Abstract

The DNA-damaging agent N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (MNNG) causes cardiomyocyte death as a result of energy loss from excessive activation of poly-(ADP) ribose polymerase-1 (PARP-1) resulting in depletion of its substrates nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) and ATP. Previously we showed that the chemotherapeutic agent vincristine (VCR) is cardioprotective. Here we tested the hypothesis that VCR inhibits MNNG-induced PARP activation. Adult mouse cardiomyocytes were incubated with 100 μmol/L MNNG with or without concurrent VCR (20 μmol/L) for 2 to 4 hours. Cardiomyocyte survival was measured using the trypan blue exclusion assay. Western blots were used to measure signaling responses. MNNG-induced cardiomyocyte damage was time- and concentration-dependent. MNNG activated PARP-1 and depleted NAD+ and ATP. VCR completely protected cardiomyocytes from MNNG-induced cell damage and maintained intracellular levels of NAD+ and ATP. VCR increased phosphorylation of the prosurvival signals Akt, GSK-3β, Erk1/2, and p70S6 kinase. VCR delayed PARP activation as evidenced by Western blot and by immunofluorescence staining of poly (ADP)-ribose, but without directly inhibiting PARP-1 itself. Known PARP-1 inhibitors also protected cardiomyocytes from MNNG-induced death. Repletion of ATP, NAD, pyruvate, and glutamine had effects similar to PARP-1 inhibitors. We conclude that VCR protects cardiomyocytes from MNNG toxicity by regulating PARP-1 activation, intracellular energy metabolism, and prosurvival signaling.

Keywords: cardiac myocytes, vincristine, N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (MNNG), poly(ADP) ribose polymerase (PARP)

INTRODUCTION

Protein poly (ADP-ribosylation) is crucial for genomic integrity and cell survival and is catalyzed by poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP).1–4 Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP-1) is the most abundant and best characterized member of the PARP family.4,5 It is a nuclear enzyme that functions as a DNA damage sensor and signaling molecule that binds to DNA strand breaks and participates in DNA repair processes.2,6,7 PARP-1 uses nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) to form poly (ADP-ribose) (PAR) polymers on specific acceptor proteins. Under conditions of moderate oxidative stress, PARP-1 activation facilitates DNA repair. However, excessive PARP-1 activation depletes the cytosolic pool of its substrate NAD+, thereby impairing glycolysis, decoupling the Krebs cycle and mitochondrial electron transport, and eventually causing ATP depletion and consequent cell dysfunction and death.1,8–12

As a multifunctional DNA-bound enzyme, PARP-1 is located in cell nuclei and can be activated as a response to DNA damage.7,13,14 N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (MNNG) is a potent DNA alkylating agent and has been widely used to selectively induce PARP-1 activation.1,10,11,15 Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), which is well known to induce oxidative stress leading to DNA damage, also activates PARP-1. Although both MNNG and H2O2 at high concentrations elicit fibroblast death, fibroblasts are completely protected in PARP-1 knockout mice.1

We have reported that vincristine, a vinca alkaloid that is frequently used in combination with doxorubicin, exerts cardioprotective effects in cultured adult mouse cardiac myocytes exposed to chemical and hypoxic oxidative stress.16 We further reported that vincristine is able to protect cardiomyocytes from cell death induced by the chemotherapeutic drug doxorubicin.17 This result was associated with attenuation of doxorubicin-induced PARP activity.17 However, the sequence of events leading from PARP-1 attenuation to myocyte survival has not yet been established. We initially postulated that vincristine acts as a direct inhibitor of PARP activity induced by MNNG. Results demonstrated that vincristine is indeed capable of protecting cardiomyocytes from cardiac toxicity induced by the DNA alkylating agent MNNG through attenuation of PARP activity. However, our data indicate that there are alternative mechanisms for this effect. These include activation of prosurvival signaling pathways, regulation of ATP levels, and regulation of the PARP substrate NAD+.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Vincristine, H2O2, 2, 3-butanedione monoxime, MNNG, and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO); 3, 4-dihydro-5-[4-(1-piper-idinyl)butoxy]-1(2H)-isoquinolinone (DPQ) was purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). Antibodies against poly ADP-ribose (PAR) were from BD Biosciences (Franklin Lakes, NJ) and antibodies against GAPDH were obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Mouse laminin was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). MNNG (10 mM) was freshly prepared in DMSO such that the final concentration of the DMSO was 0.5% or less (vol/vol) when added to the culture medium. Hydrogen peroxide (10 mM) was diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) and added to the myocyte culture at concentrations described in the “Results.”

Cell Culture

Male C57Bl/6 mice weighing 19 to 25 g were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Hollister, CA) and were used for myocyte preparation. Mice received standard rodent chow and water ad libitum. The study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center. The methods for isolation and culture of adult mouse myocytes were as previously reported from our laboratory.16,17

Experimental Procedures

After 2-hour incubation of freshly isolated cardiomyocytes, media were changed to remove 2, 3-butanedione monoxime and serum in both experimental and control cells. Cardiomyocytes were treated for 2 to 5 hours with one of the following: 1) MNNG (100–200 μmol/L); 2) MNNG (100–200 μmol/L) and vincristine (20 μmol/L); or 3) vincristine (20 μmol/L) alone. To study the protective effect of PARP inhibitors, DPQ (25 μmol/L), minocycline (100 nmol/L), nonglucose metabolic substrates, pyruvate (5 mmol/L), glutamine (5 mmol/L), NAD+ (5 mmol/L), and ATP (1 mmol/L) were added 10 minutes before the addition of MNNG. Control myocytes were incubated in 2, 3-butanedione monoxime and serum-free media without addition of any chemicals.

Assessment of Cell Survival

Survival of the cultured myocytes was determined by staining cells in tissue culture dishes for 10 minutes at room temperature with trypan blue solution (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) diluted to a final concentration of 0.04 % (w/v). The calculation of myocyte survival was performed as previously reported from our laboratory.16,17 The second technique used to assess cell survival was the Live/Dead Viability/Cytotoxicity Assay kit (Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA) following the manufacturer’s instructions as previously reported.16

PARP-1 Activity Assay

PARP-1 activity was assayed by a modified protocol as previously described18 using a Colorimetric PARP Assay kit (Trevigen, Gaithersburg, MD). Histone-coated plates (96-well) were prepared by overnight incubation of histone coating solution at 4°C followed by washing four times with phosphate-buffered saline. The wells were blocked by 1× Strep-Diluent for at least 2 hours at 4°C followed by washing four times with phosphate-buffered saline. A PARP cocktail buffer containing biotinylated NAD+ and activated/damaged DNA was then added to each well. Subsequently, inhibitors and compounds of interest were added. Positive controls (PARP enzyme without inhibitors) and negative controls (without PARP enzyme) were also tested. PARP enzyme was diluted to the appropriate activity unit and added to wells. The plates were then incubated at room temperature for 60 minutes. The plates were washed four times with phosphate-buffered saline and diluted streptavidin–horseradish peroxidase was added to each well and allowed to incubate at room temperature for 20 minutes. The wells were washed four times with phosphate-buffered saline and TACS-Sapphire colorimetric substrate was added and incubated for 15 minutes in the dark. The reaction was stopped by adding 0.2 M HCl, and the absorbance at 450 nm was read.

Immunofluorescence Microscopy to Detect Poly (ADP-ribose)

To detect the changes in PAR activation, cardiomyocytes cultured on 25-mm coverglass slips in 12-well dishes were treated with a lower MNNG concentration (50 μmol/L) than described previously with or without vincristine (10 μmol/L) at different time points. This lower concentration of MNNG was found to be optimal for detecting changes in PAR induced by coincubation with vincristine. For H2O2 experiments, a lower concentration of MNNG (5 μmol/L) was added to myocyte cultures with or without vincristine (10 μmol/L). Cardiomyocytes were fixed with MEOH/acetone (70:30 v/v) for 10 minutes at 20°C. After fixation, cells were dried and phosphate-buffered saline was added to the coverglass slips and incubated for 10 minutes at room temperature. After cells were permeabilized in blocking buffer (phosphate-buffered saline, 5% nonfat dry milk [w/v], 0.1% Tween-20) for 30 minutes at room temperature, cells were incubated with purified PAR antibody at a dilution of 1:2000 for 2 hours at room temperature. Cells were washed five times in phosphate-buffered saline and reacted with Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) and visualized with a Zeiss Axiophoto fluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Peabody, MA) and recorded by a LEI-750 digital imaging system (Leica Microsystems, Inc., Bannockburn, IL).

Western Blotting

After appropriate treatments, cultured myocytes were lysed with phosphatase and protease inhibitor cocktail containing buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.1 % SDS) and the lysates were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Selected primary antibodies, appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase, and an enhanced chemiluminescence system were used for detection of proteins of interest (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). Quantitative assessment of the signals by densitometry was performed using National Institutes of Health Image 1.61 software.

NAD+ Measurement

NAD+ was assayed in intact cardiomyocytes. Cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and collected by scraping after treatment with 500 μL of 0.5 N perchloric acid. The acid treatment hydrolyzes NADH but does not affect NAD+. After 15 minutes of incubation on ice, the samples were centrifuged at 10,000 g for 5 minutes at 4°C, and the supernatant fractions were adjusted to pH 7.5 by adding 1.0 N KOH and 75 μL of 0.33 M K2HPO4/KH2PO4 (pH 7.5). After 15 minutes on ice, the insoluble KClO4 was removed by centrifugation at 1500 g for 10 minutes at 4°C. NAD+ in the extracts was measured using a modified enzymatic cycling assay.10 NAD+ standards were used to quantify NAD+ samples and were normalized to total protein measured by the bicinchonic acid method.

Statistical Analysis

All results are reported as mean ± standard error of mean. Comparisons were made by one-way analysis of variance. Post hoc analysis was performed using the Student-Newman-Keuls test. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Vincristine Prevented MNNG-Induced Cardiomyocyte Death

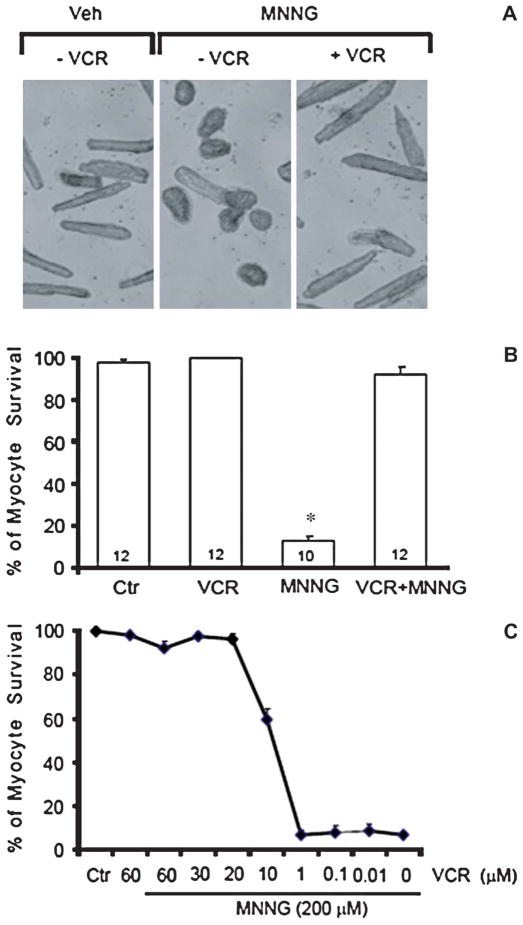

We have reported previously that vincristine decreased direct chemical oxidative stress (H2O2) in adult mouse cardiomyocytes and also rescued cells from damage caused by the anthracycline anticancer agent doxorubicin.14,16 One of the molecular mechanisms of this effect is that vincristine attenuated PARP activation induced by doxorubicin.17 To further investigate the role of vincristine and PARP activation, we treated cardiomyocytes with the PARP inducer MNNG. A representative experiment showing MNNG (200 μmol/L) incubation with and without cotreatment with vincristine (20 μmol/L) is illustrated in Figure 1A. Compared with the control, MNNG treatment was associated with large number of trypan blue-positive cells indicating cell death. With vincristine cotreatment, there was a significant decrease in trypan blue staining, suggesting persistent viability.

FIGURE 1.

(A) Typical results of trypan blue exclusion assay in a representative experiment are shown. MNNG (200 μmol/L) treatment for 2 hours was associated with an increased number of trypan blue-positive cells and a decrease in rod-shaped cells compared with the vehicle control panel. Cotreatment with 20 μmol/L of vincristine was associated with fewer trypan blue-positive cells and persistence of rod-shaped cells indicating increased survival. Cell counts are expressed as the percentage relative to control values which are set at 100%. These results were replicated numerous times (see B). VCR, vincristine; Veh, vehicle. (B) Effect of vincristine treatment on survival as measured by the trypan blue assay in cultured adult mouse cardiac myocytes in response to the DNA alkylating agent MNNG-induced stress. Cells were treated with 200 μmol/L of MNNG for 2 hours or not. Vincristine (20 μmol/L) was coincubated with or without MNNG. Cell counts are expressed as the percentage relative to control values, which are set at 100%. Numbers in bars show the number of experiments for each condition. *P < 0.01 versus control alone and vincristine. Ctr, control. (C) Concentration dependence of vincristine cotreatment on the proportion of surviving myocytes (trypan blue assay) in the presence of 200 μmol/L of MNNG for 2 hours. With 20 to 60 μmol/L of vincristine, there was greater than 90% myocyte salvage. Cell counts are expressed as the percentage relative to control values, which are set at 100%.

The results of all trypan blue exclusion assay experiments with MNNG with and without cotreatment with vincristine are illustrated in Figure 1B. MNNG (200 μmol/L) treatment of cardiomyocytes for 2 hours resulted in more than 80% cell damage, whereas cotreatment with vincristine showed minimal cardiomyocyte damage.

Figure 1C shows the concentration–response relation of vincristine on the survival of cultured adult mouse myocytes treated with MNNG. Cotreatment with 20 μM vincristine resulted in more than 95% survival of cardiomyocytes compared with untreated controls. Damage to cardiomyocytes by MNNG is time- and concentration-dependent (data not shown). Typically, MNNG at 100 μmol/L for 4 hours resulted more than 50% cell damage and MNNG at 200 μmol/L for 2 hours resulted more than 80% cardiomyocyte damage. However, vincristine (20 μmol/L) had the same protective effect against MNNG at either concentration.

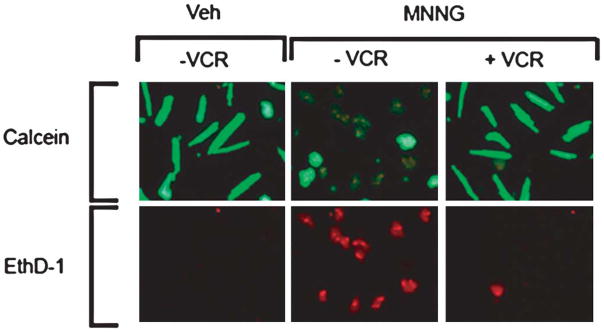

An additional set of experiments using the “Live/Dead” assay for the assessment of death and survival of cultured adult myocytes treated with MNNG and cotreatment with vincristine is illustrated in Figure 2. Without MNNG or vincristine (control) pretreatment, the proportion of viable cells (green fluorescent) was much higher than the dead cells (red fluorescent). After incubation with MNNG alone for 2 hours, more than 80% of the cells were dead. After cotreatment with vincristine, there was almost no change in the cell survival compared with the untreated control cells. Similar results were observed in four additional experiments.

FIGURE 2.

Results of Live/Dead assay are illustrated. With MNNG (200 μmol/L) treatment alone for 2 hours, there was an increased proportion of dead cells (ethidium positive/red fluorescence) and a decreased proportion of live cells (calcein ester-positive/green fluorescence) compared with vehicle treatment. With concurrent vincristine treatment (20 μmol/L), there were many more live than dead cells. This experiment was replicated four times. VCR, vincristine; Veh, vehicle; EthD-1, ethidium homodimer-1.

Vincristine Attenuated MNNG-Induced PARP-1 Activation in Cardiomyocytes

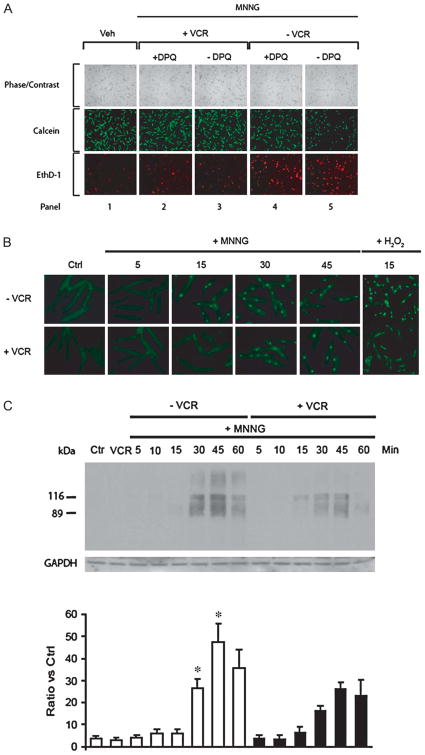

Alano et al have reported PARP-1 activation is a key factor mediating myocyte death.10 We found that the PARP inhibitors DPQ (Fig. 3A, panel 4) or PJ34 (data not shown) or minocycline (see below) partially inhibited MNNG-induced myocyte death. However, in the presence of vincristine, cardiomyocytes were almost completely protected (Fig. 3A, panels 2 and 3). Using immunofluorescence with a monoclonal antibody specific to the product poly (ADP-ribose) (PAR) of PARP-1, we observed that PAR was detected as early as 15 minutes after MNNG treatment in the absence of vincristine. With vincristine cotreatment, PAR was not detected until 30 minutes after treatment (Fig. 3B). We also used H2O2, another DNA-damaging reagent, to treat myocytes and observed similar results (Fig. 3B).

FIGURE 3.

(A) Effect of the PARP-1 inhibitor DPQ on survival of cardiomyocytes treated with MNNG. With MNNG (200 μmol/L) treatment alone for 2 hours, there was an increased proportion of dead cells (ethidium-positive/red fluorescence) and a decreased proportion of live cells (calcein ester-positive/green fluorescence) compared with DPQ treatment. The PARP inhibitor DPQ (panel 4) partially inhibited MNNG-induced myocyte death. However, in the presence of VCR, cardiomyocytes were almost completely protected (panels 2 and 3). This experiment was replicated four times with similar results. VCR, vincristine; Veh, vehicle; EthD-1, ethidium homodimer-1. (B) Effects of MNNG treatment alone and with cotreatment with vincristine on PARP activity monitored by assessment of PAR generation assayed by immunofluorescence. PAR is identified by the light green nuclear staining. PAR generation was delayed with vincristine cotreatment. Similar results were observed with hydrogen peroxide incubation during cotreatment with vincristine. Each of these experiments was repeated four times with similar results. Ctrl, control; VCR, vincristine. (C) Time course of PAR formation during MNNG treatment with or without vincristine. Upper panel: Myocytes were harvested at multiple time points during MNNG (200 μmol/L) treatment alone or in combination with vincristine (20 μmol/L). Immunoblotting was with an antibody to PAR. PAR immunostaining showed two prominent bands present at 116 kDa and 89 kDa that probably correspond to PAR formation by PARP-1. The smear of other bands likely results from PAR bonding with other proteins. The control myocytes received neither MNNG nor VCR. Lower panel: Quantification of PAR western blots. Data are means ± standard error of mean of four independent experiments. *P < 0.05 compared with the corresponding time points with vincristine. Ctrl, control; VCR, vincristine; GAPDH, glyceralde-hyde phosphate dehydrogenase.

To confirm the immunofluorescence results, we performed Western blot analysis with the same monoclonal antibody. PAR immunostaining showed two prominent bands present at 116 kDa and 89 kDa that probably represent PAR formation by PARP. Diffuse staining of proteins with other molecular weights was increased with longer MNNG incubation periods in the absence of vincristine. This increase in staining, which likely represents other proteins involved in DNA repair, was markedly attenuated in the presence of vincristine (Fig. 3C).

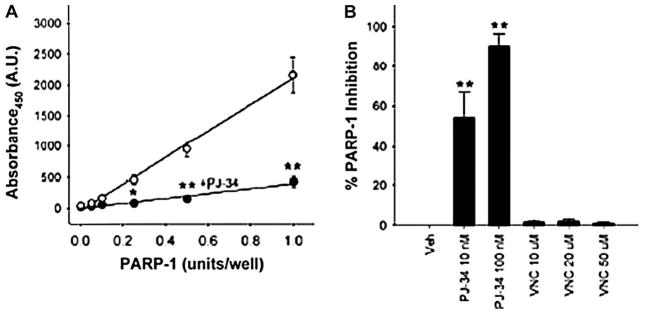

Vincristine Does Not Directly Inhibit PARP-1 Activity

We next asked if vincristine inhibits PARP-1 activity by testing vincristine in an in vitro PARP-1 activity assay. Initially, we determined that in this assay, absorbance showed a linear correlation with an increase in PARP-1 activity (Fig. 4A). This was significantly reduced by addition of the PARP inhibitor PJ-34 (Fig. 4A), verifying that the assay detects changes in PARP-1 activity. Similarly, the PARP inhibitors PJ-34 and DPQ showed a concentration-dependent increase in PARP-1 inhibition (Fig. 4B). However, at its effective concentrations (10 and 20 μM) or at lower or higher concentrations (1 and 50 μM), vincristine did not have any effect on PARP-1 activity. Thus, this in vitro assay did not provide any evidence to support the contention that vincristine-mediated cytoprotection occurs through direct inhibition of PARP-1 activity.

FIGURE 4.

Vincristine is not a direct inhibitor of PARP-1. (A) PARP-1 activity assay showing an increase in absorbance at 450 nm is directly correlated to increased PARP-1 activity units (empty circles). This increase was significantly reduced by the PARP inhibitor PJ-34 (100 nM; filled circles). n = 4, *P < 0.01 **P < 0.001 compared with the paired experiment without PJ-34 (empty circles). (B) The PARP inhibitor PJ-34 showed a dose-dependent increase in PARP-1 inhibition. Vincristine (VNC) did not inhibit PARP-1 at any of the concentrations tested. n = 3, ** P < 0.001.

PARP Activation Resulted in NAD+ and ATP Depletion in Cardiomyocytes

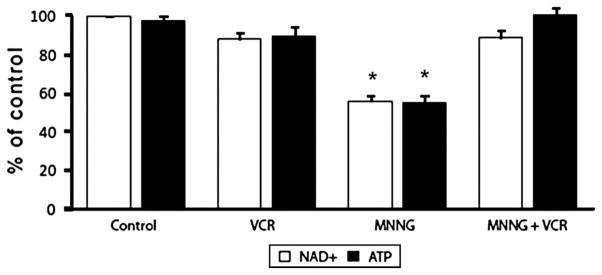

MNNG incubation led to a decrease in total NAD+ in cardiomyocytes consistent with the reports of Alano et al and Di Lisa et al.10,19 As noted, when cardiomyocytes were treated with MNNG, there was a pronounced activation of PARP catalytic activity. Treatment with MNNG (100 μmol/L) for 2 hours depleted NAD+ from cardiomyocytes by 10% to 15% (data not shown). Further treatment of MNNG for 4 to 5 hours resulted in more than a 45% depletion of NAD+ compared with the control (Fig. 5). Treatment with MNNG for 4 to 5 hours also depleted ATP from cardiomyocytes by almost 45% (Fig. 5). Concurrent vincristine treatment restored the NAD+ and ATP levels in the cardiomyocytes treated with MNNG (Fig. 5). VCR treatment alone had no significant effect on either NAD+ or ATP levels.

FIGURE 5.

NAD+ and ATP levels in cardiomyocytes treated with the PARP activator MNNG alone or cotreatment with vincristine. Myocytes exposed to MNNG (100 μmol/L) for 4–5 hours showed approximately 50% reduction in total NAD+ and ATP content. Cultures treated with vincristine (20 μmol/L) showed almost no NAD+ or ATP depletion. n = 3; *P < 0.05 versus all other conditions.

External Addition of NAD+, ATP, and Nonglucose Metabolic Substrates Reduced MNNG-Induced Cell Death

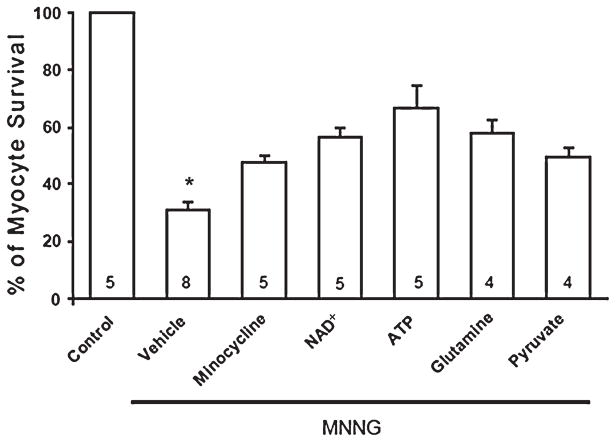

Addition of NAD+ and ATP to the extracellular medium has been reported to prevent PARP-1-induced cell death in fibroblasts and astrocytes.11,15,20 Pretreatment of cardiomyocytes with NAD+ (5 mM) and ATP (1 mmol/L) significantly improved cardiomyocyte survival during incubation with MNNG (Fig. 6).

FIGURE 6.

PARP inhibitor minocycline, extracellular NAD+, ATP, and nonglucose metabolic substrates glutamine and pyruvate reduce PARP-1-mediated myocyte death. Myocytes were pretreated with minocycline (100 nmol/L), NAD+ (5 mmol/L), ATP (1 mmol/L), glutamine (5 mmol/L), and pyruvate (5 mmol/L) for 30 minutes before treatment with 200 mmol/L MNNG for 90 minutes. Myocyte survival was measured by the trypan blue assay. Modest protection was observed with addition of extracellular NAD+ and ATP as well as by glutamine and pyruvate. The PARP inhibitor minocycline had a similar moderate protective effect. Numbers in bars indicate the number of experiments for each condition. *P < 0.05 versus all other conditions.

It has been proposed that NAD+ and ATP depletion as a result of excessive PARP-1 activation serves as a key metabolic link between DNA damage and cell death.15,21 Ying et al reported that PARP-1-induced NAD+ depletion caused glycolytic inhibition that blocked pyruvate availability to mitochondria.21 We tested this hypothesis by incubating cardiomyocytes with nonmetabolic substrates glutamine (5 mM) and pyruvate (5 mmol/L) in the presence of MNNG. As shown in Figure 6, cardiomyocytes were modestly protected from MNNG-induced damage by these substrates.

Potential Additional Mechanisms of Vincristine Cardioprotection Against MNNG-Induced Myocyte Death

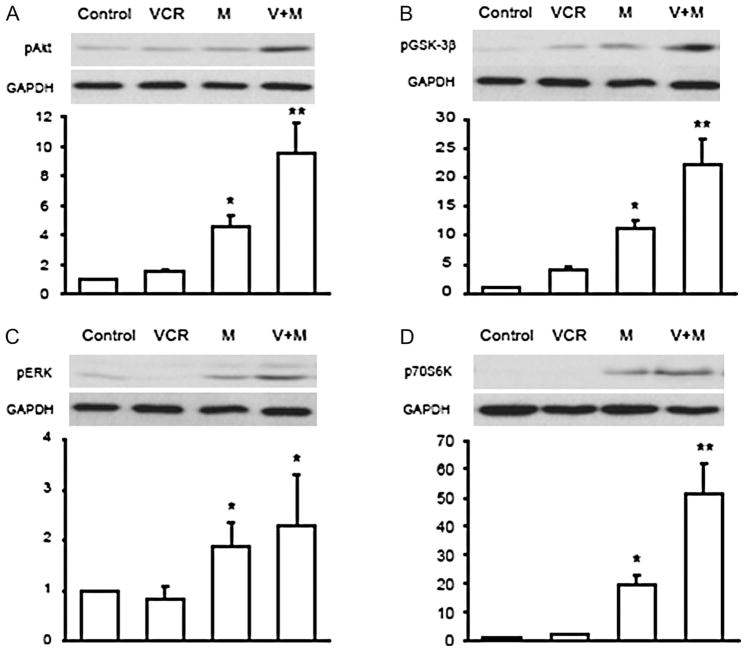

Our recent study reported that vincristine activates several prosurvival signaling pathways, which contributed to its protective effect in cultured adult mouse cardiac myocytes exposed to chemical oxidative stress as well as to the chemo-therapeutic agent doxorubicin.17 In this study, we investigated whether similar activation of prosurvival pathways contributed to the protective effect of vincristine on PARP-1-induced cell death. Cultured cardiomyocytes were incubated with MNNG (100 μmol/L) with or without vincristine (20 μmol/L) and cells were harvested after 2 hours. During this time, approximately 50% of the myocytes treated with MNNG alone lost their rod shape. This alteration in morphology was prevented by vincristine. Figure 7A–D illustrate the effects of MNNG with and without vincristine cotreatment on the phosphorylation of the prosurvival signals Akt (S473), GSK3-β, ERK, and p70S6K. Surprisingly, MNNG treatment significantly increased activation of survival signals compared with the control or vincristine treatment alone. However, the combination of MNNG and vincristine further enhanced the phosphorylation of Akt, GSK3-β, and p70S6K. In these experiments, we did not observe any significant difference in ERK activation between MNNG and vincristine.

FIGURE 7.

(A–D) Changes in phosphorylation of Akt, GSK-3β, and ERK and p70S6K in cultured adult mouse myocytes after 2 hours of MNNG (100 μmol/L) with or without vincristine (20 μmol/L). The upper panels show representative Western blots and the bottom panels show the fold-increase in signal intensity. Experiments were repeated five times. *P < 0.05 versus each respective control. **P < 0.05 versus MNNG treatment alone. VCR, vincristine; M, MNNG.

DISCUSSION

The principal new finding of the present study is that the vinca alkaloid vincristine provided dramatic salvage of cultured adult mouse myocytes continuously exposed to high doses of the DNA alkylating agent MNNG, a potent activator of PARP-1. In the presence of MNNG, NAD+ and ATP levels were depleted, but cotreatment with vincristine resulted in maintenance of cellular NAD+ and ATP. Furthermore, vincristine promoted cell viability by markedly activating prosurvival signals under stress conditions and was associated with attenuation of PARP activity. These data provide novel information regarding the mechanism of vincristine’s surprising cardioprotective effects previously observed in our laboratory.16,17

We also tested the hypothesis that vincristine acts as a modulator of PARP activity. MNNG induces DNA strand breaks, which cause excessive activation of the nuclear enzyme PARP-1, leading to depletion of intracellular NAD+ and ATP resulting in cell death. When PARP-1 is activated, there is increased synthesis of the PAR polymer. Thus, by monitoring PAR production, the activity of PARP-1 can be assessed. In the present study, MNNG alone produced a strong PAR signal detected after 30 to 60 minutes, but vincristine cotreatment markedly attenuated this signal (Fig. 3C). We interpret the difference in the time course of PAR appearance as a biomarker of the delay in PARP activation and subsequent reduction in myocyte death produced by vincristine. These findings suggest that inhibition of MNNG-induced PARP-1 activity by vincristine contributes to its protective effect. However, an in vitro assay using recombinant PARP-1 showed that vincristine did not directly inhibit PARP-1 activity (Fig. 4). In additional experiments, we found alternative mechanisms of cardioprotection afforded by vincristine include regulation of ATP levels and of the PARP substrate NAD+.

Prior studies in mouse astrocyte cultures have demonstrated that normalization of cellular NAD+ after exposure to MNNG restored glycolytic function and prevented cell death.22,23 PARP gene disruption is known to reduce postischemic injury in the heart.24 In a rat Langendorff model of ischemia/reperfusion injury, PARP inhibition facilitated recovery of high-energy phosphates after ischemia/reperfusion injury.25 Previously, we reported that MNNG treatment activated PARP-1 in four different cell types (rat and mouse cardiac myocytes, mouse cortical neurons, and mouse cortical astrocytes).10 In all four cell types, MNNG caused a reduction in total NAD+ content and cell death, which could be blocked by the PARP-1 inhibitor DPQ as well as by cyclosporine-A, an inhibitor of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore.10

In this connection, Pillai et al reported that a 60% reduction in NAD+ was associated with 60% mortality in hypoxic neonatal rat ventricular myocytes.26 Similarly, Tatsumi et al, also working with neonatal rat ventricular myocytes, noted that a reduction of ATP to 30% of control was associated with a 43% reduction in cell viability.27 Similar results for both NAD+ and ATP were reported in isolated rat hearts subjected to ischemia/reperfusion injury.25

Consistent with these findings, our current experimental data demonstrated that vincristine prevented the reduction in NAD+ and ATP induced by MNNG. We also showed that exogenous replacement of ATP and NAD+ had a beneficial effect on cardiac myocyte survival. Taken together, these observations provide the first evidence that vincristine is capable of regulating both intracellular NAD+ and ATP levels that preserve cardiac myocyte viability during PARP activation. Comparison of the combined effect of the PARP inhibitor DPQ and vincristine (Fig. 3A, panel 2 versus DPQ alone, panel 4) suggests the possibility that these agents are acting through additive mechanisms, ie, PARP-1 inhibition and maintenance of metabolic substrates, respectively.

In a rat Langendorff model of ischemia/reperfusion injury, one prior study has shown that PARP inhibitors facilitated phosphorylation of the prosurvival signals Akt and GSK-3β.28 We previously reported that activation of PI3K/Akt and MAPK/ERK signaling pathways by vincristine is essential for survival of adult mouse cardiomyocytes exposed to H2O2 and doxorubicin.16,17 Similar to doxorubicin, MNNG-induced activation of survival signals may constitute an attempt at compensation, but the level of these responses is not sufficient to prevent myocyte death. Like the enhanced signaling response observed with doxorubicin + vincristine,17 coincubation of vincristine and MNNG resulted in greater activation of prosurvival signals that likely contribute to myocyte survival. However, the mechanism by which vincristine activates prosurvival signals remains unknown, and additional studies are needed.

In summary, vincristine prevents MNNG-induced PARP-1 activation and cardiac cell death by maintaining NAD+ and ATP levels and concurrently by activating prosurvival signaling pathways. Although our data indicate that vincristine does not have direct inhibitory effects on PARP-1 activity, these observations do not exclude the possibility that PARP-1 activity is regulated by vincristine through other pathways that converge on PARP-1. How vincristine achieves these effects requires further investigation.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Foundation for Cardiac Research, University of California San Francisco (K.C.); POI HL68738 and 1R01 HL090606 (J.S.K.) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health; and a VA Merit Award from the Research Service, Department of Veterans Affairs (C.C.A.).

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ha HC, Snyder SH. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase is a mediator of necrotic cell death by ATP depletion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:13978–13982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D’Amours D, Desnoyers S, D’Silva I, et al. Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation reactions in the regulation of nuclear functions. Biochem J. 1999;342:249–268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pieper AA, Verma A, Zhang J, et al. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase, nitric oxide and cell death. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1999;20:171–181. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01292-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacobson MK, Jacobson EL. Discovering new ADP-ribose polymer cycles: protecting the genome and more. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:415–417. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01481-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shall S, de Murcia G. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1: what have we learned from the deficient mouse model? Mutat Res. 2000;460:1–15. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(00)00016-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bramson J, Prevost J, Malapetsa A, et al. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase can bind melphalan damaged DNA. Cancer Res. 1993;53:5370–5373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Virag L, Szabo C. The therapeutic potential of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors. Pharmacol Rev. 2002;54:375–429. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.3.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ying W. NAD+ and NADH in cellular functions and cell death. Front Biosci. 2006;11:3129–3148. doi: 10.2741/2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pacher P, Szabo C. Role of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP-1) in cardiovascular diseases: the therapeutic potential of PARP inhibitors. Cardiovasc Drug Rev. 2007;25:235–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3466.2007.00018.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alano CC, Tran A, Tao R, et al. Differences among cell types in NAD(+) compartmentalization: a comparison of neurons, astrocytes, and cardiac myocytes. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:3378–3385. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alano CC, Ying W, Swanson RA. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1-mediated cell death in astrocytes requires NAD+ depletion and mitochondrial permeability transition. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:18895–18902. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313329200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Szabo C, Dawson VL. Role of poly(ADP-ribose) synthetase in inflammation and ischaemia–reperfusion. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1998;19:287–298. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(98)01193-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou HZ, Swanson RA, Simonis U, et al. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 hyperactivation and impairment of mitochondrial respiratory chain complex I function in reperfused mouse hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H714–H723. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00823.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faro R, Toyoda Y, McCully JD, et al. Myocardial protection by PJ34, a novel potent poly (ADP-ribose) synthetase inhibitor. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73:575–581. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)03329-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ying W, Alano CC, Garnier P, et al. NAD+ as a metabolic link between DNA damage and cell death. J Neurosci Res. 2005;79:216–223. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chatterjee K, Zhang J, Honbo N, et al. Acute vincristine pretreatment protects adult mouse cardiac myocytes from oxidative stress. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;43:327–336. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chatterjee K, Zhang J, Tao R, et al. Vincristine attenuates doxorubicin cardiotoxicity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;373:555–560. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.06.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alano CC, Kauppinen TM, Valls AV, et al. Minocycline inhibits poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 at nanomolar concentrations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9685–9690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600554103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Di Lisa F, Menabo R, Canton M, et al. Opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore causes depletion of mitochondrial and cytosolic NAD+ and is a causative event in the death of myocytes in postischemic reperfusion of the heart. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:2571–2575. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006825200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sevigny MB, Silva JM, Lan WC, et al. Expression and activity of poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase in cultured astrocytes, neurons, and C6 glioma cells. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2003;117:213–220. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(03)00325-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ying W, Chen Y, Alano CC, et al. Tricarboxylic acid cycle substrates prevent PARP-mediated death of neurons and astrocytes. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:774–779. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200207000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ying W, Garnier P, Swanson RA. NAD+ repletion prevents PARP-1-induced glycolytic blockade and cell death in cultured mouse astrocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;308:809–813. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01483-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ying W, Alano CC, Garnier P, et al. NAD+ as a metabolic link between DNA damage and cell death. J Neurosci Res. 2005;79:216–223. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pieper AA, Walles T, Wei G, et al. Myocardial postischemic injury is reduced by poly(ADP ribose) polymerase-1 gene disruption. Mol Med. 2000;6:271–282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Halmosi R, Berente Z, Osz E, et al. Effect of poly(ADP ribose) polymerase inhibitors on the ischemia–reperfusion-induced oxidative cell damage and mitochondrial metabolism in Langendorff heart perfusion system. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;59:1497–1505. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.6.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pillai JB, Isbatan A, Shin-Ichiro I, et al. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1-dependent cardiac myocyte cell death during heart failure is mediated by NAD+ depletion and reduced Sir2α deacetylase activity. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:43121–43130. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506162200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tatsymi T, Shiraishi J, Keira N, et al. Intracellular ATP is required for mitochondrial apoptotic pathways in isolated hypoxic rat cardiac myocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;59:428–440. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(03)00391-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kovacs K, Toth A, Deres P, et al. Critical role of PI3-kinase/Akt activation in the PARP inhibitor induced heart function recovery during ischemia–reperfusion. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;71:441–452. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]