Abstract

The high affinity receptor for IgE, Fc epsilon receptor I (FcϵRI), is an activating immune receptor and key regulator of allergy. Antigen-mediated cross-linking of IgE-loaded FcϵRI α-chains induces cell activation via immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs in associated signaling subunits, such as FcϵRI γ-chains. Here we show that the human FcϵRI α-chain can efficiently reach the cell surface by itself as an IgE-binding receptor in the absence of associated signaling subunits when the endogenous signal peptide is swapped for that of murine major histocompatibility complex class-I H2-Kb. This single-chain isoform of FcϵRI exited the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), trafficked to the Golgi and, subsequently, trafficked to the cell surface. Mutational analysis showed that the signal peptide regulates surface expression in concert with other described ER retention signals of FcϵRI-α. Once the FcϵRI α-chain reached the cell surface by itself, it formed a ligand-binding receptor that stabilized upon IgE contact. Independently of the FcϵRI γ-chain, this single-chain FcϵRI was internalized after receptor cross-linking and trafficked into a LAMP-1-positive lysosomal compartment like multimeric FcϵRI. These data suggest that the single-chain isoform is capable of shuttling IgE-antigen complexes into antigen loading compartments, which plays an important physiologic role in the initiation of immune responses toward allergens. We propose that, in addition to cytosolic and transmembrane ER retention signals, the FcϵRI α-chain signal peptide contains a negative regulatory signal that prevents expression of an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif-free IgE receptor pool, which would fail to induce cell activation.

Keywords: Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER), Immunology, Intracellular Processing, Intracellular Trafficking, Membrane Proteins, ER Quality Control, Fc Receptor, IgE, Type I Membrane Protein

Introduction

Cell surface expression of FcϵRI,2 the high affinity receptor for IgE, regulates the magnitude of allergic responses (1–3). FcϵRI is part of the family of multimeric immune recognition receptors, also referred to as activating immune receptor complexes (4–6). IgE-allergen-mediated cross-linking of the FcϵRI α-chain induces the release of inflammatory mediators via ITAMs of the associated signaling subunits, FcϵRI-β and a dimer of FcϵRI-γ chains (7, 8). FcϵRI α-chain transport from the ER to the cell surface is a tightly regulated trafficking process because susceptibility to IgE-mediated cell activation depends on the display of IgE-binding epitopes by FcϵRI-α (3, 9, 10).

The ER quality control system monitors correct folding as well as co- and post-translational modifications of proteins and protein complexes (11–13). Several regulatory mechanisms that modulate the ER exit of FcϵRI complexes have been described. All of the ER protein quality control steps for type I membrane proteins apply to the FcϵRI α-chain (14). Synergistic ER retrieval signals are described for FcϵRI-α: two dilysine motifs, Lys212–Lys216 and Lys226–Lys230, in the cytosolic tail and the charged transmembrane amino acid Asp192 (15, 16). In human cells, these ER retrieval signals are overcome by the assembly of FcϵRI-α with FcϵRI-γ, the common Fc receptor γ-chain (3). In contrast, murine FcϵRI-α requires assembly with both FcϵRI-γ and FcϵRI-β to reach the cell surface. Hartman et al. (17) suggested recently that the difference in ER exit requirements between human and murine FcϵRI-α is encoded entirely in the extracellular domain of the protein. Furthermore, N-linked glycosylation of the IgE-binding epitopes of FcϵRI-α has been described as a checkpoint of the ER quality control system (18). Interestingly, the formation of IgE-binding epitopes depends only on proper core glycosylation in the ER and can occur completely independent of other receptor subunits (18).

Another key control step for the formation of FcϵRI complexes is the requirement for cotranslational assembly of the FcϵRI α-chain with its signaling subunits (19). This is different from assembly mechanisms defined for other activating immune receptors, such as the T or B cell receptors, that do not depend on coordinated translation of their subunits for receptor complex formation (4, 20). After the removal of all known transmembrane and cytosolic retention signals in FcϵRI-α, a substantial amount of the protein still remains intracellular (15, 18, 21). These findings suggest that an as yet undefined sequence element prevents surface expression of the FcϵRI α-chain in the absence of FcϵRI-γ. Therefore, we revisited the regulatory mechanisms for the display of FcϵRI-α at the cell surface.

Type I membrane proteins, including FcϵRI-α, contain a short cleavable N-terminal sequence called the signal peptide. The signal peptide sequence assures proper translocation into the ER; it binds the signal recognition particle and later is cleaved on the ER lumenal side by signal peptidases. Signal peptides have no bona fide consensus sequences, although they commonly contain a highly hydrophobic stretch (typically 10–15 amino acids) long that is preceded by a basic residue and followed by a cleavage site for the signal peptidase. A growing body of evidence suggests that signal sequences are actively involved in the quality control of type I proteins (22, 23). We thus hypothesized that the signal peptide of FcϵRI-α provides a control element for ER exit and surface trafficking. Such a control module could operate in two ways: it could facilitate the cotranslational assembly of the receptor subunits, and it could prevent surface expression of a single α-chain receptor isoform without signaling subunits. Here we show that the endogenous signal peptide of FcϵRI-α does indeed contain a regulatory element that controls ER exit and consecutively cell surface expression of this protein.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Antibodies

Anti-human FcϵRI-α monoclonal antibodies (mAb) 19-1 and 15-1 and polyclonal rabbit anti-α-chain serum 997 were kindly provided by Dr. J.-P. Kinet (Laboratory of Allergy and Immunology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA) and used as published (24, 25). The mAb 19-1 reacts only with FcϵRI-α chain that expresses the IgE binding epitopes (ER and Golgi modified forms). IgE (Serotec) and antibody 15-1 recognize the IgE-binding epitope and were used for detection of the properly folded and N-glycosylated form of the α-chain. Phycoerythrin-conjugated or allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-human FcϵRI-α antibody CRA1 and the appropriate mIgG2b isotype controls were purchased from eBioscience. Anti-FcϵRI-γ polyclonal serum was purchased from Millipore, and peroxidase-conjugated anti-HA (3F10) was from Roche Applied Science. Anti-eGFP serum was a kind gift from Dr. H. Ploegh (Whitehead Institute, Cambridge, MA). Mouse anti-human GM130 antibody (BD Biosciences) was used to visualize the Golgi compartment.

FcϵRI α-Chain Constructs

cDNAs encoding the FcϵRI-α- and γ-chains have been previously published (19). The first 25 amino acids of the endogenous α-chain (endo-α) contain the predicted signal peptide of this protein and were replaced with the first 22 amino acids of the H2-Kb protein using a two-step PCR cloning strategy according to the literature (26), and this construct was termed Kb-α. Cytosolic tail truncations of endo-α as well as Kb-α were generated by introduction of a stop codon following the transmembrane region at position 199 using PCR cloning. A construct that lacks the signal peptide was generated with an N-terminal primer starting at position 26 of FcϵRI-α. HA tags were introduced by using a C-terminal primer that contained the tag sequences prior to the stop codon. Signal peptide point mutants at position 6 of endo-α, endo-αE/K, and endo-αE/A were generated with the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer's guidelines. All of the constructs were subcloned into pcDNA3.1 and pIRES2-eGFP expression vectors and verified by sequencing.

Cell Lines and Transient Transfections

293T, HeLa, and MelJuso cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium as previously described (19). Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and FuGENE 6 (Roche Applied Science) were used to transiently transfect cells following the manufacturer's protocols. The cells were trypsinized and harvested 48 h post-transfection.

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting

The cells were solubilized in lysis buffer (0.5% Brij 96, 20 mm Tris, pH 8.2, 20 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, 0.1% NaN3) containing protease inhibitors (Complete; Roche Applied Science) for 30 min on ice. Immunoprecipitation was performed with IgE specific for the hapten NP (Serotec) and NIP beads (Sigma) as previously described (27). The proteins were eluted from beads in nonreducing Laemmli sample buffer, and samples were run on 12% nonreducing SDS-PAGE gels, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Pierce) and probed with the anti-FcϵRI-α antibody 19-1 followed by peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG for detection of precipitated α-chain. HA-tagged proteins were detected with peroxidase coupled 3F10 (Roche Applied Science). FcϵRI-γ was detected with polyclonal anti-FcϵRI-γ serum followed by peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG. Peroxidase activity was detected using SuperSignal chemiluminescent substrate reagents (Pierce). Endoglycosidase H (EndoH) and PNGase F (Roche Applied Science) digestions were performed according to manufacturer's instructions.

FACS Analysis and Cell Sorting

The cells were stained with either phycoerythrin-conjugated or allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-FcϵRI-α antibody CRA1 or appropriate isotype control antibodies and analyzed on a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) using CellQuest software for acquisition and analysis. For staining of intracellular FcϵRI-α, the cells were fixed and permeabilized using Fix & Perm reagents (CALTAG Laboratories; Invitrogen) prior to staining. Cell sorting was performed on a Moflow cell sorter (DAKO).

RT-PCR and Real Time RT-PCR

RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) performing on column DNaseI digestion. cDNA synthesis was carried out with SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase Super Mix using oligo(dT) primers (Invitrogen). To detect the human Fc receptor γ-chain, the following primers were used: forward, 5′-ACGGGCCTGAGCACCAGGAA-3′, and reverse, 5′-GGGGTAGGGCCAGCTGGTGT-3′. Human FcϵRI-α chain expression was quantified by real time PCR using iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) on a iCycler iQ5 (Bio-Rad). For FcϵRI-α, β-actin and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase QuantiTect primers were purchased from Qiagen.

Immunofluorescence Microscopy

Immunofluorescence experiments were performed essentially as previously described (28) with minor modifications. To visualize Golgi trafficking of FcϵRI-α, MelJuso cells were allowed to attach to coverslips and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences) for 20 min at room temperature prior to permeabilization in a 0.5% saponin, 3% bovine serum albumin, phosphate-buffered saline solution. Polyclonal rabbit serum 997 was used to detect α-chains. An antibody against GM130 was used to visualize the Golgi compartment. Goat anti-mouse F(ab′)2 fragment labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 (Molecular Probes) and goat anti-rabbit Alexa F(ab′)2 fragment labeled with Fluor 568 (Molecular Probes) were used as the fluorescent probes. The images were collected on a Zeiss Axiophot upright microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc., Thornwood, NY) with a Spot scientific grade cooled CCD camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Inc., Sterling Heights, MI).

For FcϵRI α-chain internalization, HeLa cells transiently transfected with Kb-α were grown on coverslips (No. 1.5) stained first with purified mouse anti-FcϵRI-α antibody CRAI for 20 min at 37 °C and subsequently with an goat anti-mouse F(ab′)2 fragment labeled with Alexa Fluor 568 for 30 min at 37 °C to induce receptor cross-linking. The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min and mounted using Prolong Antifade reagent (Invitrogen). Both antibodies were diluted in Hanks' balanced salt solution supplemented with 10 mm HEPES (Invitrogen) and 5% NuSerum (Invitrogen). CRA I was diluted at 1:100, and anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 568 was diluted at 1:400. Plasma membranes of fixed cells were stained with Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated wheat germ agglutinin (diluted at 1:1000) for 10 min. All of the incubation steps were carried out in a humidified chamber. Confocal images were acquired on a Nikon TE2000 inverted microscope coupled to a Yokogawa spinning disk confocal unit (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) and an Orca AG scientific grade cooled CCD camera (Hamamatsu Photonics K.K.). Slidebook software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations Inc.) was used for image capture, processing, and analysis. The LAMP-1-eGFP vector, kindly provided by Dr. Tomas Kirchhausen (Immune Disease Institute, Children's Hospital Boston), was transfected into HeLa cells, and stably transduced cells were selected with G418 (1 mg/ml).

Statistical Analysis

All of the graph data represent the means ± S.E. of the indicated number of independent experiments (at least three). Statistical analysis was performed using the paired, two-tailed Student t test for comparison of two groups; p values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Efficiency of the ER Exit of the FcϵRI α-Chain Depends on Its Signal Peptide

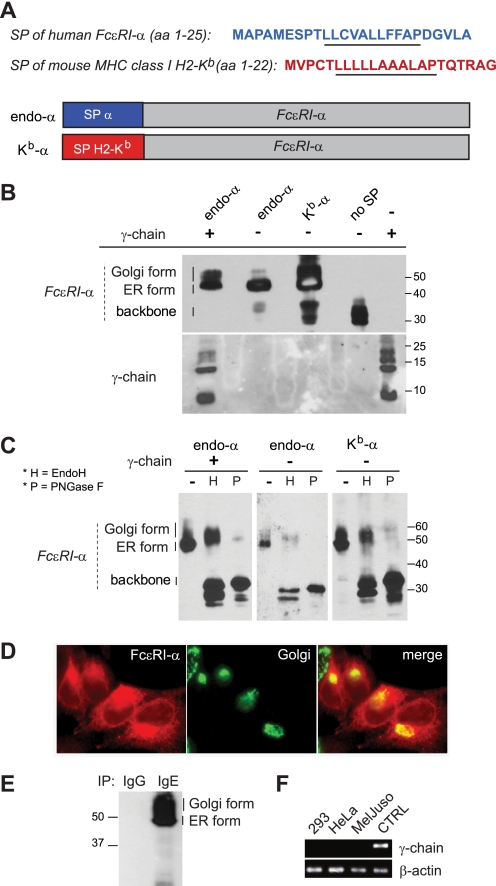

We wanted to test the hypothesis that the signal peptide of the FcϵRI α-chain contains a module to regulate ER exit of this protein in its properly folded IgE-binding form. Therefore, we compared the intracellular trafficking of FcϵRI-α with its endogenous signal peptide (referred hereafter as endo-α) with a chimeric FcϵRI α-chain that had its signal peptide swapped for that of H2-Kb (referred hereafter as Kb-α). A comparison of both signal peptides is shown in Fig. 1A. The H2-Kb signal peptide is highly efficient at driving expression of the murine major histocompatibility complex class I H2-Kb molecule and is thus commonly used to optimize expression of type I membrane proteins in vivo and in vitro (19, 20, 29, 30). A summary of all constructs used in this study is given in Table 1. Because FcϵRI-α becomes highly glycosylated on its way from the ER to the cell surface, modifications of N-glycans on the FcϵRI α-chain can be used to monitor proper ER to Golgi trafficking of the protein. 293T cells were transiently transfected with FcϵRI endo-α or Kb-α constructs, and the molecular properties of the translation products were compared (Fig. 1, A and B). All of the constructs were tagged with HA at the C terminus to allow for detection of the FcϵRI-α-chain irrespective of its folding stage. We used the molecular weight characteristics of endo-α in the presence of FcϵRI-γ as the published standard for comparison (Fig. 1B, first lane) (18, 25, 31). Immunoblotting experiments showed that the protein pattern between 40 and 60 kDa obtained with single FcϵRIα-chains (Fig. 1B, second and third lanes) is comparable with the pattern in α- and γ-chain cotransfected cells (Fig. 1B, first lane). In the absence of FcϵRI-γ, endo-α seems to be expressed predominantly near ∼46 kDa; based on the literature this is most likely the ER glycosylated form of the protein (ER form; Fig. 1B, second lane) (19, 24). We detected some unglycosylated protein backbone at ∼34 kDa, probably because of incomplete insertion into the ER. Interestingly, some higher molecular weight forms, most likely Golgi-modified protein (Golgi form; Fig. 1B, second lane), were also detected (19, 24, 31). This was not expected from the literature and indicates that a small amount of endo-α by itself can exit the ER (Fig. 1B, second lane). Exchange of the endogenous signal peptide with the H2-Kb signal peptide (Kb-α) dramatically enhanced the amounts of potentially Golgi-modified protein despite the absence of FcϵRI-γ (Fig. 1B, third lane). Transfection with an FcϵRI-α construct lacking a signal peptide resulted in the expression of a 30–34-kDa protein corresponding to the unglycosylated protein backbone (Fig. 1B, fourth lane). These results suggested that the signal peptide is involved in the control of ER exit and the amount of FcϵRI α-chain that traffics to the Golgi in the absence of FcϵRI γ-chains.

FIGURE 1.

Properly folded FcϵRI-α reaches the Golgi in the absence of FcϵRI-γ. A, signal peptide (SP) sequences of FcϵRI-α (NCBI RefSeq NP_001992.1) and mouse major histocompatibility complex class I H2-Kb (NCBI RefSeq NP001001892.2) are depicted. The stretch of hydrophobic amino acids representing the predicted transmembrane region of the signal peptide is underlined. The construct containing the wild type FcϵRI-α chain with its endogenous signal peptide is referred to as endo-α, and the chimeric construct where the endogenous signal peptide was swapped for the signal peptide of H2-Kb is referred to as Kb-α. B, FcϵRI α-chain shows a protein pattern characteristic for ER- and Golgi-modified forms in the absence of γ-chain. 293T cells were transfected with indicated HA-tagged α-chain constructs or cotransfected with γ-chain as control (first lane 1). Smaller quantities of α-chain from endo-α transfected cells reached the Golgi compared with Kb-α transfected cells (second and third lanes). A construct without signal peptide (no SP) did not enter the ER (fourth lane). Immunoblot analysis was performed under nonreducing conditions with the anti-HA antibody 3F10 (upper blot). The blot was stripped and reprobed with a polyclonal anti-γ-chain reagent (lower blot). C, glycosylation study performed on the FcϵRI α-chain after immunoprecipitation with IgE. FcϵRI α-chain (first, fourth, and seventh lanes) is compared for its susceptibility to EndoH (second, fifth, and eighth lanes) or PNGase F (third, sixth, and ninth lanes) digestion. D, visualization of FcϵRI-γ independent trafficking to the Golgi. Immunofluorescence staining of MelJuso cells transfected with Kb-α. The FcϵRI α-chain was detected with the polyclonal rabbit serum 997 and anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 568 (left images, shown in red). The Golgi was visualized with anti-GM130 followed by anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 (middle image, shown in green). The merged images are depicted in the right picture. E, molecular characteristics of α-chain from MelJuso cells transfected with Kb-α. Immunoprecipitation was performed with IgE; IgG was used to control for specificity of IgE binding. F, RT-PCR analysis confirmed lack of γ-chain expression in 239T, HeLa, and MelJuso cells. cDNA from human tonsil tissue was used as positive control (CTRL).

TABLE 1.

Summary of constructs used in this study

| Construct name | Description |

|---|---|

| Endo-α | Human FcϵRI α-chain with endogenous signal peptide |

| Kb-α | Human FcϵRI α-chain with signal peptide of murine major histocompatibility complex class I H2-Kb |

| Endo-αtail-minus | Truncation mutant of endo-α lacking the cytosolic tail of the α-chain |

| Kb-αtail-minus | Truncation mutant of Kb-α lacking the cytosolic tail of the α-chain |

| Kb-α D/N | Transmembrane mutant of Kb-α; the negatively charged aspartic acid in the transmembrane region was exchanged to the neutral asparagine |

| Endo-αE/A | Signal peptide mutant; the negatively charged glutamic acid at position 6 was exchanged to the neutral alanine |

| Endo-αE/K | Signal peptide mutant; the negatively charged glutamic acid at position 6 was exchanged to the positively charged lysine |

We next confirmed that the observed molecular weight changes of the single-chain FcϵRI-α resulted from post-translational glycosylation because of receptor trafficking from ER to Golgi and not from polyubiquitination during targeting for proteasomal degradation. Thus, we immunoprecipitated FcϵRI α-chain with IgE to select for properly folded protein and examined the extent of N-glycosylation by immunoblotting. Endo-α in the presence of FcϵRI-γ was used as a control (Fig. 1C, left panel). The ER form of FcϵRI-α was sensitive to EndoH digestion as evidenced by a drop in the molecular weight of the 46-kDa ER form to the protein backbone (34 kDa; Fig. 1C, compare first and second lanes). In the presence of FcϵRI-γ, a large amount of FcϵRI-α remained EndoH-resistant because of glycosylation patterns acquired in the Golgi (Fig. 1C, second lane). Deglycosylation of FcϵRI-α precipitated from endo-α or Kb-α transfectants with EndoH and PNGase F yielded a comparable protein pattern to that of endo-α in the presence of FcϵRI-γ (Fig. 1C, compare left immunoblot with middle and right immunoblots). In line with our observations in whole cell lysates (Fig. 1B), the amount of EndoH-insensitive protein varied depending on the nature of the signal peptide. The Golgi form precipitated from endo-α and Kb-α transfectants remained sensitive to PNGase F (Fig. 1C, third, sixth, and ninth lanes). Therefore, we concluded that the single-chain isoform of FcϵRI was properly glycosylated in the Golgi. Sensitivity to PNGase F digestion also excluded that single FcϵRI α-chain was simply aggregated or ubiquitinated protein and targeted for degradation.

We next visualized the ER exit of the single FcϵRI α-chain. We transiently transfected MelJuso cells with Kb-α and detected the α-chain with the polyclonal serum 997 (Fig. 1D, left panel). Immunofluorescence double staining with the Golgi marker GM130 (Fig. 1D, middle panel) showed a significant amount of FcϵRI α-chain in a Golgi compartment in the absence of FcϵRI-γ (Fig. 1D, overlay, right panel). Immunoprecipitation with IgE confirmed that the α-chain was properly modified in the Golgi in these cells (Fig. 1E). We confirmed by RT-PCR and immunoblot that neither 293T, HeLa, nor MelJuso express FcϵRI-γ (Fig. 1F and data not shown). In summary, this set of data demonstrated that the FcϵRI α-chain by itself can exit the ER and traffics to the Golgi where N-linked glycans are modified in the absence of FcϵRI-γ transcripts.

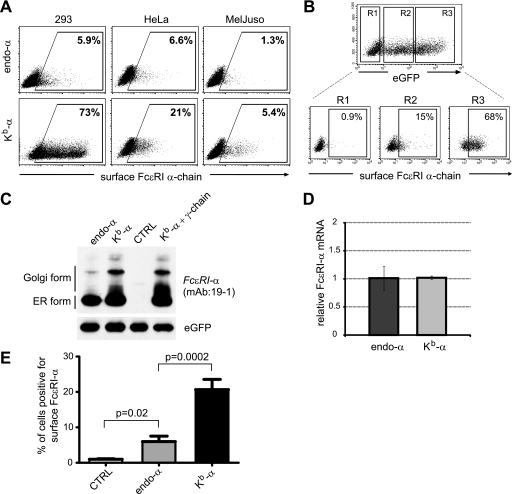

Trafficking of Single FcϵRI α-Chain to the Cell Surface Depends on the Signal Peptide

We next investigated whether FcϵRI-α can reach the cell surface in the absence of FcϵRI-γ. FACS analysis for surface expression of endo-α and Kb-α was performed in three different cell lines (Fig. 2A). Regardless of the cell line, both α-chain constructs reached the cell surface without FcϵRI-γ. The extent of surface expression varied with the transfection efficiency as well as the cell line (Fig. 2A). Importantly, we saw significant differences in surface expression levels depending on the nature of the signal peptide. Based on these observations, we speculated that efficiency of signal peptide processing is involved in the control of FcϵRI-α ER exit and subsequent transport to the cell surface.

FIGURE 2.

Cell surface expression of FcϵRI-α is regulated by its signal peptide. A, 293T, HeLa, and MelJuso cells were transfected with endo-α or Kb-α in vector pcDNA3.1 in the absence of the γ-chain. Cell surface expression of the α-chain was determined by flow cytometry. The gate depicting percentages of cells expressing α-chain at their cell surface was set accordingly to empty vector transfectants. B, eGFP expression correlates with surface expression of FcϵRI-α. 293T cells were transfected with Kb-α in pIRES2-eGFP. In the upper FACS dot plot eGFP expression is depicted. Three different regions were set corresponding to eGFPnegative (R1), eGFPlow (R2), and eGFPhigh (R3) cells. In the lower dot plots, α-chain expression at the cell surface was analyzed separately for these three different regions. C, 293T cells were transfected with endo-α and Kb-α constructs in pIRES2-eGFP. Empty vector transfected cells (CTRL) or cells cotransfected with Kb-α plus γ-chains were used as controls. The cells expressing equal intensities of eGFP were FACS-sorted, and cell lysates were analyzed for the protein characteristics of FcϵRI-α by immunoblotting with the mAb 19-1. Detection of eGFP with a polyclonal anti-GFP serum was used as a loading control. D, FcϵRI-α mRNA of cells that were FACS-sorted for equal levels of eGFP expression was determined by quantitative RT-PCR. E, the H2-Kb signal peptide drives surface expression of FcϵRI-α more efficiently than the endogenous signal peptide. Endo-α and Kb-α transfectants were gated based on equal eGFP expression and analyzed for surface α-chain. Empty pIRES2-eGFP vector transfected cells (CTRL) were used as control. The bar diagram represents the means ± S.E. of seven independent experiments.

To exclude that the differences in cell surface transport were influenced by different transfection efficiencies of the constructs, we next expressed endo-α and Kb-α in a bicistronic IRES-eGFP vector system. This system allowed us to use eGFP as a surrogate marker for protein expression levels and to set gates for FACS analysis and sorting. We found a strong correlation between eGFP expression levels and surface expression of FcϵRI-α (Fig. 2B). The cells were analyzed after setting three different analysis regions: eGFP-negative cells (Fig. 2B, upper plot), low eGFP-expressing cells (eGPFlow), and high eGFP-expressing cells (eGFPhigh). eGFPhigh cells expressed significantly more FcϵRI-α at the cell surface than eGPFlow cells (i.e. 68% versus 15%, respectively).

To analyze cells with equal transfection efficiencies, we next sorted endo-α and Kb-α transfected cells based on equal levels of eGFP expression and analyzed the protein characteristics of the FcϵRI α-chain by immunoblotting with the mAb 19-1 (Fig. 2C). This reagent reacts only with the properly folded IgE-binding FcϵRI α-chain (25). We confirmed that Kb-α transfectants contained significantly higher levels of Golgi-modified protein than endo-α transfectants (Fig. 2C). To control for the accuracy of the cell sorting, eGFP levels were determined (Fig. 2C). As an additional control we sorted cells with equal levels of eGFP and showed that those cells also expressed equal levels of FcϵRI-α mRNA by quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 2D). We next studied surface expression efficiency of the single FcϵRI α-chain in the bicistronic expression system. 293T cells were transiently transfected with endo-α, Kb-α, or the empty pIRES-eGFP vector as a control. Cells expressing equal levels of eGFP were gated and analyzed for cell surface expression of FcϵRI-α (Fig. 2E). Cells transfected with the endo-α construct showed low but significant surface expression levels compared with cells transfected with empty vector (6.0 ± 1.5% versus 1.0 ± 0.2%, respectively; means ± S.E., n = 7). Consistent with the more effective ER-to-Golgi transport (Fig. 2C), Kb-α transfected cells showed a 3.45-fold increase in expression when compared with endo-α transfectants (20.7 ± 2.9% versus 6.0 ± 1.5%, respectively; means ± S.E., n = 7; Fig. 2E).

Because surface expression of FcϵRI-α was substantially higher using constructs with the H2-Kb signal peptide (Fig. 2E), it is fair to conclude that these findings argue for a strong retention of properly folded FcϵRI α-chain in the ER by its endogenous signal peptide and imply that this signal peptide is a control module to prevent surface display of a single-chain isoform of FcϵRI.

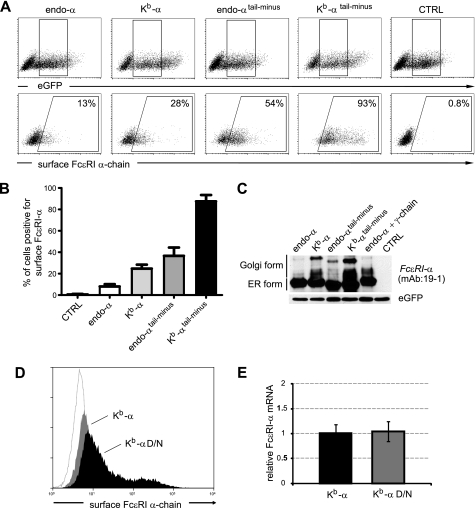

The Signal Peptide Controls Surface Expression of FcϵRI-α in the Absence of Cytosolic ER Retention Signals

ER retention/retrieval by dilysine motifs in the cytosolic tail of FcϵRI-α has been proposed as a key regulatory mechanism to prevent ER exit in the absence of the FcϵRI-γ chain (15, 16). Thus, we generated cytosolic tail truncations of endo-α and Kb-α to dissect the contributions of the signal peptide from the ER retention signals of the cytosolic tail of the α-chain.

Endo-α and Kb-α constructs that lack their cytosolic tails were generated by introducing stop codons following the transmembrane domain of FcϵRI-α at position serine199. These constructs are referred to as endo-αtail-minus and Kb-αtail-minus. The full-length and tail-minus constructs were transiently transfected into 239T cells. Using bicistronic expression of eGFP as a marker, a gate was set for the analysis of cells with comparable transfection efficiencies (Fig. 3A, upper panel). Both the endo-αtail-minus and Kb-αtail-minus reached the cell surface more efficiently than the full-length constructs (Fig. 3, A and B). Importantly, Kb-αtail-minus was exported far more efficiently than endo-αtail-minus (88 ± 12% versus 37 ± 16%, respectively; mean ± S.D., n = 4; Fig. 3B). Additionally, we sorted transfected cells based on their eGFP expression and performed immunoblot analysis with the mAb 19-1 (Fig. 3C). We detected, again, more Golgi form of FcϵRI-α in cells transfected with Kb-α than endo-α (Fig. 3C, first and second lanes). Golgi-modified FcϵRI α-chains were also more abundant in cells transfected with Kb-αtail-minus than endo-αtail-minus (Fig. 3C, third and fourth lanes).

FIGURE 3.

The signal peptide regulates cell surface expression of the FcϵRI α-chain independently of ER retention signals in the cytosolic tail. A, 293T cells were transfected with constructs lacking the cytosolic tail of the α-chain (i.e. endo-αtail-minus and Kb-αtail-minus) or with the full-length constructs, endo-α and Kb-α, in pIRES2-eGFP. Transfected cells expressing equal levels of eGFP were gated (upper dot plots) and analyzed for α-chain at the cell surface (lower dot plots). Empty vector transfected cells were used as control (CTRL). B, quantification (means ± S.E.) of cell surface expression of 4 independent experiments as shown in A. C, cells expressing equal levels of eGFP were FACS-sorted and cell lysates were analyzed for protein characteristics of FcϵRI-α by immunoblotting with mAb 19-1. Detection of eGFP was used as loading control. D, an Asp → Asn mutation in the transmembrane domain increases surface expression of FcϵRI α-chain. HeLa cells were transiently transfected with Kb-α or the Asp → Asn transmembrane mutant (i.e. Kb-α D/N). FACS histogram overlay depicts surface α-chain expression. Kb-α, filled, gray histogram; Kb-α D/N, striped, black histogram; empty vector, light gray line. E, relative FcϵRI-α mRNA levels of Kb-α and Kb-α D/N were determined by real time PCR. The values were determined in triplicate and normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase expression. Representative data of three independent experiments are shown in D and E.

We also investigated whether the modification of the transmembrane ER retention signal Asp192 (15) would have an effect on surface trafficking of Kb-α and generated a Kb-αD/N mutant. The removal of the transmembrane ER retention signal resulted in more efficient surface expression of Kb-αD/N versus Kb-α (Fig. 3D) at equal mRNA expression levels (Fig. 3E).

In summary, we showed that a single α-chain isoform of FcϵRI reached the cell surface alone. The Kb-signal peptide chimeras trafficked more efficiently to the cell surface even in the absence of cytosolic ER retention motifs, indicating that the Kb-signal peptide does not simply override ER retention. This set of data suggests that the signal peptide provides an additional regulatory element that controls FcϵRI α-chain trafficking in a concerted way with recently described ER retention signals.

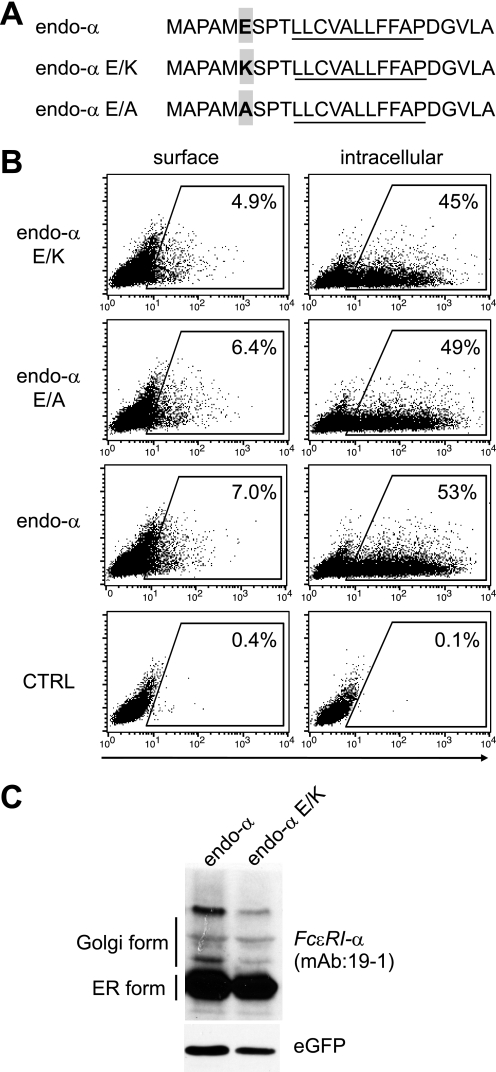

Point Mutations in the Endogenous Signal Peptide Argue against Interference with Signal Particle Recognition as a Regulatory Mechanism for Cell Surface Transport

Signal peptides do not have a well defined consensus sequence; however, one common feature is a positively charged residue preceding the hydrophobic stretch. This N-terminal part of the signal peptide sequence is critical for recognition of nascent proteins by the signal recognition particle to initiate translocation across the ER membrane (32–34). The endogenous signal peptide of the FcϵRI α-chain does not contain this positively charged amino acid. Instead, a negatively charged glutamic acid is found in position 6 (Figs. 1A and 4A). The H2-Kb signal peptide is devoid of any charged amino acids (Figs. 1A and 4A). To investigate whether the introduction of a positively charged amino acid or removal of the negative charged amino acid in the endogenous signal peptide of the α-chain could modulate intracellular trafficking, we generated point mutants where the glutamic acid (E) at position 6 was exchanged to lysine (K) or alanine (A). The generated constructs were termed endo-αE/K and endo-αE/A. Neither endo-αE/K nor endo-αE/A was able to reach the cell surface more efficiently than endo-α (Fig. 4B). We also compared the ER to Golgi transport and found no significant difference between endo-α and the mutants (Fig. 4C and data not shown). Thus, mutating the endogenous FcϵRI signal peptide to match the signal peptide consensus sequence or to resemble that of H2-Kb did not affect trafficking. These results argue for signal peptide cleavage rather than ER insertion as the mechanism that regulates ER exit of the FcϵRI α-chain in the absence of the FcϵRI γ-chains.

FIGURE 4.

Point mutations in the endogenous signal peptide do not change cell surface transport of FcϵRI α-chain. A, scheme of introduced point mutations at position 6 of the endogenous signal peptide. B, 293T cells were transfected with endo-α, endo-α E/K, endo-α E/A, or empty vector. The data are representative of three independent experiments. C, cells expressing equal intensities of eGFP were FACS-sorted. The cell lysates were analyzed for the protein characteristics of FcϵRI-α by immunoblotting with mAb 19-1. Detection of eGFP was used as loading control.

Single FcϵRI α-Chain Is Stabilized upon Monovalent Interaction with IgE

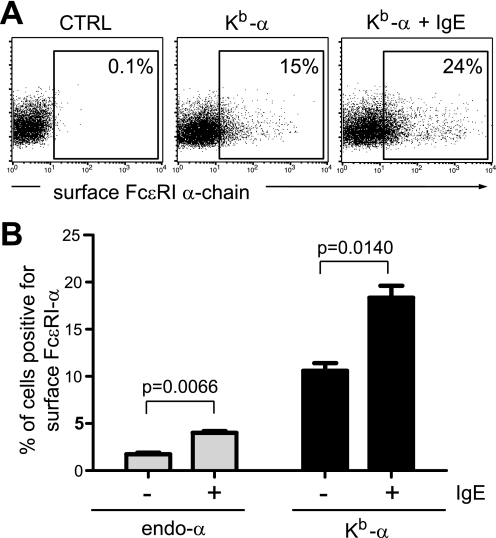

Multimeric isoforms of FcϵRI are stabilized at the cell surface by monovalent interactions with IgE (35). We next wanted to investigate whether the single-chain isoform of FcϵRI also shares this key feature of the multimeric FcϵRI complexes. We cultured endo-α and Kb-α transfectants with or without IgE for 16 h. Interaction with IgE stabilized the single FcϵRI α-chain at the cell surface as measured by flow cytometry (Fig. 5). The degree of stabilization was comparable between both constructs (2.3-fold versus 1.7-fold; Fig. 5B). These data showed that single FcϵRI-α interacts with and is stabilized by its natural ligand IgE at the cell surface like multimeric receptor isoforms.

FIGURE 5.

IgE-induced stabilization of FcϵRI at the cell surface does not require FcϵRI-γ-chains. A, 293T cells were transfected with Kb-α in pIRES2-eGFP, incubated with 200 ng/ml IgE for 18h, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Transfected cells were identified by eGFP expression and gated to determine cell surface expression of the α-chain. B, IgE stabilization of the single FcϵRI α-chain is signal peptide-independent. 293T cells were transfected with endo-α or Kb-α in pIRES2-eGFP, incubated with 200 ng/ml IgE for 18 h before analysis by flow cytometry. The data are presented as the means ± S.E. of three independent experiments. CTRL, control.

Single FcϵRI α-Chain Internalizes after Cross-linking

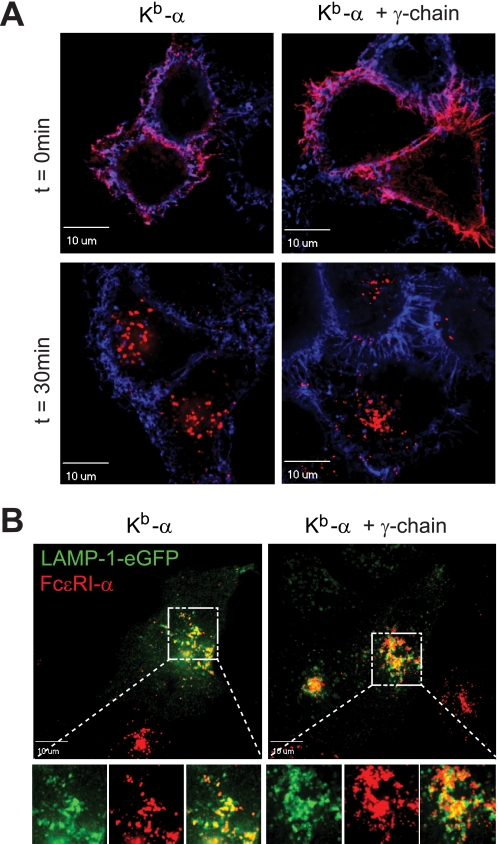

Cross-linking of multimeric FcϵRI isoforms (i.e. αγ2 and αβγ2) induces signaling via the ITAM motifs in the γ- and β-chains as well as the internalization of receptor complexes from the cell surface (7, 36). Next, we explored whether cross-linking of the single FcϵRI α-chain also induces internalization from the cell surface. We monitored α-chain internalization in HeLa cells. First, FcϵRI was loaded with the α-chain-specific antibody CRA1 at the cell surface. This incubation step does not result in receptor internalization (data not shown). Next, internalization of FcϵRI-α was induced by cross-linking with a fluorescently labeled secondary antibody. Irrespective of the presence of the γ-chain, we found FcϵRI α-chain inside the cell within 30 min (Fig. 6A). HeLa cells stably transfected with a LAMP-1-eGFP reporter were used to study whether the single-chain receptor isoform traffics into endo/lysosomal compartments. We found that a single FcϵRI α-chain shuttles to a lysosomal compartment as characterized by LAMP-1 expression comparable with multimeric FcϵRI containing the common γ-chain (Fig. 6B). This indicates that the FcϵRI signaling subunits are not essential for internalization and intracellular trafficking after FcϵRI cross-linking.

FIGURE 6.

Single FcϵRI α-chain internalizes after receptor cross-linking. A, Kb-α was transiently transfected into HeLa cells (left images) or into HeLa cells stably expressing the FcϵRI γ-chain (right images). For FcϵRI-α cross-linking, the cells were incubated with the mouse anti-human FcϵRI-α antibody, CRAI, which was next cross-linked with an anti-mouse Alexa-Fluor 568-F(ab′)2 fragment (shown in red). The cells were incubated for 30 min at 37 °C (lower panels). For time point (t) = 0, the cells were fixed before cross-linking with anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 568-F(ab′)2 (upper panels). Cell surface membranes were visualized using Alexa Fluor 647-labeled wheat germ agglutinin (shown in blue). Confocal micrographs are presented as overlays. Representative experiment is shown (n = 3). B, FcϵRI α-chain traffics into LAMP-1 positive lysosomal compartments independently of the presence of FcϵRI-γ. HeLa cells expressing LAMP-1-eGFP (shown in green) were transfected with Kb-α (shown in red). Receptor cross-linking and internalization was performed as described above. The left panel shows cells transfected with Kb-α alone. The right panel shows cells that co-express FcϵRI α- and γ-chains. The bottom panel depicts higher magnifications of the lysosomal regions of the images shown in the upper panel. The bottom panel shows single channel images for LAMP-eGFP in green (left), FcϵRI-α in red (middle), and the merged image (right). The cells were analyzed 90 min after cross-linking.

DISCUSSION

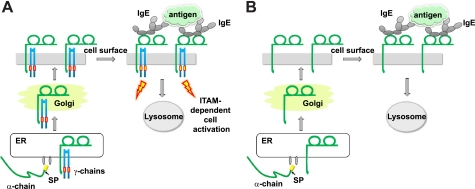

FcϵRI is an activating immune receptor complex that must accomplish the following tasks: assembling properly in the ER, reaching the cell surface, binding IgE, and inducing ITAM-based cell activation as well as internalization of receptor complexes upon antigen-mediated receptor cross-linking (schematic in Fig. 7A).

FIGURE 7.

Schematic of intracellular trafficking of FcϵRI and receptor-mediated cell activation. A, the subunits of multimeric FcϵRI complexes assemble in the ER, traffic to the Golgi and reach the cell surface. Antigen-induced cross-linking of IgE-loaded FcϵRI complexes induces ITAM-mediated cell activation and internalization of the receptor. Cross-linked FcϵRI shuttles antigen-IgE immune complexes to lysosomal compartments. B, single FcϵRI α-chain can exit the ER, traffic to the Golgi and reach the cell surface by itself. Trafficking of this single receptor isoform is tightly regulated by the signal peptide. Antigen-induced cross-linking of IgE-loaded single FcϵRI α-chain induces receptor internalization in the absence of ITAM-mediated cell activation. Like multimeric FcϵRI complexes, cross-linked single FcϵRI α-chain isoforms reach lysosomal compartments.

The fidelity of intracellular trafficking of FcϵRI complexes has so far been considered a function of cytosolic and transmembrane ER retention signals in the FcϵRI α-chain that are masked by association with the other receptor subunits. Here we demonstrated that the signal peptide of FcϵRI-α contains an additional regulatory element that contributes to the retention of the α-chain in the ER. We found that human FcϵRI-α inefficiently reaches the cell surface by itself and that a swap of the endogenous signal peptide for that of H2-Kb allows for significantly more efficient surface expression.

We show that the single FcϵRI α-chain binds IgE at the cell surface and stabilizes upon IgE binding. This observation supports an earlier report by Kubota et al. (35) describing that surface stabilization of FcϵRI is a function of the stalk region of the α-chain. This conclusion was derived from the analysis of chimeric α-chains in the presence of FcϵRI γ-chains. Our experiments show unambiguously that the IgE-mediated surface stabilization affects wild type FcϵRI-α as a single-chain receptor. We further demonstrate that single FcϵRI α-chain is efficiently targeted into lysosomal compartments after receptor cross-linking. Thus, the single-chain isoform of the receptor could act as an IgE-receptor, which reacts to serum IgE levels and shuttles antigen into antigen presentation compartments. Removal of the cytosolic ER retention signals as well as mutating the transmembrane ER retention signal suggest that the signal peptide regulates ER retention in a concerted fashion with formerly described ER retention motifs (15, 18). The fact that the regulatory influence of the signal peptide could still be observed when other ER retention signals were removed argues against a simple overexpression artifact.

To our knowledge, this is the first report showing that a signal peptide can regulate the surface expression of an Fc receptor. However, several reports in the literature have shown that signal peptides can function as more than just ER targeting sequences (14). A polymorphism in the luteinizing hormone receptor protein improves its signal peptide function and increases protein expression. The consequences of the higher expression levels of this luteinizing hormone receptor protein are unfavorable, and consequently, this polymorphism serves as a predictor for adverse outcome in breast cancer patients (37). Along this line, genetic polymorphism in the signal peptide of FcϵRI-α could influence IgE receptor expression levels and allergy. Whether such a polymorphism in the FcϵRI-α signal peptide indeed exists in humans needs to be addressed in future studies.

The ER assembly of FcϵRI complexes is regulated more tightly than that of other activating immune receptor complexes (19). Although other receptor complexes assemble in consecutive steps (4, 5, 20, 30), assembly of FcϵRI complexes occurs strictly cotranslationally. It is also important to keep in mind that FcϵRI-γ is a signaling subunit shared by multiple activating immune receptors. Therefore, several receptor complexes compete for this protein in the ER. Competition for limiting amounts of FcϵRI-γ has been demonstrated in vivo. The absence of FcϵRI α-chain enhances FcγRIII-dependent mast cell degranulation and anaphylaxis (38). FcϵRI seems to be at a competitive disadvantage because it needs to fulfill its cotranslational assembly requirement. Therefore, the assembly machinery has to assure both temporal and spatial coordination of subunit translation. In this context, ER retention of FcϵRI-α by the signal peptide could facilitate this cotranslational event. One possibility for signal peptides to modulate ER retention is by regulating the activity of type I signal peptidase (39). Because signal peptide cleavage is a cotranslational event, a slow cleavage rate might impede folding of FcϵRI-α in a way that provides more time for assembly. Given that we were not successful in destroying the regulatory property of the endogenous signal peptide through a targeted mutation, however, we cannot formally rule out that the signal peptide controls α-chain trafficking via regulating its recognition and translocation into the ER.

We suggest that this additional regulatory sequence element is important to prevent the formation of an FcϵRI γ-chain-free IgE receptor pool at the cell surface (schematic in Fig. 7B). In human antigen presenting cells, such as dendritic cells and macrophages, intracellular accumulation of FcϵRI-α is frequently found (21, 39–41). This is probably because FcϵRI-α alone folds properly and forms IgE-binding sites (9) and is therefore not efficiently recognized by the ER-associated degradation machinery. A slow rate of signal peptide processing might however help the ER-associated degradation system to recognize some of this FcϵRI-α and target it for degradation. Although FcϵRI-α is mainly restricted to the ER in the absence of the γ-chain, we show that some properly folded protein reaches the cell surface and forms a signaling-deficient IgE receptor isoform. This receptor pool lacks ITAM-based signaling modules yet retains its ability to bind IgE and to endocytose upon receptor activation. This single-chain IgE-receptor also reaches lysosomal compartments like tetrameric and trimeric FcϵRI (36).3 FcϵRI shuttles IgE-antigen complexes into lysosomal compartments for antigen presentation, most likely to facilitate allergen presentation via major histocompatibility complex class II (36, 42). We show here that this intracellular trafficking is not dependent on signaling subunits, which carry ITAM motifs in their cytosolic tails. We therefore conclude that signals via ITAMs in FcϵRI-β or FcϵRI-γ are dispensable for intracellular trafficking of IgE-antigen complexes to lysosomal compartments.

In the context of allergy, this FcϵRI-γ and ITAM-free receptor appears attractive. Such an IgE receptor could remove IgE or IgE-allergen complexes in an immunologically silent form, because cross-linking would not initiate cell activation via ITAMs (Fig. 7B). IgE-FcϵRI-mediated cell activation during allergy is, however, not the physiological function of IgE-mediated response. This pathway is highly active during helminth parasite infections and critical for the development of protective immunity. In this context, expression of an IgE-receptor that fails to signal is undesirable, because it could compromise the development of protective immunity. In summary, based on our findings, we propose that the endogenous signal peptide of FcϵRI-α represents a critical control element preventing unwanted expression of a signaling-deficient IgE receptor isoform.

Acknowledgments

We thank Alexandra Baker for excellent technical assistance. We also thank Dr. Bonny Dickinson for advice and helpful criticism on the manuscript and Dr. Naomi Wernik for critically reading the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants DK081256 (to B. P.) and R56AI075037 and R01AI075037 (to E. F.). This work was also supported by a Research Scholar Award from the American Gastroenterological Association (to E. F.).

B. Platzer, manuscript in preparation.

- FcϵRI

- high affinity Fc receptor for IgE

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- LAMP-1

- lysosomal-associated membrane protein-1

- ITAM

- immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif

- HA tag

- hemagglutinin epitope tag

- mAb

- monoclonal antibody

- eGFP

- enhanced green fluorescent protein

- endo-α

- endogenous α-chain

- EndoH

- endoglycosidase H

- PNGase F

- peptide n-glycosidase F

- FACS

- fluorescence-activated cell sorter

- RT

- reverse transcription.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abramson J., Pecht I. (2007) Immunol. Rev. 217, 231–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gould H. J., Sutton B. J. (2008) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 205–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kraft S., Kinet J. P. (2007) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7, 365–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Call M. E., Wucherpfennig K. W. (2005) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 23, 101–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Call M. E., Wucherpfennig K. W. (2007) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7, 841–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schamel W. W., Reth M. (2008) Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 640, 64–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kinet J. P., Jouvin M. H., Paolini R., Numerof R., Scharenberg A. (1996) Eur. Respir. J. 9, 166s–118s [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turner H., Kinet J. P. (1999) Nature 402, B24–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hakimi J., Seals C., Kondas J. A., Pettine L., Danho W., Kochan J. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265, 22079–22081 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kinet J. P. (1999) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 17, 931–972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meusser B., Hirsch C., Jarosch E., Sommer T. (2005) Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 766–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakatsukasa K., Brodsky J. L. (2008) Traffic 9, 861–870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vembar S. S., Brodsky J. L. (2008) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 944–957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anelli T., Sitia R. (2008) EMBO J. 27, 315–327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cauvi D. M., Tian X., Von Loehneysen K., Robertson M. W. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 10448–10460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Letourneur F., Hennecke S., Demolliere C., Cosson P. (1995) J. Cell Biol. 129, 971–978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hartman M. L., Lin S. Y., Jouvin M. H., Kinet J. P. (2008) Mol. Immunol. 45, 2307–2311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Albrecht B., Woisetschlager M., Robertson M. W. (2000) J. Immunol. 165, 5686–5694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fiebiger E., Tortorella D., Jouvin M. H., Kinet J. P., Ploegh H. L. (2005) J. Exp. Med. 201, 267–277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Call M. E., Wucherpfennig K. W. (2004) Mol. Immunol. 40, 1295–1305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Novak N., Tepel C., Koch S., Brix K., Bieber T., Kraft S. (2003) The Journal of clinical investigation 111, 1047–1056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benado A., Nasagi-Atiya Y., Sagi-Eisenberg R. (2009) Immunobiology 214, 403–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Castro-Fernandez C., Maya-Nunez G., Conn P. M. (2005) Endocr. Rev. 26, 479–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donnadieu E., Jouvin M. H., Rana S., Moffatt M. F., Mockford E. H., Cookson W. O., Kinet J. P. (2003) Immunity 18, 665–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maurer D., Fiebiger E., Reininger B., Wolff-Winiski B., Jouvin M. H., Kilgus O., Kinet J. P., Stingl G. (1994) J. Exp. Med. 179, 745–750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horton R. M., Ho S. N., Pullen J. K., Hunt H. D., Cai Z., Pease L. R. (1993) Methods Enzymol. 217, 270–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maurer D., Fiebiger E., Ebner C., Reininger B., Fischer G. F., Wichlas S., Jouvin M. H., Schmitt-Egenolf M., Kraft D., Kinet J. P., Stingl G. (1996) J. Immunol. 157, 607–613 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fiebiger E., Story C., Ploegh H. L., Tortorella D. (2002) EMBO J. 21, 1041–1053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benaroch P., Yilla M., Raposo G., Ito K., Miwa K., Geuze H. J., Ploegh H. L. (1995) EMBO J. 14, 37–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feng J., Garrity D., Call M. E., Moffett H., Wucherpfennig K. W. (2005) Immunity 22, 427–438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Donnadieu E., Jouvin M. H., Kinet J. P. (2000) Immunity 12, 515–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Egea P. F., Stroud R. M., Walter P. (2005) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 15, 213–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hegde R. S., Bernstein H. D. (2006) Trends Biochem. Sci. 31, 563–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tuteja R. (2005) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 441, 107–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kubota T., Mukai K., Minegishi Y., Karasuyama H. (2006) J. Immunol. 176, 7008–7014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fattakhova G. V., Masilamani M., Narayanan S., Borrego F., Gilfillan A. M., Metcalfe D. D., Coligan J. E. (2009) Mol. Immunol. 46, 793–802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Piersma D., Berns E. M., Verhoef-Post M., Uitterlinden A. G., Braakman I., Pols H. A., Themmen A. P. (2006) J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 91, 1470–1476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dombrowicz D., Flamand V., Miyajima I., Ravetch J. V., Galli S. J., Kinet J. P. (1997) The Journal of clinical investigation 99, 915–925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paetzel M., Karla A., Strynadka N. C., Dalbey R. E. (2002) Chem. Rev. 102, 4549–4580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Von Bubnoff D., Novak N., Kraft S., Bieber T. (2003) Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 28, 184–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wollenberg A., Kraft S., Oppel T., Bieber T. (2000) Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 25, 530–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maurer D., Ebner C., Reininger B., Fiebiger E., Kraft D., Kinet J. P., Stingl G. (1995) J. Immunol. 154, 6285–6290 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]