Abstract

How does culture shape the experience and expression of depression? Previously we observed that depression dampened negative emotional responses in European Americans, but increased negative emotional responses in Asian Americans (Chentsova-Dutton et al., 2007). We interpreted these findings as support for the cultural norm hypothesis, which predicts that depression reduces individuals’ abilities to react in culturally normative or ideal ways (i.e., disrupting European Americans’ abilities to express their emotions openly and Asian Americans’ abilities to moderate and control their emotions). In the present study, we examined the generalizability of the cultural norm hypothesis to positive emotion. We measured the emotional reactivity of 35 European Americans (17 depressed, 18 controls) and 31 Asian Americans (15 depressed, 16 controls) to an amusing film clip. Consistent with the cultural norm hypothesis, depressed European Americans showed dampened positive emotional reactivity (i.e., fewer enjoyment and non-enjoyment smiles, less intense reports of positive emotion, lower cardiac activation) compared to control European Americans, whereas depressed Asian Americans showed similar (i.e., smiles, reports of positive emotion), and even greater (i.e., higher cardiac activation) positive emotional reactivity compared to control Asian Americans. These findings suggest that the cultural norm hypothesis generalizes to the experience and expression of positive emotion.

Keywords: Depression, Culture, Asian Americans, Emotion, Facial Expression, Positive Emotions

Further Evidence for the Cultural Norm Hypothesis: Positive Emotion in Depressed and Control European Americans and Asian Americans Women

“...In working with... those from Asian background, a Euro-American therapist can feel not only uncertain but at sea. This is because there is a different normality/psychopathology continuum from the one we are used to, influenced by radically different cultural patterns than our own...” (Roland, 2005).

The above quotation illustrates the frustration often experienced by many Western clinicians when diagnosing and treating mental illness in individuals from East Asian cultural contexts. One prevailing theory is that cultural differences in norms regarding emotional expression present a significant threat to diagnostic validity and make it difficult to interpret expressions of mental illness (see Leong & Lau, 2001). For example, clinicians and researchers have long speculated that because of East Asian norms to moderate and control one's emotions, depressed individuals in East Asian cultures tend to moderate their emotions in favor of physical complaints (Kleinman, 1982; Parker, Cheah, & Roy, 2001; Ryder et al., 2008; Simon et al., 1999; Waza et al., 1999), making their reports and displays of emotion unreliable indicators of their mental health status. Rather than rendering reports and displays of emotion unreliable; however, East Asian norms of emotional expression may produce different emotional responses in depressed individuals than do American norms of emotional expression. Surprisingly few studies have compared the emotional reactivity (i.e., moment-to-moment loosely coordinated changes in several systems including perception, feelings, behavior, and peripheral and central physiology that occur in response to identifying personally relevant events, reacting to them, and categorizing reaction to them as instances of emotional concepts) associated with depression in American and East Asian cultures. In a previous study (Chentsova-Dutton et al., 2007), we demonstrated that the effects of depression on reactivity to negative emotional stimuli varied for European American and Asian American individuals. The present study examines whether these differences generalize to responses to positive emotional stimuli. Prior to describing the study, we outline the theory motivating this research in greater detail.

Cultural Norm Hypothesis

The “cultural norm hypothesis” predicts that depressed individuals display patterns of positive and negative emotional reactivity that differ from their culturally ideal ways of experiencing and expressing emotions (Chentsova-Dutton e al., 2007). More specifically, we hypothesize that the symptoms of depression (i.e., impaired concentration, low energy, and inability to receive pleasure from social reinforcements) impair individuals’ abilities to attend to and enact cultural norms and ideals regarding emotion. In addition, reduced ability to enact culturally normative emotions may result in additional stress and isolation, further exacerbating depressive symptoms. Therefore, in cultures that emphasize the open expression of emotion, depression should be associated with a failure to upregulate experience and expression of emotions, dampening positive and negative emotional reactivity as a result. By contrast, in cultures that emphasize moderation and control of emotion, depression should be associated with a failure to moderate experience and expression of emotions. In this case, we would not expect to see dampening of positive and negative emotional reactivity. Because impaired concentration and low energy may affect individuals’ abilities to engage with elicitors of emotions as well as their abilities to attend to and enact cultural norms regarding emotion, we may observe that depression does not significantly alter emotional reactivity in these cultures. Alternatively, impaired concentration and low energy may impair individuals’ abilities to engage with elicitors of emotions less that their abilities to attend to and enact norms about emotions because the former task may be less cognitively and motivationally complex than the latter. If so, we may observe enhanced positive and negative reactivity in these cultures.

For instance, mainstream European American culture emphasizes the open expression of one's emotions as a way of asserting one's individuality (Bellah, Madsen, Sullivan, Swindler, & Tipton, 1985; Wierzbicka, 1992; 1999). Although these norms apply to both positive and negative emotions, the experience and expression of high arousal positive emotions such as happiness, excitement and cheerfulness are particularly valued (Bellah et al., 1985; Kotchemidova, 2005; Tsai, Knutson, & Fung, 2006). In this cultural context, anhedonia (i.e., loss or interest in pleasure)---one of the core features of depression---represents a failure to enact cultural norms of maintaining a cheerful emotional state and pursuing and enjoying pleasurable experiences (Lutz, 1985; Mesquita & Walker, 2003). Thus, depressed European American individuals should show dampened emotional responses, particularly positive emotional responses.

A number of studies have examined whether the dysphoria, loss of interest and pleasure described by depressed individuals from European American or Western European cultural backgrounds are reflected in online reactivity to specific elicitors of negative and positive emotions in laboratory settings (e.g., emotional films, images) (Bylsma, Morris, & Rottenberg, 2008). These studies demonstrate that, in comparison to healthy controls, European American depressed individuals react less intensely to negative and positive stimuli, such as imagery (Gehricke & Fridlund, 2002; Sloan, Strauss, Quirk & Sajatovic, 1997), pictures (Allen et al., 1999), and emotional films (Rottenberg, Kasch, Gross, & Gotlib, 2002; Renneberg, Heyn, Gebhard, & Bachmann, 2005). Therefore, depression among European Americans is associated with diminished negative and positive emotional reactivity to emotional stimuli.

Compared to American contexts, East Asian cultures promote the moderation of emotion---including high arousal positive emotions such as excitement---as way of avoiding interpersonal tension (Bond, 1991; Heine, Lehman, Markus, & Kitayama, 1999; Iwata, Roberts, & Kawakami, 1995; Markus & Kitayama, 1991; Russell & Yik, 1996). For example, Japanese are more likely than European Americans to recognize that open expression of happiness may endanger interpersonal harmony (Uchida, Norasakkunkit & Kitayama, 2004). As a result, individuals from East Asian cultures are more likely than European Americans to report making an effort to mask or suppress their expressions of high arousal positive emotions (Gross & John, 1998; Gross, Richards, & John, 2006; Matsumoto et al., 2008), or express them indirectly (Hsu et al., 1985). Not surprisingly, different individuals within European American and East Asian cultural settings respond differently to these norms; however, despite significant within-culture and across-situation variability (Matsumoto, 1990; Matsumoto et al., 2008), studies show that college students and adults from East Asian cultural contexts experience and express lower levels of high arousal positive emotions (Eid & Diener, 2001; Mesquita & Karasawa, 2002; Scherer, Matsumoto, Wallbott, & Kudoh, 1988; Tsai, Chentsova-Dutton, Freire-Bebeau, & Przymus, 2002). This pattern of reactivity is consistent with East Asian cultural norms. Similarly, Asian samples and Asian Americans report lower levels of pleasure and interest than do European Americans on measures of depression administered to college student and adult samples not selected for their clinical status (Iwata et al, 1995; Iwata & Buka, 2002; Kanazawa, White, & Hampson, 2007; Yen et al., 2000).

Thus, the cultural norm hypothesis predicts that due to the symptoms associated with depression, depressed East Asians should show similar or increased levels of positive emotional reactivity compared to control East Asians. The findings from the few studies that have examined emotional functioning among depressed individuals from East Asian cultural settings are consistent with the cultural norm hypothesis. For example, two studies showed no differences in retrospective reports of positive affect for depressed and non-depressed individuals from East Asian cultures (Iwata et al., 1998; Yen et al., 2000), and a third study found that the more depressed Asian American college students were, the more they endorsed the open expression of positive and negative emotion (Aldwin & Greenberger, 1987). These studies, however, did not examine on-line positive emotional reactivity.

Therefore, in a previous study, we compared the emotional reactivity of depressed and control European Americans and Asian Americans to sad and amusing film clips (Chentsova-Dutton et al., 2007). Consistent with the cultural norm hypothesis, depressed European Americans showed dampened negative emotional reactivity to the sad film compared to control European Americans, whereas depressed Asian Americans showed heightened negative emotional reactivity to the sad film compared to control Asian Americans. That is, depressed participants from both cultural groups demonstrated emotional responses that were inconsistent with their culture's ideal way of experiencing and expressing negative emotion.

Participants’ emotional responses to the amusing film clip, however, were inconsistent with the cultural norm hypothesis. On the one hand, these findings suggest that the cultural norm hypothesis may not apply to positive emotions. On the other hand, because the amusing film clip was always presented after the sad film clip, it is possible that participants’ emotional responses to the sad film clip influenced their responses to the amusing film clip, or that their pattern of responses was due to fatigue. Consequently, it remains unclear whether the cultural norm hypothesis applies to positive emotional reactivity. Therefore, in the present study, we presented an amusing film clip to depressed and control European Americans and Asian Americans. We predicted that depressed European Americans would show lesser positive emotional reactivity than would control European Americans, whereas depressed Asian Americans would show similar or even greater positive emotional reactivity than would control Asian Americans.

Method

Participants

Thirty-five European American (17 depressed, 18 controls) and 31 Asian American (15 depressed, 16 controls) English-speaking adult women participated in the study. This sample size was expected to offer moderate statistical power in detection of the expected effects. The sample size is consistent with those reported in the literature on the effects of depression on emotional reactivity of European Americans (see Bylsma et al., 2008), and members of ethnic minorities (Tsai, Pole, Levenson, Munoz, 2003). The sample was limited to women in order to reduce within-sample variability in positive emotional reactivity (see Chentsova-Dutton & Tsai, 2007). Participants were recruited through advertisements and clinical referrals.

The sample's demographics are presented in Table 1. Asian Americans represented several East Asian cultures (Chinese, 64.5%; Korean, 16.1%; Southeast Asian, 12.9%; and Japanese, 6.5%). Nearly half of the Asian Americans (n = 13, 41.8%) were born overseas, and spent an average of 14.35 years (SD = 10.68) in the U.S. The remaining Asian Americans were second (n = 15, 48.3%), and third (n = 3, 9.7%) generation immigrants1. Depressed and control Asian Americans did not differ in their generational status (χ2 (3, N = 31) = .31, ns). European Americans were born and raised in the U.S., had U.S.-born parents, and identified themselves as White/Caucasian. About a third of the group had at least one foreign-born grandparent (n = 12, 34.3%).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| Means (SD) and percentages |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depressed | Control | |||

| EA | AA | EA | AA | |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age | 37.88 (12.48)b | 32.03 (9.58)b | 32.05 (10.30)b | 28.44 (8.43)b |

| Household incomea | 3.00 (1.12)b | 2.74 (0.96)b | 2.94 (0.94)b | 2.75 (0.86)b |

| Cultural orientation | ||||

| GEQ - American | 3.85 (0.37)b | 3.62 (0.59)b | 3.98 (0.39)b | 3.64 (0.65)b |

| GEQ – East Asian | -- | 3.09 (0.68)b | -- | 3.13 (0.75)b |

| Years spent in the US (n = 14) | -- | 14.86 (7.69)b | -- | 13.83 (13.69)b |

| Depression severity | ||||

| BDI** | 28.24 (13.52)b | 25.67 (8.66)b | 1.85 (2.70)c | 3.29 (4.91)c |

| HDRS** | 13.53 (5.62)b | 15.00 (4.57)b | 1.76 (1.79)c | 1.80 (2.54)c |

| Treatment status | ||||

| Psychotropic medication (%) | 29.40b | 20.00b | -- | -- |

Note.

Measured on a 1-5 scale, with higher scores indicating higher levels of household income (a score of 3 is equivalent to middle class income). EA = European Americans; AA = Asian Americans. GEQ = The Generalized Ethnicity Questionnaire, American and East Asian versions, BDI = Beck Depression Inventory score; HDRS = Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Means and proportions having the same subscript within rows are not significantly different at p < .05.

p < .01.

Clinical Assessment

Participants were interviewed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID; First, Gibbon, Spitzer, & Williams, 1997) by trained psychology graduate students and research assistants. Interviewers were European American, Hispanic American, Asian American and Russian. They were not matched to participants by ethnicity. To be classified as “depressed,” participants were required to meet DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) criteria for a current Major Depressive Disorder. All individuals with MDD reported experiencing significant anhedonia. Control participants were excluded if they reported a lifetime history of any Axis I disorder. Depressed and control individuals with comorbid Axis I disorders, a lifetime history of panic disorder, social phobia, mania, hypomania, or psychotic symptoms, or a history of generalized anxiety disorder, substance abuse or dependence in the past six months were excluded from the study.

To assess severity of depression, interviewers completed the clinician-rated Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS, Hamilton, 1960), and participants completed the self-rated Beck Depression Inventory (BDI, Beck et al., 1979). These measures have adequate reliability and validity (Beck, Steer, & Carbin, 1988; Morriss, Leese, Chatwin, & Baldwin, 2008; Yin & Fan, 2000; but also see Bagby, Ryder, Schuller, & Marshall, 2004 for concerns regarding psychometric qualities of the HDRS). As expected, across cultural groups, depressed participants had higher levels of depressive symptoms as measured by the HDRS, F(1,62) = 173.74, p < .01, hp2 = .732, and the BDI, F(1,62) = 124.62, p < .01, hp2 = .68 compared to control participants (see Table 1). There were no significant differences between cultural groups in severity of depression (BDI: F(1,62) = .07, ns, hp2 = .001; HDRS: F(1,62) = .57, ns, hp2 = .01), and the cultural by diagnostic group interaction was not significant (BDI: F(1,62) = .93, ns, hp2 = .015; HDRS: F(1,62) = .60, ns, hp2 = .01).

Most depressed participants were not taking psychotropic medications at the time of the study (see Table 1). The proportion of depressed individuals taking a variety of psychotropic medications did not differ for European Americans and Asian Americans, χ2 (1, n = 32) = .34, ns. Consistent with previous reports (Rottenberg, Gross, & Gotlib, 2005), controlling for medication status did not alter our results, and therefore, we do not discuss medication status further.

Cultural Orientation

To ensure that participants were oriented to the cultures of interest, European Americans and Asian Americans completed the General Ethnicity Questionnaire-American version (Tsai, Ying, & Lee, 2000), and Asian Americans completed the General Ethnicity Questionnaire-Asian version. These questionnaires have adequate reliability and validity (see Tsai, Ying, & Lee, 2000) and allow for independent assessments of orientation to American and East Asian cultures, respectively.

Although Asian Americans reported being moderately oriented to Asian cultures, they were more oriented to American culture than to Asian cultures, F(1,29) = 6.29, p < .05, hp2 = .18. Asian Americans reported marginally lower orientation to American culture than European Americans, F(1,62) = 3.70, p = .06, hp2 = .06. There were no significant main effects (GEQ-American: F(1,62) = .58, ns, hp2 = .01; GEQ-Asian: F(1,29) = .60, ns, hp2 = .02) or interactions (GEQ-American: F(1,62) = .34, ns, hp2 = .01) involving depression. Thus, depressed and control Asian Americans reported moderate levels of familiarity with East Asian cultures, and high levels of familiarity with American culture. Because the GEQ questionnaires tap behavioral indices of cultural orientation, such as social interactions and exposure to media and language use, this pattern of cultural orientation is typical of Asian Americans residing in the U.S. Despite high levels of behavioral orientation to American culture, Asian Americans showed similar levels of identification (e.g., “Overall, I am Chinese/Korean...”) with East Asian (M = 3.62, SD = 0.98) and American (M = 3.50, SD = 1.14) cultures, F(1,29) = .09, ns. Thus, we were confident that we were successful in recruiting a bicultural sample of Asian Americans.

Procedure

Participants who met criteria for the study were invited to participate in the laboratory part of the study. Upon arrival, participants were informed that they were going to watch a film clip and that they would be videotaped during the task. After participants completed a packet of questionnaires including demographic data, self-rated depression severity, and cultural orientation, physiological sensors were attached to their hands and torso. Participants were asked to relax and clear their minds while focusing on a screen with a fixation cross for three minutes. This resting period provided a baseline against which to compare the effects of the film. Immediately after the resting baseline, participants completed an emotion inventory to report how they felt while relaxing. They then viewed the amusing film clip. During the task, participants were in the room alone, and written instructions were delivered by video. Immediately after the film clip, participants reported how they felt during the film.

The amusing film clip was approximately three minutes in length. The film was a slapstick comedy routine of an African American comedian describing his visit to the dentist. The clip was pre-tested for this study with two pilot samples that included European Americans and Asian Americans, using the criteria outlined by Gross and Levenson (1995). Across cultural groups, it elicited moderate levels of amusement, excitement, and happiness (pilot sample N = 67, aggregate M = 3.78 on a 0-8 Likert scale with 0 = “Not at all”; 8 = “The most in my life”, SD = 1.49; α = .78), and did not elicit significant levels of other emotions.

Dependent Variables

Emotional reactivity is a multi-component construct that is best captured by multi-method assessment of changes in behavior, experience and physiological reactivity (Levenson, 2003). We assessed facial emotional behavior, reported intensity of emotional experience, and physiological reactivity in response to the amusing film clip. These measures of emotional reactivity have been shown to be reliable and valid in prior studies that examined the effects of culture and/or depression on emotional reactivity (Fraguas et al., 2007; Mauss, Levenson, McCarter, Wilhelm, & Gross, 2005; Roberts, Levenson, & Gross, 2008; Rottenberg et al., 2002; Rottenberg, Wilhelm, Gross, & Gotlib, 2002; Soto, Levenson, & Ebling, 2005).

Facial behavior

Remotely controlled video cameras recorded participants’ facial behavior. In three cases, the record of facial behavior during the film was lost due to equipment failure.

Facial behavior was coded using Gross and Levenson's (1993) Emotional Expressive Behavior Coding System (EEB) (see Gross & John, 1995 for reliability and validity information). Enjoyment smiles were defined by the presence of bagging or wrinkling around the eyes (i.e., “smiling eyes”) and by the absence of any behaviors associated with negative affect. Non-enjoyment smiles were defined by the absence of “smiling eyes” and, unlike enjoyment smiles, could co-occur with displays of negative emotion. Three trained undergraduate coders blind to the study hypotheses, to the films shown, and to the diagnostic status of participants, scored occurrences of each type of smile during the study. The interrater reliability was acceptable for enjoyment (Intraclass r = .96), and non-enjoyment (Intraclass r of = .78) smiles. For cases where coders disagreed about their ratings, coders discussed their ratings to resolve the disagreements. When disagreements could not be resolved, the ratings of the coders were averaged.

Reported intensity of emotional experience

An inventory consisting of 23 emotion terms was administered after the baseline and after the film. For each of the emotion terms, participants used a 9-point rating scale (0 = “not at all”; 8 = “the most in my life”) to indicate how strongly they felt each emotion. As expected based on the film pilot data, the film clip elicited reports of high arousal positive emotion (amusement, excitement and happiness) compared to resting baseline (see Results section). A three-item composite of these emotion terms was used to measure reports of high arousal positive emotions during the film (α = .84).

Physiological measures

A system consisting of a computer, HPVEE software, and Coulbourne Lab Link V bioamplifiers was used to obtain continuous recording of participants’ physiological reactivity during the study.

We examined measures of cardiac (inter-beat interval, IBI), electrodermal (skin conductance level, SCL), vascular (finger temperature, TEM), and respiratory (intercycle interval, ICI) reactivity because they sample systems known to be important in positive and negative emotional reactivity (Boiten, Frijda, & Wientjes, 1994; Levenson, 2003)3. These measures show modest to moderate levels of stability and association with other measures of positive and negative emotional reactivity (Fahrenberg, Schneider, & Safian, 1987; Manuck et al., 1989; 1993; Simons, Losito, Rose, & MacMillan, 1983; Mauss et al., 2005) and have been used to examine positive emotional reactivity of European Americans and Asian Americans in prior research (Frazier, Strauss, Steinhauer, 2004; Tsai & Levenson, 1997).

To measure IBI, Beckman electrodes with Redux paste were placed in a bipolar configuration on opposite sides of each participant's chest. IBI was measured in milliseconds between successive R waves of the electrocardiogram. Higher levels of IBI indicate lower levels of physiological reactivity. To measure SCL, a constant-voltage device passed a small voltage between electrodes attached to the palmar surface of the middle phalanges of the first and third fingers of the non-dominant hand. SCL was measured in micro ohms. Higher levels of SCL indicate higher levels of physiological reactivity. To measure TEM, a thermistor was attached to the palmar surface of the distal phalanx of the fourth finger of the non-dominant hand. TEM was calibrated to 0 prior to baseline, and was measured in changes from that value in degrees Fahrenheit. Higher levels of TEM indicate lower levels of physiological reactivity. To measure ICI, a pneumatic bellow was placed around the participant's upper abdomen. ICI was measured in milliseconds between successive inspirations. Higher levels of ICI indicate lower levels of physiological reactivity.

Custom-designed data reduction software extracted raw data and produced waveform transformations, peak detection and graphic display for each channel. Trained research assistants removed periods affected by noise (e.g., due to factors such as participant movement), and calculated period averages for the baseline and the film. Change scores were calculated for each measure of emotional reactivity (facial behavior, reported intensity of emotional experience, physiological reactivity) by subtracting levels of these variables during resting baseline from levels of these variables during the amusing film (see Manuck et al., 1989; Rogosa, 1995 for a discussion of the advantages of change scores over other techniques of adjusting for baseline differences in emotional reactivity)4.

Results

A correlation matrix of baseline and film task levels of all dependent variables is presented in Table 2.

Resting baseline

To understand how participants reacted in the absence of emotional stimuli, we first examined positive emotional reactivity during the resting baseline. We conducted two-way univariate analyses of variance (ANOVAs) for continuous dependent variables and logistic regression for categorical variables, with diagnostic group (depressed, control) and cultural group (European American, Asian American) as between-subjects factors. We controlled for the number of comparisons conducted for each set of dependent variables (i.e., setting significance level at 0.5/2 = .025 for facial expressive behavior, 0.5/1 = 0.5 for reports of emotional experience, and 0.5/4 = .013 for physiological reactivity).

Facial expressive behavior

As expected, the baseline elicited very low levels of facial emotional behavior. Smiles were infrequent; therefore, we examined their occurrence rather than frequency. The strength of association between cultural and diagnostic group and the occurrence of enjoyment and non-enjoyment smiles was tested using logistic regression. There were no significant main effects of diagnostic group or cultural group and no interaction for enjoyment and non-enjoyment smiles (all main effects and interactions yielded the same Wald χ2(1, N = 66) = .00, ns).

Reports of emotional experience

During the baseline, depressed participants reported experiencing lower levels of positive emotions (M = 1.70; SD = 1.21), F(1,62) = 46.09, p < .01; hp2 = .09) than did control participants (M = 2.43; SD = 1.23). In addition, Asian American participants (M = 1.74; SD = 1.41) reported experiencing lower levels of positive emotions than did European American participants (M = 2.37; SD = 1.06) (F(1,62) = 6.49, p < .01; hp2 = .07). There were no significant diagnostic by cultural group interactions for reports of positive emotions (F(1,62) = .01, ns; hp2 = .00).

Physiological reactivity

There were no significant main effects or interactions involving cultural group or diagnostic group for IBI (diagnostic group: F(1,62) = 0.15, ns; hp2 = .002; cultural group: F(1,62) = 2.90, p = .09; hp2 = .05; interaction: F(1,62) = 3.01, p = .09; hp2 = .05), SCL (diagnostic group: F(1,62) = 0.85, ns; hp2 = .01; cultural group: F(1,62) = 3.24, p = .08; hp2 = .05; interaction: F(1,62) = 1.95, ns; hp2 = .03), TEM (diagnostic group: F(1,62) = 4.69, p = .03; hp2 = .07; cultural group: F(1,62) = 4.30, p = .04; hp2 = .07; interaction: F(1,62) = .16, ns; hp2 = .00), and ICI (diagnostic group: F(1,62) = 3.53, p = .07; hp2 = .06; cultural group: F(1,62) = 1.31, ns; hp2 = .02; interaction: F(1,62) = .47, ns; hp2 = .01) during the resting baseline.

In summary, there were differences between cultural groups and between diagnostic groups in reports of emotional experience during the resting baseline. Depressed participants reported feeling less positive than did control participants. Similarly, Asian American participants felt less positive than did European American participants. There were no significant baseline cultural group or diagnostic group differences in levels of facial expressive behavior or physiological reactivity.

Did the Amusing Film Clip Effectively Elicit Positive Emotion?

We first examined whether responses to the amusing film clip significantly differed from responses during resting baseline, using repeated-measure ANOVA. Participants showed more intense enjoyment (F(1,60) = 71.04, p < .001; hp2 = .54) and non-enjoyment smiles (F(1,60) = 77.90, p < .001; hp2 = .56), reported experiencing more intense positive emotion (F(1,62) = 78.63, p < .001; hp2 = .56), and showed greater physiological activation (decreases in IBI, F(1,62) = 12.02, p < .001; hp2 = .16, increases in SCL, F(1,62) = 40.03, p < .001; hp2 = .40, and decreases in TEM, F(1,62) = 28.19, p < .001; hp2 = .32) during the amusing film compared to baseline. Because there were no significant changes from baseline to the amusing film in ICI (F(1,62) = .99, ns; hp2 = .02), we will not discuss this measure further. These findings suggest that overall, the amusing film clip effectively elicited positive emotion compared to baseline.

Evidence for the Cultural Norm Hypothesis?

In order to test the cultural norm hypothesis, we conducted two-way univariate ANOVAs for each change score measure of emotional reactivity, with diagnostic group (depressed, control) and cultural group (European American, Asian American) as between-subjects factors. We controlled for the number of comparisons conducted for each set of dependent variables (i.e., setting significance level at 0.5/2 = .025 for facial expressive behavior, 0.5/1 = 0.5 for reports of emotional experience, and 0.5/3 = .017 for physiological reactivity). We then conducted planned one-tailed comparisons (European American: depressed vs. controls; Asian American: depressed vs. controls).

Facial expressive behavior5

A two-way (Diagnostic Group X Cultural Group) ANOVA conducted on change scores in enjoyment smiles yielded a main effect of diagnostic group, with depressed participants (M = 5.57; SD = 6.19) showing smaller increases in the number of enjoyment smiles than did control participants (M = 10.88; SD = 8.61), F(1,59) = 7.33, p < .01; hp2 = .11. Neither the main effect of cultural group nor the interaction of cultural and diagnostic groups was significant.

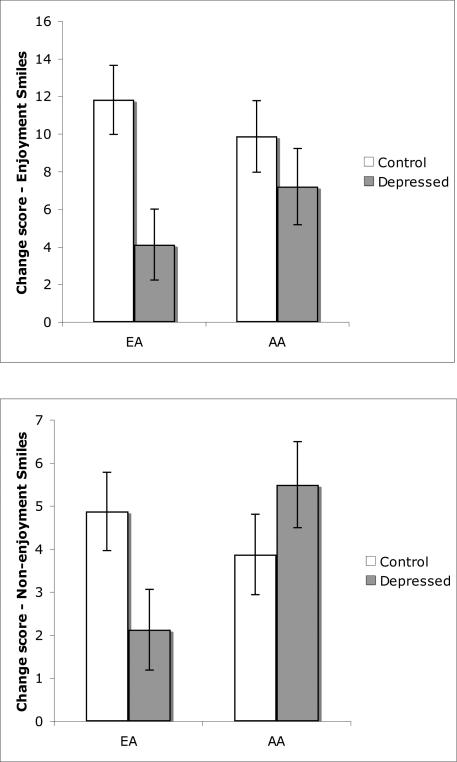

Neither the main effect of cultural group nor the main effect of diagnostic group was significant for change scores in non-enjoyment smiles. The interaction of cultural by diagnostic group, however, was significant, F(1,59) = 5.37, p < .025; hp2 = .08. Planned comparisons revealed that whereas depressed European Americans (M = 2.13; SD = 3.20) showed significantly smaller increases in their non-enjoyment smiles than did control European Americans (M = 4.88; SD = 4.57), t(59) = 2.68, p = .01; depressed Asian Americans (M = 5.50; SD = 3.65) tended to show greater levels of increases in their non-enjoyment smiles than control Asian Americans (M = 3.88; SD = 3.32), although these differences were not significant, t(59) = 1.18, ns, see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Change scores for enjoyment and non-enjoyment smiles during the amusing film clip. The bars in the figures indicate standard errors.

Thus, as predicted by the cultural norm hypothesis, depression was consistently associated with dampening of positive facial behavior for European Americans. For Asian Americans, depression was associated with the dampening of enjoyment smiles, but not non-enjoyment smiles.

Reports of emotional experience

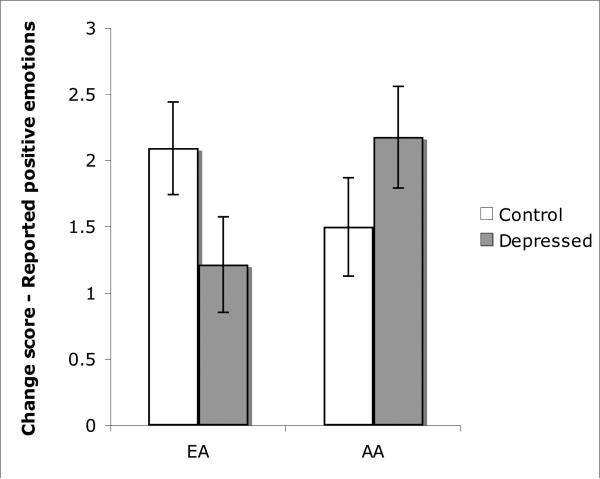

A two-way ANOVA conducted on change scores in reported positive emotion yielded a significant interaction of diagnostic and cultural groups, F(1,62) = 4.50, p < .05; hp2 = .07. Planned comparisons showed that whereas depressed European Americans (M = 1.22; SD = 1.67) reported smaller increases in reported positive emotions than did control European Americans (M = 2.09; SD = 1.42), t(62) = 1.75, p < .05, depressed (M = 2.18; SD = 1.50) Asian Americans tended show greater increases in reported positive emotions than control Asian Americans (M = 1.50; SD = 1.32), although these differences were not significant, t(62) = 1.27, ns, see Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Change scores for reported positive emotions during the amusing film clip. The bars in the figures indicate standard errors.

Again, as predicted by the cultural norm hypothesis, depression was associated with dampening of reported positive emotions for European Americans. In contrast, depressed and non-depressed Asian Americans reported similar levels of positive emotional experience.

Physiological reactivity

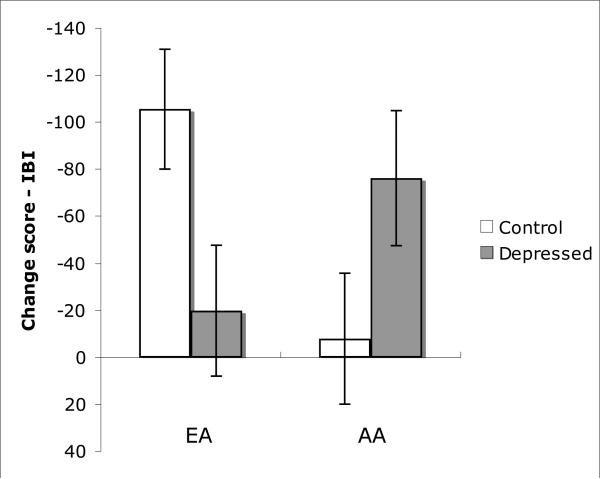

There were no significant main effects or interactions for change scores in SCL (cultural group: F(1,62) = 0.46, ns; hp2 = .01; diagnostic group: F(1,62) = 0.90, ns; hp2 = .02; interaction: F(1,62) = 0.18, ns; hp2 = .003), or TEM (cultural group: F(1,62) = 0.004, ns; hp2 = 0; diagnostic group: F(1,62) = 0.95, ns; hp2 = .02; interaction: F(1,62) = 0.20, ns; hp2 = .003)5. There were also no significant main effects of diagnostic (F(1,62) = 0.1, ns; hp2 = .002) or cultural group (F(1,62) = 0.56, ns; hp2 = .01) for IBI change scores. However, a two-way ANOVA conducted on IBI change scores5 yielded a significant interaction of diagnostic and cultural groups, F(1,62) = 7.84, p < .01; hp2 = .11. Larger decreases in IBI indicate increased cardiac activation in response to the amusing film. Planned comparisons revealed that whereas depressed European Americans (M = − 19.96; SD = 94.09) showed significantly smaller increases in cardiac activation than did control European Americans (M = −105.58; SD = 117.82), t(62) = 2.27, p < .05, depressed Asian Americans (M = −76.29; SD = 141.09) showed significantly larger increases in cardiac activation than did control Asian Americans (M = −8.02; SD = 83.74; see Figure 3), t(62) = 1.71, p < .05. Thus, as predicted by the cultural norm hypothesis, the effects of depression on cardiac reactivity to the amusing film differed by cultural group.

Figure 3.

Change scores for IBI during the amusing film clip. The bars in the figures indicate standard errors.

Across cultural groups, depressed and control individuals did not differ in electrodermal reactivity or finger temperature, suggesting that these aspects of emotional reactivity may not be affected by depression for these cultural groups. Although one previous study has demonstrated that depression is associated with dampened physiological reactivity to elicitors of positive emotion (Tsai, Pole, Levenson, & Muñoz, 2003), other studies have not shown this pattern (Rottenberg et. al., 2002; 2005). Indeed, previous studies have shown that the effects of depression on physiological reactivity tend to be small in magnitude (see Bylsma et al., 2008). It is possible that the effects of depression on cardiac, electrodermal and vascular activity differ by factors such as cultural group, severity of depression, and the nature of the emotion elicitation task.

In summary, we observed some support for the cultural norm hypothesis: among European Americans, depression was associated with less intense smiles (enjoyment and non-enjoyment), less intense reports of positive emotions, and lower cardiac activation. In contrast, among Asian Americans, depression was associated with greater cardiac activation. Similarly, depressed Asian Americans tended to show greater increases in reports of positive emotions and non-enjoyment smiles than did control Asian Americans, although these differences were not significant, perhaps due to the small sample size. No differences in skin conductance or finger temperature emerged for depressed and control participants across cultural groups.

Discussion

In our previous work (Chentsova-Dutton et al., 2007), we demonstrated that the effects of depression on negative emotional reactivity varied for European Americans and Asian Americans. Whereas depressed European Americans showed dampened negative emotional responses compared to healthy controls, depressed Asian Americans showed increased negative emotional responses compared to healthy controls. Similarly, the present study found that depressed European Americans showed dampened positive emotional responses compared to healthy controls, and depressed Asian Americans showed similar or even increased positive emotional responses compared to healthy controls. Together, these separate studies suggest that the effects of depression on positive and negative emotional reactivity vary across cultures. Although the magnitude of the observed differences was modest across both studies, this pattern of results suggests that depression is associated with dampened emotions in the cultures that encourage open or even exaggerated emotional expression, but not in cultures that encourage emotional moderation.

Importantly, the effects of depression on positive emotional reactivity varied by component of emotional response. For instance, depressed European Americans showed fewer enjoyment and non-enjoyment smiles, reported experiencing less intense positive emotion, and showed less intense cardiac activation than did control European Americans. This pattern, however, was not observed for electrodermal or vascular activation. Similarly, depressed Asian Americans showed greater cardiac reactivity than did healthy controls, but did not show differences in smiles, reports of positive emotion, or the other measures of physiological response. The results obtained for Asian Americans are novel and await further replication. If replicated, they may indicate that although depression is associated with increased physiological reactivity to positive emotional stimuli for Asian Americans, this pattern is not translated into significant increases in facial behavior and reports of positive emotions. Alternatively, it is possible that using stronger elicitors of positive emotions, such as more intense film clips, social interactions or valued rewards may produce more consistent pattern of results across components of positive emotional reactivity.

Intriguingly, data observed for depressed Asian Americans contradicted their clinical reports of reduced ability to experience interest and pleasure. This group was at least as able – and possibly more able - to experience positive emotions in response to a pleasant task as control Asian Americans. Recall of emotional experiences prompted by clinical interview questions may reflect what one thinks one generally feels or ought to feel, and can differ substantially from in-the-moment reports of emotions (Robinson & Clore, 2002). Our results raise the possibility that clinical reports of loss of pleasure among depressed Asian Americans may not accurately reflect their in-the-moment positive emotional reactivity. Future studies need to investigate the relationship between retrospective reports of anhedonia and on-line positive emotional reactivity among Asian Americans. It is also possible that Asian Americans’ clinical reports of anhedonia refer to inability to experience low arousal positive states – such as calmness and tranquility - that are particularly valued in East Asian cultures (Tsai et al., 2006). It would be important to examine emotional reactivity to elicitors of low arousal positive emotions in future work.

The interaction between cultural and diagnostic groups emerged against a backdrop of similarities across cultural groups in the effects of depression on positive and negative emotional reactivity during the resting baseline. Consistent with our previous findings (Chentsova-Dutton et al., 2007), in the absence of an emotional stimulus, depressed European American and Asian American individuals reported less intense positive emotions than did control individuals. In addition, European Americans reported more intense positive emotion than did Asian Americans during baseline, suggesting that responses during baseline may reflect overall differences in mood.

Limitations and future directions

This study has a number of limitations. First, our sample size was small. Partial eta squared values obtained for the cultural by diagnostic group interactions were in the small to moderate effect size range. As a consequence, the power observed in this study was modest in magnitude, ranging from .61 to .77. Thus, it is possible that the study was a conservative test of the hypothesis and failed to detect differences in positive emotional reactivity that were more subtle in nature (e.g., cultural by diagnostic group interaction in enjoyment smiles). Future research will need to utilize larger samples and examine clinical and diagnostic significance of the detected differences in positive emotional reactivity.

Second, we did not address the causal nature of the relationship between major depression and positive emotional reactivity. We do not know whether symptoms of depression contribute to changes in positive emotional reactivity, or vise versa. Future longitudinal research needs to examine how the associations between these constructs unfold over time across cultures, focusing on individuals at risk for depression, such as children of depressed parents or remitted individuals with a history of major depression.

Third, scholars of culture and emotion have expressed caution about diagnostic overreliance on emotional symptoms of depression, particularly anhedonia (Kotchemidova, 2005; Lutz, 1985; Mesquita & Walker, 2003). Although all of our participants met criteria for current major depressive disorder and endorsed anhedonia, it is possible that some depressed Asian Americans may not meet the DSM-IV criteria for depression because they may present with a pattern of emotional dysregulation that is different from that observed for depressed European Americans. Thus, our sample of depressed Asian Americans may not have been representative of Asian Americans who experience symptoms of depression. That said, given that Asian Americans did meet Western criteria for depression, the differences are all the more striking. Future studies need to examine positive emotional reactivity among individuals who report significant impairment due to depressive symptoms in the absence of anhedonia.

Fourth, the depressed participants in this study were relatively homogenous in their endorsement of the emotional symptoms of major depression. All of them reported experiencing clinically significant levels of anhedonia and depressed mood. In the future, it will be important to examine the emotional reactivity of depressed individuals who present primarily with depressed mood or primarily with anhedonia and blunted affect. This research would have implications for diagnosing and treating emotional symptoms of depression in individuals with different subtypes of this disorder.

Finally, the cultural heterogeneity of Asian American sample presented another significant limitation. Future studies need to recruit larger samples of depressed Asian Americans from specific cultural backgrounds (e.g., Chinese, Japanese or Korean) in order to examine whether individuals from different East Asian cultures differ in their positive emotional reactivity.

Notably, because Asian Americans in this study were oriented to East Asian as well as American cultures, the study was a conservative test of the cultural norm hypothesis. Also, the dynamic constructivist perspective (e.g., Hong, Benet-Martinez, Chiu, & Morris, 2003; Hong, Morris, Chiu, & Benet-Martinez, 2000) suggests that individuals oriented to more than one culture are better able to shift between enacting different cultural norms depending on which is cued by the situation. Thus, the responses of Asian American individuals in this study may have been shaped by situational cues to a greater extent than those of European American individuals. Future work should include individuals in East Asian cultures, as well as larger samples of recent immigrants versus U.S.-born Asian Americans in order to examine whether the observed differences are more pronounced in less acculturated samples, and help us better understand the role of acculturation and bicultural orientation in positive emotional reactivity of depressed individuals.

Despite these limitations, this study provides further evidence for the cultural norm hypothesis by extending previous findings observed for negative emotions (Chentsova-Dutton et al., 2007) to positive emotions. Taken together, the results of the two studies suggest that, instead of blunting affect, depression appears to minimally alter or even heighten negative and positive emotional responses among Asian Americans. Thus, rather than rendering reports and displays of emotion unreliable, different cultural norms regarding emotional experience and expression may result in predictable differences in emotional responses among depressed individuals. Consequently, Western clinicians may find assessment and treatment of depression difficult in Asian Americans not because Asian Americans moderate and control their emotional responses, but because depressed Asian Americans show a different pattern of positive and negative emotional reactivity than do depressed European Americans. Together, these findings take us one step closer to understanding how cultural factors shape the experience and expression of depression.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the NARSAD Young Investigator Award awarded to Jeanne Tsai and National Institute of Mental Health Grant MH59259 awarded to Ian Gotlib. The authors would like to thank Cheryl Hahn, Chanelle Hill, Eunice Hwong, Katherine Lillehei, Kate Rooney, Miyuki Takagi, and Albert Wang for their assistance on the project and James Gross and the Culture Co-Lab for their helpful comments on earlier versions of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Studies indicate that individuals of different East Asian backgrounds and generational statuses hold similar values regarding emotional moderation (Kim, Alkinson, & Yang, 1999; Kim, Yang, Atkinson, Wolfe, & Hong, 2001).

We report partial eta squared, hp2 ,as a measure of effect size (Tabachnick & Fidell, 1989).

These physiological indices differ in their association with sympathetic and parasympathetic activation of the ANS. IBI, TEM and ICI are jointly influenced by sympathetic and parasympathetic activation, whereas SCL is primarily influenced by sympathetic activation (see Cacioppo, Tassinary, & Berntson, 2007). In addition, individuals have more voluntary control over ICI compared to other aspects of physiological reactivity. Thus, low levels of association are typically observed between different physiological measures (Lacey, 1967), particularly when inter-individual associations are examined (Lazarus, Speisman, & Mordkoff, 1963). In line with previous research, different measures of physiological reactivity were not significantly associated in this study. Therefore, we examined each index separately instead of forming a composite of physiological reactivity to the amusing film.

Using covariance analysis to control for the baseline levels of emotional reactivity did not affect the findings for any of the reported main effects or interactions.

Change scores in enjoyment and non-enjoyment smiles, IBI, and TEM showed minor violation of normal distribution. Although ANOVA tends to be robust to violations of normal distribution assumption (Weiss, 2005), we have examined all contrasts using non-parametric Mann-Whitney U tests to ensure that our results were not affected by these violations. In each case, the results obtained with non-parametric tests were identical to those obtained with ANOVA.

References

- Aldwin C, Greenberger E. Cultural differences in the predictors of depression. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1987;15:789–813. doi: 10.1007/BF00919803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen NB, Trinder J, Brennan C. Affective startle modulation in clinical depression: Preliminary findings. Biological Psychiatry. 1999;46:542–550. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder. 4th ed. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bagby RM, Ryder AG, Schuller DR, Marshall MB. The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale: Has the gold standard become a lead weight? American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161(12):2163–2177. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery G. Cognitive therapy for depression. Guilford; New York: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer R, Carbin M. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review. 1988;8:77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Bellah RN, Madsen R, Sullivan WM, Swindler A, Tipton SM. Habits of the heart: Individualism and commitment in American life. Harper & Row, Publishers; New York: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Boiten FA, Frijda NH, Wientjes CJ. Emotions and respiratory patterns: Review and critical analysis. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 1994;17:103–128. doi: 10.1016/0167-8760(94)90027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond MH. Beyond the Chinese face. Oxford University Press; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bylsma LM, Morris BH, Rottenberg J. A meta-analysis of emotional reactivity in Major Depressive Disorder. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:676–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Tassinary LG, Berntson GG. Handbook of Psychophysiology. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Chentsova-Dutton YE, Chu JP, Tsai JL, Rottenberg J, Gross JJ, Gotlib IH. Depression and emotional reactivity: variation among Asian Americans of East Asian descent and European Americans. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:776–785. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.4.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chentsova-Dutton Y, Tsai JL. Gender differences in emotional responding among European Americans and Hmong Americans. Cognition and Emotion. 2007;21:162–181. [Google Scholar]

- Eid M, Diener E. Norms for experiencing emotions in different cultures: Inter- and intranational differences. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 2001;81(5):869–885. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.81.5.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahrenberg J, Schneider HJ, Safian P. Psychophysiological assessments in a repeated-measurement design extending over a one-year interval: trends and stability. Biological Psychology. 1987;24:49–66. doi: 10.1016/0301-0511(87)90099-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for DSM–IV Axis I disorders (SCID–I), user's guide. American Psychiatric Press; Washington, DC: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fraguas R, Jr., Marci C, Fava M, Iosifescu DV, Bankier B, Loh R, Dougherty DD. Autonomic reactivity to induced emotion as potential predictor of response to antidepressant treatment. Psychiatry Research. 2007;151:169–172. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier TW, Strauss ME, Steinhauer SR. Respiratory sinus arrhythmia as an index of emotional response in young adults. Psychophysiology. 2004;41:75–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8986.2003.00131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehricke J-G, Fridlund AJ. Smiling, frowning, and autonomic activity in mildly depressed and nondepressed men in response to emotional imagery of social contexts. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 2002;94:141–151. doi: 10.2466/pms.2002.94.1.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, John OP. Revealing feelings: Facets of emotional expressivity in self-reports, peer ratings, and behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;72:435–448. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.72.2.435. GROSS/JOHN 1993??? [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, John OP. Mapping the domain of expressivity: Multi-method evidence for a hierarchical model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:170–191. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.1.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, Richards JM, John OP. Emotion regulation in everyday life. In: Snyder DK, Simpson JA, Hughes JN, editors. Emotion regulation in families: Pathways to dysfunction and health. American Psychological Association; Washington DC: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, Levenson RW. Emotional suppression: Physiology, self-report, and expressive behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;64:970–986. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.64.6.970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, Levenson RW. Emotion elicitation using films. Cognition and Emotion. 1995;9:87–108. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heine SJ, Lehman DR, Markus HR, Kitayama S. Is there a universal need for positive self-regard? Psychological Review. 1999;106:766–794. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.106.4.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Y, Benet-Martinez V, Chiu C, Morris M. Boundaries of cultural influence: Construct activation as a mechanism for cultural differences in social perception. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2003;34:453–464. [Google Scholar]

- Hong Y, Morris MW, Chiu C, Benet-Martinez V. Multicultural minds: A dynamic constructivist approach to culture and cognition. American Psychologist. 2000;55:709–720. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.7.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu J. The Chinese family: Relations, problems, and therapy. In: Tseng WS, Wu DYH, editors. Chinese culture and mental health. Academic Press; Orlando: 1985. pp. 95–112. [Google Scholar]

- Iwata N, Roberts CR, Kawakami N. Japan–US comparison of responses to depression scale items among adult workers. Psychiatry Research. 1995;58:237–245. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(95)02734-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata N, Umesue M, Egashira K, Hiro H, Mizoue T, Mishima N, Nagata S. Can positive affect items be used to assess depressive disorders in the Japanese population? Psychological Medicine. 1998;28:153–158. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata N, Buka S. Race/ethnicity and depressive symptoms: A cross-cultural/ethnic comparison among university students in East Asia, North and South America. Social Science & Medicine. 2002;55(12):2243–2252. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanazawa A, White PM, Hampson SE. Ethnic variation in depressive symptoms in a community sample in Hawaii. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2007;13(1):35–44. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim BSK, Atkinson DR, Yang PH. The Asian Values Scale: Development, factor analysis, validation, and reliability. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1999;46:342–352. [Google Scholar]

- Kim BSK, Yang PH, Atkinson DR, Wolfe MM, Hong S. Cultural value similarities and differences among Asian American ethnic groups. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2001;7:343–361. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.7.4.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A. Neurasthenia and depression: A study of somatization and culture in China. Culture, Medicine & Psychiatry. 1982;6(2):117–190. doi: 10.1007/BF00051427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotchemidova C. From good cheer to ‘Drive-by smiling’: A social history of cheerfulness. Journal of Social History. 2008;39:5–37. [Google Scholar]

- Lacey JI. Somatic response patterning and stress: Some revisions of activation theory. In: Appley MH, Trumbull R, editors. Psychological stress: Issues in research. Appleton-Century-Crofts; New York: 1967. pp. 14–42. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Speisman JC, Mordkoff MA. The relationship between autonomic indicators of psychological stress: Heart rate and skin conductance. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1963:19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Leong FTL, Lau ASL. Barriers to providing effective mental health services to Asian Americans. Mental Health Services Research. 2001;3:201–214. doi: 10.1023/a:1013177014788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenson RW. Blood, sweat and fears: The autonomic architecture of emotion. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2003;1000:348–366. doi: 10.1196/annals.1280.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz C. Depression and the translation of emotional worlds. In: Kleinman A, Good B, editors. Culture and depression: Studies in the anthropology and cross-cultural psychiatry of affect and disorder. University of California Press; Berkeley: 1985. pp. 63–100. [Google Scholar]

- Manuck SB, Kamarck TW, Kasprowicz AS, Waldstein SR. Stability and patterning of behaviorally evoked cardiovascular reactivity. In: Blascovich JJ, Katkin ES, editors. Cardiovascular reactivity to psychological stress and disease. American Psychological Association; Washington DC: 1993. pp. 111–134. [Google Scholar]

- Manuck SB, Kasprowicz AL, Monroe SM, Larkin KT, Kaplan JR. Psychophysiological reactivity as a dimension of individual differences. In: Schneiderman N, Weiss SM, Kaufmann PG, editors. Handbook of research methods in cardiovascular behavioral medicine. Plenum Press; New York: 1989. pp. 365–392. [Google Scholar]

- Markus HR, Kitayama S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review. 1991;98:224–253. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto D. Cultural similarities and differences in display rules. Motivation and Emotion. 1990;14(3):195–214. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto D, Yoo SH, Fontaine J, Anguas-Wong AM, Ariola M, Ataca B, Bond MH, et al. Mapping expressive differences around the world: The relationship between emotional display rules and individualism v. collectivism. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2008;39:55–74. [Google Scholar]

- Mauss IB, Levenson RW, McCarter L, Wilhelm FH, Gross JJ. The tie that binds? Coherence among emotion experience, behavior, and physiology. Emotion. 2005;5:175–190. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.5.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesquita B, Karasawa M. Different emotional lives. Cognition and Emotion. 2002;16:127–141. [Google Scholar]

- Mesquita B, Walker R. Cultural difference in emotions: A context for interpreting emotional experiences. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2003;41:777–793. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(02)00189-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morriss R, Leese M, Chatwin J, Baldwin D. Inter-rater reliability of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale as a diagnostic and outcome measure of depression in primary care. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2008;111:204–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker G, Cheah Y-C, Roy K. Do the Chinese somatize depression? A cross-cultural study. Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2001;36:2001. doi: 10.1007/s001270170046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renneberg B, Heyn K, Gebhard R, Bachmann S. Facial expression of emotions in borderline personality disorder and depression. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2005;36:183–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts NA, Levenson RW, Gross JJ. Cardiovascular costs of emotion suppression cross ethnic lines. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2008;70:82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MD, Clore GL. Belief and feeling: Evidence for an accessibility model of emotional self-report. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128(6):934–960. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.6.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogosa D. Myths and methods: “Myths about longitudinal research” plus supplemental questions. In: Gottman JM, editor. The analysis of change. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Roland A. Psychoanalytic therapy with Asians and Asian Americans. In: Georgiopoulos AM, Rosenbau JF, editors. Perspectives in Cross-Cultural Psychiatry. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2005. pp. 145–156. [Google Scholar]

- Rottenberg J, Gross JJ, Gotlib IH. Emotion context insensitivity in major depressive disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:627–639. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottenberg J, Kasch KL, Gross JJ, Gotlib IH. Sadness and amusement reactivity differentially predict concurrent and prospective functioning in major depressive disorder. Emotion. 2002;2:135–146. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.2.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottenberg J, Wilhelm FH, Gross JJ, Gotlib IH. Respiratory sinus arrhythmia as a predictor of outcome in major depressive disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2002;71:265–272. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00406-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell JA, Yik MSM. Emotion among the Chinese. In: Bond MH, editor. The handbook of Chinese psychology. Oxford University Press; Hong Kong: 1996. pp. 166–188. [Google Scholar]

- Ryder AG, Yang J, Zhu X, Yao S, Yi J, Heine SJ, Bagby RM. The cultural shaping of depressive symptoms: Somatization and psychologization in China and North America. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:300–313. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.2.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherer KR, Matsumoto D, Wallbott HG, Kudoh T. Emotional experience in cultural context: A comparison between Europe, Japan, and the United States. In: Scherer KR, editor. Facets of emotion: Recent research. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; Hillsdale, NJ, England: 1988. pp. 5–30. [Google Scholar]

- Simons RF, Losito BD, Rose SC, MacMillan FW. Electrodermal nonresponding among college undergraduates: Temporal stability, situational specificity, and relationship to heart rate change. Psychophysiology. 1983;20:558–567. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1983.tb03002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon GE, VonKorff M, Picvinelli M, Fullerton C, Ormel J. An international study of the relation between somatic symptoms and depression. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;18:1329–1335. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910283411801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan DM, Strauss ME, Quirk SW, Sajatovic M. Subjective and expressive emotional responses in depression. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1997;46:135–141. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(97)00097-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto JA, Levenson RW, Ebling R. Cultures of moderation and expression: Emotional experience, behavior, and physiology in Chinese Americans and Mexican Americans. Emotion. 2005;5:154–165. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.5.2.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 2nd ed. Harper & Row; New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai JL, Chentsova-Dutton Y, Freire-Bebeau L, Przymus DE. Emotional expression and physiology in European Americans and Hmong Americans. Emotion. 2002;2(4):380–397. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.2.4.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai JL, Knutson B, Fung HH. Cultural variation in affect valuation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;90:288–307. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.2.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai JL, Levenson RW. Cultural influences of emotional responding: Chinese American and European American dating couples during interpersonal conflict. Journal of Cross Cultural Psychology. 1997;28(5):600–625. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai JL, Pole N, Levenson RW, Munoz RF. The effects of depression on the emotional responses of Spanish speaking Latinas. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2003;9:49–63. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.9.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai JL, Ying Y, Lee PA. The meaning of “being Chinese” and “being American”: Variation among Chinese American young adults. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2000;31:302–322. [Google Scholar]

- Uchida Y, Norasakkunkit V, Kitayama S. Cultural constructions of happiness: Theory and empirical evidence. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2004;5:223–239. [Google Scholar]

- Waza K, Graham AV, Zyzanski SJ, Inoue K. Comparison of symptoms in Japanese and American depressed primary care patients. Family Practice. 1999;16(5):528–533. doi: 10.1093/fampra/16.5.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss DJ. Analysis of variance and functional measurement. Oxford University Press; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wierzbicka A. Talking about emotions: Semantics, culture and cognition. Cognition and Emotion. 1992;6:285–319. [Google Scholar]

- Wierzbicka A. Emotions across languages and cultures: Diversity and universals. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Yen S, Robins CJ, Lin N. A cross-cultural comparison of depressive symptom manifestation: China and the United States. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68(6):993–999. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.6.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin P, Fan X. Assessing the reliability of Beck Depression Inventory scores: Reliability generalization across studies. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2000;60:201. [Google Scholar]