Abstract

Poor antidepressant adherence is a significant issue in depression treatment that adversely affects treatment outcomes. While being a common problem, it tends to be more common among Latinos. To address this problem, the current study adapted a Motivational Interviewing (MI) intervention to improve adherence among Latinos with depression. The adaptation process included six focus groups that elicited participants’ perspectives (N = 30), applying the intervention with test cases (N = 7) to fine tune the intervention, and eliciting feedback on the intervention (N = 5). The findings generated from these adaptation phases are described, along with a case example. Examples of adaptations to the MI included reframing antidepressant adherence as a way to luchar (struggle) against problems, focusing on motivation for improving depression and not just medication, refining methods for imparting antidepressant information, and inclusion of personalized visual feedback on dose-taking. The findings provide a description of the antidepressant issues experienced by a group of Latinos, as well as considerations for applying MI with this population. The intervention remained grounded in MI principles, but was contextualized for this Latino group.

Keywords: Motivational Interviewing, Latinas/Latinos, antidepressants, culturally-adapted interventions, major depression

Adaptation of a Motivational Interviewing Intervention to Improve Antidepressant Adherence among Latinos

Major depression is one of the most prevalent psychiatric disorders (Kessler et al., 2003; Vega et al., 1998) and has been estimated to be a leading cause of disability worldwide (Murray & Lopez, 1996). Antidepressants have been one of the front line treatments for major depression (NIMH, 2003), but successful treatments have their challenges. One such challenge is poor antidepressant adherence, with approximately three quarters of individuals prematurely discontinuing treatment (Olfson, Marcus, Tedeschi, & Wan, 2006). While antidepressant nonadherence is common overall, it is more common among Latinos (Olfson et al., 2006; Sleath, Rubin, & Huston, 2003). The lower adherence is noteworthy given its negative affect on treatment outcomes (Melfi et al., 1998). Given that racial/ethnic differences are associated with varying rates of antidepressant adherence (Olfson et al., 2006), it is important to understand the issues faced by specific populations. Improving antidepressant adherence among US racial/ethnic minority groups, such as Latinos, may help reduce mental health disparities (DHHS, 2001).

Motivational Interviewing

Cultural competence requires thoughtful consideration for selecting the intervention to improve antidepressant adherence among Latinos (Rogler, Malgady, Costantino, & Blumenthal, 1987). Accordingly, a number of considerations point to the potential utility of Motivational Interviewing (MI). MI is well-suited to help patients develop motivation for issues that are characterized by “resistance” or ambivalence. Also, MI emphasizes working within patients' values and is therefore conducive to understanding cultural differences.

MI and ambivalence

MI was developed within the field of addictions and is defined as a “patient-centered, directive method for enhancing intrinsic motivation to change by exploring and resolving ambivalence” (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). Rather than assuming that patients entered treatment in a pathological state of denial, it assumed that patients who abused substances were ambivalent about changing. For example, these patients may vacillate in their treatment motivation despite being well aware of the significant consequences of their substance use.

Because MI was designed to help patients to resolve ambivalence for change, the approach seems well-suited for improving antidepressant adherence. Ambivalence appears to be similarly salient in antidepressant adherence, where patients are faced with a multitude of conflicting variables (treatment motivation, side-effects, therapeutic alliance, stigma, poor treatment response; Demyttenaere, Van Ganse, Gregoire, Gaens, & Mesters, 1998; Keller, Hirschfeld, Demyttenaere, & Baldwin, 2002; Sirey, Bruce, Alexopoulos, Perlick, Friedman et al., 2001; Sleath et al., 2003). Such negative influences have also been reported among Latinos (Marcos & Cancro, 1982; Sanchez-Lacay et al., 2001). This array of conflicting motivators may lead to profound ambivalence similar to that observed with substance-related disorders.

MI’s cultural compatibility

MI’s emphasis on patient values may be especially appropriate for applications with racial/ethnic minorities such as Latinos (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). MI emphasizes values by aligning behavior change within the context of personal ideals and goals. Successfully applying MI for antidepressant adherence among Latinos would require an understanding of the values that are relevant for individuals in a particular social context. This includes understanding the value conflicts that are experienced when undergoing antidepressant treatment. Accordingly, some evidence points to an advantage for MI with racial/ethnic minorities. Despite some limitations in reporting, a meta-analysis of MI reported higher effect sizes for minority populations (Hettema et al., 2005).

Culturally Adapting Interventions

Culturally-relevant interventions have received attention for their potential to help reduce mental health racial/ethnic disparities (Vega et al., 2007). One strategy for adapting interventions has focused on drawing from the literature of empirically supported treatments (EST), developed primarily among non-minority populations (Miranda, Nakamura, & Bernal, 2003). The strategy emphasizes the cultural adaptation of the EST’s to match the needs of specific racial/ethnic groups. A recommended methodological framework for such adaptation has been a mixed-method approach (i.e., quantitative and qualitative methodologies; Napoles-Springer & Stewart, 2006). This is due to the discovery-oriented capabilities of qualitative methods, which richly describe sociocultural complexities from participants’ perspectives (Bernal & Scharron-del-Rio, 2001). These approaches can then be combined with quantitative methodologies.

A discussion on the meaning of culturally adapting treatments is warranted. The treatment adaptation debate has involved a tension between retaining a treatment’s core ingredients (i.e., treatment fidelity) and the need to ensure relevance to specific cultural groups (i.e., culturally-responsive; Castro, Barrera, & Martinez, 2004). Consistent with the recommendations of Miranda et al. (2003), treatment adaptation is viewed as a balance between treatment fidelity and cultural-responsiveness (Backer, 2001). For example, cognitive-behavioral therapy would still emphasize cognitive and behavioral principles, but be contextualized by the thoughts, experiences, and behaviors of a specific population (Interian & Diaz-Martinez, 2007). Thus, cultural adaptation of MI should seek to maintain its core ingredients, such as a client-centered philosophy, empathy, rolling with resistance, supporting efficacy, and elicitation of change talk, to name a few examples (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). However, its adaptation should deliver these ingredients in a way that is compatible with language, phraseology, attitudes, behaviors, preferences, and social context. By ensuring compatibility along these domains, interventions can have greater social validity and thereby increase the likelihood of engagement and retention (Lau, 2006).

The purpose of the current manuscript is to describe the application of a qualitative methodology for adapting an MI intervention for improving antidepressant adherence among Latinos. The qualitative methodology pursued a number of broad questions that helped adapt the MI. What are the different aspects of Latino patients’ experiences with antidepressants and what are the sources of ambivalence associated with these experiences? How does their social context contribute to ambivalence for taking antidepressants? Also, what are some common values reported by Latino patients and how do they relate to antidepressant attitudes? Understanding important values can provide a useful source of motivation to be drawn from during MI counseling. Other inquiries pursued by the current methodology focused on the specific MI techniques that were most likely to be helpful. For example, of the MI techniques pursued in the pilot study, which ones seemed to be most effective and well-received by participants? The manuscript describes findings pertaining to these issues and finishes with a case example to illustrate the MI approach.

Methods

Overview of Methodology

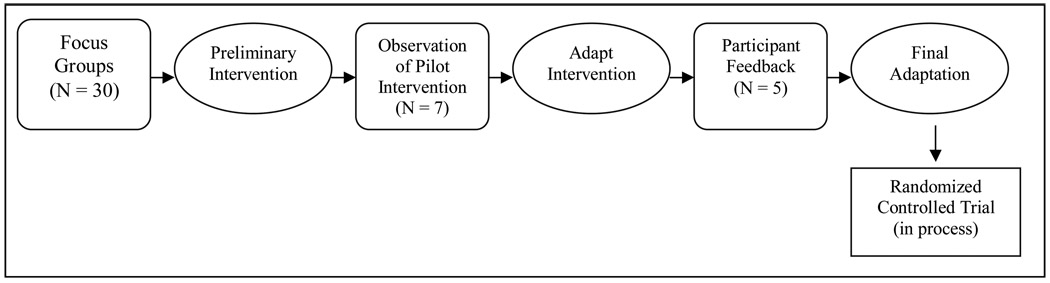

Figure 1 provides an overview of the steps taken to culturally adapt the intervention. This began with six focus groups that aimed to describe antidepressant adherence from participants’ perspectives, identify key issues that needed to be accounted for by the MI intervention, and understand the sociocultural context of adherence. The intervention was subsequently piloted with seven patients, which allowed for clinical observations that helped refine the approach. Finally, participant feedback on the intervention was generated with a focus group for those who received the intervention, which contributed to additional refinements. All procedures of the study, including focus groups and the intervention, were conducted in Spanish. However, the quotes provided were translated into English.

Figure 1.

Overview of Cultural Adaptation Methodology

Participants

All phases of this study focused on a group of Latinos receiving antidepressants in an urban area of Central New Jersey, which has approximately three times the number of Latinos than the national average (Ramirez & de la Cruz, 2002; US Census, 2000). Important to the cultural context of the city are migration and socioeconomic status, given a rapid influx of Latino immigrants. Also, economic issues are important to this Latino group, as they frequently are the motivators for immigration a substantial portion of the population lives below the poverty line.

The Latinos in this study were receiving antidepressants in a community mental health center (CMHC). The CMHC was a centrally-located, community-based setting with very feasible transportation to the clinic. Participants in all phases completed an informed consent procedure approved by the university IRB. All phases of the research were conducted in the community-based CMHC and scheduling was arranged according to participants’ needs.

Preliminary Focus Groups

Inclusion criteria for the focus groups were (a) self-reported depression history, (b) history of antidepressant use, (c) Latino ethnicity, and (d) at least 18 years of age. These criteria were broadly inclusive to enhance the external validity of the information gathered about antidepressant experiences. Participants were referred to the study by the CMHC clinicians treating their depression, who described the focus groups and determined their patients’ interest. Also, some recruitment occurred via flyers posted in the CMHC. Forty-eight participants were referred to the preliminary focus group phase. An additional three self-referred via recruitment flyers, resulting in total of 51 candidates. Interested participants were contacted by the research team by telephone and screened for the eligibility criteria. This recruitment process occurred during the two month period between April and June of 2006.

Of the 51, one person declined to participate, four were excluded due to reporting no previous experience with antidepressant medications, and 16 were not enrolled due to difficulty contacting or scheduling. This resulted in a total of 30 individuals who participated in a total of six focus groups. These participants completed a demographic questionnaire and the first author (AI) facilitated the focus groups using a discussion guide (Appendix) that was formulated to elicit positive and negative aspects of participants’ antidepressant experiences, as well as information regarding values and social context. No objective measures of depression were administered for the preliminary focus groups. All groups were of 90 – 120 minute duration and were audio recorded for subsequent analysis. Participants were compensated $75 for their involvement.

Focus group analysis

Each group’s audio recording was transcribed into text and imported into ATLAS.ti, a qualitative analysis software program, and analyzed using a grounded theory approach (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). This is an approach that systematically describes data in such a way that draws from the data, rather than from preconceived theories or concepts. The first step in the analysis was to describe the phenomena of antidepressant adherence among Latinos with depression. Towards this end, two Latino raters (AI & IM) independently read through each transcript multiple times. Each reading helped identify emerging concepts or codes. No new concepts emerged after the fourth focus group. The raters arrived at a final list of concepts or codes by consensus and utilized that final list to code all of the transcripts. In addition, the raters reviewed all instances of codes and determined where there was concurrence or non-concurrence between the raters. When a non-concurrence occurred, the instance of text was discussed and the discrepancy was resolved by consensus. The result of this process was that the transcripts were thoroughly coded and the concepts utilized were critically evaluated. The concepts were analyzed by describing their varying properties. For example, the code of “family influence” was analyzed to capture the various types of influences. In the second step, the number of times that codes co-occurred within the same statement was examined, allowing for a visualization of how concepts were interrelated. For example, a high co-occurrence between “general medical conditions” and “medication fears” codes highlighted their interplay and resulted in a description of how having co-morbid medical conditions contributed to medication fears. In the third step, the key issues were conceptualized within an MI framework, so that they were framed according to the ambivalence that participants experienced regarding their medication. An additional part of the analysis described the cultural values and goals among this group.

Piloting of Intervention

Inclusion criteria for the pilot phase were (a) any depressive disorder diagnosed by their treating clinician, (b) current antidepressant regimen, (c) Latino ethnicity, and (d) at least 18 years of age. Individuals taking antipsychotic medication or mood stabilizers were included if these medications were to treat a unipolar depressive disorder. Exclusion criteria were substance-related problems and history of mania. Psychiatrists were consulted to confirm criterion A (all were diagnosed with major depression), that medications (including non-antidepressants) were to treat a unipolar depressive disorder, and to rule out substance use/mania.

Participants were referred to the pilot phase of the study by their treating psychiatrists who explained the research and the intervention. Interested patients were contacted by phone to explain the intervention further and schedule an appointment. We provided $50 compensation for participating in this phase, which took place between January and April 2007. Ten participants were referred to receive the intervention, none of which had been involved in the previous focus groups. Two were not enrolled due to difficulty contacting and one participant was determined not to be appropriate, due to a low level of depression and being pregnant. Seven participants received the intervention, which was conducted in Spanish by the first author (AI).

A Latina MI consultant (LIR), who was not involved in administering the intervention, listened to audio recordings of the MI sessions and made clinical observations of instances that corresponded with MI techniques, as well as those that appeared problematic. She also completed a MITI (Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity) for each MI session (Moyers, Martin, Manuel, Hendrickson, & Miller, 2005). The MITI is a fidelity measure of MI techniques and was used to ensure that the intervention adhered to MI principles. It helped identify problematic aspects of the intervention and deviations from MI, which led to additional refinements to the MI approach.

Intervention Focus Group

All participants who received the pilot intervention were invited to participate in the pilot focus group. The amount of time between completing the intervention and participating in the intervention focus group (May 2007) varied, given that participants completed the intervention at different times. The longest wait between completing the intervention and participating in the group was approximately three months. Five participated in the intervention focus group and two could not be scheduled for the group because they had lengthy travels outside of the US. To facilitate open discussion, the MI counselor was not present during this focus group, which was conducted by the second author (IM). Participants received $75 for participating in this focus group. The audio-recording was also transcribed and imported into ATLAS.ti to identify the most commonly reported issues regarding the intervention.

Results

Preliminary Focus Groups

The characteristics of the preliminary focus group participants are presented in Table 1. Most participants were monolingual Spanish-speaking females from the Caribbean who had numerous years of treatment contact. What follows is a description of their experiences with antidepressants. Percentages reported reflect the proportion of participants who commented on a particular issue.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics for Preliminary Focus Groups (N = 30)

| Variable | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Female Gender | 24 | 80 |

| Mean ± SD Age | 47.0 ± 11.9 | |

| Country of Origin | ||

| Puerto Rico | 16 | 53 |

| Dominican Republic | 6 | 20 |

| Mexico | 5 | 16 |

| Other | 3 | 10 |

| Mean ± SD Years in U.S. | 17.6 ± 12.0 | |

| Education | ||

| < High School | 13 | 43 |

| Completed High School | 9 | 30 |

| Some College | 6 | 20 |

| College | 2 | 6 |

| Spanish Language Literacy | ||

| Not too well/Illiterate | 4 | 20 |

| Fairly Well | 3 | 10 |

| Very Well | 21 | 70 |

| English Language Fluency | ||

| Not too well/Can’t speak | 25 | 83 |

| Fairly Well | 4 | 13 |

| Very Well | 1 | 3 |

| Mean ± SD Years with depression diagnosis | 10.76 ± 7.3 | |

| Mean ± SD Years since first antidepressant treatment | 9.42 ± 7.9 | |

| Antipsychotic medication | 9 | 30 |

A broad range of issues were identified via the focus groups (Table 2). The numerous issues identified, many of them conflicting, illustrated the complexity of antidepressant adherence phenomena. Decisions about adherence were highly individualized due to participants’ subjective experiences. Two participants may have experienced similar difficulties with side-effects, but their evaluation of that experience differed. Also, it was commonly observed that subjective experiences differed within individuals at different points in time. These vacillations highlight the relevance of ambivalence. The following quotes are two statements by the same participant at different points in the group.

It’s that you get tired of taking medications. There are so many medications to take, there are moments that you get tired, don’t want to take medications. Also, you sometimes think that they harm your liver.

Me, what I am most afraid of is depression when it hits me. That [italics added] is what really makes me feel bad.

Table 2.

Issues Associated with Antidepressant Adherence among Preliminary Focus Group Participants (N = 30)

| Issues | Participants Commenting | |

|---|---|---|

| Motivators/Facilitators | ||

| Alliance with Providers | 26 | 87% |

| Symptoms | 25 | 83% |

| Positive Family Influence | 18 | 60% |

| Understanding Depression/Treatment | 18 | 60% |

| Positive Social Influence | 7 | 20% |

| Complications | ||

| Side-effects | 26 | 87% |

| Stigma | 22 | 73% |

| Medication Adjustment | 19 | 63% |

| Fear of Harm | 17 | 57% |

| "Many medications" | 16 | 53% |

| Lack of Efficacy | 15 | 50% |

| Forgetting doses | 14 | 47% |

| Medication Routine | 11 | 37% |

| Negative Family Influence | 9 | 30% |

| Financial Barriers | 6 | 20% |

| Not wanting "medication for life" | 4 | 13% |

| Values | ||

| Familismo | 22 | 73% |

| Work, struggle, take advantage | 19 | 63% |

| Help, share with others, lend a helping hand | 14 | 47% |

| Religion | 14 | 47% |

| Do one's part | 13 | 43% |

| Speaking Spanish | 9 | 30% |

| United | 9 | 30% |

| Cheerful | 6 | 20% |

| Affectionate | 6 | 20% |

This variation or ambivalence was commonly observed and is consistent with MI’s emphasis on ambivalence.

Motivators/facilitators for antidepressant adherence

The role of treatment providers, particularly psychiatrists, emerged as the greatest facilitator for adherence (87%). Providers were described as partners in maintaining adherence. They imparted information about depression and antidepressants. Very importantly, treatment providers helped participants overcome the various adherence complications that are reported in the section below (e.g., side-effects, lack of efficacy, medication adjustments). Working through medication adjustments is a process that required a strong treatment alliance. Confianza or trust was described as a critical ingredient of this relationship.

The second greatest motivator/facilitator for adherence was the desire to reduce depressive symptoms (83%), for which there was very little ambivalence. Instead, ambivalence centered on antidepressant treatment. Understanding depression and its treatment (60%) was another issue that helped participants overcome adherence complications. There were multiple contributions to an improved understanding, including their first learning about depression, the learning that developed from treatment experiences, and the learning that resulted from relapses. These types of learning related to participants’ prior experiences with antidepressants (including their first), as well as current experiences. In addition to learning from providers, experiencing antidepressant benefits contributed to their learning. Many described an increased recognition of how stressors exacerbated depression and how antidepressants were useful for preventing relapse. A subset of the understanding depression/treatment quotes related to learning from relapses (ya me di cuenta/ now I noticed). Participants reported learning from the relapses that followed their previous poor adherence. These descriptions were common (43%) and often contributed to insight regarding longer-term antidepressant regiments, as illustrated by the quote below.

I, for example, once had three, four days, five days without taking them to see what would happen with me. I fell into [a depression] again, so then what happens? I told the doctor, “Doctor, I have to use this for the rest of my life, forever.”

Finally, participants described positive influences from family (60%) and friends (20%) that helped with adherence. Family members often urged participants to seek treatment, in some cases even bringing them to the clinic. Family members also provided reminders to take the medication and financial assistance to purchase medications. The positive influences from friends mostly included having someone to turn to for feeling understood and for talking about their problems.

Complications of antidepressant adherence

As noted, there was considerable ambivalence surrounding issues of antidepressant adherence. Thus, while there were several motivators/facilitators, these often occurred with complications. For example, one quote indicated a positive influence by knowing a friend who benefited from antidepressants, but also a negative influence given the participant’s observation that this friend was on the medication for a long time. Below is a description of key complications to adherence that contributed to ambivalence.

A broad theme across many of the categories in Table 2 pertained to antidepressant fears. Altogether, the vast majority of participants reported some type of fear. One source of fear came from participants’ social environment (i.e., family/friends). Thirty percent reported family discouragement of medication use, such as being told that the medications were harmful, dangerous, addictive, or were like “needing a pill to function.” Another influence from the social environment pertained to stigma (73%). The perception was that antidepressants were seen by others as indicative of weakness, lack of resiliency, or severe problems. Moreover, they feared that others would see antidepressant use as similar to use of narcotics. Participants’ fears were also related to their own experiences with antidepressants. Fears were particularly notable among those who were taking multiple medication regimens (53%), due to having other medical conditions or taking multiple psychiatric medications. Other fears related to being prescribed a medication for life (13%; medicina por vida) and side-effects (87%). Also related was the fear that the medication was harmful (57%). Altogether, the combination of antidepressant cautions from their social environments, taking multiple medications, and experiencing side-effects interrelated to contribute to fear.

Limited or partial treatment responses (50%) further complicated motivation for adherence. Many participants described understandable limitations to the benefits of antidepressants. For example, one participant acknowledged the benefits of her antidepressants, but reported that, “When the [stressor] is very big, the medicine doesn’t work.”

Even when adherence was viewed as important, skills and resources were required to “work the treatment.” That is, adherence required effort and self-efficacy. Thus, some questioned their ability to endure side-effects, cope with medication fears, or withstand pressure from others to discontinue the medication. As noted above, support from providers, family, and friends aided participants’ self-efficacy for adherence. Medication adjustments required participants to “work the treatment.” Participants commonly reported (63%) medication adjustments by the psychiatrist in order to increase efficacy or tolerability. The very occurrence of these adjustments signified a difficult medication experience (e.g., side-effects, lack of efficacy). Many therefore reported uneasiness with trying a new medication, given the side-effects experienced with the previous antidepressant. In these cases, improvement was described as poco a poco (little by little), as medication adjustments were made to maximize benefit. Thus, working through medication adjustments required sustained motivation, a strong treatment alliance, and the ability to cope with medication difficulties.

Cultural values and goals

The larger social context was characterized by low socio-economic status, recent migration, and acculturative stress. This larger social reality helps contextualize a number of goals and values that emerged from the focus groups (Table 2). Consistent with immigration and goals of economic improvement, a large proportion (63%) of participants’ responses were related to a cluster of self-perceived cultural values—trabajar, luchar, y aprovechar (work, struggle, take advantage).

We can’t give ourselves the luxury of saying, “Today, I won’t go to work,” or that “the government will take care of me.” No. We have to work crying.

I say that the Latin race is proud because it is the symbol of effort and work.

These values captured a theme of striving to improve their circumstances and struggling with socioeconomic and migration stressors. Also, these values reflected both a difficult social reality (first quote above) and a source of pride (second quote above). A similar value that was frequently coded was poner de su parte (43%; do one’s part). As illustrated in the quote below, this value reflected an internal locus of responsibility in coping with problems.

Then, since that time, I started coming [to the clinic]…‥And I prayed and everything, but at the same time, like my mother used to say, “Praying, but doing.” That is, I prayed but also looked for help.

Poner de su parte reflects an internal sense of responsibility for action. In the quote above, the participant used prayer and also engaged in action-oriented coping. Poner de su parte also denotes looking outwards to cope. In other examples, participants reported looking outwards to cope by seeking out doctors appointments, exercising, utilizing social support, and engaging in pleasurable activities. It is important to note that poner de su parte, as well as other values, have the potential to serve as motivators or complications to adherence. It can be associated with an internal sense of responsibility that proscribes the need to rely on medications or that is actualized through looking outwards and seeking treatment.

These values (e.g., poner de su parte, luchar) provide culturally consonant language that can be used during counseling to tap into cultural values. They also highlight the need to align antidepressant adherence with what these values denote. In addition, they are informative on common sources of motivation among these groups (e.g., financially supporting relatives in native country, stable housing, purchasing a home, creating opportunities for their children).

Familismo (familism) emerged as the value described by the most participants (73%). This value emphasized family relationships over other social relationships, as well as over individual needs. Thus, a major cultural consideration is this group’s considerable family orientation, combined with the realities of migration and its contribution to familial disruption. The result is that family can be the source of psychosocial stressors, support, motivation, or a combination. Familismo can become a strong driving force for an individual, as taking medications can serve to help them fulfill their family role expectations. In contrast, familismo can also complicate an individual’s desire to take medication because they do not want to offend or embarrass other family members by taking antidepressants.

Additional Considerations Derived from the Focus Groups

In addition to better understanding adherence from participants’ perspectives, the focus groups informed a number of specific adaptations to the intervention. First, stigma ranked as the second most common concern pertaining to antidepressants. As a result, a menu of options for dealing with stigma was generated. These options were presented to participants dealing with stigma concerns (or social pressure to non-adhere) and included, not telling anyone about their treatment, telling only people they trust, helping others learn more about depression, or inviting someone to attend their clinical appointment. Second, the focus groups revealed health concerns about antidepressants. This resulted in an MI strategy that validated their health concern and presented information on the association between untreated depression and complicated medical outcomes. Third, we adopted a similar approach for those who were concerned about remaining on medication for life (medicina por vida). Agreement was expressed with not wanting to remain on medications for life and information was presented on the increased relapse risk associated with early discontinuation. Also, adherence was reframed as a way to successfully complete depressive treatment. Finally, religiosity has at times been associated with passivity among Latinos (Abraido-Lanza et al., 2007). However, the focus groups revealed that religious views were in fact often associated with active coping (Orando pero brazo dando/ “Praying but doing”). Religious views were therefore validated as a source of motivation, but reframed to draw out strategies for active coping.

Preliminary Motivational Interviewing Intervention

Of the seven participants who were enrolled, mostly all were female (n = 6), all were predominant Spanish-speakers, and all were foreign-born. The mean age was 40 (SD = 11.34) and nearly all (n = 6) had a high school education or less, with three having less than a seventh grade education. These participants were originally from Mexico (n = 3), Puerto Rico (n = 2), Dominican Republic (n = 1), and Columbia (n = 1). They had been in the mainland US for a mean of 16 years (SD = 11.63) and reported a mean of nine years since their first treatment with antidepressants. Prior to beginning the intervention, they produced a mean Beck Depression Inventory score of 35 (Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996). Thus, these participants presented with severe range depression scores and most had previous experience with antidepressants.

A number of considerations were applied to the preliminary intervention. The intervention retained the core components of MI (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). This included the MI spirit, which emphasized a respect for patients’ choices and concerns regarding their antidepressant. The MI spirit also involved asking the participant’s permission prior to providing antidepressant information. Also, the intervention focused on eliciting motivational statements from patients (i.e., adherence talk) and rolling with resistance. Other basic MI components included open-ended questions, affirmations, reflections, and summary statements. A minimal amount of structure was built into the intervention, given findings that highly structured MI is associated with poorer outcomes (Hettema et al., 2005). However, some general components and structure were included and standard MI techniques were used to accomplish the tasks outlined in Table 3. Also, an intervention length of two sessions was chosen for two primary reasons. First, MI has generally demonstrated rapid effects in the first few sessions and tends to maintain these effects when the MI is added to standard care (Hettema et al., 2005). Second, participants were already engaged in standard treatment and a leaner intervention was therefore chosen to minimize overall treatment burden. The first session focused on understanding participants’ depression, eliciting importance for improving symptoms, linking motivation to values and goals, and eliciting motivation specifically for taking antidepressants. The second session focused more on exploring previous adherence, exchanging antidepressant information, anticipating future reasons for discontinuation, eliciting self-efficacy for adherence, and arriving at an adherence plan. This was a very general emphasis that varied based on patient motivation and the issues that they wanted to discuss.

Table 3.

Summary of the pilot intervention’s basic components

| Components | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Rating of Adherence Importance, Confidence, & Readiness | Assessing motivation for adherence. Exploring of both sides of motivation/eliciting commitment. |

| Discussing previous adherence | Exploration of previous concerns and result of nonadherence |

| Anticipating adherence difficulties | Discuss and prepare for motivational issues that may subsequently arise |

| Personalized visual feedback from electronic medication container | Feedback on dose-taking, reinforcement of adherence, and exploration of missed doses |

| Informally assessing antidepressant knowledge | Targeted information exchange |

| Adherence Plan | Articulate patient’s reasons for adhering to treatment, anticipated barriers to adherence, and plan overcoming those barriers. Also mailed as a handwritten note along with brochure (see below). |

| Antidepressant treatment brochure* | Mailed to participants 1 week after the intervention with their permission to provide additional antidepressant information. |

| Discussing goals/values | Discussing adherence in alignment with sources of motivation |

Note. An antidepressant treatment information brochure was developed based focus group data and is available by request from the first author.

Sessions began by describing tasks to be completed during the session and asking the participant how they would like to begin (i.e., agenda setting). The tasks included a three-item adherence motivation scale (i.e., adherence importance, confidence, and readiness), scanning data from their electronic medication containers and presenting visual feedback, “talking about the medicine,” or “talking about how you’re doing.” Participants typically indicated that they were agreeable to following the therapist’s lead, which likely reflected cultural values of respeto (respect). In these situations, the response was to begin with “talking about how you’re doing” and thus begin with the least directive of tasks. The natural flow of conversation was used to lead into the other tasks. Once importance for symptom relief was established, the discussion was linked to antidepressant adherence. Often this was linked with a transition summary statement.

Therapist: Now that we’ve talked about this, I understand where you have come from and where you want to go…‥ What have you thought about the medication in terms of being able to help with this?

Adaptations Based on Pilot-Phase Observation

Observations made during the pilot phase informed a number of refinements. First, the intervention’s direct focus on antidepressants was adjusted in response to participants’ treatment expectations. The intervention initially focused on increasing motivation specifically for antidepressant adherence. However, clinical observations showed that this approach negatively affected empathy ratings (MITI), due to participants desire to discuss broader issues related to their depression. The approach was therefore adjusted to elicit motivation for an overall strategy for improving their depression, of which antidepressants represented an important part. This allowed for richer discussions about the various efforts that participants made to improve their depression and cope with stressors. This naturally led to framing antidepressant adherence as an important way of “doing one’s part.”

So, to recap, you feel the confidence, the support of your clinical team, you feel very motivated to take the medicine, but in reality the motivation is to feel better, to achieve the things we spoke about. This includes feeling better, to reach the point of being able to work, like starting to open things up for your family’s future. And also the possibility that perhaps there will be a point where [the whole family will be arriving from Guatemala] …‥ Due to all these things, it is like you are moving forward with [treatment].

This summary statement sought to frame the participant’s antidepressant adherence as one part of an overall effort to improve her depression and life situation. The quote also illustrates the importance of immigration issues (i.e., family reunification) to the context of patients’ difficulties.

A second adaptation pertained to engaging participants in the treatment process. Treatment retention rates can be low among Latino patients with depression (Miranda, Nakamura, & Bernal, 2003). Accordingly, missed appointments were common. Our approach was to actively engage participants into treatment (e.g., confirmation phone calls, multiple phone contact attempts, and appointment letters). We viewed the intervention as a process that involved their decision about treatment. The emphasis was that the decision was important and theirs to make. The outreach represented our effort to support them in their decision, even if that decision included not taking medications. We viewed these efforts as compatible with the cultural expectation of personalismo, where relationships with providers were personalized and involved trust (confianza).

A third consideration was related to the imparting of antidepressant information. Naturally, an adherence intervention encountered opportunities for providing antidepressant information and required avoiding the traps outlined by MI (e.g., giving unwanted advice, correcting). Instead, the approach relied on asking permission to provide information, providing the information, and then eliciting their reaction. However, observations revealed the potential for this approach to become repetitive and we therefore drew from other existing MI techniques to vary the approaches for imparting information. For example, another strategy involved using open-ended questions (“What have you come to understand about when antidepressants begin to help?”). These questions revealed whether participants already were informed and would instead benefit more from exploring ambivalence. Another strategy involved using reflections to reinforce antidepressant information. For example, “You mentioned wanting to take your antidepressants given how it may affect your other [medical] conditions and so it seems you understand that treating your depression is a way to take care of your overall health.”

Intervention Feasibility and Feedback Focus Group

The intervention appeared feasible given that all participants completed the two sessions of MI. Of these, one participant decided to discontinue her antidepressant. Participant feedback suggested that the most helpful components of the intervention were related to the therapeutic alliance, learning antidepressant information, and the personalized visual feedback provided by the electronic medication container. The therapeutic alliance was most commonly described with the word confianza (trust), which can be hypothesized to be related to MI’s strong emphasis on empathy. Participants also expressed a strong appreciation for the contact efforts made by phone and mail to confirm appointments, follow-up after missed appointments, and to provide answers to questions they had posed during sessions. Their feedback suggested that this approach was compatible with the value of personalismo (personalism).

As a result of their feedback, a number of additional refinements were made. First, feedback pertaining to the personalismo of outreach efforts led to the inclusion of the hand-written follow-up note (Miller, 1995). Specifically, a motivational adherence plan was hand-written and mailed to participants approximately one week after the intervention. The motivational adherence plan was a summary of their reasons for improving their depression, their efforts for getting better, their anticipated barriers for adherence, their plan for overcoming these barriers, and the values/goals that were motivating them. Furthermore, an antidepressant information brochure, developed to provide antidepressant information discussed in the focus groups, was included in this mailing. Second, MI-consistent feedback, based on the electronic medication container, was increased during the sessions based on participant feedback. The visual feedback was a calendar that depicted doses taken or missed with “1’s” or “0’s,” respectively. Discussion was generated by asking participants about their reaction to viewing the visual feedback.

Case Example

Minerva was a 40-year-old, Spanish-speaking Puerto Rican female who began treatment with her psychiatrist for “anxiety and depression” one year prior to being referred for MI. She was referred for MI given her discontinuation of two SSRI antidepressants during the last year, often only after a week or two. Her discontinuations were due to her inability to tolerate the side effects. After attempting two SSRI’s, she was prescribed quetiapine, given its relatively tolerable side-effect profile and its off-label use for anxiety. The prescription was made one month prior to the intervention, but Minerva reported that she only commenced taking the medication during the week she was scheduled for MI. She attributed her symptoms to a series of psychosocial stressors that occurred during a brief period of time. During our first session, it was readily apparent that antidepressant adherence was important to Minerva. Her primary motivators for treating her symptoms included being able to increase the quality of her family functioning, to be the person “I used to be,” and return to work. It was Minerva’s confidence that interfered with her motivation. Her lower confidence was almost solely related to her fear of the medications.

Empathy

A crucial ingredient of the intervention was to reflect empathy regarding her symptoms, her motivation to improve, and her difficult experiences with psychotropics (e.g., side-effects, reading about rare adverse events). Reflections increasingly began to focus on ambivalence. At times, she would make statements such as, “I prefer a thousand times having these side-effects than the anxiety, I swear.” During other times, the side-effects diminished her motivation for adhering.

Patient: I don’t want to keep taking it like this. There has to be another medication. If I am going to keep having these side-effects, then I don’t want to keep on taking it. But, if they will go away, I will keep taking it.

Therapist: It is very common for there to be a complicated situation where one feels mixed. One the one hand, you can say, “Well, you know what, the medication is helping me and there are so many important things in my life that I believe that, even with these side-effects, I am feeling a bit better.” But sometimes you start to think about the side-effects and say “Ah, maybe I won’t continue with the medicine.”

Patient: It’s true. The thoughts are contradictions.

Increasingly, her motivational utterances were the ones that were reflected. This included statements that the symptom relief was worth the side-effects and that her fears were likely a product of anxiety. By reflecting these statements and eliciting elaboration, Minerva increasingly engaged in adherence talk.

Working with goals and values

The focus groups provided information on a range of goals and values. And although different participants were motivated by different sets of these goals and values, the ones they reported often corresponded with the information derived from the focus groups. Examples of the goals and values reported by different participants who received the MI included, becoming more spiritual, being more resilient to psychosocial stressors (luchar), and family reunification after immigration (see quote on page 19). In Minerva’s case, open-ended questions pertaining to goals and values targeted her motivation for adherence. For Minerva, her family was quite important, as well as her goals of returning to work and taking more time for herself to enjoy life. She was concerned with how her symptoms impeded her functioning and progress towards her goals. Discussions that linked her goals and values to her antidepressant treatment sought to draw from her sources of motivation to help her argue for adherence. The following took place immediately after Minerva discussed her goals and values.

Therapist: Clearly, you recognize that there are difficulties related to the depression, the anxiety. You have many important reasons, very emotional ones, for feeling better. And for these reasons, I see that you are putting forth a tremendous effort in finding the medication that is going to help you. But, it is these side-effects that complicate this for you that make you feel afraid of the medication.

Patient: Yes. I know that it has a lot of side-effects …‥But what I want is to heal. I want to be better. I no longer want to be [depressed and anxious].

Therapist: Ok. The important thing for you is your family, your children, being able to work, and being able to think about yourself.

Patient: Yes.

The counseling approach also worked with religious values. The focus groups revealed that the religious value of trusting in God can be intertwined with active coping (poniendo de su parte). Therefore, the MI approach emphasized working within the framework of participants’ religious faith, while deliberately highlighting active coping dimensions. For example, Minerva described exercising to cope with anxiety. This emphasis on active coping is consistent with MI’s emphasis on self-efficacy, which helps patients articulate their own capacity for change. The quote below illustrates an effort to work within Minerva’s religious faith, while simultaneously enhancing her self-efficacy by selectively highlighting her active efforts at coping.

Patient: Yeah, I left it to God because if I get thinking about the side-effects, then I won’t be able to take the medicine. It’s better to leave it to God and I expect that God won’t let me have a bad reaction to the medication.

Counselor: It also looks like you’ve decided on a bit more. Not only have you decided to put these things in the hands of God. You have also decided, “Well, I will do my part and do everything I can to get better and what is outside my control, then that’s where I’ll leave it to God.”

Patient: Yes, that’s how I am thinking now.

In the quote above, the therapist invoked the value of poner de su parte through the use of the phrase, “do my part and do everything I can.” In addition, rather than evoking resistance by challenging the passivity implied in the Minerva’s first statement, the therapist used the MI technique of “agreement with a twist” by allying with the patient’s religious faith while also highlighting her active coping strategies.

Imparting information

In Minerva’s case, three key pieces of information were imparted: 1) the temporary nature of many side-effects; 2) the possibility that some physical symptoms may be more related to anxiety; and 3) the distinction between rare and common side-effects. Minerva demonstrated some awareness of the relationship between anxiety and physical symptoms and a reflection was used to evoke further discussion of this issue: “Therapist: And in speaking with you, it seems that you recognize that anxiety can cause physical symptoms and sometimes it’s hard to know if the symptoms are due to anxiety or the medication.” Reflecting this struggle elicited more discussion from her on instances where she contemplated the role of anxiety in contributing to her physical symptoms. Eventually, this opened the discussion regarding the physical effects of anxiety and motivated her to learn more about this issue.

Supporting self-efficacy

As described by Miller and Rollnick (2002), the approach focused on eliciting Minerva’s self-efficacious statements, in contrast to convincing her of her efficacy. The strategy for eliciting self-efficacy included a combination of open-ended questions and reflections to invite elaboration.

Therapist: But now you’re mentioning that there have been occasions that you’ve overcome the worries about the medication in the sense of saying, “No, this is related to anxiety.” And it’s like you have a worry and you start to overcome it.

Patient: Yes, because if I don’t, I’ll stop the medication. That is, the anxiety is really bad, but I say, “This is from my anxiety,” and there I begin to calm down, I start breathing and there I calm down.

Therapist: And how has that been for you? That strategy.

Patient: Well, it has been good because then I don’t go to the emergency room. Previously, I would go to the emergency room all the time. I used to feel a lot of anxiety and now I don’t.

Therapist: Well, it seems that you have been doing many things to try to get past this. You’ve mentioned jogging outside, trying to be more active, and now you are trying to get your worries and…‥

Patient: …‥control them.

Therapist: And control them.

Patient: Control the worries. Yes.

Outcome

Minerva’s baseline appointment was conducted one week before the intervention and the post-treatment appointment was conducted 2 weeks after the intervention. Upon completing the intervention, Minerva decided that the medication was sufficiently beneficial and that she would remain adherent. Her level of adherence, measured using an electronic medication container, showed that she was highly adherent, missing only two doses during a one-month period. A few weeks after the intervention, Minerva was switched back to an SSRI antidepressant. A reading of her medication container (with SSRI medication) was taken a month later and showed only one missed dose.

Discussion

The current paper described the adaptation of an MI intervention to improve antidepressant adherence among Latinos. In doing so, we were able to describe the antidepressant experiences of this Latino group. There was a great deal of overlap between the antidepressant issues described in this data and those that have been described among non-Latinos. For example, focus group data support the cross-cultural relevance of medication issues such as side-effects, stigma, medication attitudes, therapeutic alliance, and actual/perceived efficacy (Keller et al., 2002; Sirey, Bruce, Alexopoulos, Perlick, Friedman et al., 2001). The role of treatment alliance emerged during the preliminary and feedback focus groups as particularly important among this group of participants, which is consistent with previous research with Latinos (Bernal, Bonilla, Padilla-Coto, & Perez-Prado, 1998). This finding supports the use of a patient-centered approach such as MI.

The current data informed the MI approach in a number of ways. First, the qualitative analysis allowed for a rich understanding of this group’s antidepressant experiences and the nuances of relevant issues. Second, the qualitative data allowed us to understand the social context of antidepressant use (i.e., family/social influence, stigma). Third, since language is a carrier of culture, it was important to move beyond simply conducting MI in Spanish. For this reason, participants’ phraseology (e.g., medicina por vida; luchar) for specific experiences was used to capture motivating values. This information allowed for improved communication of empathy, which is a critical MI ingredient.

It is important to note that, despite these adaptations, the intervention remained grounded in MI principles. Thus, instead of incorporating changes that altered the core principles of the intervention, the development phases served to inform the MI. The result was the use of MI techniques that were contextualized by the issues, attitudes, behaviors, preferences, and social environment of this group and this particular clinical issue. In addition, the development process helped select among specific MI techniques that were included. Examples include refining techniques for imparting antidepressant information, developing a menu of options for overcoming adherence barriers (e.g., stigma,), and personalized visual feedback on their dose-taking. A key adaptation was to reframe antidepressant adherence as a way to luchar or poner de su parte, so that antidepressant adherence was aligned with cultural values.

The current phase of the intervention development process relied heavily on qualitative methods and thereby generated data directly from participants’ experiences (Bernal & Scharron-del-Rio, 2001). This was particularly beneficial given our need to understand the perspectives of an understudied minority group. As part of this treatment development phase, the intervention was also piloted with seven participants. The purpose was not to generate preliminary efficacy data, but to fine-tune the intervention via clinical observation and focus group feedback. As part of a research program that combines qualitative methods with quantitative ones, the next step in the research is to examine the efficacy of this intervention via randomized trial (Rounsaville, Carroll, & Onken, 2001). Thus, the clinical approach described herein is limited in that its efficacy is currently being evaluated. However, it relied upon an empirically-supported counseling approach, which has been efficacious for addressing adherence, and an intensive development process for ensuring cultural relevance (Bernal & Scharron-del-Rio, 2001; Napoles-Springer & Stewart, 2006; Zweben & Zuckoff, 2002).

A cautionary note pertains to the risk of essentializing cultures, which is often inherent in discussions of cultural-competency. The result can be inappropriately ascribing attributes to individuals based on culture (i.e., stereotyping). What our data provide are common experiences among our sample of mostly lower-income, Spanish-speaking females. The literature suggests a number of dimensions that are likely to affect the applicability of cultural knowledge. A valuable suggestion for working with cultural minorities is to utilize a clinical hypothesis testing approach, which allows one to hypothesize based on cultural knowledge and to apply this knowledge when appropriate and indicated (Sue, 1998).

There are additional limitations worth noting. A first limitation is that there was difficulty enrolling a significant number of participants. It is important to note that these rates are similar to that seen in other research. However, the current rates are notable given that this research essentially focuses on engagement into care. This observation is informative in that future designs should focus on recruitment methods that are associated with better enrollment rates. Despite this limitation, if it is found, in the randomized trial currently underway, that those who are recruited and receive the intervention demonstrate improved adherence relative to controls, then this would remain very valuable finding. A second drawback to the current paper pertains to the limited quantitative data. However, research strategies for developing empirically-supported treatments for racial/ethnic minorities have called for the use of qualitative methods to systematically generate the information necessary to culturally adapt treatments. In addition, the strategy also calls for quantitative methods that confirm the hypotheses generated from qualitative approaches. Accordingly, the current manuscript represents the qualitative phase of the research, while a randomized controlled trial is currently underway.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (K23 MH074860). The work has also been supported by an unrestricted medical education grant from Forrest Laboratories, Inc. The authors also want to acknowledge institutional support from University Behavioral Healthcare.

Appendix

Focus Group Moderator Guide

¿Cual es su nombre? ¿De donde es? ¿Cuantos años tiene en los Estados Unidos? [What is your name? Where are you from? How many years do you have in the United Status?]

Vamos a enfocar la conversación en lo que es ser una persona Hispana o Latina. ¿Para ustedes, cuales son las cosas más importantes de ser una persona Hispana o Latina? [Let us focus the conversation on what is it to be Hispanic or Latina. For you, what are the most important things of being Hispanic or Latina?]

Piensen por un momento en personas que han conocido que han tomado la medicina antidepresiva. ¿𝑸ue habían oído sobre las experiencias de esas personas? [Think for a moment about people you have known that have taken antidepressant medicine. What have you heard about the experiences of those people?]

¿Ustedes piensan que es diferente para los Hispanos tomar la medicina antidepresiva? ¿De que forma? [Do you think that it is different for Hispanics to take antidepressant medicine?]

Piense en la primera vez que su doctor le sugirió tomar medicina para la depresión. ¿𝑸ue pensó en ese momento? [Think about the first time your doctor suggested that you take medicine for your depression. What did you think at that moment?]

¿𝑸ue fue lo que le motivó para tratar la medicina antidepresiva? [What motivated you to try antidepressant medicine?]

Piense en ocasiones cuando usted no quiso tomar su medicina. ¿Por cuales razones no quiso tomar la medicina antidepresiva? [Think about occasions when you did not want to take your medicine. For what reasons did you not want to take the antidepressant medicine?]

Piense en ocasiones cuando usted no tomó su medicina, aunque usted quería tomarla. ¿Cuales son las complicaciones que no la dejo tomarla? [Think about occasions when you did not take your medicine, although you wanted to take it. What were the complications that did not allow you to take it?]

Muchas veces uno tiene que decirle cosas importantes sobre la medicina al psiquiatra. 𝑸uizás uno tiene que decirle que la medicina no esta ayudando o que le esta causado efectos secundarios. ¿Como se sienten ustedes cuando hablan con su doctor sobre estas cosas? [Many times one has to tell the psychiatrist important things about the medicine. Perhaps one has to tell him that the medicine is not helping or that it is causing side-effects. How do you fell when you talk to your doctor about these things?]

¿En que forma le a ayudado la familia en tomar sus medicinas? [In what way has your family helped you in taking your medicine?]

¿Cuales son cosas que su familia a hecho que NO le han ayudado con las medicinas? [What are some things that you family has done that did not help you with the medicines?]

Contributor Information

Alejandro Interian, UMDNJ—Robert Wood Johnson Medical School

Igda Martinez, Rutgers—The State University of New Jersey

Lisbeth Iglesias Rios, University of New Mexico

Jonathan Krejci, Princeton House Behavioral Healthcare

Peter J. Guarnaccia, Rutgers—The State University of New Jersey

References

- Abraido-Lanza AE, Viladrich A, Florez KR, Cespedes A, Aguirre AN, De La Cruz AA. Commentary: fatalismo reconsidered: a cautionary note for health-related research and practice with Latino populations. Ethnicity & Disease. 2007;17:153–158. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backer TE. Finding the balance-program fidelity and adaptation in substance abuse prevention: A state-of-the-art review. Rockville, MD: Center for Substance Abuse Prevention; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal G, Bonilla J, Padilla-Cotto L, Perez-Prado EM. Factors associated to outcome in psychotherapy: an effectiveness study in Puerto Rico. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1998;54:329–342. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(199804)54:3<329::aid-jclp4>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal G, Scharron-del-Rio MR. Are empirically supported treatments valid for ethnic minorities? Toward an alternative approach for treatment research. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2001;7:328–342. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.7.4.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Barrera M, Jr, Martinez CR., Jr The Cultural Adaptation of Prevention Interventions: Resolving Tensions Between Fidelity and Fit. Prevention Science. 2004;5:41–45. doi: 10.1023/b:prev.0000013980.12412.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demyttenaere K, Van Ganse E, Gregoire J, Gaens E, Mesters P. Compliance in depressed patients treated with fluoxetine or amitriptyline. Belgian Compliance Study Group. International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1998;13:11–17. doi: 10.1097/00004850-199801000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health & Human Services. Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity-A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville: MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettema J, Steele J, Miller WR. Motivational Interviewing. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:91–111. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Interian A, Diaz-Martinez AM. Considerations for conducting culturally competent Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy with Latino patients. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2007;14:87–97. [Google Scholar]

- Keller MB, Hirschfeld RMA, Demyttenaere K, Baldwin DS. Optimizing outcomes in depression: Focus on antidepressant compliance. International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2002;17:265–271. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200211000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289:3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau AS. Making the case for selective and directed cultural adaptations of evidence-based treatments: Examples from parent training. Clinical Psychology: Science & Practice. 2006;13:295–310. [Google Scholar]

- Marcos LR, Cancro R. Pharmacotherapy of Hispanic depressed patients: clinical observations. American Journal of Psychotherapy. 1982;36:505–512. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.1982.36.4.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melfi CA, Chawla AJ, Croghan TW, Hanna MP, Kennedy S, Sredl K. The effects of adherence to antidepressant treatment guidelines on relapse and recurrence of depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:1128–1132. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.12.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR. Motivational Enhancement therapy with drug abusers. 1995 Retrieved April 16, 2008 from http://www.motivationalinterview.org/clinical/METDrugAbuse.PDF.

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing. New York: Guilford; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J, Nakamura R, Bernal G. Including ethnic minorities in mental health intervention research: a practical approach to a long-standing problem. Culture, Medicine & Psychiatry. 2003;27:467–486. doi: 10.1023/b:medi.0000005484.26741.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Martin T, Manuel JK, Hendrickson SM, Miller WR. Assessing competence in the use of motivational interviewing. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;28:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CJL, Lopez AD. Evidence-based health policy: lessons from the Global Burden of Disease Study. Science. 1996;274:740–743. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napoles-Springer AM, Stewart AL. Overview of qualitative methods in research with diverse populations. Making research reflect the population. Medical Care. 2006;44:S5–S9. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000245252.14302.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Mental Health. Breaking ground, breaking through: The strategic plan for mood disorders research. Washington, DC: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Marcus SC, Tedeschi M, Wan GJ. Continuity of antidepressant treatment for adults with depression in the United States. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:101–108. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez RR, de la Cruz GP. In: The Hispanic Population in the United States. Bureau UC, editor. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rogler LH, Malgady RG, Costantino G, Blumenthal R. What do culturally sensitive mental health services mean? The case of Hispanics. American Psychologist. 1987;42:565–570. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.42.6.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rounsaville BJ, Carroll KM, Onken LS. A stage model of behavioral therapies research: Getting started and moving on from stage I. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2001;8:133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Lacay JA, Lewis-Fernandez R, Goetz D, Blanco C, Salman E, Davies S, et al. Open trial of nefazodone among Hispanics with major depression: efficacy, tolerability, and adherence issues. Depression & Anxiety. 2001;13:118–124. doi: 10.1002/da.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirey JA, Bruce ML, Alexopoulos GS, Perlick DA, Friedman SJ, Meyers BS. Stigma as a barrier to recovery: Perceived stigma and patient-rated severity of illness as predictors of antidepressant drug adherence. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:1615–1620. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleath B, Rubin RH, Huston SA. Hispanic ethnicity, physician-patient communication, and antidepressant adherence. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2003;44:198–204. doi: 10.1016/S0010-440X(03)00007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Sue S. In search of cultural competence in psychotherapy and counseling. American Psychologist. 1998;53:440–448. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.4.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Karno M, Alegria M, Alvidrez J, Bernal G, Escamilla M, et al. Research Issues for Improving Treatment of U.S. Hispanics with Persistent Mental Disorders. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58:385–394. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.3.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Kolody B, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alderete E, Catalano R, Caraveo-Anduaga J. Lifetime prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders among urban and rural Mexican Americans in California. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:771–778. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.9.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweben A, Zuckoff A. Motivational Interviewing and treatment adherence. In: Miller WR, Rollnick S, editors. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing people for change. Second Edition. New York: Guilford; 2002. pp. 299–319. [Google Scholar]