Abstract

Several clathrin-independent endocytosis mechanisms have been identified that can be distinguished by specific requirements for certain proteins, such as caveolin-1 (Cav1) and the Rho GTPases, RhoA and Cdc42, as well as by specific cargo. Some endocytic pathways may be co-regulated such that disruption of one pathway leads to the up-regulation of another; however, the underlying mechanisms for this are unclear. Cav1 has been reported to function as a guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitor (GDI), which inhibits Cdc42 activation. We tested the hypothesis that Cav1 can regulate Cdc42-dependent, fluid phase endocytosis. We demonstrate that Cav1 overexpression decreases fluid phase endocytosis, whereas silencing of Cav1 enhances this pathway. Enhancement of Cav1 phosphorylation using a phosphatase inhibitor reduces Cdc42-regulated pinocytosis while stimulating caveolar endocytosis. Fluid phase endocytosis was inhibited by expression of a putative phosphomimetic mutant, Cav1-Y14E, but not by the phospho-deficient mutant, Cav1-Y14F. Overexpression of Cav2, or a Cav1 mutant in which the GDI region was altered to the corresponding sequence in Cav2, did not suppress fluid phase endocytosis. These results suggest that the Cav1 expression level and phosphorylation state regulates fluid phase endocytosis via the interaction between the Cav1 GDI region and Cdc42. These data define a novel molecular mechanism for co-regulation of two distinct clathrin-independent endocytic pathways.

Keywords: Caveolae, Endocytosis, G Proteins, Membrane Trafficking, Plasma Membrane, Cdc42, Rho GTPases, Caveolin, Fluid Phase Endocytosis

Introduction

It is now widely recognized that multiple clathrin-independent mechanisms of endocytosis exist in addition to the classical process of clathrin-mediated internalization (1, 2). Two of the better characterized clathrin-independent endocytic pathways are caveolar endocytosis and fluid phase pinocytosis. The first of these mechanisms is mediated by caveolae, 50–80-nm flask-shaped invaginations at the plasma membrane (PM),4 which are enriched in sphingolipids and cholesterol and marked by the presence of a caveolin protein, usually caveolin-1 (Cav1) (3). Endocytosis through caveolae is promoted by ligand binding and is dynamin-dependent (4–7). Cargo may include some viruses, bacteria, albumin, cholera toxin, fluorescent glycosphingolipids, and antibody-clustered GPI-anchored proteins (1, 3, 8). Another well recognized clathrin-independent pathway is fluid phase endocytosis, which is dynamin-independent and is regulated by the small GTPase, Cdc42, as well as by Arf1 (1, 9, 10). This pathway is responsible for internalization of unclustered GPI-anchored proteins that are initially detected in tubular invaginations from the PM and that internalize large volumes of fluid with each budding event (9, 11).

Previous studies have suggested that some endocytic pathways may be co-regulated such that inhibition of one leads to the up-regulation of another (12, 13); however, the underlying mechanisms responsible for such co-regulation are not known. Recently, it has been shown that Cav1 functions as a novel Cdc42 guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitor (GDI) in pancreatic β-cells (14). Analysis of the Cav1 amino acid sequence has revealed a motif that is conserved in GDIs (15), and this finding was further supported by in vitro binding assays showing a direct interaction between Cav1 and GDP-bound Cdc42 (14). Given these findings, we hypothesized that Cav1/Cdc42 interactions may support a mechanism for the coordinate regulation of caveolar and Cdc42-dependent fluid phase endocytosis. Here, we demonstrate that fluid phase endocytosis is inhibited by Cav1 overexpression and stimulated by Cav1 knockdown. We further show that the effects of Cav1 on the fluid phase pathway are regulated by its state of phosphorylation at tyrosine 14.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Lipids and Miscellaneous Reagents

Fluorescently labeled lactosylceramide (Bodipy-LacCer) was synthesized as described (16). Fluorescent Alexa Fluor (AF488, AF594, or AF647)-labeled transferrin (Tfn) or dextran were from Invitrogen; PP2 was from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). Plasmids encoding Cav1-GFP (A. Helenius, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Zurich; Switzerland), Cav2-GFP (M. McNiven, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, MN) and GPI-GFP (J. Lippincott-Schwartz, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) were generous gifts, as noted. Cav1-mRed was generated as described (7). Cav1-FLAG was made by site-directed mutagenesis using the QuikChange kit from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA). Briefly, a FLAG tag followed by a stop codon was added at the C terminus of the Cav1 open reading frame in the Cav1-GFP plasmid. Cav1-Y14F and Cav1-Y14E mutants, and the Cav1/Cav2 GDI domain chimera (see supplemental Fig. S2B) were generated from the wild type Cav1-FLAG, Cav1-GFP, or Cav1-mRed plasmids by further site-directed mutagenesis.

Antibodies to Cav1, pY14-Cav1, Cdc42, and clathrin heavy chain were from BD Pharmingen, Inc. (San Diego, CA). Antibody to β-actin was from Cell Signaling Technology. AF594-labeled Fab fragment of anti-GFP was prepared as described (17). Recombinant Cdc42-GST was purchased from Cytoskeleton, Inc. (Denver, CO). Sodium orthovanadate and all other reagents were from Sigma.

Cell Culture, Transfection, and Virus Infection

CHO-K1 cells were maintained as described (18) and transfected using FuGENE 6 (Roche Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Human skin fibroblasts were maintained as described (19, 20) and transfected using an Amaxa Biosystems nucleoporator (Gaithersburg, MD).

Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) for Cav1 were from Dharmacon (Chicago, IL) and transfected according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the cells were first transfected with siRNAs for Cav1 using the manufacturer's carrier. After 2 days, the cells were replated and further transfected for another 3 days before the assay.

Ad-Cav1 was a generous gift from W. Sessa (Yale University, New Haven, CT); recombinant adenovirus encoding dominant negative (DN) Cdc42 was from Cell Biolabs, Inc. (San Diego, CA). Except when noted, cells were infected with adenoviruses (titer ∼ 1 × 107 plaque-forming units/ml) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1:100. After overnight infection, the media was replaced with normal medium, and assays were performed 24 h later. Cell viability was ≥95–100% for MOIs between 1:10 and 1:100.

Incubation of Cells with Various Endocytic Markers

For dextran uptake, cells were incubated with 1 mg/ml fluorescent dextran for the indicated time (usually 5 min) at 37 °C without preincubation or acid stripping. For GPI-GFP internalization, cells transiently transfected with GPI-GFP were incubated with AF594-labeled Fab fragment against GFP for 30 min at 10 °C, washed, and incubated further for 5 min at 37 °C. The GPI-GFP remaining at the PM was then removed by incubation with phosphatidylinositol phospholipase C (10 units/ml) for 20 min at 10 °C as described (17).

For caveolar uptake, cells were typically incubated for 30 min at 10 °C with 1 μm Bodipy-LacCer/bovine serum albumin in HEPES-buffered minimum Eagle's medium with glucose, washed twice, and further incubated for the indicated times at 37 °C. Bodipy-LacCer remaining at the PM was then removed by back exchange at 10 °C as described (16). For clathrin-dependent endocytosis, cells were serum-starved for 2 h and then preincubated with 5 μg/ml AF594-Tfn for 30 min at 10 °C, further incubated for 5 min at 37 °C, and then acid-stripped to remove labeled protein remaining at the cell surface (20).

Vanadate Treatment

Cells were preincubated in HEPES-buffered minimum Eagle's medium containing 1 mm sodium orthovanadate for 1 h at 37 °C as described (21, 22).

GST Pulldown Assay

For Cdc42-GST pulldown, 10 μg of Cdc42-GST protein linked to glutathione-Sepharose beads was incubated with cleared detergent lysates prepared from CHO-K1 cells overexpressing FLAG-tagged Cav1, Cav1-Y14F, or Cav1-Y14E (325 μg of protein) in Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer (25 mm Hepes, pH 7.4, 0.25% Nonidet P-40, 10% glycerol, 50 μm sodium fluoride, 10 mm sodium pyrophosphate, 137 mm sodium chloride, 1 mm sodium vanadate, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml pepstatin, and 5 μg/ml leupeptin) for 2 h at 4 °C. Following three washes, proteins were eluted from the Sepharose beads and detected using anti-FLAG antibody by Western blotting.

Fluorescence and Electron Microscopy Studies

Quantitative fluorescence microscopy and image analysis were carried out using an Olympus IX70 microscope equipped with a CCD camera (either Hamamatsu C4742–95 or QuantEM 512SC) and the “Metamorph” image-processing program (Universal Imaging Corp., Downingtown, PA) as described (7, 20, 23). For co-localization studies, no “crossover” between microscope channels was observed at the concentration and exposure setting used. For electron microscopy studies, samples were fixed in the presence of 1 mm ruthenium red and embedded and sectioned as described (18). Thin sections were viewed under a FEI Tecnai T12 transmission electron microscope operating at ∼80 kV and quantified as described (18).

RESULTS

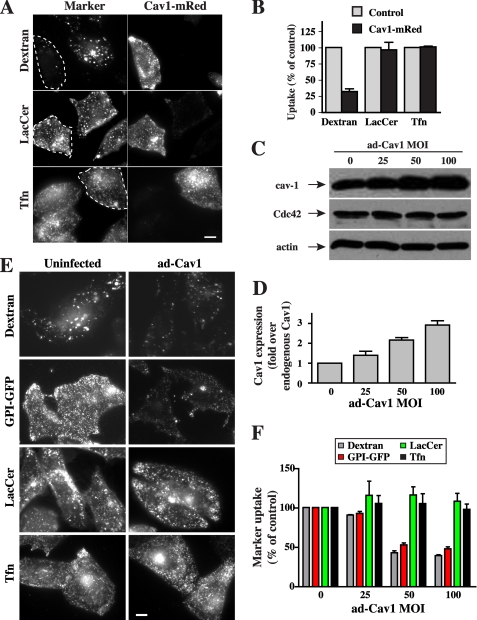

We first investigated the effect of transient Cav1 overexpression in CHO-K1 fibroblasts on the endocytosis of previously characterized markers for clathrin-dependent (transferrin; Tfn), caveolar-dependent (Bodipy-LacCer), and Cdc42-dependent, fluid phase (fluorescent dextran and GPI-GFP) endocytosis (9, 18, 20). Cells were transfected with a plasmid encoding Cav1 fused to a monomeric red fluorescent protein (Cav1-mRed) (7). Fluid phase uptake of dextran was inhibited ∼70% by Cav1-mRed expression, whereas LacCer and Tfn uptake were unaffected (Fig. 1, A and B).

FIGURE 1.

Cav1 overexpression inhibits fluid phase uptake. A and B, cells were transfected with Cav1-mRed for 24 h. Internalization (5 min at 37 °C) of AF488-dextran, -Tfn, and -Bodipy-LacCer in transfected cells (identified by mRed fluorescence and outlined by dashed white lines) and untransfected cells (Control) was performed as described (18), observed by fluorescence microscopy (A), and quantified by image analysis (B). Bar, 10 μm. Values are means ± S.D. (n ≥ 50 cells from three independent experiments). C–F, CHO-K1 cells were either uninfected (control) or infected for 48 h with a recombinant adenovirus-expressing Cav1 (Ad-Cav1) at the indicated MOI (C). Expression of total Cav1 (overexpressed and endogenous Cav1), Cdc42, and actin were determined by immunoblotting in cells infected Ad-Cav1 at various MOI (D). Cav1 levels on immunoblots as in C were quantified relative to endogenous Cav1 (0 Ad-Cav1). Values are means ± S.D. (n = 3 independent experiments). E, CHO-K1 cells were uninfected (0 Ad-Cav1) or infected with Ad-Cav1 at an MOI of 1:100 for 48 h. Internalization of fluorescently labeled dextran, LacCer, and Tfn was measured after 5 min at 37 °C as in A. GPI-GFP internalization was measured using an AF594-labeled anti-GFP-Fab. Cells were treated with phosphatidylinositol phospholipase C to remove surface GPI-GFP before acquiring fluorescence images. Bar, 10 mm. F, quantitation of internalization of markers in CHO-K1 cells as in E infected with Ad-Cav1, relative to uninfected control cells. Marker uptake was quantified by image analysis. Values are means ± S.E. (n ≥ 60 cells from three independent experiments) and are expressed relative to the extent of endocytosis for the same marker seen in uninfected control cells.

To verify that the effect of Cav1-mRed was specifically due to Cav1 overexpression and not an indirect effect of transfection, we next infected cells with an adenoviral vector that encodes Cav1 (Ad-Cav1). Infection with Ad-Cav1 at an MOI of 25–100 resulted in a 1.2–3-fold overexpression of Cav1 relative to uninfected cells, whereas the expression of actin and Cdc42 were not affected under the same conditions (Fig. 1, C and D). The endocytosis of markers of the Cdc-42-dependent pathway, dextran and GPI-GFP, decreased with increasing levels of adenoviral-mediated Cav1 overexpression, reaching a maximum effect of ∼50% inhibition with Ad-Cav1 at an MOI of 50–100 (Fig. 1, E and F). In contrast, clathrin-mediated endocytosis of Tfn and caveolar uptake of LacCer were not significantly affected by Cav1 overexpression using Ad-Cav1 at any MOI tested (Fig. 1, E and F), suggesting that inhibition is specific for the fluid phase pathway. Although a priori it might be expected that overexpression of Cav1 would stimulate caveolar endocytosis, the lack of an effect in the current study may reflect the fact that while Cav1 is in excess, other components required for caveolar endocytosis such as PM cholesterol, sphingolipids, or β1-integrins (7, 17, 23) are limiting.

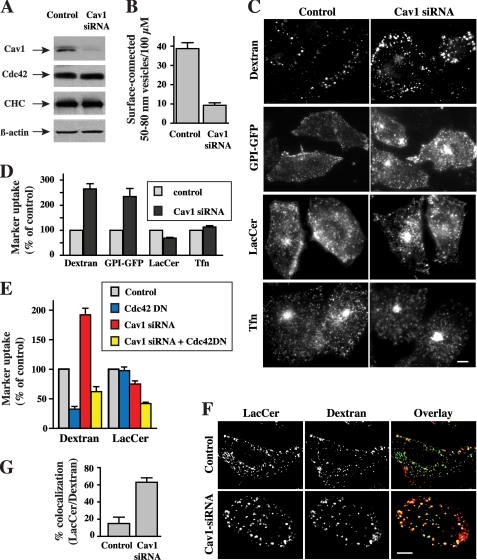

We next used siRNA to assess the effect of Cav1 depletion on uptake of various endocytic markers in CHO-K1 cells. Transfection of cells with siRNA for Cav1 reduced the expression of endogenous Cav1 by ∼80% relative to control levels but had no effect on the levels of actin and Cdc42 (Fig. 2A). Electron microscopy of control and Cav1-depleted cells showed a ∼75% reduction in the number of surface-connected, 50–80-nm diameter vesicles (Fig. 2B), consistent with the Cav1 requirement for caveolae formation (24). Depletion of Cav1 enhanced the endocytosis of dextran and GPI-anchored proteins by ∼2.5-fold, whereas Tfn uptake was unchanged under the same conditions (Fig. 2, C and D).

FIGURE 2.

Cav1 silencing stimulates fluid phase uptake. CHO-K1 cells were transfected with or without siRNA against Cav1 for 5 days. A, cell lysates were prepared, and equal amounts of protein were subjected to SDS-PAGE. Expression of Cav1, Cdc42, clathrin heavy chain (CHC), and actin were determined by immunoblotting in three independent experiments. Shown are representative blots. B, shown is the quantitation of the number of surface-connected 50–80-nm vesicles in control and cells transfected with Cav1 siRNA. Samples were stained with ruthenium red (to identify PM invaginations), fixed, sectioned vertically to the culture dish, and processed for transmission electron microscopy (7). Values represent the number of 50–80-nm surface-connected vesicles within 0.5 μm of the cell surface per 100 μm of perimeter length. A total of 15 different cells were analyzed for each condition in two independent experiments. C and D, internalization of fluorescently labeled dextran, LacCer, Tfn, or GPI-GFP was measured after 5 min at 37 °C (see under “Experimental Procedures”). Noninternalized markers were removed from the PM by back exchange with defatted bovine serum albumin (DF-BSA) (for Bodipy-LacCer), by acid stripping (for AF594-labeled Tfn) or by phosphatidylinositol phospholipase C treatment (for GPI-GFP) before acquiring fluorescence images. Marker internalization relative to untransfected cells (control) was quantified by image analysis. Values are the mean ± S.D. (n ≥ 50 cells from three independent experiments). E, cells were transfected with or without siRNA against Cav1 for 5 days and infected with adenovirus encoding DN Cdc42 for the last 48 h during the transfection of Cav1 siRNA. Internalization (5 min at 37 °C) of the indicated markers was measured as in Fig. 1. Values are the mean ± S.D. (n ≥ 50 cells from three independent experiments). F and G, co-localization of Bodipy-LacCer with dextran in CHO-K1 cells. Cells, untransfected or transfected with Cav1 siRNA, were incubated with Bodipy-LacCer for 30 min at 10 °C. AF647-labeled dextran was then added, and the samples were shifted to 37 °C for 3 min, followed by back exchange (see under “Experimental Procedures”). Separate images were acquired for each fluorophore using epifluorescence microscopy, rendered in pseudocolor, and are presented as overlays. Fluorescent signals were adjusted to maximize contrast to facilitate co-localization, and intensities do not represent degree of internalization. G, co-localization was quantified by image analysis. Values are the mean ± S.E. (n ≥ 10 cells for each condition from two independent experiments). Bars in C and F, 10 μm.

Interestingly, an 80% depletion of Cav1 resulted in only a 20% inhibition of Bodipy-LacCer uptake (Fig. 2, C and D), suggesting that Cav1 depletion induced uptake of the LacCer analog by another endocytic mechanism. To test this possibility, we infected cells with an adenovirus to express DN Cdc42, which has been previously shown to selectively inhibit the fluid phase pathway (9, 18). We found that although ectopic expression of DN Cdc42 had no effect on LacCer internalization in control cells, DN Cdc42 inhibited LacCer uptake by >40% in Cav1-depleted cells compared with Cav1 siRNA treatment alone (Fig. 2E). Expression of DN Cdc42 inhibited dextran uptake in both control and Cav1-depleted cells, demonstrating the persistence of Cdc42-dependent fluid phase uptake in both conditions (Fig. 2E). Furthermore, although little co-localization was seen between LacCer and fluorescent dextran after 3 min of endocytosis in control cells with normal levels of Cav1 (Fig. 2, F and G), these probes extensively co-localized in Cav1-depleted cells under the same conditions (Fig. 2, F and G), supporting the idea that LacCer is significantly internalized by the fluid phase pathway in Cav1-depleted cells. Thus, Cav1-depletion in CHO-K1 fibroblasts inhibited caveolae formation, up-regulated Cdc42-regulated endocytosis of markers for the fluid phase pathway (dextran and GPI-anchored proteins), and induced “pathway switching” of a caveolar marker (Bodipy-LacCer; 18, 20) to the fluid phase pathway. Similarly, knockdown of Cav1 in human skin fibroblasts resulted in a 2-fold stimulation of dextran uptake, a partial inhibition of LacCer internalization, and had no effect on Tfn endocytosis (see supplemental Fig. S1).

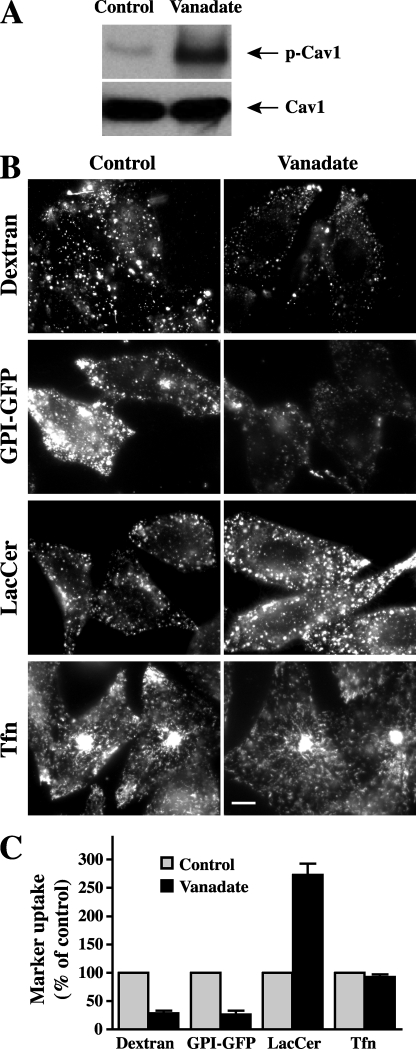

Because Cav1 phosphorylation plays an important role in the regulation of Cav1 function and its interactions with other proteins (21, 22, 25–27), we next investigated the possibility that Cav1 phosphorylation affects the ability of Cav1 to inhibit fluid phase endocytosis. Thus, we examined the effect of vanadate, a phosphatase inhibitor that increases Cav1 phosphorylation (21), on different endocytic mechanisms (Fig. 3). Pretreatment of cells with vanadate significantly increased Tyr14 phosphorylation of Cav1, as detected by Western blotting (Fig. 3A). Vanadate stimulated caveolar-mediated endocytosis of LacCer, whereas the Cdc42-dependent endocytosis of dextran and GPI-GFP were severely inhibited by the same treatment (Fig. 3, B and C). In contrast, vanadate had little effect on Tfn uptake (Fig. 3, B and C).

FIGURE 3.

Enhanced Cav1 phosphorylation inhibits fluid phase uptake. CHO-K1 cells were untreated (control) or pretreated with 1 mm vanadate for 60 min at 37 °C. A, cell lysates were collected and immunoblotted with anti-p-Cav1(Tyr14) or anti-Cav1 antibodies. B, internalization of endocytic markers was observed after 1 min (lactosylceramide, LacCer) or 5 min (all other markers) at 37 °C in cells that were untreated or pretreated with vanadate. Bar, 10 μm. C, quantitation of marker internalization as in B, relative to untreated cells (control) by image analysis. Values are the mean ± S.E. (n ≥ 50 cells from three independent experiments).

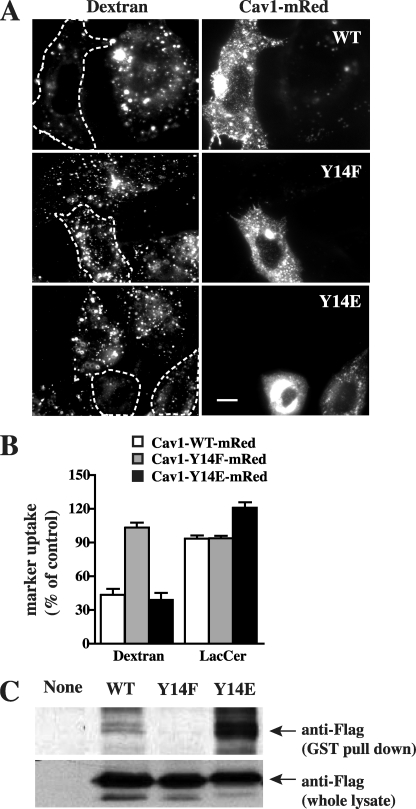

To further confirm the role of Cav1 phosphorylation on its interaction with Cdc42 and the effect of p-Cav1 on different endocytic mechanisms, we generated recombinant Cav1 in which Tyr14 was replaced with Glu (Y14E) as a proposed phosphomimetic substitution, or with Phe (Y14F) as a phospho-deficient substitution. The constructs were tagged with mRed at their C terminus to ensure comparison of transfected cells with similar expression levels of Cav1 mutants. Transient transfection of Cav1-WT-mRed or the putative phosphomimetic Cav1-Y14E, inhibited dextran uptake, whereas Cav1-Y14F-mRed had no effect on dextran uptake (Fig. 4, A and B). Together, these results show that the inhibition of fluid phase endocytosis by Cav1 is enhanced by phosphorylation of Cav1 at Tyr14.

FIGURE 4.

Cav1 phosphorylation at Tyr14 is required for inhibition of the fluid phase pathway. A and B, cells were transfected with Cav1-WT-mRed, Cav1-Y14F-mRed, or Cav1-Y14E-mRed constructs. Internalization (5 min at 37 °C) of AF488-labeled dextran in transfected cells (identified by mRed fluorescence and outlined by dashed white lines) relative to untransfected cells (Control) was observed by fluorescence microscopy (A) and quantified by image analysis (B) (mean ± S.E., n ≥ 30 cells for each condition). Bar, 10 μm. C, cells were untransfected or transfected with Cav1-WT-FLAG, Cav1-Y14F-FLAG, or Cav1-Y14E-FLAG for 48 h. Cells were then lysed and incubated with purified GST-Cdc42 for 2 h at 4 °C. Total Cav1 WT and its mutants in the cell lysates or pulled down by purified GST-Cdc42 were determined by Western blotting.

We also performed GST-Cdc42 pulldowns from lysates of cells overexpressing FLAG-labeled Cav1-WT, -Y14F, and -Y14E. FLAG-tagged Cav1-Y14E showed the strongest binding with GST-Cdc42 among the three, whereas no binding of Cav1-Y14F to Cdc42 was observed (Fig. 4C). These findings are consistent with our cell studies showing that Tyr14 phosphorylation is necessary for the inhibitory effects of Cav1 on the fluid phase pathway and suggest that these effects may be mediated by direct interactions between Cav1 and Cdc42.

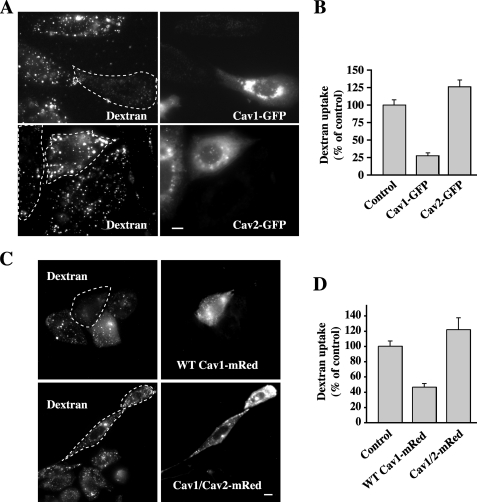

Finally, we investigated the possibility that the inhibitory properties of Cav1 are shared by Cav2. The Cav1 protein sequence contains a GDI consensus region (14, 15) that is totally conserved between mammalian species of Cav1; however, this region is less conserved among mammalian Cav2 sequences (see supplemental Fig. S2A). When Cav2-GFP was transiently expressed in CHO cells, it slightly stimulated dextran uptake, unlike Cav1-GFP, which inhibited dextran endocytosis (Fig. 5, A and B). Importantly, when we carried out a similar experiment using a Cav1/Cav2-mRed chimera in which the Cav1 GDI consensus region was replaced with the corresponding region for Cav2 (see supplemental Fig. S2B), there was no inhibition of fluid phase uptake, but rather a slight stimulation relative to control samples (Fig. 5, C and D), similar to the effect of Cav2 expression. These results support the idea that the inhibitory properties of Cav1 toward fluid phase endocytosis reside in its GDI consensus region.

FIGURE 5.

Effect of Cav1, Cav2, and a Cav1/Cav2 chimera on fluid phase uptake. Cells were transfected with (A and B) WT Cav1-GFP or Cav2-GFP, or (C and D) WT Cav1-mRed or a Cav1/Cav2-mRed chimera in which the GDI region of Cav1 is replaced with the corresponding sequence from Cav2 (see supplemental Fig. S2) for 24 h. Internalization (5 min at 37 °C) of fluorescent dextran in transfected cells (determined by GFP or mRed fluorescence and outlined by dashed white lines) relative to untransfected cells (control) was observed by fluorescence microscopy and quantified by image analysis. Values are the mean ± S.E. (n ≥ 30 cells for each condition). Bars, 10 μm.

DISCUSSION

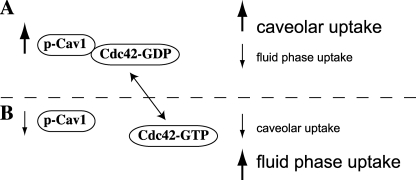

Our results provide evidence for a mechanism for co-regulation between two clathrin-independent mechanisms of endocytosis, caveolar uptake, and fluid phase endocytosis (Fig. 6). We show that Cav1 overexpression decreases fluid phase endocytosis, whereas Cav1 depletion by siRNA significantly enhances fluid phase uptake. We further demonstrate that the ability of Cav1 to inhibit the fluid phase pathway is dependent on Cav1-Tyr14 phosphorylation. These findings may represent a natural mechanism by which mammalian cells coordinate different forms of endocytosis, thus maintaining tight control over membrane internalization and/or PM surface area.

FIGURE 6.

Working model for co-regulation of caveolar and fluid phase endocytosis. A, conditions that increase the levels of p-Cav1, such as Cav1 overexpression or treatment of cells with phosphatase inhibitors, lead to increased association of p-Cav1 with Cdc42, holding Cdc42 in the inactive, GDP-bound form. Thus, upon increased levels of p-Cav1, Cdc42-dependent fluid phase endocytosis is inhibited. Increased p-Cav1 is also associated with higher levels of caveolar endocytosis. B, under conditions where p-Cav1 levels are decreased, such as during Cav1 knockdown, Cdc42 is less associated with p-Cav1 and is thus able to be converted to the active, GTP-bound form. Thus, Cdc42-dependent endocytosis is increased, whereas decreased p-Cav1 or total Cav1 levels lead to decreased uptake via caveolae.

The mechanism by which Cav1 expression regulates endocytosis remains to be fully resolved. Cav1 has been shown to interact directly with and bind preferentially to the GDP-bound form of a number of GTPases, such as H-Ras, and heterotrimeric G protein α subunits (14, 15, 28, 29). Relevant to our study, Nevins and Thurmond (14) demonstrated that Cav1 interacts directly with the GDP-bound form of Cdc42 and that Cav1 depletion leads to an activation of Cdc42 and an increase in basal Cdc42-dependent insulin secretion. Cells from Cav1 knock-out mice also exhibit an increase in Cdc42 activity relative to cells from normal mice (30). Given these results and our own findings, we suggest that Cav1 levels regulate fluid phase endocytosis by modulating the activation state of Cdc42. Further, our findings suggest that it is the Tyr14-phosphorylated form of Cav1 that is responsible for the inhibition of Cdc42 activation (Fig. 4D) and thus fluid phase endocytosis. Finally, we showed that Cav2, unlike Cav1, is unable to inhibit Cdc42-dependent endocytosis (Fig. 5, A and B) and that the putative GDI-region of Cav1 (14, 15) is responsible for its inhibitory effects (Fig. 5, C and D).

Our findings that Cav1 levels affect fluid phase endocytosis have potential physiological relevance. Cav1 expression levels in mammals vary through different cell types from high (adipocytes and fibroblasts) to low (some lymphocytes and neuronal cells) (3, 31–33). In addition, Cav1 is reported to be down-regulated in some cancer cell types and up-regulated in others (34, 35). Thus, it is possible that such different levels of Cav1 expression modulate the extent of fluid phase endocytosis in these cell types. An additional important aspect of our studies is the recognition that Cav1 phosphorylation has an impact on the ability of Cav1 to inhibit fluid phase endocytosis because it is known that various stimuli can alter Cav1 phosphorylation. For example, the binding of certain cargo (e.g. LacCer, insulin) increases Cav1 Tyr14 phosphorylation as well as stimulating internalization of caveolae (23, 36). In addition, other factors such as oxidative stress, hyperosmotic stress, shear stress, and UV light have all been reported to induce Cav1 phosphorylation (21, 37, 38). Such factors could thus inhibit fluid phase endocytosis via production of pY14-Cav1. It should be recognized, however, that many other factors must play roles in regulating fluid phase endocytosis, including the abundance of proteins (e.g. Cdc42, Arf1) involved in this process, as well as regulators of the activation state (e.g. GDIs, GTPase activating proteins) of these proteins.

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant GM22942 from USPHS (to R. E. P.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2.

- PM

- plasma membrane

- Ad-Cav1

- adenovirus encoding caveolin-1

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein

- AF

- Alexa Fluor

- Bodipy-LacCer

- N-[5-(5,7-dimethyl boron dipyrromethene difluoride)-1-pentanoyl]-1′,1-lactosyl-sphingosine

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- CHO

- Chinese hamster ovary

- GST

- glutathione S-transferase

- Cav1

- caveolin-1

- DN

- dominant negative

- GDI

- guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitor

- MOI

- multiplicity of infection

- Tfn

- transferrin

- WT

- wild type.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mayor S., Pagano R. E. (2007) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 603–612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nichols B. J., Lippincott-Schwartz J. (2001) Trends Cell Biol. 11, 406–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parton R. G., Simons K. (2007) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 185–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henley J. R., Krueger E. W., Oswald B. J., McNiven M. A. (1998) J. Cell Biol. 141, 85–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oh P., McIntosh D. P., Schnitzer J. E. (1998) J. Cell Biol. 141, 101–114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pelkmans L., Püntener D., Helenius A. (2002) Science 296, 535–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma D. K., Brown J. C., Choudhury A., Peterson T. E., Holicky E., Marks D. L., Simari R., Parton R. G., Pagano R. E. (2004) Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 3114–3122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mineo C., Anderson R. G. (2001) Histochem Cell Biol. 116, 109–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sabharanjak S., Sharma P., Parton R. G., Mayor S. (2002) Dev. Cell 2, 411–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumari S., Mayor S. (2008) Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 30–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirkham M., Parton R. G. (2005) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1746, 349–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Damke H., Baba T., van der Bliek A. M., Schmid S. L. (1995) J. Cell Biol. 131, 69–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pelkmans L., Fava E., Grabner H., Hannus M., Habermann B., Krausz E., Zerial M. (2005) Nature 436, 78–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nevins A. K., Thurmond D. C. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 18961–18972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li S., Okamoto T., Chun M., Sargiacomo M., Casanova J. E., Hansen S. H., Nishimoto I., Lisanti M. P. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 15693–15701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin O. C., Pagano R. E. (1994) J. Cell Biol. 125, 769–781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh R. D., Holicky E. L., Cheng Z., Kim S. Y., Wheatley C. L., Marks D. L., Bittman R., Pagano R. E. (2007) J. Cell Biol. 176, 895–901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng Z. J., Singh R. D., Sharma D. K., Holicky E. L., Hanada K., Marks D. L., Pagano R. E. (2006) Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 3197–3210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirkham M., Fujita A., Chadda R., Nixon S. J., Kurzchalia T. V., Sharma D. K., Pagano R. E., Hancock J. F., Mayor S., Parton R. G. (2005) J. Cell Biol. 168, 465–476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh R. D., Puri V., Valiyaveettil J. T., Marks D. L., Bittman R., Pagano R. E. (2003) Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 3254–3265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aoki T., Nomura R., Fujimoto T. (1999) Exp. Cell Res. 253, 629–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.del Pozo M. A., Balasubramanian N., Alderson N. B., Kiosses W. B., Grande-García A., Anderson R. G., Schwartz M. A. (2005) Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 901–908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharma D. K., Brown J. C., Cheng Z., Holicky E. L., Marks D. L., Pagano R. E. (2005) Cancer Res. 65, 8233–8241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drab M., Verkade P., Elger M., Kasper M., Lohn M., Lauterbach B., Menne J., Lindschau C., Mende F., Luft F. C., Schedl A., Haller H., Kurzchalia T. V. (2001) Science 293, 2449–2452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Labrecque L., Nyalendo C., Langlois S., Durocher Y., Roghi C., Murphy G., Gingras D., Béliveau R. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 52132–52140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orlichenko L., Huang B., Krueger E., McNiven M. A. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 4570–4579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peng F., Wu D., Ingram A. J., Zhang B., Gao B., Krepinsky J. C. (2007) J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 18, 189–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li S., Couet J., Lisanti M. P. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 29182–29190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Song K. S., Li S., Okamoto T., Quilliam L. A., Sargiacomo M., Lisanti M. P. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 9690–9697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grande-García A., Echarri A., de Rooij J., Alderson N. B., Waterman-Storer C. M., Valdivielso J. M., del Pozo M. A. (2007) J. Cell Biol. 177, 683–694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galbiati F., Volonte D., Gil O., Zanazzi G., Salzer J. L., Sargiacomo M., Scherer P. E., Engelman J. A., Schlegel A., Parenti M., Okamoto T., Lisanti M. P. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 10257–10262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Medina F. A., Williams T. M., Sotgia F., Tanowitz H. B., Lisanti M. P. (2006) Cell Cycle 5, 1865–1871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parton R. G., Hanzal-Bayer M., Hancock J. F. (2006) J. Cell Sci. 119, 787–796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lavie Y., Fiucci G., Liscovitch M. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 32380–32383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Witkiewicz A. K., Dasgupta A., Sotgia F., Mercier I., Pestell R. G., Sabel M., Kleer C. G., Brody J. R., Lisanti M. P. (2009) Am. J. Pathol. 174, 2023–2034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fagerholm S., Ortegren U., Karlsson M., Ruishalme I., Strålfors P. (2009) PLoS One 4, e5985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Radel C., Rizzo V. (2005) Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 288, H936–945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Volonté D., Galbiati F., Pestell R. G., Lisanti M. P. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 8094–8103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]