Abstract

The cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27Kip1 plays a critical role in regulating entry into and exit from the cell cycle. Post-transcriptional regulation of p27Kip1 expression is of significant interest. The embryonic lethal abnormal vision (ELAV)-like RNA-binding protein HuR is thought be important for the translation of p27Kip1, however, different reports attributed diametrically opposite roles to HuR. We report here an alternative mechanism wherein HuR regulates stability of the p27Kip1 mRNA. Specifically, human and mouse p27Kip1 mRNAs interact with HuR protein through multiple U-rich elements in both 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (UTR). These interactions, which occur in vitro and in vivo, stabilize p27Kip1 mRNA and play a critical role in its accumulation. Deleting HuR binding sites or knocking down HuR expression destabilizes p27Kip1 mRNA and reduces its accumulation. We also identified a CT repeat in the 5′ UTR of full-length p27Kip1 mRNA isoforms that interact with a ∼41-kDa protein and represses p27Kip1 expression. This CT-rich element and diffuse elements in the 3′ UTR regulate post-transcriptional expression of p27Kip1 at the level of translation. This is the first demonstration that HuR-dependent mRNA stability and HuR-independent mRNA translation plays a critical role in the regulation of post-transcriptional p27Kip1 expression.

Keywords: CDK (Cyclin-dependent Kinase), Cell Cycle, Protein Synthesis, RNA-binding Protein, RNA Turnover, RNA Interference (RNAi), Translation

Introduction

Cell cycle progression requires orderly activation of cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs)4 (1–3). The CDKs are regulated by dimerization with cyclins, inhibitory and activatory phosphorylation, and interaction with cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (4–8). The 27-kDa CDK inhibitor p27Kip1 interacts with cdk4-cyclin D and cdk2-cyclin E and/or cyclin A and plays a key role in integrating extracellular signals with the cell cycle machinery (9, 10). p27Kip1 is expressed at high levels in quiescent cells. Mitogenic stimulation down-regulates p27Kip1 expression while inducing the expression of cyclin D1 (9) and other G1 cyclins. This results in the activation of CDK-cyclin complexes, driving cells through the restriction point. Consistently, inhibition of p27Kip1 synthesis by antisense p27Kip1 oligonucleotides causes quiescent cells to enter the cell cycle without mitogen stimulation (10, 11). Expression of p27Kip1 is down-regulated in many cancers and predicts poor prognosis (12–20).

Several reports suggest that levels of p27Kip1 protein decrease during G0/G1/S progression with no apparent change in p27Kip1 mRNA levels (21–23). p27Kip1 is ubiquitinated and targeted for destruction by the Skp1/Cul1/Fbox (SCF) complex; however, the SCF complex appears to be activated in late G1 just before the G1/S transition, whereas the p27Kip1 level is reduced much earlier (9, 22, 24, 25). The SCF-independent degradation of p27Kip1 in early G1 has also been suggested (26). Several studies suggest that p27Kip1 expression is regulated at the level of translation in the G1 phase of the cell cycle (22, 23). One group has reported that basal and cell cycle-dependent translation of p27Kip1 is stimulated by the embryonic lethal abnormal visual system-like RNA-binding protein HuR binding to the 5′ UTR of p27Kip1 mRNA (27), whereas another reported that repression of internal ribosome entry site-dependent translation by HuR in proliferating but not quiescent cells is responsible for cell cycle-dependent expression of p27Kip1 (28). More recently, a p27Kip1 mRNA isoform with an upstream open reading frame has been proposed to be responsible for the cell cycle-dependent regulation of p27Kip1 expression (29). Finally, an endonuclease binding site in the 5′ UTR of p27Kip1 has been reported, suggesting that mRNA stability may also play a role in regulating the post-transcriptional expression of p27Kip1 (30). Surprisingly, although HuR plays a critical role in regulating the stability of several mRNAs (31–33), these studies failed to ascribe any role to HuR in regulating the stability of p27Kip1 mRNA. Given the critical role of p27Kip1 in the regulation of cell proliferation and cancer patients' outcome, understanding the regulation of its expression is of great interest. We therefore undertook a comprehensive study to investigate cis- and trans-regulatory elements that govern the post-transcriptional expression of p27Kip1.

We report here that the p27Kip1 gene generates several transcripts by utilizing alternative transcription start sites and/or polyadenylation signals. Several U-rich elements in the 5′ and 3′ UTRs of p27Kip1 mRNA interact with HuR, whereas a CT repeat region in the 5′ UTR interacts with a 41-kDa protein to regulate basal and cell cycle-dependent post-transcriptional expression of p27Kip1. Specifically, HuR binding elements regulate the stability of p27Kip1 mRNA without a discernible effect on its translation, whereas a CT repeat region, present only in the p27Kip1 mRNA isoforms transcribed from the proximal transcription start sites, interacts with the 41-kDa protein and suppresses translation of p27Kip1 mRNA. We further report that mitogen stimulation of quiescent cells does not reduce the stability of the p27Kip1 protein but inhibits its de novo synthesis by inhibiting the accumulation of the p27Kip1 mRNA. Taken together, our data demonstrate that mRNA stability plays a critical role in the post-transcriptional regulation of p27Kip1 expression and that the 5′ and 3′ UTRs of p27Kip1 have distinct roles in the basal and cell cycle-dependent regulation of p27Kip1 expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture

NIH 3T3 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% bovine calf serum (BCS). NIH 3T3-tTA cells were generated by transfecting NIH 3T3 cells with tetracycline-regulated transactivator (tTA) and selecting colonies by transient transfection with a reporter plasmid encoding for the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase gene, driven by the tetracycline response element and cytomegalovirus minimal promoter (34). These cells are referred to as NIH 3T3-tTA. Cells were rendered quiescent by reducing BCS to 0.2% for 36 h or to 0.1% for 24 h.

Measurement of p27Kip1 Synthesis and Stability

Cells were pulsed with 300 μCi/ml of [35S]methionine-cysteine (Met-Cys) for 1 h, washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline three times, lysed, and centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. Protein concentration was measured by the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad). Equal amounts of proteins (250 μg) were pre-absorbed with a 50-μl protein A-Sepharose slurry (50% w/w) on a rotary shaker for 1 h. The supernatant was incubated with 10 μg of anti-p27Kip1 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) overnight. The antibody-antigen complex was recovered with 20 μl of protein A beads for 1 h, washed three times, boiled in SDS sample buffer, and separated by 12% SDS-PAGE. Dried gels were exposed to a PhosphorImager and developed. For stability studies, quiescent cells were pulse-labeled with [35S]Met-Cys, washed three times, and incubated in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented either with 0.2 or 10% BCS and 1 mm Met-Cys for 4, 8, or 12 h. p27Kip1 was immunoprecipitated, separated, and visualized as described above.

Screening of cDNA Library

At day 10.5 a mouse embryonic cDNA library in pSPORT1 was obtained in 20 pools (kindly provided by Dr. Frank McKeon). Pools were screened by PCR, positive pools were titered, plated on 10 150-mm agar plates, and replica plated on nitrocellulose membranes. After lysis, denaturation in alkali, and neutralization, the DNA was cross-linked to membranes by UV light, and membranes were hybridized to the 32P-labeled p27Kip1 probe prepared by random labeling the 450-bp fragment of the coding region. Positive colonies were isolated and subjected to two more rounds of screening, and selected colonies were sequenced.

3′ and 5′ RACE

The 5′ and 3′ RACE procedure, described in detail under supplemental “Materials and Methods,” was carried out using the GeneRacer kit per the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogene).

Reporter Assays and Plasmid Construction, Transfection

Renilla luciferase and firefly luciferase genes were cloned into a bidirectional pBISA plasmid, created by modifying the pBI Tet Vector (Clontec). 5′ UTR (or fragments thereof) of p27Kip1 were cloned upstream from the firefly luciferase between MluI and NheI sites, whereas 3′ UTRs (or fragments thereof) were cloned between the ClaI and HindIII sites. Mouse p27Kip1 5′ or 3′ UTRs (and fragments thereof) cloned into pHGBf-luc/r-luc were obtained by PCR amplification using the primers or subcloning the digested cDNA fragments as described under supplemental “Materials and Methods.” All plasmids were sequenced to ensure that the intended fusions, mutations, and/or deletions were generated. The plasmids were transfected into NIH 3T3-tTA cells using Effectene (Qiagen) transfection reagent per the manufacturer's instructions. siRNA against HuR was obtained as a pool of five siRNAs from Dharmacon and transfected with Effectene reagent. For dual luciferase assay, cells were lysed using 1× passive lysis buffer, and the activity of reporter genes was measured using the dual luciferase assay kit (Promega Corp., Madison, WI) per the manufacturer's instructions.

RNA Isolation and Northern Blot Hybridization

Cells were washed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline and harvested. Poly(A) plus RNA was isolated using a Micro-Fast Track kit (Invitrogen), separated by formaldehyde-agarose gel electrophoresis, transferred to nylon membranes, and cross-linked by UV. The membrane was hybridized to specific antisense RNA probes synthesized with the Strip-EZ RNA synthesis kit using the ULTRA-hyb hybridization buffer per the manufacturer's instructions (Ambion).

Full-length firefly and Renilla luciferases and fragments of 18 S cDNA were cloned into pBS plasmid between PstI and XbaI sites, linearized with BbsI or XcmI to transcribe firefly and Renilla luciferases, respectively, with T3 polymerase. pBS containing an 18 S RNA fragment was digested with XbaI and transcribed using T7 polymerase. A 382-bp fragment (nucleotide 604–906) of mouse p27Kip1 was cloned into the PstI site of pBS by digesting pSPORT1 vector containing mouse p27Kip1 with PstI. The resulting plasmid was linearized with HindIII and transcribed with T3 polymerase.

Real Time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from NIH 3T3-tTA cells using the SV total RNA Isolation System (Promega). cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using the SuperScript3 First Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen). Real time PCR was performed on a light cycler instrument (Bio-Rad) using the fluorescent dye SYBR Green for relative quantification (IQ SYBR Green Supermix). Primers for the firefly luciferase were forward 5′-CGGTAAGACCTTTCGGTACT-3′ and reverse 5′-GATTACGTCGCCAGTCAAGT-3′; for the Renilla luciferase, forward 5′-GTAACGCGGCCTCTTCTTAT-3′ and reverse 5′-GCGCTACTGGCTCAATATGT-3′. The relative amount of reporter mRNAs in the samples was calculated from a standard curve obtained with cDNA from NIH 3T3-tTA cells transfected with pHGBf-luc/r-luc vector using 5 concentrations with dilution factor 5. Concentrations of the firefly or Renilla luciferase mRNAs (log dilutions) were plotted to the PCR cycle detected. The data of three independent analyses for each gene and sample were averaged (of triplicates). The ratio of firefly to Renilla luciferase mRNA in all transfections was normalized to the ratio calculated for the pHGBf-luc/r-luc vector.

Western Blot Analysis

Western blot analysis was carried out essentially as described (9).

UV Cross-linking and Immunoprecipitation of Protein-RNA Complexes

To transcribe radiolabeled p27Kip1 mRNA for cross-linking, p27Kip1 fragments were amplified by PCR and cloned into pBS vector between XhoI and SpeI sites or p27Kip1 cDNAs were manipulated to obtain the desired products. Details of the constructs generated and in vitro transcription are described under supplemental “Materials and Methods.”

In vitro transcribed [α-32P]UTP and CTP-labeled p27Kip1 mRNA fragments were gel-purified and incubated with NIH 3T3 (for mouse p27Kip1 mRNA fragments) or HeLa cell (for human p27Kip1) nuclear extracts in the presence or absence of and excess of cold p27Kip1 fragments or nonspecific RNA (β-actin ORF). After a 30-min incubation at room temperature, the reaction was cross-linked in UVP cross-linker for 20 min at 254 nm, and the RNA was digested with RNase A. The reaction mixture was separated by SDS-PAGE, and the cross-linked proteins were visualized by PhosphorImager. Immunoprecipitation of cross-linked proteins with monoclonal antibodies against a panel of RNA-binding proteins was carried out as described for p27Kip1, except that protein G-Sepharose beads were substituted for protein A-Sepharose beads.

In Vivo Cross-linking, Immunoprecipitation of Protein-RNA Complexes, and RNA Isolation

For immunoprecipitation analysis, NIH 3T3 cells were harvested and cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde for 45 min, washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline, and resuspended in RIPA buffer with a protease inhibitor mixture (50 mm Tris-HCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.05% SDS, 1 mm EDTA, and 150 mm NaCl). Cells were lysed by using 2-s pulses of ultrasound for 30 s followed by a 1-min incubation on ice 4 times. The lysates were centrifuged, and precleared supernatants were incubated with a complex of anti-HuR or anti-hnRNP-A1 antibodies and protein G-Sepharose beads (HuR 3A2 antibody or cyclin D1 antibody Santa Cruz sc-5261). After centrifugation, the beads were washed 6 times in high-stringency RIPA buffer with protease inhibitor mixture (50 mm Tris-HCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1 mm EDTA, 1 m NaCl, and 1 m urea). Beads were resuspended in Tris/dithiothreitol with RNasin, and incubated at 70 °C for 45 min to reverse the cross-links. The RNA was purified with TRIzol and reverse transcribed for real time reverse transcription-PCR. The primers used for amplification of the p27Kip1 mRNA were forward, 5′-TGGCTCTGCTCCATTTGACTGTCT-3′ and reverse, 5′-TCACGTTTGACATCTTCCTCCT-CG-3′, the primers used for amplification of 18 S RNA (as a specificity control) were forward, 5′-CGGCGACGACCCATTCGAAC-3′ and reverse, 5′-GAATCGAACCCTGATTCCCC-GTC-3′.

Measurements of Endogenous p27Kip1 or Reporter mRNA Half-life

NIH 3T3-tTA cells were transfected HuR siRNA with pHGBr-luc/f-luc plasmid in which firefly luciferase was fused to the 5′ UTR-2-(315–511) and 3′ UTR-2-(1110–2378) of the p27Kip1 mRNA with or without deletion of all three HuR binding sites (in the 5′ and 3′ UTR). Cells were treated with actinomycin D or vehicle 48 h after transfection and harvested at various times. Total RNA was isolated, and endogenous p27Kip1 or reporter mRNAs were quantified by real time PCR. The level of F-luc mRNA was normalized to R-luc mRNA and expressed as percent of F-luc mRNA in untreated cells.

Sucrose Density Gradient Centrifugation of Polysomes

NIH 3T3-tTA cells transfected with pHGBr-luc/f-luc or pHGBr-luc/f-luc plasmids in which firefly luciferase was fused to 5′ UTR-2-(315–511) and 3′ UTR-2-(1110–2378) of p27Kip1 mRNA with or without deletion of all three HuR binding sites (in the 5′ and 3′ UTR). Cells were rendered quiescent, half were subsequently serum stimulated, and all were treated with 100 μg/ml of cycloheximide 5 min before lysis. Cytoplasmic extracts were prepared as previously described (35). Samples were centrifuged using a Beckman-Coulter SW-41 swinging bucket rotor (Fullerton, CA) in a Beckman-Coulter Optima ultracentrifuge at 32,000 × g for 2 h 30 min at 4 °C, with “slow” acceleration and no braking. Gradients were analyzed with the Brandel gradient fractionators and a SYR-101 syringe pump (Gaithersburg, MD), using a 5-mm path length flow cell and 254-nm filters. Profiles were recorded using an ISCO UA-6 UV detector (Lincoln, NE), all fractions were collected and total RNA was purified from each fraction with TRIzol and prepared for real time reverse transcription-PCR.

RESULTS

Regulation of p27Kip1 Expression and de Novo Synthesis by Extracellular Signals

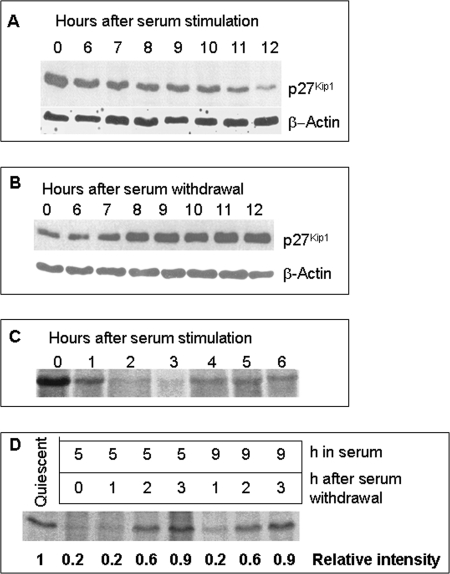

To monitor expression of p27Kip1 through G0/G1/S phase transition, quiescent cells were serum-stimulated and expression of p27Kip1 was monitored by Western blot. The level of the p27Kip1 protein dropped steadily as cells progressed from G0 to S, reaching minimum levels just before entry into the S phase (Fig. 1A). In contrast, serum withdrawal from already stimulated cells led to a progressive increase in the level of p27Kip1 protein (Fig. 1B). In cells labeled with [35S]Met-Cys at hourly intervals starting 1 h before serum addition, de novo synthesis of p27Kip1 decreased rapidly upon serum stimulation and remained constant after the first 2 h following serum stimulation (Fig. 1C). If de novo synthesis of p27Kip1 is regulated by extracellular signals, the serum withdrawal from already stimulated cells should increase de novo synthesis of p27Kip1. Quiescent cells were stimulated with serum for 5 or 9 h, washed, and incubated in serum-free medium, and de novo p27Kip1 synthesis was measured by a 1-h pulse labeling at hourly intervals starting immediately after serum withdrawal. As expected, de novo synthesis of p27Kip1 in cells stimulated with serum for 5 or 9 h was significantly lower (∼20% of quiescent) compared with quiescent cells (Fig. 1D). Serum withdrawal from these stimulated cells increased p27Kip1 synthesis only in the second hour of labeling (∼60% of quiescent) and reached similar levels observed in quiescent cells in the third hour (Fig. 1D). These data confirm that extracellular signals regulate de novo synthesis of p27Kip1.

FIGURE 1.

Regulation of p27Kip1 expression by extracellular signals. A and B, quiescent NIH 3T3 cells were stimulated with 10% serum and harvested at the indicated times (A) or were first serum-stimulated for 9 h, then serum was withdrawn and cells were harvested at the indicated times after serum withdrawal (B). 20 μg of protein was separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-p27Kip1 antibody. C, quiescent NIH 3T3 cells were incubated with [35S]Met-Cys before serum stimulation or at hourly intervals immediately after serum stimulation, lysed, and 200 μg of protein was immunoprecipitated with anti-p27Kip1 specific antibodies. D, quiescent NIH 3T3 cells were serum-stimulated for 5 or 9 h, washed with serum-free medium, and pulse-labeled with [35S]Met-Cys without serum at hourly intervals for 1 h. Cells were harvested at the first, second, or third hour after serum withdrawal, and lysates were prepared and immunoprecipitated with anti-p27Kip1 specific antibodies. The relative intensity of each band is shown in the bottom (setting the intensity of quiescent sample arbitrarily as 1).

Stability of p27Kip1 Protein Does Not Change at G0/G1 Transition and through G1

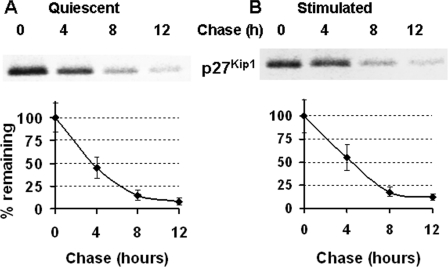

To determine the role of protein turnover in the regulation of post-transcriptional expression of p27Kip1, we labeled quiescent NIH 3T3 cells with [35S]Met-Cys followed by chasing with cold Met-Cys in the presence or absence of 10% BCS. As shown in Fig. 2, A and B, stability of p27Kip1 in quiescent and serum-stimulated cells is fairly similar through the G1 phase of the cell cycle, with a calculated half-life of about 4 h.

FIGURE 2.

Half-life of p27Kip1 is constant in G0 and through the G1 phase of the cell cycle. Quiescent NIH 3T3 cells were labeled with [35S]Met-Cys for 2 h, washed, and chased for 4, 8, or 12 h in the absence (A) or presence (B) of 10% bovine calf serum. Samples were harvested at the indicated times, and metabolically labeled p27Kip1 was immunoprecipitated, separated by SDS-PAGE, and visualized and quantified by PhosphorImager. Lower panels are the graphical representation of data.

Mice and Humans Express Multiple p27Kip1 mRNAs Isoforms

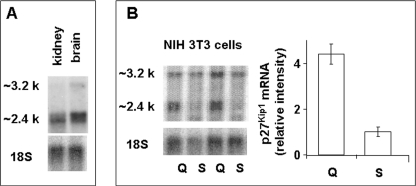

To study cis-regulators of p27Kip1 expression we cloned full-length p27Kip1 cDNA by screening a mouse cDNA library and amplifying mouse and human embryonic cDNA, which should contain all p27Kip1 isoforms, by a modified 5′ and 3′ RACE procedure. Mice express p27Kip1 mRNA isoforms that differ in their 5′ and 3′ UTRs. Different 5′ UTRs are products of alternative transcription start sites, whereas two prevalent 3′ UTRs of 1,268 and 1,988 nucleotides result from utilization of alternative polyadenylation sites. The expression of different p27Kip1 mRNA isoforms was confirmed by Northern blot hybridization of mouse brain and kidney tissue as well as of NIH 3T3 cells (Fig. 3, A and B). We also obtained one 3′ RACE product with a longer 3′ UTR that may have resulted from both alternative splicing and polyadenylation. This p27Kip1 mRNA isoform must be expressed at very low levels, apparent from its undetectable levels by Northern blot hybridization with probes specific to unique regions of this mRNA. The sequences of mouse p27Kip1 isoforms are provided under supplemental materials. Full-length mouse p27Kip1 cDNA sequence is deposited into GenBank. Surprisingly, accumulation of p27Kip1 mRNA was strongly dependent on the stage of the cell cycle; higher in quiescent and lower in S phase cells (Fig. 3B).

FIGURE 3.

Mouse cells and tissues express multiple isoforms of p27Kip1 mRNA. Poly(A) plus RNA was isolated from mouse kidney and brain (A) or NIH 3T3 cells (B) using the micro fast-track II kit, separated by formaldehyde-agarose gel, and hybridized with radiolabeled p27Kip1-specific antisense RNA probe. The densitometric data were obtained by scanning 3.2- and 2.4-kb bands and adding both for each line. Mean ± S.D. of six quiescent and six serum-stimulated samples are shown. Levels or p27Kip1 mRNA is serum-stimulated cells was arbitrarily set as 1. Q, quiescent; S, serum-stimulated.

Human cells also express several p27Kip1 mRNA isoforms that differ in their 5′ UTR but not coding region or 3′ UTR. The different 5′ UTRs appear to be the product of alternative transcription start sites. The sequence of human p27Kip1 mRNA did not differ from those already deposited in GenBank.

Unique Sequences in the 5′ and 3′ UTR of p27Kip1 mRNA Determine the Basal and Cell Cycle-dependent Expression

Previous reports indicate that the coding region of p27Kip1 mRNA does not regulate post-transcriptional expression of the p27Kip1 protein (27). We therefore concentrated our efforts on understanding the role of the 5′ and 3′ UTRs on the basal and cell cycle-dependent expression of p27Kip1. Toward this end we fused the 5′ and 3′ UTRs of p27Kip1 mRNA either singularly or in various combinations to the firefly luciferase ORF in pHGBf-luc/r-luc plasmid (control plasmid, see “Materials and Methods” and supplemental Fig. 1A). Renilla luciferase mRNA, transcribed from the same promoter but in the opposite direction and flanked by the same polyadenylation signal, served as an internal control. We used the ratio of firefly to Renilla luciferase activity as the readout. Our constructs yielded mRNA products of the expected sizes as confirmed by Northern blot hybridization (supplemental Fig. 1B). Because transcription of both firefly and Renilla luciferases in our constructs is driven by the same promoter-enhancer complex, and polyadenylation is controlled by the same polyadenylation signal, changes in the levels of firefly luciferase mRNA as compared with Renilla luciferase mRNA are likely to be due to the differential stability of the firefly luciferase mRNAs fused to various p27Kip1 5′ and 3′ UTRs. Similarly, changes in the activity of the firefly luciferase without concomitant change in the level of its mRNAs (all normalized to Renilla luciferase) are likely to be due to differential translatability of the firefly luciferase mRNAs imparted to them by the fused p27Kip1 fragments.

To identify cis-acting post-transcriptional regulators of p27Kip1 expression, cells were transfected with various constructs, rendered quiescent, and after 24 h one-half was serum stimulated for an additional 12 h. Quiescent and serum-stimulated cells were lysed and reporter activity was assayed by dual luciferase assay (DLR), whereas reporter mRNA levels were determined by real time PCR. Real time PCR was preferred to Northern blot hybridization because fewer cells were required. The longest 5′ UTR was called full-length 5′ UTR (FL-5′ UTR). For 3′ UTR analysis we focused on the two predominant 3′ UTRs, the shorter one (1110–2378) was called 3′ UTR-S and the longer one (1110–3108) 3′ UTR-L for simplicity (see supplemental Fig. S1C for the schematic depiction of 5′ and 3′ UTRs used in these studies).

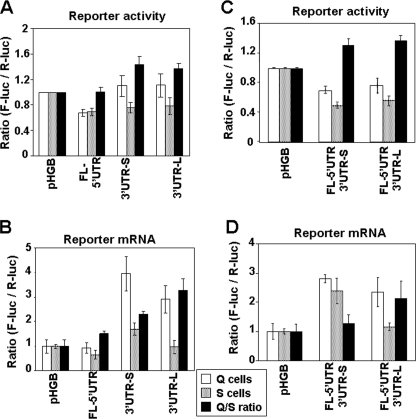

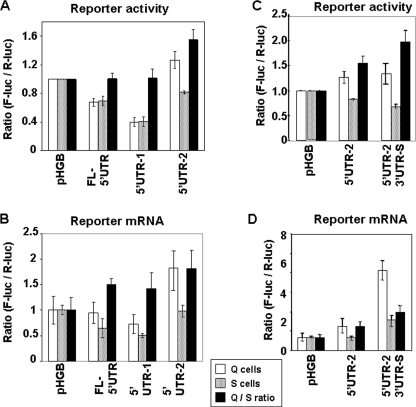

The fusion with full-length p27Kip1 5′ UTR reduced the firefly luciferase expression to a similar extent (about 30%) in both quiescent and serum-stimulated cells compared with control plasmid pHGBf-luc/r-luc (Fig. 4A), with a smaller change in the levels of reporter mRNA (Fig. 4B). These data suggest that the full-length 5′ UTR of p27Kip1 may reduce basal translation of p27Kip1, however, the effect of full-length 5′ UTR on reporter gene expression is rather modest. Fusion of either 3′ UTR-S or 3′ UTR-L of p27Kip1 with firefly luciferase showed two interesting effects. 1) Both 3′ UTR-S and 3′ UTR-L fusions elevated the expression of firefly luciferase mRNA (normalized for Renilla luciferase mRNA) compared with its expression from the control plasmid without a corresponding increase in reporter activity. This finding suggests that both p27Kip1 3′ UTRs suppress basal translation while stabilizing the mRNA. 2) Fusion with either 3′ UTR-S and 3′ UTR-L resulted in a consistent increase in the firefly/Renilla ratio in quiescent compared with serum-stimulated cells. This cell cycle-dependent effect was accounted for by the more pronounced increase in the firefly luciferase mRNA in quiescent compared with serum-stimulated cells. These data indicate that 3′ UTRs of p27Kip1 suppress basal translation and that mRNA accumulation may regulate the cell cycle-dependent p27Kip1 expression. Combined fusion of p27Kip1 5′ UTR and 3′ UTR-S or 3′ UTR-L to firefly luciferase ORF yielded similar results (Fig. 4, C and D). Because the transcription and polyadenylation of both firefly and Renilla luciferase in all constructs is controlled by the same heterologous promoter and polyadenylation signal, both the basal and cell cycle-dependent changes in the firefly luciferase mRNA levels are likely due to differential stability of the reporter mRNAs imparted to them by the fused p27Kip1 mRNA fragments. Taken together, these data suggest that p27Kip1 UTRs contain translation-repressive elements and that mRNA stability may play a role in the post-transcriptional regulation of p27Kip1 expression.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of mouse p27Kip1 5′ and 3′ UTRs on the expression of reporter gene. p27Kip1 full-length 5′ UTR and two 3′ UTRs (see ”Results“) were fused to the ORF of firefly luciferase using Renilla luciferase as an internal control in pHGBf-luc/r-luc plasmid. The plasmids with singular fusion of 5′ UTR and 3′ UTR (A and B) or combined fusion of 5′ UTR with either 3′ UTRs (C and D) were transfected into the NIH 3T3-tTA cells. The cells were rendered quiescent, and one-half were stimulated by addition of 10% BCS for 12 h and harvested; the relative expression of firefly and Renilla luciferase reporters was determined by DLR assay (A and C) and relative level of their respective mRNAs determined by real time PCR (B and D). Firefly luciferase activity and mRNA in each sample were normalized to those of Renilla luciferase (in triplicate). All values were divided by those obtained from the cells transfected with the control vector (pHGBf-luc/r-luc). The results are the mean ± S.E. of at least three independent experiments. See supplemental Fig. 1C for the schematic depiction of the 5′ and 3′ UTRs used in these studies. Q, quiescent; S, serum-stimulated, Q/S, quiescent/serum-stimulated.

To determine whether some elements of the p27Kip1 5′ UTR may have more frank effects on reporter mRNA accumulation and/or translation, we fused two fragments of p27Kip1 5′ UTR (depicted in supplemental Fig. S1C) to firefly luciferase ORF. As shown in Fig. 5A, fusion of nucleotides 1–314 (termed 5′ UTR-1) to firefly luciferase ORF reduced reporter activity more than the FL-5′ UTR when compared with control plasmid. This effect appears to be at least in part due to the reduced accumulation of firefly luciferase mRNA (Fig. 5B). Fusion of a 5′ UTR produced from a distal transcription start site (nucleotides 315–514, termed 5′ UTR-2) to firefly luciferase ORF increased reporter gene expression as well as mRNA accumulation compared with fusion of FL-5′ UTR or 5′ UTR-1 (Fig. 5, A and B). These effects were significantly more pronounced in quiescent than in serum-stimulated cells, resulting in a cell cycle-dependent increase in reporter activity. Taken together, these findings suggest that the first 314 nucleotides of the p27Kip1 5′ UTR may contain elements that reduce translational efficiency and/or accumulation of p27Kip1 mRNA. Furthermore, RNA elements present between nucleotides 315 and 511 seem to stabilize p27Kip1 mRNA.

FIGURE 5.

Further delineation of cis-regulatory elements in 5′ of mouse p27Kip1. NIH 3T3 cells were transfected with various constructs in which different fragments of mouse p27Kip1 5′ UTR were fused to firefly luciferase ORF alone (A and B) or in combination with 3′ UTRs (as described in the legend to Fig. 3), reporter activity was determined by DLR assay (A and C), and reporter mRNA levels were determined by real time PCR (B and D). The results are the mean ± S.E. of at least three independent experiments. See supplemental Fig. 1C for the schematic depiction of the 5′ and 3′ UTRs used in these studies.

Combined fusion of the p27Kip1 5′ UTR-2 (nucleotides 315–514) and 3′ UTR-S to firefly luciferase ORF increased the reporter activity in quiescent but not in the serum-stimulated cells, resulting in cell cycle-dependent regulation of reporter expression (Fig. 5C). At the mRNA level, this fusion elevated the levels of firefly luciferase mRNA significantly in quiescent cells and significantly (but to a lesser extent) in serum-stimulated cells (Fig. 5D). These data indicate that the cell cycle-dependent expression of the reporter shown in Fig. 5C is due to cell cycle-dependent changes in the accumulation of reporter mRNA. Importantly, the increase in the reporter mRNA levels with this combined fusion is not matched by a concordant increase in reporter activity, confirming once more that the 3′ UTR suppresses translation of p27Kip1 mRNA. Taken together, our findings indicate that both basal and cell cycle-regulated expression of p27Kip1 are highly dependent on the isoforms (5′ and 3′ UTR combinations) of the p27Kip1 mRNA, and that mRNA stability may play a role in the post-transcriptional regulation of p27Kip1 expression. This is consistent with the cell cycle-dependent accumulation of p27Kip1 mRNA shown in Fig. 3B (and see below).

Our findings indicate that 3′ UTRs of p27Kip1 suppress mRNA translation, because they reduce reporter activity while inducing accumulation of p27Kip1 mRNA. In an attempt to identify regions of p27Kip1 3′ UTR responsible for the suppression of reporter mRNA translation, we fused different fragments of the p27Kip1 3′ UTR to firefly luciferase ORF and determined their effect on reporter gene activity. These fragments were 1) 1110–1609 (shared by all p27Kip1 mRNAs); 2) 1609–2478 (shared by both 3′ UTR-S and 3′ UTR-L); 3) 1609-3104; 4) 2470–3104; and 5) 2754–3104 (4 and 5 are confined to 3′ UTR-L). However, we could not isolate a region of 3′ UTRs responsible for repression of reporter activity (supplemental Fig. S4). These data suggest that either multiple elements of p27Kip1 3′ UTR act together, or the overlapping sequences of the tested fragments were responsible for the repression of reporter gene expression by full-length p27Kip1 3′ UTRs. It is also possible that the global-fold of mRNA, rather than specific sequences, is responsible for the repression of p27Kip1 mRNA translation.

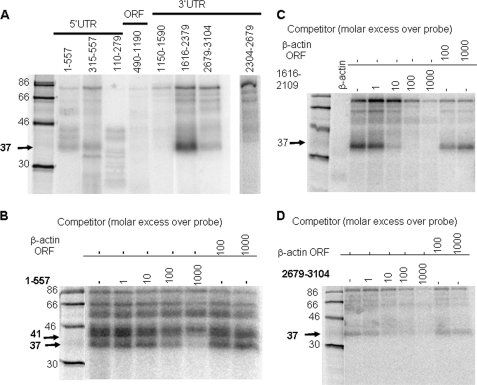

5′ and 3′ UTRs of p27Kip1 mRNA Specifically Interact with Cellular Proteins

In an effort to determine whether the post-transcriptional regulation of p27Kip1 expression by 5′ and 3′ UTRs is mediated through their interactions with cellular proteins, we cross-linked overlapping radiolabeled fragments of p27Kip1 mRNA to NIH 3T3 cell nuclear extracts. We detected no interaction between the coding region of p27Kip1 mRNA and cellular proteins (Fig. 6A). The full-length 5′ UTR cross-linked with at least four proteins. However, competition with excess cold mRNA indicated that only two of these interactions, with 37- and 41-kDa proteins, were specific (Fig. 6B). Similarly, we identified nucleotides 1616–2109 of 3′ UTR as a region that specifically cross-linked to a 37-kDa protein (Fig. 6, A and C). Cross-linking gradually smaller regions of p27Kip1 5′ UTR to cell extracts showed that the binding region of the 41-kDa protein was localized between nucleotides 189 and 269, a CT-repeat region that could not be narrowed any further (supplemental Fig. S2A). The binding site for the 37-kDa protein was similarly shown to be a U-rich element ending with a run of 11 Us (nucleotide 426–469). This element was necessary and sufficient for binding of the 37-kDa protein to the 5′ UTR of p27Kip1 mRNA (supplemental Fig. S2A), and the run of Us (nucleotides 459–469) was required for this interaction (supplemental Fig. S3B). The binding site for the 37-kDa protein in the 3′ UTR was localized to two regions: one between bases 1619 and 1647, and the other between 1804 and 1832, both U-rich elements (supplemental Fig. S2B). A 37-kDa protein also interacts with a site in the unique region of 3′ UTR-L (Fig. 6, A and D). This weaker binding site was mapped by further deletion analysis to a region between nucleotides 2819 and 2856, which make up another U-rich element (data not shown). Because binding sites for the 37-kDa protein in the 5′ and 3′ UTR were similarly U-rich, we suspected that the same 37-kDa protein was interacting with the 5′ and 3′ UTR of p27Kip1. Results of our cross-competition experiments (i.e. competing binding of labeled p27Kip1 3′ UTR to cell extracts with cold p27Kip1 5′ UTR) indicate that the same 37-kDa protein binds to both 5′ and 3′ UTR elements of p27Kip1 mRNA (supplemental Figs. S3, B and C).

FIGURE 6.

Interaction of cellular proteins with p27Kip1 mRNA. A, radiolabeled fragments of p27Kip1 5′ and 3′ UTR were UV cross-linked with nuclear extracts incubated with RNase A, and cross-linked complexes were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by PhosphorImager. B, radiolabeled full-length p27Kip1 5′ UTR was UV cross-linked to nuclear extracts in the presence of increasing concentrations of cold full-length p27Kip1 5′ UTR or β-actin mRNA. C and D, radiolabeled 3′ UTR fragments (nucleotides 1579–2304 (C) or nucleotides 2679–3104 (D)) were UV cross-linked to nuclear extracts in the presence of the increasing concentrations of the same cold RNA fragments or β-actin mRNA as in B.

To rule out experimental artifacts, we incubated three different probes with or without cell extracts, probes incubated with extracts were either cross-linked by UV or not cross-linked. As shown in supplemental Fig. S3D all tested probes were completely digested by RNase and no radioactive band was observed unless the probes were incubated with cell extracts and cross-linked by UV (supplemental Fig. S3D).

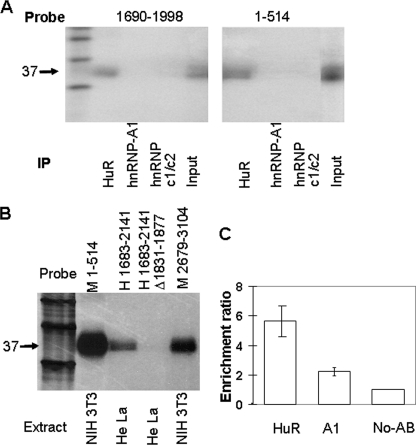

The 37-kDa p27Kip1 mRNA-binding Protein Is HuR

Two studies suggested that the embryonic lethal abnormal visual-like RNA-binding protein HuR binds to 5′ UTR of human p27Kip1 mRNA (27, 28). Because in our studies U-rich elements in both the 5′ and 3′ UTRs of mouse p27Kip1 also interacted with a 37-kDa protein, we suspected this protein was HuR. We cross-linked cell extracts to a radiolabeled p27Kip1 5′ UTR and a fragment of p27Kip1 3′ UTR (nucleotides 1690–1998) and immunoprecipitated cross-linked proteins with antibodies specific to HuR, hnRNPc1/c2, and hnRNP-A. hnRNPc1/c2 and hnRNP-A were tested because they were thought to interact with the 5′ UTR of human p27Kip1 mRNA (27, 28). Anti-HuR antibodies immunoprecipitated only the 37-kDa protein, indicating that this protein is HuR (Fig. 7A). Anti-hnRNPc1/c2 or hnRNP-A antibodies did not react with any cross-linked proteins. Anti-HuR antibodies also immunoprecipitated a 37-kDa protein that interacts with a unique region of 3′ UTR-L (Fig. 7B). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of HuR binding to both the 5′ and 3′ UTRs on the same mRNA.

FIGURE 7.

Identification of the 37-kDa protein that interacts with p27Kip1 mRNA. A, radiolabeled 5′ (nucleotides 1–514, right panel) and 3′ UTR (nucleotides 1690–1998, left panel) fragments of p27Kip1 mRNA were UV cross-linked to NIH 3T3 cell extracts, and cross-linked proteins were immunoprecipitated with antibodies specific to HuR, hnRNPc1/c2, and hnRNP-A. B, indicated fragments of radiolabeled mouse and human p27Kip1 mRNA were UV cross-linked to NIH 3T3 and HeLa cell extracts, respectively. All cross-linked reactions were digested with RNase A and immunoprecipitated with an anti-HuR antibody, separated by SDS-PAGE, and visualized by PhosphorImager. M, mouse; H, human. C, NIH 3T3 cells were incubated with formaldehyde to cross-link RNA-protein complexes, washed, suspended in RIPA buffer, and lysed by sonication. Lysates were cleared by incubation with protein G-agarose beads, incubated with complexes of protein G-agarose beads/anti-HuR, anti-RNP/A1 antibodies, or beads alone. After 6 washes in high stringency RIPA buffer protein/RNA cross-links were reversed, RNA was isolated, reverse transcribed and amplified by real time PCR using p27Kip1 or 18 S RNA-specific primers. The ratio of p27Kip1/18 S RNA in RNA pulled down by beads alone was taken as 1, and the ratio of the p27Kip1/18 S RNA in RNA pulled by antibodies was divided by this ratio to obtain the enrichment ratio.

To determine whether human p27Kip1 mRNA also contains HuR binding sites in both 5′ and 3′ UTRs, we cross-linked radiolabeled human p27Kip1 3′ UTR fragments with HeLa cells nuclear extracts. We determined that a 37-kDa protein interacted with the 3′ UTR of human p27Kip1 mRNA between nucleotides 1683 and 2132 and as demonstrated by immunoprecipitation of cross-linked products with anti-HuR antibodies this 37-kDa protein was HuR (Fig. 7B). To more precisely define the HuR binding site in the 3′ UTR of human p27Kip1, we searched for potential HuR binding sites (UA-rich elements). We located one such element between nucleotides 1832 and 1867 in the 3′ UTR of human p27Kip1. Deletion of this UA-rich element abolished the binding of HuR to the 3′ UTR of human p27Kip1, confirming that HuR binds to the 3′ UTR of human p27Kip1 mRNA. Taken together, these data demonstrate unequivocally that HuR interacts with both 5′ and 3′ UTRs of human p27Kip1 mRNA.

To determine whether p27Kip1 mRNA does interact with HuR in vivo not just in vitro, we studied interaction of HuR with the endogenous p27Kip1 mRNA by in vivo cross-linking and immunoprecipitation of HuR-p27Kip1 RNP complexes. Briefly NIH 3T3 cells were incubated with 1% formaldehyde to cross-link in vivo RNA-protein complexes that were then immunoprecipitated with anti-HuR antibodies. As a control we utilized anti-RNPA1 antibodies or protein G-agarose beads alone. After immunoprecipitation, we reversed the in vivo cross-links, reverse transcribed the mRNA using random hexamers, and amplified p27Kip1 mRNA and 18 S RNA by real time PCR. We then calculated the enrichment of the p27Kip1 mRNA in each group normalizing to 18 S RNA. As shown in Fig. 7C, p27Kip1 mRNA was enriched ∼6-fold in RNP complexes pulled down by anti-HuR antibodies demonstrating clearly that HuR interacts with p27Kip1 mRNA in vivo. This in vivo interaction may involve one or more HuR binding sites identified in vitro.

HuR Regulates Stability and Accumulation of Reporter mRNA Fused to p27Kip1 UTRs

We have demonstrated that HuR interacts with one site in the 5′ UTR, two sites in 3′ UTR-S, and an additional site in 3′ UTR-L of p27Kip1 mRNA in vitro, and that at least some of these interactions also occur in vivo. Previously Millard et al. (27) reported that a HuR binding site in the 5′ UTR of human p27Kip1 was required for the efficient translation of p27Kip1 mRNA, whereas Kullmann et al. (28) reported that HuR binding suppressed internal ribosome entry site-dependent translation of p27Kip mRNA in proliferating cells. Interestingly, despite the well known role of HuR in regulating mRNA stability, neither group reported any role for HuR in regulating p27Kip1 mRNA accumulation.

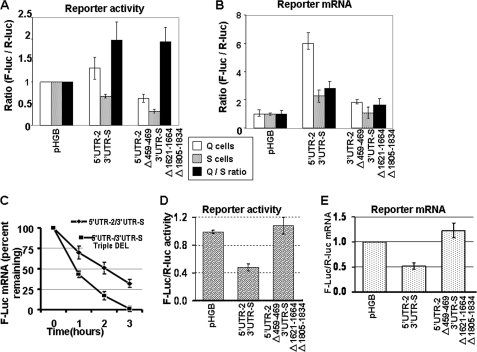

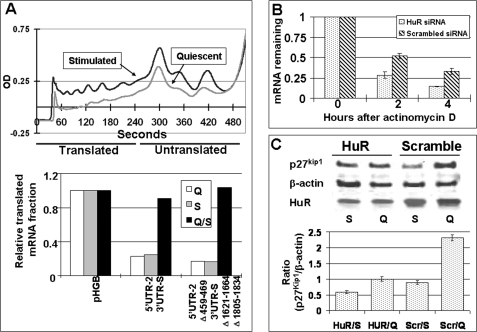

To define the role of HuR in regulating post-transcriptional expression of p27Kip1, we fused the 5′ UTR-2 (nucleotides 315–511) of p27Kip1 (which lacks the binding site for the 41-kDa protein) and 3′ UTR-S together with firefly luciferase ORF, deleting the HuR binding sites singularly or in combinations (one, two, or three deletions). Deletion of HuR binding sites allows us to directly determine the role HuR in post-transcriptional expression of p27Kip1. As shown in supplemental Fig. 5, B and C, deletion of any one or two HuR binding sites (leaving at least one site intact) had no significant effect on reporter activity. Deletion of all three HuR binding sites, on the other hand, resulted in significantly reduced activity of firefly luciferase (Fig. 8A). To determine whether deletion of all HuR binding sites reduced activity of the firefly luciferase by interfering with reporter mRNA accumulation or translation, we measured firefly and Renilla luciferase mRNA levels by real time PCR. As shown in Fig. 8B, deletion of all three HuR binding sites resulted in a dramatically reduced accumulation of firefly luciferase mRNA, which accounted for the reduced firefly luciferase activity. To determine directly if HuR regulates accumulation of reporter mRNA fused to the 5′ and 3′ UTRs of p27Kip1 mRNA, by increasing its stability we measured firefly and Renilla luciferase mRNA levels in transfected cells after actinomycin-D treatment. As shown in Fig. 8C, deletion of all three HuR binding sites significantly reduces the stability of the firefly luciferase mRNA. These data clearly indicate that HuR regulates post-transcriptional expression of p27Kip1 by modulating the stability and thereby accumulation of p27Kip1 mRNA.

FIGURE 8.

Deletion of HuR binding sites abrogates gene expression by reducing mRNA accumulation and stability. A, 5′ UTR-2-(315–511) and 3′ UTR-2-(1110–2378) of p27Kip1 mRNA with or without deletion of all three HuR binding sites in the 5′ and 3′ UTR were fused to firefly luciferase in the pHGBr-luc/f-luc plasmid, and these plasmids were transfected into NIH 3T3-tTA cells. Cells were treated as described in the legends to Figs. 3 and 4, and DLR was performed to determine the relative reporter activity. B, RNA was purified from the cells described in A, total RNA was isolated, and reporter mRNAs were quantified by real time PCR. C, cells transfected with reporter constructs described in A were cultured with actinomycin D for the indicated times. Total mRNA was isolated and reporter mRNAs were quantified by real time PCR. The level of F-luc mRNA was normalized to R-luc mRNA and expressed as % of F-luc mRNA in cells not treated with actinomycin D. D and E, the constructs in A were co-transfected into the cells with a pool of siRNA targeting HuR or control siRNA targeting green fluorescent protein. Cells were cultured for 48 h, lysates were assayed for luciferase activity by DLR (D) or total RNA was isolated, and reporter mRNAs were amplified by real time PCR. For each plasmid F-luc/R-luc activity (D) or mRNA levels (E) in HuR siRNA-transfected cells was divided by the same in the control siRNA-transfected cells. This ratio was arbitrarily set to 1 for the pHGBr-luc/f-luc plasmid. The experiment was repeated at least three times. Bars indicate S.D.

To demonstrate further that HuR regulates accumulation of the p27Kip1 mRNA we investigated the effect of HuR knockdown on the accumulation of reporter mRNA fused to the p27Kip1 5′ and 3′ UTRs with or without deletion of HuR binding sites. Expression of HuR mRNA was knocked down using a pool of siRNAs targeting HuR. The knockdown efficiency ranged from 60 to 75% as determined by real time PCR. Cells were transfected with three different plasmid: 1)pHGBf-luc/r-luc (control), 2) pHGBf-luc/r-luc in which firefly luciferase ORF was fused to WT 5′ UTR-2 and 3′ UTR-S, which contains all three HuR binding sites, and 3) pHGBf-luc/r-luc in which firefly luciferase ORF is fused to the 5′ UTR-2 and 3′ UTR-S with the deletion of all three HuR binding sites. The firefly/Renilla activity was measured by DLR assay and firefly and Renilla luciferase mRNA levels were determined by real time PCR and the ratio of the two were calculated. If HuR does indeed stabilize p27Kip1 mRNA, then knocking down HuR expression should reduce firefly luciferase reporter gene activity and mRNA accumulation in the cells co-transfected with the construct in which firefly luciferase ORF is fused to the wild type p27Kip1 5′ and 3′ UTR (compared with mock siRNA). For quantification of data the effect of HuR knocked down on expression of reporter mRNA in cells transfected with the plasmids where firefly luciferase ORF is fused to the p27Kip1 5′ and 3′ UTR was normalized for the effect of HuR knocked down on expression of reporters in the cells transfected with control plasmid. This was done to account for the nonspecific effects of HuR knocked down on mRNA metabolism.

As shown in Fig. 8D, HuR knockdown cells express significantly less firefly luciferase fused to the WT 5′ UTR-2 and 3′ UTR-S of the p27Kip1 mRNA compared with firefly luciferase expression from cells transfected with mock siRNA. In contrast, knocking down HuR expression had no effect on the expression of firefly luciferase when firefly luciferase ORF was fused to 5′ UTR-2 and 3′ UTR-S with deletion of all three HuR binding sites. Similarly, HuR knockdown reduced the firefly luciferase mRNA accumulation if it was fused to WT 5′ UTR-2 and 3′ UTR-S of p27Kip1 mRNA but had no effect on the levels of luciferase mRNA fused to the 5′ UTR-2 and 3′ UTR-S if all three HuR binding sites were deleted (Fig. 8E). Note that for Fig. 8, D and E, the data represent the relative F-luc/R-luc activity (D) or mRNA levels (E) in HuR siRNA-transfected cells divided by the same in the mock siRNA-transfected cells (for each plasmid). This ratio was arbitrarily set to 1 for the pHGBr-luc/f-luc plasmid, corrected accordingly for the two plasmids in which the firefly luciferase ORF was fused to the 5′ UTR-2 and 3′ UTR-S of p27Kip1 mRNA (with or without deletion of HuR binding sites). Taken together the data presented in the Fig. 8, A–E, demonstrate that HuR regulates post-transcriptional p27Kip1 expression by stabilizing p27Kip1 mRNA. To further confirm these findings, cytoplasmic extracts of the cells transfected with pHGBf-luc/r-luc (control), pHGBf-luc/r-luc in which the firefly luciferase ORF fused to WT 5′ UTR-2 and 3′ UTR-S, which contains all three HuR binding sites, and pHGBf-luc/r-luc in which firefly luciferase ORF is fused to the 5′ UTR-2 and 3′ UTR-S with deletion of all three HuR binding sites and subjected sucrose density gradient centrifugation and eluted with constant monitoring (Fig. 9A, top panel). We also collected fractions for quantitative analysis. The amount of p27Kip1 mRNA in each fraction was quantified as the fraction of total p27Kip1 mRNA in all fractions. Based on UV profiles, fractions 1–4 (0–240 s) were considered translated, whereas fractions 5–9 (240–540 s) were considered untranslated fractions. Fig. 9A, lower panel, shows that the translated fractions (0–240 s in Fig. 9A) of the cell transfected with pHGBf-luc/r-luc in which the firefly luciferase ORF is fused to the 5′ UTR-2, and the 3′ UTR-S contained less firefly luciferase mRNA compared with the same fractions of cells transfected with just pHGBf-luc/r-luc. Furthermore, this differential distribution of firefly luciferase mRNA was independent of the HuR binding site deletion or the cell cycle stage of the cells. These data are consistent with reporter studies that indicates that elements in the UTRs of the p27Kip1 mRNA reduce translational efficiency (see for example, Figs. 4, 5, and 7) and that the HuR binding site have little, if any, effect on the translation of the reporter mRNA (see for example, Fig. 8).

FIGURE 9.

The biological importance of HuR-p27Kip1 mRNA interactions. A, NIH 3T3-tTA cells were transfected with the three reporter constructs shown in Fig. 8, cytoplasmic extracts were separated by sucrose density gradient centrifugation and eluted by constant monitoring at 254 nm. Fractions were collected every minute for RNA purification and PCR analysis. Top panel shows a representative gradient of quiescent and serum-stimulated cells. Total RNA prepared from each fraction was amplified using F-luc- and R-luc-specific primers by real time PCR and reporter mRNAs were quantified. The amount of F-luc mRNA (normalized to R-luc mRNA) in the translated fractions (0–240 s) was divided by the amount of total-luc mRNA (translated + untranslated fractions) and graphed (lower panel). Q, quiescent; S, serum stimulated; Q/S, quiescent/serum stimulated. B, NIH 3T3 tTA cells transfected with HuR siRNA or scrambled siRNA were treated with actinomycin D and lysed 0, 2, or 4 h after treatment. Total RNA was isolated and p27Kip1 mRNA was quantified by real time PCR. The amount of p27Kip1 mRNA in the 0-h sample was arbitrarily set at 1. The graph shows mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments. C, NIH 3T3 tTA cells were transfected with HuR siRNA or scrambled siRNA, rendered quiescent. One-half of the quiescent cells were serum stimulated for 12 h. Cell were lysed, proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, and probed with p27Kip1-, HuR-, and β-actin-specific antibodies. The ratio of p27Kip1 to β-actin is shown in the bottom panel. The results are the mean ± S.E. of at least three independent experiments. HuR, HuR siRNA-transfected cells; Scr, scrambled siRNA-transfected cells; Q, quiescent; S, serum stimulated.

Biological Role of HuR in Regulating Stability of Endogenous p27Kip1 mRNA and Expression of Endogenous p27Kip1 Protein

To better define the biological role of HuR in regulating p27Kip1 expression we first studied the effect of HuR knockdown on the stability of the endogenous p27Kip1 mRNA. Cells were transfected with either HuR or scrambled siRNA for 48 h, treated with actinomycin D, total RNA was purified at 0, 2, or 4 h, and the levels of endogenous p27Kip1 mRNA were determined by real time PCR. As shown in Fig. 9B, the level of p27Kip1 mRNA declined faster in cells transfected with HuR siRNA compared with the p27Kip1 mRNA levels in scrambled siRNA-transfected cells. For example, 2 or 4 h after actinomycin D treatment the p27Kip1 mRNA levels were ∼2 times higher in cells transfected with scrambled siRNA compared with cells transfected with HuR siRNA. This data confirm and extend our findings with reporter constructs (see for example, Fig. 8C) that HuR regulates p27Kip1 mRNA stability. To further define the role of HuR in post-transcriptional regulation of the p27Kip1 expression, we determined expression of the p27Kip1 protein in cells transfected with HuR siRNA or scrambled siRNA. As shown in Fig. 9C, knocking down HuR expression dramatically reduced p27Kip1 protein expression in quiescent cells (p > 0.01) and to a lesser but still significant extent in serum-stimulated cells (p > 0.05) when the p27Kip1 level in HuR siRNA-transfected cells was compared with the p27Kip1 level in similarly treated but scrambled siRNA-transfected cells. Scrambled siRNA-transfected quiescent cells express 2.2-fold more p27Kip1 protein than quiescent HuR siRNA-transfected cells. Similarly scrambled siRNA-transfected serum-stimulated cells express ∼1.5-fold more p27Kip1 protein than HuR siRNA-transfected serum-stimulated cells. Taken together with results of Fig. 9, A and B, these data support our contention that HuR stabilizes p27Kip1 mRNA, which results in higher accumulation of p27Kip1 protein.

HuR and 41-kDa Protein Binding Sites in the 5′ UTR Have Opposite Effects on Post-transcriptional Regulation of p27Kip1 Expression

To assess the role of the 41-kDa protein or HuR binding sites in the 5′ UTR of p27Kip1 in the regulation of post-transcriptional expression of p27Kip1, we fused the firefly luciferase ORF in pHGBf-luc/r-luc with full-length p27Kip1 5′ UTR or mutants in which the binding sites for the 41-kDa protein or HuR were deleted. As expected, fusion with the full-length p27Kip1 5′ UTR suppressed expression of firefly luciferase. This suppression was alleviated if the 41-kDa protein binding region (nucleotides 189–269) was deleted (supplemental Fig. S5A). This finding indicates that interaction between the 41-kDa protein and the CT-rich region suppresses basal expression of p27Kip1. This finding is also consistent with our earlier observation that the full-length 5′ UTR, but not the shorter 5′ UTRs (which lack the CT-rich region that interacts with 41-kDa protein), suppresses expression of the reporter gene. Fusion of the firefly luciferase ORF to the 5′ UTR containing a deletion in the HuR binding site significantly reduced reporter gene activity, indicating that interactions between HuR and the 5′ UTR play a critical role in the regulation of post-transcriptional expression of p27Kip1 (supplemental Fig. 5A).

DISCUSSION

Post-transcriptional regulation of p27Kip1 expression is a well known phenomenon. However, the mechanism underlying this regulation is not fully understood. Our studies confirm that de novo synthesis of the p27Kip1 protein is regulated by extracellular signals (Fig. 1). They further demonstrate that the p27Kip1 protein is degraded with a similar half-life in quiescent and serum-stimulated cells in the G1 phase of the cell cycle, as determined by pulse-chase labeling experiments (Fig. 2, A and B). These data rule out the possibility that post-transcriptional expression of p27Kip1 through G1 is regulated by degradation of p27Kip1 protein.

The major findings of our work are: 1) HuR binds to U-rich elements in both the 5′ and 3′ UTRs and regulates the stability of p27Kip1 mRNA; 2) cell cycle-dependent accumulation of p27Kip1 mRNA contributes to cell cycle-dependent post-transcriptional expression of the p27Kip1 protein; and 3) a CT-rich element in the 5′ UTR of p27Kip1 mRNA interacts with a 41-kDa protein and may represses its basal translation. These findings are in contrast to other reports that HuR regulates p27Kip1 expression at the level of translation.

The mouse p27Kip1 gene generates a series of long (450–506 nucleotides) and short (fewer than 250 nucleotides) 5′ UTRs. The mouse p27Kip1 gene also generates transcripts with long and short 3′ UTRs (Fig. 3, A and B). Fusion of p27Kip1 5′ and/or 3′ UTRs to reporter genes impinges on basal and cell cycle-dependent regulation of reporter gene expression. The full-length 5′ UTR modestly suppresses the overall efficiency of reporter gene expression (Fig. 4A). This is due to interaction of a CT-rich region present in the full-length 5′ UTR with a 41-kDa protein. Fusion of reporter genes with 3′ UTRs (singularly or in combination with 5′ UTRs) increased reporter mRNA accumulation but reduced reporter activity (Fig. 4, A and C). The accumulation of the reporter mRNA fused to the 3′ UTR of p27Kip1 was significantly more pronounced in quiescent compared with mitogen-stimulated cells (Fig. 4, B and D). This cell cycle-dependent accumulation of reporter mRNA, which correlated very well with the accumulation of endogenous p27Kip1 mRNA, accounted for the cell cycle-dependent differences in reporter activity. These data indicate that accumulation of p27Kip1 mRNA plays a critical role in the regulation of p27Kip1 expression.

The cell cycle-dependent accumulation of the p27Kip1 mRNA as well as firefly luciferase mRNA fused to UTRs of p27Kip1 could be due to increased transcription or reduced degradation of these mRNAs. A cell cycle-dependent increase in transcription initiation is an unlikely explanation, at least in the case of reporter mRNAs. This is because in the reporter gene experiments, the ORF of the firefly luciferase was fused to the 5′ and/or 3′ UTRs of p27Kip1 mRNA without any known p27Kip1 enhancer/promoter elements. The firefly luciferase (whether or not fused to 5′ and/or 3′ UTRs of p27Kip1) and Renilla luciferase ORFs are transcribed under the control of the same bidirectional heterologous promoter on the same plasmid and are flanked by the same heterologous polyadenylation signal. Consequently, basal and cell cycle-dependent differences in the accumulation of firefly luciferase mRNAs fused to 5′ and/or 3′ UTR elements of p27Kip1 is likely due to differential stability (see below).

Cross-linking mouse p27Kip1 mRNA fragments with cell extracts identified two proteins that specifically interact with p27Kip1 mRNA: 1) 37-kDa protein that cross-links to a single 5′ and multiple 3′ UTR elements and 2) 41-kDa protein that cross-links to a 5′ UTR element (Fig. 6). We identified the 37-kDa protein as HuR (Fig. 7A). We also demonstrated that HuR binds to an element in the 3′ UTR of human p27Kip1 mRNA (Fig. 7B). These data indicate that interaction of HuR with both the 5′ and 3′ UTRs of p27Kip1 mRNA is conserved across species and plays a critical role in the post-transcriptional expression of p27Kip1. Our in vivo cross-linking and RNP immunoprecipitation studies indicate that HuR interacts with the p27Kip1 mRNA in vivo. These findings suggest that HuR may play a critical role in the regulation of p27Kip1 expression. Deletion of all HuR binding sites reduced expression of the reporter genes fused to p27Kip1 5′ and/or 3′ UTR in both proliferating and quiescent cells. Although statistically not significant this effect appears to be somehow more pronounced in quiescent cells. (Fig. 8A and supplemental Fig. S5A). Deletion of the HuR binding sites leads to reduced accumulation of mRNA (Fig. 8B). Our studies demonstrate that HuR plays a critical role in regulating the stability of the p27Kip1 mRNA because deletion of all HuR binding elements significantly reduces the stability of the reporter mRNA fused to the 5′ and 3′ UTRs of p27Kip1 mRNA (Fig. 8C). These data are further supported by our demonstration that knocking down HuR expression reduces accumulation of firefly luciferase mRNA and protein if this reporter ORF is fused to the p27Kip1 5′ and 3′ UTR with WT HuR binding sites but not if the firefly luciferase ORF is fused to 5′ and 3′ UTRs in which all HuR binding sites are deleted. Finally, sucrose density gradient centrifugation followed by real time PCR quantification of reporter mRNA in translated and untranslated fractions confirmed that deletion of HuR binding sites had very little effect on translatability of the reporters but fusion with UTRs of p27Kip1 mRNA reduces the translation efficiency (Fig. 9A). Taken together, these data clearly demonstrate that HuR impinges on the expression of p27Kip1 by regulating the stability of its mRNA. That the HuR binding site in the 5′ UTR of p27Kip1 mRNA partially overlaps with a nuclease cleavage site (30) lends further support to our finding that HuR plays a critical role in regulating the stability of p27Kip1 mRNA.

The literature on regulation of p27Kip1 expression is contradictory. For example, one report suggested that HuR regulates expression of human p27Kip1 by rendering translation of its mRNA more efficient, particularly in G1-arrested cells (27); whereas another report (28) suggested that repression of internal ribosome entry site-dependent p27Kip1 mRNA translation by HuR in proliferating cells is responsible for cell cycle-dependent regulation of p27Kip1 expression. Yet another report by the same group suggested that an upstream ORF in the 5′ UTR of p27Kip1 mRNA is responsible for cell cycle-dependent regulation of p27Kip1 expression (29). We have not been able to amplify the putative p27Kip1 upstream ORF by either 5′ RACE or PCR using specifically designed primers, suggesting this upstream ORF, proximal to the mapped transcription start sites (28, 29) is rarely transcribed, at least in NIH 3T3 cells.

In our hands, deletion of the HuR binding sites or knocking down HuR expression did not reduce the translational efficiency of firefly luciferase mRNA fused to 5′ and/or 3′ UTRs of p27Kip1 mRNA as proposed by Millard et al. (27), nor did it increase firefly luciferase expression in proliferating cells, as would have been expected had HuR inhibited internal ribosome entry site-dependent translation in proliferating cells (Fig. 8 and supplemental Fig. S6). Our data clearly indicate that deletion of HuR binding sites in fusion constructs inhibits expression of reporter genes by reducing the stability and thereby accumulation of the mRNA. Our finding that knocking down HuR expression reduces the stability of the endogenous p27Kip1 mRNA (Fig. 9B) further confirms the results of our reporter gene experiments. Consistently knocking down HuR expression significantly reduced the levels of the p27Kip1 protein. The reduction in the level of p27Kip1 protein, which occurs when HuR is knocked down, is more pronounced in quiescent cells (Fig. 9C). This may be explained by the higher level of p27Kip1 mRNA in quiescent cells. It is also important to note that serum-stimulated cells in our studies are in the late G1 and early S phase of the cell cycle. It is likely that at this cell cycle stage protein stability will also contribute to regulation of p27Kip1 expression. Although our pulse-chase experiments suggest that the stability of the p27Kip1 protein does not change in G1, the signal levels after the 8-h time point are too low and sampling frequency is too sparse to make meaningful conclusions in the later time points. Taken together, our studies demonstrate that the effect of HuR on p27Kip1 expression is mediated by mRNA stability and unlikely to be translational although we cannot rule out minor effects on the translation of p27Kip1 mRNA.

Our studies raise a question of what are the determinants of HuR/p27Kip1 mRNA interactions. Although outside the scope of the current study, we did not observe a frank cell cycle-dependent change in the expression or cytoplasmic/nuclear ratio of HuR. We were also unable to observe a frank change in cell cycle-dependent binding of HuR to p27Kip1 mRNA. We speculate that HuR binds to the p27Kip1 mRNA as a multiprotein complex and that the constituents of such a complex may regulate stability of the p27Kip1 mRNA. Alternatively, post-translational modifications of HuR or other proteins that interact with HuR may have important implications for the stability of the p27Kip1 mRNA. These hypotheses deserve further testing.

In conclusion, our studies demonstrate that post-transcriptional expression of p27Kip1 is regulated at the level of mRNA stability by HuR, at the level of translation by diffuse elements in the 3′ UTR of p27Kip1, and perhaps by a CT-rich element present only in the full-length 5′ UTR. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first demonstration that HuR-dependent mRNA stability plays a critical role in post-transcriptional regulation of p27Kip1 expression.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Jose A. Halperin for continuous support and encouragement throughout these studies and for through discussion of the manuscript, Drs. Magdalena Tosteson, Micheal Chorev, Melina Fan, and Geoffrey Cooper for critical review of manuscript, Dr. Frank McKeon for providing mouse embryonic cDNA library, Dr. Henry M. Furneaux for providing anti-HuR antibodies, and Dr. Gideon Dreyfus for anti-hnRNP-A1 and -C1/C2 antibodies.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S5, additional “Materials and Methods,” and “Results.”

- CDK

- cyclin-dependent kinase

- UTR

- untranslated region

- BCS

- bovine calf serum

- hnRNP

- heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein

- tTA

- tetracycline-regulated transactivator

- RACE

- rapid amplification of cDNA ends

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- ORF

- open reading frame

- DLR

- dual luciferase assay

- WT

- wild type

- F-luc

- firefly luciferase

- R-luc

- Renilla luciferase.

REFERENCES

- 1.Graña X., Reddy E. P. (1995) Oncogene 11, 211–219 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lees E. (1995) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 7, 773–780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee W. H., Chen P. L., Riley D. J. (1995) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 752, 432–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morgan D. O. (1995) Nature 374, 131–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elledge S. J., Winston J., Harper J. W. (1996) Trends Cell Biol. 6, 388–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sherr C. J., Roberts J. M. (1995) Genes Dev. 9, 1149–1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sherr C. J., Roberts J. M. (2004) Genes Dev. 18, 2699–2711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ray A., James M. K., Larochelle S., Fisher R. P., Blain S. W. (2009) Mol. Cell. Biol. 29, 986–999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aktas H., Cai H., Cooper G. M. (1997) Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 3850–3857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coats S., Flanagan W. M., Nourse J., Roberts J. M. (1996) Science 272, 877–880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rivard N., L'Allemain G., Bartek J., Pouysségur J. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 18337–18341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ayrault O., Zindy F., Rehg J., Sherr C. J., Roussel M. F. (2009) Mol. Cancer Res. 7, 33–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loda M., Cukor B., Tam S. W., Lavin P., Fiorentino M., Draetta G. F., Jessup J. M., Pagano M. (1997) Nat. Med. 3, 231–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quinn D. I., Henshall S. M., Sutherland R. L. (2005) Eur. J. Cancer 41, 858–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woenckhaus C., Maile S., Uffmann S., Bansemir M., Dittberner T., Poetsch M., Giebel J. (2005) Histol. Histopathol. 20, 501–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodolico V., Aragona F., Cabibi D., Di Bernardo C., Di Lorenzo R., Gebbia N., Gulotta G., Leonardi V., Ajello F. (2005) Oral Oncol. 41, 268–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tan P., Cady B., Wanner M., Worland P., Cukor B., Magi-Galluzzi C., Lavin P., Draetta G., Pagano M., Loda M. (1997) Cancer Res. 57, 1259–1263 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sgambato A., Cittadini A., Faraglia B., Weinstein I. B. (2000) J. Cell Physiol. 183, 18–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sgambato A., Migaldi M., Leocata P., Ventura L., Criscuolo M., Di Giacomo C., Capelli G., Cittadini A., De Gaetani C. (2000) Cancer 89, 2247–2257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zafon C., Obiols G., Castellví J., Ramon y Cajal S., Baena J. A., Mesa J. (2008) Endocr. Pathol. 19, 184–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pagano M., Tam S. W., Theodoras A. M., Beer-Romero P., Del Sal G., Chau V., Yew P. R., Draetta G. F., Rolfe M. (1995) Science 269, 682–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hengst L., Reed S. I. (1996) Science 271, 1861–1864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agrawal D., Hauser P., McPherson F., Dong F., Garcia A., Pledger W. J. (1996) Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 4327–4336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nguyen H., Gitig D. M., Koff A. (1999) Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 1190–1201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brandeis M., Hunt T. (1996) EMBO J. 15, 5280–5289 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malek N. P., Sundberg H., McGrew S., Nakayama K., Kyriakides T. R., Roberts J. M. (2001) Nature 413, 323–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Millard S. S., Vidal A., Markus M., Koff A. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 5947–5959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kullmann M., Göpfert U., Siewe B., Hengst L. (2002) Genes Dev. 16, 3087–3099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Göpfert U., Kullmann M., Hengst L. (2003) Hum. Mol. Genet. 12, 1767–1779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao Z., Chang F. C., Furneaux H. M. (2000) Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 2695–2701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guo X., Hartley R. S. (2006) Cancer Res. 66, 7948–7956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Atasoy U., Watson J., Patel D., Keene J. D. (1998) J. Cell Sci. 111, 3145–3156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peng S. S., Chen C. Y., Xu N., Shyu A. B. (1998) EMBO J. 17, 3461–3470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gossen M., Freundlieb S., Bender G., Müller G., Hillen W., Bujard H. (1995) Science 268, 1766–1769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aktas H., Flückiger R., Acosta J. A., Savage J. M., Palakurthi S. S., Halperin J. A. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 8280–8285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]