Abstract

Arrestins are multifunctional adaptor proteins best known for their role in regulating G protein-coupled receptor signaling. Arrestins also regulate other types of receptors, including the insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGF-1R), although the mechanism by which this occurs is not well understood. In Caenorhabditis elegans, the IGF-1R ortholog DAF-2 regulates dauer formation, stress resistance, metabolism, and lifespan through a conserved signaling cascade. To further elucidate the role of arrestin in IGF-1R signaling, we employed an in vivo approach to investigate the role of ARR-1, the sole arrestin ortholog in C. elegans, on longevity. Here, we report that ARR-1 functions to positively regulate DAF-2 signaling in C. elegans. arr-1 mutant animals exhibit increased longevity and enhanced nuclear localization of DAF-16, an indication of decreased DAF-2 signaling, whereas animals overexpressing ARR-1 have decreased longevity. Genetic and biochemical analysis reveal that ARR-1 functions to regulate DAF-2 signaling via direct interaction with MPZ-1, a multi-PDZ domain-containing protein, via a C-terminal PDZ binding domain in ARR-1. Interestingly, ARR-1 and MPZ-1 are found in a complex with the phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) ortholog DAF-18, which normally serves as a suppressor of DAF-2 signaling, suggesting that these three proteins work together to regulate DAF-2 signaling. Our results suggest that the ARR-1-MPZ-1-DAF-18 complex functions to regulate DAF-2 signaling in vivo and provide insight into a novel mechanism by which arrestin is able to regulate IGF-1R signaling and longevity.

Keywords: Adaptor Proteins, Aging, C. elegans, Insulin-like Growth Factor (IGF), Neurobiology, Phosphatidylinositol Signaling, Signal Transduction, PDZ, Arrestin

Introduction

The fundamental process of aging is regulated by a diverse number of genetic and environmental factors; however, one well established factor contributing to longevity is the insulin/IGF-1 (IIS)2 signaling pathway (1). Mutations that reduce IIS signaling have been demonstrated to extend lifespan in a wide range of organisms including Drosophila, Caenorhabditis elegans, mice, and humans (2, 3). For example, mutation of DAF-2, the sole insulin/IGF-1 receptor in C. elegans, doubles the normal lifespan of these animals (4, 5). The IIS signaling pathway in worms regulates longevity through a highly conserved set of components (6). Upon ligand binding, the DAF-2 receptor recruits and activates the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) homolog AGE-1, resulting in the production of phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate (7). This activates PDK-1, which in turn leads to activation of the serine/threonine protein kinases AKT-1, AKT-2, and SGK-1 (8–10). These kinases phosphorylate the forkhead transcription factor DAF-16 and prevent it from entering the nucleus, an event that represses the ability of DAF-16 to regulate the transcription of genes involved in longevity (11–13). DAF-2 signaling is negatively regulated by the lipid phosphatase DAF-18, the ortholog of the human tumor suppressor PTEN (14–16). DAF-18 catalyzes the dephosphorylation of phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate, thereby antagonizing AGE-1 and disrupting the activity of the downstream signaling cascade. This pathway is also negatively regulated by the protein phosphatase PP2A, which interacts with and dephosphorylates AKT-1 (17). Reduction of DAF-2 activity or any other proteins positively regulated by DAF-2 within the IIS pathway leads to an increase in longevity, whereas reduction of activity in proteins that antagonize DAF-2 signaling, like DAF-16 and DAF-18, suppress the longevity phenotypes of daf-2 and other long lived IIS mutant animals (18).

In addition to the conserved role of IIS signaling in aging, the mammalian IGF-1 pathway also plays a critical role in embryonic development, differentiation, and postnatal growth as well as in the transformation and growth of malignant cells (19, 20). Hence, characterization of the mechanisms that regulate IIS signaling is critical to better understand the development of cancer and other age-related diseases. Arrestins, a family of multifunctional adaptor proteins, have been demonstrated to play a role in the regulation of mammalian IGF-1 receptor signaling (21). Although traditionally associated with the termination of G protein-coupled receptor signaling, non-visual arrestins (arrestin2 and -3, also known as β-arrestin1 and -2) also bind to and promote the internalization of the IGF-1R, which enhances IGF-1-dependent ERK1/2 phosphorylation and mitogenic signaling (22). Arrestin2 also positively regulates IGF-1R signaling via activation of PI3K and AKT, although this appears to be independent of IGF-1R activity (23). Interestingly, arrestin2 has also been shown to negatively regulate IGF-1R by acting as an adaptor to recruit the E3 ubiquitin ligase Mdm2 to the receptor, resulting in ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of the IGF-1R (24). Taken together, arrestins appear to regulate IGF-1R signaling, although the underlying mechanisms and potential in vivo role are not fully understood.

To further elucidate the role of arrestin in IGF-1R signaling, we employed an in vivo approach to investigate the impact of ARR-1, the sole non-visual arrestin ortholog in C. elegans, on longevity. Using genetic, biochemical, and physiological analysis, we demonstrate that ARR-1 regulates lifespan within the IIS signaling pathway and that the ability of ARR-1 to promote DAF-2 signaling is dependent upon an interaction between ARR-1 and the multi-PDZ domain-containing protein, MPZ-1. We provide evidence that ARR-1 regulates DAF-2 signaling to control the phosphorylation and intracellular localization of DAF-16 and that ARR-1 and MPZ-1 form a protein complex with DAF-18. We propose that ARR-1 acts to negatively regulate DAF-18 and that MPZ-1 plays a dual role in the regulation of DAF-18, dependent upon its association with ARR-1. Our results suggest that the ARR-1-MPZ-1-DAF-18 complex functions to regulate DAF-2 signaling in vivo and provide insight into a novel mechanism by which arrestin is able to regulate IGF-1R signaling and longevity.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Strains

Worms were cultured using standard methods (25). The following strains were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center: wild-type N2 Bristol, RB660 arr-1(ok401) X, MT8190 lin-15(n765) X, CB1370 daf-2(e1370)III, DR1565 daf-2(m596)III, DR1574 daf-2(e1391)III, CB1375 daf-18(e1375) IV, CF1038 daf-16(mu86) I, and TJ356 Is[daf-16::gfp]. The daf-18(nr2037) strain was kindly provided by Dr. Michael J. Stern.

Plasmids and Transgenic Strains

Germline transformations were performed as described previously (26). Generation of ARR-1(OE) transgenic animals was performed as described previously (27). Briefly, ∼7.2 kb of arr-1 genomic sequence was amplified from cosmid F53H8.2 and subcloned into the PstI and XhoI sites of pBluescript II SK(+/−). The ARR-1(OE) construct was injected at 80 ng/μl with lin-15 DNA (50 ng/μl) as a co-injection marker into the gonads of lin-15(n765ts) animals. To generate arr-1(ok401) mutants overexpressing wild-type ARR-1, the ARR-1(OE) construct was injected at 80 ng/μl with lin-15 DNA (50 ng/μl) as a co-injection marker into the gonads of arr-1(ok401);lin-15(n765ts) animals. To generate arr-1(ok401) mutants overexpressing the PDZ binding-deficient ARR-1 mutant (L435A), the L435A mutation was introduced into the ARR-1(OE) construct by PCR site-directed mutagenesis and confirmed by DNA sequencing. The ARR-1-L435A construct was injected at 80 ng/μl with lin-15 DNA (50 ng/μl) as a co-injection marker into the gonads of arr-1(ok401);lin-15(n765ts) animals. Transgenic lines were identified by rescue of the lin-15 multivulva phenotype at 20 °C. To generate animals overexpressing MPZ-1-PDZ6·GFP, MPZ-1 PDZ domain 6 (residues 1218–1313) was amplified by PCR from cDNA yk1004e08 (provided by Dr. Yuji Kohara) and subcloned into the green fluorescent protein (GFP) vector pPD95.77, which contained 3 kb of 5′-untranslated region arr-1 genomic sequence to serve as an endogenous promoter. The MPZ-1-PDZ6·GFP construct was injected at 80 ng/μl with rRF4 rol-6 DNA (50 ng/μl) as a co-injection marker into the gonads of wild-type animals. Transgenic lines were identified by GFP and the roller phenotype. Multiple independent transgenic lines were established and analyzed.

Western Blot Analysis of Worm Lysates

Worms were harvested and washed in M9 buffer. Worm pellets were sonicated in an equal volume of sample buffer (100 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 5% β-mercaptoethanol, and 15% glycerol) and boiled for 10 min. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using purified rabbit anti-ARR-1 antibody.

RNAi Experiments

RNAi feeding experiments were conducted as described previously (28). RNAi constructs were made by inserting ∼1000-bp fragments of daf-2 cDNA (yk1349a08) or mpz-1 cDNA (yk1004e08) into the SalI and XhoI sites of pL4440. All constructs were confirmed by direct sequencing. HT115(DE3) bacteria were transformed with either the empty pL4440 vector or the vector containing the test RNAi constructs. Nematode growth media plates were supplemented with 1 mm isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside and 100 μg/ml ampicillin, kept at room temperature for 2–4 days to dry, and then seeded with double-stranded RNA-expressing bacteria that had been grown 6–8 h in LB with 100 μg/ml ampicillin. Seeded RNAi plates were induced overnight at 37 °C and stored at 4 °C if not used immediately.

Lifespan Analysis

Lifespan assays were performed at 20 °C, unless otherwise noted. L4 stage animals were transferred onto nematode growth media plates seeded with OP50 and examined every other day for 30 days for touch-provoked movement. Lifespan assays in the presence of 5-fluorodeoxyuridine (FUDR) were performed as described above except that plates contained 40 μm FUDR. For RNAi lifespan assays, worms were grown for two full generations on RNAi plates seeded with HT115(DE3) bacteria transformed with the test RNAi construct prior to the start of the assay. All assays were performed in triplicate. Animals that crawled off the plate were censored. SAS software was used for statistical analysis. p values were determined using a long rank test (Kaplan-Meier method).

GFP Localization

Strains expressing GFP-tagged proteins (daf-16::gfp(TJ356), arr-1(ok401);Is[daf-16::gfp], mpz-1 RNAi-treated Is[daf-16::gfp], and wild-type animals expressing MPZ-1-PDZ6·GFP) were maintained at 20 °C. Approximately 40 animals from each strain were mounted onto slides with levisomole in M9 buffer. The localization pattern of DAF-16·GFP was immediately examined using either a Nikon ECLIPSE E800 microscope and Image J software or confocal microscopy and MetaMorph software. Only non-saturating pictures with fixed exposure times were used to compare fluorescence.

Co-immunoprecipitation Assays

To generate a HA-tagged DAF-18 construct, full-length daf-18 was amplified from cDNA yk400b8 by PCR and subcloned into the HA-pcDNA vector at the XbaI and ApaI sites. To generate the FLAG-tagged MPZ-1 construct, PDZ domains 6–10 (residues 1217–2166) were amplified from cDNA yk31g8 and subcloned into the p3xFLAG-CMVTM-10 vector at the HindIII and NotI sites. To generate the ARR-1 constructs (wild type and L435A), full-length arr-1 was amplified from cDNA yk371g9 and inserted into the pcDNA vector at EcoRI and XhoI sites. The ARR-1-L435A mutation was introduced into the wild-type ARR-1 construct by standard PCR site-directed mutagenesis. All constructs were verified by DNA sequencing. All cDNAs were provided by Dr. Yuji Kohara.

COS-1 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 25 mm HEPES in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2 at 37 °C. COS-1 cells were transiently transfected with the indicated plasmids (pcDNA3-HA-DAF-18, pcDNA3- ARR-1, pcDNA3-ARR-1-L435A, p3xFLAG-CMV10-MPZ-1-PDZ6–10) using FuGENE 6 (Roche Applied Science) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Forty eight h after transfection, cells were lysed in 1 ml of ice-cold immunoprecipitation buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, and protease inhibitors (Roche Applied Science)) and cleared by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were incubated with 30 μl of either anti-HA agarose-conjugated beads (Sigma) or anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel (Sigma) for 1 h at 4 °C. Immunocomplexes were extensively washed with co-immunoprecipitation buffer, and samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis for DAF-18 (using 101P anti-HA antibody, Covance), MPZ-1 using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated M2 anti-FLAG (Sigma-Aldrich), and ARR-1 (using anti-ARR-1-specific antibody). Whole cell lysates were probed for expression levels of DAF-18 (using 101R anti-HA antibody, Covance), MPZ-1 (using M2 anti-FLAG antibody, Sigma-Aldrich), and ARR-1 (using anti-ARR-1-specific antibody). The anti-ARR-1 antibody was prepared as described previously (27). Mouse and rabbit horseradish-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Bio-Rad, and chemiluminescent detection (ECL) kits were from Pierce.

Glutathione S-Transferase (GST) Pulldown Assays

The MPZ-1-PDZ6 GST fusion construct was generated by subcloning MPZ-1-PDZ6 (residues 1217–1313) from cDNA yk1004e08 (amplified by PCR) into the EcoRI and XhoI sites of pGEX-4T2. The MPZ-1-PDZ6–10 GST fusion construct was generated by subcloning MPZ-1 PDZ domains 6–10 (residues 1217–2166) from cDNA yk371g8 (amplified by PCR) into the SmaI and NotI sites of pGEX-4T2. The ARR-1 maltose-binding protein (MBP) fusion protein was generated by subcloning residues 321–435 of ARR-1 from cDNA yk317g9 (amplified by PCR) into the BamHI and HindIII sites of pMAL-c2X. The MBP-ARR-1-L435A and MBP-ARR-1-TRUNC (residues 321–431) mutant fusion proteins were introduced into the MBP·ARR-1 construct by standard PCR site-directed mutagenesis and confirmed by DNA sequencing. BL21 cells transformed with GST or MBP fusion constructs were grown overnight at 37 °C, diluted 1:10, grown to an A600 ∼0.4–0.7 optical density, and then induced with 0.1 mm isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside for 3 h at 30 °C. Cells were harvested in cold lysis buffer (for GST fusion proteins, 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.2, 120 mm potassium acetate, 0.1 mm dithiothreitol, 0.1% Triton X-100, and protease inhibitors (Roche Applied Science), and for MBP fusion proteins, 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 200 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 10 mm β-mercaptoethanol, and protease inhibitors (Roche Applied Science)). Cells were briefly sonicated on ice, and lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. GST-containing lysates were incubated with glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads (Amersham Biosciences) for 1 h at 4 °C, washed and resuspended in GST binding buffer, and kept at 4 °C. MBP-containing lysates were incubated with amylose resin (New England Biolabs) for 1 h at 4 °C, and MBP fusion proteins were eluted with MBP lysis buffer plus 10 mm maltose. For binding experiments using purified proteins, 40 pmol of GST or GST·MPZ-1-PDZ6 fusion protein was incubated with 2 μg of purified MBP·ARR-1, MBP·ARR-1-L435A, or MBP·ARR-1-TRUNC fusion protein for 1 h. Samples were washed four times in binding buffer, and bound ARR-1 was eluted by boiling the beads in 2× sample buffer for 10 min. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using the anti-ARR-1-specific antibody, horseradish peroxidase-coupled goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Bio-Rad), and chemiluminescent detection using ECL (Pierce). For binding experiments using transfected cells, 100 pmol of GST or GST·MPZ-1-PDZ6–10 fusion protein was incubated with 150 μg of COS-1 lysates expressing either HA-tagged DAF-18 (full-length) or HA-tagged ARR-1 (full-length) for 1 h at 4 °C. The beads were washed four times in binding buffer, and bound ARR-1 or DAF-18 was eluted by boiling the beads in 2× sample buffer for 10 min. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using the 101R anti-HA antibody (Covance), horseradish peroxidase-coupled anti-mouse secondary antibody (Bio-Rad), and chemiluminescent detection using ECL (Pierce).

RESULTS

ARR-1 Regulates Lifespan in C. elegans

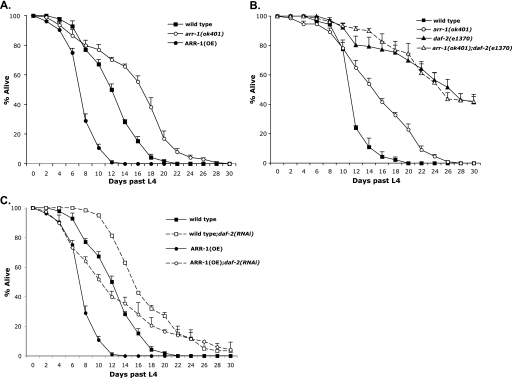

In vitro studies in mammalian cells have suggested that the IGF-1 receptor is regulated in part by non-visual arrestins (22). The presence of a single non-visual arrestin ortholog in C. elegans (ARR-1) enables in vivo analysis of the relationship between ARR-1 and the C. elegans IGF-1R ortholog, DAF-2. Previous studies show that ARR-1 is expressed almost exclusively within the C. elegans nervous system (27). DAF-2 is also expressed in the nervous system as well as in muscle and intestinal tissues (29), although insulin signaling within the nervous system regulates lifespan (30). Because DAF-2 signaling affects longevity, we explored a potential functional connection between ARR-1 and DAF-2 by determining whether arr-1 affects C. elegans lifespan. We found that wild-type animals have an average lifespan of 12.7 days and a maximum lifespan of 22 days, whereas the average and maximum lifespan of an arr-1 mutant allele (arr-1(ok401)) that does not express ARR-1 was increased by 35% (to 17.2 days) and 27% (to 28 days), respectively (Fig. 1A and Table 1). We also tested whether lifespan extension by arr-1 was dose-dependent by examining animals overexpressing ARR-1. These ARR-1(OE) transgenic animals carry an arr-1 genomic clone on a high copy transgene and express ∼3-fold higher ARR-1 than wild-type worms (27). ARR-1(OE) animals exhibited a 35% decrease in longevity when compared with wild-type animals with an average lifespan of 8.2 days and a maximum lifespan of 12 days (Fig. 1A and Table 1). Taken together, these results revealed that ARR-1 functions to decrease lifespan in C. elegans.

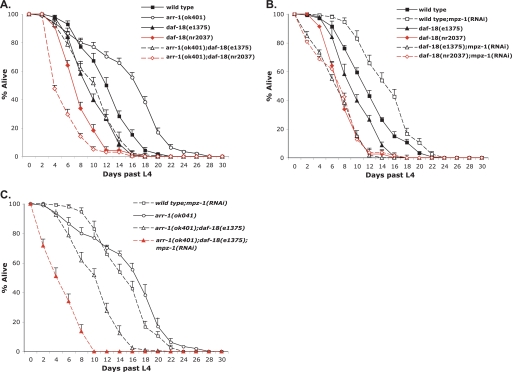

FIGURE 1.

Effect of arr-1 on longevity. A and B, lifespan of wild-type, arr-1(ok401) mutant, and ARR-1(OE) overexpressing animals at 20 °C (A) and wild-type, arr-1(ok401), daf-2(e1370), and arr-1(ok401);daf-2(e1370) mutant animals at 20 °C on plates containing 40 μm FUDR (B). daf-2(e1370) and arr-1(ok401);daf-2(e1370) mutant animals were kept at 15 °C until L4 stage and then transferred to 20 °C for remainder of assay. C, wild-type and ARR-1(OE) overexpressing animals fed daf-2 RNAi at 20 °C. Animals were kept at 15 °C until L4 stage and then transferred to 20 °C for remainder of assay. Each experiment was repeated at least three independent times with similar results. Error bars indicate S.E.

TABLE 1.

Effect of arr-1 on lifespan

Experiments were performed at least three independent times with similar results. Experiments were performed at 20 °C except as indicated.

| Strain | Mean lifespan ± S.E. | p valuea | Maximum lifespan | nb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| days | days | |||

| Wild type | 12.7 ± 0.8 | 22 | 180 | |

| arr-1(ok401) | 17.2 ± 1.2 | 0.001 | 28 | 210 |

| ARR-1(OE) | 8.2 ± 0.5 | <0.001, <0.001 | 12 | 150 |

| daf-2(e1370)c | 22.8 ± 1.3 | <0.001, <0.001 | >30 | 150 |

| arr-1(ok401);daf-2(e1370)c,d | 21.7 ± 1.0 | <0.001, <0.001 | >30 | 180 |

| daf-2(m596)c | 22.3 ± 1.2 | <0.001, <0.001 | >30 | 120 |

| arr-1(ok401);daf-2(m596)c,d | 18.5 ± 1.6 | <0.001, 0.018 | >30 | 120 |

| daf-2(e1391)c | 18.0 ± 1.4 | <0.001, 0.114 | >30 | 120 |

| arr-1(ok401);daf-2(e1391)c,d | 20.1 ± 1.3 | <0.001, 0.004 | >30 | 120 |

| wild type;daf-2(RNAi)c | 17.7 ± 0.9 | <0.001, 0.615 | >30 | 150 |

| ARR-1 OE;daf-2(RNAi)c | 13.4 ± 1.4 | 0.344, <0.001 | >30 | 120 |

| daf-16(mu86) | 11.7 ± 0.7 | 0.214, <0.001 | 18 | 150 |

| arr-1(ok401);daf-16(mu86) | 7.9 ± 0.8 | <0.001, <0.001 | 18 | 150 |

a p value corresponds to comparison of lifespan using log-rank test when compared with wild type (first number) and when compared with arr-1(ok401) (second number).

b n = Total number of animals scored.

c Animals were kept at 15 °C until L4 stage and then transferred to 20 °C for remainder of assay.

d Plates contained 40 μm FUDR.

ARR-1 Positively Regulates DAF-2 Signaling

The DAF-2 receptor also acts to decrease lifespan in C. elegans as mutations that decrease DAF-2 function increase lifespan (4, 5). The increased lifespan of daf-2 mutants is widely attributed to the decreased phosphorylation and subsequent nuclear localization of the forkhead transcription factor DAF-16 (13). Because arr-1(ok401) animals also exhibit increased longevity, this phenotype may be due to decreased DAF-2 signaling in these mutant animals. Similarly, the decreased longevity observed in ARR-1(OE) transgenic animals suggests an increase in DAF-2 signaling.

To investigate the role of ARR-1 in DAF-2 signaling, we evaluated the effect of ARR-1 expression on the longevity of daf-2 mutant animals by constructing arr-1(ok401);daf-2(e1370) double mutants. Although there are no null alleles of daf-2, the e3170 allele is mutated within the kinase domain of DAF-2 and is characterized as a strong class II mutant (5). In our assay, the average lifespan of daf-2(e1370) mutants was 22.8 days with a maximum lifespan of >30 days (Fig. 1B and Table 1). Surprisingly, we observed a significant decrease in longevity in our arr-1(ok401);daf-2(e1370) double mutants with ∼90% of the animals dying within 10 days (data not shown). However, we noticed that the majority of these deaths were the result of progeny hatching inside the mother, a phenotype referred to as matricide (31). To address this issue, we repeated the assay in the presence of 40 μm FUDR, which at low concentrations has been shown to prevent progeny from hatching inside the mother. We found no significant longevity differences in wild-type or arr-1 mutant animals in the presence of FUDR; however, the average lifespan of arr-1(ok401);daf-2(e1370) double mutants on FUDR plates was extended 26% when compared with arr-1 mutants (from 17.2 to 21.7 days) and was comparable with that of daf-2(e1370) mutants (Fig. 1B and Table 1). To confirm these results, we created two additional arr-1;daf-2 double mutant strains: arr-1(ok401);daf-2(m596) and arr-1(ok401);daf-2(e1391). The m596 allele is a substitution in the L2 ligand binding domain of DAF-2, whereas the e1391 allele is a substitution in the DAF-2 kinase domain (5, 32). The phenotypes of both double mutant strains mimicked that of arr-1(ok401);daf-2(e1370) mutant animals such that, in the presence of FUDR, the longevity of both strains was enhanced when compared with arr-1 mutant animals (Table 1). It is worth noting that although loss of ARR-1 had no significant effect on the longevity of the strong daf-2 alleles (e1370 and m596), it increased the longevity of the weaker daf-2(e1391) allele (Table 1).

We also examined the effect of decreased DAF-2 in the background of increased ARR-1 expression by using daf-2 RNAi in both wild-type and ARR-1(OE) transgenic animals. When treated with daf-2 RNAi, the average lifespan of wild-type animals increased 39% when compared with untreated animals (from 12.7 to 17.7 days) (Fig. 1C and Table 1), similar to previously reported results for knockdown of daf-2 by RNAi (33). Interestingly, ARR-1 overexpression suppressed the longevity phenotype of daf-2 RNAi-treated animals with a 24% decrease in average lifespan (from 17.7 to 13.4 days) (Fig. 1C and Table 1).

Because both arr-1(ok401) and daf-2(e1370) mutants exhibited increased longevity, we cannot order these genes using classical epistatic analysis. However, because the loss of arr-1 extended the lifespan of daf-2(e1391) mutants, whereas the overexpression of ARR-1 suppressed daf-2 mutant longevity, it appears that both proteins regulate lifespan within the same pathway and that ARR-1 functions downstream of DAF-2 to positively modulate DAF-2 signaling.

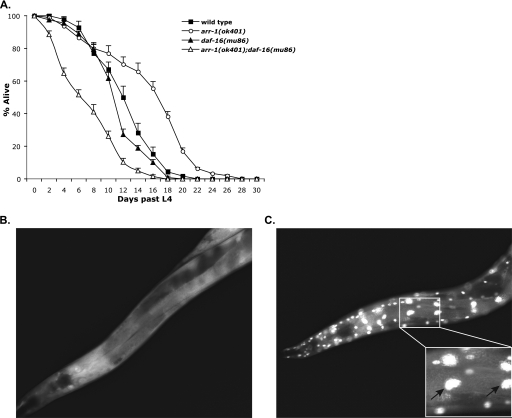

arr-1 Regulates Lifespan in a daf-16-dependent Manner

DAF-16 is the major downstream target of the DAF-2 signaling pathway in C. elegans and functions to regulate genes that are essential for daf-2-dependent longevity. Consequently, the longevity of all daf-2 mutant animals is completely suppressed by the loss of daf-16 (34). To further probe whether ARR-1 and DAF-2 act within the same pathway, we tested whether daf-16 suppresses the longevity of arr-1 mutants by generating arr-1(ok401);daf-16(mu86) mutant animals. The daf-16(mu86) mutation involves a deletion that removes most of the DAF-16 coding sequence and is considered to be a null (11). We observed that the average lifespan of arr-1(ok401);daf-16(mu86) double mutants was decreased by 54% when compared with arr-1 mutants (17.2–7.9 days), whereas the maximum lifespan was decreased by 36% (28–18 days) (Fig. 2A and Table 1). These results showed that daf-16 mutation effectively suppressed arr-1(ok401) longevity and suggest that ARR-1 acts upstream of DAF-16 in the DAF-2 pathway.

FIGURE 2.

arr-1 functions upstream of daf-16. A, lifespan of wild-type, arr-1(ok401), daf-16(mu86), and arr-1(ok401);daf-16(mu86) mutant animals at 20 °C. Error bars indicate S.E. B, transgenic Is[daf-16::gfp] animals displaying DAF-16::GFP in the cytosol. C, arr-1(ok041);Is[daf-16::gfp] animals displaying DAF-16::GFP in the nucleus. The images were taken at ×20. Exposure times for B and C are identical. The expanded inset shows the nuclear localization of DAF16·GFP in several cells.

DAF-16 function is regulated by its cellular localization. DAF-2-mediated activation of AKT-1, AKT-2, and SGK-1 leads to phosphorylation and subsequent cytoplasmic retention of DAF-16, whereas in the absence of DAF-2 activity, unphosphorylated DAF-16 moves into the nucleus and promotes the transcription of genes that mediate longevity (13, 35). Indeed, previous studies using GFP-tagged DAF-16 show that DAF-16 is cytosolic in wild-type animals, whereas it accumulates in the nucleus in daf-2 mutant animals (12). To confirm that ARR-1 positively regulates DAF-2 and functions upstream of DAF-16, we created an arr-1(ok401);Is[daf-16::gfp] double mutant strain to test whether loss of arr-1 affected DAF-16 localization. DAF-16 was localized in the cytosol in control Is[daf-16::gfp] animals (Fig. 2B), whereas it was predominantly localized within the nucleus in arr-1(ok401);Is[daf-16::gfp] animals (Fig. 2C). Taken together, these results demonstrate that ARR-1 acts upstream of DAF-16 to positively regulate DAF-2 signaling.

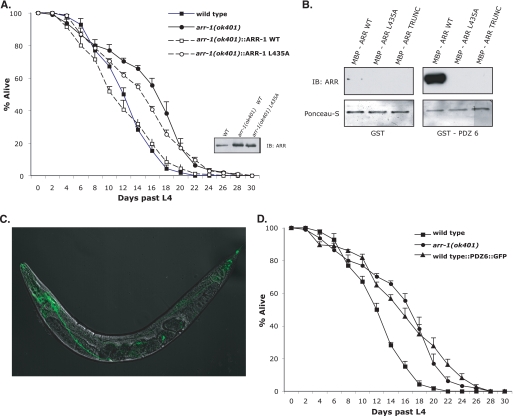

A C-terminal PDZ Binding Domain in ARR-1 Interacts with MPZ-1 and Is Required for Lifespan Regulation

Arrestins are adaptors and interact with numerous proteins to regulate receptor signaling and trafficking. Although C. elegans ARR-1 is ∼65% homologous to mammalian non-visual arrestins and contains a number of protein binding domains found in mammalian arrestins, one domain unique to C. elegans ARR-1 is a C-terminal class I PDZ binding motif (X(S/T)XL) (27). To investigate the functional significance of this PDZ binding motif, we expressed wild-type ARR-1 or a PDZ binding domain mutant (ARR-1-L435A) in arr-1(ok401) mutant animals and evaluated whether this motif played a role in the ability of ARR-1 to regulate lifespan. In these transgenic strains, ARR-1 and ARR-1-L435A, both driven by an arr-1 endogenous promoter, were overexpressed ∼2-fold over endogenous ARR-1 levels (Fig. 3A, inset). We found that the lifespan of arr-1 mutants expressing wild-type ARR-1 was fully rescued and was similar to that of wild-type animals (Fig. 3A and Table 2). In contrast, ARR-1-L435A did not effectively rescue the longevity phenotype of arr-1(ok401) mutants, and these animals exhibited a 24% increase in lifespan when compared with mutants expressing wild-type ARR-1 (from 12.2 to 15.1 days) (Fig. 3A and Table 2). Thus, the PDZ binding domain of ARR-1 mediates the ability of ARR-1 to regulate longevity.

FIGURE 3.

ARR-1 specifically interacts with PDZ6 of MPZ-1. A, lifespan analysis and rescue by arr-1(ok401) transgenic animals overexpressing wild-type (WT) or PDZ binding-deficient ARR-1 (ARR-1-L435A). Bottom right panel, immunoblot (IB) analysis of ARR-1 expression in wild-type and transgenic strains. Error bars indicate S.E. B, GST pulldown showing an interaction between ARR-1 and MPZ-1-PDZ6. This interaction is interrupted when the C-terminal residue of the PDZ binding domain is mutated (ARR-L435A) or truncated (ARR-TRUNC). The bottom blot was stained with Ponceau S to show equal loading of GST fusion proteins. C, localization of GFP-tagged MPZ-1 PDZ domain 6 in wild-type animals. The confocal image was taken at ×20. D, lifespan analysis and rescue by wild-type animals overexpressing MPZ-1-PDZ6 under an ARR-1-specific promoter. Error bars indicate S.E.

TABLE 2.

Effects of interaction between arr-1 and mpz-1 on lifespan

Experiments were performed at least three independent times with similar results. Experiments were performed at 20 °C except as indicated.

| Strain | Mean lifespan ± S.E. | p valuea | Maximum lifespan | nb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| days | days | |||

| Wild type | 12.7 ± 0.8 | 22 | 180 | |

| arr-1(ok401) | 17.2 ± 1.2 | <0.001 | 28 | 210 |

| arr-1(ok401);EX ARR-1 (FLWT) | 12.2 ± 1.0 | 0.932, 0.005 | 23 | 150 |

| arr-1(ok401);EX ARR-1 (L435A) | 15.1 ± 1.1 | 0.015, 0.442 | 28 | 270 |

| Wild type;PDZ6·GFP | 15.7 ± 1.4 | 0.004, 0.829 | 28 | 120 |

| mpz-1(RNAi) | 16.7 ± 0.8 | <0.001, 0.432 | 26 | 150 |

| arr-1(ok401);mpz-1(RNAi) | 8.6 ± 1.1 | 0.167, <0.001 | 20 | 180 |

| arr-1(ok401);mpz-1(RNAi)c | 13.6 ± 1.0 | 0.331, 0.056 | 26 | 150 |

| daf-2(e1370)d | 22.8 ± 1.3 | <0.001, <0.001 | >30 | 150 |

| daf-2(e1370);mpz-1(RNAi)d | 23.0 ± 1.0 | <0.001, <0.001 | >30 | 90 |

| daf-16(mu86) | 11.7 ± 0.7 | 0.214, <0.001 | 18 | 150 |

| daf-16(mu86);mpz-1(RNAi) | 9.9 ± 0.6 | 0.006, <0.001 | 18 | 120 |

| daf-18(e1375) | 10.3 ± 0.6 | 0.014, <0.001 | 16 | 120 |

| arr-1(ok401);daf-18(e1375) | 10.8 ± 0.7 | 0.085, <0.001 | 18 | 150 |

| daf-18(e1375);mpz-1(RNAi) | 7.7 ± 0.7 | <0.001, <0.001 | 14 | 120 |

| arr-1(ok401);daf-18(e1375);mpz-1 | 5.3 ± 0.5 | <0.001, <0.001 | 10 | 120 |

| daf-18(nr2037) | 8.4 ± 0.6 | <0.001, <0.001 | 16 | 120 |

| arr-1(ok401);daf-18(nr2037) | 6.1 ± 0.6 | <0.001, <0.001 | 16 | 150 |

| daf-18(nr2037);mpz-1(RNAi) | 7.7 ± 0.8 | <0.001, <0.001 | 18 | 120 |

| arr-1(ok401);daf-18(nr2037);mpz-1 | 4.9 ± 0.5 | <0.001, <0.001 | 10 | 120 |

a p value corresponds to comparison of lifespan using log-rank test: when compared with wild type (first number) or when compared with arr-1(ok401) (second number).

b n = Total number of animals scored.

c Plates contained 40 μm FUDR.

d Animals were kept at 15 °C until L4 stage and then transferred to 20 °C for remainder of assay.

To identify potential PDZ domains capable of binding to ARR-1, a GST fusion protein containing the last 110 residues of ARR-1 was used to screen a proteomic array of mammalian class I PDZ domains. Out of this screen, a specific interaction was identified between ARR-1 and PDZ domain 5 of human INADL (data not shown). Human INADL is a multi-PDZ domain-containing protein that functions to organize protein complexes at cell membranes and is homologous to Drosophila InaD, a scaffolding protein involved in phototransduction (36). Interestingly, human INADL shares significant similarity to MPZ-1, a multiple PDZ domain-containing protein found in C. elegans. Although the function of MPZ-1 is not well characterized, it has been shown to facilitate serotonin-stimulated egg laying mediated by the SER-1 receptor (37). A sequence alignment with all C. elegans PDZ domains revealed that PDZ domain 5 of human INADL is most homologous (49% identical) to PDZ domain 6 of C. elegans MPZ-1. To test for a possible interaction between ARR-1 and MPZ-1, we incubated a GST fusion protein containing MPZ-1 PDZ domain 6 (GST·PDZ6) with purified MBP fusion proteins containing the C-terminal 114 amino acids from wild-type ARR-1 (MBP·ARR-1), a PDZ binding domain mutant ARR-1 (MBP·ARR-1-L435A), or a truncated ARR-1 lacking the C-terminal 4 amino acids (MBP·ARR-1-TRUNC). Our results showed that GST·PDZ6 binds to ARR-1 and that this interaction is disrupted by mutation of the C-terminal leucine or by deletion of the C-terminal 4 amino acids (Fig. 3B). This demonstrates that the C-terminal PDZ binding domain of ARR-1 is essential for the interaction between these two proteins.

Because PDZ domain-containing proteins organize signaling complexes, ARR-1 may interact with MPZ-1 as part of a complex within the DAF-2 pathway. To test this, we overexpressed GFP-tagged MPZ-1-PDZ6 in wild-type animals under the control of an arr-1-specific promoter and examined the lifespan of these transgenic animals. If ARR-1 specifically interacts with MPZ-1 PDZ6, then overexpressed PDZ6 should bind to ARR-1 and serve as a dominant negative to disrupt the interaction between endogenous ARR-1 and MPZ-1. GFP-tagged PDZ6 was primarily detected within the nervous system of wild-type animals (Fig. 3C), similar to the expression pattern of GFP-tagged ARR-1 (27). Interestingly, the average lifespan of wild-type animals overexpressing MPZ-1-PDZ6 was increased by 24% (12.7–15.7 days), similar to that of arr-1 mutant animals (Fig. 3D and Table 2). Taken together, these results suggest that ARR-1 interaction with MPZ-1 is required for the longevity phenotype observed in arr-1 mutant animals and that MPZ-1 plays a role in regulating C. elegans longevity.

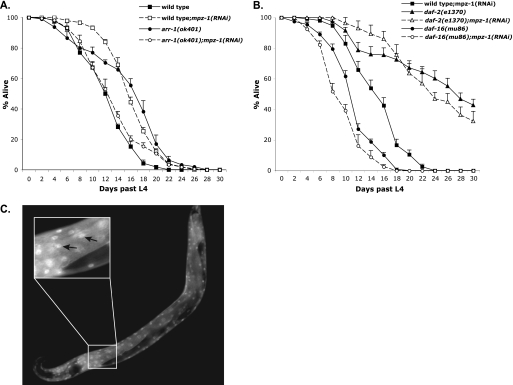

MPZ-1 Regulates Lifespan in C. elegans

To explore the role of MPZ-1 within the IIS pathway, we tested whether mpz-1 functions to regulate lifespan in C. elegans. Previous studies have reported that MPZ-1 is expressed throughout the nervous system, body wall, and vulval muscles, similar to the expression patterns of ARR-1 and DAF-2 (37). Because it is predicted that a null allele of mpz-1 is embryonic lethal, we used RNAi to reduce MPZ-1 expression. Wild-type animals treated with mpz-1 RNAi exhibited a 31% increase in average lifespan when compared with untreated wild-type animals (from 12.7 to 16.7 days) (Fig. 4A and Table 2), suggesting that MPZ-1 plays a role in regulating longevity in C. elegans. Surprisingly, arr-1 mutants exhibited a sharp decrease in lifespan when treated with mpz-1 RNAi, similar to the results we observed in arr-1;daf-2 double mutants on plates without FUDR (Table 2 and data not shown). Repeating this assay on plates containing 40 μm FUDR rescued this early mortality, although we observed that the longevity of these arr-1;mpz-1(RNAi) double mutants was still decreased when compared with arr-1 mutants and was similar to that of wild-type animals (Fig. 4A and Table 2). The decreased lifespan of arr-1(ok401);mpz-1(RNAi) mutants when compared with arr-1(ok401) suggests that MPZ-1 is required for the longevity phenotype of arr-1 mutant animals. Moreover, the wild-type longevity phenotype of the arr-1(ok401);mpz-1(RNAi) mutants suggests that arr-1 and mpz-1 mutually suppress each other's longevity phenotype and that the interaction between these two proteins is crucial for their regulation of DAF-2 signaling.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of mpz-1 on longevity. A, lifespan of wild type and arr-1(ok401) fed mpz-1 RNAi at 20 °C on plates containing 40 μm FUDR. B, lifespan of wild-type, daf-2(e1370), and daf-16(mu86) mutant animals fed mpz-1 RNAi at 20 °C. daf-2(e1370) mutants were kept at 15 °C until L4 stage and then transferred to 20 °C for remainder of assay. Error bars in A and B indicate S.E. C, transgenic Is[daf-16::gfp] animals fed mpz-1 RNAi at 20 °C. In these animals, DAF-16·GFP is localized to the nucleus. The image was taken at ×20. The expanded inset shows the nuclear localization of DAF16·GFP in several cells.

To establish that MPZ-1 contributes to lifespan within the DAF-2 signaling pathway, we determined whether loss of mpz-1 had any effect on the longevity of daf-2 mutant animals. We treated daf-2(e1370) mutants with mpz-1 RNAi and found that the average lifespan of daf-2(e1370);mpz-1(RNAi) animals was increased by 38% when compared with mpz-1(RNAi) mutant animals (from 16.7 to 23 days) (Fig. 4B and Table 2). We also tested whether the longevity of mpz-1 mutants, like arr-1 and daf-2 mutants, required daf-16 by evaluating the lifespan of daf-16(mu86) mutant animals treated with mpz-1 RNAi. The lifespan of daf-16(mu86);mpz-1(RNAi) double mutants decreased by 41% when compared with mpz-1(RNAi) mutants (from 16.7 to 9.9 days), indicating that mpz-1 longevity was suppressed by daf-16 (Fig. 4B and Table 2). We note that the enhancement of mpz-1 longevity in the daf-2 mutants and suppression of longevity in the daf-16 mutants is similar to what we observed in arr-1 mutants crossed into these same backgrounds.

To further support the conclusion that MPZ-1 regulates DAF-2 signaling, we tested whether the loss of mpz-1 affected the localization of DAF-16. We treated Is[daf-16::gfp] transgenic animals with mpz-1 RNAi and found that GFP-tagged DAF-16 was predominantly localized in the nucleus in these animals, similar to arr-1(ok401);Is[daf-16::gfp mutant animals (Fig. 4C). This demonstrates that DAF-16 phosphorylation is decreased in mpz-1(RNAi) mutant animals, suggesting that DAF-2 signaling is decreased. Taken together, our data strongly suggest that MPZ-1, like ARR-1, acts to positively regulate DAF-2 signaling upstream of DAF-16 in C. elegans.

The Longevity of arr-1 and mpz-1 Mutants Is Dependent on daf-18

Our results reveal that both ARR-1 and MPZ-1 positively regulate DAF-2 signaling as the phenotypes observed in each mutant (i.e. lifespan extension and DAF-16·GFP localization) were similar to those of daf-2 mutants. Therefore, we hypothesized that the lifespan of arr-1(ok401);mpz-1(RNAi) double mutants would mimic that of daf-2 mutants, extending beyond that of the individual mutant animals. However, the loss of both proteins resulted in a wild-type longevity phenotype (Fig. 4A), suggesting that DAF-2 signaling is near wild-type levels in arr-1(ok401);mpz-1(RNAi) mutant animals. This suggests that ARR-1-MPZ-1-mediated regulation of DAF-2 signaling in worms is complex and may involve additional components.

DAF-18, the worm ortholog of the human tumor suppressor PTEN, negatively regulates the DAF-2 signaling pathway in C. elegans by dephosphorylating phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate, a direct product of PI3K activation (14–16). As a result of this negative regulation, DAF-16 phosphorylation is ultimately decreased and daf-18 mutants typically exhibit decreased longevity, as shown in Fig. 5A. Recently, it was demonstrated that human PTEN rescues DAF-18 function in daf-18 mutant animals (38). Interestingly, these genetic and biochemical studies demonstrated that the PDZ binding domain of human PTEN played a critical role in regulating lifespan in the worm. Because DAF-18 contains a class II C-terminal PDZ binding motif, we evaluated whether DAF-18 is involved in the ARR-1-MPZ-1 regulation of DAF-2 signaling, perhaps via interaction with MPZ-1.

FIGURE 5.

daf-18 is required for arr-1 and mpz-1 mutant longevity. A and B, lifespan of wild-type, arr-1(ok401), daf-18(e375), daf-18(nr2037), arr-1(ok401);daf-18(e375), and arr-1(ok401);daf-18(nr2037) mutant animals at 20 °C (A) and wild-type, daf-18(e375), daf-18(nr2037), arr-1(ok401);daf-18(e375), and arr-1(ok401);daf-18(nr2037) mutant animals fed mpz-1 RNAi at 20 °C (B). C, mpz-1(RNAi), arr-1(ok401), arr-1(ok401);daf-18(e1375), and arr-1(ok401);daf-18(e1375;mpz-1(RNAi) mutant animals at 20 °C. Each experiment was repeated at least three independent times with similar results. Error bars indicate S.E.

To investigate the role of DAF-18 on ARR-1-MPZ-1-mediated regulation of DAF-2 signaling, we first examined the relationship between DAF-18 and ARR-1 by testing whether the longevity of arr-1(ok401) mutants was dependent on daf-18. We constructed two arr-1(ok401);daf-18 double mutant strains and found that arr-1(ok401);daf-18(e1375) mutants displayed a 37% decrease in average lifespan when compared with arr-1(ok401) (from 17.2 to 10.8 days), whereas arr-1(ok041);daf-18(nr2037) mutants exhibited a 65% decrease in average lifespan (from 17.2 to 6.1 days). These results demonstrate that both daf-18 mutant alleles effectively suppress the arr-1 longevity phenotype (Fig. 5A and Table 2). We next investigated the relationship between DAF-18 and MPZ-1 by testing whether the longevity of mpz-1(RNAi) mutant animals was dependent on daf-18. We treated both daf-18 mutant strains with mpz-1 RNAi and found that the average lifespan of both daf-18;mpz-1(RNAi) double mutants was decreased by 54% when compared with mpz-1 RNAi mutants alone (from 16.7 to 7.7 days), demonstrating that daf-18 also suppressed the mpz-1(RNAi) mutant longevity phenotype (Fig. 5B and Table 2). Collectively, these results reveal that daf-18 is required for the lifespan extension observed in both arr-1 and mpz-1(RNAi) mutants and suggest that both proteins function upstream of DAF-18 in the DAF-2 pathway.

ARR-1 and MPZ-1 Interact with DAF-18 and Regulate DAF-18 Function

Although these experiments establish that the longevity of both arr-1 and mpz-1(RNAi) mutant animals was suppressed by daf-18, we note that the extent of suppression was dependent on the particular daf-18 allele. For example, in the arr-1 mutant background, the daf-18(nr2037) allele suppressed longevity to a greater extent than daf-18(e1375) (Fig. 5A and Table 2). The daf-18(e1375) mutation represents a 30-bp insertion downstream of the phosphatase catalytic domain that leads to a premature termination and is considered a weak allele, whereas the daf-18(nr2037) mutation is a deletion and is predicted to be a null (14–16). The nature of these mutations suggests that phosphatase activity of DAF-18 is partially reduced in daf-18(e1375) mutants and eliminated in daf-18(nr2037) mutants (16). Indeed, the longevity phenotypes of these daf-18 mutant animals lend support to this hypothesis with daf-18(e1375) animals living 10.3 days on average, whereas daf-18(nr2037) animals live only 8.4 days (Table 2). Taking this into consideration, we conclude that DAF-18 is still partially functional in the arr-1(ok401);daf-18(e1375) mutant animals when compared with arr-1(ok401);daf-18(nr2037) (Fig. 5A). In contrast, the lifespan curves of mpz-1(RNAi);daf-18(e1375) and mpz-1(RNAi);daf-18(nr2037) mutants were virtually identical (Fig. 5B). These data suggest that in the absence of MPZ-1, DAF-18 function is decreased and is in direct contrast to what we observe in the absence of ARR-1 in the partially functional daf-18(e1375) mutants. To further investigate the impact of MPZ-1 on DAF-18 function, we treated arr-1(ok401);daf-18(e1375) and arr-1(ok401);daf-18(nr2037) double mutants with mpz-1(RNAi) and determined the lifespan of each triple mutant. The loss of mpz-1 suppressed the partial function of DAF-18 in the arr-1(ok401);daf-18(e1375) mutant background as evidenced by the 51% decrease in lifespan between arr-1(ok401);daf-18(e1375) and arr-1(ok401);daf-18(e1375);mpz-1(RNAi) mutant animals (from 10.8 to 5.3 days) (Fig. 5C and Table 2). Conversely, the loss of mpz-1 had a modest effect on the already diminished lifespan (and activity of DAF-18) of arr-1(ok401);daf-18(nr2037) mutant animals (Table 2). Taken together, the data suggest that although the interaction between ARR-1 and MPZ-1 modulates DAF-2 signaling, ARR-1 and MPZ-1 appear to have opposing effects on the ability of DAF-18 to regulate this pathway.

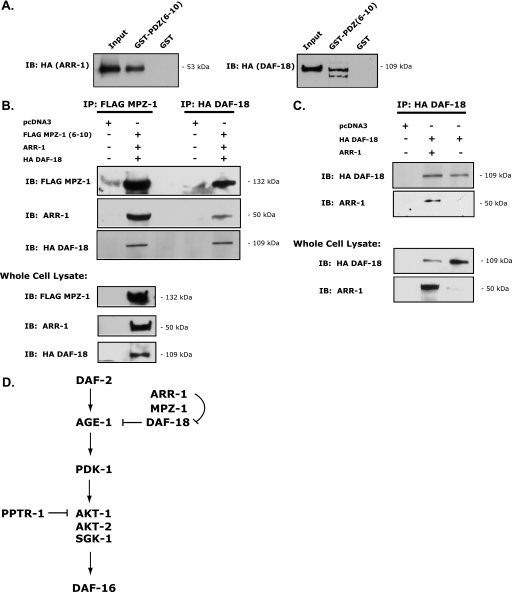

To further explore the relationship between ARR-1, MPZ-1, and DAF-18, we evaluated the nature of the interaction between these proteins. We previously demonstrated that ARR-1 binds to PDZ6 of MPZ-1 through its C-terminal PDZ binding domain (Fig. 3B). Because DAF-18 contains a class II C-terminal PDZ binding domain (ΦXΦ, where Φ is a hydrophobic amino acid), we hypothesized that DAF-18 also might directly interact with MPZ-1. To test this, we expressed PDZ domains 6–10 of MPZ-1 as a GST fusion protein and then determined its ability to bind to HA-tagged DAF-18. Our pulldown assays showed that DAF-18 binds to GST·MPZ-1-(PDZ6–10), suggesting a direct interaction between these proteins (Fig. 6A, right panel). As expected, HA-tagged ARR-1 also effectively bound to GST·MPZ-1-(PDZ6–10) (Fig. 6A, left panel). Because arrestin and multi-PDZ domain-containing proteins, such as MPZ-1, are scaffolding proteins that organize signaling complexes and both DAF-18 and ARR-1 bind directly to MPZ-1, it is conceivable that all three proteins form a functional signaling complex. To investigate this possibility, we co-expressed ARR-1, HA-DAF-18, and FLAG-MPZ-1-(PDZ6–10) in COS-1 cells and then immunoprecipitated either HA (DAF-18) or FLAG (MPZ-1). Immunoprecipitation of either DAF-18 or MPZ-1 resulted in co-immunoprecipitation of all three proteins (Fig. 6B), providing compelling evidence that MPZ-1 acts as a scaffold to organize a complex consisting of ARR-1 and DAF-18. Interestingly, in cells co-transfected with only HA-DAF-18 and ARR-1, we were also able to detect interaction between ARR-1 and DAF-18, suggesting that ARR-1 can bind to DAF-18 in the absence of MPZ-1 (Fig. 6C). Taken together, our genetic and biochemical studies strongly support the existence of an ARR-1-MPZ-1-DAF-18 complex that functions to modulate the DAF-2 signaling pathway in C. elegans.

FIGURE 6.

ARR-1 forms a complex with MPZ-1 and DAF-18. A, left panel, GST pulldown showing an interaction between MPZ-1 PDZ domains 6–10 and ARR-1. The input equals 0.5% of the lysate used in the binding experiment. Right panel, GST pulldown showing an interaction between MPZ-1 PDZ domains 6–10 and DAF-18 (right panel). The input equals 2% of the lysate used in the binding experiment. IB, immunoblot. B, co-immunoprecipitation (IP) assay showing that ARR-1, HA-tagged DAF-18, and FLAG-tagged MPZ-1 PDZ domains 6–10 precipitate together in a complex. The bottom blot represents protein expression in ∼4 μg of total protein lysate. C, co-immunoprecipitation assay showing an interaction between ARR-1 and HA-tagged DAF-18. The bottom blot represents protein expression in ∼4 μg of total protein lysate. D, proposed model illustrating the role of ARR-1 in the DAF-2 signaling pathway. DAF-2 activation leads to the phosphorylation and negative regulation of the transcription factor DAF-16, an event mediated by the kinase signaling cascade downstream of DAF-2, consisting of AGE-1, PDK-1, and SGK-1/AKT 1/2. ARR-1 forms a complex with MPZ-1 and DAF-18 within the DAF-2 signaling pathway, where ARR-1 and MPZ-1 act together to regulate DAF-18 and ultimately function to positively regulate DAF-2. In turn, this negatively regulates DAF-16, leading to an increase in longevity.

DISCUSSION

Although many different biological processes have been proposed to influence lifespan, the link between aging and the insulin/IGF-1 receptor signaling pathway has been established in many different species (3). Numerous studies have demonstrated that genes involved in the IGF-1R pathway are evolutionarily conserved and that disruption of this signaling cascade results in lifespan extension (6). Here, we describe an in vivo role for ARR-1 as a modulator of IGF-1R (DAF-2) signaling and reveal a role for ARR-1 in lifespan regulation in C. elegans. Our results provide evidence that ARR-1 regulates DAF-2 signaling through an interaction with MPZ-1, a multi-PDZ domain-containing protein. Our model proposes that ARR-1 and MPZ-1 regulate the function of the PTEN ortholog DAF-18 within the DAF-2 pathway (Fig. 6D).

Although it is known that the DAF-2 pathway controls lifespan in C. elegans, the wide range of downstream genes regulated by DAF-2 and parallel pathways that influence lifespan underscore the complexity of DAF-2 signaling (31, 39). We establish that ARR-1 is necessary for maintaining normal lifespan in C. elegans, as evidenced by the increased longevity exhibited by arr-1(ok401) mutant animals and the decreased longevity observed in animals overexpressing ARR-1. The longevity of arr-1 mutant animals was dependent upon the activity of both daf-16 and daf-18, two genes known to function downstream of daf-2, indicating that ARR-1 contributes to the control of lifespan within the DAF-2 signaling pathway. Additionally, we show that the loss of daf-2 enhances the longevity of arr-1 mutants, whereas the overexpression of ARR-1 suppresses the longevity of daf-2 mutant animals. Combined with the observation that DAF-16 accumulates in the nucleus of arr-1 mutant animals, a phenotype indicative of decreased DAF-16 phosphorylation, we conclude that ARR-1 acts to positively regulate DAF-2 signaling in C. elegans.

In investigating the mechanism by which ARR-1 regulates DAF-2 signaling, we identified a novel interaction between ARR-1 and the multi-PDZ domain-containing protein MPZ-1. The PDZ domains of MPZ-1 are most homologous to those of INAD, a scaffolding protein that mediates phototransduction signaling in Drosophila (40). The interaction between ARR-1 and MPZ-1 is direct and is mediated by a class I PDZ binding domain located in the C-tail of ARR-1, a motif not present in mammalian arrestins. We establish that the interaction between ARR-1 and MPZ-1 is required for ARR-1 to positively regulate DAF-2 signaling, as evidenced by the enhanced longevity observed in animals where ARR-1-MPZ-1 interaction is disrupted. Together, these results suggest that DAF-2 signaling is modulated in vivo by the interaction between ARR-1 and MPZ-1. Our studies also reveal a novel role for MPZ-1 in lifespan regulation. We find that mpz-1 mutant animals exhibit an increase in lifespan that is suppressed by both daf-18 and daf-16 and is enhanced by the loss of daf-2. Therefore, we conclude that MPZ-1 plays a positive regulatory role within the C. elegans IGF-1R pathway.

Collectively, our data suggest that DAF-2 signaling is decreased in arr-1 and mpz-1 mutant animals and that these proteins act to positively regulate DAF-2. Although we anticipated that arr-1;mpz-1 double mutants would live even longer than the individual mutants, the longevity phenotype of these animals was almost identical to that of wild-type animals. In further characterizing the arr-1 and mpz-1 mutant phenotypes, we found that daf-18 suppressed the longevity phenotypes of both arr-1 and mpz-1 mutants, suggesting that DAF-18 is required for ARR-1 and MPZ-1 to positively regulate DAF-2. However, in these assays, we establish that the extent of suppression by daf-18 is not only dependent upon its catalytic activity but is also dependent upon the presence of mpz-1. Because DAF-18 is known to function as a negative regulator of DAF-2 and our data demonstrate that DAF-18 interacts with MPZ-1, we propose that ARR-1, MPZ-1, and DAF-18 form a complex that regulates DAF-2 signaling (Fig. 6D).

In our model, MPZ-1 acts as a scaffold that binds both ARR-1 and DAF-18, bringing all three proteins together in a complex. Within this complex, we propose that ARR-1 acts to negatively regulate DAF-18 function. In contrast, MPZ-1 appears to function either as a negative or as a positive regulator of DAF-18, dependent upon whether MPZ-1 is bound to ARR-1. This dual role of MPZ-1 explains the wild-type lifespan phenotype observed in arr-1(ok401);mpz-1(RNAi) mutants. We propose that when MPZ-1 is bound to ARR-1, it functions to negatively regulate DAF-18 by promoting ARR-1 interaction with and inhibition of DAF-18. In the absence of ARR-1, MPZ-1 remains bound to DAF-18, where it can act to positively regulate DAF-18 function (perhaps by functioning as a scaffold for other regulatory proteins). This conclusion is based on our genetic studies that show that in daf-18(e1375) mutants, where DAF-18 is predicted to be partially functional, the loss of arr-1 has no inhibitory effect on the activity of daf-18, whereas the loss of mpz-1 reduces the function of daf-18(e1375) and attenuates the function of daf-18(e1375) in the arr-1 mutant background.

In mammals, the expanding role of arrestins, from proteins that function to desensitize G protein-coupled receptors to scaffolding proteins that transduce signals emanating from these receptors, highlights the many ways in which arrestin functions to modulate signaling within a cell (41). Although these multifunctional roles of arrestin are best characterized for G protein-coupled receptors, arrestins have been shown to regulate numerous types of receptors, including the IGF-1 and insulin receptors (21). Within the mammalian IGF-1R signaling pathway, arrestin2 has been shown to play a dual regulatory role, acting both as an adaptor protein to promote receptor ubiquitination and downregulation and as a scaffolding protein that transduces IGF-1-induced mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase signaling (22, 24). In addition, arrestin2 has been implicated in the activation of PI3K in response to IGF-1 stimulation, an event that leads to the activation of AKT and impacts many fundamental cellular processes (23). The precise mechanism by which this occurs is not fully delineated; however, it appears to be independent of both the kinase activity of the IGF-1 receptor and the activity of the non-receptor tyrosine kinase Src, a known regulator of AKT activity. More recently, arrestin3 has been identified as a positive regulator of the mammalian insulin signaling pathway in vivo (42). In this study, arrestin3 plays a crucial role in the mechanism by which AKT is activated in response to insulin stimulation, acting as an adaptor protein that brings AKT and Src together in a signaling complex. In contrast to IGF-1R signaling, AKT activation in this pathway is dependent upon Src and does not affect PI3K. Taken together, these studies illustrate that both arrestin2 and arrestin3 regulate IIS signaling; however, they also highlight the complexity of these arrestin-mediated regulatory mechanisms. Our studies show that in C. elegans, the non-visual arrestin ortholog ARR-1 regulates the IGF-1R (DAF-2) signaling pathway, similar to mammalian cells. However, we find that ARR-1 regulates IIS signaling by modulating the activity of the PTEN ortholog DAF-18 through an interaction with the multi-PDZ domain-containing protein MPZ-1. Our data show that both ARR-1 and DAF-18 bind to MPZ-1, and we propose that ARR-1 negatively regulates DAF-18.

Further investigation is required to determine the precise mechanism by which ARR-1 negatively regulates DAF-18 function. Although we suggest that DAF-18 is regulated as part of an ARR-1-MPZ-1-DAF-18 signaling complex, it is possible that these three proteins are not the only components of this signaling complex. Because ARR-1 is an adaptor protein, the formation of this complex or components of this complex may be regulated by the presence of ARR-1 and therefore may determine whether DAF-18 is negatively or positively regulated. Although the regulation of DAF-18 is not well characterized, the regulation of PTEN is also not fully understood. It has been established that the membrane localization and catalytic activity of PTEN in mammals are not dependent upon its PDZ binding domain; rather, PTEN activity is regulated by its phosphorylation status (43). For instance, it appears that C-terminal phosphorylation of PTEN hinders its ability to be targeted to the membrane, leading to decreased activity (44). Because our studies reveal that ARR-1 and DAF-18 are able to directly interact (Fig. 6C), this suggests that mammalian arrestins and PTEN might also be able to interact. Although this remains to be tested, we would speculate that such interaction might be regulated by the phosphorylation status of PTEN because arrestins are phospho-binding proteins (45).

As mentioned previously, MPZ-1 is most homologous to INAD proteins, which in Drosophila organizes phototransduction signaling complexes containing many different components including rhodopsin, phospholipase C, transient receptor potential (TRP) channel, TRP-like channel, protein kinase C, myoIII, and calmodulin (40, 46). Although we have shown that MPZ-1 interacts with ARR-1 and DAF-18, previous studies have shown that MPZ-1 also functions to regulate the serotonin receptor SER-1 in C. elegans (37). Moreover, it is worth noting that SGK-1 also contains a C-terminal PDZ binding domain and thus may also be part of the MPZ-1 signaling complex. Comparing the similarities of these signaling complexes between mammals and worms, we propose that it is the changing dynamics of the components within the ARR-1-MPZ-1-DAF-18 complex that most likely dictate the mechanism by which DAF-18 is regulated.

In this study, we illustrate a novel role for ARR-1 as a modulator of lifespan in C. elegans. We propose that ARR-1 and MPZ-1 interact and function as a positive regulator of the DAF-2 signaling pathway. We propose that these proteins work in concert to modulate lifespan within the DAF-2 pathway as part of a multi-protein signaling complex, which includes the PTEN ortholog DAF-18. Within this complex, we suggest that ARR-1 inhibits DAF-18 and that this function of ARR-1 is dependent upon its interaction with MPZ-1. Because MPZ-1 binds both ARR-1 and DAF-18, we conclude that MPZ-1 plays a critical role in the formation of this regulatory signaling complex and that it plays a dual role as a positive and negative regulator of DAF-18, depending on whether MPZ-1 is bound to ARR-1. These studies establish a novel mechanism by which a multi-protein complex regulates the physiological events associated with the IIS pathway in C. elegans. Although our studies reveal that ARR-1 and MPZ-1 function within the IIS pathway in C. elegans, our conclusions are primarily based on genetic and biochemical evidence and will need to be bolstered by additional biochemical, cell biological, and pharmacological strategies to define the precise localization and mechanism of this regulation.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Caenorhabditis Genetic Center and the C. elegans Gene Knockout Consortium for providing most of the strains used in this study. We thank Drs. Yuji Kohara and Michael J. Stern for cDNA constructs and C. elegans strains, Drs. Coleen Murphy, Cori Bargmann, Eric Moss, and Adriano Marchese for valuable discussion, Dr. Randy Hall for analysis of ARR-1 binding to mammalian PDZ domains, and Dr. Terry Hyslop for help with the statistical analysis.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R37 GM047417 (to J. L. B.).

This article was selected as a Paper of the Week.

- IIS

- insulin/IGF-1

- IGF-1

- insulin-like growth factor-1

- IGF-1R

- insulin-like growth factor receptor

- FUDR

- 5-fluorodeoxyuridine

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein

- GST

- glutathione S-transferase

- MBP

- maltose-binding protein

- PI3K

- phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- PTEN

- phosphatase and tensin homolog

- RNAi

- RNA interference

- HA

- hemagglutinin

- OE

- overexpressing.

REFERENCES

- 1.Guarente L., Kenyon C. (2000) Nature 408, 255–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbieri M., Bonafè M., Franceschi C., Paolisso G. (2003) Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 285, E1064–E1071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tatar M., Bartke A., Antebi A. (2003) Science 299, 1346–1351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kenyon C., Chang J., Gensch E., Rudner A., Tabtiang R. (1993) Nature 366, 461–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kimura K. D., Tissenbaum H. A., Liu Y., Ruvkun G. (1997) Science 277, 942–946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antebi A. (2007) PLoS Genet. 3, 1565–1571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morris J. Z., Tissenbaum H. A., Ruvkun G. (1996) Nature 382, 536–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paradis S., Ruvkun G. (1998) Genes Dev. 12, 2488–2498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paradis S., Ailion M., Toker A., Thomas J. H., Ruvkun G. (1999) Genes Dev. 13, 1438–1452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hertweck M., Göbel C., Baumeister R. (2004) Dev. Cell 6, 577–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin K., Dorman J. B., Rodan A., Kenyon C. (1997) Science 278, 1319–1322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henderson S. T., Johnson T. E. (2001) Curr. Biol. 11, 1975–1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee R. Y., Hench J., Ruvkun G. (2001) Curr. Biol. 11, 1950–1957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ogg S., Ruvkun G. (1998) Mol. Cell 2, 887–893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gil E. B., Malone Link E., Liu L. X., Johnson C. D., Lees J. A. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 2925–2930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mihaylova V. T., Borland C. Z., Manjarrez L., Stern M. J., Sun H. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 7427–7432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Padmanabhan S., Mukhopadhyay A., Narasimhan S. D., Tesz G., Czech M. P., Tissenbaum H. A. (2009) Cell 136, 939–951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dorman J. B., Albinder B., Shroyer T., Kenyon C. (1995) Genetics 141, 1399–1406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baserga R. (1995) Cancer Res. 55, 249–252 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larsson O., Girnita A., Girnita L. (2005) Br. J. Cancer 92, 2097–2101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barki-Harrington L., Rockman H. A. (2008) Physiology 23, 17–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin F. T., Daaka Y., Lefkowitz R. J. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 31640–31643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Povsic T. J., Kohout T. A., Lefkowitz R. J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 51334–51339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Girnita L., Shenoy S. K., Sehat B., Vasilcanu R., Girnita A., Lefkowitz R. J., Larsson O. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 24412–24419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brenner S. (1974) Genetics 77, 71–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mello C. C., Kramer J. M., Stinchcomb D., Ambros V. (1991) EMBO J. 10, 3959–3970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palmitessa A., Hess H. A., Bany I. A., Kim Y. M., Koelle M. R., Benovic J. L. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 24649–24662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kamath R. S., Martinez-Campos M., Zipperlen P., Fraser A. G., Ahringer J. (2001) Genome Biol. 2, RESEARCH0002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hunt-Newbury R., Viveiros R., Johnsen R., Mah A., Anastas D., Fang L., Halfnight E., Lee D., Lin J., Lorch A., McKay S, Okada H. M., Pan J., Schulz A. K., Tu D., Wong K., Zhao Z., Alexeyenko A., Burglin T., Sonnhammer E., Schnabel R., Jones S. J., Marra M. A., Baillie D. L., Moerman D. G. (2007) PLoS Biol. 5, e237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolkow C. A., Kimura K. D., Lee M. S., Ruvkun G. (2000) Science 290, 147–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shaw W. M., Luo S., Landis J., Ashraf J., Murphy C. T. (2007) Curr. Biol. 17, 1635–1645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scott B. A., Avidan M. S., Crowder C. M. (2002) Science 296, 2388–2391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hansen M., Hsu A. L., Dillin A., Kenyon C. (2005) PLoS Genet. 1, 119–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patel D. S., Garza-Garcia A., Nanji M., McElwee J. J., Ackerman D., Driscoll P. C., Gems D. (2008) Genetics 178, 931–946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin K., Hsin H., Libina N., Kenyon C. (2001) Nat. Genet. 28, 139–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Philipp S., Flockerzi V. (1997) FEBS Lett. 413, 243–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xiao H., Hapiak V. M., Smith K. A., Lin L., Hobson R. J., Plenefisch J., Komuniecki R. (2006) Dev. Biol. 298, 379–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Solari F., Bourbon-Piffaut A., Masse I., Payrastre B., Chan A. M., Billaud M. (2005) Oncogene 24, 20–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Larsen P. L., Albert P. S., Riddle D. L. (1995) Genetics 139, 1567–1583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tsunoda S., Sierralta J., Sun Y., Bodner R., Suzuki E., Becker A., Socolich M., Zuker C. S. (1997) Nature 388, 243–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lefkowitz R. J., Rajagopal K., Whalen E. J. (2006) Mol. Cell 24, 643–652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luan B., Zhao J., Wu H., Duan B., Shu G., Wang X., Li D., Jia W., Kang J., Pei G. (2009) Nature 457, 1146–1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gericke A., Munson M., Ross A. H. (2006) Gene 374, 1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Das S., Dixon J. E., Cho W. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 7491–7496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Celver J., Vishnivetskiy S. A., Chavkin C., Gurevich V. V. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 9043–9048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang T., Montell C. (2007) Pflugers Arch. 454, 821–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]