, diet, obesity and food for the dates January 2006 through May 2008, expanded by reviewing the indices of prominent nutrition journals for relevant works. Titles and abstracts of citations, and articles involving humans and using physical activity, nutrition or other related behaviors as measures were accessed. For these works, at least two authors (CML, CAD or DLE) read the article and applied the proposed evaluation framework. When disagreements occurred, a third author read the work, and the consensus scoring was used.

MEDIATION AND RELATED MODELS

Mediation Uses Regression Analysis

In a simple cross-sectional observational study, different statistical methods can be used to compare groups. For example, if you wanted to understand how tooth decay varies by sweetened beverage intake, individuals could be partitioned into those who do and do not drink sweetened beverages. The number of cavities for each group could be calculated and their means directly compared with an independent t-test to determine the probability or p value that the observed difference could have occurred by chance.

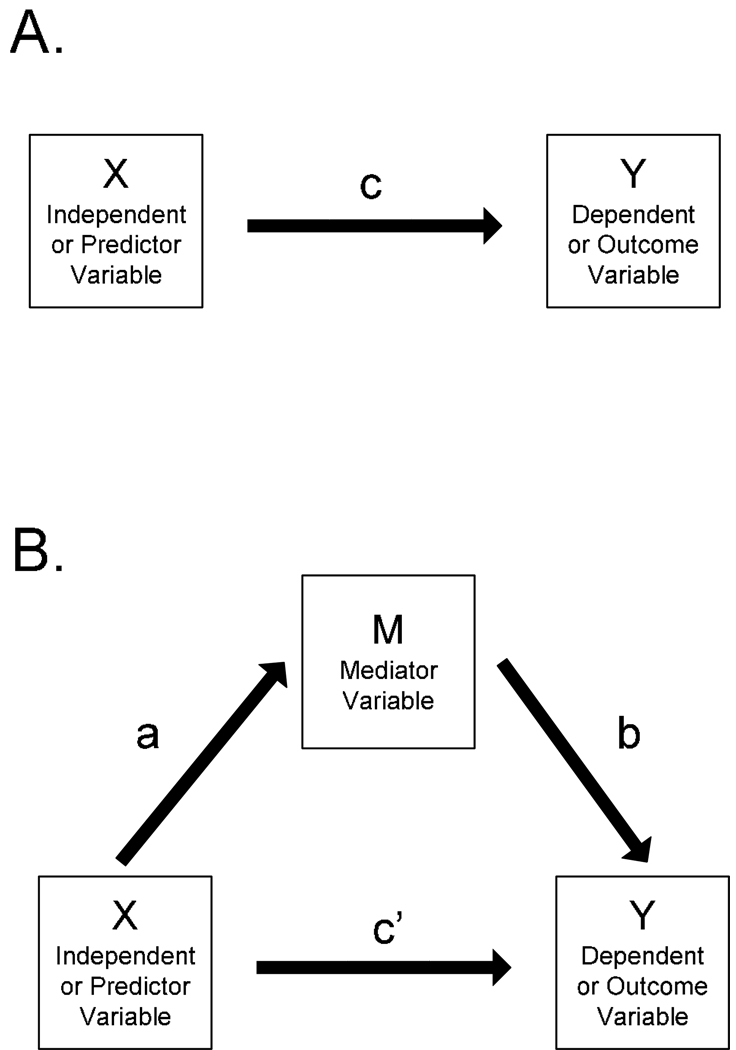

Regression analysis is a different approach to answer the same question. A predictor or independent variable (X) is defined, which would be drinking sweetened beverages, and it is related to the dependent variable (Y), number of cavities. This provides a regression coefficient, which is a measure of the relationship between beverage status and cavity number. This design is depicted in A of Figure 1, with the effect of X on Y labeled c. Each approach is equally valid, and the conclusions and p values from the two analyses would be the same (11).

Figure 1.

Regression analysis and a third mediating variable added to the model.

For certain questions, regression analysis has advantages over a t-test. With a t-test, a single variable must be used to split samples into groups, and in general, only one variable can be examined at a time. Regression analysis allows variables to be evaluated as continuous predictors (e.g., number of sweetened beverages consumed each day), and more than one predictor variable can be added into the analysis.

The use of regression analysis implies directionality, as X is defined as the predictor or independent variable and Y is the outcome or dependent variable. Although existing understanding and common sense might suggest that drinking sweetened beverages leads to more cavities rather than the reverse, one cannot determine causation when data are gathered from one time point. No statistical test proves causality. Cause and effect only can be established from a prospective randomized experiment, which assesses the population prior to and following an intervention. Regression analysis can be used where data are gathered over time, and depiction A of Figure 1 also could represent such a trial, where X represents a randomized intervention. Assuming the control and experimental condition were comparable at baseline, intervention status could be used to predict number of cavities following the intervention.

Mediation Adds Another Variable into the Regression Sequence

Regression analysis provides the ability to introduce other variables, including those that may have mediated the path between X and the outcome Y. Mediating variables also may be referred to as process variables, surrogate endpoints or proximal outcomes; each term relates to intervening parameters that come between the predictor variable (or initiation of an intervention) and the final outcome of interest (1–3, 12). A basic mediation model is shown in B of Figure 1. In this case, a second regression path is assessed that includes a potentially mediating variable, M. The independent predictor or intervention (X) is presumed to affect the mediator (M), and that path (a) is termed the action theory. In turn, M affects the outcome or dependent variable (Y), and the latter mediation path (b) is called the conceptual theory (17). Although second in the sequence, when designing an intervention, the conceptual theory is the initial step, as investigators decide what variables will relate to the outcomes of interest. Those become the purported mediating variables, and once identified, researchers decide on actions to affect those parameters.

Returning to the prospective tooth decay example, if the intervention was removing soda machines from schools, then the proposed mediator might be number of sodas consumed each day. A reduction in that mediating variable would be predicted to reduce tooth decay. The X → Y path is recalculated after statistically removing the component of that relationship accounted by the a and b paths, yielding c’. If that mediating variable completely accounts for the change in Y, then that c’ path goes to zero. In other words, if sodas consumed (X) explained all the variability in prevalence of tooth decay (Y), then c’ would go to zero. In most cases, however, a single mediator will not account for all of the effect, and the c’ direct effect still will be present

Other Variables: Confounders, Covariates and Moderators

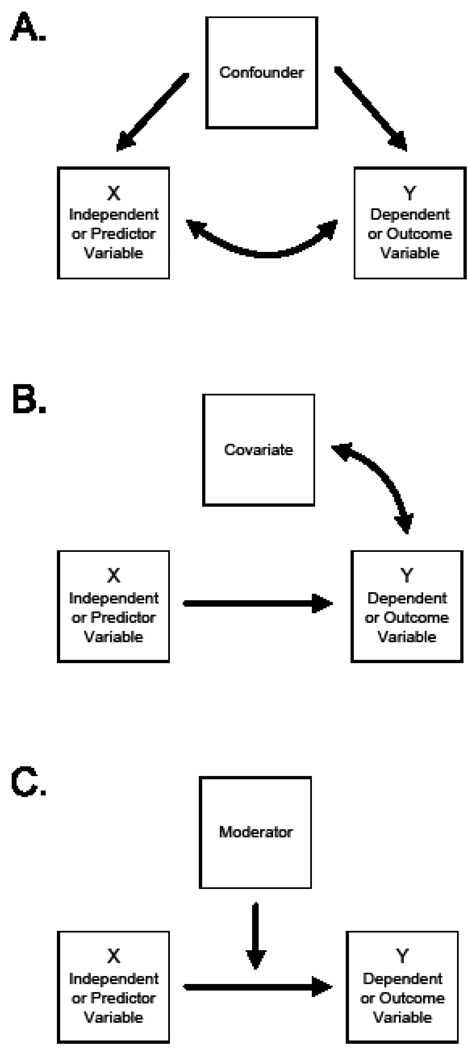

Mediation is only one of several relations that may be present when a third variable is included, and other types are confounders, covariates, and moderators (Figure 2). The distinction among these is in their relationship to other variables in the model. A variable that is a covariate in one study can be a moderator in another. Understanding these relationships is important when interpreting findings.

Figure 2.

Third variable models and relationships to independent and dependent variables: a confounder (panel A), a covariate (panel B), and a mediator (panel C).

A confounder is a variable that relates to both X and Y, but is not in the causal pathway (Figure 2.A.). Confounders are alternative explanations for the observed relationship of X → Y (11, 13, 14). An example might be represented by the epidemiologic observation that frequent urination was related to losing weight, and a regression analysis might indicate urination frequency predicted weight loss. It might be tempting to interpret this as a cause and effect connection. Instead, the apparent relationship between X and Y is due to a confounding variable, hyperglycemia, which accounted for both observations. Confounding variables are particularly important to consider when interpreting observational studies, because methods to control for confounders in prospective randomized trials, such as enrollment restrictions, randomization and matching, are not always present in observational studies (13).

A covariate is a variable that was not changed by the intervention, does not alter the X → Y relationship and improves prediction of the outcome (Figure 2.B.). Covariates often are a parameter measured in the population being studied, such as age, sex or socioeconomic status; including covariates in the analysis will explain additional variability in the dependent outcome variable. For example, investigators conducting a study of food diaries as a means to increase fruit and vegetable consumption find that those who kept food diaries ate more fruits and vegetables. When the influence of gender was assessed, women were found to eat more fruits and vegetables in both the intervention and control groups. Adjusting for that covariate will reduce the variability in fruit and vegetable consumption, allowing for more precise estimation of the effect of food diaries on changing fruit and vegetable consumption.

Moderators are a third type of variable that also must be factored into conclusions. Unlike covariates, moderators, also called interaction effects, change the relationship of X → Y (15, 16) (Figure 2. C.). For continuous moderators, the relationship varies across the range of that variable. As with covariates, moderators frequently are features of the study group and not affected by the intervention. In a study examining the relationship between calcium intake and bone density among premenopausal women, estrogen status might be a moderator. Calcium intake’s effect on bone density would be different for women experiencing hypoestrogenic amenorrhea than for women with normal estrogen levels. Moderators explain differential effects and specify for whom and when a treatment will be effective. Once identified, they become important variables to consider when enrolling subjects and randomizing them to study conditions.

MEDIATION IN STUDY DESIGN & INTERPRETATION

Mediation analysis can be critical when interpreting study findings. As a simplified example of its utility, suppose researchers were designing a weight loss study. They observed that obese individuals eat larger portion sizes (30) and also are less physically active (31). Those variables and relationships form the conceptual theory (M → Y). Then, investigators must decide how to implement an intervention to affect those mediators, which will define the action theory (X → M). Accordingly, they may design a program that teaches appropriate portion size and provides an incentive plan for increased physical activity. In their methods, investigators must use means to sequentially measure participants’ portion size and physical activity level, along with body weight. In addition, potential confounders, covariates and moderator variables need to be considered as the subject group is recruited, enrolled and randomized to study conditions.

Table 1 presents a matrix of potential study findings. For each row, the intervention group lost more weight than the control condition. However, the mediation outcomes and the result’s implications differ. Concluding that the intervention achieved its objectives and is ready for replication and wider dissemination would hold only for Study 1. It represents the ideal situation, with the intervention successfully impacting both targeted mediators, each of which are related to the outcome. In this example, both the conceptual and action theory were supported, and portion size and physical activity mediate the intervention effect.

Table 1.

Exploration of Program Effects Through Mediation Analysis

| Study | Action Theory: Intervention (X) → Mediator (M) (Is intervention related to mediator?) |

Conceptual Theory: Mediator (M) → Outcome (Y) (Is mediator related to outcome?) |

Interpretation and Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Intervention changed portion size: yes | Portion size related to body weight: yes | Conceptual and action theory supported for both mediators. Disseminate effective intervention. |

| Intervention changed physical activity: yes | Physical activity related to weight: yes | ||

| 2 | Intervention changed portion size: yes | Portion size related to body weight: yes | Portion size is a mediator. Conceptual theory supported for physical activity but exercise intervention not effective. Redesign or omit physical activity intervention component. |

| Intervention changed physical activity: no | Physical activity related to weight: yes | ||

| 3 | Intervention changed portion size: yes | Portion size related to body weight: no | Physical activity is mediator. Intervention changed portion size but because conceptual theory not supported, it was not a mediator. Assess theory and measurements and consider omitting that component. |

| Intervention changed physical activity: yes | Physical activity related to weight: yes | ||

| 4 | Intervention changed portion size: yes | Portion size related to body weight: no | Intervention changed targeted variables, but those changes were not related to the outcome. Program effects occurred through other mechanisms. |

In the second situation, the intervention successfully reduced portion size, and portion size was related to body weight. Although physical activity was related to body weight, the intervention failed to impact that variable, and only the conceptual theory was supported. With those findings, researchers must critically examine their physical activity intervention and decide whether to strengthen or discontinue that component to focus resources on the successful portion size aspect.

Study 3 findings indicate that the intervention changed both targeted mediators, but only physical activity was related to body weight. Thus, the conceptual theory relating portion size to body weight was not supported. This could mean that the conceptual theory is faulty. Perhaps it was based on cross-sectional observations, with both portion size and weight relating to some other confounding variable? With these study findings, investigators may wish to omit the intervention’s portion size component. Alternatively, if prior evidence for the portion size conceptual theory was robust, researchers may need to reassess their methodology for indexing that variable or incorporate another potential variable, such as time, into the analysis. Possibly a longer interval was required to establish the relationship between portion size and body weight? In either situation, the mediation analyses findings should lead to better understanding and inform subsequent study designs.

The final situation is where the intervention impacted both potential mediators, supporting the action theory, but neither was related to the outcome. Following the intervention, participants were eating smaller portions and more active, but those variables did not predict the change in weight. The implication is that other parameters altered by the intervention, such as provider contact or social support, also were changed, and those other parameters mediated the outcome. More likely than this extreme case would be that portion size and physical activity accounted for only a small amount of the mediating effect, leaving a large direct effect. Rather than incorrectly concluding that altering physical activity and portion size are ideal means to achieve weight loss, the investigators have the opportunity to identify other variables not included in the original mediation model that may have been affected to account for the positive intervention effects.

Despite the differences in mediation analyses outcomes, the examples in Table 1 all share a significant intervention effect. Although early guidelines for mediation analyses required an overall program effect (19), more recent research has shown that is not necessary (3, 32), and mediation analysis can be performed even when an intervention does not achieve significant changes in the study outcome. The examples in Table 1 also involve an intervention with only two manipulations, and most programs involve multiple components. When several mediators are present, they can be examined separately or simultaneously. For this example, in addition to physical activity and portion size, a weight loss study might attempt to reduce television viewing (31) and food energy density (34). Imagine Table 1 expanded to include additional intervention components, where the combination of potential mediating outcomes increases geometrically. Interpreting study findings and knowing which parts of the intervention to drop, alter and enhance become impossible without analyzing the mediation of each of its components.

Similarly, these examples have a limited number of time points, and longitudinal data with repeated measures of variables provide additional rich information for the investigation of mediation. More advanced techniques, such as structural equation and latent growth curve modeling, allow examination of mediation chains across multiple waves of data. However, those more complicated models are extensions of the basic mediation analysis (3).

In summary, mediation analysis generates evidence for how a program achieved its effects and provides a check on whether the program produced a change in variables that it was designed to change. Second, its results may suggest that certain program components need to be strengthened. Third, program effects on mediating variables in the absence of effects on outcome measures suggest that the targeted constructs were not critical in changing outcomes or that measurement of those parameters was faulty. Thus, identification of mediating variables provides information on the change process and allows streamlining programs by focusing on their effective components.

APPLYING MEDIATION CONCEPTS WHEN READING THE LITERATURE

Proponents of critical literature review have suggested steps that allow appropriate interpretation of research publications involving prognosis, diagnostic tests, therapy and economic analyses (35). A four-step structure can be applied to assess articles using mediation, explained in greater detail below:

Is mediation properly assessed?

Are theoretical underpinnings clearly stated and supported by prior research?

Is it a single time point observation? If more than one, are variables measured in the correct temporal sequence?

Is it a prospective randomized controlled intervention study?

At a minimum, a study purporting to show mediation (or lack of mediation) needs to conduct a statistical test of mediation (Step #1 - Is mediation properly assessed?). Although this may seem obvious, the term mediation often is used when no statistical mediation was performed (18).

There are three major approaches to statistical mediation analysis: 1) causal steps, 2) difference in coefficients, and 3) product of coefficients (18). The most widely used technique is the causal steps approach outlined in the classic work of Baron and Kenny (19) and Judd and Kenny (20, 21). Four steps are involved: 1) establish an overall effect between X and Y (the c path); 2) establish an affect of X on M (the a path); 3) establish an effect of M on Y after controlling for X (the b path); and 4) establish a reduction from the total effect (c) to the direct effect (c’), after controlling for M. A simpler, but equally valid, causal steps test is to require that both paths a and b be significant (18). A modified version of the Baron and Kenny approach that applies specifically to randomized trials is called the MacArthur model (12, 24). Keywords to look for in identifying a study that uses this method are “causal steps” or citations by “Baron and Kenny” (21), “Judd and Kenny” (22, 23), or “MacKinnon” (25).

The second and least used mediation method involves calculating the primary difference in the total effect and direct effect (c-c’). That value can then be divided by a standard error and tested for significance. Keywords for this statistical technique would include references to “Freedman & Schatzkin” (26) or “Clogg” (27). The third approach is the primary product of coefficients method, which calculates the mediated effect as a*b. This method is commonly used by statistical software packages, and the methods or results description frequently will include a reference to “Sobel” (26, 27). Although these different tests for mediation vary in their type I error rates and statistical power, identifying that investigators used any one of the three methods will establish that statistical mediation was assessed.

Steps #2 through #4 strengthen the conclusion that mediation occurred. A strong foundation in theory and prior research strengthens mediation claims (#2 – Are theoretical underpinnings clearly stated and supported by prior research?). This means that the authors describe both the conceptual theory for the purported mediators and the action theory for their intervention’s ability to affect the mediating variables by citing prior research that supports those relationships.

Although mediation analysis can be conducted on cross-sectional observations, a stronger case is made with longitudinal data, when variables that come earlier in the causal model are measured before those that come later (#3 – Is it a single observation and if more than one observation, are variables measured in the correct temporal sequence?). Adding a randomized design to longitudinal data collection makes causal mediation claims stronger by eliminating many possible confounders (#4 – Is it a prospective randomized controlled intervention study?) (36).

Using the Framework: An Example

The four-step analytic framework can be applied to an early work utilizing mediation published in the Journal of the American Dietetic Association by Fisher and colleagues (37). The investigators assessed a cohort of mothers and their infants. The variables of interest were duration of breast-feeding (X), maternal control of feeding (M), and caloric intake of the toddlers (Y). Maternal control of feeding was a self-report measure of child-feeding beliefs and behaviors.

Is mediation properly assessed?

Fisher et al. displayed the results of their regression analyses using the causal steps method. They determined an overall effect (the c path) of breast-feeding history on toddler energy intake. They also established the a path (breast-feeding history affects maternal control of feeding) and the b path (maternal control affects toddler energy intake). They defined the c’ path by statistically removing the paths through the mediating variable. They cited Baron and Kenny (19) as further evidence of their use of the causal steps method.

Are theoretical underpinnings clearly stated and supported by prior research?

The authors reported previous research relating child-feeding strategies to food intake (conceptual theory). Although they do not present prior evidence of a link between breast-feeding and maternal control of feeding, they establish a clear basis for the hypothesis based on prior research. Are variables measured in the correct temporal sequence? – The study was observational and longitudinal. It began after the child’s first year, when participants were grouped into those who had breast-fed for 12 months and those who did not. Six months later the outcome measure was assessed. Thus, the independent variable preceded measurement of the outcome, but the description of methods is less clear as to whether maternal control of feeding was measured prior to or concurrent with the dietary records used to calculate energy intake.

Is it a randomized intervention study?

The study was a longitudinal observational study and did not have randomization or an intervention. Therefore, one must be concerned about confounders and recognize that making firm conclusions about causal direction is problematic. Women’s existing attitudes about child-feeding may have influenced both their decision to breast-feed and their child’s later caloric intake. Applying the proposed mediation framework allows readers to interpret the mediation jargon and thoughtfully consider the authors’ conclusions.

Mediation in Recent Nutrition Literature

We identified 157 articles using the search terms mediation crossed with keywords nutrition, diet, food and obesity in the title, abstract or text for the 29 months beginning in January 2006. Following the exclusion of reviews and works that involved non-humans or exclusively biochemical measures, 72 manuscripts were reviewed. Thirty-two of the 72 did not use statistical mediation and failed Step #1, including nine with mediation in the articles’ title.

The 40 articles presented in Tables 2 and 3 used a statistical test of mediation. Each also included a discussion of the theoretical underpinnings for their purported mediators’ effects (Step #2). The manuscripts are grouped according to the third and forth framework components. The majority (Table 2) were observational studies with data collected at a single or more than one time point. Table 3 presents the 11 articles that reported mediation findings for controlled intervention trials.

Table 2.

Mediation in the Nutritional Literature

| Observational Studies with Data Gathered at a Single Time Point | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Author (Reference No.) |

Subjects | Predictor/Independent Variable |

Dependent/Outcome Variable |

Purported Mediator(s) |

| Annus (38) | US collegiate women |

Family experiences (teasing, modeling) |

Disordered eating | Expectancies for life improvement from thinness |

| Bere (39) | Norwegian adolescents |

Gender | Fruit & vegetable intake | Accessibility, preferences & self- efficacy |

| Beydoun (40) | Cross-section US adults |

Nutrition knowledge & beliefs |

Diet quality | Away from home food experiences |

| Beydoun (41) | Cross-section US adults |

Income & education | Diet quality | Perceived barriers food prices & benefits of quality diet |

| Beydoun (42) | NHANES data | Ethnicity/race | Obesity & index metabolic syndrome |

Dairy food group intake |

| Brown (43) | Adults with mental illness |

Mental performance composite score |

Grocery shopping skills | Grocery shopping knowledge |

| Brug (44) | European school children |

Gender | Fruit & vegetable intake | Accessibility, modeling & preferences |

| Caperchione (45) | Australian adults | BMI | Intentions for physical activity |

Attitudes, behavior control & subjective norms |

| Cerin (46) | Australian adults | Education, income, household size |

Physical activity | Individual & environmental variables |

| Decaluwé (47) | Flemish obese adolescents |

Parent characteristics & behaviors |

Psychological problems | Parenting style (inconsistent discipline) |

| Hanson (48) | US high school students |

Income, parent education & occupation |

BMI | Sedentary behaviors |

| Hesketh(49) | Australian families |

Maternal education | Children’s TV viewing | 21 aspects family TV environment |

| Jago (50) | Houston boy scouts |

Distance to food stores & restaurants |

Fruit & vegetable intake | Food preferences & availability in home |

| Janicke (51) | US overweight adolescents |

Peer victimization | Quality of life | Depressive symptoms |

| Klepp (52) | 11 year olds from 9 European countries |

Exposure food commercials on TV |

Fruit & vegetable intake | Attitudes & preferences about fruits & vegetables |

| Luyckx (53) | Dutch adults with type 1 diabetes |

Identification diabetes related problems |

Depression | Adaptive & maladaptive coping |

| Proper (54) | Working Australian adults |

Education & income | BMI | Sitting on weekdays, weekends & in leisure time |

| Mai (55) | 8 to 10 year old Canadian youth |

Milk consumption | Asthma | Being overweight |

| Mond (56) | Australian women |

Psychological functioning & quality of life |

Obesity | Weight/shape concerns & binge-eating |

| Sacco (57) | US adults with type 2 diabetes |

Behavioral adherence, self-care, BMI |

Depressions | Symptoms diabetes & self-efficacy |

| Sawatzky (58) | Elderly Canadians |

Chronic medical conditions |

Quality of life & functional abilities |

Leisure time activities |

| Shin (59) | Korean children grades 5 & 6 |

Obesity | Self-esteem | Body dissatisfaction |

| Wansink (60) | French and US college students |

Country of origin | BMI | Internal & external cues of meal cessation |

| Woo (61) | US adolescents | Race & parental education | Obesity | Breast feeding history |

| Zeller (62) | Obese US adolescents |

Child obesity status | Family dynamics & functioning | Maternal distress |

| Observational Studies with Data Gathered at More than One Time Point | ||||

| Franko (63) | US adolescents | Family meals | Adolescent health (smoking, stress & disordered eating) | Family cohesion & coping skills |

| Ornelas (64) | US adolescents | Perceived parental influences |

Vigorous physical activity 6 years later |

Self esteem & depression at baseline |

| Walker (65) | Jamaican children |

Early childhood stunting | Psychological functioning | Cognitive ability |

| Wansink (66) | US secretaries | Proximity & covering candy dish |

Candy intake | Self perceived intake candy |

Table 3.

Mediation in the Nutritional Literature

| Randomized Intervention Trials | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Author (Reference No.) |

Subjects | Intervention | Dependent/Outcome Variable |

Purported Mediator(s) |

| Barerra (65) | Post-menopausal US women with type 2 diabetes |

Mediterranean Lifestyle Program |

Fat consumption, physical activity & glycemic control |

Social support variables |

| Barerra (66) | Post-menopausal US women with type 2 diabetes |

Mediterranean Lifestyle Program |

Fat consumption, physical activity & glycemic control |

Social support variables |

| Burke (67) | Overweight hypertensive Australian adults |

Weight loss dietary intervention |

Saturated fat intake & physical activity |

Self-efficacy, barriers, beliefs & social support |

| Campbell (68) | Pooled data 5 US community interventions |

Population-based strategies to increase fruit & vegetable consumption |

Fruit & vegetable intake | Knowledge & self-efficacy |

| Doerksen (69) | Participants in exercise intervention |

Messaging newsletter about fruit & vegetable intake |

Fruit & vegetable intake | Social cognitive messages newsletter |

| Elliot (70) | Career US fire fighters |

Team-based & motivational interviewing |

Fruit & vegetable intake & quality of life |

Knowledge, beliefs & social support |

| Epstein (71) | Overweight US children |

Increasing fruit, vegetable and low fat dairy consumption vs. Reducing high energy-dense foods |

BMI change | Parent concern for child weight |

| Fuemmeler (72) | African-American US church goers |

Body & Soul intervention | Fruit & vegetable intake | Social support, self-efficacy & autonomous motivation |

| Haerens (73) | Flemish adolescent girls |

School-based & parent intervention |

Fat intake | Psychosocial determinants |

| Scholz (74) | German adults in cardiac rehab |

Self-management instructions |

Depression | Perceived achievement goals & level physical activity |

| Stice (75) | US adolescent girls | Dissonance or healthy weight intervention |

Body dissatisfaction, affect & eating behaviors |

Thin internal ideal, healthy eating & physical activity |

The works listed demonstrate that mediation analysis has been used with many types of nutritional studies and is increasing in frequency (6 publications in 2006, 17 in 2007 and 17 in January through May of 2008). However, critical reading is required, as almost half of the 72 articles in this inclusive review discussed mediation without performing tests to establish its presence.

The growing appreciation of mediation’s utility also is suggested by recent topic reviews. Ventura and Birch (78) reviewed 67 articles assessing the association among parenting characteristics, child eating habits and child weight. They found that no study met the criteria needed to test a full mediation model, and that despite increased publications on these topics, the “evidence for the influence of parenting and feeding practices on children’s eating and weight status is limited.” The authors noted the importance of including mediation analysis in subsequent studies. Authors of a recent review of studies examining the psychosocial predictors of fruit and vegetable intake (79) reached similar conclusions about the importance of stronger experimental designs and including mediation analysis in the assessment. Thus, the field appears poised for expanded work using these statistical techniques, and readers can anticipate more publications with mediation methodology.

CONCLUSIONS

Mediation analysis is a newer statistical tool that can establish the existence of causal relationships among variables. It allows researchers to move beyond simply establishing an intervention’s efficacy to determining which aspects of an intervention are contributing to change. By establishing the temporal sequence among variables, mediation analysis helps describe behaviors, and for interventions impacting those behaviors, it defines means for their modification and improvement. The appearance of nutrition articles using these methods is increasing. However, as with most methodologies, it has its own terminology, advantages and limitations. Familiarity with the classes of mediation tests and a few key parameters will allow readers to make informed evaluations of articles using these methods.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health R01CA105835, R01CA105774, RO1 HL0771020 and in part by PHS M01 RR00334.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM. Advances in statistical methods for substance abuse prevention research. Prevention Sci. 2003;4(3):155–171. doi: 10.1023/a:1024649822872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS. Mediation analysis. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58:593–614. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shadish WR. Meta-analysis and the exploration of causal mediating processes: a primer of examples, methods, and issues. Psychol Methods. 1996;1:47–65. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baranowski T, Anderson C, Carmack C. Mediating variable framework in physical activity interventions: How are we doing? How might we do better? Am J Prev Med. 1998;15(4):266–297. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00080-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kraemer HC, Wilson T, Fairburn CG, Agras WS. Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:877–883. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baranowski T. Advances in basic behavioral research will make the most important contributions to effective dietary change programs in time. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106(6):808–811. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kristal AR, Glanz K, Tilley BC, Li S. Mediating factors in dietary change: Understanding the impact of a worksite nutrition intervention. Health Educ Behav. 2000;27(1):112–125. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boushey C, Harris J, Bruemmer B, Archer SL, Van Horn L. Publishing nutrition research: A review of study design, statistical analyses, and other key elements of manuscript preparation, Part 1. J Am Dietetic Assoc. 2006;106:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gray GE, Gray LK. Evidence-based medicine: Applications in dietetic practice. J Am Dietetic Assoc. 2006;102:1263–1272. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90279-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keppel G, Wilkens TD. Design and analysis: A researcher’s handbook. fourth edition. Englewood Cliff, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kraemer HC, Stice E, Kazdin A, Kupfer D. How do risk factors work together to produce and outcome? Mediators, moderators, independent, overlapping and proxy risk factors. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:848–856. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.6.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grimes DA, Schultz KF. Bias and causal associations in observational research. Lancet. 2002;359:248–252. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07451-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jager KJ, Zoccali C, MacLeod A, Dekker FW. Counfounding: what it is and how to deal with it. Kidney Int. 2008;73:256–260. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kraemer HC, Frank E, Kupfer DJ. Moderators of treatment outcomes: clinical, research, and policy importance. JAMA. 2006;296(10):1286–1289. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.10.1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen HT. Theory-driven evaluations. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Personality Social Psychol. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Judd CM, Kenny DA. Estimating the effects of social interventions. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Judd CM, Kenny DA. Process analysis: estimating mediation in treatment evaluations. Eval Rev. 1981;5:602–619. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kraemer HC, Kiernan M, Essex M, Kupfer DJ. How, and why criteria defining moderators and mediators differ between the Baron & Kenny and MacArthur approaches. Health Psychol. 2008;27(2 Suppl):S101–S108. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2(Suppl.).S101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacKinnon DP, Krull JL, Lockwood CM. Equivalence of the mediation, confounding, and suppression effect. Prev Sci. 2000;1:173–181. doi: 10.1023/a:1026595011371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freedman LS, Schatzkin A. Sample size for studying intermediate endpoints within intervention trials or observational studies. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;136:1148–1159. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clogg CC, Petkova E, Shihadeh ES. Statistical methods for analyzing collapsibility in regression models. J Ed Stat. 1992;17:51–74. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociol Methodol. 1982;13:290–312. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sobel ME. Some new results on indirect effects and their standard errors in covariance structure models. Sociol Methodol. 1986;16:159–186. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rolls BJ, Morris EL, Roe LS. Portion size of food affects energy intake in normal-weight and overweight men and women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002 Dec;76(6):1207–1213. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.6.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rippe JM, Hess S. The role of physical activity in the prevention and management of obesity. J Am Dietetic Assoc. 1998;98(10) Supplement:S31–S38. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(98)00708-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fritz MS, MacKinnon DP. Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychol Sci. 2007;18(3):233–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gable S, Chang Y, Krull JL. Television watching and frequency of family meals are predictive of overweight onset and persistence in a national sample of school-aged children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107(1):53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rolls BJ, Drewnowski A, Ledikwe JH. Changing the energy density of the diet as a strategy for weight management. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105(5 Supplement 1):S98–S103. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sackett DL, Haynes RB, Guyatt GH, Tugwell P. Clinical epidemiology: A basic science for clinical medicine. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holland PW. Causal inference, path analysis and recursive structural equation models. Sociol Methodol. 1988;18:449–484. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fisher JO, Birch LL, Smiciklas-Wright H, Picciano MF. Breast-feeding through the first year predicts maternal control in feeding and subsequent toddler energy intakes. J Am Diet Assoc. 2000;100(6):641–646. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(00)00190-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Annus AM, Smith GT, Fischer S, Hendricks M, Williams SF. Associations among family-of-origin food-related experiences, expectancies, and disordered eating. Int J Eat Disord. 2006;40(2):179–186. doi: 10.1002/eat.20346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bere E, Brug J, Klepp K-I. Why do boys eat less fruit and vegetables than girls? Public Health Nutr. 2007;11(3):321–325. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007000729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beydoun MA, Powell LM, Wang Y. Reduced away-from-home food expenditures and better nutrition knowledge and belief can improve quality of dietary intake among US adults. Public Health Nutr. 2008;22:1–13. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008002140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beydoun MA, Wang Y. How do socio-economic status, perceived economic barriers and nutritional benefits affect quality of dietary intake among US adults? Eur J Clin Nutr. 2008;62(3):303–313. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beydoun MA, Gary TL, Caballero BH, Lawrence RS, Cheskin LJ, Wang Y. Ethnic differences in dairy and related nutrient consumption among US adults and their association with obesity, central obesity, and the metabolic syndrome. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(6):1914–1925. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.6.1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown CE, Rempfer MV, Hamera E, Bothwell R. Knowledge of grocery shopping skills as a mediator of cognition and performance. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(4):573–575. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.4.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brug J, Tak NI, te Velde SJ, Bere E, de Bourdeaudhuij I. Taste preferences, liking and other factors related to fruit and vegetable intakes among schoolchildren: Results from observational studies. Br J Nutr. 2008;99 Supp 1:S7–S14. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508892458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caperchione CM, Duncn MJ, Mummery K, Steele R, Schofield G. Mediating relationship between body mass index and the direct measures of the Theory of Planned Behaviour on physical activity intention. Psych Health Med. 2008;12(2):168–179. doi: 10.1080/13548500701426737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cerin E, Leslie E. How socio-economic status contributes to participation in leisure-time physical activity. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:2596–2609. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Decaluwe V, Braet C, Moens E, Van Vlierberghe L. The association of parental characteristics and psychological problems in obese youngsters. Int J Obesity. 2006;30:1766–1774. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hanson MD, Chen E. Socioeconomic status, race, and body mass index: the mediating role of physical activity and sedentary behaviors during adolescence. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32(3):250–259. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsl024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hesketh K, Ball K, Crawford D, Campbell K, Salmon J. Mediators of the relationship between maternal education and children’s TV viewing. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(1):41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jago R, Baranowski T, Baranowski JC, Cullen KW, Thompson D. Distance to food stores & adolescent male fruit and vegetable consumption: mediation effects. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2007;4:35. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-4-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Janicke DM, Mariel KK, Ingerski LM, Novoa W, Lowery KW, Sallinen BJ, Silverstein JH. Impact of psychosocial factors on quality of life in overweight youth. Obesity. 2007;15(7):1799–1807. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Klepp K-I, Wind M, de Bourdeaudhuij I, Rodrigo CP, Due P, Bjelland M, Brug J. Television viewing and exposure to food-related commercials among European school children, associations with fruit and vegetable intake: a cross sectional study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2007;4:46. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-4-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Luyckx K, Seiffg-Krenke I, Schwartz SJ, Gossens L, Weets I, Hendrieckx C, Groven C. Identity development, coping, and adjustment in emerging adults with a chronic illness: the sample case of type 1 diabetes. J Adolesc Health. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.04.005. DOI: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Proper KI, Cerin E, Brown WJ, Owen N. Sitting time and socio-economic differences in overweight and obesity. Int J Obesity. 2007;31:169–176. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mai X-M, Becker AB, Sellers EAC, Liem JJ, Kozyrskyj AL. Infrequent milk consumption plus being overweight may have great risk for asthma in girls. Allergy. 2007;62(11):1295–1301. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mond JM, Rogers B, Hay PJ, Darby A, et al. Obesity and impairment in psychosocial functioning in women: The mediating role of eating disorder features. Obesity. 2007;15(11):2769–2779. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sacco WP, Wells KJ, Friedman A, Matthew R, Perez S, Vaughan CA. Adherence, body mass index, and depression in adults with type 2 diabetes: The mediational role of diabetes symptoms and self-efficacy. Health Psychol. 2007;2(6):693–700. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.6.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sawatzky R, Liu-Ambrose T, Miller WC, Marra CA. Physical activity as a mediator of the impact of chronic conditions on quality of life in older adults. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:68. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shin NY, Shin MS. Body dissatisfaction, self-esteem, and depression in obese Korean children. J Pediatr. 2008;152:502–506. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wansink B, Payne CR, Chandon P. Internal and external cues of meal cessation: The French paradox redux? Obesity. 2007;15:2920–2924. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Woo JG, Dolan LM, Morrow AL, Geraghty SR, Goodman E. Breastfeeding helps explain racial and socioeconomic status disparities in adolescent obesity. Pediatrics. 2008;121(3):e458–e465. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zeller MH, Reiter-Purtill J, Modi AC, et al. Controlled study of critical parent and family factors in the obesigenic environment. Obesity. 2007;15(1):126–136. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Franko DL, Thompson D, Affenito SG, Barton BA, Streigel-Moore RH. What mediates the relationship between family meals and adolescent health issues? Health Psychol. 2008;27 Supp 2:S109–S117. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2(Suppl.).S109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ornelas IJ, Perreira KM, Ayala GX. Parental influences on adolescent physical activity: A longitudinal study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2007;4:3. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-4-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Walker SP, Chang SM, Powell CA, Simonoff E, Grantham-McGregor SM. Early childhood stunting is associated with poor psychological functioning in late adolescence and effects are reduced by psychosocial stimulation. J Nutr. 2007;137:2464–2469. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.11.2464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wansink B, Painter JE, Lee Y-K. The office candy dish: proximity’s influence on estimated and actual consumption. Int J Obesity. 2006;30:871–875. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Barrera M, Jr, Toobert DJ, Angell KL, Glasgow RE, MacKinnon DP. Social support and social-ecological resources as mediators of lifestyle intervention effects for type 2 diabetes. J Health Psychol. 2006 May;11(3):483–495. doi: 10.1177/1359105306063321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Barrera M, Jr, Strycker LA, MacKinnon DP, Toobert DJ. Social-ecological resources as mediatiors of two-year diet and physical activity outcomes in type 2 diabetes patients. Health Psychol. 2008;27(2 Suppl):S118–S125. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2(Suppl.).S118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Burke V, Beilin LJ, Cutt HE, Mansour J, Mori TA. Moderators and mediators of behavior change in a lifestyle program for treated hypertensives: A randomized controlled trial (ADAPT) Health Educ Res. 2008;23(4):583–591. doi: 10.1093/her/cym047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Campbell MK, McLerran D, Turner-McGrievy G, et al. Mediation of adult fruit and vegetable consumption in the national 5 A Day for Better Health community studies. Ann Behav Med. 2008;35:49–60. doi: 10.1007/s12160-007-9002-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Doerksen SE, Estabrooks PA. Brief fruit and vegetable messages integrated within a community physical activity program successfully changed behavior. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2008;4:12. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-4-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Elliot DL, Goldberg L, Kuehl KS, Moe EL, Breger RK, Pickering MA. The PHLAME (Promoting Healthy Lifestyles: Alternative Models' Effects) Firefighter Study: Outcomes of Two Models of Behavior Change. J Occup Environ Med. 2007;49(2):204–213. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3180329a8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Epstein LH, Paluch RA, Beecher MD, Roemmich JN. Increasing healthy eating vs reducing high energy-dense foods to treat pediatric obesity. Obesity. 2008;16:318–326. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fuemmeler BF, Masse LC, Yaroch AL, Resnicow K, Campbell MK, Carr C, Wang T, Williams A. Psychosocial mediation of fruit and vegetable consumption in the body and soul effectiveness trial. Health Psychol. 2006;25(4):474–483. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.4.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Haerens L, Cerin E, Deforce B, Maes L, De Bourdeaudhuij I. Explaining the effects of a 1-year intervention promoting a low fat diet in adolescent girls: A mediation analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2008;4:12. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-4-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Scholz U, Knoll N, Sniehotta FF, Schwarzer R. Physical activity and depressive symptoms in cardiac rehabilitation: long-term effects of a self-management intervention. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:3109–3120. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Stice E, Presnell K, Gau J, Shaw H. Testing mediators of intervention effects in randomized controlled trials: an evaluation of two eating disorder prevention programs. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75(1):20–32. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ventura AK, Birch LL. Does parenting affect children’s eating and weight status? Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2008;5:15. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-5-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shaikh AR, Yaroch AL, Nebeling L, Yeh M-C, Resnicow K. Psychosocial predictors of fruit and vegetable consumption in adults: A review of the literature. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(6):535–543. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]