Abstract

Sperm competition typically favours an increased investment in testes, because larger testes can produce more sperm to provide a numerical advantage in competition with rival ejaculates. However, interspecific variation in testis size cannot be equated directly with variation in sperm production rate—which is the trait ultimately selected under sperm competition—because there are also differences between species in the proportion of spermatogenic tissue contained within the testis and in the time it takes to produce each sperm. Focusing on the latter source of variation, we provide phylogenetically controlled evidence for mammals that species with relatively large testes (and hence a high level of sperm competition) have a shorter duration of the cycle of the seminiferous epithelium and consequently a faster rate of spermatogenesis, enabling males to produce more sperm per unit testis per unit time. Moreover, we identify an independent negative relationship between sperm length and the rate of spermatogenesis, such that spermatogenesis takes longer in species with longer sperm. We conclude that sperm competition selects for both larger testes and a faster rate of spermatogenesis to increase overall sperm production, and that an evolutionary trade-off between sperm size and numbers may be mediated via constraints on the rate of spermatogenesis imposed by selection for longer sperm.

Keywords: mammals, seminiferous epithelium, sperm competition, sperm morphology, sperm production rate, spermatogenesis

1. Introduction

There is widespread evidence that relative testis size evolves in response to the selective pressure of sperm competition (e.g. Harcourt et al. 1981), which occurs when ejaculates from rival males compete over fertilization (Parker 1970). Increases in relative testis size are assumed to reflect increased investment in sperm production, since there is evidence for a correlation between testis size and the number of sperm produced per unit time (e.g. Amann 1970; Møller 1989). However, this assumption potentially masks important additional sources of variation in sperm production rate. First, the proportion of spermatogenic tissue contained within the testis can vary widely from one species to another (Lüpold et al. 2009). Second, while the basic process of spermatogenesis is evolutionarily highly conserved, there is wide interspecific variation in the time it takes for each individual spermatozoon to be produced (Roosen-Runge 1977). Because overall sperm production rate (rather than testis size per se) will usually be the ultimate target of selection, the evolutionary forces shaping these additional sources of variation should also be considered, particularly in the context of sperm competition (Schärer et al. 2008; Lüpold et al. 2009).

In mammals, the time it takes for each spermatozoon to be produced is determined by the duration of the cycle of the seminiferous epithelium (Clermont 1972), which can be defined as the time taken for one complete series of typical cell associations that occur in the seminiferous epithelium during spermatogenesis (Clermont 1972). Approximately four and a half of these cycles occur over the period required to produce each spermatozoon, but, because the exact start and endpoints of spermatogenesis are difficult to define, its total duration is usually extrapolated from seminiferous epithelium cycle length (SECL) (Clermont 1972; Johnson 1995). SECL varies widely between species, and it has generally been assumed that this variation is independent of testis size (e.g. Johnson 1995). However, Peirce & Breed (2001) found evidence that two Australian rodents differing in sperm competition level differ markedly in SECL, and Parapanov et al. (2008) have reported a negative correlation between relative testis size (and thus the predicted sperm competition level) and SECL in six shrew species. Here, we aim to explore the generality of these findings by testing whether sperm competition selects for a faster rate of spermatogenesis across a broad range of mammalian taxa.

Variation in sperm size could also affect the rate of spermatogenesis. Sperm size and morphology is highly variable in the animal kingdom (see a review in Pitnick et al. 2009), including in mammals (Gage 1998). The selective forces responsible for shaping sperm size evolution continue to be debated (see §4), but it seems likely that sperm of differing sizes will place different demands on the machinery of spermatogenesis (Schärer et al. 2008; Lüpold et al. 2009) and involve different time or resource costs (Pitnick et al. 1995; Pitnick 1996; LaMunyon & Ward 2002; Joly et al. 2008). If larger sperm take longer to produce, this may form the basis of an evolutionary trade-off between sperm size and numbers, with important theoretical implications for understanding the evolution of sperm competition phenotypes (see Pitnick 1996). Hence, for a broad range of mammalian taxa, we also investigate the relationship between sperm length and SECL.

2. Material and methods

To quantify interspecific variation in the duration of mammalian spermatogenesis, we collated data from the literature on SECL. In total, we obtained measures of SECL in 50 species across nine mammalian orders for which we were also able to obtain data on body mass as well as either testis mass or sperm length (or both). Body and testes masses were extracted from the same source as for SECL wherever possible, or else from previous comparative analyses (see appendix S1, electronic supplementary material). All sperm length data were extracted from Gage (1998). All four variables were log-transformed prior to analysis.

We used the phylogenetic general linear model (PGLM) procedure to estimate and then control for phylogenetic effects (see Freckleton et al. 2002; Gage & Freckleton 2003). Phylogenies were constructed using the supertree of Bininda-Emonds et al. (2007). Analyses were conducted in R (v. 2.4.0), using APE to generate variance–covariance matrices (Paradis et al. 2004) and unpublished code supplied by R. Freckleton to fit the PGLMs. Body mass was included in all models as a covariate, such that significant effects of testis mass (controlling for body mass) were interpreted as evidence for an effect of sperm competition (Gage & Freckleton 2003). The evolution of relative testis size in response to sperm competition level is well established in mammals (e.g. Harcourt et al. 1981; Ramm et al. 2005).

3. Results

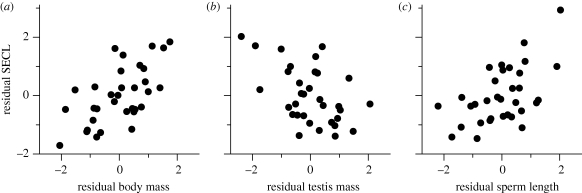

When all three predictors are investigated together, analyses with and without control for phylogeny reveal the same pattern: body mass and sperm length each exert a significant positive effect on SECL, whereas testis mass exerts a significant negative effect (table 1; figure 1). This suggests that larger species and species with longer sperm take longer to manufacture sperm, but sperm competition (as reflected by relatively larger testes) selects for a shortened duration of spermatogenesis.

Table 1.

Analysis of seminiferous epithelium cycle length variation in mammals with respect to body mass, testis mass and sperm length. (Note that the PGLM analysis was conducted with the index of phylogenetic dependence, λ, fixed at zero and set at its maximum-likelihood estimate; both models are presented because this did not differ significantly from zero (p = 0.32).)

| term | estimate ± s.e. | t | p-value | r2adj |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 33, λ = 0 | ||||

| intercept | −0.57 ± 0.68 | −0.84 | n.s. | 0.40 |

| body mass | 0.17 ± 0.04 | 4.16 | <0.001 | |

| testis mass | −0.14 ± 0.05 | −3.00 | <0.006 | |

| sperm length | 0.45 ± 0.12 | 3.80 | <0.001 | |

| n = 33, λ = 0.44 | ||||

| intercept | −0.13 ± 0.68 | −0.20 | n.s. | 0.30 |

| body mass | 0.14 ± 0.04 | 3.32 | <0.003 | |

| testis mass | −0.11 ± 0.05 | −2.47 | <0.02 | |

| sperm length | 0.41 ± 0.12 | 3.48 | <0.002 | |

Figure 1.

Partial regression plots to illustrate the effects of (a) body mass, (b) testis mass, and (c) sperm length on SECL in mammals. In each panel, the x-axis represents standardized residuals from an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression of the focal predictor variable against the other two predictor variables, and the y-axis represents standardized residuals from an OLS regression of SECL against the other two predictor variables. For statistics from phylogenetically controlled analyses, see table 1.

Because data on SECL and at least two of the predictor variables were available for several additional species, we also conducted separate analyses of the sperm length and testis mass effects (in each case controlling for body mass). The sperm length analysis confirmed the pattern identified in the combined analysis (n = 35, λ = 0.84, sperm length effect: 0.38 ± 0.13, t = 2.92, p < 0.007), whereas the testis mass analysis did not (n = 48, λ = 0.59, testis mass effect: −0.04 ± 0.04, t = −1.00, p = 0.3). Hence, it appears that sperm length and sperm competition exert independent and opposing effects on the duration of spermatogenesis in mammals, but that a negative relationship with relative testis mass is only revealed after controlling for a positive relationship with sperm length.

4. Discussion

Our comparative analysis suggests that sperm competition selects for a faster rate of spermatogenesis in mammals. This presumably enables males to replenish sperm reserves more quickly, and thus maintain higher mating rates or larger ejaculate sizes. Hence, while testis size is a useful predictor of sperm production rate (Amann 1970; Møller 1989), there is also increasing evidence both from comparative analyses (Schärer et al. 2008; Lüpold et al. 2009; this study) and experimental studies of sperm production plasticity (Oppliger et al. 1998; Bjork et al. 2007; Schärer & Vizoso 2007; Ramm & Stockley 2009), that factors within the testis contributing to variation in sperm production rate should also be considered in the context of male adaptations to sperm competition.

Second, mammalian species with longer sperm have a longer SECL. It seems intuitively appealing that longer sperm will take longer to manufacture (Lüpold et al. 2009); for example, there is evidence that the rate of spermatogenesis tracks strain- and species-specific variation in sperm size in nematodes (see LaMunyon & Ward (2002) and references therein). More generally, evidence for the substantial costs of spermatogenesis resulting from sperm size evolution comes from Drosophila, in which increasing sperm length delays male reproductive maturity (Pitnick et al. 1995), increases resources required for sperm production and packaging (Pitnick 1996; Joly et al. 2008) and selects for prudent male sperm-production strategies (Bjork et al. 2007). Further work is needed to explore how selection on sperm numbers and sperm length combines to affect the evolution of testicular architecture (Schärer et al. 2008; Lüpold et al. 2009), and how the various features of the testis investigated to date are functionally integrated.

Interpreting our two main results is potentially complicated by the evolutionary relationship between sperm competition and sperm length in mammals. If relative testis mass accurately reflects sperm competition level, and if sperm competition and sperm length are generally positively correlated (Gomendio & Roldan 1991)—although they were not in our dataset—then their opposing effects on the speed of spermatogenesis might normally be expected to cancel one another out. Positive relationships between sperm competition and sperm size are indeed supported in a wide variety of taxa (see Pitnick et al. 2009), but current evidence in mammals, at least for overall sperm size, suggest that this is unlikely to be an issue (e.g. Gage & Freckleton 2003; Anderson et al. 2005). Given their independent and opposing effects on SECL, our results confirm a further physiological basis for evolutionary trade-offs between sperm size and number, as suggested by Pitnick (1996).

Acknowledgements

We thank R. Freckleton for supplying R code to conduct the analysis, J. F. Lemaître for useful discussions, two anonymous referees for their useful comments and the Leverhulme Trust for funding.

References

- Amann R. P.1970Sperm production rates. In The testis, vol. 1 (eds Johnson A. D., Gomes W. R., Vandemark N. L.), pp. 433–482 New York, NY: Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M. J., Nyholt J., Dixson A. F.2005Sperm competition and the evolution of sperm midpiece volume in mammals. J. Zool. 267, 135–142 (doi:10.1017/S0952836905007284) [Google Scholar]

- Bininda-Emonds O. R. P., et al. 2007The delayed rise of present-day mammals. Nature 446, 507–512 (doi:10.1038/nature05634) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjork A., Dallai R., Pitnick S.2007Adaptive modulation of sperm production rate in Drosophila bifurca, a species with giant sperm. Biol. Lett. 3, 517–519 (doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0219) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clermont Y.1972Kinetics of spermatogenesis in mammals: seminiferous epithelium cycle and spermatogonial renewal. Physiol. Rev. 52, 198–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freckleton R. P., Harvey P. H., Pagel M.2002Phylogenetic analysis and comparative data: a test and review of evidence. Am. Nat. 160, 712–726 (doi:10.1086/343873) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage M. J. G.1998Mammalian sperm morphometry. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 265, 97–103 (doi:10.1098/rspb.1998.0269) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage M. J. G., Freckleton R. P.2003Relative testis size and sperm morphometry across mammals: no evidence for an association between sperm competition and sperm length. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 270, 625–632 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.2258) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomendio M., Roldan E. R. S.1991Sperm competition influences sperm size in mammals. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 243, 181–185 (doi:10.1098/rspb.1991.0029) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harcourt A. H., Harvey P. H., Larson S. G., Short R. V.1981Testes weight, body weight, and breeding system in primates. Nature 293, 55–57 (doi:10.1038/293055a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson L.1995Efficiency of spermatogenesis. Microsc. Res. Tech. 32, 385–422 (doi:10.1002/jemt.1070320504) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joly D., Luck N., Dejonghe B.2008Adaptation to long sperm in Drosophila: correlated development of the sperm roller and sperm packaging. J. Exp. Zool. (Mol. Dev. Evol.) 310B, 167–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaMunyon C. W., Ward S.2002Evolution of larger sperm in response to experimentally increased sperm competition in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 269, 1125–1128 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.1996) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüpold S., Linz G. M., Rivers J. W., Westneat D. F., Birkhead T. R.2009Sperm competition selects beyond relative testes size in birds. Evolution 63, 391–402 (doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00571.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Møller A. P.1989Ejaculate quality, testes size and sperm production in mammals. Funct. Ecol. 3, 91–96 (doi:10.2307/2389679) [Google Scholar]

- Oppliger A., Hosken D. J., Ribi G.1998Snail sperm production characteristics vary with sperm competition risk. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 265, 1527–1534 (doi:10.1098/rspb.1998.0468) [Google Scholar]

- Paradis E., Claude J., Strimmer K.2004APE: analyses of phylogenetics and evolution in R language. Bioinformatics 20, 289–290 (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btg412) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parapanov R., Nussle S., Hausser J., Vogel P.2008Relationships of basal metabolic rate, relative testis size and cycle length of spermatogenesis in shrews (Mammalia, Soricidae). Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 20, 431–439 (doi:10.1071/RD07207) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker G. A.1970Sperm competition and its evolutionary consequences in the insects. Biol. Rev. 45, 525–567 (doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1970.tb01176.x) [Google Scholar]

- Peirce E. J., Breed W. G.2001A comparative study of sperm production in two species of Australian arid zone rodents (Pseudomys australis, Notomys alexis) with marked differences in testis size. Reproduction 121, 239–247 (doi:10.1530/rep.0.1210239) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitnick S.1996Investment in testes and the cost of making long sperm in Drosophila. Am. Nat. 148, 57–80 (doi:10.1086/285911) [Google Scholar]

- Pitnick S., Markow T. A., Spicer G. S.1995Delayed male maturity is a cost of producing large sperm in Drosophila. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci.USA 92, 10 614–10 618 (doi:10.1073/pnas.92.23.10614) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitnick S., Hosken D. J., Birkhead T. R.2009Sperm morphological diversity. In Sperm biology: an evolutionary perspective (eds Birkhead T. R., Hosken D. J., Pitnick S.), pp. 69–149 Burlington, MA: Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- Ramm S. A., Stockley P.2009Adaptive plasticity of mammalian sperm production in response to social experience. Proc. R. Soc. B 276, 745–751 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.1296) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramm S. A., Parker G. A., Stockley P.2005Sperm competition and the evolution of male reproductive anatomy in rodents. Proc. R. Soc. B 272, 949–955 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.3048) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roosen-Runge E. C.1977The process of spermatogenesis in animals Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- Schärer L., Vizoso D. B.2007Phenotypic plasticity in sperm production rate: there's more to it than testis size. Evol. Ecol. 21, 295–306 (doi:10.1007/s10682-006-9101-4) [Google Scholar]

- Schärer L., Da Lage J. L., Joly D.2008Evolution of testicular architecture in the Drosophilidae: a role for sperm length. BMC Evol. Biol. 8, 143 (doi:10.1186/1471-2148-8-143) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]