Abstract

Objectives

This study describes the perceptions of racism, passive and active responses to this psychosocial stressor, and it examines socioeconomic correlates of perceived racism in an economically diverse population of Black women.

Methods

The Telephone-Administered Perceived Racism Scale was administered to 476 Black women, aged 36 to 53 years, who were randomly selected from a large health plan.

Results

The percentage of respondents who reported personally experiencing racism in the past five years ranged from 66% to 93%, depending on the specific item asked. When respondents were asked about racism toward Blacks as a group, perceptions of racism were even higher. For example, 68% “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that they had personally experienced being followed or watched while shopping because of their race, and 93% reported that Blacks in general experience this form of discrimination. Strong emotional responses to racism were often reported, and though more respondents (41%) reported experiencing very strong active emotions including anger, a substantial group (16%) reported experiencing very strong passive emotions such as powerlessness. Higher education was associated with higher perceived racism, while growing up in a middle-income or well-off family was associated with lower perceived racism and reduced likelihood of passive responses to racism.

Conclusions

The high prevalence of perceived racism in this study population warrants further examination of this stressor as a potential determinant of racial health disparities. Higher education and income do not appear to protect women from experiencing racism and feeling hopeless or powerless in response.

Keywords: Perceived Racism, Racism, Racial Discrimination, Stress

Introduction

Public health has recognized the continued presence of racism and its influence on the health and social position of Black Americans as evidenced by the increasing literature on this topic.1,2 Experiences of racism may be a unique stressor in the lives of Black Americans.3,4 Although inconclusive, a number of studies have examined physiological responses to racism (broadly defined) as a psychosocial stressor.2,5–12 Yet, until recently, details of the perceived experiences of racism and the ways in which Black Americans cope with this stressor are limited.

Perceived racism is the subjective and objective experience of prejudice or discrimination.13 These experiences can elicit both emotional and behavioral responses that could adversely affect health. The stress literature suggests that the stressor alone does not affect health, but rather the coping mechanism(s) employed determine the health outcome.10,14 Krieger reported that Black women who stated that they usually accepted and kept quiet about unfair treatment were four times more likely to report hypertension than women who said they took action and talked to others.7 Knowledge of how Black Americans cope with racism as a stressor may help explain variability in effects on health.13 Mental distress, loss of aspirations, low self-esteem, and feelings of hopelessness and helplessness have each been attributed in part to racism and racial discrimination.9,10,15,16

Socioeconomic indicators such as income and education have been examined in many studies, independent of racism, as a source of racial health disparities. However, an increased burden of morbidity and mortality in minority populations persists for many health outcomes even after controlling for socioeconomic status.17,18 Williams describes racism as preceding socioeconomics and differentiating the social and economic wealth of racial groups.19 Hence, the relationship between racism and socioeconomic status is interconnected and complex.20,21 Literature examining the association between racism and socioeconomic status is limited. Two studies12,22 reported higher perceived racism for better-educated women, and one study23 found no association. Further investigation of perceived racism within a socioeconomically diverse group will help evaluate the extent to which income and education might protect minorities from this stress.24

This study sought to address the following objectives: 1) to describe perceptions of racism among Black women and their responses to this stressor; and 2) to examine the socioeconomic correlates of perceived racism in an economically diverse population.

Methods

Data for this investigation were collected as part of a study to estimate the proportion of premenopausal women who have uterine fibroids.25 Women in the study were randomly selected from the membership list of a large urban health plan in the Washington, DC area where approximately half the membership is Black. Those eligible for the assessment of perceived racism were Black participants who had completed a clinic visit, a telephone interview, and a mailed questionnaire (77% of all premenopausal Black participants). “Black” includes those women who self-reported that they were non-Hispanic Black or African-American.

The stress literature suggests that the stressor alone does not affect health, but rather the coping mechanism(s) employed determine the health outcome.10,14

Before the perceived racism interview, eligible women were sent an introductory letter. The letter included a reference card with the response choices to be used during the interview. Interviews were completed in 1999 b y trained Black telephone interviewers. Of the 527 eligible Black women, 476 participated. Eight women were not eligible because they were deceased, impaired, or in a shelter. Twenty-seven refused the interview, and 24 could not be contacted. Thus, of the 519 eligible women, 90% provided data.

The Telephone-Administered Perceived Racism Scale (TPRS), a multidimensional, psychometrically-tested instrument, was used to measure the women's perceptions of racism.4 Measures of the respondents’ individual experiences and their perceptions of how Blacks as a group experience racism along with the emotional and behavioral responses to this stressor were assessed. Cronbach α reliabilities for all scales and subscales were ≥.75 except for the passive behavioral subscale, which had a Cronbach α of .68. Test-retest reliability varied from .61 to .82.

Questions on the experiences of racism scale dealt with current experiences of racism (within the past year) and some experiences of racism that occurred in institutional settings within the past five years. The emotional and behavioral response scales included five subscales: passive emotions (hopeless, powerless), active emotions (angry, frustrated, sad and anxious), passive behaviors (does not speak up, accept or keep to oneself, and ignore or forget the racist event), internal active behaviors (praying), and external active behaviors (working harder to prove others wrong).4 For the response subscales, respondents were asked at the outset whether or not they had ever experienced racism on the job and/or in public settings. Those who did not report experiencing racism were asked to respond hypothetically to the emotional and behavioral scales.

The score on the experiences of racism scale was the sum of all items on the individual and group experiences of racism subscales. The TPRS scale and subscales were each standardized to a scale from 0 to 1 to ease interpretations of comparisons and were analyzed continuously. Scores on the emotional response subscales were also categorized into four groups corresponding to the respondents’ average response. Women were asked to what extent they felt each emotion. They could respond “not at all,” “mildly,” “moderately,” or “very.” The standardized composite scores that reflect these levels are (0) = not at all, (0.01–0.33) = mild, (0.34–0.67) = moderate, and (0.68–1) = very. The same scoring scheme was used to create the composite behavioral response subscale categories of (0) = never, (0.01–0.33) = rarely, (0.34–0.67) = some of the time, and (0.68–1) = most of the time.

The TPRS interview also included a question on race-consciousness, “How often do you think of your race?” Answer choices ranged from never to nearly constantly. Sociodemographic variables were obtained from the respondents’ mailed and telephone questionnaires that were completed during the original health study. These variables included age at the time of the TPRS interview, education, annual gross household income, and childhood social status. Educational status was categorized as high school or less, high school graduate, some college or technical school, college graduate, or post-baccalaureate degree. Income was categorized by using Medicaid status and annual household income. Those who reported an annual household income <$20,000 and/or reported receiving Medicaid were grouped together. Childhood social status was based on the respondents’ self-reported description of their childhood income status (ie, well off or middle income or quite poor or low income).

Descriptive analyses were used to determine the response frequencies and subscale averages. Linear regression models were used to test associations between socioeconomic factors and the TPRS scale and subscales. Mean scale scores for separate categories of social factors were estimated controlling for age and the other sociodemographic factors.

Results

Most (93%) of the respondents were employed at the time of the interview. The mean age of the women was 43, ranging from 36–53 years of age. Twenty percent of women had ≤12 years of education while 12% had post-baccalaureate degrees (Table 1). Eleven percent had an annual household income <$20,000 or received Medicaid; at the other extreme, 19% reported an annual household income >$80,000 a year. Nearly half of the respondents described their childhood socioeconomic condition as poor. Race consciousness varied among the women, but a quarter of them reported thinking about their race nearly constantly.

Table 1.

Characteristics of women in the Perceived Racism Study

| Characteristics | Total % (n) |

|---|---|

| Age at interview | |

| ≤40 | 28 (131) |

| 41–45 | 36 (172) |

| over 45 | 36 (173) |

| Education | |

| High school or less | 20 (93) |

| Some college or tech school | 47 (224) |

| College degree | 22 (103) |

| Post-baccalaureate | 12 (56) |

| Annual gross household income | |

| <$20,000+Medicaid | 11 (50) |

| $20,001–$40,000 | 31 (144) |

| $40,001–$60,000 | 26 (121) |

| $60,001–$80,000 | 14 (67) |

| >$80,000 | 19 (90) |

| Childhood social status | |

| Low income/quite poor | 46 (220) |

| Middle income/well off | 54 (256) |

| Frequency of race consciousness | |

| Never | 9 (41) |

| Rarely, such as once a year | 21 (100) |

| Several times a month | 24 (112) |

| Once a day | 12 (59) |

| Several times a day | 11 (53) |

| Nearly constantly | 23 (109) |

Table 2 shows the respondents’ perceptions of how Blacks as a group experience racism and their personal experiences of racism. Most women reported perceptions of racism toward Blacks as a group. For example, 93% agreed or strongly agreed that Blacks are followed when shopping, and 83% reported that suggestions made by Blacks are valued less. The percentages of personal experiences of racism were lower than those reported for the group. For example, 80% of the respondents agreed that Blacks are called insulting names because of their race, while 40% reported personally experiencing this. For 6 of the 10 situations, more than half the respondents reported at least some personal experience(s) of racism. The most common experience was “being followed when shopping” (68% reported this at least some of the time). Personal experiences of racism in institutional settings (ie, discrimination in public places, by police, when getting a loan, when seeking housing or when needing medical care) were also commonly reported (Table 2).

Table 2.

Perceptions of racism experienced by Blacks as a group and personal experiences of racism, N=476

| Experience of the Group (%) |

Personal Experiences (%) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Items | Strongly Agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | Most of the Time | Some of the Time | Rarely | Never |

| Blacks (respondent) assigned menial jobs that nobody else wants to do | 20 | 46 | 1 | 30 | 4 | 8 | 36 | 29 | 27 |

| Blacks (respondent) not asked their opinions and when asked, are not given credit for their contributions | 30 | 48 | 0.4 | 19 | 2 | 16 | 47 | 24 | 13 |

| Blacks (respondent) watched more closely than other workers | 44 | 46 | 0.8 | 9 | 0.4 | 21 | 42 | 25 | 12 |

| Whites assume Blacks (respondent) promoted or hired because of affirmative action | 25 | 50 | 1.3 | 21 | 3 | 14 | 30 | 25 | 31 |

| Blacks (respondent) are hired at a grade or starting salary at the lower end of the salary scale for position | 45 | 43 | 3 | 9 | 0.4 | 19 | 33 | 24 | 24 |

| Whites assume Blacks (respondent) have lower status jobs | 29 | 52 | 1 | 17 | 2 | 18 | 39 | 29 | 14 |

| Blacks (respondent) experience subtle pressure at work to fit in | 23 | 48 | 2 | 26 | 2 | 13 | 27 | 24 | 37 |

| Blacks (respondent) suggestions are worth less | 33 | 50 | 2 | 14 | 0.8 | 18 | 41 | 23 | 17 |

| Blacks (respondent) called insulting names because of their race* | 27 | 53 | 1 | 18 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 29 | 60 |

| Blacks (respondent) followed or watched when shopping* | 53 | 40 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 21 | 47 | 22 | 11 |

| Discriminated against when applying for a loan* | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 15 | 23 | 21 | 42 |

| Discriminated against when seeking housing* | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 9 | 17 | 19 | 54 |

| Discriminated against in medical settings* | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 4 | 19 | 26 | 51 |

| Discriminated against in public place* | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 10 | 51 | 23 | 16 |

| Discriminated against by police* | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 7 | 17 | 20 | 57 |

Timeframe of questions=within the past five years.

NA=question not asked.

Table 3 describes emotional and behavioral responses to perceived racism. Women were more likely to report active responses than passive responses. Forty-one percent reported feeling very angry, frustrated, anxious, and/or sad. “Anxious” and “sad” statistically loaded with “angry” and “frustrated” because the women reported, upon probing, that they were “anxious to do something” or that they felt “sad for the person.” However, nearly 20% of respondents reported feeling very hopeless and/or powerless (the passive emotional response subscale). Praying was the most commonly reported behavioral response to racism. More than 60% of women reported that “most of the time” they respond to racism by praying. Nearly a third of the women reported behaving passively (not speaking up, accepting or keeping to oneself, and/or ignoring or forgetting about it) at least some of the time.

Table 3.

Distribution of scores* on the TPRS active and passive emotional and behavioral response subscales, N=476

| Levels of emotional response (%): | Not at All | Mildly | Moderately | Very |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active (angry, frustrated, anxious, and/or sad)† | <1 | 17 | 42 | 41 |

| Passive (hopeless, powerless) | 21 | 34 | 29 | 16 |

| Frequency of behavioral response (%): | Never | Rarely | Some of the Time | Most of the Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal active (praying) | 8 | 9 | 20 | 64 |

| External active (working harder to prove others wrong) | 16 | 16 | 33 | 35 |

| Passive (does not speak up, accept or keep to oneself, and/or ignore or forget) | 11 | 59 | 27 | 3 |

Cell percentages were based on the average standardized subscale score for each respondent. ‘Not at all’, ‘mildly’, ‘moderately’, and ‘very’ were assigned the value or value range of 0, (0.01–0.33), (0.34–0.67), and (0.68–1), respectively. The same scoring scheme was assigned to the behavioral response subscales, based on the four levels of frequency.

Psychometric analyses grouped anxious and sad in the active emotional subscales, which is plausible because comments by the respondents indicated that sad meant “sad for the person being racist” and anxious meant “anxious to do something.”

TPRS=Telephone Administered Perceived Racism Scale.

We compared the experiences and responses to racism for three groups of women: those who reported experiencing racism both on the job and in public (64% of the respondents), those who reported an experience in only one of those settings (7% reported racism only on the job and 17% reported it only in public), and those who did not report experiencing racism in either setting (12% of the respondents) (Table 4). Women who did not report a personal experience of racism either on the job or in public had significantly lower perceptions that Blacks as a group experience racism than those who reported an experience in at least one of the settings. Women who reported a personal experience of racism both on the job and in public had significantly higher mean scores on the passive emotional response and the passive behavioral response subscales than the remaining women who reported no experience of racism or racism in only one of the settings.

Table 4.

Reports of perceived racism on TPRS scales and response subscales

| Reported Personal Experience of Racism |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| On the Job and in Public (n=306) Mean (SD) | On the Job or in Public* (n=112) Mean (SD) | Neither on the Job nor in Public (n=58) Mean (SD) | P Value† | |

| Scales3 | ||||

| Perceptions of racism towards Blacks as a group | .71 (.17)A | .58 (.21)B | .49 (.22)C | <.0001 |

| Responses to racism subscales ‡ | ||||

| Passive emotions (hopeless, powerless) | .46 (.31)A | .32 (.32)B | .37 (.32)A,B | .0002 |

| Active emotions (angry, frustrated, anxious, and/or sad)§ | .72 (.22) | .71 (.23) | .69 (.26) | .69 |

| Passive behaviors (ignore or forget, accept or keep to oneself, and/or does not speak up) | .38 (.22)A | .31 (.23)B | .28 (.23)B | .002 |

| Internal active behavior (praying) | .75 (.32) | .77 (.31) | .83 (.27) | .22 |

| External active behavior (work harder to prove others wrong) | .57 (.34) | .53 (.35) | .66 (.39) | .06 |

Respondent experienced racism on the job or in public but not in both settings.

Comparison of mean scale or subscale scores by reported personal experiences of racism.

Scale and subscales have been standardized to a range of possible values from zero to one.

Comments by the women implied “sad for the person being racist” and “anxious to do something.”

A, B, C Duncan's multiple comparison test – means with different letters are significantly different.

TPRS=Telephone Administered Perceived Racism Scale.

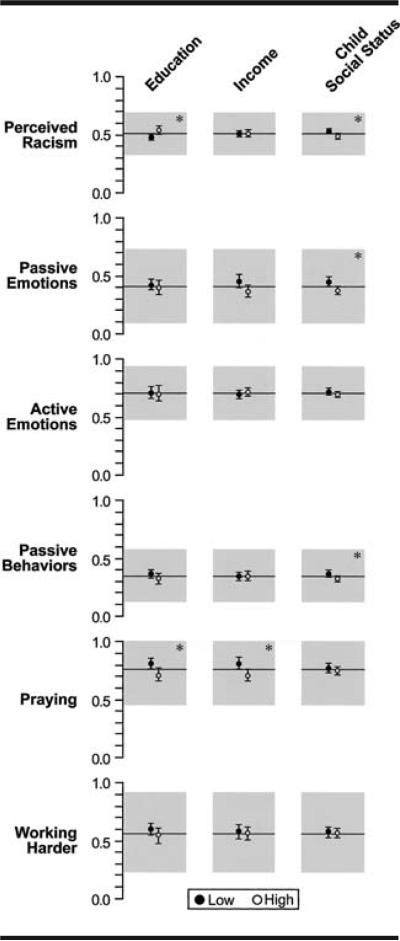

Current socioeconomic status (SES) indicators, as measured by education and income, were not strongly related to perceptions of racism or to the subscales that measure responses to racism (Figure 1). However, increased education was significantly associated with higher perceived racism (6% increase in scale score for women with post-baccalaureate education). Women with low childhood social status were more likely to have higher perceptions of racism and greater passive emotional and behavioral responses (increase in scale scores among those with low childhood SES was <6%). The active emotional response scale and the working harder scale did not differ by SES variables. Nor did praying differ much, though women with post-baccalaureate degrees and those in the highest income group (>$80,000 per year) were significantly less likely to report praying in response to racism.

Fig 1.

Association of education, income, and childhood social status with perceived racism and the emotional and behavioral response scales controlling for age. The average scale score for participants is shown for each scale by the horizontal line (standard deviation shown by shading). The estimated mean is shown for the high (open circles) and low (closed circles) categories of education (post-baccalaureate vs high school), income (>$80,000 vs <$20,000), and childhood social status (middle income or well off vs low income or poor). Standard errors of the means are represented by vertical bars. *Indicates a significant association between the social factor and the scale score

Discussion

This study examines in detail perceptions of racism and the responses to this stressor in association with socioeconomic variables (ie, education, income, and childhood social status) among Black women. Respondents were working-age women who represented a range of income and education levels as well as diverse childhood economic backgrounds. Another benefit of this study is that the respondents were randomly selected from the membership of a large health plan in the Washington, DC area. However, although women were asked to recall their perceived experiences during the past year and within the past five years, the data still reflect a snapshot of lifelong experiences of perceived racism.

Respondents overwhelmingly perceived racism against Blacks as a group, and many reported personal experiences of racism. This finding is consistent with other studies’ findings of repeated experiences of unfair treatment and disrespect.22,26 The distribution of responses to the race-consciousness question, “How often do you think of your race?” was similar to the finding reported in the Black Women's Health Study.27 In both studies, >20% of respondents reported that they think about their race nearly constantly.

In both studies [the current study and the Black Women's Health Study], >20% of respondents reported that they think about their race nearly constantly.

Emotional and behavioral responses to perceived racism are expected to influence the degree to which this stressor can affect health status.10 The women in this study reported more active responses to perceived racism than passive responses. Prayer was a particularly common form of coping. In a study by Bowen-Reid and colleagues,28 spirituality moderated the effects of racial stress on negative psychological symptoms. In our study, those who prayed reported active forms of emotional responses during perceived encounters of racism. However, they also tended to work harder to prove others wrong. The latter response may capture a form of high-effort coping or “John Henryism” that can have adverse health effect.29,30 Thirty percent responded with passive behaviors (ie, does not speak up, accept or keep to oneself, and/or ignore or forget), and 45% reported at least moderate passive emotional responses. In our study active and passive responses were not mutually exclusive.

Given the generally high perceptions of racism reported among the Black American population, those persons who do not report any experiences of racism are of interest. Kreiger and Sidney8 found that those not reporting racism had higher average blood pressures than those who reported racism. Another study hypothesized that Blacks who report not experiencing racism are those who internalize racist thinking,24 but little data have been available to evaluate this theory. We were able to take a more detailed look at this particular response group. We asked this group how they hypothetically would respond if they had experienced racism. Their hypothetical responses to racism showed higher scores (not statistically significant) on the working harder scale. Further research on the relationship between the working harder scale and the John Henryism theory that is associated with higher blood pressure is warranted.30

In comparing the frequency of exposure to perceived racism across domains (ie, both on the job and in public, either on the job or in public but not both, neither on the job nor in public), higher levels of passive emotional and behavioral coping responses were found among those with the greatest level of perceived exposure to racism. We must investigate the clinical relevance of these findings to depression and anxiety because repeated exposure to stress and the challenge of coping without adequate psychosocial resources to ensure successful management of the stressor creates a syndrome characterized by a passive style of coping with adversity and challenge known as learned helplessness.31,32 McNeilly and colleagues noted that the predictive validity of scores on the Perceived Racism Scale33 predicted depression on the Beck Depression Scale and anxiety on the Spielberger State and Trait Anxiety Scales.34

Perceptions of racism and socioeconomic status may be intertwined.8,22 In our study more education was actually associated with higher levels of perceived racism. Similarly, McNeilly and colleagues reported a significant correlation between perceived racism and higher levels of education.12 Another study found the same association, but the finding was not significant.22 Conversely, Kwate and colleagues reported no association among African-American women.23 One might intuitively expect that less educated Blacks might perceive more racism; however, they may remain in neighborhoods and in jobs where fewer Whites are present, and they have less exposure to racism from Whites. Childhood social status was also related. Controlling for current economic status and age, women who reported being very poor or of low income as children were more likely to have higher perceptions of racism and greater passive emotional and behavioral responses. Thus, economic success as an adult does not appear to protect women from the stress of perceived racism. It may even increase the stress burden.

Overt forms of racism have declined tremendously over time, and much progress has been made toward better race relations. However, these results show that the chronic stress of racism is still prevalent in the lives of many Black women despite their educational attainment. Previous research has shown that Black women have lower levels of well-being than Black males and Whites and a shorter life expectancy than White females.35,36 Given the high levels of perceived racism reported here, emphasis on the role of this stressor and passive coping responses on health outcomes such as obesity, cardiovascular disease, and depression is warranted.

Acknowledgments

The preparation of this manuscript was supported in part by the University of North Carolina Program on Ethnicity, Culture, and Health Outcomes. Data collection and analyses for this project were funded by the Intramural Research Training Program at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and a grant (1-RO3-MH61057-01) to Dr. Anissa Vines from the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors would like to thank the entire Uterine Fibroid Study staff at CODA, Inc, Research Triangle Park, NC for their hard work and commitment to this project, and the women who shared their experiences of racism during the telephone interview.

References

- 1.Williams DR, Neighbors H, Jackson J. Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: findings from community studies. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):200–208. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harrell JP, Sadiki H, Taliaferro J. Physiological responses to racism and discrimination: an assessment of the evidence. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):243–248. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanders-Thompson VL. Racism: perceptions of distress among African Americans. Community Ment Health J. 2002;38(2) doi: 10.1023/a:1014539003562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vines AI, McNeilly MD, Stevens J, Hertz-Picciotto I, Bohlig M, Baird DD. Development and reliability of a Telephone-Administered Perceived Racism Scale (TPRS): a tool for epidemiological use. Ethn Dis. 2001;11(2):251–262. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collins JW, Jr, David RJ, Symons R, Handler A, Wall SN, Dwyer L. Low-income African-American mothers’ perception of exposure to racial discrimination and infant birth weight. Epidemiology. 2000;11(3):337–339. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200005000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Armstead CA, Lawler KA, Gorden G, Cross J, Gibbons J. Relationship of racial stressors to blood pressure responses and anger expression in Black college students. Health Psychol. 1989;8(5):541–556. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.8.5.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krieger N. Racial and gender discrimination: risk factors for high blood pressure? Soc Sci Med. 1990;30(12):1273–1281. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90307-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krieger N, Sidney S. Racial discrimination and blood pressure: the CARDIA Study of young Black and White adults. Am J Public Health. 1996;86(10):1370–1378. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.10.1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neighbors HW, Jackson JS, Broman C, Thompson E. Racism and the mental health of African Americans: the role of self and system blame. Ethn Dis. 1996;6(1–2):167–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Outlaw FH. Stress and coping: the influence of racism on the cognitive appraisal processing of African Americans. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 1993;14(4):399–409. doi: 10.3109/01612849309006902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McNeilly M, Robinson EL, Anderson NB, Peiper CF. Effects of racist provocation and social support on cardiovascular reactivity in African-American women. Int J Behav Med. 1995;2(4):321–338. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0204_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McNeilly M, Anderson NB, Musick M, et al. Effects of racism and hostility on cardiovascular function and renal sodium handling in older African Americans.. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the Centers for Exploratory Studies in Older Minorities, National Institute of Aging, National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, Maryland. July 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clark R, Anderson NB, Clark VR, Williams DR. Racism as a stressor for African Americans: a biopsychosocial model. Am Psychol. 1999;54(10):805–816. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.10.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. Springer; New York, NY: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson VL. Perceived experiences of racism as stressful life events. Community Ment Health J. 1996;2(3):223–233. doi: 10.1007/BF02249424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fernando S. Racism as a cause of depression. Int J Social Psychiatry. 1984;30(1–2):41–49. doi: 10.1177/002076408403000107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krieger N, Rowley DL, Herman AA, Avery B, Phillips MT. Racism, sexism, and social class: implications for studies of health, disease, and well-being. Am J Prev Med. 1993;9(suppl 6):82–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams DR. Race and health: basic questions, emerging directions. Ann Epidemiol. 1997;7(5):322–333. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(97)00051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams DR. Race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status: measurement and methodological issues. Int J Health Serv. 1996;26(3):483–505. doi: 10.2190/U9QT-7B7Y-HQ15-JT14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forman TA, Williams DR, Jackson JS. Race, place, and discrimination. Perspect Social Probl. 1997;9:231–261. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ren XS, Amick BC, Williams DR. Racial/ethnic disparities in health: the interplay between discrimination and socioeconomic status. Ethn Dis. 1999;9(2):151–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watson JM, Scarinci IC, Klesges RC, Slawson D, Beech BM. Race, socioeconomic status, and perceived discrimination among healthy women. J Womens Health Gender Based Med. 2002;11(5):441–451. doi: 10.1089/15246090260137617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwate NO, Valdimarsdottir HB, Guevarra JS, Bovbjerg DH. Experiences of racist events are associated with negative health consequences for African-American women. J Natl Med Assoc. 2003;95(6):450–460. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krieger N. Social Epidemiology. Oxford University Press Inc; Oxford: 2000. Discrimination and health. pp. 36–75. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baird DD, Schectman JM, Dixon D, Sandler DP, Hill MC. African Americans at higher risk than Whites for uterine fibroids: ultrasound evidence. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147(11):358. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lawson EJ, Rodgers-Rose LF, Rajaram S. The psychosocial context of Black women's health. Health Care Women Int. 1999;20(3):279–289. doi: 10.1080/073993399245764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones CP, Cozier Y, Rao RS, Palmer JR, Adams-Campbell LL, Rosenberg L. Race-consciousness and experiences of racism: data from the Black Women's Health Study [abstract].. Presented at: 128th Annual Meeting of the American Public Health Association; Boston, Massachusetts. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bowen-Reid TL, Harrell JP. Racist experiences and health outcomes: an examination of spirituality as a buffer. J Black Psychol. 2002;28(1):18–36. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Light KC, Brownley KA, Turner JR, et al. Job status and high-effort coping influence work blood pressure in women and Blacks. Hypertension. 1995;25(41):554–559. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.25.4.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.James SA, Hartnett SA, Kalsbeek WD. John Henryism and blood pressure difference among Black men. J Behav Med. 1983;6(3):259–278. doi: 10.1007/BF01315113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Henkel V, Bussfeld P, Moller HJ, Hegerl U. Cognitive-behavioral theories of helplessness/hopelessness: valid models of depression? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2002;252(5):240–249. doi: 10.1007/s00406-002-0389-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seligman MEP. Depression and learned helplessness. In: Friedman RJ, Katz MM, editors. The Psychology of Depression: Contemporary Theory and Research. Winston-Wiley; New York, NY: 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 33.McNeilly M, Anderson NA, Armstead CA, et al. The Perceived Racism Scale: a multidimensional assessment of the experience of White racism among African Americans. Ethn Dis. 1996;6:154–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McNeilly M, Anderson NB, Robinson E, et al. Convergent, discriminant, and concurrent criterion validity of the perceived racism scale: a multidimensional assessment of White racism on African Americans. In: Jones R, editor. Handbook of Tests and Measurements in Black Populations. Cobb and Henry Publishers; Richmond, Calif.: 1996. pp. 359–374. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sung JF, Taylor BD, Blumenthal DS, et al. Maternal factors, birthweight, and racial differences in infant mortality: a Georgia population-based study. J Natl Med Assoc. 1994;86(6):437–443. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams DR. Racial/ethnic variations in women's health: the social embeddedness of health. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(4):588–597. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.4.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]