Abstract

Poverty is now at the heart of development discourse; we discuss how it is measured and understood. We next consider the negative and positive impacts of livestock on pro-poor development. Taking a value-chain approach that includes keepers, users and eaters of livestock, we identify diseases that are road blocks on the ‘three livestock pathways out of poverty’. We discuss livestock impacts on poverty reduction and review attempts to prioritize the livestock diseases relevant to the poor. We make suggestions for metrics that better measure disease impact and show the benefits of more rigorous evaluation before reviewing recent attempts to measure the importance of disease to the poor. High impact of a disease does not guarantee high benefits from its control; other factors must be taken into consideration, including technical feasibility and political desirability. We conclude by considering how we might better understand and exploit the roles of livestock and improved animal health by posing three speculative questions on the impact of livestock diseases and their control on global poverty: how can understanding livestock and poverty links help disease control?; if global poverty reduction was the aim of livestock disease control, how would it differ from the current model?; and how much of the impact of livestock disease on poverty is due to disease control policy rather than disease itself?

Keywords: livestock, global poverty, poverty reduction, disease impact

1. Introduction

We start with an overview of global poverty and of the connections between poverty and livestock. We go on to explore impacts of livestock disease control on poverty using the ‘livestock pathways out of poverty’ framework and discuss its merits and inherent limitations as a producer-focused framework. Moving from frameworks to metrics, we review the different attempts to prioritize livestock diseases from a poverty perspective, illustrating the difficulties in measuring the impact of livestock disease, let alone disease control, on poverty. The importance of a disease to the poor is not sufficient justification for control and in the next section we discuss other factors that determine whether disease control can have impacts on global poverty, in particular considering feasibility and desirability of control. The final section reviews some of the more exciting examples of recent shifts towards ‘pro-poor’ disease control before leaving the reader with some questions and some general conclusions.

2. Livestock: a pathway out of poverty for some, an expression of poverty for most

Over the last decade, there has been a progressive and substantial change in approach to the challenges associated with development; these can probably be best summarized by the now obligatory insertion of ‘pro-poor’ and ‘sustainable’ before the long-standing goal of ‘economic growth’. Whether this change is a prerequisite to ‘making poverty history’ or an additional hurdle for equitable global development is probably too early to evaluate, but nevertheless the change in approach is both engaging and persuasive. Instead of a focus on agricultural commodities (such as crops, livestock, trees) and on improving their productivity, the focus has now swung to the people. Poverty reduction is the name of the game. But what does it mean?

Driven by the United Nations Millennium Declaration of September 2000 and the set of goals and quantitative indicators that emerged from it (United Nations 2000), the poverty-focused approach has necessitated a better understanding of the measurement of poverty, with more analytical and evidence-based approaches being applied to measuring and addressing poverty. As such, while material deprivation, in terms of income and assets, is still considered central to poverty, other factors such as health, education, vulnerability, voicelessness and powerlessness have joined it. But for reasons of convenience, income poverty, using monetary estimates of income or consumption, still dominates most assessments (World Bank 2001). In terms of measuring poverty, the standard international unit has been the number of people earning less than US $1 a day (Chen & Ravallion 2001). Indeed, this was the measure used in the target for Millennium Development Goal 1 (eradicate extreme poverty and hunger), which aimed to halve between 1990 and 2015 the proportion of people whose income is less than $1 a day (see http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/poverty.shtml). Recently, the choice of US $1 per day has been revisited (Ravallion et al. 2008) and using a new set of 2005 purchasing power parity data derived from updated national poverty lines and price surveys, the international benchmark has been adjusted to US $1.25. When used to assess global poverty figures, it is now estimated that 1.4 billion people, amounting to one-quarter of the population of the developing world, lived below the new international line (Chen & Ravallion 2008). This compares to an estimated 1.9 billion poor (half the population of the developing world) 25 years ago.

Measuring absolute levels of poverty is not the end of the story; diversity of poverty in a population, in other words the gap between the haves and have-nots, is an important component of well-being. This is usually expressed as the Gini coefficient (McKay 2005), which has values between 0 and 1, with 0 corresponding to the unattainable perfect equality (Denmark has a value of 0.232) and 1 corresponding to complete inequality, i.e. one household has all the wealth and all the other households have none (Namibia is high on the list at 0.707). In contrast to income, Gini coefficients have been deteriorating in the majority of countries, as the incomes of rich people grow faster than those of the poor both within and across countries (ILO 2008).

Measuring poverty is one thing, but doing something about it is another. There are many organizations and initiatives currently engaged in promoting policies of poverty reduction (see, for example, the Shanghai Agenda for Poverty Reduction, 2004; http://info.worldbank.org/etools/reducingpoverty/index.html). There is general consensus that economic growth is critical for poverty reduction, and this requires a favourable environment, including a sound climate for investment and entrepreneurship, redressing corruption and improving governance in both the public and private sectors and enhanced transparency and accountability. But while growth is necessary for poverty reduction, it is not sufficient to ensure the well-being of poor people, and similar growth rates across different countries have had dramatically different impacts on poverty indices. A fair share in the benefits of growth requires development and enactment of specific policies, together with investments in poor people.

Such policies include adequate and effective delivery of education, health and social infrastructure. The Asian Development Bank (for example) translates these principles into their policy (http://www.adb.org/poverty/pro-poor.asp), which states:

Poverty reduction, whether related to income or social and living conditions, requires conditions in which the poor can participate in, contribute to, and benefit from economic growth. Such pro-poor growth generates employment and income among the poor; enhances the productive potential of the poor (by creating economic and social infrastructure facilities and services); strengthens the governance and business environment to encourage strong private sector participation; seeks opportunities for strengthening regional cooperation and cross-border development; and promotes a growth process that is environmentally sustainable.

Poverty is declining (although the ongoing ‘credit crunch’ and global downturn may reverse this) but still with us, and we next examine how livestock enterprises can contribute to pro-poor (now often termed sustainable and inclusive) growth.

The most obvious way livestock might contribute to poverty reduction is as assets of the poor that meet livelihood needs. The last few decades have seen recognition of the importance of livestock to the poor, both rural (LID 1999; Thornton et al. 2002; IFAD 2004) and urban (Smit 1996; Baumgartner & Belevi 2001). Yet, when public resources are being allocated, livestock is often the Cinderella sector, under-appreciated and inappropriately funded. For example, in their analysis of countries’ Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSPs), Blench et al. (2003) concluded that livestock was under-represented even in countries where it underpins the economy. Similarly, resource allocation by central governments to livestock bears little relation to its contribution to African economies (OAU-IBAR 2000) and the lion's share of central funding is often taken by activities of dubious relevance to the poorest, such as export promotion in countries with little comparative or competitive advantage, or training more tertiary-level professionals where the majority of livestock keepers have no access to primary animal healthcare. The question inevitably arises: is this discrepancy owing to a lack of understanding of the contribution of livestock, or is it because poor livestock keepers are indeed of limited relevance to the elimination of global poverty?

Livestock have often received a bad press, and undoubtedly, they have the potential to harm as well as benefit the poor, by destroying environments, spreading disease or trapping people in poverty; we here argue that many of these fears may be unjustified. Concern about overgrazing and overstocking was a feature of Africa's colonial era, and the concept of ‘carrying capacity’ along with the ‘tragedy of the commons’ stigmatized pastoralism as inherently inefficient and environmentally destructive (e.g. Lamprey 1983). The image of desert sands engulfing African villages, combined with reports of ranching causing devastation to the rainforest, has led to a popular belief that livestock are responsible for worldwide environmental destruction. More recent analyses see pastoralism as an efficient exploiter of patchy resources in marginal areas, and a boom and bust population cycle as the inevitable, and indeed, appropriate corollary (Blench 2001). But, as the spectre of livestock-induced desertification has receded, concern over the contribution of livestock to global warming has emerged. Overall, livestock activities are estimated to contribute some 18 per cent to total anthropogenic greenhouse gas emission and nearly 80 per cent of all emissions from the agricultural sector (Steinfeld et al. 2006). But just 3 per cent of the world's total methane output is caused by all of the livestock in sub-Saharan Africa, which has some 166 million poor livestock keepers. It follows that if all the livestock in sub-Saharan Africa were somehow removed, it would make little difference to global warming; the impact on African livelihoods, of course, would be catastrophic across the continent.

Recent years have also seen growing concern over animals as sources of disease: around 60 per cent of all diseases are zoonotic (Taylor et al. 2001), animal-source foods are the single most common source of food poisoning, and most of the recent emerging diseases have jumped species from animal hosts. However, much of the animal-associated disease burden is preventable, treatable or controllable and while concern over zoonotic disease has soared in recent years, from a long-term perspective the per capita burden continues to decline. The last half-century saw an increase of life expectancy of 20 years in poor countries and middle-income countries and of 10 years in rich countries.

As with disease, so with nutrition: animal-source food has been implicated as a driver of epidemiological transition as infectious diseases are replaced by obesity and lifestyle diseases. On the other hand, animal-source food is energy dense and a source of high biological value protein and micronutrients, making it a valuable food for the young, pregnant and immunosuppressed (Murphy & Allen 2003). For the poor and hungry, the health benefits of animal-source food far outweigh the risks.

Moving from health to social concerns, livestock has been considered a marker for backwardness; the cattle raids of the Karimajong cluster, where warriors sing praise songs to bulls and prefer to buy cows than pay school fees (and the least loved child gets sent away to school), livestock as the currency for bride price and dowry in Africa and Asia, sacred cows wandering among traffic in Kathmandu and Delhi and pigs sharing the family home in Papua New Guinea, are all familiar examples. Again, recent years have a seen a re-evaluation highlighting the role of livestock as a safety and cargo net for the especially vulnerable (e.g. women, the poorest and people with HIV; IFAD 2004) and a ladder out of poverty (e.g. the Bangladeshi women who use their micro-credit loans to invest successively in poultry, goats and dairy; Zaman 1999).

If the negative impacts of livestock on the poor are sometimes overestimated, the positive have perhaps been underestimated. In particular, the contribution of livestock to the livelihoods of the poor who do not keep livestock is often ignored. The number of poor people involved in value addition of livestock products probably, and the number of poor consumers of livestock products certainly, exceeds the number of poor rural livestock producers. Most value addition by poor people occurs in the informal sector (because this is where most poor people work) and by definition is difficult to observe and quantify, but case studies give striking testimony. For example, animal-source foods are among the most commonly sold street foods in most countries and often are derived from animals kept in cities (FAO/WHO 2005). The street-food sector is considered the single largest informal sector employer in South Africa (von Holy & Makhoane 2006) and an employer of 60 000 people in Ghana (Tomlins et al. 2001). In Bangladesh, Omore et al. (2001) found that for 100 l of milk traded per day, 1.5 direct and 2.9 indirect jobs are generated through hawking, while, for the same amount of milk, a small-scale processor generates 5.6 direct and 4.4 indirect jobs.

The animal-source food value chain ends with ingestion, and consumers in developing countries drive the so-called livestock revolution, predicted to double global consumption of livestock products between the years 1990 and 2020 (Delgado et al. 1999). For the poor, food purchase is usually the largest expenditure, and livestock products make up around 10 per cent of this (Maltsoglou 2007). However, the current global depression may slow or reverse trends—poor people who typically spend more than half the household budget on food react to rising prices by switching to cheaper foods, which often entails switching from animal- to plant-source foods.

More indirect, but potentially important, is the impact on global poverty of livestock kept, processed and sold in developing countries by the not so poor. Economic growth is fundamental to poverty reduction and livestock is a sunrise industry that can make a substantial input to national economies. However, only a small number of developing countries have highly developed commercial livestock sectors—and debate continues on how much of these benefits ‘trickle down’ to the poorest either through employment, multiplier effects or cheap food (see LID (1999) and Upton & Otte (2004) for opposing views).

Commercial enterprises may contribute directly to poverty reduction when they build a partnership with smallholder producers, providing financial backing and access to innovation with the involvement of ‘outgrowers’ or ‘contract farmers’. This model, exemplified in the livestock sector by Farmers Choice in Kenya (http://www.farmerschoice.co.ke/) and Kalahari Kid in South Africa (http://www.kalaharikid.co.za/), improves the production efficiency of small-scale producers, provides a model for the new enterprising small-scale farmers, creates substantial employment opportunities at various stages along the value chains and provides safe products to poor consumers. While such a vertically integrated system sounds like the ideal solution to livestock's contribution to pro-poor growth, there are sadly only a handful of examples in existence so far where this has proved feasible, economically viable and effective.

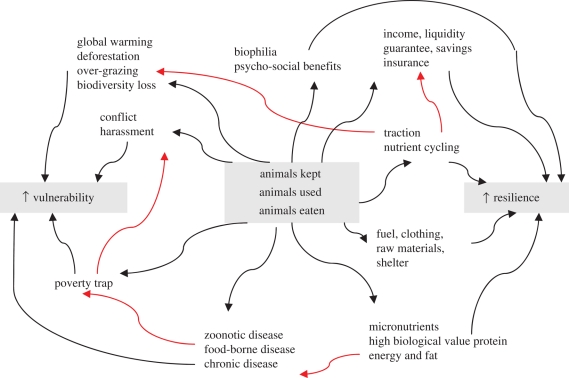

Figure 1 starts to capture some of the themes we have been discussing: the diversity of livestock's impacts, both positive and negative, on the livelihoods of the poor and the relevance of livestock not only to producers but also to intermediaries in livestock value chains and, increasingly, consumers of livestock products.

Figure 1.

Impacts of livestock on livelihoods: positive and negative, direct and indirect. Black arrows, direct link; red arrows, indirect link.

3. The role of livestock in pro-poor development processes

Given the multiple and complex interactions between livestock and poverty, how can livestock contribute to processes of pro-poor development? Returning to the frameworks for poverty reduction discussed earlier, we cite the approach to accelerating pro-poor growth proposed by the DFID (2004) and based on four pillars: creating strong incentives for investment; fostering international economic links; providing broad access to assets and markets; and reducing risk and vulnerability.

These pillars emphasize that poverty reduction is a process that involves action by many players and at many levels, not just at the level of the very poor, although clearly that is critical. As far as livestock disease is concerned, this framework has been used recently to evaluate whether foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) is a priority constraint to poverty and to assess the impacts of FMD control on poverty reduction (Perry & Rich 2007). FMD was chosen because while it undeniably constrains international market access (DFID's pillar 3), some argue that fostering external trade as a poverty-reduction tool carries with it too many complexities to make it viable (e.g. Scoones & Woolmer 2006). And Perry and Rich concluded that it depended on the strength of the role played by livestock in a given production system and the relative importance of FMD vis-à-vis other disease constraints. A series of conditions need to be met if FMD is to contribute to pro-poor growth (Perry & Rich 2007), but where these are met FMD control can indeed contribute to processes of poverty reduction.

In moving back from general frameworks for understanding policy and poverty to those specific to livestock, a landmark conceptualization is the three livestock-mediated ‘poverty-reduction pathways’ proposed by Perry et al. (2002), namely of reducing vulnerability, improving productivity performance and improving market access. This troika, while adopted by some as a broad framework for livestock's contribution to processes of poverty reduction, was originally developed to illustrate how animal diseases and their control affect the poor producer.

The first pathway is ‘reducing vulnerability’, here defined as securing the household's asset base by providing access to more reliable flows of benefits. Social surveys often report that farmers’ greatest fear is diseases that shock systems, either by suddenly and rapidly killing large numbers of animals (e.g. Newcastle disease, rinderpest) or by causing large-scale drops in demand through fear of zoonotic disease (e.g. Rift Valley fever, avian influenza); the first removes livestock assets and the second catastrophically devalues them. While the last century has seen increased capacity to contain epidemics, it has also seen greater consumer reaction (often over-reaction) to food scares. Health concerns are no longer confined to the over-nourished and ‘worried well’ in rich countries. For example, widespread media coverage resulted in a 70 per cent drop in poultry consumption before a single human or avian case was reported there, and in Viet Nam, financial losses ranging from $70 to 108 per farm were attributed mainly to the drop in consumer demand (Rushton et al. 2005). The evidence for impacts of pandemics is strong: animal plagues have wiped out livestock populations and caused the collapse of communities depending on them (Maddox 2006) and numerous economic studies have estimated the costs of epidemics (e.g. African swine fever in Cote d’Ivoire, $9.2 million; Nipah virus in Malaysia $114 million; contagious bovine pleuropneumonia in Botswana $300 million).

The role of livestock in reducing vulnerability should not be seen as restricted to securing the livestock kept by the poor, but rather encompass securing the health of the poor themselves by reducing the threat of livestock-related diseases that make poor people sick. These diseases include not only zoonoses but also diseases and suboptimal health associated with lack of animal protein and animal-source micronutrients. The evidence for the impact of zoonotic disease on human health is very strong, partly as a result of the aforementioned Global Disease Burden studies: of the 35 leading communicable causes of death, 15 are either zoonoses or have a zoonotic component. There have also been a number of systematic studies showing the high burden of food-borne diseases, the majority of which are zoonoses (Adak et al. 2005; CDC 2005; Hall et al. 2005). Unfortunately, none of the most important diseases have been thoroughly investigated in the context of developing countries.

The second pathway is specialization and intensification to increase the productivity of livestock, increasing household incomes and promoting accumulation of other assets. Diseases affecting production and productivity are primarily endemic diseases; typically these are common and kill few but sicken many animals: vector-borne disease, parasitism, bacterial and viral diseases of high morbidity and sporadic mortality are examples. To these can be added the diseases of intensification, that is diseases associated with high-input, high-output market-orientated production: mastitis, lameness, dystocia and metabolic diseases.

Evidence for the importance of endemic diseases to the poor is mixed. It is often suggested that diseases of production are important, but there is little evidence that they are a bottleneck in intensification. Indeed, animal health often makes up a surprisingly small share of total costs (Matthews 2001). In a rare example of a systematic investigation of 34 endemic diseases in Great Britain, Bennett & IJpelaar (2005) estimated the costs of disease and disease control at nearly 600 million GB pounds. Four diseases (mastitis, lameness, bovine viral diarrhoea and enzootic abortion) were responsible for two-thirds of this. This is considerably less than the 1.1 billion costs of food-borne disease (most of which is related to animal source of food) and a fraction of the total multi-billion value of the livestock sector in Great Britain.

The third pathway is improving access to market opportunities (opening new markets, reducing transaction costs) to increase the profitability of livestock activities and create incentives to increase production and sales. This has been considered a model for the livestock industry and the road blocks on this pathway are principally the ‘transboundary’ diseases, but also those diseases that present a human health risk in marketed commodities, such as cysticercosis in pig meat. The transboundary diseases, which include FMD, contagious bovine pleuropneumonia and African swine fever, are for the most part highly contagious, capable of rapid spread and have been controlled or eliminated from most rich countries, and so effectively block participation in the lucrative markets for livestock products in Europe and the Americas.

Evidence for the importance of transboundary diseases to the poor is conflicting and mainly theoretical. The Rift Valley fever ban is estimated to have cost Kenya US $32 million in lost exports to the Gulf and other negative domestic impacts on agriculture and other sectors such as transport and services (Rich & Wanyioke in press). However, most developing countries are net importers of livestock products, contributing as a whole less than 2 per cent of world export trade (Upton 2005), and with the exception of a small number of countries, livestock exports have been on a downwards trajectory. While some believe that control of livestock diseases would result in substantial opportunities through export, others argue that many developing countries have little chance at present in the highly competitive world of export trade, dominated by a small number of countries (Perry et al. 2006).

Another disease-related constraint on the market opportunities pathway is increasing concerns over the safety and quality of livestock products, particularly with regard to food-borne infections such as salmonellosis and brucellosis, and a belief that such concerns will lead to an acceleration in the growth of private standards that will force poor smallholder producers out of markets (World Bank 2005).

Once again, concrete evidence for high relevance to the poor is scanty. In many Latin American countries, the main market for milk, yoghurt and desserts shifted from small shops to the supermarkets in the 1990s. This has been directly linked to the exit of small dairy farmers (a decline of 60 000 in 10 years from production in Brazil accompanied by an average farm size increase of 55 per cent, with similar patterns in Argentina and Chile; Reardon et al. 2002). However, it has also been argued that ‘supermarketization’ is of little relevance to the poorest; supermarkets account for less than 4 per cent of urban food expenditures in almost all African countries, and even with major growth in supermarket volume, investments in traditional marketing channels will probably remain much more important for small farmers and consumer welfare for at least the next few decades (Jayne 2007).

Taking into account both the potential importance to poor people and the strength of the evidence relating livestock diseases to poverty, the ‘pathways out of poverty’ perspective suggests that zoonoses and epidemic diseases are certainly a high priority for most poor people, endemic disease is probably important though evidence is lacking, transboundary diseases are likely to be important only to subsets of the poor and there is little evidence for the importance of diseases of intensification. However, this prioritization reflects the dearth of comprehensive, multi-disease, multi-country, meta-evaluation of how diseases impact the poor both in the short term and long term, and both directly and through economy-wide effects. It may also over-represent diseases that are well researched, for example zoonoses. And finally, it reflects a focus on the impacts on poor people themselves, not on processes of poverty reduction, in which, if adopting the four pillars of pro-poor growth proposed by DFID, there might be a different weight attached to the transboundary diseases; in other words, while the direct impact of transboundary diseases on the poor is not always evident, the indirect, and effects on depressing pro-poor economic growth, although more uncertain, may be more important.

The three pathways out of poverty start in the farmyard. To use our previous terminology, they are organized around the poor as livestock keepers rather than livestock eaters or livestock users. More recent conceptualizations of livestock and poverty use broader frameworks. For example, a recent study of how animal health services could be better targeted at demand in the pastoralist areas of the Greater Horn of Africa identified two major and contrasting needs: services that protect the vulnerability of communities in the harsh region prone to extremes of floods and droughts, and services that promote better market access (Perry & Sones 2008). Both of these have specific disease components relating to priorities in this region, but they also have broader livestock enterprise support requirements that extend to infrastructural, animal feed, human well-being and other related services that need to be carefully integrated in such specific environments.

Another framework (‘The livestock revolution revisited’; K. Sones & J. Dijkman 2009, unpublished work) takes a more encompassing, and less production-focused, perspective, seeing the contribution of livestock as providing:

market opportunities for competitive small, medium and larger scale livestock businesses to produce, sell and trade in livestock and commodities derived from livestock;

employment opportunities at all three scales of livestock enterprises;

safe and affordable animal protein products to all categories of consumers;

a safety-net resource that can be drawn on by poorer sectors of society to reduce their vulnerability.

4. Our imperfect ability to assess the impacts of animal disease control

Having discussed frameworks for understanding of impacts of livestock disease on poverty, we move to metrics. Assessing the poverty-reducing impacts of controlling livestock diseases in developing countries is constrained by our limited ability to assess the poverty impacts of livestock disease itself. With no consensus metric for animal disease and with little information on prevalence and incidence, it is impossible to systematically evaluate and prioritize disease, let alone assess differential impacts. Development experience shows this is a dangerous place to be; allocating resources on the basis of tradition, anecdote and advocacy inevitably leads to an inequitable and anti-poor system. Disproportionate spending on tertiary and professional education at the expense of primary and vocational education has been shown to have adverse impacts on health, wealth and education (Gradstein 2003). On the other hand, where allocation is informed by evidence and guided by pro-poor policies, the benefits can be dramatic. The Pareto principle or Law of the Vital Few, which states that, for many events, the greater part of the effects comes from the smaller part of the causes, applies to many health situations. For example, the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study shows that six infectious diseases (20% of the total classified) are responsible for 75 per cent of the total disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) lost. Recent years have seen an increasing interest by poor countries in allocating medical expenditure to where it will have the most impact with some encouraging results. For example, by allocating medical supplies to hospitals on the basis of locally prevalent diseases, Tanzania was able to reduce infant mortality by over 40 per cent between 2000 and 2003 in two pilot districts (Neilson & Smutylo 2004).

In the absence of our ideal metric, and given the challenges of untangling the linkages between diseases and poverty-reduction processes discussed previously, estimating the importance of animal disease impacts on the poor has mainly relied on qualitative measures: asking experts and asking farmers.

In table 1, we compare assessments of the impact of cattle diseases from four different studies. The study of Perry et al. (2002) used a systematic approach in which criteria for importance to the poor were developed and weightings assigned. Around 60 in-country professionals were interviewed in four geographical areas (East and West Africa, southeast Asia and the Indian subcontinent). A group of international experts also took part in the study (Perry et al. 2002). The second expert-based study was an ad hoc survey of 190 animal health researchers, practitioners and policy makers, contacted during an epidemiology conference and by email concerning the major animal health constraints in southern countries (LDG 2004). The third stakeholder-based listing was developed by the Global Alliance for Livestock Veterinary Medicine (GALVmed), a not-for-profit global alliance with the goal of developing and ensuring access to vaccines and other animal health products to help poor farmers in the developing world (www.galvmed.org). A fourth farmer opinion survey was based on interviews with 1314 farmers in India (Pilling 2004). For comparison, we add an expert-opinion-derived list of priorities from a global perspective, the OIE list of priority diseases (OIE 2008).

Table 1.

Comparing studies to identify and in some cases rank diseases of cattle that are most important to poverty reduction or to global trade.

| expert opinion—livestock development | expert opinion—researchers | expert opinion—stakeholders | farmer opinion | expert opinion—disease experts | expert opinion—disease experts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| global: livestock diseases important to the poor | global: livestock diseases important to the poor | global: livestock diseases important to the poor | India: livestock diseases important to the poor | global: notifiablea livestock diseases | global: notifiable livestock diseases |

| Perry et al. (importance ranked) | LDG (importance ranked) | GALV med ranked by species | Pilling (importance ranked) | OIE new disease lists (alphabetically rankedb) | OIE list A (alphabetically rankedb) |

| gastro-intestinal helminthsneonatal mortality | tuberculosis trypanosomiasis | haemorrhagic septicaemia | FMD fever | bovine anaplasmosis bovine babesiosis | bovine anaplasmosis bovine babesiosis |

| FMD ectoparasites | helminthiasis FMD | contagious bovine pleuropneumoniae | diarrhoea haemorrhagic | bovine genital campylobacteriosis bovine spongiform encephalopathy | bovine brucellosis bovine cysticercosis |

| liver fluke (fascioliasis) | contagious bovine | Rift Valley fever | septicaemia | bovine tuberculosis | bovine genital campylobacteriosis |

| reproductive disorders nutrition/ micronutrients | pleuropneumonia brucellosis | tick-borne diseases trypanosomiasis | bloat liver fluke | bovine viral diarrhoea contagious bovine | bovine spongiform encephalopathy bovine tuberculosis |

| Toxocara vitulorum | rinderpest | respiratory disease | pleuropneumonia | dermatophilosis | |

| haemorrhagic septicaemia | Johnes | anorexia | enzootic bovine leukosis | enzootic bovine leukosis | |

| Brucella abortus trypanosomosis (tsetse) | helminthiasis ticks | haemorrhagic septicaemia infectious bovine rhinotracheitis/ | haemorrhagic septicaemia infectious bovine rhinotracheitis/ | ||

| mastitis | infectious pustular vulvovaginitis | infectious pustular vulvovaginitis | |||

| rinderpest | lumpy skin disease | malignant catarrhal fever | |||

| Trypanosoma evansi contagious bovine | malignant catarrhal fever theileriosis | theileriosis trichomonosis | |||

| pleuropneumonia diarrhoeal diseases | trichomonosis trypanosomosis (tsetse transmitted) | trypanosomosis (tsetse transmitted) | |||

| heartwater | |||||

| Rift Valley fever | |||||

| babesiosis | |||||

| Theileria annulata | |||||

| black-leg | |||||

| dermatophilosis | |||||

| infectious bovine rhinotracheitis | |||||

| anaplasmosis | |||||

| East Coast fever | |||||

| tick infestation |

aCriteria for notifiability are: potential for international spread; capacity for significant spread within naive populations and zoonotic potential.

bDiseases affecting multiple species are excluded.

Although the criteria for developing the list were different between studies, the lack of consensus between the lists is striking. Only FMD appears in all of the five rankings, and in those lists that are ranked, there is little agreement as to relative importance of diseases. The four studies focusing on diseases of importance to poverty identified a total of 33 diseases. Of these, 21 were only mentioned in a single study, only six appeared in two studies, again only six in three studies and none in all four studies. The six diseases for which there was most agreement on importance were: contagious bovine pleuropneumonia, East Coast fever, FMD, haemorrhagic septicaemia, helminthiasis and trypanosomosis (tsetse transmitted). All five are present in Africa and two are present only in Africa.

The greatest divergence was between experts and farmers. Half of the problems cited by farmers are clinical signs rather than diseases, resulting in an unknown overlap between categories and suggesting that farmer consultations may be a preliminary rather than definitive step in disease prioritization. Farmer disease knowledge is extremely context specific and often overestimates diseases that have visible signs (e.g. tapeworms) or that are highly publicized (e.g. FMD in South America; LDG 2004). On the other hand, farmers often underestimate diseases that have protean symptoms (e.g. tuberculosis), produce few dramatic signs (e.g. Q fever), are caused by non-visible pathogens or occur in less-valued animals. And while participatory methods are good at eliciting what concerns people, the extensive literature on the psychology of risk shows a large disconnect between what we worry about and what actually threatens us.

However, expert opinion is also problematic. The fundamental lack of knowledge on disease presence, prevalence, incidence and impacts in developing countries can hardly be overstated. Without basic information experts' opinions are likely to be little more than guesses, based on accepted (but potentially wrong) wisdom and anecdotes and reinforced by group think.

Much progress has been made in recent decades in assessing human disease burden and perhaps lessons learned here can be applied to measuring the impact of livestock disease, allowing us to arrive at a transparent, evidence-based, consensus prioritization. In recent years, the DALY, a type of health-adjusted life year (HALY), has emerged as a popular and convenient measure. This summary measure combines the impact of illness, disability and mortality on population health, including a discount factor to reflect the lower societal value on the life of the very young and old. DALYs were used in the GBD 1990 study commissioned by the World Bank in 1991 (and in the process of being updated) and are of obvious importance in measuring the impact of zoonotic livestock disease. However, they capture only a small subset of the costs associated with human disease. They consider disutility to individuals but not medical or production costs, while costs of averting behaviour and collective disutility are not usually considered in any method (table 2).

Table 2.

Different costs associated with illness in humans and tools available to estimate them. (Italics, market prices available; bold, included in health metrics; bold italic, commonly ignored.)

| cost of illness (medical) | cost of illness (production) | cost of averting behaviour | intangible costs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| collectively borne | treatment costs, (infrastructure etc.) | loss of production (GDP) | risk mitigations such as city water treatment | disutility of ill health for friends, family etc. |

| individually borne | treatment costs (insurance, medication) | loss of production (household) | risk mitigation such as boiling water, filters | disutility of ill health for individual (HALY) |

The relatively new concept of dual-burden disease is a step towards the comprehensive assessment of animal disease. Many animal diseases cause illness and death in people as well as animals (table 3), and the failure to integrate veterinary and public health economic assessments means the true impacts of zoonotic disease are systematically underevaluated.

Table 3.

Double-burden diseases, whose control will benefit both human health and contribution of livestock to livelihoods. (Italics, double-burden disease.)

| no or negligible diseases in animals | minor disease in animals | major disease in animals | |

|---|---|---|---|

| no or negligible disease burden for people | pink eye tapeworm | Newcastle disease contagious bovine | |

| pleuropneumonia | |||

| FMDs | |||

| minor disease burden to people | Norwalk virus infection | orf | avian influenza H5 current strain |

| ringworm | |||

| major disease burden for people | hepatitis | toxigenic Escherichia coli | brucellosistuberculosis |

| campylobacteriosis | |||

| cryptosporidiosis |

In Mongolia, an economic analysis of brucellosis included both medical and veterinary costs and benefits (Roth et al. 2003). This found that the public health sector reaps only approximately 10 per cent of the benefits, and regarded solely from a cost per DALY-averted perspective, brucellosis control was less attractive than other disease control expenditure options. But when the benefits for the livestock sector were added and the costs of the intervention are shared between the public health and the agricultural sector proportionally to their benefits, the control of brucellosis actually had a net gain for both sectors. This opens new approaches for the control of zoonoses in developing countries through cost contributions from multiple sectors.

Ecohealth offers another framework for broadening our understanding of disease impact. This takes a transdisciplinary systems approach that aims to integrate human, livestock, wildlife and ecosystem health, exploring their interdependence. An ecohealth perspective can help reveal otherwise hidden impacts both positive and negative. For example, animals can be sentinels of human disease (www.canarydatabase.org). Negative impacts often missed in conventional analysis include spillovers of livestock diseases into wildlife, for example, canine distemper and rabies in wild dogs in Kenya and Ethiopia, tuberculosis in badgers in the UK and opossums in New Zealand and FMD in buffaloes.

The concept of dual burden and ecohealth takes us towards a consensus and comprehensive metric that would capture the true impact of animal disease, going beyond the direct costs of livestock disease, to consider impacts on human health, wildlife and the environment and even altruistic costs (e.g. willingness to pay for other humans and non-humans to avoid illness) and existence costs (e.g. willingness to pay to preserve wildlife in existence independent of their role in providing ecosystem services).

5. Impact of disease control on global poverty—issue of technical feasibility, affordability and desirability

Assessing disease impact is necessary but not sufficient for assessing the impact of disease control. It is not automatic that because a disease has a high impact on poor people's livestock and lives, controlling the disease will have an equivalently high benefit to them. Assuming that we can assess disease impacts either using objective (the ideal impact metric) or subjective (opinion-based) methods, we next need to factor in the technical feasibility and costs of control.

Important factors influencing the feasibility of controlling disease (at least within country borders) have been identified in previous reviews (Nelson 1999; Miller et al. 2006; ITFDR 2008). Control is more difficult where the organism is present in numerous hosts and almost impossible when the organism is widespread in wild animal populations (as is the case for tuberculosis) or is able to survive outside the host for long periods. Control is only possible where infected animals can be distinguished from non-infected and the existence of carrier states and chronic or inapparent infection militate against control. Control requires the availability of effective and practical interventions. Such interventions could include a vaccine or other primary preventive, a curative treatment, or a means of eliminating vectors. Ideally, intervention should be effective, safe, inexpensive, long lasting and easily deployed. Alongside these factors related to technical feasibility, control must also be economically advantageous and politically supported.

Obviously, feasibility and cost of control are inversely correlated, and attributing a monetary value to the costs and benefits of control helps in setting priorities. For zoonotic and food-borne animal diseases, a cost-effectiveness literature is emerging; this typically estimates the cost per DALY averted (Budke et al. 2006). As a rule of thumb, interventions that cost less than US $150 per DALY averted are ‘attractive’ from a public health perspective, while those that cost US $25 per DALY averted are ‘highly attractive’ (WHO 1996, unpublished data). Of course, as discussed earlier, DALYs averted represent only a subset of the benefits of disease control.

Non-zoonotic animal disease control programmes have been evaluated on an ad hoc basis, varying in the costs and benefits they consider and the methodologies used (e.g. Perry & Randolph 1999). This makes it difficult to draw general conclusions or compare diseases. Moreover, most studies have been performed in developed countries, and those in developing countries rarely look at differential impact on the poor. A notable exception was the assessment of FMD control in Zimbabwe (Perry et al. 2003). This found that although most direct benefits accrued to large-scale, richer farmers, there were significant multiplier effects caused by disruption of export market access, affecting employment and associated industries, which amounted to three-quarters of the direct losses from an FMD-induced export ban. If we are to understand the impacts of livestock disease on global poverty, we urgently need more studies of this type.

(a). Impact of disease control: desirability

In poor countries, even cheap, highly cost-effective and technically feasible disease control programmes may not be supported because stakeholders are not willing to devote resources to control. For livestock disease control to impact on global poverty, it must also be socially feasible.

In a democracy, keeping voters happy is not only desirable but necessary, and public concern over diseases will have a large influence on the priority assigned by political decision makers who control public funding. Unfortunately, people are very poor judges of the true impact of disease, and their level of concern is typically unrelated to the actual impact. Diseases that are perceived as novel, unnatural, imposed by others, outside our personal control, highly publicized, mismanaged by authorities, benefiting someone else or occurring to famous people are considered of greater importance and hence priority, while those perceived as familiar, voluntary or non-fatal are generally underestimated (Covello & Merkhofer 1994). The enormous expense of controlling bovine spongiform encephalopathy in the UK (GBP 5 billion) is difficult to justify in terms of human deaths averted (around 25 a year); it seems unlikely that this number would have dramatically increased in the absence of intervention (DEFRA 2004), but there is little doubt that a more measured and economically rational approach would have been unacceptable. Sandman's much-quoted formula states: risk = hazard + outrage, and while the public pays too little attention to risk, experts often ignore ‘outrage’ (Sandman 1987). As poor countries become more mediatized, this phenomenon is becoming increasingly important; indeed, it may be argued that recent developing country national initiatives on Rift Valley fever and avian influenza have been largely driven by a desire to be ‘seen to be doing something’, raising the concern that resources may be diverted from more important but less newsworthy diseases (Breiman et al. 2007).

As well as being desirable to the community at large, control and the behavioural changes associated with disease control must be acceptable to those directly involved. This is a particular challenge in disease control targeting or involving livestock kept by poor people, as the presence of animal disease is often an indicator of a system that is affordable or otherwise attractive to poor people. Getting rid of disease involves other changes that may also make the system unattractive to poor people. Most disease control requires changes in practice and these, no matter how minor or inexpensive they appear to outsiders, often risk undermining the aspects of the farming system that makes it attractive to poor people. In East Africa, for example, people keep pigs which roam freely; this system requires minimal external inputs and generates low and unpredictable profits. Because sanitation is poor, cysticercosis is a problem. Cheap appropriate technologies exist for cysticercosis control (e.g. tethering pigs, exclusive use of latrines by people). However, these changes, although small in themselves, fundamentally change the system from ‘no care’ to ‘care’. Poor farmers are rarely willing to make this switch unless they get external help and better-off farmers will change even without external support, calling into question the argument for investing development resources in changing disease management behaviour.

6. The need for focused research

A major constraint to further understanding of the role of livestock in the poverty-reduction process has been the lack of investment by developing countries in agriculture, and as previously mentioned, specifically in livestock. But investment in research has been even less. It is perhaps understandable that research comes low on the priority list in many developing countries, but there is really no excuse in a global research for the development community that acknowledges poverty reduction as an over-riding aim. While there are a variety of research initiatives underway in the north, and such initiatives will undoubtedly bring some benefits to developing countries, many of the benefits will be the result of ‘spillover’ effects. It is likely that many animal diseases of high significance to protecting and enhancing the assets and vulnerability of poor rural communities, to improving market access or to the aspirations for improved productivity will not qualify for such global attention, given the low direct risk they pose to the developed world. In a recent review of animal health constraints to development, Perry & Sones (2007) considered that sectors of the affluent world are still basing their science contributions to poverty reduction on self-interest, relying on the spillover from investments designed primarily to protect themselves; they concluded that at the moment, only the crumbs go to the poor.

7. Parting questions

Before leaving the subject, we ask some speculative, and perhaps provocative, questions. How can understanding the links between livestock and poverty help better target disease control efforts? If global poverty reduction was the aim of livestock disease control, what would it look like? How much of the impact of livestock disease on global poverty is due to disease itself and how much is due to current policies towards disease control?.

How can understanding the links between livestock and poverty help better target disease control efforts? A recurring theme in this review has been the scanty (but emerging) evidence base on the impact of livestock disease on global poverty, the complexity and multiplicity of the interactions (both negative and positive) between livestock and disease and the divergence of opinion on what diseases are important to global poverty. In the absence of agreed and objective metrics that can assess the impact of livestock disease, let alone their differential impact on the poor, it is likely that current resource allocation is inefficient. Analogies from other sectors suggest that ignorance of impact and inability to prioritize foster the direction of resources by articulate interest groups. Their vested interests in a particular disease has often little to do with its contribution to poverty-reduction processes. That poverty is not the first priority is evidenced by disease control tools that would be effective in a resource-poor context but are unused for reasons that have little to do with science; for example, the lactoperoxidase system of milk preservation, which would dramatically increase the safety and market penetration of smallholder milk, and food irradiation, which could allow the export of livestock commodities with negligible risk to the consumers in developed countries, are cases in point.

As a thought experiment, we consider how would livestock disease control in developing countries differ if its poverty reduction was the over-arching concern? In a world of scarce resources, the first step would be targeting. Should efforts be focused on the poor who consume livestock products and are sickened and killed by food-borne disease, slipping into absolute poverty? Or on reducing the price of animal-source foods in order to increase children's IQ and ability to complete education? Or on enhancing value chains so they work better for the poor? As discussed earlier, we lack the tools, let alone data, to start answering this fundamental question of poverty targeting. Moving from targeting to implementation, recent decades have seen many promising innovations, which, though successful in small studies, have yet to become part of mainstream veterinary thinking or day-to-day disease control. If poverty was the focus, we might see these innovations embedded in livestock value chains. Disease control at the farm level would involve a higher proportion of primary animal workers whose services are more accessible and affordable than that of veterinarians. Control programmes would emphasize the animals of the poor (small stock and poultry) and the most vulnerable (including women). Disease control policy would put greater weight on the impact of disease on vulnerability and prioritize diseases that most constrain pathways of poverty reduction. Control strategies would recognize that most disease control is carried out by poor people themselves, design control interventions on this basis and put greater emphasis on disease control strategies that are acceptable and appropriate for poor farmers. If poverty was the focus, disease control at the level of international trade might be increasingly based on evidence and not politics and personal relations. The commodity-based trade approach would be accepted and supported as more environment and animal-welfare friendly than trade in live animals. Group certification for quality standards would be accepted, reducing the transaction costs for small farmers in meeting requirements. Outgrower schemes linking smallholder farmers would help replicate the success seen in horticulture and floriculture. If poverty was the focus for veterinary public health, we might see dual-burden assessments regularly carried out to include the effect of zoonoses on livelihoods as well as health. Most resources for controlling food-borne disease would be dedicated to the informal markets where the poor buy and sell. Decision making on food safety would take into account the contribution of informally marketed food to the livelihoods of the poor.

The final and self-avowedly contrarian of our three questions is the extent to which the impacts of livestock disease on global poverty are due to control policy rather than disease itself. The medical mindset sees disease as the enemy, and sees control as a self-evident good that needs no elaborate justification, but a closer examination suggests that many of the negative impacts of livestock disease can in fact be attributable to policy rather than pathogenicity. For example, the presence of endemic FMD in a country is often considered a self-sufficient reason for preventing the export of livestock products and for initiating national or zonal eradication programmes when eradication is clearly unattainable in the foreseeable future. Yet, the evidence is indisputable that the risk of FMD from de-boned meat derived from properly handled carcases is negligible, and this has stimulated the interest in commodity-based trade in livestock products from FMD-endemic countries (Thomson et al. 2004; Perry et al. 2005). Avian influenza control in endemic countries is still based on slaughter in a containment or ‘protection’ zone, despite emerging evidence that this is not only ineffective but also unworkable. Rich countries have repeatedly demonstrated an ability to control animal diseases, but, with the notable exception of rinderpest, the control of which was well funded by outside agencies, many of the poorest countries have consistently demonstrated an inability to control most animal diseases. In many African countries, animal disease control is deteriorating. It is at least arguable that we need to review not only disease control strategies but the underlying assumptions that disease is controllable in the absence of a well-funded and highly performing veterinary system and that any disease control (irrespective of cost, likelihood of success and unwanted side effects) is better than none.

8. Conclusion

This review has explored the complexity of linkages between livestock, livestock disease, livestock disease control and global poverty. The most obvious conclusion is that livestock probably matter to poverty reduction, but we are not sure exactly how or how much. Moreover, we have little understanding of the ‘vital few’ versus the ‘trivial many’ diseases whose control will matter most to poverty, lacking not only data but tools to measure it. The result is little consensus on which livestock diseases actually matter to poverty reduction. However, we set out considerations which would be taken into account in developing a conceptual framework that would allow this necessary identification and prioritization of livestock diseases. These include: understanding livestock bads as well as goods; considering how disease control impacts not only on the poor livestock keeper but also the more numerous actors in the livestock value chains, and of course the consumers; getting beyond the effects of disease on production to consider impacts on human health, livelihoods and the ecosystem; and taking into account not only the importance of disease but the marginal costs and social desirability of control and the role of livestock all the way along value chains and beyond. The last decades have seen a dramatic shift towards pro-poor livestock development and an exciting array of innovations. The challenge of the next few decades will be in developing methods, generating evidence and shifting mindsets so as to maximize the contribution of livestock to global health, wealth, equity and sustainability.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Jeroen Dijkman, Thomas Randolph and Keith Sones for commenting on earlier drafts of the manuscript.

Footnotes

One contribution of 12 to a Theme Issue ‘Livestock diseases and zoonoses’.

References

- Adak G. K., Meakins S. M., Yip H., Lopman B. A., O’Brien S. J.2005Disease risks from foods, England and Wales, 1996–2000. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11, 365–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner B., Belevi H.2001A systematic overview of urban agriculture in developing countries. Zurich, Switzerland: EWAG [Google Scholar]

- Bennett R. M., IJpelaar J.2005Updated estimates of the costs associated with 34 endemic livestock diseases in Great Britain. J. Agric. Econ. 56, 135–144 (doi:10.1111/j.1477-9552.2005.tb00126.x) [Google Scholar]

- Blench R.2001‘You can’t go home again’, pastoralism in the new millennium London, UK: ODI [Google Scholar]

- Blench R., Chapman R., Slaymaker T.2003A study of the role of livestock in poverty reduction strategy papers Rome, Italy: FAO [Google Scholar]

- Breiman R. F., Nasidi A., Katz M. A., Njenga M. K., Vertefeuille J.2007Preparedness for highly pathogenic avian influenza pandemic in Africa. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 13, 1453–1458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budke C. M., Deplazes P., Torgerson P. R.2006Global socioeconomic impact of cystic echinococcosis. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2, 296–303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC (Centre for Disease Control and Prevention) 2005FoodNet, Foodborne Disease Active Surveillance Network, CDC's Emerging Infections Program. See http://www.cdc.gov/FoodNet

- Chen S., Ravallion M.2001How did the world's poor fare in the 1990s? Rev. Inc. Wealth 47, 283–300 (doi:10.1111/1475-4991.00018) [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Ravallion M.2008The developing world is poorer than we thought, but no less successful in the fight against poverty Washington, DC: World Bank [Google Scholar]

- Covello V. T., Merkhofer M. W.1994Risk assessment methods New York, NY: Plenum Press [Google Scholar]

- DEFRA (Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs) 2004Costs to the UK of BSE measures. See http://www.defra.gov.uk/animalh/bse/general/qa/section9.html (Accessed 14 December 2008)

- Delgado C., Rosegrant M., Steinfeld H., Ehui S., Courbois C.1999Livestock to 2020: the next food revolution Washington, Rome and Nairobi: IFPRI, FAO and ILRI [Google Scholar]

- Department for International Development 2004How to accelerate pro-poor growth: a basic framework for policy analysis. See http://www.dfid.gov.uk/Pubs/files/propoorbriefnote2.pdf (Accessed 14 December 2008)

- FAO/WHO (Food and Agriculture Organisation/World Health Organization) 2005FAO/WHO Regional Conference on Food Safety for Africa, 3–6 October 2005, Harare, Zimbabwe Rome/Geneva: FAO/WHO [Google Scholar]

- Gradstein M.2003The political economy of public spending on education, inequality, and growth Washington, DC: World Bank [Google Scholar]

- Hall G. V., et al. 2005Estimating of foodborne gastroenteritis, Australia, allowing for uncertainty. Emerg. Infect. Dis 11, 1257–1264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IFAD (International Fund for Agricultural Development) 2004Livestock services and the poor: a global initiative collecting, coordinating and sharing experiences. Rome, Italy: IFAD [Google Scholar]

- ILO (International Labor Organisation) 2008World of Work Report 2008—income inequalities in the age of financial globalization Geneva, Switzerland: ILO [Google Scholar]

- ITFDR (International Task Force for Disease Eradication) 2008. See http://www.cartercenter.org/health/itfde/index.html . [PubMed]

- Jayne T. S.2007Underappreciated facts about African agriculture: implications for poverty reduction and agricultural growth strategies East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University [Google Scholar]

- Lamprey H.1983Pastoralism yesterday and today: the overgrazing problem. In Tropical savannas: ecosystems of the world, vol. 13 (ed. Bourliere F.), pp. 643–666 Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier [Google Scholar]

- LDG (Livestock Development Group) 2004Receptors, end-users and providers: the deconstruction of demand-led processes and knowledge transfer in animal health research Reading, PA: LDG [Google Scholar]

- LID (Livestock in Development) 1999Livestock in poverty-focused development Crewkerne, UK: LID [Google Scholar]

- Maddox G.2006Sub-Saharan Africa: an environmental history Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-Clio [Google Scholar]

- Maltsoglou I.2007Household expenditure on food of animal origin: a comparison of Uganda, Vietnam and Peru Rome, Italy: FAO [Google Scholar]

- Matthews K. H.2001Antimicrobial drug use and veterinary costs in U.S. livestock production. Washington, DC: USDA [Google Scholar]

- McKay A. Tools for analysing growth and poverty: an introduction. 2005. See www.dfid.gov.uk/Pubs/files/growthpoverty-tools.pdf. (Accessed 14 December 2008)

- Miller M., Barrett S., Henderson D. A.2006Disease control priorities in developing countries. In Control and eradication (eds Jamison D. T., et al.), pp. 1163–1176 New York, NY: Oxford University Press; (doi:10.1596/978-0-821-36179-5/Chpt-62) [Google Scholar]

- Murphy S. P., Allen L. H.2003Nutritional importance of animal source foods. J. Nutr. 133, 3932S–3935S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neilson S., Smutylo T.2004The TEHIP ‘Spark’: planning and managing health resources at the district level, Final Report Ottawa, ON: IDRC [Google Scholar]

- Nelson A. M.1999The cost of disease eradication. Smallpox and bovine tuberculosis. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 894, 83–91 (doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08048.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OAU-IBAR (Organisation of African Unity, Inter-African Bureau of Animal Resources) 2000Financing livestock and animal health services in Sub-Saharan Africa: the case of Cameroon, Ethiopia, Kenya, Mali, Tanzania and Uganda Nairobi, Kenya: OAU-IBAR [Google Scholar]

- OIE (World Organisation for Animal Health) 2008Diseases notifiable to the OIE (updated 23 January 2006). See http://www.oie.int/eng/maladies/en_classification.htm [Google Scholar]

- Omore A., Mulindo J. C., Islam S. M. F., Nurah G., Khan M. I., Staal S. J., Dugdill B. T.2001Employment generation through small-scale dairy marketing and processing: experiences from Kenya, Bangladesh and Ghana Nairobi, Kenya: ILRI; See http://www.fao.org/ag/againfo/resources/en/pubs_aprod.html#1 [Google Scholar]

- Perry B. D., Randolph T. F.1999Improving the assessment of the economic impact of parasitic diseases in production animals. Vet. Parasitol. 84, 143–166 (doi:10.1016/S0304-4017(99)00040-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry B. D., Rich K.2007The poverty impacts of foot and mouth disease and the poverty reduction implications of its control. Vet. Rec. 160, 238–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry B. D., Sones K. R.2007Poverty reduction through animal health. Science 315, 333–334 (doi:10.1126/science.1138614) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry B. D., Sones K. R.2008. Strengthening demand-led animal health services in pastoral areas of the IGAD region. Rome, Italy: FAO; See http://www.igad-lpi.org/publication/docs/IGADLPI_WP09_08.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Perry B. D., Randolph T. F., McDermott J. J., Sones K. R., Thornton P. K.2002Investing in animal health research to alleviate poverty Nairobi, Kenya: ILRI [Google Scholar]

- Perry B. D., et al. 2003The impact and poverty reduction implications of foot and mouth disease control in southern Africa, with special reference to Zimbabwe Nairobi, Kenya: ILRI [Google Scholar]

- Perry B. D., Nin Pratt A., Sones K., Stevens C.2005An appropriate level of risk: balancing the need for safe livestock products with fair market access for the poor Pro-Poor Livestock Policy Initiative Working Paper No. 23, Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) of the United Nations [Google Scholar]

- Perry B. D., Nin Pratt A., Stevens C.2006A novel classification of countries based on the importance of SPS issues to trading enterprises. In Proc. 11th Int. Symp. Vet. Epidemiol. Econom. (ISVEE), 7–11 August 2006, Cairns, Australia See http://www.sciquest.org.nz/ [Google Scholar]

- Pilling D.2004Livestock disease prioritisation and the poor: findings from India. M. Phil. thesis, University of Reading [Google Scholar]

- Ravallion M., Chen S., Sangraula P.2008Dollar a day revisited Washington, DC: World Bank [Google Scholar]

- Reardon T., Berdegué J. A., Farrington J.2002Supermarkets and farming in Latin America: pointing directions for elsewhere? London, UK: ODI [Google Scholar]

- Rich K. M., Wanyioke F.In press An assessment of the regional and national socio-economic impacts of the 2007 Rift Valley Fever outbreak in Kenya. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth F., Zinsstag J., Orkhon D., Chimed-Ochir G., Hutton G., Cosivi O., Carrin G., Otte J.2003Human health benefits from livestock vaccination for brucellosis: case study. Bull. World Health Org. 81, 867–876 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushton J., Viscarra R., Guerne Bleich E., McLeod A.2005Impact of avian influenza outbreaks in the poultry sectors of five South East Asian outbreak costs, response and potential long term control. Worlds Poult. Sci. J. 61, 491–514 (doi:10.1079/WPS200570) [Google Scholar]

- Sandman P. M.1987Risk communication: facing public outrage. EPA J. 13, 21 [Google Scholar]

- Scoones I., Woolmer I.2006Livestock, disease, trade and markets: policy choices for the livestock sector in Africa Brighton, UK: IDS [Google Scholar]

- Smit J.1996Urban agriculture—food, jobs and sustainable cities New York, NY: UNDP [Google Scholar]

- Steinfeld H., Gerber P., Wassenaar T., Castel V., Rosales M., de Hann C.2006Livestock's long shadow, environmental issues and options Rome, Italy: FAO [Google Scholar]

- Taylor L. H., Latham S. M., Woolhouse M. E.2001Risk factors for human disease emergence. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 356, 983–989 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2001.0888) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson G. R., Tambi E. N., Hargreaves S. K., Leyland T. J., Catley A. P., van Klooster G. G. M., Penrith L.2004International trade in livestock and livestock products: the need for a commodity-based approach. Vet. Rec. 155, 429–433 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton P. K., Kruska R. L., Henninger N., Kristjanson P. M., Reid R. S., Atieno F., Odero A., Ndegwa T.2002Mapping poverty and livestock Nairobi, Kenya: ILRI [Google Scholar]

- Tomlins K., Johnson P. N. T., Mahara B.2001Improving street food vending in Accra: problems and prospects. In Food safety in crop post harvest systems. Proc. Int. Workshop sponsored by the Crop Post Harvest Programme of the United Kingdom Department for International Development Harare, 20–21 September 2001, Zimbabwe [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. 2000. Millennium declaration. See http://www.un.org/millennium/declaration/ares552e.pdf .

- Upton U.2005Trade in livestock and livestock products: international regulation and role for economic development Rome, Italy: FAO [Google Scholar]

- Upton M., Otte J.2004Pro-poor livestock policies: which poor to target? Rome, Italy: FAO [Google Scholar]

- von Holy A., Makhoane F. M.2006Improving street food vending in South Africa: achievements and lessons learned. Int. J. Food. Microbiol. 111, 89–92 (doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2006.06.012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Bank 2001World development report 2000/2001: attacking poverty New York, NY: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- World Bank 2005The impact of food safety and agricultural health standards on developing country exports Washington, DC: World Bank [Google Scholar]

- Zaman H.1999Assessing the poverty and vulnerability impact of micro-credit in Bangladesh: a case study of BRAC Washington, DC: World Bank; See http://www.worldbank.org/html/dec/Publications/Workpapers/wps2000series/wps2145/wps2145-abstract.html [Google Scholar]